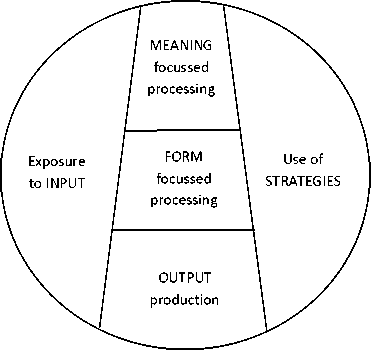

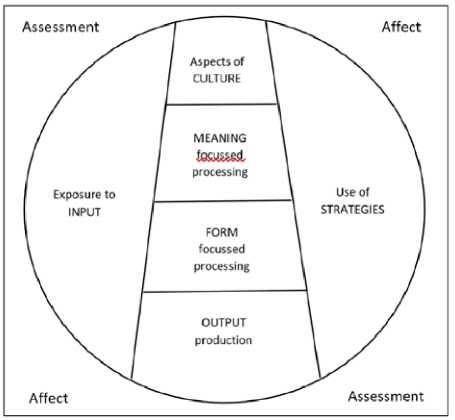

Figure 1. The Observation Tool for Effective CLIL Instruction (de Graaff et al., 2007, p. 610).

REFLEXION ON PRAXIS

An Observation Tool for Comprehensive Pedagogy in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): Examples from Primary Education

Una herramienta de observación para la pedagogía de comprensión en contenido y de lenguaje integrado: Ejemplos de la Educación Primaria

Taina Wewer1

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Wewer T (2017). An Observation Tool for Comprehensive Pedagogy in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): Examples from Primary Education. Colomb. appl. linguist.]., 19(2), pp. 277-292.

Received: 03-Feb-2017 / Accepted: 22-May-2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/22487085.11576

Abstract

This article on principles and practices in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is also applicable for general foreign and second language instruction. Since there is no ‘one size fits all’ CLIL pedagogy, the origin of the article lies in the need of educators to obtain and exchange ideas of and tools for actual classroom practices (Pérez Cañado, 2017), and ensure that all key features of CLIL are present in instruction. Although there are a few handbooks available for launching CLIL and adopting CLIL pedagogy (e.g., Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010; Mehisto, Marsh, & Frigols, 2008), these provide principles and general examples of content-based instruction at higher levels of education rather than more detailed advice on how to operate in the beginning phases with young language learners, hence the focus on primary education. The Observation Tool for Effective CLIL Teaching created by de Graaff, Koopman, Anikina, and Gerrit (2007) was chosen as the starting point and was complemented with three additional fields that were not markedly included in the original model: cultural aspects, affects, and assessment.

Keywords: bilingual education, CLIL, EFL, pedagogy, young language learners

Resumen

Este artículo sobre principios y prácticas en el Aprendizaje Integrado de Contenidos y Lenguas Extranjeras (AICLE) también es aplicable para la enseñanza general de idiomas extranjeros y de segunda lengua. Dado que no existe una pedagogía de AICLE de tamaño único, el origen del artículo reside en la necesidad de los educadores de obtener e intercambiar ideas y herramientas para prácticas reales en el aula (Pérez Cañado, 2017) y aseguren que todas las características clave de AICLE están presentes en la instrucción. Aunque existen algunos manuales disponibles para poner en práctica AICLE y adoptar la pedagogía de AICLE (por ejemplo, Coyle, Hood y Marsh, 2010, Mehisto, Marsh y Frigols, 2008), estos proporcionan principios y ejemplos generales de instrucción basada en contenido en niveles más altos de educación en lugar de un asesoramiento más detallado sobre cómo operar en las fases iniciales con los estudiantes de idiomas jóvenes, por lo tanto, el enfoque en la educación primaria. La herramienta de observación para la enseñanza efectiva en CLIL creada por de Graaff, Koopman, Anikina y Gerrit (2007) fue elegida como punto de partida y fue complementada con tres campos adicionales que no fueron incluidos marcadamente en el modelo original: aspectos culturales, afectos y evaluación.

Palabras clave: AICLE, educación bilingüe, estudiantes jóvenes de idiomas, ILE, pedagogía

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) has been a popular approach to foreign language instruction since the 1990s, and its popularity does not show signs of waning (see Pérez Cañado, 2012, for an overview) evidenced in the proliferation of CLIL to Latin America, Asia and Australia. CLIL is a general, originally European designation for additive varieties within bilingual education; in other words, the aim is to broaden and extend the language repertoire of the learner by adding one language or more. In CLIL, a foreign target language (TL) is acquired to pre-defined levels through using the language meaningfully as a medium of teaching and learning various contents across the curriculum together with the actual language of schooling. Content and TL instruction thus form an intertwined whole instead of being perceived as separate lines of study. In most CLIL programs, however, study of English as a foreign language (EFL) is distinctively separate from CLIL (e.g., Dalton-Puffer, 2011; Hüttner & Smit, 2014); ideally, the two would complement and support each other.

CLIL has its roots in Canadian immersion, North-American content-based instruction (CBI), and European international schools with which it also shares the most prominent theoretical premises (e.g., Pérez-Vidal, 2007; Pérez Cañado, 2012; Wewer, 2014a), simultaneously drawing from research in the field of second language acquisition. CLIL-specific research, during its approximately 25-year-long existence with Europe as its hub, has mainly evaluated the efficiency of CLIL programs, focused on language development or skills, affective factors, the qualities or perceptions of teachers, and classroom discourse. In general, the results at various levels of instruction and in different types of CLIL have been utterly positive. Dalton-Puffer’s (2008) review of CLIL research shows that the language aspects that mostly appear to benefit from CLIL instruction are receptive skills, vocabulary, and morphology along with, for instance, creativity, risktaking, fluency, and the extent to which language is acquired. The research synthesis by Pérez Cañado (2012) adds the following advantages: learner motivation, writing in form of more complex lexis, syntax and fluency, as well as equal, if not occasionally better, content learning outcomes in comparison to mainstream learners, as a substantial amount of CLIL research is comparative.

There are areas in CLIL research that have not yet been sufficiently covered. Pérez Cañado’s (2012) review, pertaining to European studies, lists high priority research areas: methodology, teacher observation, and assessment of both content and language. The reason why pedagogy has received less, and language assessment hardly any attention may be their complexity as a phenomenon. Since CLIL as an umbrella term entails several varieties of bilingual instruction, there is no single model of bilingual content instruction (e.g., Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010; Eurydice, 2012; Pérez Cañado, 2012), and therefore no shared, uniform pedagogy. As Hüttner and Smit (2014) point out:

There is no unified CLIL pedagogy and even less a CLIL method. CLIL practice is informed by local realizations of language teaching methodologies (often with at least a nod to communicative language teaching, itself an approach that encompasses a range of practices) and, most importantly of all, a host of content subjects. (p. 163)

As a result, it is challenging to provide an all-encompassing characterization of CLIL pedagogy. Although every context is different, there still are a number of common prototypical traits. One such trait is the most frequent target language, English (Eurydice, 2012). Further commonalities in various CLIL models include, for instance, grounding education on socio-constructivist, cognitive learning theories, enhancing student-centricity and active learner agency, and seeing teachers as facilitators who are able to adapt authentic materials according to the needs of content and presence of language learning objectives (Bovellan, 2014; Pérez Cañado, 2017; Wewer, 2014a; Wewer, 2015).

Furthermore, following from the dual focus on meaning (content) and form (language needed for content study), language is rather perceived as “a resource than a system of rules” whereby fluency is rated higher than accuracy (Pérez Cañado, 2017). This does not exclude form-focused, content-driven language instruction. In CLIL, the shift of paradigm from implicit toward more explicit language teaching has been notable, but still partly debatable (see Wewer, 2014a, pp. 37-41 for discussion). Additionally, since the language register of schooling is predominantly academic, the emphasis should be on the development of academic language proficiency (CALP) which is promoted and preferred over social language (BICS). As far as pedagogy, it is also important to realize that teaching through English in CLIL is more than translating the main language of schooling into English or teaching in English (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010). The use of English must be more strategic and carefully planned to support simultaneous content learning and language acquisition. This expectation generates demands on CLIL teacher skills.

Due to the content-driven dual focus, it is logical that content teachers, at least in non-Anglophone settings (see Coyle, 2013), are the ones teaching through English—with varying linguistic educational backgrounds ranging from no language studies to double qualifications in both content and language (Nikula, & Jarvinen, 2013; see also Hüttner & Smit, 2014). This notion is corroborated by European language statistics (Eurydice, 2012) stating that two-thirds of European countries with CLIL provision do not require any language qualifications or courses on CLIL pedagogy from CLIL teachers which likely has resulted in fluctuation in CLIL skills and practices. Teachers’ language skills do not need to be perfect, but fluent oral production, articulation, and pronunciation should be good, for they act as the primary linguistic models. Students, exposed to a rich extramural linguistic landscape, may become irritated by poor pronunciation skills displayed by their teachers, as Pihko (2010), looking into CLIL experiences of young teenagers, discovered. However, native-like proficiencies are not sought nor required from teachers (e.g., Pérez-Cañado, 2017), neither are native-like accents nowadays considered as the sole proper model, as English has become a Lingua Franca, and language learners are more likely to encounter other accents than British or American English as non-native speakers of English outnumber native speakers (Kopperoinen, 2011, p. 72) .

While CLIL teachers’ language skills may vary substantially, so do their perceptions of the role of the TL in CLIL. Wewer (2014a) revealed how the role of English was either seen as instrumental (implicit approach to TL, not necessary to address), dual (both content and language had equal weight), or eclectic (the role of language in CLIL was unclear or ambiguous). Additionally, Bovellan (2014) concluded that teachers’ views of language varied between two polarities: language as a syntactic system or means of communication. Uncertainty and ignorance on how to implement CLIL methodology in practice, even resistance (see Hillyard, 2011), are likely to be common in the beginning phases as embarking on CLIL often is an administrative decision reached by the leadership, not the teachers themselves. Teachers’ varying educational backgrounds contribute to methodological perplexity, but theoretical premises lend support in moments of pragmatic confusion.

The three most eminent theoretical entities guiding CLIL pedagogy are: (1) the 4 Cs framework; (2) the Language Triptych, and (3) CLIL Matrix (see e.g., Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010; Coyle, 2012). The 4 Cs framework guides unit planning and consists of content, communication, cognition, and culture, each domain needed to tap on within a study unit. The application of Language Triptych in the unit plan in turn ensures that language objectives under the C of communication will be considered from different viewpoints: language of (most notably key concepts), language for (linguistic patterns needed to negotiate the content), and language through (the expected new language emerging from the unit). The CLIL Matrix is a version of Cummins’ (1982) model of language proficiency exemplifying how linguistic and content-related tasks should advance from less to more cognitively demanding and from context-embedded to context-reduced. In addition to these three basic tenets, linguistic CLIL pedagogy should also be informed by other theoretical considerations such as the revised Bloom’s taxonomy2 of cognitive objectives (Anderson & Kraftwohl, 2001) dividing cognitive learning goals into two branches, lower and higher order thinking skills, combined with factual dimensions; Schmidt’s (1993) noticing hypothesis purporting that explicit scrutiny of language forms is beneficial for learning, and; Vygotsky’s concept of the zone of proximal development (ZPD) which affords for scaffolding, i.e., supporting learners to reach their maximal potential through help given by more capable facilitators (see Wewer, 2014a for a review of theoretical foundation of CLIL).

Another theoretical instrument for conducting an analytical observation study of non-native CLIL teachers’ secondary-level classroom TL methodology was created by de Graaff, Koopman, Anikina, and

Gerrit (2007). The Observation Tool for Effective CLIL Instruction can be employed as an aid in focusing on substantial areas of CLIL teaching to ensure that the language focus is not too narrow but sufficiently addressed. As demonstrated in Figure 1, there are five areas included in this analysis instrument: (1) exposure to input, (2) meaning-focused processing, (3) form-focused processing, (4) output production, and (5) use of strategies. The five areas translated into actions entail teachers facilitating:

1. Exposure to input that is linguistically meaningful, challenging, and appropriate to the learners’ proficiency-level by selecting, adapting texts used and teacher talk prior and during teaching

2. Content-oriented processing by assigning tasks and activities that help learners to identify and grasp the core content and using comprehension checks

3. Form-oriented processing by pointing out, exemplifying and explaining relevant language forms needed to work with the content at hand

4. (Pushed) output by prompting reaction and interactive communication, stimulating language use, providing written practice and corrective feedback

5. Strategic language use by using compensatory means such as visuals, graphic organizers and realia to convey meaning, providing in-situ language tutoring when needed, scaffolding

Figure 1. The Observation Tool for Effective CLIL Instruction (de Graaff et al., 2007, p. 610).

both strategic reflection, and use of various

strategies to overcome language barriers (de Graaff et al., 2007, pp. 606-619).

In all areas of effective CLIL strategy, teachers are expected to provide feedback to the learners on their language use and content mastery as well as encourage reflective approaches (de Graaff et al., 2007). Methodologically, reflection, classroom-based observation, and methodological dialogue are the means that “will increasingly characterize representative pedagogical CLIL practices and allow us to make headway in this area” (Pérez Cañado, 2017, p. 86). The pedagogical discussion and presentation of practical examples in the next section follow the organization of the Observation Tool. However, since cultural perspectives are considered to be an essential part of CLIL (cf. the 4 Cs framework), affect is commonly seen as an important factor in learning, and the assessment perspective is not markedly present. Thus, I have added three additional categories to the Observation Tool which I present and discuss in the following pragmatic section: aspects of culture, affects, and assessment.

Learners should be exposed to rich, accurate input that is attractive to them and leads to spoken language production. Certain functions occur in English every day and often in a similar manner because young children typically like predictability, repetition, and they enjoy noticing their own success in practicing with and producing language. Therefore, the teacher needs to follow pre-defined, precise linguistic patterns. Although English is increasingly ubiquitous, young learners still need plenty of exposure to simple, communicative English during the first years of CLIL study to develop basic BICS skills from which they advance toward more academic CALP which may take 7-9 years, even in immersive circumstances (e.g., Cummins, 1982; Cummins, & Man, 2007), whereas BICS skills acquisition takes a few years. During the first two years of CLIL instruction, language input is primarily based on listening comprehension, and language production is mainly speaking. However, some CLIL learners may undergo a so-called ‘silent period’ during which they produce hardly any language, but rather develop their comprehension skills (see Bligh, 2014; Drury, 2013).

Particularly in the initial phases when the learners’ language is passive and still emerging, Total Physical Response (TPR; Asher, 1969, 1981) is a non-threatening and common method: the teacher gives a command or task, modelling its meaning simultaneously, and the learners demonstrate understanding by reacting accordingly. Action rhymes and songs loosely fall into this category insofar as they enable kinesthetic language learning, but can also be recited and sung allowing a more active, participatory element. The following simple activity rhyme example is about teddy bears:

Hello teddy bears!

Teddy bear, teddy bear, turn around.

Teddy bear, teddy bear, touch the ground.

Teddy bear, teddy bear, tie your shoe.

Teddy bear, teddy bear, a task for you! (Other

versions: good-bye to you, we all love you, have

a seat, etc.)

Obviously, such activities must be age-appropriate and preferably have a connection with subject content or school/seasonal events. Furthermore, it is crucial that they are fun in order to awaken interest in the TL and create positive affective responses, i.e., joy of learning since “feelings of triumph lead students to the road of success in terms of learning” (Rantala & Maatta, 2012, p. 87). The recurring practices introduced below mainly serve the purpose of introducing children to English and giving them experiences of linguistic success—specifically the casual, social everyday language needed for coping with other people—in pleasant, playful, and often funny ways that have an appeal to children. Variation can and should be introduced when the basics have been mastered, and production of spoken language gradually shifts from the teacher to the learners.

The below listing is by no means exhaustive or all-encompassing; it merely gives ideas on how to approach instruction in bilingual settings using various methods. Examples of recurring practices promoting primarily social language include:

• greetings and small talk

• classroom organization (e.g., stating absences, date, weather or temperature, acknowledging birthdays, days till a holiday or break)

• interactive morning calendar3 displayed on the Smart Board (date, weekdays)

• weekly songs, rhymes or action songs (e.g., from CD or YouTube, with or without lyrics)

• farewells

• good-bye songs or humoristic rhymes

• playful activities, reading short stories or tales

There is scientific support of the positive effects of music, musical practice, or aptitude to language learning including both general (Shabani & Torkeh, 2014) and specific evidence in form of enhanced language production and sound discrimination (Milovanov, 2009) as well as better pronunciation (Milovanov, Tervaniemi, & Gustafsson, 2004). Alisaari and Heikkola (2017) purported that songs and poems appear to have a positive impact on various language skills. Thus, it appears to be helpful for language acquisition to provide multimodal input. The practice of having a weekly morning song that is connected to a weekly content theme has been deemed useful by the author for the language acquisition of young learners. The same song, slightly above the linguistic level of the learners, is repeated every morning at the beginning of the first lesson. At first, the song is introduced within a context and justified, and the most critical concepts and vocabulary are introduced and translated. Then, the pupils listen to the song, and they join in sing-along and actions as soon as they feel confident in doing so. New forms or aspects can be investigated each day. At the end of the week, everyone is usually able to sing independently and while so doing, students learn new language multimodally.

Jazz chants are also an attractive and funny way to introduce new language in chunks, for going beyond the single-word level is crucial to building

3 e.g.,http://more2.starfall.com/m/math/calendar/play. htm?f&ref=main, retrieved April 23, 2017. The site also contains many other activities applicable for primary level.

language as a communicative tool and to practicing linguistic structures. Jazz chants, created by Carolyn Graham in the United States, are rhythmic rhymes, poems, or songs that can be recited or sung with a beat in a choir, groups, individually, or taking turns, and they can be composed of individual words, collocational chunks of words, sequential, cohesive sentences, or longer pieces of narratives such as fairy tales. Skilled teachers easily compose3 their own specific purpose jazz chants which also provide a good starting point for performances in school festivities or parental evenings. Recitations of jazz chants can also be found on YouTube. Graham stressed in the Vimeo video annotated in the footnote that it is crucial for jazz chants that they represent living language used in everyday situations.

Social BICS-type language proficiency, however, is not sufficient for content study, as the classroom language differs from the language register used in extramural contexts. In the early stages of CLIL implementation, however, the main emphasis is on acquiring such a level in comprehension and production that enables basic interaction and operation in the classroom environment. In order to succeed in this, it is important for the teacher to master a solid sample of basic classroom language4 which has been found to be equally as important for learners’ language acquisition as teachers’ general language mastery (Van Canh & Renandya, 2017). The phrases soon become familiar to pupils because they are used in context (see Slattery & Willis, 2001, for an extensive presentation of teacher classroom talk).

Because this article pertains to young language learners in the initial stages of CLIL study in which language teaching mainly concentrates on the acquisition of very basic communication and content skills, teaching material adaptation will not be touched upon. The study of Bovellan (2014) navigates through research in the area of CLIL material design and is therefore worth familiarizing. In addition, the handbook by Coyle,

Hood, and Marsh (2010) will prove itself useful in this realm.

This section will look into how the teacher can harness language to serve content learning. As de Graaff and colleagues (2007) underline, “mere exposure to language is not enough” (p. 608); it is necessary that the language used in the classroom have a connection to the content studied. Where de Graaff and colleagues see content-focused processing as mainly related to identification of meaning, this article takes a slightly broader view by moving more toward the C of cognition in the 4 Cs framework. There are certain quintessential principles regarding content-based language instruction (based on Rahman, 2013, pp. 43-44):

1. English language is best maintained without code switching between the two languages of instruction. This means that there are clearly separate content sessions through English and the other language of instruction. Otherwise, pupils soon learn to ignore English because they will hear/learn the same repeated in the more familiar language. However, the notion of completely separate language sessions has been challenged by recent literature that allows translanguaging and sees it beneficial for especially multicultural classrooms, as it accepts students to use all of their linguistic repertoires to negotiate meaning in their ZPD, helping one another (García, Ibarra Johnson, & Seltzer, 2017). Translanguaging is “the planned and systematic use of two languages inside the same lesson” (Baker 2011, p. 288), for example between language of schooling and the TL.

2. Less is more. When the teacher is able to articulate clearly, speak slowly enough, and keep to the point, the pupils are more likely to understand.

3. Repetition, i.e., using the same or similar-type utterances, works for younger learners; older learners may benefit from paraphrasing, i.e., repeating the message in other words. In addition to repeating, checking students’ understanding of content also contributes to attainment. De Graaff and colleagues (2007, p.

615) identified three different types of meaning identification checks: (1) clarifications (e.g., did you understand?); (2) validation (e.g., what makes you think that?), and (3) confirmation (e.g., do you agree?).

4. Thinking time is required; formulating ideas in a foreign language does not come automatically and quickly. Therefore, the teacher should remember to wait considerably longer than seven to eight seconds before moving forward with asking another pupil or, in the worst case, answering him/herself.

5. Students are an immense resource of knowledge. Shared construction is much more powerful than the teacher catering for learners as the sole source of knowledge. Whenever possible, the learners should be encouraged to produce new information together.

The first step in constructing academic language proficiency through content is to build learners’ vocabulary, both communicative, everyday vocabulary as well as academic vocabulary that is crucial for grasping the essentials of the given content. Theme-based content instruction readily helps learners to navigate within the theme vocabulary. Examples of themes, which ideally are cross-curricular, i.e., draw on two or more school subjects simultaneously, are ‘time,’ ‘space,’ or ‘poetry.’ In weekly theme-based instruction, it is possible to delve deeper into a topic from different angles of school subjects and provide content through both languages of instruction repeatedly, thus reinforcing learning each day. Examination of one macro topic for at least a week provides more possibilities to build a richer linguistic and visual learning environment with increasing complexity.

Another good starting point is to activate and trigger both learners’ linguistic and content-based background knowledge. This can be facilitated, for example, by employing metacognitive tools such as the KWL (know-want to know-learned) charts portrayed in Figure 2 which can be revisited at the end of the syllabus to make learning more visible and fill any remaining knowledge gaps. The KWL chart also allows individualization as every learner has a different background and language and content needs.

Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive objectives mentioned earlier—advancing from lower order thinking skills (remembering, understanding and applying) to higher order thinking skills (analyzing, evaluating, and creating)—is particularly applicable as a checklist to ensure that the cognitive skills needed to complete various classroom tasks do not remain at lower cognitive levels. Instead, learners must also be challenged by more demanding tasks which require more complex language needed in, for example, summarizing, predicting, justifying, and various tasks dealing with more demanding content. At the end of the lesson, teaching session or unit, sentence frames, which are one form of scaffolding, can be used to conclude the main idea(s). Summary frames could be a set of questions pertaining to the main ideas, argumentation, definitions, problems and their solutions, and so forth, or they could be sentence frames. An example of a simple cause/ effect summary frame with less and more academic options is as follows:

(Something) happens because (something). (Something) takes place due to (something).

Several sentence and summary frame templates are available online. For those interested in further exploration of language-driven content learning methods, there are didactic handbooks in English dealing with CLIL instruction (e.g., Bentley, 2010; Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010; Mehisto, Marsh, & Frigols, 2008).

Form-focused processing is related to the linguistic intricacies in the use of TL. In most CLIL-providing countries, in addition to their bilingual CLIL lessons, students learn English in separate, mainstream EFL lessons which place more emphasis on grammar and linguistic correctness. It may be detrimental for overall language development to rely on EFL only as the sole source of language forms, grammatical knowledge, and accurate language use as the demand in CLIL and supply in EFL may not necessarily meet. Therefore, literature on bilingual education recommends more analytic, form-focused approaches in cases where instruction combines content and the foreign/second language (e.g., Lightbown & Spada, 2008). Form-oriented processing hence refers to teachers anticipating language structures or forms likely needed in content study (e.g., past tense in history) and then providing explicit linguistic support to alleviate content study (Lightbown & Spada, 2008). In the ideal situation, EFL and CLIL underpin each other. Curricular alignment of linguistic objectives, when applicable and possible, would also enhance form-oriented processing of content and familiarization with academic language.

Academic language is ‘relative’ (Snow & Uccelli, 2009, p. 115) which means that subject-related disciplinary language may be less academic, but it still displays some characteristics of academic language such as dense information, appropriate voice, and technicality (Schleppegrell, 2006). This specifically applies to primary-level education. According to Scarcella (2003, pp. 10-12), academic language consists of five constituents that are well-defined in literature and teachable: (1) phonological, (2) lexical, (3) grammatical, (4) sociolinguistic, and (5) discourse components. Phonological components refer to pronunciation, e.g., placing stress on the correct syllable, whereas lexical components pertain to vocabulary and use of appropriate words in right contexts. For example, children tend to use the terms ‘plus calculation’ or ‘minus calculation’ when referring to addition and subtraction which are their academic-appropriate counterparts that should be used in instruction.

|

Topic |

What I know |

What I Want to Know |

What I Learned |

|

LANGUAGE (e.g., content- | |||

|

obligatory vocabulary) | |||

|

CONTENT |

Figure 2. KWL chart example.

The grammatical component in turn refers to various, more complex rules in punctuation as well as issues in word, phrase, and sentence formation such as inflections, collocations, and phrasal verbs, or combinations of verbs with certain prepositions or particles. Sociolinguistic features of language entail, for instance, knowing the usage of diverse language functions (e.g., persuading, complaining, and arguing) as well as various genres, both of which have recently become a target of interest in CLIL literature (e.g., Llinares, Morton, & Whittaker, 2012). Finally, the discourse component includes knowledge of various helpful devices used both in spoken and written academic language, for example transitions or pointing out ideas.

When these basic aspects of academic language are embedded in the curriculum and teachers bear their development in mind from the beginning stages onward, development of academic language needed in content learning becomes more planned and structured. This viewpoint is resonated in the consensus view in the field of education according to which the mastery of academic language appears to have a decisive role in academic achievement given that language is the tool for learning and human communication (see e.g., Krashen & Brown, 2007).

Output refers to content-based language production, spoken or written, and it benefits from scaffolding. Bringing the acquired content vocabulary to the next sentence level entails literacy development. Language prompts in form of sentence starters are of aid to learners when formulating their ideas and uttering knowledge. Examples of prompts at their simplest, when pupils are practicing describing things or objects, could include the following:

This is... (What is it?)

It is. It has. (What does it have?)

It is similar to. because. (Why is it similar?)

It is different from. because. (Why is it

different?)

The most frequent or current sentence starters could be on permanent display in the classroom as posters. The teacher may also model the language by first uttering the wished outcome sentence, then asking a question related to it, and encouraging learners to repeat the original model phrase. Through this simple method, questions become familiar in addition to description practices. CLIL teachers use various methods to elicit dialogic interaction, among the most frequent are (Wewer, 2014a):

• teacher-initiated discourse (teacher asks, learners answer, teacher gives feedback)

• situational language use (e.g., English only during lunch or when the British flag is displayed)

• soirées and performances (e.g., musicals, English evenings, drama plays)

• pedagogic drama (related to content topics such as water cycle)

• student talks and presentations (content topics or personal)

• group-work, subject-related topics (e.g., related to geography, pupils organizing a science fair)

• bilateral projects between schools and twin schools (any agreed content topic)

• interviews of foreign visitors (e.g., athletes, teachers, students)

In optimizing classroom conversations, the publication of Zwiers and Crawford (2011) on academic classroom discussion and fostering critical thinking gives any content teacher ample ideas.

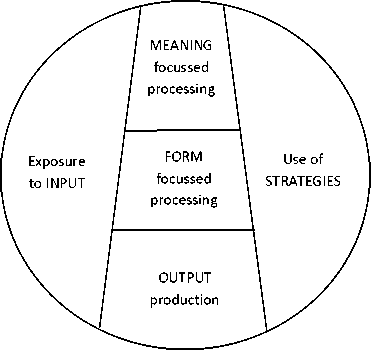

After the initial period, writing in English and expressing content knowledge soon becomes necessary. In order to be able to write, learners need practice which can be gained by first copying words, chunks of texts, then practicing shared writing in which the teacher and learners write together or learners among themselves are negotiating spelling, writing conventions, and punctuation. The teacher provides the pupils a model which they can repeat or according to which they can attempt to create their own texts, gradually starting to produce texts independently. When writing independently, graphic organizers are useful to plan or guide writing. One example of scaffolding and guided writing is the Black Bear writing wheel (Figure 3), apt for learners who are already more skilled in the TL (see e.g., Swinney & Velasco, 2011, for other models of graphic organizers).

285

Wewer T. (2017) • Colomb. appl. linguist. j.

Printed ISSN 0123-4641 Online ISSN 2248-7085 • July - December 2017. Vol. 19 • Number 2 pp. 277-292.

Figure 3. Black bear writing aid wheel (Wewer, 2014b, p. 56).

The writing wheel, posters, and similar scaffolding methods also fall under the last, fifth category included in de Graaff and colleagues’ Observation Tool for Effective CLIL Teaching (2007), strategic language use.

When students do not possess the language or form(s) necessary to learn content and negotiate meaning, they tend to resort to various communication strategies which can be divided into avoidance and achievement strategies. Teachers should encourage students to pursue achievement strategies such as circumlocution (description or exemplification of the properties of the intended word or expression) or approximation (replacing the intended word or expression with a close synonym; Rahman, 2012). Rahman (2012) found that avoidance strategies were more common in young CLIL learners, and that even they were able to successfully perform various communicative tasks by using different strategies when interaction occurs within their ZPD with a native speaker.

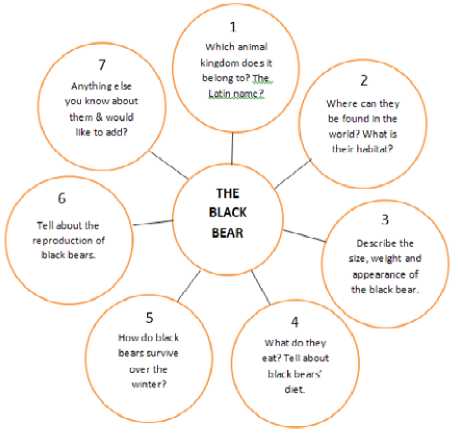

Additionally, non-linguistic cues are valuable and necessary to convey meaning especially if the rule of maintaining one language at a time is respected. Gestures such as pointing, facial expressions, mimicking, drawing pictures, using visuals and graphic organizers, and practices related to multiple literacies become valuable. The photos in Figure 4 below exemplify both the thematic approach briefly introduced in the content-focused processing section above, and how key thematic vocabulary can be displayed in the classroom through visuals. Furthermore, they also demonstrate how information organizers such as graphics, mind maps, charts, and diagrams allow the intake or recapping of information with one glance.

Examples of methods of visualizing vocabulary are word walls, word clouds5, concept definition maps, flash cards (picture + word), labelling objects and so forth (see Swinney & Velasco, 2011). It is important to keep in mind that when visuals and vocabulary are accumulating on classroom walls, they may lose their attraction and their educational effectiveness may fade as they become mere visual commotion. The displays should be meaningful for then current learning situations.

Culture is a notable part of CLIL and foreign language instruction, as language is an inseparable part of its cultural environment. Cultural aspects, however, were not part of the original Observation Tool for Effective CLIL Instruction suggested by de Graaff and colleagues (2007) as their model concentrated more strictly on language. Addressing cultural aspects, however, can also be projected in language acquisition. The development of cultural awareness and embracing cultural opportunities is one C in the 4 Cs framework. Culture in CLIL should stretch beyond the “foods and festivals approach” (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010, p. 64). As Coyle, Hood,

Figure 4. Examples of content-based visuals also scaffolding language.

and Marsh (2010) point out, cultural exposure and investigation allow “addressing fundamental issues of ‘otherness’ and ‘self’” (p. 64), and they continue stating firmly that “integrating cultural opportunities into the CLIL classroom is not an option, it is a necessity” (p. 64).

For young language learners, traditional Anglo-American national holidays, however, are a natural way to start cultural explorations. In the classroom, celebrating and acknowledging typical holidays and traditions in the Anglophone world, such as Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas, Valentine’s Day, St. Patrick’s Day, and Easter, as well as examining their characteristics, typical vocabulary and customs, gives learners a deeper understanding of the interrelations of language and culture. Furthermore, such investigations allow diversity and help children realize that there are multiple cultural realities and identities in the world, none of which is superior to another. In order to expand cultural exploration beyond the ‘foods and festivals approach,’ teachers are encouraged to make age- and language-level appropriate notice of cultural. This may include aspects such as worldviews, values, religion, and religious practices, music, architecture, manners, habits, ways of social interaction, to mention a few, as well as to make issues related to the physical world and human experience (e.g., nature, cities, transport, industry) gradually familiar to the learners.

Affective factors in language learning refer to emotions and emotional stages such as “anxiety, inhibition, risk-taking, extro/introversion, empathy, motivation and self-esteem,” (Habrat, 2013, p. 240), and they cannot be separated from educational contexts, as education involves holistic human beings instead of just the cognitive part of them. Affective factors are believed to have an influence in language learning, as Krashen’s (1985) affective filter hypothesis postulates, arguing that the filter may form a mental block inhibiting language learning regardless of otherwise favorable circumstances. Research has concluded that CLIL appears to have a positive impact on learner motivation, but a negative impact on their linguistic self-esteem in form of higher expectations for language performance and self-criticism (Seikkula-Leino, 2007).

The findings of Pihko (2007) affirm the significantly higher motivation and positive attitudes of CLIL students in comparison to mainstream EFL students. Furthermore, Pihko (2007) concluded that the majority of CLIL students portrayed a strong language self-image, yet they suffered from language anxiety more than their EFL counterparts. Affective factors in language classrooms are partly related to the feedback given by teachers, as Habrat (2013) points out, “the appraisal of the teacher may be critical to the learner’s opinion of his worth. S/ he is likely to perceive him/herself as having the characteristics and values that the teacher attributes to him/her” (p. 247). Therefore, it is crucial that teachers take notice of even small steps of progress, effort, positive attitude, and motivation in case no high-standard outcomes are available for praise. In the following section, assessment issues are discussed more closely.

Assessment deserves a more salient role in the Observation Tool than originally given, not just for the reason that assessment is an intrinsic part of any educational setting, but also because research shows that assessment does not always take place in CLIL (Wewer, 2014a). Furthermore, research pertaining to language assessment in CLIL is very scarce. In order to be able to assess language in CLIL, the linguistic objectives must be pre-determined, a self-evident practice which has been requested by scholars (Dalton-Puffer, 2007), but is not always realized (Wewer, 2014a). For example, the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (NCC, 2016), maintains that “assessment [in CLIL] must give the teacher, the pupil and the guardian adequate information about the pupils’ command of the subjects and development in language skills in relation to the goals specified for the education” (p. 94). Both foci of CLIL are thus mentioned as the target of assessment, and it is plausible, or at least advisable, that the same principle apply to global CLIL circumstances as well.

Assessing and giving feedback on both foci in CLIL is not always a simple undertaking, for the danger in assessing content-knowledge through the TL is that other factors may influence the assessment results. For instance, eloquent language use may give the false impression that content mastery is strong when it actually is not (Honig, 2010). For the present, the study by Wewer (2014a) appears to be the only assessment study encompassing young language learners in the field of CLIL. The study concluded, among other things, that assessment of the TL is not yet an established practice. Of the stakeholders in assessment, particularly primary-aged learners and their guardians expressed their wish to receive more feedback on the development of the TL in CLIL, as 91% of pupils perceived receiving feedback rarely or occasionally (Wewer 2014a). The findings of this study led to a set of recommendations which identify: (a) the fundamentals of CLIL assessment (requirement of a separate CLIL curriculum and CLIL assessment scheme, elucidation of principles of CLIL implementation to stakeholders as well as adequate language and CLIL teachers’ competences); (b) the principles of adequate CLIL assessment (dual focus on both content and language, multifaceted assessment methods, evidence-based inferences of English proficiency, criterion-referenced inferencing as well as frequency and sufficiency of assessment information and feedback), and (c) the recommended CLIL assessment methods.

Potential assessment methods in CLIL are collaborative testing (group tests) that are based on social interaction and co-operative knowledge construction. In collaborative testing, the individuals forming the group can display their diverse strengths, and use the TL for a meaningful purpose in a less stressful test situation because the pressure of achievement is shared. One form of language testing administered collectively is task-based language testing (TBLT). Simply defined, this assessment method is constituted of a more complex task in which the TL and content are combined and the test taker needs to solve some kind of a problem (e.g., how to get to Rio de Janeiro from New York in the most inexpensive way or shortest time) and then present the results. Web Quests6 are one interesting application combining TBLT and technology-based language testing.

Technology-based language testing is a phenomenon of the 21st century and modern era, yet not fully capitalized. Computers and smart phones provide a platform for documenting content-based language performance and, over time, showing development in English proficiency. There is a myriad of applications, also with elements of fun, suitable for quizzes or written technology-based testing (e.g., Socrative7, Kahoot8). Voice recording, presentations, videos and online conferencing through Skype, for instance, are methods that are easily and inexpensively accessible for everyone. Digital data is storable, transferrable, and effortlessly duplicable for parents.

Portfolios are one of the most flexible and suitable means of gathering and displaying evidence of language learning and TL use. Portfolios make learning and especially the development of TL visible over time, and they can be implemented in many formats. The portfolio resembles both a dossier, which is a showpiece of language competence, and reflective portfolio, which provides “evidence of growths and accomplishments” for self-assessment purposes (Smith & Tillema, 2005, p. 627). The benefits of portfolio work pertain to accentuating the ‘can do’ aspect rather than pointing out deficits in learners’ language proficiency. In CLIL, the stored language samples would be linked with tasks showcasing content mastery through the TL. Portfolios are very concrete assessment tools and they are highly applicable to any grade level. Language portfolios in CLIL can be implemented even with first and second graders (Wewer, 2015).

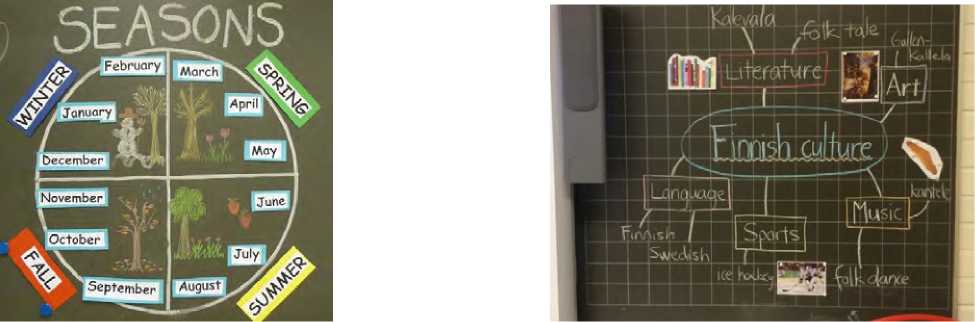

This article has looked into CLIL instruction at primary level using the Observation Tool for Effective Instruction in CLIL (de Graaff et al., 2007) created for research purposes and specifically to observe aspects related to the two primary foci of CLIL: content and language. When instruction in CLIL is approached from a more comprehensive viewpoint, including assessment of language and content, cultural aspects and affect, as the commonly accepted view of main CLIL constituents necessitates, the original graphic (see Figure 1) describing effective CLIL instruction looks different. Figure 5 presents how the new constituents have been included in the diagram, thus creating a new, revised Observation Tool for Comprehensive CLIL Instruction that takes all of the Cs in the 4 Cs framework into account.

Figure 5. An Observation Tool for Comprehensive CLIL Instruction.

To summarize a CLIL learning environment through the Revised Observation Tool, CLIL classrooms should exhibit an affectively safe oasis with rich linguistic exposure to the TL and cultural phenomena related to it. CLIL emphasizes collaboration with linguistically and culturally diverse groups in which learners have the opportunity to benefit from the language skills of their more capable peers and work with challenging, authentic materials that often are linguistically modified by the teacher who also pays attention to the form of language needed in content study. The quality of input, output, and interaction as well building on prior knowledge is typical for CLIL. It is important to make the essential distinction between social everyday language (BICS) and academic language (CALP) of which the latter is characteristic of school discourse. The ultimate aim of CLIL is to promote language needed for educational achievement, but particularly in the initial phases, the development of more casual, social language cannot be overlooked. In their linguistic endeavors, learners are encouraged to use various strategies to achieve their communicative goals. The conventions of academic language, according to current views, need to be addressed and scaffolded in the teaching and learning of content matter. At all phases, provision of feedback and assessment of instruction are important functions. The Revised Observation Tool can hopefully be of aid to teachers in their endeavor to achieve more comprehensive and effective Content and Language Integrated Instruction.

Alisaari, J., & Heikkola, L. M. (2017). Songs and poems in the language classroom: Teachers’ beliefs and practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 231-242.

Anderson, L. W, & Kraftwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York, NY: Longman.

Asher, J. J. (1969). The total physical response approach to second language learning. The Modern Language Journal, 53(1), 3-17.

Asher, J. J. (1981). The total physical response: Theory and practice. In H. Winitz (Ed.), Native language and foreign language acquisition (pp. 324-331). New York: New York Academy of Sciences.

Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (5th ed.). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Bentley, K. (2010). The TKT teaching knowledge test course CLIL module. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Bligh, S. (2014). The silent experiences of young bilingual learners: A sociocultural study into the silent period. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense.

Bovellan, E. (2014). Teachers’ beliefs about learning and language as reflected in their views of teaching materials for content and language integrated learning (CLIL). Jyvaskyla: University of Jyvaskyla. Retrieved from https://jyx.jyu.fi/dspace/bitstream/ handle/123456789/44277/978-951-39-5809-1_ vaitos20092014.pdf?sequence =1.

Coyle, D., Hood, P, & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL content and language integrated learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coyle, D. (2013). Listening to learners: An investigation into ‘successful learning’ across CLIL contexts.

International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 16(3), 244-266.

Cummins, J. (1982). Tests, achievement, and bilingual students. FOCUS, 9, 2-9.

Cummins, J. (2008). BICS and CALP: Empirical and theoretical status of the distinction. In E. Shohamy & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education, Volume 7: Language testing and assessment (2nd ed.; pp. 71-83). Boston, MA: Springer.

Cummins, J. & Man Y-F E. (2007). Academic language: What is it and how do we acquire it? In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 797-810). Boston, MA: Springer.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2007). Discourse in content and language integrated (CLIL) classrooms. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2008). Outcomes and processes in content and language integrated learning (CLIL): Current research from Europe. In W. Delanoy & L. Volkmann (Eds.), Future perspectives for English language teaching (pp. 139-157). Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2011). Content and language integrated learning: From practice to principles? Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31, 182-204.

de Graaff, R., Koopman, G. J., Anikina, Y, & Westhoff, G. (2007). An observation tool for effective L2 pedagogy in content and language integrated learning (CLIL). The International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), 603-624.

Drury, R. (2013). How silent is the ‘silent period’ for young bilinguals in early years setting in England? European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 21(3), 380-391.

Eurydice. (2012). Key data on teaching languages at school in Europe 2012. Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency. European Commission. Retrieved from http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/ eurydice/documents/key_data_series/143EN.pdf.

García, O., Ibarra Johnson, S., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The translanguaging classroom-leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon.

Habrat, A. (2013). The effect of affect on learning: Selfesteem and self-concept. In E. Piechurska-Kuciel & E. Szyman'ska-Czaplak (Eds.), Language in cognition and affect, second language learning and teaching (pp. 239-253). Berlin: Springer.

Hillyard, S. (2011). First steps in CLIL: Training the teachers. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 4(2), 1-12.

Hüttner, J., & Smit, U. (2014). CLIL (content and language integrated learning): The bigger picture. A response to: A. Burton (2013). CLIL: Some reasons why... and why not. System, 41(2013): 587-597. System, 44, 160-167.

Honig, I. (2010). Assessment in CLIL: Theoretical and empirical research. Saarbrucken: VDM Verlag.

Kopperoinen, A. (2011). Accents of English as a lingua franca: A study of Finnish textbooks. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 21(1), 71-93.

Krashen, S. D. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. New York, NY: Longman.

Krashen, S., & Brown, C. L. (2007). What is academic language proficiency? STETS Language and Communication Review, 6(1), 1-4.

Lightbown, P M., & Spada, N. (2008). Form-focused instruction: Isolated or integrated? tEsOL Quarterly, 42(2), 181-207.

Llinares, A., Morton, T, & Whittaker R. (2012). The roles of language in CLIL. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Milovanov, R. (2009). The connectivity of musical aptitude and foreign language learning skills: Neural and behavioral evidence. Anglicana Turkuensia No 27. Turku: University of Turku. Retrieved from http://www.dona. fi/bitstream/handle/10024/50249/diss2009milovanov. pdf?sequence=1.

Milovanov, R., Tervaniemi, M., & Gustafsson, M. (2004). The impact of musical aptitude in foreign language acquisition. Conference paper for Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Music Perception & Cognition. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/ download?doi=10.1.1.476.1488&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

NCC. (2016). The national core curriculum for basic education 2014. Publications 2016:5. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education.

Nikula, T, & Jarvinen, H.-M. (2013). Vieraskielinen opetus Suomessa [Instruction in a foreign language in Finland]. In L. Tainio & H. Harju-Luukkainen (Eds), Kaksikielinen koulu - tulevaisuuden monikielinen Suomi [Bilingual school—the multilingual future Finland] (pp. 143-166). Jyvaskyla: Jyvaskylan yliopistopaino.

Mehisto, P, Marsh, D., & Frigols, J. M. (2008). Uncovering CLIL: Content and language integrated learning in bilingual and multilingual education. Oxford: Macmillan Education.

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2012). CLIL research in Europe: Past, present, and future. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15(3), 315-341.

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2017). Stopping the “pendulum effect” in CLIL research: Finding the balance between Pollyanna and Scrooge. Applied Linguistics Review, 8(1), 79-99.

Pérez-Vidal, C. (2007). The need of focus on form (FoF) in content and language integrated approaches: An exploratory study. Volumen Monográfico, 39-54.

Pihko, M.-K. (2007). Mina, koulu ja englanti: Vertaileva tutkimus englanninkielisen sisallónopetuksen ja perinteisen englannin opetuksen affektiivisista tuloksista [Me, school and English: A comparative study of the affective outcomes of English teaching in Content and Language Integrated (CLIL) classes and in traditional EFL classes]. Jyvaskyla: University of Jyvaskyla.

Pihko, M.-K. (2010). Vieras kieli kouluopiskelun

valineena: Oppilaiden kokemuksista vihjeita CLIL-opetuksen kehittamiseen [Foreign language as a medium of school study: implications of pupils’ experiences for development of CLIL instruction]. Jyvaskyla: Jyvaskylan yliopisto.

Rahman, H. (2012). Finnish pupils’ communicative language use of English in interviews in basic education grades 1-6. Research Report 340. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

Rahman, H. (2013). Viestinnallinen CLIL-opetus [Communicative CLIL instruction]. In T Wewer (Ed.), CLIL liitoon [Make CLIL soar] (pp. 40-44). Publication of the Teacher Training School of Turku University. Turku: University of Turku.

Rantala, T, & Maatta, K. (2012). Ten thesis of joy of learning at primary schools. Early Childhood Development and Care, 182(1), 87-105.

Scarcella, R. (2003). Academic English: A conceptual framework. Technical Reports. University of California Linguistic Minority Research Institute: UC Berkeley.

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2006). The challenges of academic language in school subjects. In I. Lindberg & K. Sandwall (Eds), Spráket och Kunskapen: Att Lara pa sitt Andrasprák ISkola och Hógskola [Language and sciences: To learn one’s second language at school and university] (pp. 47-69). Goteborg: Goteborgs Universitet Institutet for Svenska som Andrasprák.

Schmidt, R. (1993). Awareness and second language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 13, 206-226.

Seikkula-Leino, J. (2007). CLIL learning: Achievement levels and affective factors. Language and Education, 21(4), 328-341.

Shabani, B. M., & Torkeh, M. (2014). The relationship between musical intelligence and foreign language learning: The case of Iranian learners of English. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 3(3), 26-32.

Slattery, M., & Willis, J. (2001). English for primary teachers: A handbook of activities and classroom language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, K., & Tillema, H. (2003). Clarifying different types of portfolio use. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(6), 625-648.

Snow, C. E., & Uccelli, P (2009). The challenge of academic language. In D. R. Olson & N. Torrance (Eds), The Cambridge handbook of literacy (pp. 112-133). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Swinney, R., & Velasco, P (2011). Connecting content and academic language for English learners and struggling students. Grades 2-6. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Van Canh, L., & Renandya, W A. (2017). Teachers’ English proficiency and classroom language use: A conversation analysis study. RELC Journal, 48(1), 67-81.

Wewer, T (2014a). Assessment of young learners’ English proficiency in bilingual content instruction CLIL. Publications of Turku University B-385. Turku: University of Turku.

Wewer, T (2014b). Academic language: Raising awareness of subject-specific literacies. A Capstone Project Report. Retrieved from http://www.fulbright. fi/sites/default/files/Liitetiedostot/Stipendiohjelmat/ Suomalaisille/da_fy14_capstone_project_wewer_ finland.pdf .

Wewer, T (2015). Portfolio as an indicator of young learners’ English proficiency in mainstream English instruction (EFL) and bilingual content instruction (CLIL). Turku: University of Turku.

Zwiers, J., & Crawford, M. (2011). Academic

conversations. Classroom talk that fosters critical thinking and content understandings. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

University of Turku, Turku, Finland. taina.wewer@utu.fi

Iowa State University introduces the basics of Bloom’s taxonomy concisely and practically: http://www.celt.iastate.edu/ teaching/effective-teaching-practices/revised-blooms-taxonomy, retrieved April 22, 2017.

See e.g. http://www.teachingvillage.org/2010/05/23/how-to-create-a-jazz-chant/, retrieved April 23, 2017.

See http://www.pearsonlongman.com/young_learners/pdfs/ classroomlanguage.pdf for a basic set of teacher classroom talk, retrieved April 23, 2017.

See e.g.,www.wordle.net, retrieved April 24, 2017

See e.g.,www.webquest.org/ for all-encompassing information and http://prezi.com/mtpqbfbfh2gx/the-use-of-web-quests-in-clil-settings/ for examples in CLIL settings; http://zunal. com/ is a free and functional platform for creating WebQuests, all links retrieved April 24, 2017.

See https://socrative.com/, retrieved April 24, 2017. The basic version of Socrative is free of charge. It allows immediate feedback to the testee in form of correct answers and teacher-written explanations.

See https://getkahoot.com/, retrieved April 24, 2017. Also Kahoot is free and so user-friendly that young language learners are capable of creating their own quizzes.