DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.87Published:

2010-07-01Issue:

Vol 12, No 2 (2010) July-DecemberSection:

Pedagogical InnovationsStruggling for change in chilean EFL teacher education

La lucha por un cambio en la educación de los docentes de inglés como lengua extranjera en Chile

Keywords:

formación inicial docente, innovación curricular, cambio y resistencia (es).Keywords:

EFL teacher education, curriculum innovation, change and resistance (en).Downloads

References

Bartholomew, S.; Sandholtz, J. Competing views of teaching in a school-university partnership. Teaching and Teacher Education, (v. 25, p. 155-165, 2009).

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Canagarajah, A.S. (1999) Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Canagarajah, A.S. Globalization, methods, and practice in periphery classrooms. In: Block, D.; Cameron, D.(2002) Globalization and language teaching ( p. 131- 150). London: Routledge.

Clavijo, A. (2007). Prácticas innovadoras de lectura y escritura. Bogotá: Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas.

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Harmond- sworth: Penguin.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Gimenez, T. Global citizenship and critical awareness of discourse. In: Sheehan, S. (2008) (Eds.). Global citizenship in the English language classroom (p. 48-53). London: The British Council.

Kennedy, C. (1988). Evaluation of the management of change in ELT projects. Applied Linguistics 9.4, (329342).

Giroux, H. (1981). Ideology, culture and the process of schooling. Lewes: Falmer Press.

Graddol, D. (1997). The future of English. London: The British Council.

Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology and social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mackay, S. (2003).Teaching English as an international language: the Chilean context. ELT Journal, (v. 57, n. 2, p. 139-148).

Malderez, A.; Wedell, M. (2007). Teaching teachers: processes and practices. London: Continuum.

Pennycook , A. (1994). The cultural politics of English as an international language. London: Longman.

Pennycook , A. (2001). Critical applied linguistics: a critical introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

PREAL. (2008). La reforma latinoamericana entre dos clases de políticas educativas. Formas & Reformas de la Educación: Serie Políticas, (n. 23, p. 1-4, Mar. 2006). Available at: <http://www.preal.org/Archivos/Bajar.asp?Carpeta=Preal Publicaciones/Resumenes Ejecutivos/Serie Políticas/&Archivo=POLITICAS_23. pdf>. Accessed on: 01 Nov.

Sharifian, F. (ed.) (2009) English as an International Language. perspectives and Issues. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Shor, I. (1992). Empowering education: critical teaching for social change. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Smith, P.; West-Burnham, J. (1993). Mentoring in the effective school. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Snow, M.; Met, M.; Genesee, F. (1989). A conceptual framework for the integration of language and content in second/foreign instruction. Tesol Quarterly, (v. 23, n. 2, p. 201-217, June)

Wedell, M. (2009). Planning for educational change putting people and their contexts first. London: Continuum.

Wenger, E. (2007). Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2010 vol:12 nro:2 pág:110-118

Pedagogical Innovations

Struggling for Change in Chilean EFL Teacher Education

La lucha por un cambio en la educación de los docentes de inglés como lengua extranjera en Chile.

Mary Jane Abrahams [1]; Miguel Farias [2]

[1] English Department Head, School of Education Universidad Alberto Hurtado, Santiago, Chile E-mail: mabraham@uahurtado.cl

[2] Professor, Linguistics and Literature Universidad de Santiago de Chile, Santiago, Chile E-mail: miguel.farias@usach.cl

Abstract

We here report on the processes of designing and trying to implement curriculum innovations in English as a foreign language (EFL) teacher education in Chile. This curriculum innovation project involved academics from six universities where problems such as a divorce between training in English linguistics and education, lack of language achievement standards and students’ low scores in international exams were found to be common to all six EFL teacher education programs. All of this amidst a general opinion (shared by parents, teachers, politicians, etc.) that Chile is immersed in an educational crisis without any easy solution. In this context an urgent need arises for an innovative and very creative design to change the curricula at universities so that the country can raise the quality in foreign language education. The aim is for language education to have a real impact in the school communities. Having Critical Pedagogy as one of the main supporting models, this design we report on is based on the idea that the traditional curriculum is a pedagogy that transmits inflexible social truths; consequently, this proposal incorporates participatory and reflective instructional activities, such as situated and transformed practice and critical framing. This innovative curriculum also includes on-going education, inviting classroom teachers to be part of Methodology classes, Reflection Workshops, early Teaching Practice, and Mentoring as a key practice in creating and consolidating communities of interest in language education.

Key words: EFL teacher education, curriculum innovation, change and resistanceResumen en español

Resumen

En este trabajo informamos sobre el proceso de diseño e implementación de innovaciones curriculares en la formación inicial de profesores de inglés en Chile. Este proyecto de innovación curricular estuvo a cargo de académicos de seis universidades, en las cuales se diagnosticaron problemas comunes como el divorcio entre la formación en la especialidad y la formación pedagógica, falta de estándares de desempeño en la lengua meta y bajos puntajes en mediciones internacionales. Todos estos problemas ocurren en el contexto de una crisis general del sistema educativo chileno, en medio de la cual surge la necesidad urgente de un diseño creativo e innovativo que permita elevar la calidad de la educación en lengua extranjera. El diseño propuesto tiene a la pedagogía crítica como su principal modelo y se basa en la premisa de que el currículo tradicional transmite verdades sociales inflexibles. Consecuente con estas ideas, esta propuesta incorpora actividades de reflexión y participación críticas, como es la práctica contextualizada y transformativa, y la educación continua donde se invita a maestros de aula a participar en las clases de Metodología y en los Talleres de Reflexión. El diseño tiene también a la mentoría y la práctica temprana como elementos claves en la creación y consolidación de comunidades de interés en la educación lingüística profesional.

Palabras clave: formación inicial docente, innovación curricular, cambio y resistencia

Introduction

There is no doubt that most countries in Latin America are undergoing serious challenges in their educational systems as the forces of globalization and international standards pose high demands on national policies. We contend that language teacher education plays an important role in providing our societies with teachers endowed with a clear role as social actors and intercultural agents of change. The power of language to contest and critique anachronistic epistemologies and curricula and to struggle against such social evils as discrimination, injustice and domination should be tapped as a means to social transformation.

In what follows, we describe the main steps that six Chilean universities have undertaken in coming up with a plan of study for initial teacher training for English language educators. We start with a view of the context of the innovation and a diagnostic view of common problems found in the six universities. We continue with a description of the guiding principles or models that inform our proposal, and we then describe the organizing principles of the profile, followed by a discussion of the two main curriculum strands that have been designed as integrating components. We finish with the tentative steps for the implementation of this innovation.

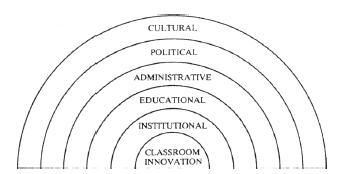

The catch words we used for the title of our presentation at the Conference on Language Teacher Education were change and resistance, as we wanted (naively) to understand the process of curriculum innovation dialectally, i.e., as a struggle between two diverging ideological positions. However, such a metaphor runs short when we try to bring into this paper the complexity of the numerous personal, political, institutional and cultural issues intervening in the design, formulation and implementation stages of a new curriculum for initial teacher education in the Chilean context. In the literature on curriculum change, we found that the diagram by Kennedy (1998) reflects to some extent such complexity:

Fig. 1. The hierarchy of interrelating subsystems in which an innovation has to operate (Kennedy, 1988: 332).

As any visual representation of a complex phenomenon, Kennedy’s shows only the tip of the iceberg of the many subsystems that may initiate, design, carry out and evaluate projects involving curriculum innovation. It serves the purpose of highlighting the idea that the main aim is classroom innovation where the effects can be replicated to large populations. In our case, we are aiming at introducing changes in English as foreign language (EFL) teacher education in several universities located in four different regions in Chile. However, and to contextualize this diagram, we need to acknowledge that foreign language teaching policies are part of educational policies, which in most Latin American countries can be of two major types: those oriented to expand the system and provide access to the population and those geared to improve the quality and efficiency of the system. According to a 2006 Report by the Interamerican Development Bank, “the formulation of education policy in the region is disproportionately skewed towards expansion and access, rather than quality and efficiency” (PREAL, 2006, p. 1)(translation by editor).

At the local level, we also see that the neoliberal policies Chile has embarked on are leaving quality standards in the hands of the market. We have seen in the last few years a proliferation of English language teaching training programs set up primarily by some private universities. Our concern is that such programs seem to understand language education has a technical training component that disregards both the role of language as a social practice that constructs communities of interest and practice and the importance of (action) research in improving the quality of language learning.

The superordinate objective behind this project was to contribute to a higher quality of English language education in the Chilean school system by introducing situated and informed changes in initial teacher education. Such enterprise becomes more and more relevant given the fact that languages play a fundamental role for social development and aid in preventing human isolation and fostering intercultural collaborations.

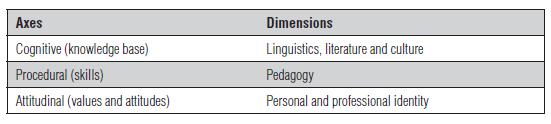

As for the genesis of this project, several higher education institutions offering EFL teacher education and with a tradition in EFL programs had created a consortium around the shared idea of monitoring and assuring the quality of teacher education. Such initiative was motivated by the “marketization” of teacher education propitiated by neoliberal policies that were slowly and only recently introducing quality control measures. As a result of such independent collaborative work, we identified three axes for the profile of a newly qualified teacher of English: a) the knowledge level of the language and culture, the Chilean curriculum goals and programs, the students’ learning processes, and the personal learning process; b) the skills; and c) the personality traits and attitudes an ideal teacher should have. Later on, through the work of a larger group involving six universities, they became the cognitive, procedural and attitudinal axes that were operationalized in three dimensions (see Table 1).

Surely, there were other factors behind such intentions for change, of which we share the following, mentioned by Wedell (2009, p. 14–16):

- To enable the national educational system to better prepare its learners for a changing national and international reality.

- To make the education system more clearly accountable for the funding it receives.

- To increase equality of opportunity within society as a whole.

- To use the announcement of educational changes for some kind of short-term political advantage.

When these factors are contextualized in the Chilean reality, we observe that the shift from a traditional conception of the English language as associated primarily to UK and US standards to an understanding of English as an international language (Pennycook, 1994) needed due attention to accommodate language teacher education to an increasingly diversified and multicultural world. As Chile’s economy as opened to the world through various trade agreements, there was a need for qualified bilingual professionals. Consequently, the Chilean government started investing highly in English language teaching through the Ministry of Education’s English Open Doors program and promoting several other policies that provided funding for in-service training, graduate studies, and the Semester Abroad program, among others.

In this context, a small group of Chilean academics working in traditional English language education programs has united in a collaborative project to reengineer initial teacher training for English teachers to meet international standards in language proficiency, on one hand, and high quality in teacher professional development, on the other. These two objectives, in our opinion, may pave the way and eventually assure the accountability requirements that have program accreditation as one of its measuring standards. In turn, we are very much aware that, as Bartholomew and Sandholtz (2009, p. 155) have put it, “teachers’ professional learning becomes important not only in preparing candidates for a teaching position but also throughout their careers in the classroom.”

Diagnosis

The six universities identified the following problems to be common to all of them:

(a) Divorce between training in the disciplines (English linguistics) and in education: Structurally speaking, in most universities the Language Department, or its equivalent, is in charge of providing the courses in English linguistics and the disciplines in general, whereas it is the Department of Education, or its equivalent, the one responsible for offering the courses in education. This weakness has been confirmed by the reports from the accreditation process some of these English teaching programs have gone through.

(b) Lack of language achievement standards: It was not until recently, when some sort of measuring standard was needed to justify the major investments in teacher training provided by the Ministry of Education, that the need for an international standard reference was required to assess the language proficiency of teachers and students. Even though there might be some natural differences across training programs, there is consensus in the professional field as to the concept of proficiency, associated primarily to that of English as an international language (Pennycook, 1994; Mackay, 2003; Sharifian, 2009).

(c) Low scores in pilot Cambridge test given by MINEDUC to a sample of teachers and students: ALTE III for teachers and KET/PET to students in 2004. The results for students were so weak a new level, below threshold, had to be created to classify them.

(d) Very inflexible curricula: Chile has traditionally followed what we can call a “professionalizing curriculum” that introduces the student from the very first year in courses leading to the specialization, as opposed to other systems in which the students are offered options from which they can later choose. Again, the possibilities and affordances of the two systems have to do with economic policies and with the social status accorded to language teaching.

(e) Outdated, uncommitted teacher trainers: Associated to the issue of the social status of language teaching (and teaching profession in general), this is a major issue in most universities. Language teaching dwells in the terra incognita between the social sciences, the humanities, and the field of education, all of which are treated differentially when it comes to funding for research and other grants. Referring to the variety of factors underlying the teaching profession, Malderez & Wedell (2007) describe teaching as a complex and open skill. There is no right answer or “way” of doing something. Therefore the starting point should not be a checklist of skill based competencies denoting a blueprint of professional practice, but a model of growth and personal development towards a shared construction of effective teaching and learning and an identity as an autonomous professional. Teacher trainers in Chilean universities lack this today.

Models or guiding principles

In looking at models that would provide contextualized and updated foundations to build an innovative curriculum, the current literature in the field mentions:

(a) Integrated skills. Teaching the language as a whole and providing meaningful connections to other subjects in the curriculum. As access to the foreign language is more and more available through videos, Internet, and international traveling, the possibilities of exposure to the English language no longer depend just on the teacher and the classroom.

Meaning provides conceptual or cognitive hangers on which language functions and structures can be hung. In the absence of real meaning, language structures and functions are likely to be learned as abstractions devoid of conceptual or communicative value. If these motivational and cognitive bases are to be realized, then content must be chosen that is important and interesting to the learner (Snow, Met & Genesee, 1989, p. 202).

Integrating the skills and looking at language learning as a means to fully participate in wider communities of interest and practice (Wenger, 2007) requires an effort from the language educator to engage learners in meaningful activities in and out of the classroom. Seeing the contribution that foreign language learning affords for cognitive and social development is essential in this respect.

(b) Content-based learning. Educating and training critical pedagogues through the use of the English language. Providing learners with more and more opportunities to practice the language and engage in meaningful uses of English is necessary. In this respect, Snow, Met & Genesee (1989, p. 203-204) mention that “…as language teachers try to make language meaningful by providing contextual cues and supports, too often their attempts bring the learner into cognitively undemanding situations.” Thus, although it is easy for children to learn to label colors and shapes, for example, activities in the language class rarely require students to use this new language knowledge in the application of higher order thinking.

(c) Critical pedagogy. Both because language is a powerful tool in the construction of intersubjectivities and because we assume our profession as situated and committed pedagogues, the principles we have found in the works of Freire (1972, 1998), Giroux (1981), Canagarajah (1999, 2002) and Pennycook (1994, 2001) have proved to be valuable references in our understanding of the role of education and language teaching in the Latin American context.

A definition of critical pedagogy by Shor (1992, p. 129), reads: “habits of thought, reading, writing, and speaking which go beneath surface meaning, first impressions, dominant myths, official pronouncements, traditional clichés, received wisdom, and mere opinions, to understand the deep meaning, root causes, social context, ideology, and personal circumstances of any action, event, object, process, organization, experience, text, subject matter, policy, mass media or discourse.”

Some of the issues inspired by these principles that we attempt to include are: (i) becoming aware of problems in particular school communities and working collaboratively on projects attempting to solve such problems; (ii) critical awareness of the power of language in the construction of knowledge and of the tensions caused by the use of English as an international language; (iii) working closely with the school communities to provide support in building notions of democratic citizenship (Gimenez, 2008).

(d) Mentoring.The newly qualified teacher (NQT) and the novice teacher both require someone to advise and support them along the different stages of their professional development: someone with whom to engage in the ongoing reflective discussion about the teaching-learning process. Novice teachers need a mentor teacher, who knows how to support, guide and supervise them while doing their practicum (the much needed scaffolding in the Vygotskyian model). Similarly, NQTs need a friendly knowing hand that will provide them with awareness, support, and company. This accompanying figure is the mentor. There are many ways of defining this role: “The role of the mentor is to act as ‘wise counselor’, guide, and adviser to younger or newer colleagues” (Smith & West-Burnham, 1993, p. 8). Mentoring, then, with its strong emphasis on the reflective individual and committed one-to-one relationship between mentor and mentee, emerges as the natural, valid path to developing aware, reflective, and critical in-service teachers in the Chilean educational system, and in this way helping to bridge the gap between university education (instead of training) and school communities. Thus, universities and schools work together, creating partnerships, in order to significantly improve teaching practices in classrooms, with a view to having a positive impact in the language learning outcomes of learners and developing critical autonomous citizens who will be aware of their role in society.

(e) Communities of interest and practice.Teachers usually work as isolated, separate individuals. They do not seem to be aware of the power and richness of group work in terms of learning through sharing and reflective discussion for better planning and preparation. Classroom practice can indeed be a very lonely kind of practice. Therefore, future teachers must learn how working with others will provide them with valuable support to turn the theory learned at university into effective classroom practice. Additionally, they will learn how working with peers on classroom issues can help them find solutions or other better alternatives that, until then, seemed impossible to deal with. Therefore, teachers reflect together on theoretical perspectives on action research and, especially, come up with practical collaborative ideas from the teachers’, not the researchers’, point of view: “directing their research efforts towards change, not only at the classroom level, but also at the broader institutional level” (Burns, 1999, p. 2).

(f) Teacher and student mobility. The possibility to share teaching capabilities among participating training programs follows a postmodern tendency to share and distribute resources. A relatively common curriculum enables student mobility as this experience can be part of SCT (Sistema de Créditos Transferibles), a project launched by some Chilean universities.

(g) Network-based learning. A virtual platform will be implemented and designed to provide opportunities to (i) practice and share ICT applications for language learning and teaching; (ii) work on projects collaboratively among participating universities; (iii) expand the reach of the project to other programs in Latin America and other parts of the world with similar interests; and (iv) serve as a forum for activities exploring the intercultural dimension of language learning.

The new profile

The profile underlying this initial teacher training curriculum is articulated around three dimensions and three axes:

At the intersection between axes and dimensions are the macro competences the NQT should attain, which are more finely tuned in the descriptions, generic activities, learning outcomes and specific competences in each curricular activity (course) the design contains. The integrated curriculum contains two major encompassing strands, (a) English language and (b) Methodology. In turn, (a) English language includes the following sub-strands: (i) Integrated skills: reading, writing, speaking and listening, (ii) Linguistic components: lexico-grammar, pronunciation, (iii) Culture and literature, and (iv) Reflective and critical skills. The (b) Methodology strand includes (i) Reflection workshops, (ii) Field experiences, (iii) Practicum, (iv) Action Research, and (v) Methods. The Methods sub strand includes: (I) Teaching/learning strategies, (II) Classroom management skills, (III) ICTs and other resources, and (IV) Assessment and evaluation.

The models chosen, the organization of the profile and the ensuing plan of studies reflect a tacit compromise between two views or, as Holliday (1994) calls them, two professionalacademic paradigms, the collectionist and the integrationist. Holliday (1994: 72) posits that the collectionist view favors a “didactic, content-based” pedagogical practice, whereas the integrationist paradigm would espouse a “skills-based, discovery-oriented, collaborative” pedagogy.

Steps to implementation

As the literature mentions, the actions to be taken in implementing this new curriculum are crucial. They include what we have called “academic retreats” in which teams of teachers from all participating institutions work collaboratively under the guidance of an expert in formulating and creating the activities and resources for each strand. Another action is the implementation of the virtual platform according to the specific requirements of the curriculum. The idea is to have technology serve as the principles and purposes of the teacher education processes rather than accommodating already existing software.

A very important action is the training required for future staff in accordance with the main principles underlying the curriculum. We venture that interdisciplinary work is the best option in providing new perspectives for language teaching and learning. Additionally, an efficient curriculum needs to have progress indicators set at crucial points in the curriculum as a means to evaluate progress and produce the adjustments required.

Finally, the human factor is an essential element to be taken into consideration: the success of this innovation would depend on the commitment, compromise and perseverance of the academics in charge of taking this boat to secure ports and of other actors involved providing support for such enterprise. All these actors will play a myriad of roles, some of which, following Lambright and Flynn’s taxonomy (in Kennedy 1988: 334), are adopters (e.g. government officials), implementers (e.g. teachers), clients (e.g. students), suppliers (e.g. materials writers), entrepreneurs (e.g. ‘change agents’), and/or resisters (e.g. any of the examples above). Wedell (personal communication) has mentioned that for such a project to be successful in the first years of implementation there needs to be at least one or two people carrying the spirit of the project and lobbying for it at levels where support is needed.

Final considerations

Preparing generations of teachers to face the future can no longer be an isolated endeavor. Traditionally, teacher educators may have worked “from their university desks”, so to say, but the fast pace of changes and the need to democratize the education processes require collaboration among educators to contrast, evaluate, implement and assess the best options for language teacher education. Apparently, we are in tune with other such similar projects in Latin America; for example, Clavijo (2007, p. 25) comments that in her study on literacy practices in Colombia the most relevant way to understand curriculum innovation was as a modernization of the school, since such conception incorporates the social context of the educational intervention as part of the innovation.

Our experience constitutes a pioneering effort to bring six universities together with the common objective to improve the quality of English language teaching education in Chile. By sharing resources and human capabilities these six institutions enforce their missions and visions in the pursuit of quality standards for language teacher education.

References

Bartholomew, S.; Sandholtz, J. Competing views of teaching in a school-university partnership. Teaching and Teacher Education, (v. 25, p. 155-165, 2009).

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Canagarajah, A.S. (1999) Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Canagarajah, A.S. Globalization, methods, and practice in periphery classrooms. In: Block, D.; Cameron, D. (2002) Globalization and language teaching ( p. 131- 150). London: Routledge.

Clavijo, A. (2007). Prácticas innovadoras de lectura y escritura. Bogotá: Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas.

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Gimenez, T. Global citizenship and critical awareness of discourse. In: Sheehan, S. (2008) (Eds.). Global citizenship in the English language classroom (p. 48-53). London: The British Council.

Kennedy, C. (1988). Evaluation of the management of change in ELT projects. Applied Linguistics 9.4, (329–342).

Giroux, H. (1981). Ideology, culture and the process of schooling. Lewes: Falmer Press.

Graddol, D. (1997). The future of English. London: The British Council.

Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology and social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mackay, S. (2003).Teaching English as an international language: the Chilean context. ELT Journal, (v. 57, n. 2, p. 139-148).

Malderez, A.; Wedell, M. (2007). Teaching teachers: processes and practices. London: Continuum.

Pennycook , A. (1994). The cultural politics of English as an international language. London: Longman.

Pennycook , A. (2001). Critical applied linguistics: a critical introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

PREAL. (2008). La reforma latinoamericana entre dos clases de políticas educativas. Formas & Reformas de la Educación: Serie Políticas, (n. 23, p. 1-4, Mar. 2006). Available at: <http://www.preal.org/Archivos/ Bajar.asp?Carpeta=Preal Publicaciones/Resumenes Ejecutivos/Serie Políticas/&Archivo=POLITICAS_23. pdf>. Accessed on: 01 Nov.

Sharifian, F. (ed.) (2009) English as an International Language. Perspectives and Issues. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Shor, I. (1992). Empowering education: critical teaching for social change. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Smith, P.; West-Burnham, J. (1993). Mentoring in the effective school. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Snow, M.; Met, M.; Genesee, F. (1989). A conceptual framework for the integration of language and content in second/foreign instruction. Tesol Quarterly, (v. 23, n. 2, p. 201-217, June)

Wedell, M. (2009). Planning for educational change – putting people and their contexts first. London: Continuum.

Wenger, E. (2007). Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.

.JPG)