DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/25909398.14227Publicado:

2019-01-02Número:

Vol. 6 Núm. 6 (2019): Enero' Diciembre 2019Sección:

Sección CentralUna Tarea Peculiar

A Peculiar Task

Uma tarefa peculiar

Palabras clave:

rope practice, felt sense, performance, relational dynamic, embodiment (en).Palabras clave:

práctica de la cuerda, sentir sentido, performance, dinámica relacional, incorporación (es).Palabras clave:

prática de corda, sensação de sentimento, desempenho, dinâmica relacional, incorporação (pt).Descargas

Referencias

Fischer Lichte, E. (2014). Theater and Performance Studies. New York, NY. Routledge.

Gendlin, E. T. (1978, 1982, 2003). Focusing. New York, NY: Random House Inc.

Hunter, L. (2016). Sentient Performativities of Embodiment: Thinking alongside the Human. Maryland. Lexington Books.

Hunter, L. (2016). Ethics, performativity and gender: porous and expansive concepts of selving in the performance work if Gretchen Jude and of Nicole Peisl. Palgrave Communications, 2. Article number: 16006 retrieved from. https://www.nature.com/articles/palcomms20166

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3). 575–99.

Levine, P.A. and Phillips, M. (2012). Freedom from pain: discover your body’s power to overcome physical pain. Boulder, CO: Sounds True, Inc.

Noë, A. (2004). Action in Perception. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Noë, A. (2012). Varieties of Presence. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Ridley, C. (2006). Stillness: Biodynamic Cranial Practice and Consciousness. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Rome, D. I. (2014). Your body knows the answer: using your felt sense to solve problems, effect, change, and liberate creativity. Boston, MA, Mass.: Shambhala Publications.

Sills, F. (2008). Das Craniosacrale System. Energetische Anatomie. Textbook, excerpt of a lecture by Franklyn Sills. Milne Institute.

Sutherland, W. (1990). Teachings in the Science of Osteopathy. Anne L. Wales, ed. Fort Worth, Tx: Sutherland Cranial Teaching Foundation. Rudra Press.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

A Peculiar Task*

Una Tarea Peculiar

Uma tarefa peculiar

Nicole Peisl**

Ph.D. Candidate, Graduate Group Performance Studies, University of California Davis. Correo electrónico: nkpeisl@ucdavis.edu

Fecha de recepción: 27 de junio de 2018

Fecha de aceptación: 11 agosto de 2018

Doi: https://doi.org/10.14483/25909398.14227

Cómo citar este artículo:Peisl, N. (2019). Una Tarea Peculiar. Corpo Grafías Estudios críticos De Y Desde Los Cuerpos, 6(6), 54-63. https://doi.org/10.14483/25909398.14227

*Artículo de investigación: This article discusses what I call the “rope practice,” which is based on a performance task in which a rope is integrated with movement. It was first presented in my 2010 choreography Vielfalt.

Este artículo discute lo que llamo “práctica de la cuerda”, la cual está basada en una tarea de un performance en el cual una cuerda es integrada con el movimiento. Ésta fue presentada por primera vez en mi coreografía del año 2010 titulada Vielfalt.

**A dancer, choreographer, and researcher. She joined the Frankfurt Ballet in 2000 and worked with William Forsythe as a member of the Forsythe Company until 2014. Peisl’s trilogy Vielfalt, Ueberblick, and Spielfeld I&II has been staged in Frank- furt, Dresden, Vienna and Munich. Peisl has worked as freelance collaborator with, among others, Anouk van Dijk, Joseph Tmim, the Episode Collective (with Richard Siegal and Prue Lang), and with Daghdha Dance Company (Michael Klien). Nico- le has also worked widely teaching dance: at ImpulsTanz Vienna, LaCaldera Les Corts in Barcelona, Anton Bruckner Privat University of Linz Austria, Justus Liebig University of Giessen in Germany, University of Limerick, and DOCH University of Dance and Circus of Stockholm in Sweden. Peisl is a certified practitioner of Craniosacral body work (Milne Institute) and Somatic Experiencing (Peter Levine). She is currently pursuing a PhD in the Program in Performance Studies at University of California, Davis, California.

Abstract

This article discusses what I call the “rope practice,” which is based on a performance task in which a rope is integrated with movement. It was first presented in my 2010 choreography Vielfalt. This is a novel, rope-based movement activity that affords new possibilities for action, organization, relational dynamics, as well as opportunities for using what Eugene Gendlin calls “felt sense” to generate affect and new trajectories of performance and movement. Engaging with the rope becomes a way for performers to have a bodily experience of the not-yet-known. Felt sense serves as a threshold in which a bodily knowing can be perceived, embodied and articulated. The process of working with the rope through felt sense – this was a central theme of Vielfalt – allows performers to experience and embody change.

Keywords: rope practice; felt sense; performance; relational dynamic; embodiment.

Resumen

Este artículo discute lo que llamo “práctica de la cuerda”, la cual está basada en una tarea de un performance en el cual una cuerda es integrada con el movimiento. Ésta fue presentada por primera vez en mi coreografía del año 2010 titulada Vielfalt. Se trata de una novedosa actividad de movimiento basado en una cuerda que ofrece nuevas posibilidades de acción, organización, dinámica relacional, así como oportunidades para usar lo que Eugene Gendlin llama “sentir sentido” (sentido sentido) para generar afecto y nuevas trayectorias para el performance y el movimiento. Relacionarse con la cuer- da deviene una vía para que performers tengan una experiencia corporal de lo aún no conocido. Sentir sentido (sentido sentido) sirve como un umbral en el cual un conocimiento corporal pueda ser percibido, encarnado y articulado. El proceso de trabajar con la cuerda a través del sentir sentido (felt sense) – este fue un tema central de Vielfalt – permite a los artistas experimentar e incorporar el cambio.

Palabras clave: práctica de la cuerda; sentir sentido; performance; dinámica relacional; incorporación.

Resumo

Este artigo discute o que chamo de “prática de corda”, que é baseada em uma tarefa de performance em que uma corda é integrada ao movimento. Este foi apresentado pela primeira vez na minha coreografia de 2010 intitulada Vielfalt. É uma nova atividade de movimento baseada em uma corda que oferece novas possibilidades de ação, organização, dinâmica relacional, bem como oportunidades para usar o que Eugene Gendlin chama de “sentir sentido” (sentido sentido) para gerar afeto e novas trajetórias para o performance e movimento. Relacionar-se com a corda torna-se uma maneira de os performers terem uma experiência corporal do que ainda não é conhecido. Sentir sentido (sentido sentido) serve como um limiar no qual um conhecimento corporal pode ser percebido, encarnado e articulado. O processo de trabalhar com a corda através do sentir sentido (felt sense) - este foi um tema central do Vielfalt - permite aos artistas experimentar e incorporar a mudança.

Palavras-chave: prática de corda; sensação de sentimento, desempenho, dinâmica relacional, incorporação.

In this article I explore what I call the “rope practice.” This practice is based on a distinct performance task in which the handling of a rope is integrated with movement. It was first put on display in my 2010 choreographic piece Vielfalt. By working with rope in many sessions as both participant and facilitator, I came to observe that performers experience change when they work with unusual materials not often incorporated into dance. This paper is at once an exploration of the ways the rope organizes us, and also a documentation of the process of working with rope in Vielfalt.

The practice itself is a novel, rope-based movement task that affords new possibilities for action, organization, relational dynamics, as well as opportunities for using what Eugene Gendlin (1978) calls “felt sense” to generate feeling, affect, and new trajectories of performance and movement. The duration of the practice can vary, but it usually ranges from ten minutes to an hour or more. It requires the performers to engage in a relational dynamic with the rope as a not-known material, with each other, and with the audience (if there is one). The process of working with the rope through felt sense helps performers fine-tune this situated, relational, dynamic activity; it also allows performers to experience and embody change.

Immersing in Felt Sense

Felt sense is a term coined by philosopher and psychologist Eugene Gendlin, which he describes as, “a process in which you make contact with a special kind of…bodily awareness.” (1982, 11; 2003, 31). Felt sense is deployed so that one may immerse oneself in a situation (here the rope task) through a bodily sensing of something that is implicit in the situation.1 The act of immersing through felt sense allows a bodily knowing to arise and emerge from the situation. The situation is relational and dynamic, and as such always changing and leading into novel unknown relations and dynamics that yet hold kinship.2 Coming into a bodily knowing of this unknown may lead to bodily felt “aha!” moments and new trajectories of movement (Rome, 2014, 57, 104). As such felt sense enables performers to open themselves to the embodiment of a process of change. According to David Rome, a practitioner and teacher of Gendlin’s method, “Finding the felt sense allows us to bring a deeper kind of knowing to…problems, decisions, and creative challenges” (Rome, 2–14, 36). In the setting of rope practice, finding the felt sense allows one to open affectively to creative challenges and changes that may occur as one handles and tries to cope with the rope. The rope worker must engage with a not-knowing, and is invited to achieve a situated relational embodiment. In this practice, I find it important to utilize felt sense by attuning one’s awareness to the materials, environment and fellow participants. This leads to an expansion of possibilities, or a moving toward an unknown, that may at first be bewildering: a gentle disruption of expectations. In this way, we are lured away from preconceived expectations and are able to enjoy new bodily experience and affect. Felt sense can thus help us intuit novel trajectories in movement tasks. In Vielfalt it is necessary to use felt sense in order to cope with this situated movement task.

Holding the Rope

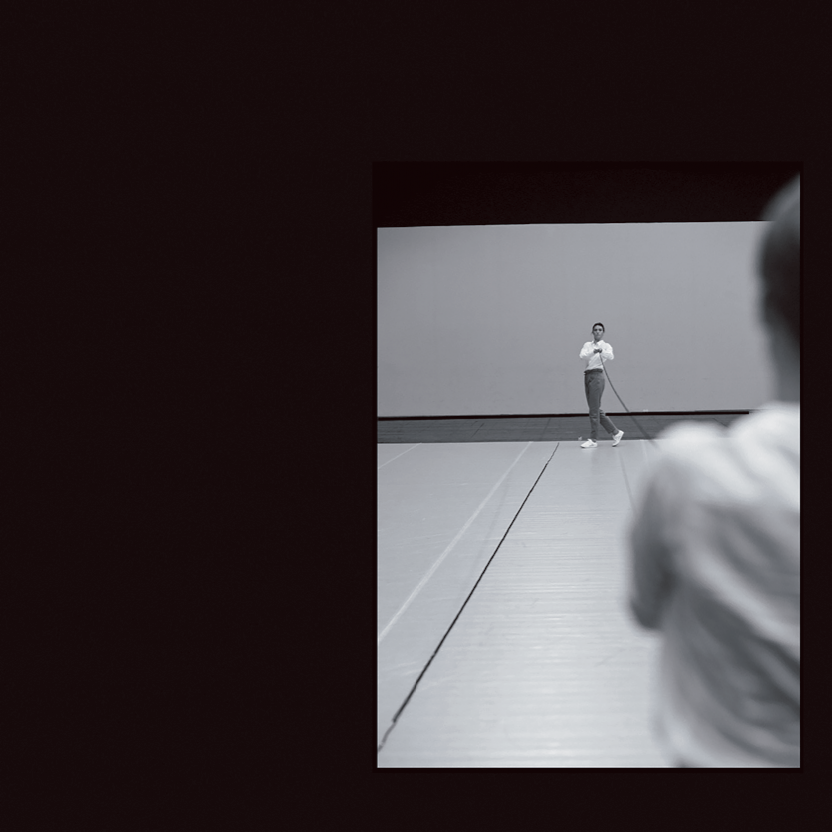

For this article, I will first discuss a later critical phase in the rope practice as it was carried out in the making of Vielfalt. Then I will return to the beginning stages of the rope practice. The critical phase discussed here occurs when the two dancers face each other holding a nine-meter black rope suspended between them. When there is an audience, they sit on two rows of benches parallel to each other, and to the rope, on either side of the performers. The performers suspend the black rope at chest level, at was is roughly the audience’s eye level. Throughout the practice there is no direct verbal or bodily cue between the two performers. The rope is held taut, forming a line. To maintain the rope’s tension to form this taut line, the performers must engage their skill, concentration, and a bodily attunement to the rope and each other. Bodily attunement means bringing intention, concentration, and an openness to the unknown in the current situation into an exchange, or a conversation, on a bodily level. Bodily attunement is a willingness to move and be moved by the expression of the materials, environment, and participants, and is the expression of our felt sense; this bodily attunement through felt sense “utilizes the language of body-mind communication and serves as a kind of radar or navigation system, letting us know instantly about elements of our internal and external environments and how they are affecting us in the current moment” (Levine & Phillips, 2012, 33). It is a relational attunement through felt sense to the different elements at play in the task.

The performers must work hard to keep the rope level and still, to limit its tendency to wobble and bob and vibrate and swing. Utilizing felt sense with every shift of their weight, they seek to modulate the rope and to keep stillness the focus of the performative activity. This shifting and modulating builds a shared intensity, and the intensity of performance has an affective impact on the performers’ experience. Through felt sense the performers’ bodies, minds, and eyes are attuned to the forces at play, and the felt sense is transmitted to the audience, generating affect in them. When an audience is present, the bodily knowing of the unknown beyond the performers to the observers increases – and they inevitably become participants. In practice situations, even a single observer can become a participant. The presence of an audience also changes context, and therefore heightens awareness of how the activity has a social dimension. This allows the choreography to unfold through an affective contingency, which

Figure 10. Elena Gianotti and Satu Herrala, from a performance of Vielfalt, 2010. Photo: Dominik Mentzos 2010.

CHANGE“emphasizes the involvement of all participants and their influence on the course of the performance, including the interplay between these influences” (Fischer-Lichte, 2014, 20). Within such a setting, the relation among performers, materials, and observers allows for a finely-attuned intensity of the experience. This intensity is the sought-after trajectory of the performance.Holding the rope at audience eye level raises the question, “what exactly does the audience see?” It is at once a rope, a line in space; it can also give rise to an illusion-like sense that the line is drawn on the wall of the room. Thus, the rope itself is optically strange, and seeing it becomes an affective experience of facing the not-known and unknowable because the experience is changing moment to moment, for both the performers and audience. Because of the rope’s wobbly quality, it cannot be perceived as a single, fixed object. Particularly when the rope is brought into the observer’s kinesphere, there is potential for the audience to perceive it not as an external object, but as an element of a shared experience. The activity with the rope unfolds as an entanglement; the rope vanishes as an external object and transforms into a felt, shared activity.As the practice continues through felt sense, there is a sensation that the rope is an extension of the body, that the rope becomes a way to experience a bodily knowing of the unknown. While participants are immersed, the rope does not end at the fingertips. The body reflects on and copes with it, responds to it, as well as to the other participants, and to the audience. In holding the rope taut, and utilizing felt sense, the performers keep the rope steady between them. The aim is to achieve an engaged relational tension and facilitate a stillness in the rope. To keep the rope still, and to make this task the organizing principle of the practice, the performers must themselves embody a dynamic stillness, one which Charles Ridley has described as “an embodied feeling-witness consciousness in which thinking ceases to be your exclusive source for your perception and bodily sensing takes over” (Ridley, 2006, 59; Sutherland, 1990, 285). But the rope’s materiality innately challenges that stillness when suspended in the air. Keeping the rope still calls for a high level of skill. The slightest breath or movement can be seen in the rope. This dynamic stillness is relational, it is not frozen or achieved purely by using muscles to still the rope. On the contrary, to arrive at this stillness is a subtle complicated activity of engaging one’s own midline and simultaneously the dynamic demands of the rope situation. The performers’ attention is not only directed at the rope, or to themselves, or the other participant, or the audience, but to all of it all at once. It is a relational activity with contingent elements and a fluid dynamic tension. This tension may arrive through a felt sense of the dynamic stillness. The more experienced one is with this rope practice, the quicker one can achieve an engaged relational tension, one that flows between the movement of the performers and the rope.

Beginning

I now return to a discussion of how this peculiar rope work begins. The first step is to lay the rope out on the ground between the two performers: the performers are kneeling on opposite ends of the rope, preparing to lift it up to their heart level. I place special importance on the moment just before lifting, for it is then that one must find the dynamic stillness. In lifting the rope, there is no direct verbal or corporeal cue made by or given to the performers. They are not directing each other in any way but are attuning to the shared, activity through felt sense. A relational dynamic is forming between the two performers and the rope, and as the practice continues, their felt attunement to this relational dynamic increases. Since the materiality of the rope is being utilized in an unconventionally situated manner – and performers are attending to all elements in the surrounding environment – this forms an activity that will develop its own rhythm. The rhythm occurs in what one can think of as cycles. When in dynamic stillness, the practice is deeply embedded in the bodily sensing of these cycles. Perceiving these cycles then becomes felt expressions of the shared activity and attunement with oneself, with the other performer, and as well as with the material of the rope. When experiencing the weight and demand of the rope in an effort to lift it from the ground, there is an invitation and a vague cue to lift the rope. There is an intention to lift the rope upon the perception of this vague cue, but it can not be planned. This is the beginning of a rhythm and cycle between the rope and the performers. The cue may feel vague and a performer may not act on it in time. If so, it is necessary to wait for the next invitation or rising of potency to lift the rope.

The next step is challenging: the performer may have the impulse to consciously lift the rope rather than wait for the reactivated cue arising from the not-known materiality of the rope. One must return to dynamic stillness, allowing a full deactivation of this cycle, which then enables another cycle. At this phase, it is difficult to wait because the body is full of anticipation and excitement at the prospect of lifting the rope and moving up with the potency that was just felt, but missed. This dynamic can feel like a moment of chaos, as if just missing a train. By waiting for the next reactivation, the scenario can create a tension, generating an affective reach toward each other, the rope, and the audience. At this step the performers’ work involves making the effort to drop back into the body and into the deactivation process. They must reorient back to the entanglement with the other performer and the dynamic tension of the rope. These inevitable moments of missed cues, leading to deactivation, leading to reactivation, are like rhythmic cycles of waves. And like waves, they are built from activation thresholds and deactivation thresholds that the performers, if sensitized and immersed in a bodily knowing and felt sense, will detect. As the performers attune to the activity and feel the rope in their hands, there is at once a reaching and receiving guided by felt sense. The intention to work with felt sense here is a willingness to engage with one’s “pre-conceptual nature,” and to let the rhythmicity of this reaching and receiving wash through the body, and become a bodily knowing that can be followed (Rome, 2014, 41).3 Following requires intention, concentration and an openness to the unknown of the current situation as it is constantly changing

Stillness in the Middle of the Rope

An important additional feature of the peculiar task that is this practice is the emergent contingency of the particular intentions that hover between the center of the rope and the performers. In the practice, the task is to allow stillness to emerge in the center of the rope, which I call a fulcrum. A fulcrum, as Franklyn Sills puts it “is essentially a place of stillness – a place, location, site of condensed potency, around which movement, things and happenings are organizing.” (Sills, 2008, 15). The fulcrum organizes the relational movement between the rope and participants. This task, which we can now think of as a score, establishes an agreement that the performers commit to and the fulcrum that emerges is particular to the material, environment, and the participants’ attunement to these elements. The performers find this fulcrum and attunement by “bringing a particular quality of attention to a particular zone of bodily experience” that is, by working with felt sense. (Rome, 2014, 54) The fulcrum found, in this case, is the stillness achieved by the performers in the middle of the rope. This stillness may only occur at brief moments in the rope, but, nonetheless, it is the organizing activity of the practice of holding. The fulcrum carries potency and serves as “portals that connect all the dots between separation [..] Because stillness is the core of every activity, it is the constant uniting principle through which each part connects with other parts...” (Ridley, 2006, 23–24).

As the performers stay committed to the task of the rope practice, change occurs through the interplay of the intentional activity and contingent elements. This change may organize around the fulcrum. Yet the fulcrum is not fixed, nor isolated. It is dynamic and emerges out of the activity. Paradoxically, the task is to work with the fulcrum, but the fulcrum can only emerge when you commit to the task. Working with the fulcrum, all participants and materials are affected in a way that allows for change not induced by one single element of this entanglement, but change that is spurred by the vigorous attunement to the activity and its elements. By committing to the task, the performers open themselves to change happening through experiencing dynamic stillness.

Conclusion

By working with felt sense to engage with the rope in Vielfalt, the performers bring about effects (among which are also affects) within movement that lie at the core of how artistic expression can induce change. The novel, rope- based activity affords new possibilities for action, organization, and relational dynamics, and the rope becomes a way for performers to experience a bodily knowing of the not-known material. Felt sense is a way performers can open themselves to and articulate the different ways that the embodiment of change occurs. This allows them to experience the waves and cycles, to experience the stillness at the center of the rope which is the fulcrum, and to experience and embrace those moments of facing the unknown without resisting or fearing them, but rather moving into “Aha!” moments. In facing creative challenges and changes that may occur by relating to the rope, performers engage with the not-known, and a situated relational entanglement. This generates affect and new trajectories of performance and movement. In cultivating a bodily attunement or felt sense, one can form a collaborative openness with the body to move and be moved by the materials and environment.4

References

Fischer Lichte, E. (2014). Theater and Performance Studies. New York, NY. Routledge. Gendlin, E. T. (1978, 1982, 2003). Focusing. New York, NY: Random House Inc.

Hunter, L. (2016). Sentient Performativities of Embodiment: Thinking alongside the Human. Maryland. Lexington Books.

Hunter, L. (2016). Ethics, performativity and gender: porous and expansive concepts of selving in the performance work if Gretchen Jude and of Nicole Peisl. Palgrave Communications, 2. Article number: 16006 retrieved from. https://www.nature.com/articles/palcomms20166

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3). 575–99.

Levine, P.A. and Phillips, M. (2012). Freedom from pain: discover your body’s power to overcome physical pain. Boulder, CO: Sounds True, Inc.

Noë, A. (2004). Action in Perception. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Noë, A. (2012). Varieties of Presence. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Ridley, C. (2006). Stillness: Biodynamic Cranial Practice and Consciousness. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Rome, D. I. (2014). Your body knows the answer: using your felt sense to solve problems, effect, change, and liberate creativity. Boston, MA, Mass.: Shambhala Publications.

Sills, F. (2008). Das Craniosacrale System. Energetische Anatomie. Textbook, excerpt of a lecture by Franklyn Sills. Milne Institute.

Sutherland, W. (1990). Teachings in the Science of Osteopathy. Anne L. Wales, ed. Fort Worth, Tx: Sutherland Cranial Teaching Founda- tion. Rudra Press.