DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487638.18629Publicado:

01-10-2021Número:

Vol. 25 Núm. 70 (2021): Octubre - DiciembreSección:

InvestigaciónA Framework for the Resilience of LV Electrical Networks with Photovoltaic Power Injection

Marco de referencia para la resiliencia de las redes eléctricas de BT con inyección de potencia fotovoltaica

Palabras clave:

distribution networks, low voltage, photovoltaic systems, performance, impacts (en).Palabras clave:

redes de distribución, baja tensión, sistemas fotovoltaicos, rendimiento, resilencia, impactos (es).Descargas

Referencias

Afgan, N. H. (2010). Sustainable resilience of energy systems. Nova Science Publishers.

Aleem, S. A., Hussain, S. M. S., & Ustun, T. S. (2020). A review of strategies to increase PV penetration level in smart grids. Energies, 13(3), 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13030636 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/en13030636

Ates, Y., Uzunoglu, M., Karakas, A., Boynuegri, A. R., Nadar, A., & Dag, B. (2016). Implementation of adaptive relay coordination in distribution systems including distributed generation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112(Part 4), 2697-2705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.066 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.066

Bajaj, M., Singh, A. K., Alowaidi, M., Sharma, N. K., Sharma, S. K., & Mishra, S. (2020). Power quality assessment of distorted distribution networks incorporating renewable distributed generation systems based on the analytic hierarchy process. IEEE Access, 8, 145713-145737. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3014288 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3014288

Baroud, H., & Barker, K. (2018). A Bayesian Kernel approach to modeling resilience-based network component importance. Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 170, 10-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2017.09.022 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2017.09.022

Bie, Z., Lin, Y., Li, G., & Li, F. (2017). Battling the extreme: A study on the power system resilience. Proceedings of the IEEE, 105(7), 1253-1266. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2017.2679040 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2017.2679040

Blaabjerg, F., Yang, Y., Yang, D., & Wang, X. (2017). Distributed power-generation systems and protection. Proceedings of the IEEE, 105(7), 1311-1331. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2017.2696878 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2017.2696878

Borghei, M., & Ghassemi, M. (2021). Optimal planning of microgrids for resilient distribution networks. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, 128, 106682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2020.106682 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2020.106682

Brinkel, N. B., Gerritsma, M. K., AlSkaif, T. A., Lampropoulos, I. I., van Voorden, A. M., Fidder, H. A., & van Sark, W. G. (2020). Impact of rapid PV fluctuations on power quality in the low-voltage grid and mitigation strategies using electric vehicles. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, 118, 105741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2019.105741 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2019.105741

Cadini, F., Agliardi, G. L., & Zio, E. (2017). A modeling and simulation framework for the reliability/availability assessment of a power transmission grid subject to cascading failures under extreme weather conditions. Applied Energy, 185(Part 1), 267-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.10.086 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.10.086

Chong, W., Yunhe, H., Feng, Q., Shunbo, L., & Kai, L. (2017). Resilience enhancement with sequentially proactive operation strategies. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 32(4), 2847-2857. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2016.2622858 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2016.2622858

Correa F., C. A., Marulanda G., G. A., & Panesso H., A. F. (2016). Impacto de la penetración de la energía solar fotovoltaica en sistemas de distribución: estudio bajo supuestos del contexto colombiano. Tecnura, 20(50), 85-95. https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.tecnura.2016.4.a06

Deboever, J., Grijalva, S., Reno, M. J., & Broderick, R. J. (2018). Fast quasi-static time-series (qsts) for yearlong PV impact studies using vector quantization. Solar Energy, 159, 538-547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2017.11.013 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2017.11.013

Emmanuel, M., & Rayudu, R. (2017). The impact of single-phase grid-connected distributed photovoltaic systems on the distribution network using p-q and p-v models. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, 91, 20-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2017.03.001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2017.03.001

Espinoza, S., Panteli, M., Mancarella, P., & Rudnick, H. (2016). Multi-phase assessment and adaptation of power systems resilience to natural hazards. Electric Power Systems Research, 136, 352-361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2016.03.019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2016.03.019

Gandhi, O., Kumar, D. S., Rodríguez-Gallegos, C. D., & Srinivasan, D. (2020). Review of power system impacts at high PV penetration part I: Factors limiting PV penetration. Solar Energy, 210, 181-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.06.097 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.06.097

Giral, W., Celedón, H., Galvis, E., & Zona, A. (2017). Redes inteligentes en el sistema eléctrico colombiano: revisión de tema. Tecnura, 21(53), 119-137, https://doi.org/10.14483/22487638.12396 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487638.12396

Haixiang, G., Ying, C., SHengwei, M., SHaowei, H., & Yin, X. (2017). Resilience-oriented pre-hurricane resource allocation in distribution systems considering electric buses. Proceedings of IEEE, 105(7), 1214-1233. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2017.2666548 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2017.2666548

Haque, M. M., & Wolfs, P. (2016). A review of high PV penetrations in LV distribution networks: Present status, impacts and mitigation measures. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 62, 1195-1208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.04.025 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.04.025

IEEE (2020). IEEE standard for interconnection and interoperability of distributed energy resources with associated electric power systems interfaces (IEEE 1547a-2020). IEEE. https://standards.ieee.org/standard/1547a-2020.html

Liu, X., Shahidehpour, M., Li, Z., Liu, X., Cao, Y., & Bie, Z. (2017). Microgrids for enhancing the power grid resilience in extreme conditions. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 8(3), 1340-1349. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2016.2626791 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2016.2626791

Montoya., O. D. Gil-González., W. Grisales-Noreña., L. F., Ramírez-Vanegas., L.A., & Molina-Cabrera., A. (2020). Hybrid Optimization Strategy for Optimal Location and Sizing of DG in Distribution Networks. Tecnura, 24(66), 47-61. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487638.16606 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487638.16606

Mousavizadeh, S., Bolandi, T. G., Haghifam, M. R., Moghimi, M., & Lu, J. (2020). Resiliency analysis of electric distribution networks: A new approach based on modularity concept. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, 117, 105669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2019.105669 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2019.105669

Ouyang, M., & Dueñas-Osorio, L. (2014). Multi-dimensional hurricane resilience assessment of electric power systems. Structural Safety, 48, 15-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.strusafe.2014.01.001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strusafe.2014.01.001

Paliwal, P., Patidar, N. P., & Nema, R. K. (2014). Planning of grid integrated distributed generators: A review of technology, objectives, and techniques. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 40, 557-570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.200 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.200

Parrado-Duque, A. (2020). Propuesta de un esquema de evaluación de la resiliencia eléctrica de redes de baja tensión con integración de generación fotovoltaica–condición de operación en estado estable (Classification Number MV38933). [Master's Thesis, Universidad Industrial de Santander]. http://tangara.uis.edu.co/biblioweb/pags/cat/popup/pa_detalle_matbib_N.jsp?parametros=189444|%20|5|6

Parrado-Duque, A., Osma-Pinto, G., Rodríguez-Velásquez, R., & Ordóñez-Plata, G. (2019, December 4-6). Considerations for the assessment resilience in low voltage electrical network with photovoltaic systems – part I [Conference presentation]. 2019 FISE-IEEE/CIGRE Conference - Living the energy Transition (FISE/CIGRE), Medellín, Colombia. https://doi.org/10.1109/FISECIGRE48012.2019.8984962 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/FISECIGRE48012.2019.8984962

Rahimi, K., & Davoudi, M. (2018). Electric vehicles for improving resilience of distribution systems. Sustainable Cities and Society, 36, 246-256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2017.10.006 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2017.10.006

Rocchetta, R., Zio, E., & Patelli, E. (2018). A power-flow emulator approach for resilience assessment of repairable power grids subject to weather-induced failures and data deficiency. Applied Energy, 210, 339-350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.10.126 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.10.126

Shang, D. R. (2017). Pricing of emergency dynamic microgrid power service for distribution resilience enhancement. Energy Policy, 111, 321-335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.09.043 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.09.043

Shanshan, M., Liu, S., Zhaoyu, W., Feng, Q., & Ge, G. (2018). Resilience enhancement of distribution grids against extreme weather events. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 33(5), 4842-4853. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2018.2822295 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2018.2822295

Shivashankar, S., Mekhilef, S., Mokhlis, H., & Karimi, M. (2016). Mitigating methods of power fluctuation of photovoltaic (PV) sources - a review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 59, 1170-1184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.01.059 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.01.059

Tedoldi, S. S., Jacob, S. B., Vignerte, J., Strack, J. L., Murcia, G. J., & Garín, J. C. B. E. (2017, November 12-15). Impacto de la generación distribuida con energía solar fotovoltaica en la tensión eléctrica – simulación de un caso [Conference presentation]. XII Latin-American Congress on Electricity Generation and transmission (CLAGTEE 2017), Mar del Plata, Argentina. http://www3.fi.mdp.edu.ar/clagtee/2017/articles/21-014.pdf

Téllez-Santamaría, N. E. (2020). Descripción del consumo energético del edificio de ingeniería eléctrica a partir de la monitorización de los tableros de baja tensión. (Classification Number E 38161). [Undergraduate thesis, Universidad Industrial de Santander]. http://tangara.uis.edu.co/biblioweb/pags/cat/popup/pa_detalle_matbib_N.jsp?parametros=188647|%20|9|61

Tonkoski, R., Turcotte, D., & El-Fouly, T. H. (2012). Impact of high PV penetration on voltage profiles in residential neighborhoods. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 3(3), 518-527. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSTE.2012.2191425 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/TSTE.2012.2191425

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Recibido: 2 de agosto de 2021; Aceptado: 12 de agosto de 2021

ABSTRACT

Context:

Electrical distribution networks have undergone several changes in the last decade. Some of these changes include incorporating distributed energy sources such as solar photovoltaic (PV) generation systems. This could modify the performance of electrical networks and lead to new challenges such as evaluating the impacts of the PV integration, the response to electrical and climatic disturbances, and the planning and restructuring of networks. Electrical network behavior with respect to PV integration could be evaluated by quantifying the variation in operation and including network resilience.

Objective:

To propose a reference framework to evaluate the resilience of LV electrical networks with PV power injection.

Methodology:

This paper addresses the framework for evaluating the performance of a low-voltage (LV) electrical network in the face of the integration of PV systems. It collects research related to evaluating the resilience of electrical networks on severe climate changes, natural disasters, and typical maneuvers, and then, it proposes a guideline to evaluate the performance of LV electrical networks with the integration of PV generation sources while including resilience. To this effect, the determination of resilience evaluation indices is proposed. These indices are obtained from a normalized transformation of the networks’ measurable electrical parameters that are the most affected by PV integration or are significant in the performance of the networks. Finally, the evaluation of a proposed resilience index for a university building’s LV network is presented as a case study.

Results:

The resilience assessment proposal is applied to a case study. When evaluating the resilience of the voltage at the common coupling point of the PV, an index of 0,84 is obtained, which is equivalent to 59,8 hours of overvoltage.

Conclusions:

It is possible to improve the resilience of the BT-LV network through management strategies. In the case study, a 29% reduction in overvoltage hours was obtained by applying a curtailment strategy to the PV system.

Financing:

ECOS-Nord, Minciencias, and Universidad Industrial de Santander.

Keywords:

distribution networks, low voltage, photovoltaic systems, performance, resilience, impacts.RESUMEN

Contexto:

Las redes eléctricas de distribución han sufrido varios cambios en la última década. Algunos cambios incluyen la incorporación de fuentes de energía distribuidas como los sistemas de generación solar fotovoltaica (PV). Esto podría modificar el rendimiento de la red eléctrica y generar nuevos desafíos como la evaluación de los impactos de la integración fotovoltaica, la respuesta a las perturbaciones eléctricas y climáticas y la planificación y reestructuración de las redes. El comportamiento de la red eléctrica frente a la integración fotovoltaica podría evaluarse cuantificando la variación en la operación e incluyendo la resiliencia de la red.

Objetivo:

Proponer un marco de referencia para la evaluación de la resiliencia de las redes eléctricas de BT con inyección de potencia PV.

Metodología:

Este artículo aborda el marco para evaluar el desempeño de una red eléctrica de baja tensión (BT) frente a la integración de sistemas PV. Recoge investigaciones relacionadas con la evaluación de la resiliencia de las redes eléctricas ante cambios climáticos severos, desastres naturales y maniobras típicas, y luego propone una guía para evaluar el desempeño de las redes eléctricas de baja tensión con la integración de las fuentes de generación fotovoltaica e incluye la resiliencia. Para ello, se propone la determinación de índices de evaluación de resiliencia, los cuales se obtienen de una transformación normalizada de los parámetros eléctricos medibles de las redes que son más afectados por la integración fotovoltaica o son significativos en el rendimiento de las redes. Finalmente se presenta la evaluación de un índice de resiliencia propuesto para una red LV de BT de un edificio universitario como caso de estudio.

Resultados:

La propuesta de evaluación de resiliencia se aplica a un caso de estudio. Al evaluar la resiliencia de la tensión en el punto de acoplamiento común del PV, se obtiene un índice de 0,84, equivalente a 59,8 horas de sobretensión.

Conclusiones:

Es posible mejorar la resiliencia de la red de BT mediante estrategias de gestión. En el caso de estudio, se obtuvo una reducción del 29% de las horas con sobretensión aplicando una estrategia de reducción al sistema PV.

Financiamiento:

ECOS-Nord, Minciencias y la Universidad Industrial de Santander.

Palabras clave:

redes de distribución, baja tensión, sistemas fotovoltaicos, rendimiento, resiliencia, impactos.INTRODUCTION

Electrical networks transport electrical energy from generation points to consumption points. Therefore, their design must guarantee the quality conditions for the operation of the electrical system and loads. These conditions are generally voltage regulation, energy losses, chargeability, power balance, and harmonic distortion (Deboever et al., 2018; Haque & Wolfs, 2016).

An electrical network design guarantees the operation within a functional and regulatory range under normal and non-normal operation conditions. The latter may include equipment or line disconnections, atmospheric discharges, or short circuit failures (Bajaj et al., 2020). Additionally, severe weather conditions, malicious damage caused by humans, natural disasters, non-linear loads, equipment maneuvers, and equipment in poor condition produce non-normal operating conditions.

Likewise, distributed generation (DG) systems could modify the operation of the network, which sometimes leads to violations of the operating conditions (Bajaj et al., 2020; Cadini et al., 2017; Correa-Flórez et al., 2016). However, the impact on the electrical network due to variations in operating conditions, unexpected events, and permanent modifications could be characterized by evaluating system resilience (Borghei & Ghassemi, 2021; Mousavizadeh et al., 2020).

There is no proper or unified concept to define resilience applied to low voltage (LV) electrical networks. Nevertheless, the resilience of an electrical system is conceived to a greater extent as the capacity of the network to withstand an adverse event without losing operating conditions, reducing the impact on the service quality to users, recovering after the event, and adapting to new operating conditions (Borghei & Ghassemi, 2021).

The concept of resilience in electrical systems emerged in the last decade (Cadini et al., 2017; Mousavizadeh et al., 2020), and lots of research are oriented to quantification in different scenarios. Resilience can be measured based on reliability, robustness, adaptability, and recoverability indices (Rocchetta et al., 2018). All cases evaluate the level of impact of an adverse event on the electrical network.

In addition, the integration of photovoltaic (PV) systems in residential and commercial LV networks has increased in the last decade (Aleem et al., 2020; Gandhi et al., 2020). Thus, there is a need to carry out studies focused, for instance, on the performance of the networks in the face of variations of the injected power due to fluctuations in solar irradiance and the characterization of the resilience of LV networks (Brinkel et al., 2020). This could favor the networks’ capacity to withstand adverse conditions. Moreover, it will allow operators to establish complementary operating conditions of existing networks and define strategic plans to respond to PV integration in the medium and long term.

This paper is organized as follows: the concept sections present a review of the PV systems’ significant impacts in LV and describe the concept of resilience in electrical networks along with the typical scenarios for evaluation. Then, the discussion section proposes how the concept of resilience could be applied to evaluate the performance of LV networks that integrate PV. The results section presents a case study to apply the discussion, and the final section presents the conclusions of this research.

IMPACTS OF THE INTEGRATION OF PV SYSTEMS ON LV DISTRIBUTION NETWORKS

The impacts of the integration of PVs in LV networks depend on the network architecture, the PV penetration, and the meteorological conditions (Haque & Wolfs, 2016). According to the architecture, the impacts are related to the impedances of the lines, the voltage regulation equipment, the protections, and the system’s response times.

Typically, an increase in PV penetration implies an increase in impact levels. As for the meteorological conditions, the impacts of the PV system depend on the average, maximum, and minimum values of solar irradiation and ambient temperature, as well as on sporadic variations (Deboever et al., 2018; Giral-Ramírez et al., 2017).

Moreover, PV systems could favor the electrical network’s reliability, load availability, and voltage regulation; relieve power congestion; and reduce losses and operation and billing costs. For example, Shanshan et al. (2018) study the implementation of DG as a strategy to mitigate disconnection events.

However, PVs could also alter the voltage waveform, produce voltage and power unbalances, generate reverse power flows, and cause premature deterioration in regulation, control, and protection equipment (Shanshan et al., 2018). Some significant impacts of PV systems on distribution networks are described below.

Impacts on the voltage profile

PV systems in LV could help keep the service voltage within acceptable limits (Aleem et al., 2020). This is possible because the strategic location of the PV systems reduces currents in certain sections of the network, which improves voltage regulation and reduces losses (Montoya et al., 2020). However, the unplanned and massive integration of PVs could cause overvoltage or low voltage (Deboever et al., 2018; Haque & Wolfs, 2016).

Depending on the sitting of the PV system, a higher PV penetration can be achieved without violating the voltage limits. For example, some simulations have shown that a strategic sitting can achieve a penetration of 50% of the feeder without violating the limits of voltage regulation (Tedoldi et al., 2017).

Impacts on power and voltage balance

Non-linear power inverters could lead to injecting distorted currents and unevenly delivering power to the phases of the system (Borghei & Ghassemi, 2021). In addition, distribution networks typically operate with unbalanced voltages, which is a product of unbalanced load in the commercial and residential sectors. Thus, an unbalanced power injection of PV systems could lead to an unbalance in the service voltage (Emmanuel & Rayudu, 2017).

Impacts on the coordination of protections

In LV networks, the protection farthest from the supply bus must act first to isolate the section affected by a failure. The other protections act in sequence as a backup if the primary one does not do it.

Based on Ates et al. (2016) and Paliwal et al. (2014), this can indicate that the conventional LV protection schemes are vulnerable to PV integration. Moreover, three main technical aspects could cause malfunctions in the coordination of protections:

-

The PV systems integration could cause bidirectional power flows in the network, which means that the coordination of protections based on a unidirectional way is ineffective.

-

The network could present high variations in the current magnitude when connection and disconnection events occur or the power injected by the PV varies.

-

The short-circuit current tends to increase with PV integration

RESILIENCE IN ELECTRICAL NETWORKS

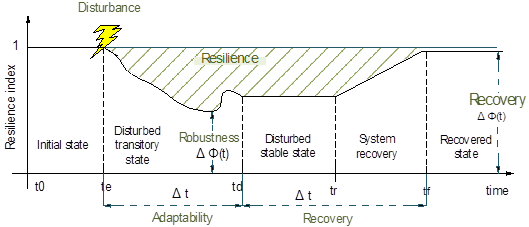

Electrical network resilience could be defined as the ability to withstand an adverse event without losing operating conditions and recover after the event (Afgan, 2010; Borghei & Ghassemi, 2021). A resilient electrical network simultaneously evaluates the behavior of the systems that face an event and the consequences (Baroudand Barker, 2018).

The behavior of the network can be represented by a parameter, Φ(𝑡) , generally called sustainability (Afgan, 2010). The probability that the network will operate in its normal mode is called reliability. When a disturbance, e(𝑡), occurs, Φ(𝑡) decays according to the vulnerability to e(𝑡). The network’s ability to withstand perturbations, e(𝑡), is called robustness (Baroud & Barker, 2018).

Once e(𝑡) has finished, the network experiences a transient state until it seeks a stable one. After a time, t r , restoration starts until a stable normal operating mode, Φ(𝑡r), is reached. The final operation state, Φ(𝑡f), could be different from the initial Φ(𝑡0). This depends on the disturbance level and recovery of the network. The network’s capacity to reach normal operating conditions is called recoverability (Baroud & Barker, 2018).

The literature shows mostly studies on the resilience of electrical networks to extreme weather events. However, these have a low probability of occurrence and high impacts (Haixiang et al., 2017; Ouyang & Dueñas-Osorio, 2014), compared to events directly or indirectly caused by humans (Liu et al., 2017; Shanshan et al., 2018).

There are few studies related to the resilience of electrical networks to permanent modifications, such as Deboever et al. (2018) and Blaabjerg et al. (2017). These modifications have a low impact but could cause a sudden change of network components and strengthen or weaken the response to a temporary disturbance. They could integrate new elements as generation sources, voltage regulation equipment, or distribution lines, and they could also imply modifications of distribution transformers, the connection point of a load, or an increase in the nominal power of a generation source. Table 1 summarizes the analysis scenarios and the resilience evaluation indicators for the distribution networks according to the literature.

Source: Authors

Table 1: Studies on the evaluation of resilience in electrical networks

Scenario

Indicator

Description

Several weather conditions

Generation cost (Shang, 2017)

It uses a dynamic isolated microgrid for supply during power outages

Vulnerability, redundancy, and adaptability (Espinoza et al., 2016)

It evaluates the adaptation of power systems to frequent natural disasters

Hurricanes

Risk probability and robustness (Ouyang & Dueñas-Osorio, 2014)

It analyzes power systems with high probability of hurricanes

Natural disasters and human attacks

Supply capacity and restoration time (Bie et al., 2017)

It analyzes the infrastructure of power systems and the measures taken around the world

Reliability, island mode (Haixiang et al., 2017; Rahimi & Davoudi, 2018)

They analyze the capacity of DG sources such as electric vehicles and microgrids to improve the resilience of a residential electrical network

Natural disasters in cascade

Reliability and supply capacity (Cadini et al., 2017)

It analyzes the capacity of a transmission network to maintain service in case of climatic disasters

Extreme weather events

Operation cost and power supply capacity (Chong et al., 2017)

It proposes an operation strategy to improve the resilience of power systems

DISCUSSION

This section integrates the bibliographic review. It proposes preliminary guidelines for evaluating the performance of an LV network through resilience. It considers PV power injection as a disturbance facing the electrical network.

There is currently little research on the resilience of electrical networks before DG integration. However, some studies are related to the use of smart grids and microgrids as a strategy to improve the response of networks to extreme events (Liu et al., 2017; Shanshan et al., 2018).

Likewise, the integration of complementary components such as hybrid electric vehicles as generation and storage systems could supply the critical loads during a natural disaster or power outages (Rahimi & Davoudi, 2018; Shanshan et al., 2018).

On the other hand, it is usual to evaluate the maximum DG power that could be installed at a node in the network without compromising the operating conditions. Generally, the IEEE 1547 standard (2020) is taken as a reference for operating conditions. The maximum power capacity is called Hosting Capacity (Shivashankar et al., 2016). It is a way to assess the electrical network’s resilience, and it ensures that the networks do not lose operating conditions due to the integration of the DG.

Although the consulted literature does not consider evaluating LV networks’ resilience directly, it is possible to approach it from indexes that relate the impacts of a disturbance or modification in the network with its response. The evaluation indices are obtained from the normalization of the operating parameters affected before the disturbances and evaluation scenarios, particularly in the face of climatic and operational disturbances.

Each resilience evaluation index must be related to an operation parameter. The operating parameters are those established by the IEEE 1547 standard (2020) for DG interconnection and others determined from the review of related literature. The evolution over time of each evaluation index in the face of a disturbance is called sustainability (Afgan, 2010).

The resilience of each operation parameter can be determined from the integration of sustainability, and the total resilience of the network from a weighted parameter sum.

PV integration could be considered favorable if the evaluation indexes are kept close to 100% and are higher than in a reference scenario, which could be the same network without PV generation or a network at a standardized level for this test.

The electrical network’s operation can be quantified through a sustainability function, Φi(𝑡), by an evaluation index. Before a regular operation of the system, the index must remain constant and close to 100%. A disturbance, e(𝑡), can produce a variation and a transitory state of Φi(𝑡).

It is possible to quantify the resilience of each parameter (Ri) from this variation and the transitory state, which would be the area between ideal sustainability (Φi(𝑡) =1) and its evolution before the disturbance. This strategy simultaneously evaluates the definitions of robustness, adaptability, and recoverability, and it includes operation variations and response times. Figure 1 represents the evolution of a resilience evaluation index in the face of a disturbance.

Figure 1: Evolution of a resilience index in the face of a disturbance

The assessment of the resilience evaluation indexes can be studied in typical scenarios of distribution system disruption with PV systems. In addition, the evaluations can be made from simulations of the behavior of the PV system and the characteristics of the electrical network.

The evaluation scenarios must include system-specific disturbances such as voltage gaps, voltage peaks, frequency variations, and voltage unbalances. They must also consider external disturbances such as climatic variations (solar irradiation and temperature) and faults (disconnections and short circuits).

CASE STUDY

A case study is examined to apply what was exposed in the discussion section. An evaluation of the voltage regulation index is applied to estimate a resilience index at the point of common coupling (PCC). The setting of this case study is Universidad Industrial de Santander.

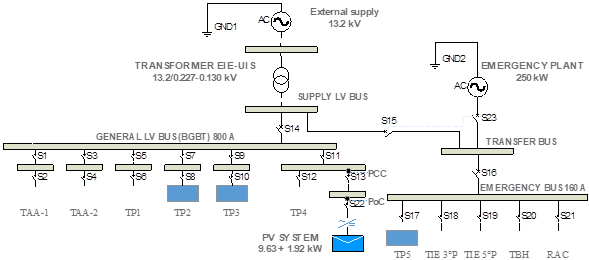

The electrical network of the building is appropriate for this study since it has smart meters in the primary nodes of the network. It also has an interconnected PV system through microinverters (one for each panel). Figure 2 presents the electrical connection diagram of the Electrical Engineering Building (EEB). More detailed information of the EEB can be consulted in the research by Parrado-Duque (2020) and Téllez-Santamaría (2020).

The considerations of the case study are presented below:

Figure 2: Electrical connection diagram of EEB, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Colombia

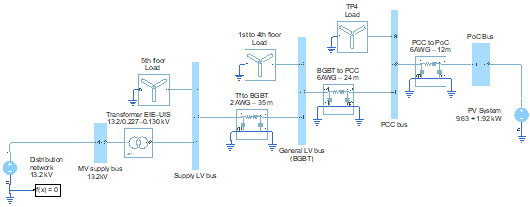

Electrical network model

For the sake of simplicity, the electrical network is modeled as a single-phase equivalent. Loads are modeled as constant power, and wire conductors are modeled as constant impedance. The power output delivered by the PV system is calculated according to MPPT and the irradiance and temperature. Figure 3 presents the diagram of the single-phase equivalent Simulink model of the EEB’s network.

Figure 3: Simulink model of the EEB for testing

Power profiles for test

The test uses actual electrical measurements from the EEB. The electrical variables used are the voltage in the primary supply bar and the active and reactive power in the bars of each floor. The PV system uses the temperature and solar irradiance information obtained from the weather station installed on the terrace of the building.

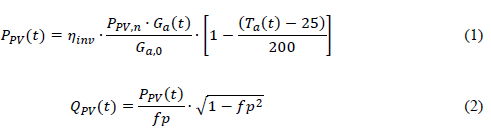

A period with disconnection events due to high PV generation while a low load is selected for the test. The sampling period is one month (from October 17th to November 16th, 2019), with a time step of ten minutes. The maximum power generated by the PV system is calculated using Equations (1) and (2).

where 𝑃𝑃𝑉,𝑛 is the PV system peak power [kWp], 𝐺𝑎,0 is the standard condition irradiance [W/m2], 𝐺𝑎(𝑡) is the current solar irradiance in [W/m2], 𝑇𝑎(𝑡) is the current ambient temperature in °C, 𝜂𝑖𝑛𝑣 is the inverter efficiency 𝑃𝑃𝑉(𝑡) is the PV system active power at 𝑡 [kW], 𝑓𝑝 is the operating power factor, and 𝑄𝑃𝑉(𝑡) is the PV system reactive power at 𝑡 [kvars].

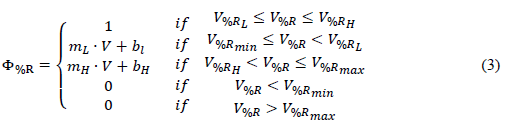

Evaluation of the voltage regulation index

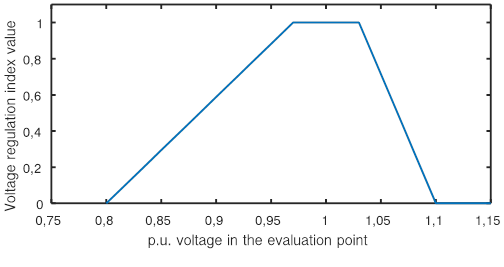

Equation (3) is proposed to evaluate the voltage regulation index every day. Finally, the results are averaged for the test period. The parameters of (3) are tuned according to the case study (Parrado-Duque et al. (2019) expand this discussion). Figure 4 presents the transformation graphically.

Figure 4: Voltage regulation index transformation

Here, 𝑉%𝑅𝐿 and 𝑉%𝑅𝐻 are the voltage regulation limits; 𝑉%𝑅𝑚𝑖𝑛 and 𝑉%𝑅𝑚𝑎𝑥 are the voltage regulation limits allowed for the electrical network; 𝑚𝐿 and 𝑚𝐻 are the slopes, which are determined according to the regulation limits; and 𝑏𝐿 and 𝑏𝐻 are the corresponding cut points. In the case study, an acceptable voltage value between 0,97 p.u. and 1,03 p.u. is Φ%R=1, and an unacceptable voltage of less than 0,8 p.u. and greater than 1,1 p.u. corresponds to Φ%R=0.

PV power curtailment

According to Tonkoski et al. (2012), curtailment is applied to the power PV generated to reduce the overvoltage in the PCC produced by the injection of PV power. The curtailment strategy is given by Equation (4).

Here, PPV(𝑡) is the maximum power that the PV system can deliver at time t, and it is given by Equation (4); and 𝜂𝐶𝑢𝑡 is the curtailment index that varies between 0 and 1. It is obtained from the PCC voltage. In the case there is no overvoltage in the PCC 𝜂𝐶𝑢𝑡 =1, if there is overvoltage, 𝜂𝐶𝑢𝑡 decreases until a proper voltage regulation is reached or until 𝜂𝐶𝑢𝑡=0.

Results and analysis

The results were obtained in MATLAB through a quasi-static power flow in Simulink. The voltage regulation index was evaluated without the curtailment strategy and then by applying it.

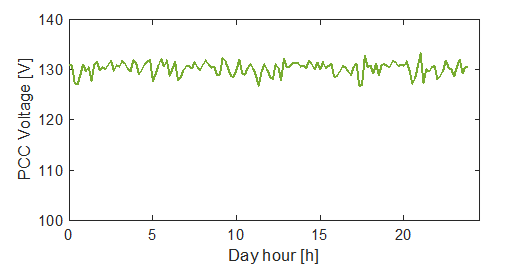

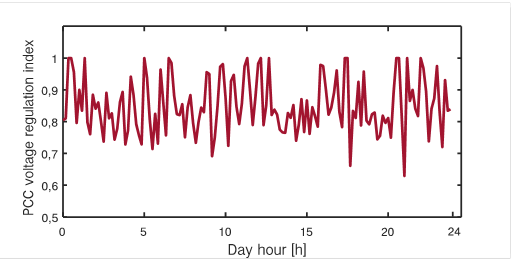

Figures 5 and 6 present the voltage profile for a day without the curtailment strategy and the voltage regulation index using the transformation described in Figure 4. The voltage regulation index was evaluated for each time step.

Figure 5: PCC voltage for day 1 (October 17th, 2019)

Figure 6: PCC voltage regulation index for day 1

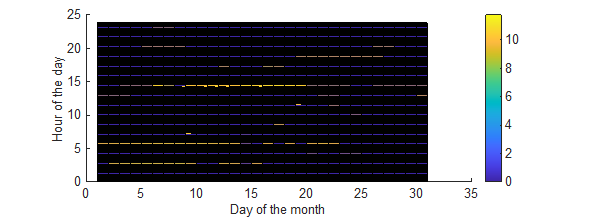

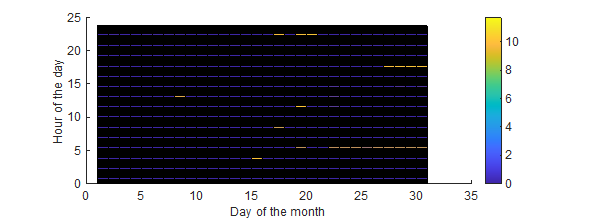

Figures 7 and 8 present the voltage for the network at a given time during the month and when applying the curtailment strategy. Note that it considers the working hours between 6:00 and 20:00. Finally, Table 2 presents the summary of the results obtained.

Figure 7: Voltage regulation in the PV system’s PCC during the test month

Figure 8: Voltage regulation in the PV system’s PCC while applying the curtailment strategy

Source: Authors

Table 2: Studies on the evaluation of resilience in electrical networks

Parameter

Non- curtailment

Curtailment

Voltage regulation index

0,84

0,845

Overvoltage total hours

59,8 h

42,0 h

Overvoltage working hours

31,0 h

15,8 h

PV generation

1,6 MWh

1,6 MWh

This case considers overvoltage if the voltage regulation in the PCC is equal to or greater than 10%. Note that the voltage regulation index, 𝛷%𝑅, indicates potential regulation problems, which is consistent with the total overvoltage hours that the PV system presents.

When applying the curtailment strategy, it is possible to slightly increase 𝛷%𝑅. However, a significant decrease is achieved in the total hours with overvoltage, especially in the working hours (it is reduced by 49%). Therefore, the curtailment strategy does not affect the energy delivered by the PV system.

According to the results, applying curtailment strategies to the PV system can improve the level of resilience of the electrical network of the EEB. It is also noticed that the voltage regulation problems are typical of the network and not of the PV system. Therefore, there is an opportunity to improve applied voltage regulation strategies on the supply bar or feeder.

CONCLUSIONS

The resilience of an LV network with PV integration before disturbances has not been evaluated directly in the consulted literature. However, this can be approached from the perspective of the variation of the response in the networks to the impacts and effects that PV systems produce in the face of climatic variations and operation disturbances.

A correct evaluation of resilience must quantitatively define the normalized resilience indices from the operating parameters of the network affected by the PV integration. Parameters have been identified according to the literature and experience in the dissing of distribution networks.

It is recommended to use real operating profiles of the PV system and the network in order to obtain low error results. The case study shows congruence between the value found in the voltage regulation index and the overvoltage in the network. It also shows that the application of power management strategies can improve an electrical network’s resilience level.

Acknowledgements

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the Department of Electrical, Electronics, and Telecommunications Engineering (Escuela de Ingenierías Eléctrica, Electrónica y de Telecomunicaciones), the Vice-Principalship for Research and Extension (Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Extensión) of Universidad Industrial de Santander (projects 2705 and 8593), and the Minister of Science, Technology, and Innovation (Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, MINCIENCIAS) (Project - Contract No. 80740-191-2019 - Funding resource). Moreover, to ECOS-Nord, an internationalization program that has allowed collaborative work between the Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté, the FEMTO-ST Institute, and Universidad Industrial de Santander to enhance collaborative work and the development of science and knowledge.

REFERENCES

FUNDING

This research was funded by ECOS-Nord and MINCIENCIAS.

Licencia

Esta licencia permite a otros remezclar, adaptar y desarrollar su trabajo incluso con fines comerciales, siempre que le den crédito y concedan licencias para sus nuevas creaciones bajo los mismos términos. Esta licencia a menudo se compara con las licencias de software libre y de código abierto “copyleft”. Todos los trabajos nuevos basados en el tuyo tendrán la misma licencia, por lo que cualquier derivado también permitirá el uso comercial. Esta es la licencia utilizada por Wikipedia y se recomienda para materiales que se beneficiarían al incorporar contenido de Wikipedia y proyectos con licencias similares.