DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.94Published:

2010-01-01Issue:

Vol 12, No 1 (2010) January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesShort story student-writers: active roles in writing through the use of e-portfolio dossier

Estudiantes creadores de historias: su papel como escritores a través del portafolio electrónico

Keywords:

habilidad de escribir, enfoque de género y proceso, historias cortas, dossier del portafolio electrónico (es).Keywords:

writing skills, genre and process approach, short stories, e-portfolio dossier (en).Downloads

References

Ali, S.Y. (2005). An introduction to electronic portfolios in the language classroom. Retrieved November 16, 2008 from: http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Ali-Portfolios.html

Badger, R. and G. White. (2000). A process genre approach to teaching writing. ELT Journal. 54 (2), 153-160.

Barrett, H. (2000). Create your own electronic portfolio, Retrieved November 15, 2008 from http://www.electronicportfolios.com/portfolios/iste2k.html

Barrett, H. (2007). Researching electronic portfolios and learner engagement: the reflect initiative. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 50 (6), 436-449.

Bergeron, B., Wermuth, S. & Hammar, R. Initiating portfolios through shared learning: Three perspectives. (1997). The Reading Teacher. 50 (7), 552-562

Brown, D. (1994). Teaching by principles, an interactive approach to language pedagogy. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. (2001). Council of Europe. Europe: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved on November 13, 2009 from http://www. uta.fi/laitokset/kielikeskus/CEF/CEF.htm

Fuentes, G. & Rincón, S. (2008). Improving short story writing through e-portfolios. Project developed in the teacher development program (TDP) at Universidad de La Sabana. Bogotá.

Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. (1967).The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Goodson, T. (2007). The electronic portfolio: shaping an emerging genre. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 50 (6), 432-434.

Hale, B. (n.d.) How to write a story. Retrieved February 25, 2009 from http://www.brucehale.com/howto. htm

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching. Edinburgh Gate, Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Hyland, K. (2002). Teaching and researching writing. Malaysia: Pearson Educated Limited.

LaBonte, Randy et al (2003). Moderating tips for synchronous learning using virtual classroom technologies. Odyssey Learning Systems Inc. Retrieved from http://odysseylearn.com/Resrce/text/e-Moderating%20tips.pdf

Lingzhu, J. (2009). Genre-based approach for teaching English factual writing. HLT Magazine. Retrieved on November 1, 2009 from http://www.hltmag.co.uk/ apr09/mart02.htm

Lucke. M. (1999). Schaum's quick guide to writing great short stories. U.S.A.:McGraw Hill Companies. Retrieved on February 25, 2009 from http://books. google.com.co/books?id=qoYNPolwZ-QC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_v2_summary_r&cad= 0#v=onepage&q=&f=false

McCoy, C. (2002). Creating the perfect setting for writingfiction. Retrieved on June 18, 2009 from http://www.essortment.com/all/writingfiction_rcck.htm

Marshall, C. (1999). Designing qualitative research. London: Sage Publications.

Miles, M. & Huberman, M. (1994).Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2006). Estándares básicos de competencia en lengua extranjera. Formar en lenguas extranjeras. Bogotá.

O'Brien, T. (2004). Writing in a foreign language: Teaching and learning. Language Teaching. 37 (1), 1-28.

Piccardo, E. (2009). Creative computing in EFL. HLT Magazine. Retrieved on November 1st. 2009, from: http://www.hltmag.co.uk/sep03/mart4.htm

Sagor, R. (2000). Guiding school improvement with action research. Alexandria,VA: Association for Supervision and Curricular Development.

Sagor, R. (2005). The action research guidebook. Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Salem, N. (2009). Teaching writing: helping second language writers experience a sense of ownership of their writing. Retrieved on November 2, 2009 from http://www.nadasisland.com/teachingwriting.htm

Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1990) . Basics of qualitative research grounded theory. Procedures and techniques. London: Seige Publications.}

Tangpermpoon, T. (2008). Integrated approaches to improve students writing skills for English major students. Retrieved November 20, 2008 from http://www.journal.au.edu/abac_journal/2008/may08/01(1-9)_article01.pdf

Tribble, C. (1996). Writing. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Webs.com (2009). Website builder. Retrieved January 12, 2009 from http://www.webs.com/

Weigle, S. (2002). Assessing writing. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wright, A. (2009). Making stories with little language. HLT magazine. Retrieved on November 1st, 2009 from http://www.hltmag.co.uk/oct09/less04.htm#C1

Zubizarreta, J. (1994). Teaching portfolios and the beginning teacher. The Phi Delta Kappan.76 (4), 323-326

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2010 vol:12 nro:1 pág:99-115

Research Article

Short story student-writers: active roles in writing through the use of e-portfolio dossier

Estudiantes creadores de historias: su papel como escritores a través del portafolio electrónico

Liliana Cuesta

Lecturer - Researcher Universidad de La Sabana, Chía-Colombia E-mail: lilianamar@yahoo.com

[1]; Stella Rincón

English Teacher School District SED (Secretaría de Educación de Bogotá) E-mail: stellarinconv@hotmail.com

Abstract

This article reports the effects of using the genre-process approach and e-portfolio dossier to improve short story writing among senior year students from a state school in Bogotá. This study originated from a need to generate student interest in the development of writing skills and to find instructional strategies that guide learners through each stage of the process. The results of data analysis from this study reveals significant improvements in students’ written production and the emergence of new roles among the learners: they evolved from a passive to an active status which enabled them to become planners, builders and reviewers of their own short story writing process. These new roles helped students reflect on their learning and become better decision makers and critical thinkers. Results from this study also validate the use of e-portfolio dossiers as an effective learning and assessment tool.

Key words: writing skills, genre and process approach, short stories, e-portfolio dossier.

Resumen

En este artículo se describen los efectos causados por el uso del enfoque de género y proceso y del dossier del portafolio electrónico en el desarrollo de la habilidad para escribir historias cortas de un grupo de estudiantes de undécimo grado de un colegio público en Bogotá. Este estudio nació de la necesidad por despertar el interés de los estudiantes frente al desarrollo de sus habilidades de escritura y por encontrar estrategias instruccionales para guiarlos durante las etapas de este proceso. El análisis de datos revela una mejoría significativa en la producción escrita y evidencia la aparición de nuevos roles por parte de los estudiantes: de un estado pasivo se transformaron en creadores, constructores y evaluadores activos de su proceso de producción escrita de historias cortas. Estos roles les ayudaron a reflexionar sobre su aprendizaje y a mejorar su capacidad para tomar decisiones y desarrollar su pensamiento crítico. Los resultados también validaron el uso que tiene el portafolio electrónico como una herramienta útil en el aprendizaje y la evaluación.

Palabras claves: habilidad de escribir, enfoque de género y proceso, historias cortas, dossier del portafolio electrónico.

Introduction

Learning a foreign language implies the strengthening of strategies that enable effective communication skills in meaningful contexts. Over the years, a debate on the hierachization of language skills has taken place in language education. Many agree that all skills deserve the same importance, whereas others believe that writing should take first place, given its significance in all social, professional, and academic domains. According to Tribble (1996) and Harmer (2007), people use writing for various purposes in different contexts in which individuals are evaluated depending on the control they demonstrate of this ability.

In the last two decades, the teaching of writing has evolved from being focused on a final product (product approach) to a view in which writing is seen as a process embedded in a social situation (process genre approach). Traditionally, in the linear product-oriented method, writing was mainly associated with linguistic knowledge about the appropiate use of language, while writing development was seen as a result of imitating texts provided by the teacher (Badger and White, 2000). Nowadays, however, writing is understood to involve not only knowledge about the structure of language but also knowledge about the context in which writing happens, the purpose of writing, and skills in the use of language. Writing development takes place by developing learners’ potential and by providing feedback to learners’ responses.

Hyland (2002) states that writing is essentially a problem-solving activity that involves a cognitive process, process approach, and a socially oriented proposal, genre approach. Salem (2009) and Tangpermpoon (2008) both observe that writing is a non-linear process since it allows writers to reformulate their ideas as they strive to build meaning. They agree that writing is a cycle of activities that moves learners from the generation of ideas, through revising drafts, and ultimately to the production of a final text that combines both editing and cognitive stages. On the other hand, they also state that writing is mainly a social activity since it is focused on the way writers and texts interact with readers, an aspect that has been associated with genre approach. Badger and White (2000) claim that the genre-based approach enables students to distinguish different writing patterns (such as the ones found in short stories) given the fact that they can identify and manage the characteristics of a particular type of text as a basis to elaborate and communicate their ideas sucessfully. Lingzhu (2009) establishes that mechanical writing activities do not motivate students since they are not engaged in real and communicative writing scenarios in which they have to write for a particular audience in an specific context. He concludes that “genre theory is a theory of language use” since texts differ according to the context in which they are used.

Tribble (1996) states that there is considerable scope for an approach that emphasizes both knowledge about the context and content of a piece of writing (focus on genre) and knowledge of the best way of preparing for a writing task (focus on process). In such a view, a successful writer has to draw on knowledge of the genre (content and context), knowledge of the language system (for example, lexis and syntax) necessary for doing the writing task, and knowledge of the writing process (the steps) for preparing the task. When these sets of knowledge are interrelated, writers are more likely to produce effective texts since they know what to write in a given context, which parts of the language system are the most appropriate for carrying out the task in hand, and they have a command of the necessary writing skills for the task.

O’Brein (2004) states that the process approach is seen as a way to discover meaning and ideas instead of developing grammar exercises. Teachers can encourage learners to travel around their thoughts and develop their own writing throughout the use of the following steps of the five-step writing process:

- Pre-writing prepares the learners to write. Teacher can use different strategies to provide writing tasks. The students could be asked to brainstorm and cluster ideas on a particular topic, then share experiences without paying attention to correctness or appropriateness. They may be shown models of a text and be asked to identify the conventions (language, form, etc.) of the particular text type.

- First draft composing. Learners produce their texts from the ideas generated in the previous stage or by following a model text previously presented and analyzed. The teacher helps and guides learners in their writing style, organization, content and presentation and encourages them to help each other.

- Feedback. Learners receive comments from their teachers or peers. The learners can share or display their finished work and give overall comments on how successful their work has been.

- Second draft writing. Learners revise and produce a new draft based on the teacher and peers´ comments.

- Proofreading. In this final stage, studentswriters are focused on the appropriate use of vocabulary, layout, and grammar.

In the present study, the genre chosen was short stories because these texts provide students with content and a context in which to write; with specific features that guide and motivate learners to write.

According to Lucke (1999), the traditional definition of a short story is: a kind of narrative that has characters, actions and plot organized in a text with a beginning, a middle and ending; this provides the best point of view for analyzing student abilities for writing short stories. The best way to become a good short story writer and gain an intuitive sense of how to write a story is by reading stories from a variety of genres (for example, mystery, science fiction, horror, romance).

Based on Hale’s (n.d.) point of view, a story is like a snake with its tail in its mouth in which the tale can end up in the same place it started. Creating a story is a process that demands a lot of practice so it means that students have to write at least for a while, every day. In addition to practice, students also have to take into consideration other aspects such as setting, problem, resolution, and point of view when they begin writing their short stories.

Teaching writing through technology

The present study identifies two valuable tools for promoting the development of the language competencies necessary for successful writing: short story analysis and composition through the use of current information and communications technology resources. The study judged the efficacy to be enhanced when developmental writing is mediated through the use of e-portfolio dossiers. The features discussed in this article provide readers with strategies that attempt to facilitate EFL teaching of writing and depict how teachers can strive to help students become short story writers.

Over the last decade, familiarity with and use of technology has become a necessity in students’school lives, and teachers have constantly sought the best practices to integrate technology with written language production. Hyland (2002) and Weigle (2002) state that electronic communication technologies have changed people’s habits of writing since nowadays people have more tools to produce better and more thoroughly revised texts. For Weigle (2002), technology affects writing in a number of ways. Firstly, the social aspect of writing becomes more relevant since people know their texts are going to be published online. Secondly, in a networked classroom, the most successful papers may not be the ones with most well-formed sentences but the ones in which authors have reflected on their teachers’comments and polished their ideas.

Taking into account that students need to be engaged in Internet-based forms of writing and that writing is a process that needs to be improved and assessed over a period of time, the electronic portfolio (e-portfolio) has emerged as a tool that integrates classroom instruction with performance assessment and, therefore, helps organize and consolidate both writing processes and products within a framework of continuous reflection and evaluation.

According to Ali (2005), the portfolio as a pedagogical tool began to gain popularity around 1986 and, with the advent of more widely accessible computing and communication technology, the e-portfolio has become the preferred expression of this tool today. Zubizarreta (2004) states that portfolios are proven, constructive instruments that faculty members can use to organize details, written in a narrative way, of their teaching accomplishments. They are effective tools in improving instruction and in providing a reliable method of assessment. Goodson (2007) refers to electronic portfolios as assessment tools required by school districts as part of periodic evaluation of teachers’ performance. He observes that this assessment system could be used to evaluate students, teachers, or administrators.

The e-portfolio could be viewed as a result of an appropriate technology use in the classroom and as a motivating tool for those students who want to share and display their work. It can also become an effective learning and assessment tool if the aims and goals are clearly stated. Various authors have referred to the multiple functions of portfolios. Some, such as Bergeron, Wermuth and Hammar (1997), acknowledge the benefits of portfolios in teacher education and development, while others, such as Barrett (2007), expand the uses of portfolio to “learning, assessment, employment, marketing and showcasing” (p.436).

Barrett (2000) describes the e-portfolio as a technological tool that enhances students’ motivation and allows students to collect and organize different artifacts in a wide array of audiovisual formats. Nowadays, e-portfolios have become very popular in the language classrooms since they offer teachers a practical and accessible strategy to assess students’ skills and knowledge (Ali, 2000). They are studentcentered instruments that involve students’ active participation from the planning through the assessment stages of the learning process. They are accessible knowledge sources that allow students to store and display their works in multiple ways through varied media sources: for example, online tools (web folios) and/or hard drives, flash drives or CD-ROMs. Moreover, they are easy to upgrade: contents can be updated from time to time depending on students’ likes, needs and growth. All in all, a portfolio can combine the features of reflective and developmental tools that assess a learner’s proficiency and provide opportunities for self- and/or peer-assessment while the demonstration of improvement and polishing of final writing piece takes place.

Bearing in mind the former assumptions, and aiming to consolidate instructional strategies that generate student interest in the development of writing skills, for the present study it was decided to analyze the effects that the different stages of the genre process approach and e-portfolio dossier implementation have on the short story writing process of senior-year secondary school students at a state school in Bogotá, Colombia.

Prior analysis and studies made in that school (Fuentes, G.& Rincón, S., 2008) revealed that:

- Students had not been motivated to write during their secondary school years.

- The instructional stategies applied in their English classes did not follow a systematic process to develop writing competences.

- Students did not understand why writing practices are useful in their academic lives.

The strengthening of proficiency in English is one of the aims that the Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN) wants to achieve by the year 2019, considering that the learning of English language will help people become more competitive in a globalized society. The current study, written in alignment with the national standards stated by the MEN in the Curricular Guidelines to Foreign Language (1999), intends to contribute to the acomplishment of this goal. The researcher believes that the findings of this study benefit both senior year and other high school students at state schools in Bogotá, as well as the wider national educational community.

Indeed, refining the writing process will not only help the students’ performance in the English classroom but will also impact other subjects included in a school’s curriculum. Although many of the approaches and methods used for teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) are specific to language classes, developing communicative skills is an interdisciplinary commitment in schools that can contribute to the successful fulfillment in learners’ academic and professional lifelong learning scenarios.

Methodology

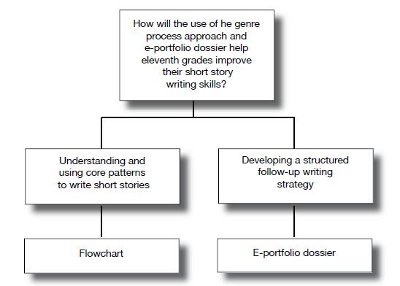

In this study, the researcher developed stages in which the students planned, drafted, and published final texts in an e-portfolio, stored at a social publishing platform called Webs. com™. This study sought to answer the following research question: How will the use of the genre process approach and e-portfolio dossier help eleventh graders improve their short story writing skills? Accordingly, the study aimed to analyze the effects that the different stages of the genre process approach and the e-portfolio dossier implementation have on the short story writing process, examine how short stories are improved following the genre process approach core features and using the e-portfolio dossier, and expand the methodological framework in the field of technology-assisted writing. This study was framed within a qualitative action research approach. Action research is a cycled process of four sequential stages (Sagor, 2005) in which different steps must be accomplished. Strauss and Corbin (1990) define the qualitative analysis as a process of examining and interpreting data in order to elicit meaning, gain understanding, and develop empirical knowledge. Taking into account that this proposal could help to improve the target students’ written proficiency, action research fitted well with the study’s main goal.

Participants

The present study was carried out in the public school INEM Santiago Pérez located in southeastern Bogotá, Colombia. The group of participants consisted of thirty-three eleventhgrade students (eighteen girls and fifteen boys aged from 15 to 17). Their English proficiency corresponded to the A1 level as defined by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages[2] . All of them knew about the project in advance and signed a consent letter authorizing the use of the material produced during the intervention.

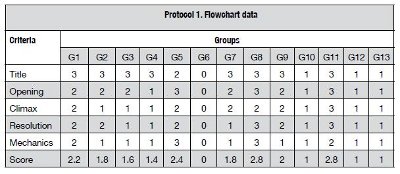

Blending a trend and a grounded analysis

The project was planned to take place over a series of ten 110-minute lessons. The school language resource center was the place selected to develop some of the online activities. The eportfolio dossier was the main instrument used for gathering evidences of students’ artifacts. A total of 13 flowcharts[3] and 13 short stories were selected to make up the samples. During the pre-intervention, the participants answered an online survey and a diagnostic test. In the postintervention, they answered a paper-based survey to evaluate the research process. Data gathered from these instruments were then analyzed and interpreted.

Initially, the researcher used the trend analysis approach (Sagor, 2005, p.110), as a useful strategy for tracing all the changes in students’ writing performance that occurred during the time the study was being implemented and, also, for answering the research question. The collected data were filtered, ranked, and analyzed to get a better understanding of the phenomenon under investigation and to produce a grounded theory regarding what might be done to solve the problem (Sagor, 2000).

To perform a trend analysis, it was necessary to synthesize the data in three steps: allocating time, looking for patterns, and creating a timeline. Then, by comparing and contrasting trends in performance (Sagor,2005,p.121), the researcher was able to see if performances were influenced by other variables. Lastly, by analyzing two more sets of data (instructional timeline and the e-portfolio dossier), the performance changes among the learners were determined.

After building a detailed analysis of the changes formerly described, the next step was the production of a grounded theory, seen as a “comparative method of analysis” (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) that gives the research process the necessary rigor to make it scientifically valid.

Intervening and implementing

Pre-intervention

An online survey was the first method used to gather information about learners’ knowledge on the writing process, about technical skills and facilities they had, and about the best communication sources to implement during the project. Additionally, the diagnosis test was another useful instrument to know about the students’ English proficiency level (vocabulary, use of language, and writing) and to carry out a conscientious needs analysis prior to the development of the study. Through the diagnostic test, it was determined that students did not have any sequential mode with which to build up a short story. There was no logical structure in their stories. Ideas were scattered and although there was an account of the characters of their stories, there was not any further elaboration as to the characters’ profile and their actions within the story. The test results also evidenced students’ lack of vocabulary and excessive use of L1 (Spanish Language).

While-intervention

During the while-intervention stage, the teacher designed an action plan to sequentially overcome the difficulties that were evidenced in the diagnostic stage. There was a series of steps performed by the teacher, which essentially aimed at improving students’ proficiency and overcome the excessive use of L1 in their writing.

The teacher outlined varied stages to model students’ writing and get learners to produce writing pieces that could be improved throughout the process. Five stages were selected (a) prewriting, b) first draft composition, c)feedback, d) second draft writing, e) proofreading), together with assessment instruments (such as fl owcharts, rubrics and e-portfolio dossiers). The teacher planned the lessons in such a way all stages could be developed. In the class sessions, the teacher constantly emphasized on the patterns pertaining to the genre the students were writing about (short stories) and students were also monitored and assessed while they elaborated their compositions. Learners moved from sentence to paragraph and whole text creation. Several strategies were used to achieve this goal i.e. peer assessment, team assessment, semantic mapping, brainstorming, mind mapping, outlining, tutor’s monitoring and prompt assessment through the use of proofreading charts, word documents and e-mail notes. Students were also trained in the use of e-portfolio dossiers: they learned how to create a digital portfolio and use it as a self-assessment tool.

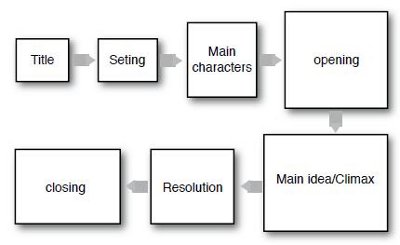

The work was performed in groups of two or three students in order to foster collaborative work and to facilitate the story creation process. The groups sent their work (artifacts) to the teacher’s by e-mail once they had created their story flowchart. These works were returned to them after the assessment period with the corresponding feedback. The students needed to fi le their works in their own e-portfolio dossier as a clear evidence of the process. Due to the fact that learners had limitations on the use of computers at school, some blended [4] lessons were developed to assist students during the project implementation stage. The flowchart below shows the suggested organization developed in the study for student use when writing short stories. This strategy worked as a graphic structuring tool that contained the core steps to write stories.

The e-portfolio dossier had to be uploaded to the students’ own web page, which was composed of four sections: About me, My learner profi le. My writing process, My own short story.

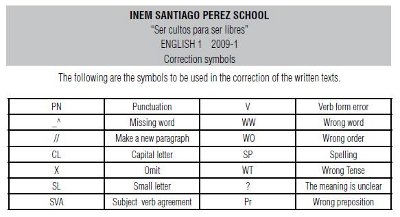

Student dossiers were reviewed on a regular basis, evaluating the contents and providing suggestions for improvement. Dossiers provided evidence of students’ progress over a period of time. Students kept their e-portfolio dossiers in their personal computers and in their USB drives or on CD-ROMs. Webs.com™ was used as a web site builder/editing tool to record student’s language improvements. (A sample is available at http://leidylozano.webs.com) From the beginning of the intervention, learners were given the assessment rubrics to evaluate their short stories and the proofreading chart that was designed for checking their work. These proofreading symbols were very useful in revising and editing their drafts and in improving their writing processes. Based on the symbol used by the teacher in her/his feedback, students had to think about the best way of revising and correcting their text. It was a hands-on exercise.

Finally, a paper-based survey was applied to gather information about how students evaluated the process and the fi nal results. As validity is an essential criterion for evaluating the quality and acceptability of the research (Burns, 1999), subjectivity was avoided by taking the students’ points of view on the study’s fi nal conclusions and using of rubrics to evaluate the instruments’ effectiveness. Triangulation was also used to check the study’s validity. This was the data analysis approach used to cross-check the information and state the fi nal categories. These emerged from the commonalities found after analyzing each of the instruments: the refl ections in the teachers’ blog, the surveys, the fl owchart and the two short story drafts.

Findings

The most frequently observed patterns (those occurring three or more times in the researchers’ annotations, Sagor, 2005, p.116) were summarized to fi nd the categories used to answer the research question. This analysis revealed that the combination of two strategies enabled students to understand, use and evaluate their story writing competency. These strategies are illustrated and commented upon below.

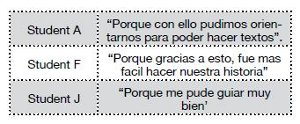

The analysis of the fl owcharts obtained in the pre-writing stage revealed patterns of clarity, creativity, attractiveness and effectiveness. Five features were assessed in the fl owchart: Title, Opening, Climax (Problem), Resolution and Mechanics. Each one of these features was registered in a protocol form for data analysis. Group performances were subsequently compared and analyzed.

Review of the flowcharts provided evidence of how the students initially organized their short stories. Given that, at this stage, students had to shape their thoughts and make decisions as to agents and actions involved in the story, it can be seen that this strategy provided students with a sequential scheme on which to base their thoughts. Additionally, it was found that certain features such as clarity, creativity, attractiveness and effectiveness became recurrent patterns of analysis throughout the data processing stage.

Clarity was examined through the students’ capacity to transmit thoughts and provoke consistent relationships between the different story elements (such as characters, settings, situations, and genre). The sentences listed in the flowcharts showed short but clear ideas. Results indicate that students had clarity of diction and sentence structure. Most of the groups were consistently interested in including additional information in their flowcharts as they organized and produced the preliminary sections of their short story. Sharing ideas, peer assessment, tutor’s monitoring and prompt assessment facilitated the control of students’ performance and guided them towards the first draft stage.

Creativity was analyzed according to the students’ originality in creating the story’s characters, settings, situations and genre. The study revealed that students were able to elaborate a composition that mixed fictional and real characters and contexts based on their prior knowledge and their points of view about life.

Attractiveness was evaluated as to the students’ capacity to arouse interest in the reader by posing an interesting topic, catchy plot and also proposing an innovative procedure to carry out the resolution of the story problem. The topics selected by students ranged from passionate love stories to crime fiction and ghost tales. All the stories developed a problematic situation that in the end was resolved. It was also noted that the most recurrent theme was death.

Effectiveness was evaluated with regard to the students’ capacity to use the flowchart: to write the first composition and the final draft showing an improvement in their short story writing process. Data indicated that the sections containing the flowchart enabled them to create a mental structure of their story. The majority of students reported that their ideas resulted from the association of words with concepts and categories (semantic mapping strategy).

Extracts from students’ comments

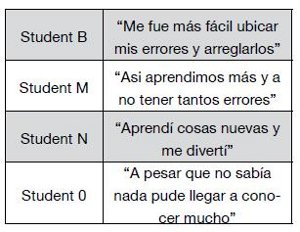

During the while-intervention writing stage, the first students’compositions and the final draft were assessed using the same set of rubrics but the occurrences were different for each instrument. In the first composition, the first evaluated aspect was the story structured sequence. This relates to the organization of the story,the connections between its parts: beginning, middle and ending. The groups’ stories maintained the structures initially drawn in the flowchart. Students’ improvements in the texts was noticeable in 76% of the class. For the remaining 14%, it was noticeable that students maintained the same performance and score as in the first draft, with no major changes or additions.

The second observed aspect (setting) gave an account of the way student-writers created the story’s environment. According to McCoy (2002), if there is no a setting, there is no story. Characters need a believable background that helps deliver their story as they grow, and the plot must be developed in an specific setting, keeping in mind the kind of story the student wants to tell. Students were reminded of the importance of creating characters immersed in a context in order to develop their stories feasibly. Data analysis showed that all the groups worked effectively to create fictional characters and credible situations. Generally, most of the students were in agreement about this aspect in both stages (first and final composition): for them, it was interesting to construct the storyline as a team. There were few/no cases of groups who showed discontent with their characters and chosen situations.

The third analyzed aspect showed how the story characters, setting and genre merged to convey logical relationships within the story. In conversations with the groups, a 100% of the students agreed that the aspects outlined in the Flowchart and the suggested order and relationship between them (indicated by arrows) enabled them to know what ideas preceded others. There was no difficulty in determining what the opening or the resolution should contain. Each section had logical and related ideas within the text.

The fourth aspect (cohesion-coherence) examined how clear and logical connections between ideas were presented in the story, so that readers could easily follow the storyline without any difficulty. All the groups had difficulty making paragraph-to-paragraph connections when moving from one part of story to another. Some students made tangential connections between ideas with ambiguous cause-effect relationships. The teacher emphasized and provided students with strategies such as mind mapping and outlining in order to assist them in identifying possible grammatical, lexical and semantic links that could connect parts of their texts to other parts.

In the final draft the first evaluated aspect was corrected mistakes; the second observed aspect was making improvements. Results indicated that in these stages, the majority of the students showed interest in finding out how to correct their mistakes. Students also displayed a positive attitude about their creations and openly expressed their enjoyment of each stage of the writing process. The majority of them was engaged with and committed to the improvement of their writing processes. Most of them used the commentaries, assessment provided by the teacher (via proofreading charts, word documents and e-mail notes) to improve their writing.

The last aspect in the writing process referred to the reasons why the students made new mistakes. Data analysis revealed students’ lack of attention, lack of training in the use of word processing tools and lack of English language mechanics. Some groups had difficulty in using MS Word™ tools such as Insert/Delete comment and Track Changes. When the teacher e-mailed the feedback to students, some students decided to rewrite a new text instead of revising the section on which the teacher had commented.

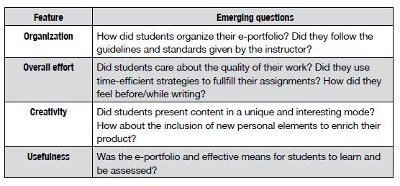

During data analysis, a new stage was discovered that helped students see the writing process holistically. In this new stage, apart from creating individual drafts, students could understand that the final product implies a systematic process of writing development. This integrated stage also reminded them of the importance of following specific steps in order to achieve the creation of an elaborate product. The criteria that emerged from the e-portfolio creation included the following features: organization, students’overall effort, creativity and usefulness. In conclusion, during this phase, two cognitive processes were being developed simultaneously. One related to the process of learning the specificities of short stories as genre and learning to write them; the other related to the organization of the e-portfolio.

The table below illustrates the related focus for each criteria:

Dealing with time and group issues

The while-writing stage took more time than the researcher had anticipated in the production and correction of students’ short stories (45%). Less than a fifth (13%) of class time was spent on the pre-intervention writing stage and on tutorials about how to create and optimize the use of the e-portfolio. However, in the end, the time planned for socialization was not used because of some external issues that affected the normal development of the project (such as state school strikes and facility problems).

The information collected for certain weeks in the grading book was analyzed by comparing class groups’ performances. In general, there was a slight tendency towards improvement in the short story writing in terms of aspects such as general structure, layout, cohesion and coherence.

The artifacts (stories) were created both in an individual and collaborative mode. Although students were meant to work together in groups to support each other’s work within the group, in practice a single student usually came to dominate the activities of each group. This student was generally the leader of the group, a learner who best committed to make revisions and improvements to the compositions, a student who guided his/her team members to stay focused on the tasks and to be organized and time- efficient

Implementing the e-portfolio

Another recurrent pattern was the dedication and interest shown by most of the learners for the use of the e-portfolio dossier as a learning tool. Despite the fact that the students did not have optimal access to computers and the Internet in their school, they developed most of the activities successfuly and participated actively in the improvement of their short story writing process by doing the online and digital work at home or in Internet cafés.[5]

Organizing the data for analysis

Initially, after an exhaustive reading of all the information collected during the project’s intervention, it was classified and reduced by making lists of the available data. Each one of these lists was organized, named, and focused on the most meaningful data to help answer the research question. Listing was the strategy selected to highlight the most important issues, ideas and situations that could provide clear evidence on the study’s results.

Taking into account the twofold nature of the research question, it was necessary to separate the instruments in two different files: Genre-process approach (GPA) and e-portfolio dossier. The GPA file contained all the meaningful instruments that were used during the pre- and while-writing stages to improve students’ short story writing process. In the e-portfolio file, evidence of students’ development in the construction of their own web pages was stored chronologically. Due the great amount of collected information, the deductive (theory-driven) approach suggested by Miles and Huberman (1994) was used for reducing and systematizing the data.

First of all, a coding schema was developed based on the key themes that emerged from the data processing. It was useful to describe and explain the pattern of relationships and interactions because data could be grouped according to clearly defined codes. Frequently revisiting the records in the researcher’s computer allowed visualization of the different stages during the short story writing process. From this exercise, the first labels emerged. This was a list that resembled the one that included the five writing process stages stated by O’Brein (2004).

When the chosen instruments were examined, commonalities between the different labels were established. Afterwards, these commonalities were displayed in a matrix that revealed the emerging categories. It was necessary to frequently check the records to count the occurrence of each label in each instrument. Having the numbers for all the labels and revisiting the data, labels were grouped according to the issues presented in them. The coding process was the first step in the data reduction, and it began by describing the attributes of the different resources and identifying commonalities between the different labels. The commonalities were coded with abbreviations of key words (Marshall,1999).

According to Strauss and Corbin (1990), categories are formed by grouping similar incidents, events or other instances of phenomena under the same label. After revising the data with the aim of finding the commonalities to answer the action research question, a new sub-question about the actions performed by the learners in each one of the writing process stages emerged from the analysis: What specific actions will the learners carry out to improve the short story writing process and the implementation of the e-portfolio dossier?

Discussion of findings

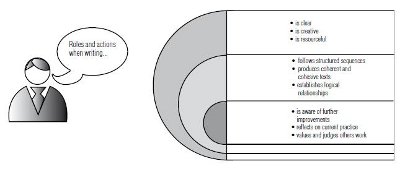

Three main categories emerged from data analysis: student—writer as a planner, studentwriter as a builder, and student-writer as a reviewer. The following diagram illustrates these findings.

The student-writers as planners (SWP) are learners who are able to organize effective texts; that is to say, these are learners who outline their ideas clearly in a scheme (namely a chart, a flowchart, or a mind map) and show evidence of gathering the elements that make of their written work a simple, precise and concise unit. SWPs are also creative and original, and they produce appealing texts that catch the reader’s attention. Moreover, they are resourceful in problem solving and making decisions.

Student-writers as builders (SWB) are learners who are able to narrate well-structured stories. These learners take into account the outlining structure of short stories to produce well thought-out and sequential narrative texts. Moreover, they are aware of the importance of being cohesive and coherent through the whole text. Cohesion refers to the grammatical and lexical links used to join sentences together, avoiding unnecessary repetitions. This includes the use of synonyms, lexical sets, pronouns, verb tenses, time references, and grammatical references. Coherence is related to the manner in which sequences of ideas are clearly and logically organized. Additionally, SWBs maintain consistent relationships between characters and between characters and setting, taking into account the context in which the story takes place.

Student-writers as reviewers (SWR) are learners who are able to reflect on their writing development in order to carry out further improvements. SWRs are able to use the teacher’s feedback to elaborate their drafts and/or add new ideas to produce a better version of their stories. They are also able to discuss their peers’ work and collaborate on its improvement.

One of the main findings of this study was that learners showed progressive improvement in their short story writing processes as evidenced in the evaluation done for each one of the instruments filed in their e-portfolios. The instructional strategies used in the study proved to be effective to assist students in the development of their short story writing. Learners gradually built and enjoyed the process of writing short stories having in mind the core features of the genre, learning to write them and using the e-portfolio as a tool to organize and self-assess their progress. Although not all of the students participated in the same way within their groups, it must be said that the major achievements were seen in terms of personal benefits, opposed to collective benefits. The role dominance of a student in each one of the groups denoted the absence of a team working together to achieve goals successfully (Brown, 1994, p.81).

Additionally, it was found that students’ and the teacher’s roles transcended an active learning dimension. Students emerged as self-directed and responsible learners, which enabled them to become planners, builders and reviewers of their own short story writing process. Likewise, the instructor/researcher emerged as an enabler of collaborative learning: Her role changed from being a lecturer to becoming a facilitator, from controller of a teaching environment to a cocreator of a learning experience (Labonte,2003): an instructor who, supported by documented research, was also able to make informed teaching decisions.

In spite of the problems caused by the lack of technological resources in the school, the new roles adopted by learners were developed in the different writing stages and also in the use of the e-portfolio dossier. The e-portfolio dossier allowed them to be aware of their progress over a period of time and proved to be a useful means to teaching, learning and assessment.

The instruments involved lots of planning and effort. The use of rubrics and the proofreading chart was functional because students could find support to review their drafts, reflect upon their mistakes and self-correct them before writing the final version of their stories. Training students in the use of these assessment instruments helped them understand how they worked. It can also be concluded that despite the fact that learners had very little English, it was possible for them to write short stories. Realizing that they had made something new with the very limited English they had was very motivating and productive for them.

Limitations

Technical problems related to Internet connection and computer room availability forced students to use internet cafés as a strategy to develop the project. As a result, students took more time than the estimated for creating, editing and proofreading their drafts. Moreover, teacher assessment time increased significantly as new student tutorials had to be planned asynchronously (via e-mail) or in different classtime (for example, during recess or other courses’ classes).

Directions for further research

Further research is needed to investigate the effect of collaborative work in the writing process through the use of e-portfolio dossier. Understanding how the members of a group can achieve writing goals under standard conditions could be beneficial not only in planning their writing development but also in approaching their different learning styles and in providing students with new learning opportunities within a community of builders. To develop similar studies, learning strategies and technology training need to be leveled according to each student’s case to achieve the desired outcomes.

References

Ali, S.Y. (2005). An introduction to electronic portfolios in the language classroom. Retrieved November 16, 2008 from: http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Ali-Portfolios. html

Badger, R. and G. White. (2000). A process genre approach to teaching writing. ELT Journal. 54 (2), 153-160.

Barrett, H. (2000). Create your own electronic portfolio, Retrieved November 15, 2008 from http://www. electronicportfolios.com/portfolios/iste2k.html

Barrett, H. (2007). Researching electronic portfolios and learner engagement: the reflect initiative. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 50 (6), 436-449.

Bergeron, B., Wermuth, S. & Hammar, R. Initiating portfolios through shared learning: Three perspectives. (1997). The Reading Teacher. 50 (7), 552-562

Brown, D. (1994). Teaching by principles, an interactive approach to language pedagogy. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. (2001). Council of Europe. Europe: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved on November 13, 2009 from http://www. uta.fi/laitokset/kielikeskus/CEF/CEF.htm

Fuentes, G. & Rincón, S. (2008). Improving short story writing through e-portfolios. Project developed in the teacher development program (TDP) at Universidad de La Sabana. Bogotá.

Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. (1967).The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Goodson, T. (2007). The electronic portfolio: shaping an emerging genre. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 50 (6), 432-434.

Hale, B. (n.d.) How to write a story. Retrieved February 25, 2009 from http://www.brucehale.com/howto. htm

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching. Edinburgh Gate, Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Hyland, K. (2002). Teaching and researching writing. Malaysia: Pearson Educated Limited.

LaBonte, Randy et al (2003). Moderating tips for synchronous learning using virtual classroom technologies. Odyssey Learning Systems Inc. Retrieved from http://odysseylearn.com/Resrce/text/e- Moderating%20tips.pdf

Lingzhu, J. (2009). Genre-based approach for teaching English factual writing. HLT Magazine. Retrieved on November 1, 2009 from http://www.hltmag.co.uk/ apr09/mart02.htm

Lucke. M. (1999). Schaum’s quick guide to writing great short stories. U.S.A.:McGraw Hill Companies. Retrieved on February 25, 2009 from http://books. google.com.co/books?id=qoYNPolwZ-QC&prints ec=frontcover&source=gbs_v2_summary_r&cad= 0#v=onepage&q=&f=false

McCoy, C. (2002). Creating the perfect setting for writing fiction. Retrieved on June 18, 2009 from http://www. essortment.com/all/writingfiction_rcck.htm

Marshall, C. (1999). Designing qualitative research. London: Sage Publications.

Miles, M. & Huberman, M. (1994).Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2006). Estándares básicos de competencia en lengua extranjera. Formar en lenguas extranjeras. Bogotá.

O’Brien, T. (2004). Writing in a foreign language: Teaching and learning. Language Teaching. 37 (1), 1-28.

Piccardo, E. (2009). Creative computing in EFL. HLT Magazine. Retrieved on November 1st. 2009, from http://www.hltmag.co.uk/sep03/mart4.htm

Sagor, R. (2000). Guiding school improvement with action research. Alexandria,VA: Association for Supervision and Curricular Development.

Sagor, R. (2005). The action research guidebook. Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Salem, N. (2009). Teaching writing: helping second language writers experience a sense of ownership of their writing. Retrieved on November 2, 2009 from http://www.nadasisland.com/teachingwriting.htm

Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1990) . Basics of qualitative research –grounded theory. Procedures and techniques. London: Seige Publications.

Tangpermpoon, T. (2008). Integrated approaches to improve students writing skills for English major students. Retrieved November 20, 2008 from http://www.journal.au.edu/abac_journal/2008/ may08/01(1-9)_article01.pdf

Tribble, C. (1996). Writing. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Webs.com (2009). Website builder. Retrieved January 12, 2009 from http://www.webs.com/

Weigle, S. (2002). Assessing writing. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wright, A. (2009). Making stories with little language. HLT magazine. Retrieved on November 1st, 2009 from http://www.hltmag.co.uk/oct09/less04.htm#C1

Zubizarreta, J. (1994). Teaching portfolios and the beginning teacher. The Phi Delta Kappan.76 (4), 323-326

Notas

[1]According to the Common European Language Framework for Languages (2001), a portfolio contains three parts: My Biography, My Passport and My Dossier. The e-portfolio’s dossier is a learning instrument or a value source of information used by learners, during a period of time, to reflect on and record their achievements and language-learning experiences.

[2]An A1 language user can understand and use familiar everyday expressions and very basic phrases to meet specific needs. Can introduce him/herself and others, ask and answer questions about personal details. Can interact in a simple way (CEF, 2001).

[3]A flowchart is a visual representation of a story sequence. It is a working map that allows student-writers to visualize all the major steps and elements involved in the writing process.

[4]Blended lessons refer to classes with an online and a face-to-face component.

[5] café internet is a public commercial place where people access to the Internet service .

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.