DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/21450706.18301Publicado:

2021-07-30Número:

Vol. 16 Núm. 30 (2021): Julio-Diciembre de 2021Sección:

Sección CentralFusiones y adquisiciones: El caso de São Paulo

Mergers and acquisitions: The case of São Paulo

Mergers and acquisitions: the São Paulo case

Descargas

Referencias

Abbing, H. (2002). Why are artists poor? The exceptional economy of the arts. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Adler, M. (1985). Stardom and Talent. The American Economic Review, 75(1), 208–212.

Aldrin Silva, R. (2018). “Desigualdade de renda cresce em quinze estados brasileiros”. Fundação Perseu Abramo.https://tinyurl.com/kd72ddh

Allmers, S., and Maennig, W. (2009). Economic Impacts of the FIFA Soccer World Cups in France 1998, Germany 2006, and Outlook for South Africa 2010.

Eastern Economic Journal, 35(4), 500–519.

Álvarez Bautista, J. R. (1983). El valor de las definiciones. Contextos, 1, 129–154.

Angeleti, G. (2019). “Brazil’s museums dodge Bolsanaro’s cultural funding caps—at least for now”. The Art Newspaper. https://tinyurl.com/cy687dzn

Aristotle. (1996). Poetics. New York: Penguin Books. Aristotle. (2014). Ética a Nicómaco. Madrid: Gredos.

Art+. (2020). “Survey Results: Impact of New Coronavirus Pneumonia Outbreak on the Chinese Art World”. Art Market Journal. https://tinyurl.com/22h39yzm

ArtPrice. (2019). The Contemporay Art Market Report 2018. Paris: ArtPrice.

ArtPrice. (2020). The Contemporay Art Market Report 2019. Paris: ArtPrice.

Baade, R. A. and Matheson, V. A. (2016). Going for the Gold: The Economics of the Olympics. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(2), 201–218.

Balfe, J. H. (1987). Artworks as symbols in international politics. International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, 1(2), 195–217.

Baumol, W. J. (1962). On the Theory of Expansion of the Firm. The American Economic Review, 52(5), 1078–1087.

Becker, H. S. (2008). Art worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bermúdez, J. L. (2002). Art and morality. New York: Routledge.

Bevins, V. (2014). “Market Forces”. ArtReview, July 21, 2014. https://tinyurl.com/pt4yvhr6

Biller, D. (2019). “Brazil’s income inequality hits highest since at least 2012”. abc News. https://tinyurl.com/jcummn2h

Bohlen, C. (2001). “Guggenheims and the Hermitage Bust Open Vegas”. The New York Times, October 13, 2001. https://tinyurl.com/3wxp5ywz

Bourdieu, P. (1988). La distinción: criterios y bases sociales del gusto. Madrid: Taurus.

Brandellero, A., and Velthuis, O. (2018). Reviewing art from the periphery. A comparative analysis of reviews of Brazilian art exhibitions in the press. Poetics, 71, 55–70.

Buchli, V., et al. (2001). The material culture reader. New York: Berg.

Buck, L. (2004). Market matters: the dynamics of the contemporary art market. London: Arts Council England.

Cahn, S. M. (2008). Aesthetics: a comprehensive anthology. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Canzian, F., et al. (2019). “Los súper ricos en Brasil lideran la concentración de la renta global”. Folha de S. Paulo. https://tinyurl.com/2j942rd4

Caracol Radio. (2007). “Colombia renuncia a su postulación para el Mundial de Fútbol 2014”. Caracol Radio. https://tinyurl.com/fsysjsw

Castiñeiras, M. A. (2008). Introducción al método iconográfico. Barcelona: Ariel.

Danto, A. C. (1964). The Artworld. The Journal of Philosophy, 61(19), 571–584.

Danto, A. C. (2002). La transfiguración del lugar común: una filosofía del arte. Barcelona: Paidós.

Danziger, C., and Danziger, T. (2014) “On the Case: Exploring Real World Art Law Issues”. Artnet. https://tinyurl.com/je44r268

Day, G. (2014). Explaining the Art Market’s Thefts, Frauds, and Forgeries (And Why the Art Market Does Not Seem to Care). Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law, 16(3), 457–495.

Dickie, G. (1974). Art and the aesthetic: an institutional analysis. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Dickie, G. (2005). El círculo del arte: una teoría del arte. Barcelona: Paidós.

Eco, U. (2010). History of beauty. New York: Rizzoli.

EFE. (2017). “El Louvre abre sucursal en Abu Dhabi por 1.000 millones de euros”. El Español. https://tinyurl.com/pkcfyyjb

EFE. (2008). “Un Banksy a precio de oro”.

El País. https://tinyurl.com/ynunadk7

FGV-DAPP. (2007). “Rouanet Law funds falling since 2010”. FGV-DAPP. https://tinyurl.com/4h9prxn3

FIFA. (2003). “2014 FIFA World Cup TM to be held in South America”. FIFA. https://tinyurl.com/5hz68hr9

Fleming, T. (2018). The Brazilian Creative Economy. London: British Council.

Peñuela, J. (2007). Pensar en Platón: la problemática de lo bello contemporáneo. Calle 14: Revista de investigación en el campo del arte, 1(1), 111–126.

Fraiberger, S. P., et al. (2018). Quantifying reputation and success in art. Science, 362(6416), 825–829.

Frank, R. H., and Bernanke, B. (2007). Principles of economics. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Frey, B. S. (2000). L’Economia de l’art. Barcelona: La Caixa Servei d’Estudis.

Gilbert, K., and Kuhn H. (1972). A History of Esthetics. New York: Dover Publications.

Harillo Pla, A. (2018). Primavera en las galerías de arte de Shanghái. Calle 14: Revista De investigación En El Campo Del Arte, 13(24), 438-449.

. (2016). Arte en el DRAE. Entre significado y referencia. Eikasia: revista de filosofía, 68, 265–290.

Harillo Pla, A. (2017). El arte en España: una crítica a su legislación. ArtyHum: Revista de Artes y Humanidades, 32, 20–40.

Harillo Pla, A. (2019). An insight into the artistic institutional globalization. Paper presented at Annual International Scientific Conference. Art and Art History at the Present Stage. Cultural Interaction and Globalization, Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts, Saint Petersburg, 2019.

Hayter, R., and Patchell, J. (2016). Economic geography: an institutional approach. Don Mills: Oxford University Press.

Hegel, G. W. (2006). Filosofía del arte o estética. Madrid: Abada Editores.

Hendrix, J. S. (2005). Aesthetics & the philosophy of spirit: from Plotinus to Schelling and Hegel. New York: Peter Lang.

Herbert, M. (2016). Tell them I said no. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Hermoso, B. (2015) “El Pompidou fondea en Málaga”.

El País. https://tinyurl.com/k73fjyp5

Hicks, D., et al. (2010). The Oxford handbook of material culture studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hume, D. (2013). Of the standard of taste. Birmingham: Birmingham Free Press.

Hyman, J. (2002). Is the Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder. Think, 1(1), 81–92.

Jacoby, J., et al. (1971). Price, brand name, and product composition characteristics as determinants of perceived quality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 55(6), 570–579.

Kant, I. (2008). Critique of judgement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kinsella, E. (2019). “No Lease? No Problem! This Company Wants to Bring Your Gallery to Cities Around the World”. Artnet. https://tinyurl.com/tjufbjcc

Kotler, N. G., and Kotler, P. (2001). Estrategias y marketing de museos. Barcelona: Ariel.

Kotler, N. G., and Kotler, P. (2011). “Artist Employment Projections through 2018”. NEA Research Bulletin, 103, 1-14.

Latitude, et al. (2018). Sector Report: The Contemporary . (2016). Creativity connects: trends and Art Market in Brazil. São Paulo: Associação Brasileira de Arte Contemporânea.

Layton, R. (1991). The anthropology of art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levinson, J., et al. (2003). The Oxford handbook of material culture studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Longman, G. (2019a) “As Brazil turns a corner, will local market follow?”. Folha de S.Paulo. https://tinyurl.com/y3b8b5we

Longman, G. (2019b) “Galeria Almeida & Dale é investigada pela Lava Jato por lavagem de dinheiro”. Folha de S.Paulo. https://tinyurl.com/34ajcxun

Machamer, P. K., and Roberts, G. W. (1968). Art and Morality. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 26(4), 515–519.

Madeiros, M. (2016). World social science report 2016: challenging inequalities, pathways to a just world. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

Martí, S. (2019). “Galerias brasileiras vão à meca dos bilionários para fugir da bancarrota”. Folha de S.Paulo. https://tinyurl.com/29eratcy

McAndrew, C., et al. (2020). The impact of Covid- 19 on the art market. Paper presented at Art Basel Conversations, online, 2020.

Meheus, J. (2002). A history of six ideas: an essay in aesthetics. Dordrecht: Springer.

Michaud, Y. (2009). Filosofía del arte y estética. Disturbis 6: w/p.

Morgan, R. C. (1998). The end of the art world. New York: Allworth Press.

NEA. (2009). “Artists in a Year of Recession: Impact on Jobs in 2008”. NEA Research Bulletin, 97, 1-10. conditions affecting U.S. artists. Washington DC: National Endowment for the Arts.

NEA. (2019). Artists and Other Cultural Workers: A Statistical Portrait. Washington DC: National Endowment for the Arts.

Neri, M. (2019). Inequality in Brazil. Inclusive growth trend of this millennium is over. UNU-WIDER 1/2019: w/p.

Neuendorf, H. (2017). “Brazil’s Art Market Isn’t Even Close to Its World-Class Potential. Here’s Why”. Artnet. https://tinyurl.com/brznazfz

Oxfam. (2017). “Brazil: extreme inequality in numbers”. Oxfam. https://tinyurl.com/hezwuzju

Öztürkkal, B., and Togan-Egrican, A. (2019). Art investment: hedging or safe haven through financial crises. Journal of Cultural Economics, 43(4), 1–49.

Piquer, I. (2001). “El Guggenheim abre dos museos en Las Vegas”. El País. https://tinyurl.com/8vj76u5j

Preuss, A. (2018). “Banksy painting ‘self-destructs’ moments after being sold for $1.4 million at auction”. CNN. https://tinyurl.com/ee9ups

Quemin, A. (2013). Les stars de l’art contemporain notoriété et consécration artistiques dans les arts visuels. Paris: CNRS éditions.

Ragin, C. C. (2014). The Comparative Method: Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rascón Castro, C. (2009). La economía del arte. México: Nostra Ediciones.

Rede Nossa São Paulo. (2019). “Mapa da Desigualdade 2019 é lançado em São Paulo”. Rede Nossa São Paulo. https://tinyurl.com/ynfsr88nRenate, M., et al. (1975).

Introducción a los métodos de la Sociología empírica. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

Rede Nossa São Paulo. (2010). “Artist Unemployment Rates for 2008 and 2009”. NEA Research Bulletin, 1-06.

Rojas, L. (2018). “As Brazil turns a corner, will local market follow?”. The Art Newspaper. https://tinyurl.com/2hsvtnsx

Rose, A. K., and Spiegel, M. M. (2011). The Olympic Effect. The Economic Journal, 121(553), 652–677.

Roselius, T. (1971). Consumer Rankings of Risk Reduction Methods. Journal of Marketing, 35(1), 56–61.

Rosen, S. (1981). The Economics of Superstars. The American Economic Review, 71(5). 845–858.

Sacristán, M. (1973). Introducción a la lógica y al análisis formal. Barcelona: Ariel.

Santana Viloria, L. (2019). La feria comercial de arte como espacio de redistribución de capital simbólico. Calle 14: Revista de investigación en el campo del arte, 14(25), 72–85.

Schelling, F. W. (1989). The philosophy of art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Shiner, L. E. (2001). The invention of art: a cultural history. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Sklar, R. L. (1976). Postimperialism: A Class Analysis of Multinational Corporate Expansion. Comparative Politics, 9(1), 75–92.

Solimano, A. (2019). The Art Market at Times of Economic Turbulence and High Inequality. Paper presented at Seminar Series at the European Investment Bank, Luxembourg, 2019.

Solimano, A., and Solimano, P. (2020). Global Capitalism,

Wealth Inequality and the Art Market. In Handbook of Transformative Global Studies. Edited by Hosseini, Hamed, et al. New York: Routledge.

Souza, B. (2015). “Os 10 estados com as piores taxas de desigualdade de renda”. Exame. https://tinyurl.com/m4j6eva8

Stigler, G. J. (1984). Economics: The Imperial Science?. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 86(3), 301–313.

Svašek, M. (2007). Anthropology, art and cultural production. London: Pluto Press.

Tatarkiewicz, W. (1980). A history of six ideas: an essay in aesthetics. Boston: Kluwer Boston.

Tatarkiewicz, W., et al. (2005). History of Aesthetics. New York: Continuum.

Velthuis, O. (2016). The Brazilian Art World Is Here To Stay, Economic Crisis Or Not. Paper presented at Debates: Colección Cisneros, online, 2016.

Vickers, P. (2014). Theory flexibility and inconsistency in science. Synthese, 191(13), 2891-2906.

Vilar Roca, G. (2005). Las razones del arte. Boadilla del Monte: Antonio Machado Libros.

Wallerstein, I. M. (2011). The Modern World-System I. Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wickham, M., et al. (2020). Defining the art product: a network perspective. Arts and the Market, 10(2), 83–98.

Wilson, N. C., and Stokes, D. (2005). Managing creativity and innovation: The challenge for cultural entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12(3), 366–378.

Wolff, J. (1993). The social production of art. New York: New York University Press.

Worthington, A. C., and Higgs, H. (2004). Art as an investment: Risk, return and portfolio diversification in major painting markets. Accounting & Finance, 2(44), 257–271.

Zimbalist, A. S. (2015). Circus maximus: the economic gamble behind hosting the Olympics and the World Cup. Washington D. C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Zimbalist, A. S. (2017). The Economic Legacy of Rio 2016. In Rio 2016: Olympic Myths, Hard Realities. Edited by Andrew S. Zimbalist. Washington D. C.: Brookings Institution Press, pp. 207–238.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Sección Central

Fusiones y adquisiciones: El caso de São Paulo

ergers and acquisitions: the São Paulo case

Fusions et acquisitions : le cas de São Paulo

Mergers and acquisitions: the São Paulo case

Fusiones y adquisiciones: El caso de São Paulo

Calle14: revista de investigación en el campo del arte, vol. 16, núm. 30, pp. 278-296, 2021

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional.

Recepción: 10 Junio 2020

Aprobación: 08 Agosto 2020

Resumen:

Según datos recientes del mercado del arte, unos pocos agentes institucionales tienen una gran cuota de mercado. En consecuencia, el mercado del arte se compone cada vez más de una serie de estrellas en el sentido de Rosen y Adler. Estas diferencias se maximizan en períodos de crisis. En Brasil y, más concretamente, en São Paulo, dos agentes sobrevivieron a la crisis económica posterior a los Juegos Olímpicos y el Mundial de Fútbol con una propuesta innovadora: expandir su negocio mediante fusiones y adquisiciones. Antonio Almeida y Carlos Dale se dedican a comprar galerías rivales. En un país tan desigual económicamente como Brasil y, especialmente, el Brasil después de la crisis económica, esto es especialmente posible. Veremos algunas de las ventajas competitivas que esta práctica puede aportar a estos dos agentes.

Palabras clave: Arte contemporáneo, innovación, mercado del arte, mundo del arte, São Paulo, teoría institucional.

Abstract:

According to recent data from the art market, a few institutional players have gained a large market share. Consequently, the art market is increasingly made up of a series of stars in the sense of Rosen and Adler. These differences are maximized in periods of crisis. In Brazil and, more specifically, in São Paulo, two agents survived the economic crisis after the Olympic Games and the World Cup with an innovative proposal: to expand their business through mergers and acquisitions. Antonio Almeida and Carlos Dale are buying rival galleries. In a country as economically unequal as Brazil, and especially Brazil after the economic crisis, this is especially possible. We will study some of the competitive advantages that this practice can bring to these two agents. Contemporary art; innovation; art market; art world; São Paulo; institutional theory Fusions et acquisitions : le cas de São Paulo

Keywords: Contemporary art, innovation, art market, art world, São Paulo, institutional theory.

Résumé: Selon les données récentes du marché de l’art, quelques acteurs institutionnels détiennent une part de marché importante. Par conséquent, le marché de l’art est de plus en plus constitué d’une série de stars au sens de Rosen et Adler. Ces différences sont maximisées en période de crise. Au Brésil et plus particulièrement à São Paulo, deux agents ont survécu à la crise économique après les Jeux Olympiques et la Coupe du monde avec une proposition innovante : développer leur activité par des fusions et acquisitions. Antonio Almeida et Carlos Dale rachètent des galeries rivales. Dans un pays économiquement aussi inégalitaire que le Brésil, et surtout le Brésil après la crise économique, cela est tout-à-fait possible. Nous étudierons quelques-uns des avantages concurrentiels que cette pratique peut apporter à ces deux agents.

Mots clés: Art contemporain, innovation, marché de l’art, monde de l’art, São Paulo, théorie institutionnelle.

Resumo: Segundo dados recentes do mercado da arte, uns poucos agentes institucionais têm uma grande cota de mercado. Em consequência, o mercado da arte se compõe cada vez mais, de uma série de estrelas no sentido de Rosen e Adler. Essas diferenças se maximizam em períodos de crise. No Brasil, e mais concretamente em São Paulo, dois agentes sobreviveram a crise econômica posterior aos Jogos Olímpicos e ao Mundial de Futebol com uma proposta inovadora: expandir seu negócio mediante fusões e aquisições. Antonio Almeida e Carlos Dale se dedicam a comprar galerias rivais. Em um país tão desigual economicamente como o Brasil e, especialmente, o Brasil depois das crise econômica, isso é especialmente possível. Veremos algumas das vantagens competitivas que esta prática pode trazer para esses dois agentes.

Palavras-chave: arte contemporânea, inovação, mercado da arte, mundo da arte, São Paulo, teoria institucional.

Art and uncertainty1

It is difficult to know what we mean when we name something as ‘art’. Many cultures have a similar word, however that does not mean they give the same significance to the same thing. In fact, sometimes, even within the same society, different individuals may have a different material culture and call different things as ‘art’, being this one, a polysemic word. (Buchli et al., 2001; Hicks et al., 2010; Layton, 1991; Svašek, 2007)

(A) Ontologically, some disciplines such as philosophy have tried to provide general knowledge about it, with little success. (Cahn et al., 2008; Schelling, [1859] 1989). This little success is because, (A1) Philosophy has generally carried out an idealistic and almost romantic analysis of what art is. A theoretical analysis that was rarely based on a significative empirical testing of facts, but mainly, on simple individualism and subjective criteria. (Hendrix, 2005; Aristotle, 1996). Thus, discussions provided from aesthetics have focused their efforts on questions like what or which are the aesthetic categories, if the aesthetic sense is innate or learned, or if aesthetics must be linked or not to morality. (Hyman, 2002; Kant, [1790] 2008; Eco, [2004] 2010; Hume, [1757] 2013; Bermúdez et al., 2002; Machamer and Roberts, 1968; Peñuela, 2007).

However, a historical and even sociological analysis shows us that these aesthetic categories are also the fruit of the convention, and that they vary from one place and moment to another (Shiner, 2001). This is what from the iconology, experts name as ‘contamination’ or as ‘reinterpretation’. An example is the Aphrodite of Knidos. The representation of the goddess, being naked, was not permitted in the island of Kos. However, it was accepted in Knidos. After this acceptance and “once the message is integrated into the code of Greek art, the theme of Aphrodite totally naked will be endlessly repeated” (Castiñeiras, 2008, p. 29; Castiñeiras, 2008, p.104). Not less important is the fact that the transmission of a concept or idea to its practical application is not always carried out in the same way by all the subjects.2

Figure 1. Aphrodite Cnidus (inv. 8619). (Bernardes Ribeiro, 2015). Palazzo Altemps – Rome.

(A2) There is an important second factor, and it is the transformation from the aisthesis to the askesis, from aesthetics to the discourse, produced mainly during the vanguards. This change implies that art might no longer necessarily be linked to aesthetics and its categories, but that needs a legitimator discourse, and this gave rise to the ‘philosophy of art’ as a field not necessarily linked to aesthetics (Michaud, 2009; Hegel, [1826] 2006; Danto, 1964).

(B) Previously, some of the interpretative frameworks to approach art had focused their attention on the artist’s intention (intentionalism), his resemblance to nature (mimesis) or some sort of essentialism — often closely linked to theological positions (Gilbert and Kuhn, 1972; Tatarkiewicz et al., 2005; Tatarkiewicz, 1980).

However, in cases of current art these are no longer (or not necessarily) the criteria used to discover whether something is art or not. In fact, a visit to any contemporary art museum shows few objects whose link with nature is trustworthy. It is easy to find, as well, works constituted with one intention but which have been exalted by completely different reasons (Preuss, 2018; EFE, 2008). Since the objective of this text is not to analyze the ontology of art, we will say that if none of these paradigms is still being used nowadays, it is mainly due to two reasons: (B1) The first one is the cultural changes. If art is a human product, it seems logical to infer that with cultural and social changes, its practices and approaches also change (Wolff, 1993). (B2) The second reason would be the own internal inconsistencies of these paradigms and theoretical frameworks (Meheus, 2002; Vickers, 2014).

Figure 2. Pasiteles School. Orestes and Pylades (aprox. 10 B.C.). Source: El Prado Museum.

Figure 3. Yonatan Vinitsky. New New Yask Over (Blue) Source: Tel Aviv Museum of Art. (2011).

(C) Even with all these problems, it could be thought that maybe language allow us to obtain a more reliable and generic knowledge about what art is. Unfortunately, language does not seem to be an effective method neither. Again, for two main reasons: (C1) The first one is the existence of dictionaries. These are expected to fulfill two basic functions: normative and descriptive. However, a review of the dictionary in search of the word ‘art’ shows a clear difference between what there is defined and what in our culture we refer as art.3 This implies that the dictionary does not accurately reflect the use of our language, and therefore does not satisfy its normative part either. In many cases, the dictionary description reflects conditions of possibility, but not of necessity. Therefore, it cannot be taken as a real definition. It cannot since a real definition should be:

A statement about the essential properties of the object that the ‘definiendum’ refers to. The real definitions are, thus statements about the nature of a phenomenon. As such, they require empirical validity and they can be false, insofar as our ideas about the object turn out to be wrong (Álvarez Bautista, 1983, p.135).

A definition which only reflects conditions of possibility. However, cannot “sufficiently characterize a notion to delimit it and separate it from others” (Sacristán, 1973, pp.275-276; Renate et al., 1975, p.22).

(C2) Second, and clearly related to the first, most subjective explanations of what an individual considers to be art are partial definitions, and therefore, imperfect, and inaccurate. Some of these definitions are “art is what transmits emotion” or “art is a form of expression” (Levinson et al., 2003). However, not everything that conveys emotion or not all forms of expression are called art, even by those same subjects who provide these explanations.

(D) Due to all these problems and uncertainty, I would like to specify the theoretical framework that will be used to present and develop our case study, as well as the conclusions derived from it: the Institutional Theory of Art. (Danto, 1964; Dickie, 1974; Becker, [1982] 2008).

(D1) In accordance with this Institutional Theory, I will consider something to be ‘art’ when it is found within an ‘art world’. This art world could be described as:

The complex formed by artists, gallery owners, museums, collectors, foundations, art critics, some magazines and other media, and some educational institutions. Some political institutions and some patrons that have social practices such as producing works of art, selling them, buying them, appraising them, collecting them, exhibiting them, writing about them, defending them, attacking them, enjoying them, being fascinated and obsessed with them (Vilar Roca, 2005, p.80).

However, it is important to keep in mind something already noticed by Dickie, and that is the fact that:

The set of institutions that make up an art world — artists, fine arts schools, galleries, collectors, museums, magazines, critics, auction houses, historians, experts, etc. — constitutes the necessary institutional framework for the existence of art but in no way explains enough what art is and what it does”.4 (Dickie, [1984] 2005, p.26)

(D2) In this way, we will not obtain any knowledge about what art is, but about when is something referred as art. Consequently, from now on, in this text we will work with a pragmatic and referential notion of art. Art will be a category attributed (on many occasions by adding the preposition ‘of’ and the noun ’art’) to certain things at a certain time and place, by certain but significant subjects (Danto, [1981] 2002).

(E) According to Vilar’s definition, it seems incontestable that the art market is a part of this art world.5

We could say that, if the art world is a social system and that, like every social system, it has its agents, mechanisms and motivations, the art market is, with its corresponding ones, a subgroup of this macrosystem.6 The art market, however, has a negative point, and a positive one, which seems relevant to this text.

(E1) The negative side is that the art market is a market with information problems, and therefore it is not a perfect market. Some of the information problems stem precisely from the lack of a clear and precise knowledge and definition of what art is, as well as objective assessment criteria. This is a problem that is transferred to other subgroups in the art world, such as its legislation (Danziger and Danziger, 2014). Another problem is the complex relationships between agents in this context of market uncertainty, which means that on many occasions certain problems are not made public just to do not alter the social order7 (Day, 2014).

(E2) The advantage that the market provides us in this case is that it allows us to observe, through a “conventional common measure [that] refers to everything and with which everything is measured”, (Aristotle, 2014, p.245) what a group of specific subjects refers to as art. This measure is the money, which allows the allocation of resources within human communities thanks to the fact that it is countable, transportable, easy to accumulate and convertible (Frank and Bernanke, 2007, p.684; Hayter and Patchell, [2011] 2016, p.22; Stigler, 1984). It is important to reiterate that the art market provides us with a referential, pragmatic, and attitudinal knowledge, and not necessarily ontological.

However, it is useful to observe some of the results of these interactions between agents that, through this mechanism that is the art market, are currently taking place.

A market of diversified stars

(A) In this framework, a representative amount of art market agents that have sufficient economic resources choose to act in an expansionist way (Sklar, 1976; Baumol, 1962; Kotler and Kotler, [1998] 2001, pp.103-104; Balfe, 1987). Traditionally, and even nowadays, this expansionism has been done through two ways: geographically and/or diversifying their activities.

(A1) The two agents that have traditionally expanded more geographically have been auction houses and art galleries. Logically, this does not mean that all of them has had the same success. Clear examples are those of auction houses such as Christie’s, Sotheby’s, or Phillips, who hold public auctions in cities such as London, New York, or Hong Kong. These houses have representative offices in almost any city with a certain relevance to the art market. In relation to art galleries, those gigantic agents such as Gagosian (18 spaces, from Basel to Beverly Hills), Pace Gallery (from Geneva to Seoul), Hauser & Wirth (from Los Angeles to Zurich) or Opera Gallery (18 spaces, from Dubai to Monaco), are also present in almost any significative city.8

This geographic expansion, however, is not currently limited to auction houses or art galleries since art museums or art fairs have adopted this practice as well. Between museums, some names could be the Guggenheim, the Pompidou, the Hermitage, the Louvre or the Thyssen-Bornemisza. Among the art fairs, Art Basel (in Basel, Hong Kong, and Miami), Frieze (in London and New York) or Scope Art Show (also in Basel, Hong Kong, and Miami) (EFE, 2017; Piquer, 2001; Bohlen, 2001; Kinsella, 2019; Hermoso, 2015).

(A2) As we have stated, however, this expansionary process can also take place through diversification. Auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s have their own schools, museums typically offer training courses, and art galleries such as Sean Kelly or Zwirner offer podcasts. In fact, Zwirner has its own publishing house, which does not publish only catalogs from his artists and exhibitions, but about topics on art in general. Hauser & Wirth has also different bookstores.

These are just a few examples of how a few agents play a big role in the art market. We could start an analysis on whether this predominant role is because for some reason buyers, in a market context, have given them this power through the system of manifestation of preferences that is money or if it is precisely this greater presence what determines consumer attitudes. However, this is not the objective of this article, and this suggestion is presented here in case someone is interested in carrying research about it in the future.

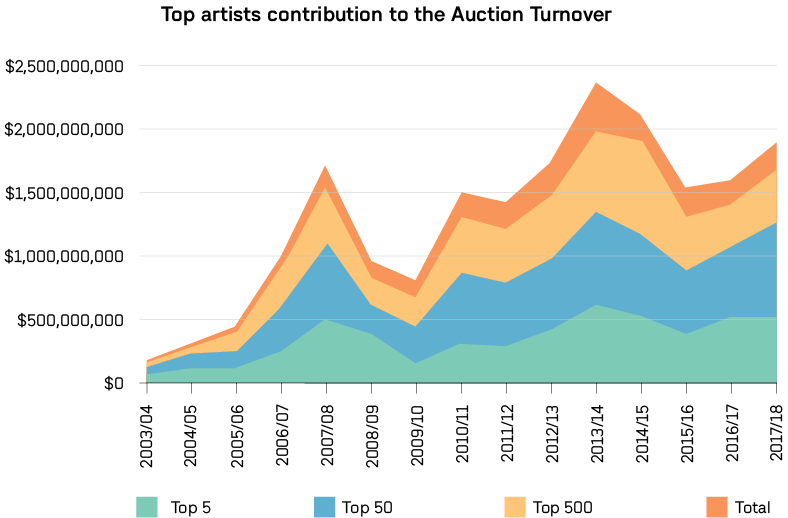

(B) Independently of that, what recent studies show is how unequal the art market is, being almost a market in which the winner takes the entire market.

(B1) In fact, according to ArtPrice, in 2018

Figure 4. Advertisement of the podcasts provided by Sean Kelly Gallery in Artnews. Source: Sean Kelly Gallery.

The financial power of the Contemporary Art Market [was] focused on a relatively small elite of artists in a much larger pool: 89% of the segment’s global turnover is generated by its 500 most successful artists in an overall pool of 20,335 Contemporary artists who sold at least one work via auction between end-June 2017 and end-June 2018. The leading trio—Basquiat, Doig and Stingel—alone accounted for 22% of the segment’s global turnover (ArtPrice, 2019).

There was no significative change in 2019 (ArtPrice, 2020).

To analyze this data, it is necessary to take in consideration the number of individuals who did not manage to be presented at auction, or who, once there, did not manage to be sold. It would also be interesting to know how many were purchased by their own dealers, although the data gives a rough idea of the inequality of the situation. This fact, however, does not only apply to artists, but also to organizations. A study made by Fraiberger and his colleagues demonstrates the importance for an artist to start his career in one of those great organizations previously referred to. According to their study, museums such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim, the Tate, the Pompidou Center, or the Gagosian Galleries, for example, would be in the center of their map of influence (Fraiberger et al., 2019; Wickham et al., 2020; NEA, 2016). The study confirmed that only 14% of the artists that are not in the main organizations of influence remain active after ten years; also, that if one of the first five exhibitions as an artist takes place in one of the central galleries, the percentage of risk of ending up in the edges of the mapping is only 0.2%.

Graphic 1. Market share for artists. Source: The Contemporary Art Market Report (ArtPrice, 2018).

It makes sense since, according to Rascón Castro:

Artists distribute their time in a dual labor market (artistic/non-artistic), selling their products in another dual market (physical goods market/ideas market). Artists are often engaged in part-time or defined short-term jobs so that they can spend the rest of their time working on their artistic creation. Having two or more jobs, paid or unpaid, is called moonlighting. That is, creative agents can be teachers, consultants, waiters or all options at the same time, in addition to artists. [...] Unfortunately, moonlighting seldom provides constant and stable incomes, so artists risk-averse may decide to engage in a traditional forty-hour job per week9 (Rascón Castro, 2009, pp.29-30; Abbing, 2002).

(B2) Also, an important part of middle and low category art galleries are supported mainly by the income generated by one single artist, which greatly increases the risk for that business of being economically viable. This is precisely what makes many of them unable to sustain themselves over time, and less so when the economic context is not favorable (Solimano and Solimano, 2020; Solimano, 2019; Öztürkkal and Togan-Eğrican, 2019; Worthington and Higgs, 2004).

For example, some reports from the National Endowment for the Arts showed a decline for job artists during the economic crisis of 2008 (NEA, 2009; NEA, 2010; NEA, 2011). Considering that the same Bureau found the artist’s average income 6% lower than the average of the active population’s, it shows the high chances both for artists and organizations different than those huge ones to end up outside of this art market system (NEA, 2019). Although it is too early to make solid statements, it seems that with the current coronavirus crisis, the consequences (or one small part of them) will be the same in all significative geographic markets (Art+, 2020; McAndrew et al., 2020).

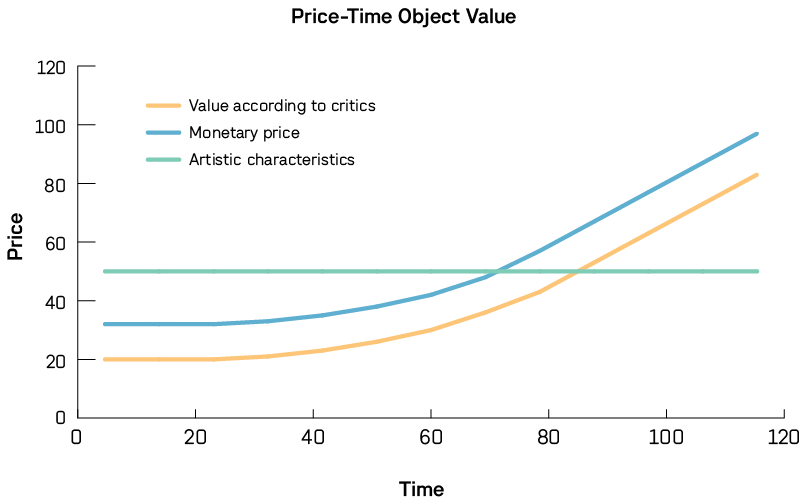

(C) Consequently, these gigantic companies not only have a large geographical presence and diversified activities, but also serve as a synonym for risk reduction.

This argument comes into place because, if there are no clear criteria on what art is or its constitutive intrinsic characteristics, it is impossible to establish by knowledge or recognition a judgment and a classification of a qualitative nature. To make such a qualitative judgment, it is necessary to know how to identify relevant similarities or differences to make a comparative analysis (Ragin, [1987] 2014, pp.1-18). Since this is not possible, the issue of uncertainty does not disappear, but the risk can be minimized by choosing in the market those agents and organizations located in a higher hierarchical position (Roselius, 1971; Fraiberger et al., 2018; Brandellero and Velthuis, 2018).

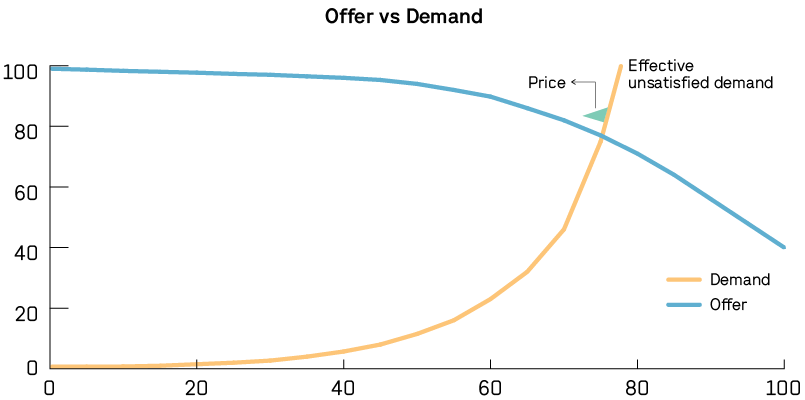

Graphic 2. Relation between artistic characteristics, value and price. Based on (Rascón Castro, 2009)

Louisa Buck, for example, interestingly described how:

You [can] pay a grand for a painting from an unknown artist’s studio. If you are a serious collector, taking a risk, you increase the value of the work just by buying it. If you are a cheap serious collector you try to get a discount on this ... if you wait until the artist has a dealer you are going to pay more. If you wait until he has a good review then you are going to pay more still. If you wait until ... MOCA notices his work you are going to pay even more than that, and if you wait until everybody wants one, of course, you are going to pay a whole hell of a lot more, since as demand approaches ‘one’ and supply approaches ‘zero’, price approaches infinity. But you are not paying for art. You are paying to be sure, and assurance (or insurance, if you will) is very expensive, because risk is everything for everybody, in the domain of art (Buck, 2004, p.14).

This does not only translate into a market in which the winner takes almost the entire market, but turns the art market, as well, into a market of superstars. In this kind of market, “small numbers of people earn enormous amounts of money and dominate the activities in which they engage” (Rosen, 1981, p.845). Although, as we saw, this cannot be a consequence of a preference based on knowledge, but on risk minimization (Adler, 1985; Quemin, 2013). This seems to be coherent with one of the typical characteristics that allow this kind of market of superstars to exist: the “imperfect substitution among quality differentiated goods in the same product class” (Rosen, 1981, p.846; Adler, 1985).

(D) At this point and as a partial conclusion before going into our case study, it is important to highlight an element that seems obvious. The context presented here implies that, the relative reduction of agents participating significantly in the art market entails that the quantity of money present in the art market is concentrated in fewer hands, something happening every time that an agent leaves this commercial system.10

Graphic 3. Representation of the high price due to the increase in demand and the decrease in supply. Based on (Rascón Castro, 2009)

Case study: Almeida & Dale

The case study that we will analyze in this text is that of the Brazilian agents Antonio Almeida and Carlos Dale Junior. It is important to express that the vast majority of descriptive information provided here has been published by Gabriela Longman at the prestigious journal Folha de S.Paulo. To contrast the information, the gallery also contributed with its version.

In turn, I would like to thank all the clarifications and specifications that Gabriela Longman and Gabriela Schmatz has made each time I have consulted them while preparing this article. As a person of great knowledge in the field of the art market of São Paulo, they have been of great value.

Antonio Almeida and Carlos Dale are the key people of this case study. They are both the gallery owners at Almeida e Dale Galeria de Arte, located in the city of São Paulo, in the Jardim Paulista neighborhood.

(A) As Longman describes, “Antonio Almeida and Carlos Dale have spent the last few years injecting capital, creating partnerships and forming an extensive network of galleries”11 (Longman, 2019a).

(A1) The peculiarity is that these “capital injections” are intended to merger other galleries, and more specifically, galleries that already have a certain commercial success. Some of those mergers are, for example, with galeria Leme, creating Leme/AD. According to the information provided by Longman, another foreseeable merger is with the galeria Millan (Longman, 2019a).

(A2) Beyond the mergers, Almeida and Dale also operate through partial acquisitions. Examples could be publishing houses as with Capirava. According to the information provided by Longman, Almeida and Dale even created a travel agency with an art office on top12 (Longman, 2019a).

(A3) Both gallery owners carried out other practices and partnerships that did not involve direct purchasing, such as associating with other galleries (as Marilia Razuk) to have access to prestigious international art fairs or the rental of spaces in different national museums to exhibit their works. These practices, however, need a certain injection of capital, but are more common in the sector.

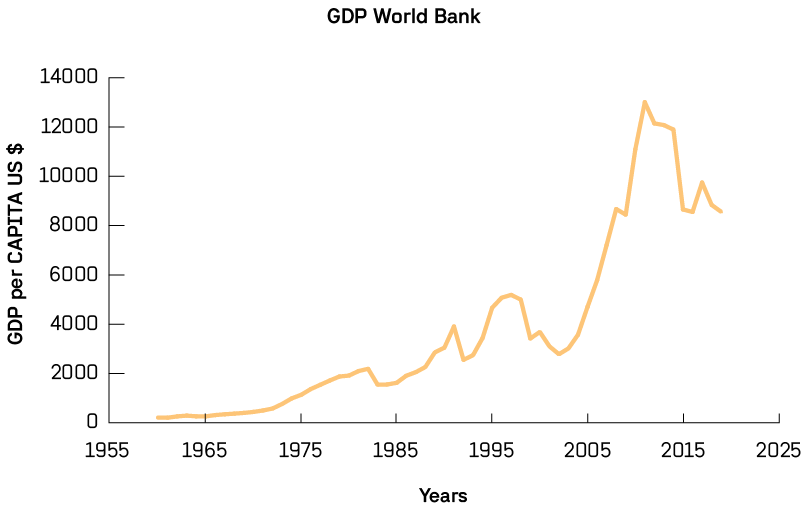

Graphic 5. Brazilian GDP x Capita according to data provided by the World Bank. Own creation.

Currently, both gallery owners are being investigated for money laundering, but the investigations are still ongoing, and this has nothing to do with the objective of this research (Longman, 2019b). Being asked about this question, the Manager from the gallery expressed that the company has nothing to do with these illegal activities.

Inequality in Brazil, a condition of necessity

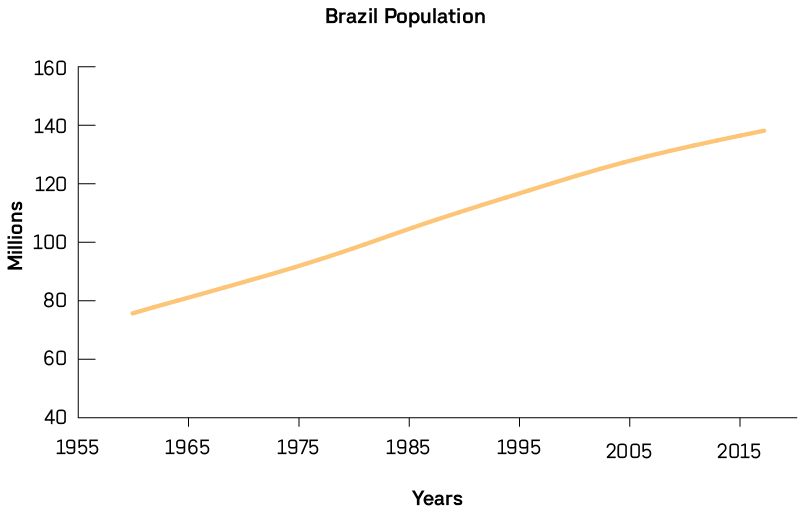

(A) Although this is not an article regarding social justice or any kind of moralism, it is important to carry out a brief analysis of the economic inequalities, that occur in Brazil13(RNSP, 2019; Canzian et al., 2019). This Latin American country is, in general terms, a country whose population has not stopped growing in recent decades. In fact, data from the World Bank details the way in which, in 1960, the Portuguese-speaking country had a population of 72.179.226 people, while in the year 2019 it had 211.049.527 (WB, 2020). The country’s GDP per capita, in general, has also experienced slight increases and some declines, but there is a key moment in which the country’s GDP per capita increases dramatically. This increase is observed, always following the World Bank data, from 2002, when the GDP per capita was of 507.952 billion of USD. Since then, and apart from a minuscule decrease between 2008 and 2009, the country’s GDP per capita increases until 2.612 trillion USD in 201114 (WB, 2020).

In the following years, that indicator falls slightly, but there is a moment when the fall is catastrophic: from 2014 to 2015. That year, GDP per capita fell from 2.456 trillion USD to 1.802 (-68.88%). Casually, Almeida and Dale opened their gallery in 2002, the year where the spectacular economic growth of Brazil was starting.

Currently (2019), Brazil’s GDP per capita is 1.84 trillion USD, just a bit higher than it was in 2009, but still far away from its highest mark.

However, to understand these data it is important to specify some elements.

(A1) The first is the election of the country for the 2014 Football World Cup and, secondly, the election of Rio de Janeiro for the 2016 Olympic Games.

In 2004, the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) reported that a Latin American country would be hosting this competition in 2014, with only Brazil and Colombia being the candidates, and Colombia withdrawing from the bid (FIFA, 2003; Caracol Radio, 2007). Brazil, logically ended up being the host, as subsequently confirmed. This is one reason for Brazil’s economic growth, which started in 2002, but had this stimulus in 2004 as a key element.

Graphic 4. Brazilian population according to data from the World Bank. Own creation.

This would also explain the subsequent decrease, between 2014 and 2015, in something that is quite typical of the economy of the Football World Cups (Zimbalist, 2015; Allmers and Maennig, 2009).

In 2009, the International Olympic Committee decided to name Rio de Janeiro — the traditional capital of the country — as the host for the 2016 Olympic Games (Zimbalist, 2017; Zimbalist, 2015; Baade and Matheson, 2016; Rose and Spiegel, 2011).

This choice would explain, at least partially, the rise in GDP per capita after the slight drop in 2008, being an extra stimulus for the country’s economy. In turn, it would explain the rebound between 2016 and 2017, the only one in Brazil since the end of the Football World Cup.

Predictably, there are other factors that give rise to these data, but without any doubt, these two international events were a great stimulus and, observing the periodic data, their influence on the country’s general economy is easily observable.

(A2) Although a great connoisseur of the Art Market such as Olav Velthuis expressed in 2016 that the Brazilian art market would not succumb to the most serious economic crisis in the history of the country, it seems that today it is already possible to say that he was wrong, or at least, partially wrong (Velthuis, 2016).

The main gallery owners in São Paulo and, therefore, in the country, affirmed that their sales had fallen between 50% and 30%, the state eliminated the Rouanet Law that allowed private companies to collaborate with public art institutions in exchange for tax exemption and, in low and middle level agents, the shock and disappearance were even more evident (Angeleti, 2019; FGV-DAPP, 2017). In fact, this is one of the reasons why agents and organizations in a superior hierarchical position decided to act in a World-Economy basis rather than in a State-National environment, precisely looking for individuals from contexts with better economic prosperity and avoiding the burden of high national taxes15 (Bevins, 2014; Wallerstein, 2011; Martí, 2019).

Figure 5. Paraisópolis. (Vieira, 2004). Courtesy of the artist.

(A3) In addition to what is expressed here, it is very important to understand that Brazil is a country with enormous income inequalities. This is true even though the Latin American country “has lifted 28 million people out of poverty in the last 15 years, reducing poverty to less than 10 percent of the population”, according to Oxfam (Oxfam, 2017; Madeiros, 2016). The studies indicate, in turn, that inequality decreased between 2000 and 2014, precisely the years of greatest economic growth in the country (Neri, 2019). The typical economic inequality in Brazil, however, increased again from 2015 and became, in 2018, the highest since 2012 (Neri, 2019; Biller, 2019; Madeiros, 2016).

Furthermore, Brazil is a Federal Republic, so there are great inequalities between states as well. In any data provided by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, the Institute of Applied Economics Research, the Foundation Firjan and others, it is always shown significative differences between the quality of life of the different states. Maranhão, Amapá or Alagoas, for example, have an inferior situation compared to other states like Santa Catarina, Rio Grande do Sul or São Paulo (Souza, 2015; Aldrin Silva, 2018).

São Paulo is taken usually as the referent by its educational system, in terms of population, as a city where to do business and as a cultural state and city.16 In fact, it has the 60% of the total galleries of the country. Rio de Janeiro, de second State with more galleries, only have the 24% (Latitude et al., 2018: 10; Fleming, 2018).

This fact does not mean, that there are no inequalities within the same state and the same city of São Paulo. Two data can easily help confirm this fact: in the city of São Paulo, people living in poor zones, has a life expectancy of approximately 23 years less than the subjects living in the wealthy neighborhoods. Also, despite being the richest state, 30 percent of people live in poverty or extreme poverty (RNSP, 2019).

This photo taken by the artist Tuca Vieira illustrates the inequality between two adjacent neighborhoods in São Paulo: Paraisópolis (in Vila Andrade District) and Morumbi District. Ironically, Paraisópolis comes from “paradise city”, being Paraisópolis the poorest side of the photography.

In summary, we have:

1. An object and an environment of uncertainty.

2. An art world and an art market that, within its hierarchical structure, fails to solve the problem of uncertainty, but it does minimize the risk.

3. An art market with huge income differences and a small number of key agents.

4. Some key agents which expand their influence geographically and through diversification.

5. The case of two gallery owners who act through mergers and acquisitions.

6. This in a country currently in recession after decades of great growth.

7.And in a country and a city with huge economic inequality.

Mergers & Acquisitions: its advantages

As a philosopher by training, I have a somewhat strange hobby, which is to look in the classical culture for translations, references or elements that can easily be applied to current events.

(A) It is precisely in this sense that the Latin phrase: De pane lucrando seems to me of great interest here.

According to the main dictionary of the Spanish language, this phrase is described as: “to do artistic or literary works: With the priority purpose of earning a living”.

As we have said, a few artists concentrate almost the entire market contrary to many others, who never get to be sold in auction or who never get to be part of the key means of distribution of the art market (Fraiberger et al., 2019; ArtPrice, 2019, p.20).

In an environment of uncertainty and poorly defined practices, the artist must provide an innovation that the client finds of interest and, his dealer, profitable (Wilson and Stokes, 2005).

Regardless of what type of elements are most attractive, it seems logical that once a given artist achieves an innovation that is recognized, accepted and profitable, he exploits it with the aim of:

Being easily recognized, as if it were his brand product.

Receive as much money as possible for his work.

This does not mean, obviously, that an artist cannot use his time to create works for his own pleasure, to experiment or, simply, to look for new innovations that are also profitable.17

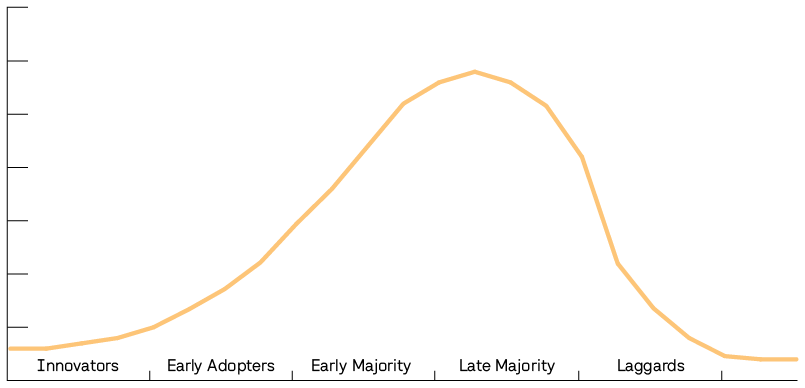

However, this seems much easier to do if an agent has a certain recognition that provides income on a more regular basis because, as we have expressed, otherwise it is statistically likely to end up outside the art market. Some artists may simply disagree with this practice and decide to leave the market. Leaving the market, when done by choice, is also a way of communicating (Herbert, 2016). On the other hand, it is important to keep the production number in quantities that prevent the saturation of supply in the market, since in that case, there would be a perfect market equilibrium and the recognition and demand would not necessarily imply a greater benefit or prestige.18

However, for an artist and his artistic innovations to get a certain demand, there are several key factors needed, but one of them is time. For a buyer or a dealer, an artistic innovation with already a significant acceptation and demand is synonymous of less risk.

This is precisely the main advantage that the merger and acquisition system carried out by Almeida and Dale entails.

(B) While the two gallery owners acquire rival galleries, what they are doing is acting at a time when the risk is already less, thus minimizing the risk they incur.

In this way, Almeida and Dale do not deal with the moment in which an artist innovates and has its first supporters — if he ever has them, but directly, allows them to work with artists and products that are already in demand and whose products are recognizable.

(C) The economic inequality that we have presented in this text is a key factor that makes this expansionist system possible. This is because buying galleries that already have a certain reputation or those artists from a specific gallery that are especially successful, has a higher cost. It has a higher cost because, as we said previously, quoting Louisa Buck, “risk is everything for everybody, in the domain of art” (Buck, 2004, p.14).

Graphic 6. Acceptance of innovations. Own creation based on Everett M. Rogers work and his book Diffusion of Innovations.

Consequently, many galleries initially adopt a significant risk. This risk is based on selecting certain artists who produce something of potential future interest to a target customer. On many occasions, what the artist produces is not of interest, and even the processes of representation and dissemination of the artist’s work in search of a subsequent acceptance entail high costs, both economic and in time for its dealer.19

In private conversation, Georgina Adam, the columnist for art market at the Financial Times and Editor of The Art Newspaper, confessed that one of the big concerns she sees in gallery owners is that most artists act with little loyalty and are constantly looking for a gallery or market agent who is in a superior position to represent them.20 They believe that this leap will give them greater prestige and, in turn, will also reduce the risk they have as artists.

In a society (that of Brazil and São Paulo) in which inequality and economic recession can make some less gigantic galleries prefer cash rather than keep their business, or in which the leave (through money) of a single artist’s production can entail the almost total loss of profits, the environment for this merger and acquisition to take place is ideal.

Also, Almeida and Dale’s rental of spaces in museums to present their artists is also an investment in both the gallery and its represented artists, since by increasing their visibility and prestige, a return of that investment is expected through subsequent sales.21

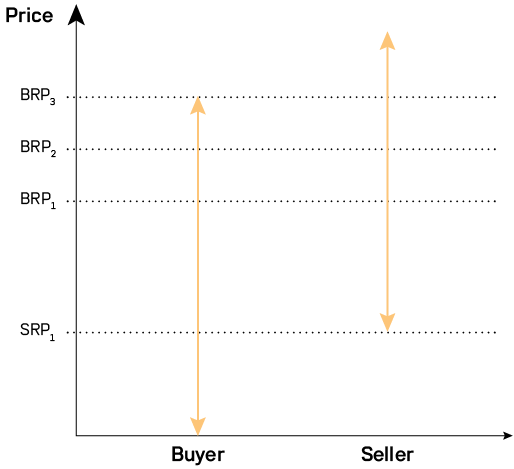

In a less unequal market and environment, without information problems or in a context without economic recession — to give just a few examples, this practice would hardly be possible since acquisition and merger costs would be predictably higher than the potential return of the investment. This is predictably true since the price paid should be higher to satisfy an estimate seller’s reservation price.

After asking some agents of the Brazilian art market what is the way in which this expansion materializes, all of them have agreed that there is not a clear direction or patron. In consequence, both gallerists acquire a positive balance sheet, cash flow and the resources and relationships to act at a bigger scale based on market opportunities when they are identified as such.

Graphic 7. Comparison between the Buyer’s Reservation Price and the Seller’s Reservation Price. Own creation.

This is also what allows them to act internationally, minimizing the factor that during an economic recession, a certain number of buyers may decide not to dedicate their monetary resources to art22 (Rojas, 2018; Martí, 2019).

In turn, some reference to Almeida and Dale is always present, as we saw in the case of the new Leme/AD, keeping the name, the branding, and its symbolic meanings (Jacoby et al., 1971).

Conclusions

In this article we have presented the case study of the two gallery owners based in São Paulo Antonio Almeida and Carlos Dale Junior.

As we have stated, these two gallery owners began their activity in a period of enormous economic growth in Brazil, a growth that, in part, was due to two specific events: the Olympic Games and the Football World Cup.

Following the economic recession in Brazil since 2016, one of the sectors that were also affected was the art market, especially due to its status as a market of superstars and in which a few agents dominate almost the entire market.

Although some of these agents expand their role through diversification or through presence in new geographic locations, Almeida and Dale’s main contribution is the fact that they are expanding their business through mergers and acquisitions.

This expansion system seems a great form of risk management in a market with implicit uncertainty as is the art market. The reason is that trough these practices, Almeida and Dale manage to act at a more advanced temporal level, when an artist’s innovations have already been accepted and have a stablished demand.

In this way, although these mergers and acquisitions require a certain quantity of money, the two gallery owners avoid all the temporary and economic costs necessary to make an innovation being accepted.

Funding: This research was funded by the Chinese Scholarship Council thanks to a Chinese Government Scholarship - Senior Scholar and a Mobility Scholarship Between Associated Institutions provided by the Spanish American Association of Graduate Universities.

Acknowledgments: I must thank Dr. Titus Levi from the University of Southern California - Shanghai Jiao Tong University for his insights into the Economics of Culture. I must thank Dr. Taisa Helena Pascale Palhares as well, from UNICAMP, for having let me know of Almeida & Dale. Finally, I want to thank Gabriela Longman (contributor at Folha de S.Paulo) and Erica Schmatz (Manager at Almeida e Dale) for their help and clarifications. To finish, I would like to thank Tuca Vieira for letting me use his picture and Georgina Adam for his attentive e-mails.

References

Abbing, H. (2002). Why are artists poor? The exceptional economy of the arts. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Adler, M. (1985). Stardom and Talent. The American Economic Review, 75(1), 208–212.

Aldrin Silva, R. (2018). “Desigualdade de renda cresce em quinze estados brasileiros”. Fundação Perseu Abramo.https://tinyurl.com/kd72ddh

Allmers, S., and Maennig, W. (2009). Economic Impacts of the FIFA Soccer World Cups in France 1998, Germany 2006, and Outlook for South Africa 2010. Eastern Economic Journal, 35(4), 500–519.

Álvarez Bautista, J. R. (1983). El valor de las definiciones. Contextos, 1, 129–154.

Angeleti, G. (2019). “Brazil’s museums dodge Bolsanaro’s cultural funding caps—at least for now”. The Art Newspaper. https://tinyurl.com/cy687dzn

Aristotle. (1996). Poetics. New York: Penguin Books.

Aristotle. (2014). Ética a Nicómaco. Madrid: Gredos.

Art+. (2020). “Survey Results: Impact of New Coronavirus Pneumonia Outbreak on the Chinese Art World”. Art Market Journal. https://tinyurl.com/22h39yzm

ArtPrice. (2019). The Contemporay Art Market Report 2018. Paris: ArtPrice.

ArtPrice. (2020). The Contemporay Art Market Report 2019. Paris: ArtPrice.

Baade, R. A. and Matheson, V. A. (2016). Going for the Gold: The Economics of the Olympics. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(2), 201–218.

Balfe, J. H. (1987). Artworks as symbols in international politics. International Journal of Politics,Culture and Society, 1(2), 195–217.

Baumol, W. J. (1962). On the Theory of Expansion of the Firm. The American Economic Review, 52(5), 1078–1087.

Becker, H. S. (2008). Art worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bermúdez, J. L. (2002). Art and morality. New York: Routledge.

Bevins, V. (2014). “Market Forces”. ArtReview, July 21, 2014. https://tinyurl.com/pt4yvhr6

Biller, D. (2019). “Brazil’s income inequality hits highest since at least 2012”. abc News. https://tinyurl.com/jcummn2h

Bohlen, C. (2001). “Guggenheims and the Hermitage Bust Open Vegas”. The New York Times, October 13, 2001. https://tinyurl.com/3wxp5ywz

Bourdieu, P. (1988). La distinción: criterios y bases sociales del gusto. Madrid: Taurus.

Brandellero, A., and Velthuis, O. (2018). Reviewing art from the periphery. A comparative analysis of reviews of Brazilian art exhibitions in the press. Poetics, 71, 55–70.

Buchli, V., et al. (2001). The material culture reader. New York: Berg.

Buck, L. (2004). Market matters: the dynamics of the contemporary art market. London: Arts Council England.

Cahn, S. M. (2008). Aesthetics: a comprehensive anthology. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Canzian, F., et al. (2019). “Los súper ricos en Brasil lideran la concentración de la renta global”. Folha de S. Paulo. https://tinyurl.com/2j942rd4

Caracol Radio. (2007). “Colombia renuncia a su postulación para el Mundial de Fútbol 2014”. Caracol Radio. https://tinyurl.com/fsysjsw

Castiñeiras, M. A. (2008). Introducción al método iconográfico. Barcelona: Ariel.

Danto, A. C. (1964). The Artworld. The Journal of Philosophy, 61(19), 571–584.

Danto, A. C. (2002). La transfiguración del lugar común: una filosofía del arte. Barcelona: Paidós.

Danziger, C., and Danziger, T. (2014) “On the Case: Exploring Real World Art Law Issues”. Artnet. https://tinyurl.com/je44r268

Day, G. (2014). Explaining the Art Market’s Thefts, Frauds, and Forgeries (And Why the Art Market Does Not Seem to Care). VanderbiltJournal of Entertainment & Technology Law, 16(3), 457–495.

Dickie, G. (1974). Art and the aesthetic: an institutional analysis. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Dickie, G. (2005). El círculo del arte: una teoría del arte. Barcelona: Paidós.

Eco, U. (2010). History of beauty. New York: Rizzoli.

EFE. (2017). “El Louvre abre sucursal en Abu Dhabi por 1.000 millones de euros”. El Español.https://tinyurl.com/pkcfyyjb

EFE. (2008). “Un Banksy a precio de oro”. El País.https://tinyurl.com/ynunadk7

FGV-DAPP. (2007). “Rouanet Law funds falling since 2010”. FGV-DAPP.https://tinyurl.com/4h9prxn3

FIFA. (2003). “2014 FIFA World Cup TM to be held in South America”. FIFA.https://tinyurl.com/5hz68hr9

Fleming, T. (2018). The Brazilian Creative Economy. London: British Council.

Peñuela, J. (2007). Pensar en Platón: la problemática de lo bello contemporáneo. Calle 14: Revista de investigación en el campo del arte, 1(1), 111–126.

Fraiberger, S. P., et al. (2018). Quantifying reputation and success in art. Science, 362(6416), 825–829.

Frank, R. H., and Bernanke, B. (2007). Principles of economics. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Frey, B. S. (2000). L’Economia de l’art. Barcelona: La Caixa Servei d’Estudis.

Gilbert, K., and Kuhn H. (1972). A History of Esthetics. New York: Dover Publications.

Harillo Pla, A. (2018). Primavera en las galerías de arte de Shanghái. Calle 14: Revista De investigación En El Campo Del Arte, 13(24), 438-449.

Harillo Pla, A. (2016). Arte en el DRAE. Entre significado y referencia. Eikasia: revista de filosofía, 68, 265–290.

Harillo Pla, A. (2017). El arte en España: una crítica a su legislación. ArtyHum: Revista de Artes y Humanidades, 32, 20–40.

Arillo Pla, A. (2019). An insight into the artistic institutional globalization. Paper presented at Annual International Scientific Conference. Art and Art History at the Present Stage. Cultural Interaction and Globalization, Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts, Saint Petersburg, 2019.

Hayter, R., and Patchell, J. (2016). Economic geography: an institutional approach. Don Mills: Oxford University Press.

Hegel, G. W. (2006). Filosofía del arte o estética. Madrid: Abada Editores.

Hendrix, J. S. (2005). Aesthetics & the philosophy of spirit: from Plotinus to Schelling and Hegel. New York: Peter Lang.

Herbert, M. (2016). Tell them I said no. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Hermoso, B. (2015) “El Pompidou fondea en Málaga”. El País. https://tinyurl.com/k73fjyp5

Hicks, D., et al. (2010). The Oxford handbook of material culture studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hume, D. (2013). Of the standard of taste. Birmingham: Birmingham Free Press.

Hyman, J. (2002). Is the Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder. Think, 1(1), 81–92.

Jacoby, J., et al. (1971). Price, brand name, and product composition characteristics as determinants of perceived quality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 55(6), 570–579.

Kant, I. (2008). Critique of judgement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kinsella, E. (2019). “No Lease? No Problem! This Company Wants to Bring Your Gallery to Cities Around the World”. Artnet. https://tinyurl.com/tjufbjcc

Kotler, N. G., and Kotler, P. (2001). Estrategias y marketing de museos. Barcelona: Ariel.

Latitude, et al. (2018). Sector Report: The Contemporary Art Market in Brazil. São Paulo: Associação Brasileira de Arte Contemporânea.

Layton, R. (1991). The anthropology of art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levinson, J., et al. (2003). The Oxford handbook of material culture studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Longman, G. (2019a) “As Brazil turns a corner, will local market follow?”. Folha de S.Paulo. https://tinyurl.com/y3b8b5we

Longman, G. (2019b) “Galeria Almeida & Dale é investigada pela Lava Jato por lavagem de dinheiro”. Folha de S.Paulo. https://tinyurl.com/34ajcxun

Machamer, P. K., and Roberts, G. W. (1968). Art and Morality. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 26(4), 515–519.

Madeiros, M. (2016). World social science report 2016: challenging inequalities, pathways to a just world. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

Martí, S. (2019). “Galerias brasileiras vão à meca dos bilionários para fugir da bancarrota”. Folha de S.Paulo.https://tinyurl.com/29eratcy

McAndrew, C., et al. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 on the art market. Paper presented at Art Basel Conversations, online, 2020.

Meheus, J. (2002). A history of six ideas: an essay in aesthetics. Dordrecht: Springer.

Michaud, Y. (2009). Filosofía del arte y estética. Disturbis 6: w/p.

Morgan, R. C. (1998). The end of the art world. New York: Allworth Press.

NEA. (2009). “Artists in a Year of Recession: Impact on Jobs in 2008”. NEA Research Bulletin, 97, 1-10.

NEA. (2010). “Artist Unemployment Rates for 2008 and 2009”. NEA Research Bulletin, 1-06.

NEA. (2011). “Artist Employment Projections through 2018”. NEA Research Bulletin, 103, 1-14.

NEA. (2016). Creativity connects: trends and conditions affecting U.S. artists. Washington DC: National Endowment for the Arts.

NEA. (2019). Artists and Other Cultural Workers: A Statistical Portrait. Washington DC: National Endowment for the Arts.

Neri, M. (2019). Inequality in Brazil. Inclusive growth trend of this millennium is over. UNU-WIDER 1/2019: w/p.

Neuendorf, H. (2017). “Brazil’s Art Market Isn’t Even Close to Its World-Class Potential. Here’s Why”. Artnet.https://tinyurl.com/brznazfz

Oxfam. (2017). “Brazil: extreme inequality in numbers”. Oxfam. https://tinyurl.com/hezwuzju

Öztürkkal, B., and Togan-Egrican, A. (2019). Art investment: hedging or safe haven through financial crises. Journal of Cultural Economics, 43(4), 1–49.

Piquer, I. (2001). “El Guggenheim abre dos museos en Las Vegas”. El País.https://tinyurl.com/8vj76u5j

Preuss, A. (2018). “Banksy painting ‘self-destructs’ moments after being sold for $1.4 million at auction”. CNN. https://tinyurl.com/ee9ups

Quemin, A. (2013). Les stars de l’art contemporain notoriété et consécration artistiques dans les arts visuels. Paris: CNRS éditions.

Ragin, C. C. (2014). The Comparative Method: Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies. Berkeley: Unive rsity of California Press.

Rascón Castro, C. (2009). La economía del arte. México: Nostra Ediciones.

Rede Nossa São Paulo. (2019). “Mapa da Desigualdade 2019 é lançado em São Paulo”. Rede Nossa São Paulo. https://tinyurl.com/ynfsr88nRenate, M., et al. (1975). Introducción a los métodos de la Sociología empírica. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

Rojas, L. (2018). “As Brazil turns a corner, will local market follow?”. The Art Newspaper.https://tinyurl.com/2hsvtnsx

Rose, A. K., and Spiegel, M. M. (2011). The Olympic Effect. The Economic Journal, 121(553), 652–677.

Roselius, T. (1971). Consumer Rankings of Risk Reduction Methods. Journal of Marketing, 35(1), 56–61.

Rosen, S. (1981). The Economics of Superstars. The American Economic Review, 71(5). 845–858.

Sacristán, M. (1973). Introducción a la lógica y al análisis formal. Barcelona: Ariel.

Santana Viloria, L. (2019). La feria comercial de arte como espacio de redistribución de capital simbólico. Calle 14: Revista de investigación en el campo del arte, 14(25), 72–85.

Schelling, F. W. (1989). The philosophy of art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Shiner, L. E. (2001). The invention of art: a cultural history. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Sklar, R. L. (1976). Postimperialism: A Class Analysis of Multinational Corporate Expansion. Comparative Politics, 9(1), 75–92.

Solimano, A. (2019). The Art Market at Times of Economic Turbulence and High Inequality. Paper presented at Seminar Series at the European Investment Bank, Luxembourg, 2019.

Solimano, A., and Solimano, P. (2020). Global Capitalism, Wealth Inequality and the Art Market. In Handbook of Transformative Global Studies. Edited by Hosseini, Hamed, et al. New York: Routledge.

Souza, B. (2015). “Os 10 estados com as piores taxas de desigualdade de renda”. Exame. https://tinyurl.com/m4j6eva8

Stigler, G. J. (1984). Economics: The Imperial Science?. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 86(3), 301–313.

Svašek, M. (2007). Anthropology, art and cultural production. London: Pluto Press.

Tatarkiewicz, W. (1980). A history of six ideas: an essay in aesthetics. Boston: Kluwer Boston.

Tatarkiewicz, W., et al. (2005). History of Aesthetics. New York: Continuum.

Velthuis, O. (2016). The Brazilian Art World Is Here To Stay, Economic Crisis Or Not. Paper presented at Debates: Colección Cisneros, online, 2016.

Vickers, P. (2014). Theory flexibility and inconsistency in science. Synthese, 191(13), 2891-2906.

Vilar Roca, G. (2005). Las razones del arte. Boadilla del Monte: Antonio Machado Libros.

Wallerstein, I. M. (2011). The Modern World-System I. Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wickham, M., et al. (2020). Defining the art product: a network perspective. Arts and the Market, 10(2), 83–98.

Wilson, N. C., and Stokes, D. (2005). Managing creativity and innovation: The challenge for cultural entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12(3), 366–378.

Wolff, J. (1993). The social production of art. New York: New York University Press.

Worthington, A. C., and Higgs, H. (2004). Art as an investment: Risk, return and portfolio diversification in major painting markets. Accounting & Finance, 2(44), 257–271.

Zimbalist, A. S. (2015). Circus maximus: the economic gamble behind hosting the Olympics and the World Cup. Washington D. C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Zimbalist, A. S. (2017). The Economic Legacy of Rio 2016. In Rio 2016: Olympic Myths, Hard Realities. Edited by Andrew S. Zimbalist. Washington D. C.: Brookings Institution Press, pp. 207–238.

Notas

Recibido: 10 de junio de 2020; Aceptado: 8 de agosto de 2020

Resumen

Según datos recientes del mercado del arte, unos pocos agentes institucionales tienen una gran cuota de mercado. En consecuencia, el mercado del arte se compone cada vez más de una serie de estrellas en el sentido de Rosen y Adler. Estas diferencias se maximizan en períodos de crisis. En Brasil y, más concretamente, en São Paulo, dos agentes sobrevivieron a la crisis económica posterior a los Juegos Olímpicos y el Mundial de Fútbol con una propuesta innovadora: expandir su negocio mediante fusiones y adquisiciones.

Antonio Almeida y Carlos Dale se dedican a comprar galerías rivales. En un país tan desigual económicamente como Brasil y, especialmente, el Brasil después de la crisis económica, esto es especialmente posible. Veremos algunas de las ventajas competitivas que esta práctica puede aportar a estos dos agentes.

Palabras clave

Arte contemporáneo, innovación, mercado del arte, mundo del arte, São Paulo, teoría institucional.Abstract

According to recent data from the art market, a few institutional players have gained a large market share. Consequently, the art market is increasingly made up of a series of stars in the sense of Rosen and Adler. These differences are maximized in periods of crisis. In Brazil and, more specifically, in São Paulo, two agents survived the economic crisis after the Olympic Games and the World Cup with an innovative proposal: to expand their business through mergers and acquisitions. Antonio Almeida and Carlos Dale are buying rival galleries. In a country as economically unequal as Brazil, and especially Brazil after the economic crisis, this is especially possible. We will study some of the competitive advantages that this practice can bring to these two agents.

Contemporary art; innovation; art market; art world; São Paulo; institutional theory

Fusions et acquisitions : le cas de São Paulo

Keywords

Contemporary art, innovation, art market, art world, São Paulo, institutional theory.Résumé

Selon les données récentes du marché de l’art, quelques acteurs institutionnels détiennent une part de marché importante. Par conséquent, le marché de l’art est de plus en plus constitué d’une série de stars au sens de Rosen et Adler. Ces différences sont maximisées en période de crise. Au Brésil et plus particulièrement à São Paulo, deux agents ont survécu à la crise économique après les Jeux Olympiques et la Coupe du monde avec une proposition innovante : développer leur activité par des fusions et acquisitions. Antonio Almeida et Carlos Dale rachètent des galeries rivales. Dans un pays économiquement aussi inégalitaire que le Brésil, et surtout le Brésil après la crise économique, cela est tout-à-fait possible. Nous étudierons quelques-uns des avantages concurrentiels que cette pratique peut apporter à ces deux agents.

Mots clés

Art contemporain, innovation, marché de l’art, monde de l’art, São Paulo, théorie institutionnelle.Resumo

Segundo dados recentes do mercado da arte, uns poucos agentes institucionais têm uma grande cota de mercado. Em consequência, o mercado da arte se compõe cada vez mais, de uma série de estrelas no sentido de Rosen e Adler. Essas diferenças se maximizam em períodos de crise. No Brasil, e mais concretamente em São Paulo, dois agentes sobreviveram a crise econômica posterior aos Jogos Olímpicos e ao Mundial de Futebol com uma proposta inovadora: expandir seu negócio mediante fusões e aquisições. Antonio Almeida e Carlos Dale se dedicam a comprar galerias rivais. Em um país tão desigual economicamente como o Brasil e, especialmente, o Brasil depois das crise econômica, isso é especialmente possível. Veremos algumas das vantagens competitivas que esta prática pode trazer para esses dois agentes.

Palavras-chave

arte contemporânea, inovação, mercado da arte, mundo da arte, São Paulo, teoria institucional.Art and uncertainty 1

It is difficult to know what we mean when we name something as ‘art’. Many cultures have a similar word, however that does not mean they give the same significance to the same thing. In fact, sometimes, even within the same society, different individuals may have a different material culture and call different things as ‘art’, being this one, a polysemic word. (Buchli et al., 2001; Hicks et al., 2010; Layton, 1991; Svašek, 2007)

(A) Ontologically, some disciplines such as philosophy have tried to provide general knowledge about it, with little success. (Cahn et al., 2008; Schelling, [1859] 1989). This little success is because, (A1) Philosophy has generally carried out an idealistic and almost romantic analysis of what art is. A theoretical analysis that was rarely based on a significative empirical testing of facts, but mainly, on simple individualism and subjective criteria. (Hendrix, 2005; Aristotle, 1996). Thus, discussions provided from aesthetics have focused their efforts on questions like what or which are the aesthetic categories, if the aesthetic sense is innate or learned, or if aesthetics must be linked or not to morality. (Hyman, 2002; Kant, [1790] 2008; Eco, [2004] 2010; Hume, [1757] 2013; Bermúdez et al., 2002; Machamer and Roberts, 1968; Peñuela, 2007).

However, a historical and even sociological analysis shows us that these aesthetic categories are also the fruit of the convention, and that they vary from one place and moment to another (Shiner, 2001). This is what from the iconology, experts name as ‘contamination’ or as ‘reinterpretation’. An example is the Aphrodite of Knidos. The representation of the goddess, being naked, was not permitted in the island of Kos. However, it was accepted in Knidos. After this acceptance and “once the message is integrated into the code of Greek art, the theme of Aphrodite totally naked will be endlessly repeated” (Castiñeiras, 2008, p. 29; Castiñeiras, 2008, p.104). Not less important is the fact that the transmission of a concept or idea to its practical application is not always carried out in the same way by all the subjects. 2

Figure 1. Aphrodite Cnidus (inv. 8619). (Bernardes Ribeiro, 2015). Palazzo Altemps – Rome.

(A2) There is an important second factor, and it is the transformation from the aisthesis to the askesis, from aesthetics to the discourse, produced mainly during the vanguards. This change implies that art might no longer necessarily be linked to aesthetics and its categories, but that needs a legitimator discourse, and this gave rise to the ‘philosophy of art’ as a field not necessarily linked to aesthetics (Michaud, 2009; Hegel, [1826] 2006; Danto, 1964).

(B) Previously, some of the interpretative frameworks to approach art had focused their attention on the artist’s intention (intentionalism), his resemblance to nature (mimesis) or some sort of essentialism — often closely linked to theological positions (Gilbert and Kuhn, 1972; Tatarkiewicz et al., 2005; Tatarkiewicz, 1980).

However, in cases of current art these are no longer (or not necessarily) the criteria used to discover whether something is art or not. In fact, a visit to any contemporary art museum shows few objects whose link with nature is trustworthy. It is easy to find, as well, works constituted with one intention but which have been exalted by completely different reasons (Preuss, 2018; EFE, 2008). Since the objective of this text is not to analyze the ontology of art, we will say that if none of these paradigms is still being used nowadays, it is mainly due to two reasons: (B1) The first one is the cultural changes. If art is a human product, it seems logical to infer that with cultural and social changes, its practices and approaches also change (Wolff, 1993). (B2) The second reason would be the own internal inconsistencies of these paradigms and theoretical frameworks (Meheus, 2002; Vickers, 2014).

Figure 2. Pasiteles School. Orestes and Pylades (aprox. 10 B.C.). Source: El Prado Museum.

Figure 3. Yonatan Vinitsky. New New Yask Over (Blue) Source: Tel Aviv Museum of Art. (2011).