DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.10801Published:

2017-08-04Issue:

Vol 19, No 2 (2017) July-DecemberSection:

Research ArticlesClassroom interaction in ELTE undergraduate programs: characteristics and pedagogical implications

Interacción en el aula en los programas de pregrado de enseñanza del Inglés: características e implicaciones pedagógicas

Keywords:

interacción en el aula, agendas conversacionales, clases en PPEI, patrones interaccionales (es).Keywords:

classroom interaction, conversational agendas, ELTE, interaction patterns (en).Downloads

References

Álvarez, J. A. (2008). Instructional sequences of English language teachers: An attempt to describe them. How Journal, 15, 29-48.

Anderson, J., Oro-Cabanas, J. M., & Varela-Zapata, J. (Eds.) (2004). Linguistic perspectives from the classroom: Language teaching in a multicultural Europe. Spain, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela: Unicopia Artes Gráficas, S. L.

Cameron, D. (2001). Working with spoken discourse, London: SAGE Publications.

Castañeda-Peña, H. (2012). Profiling academic research on discourse studies and second language learning. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14 (1), 9-27.

Castrillón-Ramírez, V. A. (2010). Students’ perceptions about the development of their oral skills in an English as a Foreign Language Teaching Program (unpublished underdegree dissertation). Pereira, Colombia: Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira.

Castro-Garcés, A. Y., & López-Olivera, S. F. (2013). Communication strategies used by pre-service teachers of different proficiency levels. How Journal, 21(1), 10-25.

Cazden, C. (1986). Language in the classroom discourse. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 7, 18-33.

Cazden, C. (1988). Classroom discourse: The language of teaching and learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Consolo, D. A. (2014). Teachers’ action and student oral participation in classroom interaction. In J. K. Hall & L. S. Verplaetse (Eds.), Second and foreign language learning through classroom interaction (pp. 91-108). USA: Routledge.

De Mejía, A. M. (2002). Power, prestige, and bilingualism: International perspectives on elite bilingual education. UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R., & Sheen, Y. (2006). Reexamining the role of recast in second language acquisition. SSLA, 28, 575–600.

Garton, S. (2002). Learner initiative in the language classroom. ELT Journal, 56 (1), 47-56.

Gonzalez-Humanez, L. E., & Arias, N. (2009). Enhancing oral interaction in English as a Foreign Language through Task-based learning activities. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 2(2), 1-9.

Hélot, C., & De Mejía, A. M. (Eds.) (2008). Forging multilingual spaces: Integrated perspectives on majority and minority bilingual education. UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Herazo-Rivera, J. D. (2010). Authentic oral interaction in the EFL class: what it means, what it does not. Profile Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 12 (1), 47-61.

Herazo-Rivera, J. D., & Sagre-Barbosa, A. (2015). The co-construction of participation through oral mediation in the EFL classroom. Profile Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 18(1), 149-163.

Hutch, T. (2006). Negotiating structure and culture: L2 learners’ realization of L2 compliment-response sequences in talk-in-interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 38, 2025-2050.

Inan, B. (2012). A comparison of classroom interaction patterns of native and non-native EFL teachers. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 2419-2423.

Johnson, K. (1995). Understanding communication in second language classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kasper, G. (2009). Categories, context, and comparison in Conversation Analysis. In H. Nguyen & G. Kasper (Eds.), Talk-in-interaction: Multilingual perspectives (pp. 1-28). USA: National Foreign Language Resources Center.

Kharaghani, N. (2013). Patterns of interaction in EFL classroom. Global Summit on Education, 1, 859-864.

Kramsch, C. (Ed.). (2002). Language learning and language socialization: Ecological perspectives. New York: Continuum.

Lyster, R. (1998). Recasts, repetition, and ambiguity in L2 classroom discourse. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 20, 51-81.

Long, H. M., & Sato, C. (1983). Classroom foreigner talk discourse: Forms and functions of teachers’ questions. In H. W. Seliger & M. H. Long (Eds.), Classroom oriented research in second language acquisition (pp. 268-286). Cambridge: Newbury House Publishers, Inc.

Lucero, E. (2011). Code switching to know a TL equivalent of an L1 word: Request-Provision-Acknowledgement (RPA) Sequence. How Journal, 18, 58-72.

Lucero, E. (2012). Asking about Content and Adding Content: Two patterns of classroom interaction. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14 (1), 28-44.

Lucero, E. (2015). Doing research on classroom interaction: approaches, studies, and reasons. In E. Wilder & H. Castañeda-Peña (Eds.), Studies in discourse analysis in the Colombian context (pp.91-122). Bogota, Colombia: Editorial El Bosque.

Markee, N. (1995). Teachers' answers to students' questions: Problematizing the issue of making meaning. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 6(2), 63-92.

McDonough, K. & Mackey, A. (Eds.) (2013). Second language interaction in diverse educational contexts. Philadelphia, USA: John Benjamins Publishing Co.

Mori, H. (2000). Error treatment at different grade levels in Japanese immersion classroom interaction. Studies in Language Sciences, 1, 171-180.

Rashidi, N., & Rafieerad, M. (2010). Analyzing patterns of classroom interaction in EFL classrooms in Iran. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 7(3), 93-120.

Rosado-Mendinueta, N. (2012). Contingent interaction: A case study in a Colombia EFL classroom. Zona Próxima, 17, 154-175.

Schegloff, E. (1997). Third Turn Repair. In G. R. Guy, C. Feagin, D. Schiffrin, & J. Baugh (eds.), Towards a social science of language: Papers in honor of William Labov. (Volume 2) Social Interaction and Discourse Structures (pp. 31-40). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Schegloff, E. (2000). When others initiate repair. Applied Linguistics, 21(2), 205-243.

Seedhouse, P. (2004). The interactional architecture of the second language classroom: A conversational analysis perspective. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sinclair, J. M., & Coulthard, R. M. (1975). Towards an analysis of discourse: The English used by teachers and pupils. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ûstûnel, E., & Seedhouse, P. (2005). Why that, in that language, right now? Code-switching and pedagogical focus. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 15(3), 302-325.

Van Lier, L. (1988). The classroom and the language learner. New York: Longman.

Walsh, S. (2011). Exploring classroom discourse: Language in action. NY: Routledge.

Zhang-Waring, H. (2016). Theorizing pedagogical interaction: Insights from Conversation Analysis. New York, Routledge.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Classroom Interaction in ELTE Undergraduate Programs: Characteristics and Pedagogical Implications1

Interacción en el aula en los programas de pregrado de enseñanza del Inglés: Características e implicaciones pedagógicas

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Lucero E. & Rouse M. (2017). Classroom Interaction in ELTE Undergraduate Programs: Characteristics and Pedagogical Implications, Colomb. appl linguist.]., 19(2), pp. 193-208.

Received: 08-Jul-2016 / Accepted: 26-May-2017

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/22487085.10801

Abstract

This article describes how classroom interaction occurs between teacher educators (TEs) and students in three undergraduate programs of English language teacher education (ELTE) in Bogotá, Colombia. Thirty-four sessions of classroom instruction of nine TEs were observed and transcribed. Data were analyzed under two methodologies— ethnomethodological conversation analysis (ECA) and self-evaluation of teacher talk (SETT). Findings reveal that ELTE classes are divided into transactional episodes that do not necessarily happen in the same order and that are composed of interaction patterns with an extended pedagogical purpose. Further analysis of these interaction patterns unveils that both TEs and students come into the classroom with a pre-planned conversational agenda which contains pedagogical and interactional purposes. Imbalance between both agendas creates instructional paradoxes that send mixed messages to students about how to interact with TEs in class activities. These findings open a discussion on how the identified patterns create a type of classroom interaction that is rather transactional than spontaneous. This discussion in turn contributes to discovering how classroom interaction may occur in ELTE undergraduate programs and how much of it truly achieves pedagogical and interactional goals.

Key words: classroom interaction, conversational agendas, ELTE, interaction patterns

Resumen

Este artículo describe la manera en que ocurre la interacción de aula entre los docente-educadores (DE) y los estudiantes en tres programas de pregrado en la enseñanza del Inglés (PPEI) en Bogotá, Colombia. Treinta y cuatro sesiones de nueve DE fueron observadas y transcritas. Los datos se analizaron desde dos metodologías—análisis etno-metodológico de la conversación y auto-evaluación del modo de hablar del profesor. Los hallazgos revelan que las clases en los PPEI están divididas en episodios transaccionales que no necesariamente suceden en el mismo orden y que se componen de patrones interaccionales con un propósito pedagógico extendido. Un análisis más profundo de estos patrones revelan que tanto los DE como los estudiantes llegan al aula con una agenda conversacional pre-planeada compuesta de propósitos pedagógicos e interaccionales. Un desbalance entre ambas agendas crea paradojas instruccionales que envían mensajes contradictorios a los estudiantes sobre cómo interactuar con los DE en las actividades de clase. Los resultados abren la discusión sobre cómo los patrones identificados crean un tipo de interacción en el aula que es más bien transaccional que espontánea. Esta discusión igualmente contribuye a descubrir cómo la interacción del aula ocurre en los PPEI y cuanto de esta realmente alcanza los propósitos pedagógicos e interaccionales.

Palabras clave: interacción en el aula, agendas conversacionales, clases en PPEI, patrones interaccionales

Introduction

Interaction patterns between teacher and students in the English as a second language (ESL) classroom have been considerably studied. The results display a variety of interaction patterns that reveal the way in which teachers and students construct conversations for English language learning; for example, adjacency pairs (Long & Sato, 1983; Markee, 1995), minimal pairs (Cameron, 2001; Hutch, 2006), and the initiation-response-evaluation/feedback (IRE/F) sequence (Cazden, 1988; Ellis, 1994; Sinclair & Coulthard, 1975). In studies of ESL interaction patterns, students can also initiate the construction of conversations for English learning. Those patterns seek information about teacher questions, explanations, and ideas (Garton, 2002); or for accuracy in language use as recast (Lyster, 1998; Ellis & Sheen, 2006), repair (Schegloff, 1997; 2000), and code-switching (üstünel & Seedhouse, 2005).

Studies on interaction patterns in the English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom have analyzed how native and non-native teachers interact with students, usually in the Asian (see for example Mori, 2000; Zhang-Waring, 2016), European (Anderson, Oro-Cabanas, & Varela-Zapata, 2004; Inan, 2012) and Arabian (Rashidi & Rafieerad, 2010; Kharaghani, 2013) contexts. The interaction patterns found reveal close similarities with ESL classroom interaction, with IRE/F and repair being the most common within teacher-student interactions in EFL classes.

Such studies coincide in explaining that interaction patterns can vary in relation to the context of the interaction, teacher and student conversational agendas, and teaching and learning strategies. In accordance with this premise, and by understanding that classroom interaction is one of the means by which language teaching and learning are revealed (Seedhouse, 2004; Lucero, 2015; Walsh, 2011), the research study that we present in this article investigates the manner in which classroom interaction occurs between teacher educators (TEs) and students in English language teacher education (ELTE) undergraduate programs. Due to the educational orientation of these programs, we explore if the interactional structure of this classroom type maintains specific interactional characteristics that may differ from ESL or EFL classrooms. The present study aims to open an exploration into unveiling the manner in which interaction between TEs and students happens in classrooms where English is not only the target language but also the language by which teaching content is taught and practiced.

Research on interaction patterns that TEs and students co-construct during class activities in ELTE undergraduate programs has the potential to reveal the interactional practices and particular understandings about how English language classroom interaction happens in this context. As classroom interaction patterns are the evidence and realizations of teaching strategies for language learning, a study on this issue may inform how teaching methodologies and practices configure students’ own practices to mediate and assist English learning. Despite this fact, this study does not seek to provide formulas for how to interact in ELTE undergraduate programs. Doing so would inappropriately be an attempt to script classroom interaction for this context going against the premise of the language classroom as a social institution (Cazden, 1988; Ellis, 1994; Markee, 1995; Rymes, 2009; Seedhouse, 2004) with an ever-evolving, newly occurring communication system.

Theoretical Framework

In the previous introduction, we stated that interaction patterns have been thoroughly studied in both ESL and EFL classrooms where English is taught for general uses. In this theoretical framework, we review studies focused on teacher-student interaction in the EFL classroom and in ELTE undergraduate programs in Colombia. In order to unveil how interaction happens in these language classrooms, emphasis on interaction patterns becomes necessary. Interaction patterns are repetitive sequences of turns in the interaction between two speakers in a context (Cazden, 1986; 1988; Sinclair & Coulthard, 1975), for example, teacher and students in the language classroom. In EFL classrooms, both teacher and students interact with each other to provide content, learn and use the language, and manage conversation (Johnson, 1995; Kasper, 2009; Lucero, 2015; Van Lier, 1998).

In Colombia, classroom interaction has been the focus of increasing interest. Studies on bilingualism and prestige (De Mejia, 2002), enhancement of multicultural spaces (Hélot & De Mejia, 2008), and interaction in diverse classroom contexts (McDonough & Mackey, 2013) are prominent in both school and university contexts. These studies have found that English language classroom interaction brings resources in order to position teachers and students in conversation according to classroom activities and contexts (as facilitators, evaluators, respondents, language resources, collaborators, etc.). They also reveal the diversity of teaching methodologies in English learning (regularly adjusted to a variety language teaching approaches under the principles of communicative language teaching).

Mostly in school contexts, research studies discuss pedagogical and interactional factors in the English language classroom with the aim of exploring the development of language skills (Castañeda-Peña, 2012). For example, Herazo-Rivera’s (2010) study with secondary students displays that teacher-student interaction promotes meaningful EFL learning through a dialogue-based approach, which in turn contributes to the development of oral communication although the interactions might sound scripted (essentially following the IRE sequence). Similarly, a subsequent study carried out by Herazo-Rivera and Sagre-Barboza (2015) with an elementary English classroom found that teacher-student interaction mediates for both teaching and learning English. Also with secondary students, Rosado-Mendinueta (2012) affirms that teacher-student interaction incorporates learning-generating opportunities in traditional exchange patterns (mostly IRF sequences, greetings, check-out, and reading-aloud activities). Finally, Gonzalez-Humanez and Arias (2009), in an analysis of secondary task-based classes, state that teacher-student interaction is also teacher-initiated, centers the attention on providing explanations, and requests for student information exchange.

In the university context, Lucero (2011, 2012, 2015) has found that, apart from the aforesaid interaction patterns, teachers and students generally co-construct and maintain three other patterns: asking about content, adding content, and the request-provision-acknowledgement (RPA) sequence. The first two patterns unveil the manner in which teachers and students manage content in interaction, and the third makes evident the sequence of turns when students ask teachers for the L2 equivalent of an L1 word. These works also endow the panorama of how English language classroom interaction happens in the Colombian context.

Nonetheless, research investigating

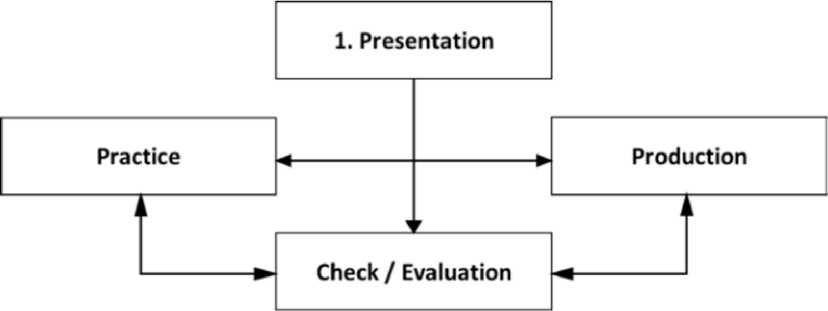

classroom interaction specifically in ELTE undergraduate programs in Colombia is scarce. The few encountered reveal varied functions of the interaction between TEs and students, but they do not specifically indicate how classroom interaction happens or what interaction patterns emerge from classroom practices. For instance, in a study with fourth-semester students, Castrillón-Ramírez (2010) found that classroom interaction helped students improve their ability to express and understand their ideas by developing more fluency, vocabulary, pronunciation, and intonation. Alvarez (2008) found that six TEs generated what the author refers to as “pedagogical interactions” in the five-identified stages of their classes: presentation, practice, production, homework check, and evaluation. Castro-Garcés and López Olivera (2013) found that student participants used a variety of communication strategies (e.g., message abandonment, topic avoidance, and code-switching among others) in their interactions in a conversation course.

These studies have found varied functions of interaction in EFL and ELTE classrooms that unveil a variety of interactional practices. The study presented in this article aims to enrich the literature about classroom interaction in ELTE undergraduate programs. Because of the educational orientation of these programs, exploring the ways and reasons in which classroom interaction happens can inform teaching methodologies and practices used to educate future English language teachers.

Research Methodology

Two research approaches —ethnomethodological conversation analysis (ECA) and self-evaluation of teacher talk (SETT)— were implemented to identify the manner in which classroom interaction occurs in ELTE undergraduate programs, its characteristics, and pedagogical implications. In total, 34 classroom instruction sessions of nine TEs were video-recorded and transcribed. The sessions were both content-based and language-based classes at different levels of English proficiency of three

ELTE undergraduate programs (usually between A2 and B2 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference; CEFR). Two occurred in private universities, and the other in a state university. These three programs have two common aspects in the curriculum: (a) a fundamental axis in which English language-based courses are organized sequentially per English language proficiency levels (from A1 to B2/C1), and (b), a pedagogical axis in which English language pedagogical content-based courses are organized per semester (from the fourth to the tenth). These courses cover pedagogical content regarding English language teaching, didactics, practicum, material design/development, Anglophone literature, applied linguistics, and intercultural/oral communication. The TEs all have a certified English language C1 proficiency level, and hold at least a master’s degree in either applied linguistics, education, or English language teaching. The TEs have between 6 to 16 years of experience in teaching related courses at university level.

The ECA approach (Seedhouse, 2004; see Table 1 below) served to identify and describe the interaction patterns. The transcriptions were read line by line to identify the interaction patterns and the instances when they emerged. A matrix of analysis was designed containing the identified interaction patterns with their respective description. The exchanges before and after each identified pattern were studied in order to explain the prominent characteristics, moment, and reasons of emergence of each interaction pattern. These explanations were included in the matrix.

Table 1. The Two Research Approaches Followed in the Study

ECA Stages

1. Unmotivated Looking: Class observations and transcripts to identify interaction patterns

2. Inductive Search: Establishment of instances when the interaction patterns emerge

34 video-recorded 3. Establishing Regularities and Patterns: sessions and their Description of interaction patterns transcriptions 4. Detailed Analysis of the Phenomenon:

Matrix of analysis Explanation of the emergence of interaction

patterns and their characteristics (when and why) 5. Generalized Account of the Phenomenon: Determining the incidence of the interaction patterns in language teaching & learning.

SETT Modes

a. Managerial Mode: the way in which the TE organizes and presents learning

b. Materials Mode: the interaction created 9 interviews from the use of material designed for the with the TEs class

Materials used c. Skills and Systems Mode: the interaction in the sessions created in the language practice activities d. Classroom Context Mode: the genuine communication between TEs and students in class

The nine observed TEs were interviewed about the way in which they organized learning, worked with the materials, and created interaction with the students in the observed class lessons. Subsequently, the SETT approach (Walsh, 2011; see Figure 1) was applied to this data to determine the pedagogical implications of the identified interaction patterns.

A second matrix of analysis was then created containing the insights gathered in each interview. As Walsh (2011) suggests, these insights were organized into four modes: managerial, materials, skills and systems, and classroom context. Finally, the two matrices were put together to analyze the relationship between the identified interaction patterns, their characteristics, and the insights in the modes. This helped determine the manner in which classroom interaction occurred in the three ELTE undergraduate programs.

Results

When identifying the interaction patterns and the moment and reasons of their emergence in the observed ELTE classes, we noticed that each session was divided into what we call transactional episodes. Each episode contains a series of relevant interactional exchanges that institute what the participant TEs and students may consider as a class stage; for example, the TE-explanation stage or the student-practice stage. We call these episodes transactional because the exchanges found within each mostly tend to maintain a unique pedagogical purpose and are usually composed of the same interactional sequences.

In agreement with Alvarez (2008), we found that the TEs divided each session into five stages: presentation, practice, production, (assignment) check, and evaluation. Different from these findings, the transactional episodes in our analysis seldom happened in the same indicated order. In the observed ELTE classes, episodes happen in clusters that combine them in varied forms (see Figure 1). The reasons for these combinations are the pedagogical and interactional purposes that each TE had in their conversational agenda for each lesson (an explanation about this issue will be outlined below). In other words, the clusters are the

Stages found in the ELTE classes

Common Clusters

Content-based lessons:

• Presentation + Practice/Production + Check/Evaluation + Production

• Presentation + Practice/Check + Production + Evaluation Language-based lessons:

• Presentation + Practice/Production + Check/Evaluation

• Presentation + practice/Check + Production

• Presentation/Practice + Production + Check/Evaluation

result of the way in which the TEs organized each lesson from its contents, planned materials, and class activities.

Figure 1 above indicates that the five stages may happen in different clusters in the observed ELTE content-based and language-based lessons but always with the presentation stage at first. The combination of these stages reveals that the ELTE classroom interaction analyzed in this study started with the TEs’ presentation of the contents, activities, and tasks to do during the lesson, followed by either student practice or production of the contents presented. This practice or production stage could be checked by the TE, usually with the aim of offering a new stage of practice or production. The evaluation stage generally occurred at the end of each session.

In each transactional episode, we found the same interaction patterns as those identified in the stages of EFL classes, that is, IRE/F sequence, clarification requests, nomination, RPA sequence, repair, recast, asking about content, and adding content (see Table 2). However, every so often

IRE

(turns 1, 2, 4)

Nomination (turn 1)

Adding Content (turn 3)

IRE sequence (turns 1, 2, 3)

Repair (turns 2, 9)

Code-switching (turn 6)

Asking about content (turns 4-5, 7-8)

RPA sequence (turns 1, 2, 3)

Clarification Request (turns 4-5)

Code-switching (turns 5, 7, 8)

IRF sequence (turns 6, 7, 8)

Table 2. Samples of the Interaction Patterns Identified in ELTE Classes

Sample Excerpt 1 (Content-based class, B1 Level):

(TE is checking Ss’ learnings form a previous session)

(1) TE: As this is part of inflections, who remembers the name of this symbol [,]? You, S1.

(2) S1: mmm...

(3) S2: schwa, la que es así [air-drawing and inverted e] [the one that is like this]

(4) TE: uhm, very good. You need to recognize these symbol to knhow how to say them well.

Sample Excerpt 2 (language-based class, B2 level):

(TE is opening space for the Ss to lead the class activity)

(1) TE: Now you have to explain the activity. Who wants to do it?

(2) S1: So, every bodyruns, take, sorry, takes the ball and then stops (looking at the teacher)

(3) TE: yes, but not running too far.

(4) S2: So, one person at a time has to say something.

(5) TE: uhm, one persona at a time.

(6) S2: pero tenemos que decirlos

[but do we have to tell all the directions again]

(7) S3: Buenos, digamos. Karen, you say, I go to Sthepan, run, pick up the ball, and say stop, but you must run too? (Pointing out to S2).

(8) TE: everybody running with her.

(9) S3: Then you say, throw the ball to Stephan and she, sorry, he run.

(10) TE: and when people stop running?

(11) S3: hmmmmm

Sample Excerpt 3 (language-based class, A2 level):

(TE is explaining language use at front)

(1) S: Teacher, how I say bailando?

(2) TE: dancing

(3) S: Hmm. So, how I say this with the verb dancing

(4) TE: Hmm, what do you want to say?

(5) S: go and dance with ir a bailar

(6) TE: .What is the first that you need to consider because it is with the verb in gerund [dance] and this is a ver in the past [could]? Houw would you explain this?

(7) S: Ahh, so if I writethe sentence (writing on the textbook "could go dancing").? Is podría ir a bailar, like invitation or posible.

(8) TE: Aha, this sounds better. it is for you to know that this [could] means podría and go dancing, you know, is ir a bailar.

(9) S: Ahh, thank you teacher.

Note. TE= Teacher Educator; S= Student

these patterns had an extended purpose during interaction. While interaction patterns in EFL classes have only the purpose of teaching, correcting, and practicing English for general uses, patterns in the recorded ELTE classes also had the purpose of opening spaces for learning and practicing how to teach and correct this language.

These purposes can be traced by determining the functions of the turns (see Table 3) that compose the exchanges in each transactional episode and the reasons that the TEs expressed to construct the interactional sequences (reported in the interviews).

The three sample excerpts in Table 2 above demonstrate how the TEs maintained pedagogical efforts for the students to learn and practice how to teach and correct English by using repetitive interaction patterns. Those are the IRE/F sequence (Sinclair & Coulhart, 1975) or the RPA sequence (Lucero, 2011), adding or asking about content (Lucero, 2012), repair (Schegloff, 1997; 2000), and code-switching (üstünel & Seedhouse, 2005). All of these patterns in combination demonstrate the manner in which TEs model classroom practices or request for English language contents. Table 3 indicates how classroom talk is mostly filled with the TEs’ use of commands, explanations, elicitations, and clarifications—the type of turns that mostly control classroom interaction. Along with these interaction patterns, we identified two others that were recurrent: repetition of students’ answers and approval bids.

These other two common interaction patterns reveal the tendency that the TEs had to repeat the students’ answers with the aim of simultaneously acknowledging the reply, correcting language mistakes, and encouraging further participation (as shown in sample excerpts 4 and 5 below). Sample excerpt 6 shows the cycle of a TE approval bid and student facilitatory reply. The TEs used this cycle to confirm whether the students were attentive to and in agreement with their explanations or statements, although further analysis of the subsequent turns confirms that they were not always attentive or in agreement, rather some of the students just replied mechanically.

In the analysis of these interaction patterns, we noticed that the TEs wanted to emphasize three aspects of language teaching:

1. Obtaining a variety of strategies to teach and learn English. Sample excerpt 1 in Table 2 provides evidence of this aspect. The TEs wanted the students to remember language concepts. This helped students to understand how to use English correctly while speaking or teaching it. Equally, sample excerpts 4 and 5 in Table 4

Student talk

Table 3. Turns and their Frequency in Interaction Patterns

Turns identified

Frequency*

Teacher Educator talk

|

Markers (ok, well, let’s , yes?) |

4.3 |

4.1 |

|

Repetition of answers |

51.4 |

2.8 |

|

Commands |

59.5 |

8 |

|

Explanations |

72.3 |

11.1 |

|

Replies |

36.4 |

49.1 |

|

Code-switching / mix-coding |

12 |

27 |

|

Elicitations |

74.4 |

38.5 |

|

Confirmation checks |

13.2 |

14.2 |

|

Clarifications |

36 |

8.3 |

|

Corrections |

23.9 |

0.9 |

|

Nominations |

11.1 |

2.3 |

* The type of turns were counted with the aid of the Longman Mini-Concordancer software. The frequency was obtained by getting the standard deviation and variance of the repetitions.

Table 4. Other Interaction Patterns

Interaction Patterns Identified

TE initiation without initial nomination, to the class, repetition of the initiation

S short answer

TE repetition of the S answer

TE question

S short answer (turns 2, 4, 6)

TE repetition of the S answer, TE request for expansion (turns 3, 5, 7)

TE directions TE approval bid (turns 1, 3, 5)

Ss facilitatory reply (turns 2, 4)

Sample Excerpt 4 (Content-based class, B2 Level):

(TE is correctiong Ss’ answers in a language exercise)

(1) TE: ok. In G= (to the whole class)(3 seconds) in G? (3 seconds) Another person who wants to participate? Ok, you (to a student who has just volunteered to answer)

(2) S: (Reading from the material) that will be raised for charity.

(3) TE: that will be raised for charity tonight, will be raised (S nods) passive voice. H?

Sample Excerpt 5 (language-based class, B1 level):

(TE is asking about an emerging topic while checking out the answers of a language drill)

(1) TE: What time do you ussually have to leeeeave the, uh, the hotel?

(2) S: (mumbling) 1 pm?

(3) TE: At 1pm? Yes? Any idea?... WHen you leave. It’s usually? Between.

(4) S: (mumbling) 3.

(5) TE: 1 and? And 3pm. If you stay, what happens?

(6) S: Charge.

(7) TE: Yeeees, you get and extra large. You have pay for? Another? Night.

Sample Excerpt 6 (language-based class, B1 level):

(TE is giving directions for a class activity)

(1) TE: We are going to be permanently speaking all the time. Because English is beautiful! Yes or no?

(2) Ss: Yes

(3) TE: Yeahhhhhhh. And it’s very easy. Yes or no?

(4) Ss: Yes

(5) TE: Yes, yes. It’s really easy. You know what the thing is? Time of exposure to the language. Yeah?

Note. TE= Teacher Educator; S= Student

expose how the TEs modeled how to encourage students produce instructed language more often verbally in the class activities.

2. Knowing how to give instructions of classroom activities. Sample excerpt 2 in Table 2 shows how the TEs asked the students to practice how to give instructions of class activities. In the same way, sample excerpt 6 in Table 4 demonstrates discursive routines to check students’ attention.

3. Creating ways to explain how language works. As sample excerpt 3 in Table 2 demonstrates, the TEs guided the students towards the creation of explanations about language structures. Sample excerpts 4 and 5 in Table 4 can also be an example since the TEs modeled a way to explain language inductively.

Consequently, the interaction patterns that we identified depict two main characteristics of the ELTE classes. First, TEs organize class sessions into distinguishable transactional episodes (organized in varied clusters) containing similar interaction patterns to EFL classes but with an extended pedagogical purpose. Second, this pedagogical purpose aims not only to teach, correct, and practice English for general uses, but also to open spaces for learning and practicing how to teach and correct this language.

These initial findings arose from the analysis of what we call the "outer layer" of ELTE classroom interaction. However, in order to explain the reasons of emergence of the identified transactional episodes, an "inner-layer" analysis of the interaction patterns that occur in each transactional episode becomes necessary. This analysis focuses attention onto the TEs’ explanations and reasons to co-construct their interactions with the students, materials, and activities used in class as well as the way in which learning is organized in each lesson.

TE and Student Conversational Agendas

According to the TEs’ responses in the interviews and the students’ responses to an on-line survey4, they both come into the classroom with acquired routines of how classroom interaction should happen and a conversational agenda for each lesson. The acquired routines have been learned from previous interactional experiences lived in varied classrooms which include, for example, providing explanations when requested, responding to questions, requesting clarification or confirmation of explanations and directions, and participating in class discussions. These patterns are co-constructed to negotiate meaning (the topic to teach and learn) with a preferred organization of turns (the way to initiate, maintain, and end an exchange). Conversational agendas in turn are expected to have certain formats and contents (Tracy & Robles, 2013), the purposes of which are locally managed only by the participants’ orientations to prior and subsequent turns in interaction (Benwell & Stokoe, 2006; Rymes, 2009). Considering both insights, we determine that the TEs’ and the students’ conversational agendas observed in this study are composed of pedagogical

4 We designed an on-line survey to know preservice teachers’ interactional practices in their ELTE classes. The survey asked about the ways in which interaction happens with their TEs during class activities and its usefulness for English teaching and learning.

and interactional purposes4, the former sustains what is to be spoken, taught or learned, while the latter indicates how to do so in interaction. Sample excerpt 7 in Table 5 gives an example of this issue.

When the TE’s and the student’s agendas coincide in their pedagogical and interactional purposes as in sample excerpt 7, there are more opportunities to mediate and assist language learning. However, both agendas do not always agree on what to talk about and how. When both agendas differ, fewer opportunities to mediate and assist language learning happen, revealing that the intended pedagogical purposes cannot be translated into actual interactional realizations. The following two sample excerpts in Table 6 exemplify this fact.

In sample excerpt 8, the TE’s conversational agenda orients to encouraging students’ oral participation in which they wonder how to reply in the current interactional situation. Under the same perspective, in sample excerpt 9, the TE’s conversational agenda orients towards encouraging students to focus on the current class activity while they, in turn, show resistance in their following actions. In both excerpts, the TEs’ agenda clashes with that of the students. Thus, there is

Table 5. Pedagogical and Interactional Purposes of Conversational Agendas

Sample Excerpt 7 (language-based class, B1 level):

(TE is asking for Ss expansión of their answers)

(1) TE: Don’t you have plants in you houses? Inside the house?

(2) S1: Yes

(3) S2: No, I... cómo se dice detrás? [how do you say detrás in English]

(4) TE: Take them out (mentioning her hand behind her) in the backyard.

(5) S2:mmm, yes, but in my case it’s different because it’s a mountain.

(6) TE: ummmmmm, so you don’t need, you don’t need plants inside your garden.

(7) S2: Yes, I have plants inside my house, but cómo se dice detrás?

(8) TE: behind?

(9) S2: behind, yes, behind my house are a mountain.

(10) TE: ok, there are mountains?

(11) S2: Yeah

TE and student’s conversational agenda:

- Pedagogical purpose: Discussion topic. Mutual efforts to create meaning.

- Interactional purpose: Using varied communication strategies to add and clarify content.

Table 6. Difference in the Purposes of the Conversational Agendas

Interaction Patterns Identified

Sample Excerpt 8 (Content-based class, B1 Level):

(TE is asking for Ss expansión of their answers)

(1) TE: For example, Melisa, what were you given for your las birthday?

(2) S: (no reply)

(3) TE: nothing? Eh, how do you say no me dieron nada?

(4) S: I wasn’t given

(5) TE: I was given nothing.

(6) S: Nothing, yes.

Sample Excerpt 9 (content-based class, B1 level):

(TE is expplaining a topic)

(1) TE: Can I help you with a Word, Darling? Any Word that you need.

(2) S: No teacher (Using Smart phone)

(3) TE: Are you checking your e-mail?

(4) S: No, teacher.

(5) TE: Nooo no no no, never (ironic tone).

(6) S: No, teacher.

(7) TE: you don’t need your cell-phone here, then.

TE agenda:

Encourage S to participate Student agenda:

Avoid replying due to uncertainty of language use

TE agenda:

- Pedagogical purpose: make Ss focus on the class activity

Interactional purpose: know what Ss are doing, how and why

Student agenda:

- Pedagogical purpose: unidentifiable - Interactional purpose: defend own action

no agreement on what to talk about and how; as a result, opportunities to mediate and assist language learning are scarce. When this situation occurred, the TEs’ normal reaction was to adjust their interactional purposes to the interaction that the students were proposing (see for example turns 3-6 in sample excerpt 8, and turns 3-7 in sample excerpt 9)5. We noticed that students rarely modified their conversational agendas in line with the TEs’ demands. Therefore, we assert that TEs are more willing to modify the interactional purposes of their conversational agendas than students are, however, the same is not true concerning their pedagogical purposes. This may also be one of the reasons that the ELTE classes are filled with more TE talk than student talk. The TEs usually had to make many demands and use varied conversational strategies for the students to talk in class about the contents and language uses presented in the class activities.

The interaction patterns found, understood as realizations of TE and student conversational agendas, also reveal a type of communication that seems to be common in language teaching and learning. This communication is governed by TEs in the way in which they organize learning with the materials, resources, activities, and corresponding indications or explanations (Walsh, 2011). In the observed classes, this organization made the students assume only a passive interactional role. These communication and organization facts unveil, on the one hand, a type of interaction that perpetuates a few particular interaction patterns, which do not seem to allow much L2 learning for spontaneous interaction inside and outside of the ELTE classroom. On the other hand, these communication and organization facts unveil an interaction type that is not dynamic but rather transactional—"just to get things done" (Richards, 2008)—and predictable (Rymes, 2009) with little scope for social interaction, conversational creativity and spontaneity. These results align with other research investigating L2 teacher’s action and student oral participation in the EFL classroom (Consolo, 2014; González-Humanez & Arias, 2009).

Findings in our study reveal that the observed ELTE classes were largely organized according to predictable events, habitual classroom procedures, and repetitive ways of interacting. These established practices develop a competence within the TEs and students to interact in the classroom under specific scripts and with distinguishable moves (as in the thus-far identified interaction patterns and conversational agendas shown in this article). Expanding Walsh’s (2011) classroom communicative competence into the ELTE classroom, both the TEs and students

seemed to share a general understanding of how to interact in the classroom. In our point of view, and in agreement with Cazden (1988), this understanding gives only the illusion that language learning is frequently occurring and that knowledge is regularly being shared when that is not what may actually be happening in every exchange. Some realizations of interaction patterns only happen mechanically in what we may call interactional fillers, or sequences of turns that fill classroom interaction without holding or reaching a teaching-learning purpose. TEs would then need to think of other ways to improve classroom interaction (studying everyday/ spontaneous interactions in other contexts, for example) since pre-planned conversational agendas and scripted interaction patterns identified in our study predict interactional outcomes that turn ELTE classroom interaction into a set of rather transactional episodes: repetitive interactional

transactions of established exchanges that do not regularly encourage opportunities for spontaneous interaction.

Instructional Paradoxes - Mixed Messages that TEs Send to Students

As explained above, the participant TEs generally act with an interactional framework in mind based on their perceptions of how ELTE classroom interaction should occur. This perception is formed by the construction of the pedagogical and interactional purposes that they wish to accomplish throughout the class session. When there is incoherence in the way these purposes are acted out in speech by both parties, it creates a disparity leading to what we refer to as an ‘instructionalparadox,' or a mixed message that the TEs send to the students by saying that interaction will happen in one way for pedagogical purposes but results in it being done differently. As Seedhouse (2004) explains, "the pedagogical message... is being directly contradicted by the interactional message" (p. 175; emphasis in original). Furthermore, as Harjanne and Tella (2009) point out, teaching actions that are seemingly contradictory or opposed to stated ones and yet seem true in interaction. The presence of these types of instructional paradoxes in ELTE classroom interaction creates an incoherence between the pedagogical purposes and the interactional purposes in the conversational agendas of both TEs and students.

As mentioned in the previous sections of this article, within the observed ELTE classrooms, there existed a (co) construction of objectives and agendas according to the pedagogical and interactional purposes in both TEs’ and students’ conversational agendas. The pedagogical purposes were formed by the objectives of the class itself, involving factors of subject, context, TE teaching style, student learning style, and their co-construction of space. The result of these objectives and the (co) construction of agendas from the interactional purposes of each party created the co-operative relationship between these interactants in classroom interaction (Seedhouse, 2004). It is this co-operative relationship that we have observed and analyzed in order to reveal interactional exchanges that demonstrate opposition in terms of how interaction occurs in the ELTE classroom.

Although our study has found the paradoxes exposed by Seedhouse (2004)6, Harjanne and Tella (2009)7, and Wong and Waring (2010)8, the imbalance of the pursuit of the pedagogical and interactional purposes of conversational agendas particularly in the ELTE context create new instructional paradoxes, which include:

• When TEs say that a particular action is forbidden while interacting, yet they allow it to happen.

• When TEs have planned to complete a particular task in a certain way in line with the pedagogical and interactional purposes of their conversational agendas, yet within classroom

interaction, end up executing interactions outside of these set parameters.

• When it is assumed and stated by both parties that the classroom is a place to share knowledge (both orally and written) through great amounts of participation, yet when in class they do not act accordingly.

An initial paradox abundantly present in our research is when the students use English when they view that it is expected of them by the TE, meaning, only during class exercises. When outside the exercise or when the lesson is over, any exchange of information is reverted back to Spanish, as can be seen in the following exchange:

Sample Excerpt 10 (Content-based class, B2 Level):

(TE and Ss are installing the equipment for a presentation)

(1) S 1:¿Este? ¿Y abro acá para mirar las redes? ¿Ah, van a conectar ese? [This one? And I open by here to see what networks are? Are you going to connect that one?]

(2) S2: Es que no está en el USB. [the matter is that the file is not on the USB]

(3) TE: English

(4) S1: Ah! You are going to...

(5) S2: What?

(6) S1: Yes teacher, because we do not have a USB.

(7) S2: Dónde tiene esto el “cuchufli" del este... [Where does this PC have the cuchufli of the.]

(8) TE: What’s a "cuchufli"?

As the students attempt to display their presentation through the computer projector, their speech reverts back to Spanish given that it is not an activity outlined by the TE and given to the class to execute. It is common that students view functional interactions as an appropriate opportunity to use the L1 (Spanish). In this case, the TE initially directs students to use the L2 (English), but within moments they have reverted to Spanish once more. Subsequently, the TE does not choose to correct a second time, but redirects the interaction back into the L2 with a question in English that refers to the L1. The students go on to explain the term to the TE in the L2.

With the former paradox occurrence in mind, it is important to point out that in content-based courses, there are more instances of the students using the L2 for interactions outside of established exercises. This may be due to the fact that they are more comfortable and feel more capable with the

L2 and, by using these stronger L2 abilities, the TEs and students have been able to mutually establish new interaction patterns that readily welcome the use of the L2 in moments considered outside of the TE-structured activities. We must question whether or not this is an occurrence of the evolution of a paradox. The following example evidences this type of interaction:

Sample Excerpt 11 (Content-based class, B2 Level):

(TE and Ss are installing the equipment for a presentation)

(1) S: Teacher, what is a lecture?

(2) TE: Lecture is a false cognate, when you have to read, it is Reading, When you.

In this particular situation of a content-based class, they find themselves between activities and are organizing themselves in order to proceed to the following planned section of the class. Although many of the side interactions between groups of the recorded students have reverted to the L1, we can see here that a student begins the conversation with her TE in the L2. In interviews with this TE, she was asked specifically why this would occur. She indicated that it was an unspoken, yet "known" rule that students are only to interact with her in the L2, to the point that they found it strange to hear her speak the L1.

In this same vein, there are also instances in which the TEs, also with a ‘base rule’ of not using the L1 during the class time, renege their own rules by themselves. In the following example, a student arrives late to the class period, which is being held in the computer lab. The TE begins his interaction with him immediately in the L1:

Sample Excerpt 12 (Content-based class, B1 Level):

(TE is explainig a topic)

(1) TE: ¿No puede decir simplemente que no va a hacer nada? [Can’t you simply say that you are not going to do anything?]

(2) S: I’m waiting for a . (Points to a computer)

(3) TE: But it’s always the same with you. Listen everybody: Arrive late, and. (Unintelligible speech)(nodding his head)

We can see in this case that it is actually the student instead of the TE who initiates codeswitching to which the TE follows suit. In the previous interactions presented, we could see how the students were the agents of using the L1 outside of TE-defined classroom activities, but we see in this example that the TEs themselves may encourage this instructional paradox by reacting to comparable situations with the L1.

Likewise, also in opposition to the understood guideline of ‘no Spanish in class,’ the TEs were observed integrating the L1 into the instruction of the class when giving explanations or indications. We can see one such instance in the following example:

Sample Excerpt 13 (Content-based class, B1 Level):

(TE is explainig a topic)

(1) TE: another example, imagine that you are saying

boyfriend. What is a boyfriend?

(2) S: novio

(3) TE: Yes, and boy friend?

(4) S: amigo

(5) TE: amigo hombre...

The TE encourages the use of L1 in order for the students to better understand how inflection can change the meaning of the same word.

Yet another paradox identified in our research as put into motion by the TEs is one in which they ask for the students to provide long answers, yet in classroom discussion time with them, interject or allow short, unsubstantiated responses to which the TEs complete the students’ ideas:

Sample Excerpt 14 (Content-based class, B2 Level):

(TE and Ss are in a discussion activity)

(1) TE: and the second one is avoidance. What does it mean? Avoidance.

(2) S1: Avoidance is when.

(3) S2: A person prefers to avoid the other culture. I prefer to be with my own people. And I don’t want to be with the Asian, with the Black people and.

(4) TE: Yeah, you get isolated. You share with the people that are. have your same culture. Ok? So that is the first stage. They know that there are differences, but are not motivated about learning them. And the other is that they are isolated they avoid interacting with people with a different culture.

As we can see, the TE interrupts student 2 with her own conclusion instead of allowing him to complete the idea that he was in the process of generating. This is particularly interesting as it is an upper level content-based class where the expectation of language ability is even higher and the students should have the capacity to give expanded and well-founded answers in the L2. In the case of this instructional paradox, the TEs thwart their own classroom theory of developing in the students the ability to fully reply to prompts with complete ideas.

With the end goal being to seek a balance between TEs and students of the pedagogical and interactional purposes in ELTE classes, in the instances outlined in this article, we see where TE interactional acts do not always correspond to declared purposes. The co-construction of the space with the students is a complex matter as it involves many elements to take into account, such as the way the TEs organize the class, class activities, materials, and content. It is with the understanding of what these factors are and how they interrelate with one another where TEs should design strategies in order to attain the complete pedagogical and interactional outcomes within their interactions with students. However, TEs cannot be satisfied only with this point of view, they must go a step further and ask: (1) if these types of paradoxes are avoidable, (2) if it should be a goal that instructional paradoxes do not occur in the L2 classroom, and (3) if students become confused in terms of the objectives and overall agenda of the class because of existing paradoxes. Although we can see that in some instances the TEs themselves become a barrier to their own pedagogical and interactional purposes, at the same time there is an obvious agreement in terms of the paradoxes being that they establish interaction patterns accepted by both the TEs and students. This finding agrees with the conclusion of Tracy and Robles (2013) that participants legitimize interaction by the way they interact with each other. Both TEs and students have a hand in creating those instructional paradoxes since they mutually encourage and define their creation.

In this same line of thought, it is important to point out that in this study, these particular paradoxes were found to occur in the three observed programs for future teachers of English. Therefore, the paradoxes established, and the interactions patterns mentioned above, not only affect the students of the particular classes observed, but will leave a lasting legacy as they both will most likely be repeated in the classrooms of these soon-to-be English teachers. With this being said, our goal is not to disparage the appearance of instructional paradoxes within the ELTE classroom, but to identify their construct and the ways in which they affect classroom interaction.

Conclusions

The foremost finding in our research, considering the transactional stages, interaction patterns, conversational agendas, and instructional paradoxes, is that of the necessity of a more comprehensive understanding of the interactional process occurring in ELTE classes. The question remains, however, as to how this can be accomplished. Surely, this cannot be achieved by following an unperceived or preestablished script which would only contribute to perpetuating inauthentic interactive processes that commonly occur in ELTE classroom environments. Instead, TEs must understand the ways in which they can foster and encourage more spontaneous interaction in the classroom, nurturing a more varied set of interaction patterns, and allowing more extraordinary events to happen in class. It was noted throughout this study that TEs do not exactly encourage many opportunities for spontaneous interaction, understood as the arising of interactions with students that occur without the constraints of pre-established interactional conventions (Willis, 2015). Although interactional conventions may be seen as keeping the class on task, in our point of view it seldom fosters nor generates possibilities for spontaneous interaction as the interactional conventions of ELTE classroom interaction more often become transactional and predicted. TEs need to ask themselves how interaction should happen in ELTE classes if students are to acquire the language, knowledge, interaction, and communication skills that they will teach in the future for multiple social uses and not only for a type of transactional interaction in the L2 classroom.

With this in mind, the common perception of both TEs and students seems to be that L2 teaching and learning is understood and performed as simply a matter of mastering the L2 linguistics in the classroom setting without much reference to nor harnessing real-life contexts and the nuanced grammar and interaction that it can create. Overall, TEs stick to the common practice of working within the modes (managerial, materials, skills and systems, classroom context) in order to structure their classroom and provide the concepts they plan to teach students. This methodology of modestructuring highly contributes to the construction of particular TE-student interactions within the ELTE class, given that said modes configure how the classroom interaction should occur. Analyzing the emergent interaction patterns under the ECA and SETT approaches, we conclude that TEs become almost uncomfortable when faced with a situation that falls outside of one of the modes, and promptly (within the fewest number of turns), redirect their students back towards the predetermined interactional foci of the class.

As we observed both language-based as well as content-based classes in ELTE classes, it became clear that there was much more of a chance for interaction in the latter due to the fact that the conversation topics of the content-based classes allowed for advanced participation and longer turns of speaking. In addition, the established interaction patterns between the TEs and students in both types of classes reveal a pedagogical purpose of opening spaces for learning and practicing how to teach and correct English. This purpose is common in all the TEs’ conversational agenda. Although this agenda is also composed of interactional purposes that should be congruent with pedagogical ones, the TEs sometimes exercise contradictory interactional practices of their pedagogical purposes, usually demonstrating that they seem to have a very limited knowledge of how classroom interaction actually happens in their lessons.

References

Alvarez, J. A. (2008). Instructional sequences of English language teachers: An attempt to describe them. How Journal, 15, 29-48.

Anderson, J., Oro-Cabanas, J. M., & Varela-Zapata, J. (Eds.). (2004). Linguistic perspectives from the classroom: Language teaching in a multicultural Europe. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Spain: Unicopia Artes Gráficas, S. L.

Benwell, B., & Stokoe, E. (2006). Discourse and identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Cameron, D. (2001). Working with spoken discourse. London: SAGE Publications.

Castañeda-Peña, H. (2012). Profiling academic research on discourse studies and second language learning. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14(1), 9-27.

Castrillón-Ramírez, V A. (2010). Students’ perceptions about the development of their oral skills in an English as a foreign language teaching program (unpublished undergraduate thesis). Pereira, Colombia: Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira.

Castro-Garcés, A. Y, & López-Olivera, S. F (2013). Communication strategies used by students of different proficiency levels. How Journal, 21(1), 1025.

Cazden, C. (1986). Language in the classroom discourse. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 7, 18-33.

Cazden, C. (1988). Classroom discourse: The language of teaching and learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Consolo, D. A. (2014). Teachers' action and student oral participation in classroom interaction. In J. K. Hall & L. S. Verplaetse (Eds.), Second and foreign language learning through classroom interaction (pp. 91108). USA: Routledge.

De Mejía, A. M. (2002). Power, prestige, and bilingualism: International perspectives on elite bilingual education. UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R., & Sheen, Y (2006). Reexamining the role of recast in second language acquisition. SSLA, 28, 575-600.

Garton, S. (2002). Learner initiative in the language classroom. ELT Journal, 56(1), 47-56.

Gonzalez-Humanez, L. E., & Arias, N. (2009). Enhancing oral interaction in English as a Foreign Language through task-based learning activities. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 2(2), 1-9.

Harjanne, P, & Tella, S. (2007). Foreign language didactics, foreign language teaching and transdisciplinary affordances. In A. Koskensalo, J. Smeds, P Kaikkonen, & V Kohonen (pp. 197-225), Foreign languages and multicultural perspectives in the European context. Berlin: LITVerlag.

Hélot, C., & De Mejía, A. M. (Eds.) (2008). Forging multilingual spaces: Integrated perspectives on majority and minority bilingual education. UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Herazo-Rivera, J. D. (2010). Authentic oral interaction in the EFL class: What it means, what it does not. Profile:

Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 12(1), 47-61.

Herazo-Rivera, J. D., & Sagre-Barbosa, A. (2015). The coconstruction of participation through oral mediation in the EFL classroom. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 18(1), 149-163.

Hutch, T. (2006). Negotiating structure and culture: L2 learners' realization of L2 compliment-response sequences in talk-in-interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 38, 2025-2050.

Inan, B. (2012). A comparison of classroom interaction patterns of native and non-native EFL teachers. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 24192423.

Johnson, K. (1995). Understanding communication in second language classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kasper, G. (2009). Categories, context, and comparison in conversation analysis. In H. Nguyen & G. Kasper (Eds.), Talk-in-interaction: Multilingual perspectives (pp. 1-28). USA: National Foreign Language

Resources Center.

Kharaghani, N. (2013). Patterns of interaction in EFL classroom. Global Summit on Education, 1, 859864.

Lyster, R. (1998). Recasts, repetition, and ambiguity in L2 classroom discourse. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 20, 51-81.

Long, H. M., & Sato, C. (1983). Classroom foreigner talk discourse: Forms and functions of teachers' questions. In H. W Seliger & M. H. Long (Eds.), Classroom oriented research in second language acquisition (pp. 268-286). Cambridge: Newbury House Publishers, Inc.

Lucero, E. (2011). Code switching to know a TL equivalent of an L1 word: Request-provision-acknowledgement (RPA) sequence. How Journal, 18, 58-72.

Lucero, E. (2012). Asking about content and adding content: Two patterns of classroom interaction. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14(1), 2844.

Lucero, E. (2015). Doing research on classroom interaction: Approaches, studies, and reasons. In W. Escobar & H. Castañeda-Peña (Eds.), Studies in discourse analysis in the Colombian context (pp. 91-122). Bogotá, Colombia: Editorial Universidad El Bosque.

Markee, N. (1995). Teachers' answers to students' questions: Problematizing the issue of making meaning. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 6(2), 63-92.

McDonough, K., & Mackey, A. (Eds.). (2013). Second language interaction in diverse educational contexts. Philadelphia, USA: John Benjamins Publishing Co.

Mori, H. (2000). Error treatment at different grade levels in Japanese immersion classroom interaction. Studies in Language Sciences, 1 , 171-180.

Rashidi, N., & Rafieerad, M. (2010). Analyzing patterns of classroom interaction in EFL classrooms in Iran. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 7(3), 93-120.

Richards, J. (2008). Teaching speaking theories and methodologies. Retrieved from http://www.fltrp.com/ D0WNL0AD/0804010001.pdf.

Rymes, B. (2009). Classroom discourse analysis: A tool for critical reflection. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, Inc.

Rosado-Mendinueta, N. (2012). Contingent interaction: A case study in a Colombia EFL classroom. Zona Próxima, 17, 154-175.

Schegloff, E. (1997). Third turn repair. In G. R. Guy, C. Feagin, D. Schiffrin, & J. Baugh (Eds.), Towards a social science of language: Papers in honor of William Labov (Vol. 2): Social interaction and discourse structures (pp. 31-40). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Schegloff, E. (2000). When others initiate repair. Applied Linguistics, 21 (2), 205-243.

Seedhouse, P. (2004). The interactional architecture of the second language classroom: A conversational analysis perspective. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sinclair, J. M., & Coulthard, R. M. (1975). Towards an analysis of discourse: The English used by teachers and pupils. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tracy, K., & Robles, J. S. (2013). Everyday talk: Building and reflecting identities. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

üstunel, E., & Seedhouse, P (2005). Why that, in that language, right now? Code-switching and pedagogical focus. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 15(3), 302-325.

Van Lier, L. (1988). The classroom and the language learner. New York: Longman.

Walsh, S. (2011). Exploring classroom discourse: Language in action. NY: Routledge.

Willis, D. (2015). Conversational English: Teaching spontaneity. In M. Pawlak & E. Waniek-Klimczak (Eds.), Issues in teaching, learning and testing speaking in a second language (pp. 3-18). New York: Springer.

Wong, J., & Waring, Z. (2010). Conversation analysis and second language pedagogy: A guide for ESL/ EFL teachers. New York, NY: Routledge.

Zhang-Waring, H. (2016). Theorizing pedagogical interaction: Insights from Conversation Analysis. New York, Routledge.

This research project has received the support from Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá. Centro de Investigación en Estudios Sociales, Políticos y Educativos - CIESPE. Project code: ULS-CIESPE-2015 C01-4.

Universidad de La Salle, Bogota, Colombia. elucero@unisalle.edu.co

Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá, Colombia. meg_rouse@hotmail.com

This statement expands Seedhouse’s (2004) suggestion that participants’ conversational agenda in classroom interaction is composed of a pedagogical focus and an interactional organization.

This fact equates Benwell and Stokoe’s (2006) premise that, in institutional talk (as the language classroom is), both parties employ interactional strategies that are driven by the pedagogical and interactional purposes of their conversational agendas.

Seedhouse explains a paradox in which language teachers reassure learners that it is, "ok to make linguistic errors [but then is] contradicted by the interactional message [that] linguistic errors are terrible faux pas" and furthermore, teachers make a point to excessively correct any mistakes that learners make (p. 175).

Harjanne and Tella present a paradox in which English language teachers express that this L2 is best "taught", when it is used in communicatively-meaningful situations without teaching code-based rules, but teachers’ class situations are not communicative as such but rather grammar-based (p. 215).

Wong and Waring found a paradox of task authenticity which refers to the irony that in the language classroom the most authentic task is sometimes found in off-task talk (p. 263).

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.

.JPG)