DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.151Published:

2009-01-01Issue:

No 11, (2009)Section:

Research ArticlesThe contributions of a hispanic immigrant home reading practices to a child’s bilingual reading development

Las contribuciones de las prácticas de lectura en el hogar de una niña inmigrante hispana en su desarrollo de la lectura bilingüe

Keywords:

Prácticas de lectura en escuela y hogar, niños hispanos, programas bilingüismo en Estados Unidos, bi-alfabetismo (es).Keywords:

home-school reading practices, Hispanic young children, US bilingualism, biliteracy (en).Downloads

References

Ada, A. F., & Zubiarreta, R. (2001). Parent narratives: The cultural bridge between Latino parents and their children. In M. L. Reyes & J. J. Halcón (Eds.), The best for our children: Critical perspectives on literacy for Latino students (pp. 229-244). New York: Teachers College Press.

Armand, F. (2000). Le rôle des capacités métalinguistiques et de la compétence langagière orale dans l'apprentissage de la lecture en français langue première et seconde. Canadian Modern Language Review, 56(3), 469-495.

Bialystok, E. (1997). Effects of bilingualism and biliteracy on children's emerging concepts of print. Developmental Psychology, 33(3), 429-440

Brisk, M. E. (2006). Bilingual education: From compensatory to quality schooling. (Second ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chiappe, P., & Siegel, L. S. (1999). Phonological awareness and reading acquisition in English- and Punjabi-speaking Canadian children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 20-28.

Cisero, C. A., & Royer, J. M. (1995). The development and cross-language transfer of phonological awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 20, 275-303.

Crawford, J. (2004). Educating English learners: Language diversity in the classroom. Los Angeles, CA: Bilingual Educational Services.

Cummins, J. (1979a). Cognitive/academic language proficiency, linguistic interde-pendence, the optimum age question. Working Papers on Bilingualism, 19, 121-129.

Cummins, J. (1979b). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 49(2), 222-251.

Cummins, J. (1992). Bilingual education and English immersion: The Ramirez report in theoretical perspective. Bilingual Research Journal, 16(1&2), 91-104.

de Jong, E. J., Gort, M., & Cobb, C. D. (2005). Bilingual education within the context of English-only policies: Three districts' responses to question 2 in mas sachusetts. Educational Policy, 19 (4), 595-620.

Demont, E., & Gombert, J. E. (1996). Phonological awareness as a predictor of recoding skills and syntactic awareness as a predictor of comprehension

skills. British Journal of Educational Psychology,

, 315-332.

Durgunolu, A. Y., Nagy, W. E., & Hancin-Bhatt, B. J. (1993). Cross-language transfer of phonological awareness. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(3), 453-465.

Edelsky, C. (1982). Writing in a bilingual program: The relation of l1 and l2 texts. TESOL Quarterly, 16(2), 211-228.

Fix, M., & Passel, J. S. (2003, January 28-29). U.S. Immigration: Trends and implications for schools. Paper presented at the National Association for Bilingual Education: NCLB Implementation Institute, New Orleans, LA.

Francis, D. J., Lesaux, N. K., & August, D. (2006). Language of instruction. In D. August & T. Shanahan (Eds.), Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report fo the national literacy panel on languageminority children and youth (pp. 365-413). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gadsden, V. L. (2003). Expanding the concept of "family" in family literacy: Integrating a focus on fathers. In A. DeBruin-Parecki & B. Krol-Sinclair (Eds.), Family literacy: From theory to practice (pp. 86-125). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Gallimore, R., & Goldenberg, C. (1993). Activity settings of early literacy: Home and school factors in children's emergent literacy. In E. A. Forman, N. Minick & C. A. Stone (Eds.), Contexts for learning: Sociocultural dynamics in children's development. New York: Oxford University Press.

García, G. E. (2003). The reading comprehension development and instruction of English-language learners. In A. P. Sweet & C. E. Snow (Eds.), Rethinking reading comprehension (pp. 30-50). New York: The Guilford Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1999). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Goldenberg, C. (1987). Low-income Hispanic parents' contributions to their first-grade children's wordrecognition skills. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 18, 149-179.

Goldenberg, C., Reese, L., & Gallimore, R. (1992). Effects of literacy materials from school on Latino children's home experiences and early reading achievement. American Journal of Education, 100, 497-536.

Goldman, S. R., Reyes, M., & Varnhagen, C. K. (1984). Understanding fables in first and second languages. NABE Journal, 8(2), 35-66.

Göncz, L., & Kodzopelji, J. (1991). Exposure to two languages in the preschool period: Metalinguistic development and the acquisition of reading. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 12(3), 137-163.

González, N., Moll, L., & Amanti, C. (2005a). Introduction: Theorizing practices. In N. González, L. C. Moll & C. Amanti (Eds.), Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms (pp. 1-24). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

González, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2005b). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in house-holds, communities, and classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gort, M. (2008). "you give me idea!" Collaborative strides towards bilingualism, biliteracy, and cross-cultural understanding in a two-way partial immersion program. Multicultural Perspectives, 10(4), 192-200.

Gregory, E. (1996). Making sense of a new world: Learning to read in a second language. London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd.

Hudelson, S. (1984). Kan yu ret an rayt en ingles: Children become literate in English as a second language. TESOL Quarterly, 18(2), 221-238.

ICFES. (2006). Análisis resultados 2006. Retrieved January 20th, 2009, from http://www.icfes.gov.co

Jiménez, R. T., García, G. E., & Pearson, P. D. (1995). Three children, two languages, and strategic reading: Case studies of bilingual and monolingual readers. American Educational Research Journal, 32(1), 67-97.

Jiménez, R. T., García, G. E., & Pearson, P. D. (1996). The reading strategies of bilingual Latina/o students who are successful English readers: Opportunities and obstacles. Reading Research Quarterly, 31(1), 2-25.

Jiménez, R. T., Smith, P. H., & Martínez-León, N. (2003). Freedom and form: The language and literacy practices of two mexican schools. Reading Research Quarterly, 38(4), 488-508.

Lefrançois, P., & Armand, F. (2003). The role of phonological and syntactic awareness in second-language reading: The case of Spanish-speaking learners of French. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16, 219-246.

Lindholm-Leary, K. J. (2001). Dual-language education. Avon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Lindholm, K. J., & Aclan, Z. (1991). Bilingual proficiency as a bridge to academic achievement: Results from bilingual/immersion programs. Journal of Educational Psychology, 173 (2), 99-113.

Lindsey, K. A., Manis, F. R., & Bailey, C. E. (2003). Prediction of first-grade reading in Spanish-speaking English-language learners. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(3), 482-494.

López-Velásquez, A. M. (2008). The reading and comprehension of English and Spanish text among four Hispanic bilingual first-graders. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign.

McCarthey, S. J., García, G. E., López-Velásquez, A. M., Lin, S., & Guo, Y. (2004). Understanding writing contexts for English language learners. Research in the Teaching of English, 38(4), 351-394.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional (MEN). (2006). Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: Inglés. Formar en lenguas extranjeras: ¡el reto! Bogotá: Imprenta Nacional.

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132-141.

Moll, L. C., Sáez, R., & Dworin, J. (2001). Exploring biliteracy: Two student case examples of writing as a social practice. The Elementary School Journal, 101(435-449).

Orellana, M. F., Reynolds, J., Dorner, L., & Meza, M. (2003). In other words: Translating or "para-phrasing" as a family literacy practice in immigrant households. Reading Research Quarterly, 38(1), 12-34.

Ortiz, R. W., Stile, S., & Brown, C. (1999). Early literacy activities of fathers: Reading and writing with young children. Young Children, 54(5), 16-18.

Paratore, J. R., Homza, A., Krol-Sinclair, B., Lewis-Barrow, T., Melzi, G., Stergis, R., et al. (1995). Shifting boundaries in home and school responsibilities: The construction of home-based literacy portfolios by immigrant parents and their children. Research in the Teaching of English, 29(4), 367-389.

Pérez, B. (1998). Language, literacy, and biliteracy. In B. Pérez, T. L. McCarthy, L. J. Watahomigie, M. E. Torres-Guzmán, T. t. Dien, J. M. Chang, H. L. Smith & A. Dávila de Silva (Eds.), Sociocultural contexts of language and literacy (pp. 21-48). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pérez, B. (2004). Becoming biliterate: A study of two-way bilingual immersion education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pressley, M. (2000). What should comprehension instruction be the instruction of? In M. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 3, pp. 545-561). Mahwah, NJ.

Reese, L., & Gallimore, R. (2000). Immigrant Latino's cultural model of literacy development: An evolving perspective on home-school discontinuities. American Journal of Education, 108(2), 103-134.

Reyes, I., & Azuara, P. (2008). Emergent biliteracy in young mexican immigrant children. Reading Research Quarterly, 43(4), 374-398.

Reyes, M. L. (2001). Unleashing possibilities: Biliteracy in the primary grades. In M. L. Reyes & J. J. Halcón (Eds.), The best for our children: Critical perspectives on literacy for Latino students (pp. 96-121). New York: Teachers College Press.

Rubinstein-Avila, E. (2007). From the Dominican Republic to Drew High: What counts as literacy for Yanira Lara? Reading Research Quarterly, 42(4), 68-589.

Saunders, W. M., & Goldenberg, C. (2007). The effect of an instructional conversation on English language learners' concepts of friendship and story comprehension. In R. Horowitz (Ed.), Talking texts: How speech and writing interact in school learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schwarzer, D. (2001). Noa's ark: One child's voyage into multiliteracy. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Tharp, R. G., & Gallimore, R. (1988). Rousing minds to life: Teaching, learning, and schooling in social contexts. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Valdés, G. (1996). Con respeto: Bridging the distances between culturally diverse families and schools. New York: Teachers College Press.

Vance, C., Smith, P. H., & Murillo, L. A. (2007). Prácticas de lectoescritura en padres de familia: Influencias en el desarrollo de la lectoescritura de sus hijos.

Lectura y Vida: Revista Latinoamericana de Lectura, 28(3), 6-17.

Volk, D. (1997). Questions in lessons: Activity settings in the homes and school of two Puerto Rican kindergartners. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 28(1), 22-49.

Volk, D. (1999). The teaching and the enjoyment and being together: Sibling teaching in the family of a Puerto Rican kindergartner. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 14(1), 5-34.

Volk, D., & de Acosta, M. (2003). Reinventing texts and contexts: Syncretic literacy events in young Puerto Rican children's homes. Research in the Teaching of English, 38(1), 8-48.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2009 vol:11 nro:1 pág:7-28

Editorial

The Contributions of a Hispanic Immigrant Home Reading Practices to A Child’s Bilingual Reading Development

Las contribuciones de las prácticas de lectura en el hogar de una niña inmigrante hispana en su desarrollo de la lectura bilingüe

Ángela María López-Velásquez

Assistant Professor Undergraduate Program in English Teaching Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira, Colombia. E-mail: amlopezvelasquez@utp.edu.co

Abstract

The characteristics of the Spanish home reading practices of a US immigrant Hispanic household are studied highlighting the many connections existing between the reading practices at home and at school. This longitudinal study explores how the home and school L1 reading instruction contributed to a first-grader’s initial steps towards reading in English or biliteracy. Details of Natalia´s reading in Spanish at home and at school are presented and the relationships between the reading practices in both contexts are documented.The findings in this study remind us of the importance of strong native language literacy foundations and of the role that both home and school play in fostering high literacy levels among children.

Key Words: home-school reading practices, Hispanic young children, US bilingualism, biliteracy.

Resumen

Se estudian las características de las prácticas de lectura de un hogar de una niña inmigrante hispano-hablante y se resalta las muchas conexiones existentes entre las prácticas de lectura en el hogar y en la escuela. Este estudio longitudinal explora como la instrucción en primera lengua en el hogar y en la escuela contribuye al desarrollo inicial de la lectura en Inglés (o bialfabetismo) de una niña de primer grado. Se presentan en detalle las características de la lectura en español de Natalia en el hogar y en la escuela y se documenta las relaciones entre las prácticas de lectura en los dos contextos. Los resultados del estudio nos recuerdan de la importancia de tener fundamentos sólidos en el desarrollo del lenguaje, lectura y escritura en la primera lengua y del rol que tienen el hogar y la escuela en apoyar altos niveles de lectoescritura en los niños.

Palabras Claves: Prácticas de lectura en escuela y hogar, niños hispanos, programas bilingüismo en Estados Unidos, bi-alfabetismo

Introduction

The increasing number of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the US is currently transforming the population of American schools and gradually changing the way teachers and administrators view the education of children who speak languages other than English at home. In the year 2000, 7.1 million children in the US of ages 5-19 came from Spanish speaking homes (in 1980, this number was 3.4 million) (Fix & Passel, 2003). Traditionally, children and youth from Hispanic origin have not fared well in American schools. The underachievement of Hispanic children at school has been attributed, in part, to the cultural discontinuities or incompatibilities between the educational practices at children’s homes and those of the school. Studies have suggested that at school, the literacy practices and values of Hispanic children’s homes are seen to be irrelevant and are rendered invisible because schools tend to emphasize practices and values based on the principles of mainstream Anglo-American culture (Goldenberg, 1987; Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzalez, 1992; Valdés, 1996). A number of studies have documented the mismatch between the literacy values and practices between Hispanic homes and schools and how these mismatches impact the participants’ perceptions of students literacy learning (González, Moll, & Amanti, 2005b; Orellana, Reynolds, Dorner, & Meza, 2003; Valdés, 1996). Findings coincide in that although literacy is valued in most Hispanic homes (Gallimore & Goldenberg, 1993; Volk & de Acosta, 2003), many parents may feel uncertain as to how to support their children’s literacy at home in a way that is relevant for school, or may not perceive a clear need to intervene in what is considered to be the school’s domain. For example, Goldenberg (1987) found that Hispanic parents responded well when teachers sent notes home suggesting helping their children to learn specific skills, but they seemed to be unaware that regular and continued practice at home would improve their children’s chances of progressing in reading at school. In other cases, the mismatch has roots in what parents and teachers believe are legitimate forms of knowledge. The funds of knowledge theoretical approach for teaching and learning (González et al., 2005b; Moll et al., 1992)has contributed to viewing the practices within families from the perspective that “people are competent, they have knowledge, and their life experiences have given them that knowledge” (González et al., 2005b, p.ix). In their work, González, Moll, and Amanti (2005a) have illustrated how teachers, through a process of research in their minority students’ homes, have learned to view the families’ knowledge as legitimate forms of knowing, which they have eventually brought into their classrooms. However, the funds of knowledge work has focused largely on how Hispanic households “generate, obtain, and distribute knowledge, among other aspects of household life” (González et al., 2005a, p.5), and less specifically on the beliefs, values, and practices around literacy among Hispanic families.

Although a number of studies have documented the disconnections that exist between home and school literacy practices, other studies have explored the similarities that may exist between what Hispanic families and schools do with literacy. For example, Goldenberg (1987) documented the efforts of low-income Hispanic parents to teach their first-grade children to read by explicitly instructing them on the sounds and the names of the letters without the teacher’s prompting. Reyes and Azuara (2008) report that parents of preschool Hispanic children teach them to spell words in Spanish and English. López- Velásquez (2008) illustrated the ways in which Hispanic parents support their children’s literacy development through shared reading. A closer look at the similarities of literacy practices across home and school contexts may help us see the possibilities of home and school collaborations.

To understand the literacy instruction of Hispanic children in the US, it is important to know about the variety of ways in which linguistic assistance is provided to English-language learners (ELLs) in schools. Linguistic assistance to ELLs varies in terms of the linguistic goals, target student population, language in which literacy is developed, and language of instruction (Brisk, 2006). The most common bilingual program is the Transitional Bilingual Education (TBE), where the native language (L1) and English are used for instruction until the children’s English is considered to be good enough for full participation in a regular classroom. ELLs in TBE programs may receive instruction in both the L1 and English for up to three years before they are completely transitioned into English-only instruction. Schoolbased opportunities for children’s L1 reading development have been further constrained by the pressures from nationally-mandated reading performance levels. The No Child Left Behind Act (2002), which requires that children succeed academically in English, has pressed schools with transitional bilingual education programs to move ELLs as soon as possible into English-only instruction (Crawford, 2004). As a consequence, ELLs today are more likely to be transitioned into English-only reading instruction before they complete the three years of L1 instruction.

Counteracting the idea that learning to read in English only is the best educational choice for linguistically diverse children, studies on bilingual reading have shown that L1 literacy plays a central role in successfully learning to read in the L2. Several studies have suggested that Spa-nish- English bilinguals can use aspects of their reading knowledge across their languages (Armand, 2000; Bialystok, 1997; Chiappe & Siegel, 1999; Cisero & Royer, 1995; Demont & Gombert, 1996; Durgunoğlu, Nagy, & Hancin-Bhatt, 1993; Goldman, Reyes, & Varnhagen, 1984; Göncz & Kodzopelji, 1991; Lefrançois & Armand, 2003; Lindsey, Manis, & Bailey, 2003). Dual Language (DL) programs offer instruction in both languages throughout elementary school, and some even through middle school, and their goal is to foster strong forms of bilingualism and biliteracy by taking advantage of what children can do with literacy in their native language. Studies on Dual Language programs have reported successful reading outcomes in both languages for both ELLs and monolingual English speakers learning to read in a second language (Lindholm-Leary, 2001; Lindholm & Aclan, 1991; Pérez, 2004). Unfortunately, since most ELLs in the US are not enrolled in programs that foster the development of strong L1 reading abilities, we do not have a thorough understanding of how strong L1 reading skills may help ELLs to read in English.

With more states in the US facing the current push towards English-only instruction today (de Jong, Gort, & Cobb, 2005), the home may be one of the few contexts where Spanish-speaking children in the US receive continued exposure to L1 reading. Although in other contexts outside of the home (e.g., church) children may be exposed to and participate in social networks that are conducted primarily or partially in Spanish, the home remains the main context where children use their oral and written Spanish skills (Moll et al., 1992). Studies have shown that in Mexicandescent Hispanic families in the US, preschool bilinguals develop knowledge and metalinguistic awareness about print in both languages as they are exposed to a large variety of interactions with print at home (Reyes & Azuara, 2008). Also, the existence of a range of literacy practices within US Puerto Rican households which support the children’s developing literacy in English and in Spanish (Volk, 1999; Volk & de Acosta, 2003). Other studies have documented the positive role of Central American parents in their first-grade children acquisition of word-recognition skills (Goldenberg, 1987). Most studies on US Hispanic children home literacy has focused on Mexicanorigin (Reyes & Azuara, 2008; Valdés, 1996; Volk, 1997) and Puerto Rican-origin households (Goldenberg, Reese, & Gallimore, 1992; López- Velásquez, 2008; Orellana et al., 2003; Reese & Gallimore, 2000; Volk, 1997). Considering that the diversity of the Hispanic world is vast, little is known about the characteristics of home literacy practices of Spanish-English bilingual children from other Hispanic cultural backgrounds (Rubinstein-Avila, 2007; Schwarzer, 2001). The cultural diversity of the Hispanic peoples in the US grants the development of research that helps us understand literacy practices across the diversity of Hispanic cultures.

The purpose of this study is threefold. First, it aims at investigating the characteristics of the Spanish home reading practices of a US immigrant Hispanic household, highlighting the many connections existing between the reading practices at home and at school. Second, it seeks to explore how the home and school L1 reading instruction contributed to a first-grader’s initial steps towards reading in English (or biliteracy). Third, it aims at contributing to the currently emerging body of knowledge about home reading practices of US Hispanic young bilinguals with ancestry other than Mexican or Puerto Rican.

Theoretical Perspectives

This study draws from sociocognitive and sociocultural views of literacy, which regard the cognitive processes of literacy learning as socially based, interactive, and influenced by context (Goldenberg et al., 1992; Pérez, 1998; Tharp & Gallimore, 1988; Vygotsky, 1962, 1978). Whether learning is the product of direct instruction or informal socialization, it involves “a caregiver [engaging] in a collaborative enterprise with the most profound implications for the development of a participating child” (Tharp & Gallimore, 1988, p. 28). This collaborative enterprise or “assisted performance” defines what a child is capable of doing when helped by more knowledgeable others. Through assisted performance children develop their cognition. Tharp & Gallimore (1988) explain that children’s acquisition of knowledge is embedded in “activity settings”, or the who, what, when, where, and why of learning situations. Examining the activity settings of literacy allows us to see the resources that participants use to create and shape experiences with literacy.

The interdependence of literacy-related abilities across languages (Cummins, 1992), and the concept of biliteracy, are central to the present study. For bilingually developing children, the knowledge they acquire in the L1 can also be available in the L2 (Cummins, 1979a, 1979b). Studies on bilingual reading have supported the interdependence theory by showing that bilinguals can use their L1 phonemic and syntactic awareness knowledge when they read in the L2 (Armand, 2000; Chiappe & Siegel, 1999; Durgunoğlu et al., 1993; Lefrançois & Armand, 2003; Lindsey et al., 2003). The transfer of reading strategies across two languages is dependent upon the bilingual child’s understanding of the purpose of reading and the relationship between his/her languages (Jiménez, García, & Pearson, 1995; Jiménez, García, & Pearson, 1996). The findings of Jiménez and his colleagues suggest that as children develop bilingualism and biliteracy, they can use their knowledge of L1 reading to read in the L2 if they understand or perceive their L1 as a resource to help them read in the L2.

The development of literacy in two languages, or biliteracy, is a central concept in this study. A growing number of studies have documented Hispanic bilingual children using their knowledge of the two languages to nurture biliteracy (Edelsky, 1982; Gort, 2008; Hudelson, 1984; Moll, Sáez, & Dworin, 2001; Reyes, 2001). The findings portrayed by these studies challenge the notion that Spanish hinders the acquisition of English and the development of literacy, and provide evidence to support the idea that when children have opportunities to acquire literacy in a language for which they have background knowledge, they have meaning-making advantages that will assist them later to explore English literacy (Pérez, 1998). Evidence of this premise is found in Reyes (2001) who documented how Spanish-dominant bilingual children initiated their path towards English literacy spontaneously. That is, they used their literacy knowledge of Spanish, acquired through formal instruction, to learn to read and write in English. Reyes (2001) proposes that a learning environment that fosters and nurtures children’s cultural and linguistic resources benefits both the bicultural identity of children and their development of abilities in both languages. Reyes’ (2001) concept of spontaneous biliteracy, and the notion that a strong L1 provides advantages to young bilinguals for the exploration of L2 literacy are highly relevant in this study.

This study used qualitative methods, sociocultural views of literacy, bilingual theory, and biliteracy to describe Natalia’s [1] L1 reading opportunities at home and at school and the influences of these opportunities on her attempts for biliteracy. The following questions guided the inquiry: 1) What are the characterisitics of Natalia’s school and home native language reading? 2) How have Natalia’s L1 reading experiences shaped her understanding of reading? 3) How have her L1 reading experiences influenced her biliteracy development?

Methodology

Context

Natalia lives in a predominantly Puerto Rican inner-city community in the US East Coast. In recent years, the community also has received a large number of immigrants from Central and South America. Many children in the community speak Spanish at home, and others live in homes where English is the dominant language. Natalia and her parents communicate exclusively in Spanish at home. Natalia’s family emigrated from Uruguay when Natalia was 4 years old. The family lives in a one-bedroom apartment, 4 blocks away from Marco Elementary School.

During kindergarten and first grade, Natalia was enrolled in a TBE program striving to become a DL program. The goal of the school at the time of the study was to incorporate formal Spanish instruction from kindergarten through fifth grade so that all children could become bilingual and biliterate. As part of the DL program plan, in first grade, one classroom provided instruction in Spanish to Spanish-dominant children, and in English to English-dominant children. Once or twice per week the Spanish-speaking children switched classrooms with the English-dominant children to receive science or social studies instruction in the second language, thus providing opportunities to the Spanish-dominant children to learn English, and to the English-dominant children to learn Spanish.

Participants

Natalia, her parents Juana and Arturo, and Natalia’s teacher, Ms. Méndez, gave consent to participate in this study. Juana, Arturo, and Natalia left Uruguay for the US two years ago. In Uruguay, Juana completed all but one high school grades. Arturo went to a vocational school, learned a trade, and worked in maintenance for several years before they arrived in the US. Their tight work schedules have deterred Juana and Arturo to pursue additional education in the US. Arturo works as a carpenter in a factory and Juana works cleaning houses, banks, and doctor’s offices. In conversations with Juana and Arturo, they reported that their families highly valued reading, and that they and their parents often read magazines and books. According to their reports, it was not uncommon to have discussions with family members about the stories read on magazines such as “Selecciones”, the Spanish version of Reader’s Digest.

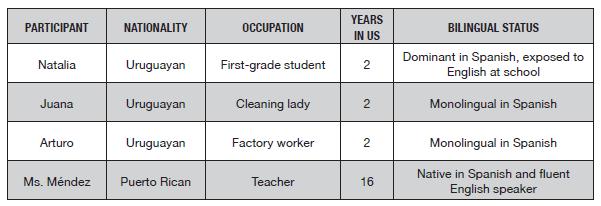

Ms. Méndez is from Puerto Rico, and has been teaching for 16 years mainly in elementary bilingual programs in the US. Spanish is Ms. Méndez’s first language, and she speaks English as a second language. (See Table 1 for the participants’ nationality, occupation, and years in the US)

Data Sources and Analysis

From September through July, I spent one day every two weeks observing Natalia during Spanish school reading lessons and during her time in the English classroom. I collected a total of 20 observations of Spanish reading lessons (20 hours) and 10 observations of the lessons Natalia received in the English classroom (5 hours). Observations were documented in the form of field notes. I conducted two semi-structured, open-ended interviews with Natalia (40minutes each) where I asked her questions about her reading at school and at home. I interviewed Juana and Arturo together once (120 minutes) and had many informal interviews with Juana. At the end of the school year, I conducted one semistructured, open-ended interview with Natalia’s Spanish teacher to find out her views on Natalia’s reading development. All interviews were taperecorded and transcribed for analysis.

To collect data on Natalia’s home reading, I asked Juana and Arturo to record their reading sessions with Natalia at home. I provided them with a tape recorder and asked them to record any moment in which they read with Natalia. Juana recorded 5 sessions reading books with Natalia for an average of 30 minutes each. Arturo recorded 4 book reading sessions for an average of 40 minutes each. A total of 9 home reading sessions (630 minutes) were transcribed for analysis. The parents reported that besides books, Natalia often read texts such as church handouts, magazines, and that she paid attention to the text printed on the mail. However, when Natalia read with her parents, they almost exclusively read books.

In looking for the influences on Natalia’s understanding of her biliteracy development, I constantly focused on the literacy opportunities available to Natalia at home and at school and the characteristics of these opportunities. I used the constant comparative method (Glaser & Strauss, 1999) to analyze observations, interviews, and family reading sessions in order to develop an understanding of the literacy opportunities available to Natalia in each context, how they were presented to her, and how she responded to these opportunities. I relied on the constant comparative method to identify consistent tendencies related to reading as they emerged from the data. In order to determine Natalia’s understanding of herself as a person developing biliteracy, I paid special attention to the literacy opportunities initiated by Natalia, and integrated them into the analysis. I constantly compared the information gathered through the different methods (i.e., observations, interviews, recordings) to check for consistency and expose contradictory data.

Findings

“Tiene que hablar inglés, pero no

queremos que pierda nuestro idioma”

: Natalia’s Parents Decisions about

Bilingualism and Early Biliteracy

Natalia’s parents highly value bilingualism and biliteracy. Both believe that in order to be successful in the US, a bilingual person should be both bilingual and biliterate. Arturo expressed, “los dos idiomas, fuertes, son una base para el futuro…que se haga entender en inglés y en español, la comunicación con la cultura. Pero que tenga los dos idiomas y fuertes” (“both languages, strong, are the basis for the future…that she can communicate in English and Spanish, the communication with the culture. But she has to have both languages, and both strong”).When Juana and Arturo heard that the program at Marco School offered instruction in Spanish from kindergarten through third grade, with some time in English, they had no doubts about enrolling Natalia there. They were afraid that Natalia would lose her Spanish if she was placed in an Englishonly setting at her young age. Juana mentioned that tensions rose between her and her friends when discussing their choices for their children’s school placement: “Mis amigos querían que yo metiera a Natalia a sólo inglés. Ellos tienen una hija que cuando llegó tenía 10 años y ya tenía su español muy fuerte. Eso es diferente. A Natalia no le pasaría lo mismo.” (My friends wanted me to place Natalia in an English-only classroom. They have a daughter who came here when she was 10, but her Spanish was already strong. That’s different. Natalia’s case would not be the same.). Both Juana and Arturo agree on the importance of maintaining Natalia’s ties to their culture: “No queremos que pierda nuestra cultura. Este país es el que nos dá de comer, así que tiene que hablar inglés, pero no queremos que pierda nuestro idioma.” (We don’t want her to lose our culture. This is the country that feeds us, so she has to speak English, but we don’t want her to lose our language).

Although convinced that most instruction in Spanish was the best for Natalia at this time of her life, Juana and Arturo also expressed their worries about her future, when Natalia was removed from Spanish instruction and placed in an all-English classroom. The parents’ biggest concern was that they would be unable to help Natalia at home with her English reading. They were told that Natalia would receive some instruction in academic English every week during first grade in the bilingual program. In the first interview, which took place at the beginning of first grade, Juana and Arturo were reassured by the school principal that Natalia would be able to learn English through the constant contact with the Englishspeaking children and through the subjects taught in English. Juana said “mi mayor preocupación es que llegue a tercer grado y no entienda nada” (my biggest worry is that she reaches third grade and that she doesn’t understand anything). Despite their worries concerning Natalia’s future English-only instruction, Juana and Arturo were happy that Natalia was receiving Spanish reading instruction in first grade at school, and kept supporting Natalia’s Spanish reading at home. Their motivation to foster Natalia’s skills in Spanish did not falter despite their fear that a lack of emphasis on English instruction would hinder Natalia’s English language learning.

Spanish Book Reading and Reading

Together: A Valued Literacy Activity

at Natalia’s Home

Reading books with Natalia was an important activity to which Juana and Arturo dedicated daily chunks of time at home. A bookshelf with more than 50 children’s books was a salient part of Natalia’s home living room, which the family refers to as “la biblioteca de Natalia” (Natalia’s library). The family shared with me many children’s books that they brought from Uruguay, to which Natalia was strongly attached. Juana and Arturo believed that keeping the books may bring comfort to Natalia as she would have something familiar in her new environment.

During first grade, Natalia’s parents read children’s books with Natalia on a daily basis. With little time between jobs to spend as a family, Juana and Arturo prioritized reading with Natalia as one of their most important daily family activities. As a routine, Juana read with Natalia during the day and with Arturo at night. Juana and Arturo often visited the local library with Natalia, where she chose the children’s books she wanted to read. The local library had a collection of Spanish children’s books, which Natalia had read almost entirely. Ms. Méndez reported that Natalia brought library books to the classroom that were related to the topic they were studying at the moment. Natalia reread her own books often and memorized some of them. Besides reading children’s books, reading at Natalia’s home also included reading “para completar la tarea” [to get homework done], which encompassed reading the booklets from the school’s reading program. Home reading also involved a diversity of printed materials such as bible chapters, songs from the church (printed on handouts available during religious service), advertisement brochures, print on supermarket products, Spanish Reader’s Digest, etc.

Although Natalia read a diversity of texts at home, “reading” in her household was understood as “shared book reading”, and activity where typically one of the parents joined Natalia to read a book. During reading time, Natalia sat next to her mother or father, listened to them read or read herself, and was constantly asked questions about the text and given information by one of the adult readers. Natalia’s home reading in Spanish usually had an evident educative purpose. Whether it was for learning new words, for practicing fluency, or for expanding Natalia’s knowledge of the world, reading at home always had some taste of formal school reading instruction.

Parents’ Different Reading Styles Support

Natalia’s Spanish Literacy and Academic

Development

Natalia’s home reading during first grade took place with each one of her parents. Each parent supported Natalia’s comprehension and enjoyment of the books in different ways. In the home reading sessions with Natalia, each parent emphasized skills that ranged from basic decoding, vocabulary explanation, to high levels of analysis. The emphases provided by each parent exposed Natalia to different aspects or reading, influencing Natalia’s Spanish reading abilities and her definition of reading.

Father-Child Shared Reading

as an Opportunity to Raise “Interrogantes”.

Several aspects characterized the moments when Arturo read at home with Natalia. For example, Arturo always listened to Natalia read, and only intervened to read words that Natalia could not. When reading a new book, Arturo asked Natalia to read the title and to start reading from the first page. The most salient aspect in Arturo’s reading style when reading with Natalia was the questions (“interrogantes”) he often formulated. Most questions raised by Arturo’s reading sessions with Natalia elicited analysis of the information in the text. These analytical questions were present in all of Arturo’s recorded reading sessions with Natalia. The following excerpt illustrates the questions that Arturo asks Natalia while reading Dinosaurios (Editorial Sigmar, 1993):

Natalia: “Abre tus ojos dinosaurios. Estegosaurio. Los dinosaurios vivieron hace mucho tiempo, antes de que aparezca el hombre los que hoy se saben de ellos es...es perro los restos...[Open your eyes, dinosaurs. Estegosaur. Dinosaurs lived long time ago, before men existed. Men know about dinosaurs today because of the remains…]

Arturo: Es por...[ because…(helping N with word)]

Natalia: “Es por los restos fosiles haiyados...(en silencio)...u un...[it’s because the fossils found… (silence) a…]

Arturo: Bueno, acá va la pregunta. Espera. Vamos por acá, por los restos de los fósiles hallados, ¿no? [Ok, here goes the question. Wait. We’re reading here, because of the fossils they found, right?]

Natalia: Uh-huh. Arturo: ¿Entonces, cómo descubre el hombre que nunca los vió a los dinosaurios? ¿Cómo los encontró el hombre? [So, how do men discover the dinosaurs, if they never saw them? How did men find them?]

Natalia: Escarbando tierra. [Scratching dirt]

Arturo: ¡Muy bien! entonces empezó a encontrar los huesitos de los dinosaurios, y los empezó a armar. ¿Y después? [Very well! So, they started to find little dinosaur bones and started to put them together. What happened next?]

Natalia: Y los llevó al ...los llevó al museo. [He took them to…to the museum.]

Arturo: ¿Si? A los museos. Muy bien. Para que los.... [Really? To the museums. Good. So that…]

Natalia: Los viera todo el mundo. [everybody could see them.]

Arturo usually listened to Natalia read and did not intervene to correct her reading of a word, unless her reading could have compromised the meaning of the text. For instance, when Natalia read the word “por” (for) as “perro” (dog), Arturo provides the correct word. Arturo announces the analysis of the text by saying “Bueno, acá va la pregunta” (Ok, here goes the question). With the introduction of his upcoming analytical question, Arturo seems to signal to Natalia that she should get ready to think. His question “¿Cómo descubre el hombre que nunca los vió a los dinosaurios?” (How do men discover the dinosaurs, if they never saw them?) requires that Natalia think beyond the information presented on the text she had read so far. Her response “escarbando tierra” (scratching dirt) indicates that she has some previous knowledge about how we came to know about dinosaurs. Natalia once mentioned to me that in kindergarten she had been to a dinosaur museum with her teacher and classmates. Aware of her daughter’s previous knowledge of dinosaurs and museums, Arturo’s questions helped Natalia to connect the text to her real-world experience.

Arturo’s pervasive use of analytical questions when reading with Natalia seems to be a practice rooted in his beliefs about the role of parents in teaching to their children. At this stage of Natalia’s reading development, Arturo’s strong emphasis on analysis, and the lack of emphasis on correcting Natalia’s miscues, reflect Arturo’s belief that the main purpose of reading to children is to generate questions and curiosity about the world. Talking about parent-child reading, Arturo commented:

Es despertarle un interrogante, porque niño que no tiene interrogantes no tiene acción de poderse superar, nunca tiene un pregunta sobre algo […] [por ejemplo, si ella lee] “el sol”…¿por qué sale el sol? El sol nace, da la luz, la luz da vida, o sea que si no hubiera sol, si fuera siempre noche no habría plantas porque habría frío […] ¿Por qué ese clavo se clava? y ¿que acción hace ese clavo, supongamos, en este mueble? Para que el mueble no se desarme.

[It’s like awakening a question to the child, because children who don’t have questions are children who don’t have the power to better themselves. They’d never have a question about anything […][for instance, if she reads ] “the sun”... Why does the sun come out? The sun raises, gives light, light gives life, so, if there wasn’t any sunlight, if it was always night we wouldn’t have plants because it would always be cold […] Why do you hammer that nail? And what is the action that nail does, say, in that chair? It’s so that the chair doesn’t come apart].

While Arturo’s views of reading with children emphasized the importance of asking questions to the child that makes them learn about their world, Juana’s approach to reading with Natalia often reflected a more traditional way to teach reading; one that emphasizes accurate decoding and word-meaning.

Mother-Child Shared Reading as an

Opportunity to Assist the Mastery of Oral

Reading and to Learn the Meaning of Words.

Unlike Arturo’s focus on reading to ask questions, Juana emphasized Natalia’s accurate reading of words and punctuation, as well as the meaning of words in the text. Although Arturo also discussed word meaning with Natalia, this practice was much more pervasive when Juana and Natalia read together. Such emphasis may be rooted in Juana’s views of what makes a good reader. She found reading aloud enjoyable, especially when reading text that required expression: “yo siempre leí en voz alta, y me fascina leer en voz alta y me fascina leer con los puntos de interrogación, me encanta leerle a ella...yo no le hago tantas preguntas como Arturo. Cuando tengo libros difíciles se los leo yo.” (I always read out loud, and I love to read out loud, and I love to read with question marks, I love to read to her…I don’t ask her as many questions as Arturo does. When I have difficult books, I read them to her.) This view about reading seemed to be reflected in the books that Juana and Natalia chose to read together at home. In most of the home session recordings where Juana read with Natalia, fairy tales (e.g., Cenicienta), and poetry (e.g., Abecedario de Animales, Ada & Escrivá, 1990) were read. As Juana mentioned, her reading style emphasized reading aloud enthusiastically. When Juana read to Natalia, they seemed to enjoy their reading time. Juana read with enthusiasm, and Natalia listened and looked at the text and the pictures. Juana invited Natalia to participate by asking her questions about the illustrations or the message of the text. A feeling of enjoyment and relaxation seemed to be often present when Juana read to Natalia at home. While reading Abecedario de Animales (Ada & Escrivá, 1990), Juana and Natalia’s reading illustrates these characteristics:

Juana: Muy bien, muy bien Natalia. Bueno, esto es un librito que es abecedario de animales. Mamita te lo va a empezar y ¿qué letra es esta? [Very well,

Natalia. Ok, this is a book called Animal Alphabet. Mom is going to start reading it to you. What letter is this one?]

Natalia: AAAAA!

Juana: A, muy bien. “La A es la letra primera. Dice abeja, avispa, ardilla, también abuela y avión. Dice azúcar, agua y aire, y también nos dice adiós. La a es la primera letra, así empieza la lección. Abejita laboriosa. Abejita laboriosa, ¿qué tienes en tu panal? Rica miel y blanca cera, mira hermanita obrera, y una reina, mi mamá.” ¿Y esta qué letra es? [A, very well. [Text (author’s translation): “A is the first letter. It says abeja, avispa, ardilla, and also abuela and avion. It says azúcar, agua and aire, and it also says adios. A is the first letter, and so starts our lesson….” What letter is this?]

Natalia: ¡Beeee!

Juana’s statement that she did not ask as many questions as Arturo when reading with Natalia was contradicted by the data. As a matter of fact, Juana asked many questions to Natalia, but her questions were of a different nature than Arturo’s. Juana’s questions revolved around the meaning of words and accurate punctuation. Often, Juana explained the meaning of a word or expanded Natalia’s definition of a word by explaining the use of the word in different situations. Juana’s emphases on word meaning and punctuation are illustrated by the following examples, where they are reading a booklet with a summarized version of the fairy tale “Cenicienta”:

Natalia: “La vida de sin...cenicienta se hizo invisible.” [N reads text. She reads “invisible” (invisible) for “invivible” (unbearable)]

Juana: Ahí no dice invisible. Invi [it doesn’t say “invisible”. Invi]

Natalia: “Invivible”

Juana: Muy bien. [Very well] Natalia: “Desde que su papá se volvió a casar cada nueva hermana era mandoona y horrible y todo el día si cenicienta tenia que limpiar y limpiar.” [N keeps reading text. The word “mandona” (bossy) is in the text]

Juana: Espera. Antes de pasar a otra página decime, ¿vos sabés lo que es mandona? [Wait. Before going to the next page, tell me, do you know what “bossy” means?]

Natalia: Si. Algo que las hermanas le mandan a hacer. [Yes. Something that her sisters order her to do.]

Juana: “Mandona” es una persona que te manda a hacer muchas cosas. Muy bien. Y no necesariamente puede ser una hermana, puede ser una madre mandona, una amiga mandona....[chuckles] [“Bossy” is a person that orders you to do many things. Very well. And it doesn’t have to be a sister necessarily, it can be a bossy mother, a bossy friend… [chuckles]

Natalia: [chuckles] Juana: ¿Tu tienes una mamá mandona? [Do you have a bossy mother?]

Natalia: No [insegura] No mucho, ¡cuando me hace tender las camas! [no [unsure] No, not much, when she makes me make the beds!]

Juana: ¿Y vos sabés lo que dice esta palabra que viste? ¿Que no podías pronunciar bien?, que dice in-vi...[ and do you really know what this word means, the one you couldn’t pronounce well, that says “invi…”]

Natalia: ¡No lo se! [con tono de impaciencia] [I don’t know! (impatiently)]

Juana: Invivible. Es algo que ya no se puede vivir. Es algo que tu dices ay, ya se volvió que ya no se puede vivir. Que es algo que es feo de vivir. Entonces que se hizo insoportable. Invivible. Como dices tu, es la palabra que usan los adultos [chuckles]. “la vida de cenicienta se hizo invivible” [emphasis on “invivible”]. ¿Sabés lo que es cuando alguien se vuelve a casar? ¿Qué significa casarse? [“invivible”. It’s something that cannot be lived anymore. It’s something that you say, this is unbearable. It’s something ugly to live. So, that it became unbearable. “Invivible”. Like you say, it’s a word used by the adults [chuckles]. [J reads] “La vida de Cenicienta se hizo invivible” [emphasis on “invivible”]. Do you know what it jeans when someone remarries? What does “to get married” mean?]

This excerpt illustrates Juana’s tendency to often ask Natalia for the meaning of words during a reading session. Notice that when Juana explains the meaning of words to Natalia, she is very thorough in her explanations. The data suggests that vocabulary building seems to be an important contribution of reading for Juana. When Natalia read, Juana usually made use of every opportunity to emphasize Natalia’s accurate reading of words, fluency, accurate punctuation and intonation. For example, Juana frequently reminded Natalia about how to read punctuation. Reminders such as “¿cuando hay punto, qué hay que hacer?” (What do you have to do when there is a period?), “¿cuando hay coma, que hacés? (What do you do when there’s a comma?) “¿cuando hay un signo así (makes sign with her hand) qué significa? ¿signo de qué?” (When there is a mark like this, what does that mean? What mark?), were common in all home reading sessions between Natalia and her mother. In addition, Juana either directly corrected Natalia’s miscues or tried to make Natalia aware of her miscues by asking her to read again. When Natalia read a sentence that sounded too choppy, Juana made her reread the same sentence several times, until Natalia read the sentence fluently. Sometimes, Juana’s overcorrection seemed to cause frustration to Natalia, which she expressed by being reluctant to read and by getting upset with Juana. After Juana had made Natalia reread many times, Natalia signaled her frustration by continuing reading without listening to her mother’s comments. Juana continuously evaluates Natalie’s reading, signaling her emphasis for Natalia’s mastery of decoding. By making remarks, Juana demands Natalia to repair miscues, and to remember what needs to be done to read punctuation correctly.

Reading with both parents in Spanish seems to have greatly influenced Natalia’s understanding of reading and her perceptions of herself as a reader. Natalia expressed her love for reading by emphasizing her love for knowing the meaning of words:

(I=Interviewer)

I: Cuéntame, ¿cuánto te gusta leer? (Tell me how much do you like reading) N: Mucho. (A lot)

I: ¿Mucho? ¿Y por qué te gusta leer tanto. (A lot? And why do you like reading so much?)

N: Por que a mi me gusta leer, porque a mi me gustan las palabras (Becasue I like to read because I like words)

I: ¿Cómo que te gustan las palabras?, explícame eso. (What do you mean you like words? Tell me more about that.)

N: Por lo que quieren decir (For what they mean)

I: ¿Tienes un ejemplo? Hay ahí alguna palabra que te parezca bonita por lo que quiere decir? (Do you have an example? Is it there a word that you consider beautiful for what it means?) N: Que los relojes hace “tic, tac, tic, tac” (That clocks go tic, tac, tic, tac)

Natalia also seemed to notice the differences between her mother’s and father’s reading styles. She reported: “mi mamá me dice ‘¿qué tu entendiste?’ y mi papá a veces no me dice nada y yo sigo leyendo porque mi papá me lo dice a lo último todo lo que entendí del libro...a mi papá no le gusta leer solo...solo a mi mamá. Mi papá me escucha leer a mi.” (My mom says to me: “what did you understand?”, and my dad sometimes doesn’t say anything and I keep reading because my dad asks me at the end for what I understood from the book…my dad doesn’t like to read by himself…my mom does. [My dad] listens to me reading.) When asked about what style she likes the most, Natalia reported that she likes reading with both parents.

Reading Practices at School: Commonalities with Home Reading

Literacy instruction at Ms. Méndez’s classroom was exclusively in Spanish and occurred twice a day: In the morning, the children received 90 minutes of structured reading instruction (emphasizing decoding and fluency) and in the afternoon the reading instruction emphasized the acquisition of information from books. The interactions around text that occurred in Ms. Méndez in the classroom shared important similarities to those at Natalia’s home (See Table 2 for characteristics between home and school reading practices).

The morning reading had many similarities to the instruction that Juana routinely provided Natalia at home. For example, like Juana, Ms. Méndez emphasized the use of punctuation in the children’s oral reading as an important aspect of reading fluently. In these discussions, Natalia was often ready to respond. The following excerpt from the field notes depicts a discussion taking place between Ms. Méndez and the children about reading with fluency, as they read a book together.

[The children are reading from a book. The text says: “sapito (little frog)”. The children read “sapo” (frog)]

Ms. M: La palabra “sapo” tiene sentido. Pero esa no era la palabra en el texto. Cuando leo con fluidez leo con corrección. ¿Qué tengo que tener para leer con fluidez? (The word “sapo” makes sense. But that is not the word on the text. When I read with fluency, I read with correction. What do I have to do to read with fluency?)

Girl: Con corrección.(with correction)

Ms. M: ¿Y qué es eso? (and what’s does that mean?) Boy: Rapidez. (quickly) (Ms. Méndez takes the book and reads one paragraph rapidly, making it difficult for children to follow)

Ms. M.: ¿Eso es fluidez? (is that fluency?)

Natalia: ¡No! ¡Tienes que parar en los puntos! (No! You have to stop on the periods!)

Ms. M: ¿Qué más tengo que hacer? (What else do I have to do?)

Girl: Entonación. Cuando hay signos de pregunta. (Intonation. When there are question marks.)

Natalia: O de los puntos. (Or the periods) (Indicates with hand gestures an exclamation mark)

Ms. M: Eso tiene un nombre. (That has a name.)

Natalia: hmmmm…

Ms. M: Signos de admiración. ¿Que más? (Exclamation marks. What else?)

Boy: Expresión. (Expression.)

Ms. M: No leo como un robot. (I shouldn’t read like a robot.)

During the last 20 minutes of the morning reading instruction, Ms. Méndez led the children to the classroom carpeted area to read a book to them. During this time, Ms. Méndez emphasized the instruction of comprehension strategies (e.g., looking at the pictures for clues about the story, making predictions, thinking about what is being read), story grammar components (characters, setting, problem, solution), comprehension of the story, new vocabulary, and connections that the children could make between the story and other stories or life experiences. The interactions that occurred during this time resembled those Natalia had with her father at home.

[Ms. Méndez shows the children a book called “¡Agarren esa Gata!” (Catch that cat!). There is a chart on the board divided into the following columns: predictions, vocabulary, comprehension, interpretation, connections, and retelling. The title of the book, author and illustrator’s names are written in big letters and posted on top of the chart for the children to see]

Ms. M: Cada equipo va a pensar en una predicción. ¿Por qué tienen que agarrar esa gata? (Each team is going to think about a prediction. Why do they want to catch that cat?) [Natalia is in a team with other two children. They discuss their predictions as a group]

Natalia: Yo creo que la gata se fue de la casa…(I think that the cat escaped from the house)

Ms. Méndez: Un momento. [To the whole group]. ¿Qué es una predicción? (Hold on. What’s a prediction?)

Natalia: Cuando pensamos del cuento qué va a pasar. (When we think about the story, about what’s going to happen)

[Ms. Méndez confirms and expands. Children continue discussing their predictions for 2 minutes]

Ms. Méndez: Ahora vamos a escuchar al grupo [de Natalia]. (Now we’re going to listen to Natalia’s group)

Girl: Mi equipo me dijo que la historia es sobre una gatita que se perdió y unos niños la están buscando. (My team told me that the store is about a kitten who got lost and children are looking for her) [Other groups share their predictions.

Ms. Méndez writes their ideas under the column “predictions”]

Ms. M: En el cuento voy a buscar estas palabras… ¿Qué es perseguir? (I’m going to look for these words in the story…what is to chase?)

Natalia: Cuando alguien está caminando en fila y el que está atrás lo sigue. (When someone is walking in line and the one behind is following her) [Ms. Méndez expands Natalia’s answer. She discusses more words with the kids]

Ms. M: Voy a pensar en otras palabras que yo creo están relacionadas con el cuento. (I’m going to think about other words that I think are related to the story.)

In this excerpt, Natalia’s participation is frequent and her contributions are accurate. Because Natalia was used to these types of interactions around text from her home literacy experience, it is not surprising that she was able to actively participate in these reading activities. Ms. Méndez knew Natalia’s parents, and she was aware of the support that Natalia received at home in Spanish reading. “Tengo entendido que ella comparte, y trae muchos libritos libros extras que no tiene nada que ver con [los libros del programa de lectura] y ni son la biblioteca de la escuela. Así que sus papás le facilitan otros libros para tenerlos en la casa.” (In understand that she shares and brings many books that are neither [books from the school reading program] or school library books. Her parents give her access to other books to keep at home). Ms. Méndez seemed to appreciate the efforts that Natalia’s parents made in order to support Natalia with reading.

Estuvimos hace poco trabajando para la celebración del cumpleaños de Dr. Seuss y sus papás le facilitaron a ella unos tres libros de Dr. Seuss. Los leímos en el salón, los anotamos en un cartel y ella pues se sintió muy orgullosa de esa participación. […] yo creo que en la casa buscan la manera de fortalecer el trabajo que se hace con ella.

[Some time ago we planning the celebration of Dr. Seuss’s birthday, and her parents got her three Dr. Seuss books. We read them in the classroom, we wrote the titles in our board, and she felt very proud of that participation […] I think that at home they look for ways to strengthen the work that I do with her].

Natalia’s First Attempts at Reading in English

At the beginning of first grade, Natalia’s parents reported that her book choices were always Spanish books. They said that Natalia preferred to read books in Spanish because “en inglés no los sabe leer” (she doesn’t know how to read them in English). All of the books that Natalia checked out from the library were Spanish books. She did have some books in English at home that were gifted to her by the school or by the local church. However, her parents reported that so far, she always gravitated towards choosing books in Spanish.

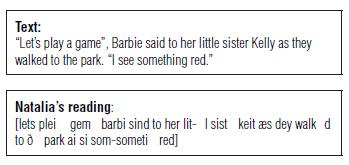

As I collected the data on Natalia at school every week, I had opportunities to see her interacting with her peers in the Spanish classroom. In the middle of the year, I started noticing that Natalia would speak to her peers using some English words. Most of her classmates were Puerto Rican, and some of them spoke English. One day, Natalia approached me after an observation and said to me: “ayer leí un libro de Barbie en inglés” (I read a Barbie book in English yesterday). This was a critical point in my data collection. So far, I have known Natalia as a monolingual child, who only read Spanish books at home and at school. Natalia’s parents also identified her as a monolingual reader. But that day, she declared herself a bilingual reader, and I could not miss the opportunity to gather more data on the experience she was reporting to me. That same day, I called Juana to arrange an interview with Natalia. The following is the excerpt of the interview where Natalia tells me about her very first attempt at reading English by herself:

(I=Interviewer)

I: ¿Cómo fue que leíste [ese libro] en inglés? (How did you read [this book] in English?)

N: Veía las palabras […] Yo estaba apuntado con el dedo y mirando las palabras y diciéndolas. (I looked at the words […] I was pointing with my finger and looking at the words and saying them)

I: Mientras tu estás leyendo estas cosas Natalia, ¿qué está pasando por tu mente? ¿Cómo es que tú eres capaz de leer estas cosas? ¿Cómo es que eres capaz de leer en un idioma que tu no hablas todavía? (While you’re reading, Natalia, what is crossing your mind? How are you able to read this text in a language that you still don’t speak?)

N: Traduzco las palabras y después decirlas (I translate the words and then I say them)

I: ¿Cómo haces para leer esta palabra, por ejemplo? (How do you read this word, for instance?)

N: /lets/

I: Cuéntame que hiciste para ser capaz de leer esta palabra. (Tell me what you did in order to read this word)

N: La puedo decir por letra (I can say it letter by letter)

I: ¿Cómo es eso? Muéstrame. (How’s that? Show me)

N: /l/ /e/ /t/ /s/ (reads each sound separately)

I: ¿O sea que tú piensas en el nombre de la letra o en el sonido? (So, you think about the name of the letter or the sound?) N: El sonido (the sound)

Pointing with the finger at the words while reading is a practice highly emphasized by Ms. Méndez at school. Natalia’s report suggests that she has internalized this practice, as she used it to approach the English text. However, Natalia’s report about translating while reading was not a school practice. As a matter of fact, any relationships that may exist between English and Spanish--such as similar sounds or cognates— were never mentioned to the children at school during reading instruction. It is likely that Natalia has experienced translation of text at home, as her parents figure out the meaning of English text in their everyday lives, and that she has transferred this practice to reading her own books.

Natalia’s description of her reading in English reveals her acquired symbol-sound correspondence and her understanding that she can use the skills she has in Spanish to figure out reading in a language that she does not yet speak. An analysis of the strategies she used to “read” a passage of the Barbie book shows that in order to read English, Natalia mostly uses her knowledge of Spanish phonology and of some English sight words. In addition, the analysis portrays the way in which she is beginning to internalize some English sounds. These aspects characterize Natalia’s first steps into reading English. The text Natalia read during this interview is a sentence from the Barbie book she read by herself. Natalia’s actual reading of that sentence is provided in the phonetic symbols that most closely represent the sounds she used.

In the words “play”, “see”, “said”, and “red”, Natalia shows her emerging knowledge of English vowels. She reads the words “play”, “see”, and “red” accurately, but the word “said” she read as / sind/. Unlike Spanish, where vowel symbol-sound correspondence is always consistent, English vowel sound-symbol correspondence depends on the environment of the vowel (e.g., ayà /ei/; double eeà/i/). Natalia’s emerging knowledge of English vowels may have been developing incidentally. “Play”, “see”, and “red” are high frequency words in her age group at school. It is likely that Natalia has heard and seen these words many times at school, and that she is drawing from what she sees and hears at school, as well as from her knowledge of Spanish phonetics.

Other examples of Natalia’s first steps into biliteracy are the ways she read the words “her” and “little”. In reading both words, Natalia used her emerging knowledge of English and her knowledge of Spanish phonetics. The English sound /h/, represented by the letter “h”, does not exist in Spanish. However, Natalia produced the English sound /h/ when reading the sentence. In reading the symbol “e” of the same word, Natalia used her knowledge of Spanish vowels and read /e/ as “e” sounds in “let’s”, and not the “schwa” or reduced “e” (/ə/), as it sounds in “her”. However, she does produce the “schwa” at the end of the word “little” (/lit-əl/), accurately reading this word. These examples of Natalia’s reading of English words indicates that at her first stages of English reading, Natalia draws from her knowledge of Spanish reading and from high frequency English words she may have seen in school and in her neighborhood. She uses her knowledge of Spanish consonants and applies it to her reading of English consonants. She does this rather consistently in most words. For reading English vowels, however, Natalia uses Spanish vowels, but also uses English vowel sounds for some words. She demonstrates the ability to articulate English vowels, but her application to words is inconsistent. This inconsistency seems to indicate that Natalia is in the process of working out a deeper understanding of the English vowel system.

Discussion

In Natalia’s family, an important homeschool connection was the one established by the use of a common language (Spanish), and by the alignment of the parent-child’s and the teacherchild’s interactions around books. As Natalia received formal reading instruction in Spanish at school, Juana and Arturo felt confident to strongly support Natalia’s reading at home. Parent-child discussions around text provided Natalia a variety of opportunities to grasp reading and academic concepts, and prepared her to actively participate in classroom discussions.

Researchers have argued that disconnections between home and school literacy practices among linguistically-diverse populations often render children’s native-language literacy practices invisible and undervalued in the school context (Orellana et al., 2003). Others have reported that for Hispanic parents, more specifically parents in Mexico, book reading is understood as a schoolbased practice, not a practice common to the home (Vance, Smith, & Murillo, 2007). The home literacy practices documented in this article provide an example of the opposite case, where home reading practices were centered on books, and school reading practices were more related than disconnected with the reading practices of the home. The experiences with reading in their families may have enabled Juana and Arturo to view book shared reading not only as an enriching educational practice, but also as a way to enjoy family time. Juana and Arturo demonstrated that with each of their shared reading styles, they were able to provide Natalia with reading support that was relevant to the school curriculum, and at the same time, provided a context for family sharing and pleasure around reading. While Juana emphasized the mechanics of reading (i.e., punctuation, decoding) and the semantics and sound of text, Arturo focused on the analysis of situations and raising questions from the text. Ms. Méndez’s instructional practices tapped on both the mechanics of reading and comprehension, and contributed to school-based knowledge of story grammar and reading strategies. As the home-school alignment of reading practices shown in this article is not commonly found in studies of literacy practices in US Hispanic homes and schools (Orellana et al., 2003; Paratore, Homza, Krol-Sinclair, Lewis-Barrow, Melzi, Stergis, & Haynes, 1995; Valdés, 1996), it would be interesting to continue building on the growing body of research that explores the home and school reading practices in the countries of origin of US immigrants to gain insight of the sociocultural contexts and ideologies associated with the practices and materials read at home (Jiménez, Smith, & Martínez-León, 2003) (Gregory, 1996; Rubinstein-Avila, 2007; Vance et al., 2007). Although the underlying reasons for the differences between the parents’ reading styles were not the scope of this study, the different ways in which the mother and the father read with Natalia are interesting and could represent fertile ground for further research. Particularly, a focus on the father’s reading can contribute to a growing body of knowledge that emphasizes the participation of low-income fathers in the literacy development of their children (Gadsden, 2003; Ortiz, Stile, & Brown, 1999). An important contribution of this research includes exploring the possible relationships between Natalia’s parents’ reading style and issues related to gender, past schooling, workplace literacies, and familiarity with the requirements of school literacy instruction (reviewer’s comment).

Although not schooled beyond high school in their home country, Juana and Arturo had an endowment of literacy knowledge that reflected itself in their strong repertoire of reading practices. Both were aware of the importance of literacy and of their participation in Natalia’s literacy development. Their academic-like home reading practices seem to be also fueled by their desire for Natalia to become a strong Spanish reader in a country where Spanish is a minority language, and where children have few opportunities to develop high levels of literacy in their L1. Juana and Arturo starkly differ from Hispanic parents reported in the literature, in that they clearly knew that their intervention in Natalia’s reading development was important, and that they knew how to intervene to guarantee Natalia’s success in the school’s reading curriculum.

Their knowledge of typical school reading practices and their deliberate actions to support Natalia’s reading are two characteristics that portray Juana and Arturo as knowledgeable and empowered parents. Their deliberate decision to place Natalia in the Spanish classroom enabled them to personally interact with Ms. Méndez, to understand school communications, and to be connected with Natalia’s school. Their confidence that their intervention in Natalia’s reading instruction was necessary and effective also makes them different from other Hispanic parents, who, unsure about whether their reading support at home would help their children with school reading, stop supporting their children (Goldenberg, 1987). Their home-countr y experience with literacy build their endowment of knowledge about reading that they now pass onto Natalia.

Like other Hispanic parents portrayed elsewhere (Ada & Zubiarreta, 2001), Juana and Arturo were seriously concerned about the absence of English literacy instruction in Natalia’s TBE program. The data from this study suggest that despite their concerns, Juana and Arturo’s choice to place Natalia in the TBE program for initial Spanish literacy instruction at school was the right one. Having Spanish as a common language between home and school enabled Juana and Arturo to naturally engage in familiar reading practices with Natalia at home, knowing that they were contributing to Natalia’s learning of the school reading curriculum and to her general Spanish repertoire. In addition, they felt that her schooling predominantly in Spanish ensured their goal of home-language maintenance. A scenario where Natalia was schooled predominantly in English would have meant that Juana and Arturo devoted less time to Spanish reading at home, and likely hired an English tutor to teach Natalia to read in English. Spanish, as a common language between home and school, gave Natalia and her family opportunities to foster familybased reading practices and reading learning opportunities.

The data show that Natalia’s strong Spanish reading skills encouraged her first steps towards biliteracy. Her reported understanding of reading as meaning-centered suggests the influence that her home-school reading experiences have had on her perceptions of the purpose of reading. Both home and school offered Natalia a diversity of opportunities to develop literacy in the native language, which enabled her to enjoy reading, to actively participate in the classroom, and to identify herself as a reader of Spanish, and gradually, of English. As Natalia built abilities and confidence as a Spanish reader, she ventured to claim ownership of English reading abilities. Natalia’s very first attempts at reading in English and her understanding of this experience were unique moments in the course of this study. Following her reading from the beginning of first grade at school and at home allowed me to see what she knew about reading just prior to her first steps into biliteracy. The data about how Natalia’s spontaneous exploration of English text (Reyes, 2001) led me to interpret that the combined efforts of school and home in the native language gave Natalia the confidence that she was a reader, which empowered her to jump into reading a new language. Francis, Lesaux, and August (2006) suggest that “rather than confusing children, as some have feared, reading instruction in a familiar language may serve as a bridge to success in English because decoding, sound blending, and generic comprehension strategies clearly transfer between languages that use phonetic orthographies, such as Spanish, French, and English” (p. 397).

Individuals involved in the education of young bilingual children need to be aware that when the school environment provides a context where children see their native language as a valuable resource worth using and learning about, and when native language instructional support is provided, it is possible to not only foster strong biliteracy capacities among young children, but in turn, benefit them with strong bilingual identities (McCarthey, García, López-Velásquez, Lin, & Guo, 2004). As Natalia, children who are exposed to print in both languages show interest and spontaneously engage in a diversity of biliterate behaviors (Reyes & Azuara, 2008). Educators of bilingual children in language minority contexts need to pay attention to young children’s biliterate interactions and use these interactions as teaching moments. Instead of viewing children’s attempts towards biliteracy as futile efforts to achieve skills that must be formally taught, teachers of bilingual children should encourage biliterate behaviors by inviting the children to use their L1 knowledge to explore L2 text. Future studies need to investigate ways in which teachers of bilingual children can take advantage of the appearance of biliterate behaviors initiated by the children and guide them towards biliteracy.