DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n1.9305Published:

2016-05-11Issue:

Vol 18, No 1 (2016) January-JuneSection:

Pedagogical Innovations“It’s the same world through different eyes”: a CLIL project for EFL young learners.

“El mundo visto desde miradas diferentes”: un proyecto que integra contenido y lenguaje para aprendices de inglés como lengua extranjera en primaria

Keywords:

contenido y aprendizaje integrado del lenguaje, aprendizaje de lengua extranjera, enseñanza basada en historias, contexto basado en tareas (es).Keywords:

CLIL, language learning, storytelling, task-based context (en).Downloads

References

Bailey, K. (1994). Typologies and taxonomies—An introduction to classification techniques. Sage Publications,

London.

Brumfit C., Moon J., & Tongue R. (1991). Teaching English to Children. From Practice to Principle. Longman

Group Ltd.

Byram, M. (2005). Foreign Language Education and Education for Intercultural Citizenship. International

Forum on English Language Teaching II – Culture, Content and Communication, Faculdade

de Letras da Universidade do Porto.

Byram, M. , & Fleming, M. (1998). Language Learning in Intercultural Perspective: Approaches through

Drama and Ethnography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching Languages to Young Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages– Learning, Teaching,

Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coyle, D. (2008). CLIL – a pedagogical approach. In N. Van Deusen-Scholl, & N. Hornberger, Encyclopedia of

Language and Education, 2nd edition (pp. 97-111). Springer.

Coyle, D., Hood P., & Marsh D. (2010). CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Dalton-Puffer, C. and Smit, U. (2007). Introduction. In Dalton-Puffer, C., & Smit, U. (ed.), Empirical

Perspectives on CLIL Classroom Discourse. Frankfurt, Vienna: Peter Lang, 7-23.

Davies, A. (2007). Storytelling in the Classroom: Enhancing Traditional Oral Skills for Teachers and Pupils.

London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Duong, N. C. (2008). Do games help students learn vocabulary effectively? Lac Hong university.

Ellis, R, Basturkmen, H., & Loewen, S. (2001). Learner uptake in communicative ESL lessons. Language Learning, 51(2), 281-318.

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (1991). The Storytelling Handbook for Primary Teachers. London: Penguin Books.

Estaire, S., & Zanon, J. (1994). Planning Classwork: A Task Based Approach. Oxford: Heinemann.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century. New York: Basic Books.

Garvie, E., (1990). Story as vehicle. Clevedon, Avon: Multilingual Matters.

Gimeno, A., Ó Dónaill, C., & Zygmantaite, R. (2013). Clilstore Guidebook for Teachers. Tools for CLIL

Teachers. Retrieved from: http://www.languages.dk/archive/tools/book/Clilstore_EN.pdf.

Griva, E., & Semoglou, Κ. (2013). Foreign language and Games: Implementing Physical activities of creativity at

early years (In Greek). Thessaloniki: Kyriakidis Editions.

Griva, E., & Kasvikis, K. (2015). CLIL in Primary Education: Possibilities and challenges for developing

L2/FL skills, history understanding and cultural awareness. In Ν. Bakić-Mirić & D. Erkinovich Gaipov (Eds.),

Current trends and issues in education: an international dialogue. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 125-140.

Grugeon, E., & Gardner, P. (2000). The Art of Storytelling for Teachers and Pupils, London: David Fulton.

Halliwell, S. (1992). Teaching English in the primary classroom. London: Longman.

Järvinen, H. (2007). Language in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). In Marsh D., & Wolff D.

(Eds), Diverse Contexts – Converging Goals. CLIL in Europe.

Kiraz, A., G¨uneyli, A., Baysen, E., G¨und¨uz, S., & Baysen, F. (2010). Effect of science and technology learning

with foreign language on the attitude and success of students. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2,

–4136.

Koki, S. (1998). Storytelling: the Heart and Soul of Education. Pacific Resources for Education

and Learning. Retrieved from: http://www.prel.org/media/139722/55_storytelling.pdf.

Korosidou, E., & Griva, E. (2014). CLIL Approach in Primary Education: Learning about Byzantine Art and

Culture through a Foreign Language. Studies in English Language Teaching, 2(2), 216-232.

Korosidou, E., & Griva, E. (2013). “My country in Europe”: a Content - based Project for Teaching English as a

Foreign Language to Young Learners. Journal of Language Teaching and Research. Academy Publisher, Finland.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language learning and acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon.

Lasagabaster, D. (2008). Foreign Language Competence in Content and Language Integrated Courses. The Open

Applied Linguistics Journal, 1, 31-42.

Luong, B. H. (2009). The application of games in grammar review lessons for sixth graders. HCM city: M.A

thesis at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University- HCM City.

Maillat, D. (2010). The pragmatics of L2 in CLIL. In C. Dalton-Puffer. T. Nikula & U. Smit (eds.). Language Use

and Language Learning in CLIL Classrooms. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Marsh, D. (2000). An introduction to CLIL for parents and young people. Ιn Marsh, D. and Lange, G (Εds.),

Using Languages to Learn and Learning to Use Languages. Jyvaskyla: University of Jyvaskyla.

Mattheoudakis, M., Alexiou, T. & Laskaridou, C. (2014). To CLIL or not to CLIL? The Case of the 3rd Experimental Primary School in Evosmos. Major Trends in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics 3: Selected Papers from the 20th ISTAL, 3, 215-234.

McWilliams, B. (1996). Some Basic Principles for Storytellers. Retrieved at:

http://www.eldrbarry.net/clas/ecem/bpsc.pdf.

Mehisto, P., Marsh, D., & Frigols, M. (2008). Uncovering CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning in

Bilingual and Multilingual Education. Oxford: Macmillan.

Moore, F.P. (2009). On the Emergence of L2 Oracy in Bilingual Education: A comparative Analysis of CLIL and

Mainstream Learner Talk. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla. Unpublished PhD thesis.

O’Malley, J., & A. Chamot. (1990). Learning Strategies in Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Orlick, T. (2006). Cooperative games and sports: Joyful activities for everyone. Champaign,IL: Human Kinetics.

Papadopoulos, I., & Griva, E. (2014). Learning in the traces of Greek Culture: a CLIL project for raising

cultural awareness and developing L2 skills. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational

Research, 8. http://www.ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter.

Pedersen, E. M. (1995). Storytelling and the Art of Teaching. English Teaching Forum, 33 (1), 2-5.

Prabhu, N. S. (1987). Second Language Pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Richards, J. (2006). Communicative language teaching today. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J.C. (1991). Towards reflective teaching. The Teacher Trainer, 5(3), 4-8.

Richards, J., & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 16 -17.

Schiller, P. (1999). Start smart: Building brain power in the early years. Beltsville, MD. Gryphon House.

Scott, W., & Ytreberg, L.H. (1994). Teaching English to Children. London: Longmann.

Skehan, P. (1996). A framework for the implementation of task-based instruction. Applied Linguistics, 17, 38-

Slattery, M., & Willis, J. (2001). English for Primary Teachers: A Handbook of Activities and Classroom

Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stoyle, P. (2003). Storytelling: Benefits and Tips. British Council BBC Teaching English. Retrieved from:

http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/think/articles/storytellingbenefits.

Swain, M. (1993). The output hypothesis: Just speaking and writing aren’t enough. The Canadian Modern

Language Review, 50, 158 -164.

Sweeney, A. (2005). Using Stories with Younger Learners – without Storybooks. British Council, 12-15.

Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2009). Playing to Learn: A Review of Physical Games in Second Language

Acquisition. Simulation and Gaming, 40 (5). pp. 645-668.

Troncale, N. (2002). Content-Based Instruction, Cooperative Learning, and CALPInstruction: Addressing the

Whole Education of 7-12 ESL Students. Retrieved from:

http://journals.tclibrary.org/index.php/tesol/article/viewFile/19/24.

Tsai, Y. & Shang, H. (2010). The impact of content-based language instruction on EFL students' reading

performance. Asian Social Science, 6 (3),77-85.

Wade, R. C. & D. B., Yarbrough. (1996). Portfolios: A Tool for Reflective Thinking in Teacher Education?

Teaching and Teacher Education, 63-79.

Willis J. (1996). A Framework for Task-based Learning. Harlow: Longman Pearson Education.

Willis D. & Willis, J. (2007). Doing Task-based Teaching. Oxford: Oxford.

Wolff, D. (2005). Approaching CLIL. In Marsh, D. et al,. (Eds), Project D3 - CLIL Matrix. The CLIL quality

matrix. Central Workshop Report, 10-25. Retrieved from: //www.ecml.at/documents/reports/wsrepD3E2005_6.pdf.

Wong, V. (2008). Promoting children's creativity through teaching and learning in Hong Kong. In A. Craft, T.

Cremin & P. Burnard (Eds.), Creative learning 3-11 and how we document it (pp. 93-101). Stoke-on-Trent;

Sterling, VA: Trentham.

Wright, A. (1995). Storytelling with Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Young, J. (2002). Creating Online Portfolios Can Help Students See 'Big Picture,' Colleges Say. Chronicle of

Higher Education.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n1.9305

PEDAGOGICAL INNOVATIONS

"It's the same world through different eyes": a content and language integrated learning project for young EFL learners

"El mundo visto desde miradas diferentes": un proyecto que integra contenido y lenguaje para aprendices de inglés como lengua extranjera en primaria

Eleni Korosidou1 Eleni Griva2

1 University of Western Macedonia, Greece. koro_elen@hotmail.com

2 University of Western Macedonia, Greece. egriva@uowm.gr

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Korosidou E. & Griva E. (2016). "It's the same world through different eyes": a content and language integrated learning project for young EFL learners. Colomb.Appl.Linguist.J. 18(1), pp 116-132

Received: 02-Oct-2015 / Accepted: 29-Feb-2016

Abstract

This paper presents the design, implementation, and evaluation of a project entitled "It's the same world through different eyes," which was based on the principles of the Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach and was piloted with 4th grade primary school students (between 9 and 10 years of age). More specifically, we employed a dual-focused approach, focusing equally on EFL (English as a foreign language) and content development. For the purpose of the project, we designed a mini-syllabus with the stories being at the core of the design. The objectives of the project were to a) develop the students' receptive and productive skills in EFL), b) develop their sensitivity towards diversity, and c) enhance their citizenship awareness. Students were provided with opportunities to express themselves verbally and nonverbally, and participate in a variety of creative activities in a multimodal teaching context. The findings of project indicated students' improvement regarding both their receptive and productive skills in the target language, and the development of children's citizenship awareness, and their sensitivity towards diversity.

Keywords: CLIL, language learning, storytelling, task-based context

Resumen

Este manuscrito presenta el diseño, la realización y la evaluación de un proyecto titulado "El mundo visto desde miradas diferentes" para aprendices de inglés como lengua extranjera en primaria, basado en los principios de integración de contenido y lengua para el aprendizaje (CLIL) piloteado con estudiantes de cuarto grado de escuela primaria (entre 9 y 10 años de edad). Se utilizó un enfoque dual-enfocado, concentrándonos igualmente en lengua inglesa y desarrollo de contenidos. Se diseñó un mini-syllabus basado en historias. Los objetivos del proyecto fueron: a) desarrollar las habilidades receptivas (escucha y lectura) y productivas (oral y escrita) de los estudiantes en inglés como lengua extranjera, b) desarrollar su sensibilidad hacia la diversidad, c) realzar su conciencia ciudadana. A los estudiantes se les brindó la oportunidad de expresarse verbalmente y no verbalmente, y de participar en una variedad de actividades creativas en un contexto de enseñanza multimodal. Los resultados indicaron mejoramiento de las habilidades receptivas como productivas de los estudiantes en la lengua meta y el desarrollo de la conciencia ciudadana en los niños y su sensibilidad hacia la diversidad.

Palabras clave: contenido y aprendizaje integrado del lenguaje, aprendizaje de lengua extranjera, enseñanza basada en historias, contexto basado en tareas

Introduction

In the present study, Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) was introduced in order to better address students' needs since CLIL is proposed as an innovative, integrated educational approach, aiming to promote multilingualism and multiculturalism (Järvinen, 2007). CLIL is "a dual-focused educational approach in which an additional language is used for the learning and teaching of both content and language" (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010, p. 1). In other words, the learning process focuses on both the development of specific content knowledge and the communicative ability in the foreign language (FL) to express ideas and aspects related to the subject (Marsh, 2000). Marsh and Langé claim that CLIL as a generic term "refers to any educational situation in which an additional language […] is used for the teaching and learning of subjects other than the language itself" (cited in Wolff, 2005, p. 11), making it clear that CLIL is a dual- focused educational approach which aims at education through construction, rather than instruction. Furthermore, CLIL is defined as "an approach which is neither language learning nor subject learning, but an amalgam of both and is linked to the processes of convergence" (Coyle, Hood, Marsh, 2010, p. 4). CLIL integrates four interrelated principles for effective classroom practice: 1) 'content,' referring to subject matter, 2) 'communication,' focusing on language knowledge and appropriate language use, 3) 'cognition,' related to the development of learning and thinking processes, and 4) 'culture,' with special focus on enhancing awareness of otherness and self and developing a pluricultural understanding and global citizenship (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010). In this sense, students can gain sensitive attitudes towards others which will make them better prepared citizens for transnational relationships.

In the last decades, CLIL has been cast in the role of "a catalyst for change in language education" (Marsh & Frigols, 2007, p. 33) and has been revealed as an advantageous approach in terms of a) improving language competence as well as oral and intercultural communication skills (Gimeno, Ó Dónaill, & Zygmantaite, 2013), b) promoting intercultural knowledge and understanding, and c) developing cultural awareness and sensitivity (Korosidou & Griva, 2014; Papadopoulos & Griva, 2014). Since it has been indicated that the CLIL approach provides learners with opportunities for being exposed in an authentic learning environment (Troncale, 2002), benefits were recorded with regard to learners' speaking skills in the target language. More precisely, CLIL students seemed to display greater fluency, quantity, and creativity and gradually increased the use of foreign language for spontaneous face-to-face interaction (Dalton-Puffer & Smit, 2007). Furthermore, great gains were recorded in relation to receptive and productive lexicon, and a specific advantage of CLIL students seemed to lie in academic vocabulary (Dalton-Puffer & Smit, 2007; Lasagabaster, 2008; Lo & Murphy, 2010; Mattheoudakis, Alexiou, & Laskaridou, 2014). This holistic methodological approach is also related to expanding students' cognitive skills and enhancing their reading comprehension and critical thinking ability (Tsai & Shang, 2010), as well as enriching a learner's understanding and association of different concepts, therefore enabling him or her to achieve a more sophisticated level of learning in general (Marsh, 2000).

The present study aimed at implementing a CLIL project in the context of an EFL classroom in a Greek primary school. The framework designed was story-based related to diversity in an attempt to interweave language, content learning, and sensitivity to issues of diversity.

The Project

The present section describes the purpose and objectives of the CLIL project introduced in a primary school EFL classroom. Moreover, the content of the project as well as the sample of the study are presented in detail.

Purpose and Objectives of the Project

Special emphasis was placed on enhancing students' sensitivity towards diversity and their citizenship awareness. The intercultural skills, as presented in the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2001), include cultural sensitivity and the ability to bring the culture of origin and the foreign culture in relation with each other, as well as the capacity to fulfill the role of cultural intermediary between one's own culture and the foreign culture. Moreover, it is stated that the learner should have the ability to overcome stereotyped relationships and to deal effectively with intercultural misunderstanding and diversity (Council of Europe, 2001). It is worth mentioning that the CEFR was developed by the Council of Europe to provide common methods of teaching, learning, and assessing language skills across Europe. The CEFR sets out six levels of language competency from beginner to advanced (A1 to C2) and describes what language users should be able to do in terms of listening, reading, speaking and writing.

The above mentioned aspects were taken into consideration for the design and implementation of the CLIL project which introduced a general framework for using stories related to diversity in an attempt to interweave language, content learning, and sensitivity to diversity. In particular, the following objectives were set:

a) To develop students' skills in the target language, English as a foreign language (EFL)

b) To develop their sensitivity towards diversity

c) To enhance their awareness of citizenship in the sense of the qualities that a person is expected to have as a responsible member of a community. It was thought that the English language could play an important role in enhancing students' citizenship awareness.

Context and Sample

The CLIL project was launched in the 2014-2015 school year within a fourth grade primary school classroom in the city of Florina in Northern-Western Greece. In the specific context, the content was used in a foreign language-learning class. 20 students between nine and ten years of age (8 boys, 12 girls) were the sample of this pilot study. All students were Greek-speaking and their EFL competency level was A1+ (elementary level) according to the CEFR. They had been taught EFL as a compulsory subject for three years according to the Greek pilot primary school curriculum.

Theoretical Framework

The following section deals with the theoretical foundations of the project launched. Research data are provided, aiming to elucidate the theoretical framework as well as the rationale behind the present project. Emphasis is also placed on task-based learning and students' active participation in purposeful communication.

Story-based learning

Recent research seems to support the view that storytelling offers great potential regarding promoting critical spirit, by raising vital questions and therefore enabling learners to be more judgmental and create new knowledge, as well as raising students' sensitivity concerning equity issues. Specifically, storytelling is very popular among young children since it has been proven to appeal to children's imagination (Cameron, 2001; Haliwell, 1992; McWilliams, 1996) to encourage positive attitudes towards cultural diversity (Stoyle, 2003), as well as to broaden their knowledge of the world (Cameron, 2001). Stories seem to offer great potential regarding the enhancement of an individual's cultural awareness since they involve aspects of culture and life and help the student to appreciate different cultures and customs (Davies, 2007; Garvie, 1990). For this purpose, Wright (1995) believes that "stories should be a central part of the work of primary teachers whether they are teaching the mother tongue or a second/foreign language" (p. 4).

As far as language learning is concerned, stories offer opportunities for authentic communication; they not only develop language skills but also help children broaden their vocabulary repertoire as students are in 'contact' with many new words while listening to or reading stories (Cameron, 2001). In addition, stories provide more authentic language input (Pedersen, 1995), they make learning an amusing process, and help children enjoy language learning in purposeful communication (Slattery & Willis, 2001). Based on Ellis's and Brewster's (1991) views, there are certain reasons for implementing storytelling in the FL class. Stories: a) help children develop positive attitudes towards language learning because they are motivating and fun, b) they exercise their imagination, and help develop their creativity, c) they encourage children's social and emotional development, and d) they develop their listening skills. However, storytelling itself cannot guarantee successful teaching and learning since there is the need for selecting the right stories based on children's interests, and setting appropriate learning goals, as well as making the story experience interactive (McWilliams, 1996).

Game-based framework

A variety of games and creative activities—role playing, dramatizations, constructions, posters, cartoon drawings—were incorporated in this mini-syllabus. Drawing attention to recent studies, it has been indicated that games in the language classroom enhance students' communicative skills and provide opportunities for holistic language development (Griva & Semoglou, 2013; Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2009). Also, games in the foreign language classroom have been proven to activate multiple intelligences (Gardner, 1999), provide opportunities for social skills development (Orlick, 2006), enhance peer interaction (Swain, 1993), as well as to enable young learners to hold a positive attitude toward the improvement of motivation and vocabulary acquisition (Wang, Shang, & Briody, 2011).

Task-based framework

Since "tasks are activities, where the target language is used by the learner for a communicative purpose in order to achieve an outcome" (Willis, 1996, p. 23), special emphasis was given to enhancing students' communicative skills and enhancing interaction in a playful learning context. According to Willis and Willis (2007, pp. 12-14), an activity is considered to be task-based if it fulfils the following criteria: a) it engages learners' interest, b) focuses primarily on meaning, c) includes a certain goal or outcome, d) assesses students in terms of an outcome, e) states task completion as a priority, and f) relates to real-world activities.

Therefore, in the CLIL project we provided students with opportunities to use the target language creatively and spontaneously through being involved in 'tasks.' In general, an attempt was made to maximize opportunities for active student participation and problem solving (Griva & Semoglou, 2013) by paying special attention to creating a relaxed environment during all task-based instruction stages: the 'pre-task,' the 'task cycle,' and the 'language focus' (Willis & Willis, 2007). Particular emphasis was given to using game-based activities, enabling learners to learn in a playful context, using their imagination and expressing themselves creatively (Duong, 2008; Griva & Semoglou, 2013; Luong, 2009), as well as interacting to reach decisions and solve problems (Richards, 2006).

Methodology

The Mini-Syllabus

In this section, the mini-syllabus designed by the researchers is explicitly described. The stories selected, the broad thematic areas processed by the students, and the rationale behind the activities designed are presented below.

Having considered Grugeon and Gardner's (2000) statement regarding the use of stories in the teaching practice "to tell in school traditional tales: myths, legends, fables, folk and fairy tales which reflect communal ways of making sense of experience […] they offer alternative worlds which embody imaginative, emotional and spiritual truths about the universe" (p. 3), the researchers made an attempt to select stories which would both motivate students' interest and would provoke critical thinking and reflection on aspects related to diversity. For the purposes of the present project, we selected the following stories that dealt with various aspects of diversity:

• Marshmallow's First Day at School: A children's story about racial diversity(http://www.booksie.com/childrens_stories/book/mssahmof2/marshmallows-first-day-of-school),

• Irene: A story about a refugee child(https://www.unhcr.gr/ekpaideysi/ekpaideytiko-yliko/eirini.html),

• Chuskit Goes to School: A children's story about physical disability(https://bookfusion.com/books/101313-chuskit-goes-to-school-english-cdr/download/Chuskit-goes-to-School.pdf+&cd=1&hl=el&ct=clnk&gl=us)

• Human Rights: Stories and poems about diversity, as well as defending human and children's rights(http://www.dennydavis.net/poemfiles/bbychld/special.htm).

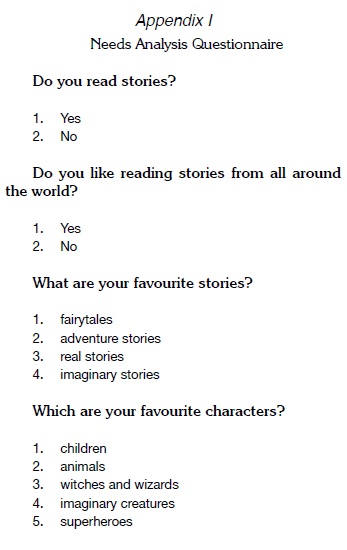

It is worth mentioning that before the pilot intervention, the researchers considered it essential to gather some background information on the students' reading habits and story preferences. Therefore, a questionnaire of students' preferences was distributed to them (see Appendix 1).

The project was designed on the basis of including and focusing on the various aspects of diversity (race, immigration, disability, etc.). The mini-syllabus was designed around the following topics:

Children from different races

• Racial and particular characteristics

• Race and clothing style

• Racial stereotypes and discrimination

The immigrant child

• Immigrant children and their needs

• The rights of an immigrant child

• Protection and care of refugee children

The disabled child

• Physical and mental disability

• What disabled children can achieve

• Disabled children and society

Me and "the other"

• Aspects of "the other" which oppose "the same"

• Foreignness and equality

• Prejudices

The activities designed for our topic-based mini-syllabus were based on the guidelines provided by Brumfit, Moon, and Tongue (1991) paying special attention to young learners' needs and cognitive development. More specifically, the researchers focused on designing activities that were enjoyable, creative, and consequently aimed at a) developing students' imagination, b) offering opportunities for specific vocabulary acquisition through meaningful and authentic language use, c) encouraging social interaction and social skills development, d) constructing meaning through illustrations, visuals, videos, and e) learning by doing.

Implementation of the CLIL Project

This section focuses on the implementation of the experimental project, clearly reporting the target language learning procedures, the learning products, as well as the FL skills aimed to be developed during the different stages accomplished. Furthermore, comments made on the part of the students are provided, illustrating their thoughts and feelings and justifying the strategies they employed.

Task-based framework

A total of 35 one-hour teaching sessions were implemented in a task–based framework, incorporating the principles of task-based language teaching (Willis, 1996) and focusing on the use of authentic language through meaningful tasks.

In this framework, the expected learning outcomes involved the development of:

Cognitive skills, through engaging students in numerous inquiry-based activities, where they could be actively involved in negotiating and decision making processes.

Communication skills, though participating in role plays, presentations, and dramatizations, where children were asked to use the target language in authentic environment for communication purposes.

Sensitivity towards diversity and awareness of citizenship, through engaging students in content-based interactive activities.

Procedure

Each thematic unit was carried out in a task-based framework through three basic stages (Willis, 1996) as described below.

The pre-task stage

The target of this stage was to introduce students to the topic and the task. Particularly, the teacher aimed at motivating students and eliciting previous knowledge and experience on the topic of the specific thematic area by screening the relevant story. Activating students' content schemata or providing them with background information serves as a means of defining the topic area of a task (Willis, 1996). Furthermore, pre-task activities serve to introduce new language, to mobilize existing linguistic resources, to ease processing load, and to push learners to interpret tasks in more demanding ways (Skehan, 1996). In the same line, Dörnyei (2001) emphasizes the importance of presenting a task in a way that motivates learners and also suggests that task preparation should involve strategies for whetting students' appetite to perform the task.

In the present project, students were encouraged to guess what the story would be about, as well as to take notes regarding the aspects of the story which were of interest. Therefore, content-specific vocabulary to be learned was introduced, usually through discussion, showing some photos/flashcards and a spidergram, where the most important ideas were summarized in a circle drawn by the teacher; all the relevant words were noted. Scaffolding was primarily directed at enabling students to express themselves in the target language. In that way, students had the chance to practice their oral skills so as to negotiate and decipher meaning and to get familiarized with content-specific vocabulary.

Then, the researcher introduced the children to the story in a multisensory context (PowerPoint presentation, Prezi zooming program, sound documents, video clips) in the target language. Thus, a multimodal and multisensory environment was created as by using multiple senses to learn, children find it easier to match new information to their existing knowledge (Schiller, 1999). Thus, a number of videos were used in that stage providing children with some information on various topics related to diversity, such as people with special needs, famous/talented people with mental or physical disabilities, and children's rights.

The task-cycle stage

During this stage, which consisted of three sub-stages (task, planning, and report), the students were welcomed to work in pairs or groups in order to accomplish creative and interactive activities (examples contained in Appendix 3). Specifically, they were asked to re-tell the story, draw pictures from the story, and describe their drawings. They were also asked to role play or change the story or its ending. Emphasis was placed on enabling them to learn the FL indirectly through communicating in it. Their oral or written reports were produced while working cooperatively and interacting, always bearing in mind the specific goal to be achieved.

The children were responsible for the completion of the task, by cooperating, taking turns, and negotiating when communication problems arose. In that way, they gradually became able to perform a wide range of language functions through agreeing and disagreeing, asking, giving, or repeating information, as well as suggesting solutions. Students were involved in employing a number of cognitive and metacognitive strategies, by making comparisons, discussing and reviewing their ideas, and drawing conclusions. The teacher-researcher ensured that the tasks the children were engaged in provided them with opportunities to interact in an activity-based context. In other words, she acted as a facilitator and coordinator of students' work, assisting them to participate actively in their group work and providing them with feedback, when necessary.

At the end of this stage, each group presented their 'product' or 'creation' in class (e.g., posters, written reports, drawings, role plays, dramatizations). Paying attention to what Willis (1996) suggests as a "natural conclusion of the task cycle," children were also encouraged to orally present a report in their mother tongue (Greek) on how they performed the task or on how they solved the 'problem.' They were also invited to comment on how they used the target language, how they dealt with communication problems, as well as to 'identify' what they learned from the task. In more detail, students stated that "I was not used to working in a group to perform a task. Therefore, I was using a lot of "I-centered" statements at first, but gradually I was engaged in cooperation and interaction with my peers. I was asking for other students' opinions and being more open to their ideas" or "While we were performing a task we helped each other by paraphrasing our statements, whenever our classmates couldn't understand what we were trying to communicate" (students' verbal data recorded and rephrased by the researchers). The teacher-researcher provided them with opportunities to reflect on their work and, consequently, to gain insights regarding how they could improve their performance. To exemplify, she was using language like "Let's summarize the points that you made." "From your point of view, what helped you to successfully accomplish this task?" or "What would you like to do in a different way next time?" (teachers' field notes). This process seems to have contributed to the development of the metacognitive strategies of planning, monitoring, and evaluating, which are considered to be at the core of language learning (O'Malley & Chamot, 1990).

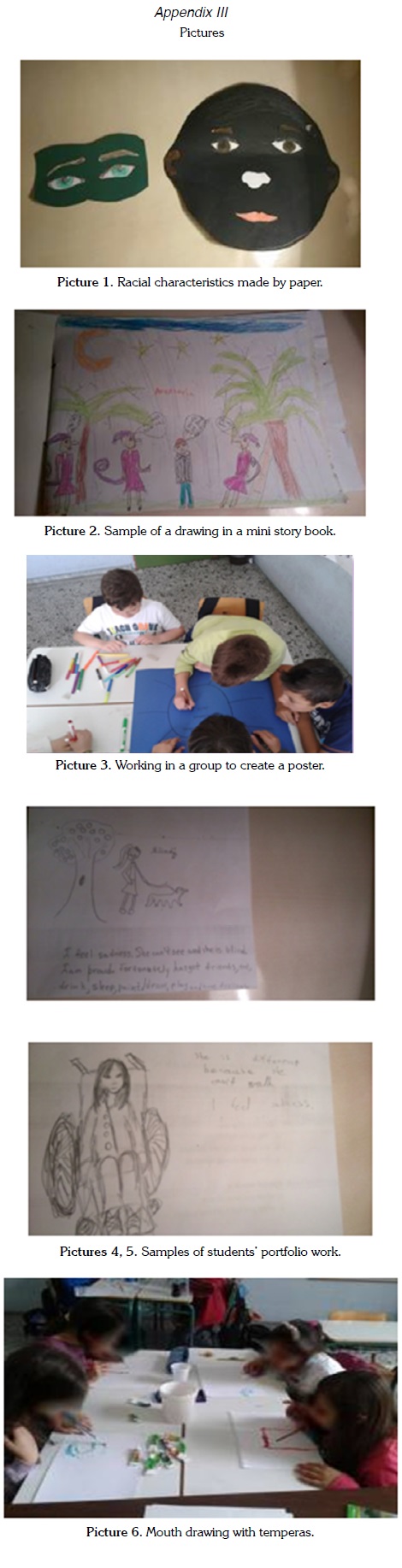

The students managed to create and present a variety of products. A representative sample of their work contains the following (see Appendix 3):

• racial characteristics made by paper (picture 1)

• a mini storybook (picture 2)

• posters (picture 3)

• portfolios including their short written works and reports (pictures 4, 5)

• drawings and creative works (picture 6)

Moreover, they participated in physical activities such as:

• Simulation games between groups where a group of minority student-refugees meet another group of majority students

• "Lead me to the correct place" games, where students role played the abled and the disabled child

• Games with their eyes covered where they had to accomplish a task such as to write a word, catch an object, etc.

The Language Focus and Feedback Stage

During this stage, students were given opportunities to further practice their oral skills and use the vocabulary acquired in order to communicate their feelings and views on the topic processed. They were engaged in a variety of games and physical activities in which they used the foreign language for authentic and communicative purposes while interacting and cooperating with peers (Scott & Ytreberg, 1994). During this stage, opportunities were provided to students to enhance their equity sensitivity and to be aware of citizenship issues; to exemplify, they were asked to discuss and reflect on issues of social injustice and inequality. Byram and Fleming (1998) defined a complex of factors involved in the process of raising cultural and citizenship awareness, such as knowledge, attitudes, skills and values, and critical awareness. Drawing attention to these factors, the participants in the project were invited to reflect on the change of their behavior, as well as on their willingness to adopt different perspectives and their sensitivity to intercultural values. The issues raised in the stories introduced in the pre-task stage, as well as the activities in which the students participated during the task-cycle stage greatly contributed to making students become more aware of their feelings and attitudes towards diversity during this last stage. In addition, they were provided with opportunities to recycle newly acquired vocabulary and summarize their views and perspectives.

Results

Evaluation of the Project

The evaluation process of the present project is outlined in this section. As indicated below, both summative and formative assessment with a major focus on the formative process was conducted in order to estimate the feasibility of the project by using the pre-test/post-test measure, the teacher/researcher journal, and student interviews.

Pre-test/post-test results

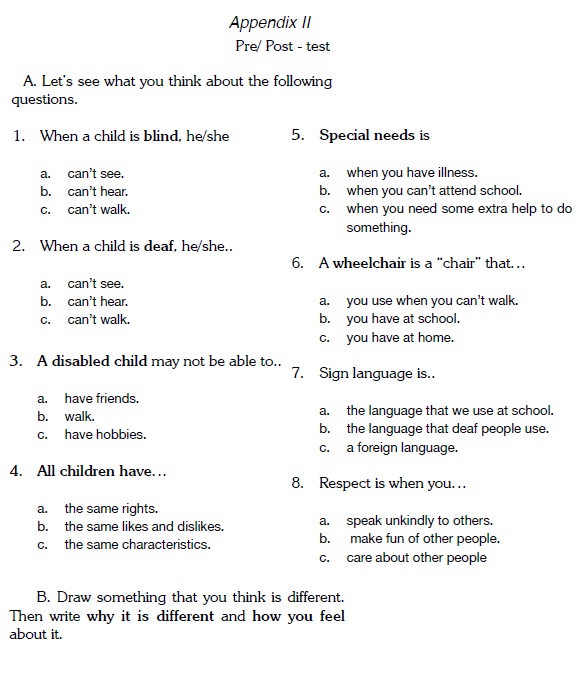

All participants were tested before and after the completion of the interventions on CLIL approach. The same test interweaving content knowledge and target-language was administered as a group test by the researcher one week before the beginning of the project, and again a week after the completion of the project. The pre-/post-test consisted of two parts.

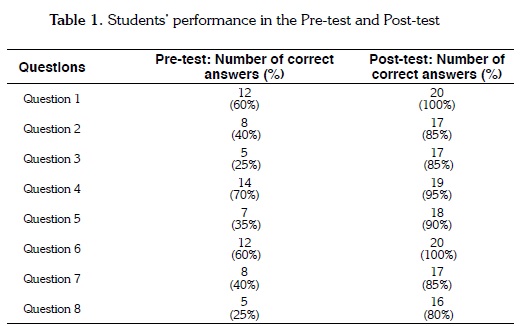

The first part comprised of eight multiple choice questions (see Appendix 2), where the students were asked to choose one out of three answers on issues related to diversity. The numbers of the correct answers given by the children in the pre- and post-test are presented in Table 1.

It is worth mentioning that significant progress between the two measurements was revealed. The students' performance in the first part of the pre/post-test suggested an impact of the CLIL project on their knowledge about diversity and the enhancement of general and specific FL vocabulary. Specifically, in most cases (Questions 2, 3, 5, 7, 8) the difference between the "correct answer" score before and after the intervention was more than double.

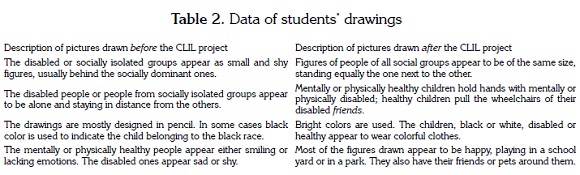

In the second part of the pre/post-test, students were asked to draw pictures depicting how they perceive diversity and to write a short description of their drawing and their feelings about it. Some of the data extracted from the analysis of their drawings before and after the CLIL intervention are presented in following table (see Table 2).

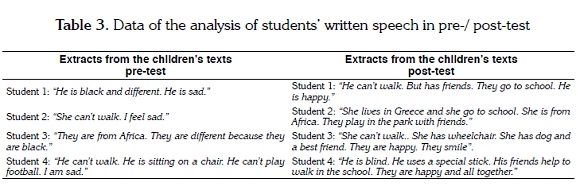

It is also worth noting that differences were observed in the length and range of vocabulary used regarding the sentences describing their drawings and their feelings in the pre-test and the post-test. In the post-test, the students wrote longer sentences, using relevant vocabulary and focusing on the positive feelings of the disabled child, the refugee, etc. (see Table 3).

Teacher/researcher journal records

Since journals have been proven to be valuable tools for reflecting on and improving the teaching/learning process (Richards, 1991), the teacher-researcher kept a journal once a week in order to reflect on certain learning and teaching issues in the CLIL context. Those journals were thought to be central to gaining an in-depth understanding of the implementation and monitoring of the interventions in the CLIL classroom. Concerning the form of the researcher's journal, it was based on the "questions for journal keeping" (Richards & Lockhart, 1994), and was designed around three axes of questions related to the dual focused teaching process, children's behavior during the project, and the researcher's reflection on the project.

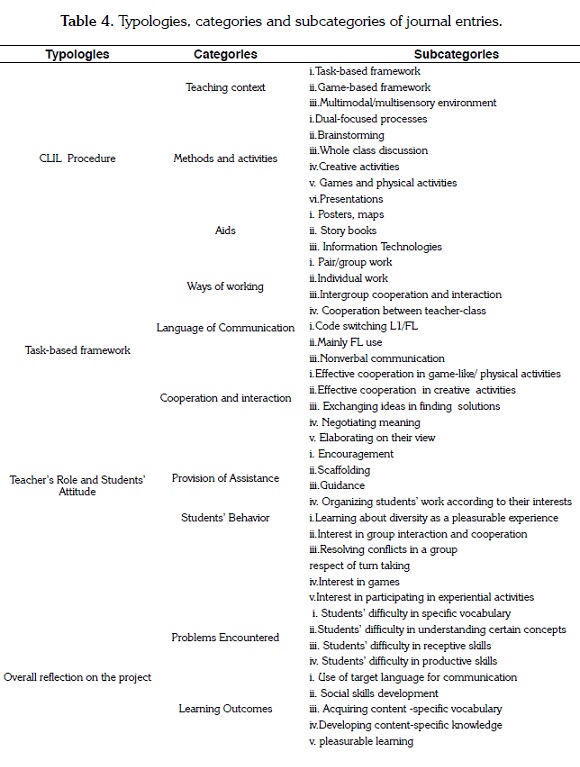

The qualitative analysis of the journal entries resulted in four typologies as presented below. More specifically, the typologies were a) CLIL Procedure, b) task-based framework, c) teacher's role and students' attitude, and d) overall reflection on the project, each one encompassing a number of categories and subcategories (see Table 4).

The analysis of the teacher-researcher's journals indicated that the students had the opportunity to work in a variety of teaching contexts and were engaged in a number of different types of interaction during the learning process. They interacted verbally using the FL for authentic content-specific communication, and both verbally and non-verbally during creative and physical activities.

The teacher employed various teaching methods and created a multimodal learning environment always focusing on the students' needs and using various materials to stimulate their interest in acquiring content knowledge. She worked as an active mediator and facilitator, providing and organizing meaningful activities. Regarding students' behavior, they expressed their interest in learning about diversity through stories and experiencing learning as a pleasurable process, and by actively participating in games and experiential activities. Finally, the children encountered some problems in understanding specific vocabulary or certain contexts but eventually managed to acquire content-specific vocabulary and to develop content-specific knowledge.

Student interviews

Follow-up structured interviews were conducted with the students in their mother tongue (Greek) to collect information about their viewpoints on and their attitudes toward the CLIL project implementation. In other words, its purpose was to identify if the interventions responded to students' interests and expectations. The students were encouraged to feel free to answer the following categories of questions:

1. What did you like most about the project?

2. What were the main difficulties you encountered during the project?

3. What could have been done in a different way?

4. What did you learn most in relation to foreign language and diversity?

The qualitative analysis of the student interview data revealed a generally positive attitude towards the CLIL project. More precisely, students' views on specific aspects of the implementation are summarized below.

Question: What did you like most about the project?

The great majority of the students declared that working on a CLIL project was a pleasurable learning process. They mostly liked having been involved in various creative and cooperative activities. Specifically, they stated that "Learning English was fun. We made mouth drawing with temperas" (during mouth drawing students were asked to draw pictures by placing their paintbrushes in their mouth, not being able to use their hands) and "I liked the games... I wasn't used to learning English in that way…. It was amazing!" Most of the students showed preference for the stories as well as the audiovisual material used during the storytelling process "I liked the stories and the PowerPoint presentations. I have never done this before in an English class" and "I liked watching the video with Irene's story... I liked her story." Moreover, most of the students showed particular preference to doing artwork such as face masks, creations of posters, or drawings in a story book. They stated that "I wasn't used to learning English in that way. I liked being in a group with classmates and working together..." and "I learnt a lot of new vocabulary," "I learnt to present my work or my group's work in class." Learning about diversity issues was also mentioned by many students. They said: "I liked learning about what is different and how different people may feel" and "I used English words to talk about diversity. Now I know some new and useful vocabulary that I can use."

Question: What were the main difficulties?

Concerning the difficulties children encountered during the CLIL project, it was revealed that they faced particular problems with general and specific vocabulary in the stories. They stated that "online stories were difficult… many words…" and "stories were long, containing a lot of information and unknown words." Although a significant number of the participants showed preference to doing artwork, a certain number of the children regarded taking part in inquiry-based activities and creating artwork as difficult activities. They reported that "finding information online was a difficult task. The information was too much that I had to try hard to find out what was important and what was not" and another student mentioned: "At first the vocabulary used in online texts was very difficult and I couldn't understand. Then I used an online dictionary or learned some words. It became easier."

Question: What could have been done in a different way?

Most of the children expressed their satisfaction with the "alternative" project. They liked the interventions the way they were carried out. Only a few children declared that they would like to have a richer multimodal environment or to create more artwork.

Question: What did you learn most?

Regarding the benefits of the project as they were perceived by the children, the majority mentioned their active engagement in cooperative activities in a task-based framework: "I took part in activities … I learned how to work in a group and cooperate." They also mentioned that they had the opportunity to develop content knowledge in a different/alternative way: "different from what I was used to…."; "What was different was that I could play and learn English at the same time," and "I took part in creative activities. I liked making posters and working with my friends."; "My classmates helped me; we played, drew pictures and wrote reports together."

Learning about and being aware of citizenship and diversity was also mentioned by many students: "I learned a lot of things about different children…."; "I used English to talk about others." A number of the students declared that they really learned to work in teams: "I learned to work in a team with my friends. They helped me to write the story"; "… we helped each other to construct the masks…it was useful".

Discussion

The paper presents the design, implementation, and the estimation of the feasibility of a pilot CLIL project which aimed at improving students' skills in the target-language and raising their knowledge and awareness on issues related to citizenship and diversity. The data collected during and after the completion of the interventions revealed that the CLIL project, which followed the principles of story-based, task-based, and game-based learning, had a positive impact on the target-language and the content knowledge.

More precisely, students' oral skills seemed to be enhanced by participating in a variety of inquiry-based, creative, and interactive-cooperative activities, as the students became more confident regarding communicating in the target language. These data are in line with the findings of previous studies having revealed CLIL student's higher performance in the target language (Dalton-Puffer & Smit, 2008; Korosidou & Griva, 2013; Maillat, 2010; Moore, 2009). Concerning content-knowledge, it was showed that students tended to have improved their knowledge in relation to citizenship and raised their sensitivity to diversity which aligns with the findings of previous studies (Griva & Kasvikis, 2015; Gimeno, Ó Dónaill, & Zygmantaite, 2013; Kiraz et al., 2010). This happened in a task-based framework where children participating in macro activities came in contact with aspects of "the other," "the foreigner," or "the disabled" person. The participants had opportunities to cooperate creatively with their imagination stimulated to the fullest, and to interact and communicate both verbally and non-verbally in a playful, relaxing, and enjoyable environment.

Since the children were given insights into the cultural, social, and historical background of the country where the story originated, as Pedersen (1995) proposes, they were provided with the opportunities to raise cultural awareness and acceptance of diversity. Furthermore, stories provided a hint into other people's different perspectives of interpreting the world (Koki, 1998; Stoyle, 2003). Thus, they seemed to have developed their empathy through listening to stories and their involvement in creative work and interactive activities, as well as developing their sensitivity and awareness of accepting the difference among ideologies and abilities.

In conclusion, the CLIL project aimed at optimizing students' opportunities in gaining content-knowledge and enhancing target-language skills. Therefore, launching such a CLIL project on a wider scale and for a longer time could possibly contribute to further developing children's FL skills, sensitizing them even deeper on diversity issues, and educating them for being active, unbiased, and responsible citizens. Thus, there is the need for the specific project to be continued in the future, involving a wider sample of students and teachers, as well as incorporating stories from all around the world. In addition, the CLIL syllabus could present examples of good practices from materials developed for the specific educational context, as well as recommendations for the development and distribution of further CLIL materials and further practices for teachers around the world.

References

Brumfit, C., Moon, J., & Tongue, R. (1991). Teaching English to children: From practice to principle. Essex: Longman.

Byram, M., & Fleming, M. (1998). Language learning in intercultural perspective: Approaches through drama and ethnography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching languages to young learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dalton-Puffer, C., & Smit, U. (2007). Introduction. In C. Dalton-Puffer & U. Smit (Eds.), Empirical perspectives on CLIL classroom discourse (pp. 7-23). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Davies, A. (2007). Storytelling in the classroom: Enhancing traditional oral skills for teachers and pupils. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Duong, N. C. (2008). Do games help students learn vocabulary effectively? Retrieved from http://ed.Lhu.edu.vn/?CID=139&&NewsID=663.

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (1991). The storytelling handbook for primary teachers. London: Penguin Books.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. New York: Basic Books.

Garvie, E. (1990). Story as vehicle. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Gimeno, A., Ó Dónaill, C., & Zygmantaite, R. (2013). CLILstore Guidebook for Teachers. Tools for CLIL Teachers. Retrieved from: http://www.languages.dk/archive/tools/book/Clilstore_EN.pdf.

Griva, E., & Semoglou, K. (2013). Foreign language and Games: Implementing physical activities of creativity at early years (In Greek). Thessaloniki: Kyriakidis Editions.

Griva, E., & Kasvikis, K. (2015). CLIL in primary education: Possibilities and challenges for developing L2/FL skills, history understanding and cultural awareness. In N. Bakić-Mirić & D. Erkinovich Gaipov (Eds.), Current trends and issues in education: an international dialogue (pp. 125-140). Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Grugeon, E., & Gardner, P. (2000). The art of storytelling for teachers and pupils. London: David Fulton.

Halliwell, S. (1992). Teaching English in the primary classroom. London: Longman.

Järvinen, H. (2007). Language in content and language integrated learning (CLIL). In D. Marsh & D. Wolff (Eds.), Diverse Contexts – Converging Goals: CLIL in Europe (pp. 185-200). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Kiraz, A., Güneyli, A., Baysen, E., Gündüz, S., & Baysen, F. (2010). Effect of science and technology learning with foreign language on the attitude and success of students. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2, 4130–4136.

Koki, S. (1998). Storytelling: The Heart and Soul of Education. Pacific Resources for Education and Learning, U.S. Dept. of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement, Educational Resources Information Center.

Korosidou, E., & Griva, E. (2013). "My country in Europe": A content-based project for teaching English as a foreign language to young learners. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 4(2), 229-244.

Korosidou, E., & Griva, E. (2014). CLIL approach in primary education: Learning about Byzantine art and culture through a foreign language. Studies in English Language Teaching, 2(2), 216-232.

Lasagabaster, D. (2008). Foreign language competence in content and language integrated courses. The Open Applied Linguistics Journal, 1, 31-42.

Lo, Y.-Y., & Murphy, V. A. (2010). Vocabulary knowledge and growth in immersion and regular language-learning programmes in Hong Kong. Language and Education, 24, 215–238.

Luong, B. H. (2009). The application of games in grammar review lessons for sixth graders. (Unpublished master's thesis). Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City.

Maillat, D. (2010). The pragmatics of L2 in CLIL. In C. Dalton-Puffer, T. Nikula, & U. Smit (Eds.), Language use and language learning in CLIL classrooms (pp. 105-124). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Marsh, D. (2000). An introduction to CLIL for parents and young people. In D. Marsh & G. Lange (Eds.), Using languages to learn and learning to use languages (pp. 1-16). Jyvaskyla: University of Jyvaskyla.

Marsh, D., & Frigols, M.-J. (2007). CLIL as a catalyst for change in language education. Babylonia, 3, 33–37.

Mattheoudakis, M., Alexiou, T., & Laskaridou, C. (2014). To CLIL or not to CLIL? The case of the 3rd Experimental Primary School in Evosmos. In N. Lavidas, T. Alexiou, & A. Sougari (Eds.), Selected papers from the 20th International Symposium of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics (pp. 215-234). Versita Publications.

McWilliams, B. (1996). Some Basic Principles for Storytellers. Retrieved from http://www.eldrbarry.net/clas/ecem/bpsc.pdf.

Mehisto, P., Marsh, D., & Frigols, M. (2008). Uncovering CLIL: Content and language integrated learning in bilingual and multilingual education. Oxford: Macmillan.

Moore, F. P. (2009). On the emergence of L2 oracy in bilingual education: A comparative analysis of CLIL and mainstream learner talk. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla.

O'Malley, J., & A. Chamot. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Orlick, T. (2006). Cooperative games and sports: Joyful activities for everyone. Champaign,IL: Human Kinetics.

Papadopoulos, I., & Griva, E. (2014). Learning in the traces of Greek culture: A CLIL project for raising cultural awareness and developing L2 skills. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 8, 76-92.

Pedersen, E. M. (1995). Storytelling and the art of teaching. English Teaching Forum, 33(1), 2-5.

Richards, J. C. (1991). Towards reflective teaching. The Teacher Trainer, 5(3), 4-8.

Richards, J. (2006). Communicative language teaching today. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J., & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schiller, P. (1999). Start smart: Building brain power in the early years. Beltsville, MD: Gryphon House.

Scott, W., & Ytreberg, L. H. (1994). Teaching English to children. London: Longman.

Skehan, P. (1996). A framework for the implementation of task-based instruction. Applied Linguistics, 17, 38-62.

Slattery, M., & Willis, J. (2001). English for primary teachers: A handbook of activities and classroom language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stoyle, P. (2003). Storytelling: Benefits and tips. British Council BBC Teaching English. Retrieved from www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/storytelling-benefits-tips.

Swain, M. (1993). The output hypothesis: Just speaking and writing aren't enough. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 50, 158 -164.

Sweeney, A. (2005). Using stories with young learners–without storybooks. English!, 12-15.

Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2009). Playing to learn: A review of physical games in second language acquisition. Simulation and Gaming, 40(5), 645-668.

Troncale, N. (2002). Content-based instruction, cooperative learning, and CALP instruction: Addressing the whole education of 7-12 ESL students, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Tsai, Y., & Shang, H. (2010). The impact of content-based language instruction on EFL students' reading performance. Asian Social Science, 6(3), 77-85.

Wang, Y. J., Shang, H. F., & Briody, P. (2011). Investigating the impact of using games in teaching children English. International Journal of Learning and Development, 1(1), 127-141.

Willis, J. (1996). A Framework for task-based learning. Harlow: Longman Pearson Education.

Willis D., & Willis, J. (2007). Doing task-based teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wolff, D. (2005). Approaching CLIL. In D. Marsh et al. (Eds), Project D3–CLIL Matrix. The CLIL quality matrix. Central Workshop Report 6/2005 (pp. 10-25). Available at http://archive.ecml.at/mtp2/CLILmatrix/pdf/wsrepD3E2005_6.pdf.

Wong, V. (2008). Promoting children's creativity through teaching and learning in Hong Kong. In A. Craft, T. Cremin, & P. Burnard (Eds.), Creative learning 3-11 and how we document it (pp. 93-101). Sterling, VA: Trentham.

Wright, A. (1995). Storytelling with children. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.

.JPG)