DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.97Published:

2008-01-01Issue:

No 10 (2008)Section:

Research ArticlesCross-linguistic influence in the writing of an italian learner of English as a foreign language: an exploratory study

Keywords:

Influencia de la lengua materna, transferencia del italiano, inglés como lengua extranjera, escritura. (es).Keywords:

Native language influence, Italian transfer, English as a Foreign Language, writing (en).Downloads

References

Arabski, J. (2006) Language Transfer in Language Learning and Language Contact. In Arabski, J. (ed) Cross-linguistic Influences in the Second Language Lexicon. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Celaya, M.L. (2006) Lexical Transfer and Second Language Profifiency: A Longitudinal Analysis of Written Production in English as a Foreign Language. AEDEAN 29. Proceedings.

Celaya, M.L. (1992) Transfer in English as a Foreign Language: A Study on Tenses. Barcelona: PPU.

Celaya, M.L. & Torras, M.R. (2001) L1 influence and EFL vocabulary. Do children rely more on L1 than adult learners? Proceedings of the XXV AEDEAN Conference. Granada: Universidad de Granada.

Cenoz, J. (2001) The Effect of Linguistic Distance, L2 Status and Age on Cross-linguistic Influence in Third language Acquisition. In Cenoz, J. et al., (eds) Cross-linguistic Influence in Third Language Acquisition: Psycholinguistic Perspectives. Clevedon:Multilingual Matters.

Corder, S. P.(1993) A Role for the Mother Tongue. In Gass, S and Selinker, L. (eds) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Volume 5. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

De Angelis, G & Selinker, L. (2001) Interlanguage Transfer and Competing Linguistic Systems in the Multilingual Mind. In Cenoz, J. et al., (eds) Crosslinguistic Influence in Third Language Acquisition: Psycholinguistic Perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Dechert, H. (2006) On the Ambiguity of the Notion `Transfer'. In Arabski, J. (ed) Cross-linguistic Influences in the Second Language Lexicon. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Faerch, C. & Kasper, G. (1986) Cognitive Dimensions of Language Transfer. In Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (eds). Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Gabrys-Barker, D. (2006) The Interaction of Languages in the Lexical Search of Multilingual Language Users. In Arabski, J. (ed) Cross-linguistic Influences in the Second Language Lexicon. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Gass, S. & Selinker, L. (1993) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Gundel, J & Tarone, E. (1993) Language Transfer and the Acquisition of Pronouns. In Gass, S and Selinker, L. (eds) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Volume 5. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Jarvis, S & Pavlenko, A. (2008) Crosslinguistic Influence in Language and Cognition. New York: Routledge

Jin, H. (1994) Topic-prominence and Subject-prominence in L2 acquisition evidence of English-to-Chinese typological prominence. Language Learning (44) 101-112

James, C. (1998) Errors in Language Learning and Use. London & New York: Longman,

Jordens, P. (1986) Production Rules in Interlanguage: Evidence from Case Errors in L2 German. In Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (eds). Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Kellerman, E. (1977) Toward a characterization of the strategy of transfer in second language learning. Interlanguage Studies Bulletin (2) 58-145.

Kellerman, E. (1978) Transfer and non-transfer: where we are now. Studies in Second Language Acquisition (2) 37-57

Kellerman, E. (1983) Now you see it, now you don't. In Gass & Selinker (eds) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (1986) Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Kean, ML. (1986) Core Issues in Transfer. In Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (eds). Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Koda, K. (1997) Orthograsphic Knowledge in L2 Lexical Processing: A Cross-linguistic perspective. In Coady, J. & Huckin, T. (eds) Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition. Cambridge: CUP.

Kohn, K (1986) The Analysis of Transfer. In Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (eds). Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Liu, S. (2001) Studies on Transfer in Second Language Acquisition. Guangxi Normal University Journal, (3) pp. 1-29

Odlin, T. (1989) Language Transfer: Crosslinguistic Influence in Language Learning. Cambridge: CUP.

Ortega, M. (2008) Cross-linguistic influence in multilingual language acquisition: The role of L1 and non-native languages in English and Catalan oral production. Íkala, revista de lenguaje y cultura 13 (19), pp. 121-142

Ringbom, H. (2006) The Importance of Different Types of Similarity in Transfer Studies. In Arabski, J. (ed) Cross-linguistic Influences in the Second Language Lexicon. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Ringbom, H. (2001) Lexical Transfer in L3 Production. In Cenoz, J. et al., (eds) Crosslinguistic Influence in Third Language Acquisition: Psycholinguistic Perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Ringbom, H. (1987) The Role of the First Language in Foreign Language Learning. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Ringbom, H. (1986) Crosslinguistic Influence and the Foreign Language Learning Process. In Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (eds). Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Slobin, D. (1985). The Crosslinguistic Study of Language Acquisition. Volume 1. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, New York.

Vigliocco, G; Butterworth, B; & Semenza, C. (1995) Constructing Subject-Verb Agreement in Speech: The Role of Semantic and Morphological Factors. In Journal of Memory and Language. (34) pp. 186-215

Xiao, M. (2004) Comparative study of English and Japanese/Korean speakers' acquisition of null subjects and null objects in Chinese. Unpublished M.A. thesis, Department of Linguistics, Ohio University. (Contact lingdept@ohio.edu for availability)

Zobl, H. (1993) Prior Linguistic Knowledge and the Conservatism of the learning Procedure: Grammaticality Judgements on Unilingual and Multilingual learners. In Gass, S. & Selinker, L. (eds) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Research Articles

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2008 vol:10 nro:1 pág:50-72

Cross-linguistic influence in the writing of an Italian learner of English as a foreign language: An exploratory study

Claudia Marcela Chapetón

M.A, Language Department at the Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, Colombia.E-mail: cchapeton@pedagogica.edu.co

Abstract

This paper is based on the analysis of the nature of the first language influence on the written production of an Italian learner of English as a foreign language. The goal of the present exploratory study is to examine how cross-linguistic influence manifests itself at the level of syntax and lexis. Findings suggest that forms and meanings in the L2 are expressed and shaped by the learner’s knowledge and use of the foreign language as well as by the influence of the mother tongue.

Key words: Native language influence, Italian transfer, English as a Foreign Language, writing.

Resumen

Este artículo se basa en el análisis de la naturaleza de la influencia de la lengua primera en la producción escrita de un estudiante de inglés como lengua extranjera cuya lengua primera es el italiano. El propósito principal es examinar cómo la influencia croslingüística se manifiesta a nivel sintáctico y léxico. Los resultados sugieren que tanto la forma como los significados expresados en la lengua extranjera son formados por el conocimiento y el uso de la lengua extranjera y la influencia de la lengua materna.

Palabras clave: Influencia de la lengua materna, transferencia del italiano, inglés como lengua extranjera, escritura.

Introduction

The role of the first language in foreign language learning has received important attention from numerous theorists and researchers from more than fifty years. It has also played an important part on the overall understanding of second and third language acquisition. Studies on language transfer and research on cross-linguistic influence have shed light on the general view of the processes involved when learning a language different from the mother tongue. The main purpose of this exploratory study is to identify and describe the kind of cross-linguistic influence in the writing of an Italian learner of English as a foreign language. Therefore, I will present a brief literature review on the main concepts which are central to this paper, a description of the characteristics of the participant, the instruments and procedures for data collection, the analysis of the data, the results and final comments.

Theoretical Framework

L1 influence and language transfer

Second language research of the seventies and early eighties directed its attention to uncovering whether, under what conditions, and in what way prior linguistic experience influenced the acquisition route (Zobl 1980; Kellerman, 1978; Gass 1979; as cited by Zobl 1993:176). In the late eighties, researchers were also intrigued by the processes underlying second language learning and its relation to the mother tongue. Ringbom (1987) claimed that the second language learner was constantly seeking to facilitate his task by making use of previous linguistic knowledge consisting of what s/he already knew about the target language (L2) and of what s/he knew about the mother tongue (L1). It was clear that the L2 learner did not have to start from zero as s/he could be able to relate a new item or task in the L2, -even if being at the early stages of learning-, to existing previous linguistic knowledge from L1 or possible other languages.

Ringbom (1987) placed crucial importance on the similarities between the languages, suggesting that those similarities should be the core of investigation. He found that the L1 influence could manifest itself in various ways depending greatly on how similarities were perceived by the L2 learner and how those similarities could affect the learning process. Odlin (1989:27) agreed by stating that the influence arises from “a learner’s conscious or unconscious judgment that something in the native language and something in the target language are similar”, if not actually identical.

In contrast, Kellerman (1983) argued that there were certain conditions on L1 influence that went beyond mere similarity and dissimilarity of the languages in question, thus, involving the learner as an active participant in the learning process. He claimed that the L2 learner was able to make decisions about what could and could not be transferred. All in all, the less the learner knows about the target language, the more s/he is forced to draw upon any other prior linguistic knowledge s/he possesses. This prior knowledge may also include other foreign languages (LN) previously learned and, both the LN influence and the L1 influence, would be more evident at the early stages of learning.

Language transfer has emerged as an area of study central to the entire discipline of second language acquisition (Gass and Selinker, 1993). Though a fully adequate definition of transfer seems unattainable without adequate definitions of many other terms, as Odlin (1989) remarks, the term transfer has been defined by various authors and a wide array of studies has been conducted on this matter. (For a discussion on the ambiguity of the term transfer see Dechert, 2006). However, the concept of transfer has its origins in the Contrastive Analysis (CA) hypothesis which was widely accepted in the 1950s and 1960s. As Koda (1997) points out the CA hypothesis, which was deeply rooted in behaviorism, asserts that the principal barrier to L2 acquisition arises from interference factors created by the L1 system, being the L1 regarded as the primary source of confusion.

According to Arabski (2006) language transfer as a linguistic concept has always been considered as a phenomenon which occurs in language learning situations. The author presents two definitions which show the most common behaviorist views of the term as the automatic, uncontrolled, and subconscious use of the past learner behaviors in the attempt to produce new responses in the L2 (Dulay et al., 1882, as cited by Arabski, 2006). First, negative transfer which results in error because of the influence of old, habitual behavior different from the new behavior being learned. And second, positive transfer which in contrast, results in correct performance as the new behavior is the same as the old.

In opposition to the automatic view, and within the cognitive paradigm of the late seventies, transfer was characterized as a problem-solving / decision making procedure, or strategy, utilizing L1 knowledge in order to solve a learning or communication problem in L2 (Jordens, 1977; Kellerman, 1977; Sharwood Smith, 1979; as cited by Faerch and Kasper, 1986).

Odlin (1989) argues that transfer is neither a consequence of habit formation, nor simply a falling back on the native language. Instead, he defines transfer as “the influence resulting from similarities and differences between the target language and any other language that has been previously (and perhaps imperfectly) acquired.” (pp.27). He proposes a classification of outcomes in order to better understand the varied effects that the similarities and differences of the languages can produce. His classification includes three categories. First, positive transfer, that is, the facilitating effect which takes place when the similarities between L1 and the target language (or languages) promote acquisition. For instance, similarities in syntactic structures can facilitate the acquisition of grammar and also, similarities in vocabulary can reduce the time needed to develop good reading comprehension.

Second, negative transfer, which involves divergences from norms in the target language, includes issues such as underproduction or avoidance, overproduction, production errors in speech and writing and, misinterpretation as L1 structures can influence the interpretation of L2 messages leading learners to infer something very different from what speakers of the target language would infer. Misinterpretation may occur, at the writing level, when L1 and L2 word-order patterns differ.

Finally, to better assess the cumulative effects that the similarities and differences of the languages can produce, Odlin (1989) claims that a third category which looks at the length of time required to achieve a high command of a language is needed. To support his argument, he presents a list that shows the maximum lengths of intensive language courses, being Arabic, Japanese, Chinese, Greek and Russian among the example languages which require more number of weeks for native English speakers to achieve a high degree of mastery. This brings into play the role of language distance which refers to the degree of similarity between two languages.

This last assumption is closely related to the concept of psychotypology brought by Kellerman (1983). He suggests two interacting factors which are involved in language transfer. One is the learner’s perception of the nature of the L2 and the other is the degree of markedness of an L1 structure. The perception of the L2 and the distance from the L1 Kellerman refers to as psychotypology (pp.114) Transferability in Kellerman’s framework is a relative notion depending on the perceived distance between the L1 and the L2 and the structural organization of the learner’s L1.

Cross-linguistic Influence

Corder (1993) calls into question the term transfer and suggests mother tongue influence as a neutral and broader term to refer to what has most commonly been called transfer. He asserts that the original theory of transfer assigned a very restricted role to the mother tongue and that it did not cover all the phenomena sufficiently. Gundel and Tarone (1993) agreed by saying “Despite the obviously important role of the first language in second language acquisition, the term `language transfer´ is misleading because it implies a simple transfer of surface `patterns´, thus obscuring the complex interaction between the first and the second language systems and language universals” (pp. 87)

Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (1986) created a theory-neutral term to refer to this important aspect of second language acquisition and called it: “crosslinguistic influence”. They defined it as the interplay between earlier and later acquired languages. This umbrella term includes such phenomena as transfer, interference, avoidance, borrowing, and L2 related aspects. The authors claim that the term cross-linguistic influence (CLI) can be used to label the processes involved regardless of the direction of the influence (L1 ↔ L2). Also, this term welcomes both studies on second and foreign language acquisition extending it to many more types of language contact situations such as naturalistic and tutored. In sum, CLI is presented by Kellerman and Sharwood as a particular domain of investigation in SLA and FLL regarding the theoretical problems associated with identifying and explaining how the native and target languages interact in second language acquisition and performance.

Studies of cross-linguistic influence in SLA have been conducted at all the linguistic levels: phonological, lexical, syntactical and semantic (For a brief account see Liu, 2001). For the purpose of this paper, let us now concentrate on the syntactical and lexical levels only.

Syntax and cross-linguistic influence

Empirical studies of second language syntax have fueled much of the debate regarding language transfer. Liu (2001) presents a brief account on the main research interests regarding cross-linguistic influence at the level of syntax in the seventies:

“In terms of linguistic transfer on the syntactical level, Ravem (1971) documented that the learner’s NL played a certain role in the formation of his second language syntax. Hakuta (1974) also demonstrated that there is a firm relationship between L1 transfer and the emergence of structure in second language acquisition. In addition, Larsen-Freeman (1975) evidenced such a relationship through the learner’s learning of English grammatical morphemes. To Gass (1979), transfer helped us to see the grammatical element universal in human languages.” (pp.3)

In his discussion on the notion of syntactic transfer, Odlin (1989) reviews empirical studies which have showed considerable evidence both for positive and negative transfer related to issues such as articles, word-order, relative clauses and negation. He affirms that word order, for instance, has been one of the most intensively studied syntactic properties in SLA research and that it has been useful for a better understanding of transfer. In the case of English and Italian, the two languages of interest in this paper, the basic word order, for both languages, is one in which grammatical subjects precede verbs (or verb phrases), which in turn precede objects, and thus the abbreviation which characterizes the order of constituents in a clause is SVO. Odlin also brings into play the concept of word-order rigidity. English word order is quite rigid and “in contrast to some languages, word order is affected little by pragmatic factors.” (Slobin, 1985:28) Instead, Italian word order is flexible. It allows syntactic structures such as:

SVO Io mangio la mela I eat the apple.

VOS Mangio la mela io *eat the apple I

OVS La mela la mangio io * The apple it eat I

VSO Mangio io la mela * eat I the apple

In Italian, SVO, VOS, and OVS orders are allowed in conversational speech, and VSO is permitted in written prose. In support of this argument, Vigliocco et al., (1995) present the following examples of the past tense formation in Italian:

SVO Giovanni ha mangiato la mela. John has eaten the apple.

VOS Ha mangiato la mela Giovanni. *Has eaten the apple John.

OVS L’ha mangiata Giovanni. *(the aple) has eaten John.

VSO Ha mangiato Giovanni la mela. *Has eaten John the apple.

When the language has freer word-order, as is the case of Italian, the grammatical position of the subject may be less important and lexico-semantic influences correspondingly more important. (Vigliocco et al., 1995)

According to Odlin (1989), rigidity appears to be a transferable property. Speakers of a flexible language may use several word orders in English even though English word order is quite rigid. Odlin here exemplifies by mentioning some studies of production such as the one carried out by Granfors and Palmber in 1976, who listed numerous errors in English word order in a guided composition task performed by native speakers of Finish, a flexible SVO language. Research on Italian and Spanish workers in Germany also provides strong evidence of transfer of basic word-order patterns (Meisel, Clahsen, and Pienemann 1981 as cited by Odlin, 1989). The SVO order of Italian and Spanish appears to have influenced some learners’ use of SVO instead of SOV order in German subordinate clauses.

Another focus of attention regarding syntactic transfer has been the issue of the pro-drop parameter. The first study that explicitly examined the occurrence of zero and overt pronouns in the interlanguage of second language learners was conducted by Gundel and Tarone (1993). Their purpose was to provide further insight into the role of the L1 in L2 acquisition by investigating the acquisition of pronouns by second language learners. They found that learners whose L1 do not allow null elements also sometimes produce null elements in the L2. Few studies have investigated syntactic transfer in the acquisition of an L2 that does allow null subjects (e.g Chinese, Japanese or Korean). Jin (1994) for instance, found that Learners whose L1 was English, a language which does not allow null elements, excessively overproduce subject and object pronouns in the L2. Similarly, Xiao’s (2004) comparative study, clearly indicated that learners of Chinese whose L1 was English used subject and object pronouns far more frequently than learners whose L1 was Japanese or Korean.

One of the most striking differences between a language such as English and a language such as Italian is the fact that in English, except for the imperatives, it is necessary to have an overt subject in sentences, whereas in Italian it is not. According to Kean (1986) this difference constitutes one of the three facets of the pro-drop parameter. In addition to allowing empty or null subjects, pro-drop languages also allow free inversion of overt subjects in simple sentences and admit apparent violations of the that-trace filter; nonpro-drop languages admit none of these phenomena in well-formed sentences. The examples below illustrate this typological distinction: (Examples from White, 1983 as cited by Kean, 1986).

- Empty subjects: Verra *Will come

- Free inversion in simple sentences: Verra Gianni *Will come Gianni

- Apparent violations of the that-trace filter Chi credi che verra? *Who do you think that will come?

All three phenomena are characteristic of pro-drop languages. Kean (1986) suggests that a speaker of Italian learning English would be predicted to show transfer of pro-drop in the grammar of the early interlanguage.

Syntactic transfer has also been studied at the level of tenses. Celaya (1992) analyzed longitudinal and cross-sectional data on the acquisition and use of four English tenses by Catalan Spanish speakers. One important finding in her study is the fact that English tenses are used erroneously in some cases without any influence from the L1, instead, other factors such as the social, educational and linguistic may affect in several ways. However, her data showed that transfer seems to be favored by the different meaning of tenses in the languages and that learners with low proficiency in the L2 draw from their L1 in the use of the present continuous while transfer in the use of simple past tense was more evident at higher levels.

In Italian, as in Spanish, both the present tense and the equivalent to the present continuous can be used to express current activity. While in Italian both forms are exchangeable without excluding the progressive meaning, English progressive tense is expressed with the use of be + gerund. The Italian speaker, as the Spanish one as pointed out by Celaya (1992) will probably transfer this usage into English and produce sentences such as:

*I eat now instead of I’m eating now as I’m eating in Italian could either be:1) Mangio 2) Sto mangiando.

Lexis and cross-linguistic influence

In terms of linguistic transfer at the lexical level, Ringbom’s work has been one of the most influential contributions. In his study of comparable groups of learners of English as a foreign language with different L1s (Finnish and Swedish), he found great predominance of L1 influence on lexis. Ringbom (1987) argues that the cross-linguistic similarities between L1 and L2 can be assumed to play an important role in the storage of lexical items. He defines lexical knowledge as “a system or set of systems which can be used for the purposes of both comprehension and production.” Ringbom (1986) clarifies that lexical influence can manifest itself in other more complex ways which go beyond merely formal similarity between individual items. Following his discussion of cross-linguistic influence on production, he proposes a distinction between overt and covert cross-linguistic influence which is based on whether or not similarity is perceived by the learner: “Whereas covert cross-linguistic influence is due to lack of perceived similarity, overt cross-linguistic influence depends on perceived similarities” (Ringbom, 1986:50)

According to Ringbom (1987), overt cross-linguistic influence can be divided into transfer and borrowing as the end-points on a continuum in which some elements in between are present. Those elements are semantic extensions, loan translations, complete language shift, hybrids, blends and relexifications, and false friends. In a later study, Ringbom (2001) observes that lexical transfer errors can be related to form and meaning distinctively and he proposes a new classification of five categories: language switches, coinages (blends and hybrids) deceptive cognates (false friends), calques and semantic extensions, being these two last categories related to transfer of meaning. Gabrys-Barker (2006) applies Ringbom’s classification in her study of lexical processing in the context of trilingual language users in order to analyze translation equivalents produced by her students.

In his discussion of transfer in foreign language learning, Ringbom (2006) distinguishes between different types of cross-linguistic similarity relations which refer to items and systems; form and meaning; L1 vs. L2 transfer in L3 learning; modes of comprehension and production; and perceived or assumed similarity and objective similarity. He argues that the role played by those relations varies both quantitatively and qualitatively depending on the way they are interlinked. Moreover, Ringbom (1986) claims that in lexical transfer, either L2 items are combined according to the pattern of L1 combinations, or the semantic structure of an L1 word is transferred to the L2 word without any formal similarity being involved.

As I see it, this last assumption is closely related to one of the two subtypes of interlanguage transfer brought by De Angelis and Selinker (2001) which is “morphological interlanguage transfer”. They defined it as “the production of interlanguage forms in which a free or bound non-target morpheme is mixed with a different free or bound target morpheme to form an approximated target language word”. In their study of two adult multilinguals speaking in Italian, they found two types of interlanguage influence. First, the use of an entire non-target interlanguage word which they classified as lexical interlanguage transfer. And second, the use of non-target free or bound morphemes in the formation of a target word.

Celaya and Torras (2001) studied the role of the L1 (Spanish and Catalan) in EFL open class words in order to analyze the differences in number and types of lexical transfer at three different ages. Their findings suggest that children rely more on the L1 when the type of transfer is more direct (misspellings) while adults and adolescents draw on the L1 more than children in the process which combines L1 and L2 knowledge (coinages). However, they highlight that L1 influence in EFL written vocabulary “may be affected not only by age alone but also by different methodologies” that take place within the classroom practices. In a more recent longitudinal study, Celaya (2006) analyzes the relationship between the influence of the two L1s (Spanish and Catalan) and L2 proficiency levels in EFL open class words. Her findings reveal that although L1 influence decreases as the proficiency levels in L2 increase, there is a nonstandard form (calques) which does not decline after 726 hours of instruction. Thus, the author suggests that L1 influence and L2 proficiency interrelate in diverse ways depending on the type of non-standard word.

In these two studies which are part of the BAF project at the University of Barcelona, the researchers analyzed their data on the basis of James’s classification of errors (1998) creating a very useful taxonomy to classify lexical transfer into four categories: misspelling, borrowing, coinage and calque . Thus, I have found Celaya and Torras’ work on lexical transfer very illuminating for the development of this paper as they have studied lexical transfer in the context of the writing production of low proficiency learners of English as a foreign language in instructional settings.

Assuming that, and as it has been established beyond doubt by several authors and researchers, that cross-linguistic influence does occur in the language learning process, my aim in this exploratory study, conducted at a small-scale, is to answer the two following research questions:

a. How does L1 influence the written performance of an Italian learner of EFL at the syntax level?

b. How does L1 influence the written performance of an Italian learner of EFL at the lexical level?

Methodology

The participant

The subject is a native speaker of Italian. He is a fourteen year-old boy from a small city in the south of Italy. Italian is his L1 and it is the language he uses for daily communication with his parents, siblings, relatives and friends. Italian is also the language used for school instruction. The subject’s L2 is English which he has been learning as a foreign language at school. He attends an Italian state-funded school which is not bilingual. He has an elementary to preintermediate proficiency level of English. He has not taken extra-curricular or additional English courses in Italy. He has not traveled to any English speaking country so far. Thus, his knowledge of English is only due to formal instruction at school.

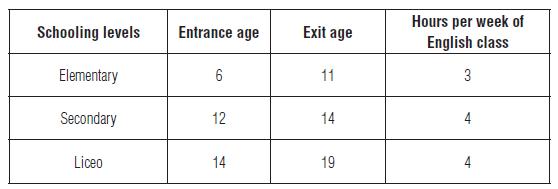

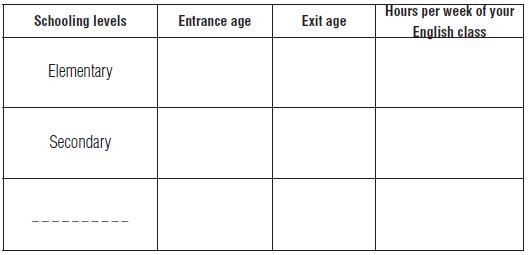

Table 1 shows the three different school levels the subject has undergone, the entrance and exit ages of each one of those levels, and the number of hours per week of the English class at school. The subject takes four hours of English per week this academic year. The average number of hours per week is 3.6 in eight years of s chooling.

Data collection: The instrument and the procedures

The sample data were collected from a written composition task on a given topic. The topic of the composition was “My favorite movie”. The written composition task was time-constrained, thus, the subject was allowed a maximum of 15 minutes to perform and fulfill the task. A comfortable environment to develop the task was set. The subject was asked to write freely without the use of a dictionary or any other additional source of information such as grammar or reference books. The instructions were given in English and in order to make sure that both the procedure and the topic were clear, further clarifications at the oral level were provided in the target language by the researcher. The participant was allowed to ask any clarification questions before starting the written composition task. Thus, the participant was asked to write a description of his favorite movie and to tell the reasons why he likes it.

In addition, a personal information questionnaire was designed, piloted and revised for validation purposes. The questionnaire was answered by the participant on a previous session to elicit information on his language dominance and his linguistic background, and it was also used to create a profile of the subject. It included questions regarding his place of birth, age, native language, and the language used for education, communication and daily interaction. It also provided information on schooling; the hours of English instruction per week; and the self-perceived proficiency level in the target language (see the appendix).

Data Analysis

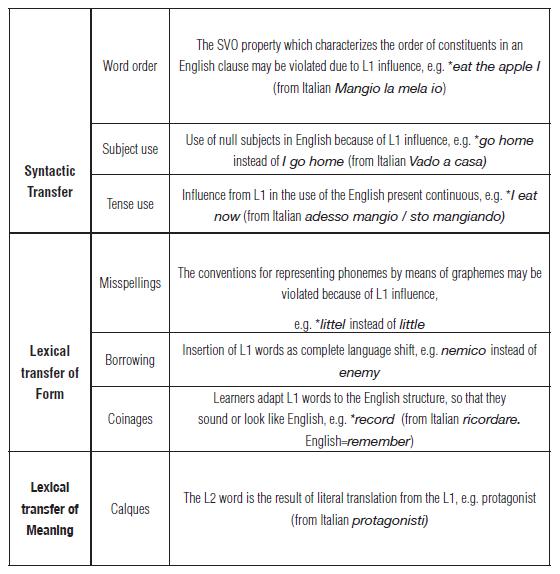

In line with the literature reviewed above and having the previous two research questions in mind, the focus of this analysis was twofold. First, at the syntactic level, three main issues were at the core: Word order; Subject use; and Present Continuous Tense use. Second, at the lexical level Celaya and Torras’ classification (2001) was taken and adapted by considering also Ringbom’s (2001) distinction between transfer of form and transfer of meaning. Thus, at the level of lexical transfer of form misspellings, borrowing and coinages were at the core while the use or presence of calques was the main element to analyze with regards lexical transfer of meaning. Table 2 shows a brief description of the elements considered as the basis for the analysis of data in this small-scale exploratory study:

Findings and Discussion

The previous classification (as shown in Table 2) was used to identify the syntactic and lexical transfer present in the written task performed by the Italian learner of EFL.

An analysis of the three main issues regarding syntactic transfer reveals that one of the most common syntactic properties that influenced the learner’s interlanguage was that of the pro-drop parameter. In cases in which subjects such as “I” or “they” were needed, the learner would omit them. In terms of word-order, I may say that most of the learner’s sentences were correctly constructed following the SVO pattern of English. There was only one instance in which a different pattern was used (see discussion below). Regarding the use of the English tense present continuous, there is an instance in which it was correctly constructed (be + gerund) but with errors in meaning (1) and there was another instance in which there were both errors in form and meaning (2):

(1) *This film is working for *record *antica Rome.

Italian: Questo film è stato fatto per ricordare l’antica Roma.

English: This film has been made to remember the antique Rome.

(2) *I have studying Rome.

Italian: Ho studiato Roma.

English: I have studied Rome.

The results also suggest that syntactic transfer regarding word-order and subject use may not appear in isolation, instead, they can be seen together in only one clause as in the following example (3):

(3) *This film like it . Italian: Questo film mi piace. English: “I like this film” O(SØ)V OSV SVO

In the production of this clause, the learner uses a word order which does not correspond to the SVO pattern of English. The L1 more flexible word-order pattern has influenced his construction. Also, in his production of this clause, he drops the subject even if an indirect object pronoun (mi) is necessary in his L1.

A very common pattern found at the syntactic level was related to subjectverb agreement (SVA). As Jordens (1986) explains, in English, this means that both the subject and the finite verb should have the same number, i.e. both should occur either with a singular form or with a plural form. In his study, Jordens found that agreement errors in L1 Dutch parallel to case errors in L2 German are evidence for the fact that L1 processes of incremental sentence production are responsible for specific types of case errors in L2 German. The following examples illustrate the agreement errors produced by the Italian subject in the present study:

(4) * My favorite film is much

Italian: I miei films preferiti sono molti

English: My favorite films are many

(5) * This *villagge have...

Italian: Questo villaggio ha...

English: This village has...

(6) * a druids

Italian: un druido

English: a druid

In their study on subject verb agreement Vigliocco et al (1995) explain that while plurality of nouns in English is almost always morphologically marked, in Italian, a greater range of words have the same form in singular and plural. This is the case of the Italian word film which is classified as an Invariant Noun. This issue might explain the reason for this number agreement error in sentence (4).

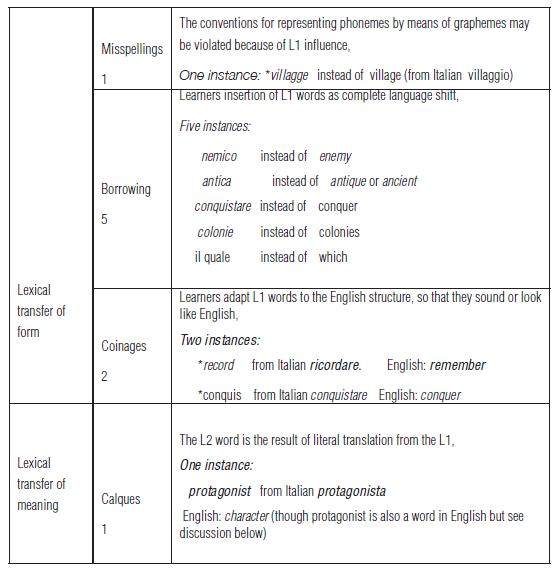

In response to the second question posed in this paper, an analysis of lexical transfer of form and meaning was carried out following the previously described classification. Table 3 shows the classification of types of influence identified along with the number of instances in which they occurred. It also shows the examples taken from the data to illustrate each case.

As it can be seen in table 3, a total of eight instances of lexical transfer of form were identified whereas one instance of lexical transfer of meaning was present. Regarding transfer of form, borrowings appear as the most frequent type with five instances, followed by coinages with only two. The participant’s insertion of intact L1 words (borrowings) and the use of created words (coinages) may be explained by the necessity of filling a gap of lexical knowledge in L2 and the reliance on L1 resources to overcome problems with vocabulary in an attempt to fulfill his communicative needs. These needs might be related to the type of exposure to the foreign language in instructional settings and the relatively low proficiency level of the participant.

In terms of lexical transfer of meaning, only one instance was identified. In English, the word character is most commonly used when referring to films while the English word protagonist, though useful in the context of films as well, is more related to literature and it is used to refer to the leading character, hero, or heroine of a drama or other literary work. In Italian, the word protagonista is used in those two contexts indistinctively. However, the Italian word personaggio is more appropriate to refer to literature related issues. Ringbom (2001) points out that this kind of transfer of meaning might happen when the learner is aware of the existing target word form, but not of the semantic restriction.

Final Comments and Pedagogical Implicati

ons This paper has addressed the cross-linguistic influence in the writing of an Italian learner of English as a foreign language. Since this has been an exploratory study conducted at a small-scale, it is worth clarifying that the following comments are not conclusive and that a bigger dataset would be needed in order to make any generalizations. Nevertheless, after an analysis of the sample data, it was possible to identity instances of syntactic and lexical transfer and also, to suggest various methodological issues that should be considered for further research.

At the syntactic level, it was observed that null subjects, allowed in the participant’s L1, were used in the learner’s construction of English sentences which, contrary to Italian, it is a non pro-drop language. Also, his L1 might have influenced his use of the English present progressive tense as it presented errors in form and of meaning. It was also observed that L1 influence in word order and subject use may appear jointly in the production of a single sentence. Results also suggested that errors in subject verb agreement might occur as a result of L1 influence.

Considering the L1 influence at the lexical level, it was observed that there were instances for both transfer of form and transfer of meaning. Borrowings, classified as transfer of form, are more frequent in the writing production of this learner in relation to the other categories. Also, there was only one instance in which transfer of meaning was likely to occur.

However, as further research concerns, it is important to clarify that in order to rigorously identify which kind of transfer is involved in the interlanguage of a learner, as Kohn (1986) suggests, carefully conducted longitudinal case studies will be invaluable. Also, a closer look and a detailed description of the methodology and type of exposure to the foreign language in instructional settings will be necessary for sound conclusions to be drawn. That is, it would be of critical importance to previously assess the subject’s level of English using a reliable and appropriate diagnosis test, as well as to gather systematic information about the subject’s previous experience in writing at school.

Similarly, after the writing (or task performance), it would be useful to explore and/or discuss with the learner, the possible reasons for instances of transfer to occur. As Grabrys-Barker (2006) suggests, there are several factors that might determine the appearance of transfer. For instance, when the TL (target language) element has not been acquired because of lack of input; when it has been internalized but not activated at the moment of performance; and/or when the patterns acquired are not sufficient/complete and do not account for all necessary applications. Other factors investigated also in multilingual or third language acquisition research (e.g. Ortega, 2008; Cenoz, 2001) such as real and perceived language distance, recency, second language (L2) status, and the effects they have on the choice of the source language in cross-linguistic influence could be considered for further research as well.

Moreover, studying cross-linguistic influence can go beyond the syntactic and lexical levels. Studies on transfer at the pragmatic and conceptual levels are promising and innovative research lines (see Jarvis & Pavlenko, 2008 for an account on the new and classic work on cross-linguistic influences on language and thought).

To conclude, studying the cross-linguistic influence and the interlanguage of learners might have several implications for the EFL classroom. First, the results of such research might be useful in making informed decisions with regards to curriculum planning and design and textbook selection. For instance, those decisions may consider which kind of transfer is involved in the interlanguage of a specific community of learners and which are the factors and reasons for its occurrence. Also, it may be relevant for teachers to minimize negative attitudes towards the learners’ insertion of, for instance, intact L1 words (borrowings) and the use of created words (coinages) which may explain their need to fill a gap of lexical knowledge in L2, and understand their reliance on L1 resources as positive attempts to accomplish their communicative purposes. Finally, classroom activities should be designed to foster and increase learners’ own awareness of the linguistic choices they make when communicating in the target language and the significance of these choices.

Glossary

borrowing: a type of lexical transfer of form characterized by the use of an L1 word without any phonological and/or morphological adaptation. That is, the insertion of L1 words as complete language shift.

calque: The L2 word is the result of literal translation from the L1. According to Ringbom (2001) it is a type of lexical transfer of meaning that takes place when there is awareness of existing target language form but not of semantic/collocational restrictions.

coinage: a type of lexical transfer error that occurs when there is insufficient awareness of intended linguistic form and so a modified form of an L2 word is used (Ringbom, 2001)

markedness: it relates to the degree to which a form, feature, or structure is marked, special, atypical, or language-specific versus being unmarked, basic prototypical, or universal (Kelerman, 1983). Studies have shown that marked structures (e.g. complex consonant clusters) in a target language are more difficult to acquire than unmarked structures and this condition often interacts with transfer (See Jarvis & Pavlenko, 2008)

misspelling: these are the type of errors committed by learners when they are operating the graphological system when writing words in English. As a result of the problems they have with the English encoding system, they violate the conventions for representing phonemes by means of graphemes, e.g. braun instead of brown (Celaya and Torras, 2001)

that-trace filter: it relates to the phenomenon that the complementizer (that) cannot be followed by a trace (except in relative clauses) in some languages (e.g. English). Thus, in languages showing the that-trace effect, a subject cannot be extracted when it follows that. Languages like Spanish and Italian do not show the that-trace effect, as is illustrated in the following examples: ¿quién crees que vendrá?/Chi credi che verra? Vs Who do you think will come? *Who do you think that will come?

pro-drop parameter: this notion refers mainly to the possibility exhibited by some languages of suppressing lexical subjects. It is present in languages like Spanish and Italian which allow null subjects, in contrast to English which does not allow null subjects: Ayer compré un libro vs I bought a book yesterday. Most of the studies that have investigated this phenomenon have examined learners whose L1 allows null subjects and whose L2 does not relying mainly on grammaticality judgment tests. Few studies have been based on production data (See Jarvis & Pavlenko, 2008 for an account on the main research interests regarding cross-linguistic influence at the syntactic level)

References

Arabski, J. (2006) Language Transfer in Language Learning and Language Contact. In Arabski, J. (ed) Cross-linguistic Influences in the Second Language Lexicon. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Celaya, M.L. (2006) Lexical Transfer and Second Language Profifiency: A Longitudinal Analysis of Written Production in English as a Foreign Language. AEDEAN 29. Proceedings.

Celaya, M.L. (1992) Transfer in English as a Foreign Language: A Study on Tenses. Barcelona: PPU.

Celaya, M.L. & Torras, M.R. (2001) L1 influence and EFL vocabulary. Do children rely more on L1 than adult learners? Proceedings of the XXV AEDEAN Conference. Granada: Universidad de Granada.

Cenoz, J. (2001) The Effect of Linguistic Distance, L2 Status and Age on Cross-linguistic Influence in Third language Acquisition. In Cenoz, J. et al., (eds) Cross-linguistic Influence in Third Language Acquisition: Psycholinguistic Perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Corder, S. P.(1993) A Role for the Mother Tongue. In Gass, S and Selinker, L. (eds) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Volume 5. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

De Angelis, G & Selinker, L. (2001) Interlanguage Transfer and Competing Linguistic Systems in the Multilingual Mind. In Cenoz, J. et al., (eds) Cross-linguistic Influence in Third Language Acquisition: Psycholinguistic Perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Dechert, H. (2006) On the Ambiguity of the Notion ‘Transfer’. In Arabski, J. (ed) Cross-linguistic Influences in the Second Language Lexicon. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Faerch, C. & Kasper, G. (1986) Cognitive Dimensions of Language Transfer. In Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (eds). Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Gabrys-Barker, D. (2006) The Interaction of Languages in the Lexical Search of Multilingual Language Users. In Arabski, J. (ed) Cross-linguistic Influences in the Second Language Lexicon. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Gass, S. & Selinker, L. (1993) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Gundel, J & Tarone, E. (1993) Language Transfer and the Acquisition of Pronouns. In Gass, S and Selinker, L. (eds) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Volume 5. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Jarvis, S & Pavlenko, A. (2008) Crosslinguistic Influence in Language and Cognition. New York: Routledge

Jin, H. (1994) Topic-prominence and Subject-prominence in L2 acquisition evidence of English-to-Chinese typological prominence. Language Learning (44) 101-112

James, C. (1998) Errors in Language Learning and Use. London & New York: Longman,

Jordens, P. (1986) Production Rules in Interlanguage: Evidence from Case Errors in L2 German. In Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (eds). Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Kellerman, E. (1977) Toward a characterization of the strategy of transfer in second language learning. Interlanguage Studies Bulletin (2) 58-145.

Kellerman, E. (1978) Transfer and non-transfer: where we are now. Studies in Second Language Acquisition (2) 37-57

Kellerman, E. (1983) Now you see it, now you don’t. In Gass & Selinker (eds) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (1986) Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Kean, ML. (1986) Core Issues in Transfer. In Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (eds). Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Koda, K. (1997) Orthograsphic Knowledge in L2 Lexical Processing: A Cross-linguistic perspective. In Coady, J. & Huckin, T. (eds) Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition. Cambridge: CUP.

Kohn, K (1986) The Analysis of Transfer. In Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (eds). Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Liu, S. (2001) Studies on Transfer in Second Language Acquisition. Guangxi Normal University Journal, (3) pp. 1-29

Odlin, T. (1989) Language Transfer: Crosslinguistic Influence in Language Learning. Cambridge: CUP.

Ortega, M. (2008) Cross-linguistic influence in multilingual language acquisition: The role of L1 and non-native languages in English and Catalan oral production. Íkala, revista de lenguaje y cultura 13 (19), pp. 121-142

Ringbom, H. (2006) The Importance of Different Types of Similarity in Transfer Studies. In Arabski, J. (ed) Cross-linguistic Influences in the Second Language Lexicon. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Ringbom, H. (2001) Lexical Transfer in L3 Production. In Cenoz, J. et al., (eds) Crosslinguistic Influence in Third Language Acquisition: Psycholinguistic Perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Ringbom, H. (1987) The Role of the First Language in Foreign Language Learning. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Ringbom, H. (1986) Crosslinguistic Influence and the Foreign Language Learning Process. In Kellerman, E & Sharwood, M. (eds). Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press.

Slobin, D. (1985). The Crosslinguistic Study of Language Acquisition. Volume 1. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, New York.

Vigliocco, G; Butterworth, B; & Semenza, C. (1995) Constructing Subject-Verb Agreement in Speech: The Role of Semantic and Morphological Factors. In Journal of Memory and Language. (34) pp. 186-215

Xiao, M. (2004) Comparative study of English and Japanese/Korean speakers’ acquisition of null subjects and null objects in Chinese. Unpublished M.A. thesis, Department of Linguistics, Ohio University. (Contact lingdept@ohio.edu for availability)

Zobl, H. (1993) Prior Linguistic Knowledge and the Conservatism of the learning Procedure: Grammaticality Judgements on Unilingual and Multilingual learners. In Gass, S. & Selinker, L. (eds) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Appendix

PERSONAL INFORMATION QUESTIONNAIRE

Please answer the following questions about yourself:

1. What’s your name? ______________________________________

2. How old are you? ______________________________________

3. Where are you from? _____________________________________

4. What’s your native language, that is, the language you speak from birth? ________________ _____________________________________

5. Which language/s do you speak at home? _______________________

With your father?________________ Mother?________________

Brothers or sisters? ______________ Friends? _______________

6. In which language do you feel more comfortable? ________________

Please complete this form about your school instruction

Please circle the option(s) that best describe your self-perceived proficiency in English:

starter

intermediate

elementary

upper-intermediate

pre-intermediate

advanced

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Claudia Marcela Chapetón Castro holds a Masters degree in Applied Linguistics for the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language from the Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas in Bogotá. She is a full-time teacher of English in the Language Department at the Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, Bogotá. She is currently pursuing her Ph.D in Applied Linguistics at the University of Barcelona, Spain.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.