DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.98Published:

2008-01-01Issue:

No 10 (2008)Section:

Research ArticlesFrom pre-school to university: student-teachers’ characterize their EFL writing development

Keywords:

Escritura en inglés, enseñanza de la escritura, enfoques metodológicos para la escritura, escritura de estudiantes practicantes, narraciones biográficas (es).Keywords:

EFL writing, teaching writing, instructional approaches for writing, pre-service teachers’ writing, biographical narratives (en).Downloads

References

Ariza, A. (2005).The process-writing approach: an alternative to guide the students' compositions. Profile, 6, 37-46.

Aldana, A. (2005). The process of writing a text by using cooperative learning. Profile, Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 6, 47-57.

Byrne, D. (1979). Teaching Writing Skills. London: Longman. Cadavid, M; Mcnulty, M; Quinchía, O. (2004). Elementary English language instruction: Colombian teachers' classroom practices. Profile, 5, 37-55.

Cárdenas, M. (2003). Teacher researchers as writers: a way to sharing findings. Colombian Applied linguistics Journal, 5, 49-64.

Cárdenas, R.(2001). Teaching English in primary: are we ready for it? HOW, 8, 1-9.

Clavijo, A. (1998). Teachers' life histories: An important input in the formation of teachers's beliefs. A case of a bilingual teacher. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 1(1), pp.3-20.

Clavijo, A. (2000). Historia y vida: reflexión y praxis del maestro colombiano acerca de la lectura y la escritura. Bogotá: Plaza y Janes.

Clavijo, A. and Torres, E. (2004). Relación entre la adquisición de la lengua materna y el aprendizaje de una segunda lengua. En Clavijo, A y Torres, E (Comp) Aprendiendo a enseñar ingles a niños. Bogota: Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas.

Cohen, L and Manion, L.(1995). Research Methods in Education. London: Routledge.

Gonzalez, A. (2003a). Who is educating EFL Teachers: a qualitative study of in-service in Colombia. Ikala, 8(14),153-172.

Gonzalez, A. (2003b): Tomorrow's EFL teacher Educators. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 86-104.

Kern, R. (2000). Literacy and Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lombana, C. (2002). Some issues for the teaching of writing. Profile, 3, 44-51.

Lopez, M. (2006). Exploring students' writing through hypertext design. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8,74-122.

Lopez, M. and Viáfara, J.(2007). Looking at cooperative learning through the eyes of public school teachers participating in a teacher development program. Profile, 8, 103-120.

Mahmoud, A. (2006). Translation and foreign language reading comprehension. English Teaching Forum, 44 (4).

Mendoza, E. (2005). Current State of the Teaching of Process Writing in EFL CLasses: An Observational Study in the Last Two Years in Secondary School. Profile Journal Issues In Teachers' Professional Development. , No. 6, p.23 - 36.

Merriam, S.(1988). Case study research in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publications.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional.Ley General de Educación, Bogotá, 1994.

Littlewood, W. (1984). Foreign and second language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language Learning Strategies. New York: Newbury House.

Raimes, A.(1983). Techniques in teaching writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Richards, J. and Rodgers, T. (1986). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ruiz, N. (2003). Kidwatching and the development of children as writers. Profile, 4, 51- 57.

Sanchez, A; Caicedo, M; Obando, G. (2000). Coping with grammar and writing. How, 40-43.

Silva, T. (1990). Second language composition instruction: developments, issues, and directions in ESL. In Kroll, B (Ed.), Second Language Writing. Cambridge: CUP.

Silva, T. (2000). Coping with grammar and writing. How, 28-39.

Smith, L. (1994): Biographical Method. In Denzin, N and Lincoln, Y (Eds) Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Viáfara, J. (2004). The Design of reflective tasks for the preparation of student teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 7, 53-74.

Viáfara, J. (2007). Student teachers' learning: the role of reflection in their development of pedagogical knowledge". Cuadernos de Linguística, 9, 225-242.

Zauscher, D.(2002). Alternative strategies for EFl writing instruction. How ,9, 49-52.

Zuñiga, G. and Macias, D. (2006). Refining students' academic writing skills in an undergraduate foreign language teaching program. Ikala, 1(17),311-336.

Zuñiga, G. (2003). A framework to build readers and writers in the second language classroom. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 158-175.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2008 vol:10 nro:1 pág:73-92

Research Articles

From pre-school to university: student-teachers’ characterize their EFL writing development

John Jairo Viáfara González

Language Department. Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC), Colombia. E-mail: jviafara@yahoo.com

Abstract

A historical review of approaches used to support students’ writing in English as a foreign or second language , as well as of Colombian teachers’ efforts to guide their pupils’ in this area becomes the starting point for this qualitative research. The study explores the biographical narratives of EFL pre-service teachers from Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC) to describe how they have developed their writing in English. The research reveals the methodological practices to which participants have been exposed from their early schooling until their university education in Colombian institutions, most of them located in Boyacá. Finally, the pedagogical implications seek to provide reflective points for the education of in-service and pre-service teachers at a time when higher standards in students’ foreign language learning are expected.

Key Words: EFL writing, teaching writing, instructional approaches for writing, pre-service teachers’ writing, biographical narratives

Resumen

Un recuento histórico de los enfoques utilizados para desarrollar la escritura en inglés como lengua extranjera o segunda y de las contribuciones de profesores colombianos en esta área, es el inicio de esta investigación cualitativa. El estudio explora las narraciones biográficas de futuros docentes de inglés en la Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia para reconstruir como ha sido su aprendizaje de habilidades escritúrales en esta lengua. La investigación revela las prácticas metodológicas a las cuales los participantes han sido expuestos desde su educación temprana, hasta sus estudios en universidades colombianas, la mayoría Boyacenses. Finalmente, las implicaciones pedagógicas apuntan hacia la reflexión en relación con la formación de profesores en ejercicio y practicantes, en un momento en el cual se tejen grandes expectativas alrededor del aprendizaje de las lenguas extranjeras.

Palabras Claves: Escritura en inglés, enseñanza de la escritura, enfoques metodológicos para la escritura, escritura de estudiantes practicantes, narraciones biográficas

Introduction

“Enabling solutions to contemporary problems to be sought in the past and throwing light on present and future trends”: two of the benefits that Hill and Kerber, (1967 as cited by Cohen and Manion,1995,pp.45) see in conducting historical research, clearly relate to the motivation behind this study. The current interest and commitment of many educational institutions at all levels in our country in fostering the learning of English, under the flag of what has been called “Colombia Bilingue” should imply a careful revision of what has happened with the teaching of foreign languages in our country from the past to now.

Documenting this pedagogical process emerges as a vital task since without a clear and informed understanding of how our students in schools and universities have experienced the development of specific skills in EFL along the years, it can not be expected that even the best plan to improve its teaching and learning can succeed.

Bearing the previous purpose in mind, three groups of student-teachers at UPTC (Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia) who attended their last English level in their licenciatura program were asked to participate in this research. The course which aims at preparing pre-service teachers in academic writing, not only seeks to address the technicalities of composition skills development, but also to foster their reflection upon the role that past pedagogical experiences might play in their decisions as current learners and future teachers.

By means of an exploratory writing exercise and a survey, these preservice teachers provided the substance to investigate what their biographical narratives informed about their past practices in learning to write in English. The biographical records which have been analyzed to answer this question involve pre-school and primary, secondary as well as university education prior to the target course. This information has been organized into several emerging topics to characterize participants’ writing development.

The next sections of the article will discuss the theoretical pillars around the development of writing skills in English as a foreign or second language. Moreover, a rich perspective of what has been reported by researchers in Colombia will be added. Then, the research methodology and process rooted on historical inquiry will be specified. Finally, the findings and conclusions from data analysis will be revealed.

The Practice of Writing Skills in ESL and EFL Settings: Where do we come from? Where do we stand?

A contemporary approach to the development of writing skills in the learning of English as a second or foreign language might be linked to current pedagogical tendencies based on socio-critical literacy. Kern (2000,p. 172-173) regards writing as a means to foster mental processes and learning which might increase our comprehension and connection with others and the reality around us. Likewise, our possibility to play with language forms as we write, can lead us to a constant redefinition of meaning. In this regards, communication and imagination can be expanded when we perceive writing, not just as a possibility to accomplish language functions, but also as a vehicle to understand, interact and transform our world.

Along the previous perspective, other approaches for the teaching of writing in ESL and EFL settings have co-existed. To begin with, a first approach can be seen in connection with the level of independence and creativity that learners can have. Placed at one extreme of that continuum, we can find controlled or guided composition (Silva,1990); a method that was popular by the 1940`s. Students under this kind of instruction were not expected to write to develop this skill in itself, they did it to support their practice of their speaking. Thus, pupils copied once and again pre-established language patterns to mechanize grammatical and syntactical forms. Composition elements such as considering the audience, the intention, purpose and quality of ideas were not taken into consideration.

A more dynamic version of this perspective is the controlled-to-free approach (Byrne,1979; Raimes,1983), in which students can write freely when they have become highly accurate and proficient. Finally, the freewriting technique advocates for learners’ primarily development of fluency over accuracy.

Another point of departure for approaches has been the focus on units of composition such as the paragraph (Byrne,1979; Raimes, 1983; Silva,1990). The Current-traditional rhetoric or paragraph pattern approach guides students, so based on models that they analyze and imitate, they can produce topic and supporting sentences to construct coherent paragraphs. Similarly, considering paragraph elements such as an introduction, a body and a conclusion can lead pupils to build even essays under the same patterns. Students’ free expression is gradually allowed.

More recently, methodologies have imitated real life writers’ composition activities. Process writing and communicative language teaching provide opportunities for students to have more control in their expression of ideas (Silva,1990; Byrne,1979; Raimes, 1983). Teachers become facilitators of the process and along with classmates, educators act as actual readers of learners’ texts. A Process writing approach implies one’s involvement in activities to generate and plan ideas to compose a text. Then through continuous drafting, as well as revision the subsequent versions are shaped into pieces which can become higher in quality each time. A comfortable, non-threatening and supportive environment to write is considered essential in this process as it is in the communicative approach.

Byrne (1979) highlights some other principles that the teaching of writing in EFL has adopted from communicative language teaching. To begin with, students need to be in contact with real-life writing, as well as with opportunities to interact through the texts that they produce. Thus, learners can understand the strategies that they can effectively use to communicate with their readers. Activities center on students’ needs and interests along with those that involve the simultaneous practice of the other language skills.

At a university level, when English is studied for specific purposes, academic writing has become popular since students are expected to handle particular conventions dictated by academic standards in their disciplines of interest (Silva, 1990). Consequently, students might be involved, for instance, in writing a research report guided by a series of preparatory tasks.

Since each of the previous approaches centers in different aspects of the development of writing, they can be regarded as complementary methodologies. Nowadays approaches to support students’ composition can be placed at a post method condition since teachers do not look for the ideal method anymore (Silva, 2000, p.34); they are informed by theory and supported by materials, students’ needs and their perceptions to search for a method.

The Teaching of Writing Skills in English as a Foreign Language in Colombia

The following review originates from what Colombian teachers have published in relation to their efforts to explore and support their pupils’ EFL writing in the last decade. Lombana (2002), Clavijo and Torres (2004) and Ruiz (2003) have studied elementary school students’ development of writing skills in EFL. They argue that the relation between Spanish and English enriches literacy in very young learners. Furthermore, Clavijo and Ruiz remark the importance of strengthening the connections between reading and writing. Moreover, Clavijo calls teachers’ attention in addressing writing practices in terms of their reallife objectives. Ruiz also found that collaborative work and understanding how children build their image as writers are issues that need to be taken into consideration.

Writing skills at a secondary level of education in our country has been an issue of reflection for several EFL teachers in private and public institutions. Zauscher (2002), Sanchez and et.al (2000) and Lombana (2002) suggest the use of methodologies which support students’ expression and creativity during their composition process. A communicative approach can motivate students while they develop knowledge in essential formal and communicative aspects.

Other teacher-researchers have been interested in process writing. Ariza (2005) and Aldana (2005) underline, as some of the advantages of this approach, that their students increased their motivation towards writing. Additionally, pupils obtained a higher level of proficiency in their composition skills, (Aldana, p.52). Nevertheless, Ariza identified as a conflictive issue that writing was hard for her pupils since they were not often involved in the practice of this skill; thus, many times they expected to develop activities in which they have to follow patterns, as they usually did it before. Aldana expresses that leading students to gain awareness of relevant aspects in real-life written communication became a challenge; her pupils generally asked for feedback to solve grammatical or spelling problems without showing any concern for the overall meaning of their ideas. Finally, Medoza points, through his observation of six high schools settings, that most of the guidance students received when involved in process writing was in Spanish.

University professors in Colombia have incorporated innovative perspectives to encourage learners’ writing in English. By combining collaborative and process writing with hypertext design to instruct her pupils, Lopez (2006) found that students revealed higher motivation and skills for deeper expression of ideas. The influence of new technologies in students’ development of writing skills in English has also been underlined by (Zúñiga, 2003,p.168).

University professors have worked in fostering academic writing in their students. Zúñiga and Macias (2006) explored EFL undergraduate students’ writing focused on process, critical and academic approaches. They support the need for experiences rooted in communicative language teaching principles; they conclude that a student-centered environment increases students’ awareness of their process which can reduce difficulties in paragraphs and ideas organization.

Investigating UPTC Pre-Service Students’ Writing History

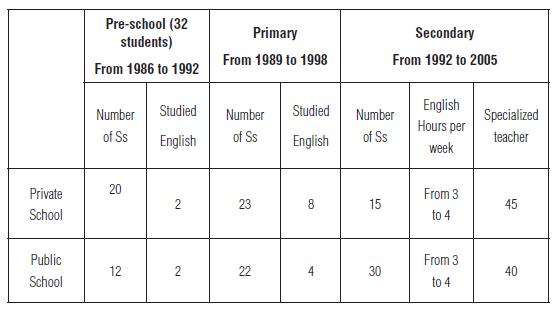

This biographical inquiry included 45 EFL pre-service teachers in the Modern Languages program at UPTC in Tunja. They were 35 women and 10 men. Their ages ranged from 20 to 26 years old at the time they participated in the study. Their places of origin were rural areas of Boyacá (10), urban areas of Boyacá (25), Bogotá (4), rural areas of Santander (2), and urban areas of Santander (4). The following chart shows data concerning their school history from kindergarten to secondary education.

Participants’ entrance to the university took place between 2002 and 2005. They were attending the course called Proyecto Comunicativo VII when they provided their narratives. Their English level can be placed between preintermediate and intermediate. These forty five student teachers belonged to three different cohorts from 2006 to 2008. The distribution of participants per semester is as follows: 10 took the course during the second semester of 2006, 11 attended during the first semester of 2007 and 24 were part of this class in the first semester of 2008. They signed consent forms to authorize the use of their autobiographical records in this study.

Life Writing: a Research Methodology

Several fields, within what Smith (1994) calls life writing, can be referenced to describe the kind of methodology that was used to conduct this qualitative study. Cohen and Manion (1995) for instance, mentions retrospective life history, “a reconstruction of past events from the present feelings and interpretations of the individual concerned” (p.60). In regards to this research, the exploration of student teachers’ writing in English was based on their narratives to look back at what they had experienced along their school years. Autobiography can also be closely related to life histories and its use has been considered of special relevance since it “gives voice to people long denied access”, (Smith,1995,p.288). In the specific case of teachers, Clavijo (1998 and 2000) regards autobiographical accounts as meaningful records to explore teachers’ lives in connection with their knowledge, work and professional development.

The data collected for this study came from 45 written autobiographical accounts produced by the same number of participants. During one of the fist sessions in the course Proyecto Comunicativo VII, they were asked to write about their process to write in English from pre-school to their current university semester. Participants produced an average of three pages. They were provided some ideas to focus their writing and start their narratives: a critical experience, an important teacher, the kind of activities developed, whether they liked the tasks or not, among others. They had several additional opportunities to work more in their writing to shape it as they wished. They also exchanged their accounts with their partners. I collected the narratives and I provided comments in regards to the content at the beginning; I provided answers acting as a reader would do. Furthermore, I provided feedback about formal aspects at the end.

Additionally to the previous instrument, participants were also asked to fill in a questionnaire (see annex 1). The questionnaire helped to corroborate what pre-service teachers informed by means of their biographical accounts. Plummer (1993, as cited in Cohen and Manion, 1994, p.62) states that “a comparison may be made with similar written sources as a way to identify points of major divergence or similarity” to assure validity in this kind of approach . In the questionnaire, participants’ answers revealed pieces of their writing history as well. Likewise, the fact that three different groups of student teachers at three different semesters provided data gives weight to the findings (Merriam, 1988).

The analysis of data was based on thematic edition (Cohen and Manion,1994; Smith,1995). After information had been gathered, there was a selection of issues which directly related to the question that motivated this study. Common topics were organized under headings which generalized them. Special care was taken to keep the words of participants intact as they were analyzed.

Pre-school and Primary Education: Opening the Gates to English Learning While the Familiarization with Spanish is in Progress

Participants’ narratives about their writing in English did not include much information about their pre-school or primary grades. Most of them expressed they did not have much to say because English learning started, for almost all of them, in secondary school. As we can see in chart 1, only 4 pre-service teachers studied English at Kindergarten and 12 at primary education. Though this might seem surprising, it is relevant to keep in mind that during the years participants were at Kindergarten (1986 to 1992) and primary school (1989 to 1998) the Education Act (115) Ley 115, which established the learning of English in primary, had been recently approved. However, even in the years to come after that law was passed, as Cardenas (2001,p.5) expresses:“ In many institutions and in several regions of the country, the teaching of a foreign language at the elementary level had not started”. Teachers seemed to struggle to cope with the new demands as Estella’s account, from a survey, evidences: “I think the teacher did not have a methodology because she did not know how to speak in English”.

The most common teaching pattern in writing at this stage was to involve students in learning vocabulary. They were guided to memorize words, their pronunciation and spelling. A study conducted by Cadavid and et.al (2004) referred to the limited condition of the English that is being taught in elementary schools in Colombia. Daniel expresses in relation to his pre-school education:

“When I began my process of acquiring a second language I was a child. The first words I wrote were the names of fruits. Teacher Lucia had a special methodology, we had to paint fruits, then we had to pass in front of the classroom, pronounce them and say the color. It was difficult for me”.

Another participant, Maria, characterizes her experiences in primary commenting that

“My writing process was mechanical; all the time I repeated what the teacher wrote in my notebook. Sometimes I didn’t understand but I tried to imitate the words…maybe they thought that we only needed to learn letters, for this reason I created this concept about writing”

Several spontaneous remarks of student teachers referred to their learning of Spanish along the first school years. They basically mentioned the kinds of beliefs they held about writing in their native language at those ages. For instance, Luisa expressed that “I thought that writing well was to make beautiful letters and to complete pages”. Similarly as they hypothesize about how certain words are written in Spanish combining different symbols, children also combine English, Spanish and pictures to start writing their first pieces in the foreign language. This seems to give weight to Lombana (2002); Clavijo and Torres (2004) Ruiz’ (2003) claims about the existence of similarities in children’s writing development process in their 1st and 2nd language.

Experiencing an EFL Secondary School Curriculum: Writing Emerges as a Complex Task for Learners

From 1992 to 2004, participants attended secondary education. The instruction they had to develop their writing varied from one kind of institution to another.

“The first one was a private school and in that school English teaching was focused on communicative aspects more than teaching grammar”. The second school was a public school. In that school teacher asked students to translate some texts and memorize those texts. We wrote sentences about grammar points” (Erminda)

Various curricular elements affected how participants viewed their writing process. Among them, as it will be evidenced in the following lines, their teachers’ role seemed to be at the core of what they included in their histories.

• The Roles of Teachers in Pre-Service Teachers’ Writing

“I needed help, I asked my teacher to explain the topics. She taught me the most important topics that I needed to learn and she gave me strategies to work on my abilities”. A supportive teacher was the expectation that many participants, as Erminda had. However, other pre-service teachers’ autobiographies describe educators who seemed not to be always committed with their pupils’ learning or who were apparently closed-minded about the teaching of English.

“When I came at high school the teacher told me that the English language was very difficult because it could be learnt just by people who traveled to United States I believed that the English class was like a horrible trip to other countries where the teachers were like ghosts. They hurt somebody’s feeling into the classroom” (Jimena)

Several reasons could be connected to participants’ educators’ limiting attitudes as the ones described above. Particularly, the role given to the teaching of English in their secondary education institutions was remarked “It was not an important subject for my teachers. The main subjects were Mathematics, Science and Biology”, Ivan explained. Additionally, the preparation of teachers to become guides in this process was mentioned. “I studied in a military school and my teacher was a policewoman. She had to give us class without knowledge about the subject…she was originally a Math teacher” (Estella).

• The methodology used to teach learners to write in English

The most prominent feature in teachers’ methodology was the use of translation. “I translated word by word from one language to another but it was not right to improve my level of English. I could not express myself clearly in the foreign language” (Hilda). Literal translation took place from English into Spanish or from Spanish into English. For a good number of pre-service teachers, it was considered a time consuming practice that made writing difficult since they frequently wrote what they wanted to say, first in Spanish, and then they translated it into English. From what other researchers report this seems to continue being a common practice for the teaching of writing in secondary schools in Colombia (Mendoza, 2005).

The second characteristic involves grammatical training as the core of writing practices. Topics were often the same: “present simple and verb to be”. “I remember that classes were based on learning to understand verbal tenses or to write 100 verbs in present and past…those classes took much time and the advances were slow” (Carlos). Ariza (2005) and Aldana (2005) underline the difficulties they had to involve their pupils in process writing since these students were used to work mostly with grammatical activities.

Grammar was practiced out of a real life context by means of filling the gap exercises which involved repetition and memorization. Copying literally from the board and from textbooks supported mechanical practices. “I had to memorize, writing again and again, a long list of words, verbs, expressions and I had to make sentences of them. That process was not easy because I forgot the words easily” (Sonia). Zauscher (2002) claims that the use of mechanical drills is a common practice in Colombian EFL contexts to instruct students in writing. Surprisingly and despite of their constant work in grammar and vocabulary, the group of pre-service teachers felt they had not been prepared in this area. “During school the writing process was difficult for me because I didn’t understand the grammar structure” (Lida)

Textbooks seemed to be one of the most common materials used by teachers to support writing. However, a few participants mentioned other resources such as audio and video recorders along with computer programs. From the ones who could count with more advanced resources, a good number felt disappointed since as Daniel narrates:

“In the school there was a program called discoveries and we had the opportunity to go there two hours per month that was not wonderful as I thought in that moment because we only wrote copied or transcribed from the computers to our notebook about grammar and the worst of all was that was a mark.”

Pre-service teachers also included relevant comments about the role of other language skills in their learning to write. “I had not opportunities to a real exposure to English. We did not have interaction with other students. Teachers never spoke English inside the classroom although she was the only contact we had with English” (Ivan). Mendoza (2005) found in an exploration of Colombian teachers’ writing practices that Spanish was used to provide explanations, feedback and oral answers to exercises; in general speaking in English was not a characteristic of classes.

Apparently, the kind of practices described above, turned this literacy activity into a complex process in which fears, doubts and boredom appeared. “Writing has been one of the hardest tasks during my English learning because of what it requires” (Imelda). Another of those requirements was to cope with thinking processes: “When I tried to write my first paper years ago, I didn’t know how to manage information in my brain. I thought that writing was a terrible punishment” (Luisa). Lombana (2002) points that threatening conditions seem to have surrounded the development of writing in many students and teachers.

Turning to what pre-service teachers consider enjoyable activities, Yolanda’s remarked in a survey: “At 11 and 10th grades our teacher tried to use a communicative approach. She tried to encourage us to use the language in real situations”. As a contrast Camilo refers to “The few sentences we could write on the notebook were like ´John goes to the park´. They had no sense and no connection with real life. I felt the English language was thousands of kilometers away from me”.

Similarly, they showed high acceptance for writing based on a stagesequenced process which provided them the autonomy to make decisions about their learning:

“We chose a free topic to write a story, we worked in pairs, we received tutorial classes and finally she gave us feedback. The results were good, we had to follow a writing process where we learned new vocabulary, new expressions, and we had to do many drafts in order to organize ideas as an interesting way for a reader” (Diego)

Providing feedback, focusing in writing for a reader and giving students’ the chance to work on their own interests have also been remarked in investigations by Aldana(2005) and Ariza (2005) as aspects that their students considered motivating for the writing process.

• Evaluation Concerns

Feedback as a key element in the assessment of writing encouraged participants when it took place within a structured process to support their composition skills. However, other events provided different shades to the characteristics of evaluation: “The teacher used a military teaching style. When we finished the class she asked general questions and vocabulary. If we did not answer she organized us in lines and we had to run around the basketball field” (Stella). Mistakes were emphasized and not tolerated in many cases which resulted in feelings as the ones Carlos described: “one of the impediments that I have to face when I try to write is my fear to be criticized ...and fear to be rejected”. Teachers’ excessive emphasis on students’ mistakes has emerged also as a reflective issue in studies. Ariza (2005) reveals that it was difficult for her to stop correcting students all the time as she tried to innovate in her approach to teach writing.

External evaluation from the ICFES (Instituto Colombiano para el Fomento de la Educación Superior) national Exam seemed to be important criteria for student teachers to look at their achievements, demand more from themselves and increase their skills. Additionally, they narrated how the teaching of English varied as the time for the exam approached. Sonia wrote “But the situation changed when we had to present the ICFES. My English teacher started to teach us new vocabulary and sentences structures. The materials were posters, videos…She tried to be better at her teaching”.

Writing in English at a University Stage: Reshaping Writing Experiences

Approximately 50 percent of pre-service teachers expressed that writing was an experience they started when they began their university studies. This involves not only English but also Spanish. Apparently several activities and subjects have fostered participants’ development of writing skills along with their understanding of the purposes that this practice can have in their personal and professional growth. The next lines expand the previous views.

• New Vs old dimensions in writing

Keeping the use of their former learning habits emerged as a tendency in the participants. “In 1st semester I used to write word by word and translate literally all the words”(Lida). Though these strategies were spontaneously conducted by some of them, in other cases as Yalile’s: “I had many problems due to the fact that in the first Communicative Project teachers gave us a long checklist with words, sentences, questions and answers that we had to memorize”. Thinking in Spanish when they write in English, their exposure to repetitive activities and materials, as well as their obligation to write about topics which are not of their interest become reminiscences of past experiences they faced in primary and specially secondary school:

“We have professors who consider language is just a rational system which is untied to the construction to the subject personality and their external experiences outside the classroom. They thank that writing must be limited to the dogmatic obedience of grammatical rules” (Rene).

Autobiographical records also included the new perspectives student teachers have adopted to use the written word. “Writing is more that letters put on a paper…that each text when is honest could be a mirror of each person and a media to have a conversation with the other” (Gina).They have found opportunities to express in regards to their personal issues, to share with others, to reflect upon culture as well as society and to be creative as well as to gain recognition. “In a class I started to have a wide vision of black people, homosexual people, and native people among others. It was the impulse which let me know the writing process. From that moment, I have tried to explore what writing means and I have discovered it” (Denis). At this stage, another door seems to open for pre-service teachers: “I am very shy to speak in public or in a big group. Specifically in English because I feel fear of being wrong or making mistakes, therefore I prefer to express my thoughts in writing” (Diana).

Literature courses and investigation were specially underlined by preservice teachers as enriching activities: “The development of research projects encouraged me to take my writing process as a challenge”. Likewise, they highlighted activities such as keeping journals and contextualized writing.

• Writing in English or in Spanish to Feel Comfortable in Communicating their Ideas

Participants’ views revealed a contrast about how they perceived their communicative possibilities in Spanish or English:

“When I was a child I could express my ideas, my dreams my expectations very good through Spanish because it was my maternal language but I began to write in English and My writing changed, it has been a challenge for me because I have to study very much to understand my ideas and transmit them in a paper”(Ernesto).

On the contrary, Gina expressed that :

“Then for me English is an ally, an accomplice, where I could feel free, where I can find the space to express myself. I don’t know why but my words in Spanish are predetermined for that reason I don’t feel them as own- in English I begin to search the words in myself.”

Other participants expressed that “Spanish have get me closer to writing in English because both complement” (Maria). Thus, they do not regard one of the two tongues as being really distant from the other in their overall skill development.

• Skill development in English: A Motivation to Enroll in the Modern Languages Program

The experiences that participants lived in regards to their English learning in secondary schools became for some of them powerful reasons to choose the Modern Languages program. “I have to thank my teacher for those opportunities to improve my writing. My knowledge from my school helped me to choose this program and become the teacher that I want to be” (Yesenia). Nevertheless, it was not only from inspiring events as the one described by the previous participant that studying languages was chosen as an option.“I decided to be a teacher to finish this traditional education paying attention to the students’ needs, learners differences etc” (Daniel).

Conclusions and Implications

By claiming that their writing skills development started with their entrance to the university, participants suggested that most of them did not really perceive a substantial advancement in the mastery of the skill along elementary or secondary education. A few number of pre-service teachers reported what they considered to be enriching opportunities to learn how to write.

The methodologies pre-service teachers’ educators used to instruct them have been similar along their primary, secondary school and in some cases, university studies. Most of them match the controlled or guided composition, the Grammar Translation and the audio-lingual Method which date back from the 40’s and 60’s. The overuse of those methods has caused a long list of hardships in their learning process. In this regards, Richards and Rodgers (1986,p. 5) mention that :

“The foreign language learning meant a tedious experience of memorizing endless list of unusable grammar rules and vocabulary and attempting to produce perfect translations...it often creates confusion and makes few demands on teachers”

The previous considerations should not imply to deny the importance that taking notes, handling grammar, structuring paragraphs, memorizing pieces of language (Lombana, 2002) and acquiring vocabulary have as essential aspects in mastering writing. Nevertheless, the need to adopt more recent trends, based on the communicative nature of language for the development of EFL writing skills, can not be a second option but a priority as remarked by a good number of authors (Raimes, 1983; Byrne,1979; Sanchez and et.al, 2000; Zauscher,2002; Kern 2000).

Translating into Spanish emerged as noticeable feature in the methodology to support participants’ writing skills. This practice requires serious considerations from EFL educators. Though the role of the first language in the teaching and learning of the second one has lately been associated with beneficial aspects, there are also potential problems that can emerge from its excessive use. Issues such as the use of authentic materials, its centering in the leaner, its promotion of autonomy and in some cases its contribution to understanding the structure as well as functioning of L2 have been considered positive aspects (Mahmoud, 2006).

Unfortunately, when translation becomes the rule to instruct students in writing, they might become dependent of it to function in the second language. Visiting schools as student teachers’ counselor, I have noticed how very often their pupils insist on hearing the translation of utterances even though they are clear about what they have been told. Currently systematic translation causes most of the problems participants have to produce coherent texts during the Communicative VII course. With no doubt, if learners use translation as a the required steps to communicate in L2, and not as one of many other language learning strategies (Oxford, 1990), their chances to make of transfer (Littlewood,1984) a source for errors in the English they produce become higher.

The previous considerations reveal an urgent need to provide teachers with the opportunity to participate in Development Programs (TDP) that not only help them increase their proficiency in the language, but also support their use of innovative methodologies (Gonzalez, 2003a; 2003b). Bearing in mind that adopting new approaches in ELT often becomes a challenge for school teachers, TDP can support educators’ methodological changes by means of continuous coaching (Lopez and Viáfara, 2007). Likewise, including a research module in TDPs can favor teachers’ reflective attitudes to integrate ELT methodologies coherently into real settings. Additionally, it might foster educators own development of writing skills (Cárdenas, 2003).

In order to achieve this, the experience that Colombian teacherresearchers, as the ones cited in this article, have gathered during the last decade can become an important contribution. Their knowledge of our national context is absolutely pertinent to propose teacher education programs relevant for our students.

Participants’ university experiences support the impact that wider perspectives, based on socio-critical approaches, have had in their learning: “through writing I have discovered other different and very interesting ways of thinking and they have helped me to understand and construct my own point of view in the presence of life” (Gina). We should seriously consider the introduction of these kinds of approaches in earlier stages of our pupils’ education.

Several of the writing practices identified along this study might have conditioned participants to repeat the very same models they were exposed to along their learning. During my work in the teaching practicum in the target context, I have witnessed that a good number of pre-service teachers start their experience involving their pupils in no contextualized learning, grammar-based lessons without a communicative goal and the use translation as a routine. The use of tools such as teaching journals, conferences, observation notes and portfolios can trigger student teachers’ reflective practice (Viáfara, 2005 and 2007), so that they are able to identify how previous language practices might have influenced their learning and might shape their work as future teachers. Then, prospective teachers could take specific actions to improve not only in their writing skills, but also their teaching.

References

Ariza, A. (2005).The process-writing approach: an alternative to guide the students’ compositions. Profile, 6, 37-46.

Aldana, A. (2005). The process of writing a text by using cooperative learning. Profile, Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 6, 47-57.

Byrne, D. (1979). Teaching Writing Skills. London: Longman.

Cadavid, M; Mcnulty, M; Quinchía, O. (2004). Elementary English language instruction: Colombian teachers’ classroom practices. Profile, 5, 37-55.

Cárdenas, M. (2003). Teacher researchers as writers: a way to sharing findings. Colombian Applied linguistics Journal, 5, 49-64.

Cárdenas, R.(2001). Teaching English in primary: are we ready for it? HOW, 8, 1-9.

Clavijo, A. (1998). Teachers’ life histories: An important input in the formation of teachers’s beliefs. A case of a bilingual teacher. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 1(1), pp. 3-20.

Clavijo, A. (2000). Historia y vida: reflexión y praxis del maestro colombiano acerca de la lectura y la escritura. Bogotá: Plaza y Janes.

Clavijo, A. and Torres, E. (2004). Relación entre la adquisición de la lengua materna y el aprendizaje de una segunda lengua. En Clavijo, A y Torres, E (Comp) Aprendiendo a enseñar ingles a niños. Bogota: Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas.

Cohen, L and Manion, L.(1995). Research Methods in Education. London: Routledge.

Gonzalez, A. (2003a). Who is educating EFL Teachers: a qualitative study of in-service in Colombia. Ikala, 8(14),153-172.

Gonzalez, A.(2003b): Tomorrow’s EFL teacher Educators. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 86-104.

Kern, R. (2000). Literacy and Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lombana, C. (2002). Some issues for the teaching of writing. Profile, 3, 44-51.

Lopez, M. (2006). Exploring students’ writing through hypertext design. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8,74-122.

Lopez, M. and Viáfara, J.(2007). Looking at cooperative learning through the eyes of public school teachers participating in a teacher development program. Profile, 8, 103-120.

Mahmoud, A. (2006). Translation and foreign language reading comprehension. English Teaching Forum, 44 (4).

Mendoza, E. (2005). Current State of the Teaching of Process Writing in EFL CLasses: An Observational Study in the Last Two Years in Secondary School. Profile Journal Issues In Teachers’ Professional Development. , No. 6, p.23 - 36.

Merriam, S.(1988). Case study research in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publications.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional.Ley General de Educación, Bogotá, 1994.

Littlewood, W. (1984). Foreign and second language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language Learning Strategies. New York: Newbury House.

Raimes, A.(1983). Techniques in teaching writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Richards, J. and Rodgers, T. (1986). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ruiz, N. (2003). Kidwatching and the development of children as writers. Profile, 4, 51- 57.

Sanchez, A; Caicedo, M; Obando, G. (2000). Coping with grammar and writing. How, Silva, T. (1990). Second language composition instruction: developments, issues, and directions in ESL. In Kroll, B (Ed.), Second Language Writing. Cambridge: CUP.

Sanchez, A; Caicedo, M; Obando, G.(2000). Coping with grammar and writing. How, 28-39.

Smith, L. (1994): Biographical Method. In Denzin, N and Lincoln, Y (Eds) Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Viáfara, J. (2004). The Design of reflective tasks for the preparation of student teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 7, 53-74.

Viáfara, J. (2007). Student teachers’ learning: the role of reflection in their development of pedagogical knowledge”. Cuadernos de Linguística, 9, 225-242.

Zauscher, D.(2002). Alternative strategies for EFl writing instruction. How ,9, 49-52.

Zuñiga, G. and Macias, D. (2006). Refining students’ academic writing skills in an undergraduate foreign language teaching program. Ikala, 1(17),311-336.

Zuñiga, G. (2003). A framework to build readers and writers in the second language classroom. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 158-175.

ANNEX 1

SURVEY TO EXPLORE PARTICIPANTS’ EFL WRITING EXPERIENCES

Dear Student Teachers the purpose of the following questionnaire is to collect information about your writing process experiences along your school years. Your cooperation and honesty would be an important contribution to improve these experiences and therefore, what we can do for many other student teachers in the future. Please, be as detailed as possible in your answers. Thanks.

- When did you start writing in English?

- What kind of texts did you write at the beginning of your English learning?

- How was the methodology your teachers used to teach you to write in English in pre-school or primary grades?

- How did your learning to write in English took place during your secondary school?

- Write about situations that have contributed to the development of your writing skills along your university education.

- Write about situations that have limited your development of writing skills along your university education.

- Do you perceive that previous experiences in your schooling have affected in your writing? If so, How?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

He holds a B.Ed in Education (English) from Universidad Nacional de Colombia. M.A in Applied Linguistics to the Teaching of English from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. He has worked in several Universities in Colombia. Currently he is an assistant professor at Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC) where he has worked at the undergraduate and Master’s Program.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.