DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/21450706.20479Publicado:

2023-03-02Número:

Vol. 18 Núm. 34 (2023): Julio-diciembre de 2023Sección:

Sección CentralContexto institucional de las artes en Ucrania occidental

Lower Institutional Context of Western Ukraine

Contexto Institucional das Artes na Ucrânia Ocidental

Palabras clave:

Galerías autoorganizadas, publicación de libros, contexto institucional informal, arte contemporáneo, Ucrania occidental (es).Palabras clave:

Self-organized galleries, book publishing, grassroots institutional context, contemporary art, Western Ukraine (en).Referencias

Andryczyk, M. (2018). Intellectual as a hero of Ukrainian prose of the 90s of the twentieth century. Lviv: “Pyramida”.

Apolitychnyy prostir (2016). https://mitec.ua/apolitichno-prostranstvo/

Babii, N. (2019). “Impresa” as a catalizer of art-cultural processes in Ukraine of the 90-s years of the 20thcentury. Ukrainian culture: the past, modern ways of development, 31, 187-193.

Babii, N., Hubal, B., Dundiak, I., Chuyko, O., Chmelyk, I., Maksymliuk, I. (2021). Performance: transformation of the socio-cultural landscape. AD ALTA: Journal of interdisciplinary research, 1(XVII), 129-133.

Domashchuk, H. (2017). Activities of art galleries in Lviv in the late 80’s - early 90’s of the twentieth century. Culture of Ukraine, 55, 299.

Hanzha, L. (1999, August 11). Lyrics instead of propaganda posters. Day, 146.

Karas, G. (2001). Ivano-Frankivsk: cultural and artistic chronicle of Independence. Ivano-Frankivsk: Nova Zorya. Manifesto. Impreza. Provintsiynyy dodatok Nº2 (1991). Exhibition catalog.

Melʹnyk V. (2002-2003). Repozytsiya. Kinetsʹ Kintsem. P. 64

Miziano, V. (1999). Kul’turnyye protivorechiya tusovki. artmagazine, Nº.25. http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/76/article/1658

Myroslav Yaremak: “Vykhovaty Frankenshtayna” (1998). Day https://tinyurl.com/ycxva5h5

Osborne, P. (2013). Art Space, Anywhere Or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art. London and New York: Verso, pp. 133–174.

Petrova. O. (2004). Your way / Art reflections. Kyiv: Academy.

Podaruy my pysanochku. (2001). Ivano-Frankivsʹk: Kamenyar – Gerdan Grafika.

Pospish, T. (1999). 90s: freedom from art. Artmagazine, 25.http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/76/article/1660

P. S. abo “Nʹyu-Vasyukivsʹkyy proekt” khudozhnyka Myroslava Yaremaka. Zakhidnyy kur”yer, 1994, Nº.19 (352), p. 10.Scientific Conference on Contemporary Art “Impreza” (1995). Collection of speeches and abstracts.

Shumylovych, B., & Sokolov, Y.U. (n.d.). Halereyi “Detsyma”, “Chervoni rury”. https://tinyurl.com/2jjdp2hb

Slipchenko, K. (1996). Art projects “Ye”. Terra Incognita, 5, 30.

Zasiedko, A. (n.d.). White cube. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Contexto institucional de las artes en Ucrania occidental

Institutional Context of the Arts in Western Ukraine

Contexte institutionnel des Arts en Ukraine occidentale

Contexto Institucional das Artes na Ucrânia Ocidental

Contexto institucional de las artes en Ucrania occidental

Calle14: revista de investigación en el campo del arte, vol. 18, núm. 34, pp. 234-249, 2023

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

Recepción: 24 Junio 2022

Aprobación: 27 Agosto 2022

Resumen:

El estudio examina las estrategias y prácticas utilizadas por los artistas en el oeste de Ucrania para promover y representar el arte contemporáneo a finales del siglo XX y principios del XXI. Nuestra atención se centra en el papel de las instituciones culturales y artísticas en la configuración del valor del arte durante una época de crisis y cambio en la jerarquía de estas instituciones. El estudio utiliza una variedad de fuentes, incluyendo catálogos, folletos de galerías, archivos privados y productos de librería actuales, así como entrevistas con participantes en estos procesos. Argumentamos que el surgimiento del arte contemporáneo en Ucrania occidental está estrechamente relacionado con la formación de un capital cultural a fines del siglo XX gracias a la participación de capital social, político y burocrático. El estudio también analiza las formas en que los artistas y poetas han pasado de la «esfera del arte» ala «esfera de la cultura» al convertirse en «estrellas» y crear sus propias instituciones, como curadurías independientes, entornos artísticos para el diálogo cultural, galerías privadas, editoriales y distintos formatos mediáticos.

Palabras clave: Galerías autoorganizadas, publicación de libros, contexto institucional informal, arte contemporáneo, Ucrania occidental.

Abstract: This study examines the strategies and practices used by artists in Western Ukraine to promote and represent contemporary art during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The focus is on the role of cultural and artistic institutions in shaping the value of art during a time of crisis and change in the hierarchy of these institutions. It uses a variety of sources, including catalogs, gallery brochures, private archives, and current bookstore products, as well as interviewswith participants in these processes. We argue that the rise of contemporary art in Western Ukraine is closely linked to the formation of cultural capital in the late 20th century, through the participation of social, political, and bureaucratic capital. The study also looks at the ways in which artists and poets have transitioned from the «sphere of art» to the «sphere of culture» by becoming «stars» and creating their own institutions, such as independent curatorships, artistic environments for cultural dialogue, private galleries, publishing houses, and media formats.

Keywords: Self-organized galleries, book publishing, grassroots institutional context, contemporary art, Western Ukraine.

Résumé: L’étude examine les stratégies et les pratiques utilisées par les artistes de l’ouest de l’Ukraine pour promouvoir et représenter l’art contemporain à la fin du XXe et au début du XXIe siècle. L’accent est mis sur le rôle des institutions culturelles et artistiques dans la formation de la valeur de l’art en temps de crise et de changement dans la hiérarchie de ces institutions. L’étude utilise une variété de sources, y compris des catalogues, des brochures de galeries, des archives privées et des produits actuels de librairies, ainsi que des entretiens avec des participants àces processus. Nous soutenons que l’essor de l’art contemporain en Ukraine occidentale est étroitement lié à la formation du capital culturel à la fin du XXe siècle, à travers la participation du capital social, politique et bureaucratique. L’étude s’intéresse également à la manière dontles artistes et les poètes sont passés de la « sphère de l’art » à la « sphère de la culture » en devenant des « stars » et en créant leurs propres institutions, telles que des commissariats indépendants, des environnements artistiques pour le dialogue culturel, galeries privées, maisons d’édition et formats médiatiques.

Mots clés: Galeries autoorganisées, édition de livres, contexte institutionnel informel, art contemporain, Ukraine occidentale.

Resumo:

O estudo examina as estratégias e práticas usadas por artistas na Ucrânia Ocidental para promover e representar a arte contemporânea durante o final do século XX e início do século XXI. O foco está no papel das instituições culturais e artísticas na formação do valor da arte durante um período de crise e mudança na hierarquia dessas instituições. O estudo utiliza uma variedade de fontes, incluindo catálogos, brochuras de galerias, arquivos privados e produtos atuais de livrarias, bem como entrevistas com participantes desses processos. Ele argumenta que a ascensão da arte contemporânea na Ucrânia Ocidental está intimamente ligada à formação do capital cultural no final do século 20, por meio da participação do capital social, políticoe burocrático. O estudo também analisa as formas pelas quais artistas e poetas passaram da “esfera da arte” para a “esfera da cultura”, tornando-se “estrelas” e criando suas próprias instituições, como curadorias independentes, ambientes artísticos para o diálogo cultural, galerias privadas, editoras e formatos de mídia.

Palavras-chave: Galerias auto-organizadas, publicação de livros, contexto institucional informal, arte contemporânea, Ucrânia ocidental.

Introduction

The economic recession of the 2000s minimizes the share of private collecting, and at the same time the centralized printing activity. The publication of cata- logues, albums, monographs, booklets is absent or passes into the self-published stage or to the programs of new publishing houses. Active hangouts were the first to destroy the corporate framework, taking over the role of culturologists and publishers. They were also gallery owners, while gallery owners became politicians, theorists, image makers, and so on.

A keen sense of the acceleration of the historical rhythm at the turn of the millennium led to numerous discussions on the key problems of historical knowl- edge, including all aspects of the presence of the past in the present and the ways of their representation, which resulted in a chaotic search for a new institu- tional model capable of comprehending the phenom- enon of the actual.

Method

The theoretical basis of this study was constituted from the works of culturologists and art critics P. Osborne, V. Miziano, M. Andryczyk, O. Petrova, B. Shumylovych, M. Kosmolinska, A. Zvizhynsky, V. Melnyk. Peter Osborne,in his book Art Space, analyzes the dialectic of the relationship “place” - “non-place” (Osborne, 2013). V. Miziano considers “hangout” as a specific non-political socio-cultural formation (Miziano, 1999). M. Andryczyk, in his analysis of Ukrainian literary circles of the 1980s (2018), applies the theory of community, structure, and unity, which gives voice to marginalized circles and at the same time supports diversity. The author relies on the work of poststructuralists Todd Gifford May, Agata Bielik-Robson and Honi Fern Haber, noting the multicul- turalism and openness of new communities (Andryczyk, 2018). According to O. Petrova (2004), the birth ofthe domestic gallery movement was facilitated, on the one hand, by the academic professionalism of artists, on the other, by their double dialectical existence in the context of “underground revolt”. She notes that the beginning of gallery practice is characterized by “romanticism”, which is determined primarily by “poly- stylistic democracy” and respect for the individual, deprived of control by the manager. Actualizing theindependent galleries of Lviv in the late 1980s and early 1990s, A. Zasedko assigns to “non-place” gallery, CCA, museumspace “creating a dialogue around works ofart, legitimizing the meanings created by artists behind closed doors of their art workshops” (Zasedko, n.d.).

General scientific culturological and art history meth- ods are used; system analysis allowed us to invoke the progressive experience of foreign researchers.

Formal-stylistic and comparative methods were used to describe and analyze self-created institutions. The method of interviewing became important, which allowed determining the state of today’s fixation and museification of practices in a specific regional situ- ation. Given the culturological aspect of the issue, we consider the relationship between artist and institution through the prism of time (1990-2010).

The empiricalbasis of the study consisted of a review of catalogs, gal- leries, documents of private archives, bookstores, etc.

For the first time in the national discourse, this article covers the issues of grassroots institutionalization of contemporary art in Western Ukraine from the 1990s to the 2010s.

Results and Discussion

Gallery practices of the late twentieth - early twenty-first century

The emergence of club-type alternative art galleries began with the self-organization of artists. The first means of representation was the “hangout”, as an original socio-cultural phenomenon that has no his- torical analogues (Miziano, 1999). The hangout does not belong to the underground, its self-organization is associated with a situation of lack of repressive pres- sure and exhaustion of consolidation on the principles of ideological unity, ethics of confrontation. It is char- acterized by a type of relationship aimed at potentiality, belief in rapid institutionalization through project affili- ation, and market integration. The hangout belongs to the symptoms of post-ideological culture, which does not recognize public opinion, does not produce artis- tic trends and schools, a single system of values, nor authorities. It is marked by polystylism, and does not recognize nor support charismatic authorities or suc- cessful heroes. The hangout type of galleries and group exhibitions in this period is typical for the whole Eastern European space. The phenomenon demonstrates the presence of the phenomenon of common language and aesthetics (Pospish, 1999).

Self-organized galleries

Rejecting the understanding of the value of old institu- tions as ineffective, the participants of various hang- outs promoted the idea of creating new ones, through which they tried to institutionalize their own under- standing of art. “First of all, they offered topical forms of interaction with the audience. There was a reorien- tation of genre-species canons to ‘visual art’ with its conglomeration of actionism, performance, happenings, video art, installations” (Pospish, 1999).

The first galleries did not have an official status and registration. Belonging to the gallery was declarative, and low prices for utilities and lack of rent allowed conducting quite risky artistic activities related to the representation of current practices in the club environ- ment, more typical of formations such as the Centerof Contemporary Art (CCA). The function of the gallery owner was to provide premises, organize group exhibi- tions. Most of the galleries did not have any information in the central media space, which reduced their activi- ties to marginalization and caused controversy overthe institutionalization of art. Georgy Kosovan’s memoir about the exhibition of pastels and collages by Larysa Yevdokymenko in the Three Points Gallery is significant: “People came and wanted to buy Yevdokymenko’s works, but Dima (Shelest) then said that they could not be sold. As a museologist, he believed that art belonged to muse- ums, not taking into account the fact that the artist had to live for something” (Apolitychnyy prostir, 2016).

Among the first Western Ukrainian galleries of the hangout type, there were Lviv’s “Three Points” (G. Kosovan, 1988-1996, 1990 Research and Production Implementing Enterprise “GalArt”, MP “GalArt”), “Center of Europe” (Yu. Sokolov, since 1987). The latter is known for organizing the cult exhibition “Theater of Things, or the Ecology of Objects”, curated by Yu. Sokolov. Later, Yu. Sokolov’s new projects were the Decima gallery (1993-1994) and the Red Ruras gallery as public non- profit institutions founded by “a narrow circle of the Lviv intelligentsia culturologists, artists, architects, and writers”. Among the group projects of “Decima”, the conceptual ones prevailed: the exhibition “Search of Capricious Seductions” (13 authors: Lviv, Kyiv, Bern) painting, graphics, installations, clothing design were presented; reinstallation “Transit” by Yu. Solomko, action “Million Flowers” by Yu. Sokolov, controver-sial “Mitoforms”. “Red Rures” (24 Evremova Street) (Domashchuk, 2017) was an example of an apartment gallery that combined the functions of art and ver- nacular spaces. During the four years of the space’sexistence (since 1995), about 20 art projects have been realized here.

Gerdan Gallery (1996, 4 Ruska Street; art director, cura- tor Yu. Boyko, director O. Sheika) represented artists who were members of the society “Shlaykh” (Way). The curator’s activity was not limited to the gallery. Among the first significant projects of the gallery, there was the exhibition “Spirit. Body. Mind” with the participation of L. Medvid, M. Malyshko, E. Ravsky, E. Leshchenko, I. Podolchak, V. Kostyrko in Lviv (1997) and Kyiv (1998).

Yu. Boyko combined the functions of art critic, TV jour- nalist, manager, and exhibitor. The Gerdan Association became the initiator and co-founder of the Lviv Biennial of Ukrainian Fine Arts “Lviv 91 – Renaissance”, which represented the works of more than 250 Ukrainian art- ists around the world; among other things, Yu. Boyko was the curator of the exhibition block “New Generation of Lviv Artists” at the Impreza-95 Biennial, V. Kostyrko’s project il`ustraciji istoriji “istoriji Mystectva”, presented by the gallery at the Lviv Festival of Contemporary Culture “Cultural Heroes” (2002).

The Dzyga Art Association (1993, 4 Pidvalna St., 1997 Virmenska, 35) was formed in cooperation with activists of the Lviv Student Brotherhood: M. Ivashchyshyn, A. Rozhnyatovsky, J. Rushchyshyn with theater director S. Proskurnya and artist V. Kaufman. Starting with a hang- out, Dzyga brought together writers, musicians, and artists. Non-commercial exhibition activities were par- tially offset by commercial additions to the café and bar spaces. In 2002 at the festival “Cultural Heroes”, the gallery represented a series of projects that combined performance, installation, and multimedia: “Ecology 3000” by V. Bazhay, multimedia “Entrance-Exit” by A. Sidorenko and S. Yakunin, Uzhhorod projects “Adama Terra” by P. Kovach, “Named Dreams” by T. Tabak, “Landscape by heart” by G. Bulets. Since 2009, Dzyga has become an institution associated with the activities of the informal Uzhhorod group of artists “Esmarch’s Circle”: projects “Animal World” (2009), “Minimum / Maximum” (2010), “Recipes of Doctor Esmarch” (2013).

Yarovit Gallery (1996, A. Sheptytsky Foundation prem- ises; founder Yu. Sytnyk, director O. Noha) conducted patronage activities, organized literary evenings, theat- rical and musical activities.

The first art gallery of Uzhhorod “Dar” (curator and director, B. Vasiliev-Sazanov) appeared in 1993 in the premises of Uzhhorod Castle. The gallery is associated with the representation (1996) and support of membersof one of the first Transcarpathian informal art asso- ciations “Poptrans”. The Uzhhorod art hangout of the 1990s gathered in a crowded building on Shumna 1, group exhibitions-actions were staged in unsuitable abandoned premises, in the middle of the city; after all, the Transcarpathian underground is better known for its galleries in Lviv, open airs in the Czech Republicand Slovakia, and Hungary. Namely the immersion in the Czech underground in 1996 broadened the hangout’ understanding of contemporary art.

The Corridor Informal Gallery in Uzhhorod was officially founded in July 2002 (7 Parkhomenko St., curator, P. Kovach). The main space of the second floor of the art workshops of the Transcarpathian Art Gallery, where the studio of Pavlo Bedzir and Elizaveta Kremnytska was located, became an alternative gallery for self- organized exhibitions in the 1990s at the initiative ofP. Kovach and M. Syrokhman. Namely here the famous “op-art” exhibition with the participation of P. Bedzir took place. Since 2011, the space has been transformed into a workshop-museum of P. Bedzir, a public library,a residence, and a project space.

Ivano-Frankivsk self-organized hangouts of the late 80’s and early 90’s, “St. Art” by O. Chulkov and A. Zvizhinsky (in a varied spelling St. Art - Stanislav-art), “February”by M. Panakov (1991), later “Hyperfuturism” (2000), became more active through commercial connectionswith galleries in Moscow and St. Petersburg, then still Leningrad. Creative Center “Parallel Art 10×10+1” (M. Panakov, 1997) united in joint projects artists, musicians, theatergoers; the project “Another Territory” was one of the first public representations of the art of the mentally ill (2000, IFONSHU Exhibition Hall).

Creative exhibitions and meetings of hangouts took place in the format of apartment houses, city open- ings in order to enter the art market. One of the famous apartment galleries “Sigma”, popular for its exhibition activity, public lectures and debates (12 Hrushevskoho Street), belonged to the amateur artist Viktor Maistrych. The gallery was the location of separate curatorial expositions of the Impreza-97 Biennale, namely, exhibi- tions of erotic graphics “Ancient Series” by A. Miro (Spain) and erotic photos by S. Bratkov (Kharkiv).

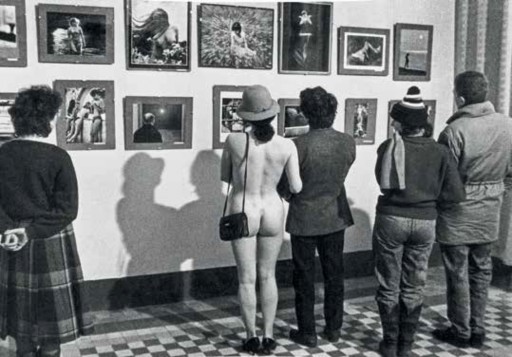

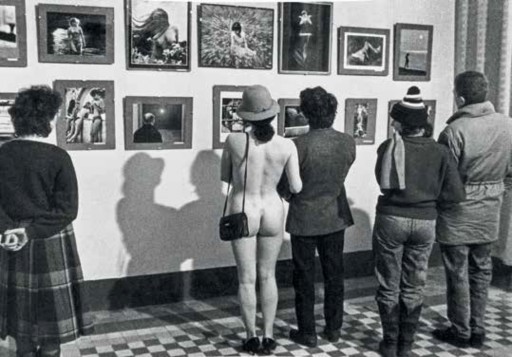

Among the first galleries with the function of CCA, which was a free space for artistic expression, in Ivano-Frankivsk is the “Carpathian Cultural Center” by Yu. Picard on the street Radyanska local ‘hundredmeters.’ The first issues of “Thursday”, audio cassettes with recordings of rock bands were distributed here.In 1990, the first exhibition of nude photography took place here: posters with Playboy girls were publicly presented in the windows of the gallery; J. Protsiv andV. Pylypyuk are well-known among the participants of the photo exhibition. In the space of this exhibition,R. Kondrat installed his own famous photo work “Case at the Exhibition” (Image 1). M. Yaremak’s personal exhibition (1990) was marked by an unconventional advertising campaign in the format of the author’s per- formances: the author installed an object-subject situa- tion formed from an old chair and a magnificent picture frame on the aisle in front of the CCA. The revival of the situation was not only due to the creation of an obsta- cle in the middle of the street, but also the presence of an artist who, imitating a “living” self-portrait, showeda twist, made speeches, astonishing passers-by.

Despite the success and publicity of the first Imprezas, the Ivano-Frankivsk hangout in the early 1990s wasin a situation of institutional and symbolic vacuum, which led to the loss of participants’ sense of reality and redistribution within the group. The members of the Stanislavsky Phenomenon group (June 1992, the Ruberoid collective exhibition) sought excessive action, supported by media attention, loud slogans with numer- ous manifestos, such as: “We love ourselves as muchas we can love. Can we say anything better than us? Is it possible not to say anything (better than us) without saying a word? It is possible. And this is our first great merit. Real art is neither exciting nor disgusting. Real art does not evoke. Real art is not noticed. We could not go unnoticed. We didn’t even make it. This is our second great merit. We are not trying to be pale. We are paler than a pale shadow. The merit is not ours. Thanks to Mother Nature” (Manifesto, 1991, p. 3).

Image 1

R Kondrat The Case at the Exhibition Art photography

The last decade of the twentieth century was marked by a significant number of potential and implemented projects of the group: parallel to the official program of Impreza, led by a hangout and registered as Impreza, individual and group grants, supported by CCA Soros (Melʹnyk, 2003). Discussions of future projects were inevitably connected with the planned disturbances of traditional society, festival programs of Kyiv, Lviv, Linz, Dachau, St. Petersburg, and the attempt to verbalize one’s own art in the context of “border time” resulted in a series of assertive practices and the emergence of culturological journals like “Pass”, “Pleroma” and “The End”. A. Zvizhynsky’s curatorial ambitions at this time were loudly realized by the presentation of the national section “Gentle Terrorism” at the IV St. Petersburg Biennale: “Eastern Europe: Spatia Nova” (1996), with the participation of R. Koterlin, J. Yanovsky and M. Yaremak. The initiative of “terrorism” was prone to quantitative provocations, so it was later reproducedin Ivano-Frankivsk in the programs of the biennial“Impreza-97” and the All-Ukrainian festival “Cultural Heroes” (2002).

M. Yaremak’s independent gallery projects in Ivano- Frankivsk in the late 1990s and early 2000s can be described as ambitious actions by one artist, an attempt to reform the city and create club-type artistic territories, with clearly defined aesthetic, advertis-ing, and pragmatic functions. According to the artist himself, these are acts of his own work, similar in nature to classical painting, but realized in the social plane; long-term performances in which the gallery area and visitors are used as art material. Similar laboratory tests in the same period are conducted in Lviv by V. Kaufman. The objects of his research are the cult cafes Babylon XX, Doll, and the audience involved in the directed action acts as a staff (Slipchenko, 1996).

To this day, M. Yaremak’s gallery practices in art his- tory literature and mass media are mentioned with- out proper chronology and indication of the realized tasks, due to which their significance is diminished. “Window” Gallery (Image 2) (1991)—a space-room in the Gartenberg Passage—focused on commercial and promotional tasks. The place was popular in the imme-diate vicinity of the exhibition hall “Imprezi-91”, the cult cafe “Under the Chestnuts”.

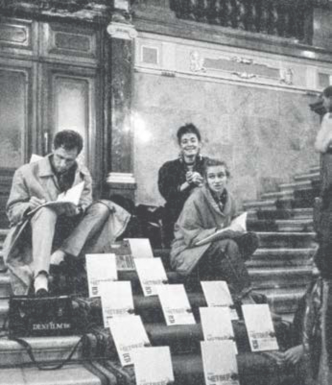

Among the tasks of the cultural space S-object (June- December 1993, Bandera Street, 1) were: fixing the real estate of art in Ivano-Frankivsk through the quanti- tative filling of the gallery with new art artifacts and creating a communicative field to activate artistic and cultural processes in the city, acquainting the com- munity with new phenomena, establishing contacts with the new political elite. The space became a bright business card of the city, united wide cultural circles, launched a number of actions, such as art workshops, weekly club meetings, which were later adopted by art- ists from Lviv, Kyiv, and other cities of Ukraine. Among the well-known actions of S-object, there are a meeting with O. Zalyvakha, the editorial board of the magazine “Fine Arts”, public philosophical lectures by V. Eshkilev,T. Prokhask (P. S. abo Nʹyu-Vasyukivsʹkyy proekt, 1994,p. 10), the performances “Letters of a French officer” by T. Prokhask and O. Hnativa, “Shaving the skull with an electric razor Izdrik” by Yu. Izdrik (Babii et al., 2021,p. 131). A separate project, “ZaImpreza”, although formally included in Impreza-93, became an indepen- dent curatorial project that demonstrated alternative art: performance, video art. Among the invited authors’ projects we can mention “Thing and Nothing” by UtaKilter and Viktor Malyarenko (Odesa), “Marginal Cinema” by Volodymyr Gulich (Zaporizhzhya), Volodymyr Fedirko (Chernivtsi), the solo action “Obroshyn-Lviv” by Petro Starukh (Lviv). Namely here the Frankivsk part of the famous performance by Yu. Sokolov, O. Zamkovsky, andS. Horsky “Cross-Transplantation of Independence” (Lviv), the performance “Cocoon” by M. Yaremak, T. Prohaska accompanied by Polish cellist Tadeusz Wilecki (Image 3) took place.

Image 2

Gallery of M Yaremak Window Photo by Lubomyr Stasiv

The “S-Object” space (1997-2001, 5 Shashkevycha Street), despite the primacy of commercial purposes, assumed the tasks outlined by the previous spaces. Namely, the cultural practice of “framing”, which transformed a work of art—an artifact—into an object with a commercial purpose, a commodity. The gallery featured the first installation composition on the facade in Ivano-Frankivsk, which showed the already known “Objects”: “jewels made of cut metal a flag and a chair. The interior design should flow freely into the outdoor space of the street (city).

The place (‘it is here’) accen- tuated in this way simultaneously turned into a gesture of good will, an invitation to establish connectionsbetween society and art” (Melʹnyk, 2003). Among the ideological tasks set by the artist in this space were the cultural resistance of the capital, which attracted creative personalities; the study of new provincial regions, especially in the east, “providing opportunities for self-realization to those people who want to prove themselves something radical, to reveal themselves as ‘others’” (Yaremak, 1998). The gallery is known, among other things, for its representation of postmodern expositions like “Impreza-97”: the photo project ofI. Chichkan, “Sleeping Princes of Ukraine” (Kyiv); the installations of Yu. Izdrik. “Farewell to Fish” (Kalush), and M. Yaremak “Permanent Christmas” (Ivano- Frankivsk); O. Borisov’s program painting (Kharkiv) “Franco vs Franco” was also exhibited here.

Center for Contemporary Arts (CCA)’ initiatives Issues around the institutionalization of contemporary art have been raised by the Western Ukrainian art com- munity since the early 1990s. The idea of creating the first Museum of Contemporary Art in Ukraine belonged to the initiative of the Impreza Foundation.

Already in 1991, changes in the political system and the economic crisis revealed the impossibility of the International Biennale of Contemporary Art in Ivano- Frankivsk, as well as the “Renaissance” in Lviv as a phenomenon, but began their gradual transformation into a process and discourse to create an information environment. The channel of “flow” of information was conceived on the basis of Western European models: exhibitions, fairs, auctions, criticism, catalogs. In this situation, Impreza was to become a new institution capable not only of retransmission, but also of theo- retical analysis, and structuring of visual and verbal information.

Image 3

Cocoon performance Photo by Lubomyr Stasiv

Participants of the conference on contemporary art “Impreza-off-season” (Ivano-Frankivsk, March 29 - April 1, 1995) tried to theorize the problem of trans- forming the chaotic public initiative Impreza into a structured and funded state program that could ensure a register of events and their inclusion in cultural and artistic contexts. However, it is noted that the search for a communicative model is ineffective due to the process of “permanent changes of cabinets” (ScientificConference on Contemporary Art, 1995, p. 5), and one- time actions are not able to create a tradition.

The Center for Contemporary Art (CCA) was seen as a process, a time-consuming permanent action of the Biennale, which expanded information oppor- tunities. The issues of creating a stock collection of the Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art were declared at each program and intermediate event ofthe Biennale, including the regulations on the Impreza auction (1990). The pricing policy of the Frankivsk auction was lower than that of Sotheby’s in Moscow in 1988, but it influenced the purchasing policy of several Ukrainian art museums present. The location of the exposition of the Second Biennale (1991) in the archi- tectural monument of the early twentieth century the former passage of the Gartenbergs—led to the initial discussion about the project-adaptation of this monu- ment for the functions of the Museum. The complex was considered from the standpoint of creating condi- tions for exhibition and creative activities, the forma- tion of collections, the creation of a competitive art market, and the location of various cultural institutions.

However, the privatization of the monument, the lack of funds, and the impossibility of publishing catalogs at Impreza-93 caused an organizational crisis that resulted in a decline in organizational initiatives and the realization that only state care could guarantee the preservation of contemporary art. The partial institu- tionalization of the Biennale and the first practical step towards studying the collection took place through the creation of the “post-Impreza” sector of contempo- rary art (Babii, 2019, p. 188), headed by I. Panchyshyn, who at that time was also a member of the supervisory board of Soros.

The topic of representation of contemporary art, hold- ing periodic events in Ukraine and abroad was covered by participants of the scientific conference on con- temporary art “Impreza-off-season” (March 29-April 1, 1995, IFDHM, Villa Margoshes, Ivano-Frankivsk). In T. Prokhask’s report as the most constructive, proposed format of the Biennale as an information newspaper: “In fact, we do not own the situation, no. This is not only in terms of remoteness from the center, but also the existence of the center itself, if we only have a discourse. Therefore, to master the situation, we can approach this series of problems paradoxically in terms of mastering the process…” (Scientific Conferenceon Contemporary Art, 1995, p. 27). The idea of a joint periodical art newspaper, which will become an opera- tional information channel, will help artists get used to market conditions, said the secretary of public relations of the German cultural center Goethe Institute, critic,O. Butsenko (SCCA, 1995, p. 19). The idea of Impreza as a way to overcome peripherality for the country as a whole belongs to Yu. Andrukhovych: “Ukraine will cease to be the cultural periphery of the world when its cities cease to be the cultural periphery of Ukraine” (SCCA, 1995, p. 23).

The activity of the “contemporary art” sector was ter- minated in 1999. The funds of donated works for the creation of the planned Museum of Contemporary Art (currently 746 items in the MMP) are divided into cat- egories of temporary storage (482 items: paintings 88, graphics 347, sculptures 47) and fixed assets (264 pres-ervation units: 44 paintings, 209 graphics, 11 sculptures).

Practical steps towards the creation of a new institution in Ivano-Frankivsk began only in 1998 as a result of the development of a new policy of strategic development of the city. At the end of 1999, the Public Initiative “Convention Museum of Contemporary Art” was regis- tered. Among the possible ways to implement the mainconcept, the creation of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Ivano-Frankivsk, the centralized state (the cre- ation of the Museum as part of the Municipal Art and Cultural Center) and the “grassroots” (lower) version were considered. The latter was understood as a com- bination of efforts of various institutions that support the idea of the Convention to create a civic “Museum- Center”. The plans of the Convention for the year 2000 included: the opening of the Museum of Contemporary Art, the formation of funds based on the collections of previous biennials, the involvement of the Faculty of Architecture of Lviv Polytechnic in the development of a project to adapt the architectural monument, the for- mer cinema “Ton” (1929) – cultural center, development of premises, opening and maintenance of a permanent page in the municipal newspaper, opening of the Web- page “Museum” on the basis of the server of one of the participants of the Convention, and the creation of its own Info-media bank, conducting a photo plein air. The Info-media bank was understood as a promising ele- ment of the virtual Museum of Contemporary Art. The decision was confirmed by the “Program of support and development of Ukrainian culture in Ivano-Frankivsk for the period 2001-2005” (Karas, 2001). During the activ- ity of the Art and Cultural Center (2001-2004, directorI. Panchyshyn), a number of synthetic programs wereimplemented, among which, first of all, media programs in the format of systematic articles in the municipal press. Among the exhibition projects, the most signifi- cant was the Center’s participation in the Festival of Contemporary Culture “Cultural Heroes” (2002), which demonstrated a separate cultural “profile” of the region, marked by the expected phenomenology.

So, as one can see, the most intense period of experi- ments with forms of institutionalization of practices falls on the last decade of the twentieth century. The hangout, as an active formation of the post-ideological epoch, needs to be quickly consolidated in the con- text of the epoch. Often ignoring the old institutions, hangout members became more active in their own institutional creation. During this time, the foundations of the club and gallery movement were laid, attempts to create institutions modeled on the CCA, which began the process of reforming the centers of art and culture, created conditions for highlighting alternative regional intellectual and creative autonomy. The key positions are the focus on international relations, laboratory research, commercial profit, public relations.

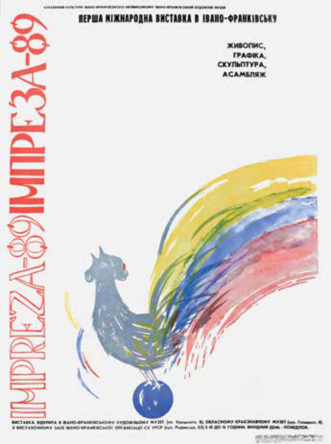

Image 4

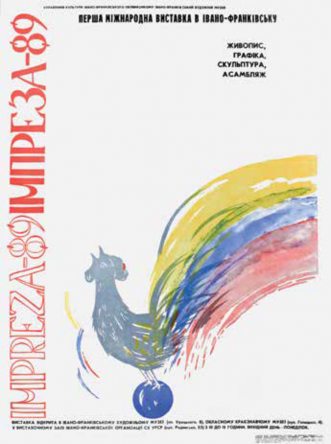

Impreza89 poster From the private archive of I Panchyshyn

Representation of contemporary art through book production

The period of the 1990s, despite all the difficulties in economic life, became significant for the situation of cultural “openness” of the western Ukrainian region, which caused a change in aesthetic standards and artistic coordinates—there was an inorganic abrupt transition from socialist realism to postmodern dis- course. We emphasize once again that one of the cata- lysts of this process was the first international biennial of contemporary art Impreza (Babi, 2019) in Ivano-Frankivsk (1989). The unexpectedness of this action in Ivano-Frankivsk (for a long time a “closed city”) isevidenced by the fact that in addition to artists, envoys from Kaliningrad and Lviv came to Impreza to learn from the experience of such actions. After this project the following events took place in Ukraine: “Block 4”in Kharkiv, “Interdruk” and “Renaissance” in Lviv, “Pan Ukraine” in Dnepropetrovsk. Given the present state of things, we realize that the time of the “stormy” 90’s was a unique start for the development of not only art but also alternative forms of representation, including design, research and advertising.

A significant part of the works sent to international exhibitions was graphics—prints of works by Japanese,Swedish, Slovak artists of world level, which could not but affect the cultural processes, including transforma- tions in printing. The breakthrough of new art forms was, albeit short-lived, obvious. The printing of the first post-Soviet poster of Impreza, with the famous rooster Anthony Miro (Image 4), was experiencing difficulties due to technological backwardness. The initiative group Impreza has mastered on its own also other, already familiar to our time, printing techniques. For example, the famous handmade craft envelopes have become almost their biggest brand. It was noticed abroad in design schools precisely because of the archaic novelty.

When the third Impreza (1993) was being prepared, the poster was mounted from improvised materials as a collage, which provided for fast, cheap, and simple technological printing. On the way, a large trio was cut with scissors from scraps of raster-tangier sheets, an inscription about the exhibition in the usual font was added from the already extracted to the required scale, and a rooster, which became a recognizable sign, was also cut out of black paper. All this was pasted on a half-sheet of paper and immediately sent to a photo- copier. Due to the lack of quality paper, the “construc- tivist minimalism” inherent in many things in Impreza was fully adhered to.

Having formed a special model of behavior, the intel- lectuals of the 80s generation, unfortunately, did not create a mass demand for the product of the Ukrainian intellect. As a result, Ukrainian books, like contemporary art in the mid-1990s, “almost disappeared everywhere”, as they did not fit into the interests of new state policies. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, a new representative space of current litera- ture was book production, organized by the generation of the 1990s. Its formalization and the newly created interpersonal contacts within this space, constituted objects of aesthetic evaluation and became a factorin stabilizing the structure, which we define not as a model of the old institution, but as a relationship that supports marginal circles.

In the early and mid-90s, state-owned publishing houses and printing houses were liquidated as econom- ically unviable and technically obsolete, and the first private publishing houses with a large share of foreign investment appeared on the market. The products were technically manufactured outside Ukraine, mostly in Poland and the Czech Republic. One of the first such entrepreneurs was the co-founder of Impreza, M. Vitushinsky. After the first wave of intellectual maga- zines of the 90s, Ukraine was captured by the second wave of popular, entertaining and “glossy” magazines of the 2000s. Technically, this was due to the transition to digital printing, and bringing the textual and illustra- tive material under a single denominator. The economic feasibility of printing in arbitrary formats and smalleditions (which was not available in the previous period) created the conditions for the operating space, which synthesized certain types of graphic activities into a single type printing design.

New Western Ukrainian publishing houses - “Lileya” (Ternopil), “Lileya-NV” (Ivano-Frankivsk), Lviv “Light and Shadow” and “Gerdan-Grafika” played an important role in consolidating regional phenomenology. The found- ers of the enterprises belonged to various patriotic societies and alternative parties of the 1990s, were well versed in the current cultural and artistic processes of their time, had close contacts with action artists, writ- ers, progressive actors and directors, museum workers, supported creative experiments, and were often par- ticipants of performances, apartment exhibitions and festivals of alternative art. From the beginning, their economic activity was based on publishing, in some cases managing the complete process, which included prepress, printing and bookbinding. Starting with the study and distribution of computer technology (Lily-NVcollaborated with Macintosh), the first graphic editors, the founders of these companies have played an impor- tant role in the competitiveness of their products, given the Western market. In the following years, the number of enterprises increased, subsidiaries were established. Some publishing houses later moved away from the main activity, focusing on printing services. Others have created their own style of publishing, which has now become a national brand and is easily recognizable at cultural attractions, literary festivals and book forums both in Ukraine and abroad.

The success of the Kyiv publishing house of children’s literature A-BA-BA-GA-LA-MA-GA, founded in 1992 by Ivan Malkovych, a native of the village of Lower Bereziv, Kosiv district of Ivano-Frankivsk region, had a huge influence on the development of national book publish- ing. The founder managed to unite outstanding graphic artists, illustrators, translators, and designers around the publishing house. The precedent of the book asa work of art was realized in the first edition of the “Alphabet” (1992), which is often defined as the best after the Narbut model. Lesia Ganzha calls this publica- tion a case when a creation absorbs its creator, becom- ing a “text of a lifetime” (Hanzha, 1999). In the early 2000s, A-BA-BA-GA-LA-MA-GA was distinguished by a kind of mail-art action: the MiniDivo project represented 1,600,000 beautifully illustrated books of the mini- format for a price of one hryvnia through a networkof post offices. Consumer appreciation resulted in a significant number of letters sent to the editorial office.

Lviv publishing house Gerdan-Grafika had one of the first powerful technical bases and a creative team of graphic designers that had no analogues in Western Ukraine. Focusing on a commercial mission, the pub- lishing house was engaged in book production only in some cases initiated by customers. The publication Give us an Easter egg, 1998, reprint in 2000—(Margarita Boyko, LLC Firm Nadiya, editor, author and compiler of texts Nadiia Babii, design by Bohdan Hubal), becamea complex project that combines artistic, marketing, and promotional initiatives (Podaruy my pysanochku, 2001). The impetus for the creation of the book was an exhibition of children’s drawings of Easter eggs, rep- resented as an installation structure under the ceiling of the trading hall of a commercial structure in Ivano- Frankivsk. Involvement of famous artists (Opanas Zalivakha, Bohdan Hubal) in the jury of the competition, and of the Minister of Culture, Bohdan Stupka, in the publication of the album, along with representationsof a number of prominent people (including Pope JohnPaul II), and an innovative design, turned the album into a kind of media phenomenon. For the first time, the publication was preceded by the use of “guerrilla marketing” tools, namely a non-standard campaign, one of the elements of which was the distribution of special advertising templates in the form of eggs and descrip- tions of drawing conditions at supermarket checkouts.

Ivano-Frankivsk Publishing House of Contemporary Ukrainian Literature—“Lily-NV” by Vasyl Ivanochko— was founded on October 14, 1995 by the Ukrainian Scout Organization “Plast”, formed from the Ternopil “Lily” by Myroslav Pavlovsky. The activity of the publish- ing house is associated with the institutionalization of the visual-verbal “Stanislavivsky phenomenon” as one of the “most enduring cultural groups in post-Soviet Ukraine” (Andryczyk, 2018, p. 164). The process took place under the influence and with the direct participa- tion of cult figures from this community.

As in the case of the museum institution, book pro- duction in the late 1990s became a space for the representation of marginal communities, including the self-representation of artists and a place for the institutionalization of their texts in the context of the cultural period.

Namely in “Lily-NV”, Yu. Andrukhovych’s works were first published: Reactions and Perversion (1997). The latter received an award from the Publishers’ Forum in Lviv in 1997; O. Rubanovska’s design and layout were innovative for their time, and a constructive paperback valve was used for the first time. He later published Exotic Birds and Plants with the addition of India: A Collection of Poems (1997), later: Disorientation in the field (1999), Muscovy (2000), Songs for a dead rooster (2004), and a gift set All Andrukhovich (2005).

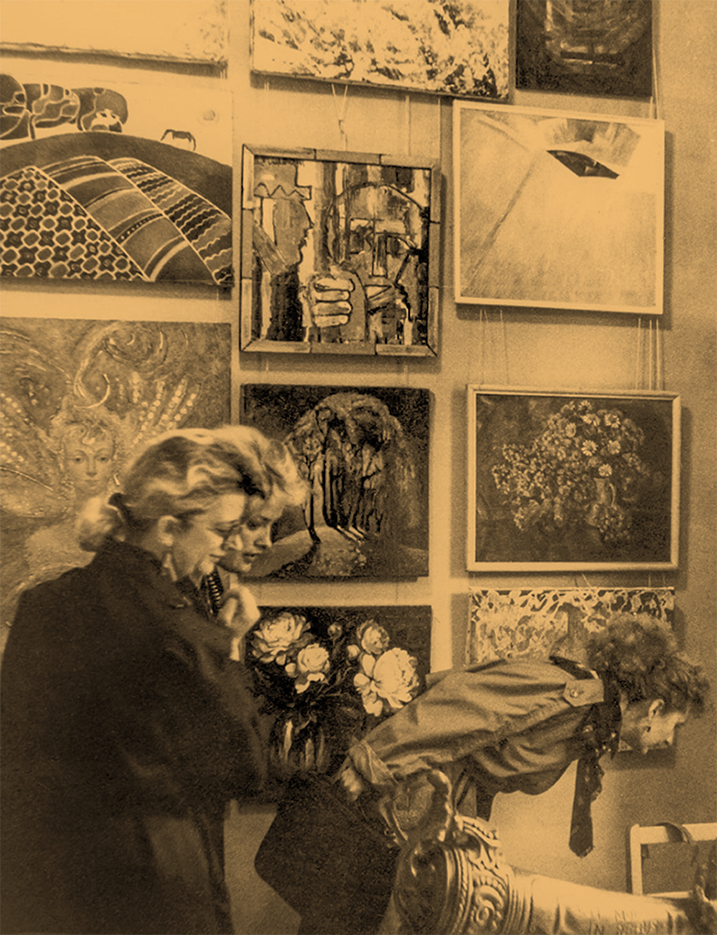

The publishing house took care of the issue of the maga- zines “Thursday”, “Pleroma” and “The End”, launched the project of the library of the magazine “Thursday” (Image 5), and organized presentations of publications in book fairs and other venues. In the first issue of “Pleroma”in 1996 (ed. V. Eshkilev), the “Postmodern Situation” by Lyotard and “Stanislav: longing for the false” by Yu. Izdrik were published for the first time in Ukraine.

During numerous book presentations, aesthetic hyper- text technologies were actively used: performance, reperformance, dramatization, elements of carnival culture, visiopoetry, simultaneously as ways of nonlinear presentation of information and marketing strategy.Among the cult novels, V. Ivanochko published in 1997 Wotzcek by Yu. Izdryk, and later Island KRK (1998) and Double Leon (2000) by the same author. Izdryk dis- tinguished himself by his design collaboration with the publishing house he became the author of a number of well-known covers, including his own novel Flash and a poster composition for the cover of Barrier by Tatiana Yarushevich (2009). A series of his famous collages became the basis of the cover and illustrations for Andrukhovych’s Exotic Birds and Plants.

Among other endeavors we can mention Janowski’s publishing project “Landscape” (1996) combines media and communication. A. Sereda’s intellectual sketch poetry Homo Viator (2006), Animal World of Anna (1997) by O. Rubanovska, visual poems by M. Korol Time of the Ripe Stone (2003), Laws of Geography (1997) by Anton Gavriliv with elements of visiopoetry; the project Another format (2003) a documented performance ofT. Prokhask with Ukrainian philosophers, theologians, writers were published as separate projects.

One cannot miss the bold experiment of the partici- pant of “Stanislavsky Phenomenon”, artist and designer Olena Rubanovska founding her own publishing house Kashalot, which specializes in “smart” books for the youngest readers. Publishers called their creations “pillow books”. In online stores, they are advertised as books that one can “bite, twist, even sleep on them”, created for those “who cannot read”. Among the Ukrainian publishing houses, Kashalot is the first and only to publish such books. The production processis extremely time-consuming: more than 700 operations during the work on one book. In the collection of Kashalot, in particular, we can list several titles: Morning at Grandma’s, Good night, Let’s go to visit!, Iasi Day, Christmas in Bethlehem, The train is going!, I love Daddy!, He’s always with me!

Image 5. Yuriy Izdryk, Anna Kirpan, Maria Mykytsei at the presenta- tion of the first (third) official Thursday at the Lviv Opera, 1992, ViViH- 92 festival. Photo by Denis Ovchar.

Conclusion

Art experiments of the late 1980s catalyzed cultural, artistic, and socio-cultural processes. First of all, the creation of an information environment that resulted in the decentralization of the domestic art scene and the intensification of regional phenomena, including a large number in Western Ukraine. The need to consolidate contemporary art resulted in representation through grassroots institutionalization. The processes of forma- tion of “cultural” capital combined social, political, and bureaucratic components. Artists, being directly in the “field of art”, acquired the status of stars, individual institutions, parts of marginal myths, moving to the “field of culture”. We note their role in creating an insti- tute of independent curators involved in the mediation of art, the creation and management of multiple artistic environments for cultural dialogues.

Formal legalizationwas implemented through the development of private collecting, the emergence of the private gallery sector, publishing houses, media formats, in which hangout members played an important role.

We are convinced that the beginnings of the develop- ment of Western Ukrainian book production depended not only on legislative and economic conditions, but also on a system of cultural factors, including the legalization of alternative art forms associated with the activity of multicultural marginal environments, first of all the Stanislavsky Phenomenon. Attempts by artists to join social or economic mechanisms resulted in the representation of art in real parameters, rather than ephemeral projects.

References

Andryczyk, M. (2018). Intellectual as a hero of Ukrainian prose of the 90s of the twentieth century. Lviv: “Pyramida”.

Apolitychnyy prostir (2016). https://mitec.ua/apolitichno-prostranstvo/

Babii, N. (2019). “Impresa” as a catalizer of art-cultural processes in Ukraine of the 90-s years of the 20th century. Ukrainian culture: the past, modern ways of development, 31, 187-193.

Babii, N., Hubal, B., Dundiak, I., Chuyko, O., Chmelyk, I., Maksymliuk, I. (2021). Performance: transformation of the socio-cultural landscape. AD ALTA: Journal of interdisciplinary research, 1(XVII), 129-133.

Domashchuk, H. (2017). Activities of art galleries in Lviv in the late 80’s - early 90’s of the twentieth century.

Hanzha, L. (1999, August 11). Lyrics instead of propaganda posters. Day, 146.

Karas, G. (2001). Ivano-Frankivsk: cultural and artistic chronicle of Independence. Ivano-Frankivsk: Nova Zorya.

Manifesto. Impreza. Provintsiynyy dodatok Nº2 (1991).

Recibido: 24 de junio de 2022; Aceptado: 27 de agosto de 2022

Resumen

El estudio examina las estrategias y prácticas utilizadas por los artistas en el oeste de Ucrania para promover y representar el arte contemporáneo a finales del siglo XX y principios del XXI. Nuestra atención se centra en el papel de las instituciones culturales y artísticas en la configuración del valor del arte durante una época de crisis y cambio en la jerarquía de estas instituciones.

El estudio utiliza una variedad de fuentes, incluyendo catálogos, folletos de galerías, archivos privados y productos de librería actuales, así como entrevistas con participantes en estos procesos. Argumentamos que el surgimiento del arte contemporáneo en Ucrania occidental está estrechamente relacionado con la formación de un capital cultural a fines del siglo XX gracias a la participación de capital social, político y burocrático. El estudio también analiza las formas en que los artistas y poetas han pasado de la «esfera del arte» ala «esfera de la cultura» al convertirse en «estrellas» y crear sus propias instituciones, como curadurías independientes, entornos artísticos para el diálogo cultural, galerías privadas, editoriales y distintos formatos mediáticos.

Palabras clave

Galerías autoorganizadas, publicación de libros, contexto institucional informal, arte contemporáneo, Ucrania occidental.Abstract

This study examines the strategies and practices used by artists in Western Ukraine to promote and represent contemporary art during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The focus is on the role of cultural and artistic institutions in shaping the value of art during a time of crisis and change in the hierarchy of these institutions. It uses a variety of sources, including catalogs, gallery brochures, private archives, and current bookstore products, as well as interviewswith participants in these processes. We argue that the rise of contemporary art in Western Ukraine is closely linked to the formation of cultural capital in the late 20th century, through the participation of social, political, and bureaucratic capital. The study also looks at the ways in which artists and poets have transitioned from the «sphere of art» to the «sphere of culture» by becoming «stars» and creating their own institutions, such as independent curatorships, artistic environments for cultural dialogue, private galleries, publishing houses, and media formats.

Keywords

Self-organized galleries, book publishing, grassroots institutional context, contemporary art, Western Ukraine.Résumé

L’étude examine les stratégies et les pratiques utilisées par les artistes de l’ouest de l’Ukraine pour promouvoir et représenter l’art contemporain à la fin du XXe et au début du XXIe siècle. L’accent est mis sur le rôle des institutions culturelles et artistiques dans la formation de la valeur de l’art en temps de crise et de changement dans la hiérarchie de ces institutions. L’étude utilise une variété de sources, y compris des catalogues, des brochures de galeries, des archives privées et des produits actuels de librairies, ainsi que des entretiens avec des participants àces processus. Nous soutenons que l’essor de l’art contemporain en Ukraine occidentale est étroitement lié à la formation du capital culturel à la fin du XXe siècle, à travers la participation du capital social, politique et bureaucratique. L’étude s’intéresse également à la manière dontles artistes et les poètes sont passés de la « sphère de l’art » à la « sphère de la culture » en devenant des « stars » et en créant leurs propres institutions, telles que des commissariats indépendants, des environnements artistiques pour le dialogue culturel, galeries privées, maisons d’édition et formats médiatiques.

Mots clés

Galeries autoorganisées, édition de livres, contexte institutionnel informel, art contemporain, Ukraine occidentale.Resumo

O estudo examina as estratégias e práticas usadas por artistas na Ucrânia Ocidental para promover e representar a arte contemporânea durante o final do século XX e início do século XXI. O foco está no papel das instituições culturais e artísticas na formação do valor da arte durante um período de crise e mudança na hierarquia dessas instituições. O estudo utiliza uma variedade de fontes, incluindo catálogos, brochuras de galerias, arquivos privados e produtos atuais de livrarias, bem como entrevistas com participantes desses processos.

Ele argumenta que a ascensão da arte contemporânea na Ucrânia Ocidental está intimamente ligada à formação do capital cultural no final do século 20, por meio da participação do capital social, políticoe burocrático. O estudo também analisa as formas pelas quais artistas e poetas passaram da “esfera da arte” para a “esfera da cultura”, tornando-se “estrelas” e criando suas próprias instituições, como curadorias independentes, ambientes artísticos para o diálogo cultural, galerias privadas, editoras e formatos de mídia.

Palavras-chave

Galerias auto-organizadas, publicação de livros, contexto institucional informal, arte contemporânea, Ucrânia ocidental.Introduction

The economic recession of the 2000s minimizes the share of private collecting, and at the same time the centralized printing activity. The publication of cata- logues, albums, monographs, booklets is absent or passes into the self-published stage or to the programs of new publishing houses. Active hangouts were the first to destroy the corporate framework, taking over the role of culturologists and publishers. They were also gallery owners, while gallery owners became politicians, theorists, image makers, and so on.

A keen sense of the acceleration of the historical rhythm at the turn of the millennium led to numerous discussions on the key problems of historical knowl- edge, including all aspects of the presence of the past in the present and the ways of their representation, which resulted in a chaotic search for a new institu- tional model capable of comprehending the phenom- enon of the actual.

Method

The theoretical basis of this study was constituted from the works of culturologists and art critics P. Osborne, V. Miziano, M. Andryczyk, O. Petrova, B. Shumylovych, M. Kosmolinska, A. Zvizhynsky, V. Melnyk. Peter Osborne,in his book Art Space, analyzes the dialectic of the relationship “place” - “non-place” (Osborne, 2013). V. Miziano considers “hangout” as a specific non-political socio-cultural formation (Miziano, 1999). M. Andryczyk, in his analysis of Ukrainian literary circles of the 1980s (2018), applies the theory of community, structure, and unity, which gives voice to marginalized circles and at the same time supports diversity. The author relies on the work of poststructuralists Todd Gifford May, Agata Bielik-Robson and Honi Fern Haber, noting the multicul- turalism and openness of new communities (Andryczyk, 2018). According to O. Petrova (2004), the birth ofthe domestic gallery movement was facilitated, on the one hand, by the academic professionalism of artists, on the other, by their double dialectical existence in the context of “underground revolt”. She notes that the beginning of gallery practice is characterized by “romanticism”, which is determined primarily by “poly- stylistic democracy” and respect for the individual, deprived of control by the manager. Actualizing theindependent galleries of Lviv in the late 1980s and early 1990s, A. Zasedko assigns to “non-place” gallery, CCA, museumspace “creating a dialogue around works ofart, legitimizing the meanings created by artists behind closed doors of their art workshops” (Zasedko, n.d.).

General scientific culturological and art history meth- ods are used; system analysis allowed us to invoke the progressive experience of foreign researchers.

Formal-stylistic and comparative methods were used to describe and analyze self-created institutions. The method of interviewing became important, which allowed determining the state of today’s fixation and museification of practices in a specific regional situ- ation. Given the culturological aspect of the issue, we consider the relationship between artist and institution through the prism of time (1990-2010).

The empiricalbasis of the study consisted of a review of catalogs, gal- leries, documents of private archives, bookstores, etc.

For the first time in the national discourse, this article covers the issues of grassroots institutionalization of contemporary art in Western Ukraine from the 1990s to the 2010s.

Results and Discussion

Gallery practices of the late twentieth - early twenty-first century

The emergence of club-type alternative art galleries began with the self-organization of artists. The first means of representation was the “hangout”, as an original socio-cultural phenomenon that has no his- torical analogues (Miziano, 1999). The hangout does not belong to the underground, its self-organization is associated with a situation of lack of repressive pres- sure and exhaustion of consolidation on the principles of ideological unity, ethics of confrontation. It is char- acterized by a type of relationship aimed at potentiality, belief in rapid institutionalization through project affili- ation, and market integration. The hangout belongs to the symptoms of post-ideological culture, which does not recognize public opinion, does not produce artis- tic trends and schools, a single system of values, nor authorities. It is marked by polystylism, and does not recognize nor support charismatic authorities or suc- cessful heroes. The hangout type of galleries and group exhibitions in this period is typical for the whole Eastern European space. The phenomenon demonstrates the presence of the phenomenon of common language and aesthetics (Pospish, 1999).

Self-organized galleries

Rejecting the understanding of the value of old institu- tions as ineffective, the participants of various hang- outs promoted the idea of creating new ones, through which they tried to institutionalize their own under- standing of art. “First of all, they offered topical forms of interaction with the audience. There was a reorien- tation of genre-species canons to ‘visual art’ with its conglomeration of actionism, performance, happenings, video art, installations” (Pospish, 1999).

The first galleries did not have an official status and registration. Belonging to the gallery was declarative, and low prices for utilities and lack of rent allowed conducting quite risky artistic activities related to the representation of current practices in the club environ- ment, more typical of formations such as the Centerof Contemporary Art (CCA). The function of the gallery owner was to provide premises, organize group exhibi- tions. Most of the galleries did not have any information in the central media space, which reduced their activi- ties to marginalization and caused controversy overthe institutionalization of art. Georgy Kosovan’s memoir about the exhibition of pastels and collages by Larysa Yevdokymenko in the Three Points Gallery is significant: “People came and wanted to buy Yevdokymenko’s works, but Dima (Shelest) then said that they could not be sold. As a museologist, he believed that art belonged to muse- ums, not taking into account the fact that the artist had to live for something” (Apolitychnyy prostir, 2016).

Among the first Western Ukrainian galleries of the hangout type, there were Lviv’s “Three Points” (G. Kosovan, 1988-1996, 1990 Research and Production Implementing Enterprise “GalArt”, MP “GalArt”), “Center of Europe” (Yu. Sokolov, since 1987). The latter is known for organizing the cult exhibition “Theater of Things, or the Ecology of Objects”, curated by Yu. Sokolov. Later, Yu. Sokolov’s new projects were the Decima gallery (1993-1994) and the Red Ruras gallery as public non- profit institutions founded by “a narrow circle of the Lviv intelligentsia culturologists, artists, architects, and writers”. Among the group projects of “Decima”, the conceptual ones prevailed: the exhibition “Search of Capricious Seductions” (13 authors: Lviv, Kyiv, Bern) painting, graphics, installations, clothing design were presented; reinstallation “Transit” by Yu. Solomko, action “Million Flowers” by Yu. Sokolov, controver-sial “Mitoforms”. “Red Rures” (24 Evremova Street) (Domashchuk, 2017) was an example of an apartment gallery that combined the functions of art and ver- nacular spaces. During the four years of the space’sexistence (since 1995), about 20 art projects have been realized here.

Gerdan Gallery (1996, 4 Ruska Street; art director, cura- tor Yu. Boyko, director O. Sheika) represented artists who were members of the society “Shlaykh” (Way). The curator’s activity was not limited to the gallery. Among the first significant projects of the gallery, there was the exhibition “Spirit. Body. Mind” with the participation of L. Medvid, M. Malyshko, E. Ravsky, E. Leshchenko, I. Podolchak, V. Kostyrko in Lviv (1997) and Kyiv (1998).

Yu. Boyko combined the functions of art critic, TV jour- nalist, manager, and exhibitor. The Gerdan Association became the initiator and co-founder of the Lviv Biennial of Ukrainian Fine Arts “Lviv 91 – Renaissance”, which represented the works of more than 250 Ukrainian art- ists around the world; among other things, Yu. Boyko was the curator of the exhibition block “New Generation of Lviv Artists” at the Impreza-95 Biennial, V. Kostyrko’s project il`ustraciji istoriji “istoriji Mystectva”, presented by the gallery at the Lviv Festival of Contemporary Culture “Cultural Heroes” (2002).

The Dzyga Art Association (1993, 4 Pidvalna St., 1997 Virmenska, 35) was formed in cooperation with activists of the Lviv Student Brotherhood: M. Ivashchyshyn, A. Rozhnyatovsky, J. Rushchyshyn with theater director S. Proskurnya and artist V. Kaufman. Starting with a hang- out, Dzyga brought together writers, musicians, and artists. Non-commercial exhibition activities were par- tially offset by commercial additions to the café and bar spaces. In 2002 at the festival “Cultural Heroes”, the gallery represented a series of projects that combined performance, installation, and multimedia: “Ecology 3000” by V. Bazhay, multimedia “Entrance-Exit” by A. Sidorenko and S. Yakunin, Uzhhorod projects “Adama Terra” by P. Kovach, “Named Dreams” by T. Tabak, “Landscape by heart” by G. Bulets. Since 2009, Dzyga has become an institution associated with the activities of the informal Uzhhorod group of artists “Esmarch’s Circle”: projects “Animal World” (2009), “Minimum / Maximum” (2010), “Recipes of Doctor Esmarch” (2013).

Yarovit Gallery (1996, A. Sheptytsky Foundation prem- ises; founder Yu. Sytnyk, director O. Noha) conducted patronage activities, organized literary evenings, theat- rical and musical activities.

The first art gallery of Uzhhorod “Dar” (curator and director, B. Vasiliev-Sazanov) appeared in 1993 in the premises of Uzhhorod Castle. The gallery is associated with the representation (1996) and support of membersof one of the first Transcarpathian informal art asso- ciations “Poptrans”. The Uzhhorod art hangout of the 1990s gathered in a crowded building on Shumna 1, group exhibitions-actions were staged in unsuitable abandoned premises, in the middle of the city; after all, the Transcarpathian underground is better known for its galleries in Lviv, open airs in the Czech Republicand Slovakia, and Hungary. Namely the immersion in the Czech underground in 1996 broadened the hangout’ understanding of contemporary art.

The Corridor Informal Gallery in Uzhhorod was officially founded in July 2002 (7 Parkhomenko St., curator, P. Kovach). The main space of the second floor of the art workshops of the Transcarpathian Art Gallery, where the studio of Pavlo Bedzir and Elizaveta Kremnytska was located, became an alternative gallery for self- organized exhibitions in the 1990s at the initiative ofP. Kovach and M. Syrokhman. Namely here the famous “op-art” exhibition with the participation of P. Bedzir took place. Since 2011, the space has been transformed into a workshop-museum of P. Bedzir, a public library,a residence, and a project space.

Ivano-Frankivsk self-organized hangouts of the late 80’s and early 90’s, “St. Art” by O. Chulkov and A. Zvizhinsky (in a varied spelling St. Art - Stanislav-art), “February”by M. Panakov (1991), later “Hyperfuturism” (2000), became more active through commercial connectionswith galleries in Moscow and St. Petersburg, then still Leningrad. Creative Center “Parallel Art 10×10+1” (M. Panakov, 1997) united in joint projects artists, musicians, theatergoers; the project “Another Territory” was one of the first public representations of the art of the mentally ill (2000, IFONSHU Exhibition Hall).

Creative exhibitions and meetings of hangouts took place in the format of apartment houses, city open- ings in order to enter the art market. One of the famous apartment galleries “Sigma”, popular for its exhibition activity, public lectures and debates (12 Hrushevskoho Street), belonged to the amateur artist Viktor Maistrych. The gallery was the location of separate curatorial expositions of the Impreza-97 Biennale, namely, exhibi- tions of erotic graphics “Ancient Series” by A. Miro (Spain) and erotic photos by S. Bratkov (Kharkiv).

Among the first galleries with the function of CCA, which was a free space for artistic expression, in Ivano-Frankivsk is the “Carpathian Cultural Center” by Yu. Picard on the street Radyanska local ‘hundredmeters.’ The first issues of “Thursday”, audio cassettes with recordings of rock bands were distributed here.In 1990, the first exhibition of nude photography took place here: posters with Playboy girls were publicly presented in the windows of the gallery; J. Protsiv andV. Pylypyuk are well-known among the participants of the photo exhibition. In the space of this exhibition,R. Kondrat installed his own famous photo work “Case at the Exhibition” (Image 1). M. Yaremak’s personal exhibition (1990) was marked by an unconventional advertising campaign in the format of the author’s per- formances: the author installed an object-subject situa- tion formed from an old chair and a magnificent picture frame on the aisle in front of the CCA. The revival of the situation was not only due to the creation of an obsta- cle in the middle of the street, but also the presence of an artist who, imitating a “living” self-portrait, showeda twist, made speeches, astonishing passers-by.

Despite the success and publicity of the first Imprezas, the Ivano-Frankivsk hangout in the early 1990s wasin a situation of institutional and symbolic vacuum, which led to the loss of participants’ sense of reality and redistribution within the group. The members of the Stanislavsky Phenomenon group (June 1992, the Ruberoid collective exhibition) sought excessive action, supported by media attention, loud slogans with numer- ous manifestos, such as: “We love ourselves as muchas we can love. Can we say anything better than us? Is it possible not to say anything (better than us) without saying a word? It is possible. And this is our first great merit. Real art is neither exciting nor disgusting. Real art does not evoke. Real art is not noticed. We could not go unnoticed. We didn’t even make it. This is our second great merit. We are not trying to be pale. We are paler than a pale shadow. The merit is not ours. Thanks to Mother Nature” (Manifesto, 1991, p. 3).

Image 1: R Kondrat The Case at the Exhibition Art photography

The last decade of the twentieth century was marked by a significant number of potential and implemented projects of the group: parallel to the official program of Impreza, led by a hangout and registered as Impreza, individual and group grants, supported by CCA Soros (Melʹnyk, 2003). Discussions of future projects were inevitably connected with the planned disturbances of traditional society, festival programs of Kyiv, Lviv, Linz, Dachau, St. Petersburg, and the attempt to verbalize one’s own art in the context of “border time” resulted in a series of assertive practices and the emergence of culturological journals like “Pass”, “Pleroma” and “The End”. A. Zvizhynsky’s curatorial ambitions at this time were loudly realized by the presentation of the national section “Gentle Terrorism” at the IV St. Petersburg Biennale: “Eastern Europe: Spatia Nova” (1996), with the participation of R. Koterlin, J. Yanovsky and M. Yaremak. The initiative of “terrorism” was prone to quantitative provocations, so it was later reproducedin Ivano-Frankivsk in the programs of the biennial“Impreza-97” and the All-Ukrainian festival “Cultural Heroes” (2002).

M. Yaremak’s independent gallery projects in Ivano- Frankivsk in the late 1990s and early 2000s can be described as ambitious actions by one artist, an attempt to reform the city and create club-type artistic territories, with clearly defined aesthetic, advertis-ing, and pragmatic functions. According to the artist himself, these are acts of his own work, similar in nature to classical painting, but realized in the social plane; long-term performances in which the gallery area and visitors are used as art material. Similar laboratory tests in the same period are conducted in Lviv by V. Kaufman. The objects of his research are the cult cafes Babylon XX, Doll, and the audience involved in the directed action acts as a staff (Slipchenko, 1996).

To this day, M. Yaremak’s gallery practices in art his- tory literature and mass media are mentioned with- out proper chronology and indication of the realized tasks, due to which their significance is diminished. “Window” Gallery (Image 2) (1991)—a space-room in the Gartenberg Passage—focused on commercial and promotional tasks. The place was popular in the imme-diate vicinity of the exhibition hall “Imprezi-91”, the cult cafe “Under the Chestnuts”.

Among the tasks of the cultural space S-object (June- December 1993, Bandera Street, 1) were: fixing the real estate of art in Ivano-Frankivsk through the quanti- tative filling of the gallery with new art artifacts and creating a communicative field to activate artistic and cultural processes in the city, acquainting the com- munity with new phenomena, establishing contacts with the new political elite. The space became a bright business card of the city, united wide cultural circles, launched a number of actions, such as art workshops, weekly club meetings, which were later adopted by art- ists from Lviv, Kyiv, and other cities of Ukraine. Among the well-known actions of S-object, there are a meeting with O. Zalyvakha, the editorial board of the magazine “Fine Arts”, public philosophical lectures by V. Eshkilev,T. Prokhask (P. S. abo Nʹyu-Vasyukivsʹkyy proekt, 1994,p. 10), the performances “Letters of a French officer” by T. Prokhask and O. Hnativa, “Shaving the skull with an electric razor Izdrik” by Yu. Izdrik (Babii et al., 2021,p. 131). A separate project, “ZaImpreza”, although formally included in Impreza-93, became an indepen- dent curatorial project that demonstrated alternative art: performance, video art. Among the invited authors’ projects we can mention “Thing and Nothing” by UtaKilter and Viktor Malyarenko (Odesa), “Marginal Cinema” by Volodymyr Gulich (Zaporizhzhya), Volodymyr Fedirko (Chernivtsi), the solo action “Obroshyn-Lviv” by Petro Starukh (Lviv). Namely here the Frankivsk part of the famous performance by Yu. Sokolov, O. Zamkovsky, andS. Horsky “Cross-Transplantation of Independence” (Lviv), the performance “Cocoon” by M. Yaremak, T. Prohaska accompanied by Polish cellist Tadeusz Wilecki (Image 3) took place.

Image 2: Gallery of M Yaremak Window Photo by Lubomyr Stasiv

The “S-Object” space (1997-2001, 5 Shashkevycha Street), despite the primacy of commercial purposes, assumed the tasks outlined by the previous spaces. Namely, the cultural practice of “framing”, which transformed a work of art—an artifact—into an object with a commercial purpose, a commodity. The gallery featured the first installation composition on the facade in Ivano-Frankivsk, which showed the already known “Objects”: “jewels made of cut metal a flag and a chair. The interior design should flow freely into the outdoor space of the street (city).

The place (‘it is here’) accen- tuated in this way simultaneously turned into a gesture of good will, an invitation to establish connectionsbetween society and art” (Melʹnyk, 2003). Among the ideological tasks set by the artist in this space were the cultural resistance of the capital, which attracted creative personalities; the study of new provincial regions, especially in the east, “providing opportunities for self-realization to those people who want to prove themselves something radical, to reveal themselves as ‘others’” (Yaremak, 1998). The gallery is known, among other things, for its representation of postmodern expositions like “Impreza-97”: the photo project ofI. Chichkan, “Sleeping Princes of Ukraine” (Kyiv); the installations of Yu. Izdrik. “Farewell to Fish” (Kalush), and M. Yaremak “Permanent Christmas” (Ivano- Frankivsk); O. Borisov’s program painting (Kharkiv) “Franco vs Franco” was also exhibited here.

Center for Contemporary Arts (CCA)’ initiatives Issues around the institutionalization of contemporary art have been raised by the Western Ukrainian art com- munity since the early 1990s. The idea of creating the first Museum of Contemporary Art in Ukraine belonged to the initiative of the Impreza Foundation.

Already in 1991, changes in the political system and the economic crisis revealed the impossibility of the International Biennale of Contemporary Art in Ivano- Frankivsk, as well as the “Renaissance” in Lviv as a phenomenon, but began their gradual transformation into a process and discourse to create an information environment. The channel of “flow” of information was conceived on the basis of Western European models: exhibitions, fairs, auctions, criticism, catalogs. In this situation, Impreza was to become a new institution capable not only of retransmission, but also of theo- retical analysis, and structuring of visual and verbal information.

Image 3: Cocoon performance Photo by Lubomyr Stasiv

Participants of the conference on contemporary art “Impreza-off-season” (Ivano-Frankivsk, March 29 - April 1, 1995) tried to theorize the problem of trans- forming the chaotic public initiative Impreza into a structured and funded state program that could ensure a register of events and their inclusion in cultural and artistic contexts. However, it is noted that the search for a communicative model is ineffective due to the process of “permanent changes of cabinets” (ScientificConference on Contemporary Art, 1995, p. 5), and one- time actions are not able to create a tradition.