DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.16922Published:

2021-12-12Issue:

Vol. 24 No. 1 (2022): January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesPerceptions on Adverbial Mobility in TESOL

A Survey of English Language Teachers in Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Percepciones acerca de la movilidad adverbial en la enseñanza del inglés para hablantes de otros idiomas

Keywords:

adverbios, movilidad adverbial, enfoque léxico, perspectivas de los profesores, TESOL (es).Keywords:

adverbs, adverbial mobility, lexical approach, teacher perspectives, TESOL (en).Downloads

References

Ahaotu, J. O. (2017). The impact of adverbial mobility on L2 English competence: A study on students of Emarid College, Port Harcourt. International Journal of Arts and Humanities, 6(4), 178-192. http://dx.doi.org/10/4314/ijah.v6i4.15

Ahaotu, J. O., & Ndimele, O.-m. (2008). Improving speech fluency through vocabulary development. Kiabara, 14(II), 195-201. https://www.uniport.edu.ng/publications/pub1/journals/faculty-of-humanities/kiabara.html

Akano, A., Olaniran, O., & Ukoyen, V. A. (2005). English language for senior secondary schools. Macmillan Publishers.

Chandler, J., & Stone, M. (2003). The resourceful English teacher. First Person Publishing.

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98-104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02310555 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

Egbe, G. B. (2015). ‘A’ approach to certificate English. Kraft Books.

Gass, S. M., & Selinker, L. (2001). Second language acquisition: An introductory course. (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbuam Associates. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410604651

Greenbaum, S., & Nelson, G. (2009). An introduction to English grammar (3rd ed.). Pearson Education.

Hammer, J. (2005). How to teach English. Longman.

Ibrahim, W. J. (2008). The characteristics of English linking adverbials. Journal of the College of Languages, 18, 8-23. https://www.bing.com/search?form=MOZLBR&pc=MOZI&q=The+characteristics+of+english+linking+adverbials

Krashen, S. D., & Terrell, T. D. (2000). The natural approach: Language acquisition in the classroom. Longman.

Lewis, M. (1993). The lexical approach: The state of ELT and the way forward. Language Teaching Publications.

Ndimele, O.-m. (2008). Morphology & syntax. M & J grand Orbit Communications.

Ndimele, O.-m. (2007). An advanced English grammar and usage. National Institute for Nigerian Languages.

Okoh, N. (1995). To use or to abuse: Words in English. Belpot.

Okoh, N. (2010). Marrying grammar and composition to open doors. Pearl Publishers.

Quansah, C., & Tetteh, U. S. (2017). An analysis of the use of adverbs and adverbial clauses in the sentences of junior high school pupils in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. British Journal of English Linguistics, 5(1), 44-57. http://www.eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/An-Analysis-of-the-Use-of-Adverbs-and-Adverbial-Clauses-in-the-Sentences-of-Junior-High-School-Pupils-in-the-Ashanti-Region-of-Ghana.pdf

Quirk, R., & Greenbaum, S. (2000). A university grammar of English. Addison Wesley Longman.

Racine, J. P. (2018). Lexical approach. In J. I. Liontas, & M. DelliCarpini (Eds). The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching (Volume II, pp. 1-7). Wiley Blackwell. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0169

Ramírez, A. T. (2012). The lexical approach: Collocability, fluency, and implications for teaching. Revista de lenguas para Fines Específicos, 18, 237-254. https://ojsspdc.ulpgc.es/ojs/index.php/LFE/article/view/44/43.

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s Alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 68, 1273-1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 30 de agosto de 2021; Aceptado: 25 de octubre de 2021

Resumen

Este estudio examinó las percepciones de los profesores de inglés sobre la movilidad adverbial con el fin de determinar hasta qué punto sería preciso afirmar que los adverbios son móviles. El investigador adoptó el Enfoque Lexical, una alternativa a las metodologías tradicionales de enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras basadas en gramática, como marco para el estudio. La confiabilidad del estudio fue demostrado por un valor del alfa de Cronbach de 0,83. El enfoque del estudio fue casi científico, ya que el investigador administró un cuestionario a 50 encuestados que son todos profesores de inglés en Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Los datos obtenidos fueron analizados utilizando el Coeficiente de Correlación de Rango de Spearman. El resumen de las respuestas contrasta la percepción más general de los adverbios y los grupos adverbiales como una categoría altamente móvil que puede colocarse en cualquier posición de la oración sin alterar el significado. Basándose en la opinión de la mayoría de los encuestados en el estudio, el investigador concluyó que percibían los adverbios como restrictivamente móviles y coincidió en que la movilidad presenta desafíos respecto al uso de adverbios por parte de sus estudiantes. El estudio recomendó, entre otras cosas, que los profesores de inglés en contextos TESOL incorporaran el Enfoque Lexical en la enseñanza de adverbios y habilidades de comunicación porque la metodología mejora la fluidez oral y escrita, así como la gramaticalidad.

Palabras clave

adverbios, movilidad adverbial, enfoque léxico, perspectivas de los profesores, TESOL.Abstract

This study examined the perceptions of teachers of English on adverbial mobility in order to determine how far it would be accurate to claim that adverbs are mobile. The researcher adopted the Lexical Approach, an alternative to traditional grammar-based foreign language teaching methodologies, as the framework for the study. The reliability of the study was demonstrated with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0,83. The study approach was quasi-scientific, as the researcher administered a questionnaire on 50 respondents who are all English language teachers in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. The data obtained were analyzed using Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient. The summary of the responses contrasts the more general perception of adverbs and adverbial groups as a highly mobile category that may be put in any sentential positions without altering meaning. Based on the opinion of a majority of the respondents in the study, the researcher concluded that they perceived adverbs as restrictively mobile and agreed that mobility presents challenges to their students’ use of adverbs. The study recommended, among other things, that teachers of English in TESOL contexts should incorporate the Lexical Approach in teaching adverbs and communication skills because the methodology enhances oral and written fluency as well as grammaticality.

Keywords

adverbs, adverbial mobility, lexical approach, teacher perspectives, TESOL.Introduction

The perception of concepts is an essential factor in teacher competence that affects the learning outcome of students. Teachers require a clear perception of concepts (such as ordering adjectives in a string and the mobility of adverbs) in order to effectively communicate teaching points and related ideas. Adverbial mobility is one of the teaching points addressed in lessons on the adverb word class (Ahaotu, 2017). Modification is the primary function of the adverbial category, and it shares this function with other categories such as adjectives and quantifiers. However, the categories modified by adverbs vary significantly from those modified by both quantifiers and adjectives. Generally, word level categories in English exhibit varying degrees of inter-category mobility: they may function as different word classes in diverse contexts. Nevertheless, the term ‘mobility’ of adverbs as used in this study refers to the capacity of adverbs to function from various positions in the same sentence. Such movements do not necessarily engender significant variations in the meaning of the sentence. Some examples are provided below with explanations of the impact of each adverbial movement into a new slot.

1. He only warned your son. (He did not do anything else to him).

2. Only he warned your son. (He carried out the action alone).

3. He warned your only son. (The addressee has one son).

Each movement of the adverb ‘only’ in the sentences above implied a semantic shift as explained in the parenthesis. In (1), (2), and (3) above, the adverb ‘only’ was moved into different positions among the rest of the same words. Examples (1), (2), and (3) are instances of expressions in which adverbial mobility leads to semantic shifts in utterance.

In other instances, adverbial mobility does not engender semantic changes in the sentence, as illustrated in examples (4) – (8) below.

4. I quickly crossed the road.

5. Quickly, I crossed the road.

6. I crossed the road quickly.

7. He warned your son only. (He did not warn anyone else).

8. He warned only your son. (He did not warn anyone else).

The adverbial property of mobility is quite often generalized in some grammar textbooks, some of which are commissioned. An example of this trivialization is found in revision-styled texts such as English language for senior secondary schools (Akano et al., 2005) in the Macmillan Mastering Series. This generalization tends to encourage the misplacement of adverbs because learners who misconstrue this learning point would eventually place adverbs in sentence slots that may produce awkward or ambiguous expressions. For instance, examples (4) – (6) above will produce awkward expressions if we place the same adverbs in the following sentence positions:

9.*I crossed quickly the road.

10. *I crossed the quickly road.

The two asterisked examples above are awkward and ungrammatical. Since all other categories maintained their slots, the placement of the adverb ‘quickly’ rendered the sentences awkward in comparison with the earlier positions in examples (4), (5), and (6).

Teacher competence in the appropriate methodology and teacher perceptions of teaching and learning concepts such as the mobility of adverbs produce a direct impact on learning outcomes. Against this background, this study seeks to investigate the perception of respondent teachers on the mobility of adverbs in teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL) based on the Lexical Approach. The choice of the Lexical Approach is an affirmation that, in TESOL, “a well-developed vocabulary is crucial in attaining communicative competence” (Ahaotu, 2008, p. 200).

The Lexical Approach to teaching

The Lexical Approach to the teaching of foreign languages holds that, when we make an utterance or create text, it could be understood by the analysis of the lexical units that were combined in the text. Lewis (1993) developed the Lexical Approach as a teaching methodology that focuses on words as the basic units of language. The approach proposes that the building blocks in language learning are lexis (words, word chunks formed from collocation, and, and multi-word phrases) rather than grammar and functions. According to the tenets of the Lexical Approach, analyzing and teaching language are based on the idea that language is made up of lexical units rather than grammatical structures. It is important to observe that the Lexical Approach is an applied linguistics model and does not undermine the teaching of grammar components, but rather emphasizes the teaching and learning of vocabulary because language is composed of grammaticalized lexis and not of lexicalized grammar (Lewis, 1993).

The Lexical Approach is a methodology for teaching foreign and second language. English is a second language in Nigeria, and it has undergone a significant degree of domestication. In view of the criticism that the Lexical Approach is neither a theory of language nor a theory of learning, Ramírez (2012) reported that Lewis himself has answered that the Lexical Approach is indeed, a development of the Communicative Approach to language teaching. Therefore, it focuses on developing learner proficiency with lexis and lexical chunks (words and word combinations); which are primary elements of language development (Racine 2018; Ramírez 2012). The Lexical Approach is relevant in this study for a number of reasons. First, it is a teaching methodology, and the respondents in the study are practicing teachers. The Lexical Approach also focuses on learning language and communication through lexis just as the adverb category is a word class. The methodology is appropriate on the grounds that the study focused on its primary domains of teaching, methodology, and lexis in TESOL.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The nature of adverbs

Adverbs are among the “open classes” of words (Greenbaum & Nelson 2009, p. 31), and many of the words used as adverbs are also used in other word classes, although often with some morphological variations. Quirk and Greenbaum (2000) stated the following:

There are two types of syntactic functions that characterize adverbs, but an adverb need have only one of these:

(1)adverbial

(2)modifier of adjective and adverb.

In both cases the adverb functions directly in an adverb phrase of which it is head or sole realization. Thus, in the adjective phrase far more easily intelligible, intelligible is modified by the adverb phrase far more and more is modified by the adverb phrase far, in this last case an adverb phrase with an adverb as sole realization. (pp. 125-126).

Quirk and Greenbaum (2000, p. 125) further observed that “the most common characteristic of the adverb is morphological: the majority of adverbs have a derivational suffix –ly”, a position that concurs with Ndimele’s (2008) view that most adverbs are morphologically marked by a – ly suffix. Adverbs share the common –ly ending morphological feature with adjectives, and this poses further challenges of both the identification and correct placement of such words. Examples of these are leisurely, daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly. The morphological addition of the –ly suffix is a common process of changing adjectives into adverbs, but a good number of adjectives also end with the same –ly suffix. Adjectives that end in – ic suffix change this to –ically when converted to adverbs. Instances of these transformations are illustrated with the following examples on Table 1:

Table 1: Forming adverbs from –ly and –ally suffixation of adjectives

S/N

Adjective

Suffix added

Adverb formed

1

Calm

–ly

Calmly

2

Glad

–ly

Gladly

3

Mad

–ly

Madly

4

Short

–ly

Shortly

5

Quiet

–ly

Quietly

6

Tight

–ly

Tightly

7

Frank

–ly

Frankly

8

Usual

–ly

Usually

9

Economic

–ally

Economically

10

Stoic

–ally

Stoically

11

Heroic

–ally

Heroically

12

Geographic

–ally

Geographically

In addition to this morphological feature, Ndimele (2007) observed that adverbs may also be formed in the following ways:

A. by adding the –ly suffix to verbs ending in –ing (grudgingly)

B. by adding the suffix –wise to nouns (lengthwise, clockwise)

C. by adding the suffix –wards to nouns

(Eastward(s), homeward(s))

D. by adding the suffix –wise to prepositions (inward(s), outward(s)

E. by adding the prefix a– to nouns (ahead, afield, aground)

F. by adding the prefix a– to verbs (astir, aloud)

G. by adding –er and –est to form comparative and superlative degrees of gradable adverbs such as: fast/faster/fastest; soon/sooner/soonest).

Adverbs may be compared, as is the case with adjectives, especially where gradability is involved (Ndimele, 2007; Quirk & Greenbaum, 2000; Okoh, 1995). Amplifiers and comparatives are available for adverbs of manner and time when they are expressed in terms of a scale. For instance, the adverb ‘lightly’ may take amplifiers and intensifiers such as: very lightly, quite lightly, more lightly, so lightly … (that), so lightly … (as to do something). Also, the adverb ‘likely’ may take similar categories to express a sense of scale such as in: very/most/less/not/more likely. Gradable adverbs (such as soon, fast, and near) usually add the –er suffix in the comparative and the –est suffix in the superlative forms, while several other adverbs adopt more/less and much/least to indicate the two forms. Examples of this are:

Absolute

Comparative

Superlative

Sincerely

more sincerely

most sincerely

Happily

more happily

most happily

Yet, there is a small group of non-gradable adverbs that do not permit comparison (yes, no, not, always, yet, etc.) and another group in which comparison is irregular (badly, well, far, etc.). Adverbs/adverbials are either integrated into a sentence or may operate at the periphery of the sentence. These are illustrated in examples (11a) – (11c) below:

11. (a) We boarded the train at exactly noon.

11. (b) Frankly speaking, he is an honest man.

11. (c) By God’s grace, I will improve my grades in English this semester.

It has been stated above that adverbs do not possess a monopoly of any morphological endings, as they share the common –ly, –ally, –er, and –est suffixes with adjectives, and it is equally important to state here that the presence of the suffixes discussed above does not guarantee that a word is an adverb (Egbe, 2015). The function performed by a given word in an utterance tends to be a more reliable method to determine whether or not it belongs to the adverb class.

Placing adverbs in appropriate positions

Quirk and Greenbaum (2000) identified four distinct sentential positions that adverbs may move into. These are the “Initial Position”, “Medial Position (1)”, “Medial Position (2)”, and “Final Position” (pp. 208-209). Ndimele (2007) noted that adverbs are difficult to classify, and that making generalizations about their position in sentences is challenging because they are not homogenous. However, he provided a framework of eleven syntactic positions of some adverbials based on certain observable regularities, and he illustrated these tentative statements with the following examples**:

I. Manner adverbials can be shifted into different positions without negatively affecting the grammatical correctness of the sentence.

12. The boy ate the food quickly.

13. The boy quickly ate the food. OR: Quickly, the boy ate the food.

However, he observed that the adverbial is better placed between the auxiliary and the main verbs in sentences with auxiliary verbs: The boy has quickly swallowed the drugs.

II. The mobility of some pre-verb adverbs is more restricted, and differences in meaning of utterances may occur with each movement.

14. The man has broken even the door.

15. The man has even broken the door. OR: Even the man has broken the door.

III. Locative (here, there) and definite time (today, yesterday, recently) adverbials can occupy initial and final positions.

16. Yesterday, Mary visited us. OR: Mary visited us yesterday.

17. His sister visited me recently. OR: Recently, his sister visited me.

IV. Most single-word indefinite time and manner adverbials can be found in sentence medial positions, that is, before the verb.

18. The nurses patiently assisted the patient.

19. The nurses finally assisted the patient.

V. In the order of adverbs, there is a tendency for adverbials of manner to precede those of place, while adverbials of place precede those of time:

MANNER-PLACE-TIME.

20. The car stopped suddenly outside the hotel.

21. Chelsea played rather well at the stadium today.

VI. If there are multiple auxiliary verbs in a sentence, it is normal for a pre-verb adverbial to follow the first auxiliary.

22. The man would never be seen at home.

23. *The man would be never seen at home.

VII. Manner adverbials can be placed immediately before or after the main the verb, regardless of the number of auxiliary verbs.

24. It ought to be slightly tilted. OR: It ought to be tilted slightly.

25. He ought to be carefully preserved. OR: He ought to be preserved carefully.

VIII. Pre-verb adverbials normally precede the modal auxiliary verbs ‘dare to’, ‘used to’, and ‘need to’.

26. She never dares to challenge me (*She dares to never challenge me).

27. They always need to come for prayers (*They need to always come for prayers).

IX. An adverbial usually follows the verb ‘(to) be’.

28. John is hardly seen at home (*John is seen hardly at home).

29. They were critically examined (*They critically were examined).

X. The auxiliary verb ‘(to) have’ normally precedes the adverbial

30. They have certainly done it

31. They certainly have to do it

XI. It is normal for indefinite time and manner adverbials to follow the contracted negative (n’t).

32. You can’t immediately begin to eat

33. You haven’t yet begun.

However, few adverbials (especially pre-verb ones) may precede the contracted negative as the following instances indicate:

34. He sometimes doesn’t behave himself

35. I still haven’t found the book you recommended.

**Adapted from Ndimele (2007, pp. 152158).

Some teaching points on adverbs

There are three classes of adverbials: adjuncts, disjuncts, and conjuncts.

A. Adjuncts perform the basic adverb function of modifying verbs, such as in the following examples:

36. You may now kiss the bride.

37. I really don’t understand why people betray their friends

38. She absolutely supports my candidacy.

B. The conjuncts’ connective function indicates the connection between two semantic units that co-occur in the same or proximate sentences, such as in the following examples:

39. He did not attend the meeting. I invited all of them, though.

40. If insecurity persists in Nigeria, then, many more young Nigerian professionals will emigrate to the Western world.

41. Many people criticized the administration, and yet they refused to register to vote for the opposition.

C. Disjuncts, though loosely connected to a sentence, provide an evaluation of it, such as in these examples:

42. Obviously, people do more reading presently than they ever did in the past.

43. Unfortunately, the government allowed insurgency to persist.

44. Frankly, they deserved more credit than they got for the discovery.

The adverbs in the illustrations above perform both modification and connective functions in the expressions. Adverbs are difficult to define, as “there is no homogeneity in the form of or position of all the words that are referred to as adverbs, i.e. they vary greatly both in their forms and position in a sentence” (Ndimele 2007, p. 148). Ibrahim (2008) also noted that there are many sub-classes and positional variations among adverbs and adverbials, and these make them more difficult to define than other words in the open category. Although some words function as both adjectives and adverbs, adverbs are generally distinct from adjectives. Adverbial modifiers cannot be used interchangeably with adjectival modifiers without producing ungrammatical expressions, as in the following examples from Ahaotu (2017, p.182).

45. (a) Fred bought a new wristwatch (adjective ‘new’ modifying noun wristwatch)

(b) *Fred bought a newly wristwatch.

46. (a) Our soldiers fought gallantly, (adverb ‘gallantly’ modifying verb “fought”)

(b) *Our soldiers fought gallant,

47. Our gallant soldiers defeated the enemy. (‘gallant’ adjective modifying noun ‘soldiers’)

The examples above illustrate forms of the same words used as adverbs and as adjectives. Adverbial modification is not limited to verbs but is rather extended to adjectives, other adverbs, and additional categories such as: prepositional phrases (PP), verb phrases (VP), and noun phrases (NP). Some examples of these are provided below:

48. He openly discussed our secret agreement with third parties. (verb)

49. She was certainly too old to have another baby. (adjective)

50. I would rather carefully read this agreement again before signing it. (adverb)

51. Chelsea is obviously on the lead this season. (PP)

52. Unfortunately, some countries fail to harness their resources for development. (clause)

53. He would rather not rely on oral evidence in such a sensitive case. (VP)

54. The accused probably did not get fair hearing on the case. (VP)

55. The labourers cut almost the whole field. (NP)

56. Very few houses on the street are new. (determinative)

In the illustrations above, modifying adverbs are italicized, while the modified categories are underlined. Hammer (2005, p. 44) summarized adverbial mobility when he posited that an adverb cannot occur between a verb and its object. He illustrated this position in the following sentences:

57. I usually have sandwiches for lunch.

58. *I have usually sandwiches for lunch.

Chandler and Stone (2003) suggested that a resourceful English teaching program should include a conscious recycling of lexis in other to place them within the learner’s active vocabulary. This view buttresses the Lexical Approach, since both are learner-centered and emphasize the learner’s vocabulary development as a crucial condition for language acquisition processes. Despite this emphasis, the study recognizes the inevitability of grammar in TESOL and the broad interface of grammar and vocabulary.

Rationale for the study

Adverbs are sometimes classified under the grammatical (or functional) category of words alongside prepositions, determiners/quantifiers, conjunctions, etc., in contrast with the lexical (or content) category of words such as nouns, verbs, etc. While major word classes receive ample treatment in course books, adverbs are often treated as a minor word class. Gass and Selinker (2001, p. 372) argued that “there has been much less attention paid to the lexicon than to other parts of the language, although this picture is quickly changing”. Quansah and Tetteh (2017, p. 45) paraphrased Nordquist’s (2011) description of the word ‘classes’ as “a means of fostering precision and exploiting the richness of expressions in the English language” and acknowledgment of the efforts made by teachers at the secondary level of education to promote this. These views call for studies such as this one.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this study is to determine the perceptions of English teachers on adverbial mobility in TESOL. Its objectives include:

(i) To establish the opinion of teachers on the teaching resources available to them on adverbs;

(ii) To determine the effects of adverbial mobility on teaching/learning in TESOL.

Significance of the study

This study is a quasi-scientific application of reflective practice in analytically examining a problem in applied linguistics and exploring action plans for its possible improvement. The respondents reflect on various aspects of their practice (such as peer observation, learner assessment, self-assessment, material design, teaching resources, etc.) as they fill out the questionnaire. The study is therefore significant in both the promotion of professional development of the English language teacher respondents and in the provision of a pedagogical tool for applied linguistics of English in general and TESOL in particular.

Limitations

A significant limitation of this study is the limited sample of only urban Nigerian teachers and its inability to cover a wider scope. TESOL goes on in a great diversity of places, and so, the result of a study such as this one may indeed vary significantly depending on a number of variables including coverage. The researcher therefore acknowledges that the findings and conclusion of this study may not be the same for other teaching contexts.

Research questions

The three research questions that guided this study are:

1. To what degree are adverbs mobile?

2. Does adverbial mobility pose a challenge to teachers/learners in TESOL?

3. Do teachers and course books adequately address adverbial mobility in TESOL in Nigeria?

Hypotheses

This research was guided by the following null hypotheses in the validation and evaluation of its data:

(1) Adverbial mobility is not patterned.

(2) Learners of English in TESOL situations have no difficulties in the use of adverbs.

(3) Course books on applied linguistics of English in Nigeria do not contribute to learner difficulties in adverbial positioning.

Methodology of study

The study was first tested for validity using Cronbach’s alpha (1951), which Cortina (1993, p.98) has described as “one of the most important and pervasive statistics in research involving test construction and use”. The alpha was applied to fifteen (15) English teachers who responded to ten (10) questions as presented in Table 2 below:

The acceptable alpha in this study adopted Taber’s (2018) report on 69 articles published in four science education journals in 2015. Taber (2018, n. p.) found that the authors generally did as follows:

alpha values were described as excellent (0,930,94), strong (0,91-0,93), reliable (0,84-0.90), robust (0,81), fairly high (0,76-0.95), high (0,730,95), good (0,71-0.91), relatively high (0,700,77), slightly low (0,68), reasonable (0,67-0,87), adequate (0,64-0.85), moderate (0,61-0.65), satisfactory (0,58-0,97), acceptable (0,45-0.98), sufficient (0,45-0,96), not satisfactory (0,4-0,55), and low (0.11).

As illustrated by Table 2 above, Cronbach’s validity was determined to be 0,83, an acceptable value that validates the result of the study.

Table 2: Result of Cronbach’s alpha validity test with 15 teachers

S/N

ID

SA

A

SD

D

4*SA

3*A

2*D

1*SD

1

Q1

2

3

5

5

15

8

9

10

5

32

2

Q2

1

2

3

9

15

4

6

6

9

25

3

Q3

2

2

4

7

15

8

6

8

7

29

4

Q4

2

1

4

8

15

8

3

8

8

27

5

Q5

5

1

4

5

15

20

3

8

5

36

6

Q6

1

3

5

6

15

4

9

10

6

29

7

Q7

1

2

3

9

15

4

6

6

9

25

8

Q8

2

5

3

5

15

8

15

6

5

34

9

Q9

4

1

5

5

15

16

3

10

5

34

10

Q10

5

3

3

4

15

20

9

6

4

39

2,5

1,566667

0,766667

3,344444

40

14,1

3,066667

3,344444

22,66667

60,51111

1.333333

Variance

22,66667

Sum Var

60,51111

Cronbach

0,833676

0,83

The data for this study were collated with a questionnaire that was administered to fifty English language teachers in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. The instrument was administered during an English language teaching (ELT) event and collected on the spot. The respondents comprise thirty females and twenty males, all of whom teach at the secondary level of education. The study adopted a modified random sampling, where one half of the 50 respondents were chosen from public schools, while the other half were chosen from private schools. The items on the questionnaire are designed to elicit information about each respondent’s experience, views on the subject, and observations of learner-competence or otherwise in handling adverbial mobility. The responses to the items on the questionnaire were collated and rated on a four-point Likert scale with the following options:

Strongly Agree (SA)

Agree (A)

Disagree (DA)

Strongly Disagree (SD)

The data were analyzed with tables and Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient (SRCC), an advancement of Pearson’s formula derived from the Pearson Product-Moment Coefficient. Although SRCC was originally designed as a marketing evaluation tool, it was adopted for this study because it is a reliable statistical tool in measuring qualitative variables such as the opinions of in-service teachers of English on the adverb category.

RESEARCH PRESENTATION

Data presentation

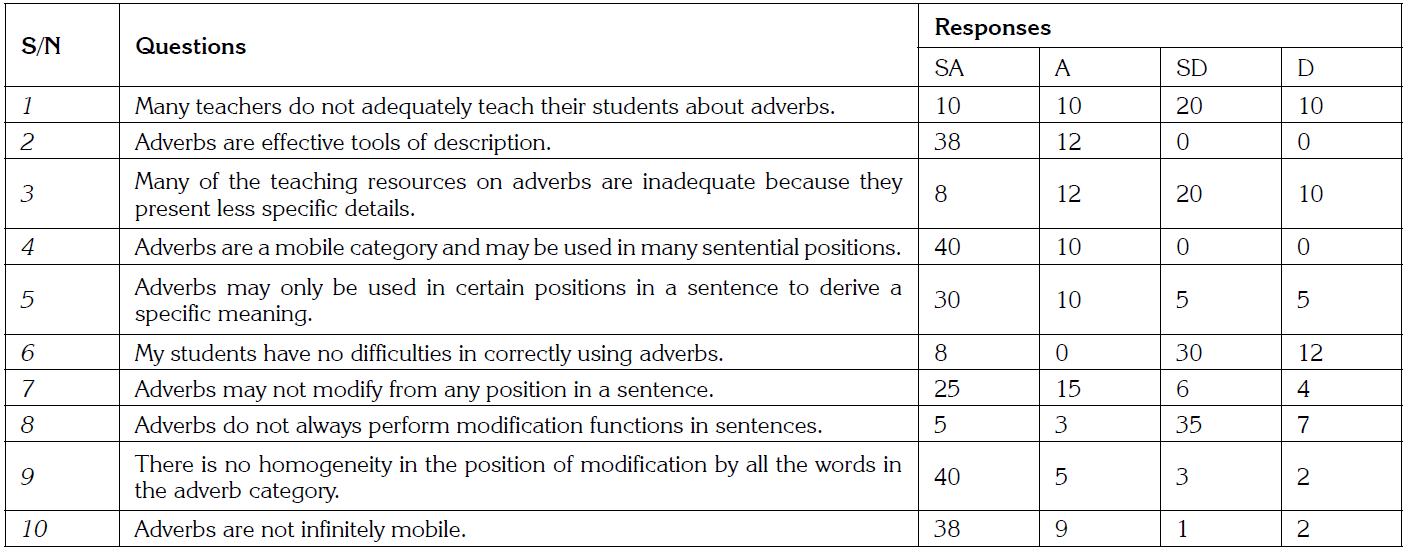

In this study, the respondents are representative of in-service English language teachers in TESOL contexts. The questionnaire administered to the respondents consists of ten questions, and a summary of their responses to these questions is presented in Table 3, which shows both the questions and the raw data of the study.

Data analysis

On the one hand, responses that ‘Strongly Agree’ and those that ‘Agree’ (SA and A) are collectively grouped together as the ‘X-Variable’. On the other hand, responses that ‘Strongly Disagree’ and those that ‘Disagree’ (SD and D) are grouped together as the ‘Y-Variable’. The researcher analyzed the data following this principle to enable the effective ranking of the variables, as presented in Table 4 below.

Table 3: Study questions and raw data collated on teacher perceptions on adverbial mobility

Table 4: Conversion of the raw data into X and YVariables

S/N

X-Variable

Y-Variable

1

20

30

2

50

0

3

20

30

4

50

0

5

40

10

6

8

42

7

40

10

8

8

42

9

45

5

10

47

3

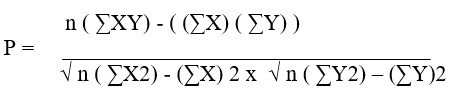

The data analysis was based on Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient (SRCC). According to SRCC, variables may be ranked without allotting specific grades to them, especially if they are qualitative variables such as opinion, beauty, and taste. We may describe SRCC as a statistical tool that measures the degree of association between two variables, X and Y, and apply the following formula in calculating it:

The symbols in the formula are used in place of the following meanings

X = Summation of ‘Agree’ and ‘Strongly Agree’ Variables

Y = Summation of ‘Disagree’ and ‘Strongly Disagree’ Variables

P = Pearson’s Product Moment Coefficient n = number of values in the data ∑ = summation of.

The raw data collated were converted into the values represented in the above formula and are presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Conversion of raw scores into formulaic values

S/N

X

Y

XY

X

2

Y

2

1

20

30

600

400

900

2

50

0

0

2500

0

3

20

30

600

400

900

4

50

0

0

2500

0

5

40

10

400

1600

100

6

8

42

336

64

1764

7

40

10

400

1600

100

8

8

42

336

64

1764

9

45

5

225

2025

25

10

47

3

141

2209

9

Total

328

172

2702

11762

1798

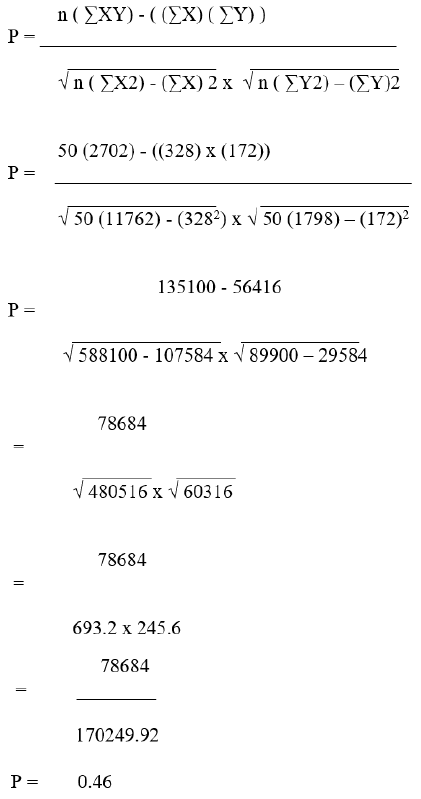

Furthermore, these values were substituted for the symbols in the formula and were decomposed as follows:

Data interpretation

The basis of this analysis is that the degree of mutual association of the variables X (‘Agree’) and ‘Y’ (‘Disagree’) are measurable with the correlation coefficient. Three principles of interpretation determine the result accepted for the analysis:

1. A result value (or Pearson coefficient) of -1 would indicate a perfect negative correlation, whereas Pearson coefficient of 1 would indicate a perfect positive correlation between variables X and Y. In this study, a Pearson coefficient of -1 would mean that the respondents perfectly disagree, while a Pearson coefficient of 1 would mean that the respondents perfectly agree with the propositions of the study.

2. A positive correlation means that the values of both variables X and Y either rise or fall simultaneously, while a negative correlation means that there is inverse relationship between both values such that an increase in the value of one engenders a decrease in the value of the other.

3. A correlation coefficient of 0 would imply the absence of any linear association between both variables.

Based on these principles of interpretation, the result of 0,46 obtained from the application of the correlation coefficient indicated average non-perfect agreement of the respondents on the issues raised about adverbs in the study. This may be deduced from the fact that the correlation coefficient of 0,46 may be approximated to 0,5, a half-way movement towards the perfect agreement value of 1.

Discussion and summary of findings

The highest agreement indices of 100% in the study were obtained from the responses to items 2 and 4 on the questionnaire, which conversely provided the lowest level of disagreement (0%). In response to item 2 on the questionnaire (adverbs are effective tools of description) the respondents unanimously agreed that the use of adverbs enhances description. This implies that L2 learners of English would achieve greater competence in the language if they effectively use adverbs.

The respondents also unanimously agreed on item 4 of the questionnaire (adverbs are a mobile category and may be used in any sentential position) to the effect that their perception of adverbial mobility is a generalized concept rather than a restricted one. The researcher found that the perception is an approximate definition of the adverb category in some

of the course books on Ordinary Level English which the respondents use. Item 3 fn the questionnaire focused on the quality of resource materials on the subject. In response to the statement presented by the item (many of the teaching resources on adverbs are inadequate because they present less specific details), 20 respondents, representing 40% of the sample population, agreed that the resources are inadequate, while the remaining 30 respondents (60%) disagreed with the statement. One can deduce from these responses that there is a significant level of superficial treatment of the subject in course books and that the respondents tend to grossly simplify the nature of adverbs, which results in partial conceptions about this word class.

The lowest level of agreement in the study was obtained from the responses to items 6 and 8 (my students have no difficulties in correctly using adverbs; adverbs do not always perform modification functions in sentences.); eight respondents (16%) disagreed to each item. Conversely, these two items of the questionnaire (6 and 8) provided the highest levels of disagreement in the study. The remaining 42 respondents (84% of respondents) respectively indicated both that their students have difficulties in correctly placing adverbs and that adverbs perform important modification functions in sentences. Therefore, the respondents hold the view that adverbs aid proficiency, but that their students find it difficult to correctly use them.

Five items, representing 50% of the questionnaire items in the study, focused on eliciting information about teacher perceptions of adverbial mobility from the respondents. These are items number 4, 5, 7, 9, and 10. Item number 4 demands a non-specific response, and the data obtained with it has been interpreted earlier in this section. The remaining four items required specific information about teacher perceptions of adverbial mobility from the respondents, and the data retrieved on them are presented in Table 6.

The data obtained with these items indicate a high level of teacher opinion in favor of the patterned mobility of adverbs. Both items 5 and 7 elicited an 80 percentile agreement from the teachers in support of the views that ‘adverbs may only be used in certain positions in a sentence to derive a specific meaning’ and ‘adverbs may not modify from any position in a sentence’. A higher degree of agreement (90% of the respondents) was recorded for item 9 in support of the statement that ‘there is no homogeneity in the position of modification by all the words in the adverb category’, while the highest level of agreement (94%) was achieved in the response to item 10, ‘adverbs are not infinitely mobile’. This cluster of items elicited details of the various aspects of teacher opinions about adverbial mobility. The result indicated that the teachers of English who responded to the questionnaire items tended to agree that adverbial mobility is significantly ordered and restrictive, rather than chaotic and completely random.

Test of hypotheses and research questions

Table 6: Summary of items that elicited information about teacher perceptions of adverbial mobility

Item Number

Statement

X

Y

5

Adverbs may only be used in certain positions in a sentence to derive a specific meaning.

40

10

7

Adverbs may not modify from any position in a sentence.

40

10

9

There is no homogeneity in the position of modification by all the words in the adverb category.

45

5

10

Adverbs are not infinitely mobile.

47

3

Total

172

28

The three null hypotheses that guided the study were tested to provide validity for the research. Hypotheses 1 (adverbial mobility is not patterned) was tested and disproved by the responses to study questions 5, 7, 8, 9, and 10 (Table 5). The summary of their finding is that adverbial mobility is patterned. Therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected and its alternative is accepted: adverbial mobility is patterned and guided by some observable characteristics of the sub-categories of the adverbs in question.

This finding also answers Research Question 1 (to what degree are adverbs mobile?) Specifically, questionnaire items 4, 5, 7, 8, and 10 elicited the responses that answered Research Question 1, as demonstrated in Table 7.

These responses demonstrate that adverbs are not randomly mobile, but rather restrictively so.

Hypothesis 2 (learners of English in TESOL situations have no difficulties in the use of adverbs) was tested and disproved by the responses to study questions 1 and 6 on Table 5. The summary of the responses indicates the view of the respondents that many of their professional colleagues do not adequately teach the topic, while learners generally have difficulties in correctly placing adverbs. As a result, null Hypothesis 2 was rejected, and its alternative is accepted: both teachers and learners have difficulties in handling adverbial mobility.

This finding also answers Research Question 2 (does adverbial mobility pose a challenge to teachers/ learners in TESOL?) Specifically, questionnaire items 2, 4, 6, and 9 were used to elicit the responses that answered Research Question 2, as demonstrated in Table 8.

The above demonstrated that adverbs are an important word class that aids description, but that their mobility poses a challenge to effective teaching and learning of L2 English.

Table 7: Responses that answer Research Question 1

S/N

Questions

Responses

SA

A

SD

D

4

Adverbs are a mobile category and may be used in many sentential positions.

40

10

0

0

5

Adverbs may only be used in certain positions in a sentence to derive a specific meaning.

30

10

5

5

7

Adverbs may not modify from any position in a sentence.

25

15

6

4

8

Adverbs do not always perform modification functions in sentences.

5

3

35

7

10

Adverbs are not infinitely mobile.

38

9

1

2

Table 8: Responses that provided an answer to Research Question 2

S/N

Questions

Responses

SA

A

SD

D

2

Adverbs are effective tools of description.

38

12

0

0

4

Adverbs are a mobile category and may be used in many sentential positions.

40

10

0

0

6

My students have no difficulties in correctly using adverbs.

8

0

30

12

9

There is no homogeneity in the position of modification by all the words in the adverb category.

40

5

3

2

Hypothesis 3 (course books on applied linguistics of English in Nigeria do not contribute to learner difficulties in adverbial positioning) was tested and disproved by the responses to study question 3 on Table 6. The summary of the responses indicated that many of the respondents were dissatisfied with course book content on the subject. Based on this perception, null Hypothesis 3 was also rejected, and its alternative was accepted: poor course book content contributes to the challenges that both teachers and their learners experience in handling adverbial mobility.

This finding also answers Research Question 3 (do teachers and course books adequately address adverbial mobility in TESOL in Nigeria?). Questionnaire items 1 and 3 specifically elicited the responses that answered Research Question 1 (Table 9).

The above result answered Research Question 3 in the negative: teachers and course books have not adequately addressed issues of mobility of adverbs.

Conclusion

Overall, adverbs belong to the open group of word classes (Okoh, 2010; Quirk & Greenbaum, 2000) and therefore represent a large repertoire of lexeme that could be taught and learned in TESOL contexts. This study attempted to demonstrate the important role that the Lexical Approach, as well as the inevitable link between grammar and vocabulary, could play in the process. The respondents’ views affirm that adverbs offer essential building blocks for language learning and communicative competence in ESL and EFL. Adverbial sub-categories, such as adverbs, adverbial collocation, phrases, and clauses present a reservoir of lexeme for teaching, classroom activities, and testing English language and communication skills, especially where the teaching objective is to improve fluency or to acquire descriptive skills. The violation of adverbial positioning leads to awkward expressions and ambiguity. Therefore, English teachers under the circumstances of this study perceive adverbial mobility as limited, and they agree that their students experience difficulties in correctly placing adverbs.

Regrettably, the respondents are not satisfied with the contents of some of the course books on the subject.

Recommendations

Based on the findings and conclusions drawn above, the researcher has made the following recommendations on the subject:

1. English teachers should experiment with methodologies and adopt any combinations that work for them and their learners in the teaching and learning of adverbs. For instance, although the Lexical Approach was explored and recommended as suitable for teaching adverbs and word classes in this study, it would be positively complemented by Communicative Language Teaching (CLT, also known as the Communicative Approach), which is learner-centered and relies on classroom activities. Adapting aspects of methodologies often introduces freshness and variety that may enhance learning outcomes.

2. English teachers should also improvise and design materials that they require for the effective teaching of adverbs to augment the content of the course books. This would enhance the content and learning outcome of lessons on topics such as adverbs, where course book content is inadequate.

3. Relevant professional associations in Nigeria should actively participate in the production, review, and approval of course books for Nigerian schools. These organizations include the English Language Teachers Association of Nigeria (ELTAN), the Linguistics Association of Nigeria (LAN), and the Reading Association of Nigeria (RAN). The membership of these professional bodies includes accomplished and early career teachers of English language and literature. If members of such associations put their joint teaching and examining experiences into commissioned books, the product would most likely avoid the weaknesses in current course books that are authored by individuals and commercial outfits.

Table 9: Responses that provided an answer to Research Question 3

S/N

Questions

Responses

SA

A

SD

D

1

Many teachers do not adequately teach their students about adverbs.

10

10

20

10

3

Many of the teaching resources on adverbs are inadequate because they present less specific details.

8

12

20

10

4. TESOL practitioners should incorporate the Lexical Approach in teaching classes and communication skills because the methodology enhances the vocabulary development required for oral and written fluency, and it also has a capacity for developing grammaticality. According to Krashen and Terrell (2000), vocabulary and grammaticality are both naturally acquired in the first language (L1), and this model also works in TESOL contexts.

References

Metrics

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Joseph Onyema Ahaotu

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.