DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.12383Publicado:

2018-02-16Número:

Vol 20, No 1 (2018) January-JuneSección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónUsing metacognitive strategies to raise awareness of stress and intonation

Usando estrategias metacognitivas para elevar la conciencia del acento y la entonación en la enseñanza de inglés

Palabras clave:

inteligibilidad, entonación, conciencia lingüística, estrategias de aprendizaje, suprasegemental, acento (es).Palabras clave:

Intelligibility, intonation, language awareness, learning strategies, suprasegmental, stress (en).Referencias

Arévalo, J. (2007). Improving Pronunciation Skills through Self-Recordings. (Master’s dissertation). Retrieved from http://intellectum.unisabana.edu.co/bitstream/handle/10818/12397/Jessica%20Milena%20Mancera%20Ar%C3%A9valo%20%28tesis%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Bradford, B. (1988). Intonation in context.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Camargo, A., & Hederich, H. (2010). La relación lenguaje y conocimiento y su aplicación al aprendizaje escolar. Revista Folios. 5(31), 105-122.

Camelo, M. (2010). Using metacognitive processes to improve students’ writing quality. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal. 12(1), 54-69.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2005). From Babel to Pentecost: Postmodern Glottoscapes and the Globalization of English. In L. Anglada, M. Barrios, & J. Williams (Eds.), Towards the Knowledge Society: Making EFL Education Relevant (pp. 22-35). Córdoba, Argentina: Comunic-arte Editorial.

Chamot, Barnhardt, El-Dinary, & Robbins (1999). The learning strategies handbook.Pearson. White Plains, NY.

Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. (2008).Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory: procedures and techniques. Sage Publications, Inc. 3rd edition.

Crystal, D. (1975). Intonation and linguistic theory.In K.H. Dahlstedt (ed.), The Nordic languages and modern linguistics 2.Stockholm: Almqvist&Wiksell.

Crystal, D. (2004). The past, present and future of world English.In Andreas Gardt& Bernd Hüppauf (eds), Globalization and the futureof German. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Diaz, I. (2015). Training in metacognitive strategies for students’ vocabulary improvement by using learning journals. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 17(1), 87-102.

Dweck, C. S. (2000). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Field, J. (2005). Intelligibility and the listener: the role of lexical stress. TESOL Quarterly, Vol. 39, 3 (Sep., 2005), 399-423

Florez, Torrado, Mondragon & Perez.(2005). Habilidades metalingüísticas, operaciones metacognitivas y su relación con los niveles de competencia en lectura y escritura: un estudio exploratorio. FORMA Y FUNCIÓN 18 (2005), p. 15-44. Bogotá, D.C, Departamento de Lingüística, Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Frodden, C and Mc. Nully, M. (2011) A New Look at Suprasegmentals. Ikala, No. 1 (2011). Bogotá. Retrieved from:

http://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/ikala/article/viewArticle/8037

Graddol, D. (2006). English next.London: British council.

Hahn, L. D. (2004). Primary Stress and Intelligibility: Research to Motivate the Teaching of Suprasegmentals. TESOL Quarterly, No. 2 (Summer, 2004), Vol. 38 (No. 2 (Summer, 2004)), pp. 201-223.

Jenkins, J. (2000). The phonology of English as an international language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jin, J. (2011). An Evaluation of the Role of Consciousnessin Second Language Learning. International Journal of English Linguistics Vol. 1, No. 1; March 2011. Guangdong, China.

Kennedy, S. &Trofimovich, P. (2010).Language awareness and second language pronunciation: a classroom study. Montreal: Rougledge.

Kenworthy, J. (1987). Teaching English Pronunciation. London: Longman.

Lier, L. (1996). Interaction in the Language Curriculum: Awareness, Autonomy, and Authenticity. London and New York: Taylor & Francis.

Mills, G. (2003) Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher. Merrill Prentice Hall.

Orrego & Monsalve, 2010. Empleo de estrategias de aprendizajede lenguas extranjeras: inglés y francés. Íkala, revista de lenguaje y cultura. Vol. 15, N.º 24 (enero-abril de 2010). Bogota, Universidad Distrital Francisco Jose de Caldas.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language Learning strategies. What every teacher should know. Boston, Massachusetts: Heinle&Heinle Publishers.

Quintero, A. Leon, A. and Pino, M. (2011). Conciencia fonológica y su relación con las dificultades de lectura. Cultura, Educación, Sociedad – CES. 2(1), 25- 34.

Richards, J. (2008). Moving Beyond the Plateau. From Intermediate to Advanced Levels in

Language Learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ridley, S. et al. (1992).Self-Regulated Learning: The Interactive Influence of Metacognitive Awareness and GoalSetting.In The Journal of Experimental Education, Vol. 60, No. 4.

Rodriguez, E. (2007). Self-assessment Practices: An empowering Tool in the teaching and learning EFL Processes. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal. 9. September 2007, 229-246.

Smith, L. (1992). Spread of English and issues of Intelligibility. In B. B. Kachru (Eds.) The

Other Tongue. 75-90.

Svalberg, A. (2012). Language awareness in language learning and teaching: A research agenda. Language Teaching, 45(3), 376-388.

Takimoto, M. (2008). The Effects of Deductive and Inductive Instruction on the Development of Language Learners' Pragmatic Competence.The Modern Language Journal, Vol. 92 (3 (Fall, 2008)), pp. 369-386.

Uribe, O. (2012). Helping business English learners improve discussion skills. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal. 12(2), 127-145.

Ushioda, E. & Do¨rnyei, Z. (Eds.). (2009). Motivation, Language Identities and the L2 Self: A Theoretical Overview. Bristol, U.K., Multilingual Matters

Venkatagiri, H. L. (2007). Phonological Awareness and Speech Comprehensibility: An Exploratory Study.Language Awareness, 16 (4), 263-277.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13-39). San Diego: Academic Press.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Using Metacognitive Strategies to Raise Awareness of Stress and Intonation in EFL

Usando estrategias metacognitivas para elevar la conciencia del acento y la entonación en la enseñanza de inglés

Diana Peñuela1

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Peñuela, D. (2018). Using Metacognitive Strategies to Raise Awareness of Stress and Intonation in EFL. Colomb. appl. linguist. j., 20(1), pp. 91-104.

Received: 16-Jul.-2017 / Accepted: 14-Jan.-2017

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.12383

Abstract

Few studies have analyzed the impact of language awareness and metacognitive strategies for intelligibility in the context of English as an international language. This qualitative action research study examined the impact of using three metacognitive strategies—overviewing, goal setting, and self-evaluating—to raise adult learners’ awareness of stress and intonation at a private language center in Bogotá. Ten participants enrolled in an advanced English course showed lack of awareness of the use of suprasegmentals (stress or intonation) to communicate intelligibly in a preliminary oral interview. The implementation took three cycles each lasting one hour every day for two weeks. During the first week, the participants were trained to use one metacognitive strategy. During the second week, they identified a suprasegmental feature from video or audio input. Finally, they monitored the use of the feature through the strategy they had learned in the first week. Data were collected via learning logs, recorded artifacts, and field notes. The results showed that students raised awareness in a triadic process that involves metalinguistic, learning, and self-awareness. Results may be useful to revisit the current teaching of pronunciation and to provide insights about the use of elements from the lingua franca core in the Colombian context.

Keywords: intelligibility, intonation, language awareness, learning strategies, suprasegmental, stress

Resumen

Pocos estudios han analizado el impacto de la conciencia del lenguaje y las estrategias metacognitivas en el contexto del inglés como lengua extranjera. Este estudio cualitativo de investigación acción examinó el impacto de tres estrategias metacognitivas en el reconocimiento y uso de aspectos suprasegmentales como la entonación y el acento en un grupo de 10 participantes, estudiantes de nivel avanzado de inglés en una academia privada. En entrevista preliminar, mostraron desconocimiento del rol comunicativo de los suprasegmentales. Posteriormente se entrenaron en el uso de una estrategia metacognitiva y un aspecto suprasegmental en cada uno de tres ciclos de implementación. Los instrumentos de recolección de datos fueron diarios, grabaciones, y notas de campo de la profesora. Los resultados mostraron que los participantes tomaron conciencia en un proceso triádico que incluyó: un conocimiento metalingüístico, la toma de conciencia de su aprendizaje y la conciencia de sus capacidades. Los resultados del estudio sugieren una revisión de la enseñanza actual de la pronunciación un análisis sobre la implementación del paradigma del inglés como lengua franca en el contexto colombiano.

Palabras clave: inteligibilidad, entonación, conciencia lingüística, estrategias de aprendizaje, suprasegemental, acento

Introduction

Advanced learners of English as a foreign language (EFL) face enormous challenges in the pursuit of fluency. Richards (2008) states that one of the problems they encounter is that even though their language production may be adequate, it often lacks the characteristics of intelligible speech. Although the term intelligibility has been widely discussed by scholars throughout the last decade, Jenkins (2000) provides the most appropriate definition for the context of this research study. According to her, intelligibility refers to the phonological features necessary for communication among speakers of English as an international language.

To speak intelligibly, advanced EFL learners need to use a variety of phonological elements. However, once learners can make themselves understood through other linguistic features such as grammar and vocabulary, they appear to disregard how phonological elements help them convey messages more naturally and effectively. Therefore, it seems that learners need to raise awareness of both why and how phonological aspects are used in effective yet spontaneous communication. This paper analyzed the extent to which the use of three metacognitive learning strategies—overviewing, goal setting, and self-evaluating—may help students raise awareness of their stress and intonation in English.

The study was carried out at a private language center in Bogotá, Colombia which offers English courses through three programs to children, teenagers, and adults. The implementation took place in the adult English program (AEP) in which learners are classified according to their language level into three blocks: basic, skills (intermediate), and challenge (advanced).The AEP presents the skills learners are expected to have developed before starting advanced courses at the center on a document based on the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR; Council of Europe, 2011), which states that learners should be able to use correct intonation and stress patterns for different circumstances. However, the needs analysis procedure carried out for this research study evidenced students’ difficulty in using these phonological patterns. Most students seemed to struggle to stress relevant information in their speech, or to express ideas in thought groups. Instead, they used linear speech and communicated word by word, which complicated the listener’s understanding.

This problem might have occurred due to the influence of the institutional curriculum which focuses on accuracy and interaction, rather than training in phonology. In fact, results of the survey designed for the needs analysis procedure suggested that most learners in an advanced course considered accuracy, vocabulary, and pronunciation of English sounds to be important aspects when they speak. None of the participants considered intonation or stress to be important. Nevertheless, most participants acknowledged having received instruction in stress and intonation, but the questionnaire revealed that they did not use them spontaneously. This suggests that the type of instruction they received in regard to suprasegmentals might have been ineffective. It may also confirm what Kennedy and Trofimovich (2010) found in their study: that lack of awareness relates directly to poor use of linguistic elements. Therefore, raising students’ awareness of the use of suprasegmental features might help learners improve their usage and in the long term, reach the standards envisaged in the CEFR, as the AEP expects them to do.

Theoretical framework

This study considered seminal and contemporary theories to explain the concept of language awareness, metacognitive strategies, and intelligible stress and intonation. These constructs provide solid support for the research settings.

92

Intelligible Stress and Intonation

The concept of intelligibility has been widely debated by language teachers and researchers. Kenworthy (1987) sees intelligibility as being understood by a listener at a given time in each situation. This may suggest that understanding every word a speaker produces guarantees understanding the message he intends to convey. Later, Smith (1992) defined intelligibility as the ability to make one’s words and utterances recognized by others thanks to the appropriate production of its sounds. However, this definition seemed insufficient in the context of this study given that the learners’ words and utterances were generally well pronounced and therefore recognized by others, yet their messages were not clearly conveyed; they were not entirely intelligible.

Both Kenworthy (1987) and Smith (1992) regarded intelligibility as a one-way process in which non-native speakers struggled to make themselves understood by native speakers through English sounds. However, more recently, authors such as Jenkins (2000), Crystal (2004), or Graddol (2006) have questioned the extent to which this language is spoken by native or non-native speakers. Crystal (2004) states that the ratio of native to non-native speakers of English is around 1:3, which has changed the panorama of the phonological field. Because of the considerable number of non-native speakers of English around the world, the standard sounds and patterns of English have changed. Consequently, speakers no longer need to sound native-like to be considered as intelligible.

In the new panorama in which English is an international language (EIL), Jenkins (2000) has studied intelligibility as a two-way process involving both the speaker and listener in the production and recognition of phonological form. This definition implies that both the listener and the speaker play a significant role. Therefore, both need to be able to produce and understand phonological features that guarantee communication. Jenkins (2000) studied how speakers use segmentals (vowels and consonants) and suprasegmentals (prosodic features such as thought groups, word stress, rhythm, sentence stress and intonation) to convey messages. As a result, she has devised the Lingua Franca Core of phonological features that need to remain standard for all speakers of EIL to be able to interact successfully. The core includes mostly segmental features. Nevertheless, Jenkins also acknowledges the importance of some suprasegmental features for intelligibility, such as thought groups (semantic units of intonation) and nuclear contrastive stress (strong words in a statement or strong syllables in a word).

Other researchers have attributed a significant role to suprasegmentals for communication throughout the years. Crystal (1975) has defined intonation not as an isolated category, but as “the product of the interaction of features from different prosodic systems—tone, pitch-range, loudness, rhythmicality, and tempo, in particular” (p. 9). This suggests that intonation implies more than falling or raising one’s tone during speaking, as students expressed in the needs analysis stage. Instead, it appears to be the interaction of all these prosodic features that helps the speaker express meanings. As Bradford (1988) explains, people can convey different ideas by using the same words in the same order, but saying them in diverse ways.

Recently, several studies have investigated stress and intonation. Field (2005), for instance, studied the effect of manipulated lexical stress on the perception of intelligibility of native and nonnative listeners. The results suggested that the consequences of misinterpreting even a small number of content words can be extremely damaging to global understanding. Field (2005) focused his study on stress as “research evidence suggests that suprasegmentals play a more important role than segmentals on communication” (p. 402). This can explain the need for research on the field of suprasegmentals. Similarly, Hahn (2004) focused on stress and analyzed native English speakers’ reactions to nonnative primary stress in English discourse. Her results evidenced that primary stress contributes significantly to the intelligibility of nonnative discourse. Finally, Rasmussen and Zampini (2010) analyzed the impact of phonetics training on the intelligibility of native speakers of Spanish as perceived by L2 learners. Their results illustrate the benefits of phonetics training for enhancing intelligibility.

93

In the Colombian context, a limited number of studies have approached suprasegmental features to build intelligibility. Frodden and McNully (2007) explain how they implemented a traditional approach to teaching pronunciation to adult university students by focusing on segmentals and moving gradually to suprasegmentals. They concluded that suprasegmental aspects of English enhance learners’ intelligibility and make native speakers more intelligible to them. Their paper illustrates the way teachers traditionally approach phonological elements in the Colombian classrooms. Nevertheless, the authors recognize that “the neglect for teaching pronunciation in recent years may be due to a misconception about what the content of a pronunciation course should be and also about the way pronunciation should be taught” (p. 102).

Although research around the world has highlighted the impact of stress and intonation in building intelligibility, most studies have followed the tradition of analyzing the perception of native speakers. This approach may disregard the actual communication patterns in the context of EIL in which speakers do not usually need to interact with native but rather with non-native speakers. Therefore, a more realistic approach is needed to understand the impact of these suprasegmental features on the communication among speakers of different varieties of English. Additionally, in the Colombian context there seems to be a research gap in this field because little research has analyzed the training on suprasegmental features to improve speakers’ intelligibility.

Language Awareness

Language awareness (LA) has been recently conceived as a broad concept that goes beyond the mere knowledge of how language works. Van Lier (1996) explains all of the domains that LA encompasses. Affective, social, cognitive, and even power relationships have been considered inside the umbrella term LA. Within the affective domain in particular, the concept of the learner-centered second/foreign language teaching has also been considered. According to Van Lier (1996), LA involves forming attitudes, developing attention, and evaluating the way speakers use the language for communication—behaviors that were closely related to the strategies developed by the participants of this study throughout the intervention.

Ellis (1994) provides a wider explanation of the role of awareness in foreign language acquisition and learning. Through an extensive literature review, he points out that explicit knowledge or awareness functions as a facilitator for learners to notice features in the input that they would otherwise miss. Similarly, it helps them compare what they notice with what they produce. Ellis’s conclusion explains the need for advanced learners to be aware of the role of stress and intonation for communication. Students’ awareness enabled them to contrast what they noticed with their actual production to assess their own outcomes.

Historically, most studies related to the conscious development of phonological awareness have been focused on the perception of native speakers. Venkatagiri and Levis (2007), for instance, examined the relationship between phonological awareness and speech comprehensibility in adult learners of EFL in The United States. Their findings revealed that form-focused instruction in phonology contributes to the comprehensibility of EFL speakers as perceived by native speakers. In Asia, researchers have carried out several studies regarding language awareness. Jin (2011) applied the theory of noticing, which aims at renewing teaching ideas, improving teaching methods, and learning strategies in English teaching and learning in China. Takimoto (2008) studied the differences between deductive and inductive training on pragmatics. His findings highlight the importance of phonological awareness to improve the students’ performance in oral tasks.

Kennedy and Trofimovich (2010) examined the relationship between the quality of L2 learners’ language awareness and the quality of their L2 pronunciation. They analyzed the comments participants made in journals about their own process of assimilation and production of suprasegmental aspects of English. Their study demonstrated that higher pronunciation ratings were associated with a greater number of language awareness comments. Thus, there is a relationship between the level of intelligibility of students’ production and their

94

level of awareness of how suprasegmental aspects work and how they can acquire them. Kennedy and Trofimovich’s work served as a model for the present study as it analyzed the students’ level of intelligibility with their level of awareness, which was one of our objectives. It also provided a state-of-the-art description of the field of awareness and phonology, although the authors acknowledge not to have found much literature regarding these areas because most research on awareness focuses on grammar rather than pronunciation.

A similar research gap appears to exist in the Colombian context. Some studies such as that of Camargo and Hederich, (2010) have analyzed the relationship between language awareness and the learning process. They have acknowledged that besides learning content, it is necessary to learn its form. However, studies on LA seem to be quite general and not many have focused on phonological awareness in Colombia. For instance, Quintero, Leon, and Pino (2011) focused on phonological awareness to develop the reading process in L1 young learners. Uribe (2012) analyzed language awareness to facilitate interaction. She stated that language awareness helps speakers understand what interlocutors really mean and identify the right moment to intervene. These studies were useful for the researcher to identify what has been done in terms of LA in relation to learning and communication in Colombia as there seems to be a research gap as it relates to the impact consciousness may have on students’ learning and communication.

Metacognitive Strategies

The concept of learning strategies has been discussed by several authors such as Chamot, Barnhardt, El-Dinary, and Robbins (1999), Oxford (1990), Ellis (1994), and Zimmerman (2000) since the early 1980s. Although authors agree that strategies facilitate learners’ successful performance in a specific task, some of them have differed on their concept and classification of language learning strategies. According to Ellis (1994), it is not clear whether they are to be perceived as behavioral or as mental processes, or as both. Nevertheless, Oxford (1990) assumes language learning strategies as mainly behaviors or actions taken by the learner to make learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self-directed, more effective, and more transferrable to any situation. Oxford’s definition served to support this research study as she takes an affective and self-directed approach which was useful for assessing students’ awareness of their use of suprasegmentals. Also, her framework suits the strategies and stages implemented.

Oxford (1990) points out that language learning strategies stimulate the growth of communicative competence. For instance, direct strategies (e.g., memory, cognitive, and compensation) involve the target language directly. They aim at helping learners perform better in specific tasks in the target language. Indirect strategies, on the other hand, support language learning as such. They manage learning without directly involving the target language. The current study focused on indirect strategies to guide students to raise awareness of their own learning process and oral production.

Regarding indirect strategies, metacognitive strategies provide a way for learners to coordinate their own learning process. They include three strategy sets: centering one’s learning, arranging and planning one’s learning, and evaluating it. In this study, I decided to work with one strategy from each group because they gradually guided students towards a smooth self-regulated learning process through various stages and tasks (pre, while and post). These strategies were:

Overviewing

Overviewing corresponds to “centering one’s learning,” the first group of metacognitive strategies described by Oxford (1990). It refers to the association of previous and new language with an upcoming task. It helps the learner understand why an activity is being done. This strategy was useful for students to pay closer attention to the use of suprasegmentals in a conscious way, which they tended to ignore, even though they were acquainted with the concept of stress and rising/ falling intonation. It helped participants to relate their previous theoretical knowledge to the upcoming tasks and how such knowledge could help them convey messages more intelligibly.

95

Setting goals and objectives

This strategy corresponds to the second group of metacognitive strategies presented by Oxford (1990): arranging and planning one’s learning. This implies setting students’ own aims for language learning. Oxford suggests keeping track of these objectives in a journal, along with deadlines for accomplishing them and an indication as to whether those deadlines were met. This strategy worked for the current research context because participants were the ones who decided the extent to which they wanted to incorporate suprasegmental features to their oral speech. This decision depended on students’ long-term goals such as using English to interact with native or non-native speakers, to learn English for specific purposes, or for reading or writing exclusively, as in some academic contexts.

Self-evaluating

This strategy refers to evaluating one’s own progress in the target language. It belongs to the third group of metacognitive strategies and it implies measuring students’ own progress in the use of any piece of language, in this case, suprasegmental features. Oxford proposes several ways for learners to gauge their progress. For instance, recording and then listening helped learners critically assess their own register.

The taxonomy presented by Oxford (1990) fits the principles and components of self-regulated learning explained by Zimmerman (2000) which include: setting specific goals, adopting strategies to attain them, monitoring one’s performance, restructuring one’s time and context, self-evaluating, and adapting future methods. Additionally, it agrees with the views of Ridley, Schutz, Glanz, and Weinstein’s (1992) regarding self-regulation. Even though their approach is psychological and not necessarily pedagogical, both Ridley et al. (1992) and Oxford’s (1990) proposals share the focus on the individual as an active agent in his/her own learning process metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally. Ridley et al. (1992) studied how goal-setting and metacognitive awareness relate to students’ performance. The authors found a close relation between these self-regulatory processes. Regarding this relationship, they suggest that a student who effectively self-regulates is one who bases explicit goals for his own learning on elevated levels of selfawareness. This student will likely outperform others because he has both a target goal, which provides a motivating challenge, and metacognitive awareness, which provides information about possible appropriate strategies for accomplishing the goal (p. 295). Their insights supported the relationship between advanced learners’ use of metacognitive strategies to self-regulate in the three stages of the tasks. During the first stage of the intervention, students received training on overviewing and setting goals which, according to the authors, may have motivated and challenged them. Secondly, students evaluated their own goal accomplishment by the end of the intervention. This helped them keep track of their progress regarding the use of suprasegmentals and, at the same time, assess the effectiveness of the strategies used, which increased their metacognitive awareness.

In the Colombian context, a wide range of research has approached learning strategies. For instance, Orrego and Díaz Monsalve (2010) analyzed the learning strategy use by university students in Antioquia. Their results demonstrated that cognitive, social, and compensation strategies are the most frequently used by young adult learners. They did not, however, analyze the use of metacognitive strategies. Diaz (2015) examined the effects of metacognitive strategies to help students recall vocabulary. She instructed them in the use of strategies for planning, monitoring, and evaluating their own vocabulary acquisition and she found that metacognitive strategy training contributed to the participants’ learning process. Her approach, based on the cognitive academic language learning (CALL) instructional model, related to the approach followed by the present research study.

Other Colombian researchers have focused on metacognitive strategies to approach different language skills. Flórez et al. (2005), for example, explored metalinguistic skills and metacognitive operations and their relationship with reading and writing. Their findings show that even young learners can perform successfully in tasks that require metacognitive skills when they are instructed on such strategies. Also, Camelo (2010) analyzed how

96

writing can be improved through metacognition. Her results show that the quality of writing increased significantly due to the reflective process young learners went through with the guidance of the teacher and peers.

Rodriguez (2007) conducted an action research study with a population of a similar profile to the one in the current study. He instructed young adults at a language center in the use of metacognitive strategies to keep track of their progress in listening through a journal. Although his work did not focus on the students’ oral progress, Rodriguez implemented the same type of strategies in a comparable context and reported satisfactory results such as progress in the participants’ listening comprehension and a higher level of metacognitive awareness. Rodriguez provided a model for me to develop this study with a population who may benefit from metacognition and self-regulated learning.

In Colombia, many researchers have conducted studies in metacognitive strategies to improve different language skills. Few, however, have studied the implications of such strategies in the students’ awareness of their own register. For this reason, instructing students in the use of metacognitive learning strategies to keep track of their oral progress is relevant to discussions of the effectiveness of the approach Colombian teachers tend to use to approach pronunciation and what implications their methods have on the students’ learning and intelligibility.

To conclude, in this section, I took into consideration the work of scholars in the fields of intelligible stress and intonation, language awareness, and metacognitive strategies to set the theoretical basis of the study. In addition, I considered recent studies carried out by both international and national researchers in these fields to develop an innovative proposal that responds to the research gaps encountered.

Methodology

The current study corresponds to qualitative action research since it analyzes and describes a process that takes place in an educational context. It involves the teacher’s reflective, critical, and systematic approach to explore and problematize her teaching milieu, as explained by Burns (1999). The learners’ lack of awareness of the use of suprasegmentals for communication was identified as problematic within this context. As the teacher, I played distinct roles in the classroom to bring about changes that may solve such a problem.

The study followed the principles of qualitative research presented by Ritchie and Lewis (2003). According to these authors, this naturalistic approach aims at interpreting phenomena by means of rich qualitative data. As such, data were collected from the participants by means of learning logs, recordings, and observations that helped me analyze the problematic situation and propose changes from solid data, rather than from assumptions.

Context

The current study took place in the Adult English Program, an EFL course taught at a private language center in Bogotá, Colombia. The institutional teaching cornerstones include the communicative approach, task-based learning, ongoing assessment, and autonomous learning, for which instruction on learning strategies is a class routine. Courses in this institution are divided into three main blocks according to the language level. The study was implemented in the last block, in which learners’ level is advanced (B1) according to the CEFR.

The advanced block consists of three courses. Each of them lasts one month and classes are taken Monday through Friday for two hours. In this block, learners complete a project called global citizenship, the outcome of which is a position paper about a controversial topic. In the first month, learners choose their topic; in the second, they write the paper, and during the third month, they prepare and carry out an oral presentation. This project is relevant for the current research study because the instruction in metacognitive strategies had to adapt to the course project and syllabus, as well as the pace, and the instruments used for data collection had to relate to the project tasks.

97

Participants

The participants were a group of ten adult learners whose ages ranged from 18 to 30 and whose language level ranged from A2 to B1 according to the CEFR. They had been studying English for approximately one year at the institution and were able to communicate in English and to use several learning strategies. Although they studied together, their educational and professional backgrounds differed significantly as well as their learning goals. Several learners were professionals who aimed at learning English to enrich their professional profile. Two were university students, and one was a master’s student. The differences between the participants had an impact on the development of the current research project as most professional learners were willing to participate and showed a great deal of interest in improving their fluency and oral skills. In contrast, the university students who had less academic experience, did not show as much interest in the oral component. Instead, they were more engaged in class activities related to writing and reading.

After observing the learners’ difficulty in using suprasegmentals and having conducted the needs analysis questionnaire, I posed the following research question:

To what extent might the use of three metacognitive learning strategies: overviewing, goal-setting, and self-evaluating raise awareness of students’ intelligible stress and intonation in English?

To answer this question, a three-cycle research process was implemented. Each cycle lasted two weeks and integrated the instruction on metacognitive strategies and suprasegmentals in the regular classes of the advanced block at the institution. During the first cycle, students were instructed on the use of one metacognitive strategy for different purposes. For instance, they used goalsetting to set their own objectives before listening and speaking tasks; they used overviewing as a strategy to help them integrate target vocabulary. They also self-evaluated their progress in terms of speaking by means of a rubric designed by themselves.

Instruction on metacognitive strategies took about an hour every day and followed the steps suggested by Chamot, Barnhardt, El-Dinary, and Robbins (1999) which include: preparation, presentation, practice, evaluation, and expansion. These steps helped the researcher incorporate the strategies smoothly in the class dynamics and facilitated students’ integration of strategies in their own learning process.

During the second week of each cycle, students learned to identify a suprasegmental feature from video or audio input. For instance, they analyzed how international speakers in a video stressed important words in their utterances to give relevance to certain items. Learners could analyze how nuclear contrastive stress modifies a speakers’ message. Moreover, students were exposed to audio input in which speakers made descriptions of different topics in a fluent and intelligible way. Through this kind of exercises, students analyzed how intonation implies more than falling or raising one’s tone during speaking, which, according to the needs analysis, was their initial belief. Instead, they concluded that the interaction of prosodic features (pitch-range, loudness, rhythmicality, and tempo) helps speakers to express meaning.

At the end of each cycle, students used the metacognitive strategies to monitor their use of suprasegmental features. They recorded and listened to themselves in different controlled and spontaneous tasks, and they analyzed the extent to which they used stress and intonation to accompany their speech and to make it more intelligible.

Instruments

Three main instruments were used to collect data: learning logs, recorded artifacts, and field notes. These instruments were chosen due to the nature of the course project, while equally taking into consideration previous research. Learning logs allowed the researcher to perceive students’ insights about the strategies used and their own process.

Recorded artifacts were used to log information about the students’ actual use of suprasegmental features. These recordings allowed students to speak and listen to themselves to monitor their speech. Furthermore, they allowed me to listen to the students’ production and analyze it. Lastly,

98

recorded artifacts were used considering other researchers’ previous experience such as Kennedy and Trofimovich (2009) who analyzed the quality of second language (L2) learners’ awareness and the quality of their L2 pronunciation. In this way, they implemented both a journal (learning log) and recordings made by the participants. Although Kennedy and Trofimovich used specialized software to analyze the students’ production, this study used a simpler tool, Audacity, which allowed the analysis of the speakers’ utterances by means of graphs that illustrated their use of stress and intonation.

My own field notes were used to log the impressions that I obtained in my role as a researcher, observer, and participant. According to Mills (2003), field notes are written records of participant observers that allow them to reconstruct events, observations, and conversations that take place in the field. They were particularly useful in this study because they allowed me to keep track of informal comments made by students in class, their gestural expressions, and their observations.

During the data analysis stage, data were triangulated as follows: first, students’ comments on their learning logs were analyzed and categorized by color coding according to the research constructs, e.g., metacognitive strategies, language awareness, and intelligible stress and intonation. Data collected in the learning logs were triangulated with the information from the recorded artifacts. This contrast provided the researcher with information about the construct of intelligible stress and intonation because she could analyze the students’ use of suprasegmental features and their insights about their performance.

Students’ learning logs were triangulated with the teacher’s field notes. This contrast provided me with insights related to the constructs of language awareness and metacognitive strategies as I compared the students’ insights and my own impressions and reactions towards the strategies used in class.

Finally, my field notes as the teacher were triangulated with the students’ recorded artifacts. This contrast provided me with ideas about the students’ intelligible stress and intonation in spontaneous and recorded speaking. This contrast allowed me to identify meaningful differences between students’ performance in controlled activities, in which using the suprasegmental features was the main goal, to the students’ performance in spontaneous interaction, in which they were expected to use such features although the main goal was mainly communicative.

Results

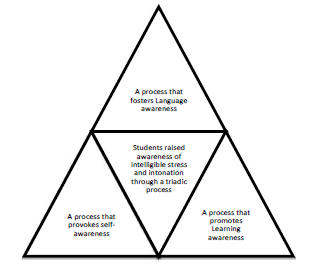

Data collected from each instrument were systematized and organized in a matrix to analyze the relationships among pieces of data. Following the steps for data reduction and data analysis stated by Corbin and Strauss (2008), I went through open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. During open coding, I assigned codes to the data from the three instruments to make it manageable. During axial coding, commonalities were identified and pieces of data were grouped into five subcategories, which were later reduced to three. During the selective coding stage, the three main categories were put together in a core category that explained the ways in which learners raised awareness: students enhanced awareness of intelligible stress and intonation through a triadic process: a process that fostered language awareness, a process that promoted language awareness, and a process that provoked self-awareness.

Diagram 1. explains the categories emerged from the axial coding stage.

99

Category 1: Fostering Language A wareness

After the implementation, learners seemed to have improved their language awareness in two aspects: the actual use of stress and intonation, and their communicative value. This language awareness was evident in the analysis of the students’ learning logs and teacher’s field notes during the open coding stage. Data from these instruments revealed what Svalberg (2012) called engagement with language. Learners showed evolution in their language awareness after elaborating on their language related knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes. For instance, they seemed to understand more complex uses of suprasegmentals than the ones they initially knew, which is evident in some of the learners’ entries in their learning logs. For example:

Also, I have to improve the stress for content

words.

(Learning log 2. Student 7)

It appears that language awareness was fostered in two ways: (a) understanding the actual use of stress and intonation, and (b) acknowledging their communicative value. Such results are illustrated below.

Understanding the actual use of stress and intonation.

As Svalberg (2012) explains, noticing and attention are important concepts in language awareness. They imply directing one’s attention to specific target features. During the implementation of this study, learners were guided to pay attention to stress and intonation both in a theoretical and practical way. Videos exposed learners to the use of these features, and the class discussions that followed aimed at addressing their attention towards these target features. This excerpt from my field notes as the teacher reveals how I perceived that learners were aware of the use of suprasegmentals.

When preparing ideas before interaction, most

students were able to use arrows and parenthesis

to identify intonation patterns and thought groups.

(Field notes, session 8)

Acknowledgement of the communicative value of stress and intonation.

According to Canagarajah (2005), “students should be able to inductively process the underlying system in the varieties one encounters in social interaction” (p. 27). This suggests that in the context of English as an international language, learners may benefit from analyzing the actual use of different varieties of English in order to incorporate the aspects that facilitate communication among different kinds of speakers.

Some verbs ended by “ed" are hard for me to performance. Also I have to improve stress for content words.

(Learning log 2. Student 7)

This excerpt relates to the awareness scholars say that learners of English as an international language should develop because the learner realized in the input how speakers of different varieties of English pronounced past verbs and stressed them at the moment of speaking to emphasize, which helped them convey ideas clearly.

Category 2: Promoting Learning Awareness

The open coding stage revealed several codes related to learning. The students’ learning logs and the teacher’s field notes evidenced common codes in regard to this dimension. First, the learning logs contained comments related to the learners’ understanding of how to deal with the metacognitive strategies studied: goal setting and overviewing. They also referred to their acknowledgment of the usefulness of such strategies to complete the assigned tasks. Furthermore, the training on these metacognitive strategies helped them give steps towards self-regulation because they seemed to be aware of their difficulties and possible ways to improve. Their learning logs reveal such a kind of awareness:

As for me, I still have problems with intonation. I heard myself too plane and I need to improve that part if I want my English sounds natural. There are a lot of exercises on the book I can work on. Try to do those exercises weekly and make a self-

100

monitoring of my progress recording my voice

while reading a short text.

(Learning log. Student 4)

This excerpt shows this student’s awareness of his difficulties and how one of the strategies used in the implementation could help him improve. Nevertheless, not all learners included comments related to the usefulness of the metacognitive strategies for their learning processes. Two students wrote very general comments in their learning logs, which did not evidence significant reflection. Comparing the learning logs and the recorded artifacts, a relation was found between the quality of the students’ reflective comments and their actual production of stress and intonation.

Category 3: Provoking Self-Awareness

This category was named as such as some codes that appeared in the learning logs and teacher’s field notes referred to the learners’ own persona, whether as a learner or as an English speaker. Initially, I thought this was derived from language awareness in the sense that learners could identify the right use of suprasegmentals in their own speech, just as they did with the speakers from the video input. However, after the open coding stage, I realized that learners were initially unaware of what they sounded like. After the implementation, this situation had a slight change. Therefore, learners were more conscious of their own actual register. They were able to recognize the peculiarities of their speech as English communicators and they seemed to understand what areas they need to improve to become more intelligible.

Identification of one’s own actual register.

The recorded artifacts revealed students’ ideas in which they reported being able to communicate intelligibly, but after recording and listening to themselves, their perception of themselves as speakers changed. It seems that they became more aware of what they actually sound like in English. Other studies have found a similar kind of awareness after learners’ recording and listening to themselves. Arévalo (2014) reports that selfrecordings allow learners to adopt new methods to reflect upon their own strengths and weaknesses in terms of pronunciation. The students’ learning logs reveal a more realistic perception of themselves as intelligible speakers, after listening to themselves.

I noticed about I talk so slow and without use the linking, probably, for to not practice my speaking for example, read aloud and stuff like that. Trying to say my paragraphs, and recording them, I realized that I need to improve the linking when I talk, because it’s important to said the things more naturally.

(Learning log 2. Student 3)

Enhancement of self-confidence as English speaker.

There seems to be a relation between the learners’ intelligibility and the learners’ self-concept. Ushioda and Dornyei (2009) explain different perspectives to analyze the concept of self in the context of English as an international language, in which intelligibility is not only desired but required. They explain that proficiency in the target language (intelligibility in the context of this study) is part of one’s ideal self, and that it plays the role of a motivator to learn the language or in our context to improve one’s intelligibility. The participants in this study used expressions such as: improving fluency, being more natural, and feeling more confident to describe their register after the implementation. This was evident both in their learning logs and the teacher’s field notes.

Despite it was my own composition I felt comfortable reading it. I was very fluent while I was reading it.

(Learning log 2. Student 4)

This entry reveals how the learner felt more confident about speaking English despite the difficulties they had in implementing suprasegmentals. This can be explained in the light of a psychological approach that explains learners’ reactions towards their goals. Dweck (2000) states that learners facing a learning goal feel challenged and willing to increase their competence. Students in the target population could have been challenged

101

by the difficulty they had using suprasegmentals and consequently tried to use them. Listening to themselves and noticing improvement could have had an impact on their perception of themselves as speakers.

Core Category

Through the interrelation of the three categories presented above and the literature that supports them, a core category appeared: students enhanced awareness of intelligible stress and intonation through a triadic process. The term triadic process was chosen because the enhancement of the students’ awareness did not occur immediately or quickly. On the contrary, learners took long time to take steps towards awareness of intelligibility and they are still in the process to figure out how to be more intelligible. Developing awareness requires time for strategy use, reflection, and implementation of the target areas in one’s speech. Additionally, the metaphor of the triad was used to illustrate the three areas in which awareness could have been developed, which were interrelated and equally important for the implementation of the current study. In fact, after implementing the strategies and activities proposed for this research study, it was evident that advanced English learners can raise awareness of their own intelligible stress and intonation by a triadic process that involves: (a) fostering language awareness to understand the use of suprasegmental features and acknowledge their communicative value, (b) promoting learning awareness to use metacognitive strategies to become self-regulated learners, and (c) provoking self-awareness thanks to the identification of the learner’s own actual register, which helped them enhance their self- confidence as English speakers.

The findings of this research project call to mind the results of research on the relation between language awareness and second language pronunciation carried out by Kennedy and Trofimovich (2009) in Canada. They found a relation between the students’ pronunciation ratings, and the number of qualitative language awareness comments in their journals. They demonstrated that higher pronunciation ratings were associated with a greater number of qualitative language awareness comments. Although their research used mainly quantitative methods to collect and analyze data, the current study had similar results from a merely qualitative and descriptive analysis. Therefore, I can conclude that the relationship between language awareness and oral production may be stronger than it was initially thought. In fact, as a teacher, I may have disregarded how language awareness can foster intelligibility in the classroom.

Conclusions

The results of this study have important implications for the teaching of pronunciation and, specifically, for the teaching of suprasegmental features in Colombia, which have been traditionally approached from the perspective of a native-speaker listener who assesses the students’ levels of intelligibility. Considering that Colombian EFL learners do not mainly interact with native speakers, and that in the growing context of English as an international language, it is unlikely that they need to do so; thus, the traditional approach to teach suprasegmentals appears to be unnecessary and outdated.

To meet the actual needs of EFL students’ in the Colombian context, teachers may need to tackle suprasegmentals from a more practical and realistic approach in which students are exposed to international or Colombian speakers who effectively modify their speech to convey meaning. This may help them draw their own conclusions on the use of suprasegmentals, and raise awareness of their communicative role. Additionally, students’ conclusions may be meaningful and may help them intentionally modify their speech to be more intelligible. Increasing intelligibility can be a way to help students reach the language level they are expected to and most importantly, become better communicators and learners, which in the end is the ultimate goal of EFL teaching.

This study addressed some of the needs that the particular target population had at the institution. Even though most students developed awareness of at least one of the emergent categories, two of them did not show much interest in participating or did not show evidence of having developed

102

much awareness. The reasons for that to have occurred range from time limitations to individual interests but several questions arise from those particular situations: what effects will the study have on a different population? Would this study have comparable results in a different institution where learners are not trained in strategies? Further research would be needed to answer such questions.

References

Arévalo, J. (2014). Improving pronunciation skills through self-recordings. (Unpublished Master’s Thesis). Universidad de La Sabana, Bogotá.

Bradford, B. (1988). Intonation in context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Camargo, A., & Hederich, H. (2010). La relación lenguaje y conocimiento y su aplicación al aprendizaje escolar. Revista Folios, 5(31), 105-122.

https://doi.org/10.17227/01234870.31folios105.121

Camelo, M. (2010). Using metacognitive processes to improve students’ writing quality. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 12(1), 54-69.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2005). From Babel to Pentecost: Postmodern glottoscapes and the globalization of English. In L. Anglada, M. Barrios, & J. Williams (Eds.), Towards the knowledge Society: Making EFL education relevant (pp. 22-35). Córdoba, Argentina: Comunic-arte Editorial.

Chamot, A., Barnhardt, S., El-Dinary, P, & Robbins, J. (1999). The learning strategies handbook. White Plains, NY: Pearson.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory: Procedures and

techniques (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

https://doi. org/10.4135/9781452230153

Crystal, D. (1975). Intonation and linguistic theory. In K. H. Dahlstedt (Ed.), The Nordic languages and modern linguistics. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

Crystal, D. (2004). The past, present and future of world English. In A. Gardt & B. Hüppauf (Eds), Globalization and the future of German (pp. 27-45). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110197297.27

Council of Europe. (2011). Common European framework of reference for learning, teaching, assessment. Council of Europe.

Diaz, I. (2015). Training in metacognitive strategies for students’ vocabulary improvement by using learning journals. PROFILE: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 17(1), 87-102.

https ://doi. org/10.15446/prof ile. v 17n1.41632

Dweck, C. S. (2000). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Field, J. (2005). Intelligibility and the listener: The role of lexical stress. TESOL Qua.rterly, 39(3), 399-423.

https://doi.org/10.2307/3588487

Flórez, R., Torrado, M., Rodriguez, I., Güechá, C., Mondragon, S., & Perez, C. (2005). Habilidades metalingüísticas, operaciones metacognitivas y su relación con los niveles de competencia en lectura y escritura: un estudio exploratorio. FORMA Y FUNCIÓN, 18, 15-44.

Frodden, C. & McNully, M. (1997). A new look at suprasegmentals. Ikala, 1(1), 101-116.

Graddol, D. (2006). English next. London: British Council.

Hahn, L. D. (2004). Primary stress and intelligibility: Research to motivate the teaching of suprasegmentals. TESOL Quarterly, 38(2), 201-223.

https://doi.org/10.2307/3588378

Jenkins, J. (2000). The phonology of English as an international language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jin, J. (2011). An evaluation of the role of consciousness in second sanguage learning. International Journal of English Linguistics, 1(1), 126-136.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v1n1p126

Kennedy, S., & Trofimovich, P. (2010). Language awareness and second language pronunciation: A classroom study. Montreal: Routledge.

Kenworthy, J. (1987). Teaching English pronunciation. London: Longman.

Mills, G. (2003). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Orrego, L. M., & Díaz Monsalve, A. E. (2010). Empleo de estrategias de aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras: Inglés y francés. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 15(24), 105-142.

103

Peñuela, D. (2018) • Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J.

Printed ISSN 0123-4641 Online ISSN 2248-7085 • January - June 2018. Vol. 20 • Number 1 pp. 11-24.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language learning strategies. What every teacher should know. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Quintero, A., Leon, A., & Pino, M. (2011). Conciencia fonológica y su relación con las dificultades de lectura. Cultura, Educación, Sociedad, 2(1), 25- 34.

Rasmussen, J. & Zampini, M. (2010). The effects of phonetics training on the intelligibility and comprehensibility of native Spanish speech by second language learners. In J. Levis & K. LeVelle (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1st Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference (pp. 38-52), Ames, IA: Iowa State University.

Richards, J. (2008). Moving beyond the plateau: From intermediate to advanced levels in language learning. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ridley, D. S., Schutz, P A., Glanz, R. S., & Weinstein, C. E. (1992). Self-regulated learning: The interactive influence of metacognitive awareness and goal setting. The Journal of Experimental Education, 60(4), 293-306.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1992.9943867

Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (Eds.). (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: SAGE Publications.

Rodriguez, E. (2007). Self-assessment practices: An empowering tool in the teaching and learning EFL processes. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 9, 229-246.

Smith, L. (1992). Spread of English and issues of intelligibility. In B. B. Kachru (Ed.), The Other Tongue (pp. 75-90). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Svalberg, A. (2012). Language awareness in language learning and teaching: A research agenda. Language Teaching, 45(3), 376-388.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444812000079

Takimoto, M. (2008). The effects of deductive and inductive instruction on the development of language learners’ pragmatic competence. The Modern Language Journal, 92(3), 369-386.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1540-4781.2008.00752.x

Uribe, O. (2012). Helping business English learners improve discussion skills. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 12(2), 127-145.

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour. calj.2012.2.a08

Ushioda, E., & Dornyei, Z. (Eds.). (2009). Motivation, language identities and the L2 self: A theoretical overview. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Van Lier, L. (1996). Interaction in the language curriculum: Awareness, autonomy, and authenticity. London and New York: Taylor & Francis.

Venkatagiri, H., & Levis, J. (2007). Phonological awareness and speech comprehensibility: An exploratory study. Language Awareness, 16(4), 263-277.

https://doi.org/10.2167/la417.0

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of selfregulation (pp. 13-39). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50031-7

104

Recibido: 16 de junio de 2017; Aceptado: 14 de enero de 2018

Resumen

Pocos estudios han analizado el impacto de la conciencia del lenguaje y las estrategias metacognitivas en el contexto del inglés como lengua extranjera. Este estudio cualitativo de investigación acción examinó el impacto de tres estrategias metacognitivas en el reconocimiento y uso de aspectos suprasegmentales como la entonación y el acento en un grupo de 10 participantes, estudiantes de nivel avanzado de inglés en una academia privada. En entrevista preliminar, mostraron desconocimiento del rol comunicativo de los suprasegmentales. Posteriormente se entrenaron en el uso de una estrategia metacognitiva y un aspecto suprasegmental en cada uno de tres ciclos de implementación. Los instrumentos de recolección de datos fueron diarios, grabaciones, y notas de campo de la profesora. Los resultados mostraron que los participantes tomaron conciencia en un proceso triádico que incluyó: un conocimiento metalingüístico, la toma de conciencia de su aprendizaje y la conciencia de sus capacidades. Los resultados del estudio sugieren una revisión de la enseñanza actual de la pronunciación un análisis sobre la implementación del paradigma del inglés como lengua franca en el contexto colombiano.

Palabras clave:

inteligibilidad, entonación, conciencia lingüística, estrategias de aprendizaje, suprasegemental, acento.Abstract

Few studies have analyzed the impact of language awareness and metacognitive strategies for intelligibility in the context of English as an international language. This qualitative action research study examined the impact of using three metacognitive strategies-overviewing, goal setting, and self-evaluating-to raise adult learners’ awareness of stress and intonation at a private language center in Bogotá. Ten participants enrolled in an advanced English course showed lack of awareness of the use of suprasegmentals (stress or intonation) to communicate intelligibly in a preliminary oral interview. The implementation took three cycles each lasting one hour every day for two weeks. During the first week, the participants were trained to use one metacognitive strategy. During the second week, they identified a suprasegmental feature from video or audio input. Finally, they monitored the use of the feature through the strategy they had learned in the first week. Data were collected via learning logs, recorded artifacts, and field notes. The results showed that students raised awareness in a triadic process that involves metalinguistic, learning, and self-awareness. Results may be useful to revisit the current teaching of pronunciation and to provide insights about the use of elements from the lingua franca core in the Colombian context.

Keywords:

intelligibility, intonation, language awareness, learning strategies, suprasegmental, stress.Introduction

Advanced learners of English as a foreign language (EFL) face enormous challenges in the pursuit of fluency. Richards (2008) states that one of the problems they encounter is that even though their language production may be adequate, it often lacks the characteristics of intelligible speech. Although the term intelligibility has been widely discussed by scholars throughout the last decade, Jenkins (2000) provides the most appropriate definition for the context of this research study. According to her, intelligibility refers to the phonological features necessary for communication among speakers of English as an international language.

To speak intelligibly, advanced EFL learners need to use a variety of phonological elements. However, once learners can make themselves understood through other linguistic features such as grammar and vocabulary, they appear to disregard how phonological elements help them convey messages more naturally and effectively. Therefore, it seems that learners need to raise awareness of both why and how phonological aspects are used in effective yet spontaneous communication. This paper analyzed the extent to which the use of three metacognitive learning strategies-overviewing, goal setting, and self-evaluating-may help students raise awareness of their stress and intonation in English.

The study was carried out at a private language center in Bogotá, Colombia which offers English courses through three programs to children, teenagers, and adults. The implementation took place in the adult English program (AEP) in which learners are classified according to their language level into three blocks: basic, skills (intermediate), and challenge (advanced).The AEP presents the skills learners are expected to have developed before starting advanced courses at the center on a document based on the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR; Council of Europe, 2011), which states that learners should be able to use correct intonation and stress patterns for different circumstances. However, the needs analysis procedure carried out for this research study evidenced students’ difficulty in using these phonological patterns. Most students seemed to struggle to stress relevant information in their speech, or to express ideas in thought groups. Instead, they used linear speech and communicated word by word, which complicated the listener’s understanding.

This problem might have occurred due to the influence of the institutional curriculum which focuses on accuracy and interaction, rather than training in phonology. In fact, results of the survey designed for the needs analysis procedure suggested that most learners in an advanced course considered accuracy, vocabulary, and pronunciation of English sounds to be important aspects when they speak. None of the participants considered intonation or stress to be important. Nevertheless, most participants acknowledged having received instruction in stress and intonation, but the questionnaire revealed that they did not use them spontaneously. This suggests that the type of instruction they received in regard to suprasegmentals might have been ineffective. It may also confirm what Kennedy and Trofimovich (2010) found in their study: that lack of awareness relates directly to poor use of linguistic elements. Therefore, raising students’ awareness of the use of suprasegmental features might help learners improve their usage and in the long term, reach the standards envisaged in the CEFR, as the AEP expects them to do.

Theoretical framework

This study considered seminal and contemporary theories to explain the concept of language awareness, metacognitive strategies, and intelligible stress and intonation. These constructs provide solid support for the research settings.

Intelligible Stress and Intonation

The concept of intelligibility has been widely debated by language teachers and researchers. Kenworthy (1987) sees intelligibility as being understood by a listener at a given time in each situation. This may suggest that understanding every word a speaker produces guarantees understanding the message he intends to convey. Later, Smith (1992) defined intelligibility as the ability to make one’s words and utterances recognized by others thanks to the appropriate production of its sounds. However, this definition seemed insufficient in the context of this study given that the learners’ words and utterances were generally well pronounced and therefore recognized by others, yet their messages were not clearly conveyed; they were not entirely intelligible.

Both Kenworthy (1987) and Smith (1992) regarded intelligibility as a one-way process in which non-native speakers struggled to make themselves understood by native speakers through English sounds. However, more recently, authors such as Jenkins (2000) , Crystal (2004) , or Graddol (2006) have questioned the extent to which this language is spoken by native or non-native speakers. Crystal (2004) states that the ratio of native to non-native speakers of English is around 1:3, which has changed the panorama of the phonological field. Because of the considerable number of non-native speakers of English around the world, the standard sounds and patterns of English have changed. Consequently, speakers no longer need to sound native-like to be considered as intelligible.

In the new panorama in which English is an international language (EIL), Jenkins (2000) has studied intelligibility as a two-way process involving both the speaker and listener in the production and recognition of phonological form. This definition implies that both the listener and the speaker play a significant role. Therefore, both need to be able to produce and understand phonological features that guarantee communication. Jenkins (2000) studied how speakers use segmentals (vowels and consonants) and suprasegmentals (prosodic features such as thought groups, word stress, rhythm, sentence stress and intonation) to convey messages. As a result, she has devised the Lingua Franca Core of phonological features that need to remain standard for all speakers of EIL to be able to interact successfully. The core includes mostly segmental features. Nevertheless, Jenkins also acknowledges the importance of some suprasegmental features for intelligibility, such as thought groups (semantic units of intonation) and nuclear contrastive stress (strong words in a statement or strong syllables in a word).

Other researchers have attributed a significant role to suprasegmentals for communication throughout the years. Crystal (1975) has defined intonation not as an isolated category, but as “the product of the interaction of features from different prosodic systems-tone, pitch-range, loudness, rhythmicality, and tempo, in particular” (p. 9). This suggests that intonation implies more than falling or raising one’s tone during speaking, as students expressed in the needs analysis stage. Instead, it appears to be the interaction of all these prosodic features that helps the speaker express meanings. As Bradford (1988) explains, people can convey different ideas by using the same words in the same order, but saying them in diverse ways.

Recently, several studies have investigated stress and intonation. Field (2005) , for instance, studied the effect of manipulated lexical stress on the perception of intelligibility of native and nonnative listeners. The results suggested that the consequences of misinterpreting even a small number of content words can be extremely damaging to global understanding. Field (2005) focused his study on stress as “research evidence suggests that suprasegmentals play a more important role than segmentals on communication” (p. 402). This can explain the need for research on the field of suprasegmentals. Similarly, Hahn (2004) focused on stress and analyzed native English speakers’ reactions to nonnative primary stress in English discourse. Her results evidenced that primary stress contributes significantly to the intelligibility of nonnative discourse. Finally, Rasmussen and Zampini (2010) analyzed the impact of phonetics training on the intelligibility of native speakers of Spanish as perceived by L2 learners. Their results illustrate the benefits of phonetics training for enhancing intelligibility.

In the Colombian context, a limited number of studies have approached suprasegmental features to build intelligibility. Frodden and McNully (2007) explain how they implemented a traditional approach to teaching pronunciation to adult university students by focusing on segmentals and moving gradually to suprasegmentals. They concluded that suprasegmental aspects of English enhance learners’ intelligibility and make native speakers more intelligible to them. Their paper illustrates the way teachers traditionally approach phonological elements in the Colombian classrooms. Nevertheless, the authors recognize that “the neglect for teaching pronunciation in recent years may be due to a misconception about what the content of a pronunciation course should be and also about the way pronunciation should be taught” (p. 102).

Although research around the world has highlighted the impact of stress and intonation in building intelligibility, most studies have followed the tradition of analyzing the perception of native speakers. This approach may disregard the actual communication patterns in the context of EIL in which speakers do not usually need to interact with native but rather with non-native speakers. Therefore, a more realistic approach is needed to understand the impact of these suprasegmental features on the communication among speakers of different varieties of English. Additionally, in the Colombian context there seems to be a research gap in this field because little research has analyzed the training on suprasegmental features to improve speakers’ intelligibility.

Language Awareness

Language awareness (LA) has been recently conceived as a broad concept that goes beyond the mere knowledge of how language works. Van Lier (1996) explains all of the domains that LA encompasses. Affective, social, cognitive, and even power relationships have been considered inside the umbrella term LA. Within the affective domain in particular, the concept of the learner-centered second/foreign language teaching has also been considered. According to Van Lier (1996), LA involves forming attitudes, developing attention, and evaluating the way speakers use the language for communication-behaviors that were closely related to the strategies developed by the participants of this study throughout the intervention.

Ellis (1994) provides a wider explanation of the role of awareness in foreign language acquisition and learning. Through an extensive literature review, he points out that explicit knowledge or awareness functions as a facilitator for learners to notice features in the input that they would otherwise miss. Similarly, it helps them compare what they notice with what they produce. Ellis’s conclusion explains the need for advanced learners to be aware of the role of stress and intonation for communication. Students’ awareness enabled them to contrast what they noticed with their actual production to assess their own outcomes.

Historically, most studies related to the conscious development of phonological awareness have been focused on the perception of native speakers. Venkatagiri and Levis (2007) , for instance, examined the relationship between phonological awareness and speech comprehensibility in adult learners of EFL in The United States. Their findings revealed that form-focused instruction in phonology contributes to the comprehensibility of EFL speakers as perceived by native speakers. In Asia, researchers have carried out several studies regarding language awareness. Jin (2011) applied the theory of noticing, which aims at renewing teaching ideas, improving teaching methods, and learning strategies in English teaching and learning in China. Takimoto (2008) studied the differences between deductive and inductive training on pragmatics. His findings highlight the importance of phonological awareness to improve the students’ performance in oral tasks.