DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a09Publicado:

2015-10-23Número:

Vol 17, No 2 (2015) July-DecemberSección:

Debates de enseñanzaA call for language assessment literacy in the education and development of teachers of English as a foreign language

Un llamado al desarrollo de la competencia en evaluación de idiomas a través de los procesos formativos de profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera

Palabras clave:

Evaluación, Competencia en Evaluación, Docentes de Inglés como Lengua Extranjera, Enseñanza de Inglés (es).Palabras clave:

Assessment, Assessment Literacy, English language teaching, EFL teachers (en).Descargas

Referencias

American Federation of Teachers, National Council on Measurement in Education, & National Education Association (AFT, NCME, & NEA). (1990). Standards for teacher competence in educational assessment of students. Educational Measurement:Issues and Practice, 9(4), 30-32.

Boyles, P. (2006). Assessment literacy. In Harmon, M. (ed.) New Visions in Action National Assessment Summit Papers. Iowa State University, IO.

Brown, G. (2008). Assessment literacy training and teachers’ conceptions of assessment. In C. Rubie-Davies & C. Rawlinson. (eds.), Challenging thinking about teaching and learning (pp. 285- 302). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Brown, D., & Abeywickrama, T. (2010). Language Assessment – Principles and classroom practices. New York: Pearson Longman

Coombe, C., Davidson, P., Sullivan, B., & Stoynoff, S. (2012). The Cambridge Guide to second language assessment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, A. (2008). Textbook trends in teaching language testing. Language Testing, 25(3): 327–347.

DeLuca, C., Klinger, D. (2010). Assessment literacy development: identifying gaps in teacher candidates’ learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17(4), 419-438.

Engelsen, K. S., & Smith, K. (2014). Assessment literacy. In C. Wyatt-Smith, V. Klenowski, & P. Colbert (eds.), Designing assessment for quality learning (pp. 91-108). New York: Springer

Fan, Y., Wang, T., & Wang, K. (2011). A web-based model for developing assessment literacy of secondary in-service teachers. Computers & Education, 57, 1727-1740.

Fulcher, G. (2012). Assessment literacy for the language classroom. Language Assessment Quarterly, 9(2), 113–132.

Jeong, H. (2013). Defining assessment literacy: Is it different for language testers and non-language testers? Language Testing, 30(3), 345-362.

López, A. A. (2008). Potential impact of language tests: Examining the alignment between testing and instruction. Saarbrucken: Vdm Publishing.

López, A., & Bernal, R. (2009). Language testing in Colombia: A call for more teacher education and teacher training in language assessment. Profile – Issues in professional development, 11(2), 55-70.

Malone, M. (2008). Training in language assessment. In E. Shohamy & N. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education: Vol. 7. Language testing and assessment (2nd ed., pp. 225-239). New York: Springer Science+Business Media.

Malone, M. (2011). Assessment literacy for language educators. CALDigest, October, pp. 1-2

Malone, M. (2013). The essentials of assessment literacy: Contrasts between testers and users. Language Testing, 30(3), 329-344.

Mertler, C. A. (2003). Preservice versus inservice teachers’ assessment literacy: Does classroom experience make a difference?. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Mid-Western Educational Research Association, Columbus, OH, October.

Retrieved from http://wps.ablongman.com/wps/media/objects/1530/1567095/tchassesslit.pdf

Mertler, G. A. (2004). Secondary teachers’ assessment literacy: does classroom experience make a difference? American Secondary Education, 33(1), 49–64.

Popham, W. J. (2004). Why assessment illiteracy is professional suicide. Educational Leadership, 62(1), 82-83.

Popham, W. J. (2009). Assessment literacy for teachers: Faddish or fundamental? Theory Into Practice, 48(1), 4-11.

Popham, W. J. (2011). Assessment literacy overlooked: A teacher educator’s confession. The Teacher Educator, 46, 265-273.

Scarino, A. (2013). Language assessment literacy as self-awareness: Understanding the role of interpretation in assessment and in teacher learning. Language Testing, 30(3), 309-327.

Schafer, W. D. (1993). Assessment literacy for teachers. Theory into Practice, 32(2), 118-126.

Siegel, M., & Wissehr, C. (2011). Preparing for the plunge: Pre-service teachers’ assessment literacy. J Sci Teacher Educ, 22, 371-391.

Smith, C. D., Worsfold, K., Davies, L., Fisher, R., & McPhail, R. (2013). Assessment literacy and student learning: the case for explicitly developing students’ assessment literacy. Assessment and evaluation in higher education, 38(1), 44-60.

Stiggins, R.J. (1988). Revitalizing classroom assessment: The highest instructional priority. Phi Delta Kappan, 69, 363-368.

Stiggins, R. J. (1991). Assessment literacy. Phi Delta Kappan, 72, 534-539.

Stiggins, R. J. (1995). Assessment literacy for the 21st century. Phi Delta Kappa, 77(3), 238-245.

Stiggins, R. J. (1999). Evaluating classroom assessment training in teacher education programs. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 23-27

Stiggins, R. J. (2006). Assessment for learning: A key to student motivation and learning. Phi Delta Kappa Edge, 2 (2), 1-19.

Taylor, L. (2009). Developing assessment literacy. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 29, 21-36.

Taylor, L. (2013). Communicating the theory, practice and principles of language testing to test stakeholders: Some reflections. Language testing, 30(3), 403-412.

Thomas, J., Allman, C., & Beech, M. (2004). Assessment for the diverse classroom: A handbook for teachers. Tallahassee, FL: Florida Department of Education, Bureau of Exceptional Education and Student Services. Retrieved from http://www.fldoe.org/ese/pdf/assess_diverse.pdf

Wang, T.H., Wang, K. H. & Huang, S.C. (2008). Designing a web-based assessment environment for improving pre-service teacher assessment literacy. Computers & Education, 51, 448-462.

White, E. (2009). Are you assessment literate? Some fundamental questions regarding effective classroom-based assessment. OnCue Journal, 30(1), 3-25.

Yamtim, V., & Wongwanich, S. (2014). A study of classroom assessment literacy of primary school teachers. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 116, 2998-3004.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a09

TEACHING ISSUES

A call for language assessment literacy in the education and development of teachers of English as a foreign language

Un llamado al desarrollo de la competencia en evaluación de idiomas a través de los procesos formativos de profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera

Leonardo Herrera Mosquera1 Diego Fernando Macías V.2

1 Universidad Surcolombiana, Huila, Colombia. leonardo.herrera@usco.edu.co

2

Universidad Surcolombiana, Huila, Colombia. diego.macias@usco.edu.co

Received: 14-Apr-2015 / Accepted: 31-Aug-2015

Abstract

Even though assessment constitutes an essential component of any educational process, many teachers seem to ignore its multiple implications and manifestations. Assessment continues to be regarded mainly as the summative evaluation which informs teachers of students’ success or failure in their learning process based on a numeric scale. This narrowed approach may be due in part to the lack of preparation and training both in teacher education and professional development programs. This paper thus aims to raise awareness of the relevance of Language Assessment Literacy (henceforth LAL) in the field of teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL) by examining some definitions of assessment, reviewing various studies in the area, analysing some models and alternatives for the evaluation and development of LAL in EFL teaching, and finally, offering conclusions and recommendations for the development of LAL among EFL teachers to better serve the needs of their students and their institutions.

Keywords: Assessment, Assessment Literacy, EFL teachers, English language teachingResumen

Aun cuando la evaluación constituye un componente esencial de cualquier proceso educativo, muchos docentes parecen ignorar sus múltiples implicaciones y manifestaciones. La evaluación continúa viéndose como el tipo de evaluación sumativa, la cual le proporciona al profesor información sobre el éxito o fracaso de sus estudiantes en el proceso de aprendizaje basado en una escala numérica. Este enfoque simplista puede tener su origen en parte a la falta de preparación y capacitación tanto en los programas de licenciatura como en los de desarrollo profesional de docentes. El propósito de este artículo es entonces suscitar conciencia frente al desarrollo de la Competencia en Evaluación de Lenguas (en adelante LAL, por sus siglas en inglés) en el campo de la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera mediante la revisión de algunas definiciones de evaluación así como de varios estudios en el área, el análisis de algunos modelos y alternativas para la evaluación y el desarrollo de LAL en el campo de la enseñanza de inglés; y finalmente, ofrecer conclusiones y recomendaciones para el desarrollo de LAL entre docentes de inglés como lengua extranjera de tal manera que ellos puedan calificarse y así responder más acertadamente a las necesidades de sus estudiantes y sus instituciones.

Palabras clave: Evaluación, Competencia en Evaluación, Docentes de Inglés como Lengua Extranjera, Enseñanza de InglésIntroduction

Assessment has traditionally played a relevant role in the process of teaching and learning not only in English language education, but across most fields of study. It is, together with teachers, students, resources and context, among the five components that contribute to determining the quality of instruction (Yamtim & Wongwanich, 2014). Good assessment practices benefit both students and teachers in several ways: They give information to help teachers determine the appropriateness of content and the pace of the lesson, they help teachers monitor student learning throughout the course, they provide information in regards to the effectiveness of particular teaching methods, they help students monitor their own progress and understanding, and they help build student confidence in preparation for national standardized tests (Thomas, Allman, & Beech, 2004).

Teachers are therefore expected to have a working knowledge of all aspects of assessment to support their instruction and to effectively respond to the needs and expectations of students, parents, and the school community. This, however, does not seem to be the case in many contexts worldwide where teachers and society at large have come to think of assessment as giving students tests and using scores for sometimes unfair purposes and actions such as evaluating teachers’ overall performance, “determining who passes or fails a course, controlling discipline, or threatening students” (López, 2008, p. 56). Bryan and Clegg (2006) also stated that “assessment has been seen almost exclusively as an act of measurement that occurs after learning has been completed, not as a fundamental part of teaching and learning itself” (p. xviii). Many teachers know little or, as Popham (2004) claims, reside in blissful ignorance about educational assessment. To further add to this problem, teachers’ classroom assessment practices are often not supervised by knowledgeable curriculum and evaluation experts once they start teaching in real school settings.

Brown and Abeywickrama (2010) make the point that in language assessment, tests usually provoke anxiety and self-doubt for language learners, while many teachers do not seem to like the assessment part of their job and end up designing tests that do not meet principles of effective classroom assessment. In this sense, Malone (2011) and Brown and Abeywickrama (2010) highlight principles such as practicality, reliability, validity, authenticity, and washback, that is, the impact that tests have on instruction, as useful guidelines for the evaluation and design of assessment tools for the language classroom.

Despite the widespread rhetoric about the importance of assessment in the teaching and learning processes in the last few decades, many teachers lack knowledge, experience, and confidence in aspects related to language assessment Nunan, 1988). In examining assessment education at a pre-service teacher education program in Canada, DeLuca and Klinger (2010) advocated for direct instruction in topics such as “reporting achievement, modifying assessments, developing constructed-response items, item reliability, validity, and articulating a philosophy of assessment” (p. 432). It is relevant then to consider that developing LAL among EFL teachers must be a necessary component of foreign language teacher education programs. López and Bernal (2009) also argue for more training in language assessment for prospective teachers. These authors feel that the responsibility to train language teachers in how to develop, use, score and interpret language assessments lies in teacher education programs in higher education institutions. Perhaps the most serious concern derived from this situation is that without greater LAL competence, language teachers will be less likely to help students attain higher levels of academic achievement (Coombe, Davidson, Sullivan, & Stoynoff, 2012).

This paper calls for more preparation and development opportunities in LAL for EFL teachers and aims to raise awareness of the importance of LAL in the field of foreign language education. We will initially provide a definition of assessment literacy, discuss its relevance for EFL teaching, and consider how it has been addressed through teacher preparation programs. Next, we will review some of the studies that have been conducted in the area of assessment literacy in general and LAL in particular, and briefly refer to what constitutes the knowledge base that language teachers, including EFL teachers, need to develop. Then, we will look at some models and alternatives for the evaluation and development of LAL in EFL teaching, and propose an instrument that may serve to diagnose foreign language teachers’ assessment literacy. Finally, we will offer some conclusions and recommendations for the development of LAL among EFL teachers so that they can better address assessment-related issues in their classrooms.

What is Assessment Literacy?

Before looking into LAL, it is relevant here to consider the definition of assessment literacy from a general education perspective as it would help us understand its role across different subjects or fields of study including the teaching and learning of English as a Foreign Language. Fulcher (2012) states that the earliest attempt to define assessment literacy for teachers was made by the American Federation of Teachers (1990) and it included competencies in “selecting and developing assessments for the classroom, administering and scoring tests, using scores to aid instructional decisions, communicating results to stakeholders, and being aware of inappropriate and unethical uses of tests” (Fulcher, 2012, p. 115). Soon after, Stiggins (1991) defined assessment literacy as “having a basic understanding of the meaning of high- and low-quality assessment and being able to apply that knowledge to various measures of student achievement” (p. 535). In a related article, Stiggins (1995) argued that assessment experts typically know what and why they are assessing, how best to assess students’ achievements, how to generate sound samples of performance, what can go wrong, and how to prevent assessment-related problems before they occur. More recently, Siegel and Wissehr (2011) expanded on this definition by proposing that “teachers need both an understanding of theory, or theoretical principles for assessment, and practice, or practical methods of use in a classroom” (p. 373). The previous definitions of assessment literacy represent a tiny sample of the plethora of those available in the literature. From those definitions, we consider that assessment literacy refers to having theoretical and practical knowledge, and overall competence in all aspects related to the assessment of students’ learning. Such aspects may include, but are not limited to, the design, administration, grading, evaluation, and impact of all types of alternatives for classroom and large-scale assessments.It is equally relevant to make reference to the concepts of classroom assessments and accountability assessments as a framework for the promotion of assessment literacy. According to Popham (2009), classroom assessments refer to those formal and informal procedures used by teachers in an effort to make accurate inferences about what their students know and can do. These assessments are traditionally constructed by teachers or provided by textbooks or external institutions, and used to grade student progress. In contrast, accountability assessments are those “measurement devices, almost always standardized, used by governmental entities such as states, provinces, or school districts to ascertain the effectiveness of educational endeavors” (Popham, 2009, p. 6). Popham (2009) also argued that teachers require knowledge of both classroom and accountability assessments, and highlighted that although the latter are usually controlled by high- level governmental officials, accountability testing has an impact on teachers since in many cases they are evaluated based on their students’ scores on those tests. Part of teachers’ reluctance to scrutinize educational accountability originates from their inability or limited experience to evaluate the quality of those tests (Popham, 2009). In fact, “teachers’ serious confrontations with accountability-related assessment are almost as rare as their encounters with extraterrestrial parents during back-to-school night” (Popham, 2004, p. 82). Developing expertise in aspects such as interpreting and communicating results of standardized examinations to students and parents, and establishing the fit between large-scale examinations and classroom assessment practices should then be of great concern for language educators including EFL teachers.

Language Assessment Literacy

Scarino (2013) urges teachers to develop language assessment literacy (LAL) that enables them to explore and evaluate their own preconceptions, to understand the interpretive nature of the phenomenon of assessment and to become increasingly aware of their own dynamic framework of knowledge, understanding, practices, and values. It is through these processes, adds Scarino, that language teachers will gradually develop self-awareness as assessors, an integral part of their LAL. Davies (2008 cited in Malone, 2013) similarly describes LAL as being composed of skills (the how-to or basic testing expertise), knowledge (information about measurement and about language), and principles (concepts underlying testing such as validity, reliability, and ethics); whereas Taylor (2009) claims that a complete understanding of these components is essential for effective LAL. Hence, EFL teachers are encouraged to develop their theoretical and practical assessment knowledge base related to their teaching and students’ learning processes.

High LAL competence should enable EFL teachers to design appropriate assessments, select from a wider repertoire of assessment alternatives, critically examine the impact of standardized tests (e.g. TOEFL, IELTS, etc.), and establish a solid connection between their language teaching approaches and assessment practices. Malone (2011) calls for the integration of instruction and assessment to inform and improve one another. However, this is very unlikely to happen when EFL teachers do not have adequate foundations in LAL.

In regards to how assessment has been addressed in language teacher preparation, Scarino (2013) stresses the need to expand teachers’ understanding of LAL while including the perceptions that the teachers themselves bring to the teaching and assessment encounter. Interestingly, Stiggins (2006) also claimed, from a more general education perspective, that the lack of assessment literacy among teachers is due to the fact that in many undergraduate teacher education programs, teachers were not required to learn anything about educational assessment. They were merely exposed to some concepts and practices of educational assessment in just a few sessions in their educational psychology classes or, a unit in the methods courses. This might serve to illustrate the situation in many EFL teacher education programs in Colombia where language assessment preparation from theoretical and practical perspectives appears to be limited to one or two units in the methods courses. López and Bernal (2009) reviewed the curricula of 27 undergraduate teacher education programs in modern languages (e.g. English, Spanish, French) in Colombia and found that just seven of the programs included a course in evaluation. The authors similarly claimed that the situation becomes even more worrisome considering that only two of the seven aforementioned programs correspond to the type of public universities where the majority of Colombian EFL teachers are trained.

All in all, assessment literacy is a skill needed by teachers for their own long-term professional well-being, to benefit their students and programs or institutions in which they work (Popham, 2009). It follows that a central concern for EFL teachers should be the enhancement of their assessment- related knowledge. However, we do not believe that the solution to help EFL teachers develop LAL lies in offering a course in assessment with an appropriate text as suggested by Popham (2011). Although helpful, it is clearly not enough. Other alternatives in the form of workshops, conferences, independent readings, study groups, and collaborative action research among other projects should be implemented within the teacher education program curriculum or as professional development alternatives. As pointed out by Fulcher (2012), “research into assessment literacy is in its infancy” (p. 117) so the relevance and impact of LAL for language teachers and students has been the subject of very few studies across multiple contexts. Let us now look at some contributions they have made toward the development of assessment literacy in language education in general and in EFL teaching in particular.

Studies on LAL in Teacher Education

As mentioned earlier, Popham (2009) argued that today’s teachers know little about educational assessment. For some, “test is a four-letter word, both literally and figuratively” (p. 5). Competence in accountability assessments, for example, is of special significance in view of the need for EFL teachers to engage critically with required national and international English curriculum and tests. The Colombian National Bilingual Programme constitutes a clear example of the need to develop EFL teachers’ LAL in view of the three main axes (EFL assessment, language competence standards, and professional development plans) that this national bilingual program emphasizes (Programa Nacional de Bilingüísmo Colombia, 2004-2019). Fulcher (2012) also states that accountability tests “are used in political systems to manipulate the behaviour of teachers and hold them accountable for much wider policy goals” (p. 114). EFL teachers should then be encouraged to examine the impact of such tests for their local contexts and for the lives of their students especially when those tests become gatekeepers for higher education opportunities for many high school or college graduates. In another study, Jeong (2013) compared language testers (professionals with a primary research interest in areas of language testing) and non-language testers (those whose primary interest is in other areas of language teaching) teaching language assessment courses and found significant differences in six topic areas in such courses (test specifications, test theory, basic statistics, classroom assessment, rubric development, and test accommodation) depending on who was teaching them. She called for a common understanding of LAL among language testers and non-language testers who teach language assessment courses.

Fulcher (2012) used a survey instrument to elicit the assessment training needs of 278 international language teachers. His findings led to the construction of a working definition of assessment literacy (See below), which clearly challenges other definitions widely used in the existing literature including those we mentioned earlier in this paper.

The knowledge, skills and abilities required to design, develop, maintain or evaluate, large- scale standardized and/or classroom based tests, familiarity with test processes, and awareness of principles and concepts that guide and underpin practice, including ethics and codes of practice. The ability to place knowledge, skills, processes, principles and concepts within wider historical, social, political and philosophical frameworks in order to understand why practices have arisen as they have, and to evaluate the role and impact of testing on society, institutions, and individuals. (Fulcher, 2012, p. 125)

As can be observed, the above definition leads to a much broader approach to assessment literacy in EFL teaching and learning— one that integrates knowledge, skills, and principles in a way that seeks to balance both classroom and accountability assessments.

Many other predominantly conceptual articles (Boyles, 2006; Popham, 2009, 2011; Schafer, 1993; Taylor, 2009; White, 2009) have suggested that teachers pay more attention to the issue of assessment literacy in their professional development. Popham (2009) in particular argues that teachers’ scarce knowledge of classroom and accountability assessments “can cripple the quality of education” (p. 4). He believes that assessment literacy should be an indispensable competency for today’s teachers and the focus of current and future staff development endeavors. An equally relevant issue relates to the knowledge base of assessment, that is, the knowledge or specific content and skills that teachers are supposed to have in terms of assessment.

EFL Teachers’ Assessment Knowledge Base

The knowledge base in the case of language assessment makes reference to the body of theoretical and practical knowledge that language teachers including EFL teachers require in relation to aspects such as the purpose of assessment, the appropriateness of the assessment tools being used, the testing conditions, the interpretation and implications of results, etc. In following an outline proposed by Brindley (2001), Inbar- Lourie (2008) emphasized aspects such as “the reasoning or rationale for assessment (the ‘why’), the description of the trait to be assessed (the ‘what’), and the assessment process (the ‘how’)” (p. 390) as the assessment knowledge dimensions language teachers require. Other authors (Popham, 2009; Schafer, 1993;Stiggins, 1999) have also attempted to define what constitutes the knowledge base of assessment for teachers across various areas including EFL education.Stiggins (1999) suggested a list of seven content requirements or competences aimed to provide a comprehensive foundation in assessment practices. These included (a) connecting assessments to clear purposes, (b) clarifying achievement expectations, (c) applying proper assessment methods, (d) developing quality assessment exercises and scoring criteria and sampling appropriately, (e) avoiding bias in assessment, (f) communicating effectively about student achievement, and (g) using assessment as an instructional intervention. Training within these seven competencies will undoubtedly bring significant benefits not only to our EFL teachers, in the sense that they will have a clearer picture of what students may know (declarative knowledge) and what they can do (procedural knowledge), but also to their EFL students in the sense that they may be provided with more reliable assessment instruments, practices, and conditions. Thus, even though the seven competencies are originally formulated within an ELL context, they all can be smoothly transferred to other settings such as that of EFL instruction in Colombia.

Schafer (1993) similarly makes reference to a series of standards for teacher competence in the educational assessment of students. Accordingly, teachers need to be skilled in aspects such as choosing and developing appropriate assessment methods for instructional decisions; administering, scoring, and interpreting assessment results to make decisions for planning and improving teaching; developing valid grading procedures; communicating results to students, parents, and others; and recognizing unethical or inappropriate methods and uses of assessment. These standards, constructed by the American Federation of Teachers, the National Council on Measurement in Education, and the National Education Association (1990), embrace the concept that assessment and instruction are reciprocally linked and that effective instruction cannot occur without good assessment of learning.

More recently, Popham (2009) also advocates for the inclusion of assessment-related content in teacher development programs. Such content may consist of the function and reliability of educational assessments; issues of validity to support test-based interpretations of students’ learning; the elimination of assessment bias that offends or unfairly penalizes test-takers because of personal characteristics (e.g. gender, race, cultural or socioeconomic status); the construction and scoring of test items and other types of assessment (e.g., portfolio assessments, peer assessments, etc.); the design and implementation of formative assessment procedures; the preparation of learners for high-stakes tests, the interpretation of their performances on such tests, and the suitability of accountability tests for evaluating the quality of instruction.

The previous competencies, standards, and aspects surely apply to all fields of teacher education including EFL teaching. Such competencies and standards may also serve to help teacher educators in Colombia to examine whether or not they are preparing EFL teachers with a sound foundation in the most relevant aspects of assessment and to design professional development initiatives that effectively strengthen teachers’ assessment knowledge base. As can be inferred from the preceding sections, LAL has been receiving more attention currently than in the past. However, it should be the personal commitment of EFL teachers to get involved in professional development opportunities to enhance their LAL, and the responsibility of teacher educators to constantly design and offer alternatives to help EFL teachers strengthen their understanding and applications of assessment literacy.

The Evaluation and Development of EFL Teachers’ LAL

Interestingly, Malone (2008) claims that more training alone is insufficient to meet the language assessment training needs. It is important that such training “includes the necessary content for language instructors to apply what they have learned in the classroom and understand the available resources to supplement their formal training when they enter the classroom” (p. 235). It is necessary to reiterate here that EFL teacher education and professional development programs must provide teachers with relevant preparation in LAL. Nonetheless, such initial preparation should be complemented by on-going training that regularly updates in-service teachers in current innovations in LAL and facilitates their incorporation into their own teaching practices.

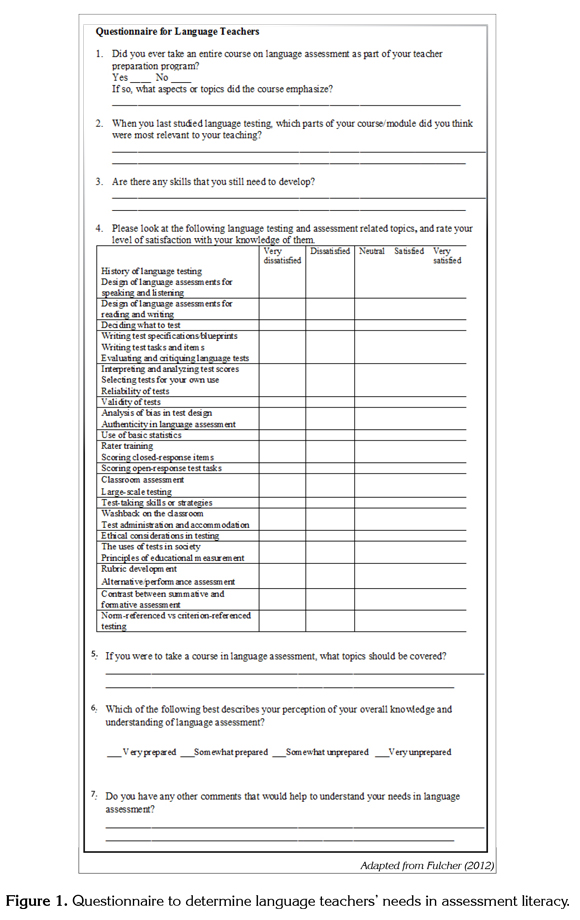

In order to help teacher educators determine EFL teachers’ current knowledge and awareness of the many aspects that are involved in LAL, we suggest here a questionnaire See Figure 1 that may be used to diagnose the needs regarding assessment literacy of not only EFL teachers but language teachers in general. The questionnaire, which has been adapted from Fulcher (2012), may serve to inform teacher educators or government agencies about language teachers’ needs in assessment. The questionnaire has been modified to cover aspects related to both classroom and accountability assessments together with various competences and standards that should constitute the assessment knowledge base of language teachers. It must be noted that this questionnaire has been revised so that it provides an accurate view of language teachers’ level of satisfaction with their language assessment competence. Specifically, the initial open-response questions are meant to elicit EFL teachers’ prior experiences and views on assessment. Consequently, these initial questions have been purposefully located before the closed-ended items in the questionnaire, which cover a greater repertoire of aspects that teachers may or may not be aware of in regards to language assessment. Unlike Fulcher’s survey, which sought to elicit the level of importance of assessment- related topics that should be included in a course on language testing, the adapted questionnaire is suggested as a tool to help determine language teachers’ level of awareness or satisfaction with their current knowledge and understanding of LAL.

Eventually, results obtained through the questionnaire may support the implementation of strategies (e.g. conferences, workshops, lectures, action research projects, etc.) aimed to strengthen language teachers’ assessment literacy. In this sense, Boyles (2006) claims that in order to develop assessment literacy, foreign language professionals require a toolbox filled with skills and strategies that will enable them to decipher assessment results, analyse their meaning, respond to what the results reveal, and apply them in teaching and in program evaluation.

It is clearly not our goal here to promote the view of a single strategy to examine or determine EFL teachers’ expertise in assessment. The questionnaire above constitutes just one possible alternative to obtain an initial view of language teachers’ assessment literacy. Eventual results of the questionnaire should not be seen as conclusive given that they rely exclusively on teachers’ self- reports. We consider that the initial results from the questionnaire could be confirmed through other data collection means such as focus group interviews, classroom observation, or reflection logs. These other different mechanisms will contribute to provide a portrayal of EFL teachers’ language assessment competences and needs.

Stiggins (1999) offers a list of options through which assessment literacy can be developed. For example, a unit or multiple units on assessment in various courses (e.g. methods courses, educational psychology course, curriculum design, introduction to teaching), a separate course or set of courses on assessment methods, independent study in assessment, a program of assessment training taught by professors who model various methods, and instruction provided by an assessment-literate master teacher during student teaching.

We would similarly advocate that good practices in EFL assessment should be modelled by teacher educators throughout the program curriculum, making explicit assessment expertise in the courses. In this way, prospective EFL teachers will recognize the assessment practices teacher educators use and will start building their personal knowledge base of language assessment as informed by their experiences in EFL teacher education programs and by the content of assessment courses. Such personal knowledge base has the potential to be progressively refined as they advance in their careers as in-service language teachers. Stiggins (1988) reported that teachers cited their colleagues and their experience as students as the key sources of the assessment strategies they currently use. Nevertheless, EFL teachers need to be cautious about uncritically adopting potentially inappropriate assessment practices since “naïve misuses of assessment serve as models of assessment practice for persons preparing to become teachers, instructors, and professors” (Schafer, 1993, p. 123).

Conclusions and Recommendations

In this paper, our goal has been to raise awareness for more preparation in assessment for language teachers including EFL teachers in Colombia. We have offered several definitions of assessment literacy from a general education perspective and from the point of view of language education, discussed its relevance for EFL teaching, briefly analysed some studies in the area of language assessment literacy, considered what constitutes the knowledge base of language assessment, and adapted a questionnaire (based on Fulcher, 2012) that can be used to determine assessment literacy needs and competences among EFL teachers.

What we have learned from our experiences is that beginning EFL teachers usually focus on the accuracy of the instrument (e.g. test, exam) they intend to use to assess student learning in an attempt to make sure that the tasks and items convey clear meaning and instructions. Not surprisingly, many EFL teachers in Colombia do not seem to realize that this is just a small part of a larger picture in language assessment that teachers must be aware of in the process of becoming assessment literate. Stiggins (2007) claimed that while research indicates that “teachers spend as much as one- quarter to one-third of their available professional time in assessment-related activities, almost all do so without the benefit of having learned the principles of sound assessment practice” (p. 10). It follows that assessment practices should be given the same importance that instructional practices usually receive in teacher preparation coursework. There should be a clear set of goals to facilitate EFL teachers’ acquisition of skills, knowledge, and competencies in assessment.

Although we found various studies that addressed the issue of language assessment literacy, more research is needed not only to determine EFL teachers’ competence of assessment literacy but also to devise ways or mechanisms to help beginning and experienced language teachers develop expertise in all aspects of language assessment so that they can better serve the needs of their students and their institutions. Taylor (2013) claims that outcomes from empirical research investigating the nature and development of LAL are urgently needed not just to inform and reinforce existing policy and practice but also to inspire and shape new initiatives for disseminating core knowledge and expertise in language assessment to a growing range of test stakeholders (p. 405).

Language teacher education programs must include alternatives to help EFL teachers gain a broader working knowledge of assessment literacy. In this regard, developing LAL should not be just a common concern for beginning EFL teachers but a personal and professional commitment for more experienced teachers as part of their lifelong learning. It must be highlighted here that training in LAL should not be reduced to a single course in initial teacher education programs. We believe that the development of LAL has to be a fundamental subject in initial teacher education programs in foreign languages, a perennial topic at the annual meetings of professional language teacher associations, and a sustained collaborative effort accompanied by the implementation of successful assessment practices and resources in schools.

Last but not least, the development of LAL must be supported by pedagogical knowledge about teaching and learning so that teachers’ decisions are not simply driven by a series of technical prescriptions. EFL teachers’ decisions and actions in regards to language assessment should be informed by the circumstances of their immediate context and the quality of their teaching. As claimed by Engelsen and Smith (2014), “the quality of practice is to a large extent directed by the practitioner’s assessment knowledge and skills; in other words, by the practitioner’s assessment literacy” (p. 92).

References

American Federation of Teachers, National Council on Measurement in Education, & National Education Association (AFT, NCME, & NEA). (1990). Standards for teacher competence in educational assessment of students. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 9(4), 30-32.

Boyles, P. (2006). Assessment literacy. In M. Harmon (Ed.) New visions in action national assessment summit papers. Iowa State University, IO.

Brindley, G. (2001). Language assessment and professional development. In C. Elder, A.Brown, K. Hill, N. Iwashita, T. Lumley, T. McNamara, & K. O’Loughlin (Eds.), Experimenting with uncertainty: Essays in honour of Alan Davies (pp. 126-136). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Brown, D., & Abeywickrama, T. (2010). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices. New York: Pearson Longman.

Bryan, C., & Clegg, K. (Eds.). (2006). Innovative assessment in higher education. New York: Routledge.

Coombe, C., Davidson, P., Sullivan, B., & Stoynoff, S. (2012). The Cambridge guide to second language assessment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, A. (2008). Textbook trends in teaching language testing. Language Testing, 25(3): 327–347.

DeLuca, C., & Klinger, D. (2010). Assessment literacy development: Identifying gaps in teacher candidates’ learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17(4), 419-438.

Engelsen, K. S., & Smith, K. (2014). Assessment literacy. In C. Wyatt-Smith, V. Klenowski, & P. Colbert (Eds.), Designing assessment for quality learning (pp. 91- 108). New York: Springer.

Fulcher, G. (2012). Assessment literacy for the language classroom. Language Assessment Quarterly, 9(2), 113–132.

Inbar-Lourie, O. (2008). Constructing a language assessment knowledge base: A focus on language assessment courses. Language Testing, 25(3), 385-402.

Jeong, H. (2013). Defining assessment literacy: Is it different for language testers and non-language testers? Language Testing, 30(3), 345-362.

López, A. A. (2008). Potential impact of language tests: Examining the alignment between testing and instruction. Saarbrucken: Vdm Publishing.

López, A., & Bernal, R. (2009). Language testing in Colombia: A call for more teacher education and teacher training in language assessment. Profile: Issues in Teachers’Professional Development, 11(2), 55-70.

Malone, M. (2008). Training in language assessment. In E. Shohamy & N. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education: Vol. 7. Language testing and assessment (2nd ed., pp. 225-239). New York: Springer Science+Business Media.

Malone, M. (2011). Assessment literacy for language educators. CALDigest, October, pp. 1-2

Malone, M. (2013). The essentials of assessment literacy: Contrasts between testers and users. Language Testing, 30(3), 329-344.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia (n.d.). Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo, 2004-2019. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/articles-132560_recurso_pdf_programa_nacional_ bilinguismo.pdf

Nunan, D. (1988). The learner centred curriculum. A study in second language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Popham, W. J. (2004). Why assessment illiteracy is professional suicide. Educational Leadership, 62(1), 82-83.

Popham, W. J. (2009). Assessment literacy for teachers: Faddish or fundamental? Theory Into Practice, 48(1), 4-11.

Popham, W. J. (2011). Assessment literacy overlooked: A teacher educator’s confession. The Teacher Educator, 46, 265-273.

Scarino, A. (2013). Language assessment literacy as self- awareness: Understanding the role of interpretation in assessment and in teacher learning. Language Testing, 30(3), 309-327.

Schafer, W. D. (1993). Assessment literacy for teachers. Theory into Practice, 32(2), 118-126.

Siegel, M., & Wissehr, C. (2011). Preparing for the plunge: Pre-service teachers’ assessment literacy. J Sci Teacher Educ, 22, 371-391.

Stiggins, R. J. (1988). Revitalizing classroom assessment: The highest instructional priority. Phi Delta Kappan, 69, 363-368.

Stiggins, R. J. (1991). Assessment literacy. Phi Delta Kappan, 72, 534-539.

Stiggins, R. J. (1995). Assessment literacy for the 21stcentury. Phi Delta Kappa, 77(3), 238-245.

Stiggins, R. J. (1999). Evaluating classroom assessment training in teacher education programs. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 18(1), 23-27.

Stiggins, R. J. (2006). Assessment for learning: A key to student motivation and learning. Phi Delta Kappa Edge, 2(2), 1-19.

Stiggins, R. J. (2007). Conquering the formative assessment frontier. In J. McMillian (Ed.), Formative classroom assessment (pp. 8-28). New York: Columbia University Teachers College Press.

Taylor, L. (2009). Developing assessment literacy. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 29, 21-36.

Taylor, L. (2013). Communicating the theory, practice and principles of language testing to test stakeholders: Some reflections. Language testing, 30(3), 403-412.

Thomas, J., Allman, C., & Beech, M. (2004). Assessment for the diverse classroom: A handbook for teachers. Tallahassee, FL: Florida Department of Education, Bureau of Exceptional Education and Student Services. Retrieved from http://www.fldoe.org/ese/pdf/assess_diverse.pdf

White, E. (2009). Are you assessment literate? Some fundamental questions regarding effective classroom- based assessment. OnCue Journal, 30(1), 3-25.

Yamtim, V., & Wongwanich, S. (2014). A study of classroom assessment literacy of primary school teachers. ia: Social and Behavioural Sciences, 116, 2998-3004.

Métricas

Licencia

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/