DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n2.10014Published:

2016-07-18Issue:

Vol 18, No 2 (2016) July-DecemberSection:

Reflections on PraxisOlowalu review: Developing identity through translanguaging in a multilingual literary magazine

Revista Olowalu: El desarrollo de la identidad a través del translingualismo en una revista literaria multilingüe

Keywords:

identidad, la escritura creativa L2, literatura L2, multilingüismo, translanguaging (es).Keywords:

Multilingualism, translanguaging, identity, L2 creative writing, L2 literature (en).Downloads

References

Alim, H. S., Ibrahim, A., & Pennycook, A. (2009). Global linguistic flows: Hip hop cultures, youth identities, and the politics of language. London, UK: Routledge.

Amos, K. (2015). E lei. Olowalu Review 1. Retrived from http://olowalureview.wix.com/olowalureview#!e-lei/cm6k.

Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera. San Francisco, CA: Spinsters / Aunt Lute Book Company.

Baldacci, L. (2015). Calle San Miguel. Olowalu Review 1. Retrieved from http://olowalureview.wix.com/olowalureview#!calle-san-miguel/c208c.

Canagarajah, S. (2011). Translanguaging in the classroom: Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. In L. Wei (Ed.), Applied Linguistics Review, 2 (pp. 1–27). New York, US: Walter de Gruyter.

Canagarajah, S., & Liyanage, I. (2012). Lessons from pre-colonial multilingualism. In M. Martin-Jones, A. Blackledge, & A. Creese (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of multilingualism (pp. 49–65). London, UK: Routledge.

Cenoz, J. (2013). Defining multilingualism. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 33, 3-18.

Davis, K. (2009). Agentive youth research: Towards individual, collective and policy transformations. In T.G. Wiley, J.S. Lee & R. Rumberger (Eds.), The Education of Language Minority Immigrants in the USA (pp. 202–239). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

De Mejía, A.M. (2005). Bilingual education in South America. Buffalo, NY : Multilingual Matters.

Garcia, O. & Wei, L. (2013). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

García, O., Zakharia, Z. & Otcu, B. (2013). Bilingual Community Education for American Children: Beyond Heritage Languages in a Global City. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Hara, T. (2015). Time goes by. Olowalu Review 1. Retreived from http://olowalureview.wix.com/olowalureview#!time-goes-by/ca2w.

Phillipson, R. (2003). English-only Europe?: Challenging language policy. New York: Routledge.

Sayer, P. (2013). Translanguaging, TexMex, and bilingual pedagogy: Emergent bilinguals learning through the vernacular. TESOL Quarterly, 47(1), 63-88.

Skutnabb-Kangas, (2000). Linguistic human rights and teachers of English. In Hall, J.K. & Eggington, W.G. (Eds.), The sociopolitics of English language teaching. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters (pp. 22–44).

Swain, M. (2006). Languaging, Agency and Collaboration in Advanced Second Language Learning in H. Byrnes (Ed.), Advanced Language Learning: The Contributions of Halliday and Vygotsky (pp. 95–108). London, UK: Continuum.

Wei, L. (2010). Moment Analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222-1235.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n2.10014

REFLEXION ON PRAXIS Olowalu Review: Developing identity through

translanguaging in a multilingual literary magazine

Revista Olowalu: El desarrollo de la identidad a través del

translingualismo en una revista literaria multilingüe

Alex Josef Kasula1

Citation/ Para citar este artículo: Kasula, A. J. (2016). Olowalu Review: Developing identity through translanguaging in a multilingual literary magazine.

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 18(2), pp. 109-118.

Received: 27-Jan-2016 / Accepted: 08-Jun-2016 Abstract With the current trends in our globalized society, there is a clear increase in multilingualism; however, the

understanding of multilingual identity and policy towards education stays relatively the same. Recent investigation

in multilingualism in the US has shed light on the positive impacts of alternating policy in language education with

regard to a greater understanding of how translanguaging and identity impact the language learner and language

learning policies (García & Wei, 2013). The following article describes the development of an online multilingual literary

magazine, Olowalu Review, that aimed to provide English language learners in an English-only language policy with

a space to translanguage. Thus, having the opportunity to develop and express their multilingual identities. Goals and

the development of the magazine are described in terms relating to current multilingual theory. While the outcomes and

findings reveal how Olowalu Review enabled multilinguals to foster and exercise multilingual identities and skills, raise

multilingual awareness, and act as an important multilingual artifact through an analysis of written submissions and

interviews with authors. Pedagogical implications are discussed to empower language teachers, learners, or artists to develop the same or similar project for their own local, national, or global community.

Keywords: identity, L2 creative writing, L2 literature, multilingualism, translanguaging. Resumen Con las tendencias actuales en nuestra sociedad globalizada, vemos un aumento en el multilinguismo; sin

embargo, el entendimiento de la identidad y la política multilingüe hacia la educación se mantiene relativamente

igual. Investigaciones recientes en multilingüismo en los EE.UU. ha arrojado luz sobre los impactos positivos de la

alternancia política en el lenguaje educativo con respecto a un mayor entendimiento en cómo el translanguaging y la

identidad impactan al estudiante de idiomas y las politicas de aprendizaje de idiomas (García y Wei, 2013). El siguiente

artículo describe el desarrollo de una revista literaria multilingüe en línea, Olowalu Review, la cual tuvo como objetivo

proporcionar a los estudiantes de inglés en un inglés único de política lingüística en un espacio para translanguage.

De esta manera tener la oportunidad de desarrollar y expresar sus identidades multilingües. Las metas y el desarrollo

de la revista se describieron en términos relativos a la teoría multilingüe actual. Si bien los resultados y hallazgos

revelan cómo Olowalu Review se habilitó multilingüe para fomentar y ejercer las identidades y habilidades multilingües,

aumentar el conocimiento multilingüe y actuar como un importante artefacto multilingüe a través de un análisis de las comunicaciones escritas y entrevistas con los autores. Las implicaciones pedagógicas se discutieron para permitir a

los profesores de idiomas, estudiantes o artistas desarrollar el mismo o un proyecto similar para su propia comunidad local, nacional o global. Palabras clave: identidad, la escritura creativa L2, literatura L2, multilingüismo, translanguaging. Introduction As the understanding of multilingualism in the

growing globalized society and in the language

learning classroom begins to expand, there is a

clear need for teachers, students, and policy to

understand how this effects the identities of learners

and speakers of more than one language. The ideas

of national languages are beginning to diminish,

as the global flow of people and information is

more rapid than ever, making a visible path for a

stronger role of multilingualism in language learning

classrooms. The work of García, Zakharia, and Otcu

(2013) reveals how in falsely understood monolingual

societies like New York City, U.S.A., being a

multilingual is common and the need for education

to be a reflection of the identities of those who are

learning and teaching. Multilingualism expands

beyond just that of super-diverse communities like

seen in New York City, but also throughout the world

as language requirements are becoming a core part

of educational curriculum. There is a clear demand for pedagogy and

course design to meet the ever-changing identities

of multilingual language learners. Therefore, a

distinct understanding of what is 'multilingualism’

is necessary for all stakeholders in language

learning to comprehend in order to progress

the ways of teaching and learning to sufficiently

reach the rapidly changing language use of the

learners. Cenoz (2013) describes the holistic view

of multilingualism in which multilingual speakers

use their linguistic resources in ways that are

different from the way monolingual speakers use

single languages. Although a number of more

specific definitions have stemmed from a general

understanding of multilingualism, the current

definition adequately depicts multilingualism

in the context of translanguaging and the

pedagogical implications this article aims to

provide the readers. The following article will discuss how the

development of an online multilingual literary

magazine for English language learners can act

as an effective outlet for multilinguals or emerging

multilinguals to express their multiple identities,

while also providing the opportunity for learners

to exercise the language skills they are learning.

To understand how to approach multilingualism in

the English language learning (ELL) classroom, it

is vital to grasp what is occurring with multilinguals

in regards to their self-identity and how this can be

expressed in class activities beyond what occurs

directly in the classroom. Identity and Translanguaging A number of societies and populations around

the world are multilingual; a clear example are the

urban dwellings in the U.S. that hold a large diversity

of multilingual speakers (see García, Zakharia, &

Otcu, 2013 for a list of languages spoken other than

English in New York City). Multilingualism expands

beyond the U.S. as globalization demands citizens

from all nations to acquire a second language,

primarily languages of former imperialistic societies,

such as English, French, Spanish, Mandarin Chinese,

and so on. This does not account for societies

across the world that practiced multilingualism prior

to global colonialism and modern globalization (see

Canagarajah & Liyanage, 2012, for a more elaborate

discussion). With an increase in multilingualism

throughout the world, the questions of "how do these

multilinguals communicate?"; "how do multilinguals

manage the uses of their multiple languages?";

and "how do multilinguals use language to identify

themselves?" begin to emerge. Translanguaging

is a social concept that aims to discuss the use of

language among multilinguals, and is a common

phenomenon among multilinguals playing a

fundamental role in terms of communication,

identity, and power. Translanguaging is an approach

to the use of language that considers the language

practices of multilinguals not as using two or

more autonomous language systems as has been

traditionally the case, but as one linguistic repertoire

with features that have been societally constructed

as belonging to two separate languages (García

& Wei, 2013). For a visible contextualization of

translanguaging in literature see Excerpt 3. Translanguaging is a common phenomenon for

multilinguals, at points feeling the most natural form

of communication or expression. Translanguaging

acknowledges the multiple identities and languages

of its speakers through creating a space where

values, culture, language, and history can be

expressed. In this space, one is languaging, which

is the process to gain knowledge, make sense, or

communicate by putting one’s thought into actual

form (Swain, 2006; Wei, 2010). Wei continues to

describe how the translanguaging space "is not a

space where different identities, values and practices

simply co-exist, but combine together to generate

new identities, values and practices" (p. 1223).

Although this space is fluid and ever changing for

those who inhabit it, it provides the opportunity for

expression of multilinguals, as many multilingual

environments are falsely perceived as monolingual.

A clear example is in the U.S. education system.

Although multilinguals make up a large portion

of students attending public schools in the U.S.,

many are forced into speaking in English through

the "English-only" policy, and in turn multilinguals

are put at a disadvantage, inevitably forced into

circumstances where their linguistic identities and

translanguaging space are suppressed (García,

Zakharia, & Otcu, 2013). The use of "Englishonly"

policies extends beyond languages where

English remains understood as national language.

English-only policies, or monolingual polices, can

be found across language learning environments

geographically and linguistically, with clear examples

in Europe (Phillipson, 2003) and South America (De

Mejía, 2005). Nevertheless, when multilinguals and their

identities are accepted, appreciated, and heard,

these multilinguals become empowered, fostering

the equity needed in democratic societies (see

Davis, 2009, for an example of empowering

multilingual youth). The ability to use the full

linguistic repertoire through translanguaging and

abolish the enslavement of multilinguals into one

"standard" language space not only promotes

equity and appreciation of cultural differences but

can also be viewed as an innate right. Phillipson

(1998) describes how multilingualism strongly

connects with human rights by allowing speakers

to express their linguistic diversity and counteract

linguistic dominance. It is the responsibility of the

stakeholders in language education to transform or

provide space for translanguaging as it not only can

be a useful resource for learning and communicating

but also help foster identities of learners, promoting

a more democratic and equal environment. Offering

opportunities to translanguage gives voice to those

who are marginalized, to those still wandering the

borderlands of language. Translanguaging Theory to Practice Although translanguaging is a rather new

term in the field of linguistics, it has long been

a method of expression for those living within

multilingual communities. The work of Gloria

Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New

Mestiza (1987), describes the lives of multilinguals

living on the "borderlands" of society through her

poetry and short essays. She, a Latina bilingual in

Spanish and English near the Mexico-U.S. border,

translanguages to express the lives of people within

her multilingual community. In Anzaldúa’s work a

strong focus is on the individuals in the borderlands

and the perplexity with their identity and sentiment of

living on the fringes of two societies, not being fully

accepted into one, or the other. Providing the space

for translanguaging of language learning students

could not only erase the borders felt in Anzaldua’s

work but also be the place to foster new identities

and opportunities to learn. As mentioned above, there may be initial

negative recoil from the misunderstood genuineness

of translanguaging, specifically where monolingual

policies are strict. García, Zakharia, and Otcu (2013)

clearly displays how teachers can become facilitators

of translanguaging spaces in the classroom, even if

they are unfamiliar with the students’ first language

(L1) or second language (L2). García, Zakharia,

and Otcu also illustrate the positive effects of

a translanguaging space, where students and

community feel more involved and exceed the

standards of the class. By giving the opportunity

to express language through translanguaging,

leaners have the ability to draw on resources from

any language in their linguistic repertoire and

feel comfortable using these resources (García,

Zakharia, & Otcu, 2013). Although there is not a

sufficient claim that translanguaging will increase

language "skill", it does open the door for practicing

literary skills required of the target and native

languages. Sayer (2013) found that in a multilingual

elementary classroom the use of an adaptable

bilingual pedagogy increased translanguaging in

the classroom, helping students to make sense of

content and learn language, while also legitimized

methods of accomplishing desired identities. However, most research has looked at ways

educators have promoted translanguaging inside

the classroom. Providing learners to express

themselves outside of the classroom not only offers

an opportunity for the learners to translanguage but

deepen arts and expression within their own identity

or possibly the community. Translanguaging outside

of the classroom has occurred specifically within art

forms transnationally and transculturally through

the use of international hip-hop (Alim, Ibrahim, &

Pennycook, 2009) and in creative writing literature

(Anzaldúa, 1987). By providing creative outlets for

learners to exercise their multilingualism, activities

such as the development of a literary magazine could

be a one of the simplest yet effective opportunities

for learners to translanguage. Olowalu Review The following sections describe the development

of an online literary magazine, Olowalu Review

(Olowalu meaning "of many voices" in Hawai'ian),

by an ELL instructor at a mid-sized university

in Hawai'i. Olowalu Review was developed

partially due to an "English-only" policy within the

instructor’s own institution of near one-hundred

students, and the lack of opportunities for students

to express their unique multilingual identities. The

English-only policy was highly valued as there was

a fear that students would self-segregate according

to their L1s and not use the target language of the

institution, English. Rather than disobey the longstanding

policies of the department, the instructor

chose to develop a platform outside of class, that

was not only open to his students but also the entire

university, local, and national communities. The lack

of space for the linguistically diverse body of learners

to use their L1, L2, or other languages acquired only

served to increase the need for such a platform of

self-expression through translanguaging. Learners,

restricted within monolingual policies throughout

the university and the country, had very few known

opportunities to express and create new identities or

generate space where their voices could be heard

especially among some of the students’ minority

languages such as Arabic or Hawai'ian. Development and Submissions One of the core elements of any literary magazine

is finding contributors and generating an audience

to read it. Therefore, in order to find contributors

interested in the writing for the magazine, language

department heads at the university were contacted

and asked to email or pass out a paper copy of a

flyer for submissions. Of the thirty-two language

departments at the instructor’s institution, twentyeight

responded and had handed out flyers or

emailed submission details to the enrolled students.

Submissions to Olowalu Review were also posted

on several local Facebook pages for creative writing.

Additionally, to gain wider contribution, diversity

in language use, and to spread translanguaging

awareness, three different contacts at three different

U.S. mainland universities were contacted and

posted submission flyers. Several forms of art

and literature were accepted as a part of Olowalu

Review, including but not limited to poetry, fiction,

nonfiction, and visual art. The only requirement for

submission was that the piece was either creative art

or literature through the use of multilingualism. The second core element during the development

of Olowalu Review was finding a unique, open, and

cost-effective platform to display the submissions.

Therefore, the most efficient and accessible platform

to develop Olowalu Review was through the use of

a free online website designer. The platform selected

was through that of Wix.com, although there are

several resourceful and professional websites to

choose from. However, before submissions and the

development of Olowalu Review could take place,

it was fundamental that the magazine had clear and

distinct goals of what it was trying to accomplish in terms of translanguaging and multilingualism. Goals of Olowalu Review In order to make an impact, spread awareness,

and create a realistic space for translanguaging

to occur, Olowalu Review developed five definite

goals based upon multilingual literature in the field

of language learning. These goals were heavily

influenced by the above literature on multilingualism,

identity, and translanguaging. Below each goal is

described in terms of setting a vision for Olowalu

Review that is consistent with the call for developing

translanguaging spaces for multilingual leaners and

speakers as well as serving as an outlet for art and

expression within the community and larger society.

The goals are as follows: 1) Raise multilingual and translanguaging

awareness. There is clear evidence that the world

is becoming more multilingual and the amount

of students and learners who translanguage is

increasing, as this is a common phenomenon

among multilinguals, regardless if they are confined

within a falsely perceived monolingual environment

of English-only policy (García, Zakharia, & Otcu,

2013). Through raising awareness of multilingualism

and translanguaging, leaners and speakers are

empowered, creating more cultural understanding

and provide a path to understand the borderlands of

language (Davis, 2009). 2) Promote multilingual use and identity.

Multilinguals have stories, experiences, and history

that not only one voice can tell, as seen in Anzaldúa’s

work (1987). It is clear that translanguaging happens

on a global level, for example in transnational hip-hop

(Alim, Ibrahim, & Pennycook, 2009); however, there

are limited known contexts where it is acceptable

for multilinguals to translanguage. To reach the

large amount of multilinguals there needs to be a

variety of platforms for acceptance, expression, and

construction of identity. Olowalu Review acts just

as one of the several platforms that could be used

to do this. 3) Enable speakers and writers to exercise their

multilingual knowledge. Building off of the above

goals, Olowalu Review is open to multilinguals of

any proficiency, age, or linguistic background. One

of its purposes is to be a space where multilinguals or

emerging multilinguals can express themselves and

use resources from their full linguistic repertoire to

practice language or develop identity. 4) Contribute as another resource and example

of translanguage/multilingual literature. With the

lack of artifacts in translanguaging and multilingual

literature, Olowalu Review can act as a foundation

for future research projects or as activities for

pedagogical practices in multilingualism. 5) Promote arts and expression in the local,

national, and global communities. Language is art,

and translanguaging is language. With the ability

to have submission from all over the world through

an online platform the art has the ability to express

local and global perspectives, crossing borders and

borderlands. The understanding and appreciation

of literature and art plays a fundamental role in

challenging current paradigms both individually

internal, and on a societal level. After goals had been established, call for

submissions posted, and the website designed, there

was a three month period in which the instructor

that developed Olowalu Review communicated

with authors and uploaded submissions to the

magazine’s website. Then after the three-month

period, the magazine went live online and was openaccess

to the authors and the public. Following the

magazine going live, the outcomes and findings

of the magazine were examined and feedback was

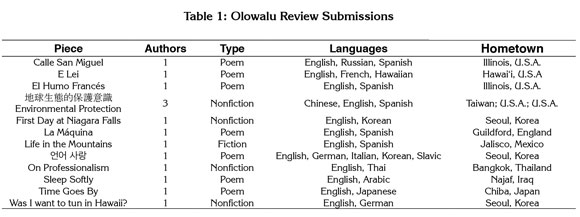

gathered from the authors. Outcome For the first issue of the multilingual magazine,

expectations of the instructor were met, but not

exceeded. There were a total of twelve submissions

by fourteen contributors that used thirteen different

languages, claiming their "hometown" from eight

different countries. Five of the submissions came

from the instructor’s English language institution,

while eight came from the instructor’s university. The remaining four submissions came from students at

universities in the mainland U.S.A.; a total of seven

poems, four non-fiction short stories, and one

fictional short story were submitted. Table 1 shows

the submission details of the authors. Methodology This article primarily focuses on the praxis

of translanguaging and its potential pedagogical

implications; however, there was a methodology

applied to the analysis of the submissions to

gain a deeper understanding of such a project’s

utility for multilinguals to express themselves in a

translanguaging space. The approach taken by the instructor at the

U.S. institution, who also was the developer of

Olowalu Review and researcher, took a qualitative

approach in interpreting the data but did not have

any participatory involvement influencing the literary

submissions of the authors. He stayed relatively

inactive in the writing process of the authors as

the goals of Olowalu Review, stated above, prefer

Olowalu Review to be a free space of multilingual

literary expression, allowing authors to use their

linguistic repertoire freely, promoting multilingual

use, awareness, and artistic expression. Rather, he

took an editorial approach towards the submissions,

simply responding to inquiries about one-time

submission guidelines. The intention was to allow

translanguaging to happen "naturally" and not

solicited by another individual (Canagarajah, 2011).

However, small-scale interviews were conducted

both via email and in person to seek out perceptions

and attitudes of the writing process from the authors.

Data gathered through interviews did not aim to

understand how the translanguaging occurred but

rather how it complimented what the writers wanted

to express in their literature. Submissions were briefly analyzed by adapting

Canagarajah’s (2013) framework of analyzing

translingual academic essays, identifying the literary

pieces as viewing the submissions as results of

code-meshing, which Canagarajah describes as a

"form of writing in which multilinguals merge their

diverse language resources with the dominant

genre conventions to construct hybrid texts for

voice" (p. 40). Through the lens of code-meshing,

Canagarajah’s four strategies were taken into

consideration into how specifically the author’s

may have used translanguaging to express their

unique literary voice, his four strategies being:

envoicing, recontextualization, interactional,

and entextualization. A brief explanation of each

strategy according to its relevance to the current

project is outlined below according to Canagarajah

(2013, p. 50): Envoicing is the use of translanguaging where

writers mesh semiotic resources for their identities

and interests to explain attitudes representing

writers’ voice. Recontextualization intends to structure the text

according to the desired genre and communicative

conventions. Interactional strategies attempt to aid the

reader and writer to co-construct meaning of the

text through ecological resources and to achieve

understanding despite language differences, and Entexutalization where text construction helps

aid in the author’s voice and meaning, for instance,

in Canagarajah (2013) this was through the use of

numerous drafts, feedback, and revision of one text.

However, this strategy does not apply to the current

project, as the researcher did not aid authors in

revision or feedback of their texts. Canagarajah (2013) describes these four

different strategies as methods of multilinguals

expressing their literary voice as ways of meaning

making through the writers’ semantic resources in

code-meshing. Although meaning making should

always be taken into consideration, the current article

analyzes and discusses these strategies as ways for

the writers to express their multilingual voice within

a completely open translanguaging space. Findings After the online publication of Olowalu Review,

it was clear that all submissions did translanguage

by using more than one language to express the

idea, story, or emotion behind the author. Although

not all submissions were thoroughly probed into

how the translanguaging occurred, it is clear that

the authors who submitted felt they could express

their multilingual voice through creative literature

and translanguaging. When briefly analyzing the

submissions to Olowalu Review, its visible that

each author translanguaged differently, and had

different ways to express their linguistic background

and identities. Also, it is clear that when given the

space, people express themselves through language

differently, with different stories, different languages,

history and culture, thus finding the need to

translanguage differently. Where some pieces used

one language dominantly, others distribute language

use quite evenly throughout their piece. Some

author’s chose to translanguage as a literary device,

creating "linguistic imagery" to convey thoughts or

stories by voicing certain elements of the piece to

awaken the reader’s auditory perceptions. This can

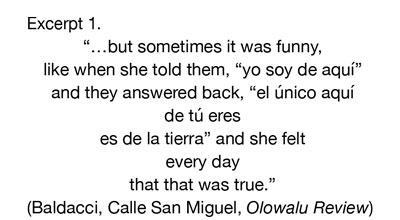

be seen in Excerpt 1. In Excerpt 1, the author conveys her thoughts

by utilizing resources in her full linguistic repertoire

to write about experiences, history, or thoughts

that reflect her voice and identity. However, she

does so by translanguaging as the literary device of

"linguistic imagery," as the excerpt displays external

characters using Spanish and the internal voice

uses English, thus displaying the contrast between

how the protagonist views herself and the perceived

identity of the surrounding characters. Along with translanguaging being utilized as a

literary device to reveal identity, many submissions

simply show that translanguaging is naturally

occurring and not solicited by another individual,

as discussed in Canagarajah (2011). Although it is

not entirely clear if all works use translanguaging

"naturally," regardless it can be appreciated that

the authors then used translanguaging to practice

L2s, or others acquired or studied languages in

attempts to develop an identity within a multilingual

space. Therefore, still fulfilling the conceptual

background behind the support of translanguaging

and multilingualism. Excerpt 1 also shows an

interactional strategy in translingual writing.

Here, the author uses the variation in language to

show a multimodal semiotic cue to represent her

voice and create meaning to her literature. Since

the author cannot rely on shared language for

readers to interpret her writing, her language use

creates a multisensory response to convey her

voice and the meaning of the piece (Canagarajah,

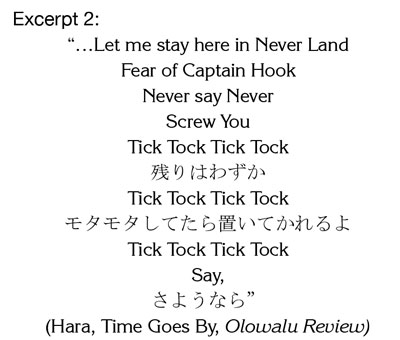

2013). Excerpt 2, below, also begins to show the

interactional translingual strategy. The author uses

the semantic resource of the onomatopoeia "Tick

Tock" to facilitate a co-construction of meaning

to her piece despite the possibility of shared

language norms (Canagarajah, 2013). Excerpt 2

and Excerpt 3 display how translanguaging varies

among multilinguals or emerging multilinguals

when provided the literary space to do so. Where in Excerpt 2 translanguaging occurs

again as a literary device though through the

onomatopoeia of "Tick Tock," the author’s voice

is also heard through the segment only in English

and the alternating phrases spoken in Japanese.

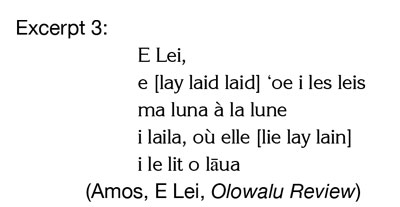

In Excerpt 3, the author uses three languages,

Hawaiian, English, and French interchangeably with

no clear or shifting pattern. Therefore, the exact

meaning of the poem would be rather difficult to

comprehend for someone unfamiliar in these three

languages, again showing that Olowalu Review

created the space for the author’s multilingual

voice to foster unique expressions of identity in

these three languages through translanguaging.

Through the variation of translanguaging among

submissions, it is quite clear that all pieces clearly

display the translingual strategy of envoicing due

to the nature of their creative writing literature. The

unique structure of the pieces themselves, served

as an interpretation into the authors’ writing style,

identity, and voice (Canagarajah, 2013). While some

of Canagarajah’s translingual writing strategies were

not as distinctly visible or as important to discuss,

such as recontextualization and entextualization,

this may be due to the freedom of genre allowed

in Olowalu Review. Whereas recontextualization is

focused on structuring a text according to a genre

and extextualization in the process and drafting

of a text, the fact that these literary pieces were

only categorized according to genre by the author

requiring no structural format, and requiring an

unedited one-time submission makes the current

analysis less rich in its ability to support them.

Although the authors did entail some structure to

their writing, opening a discussion on the translingual

strategy of recontextualization, pursuing a genreanalysis

of submissions was not seen necessary by

the researcher due to the pursuit of analyzing and

viewing the pieces as open literary expression. After several discussions with authors in

regards to their feedback on Olowalu Review, two

prominent perspectives prevailed and motivated

numerous authors to write for the magazine: space

and acceptance. Although a few authors did say

that writing their pieces was a bit challenging, they

viewed the opportunity to submit as a way to practice

the languages they have previously studied. When

asked about the experience they replied with phrases

such as "it was fun," "interesting," and a "good

way to practice." For many, there was an intrigued

sense in why they would do this, but afterwards

having a feeling of enjoyment and satisfaction.

Particular authors were pleased to finally have a

location to publish their work because they in fact

were multilinguals and translanguaging naturally

occurred in their written literature. After interviews

with authors, many found the researcher’s analysis

to be interesting and an interesting discussion on

their own writing and literary voice, showing them

the uniqueness in their multilingual expression, and,

consequently, showing the need for multilingual

spaces not only within language learning

classrooms but also on a much larger scale. One

author in particular felt a great deal of acceptance

through the ability to write in his native language

alongside English. By writing a bilingual poem in

Arabic and English, he felt that in this multilingual

space an identity through both languages could be

expressed. He felt this acceptance was well needed

due to current and historical issues relating to his

native language, culture, and country within the

English speakers’ culture and countries. Developing

translanguaging spaces can help to promote the

feeling of linguistic acceptance and equality which,

being viewed as a clear human right, can transcend greater tolerance towards others. Pedagogical Implications There are several pedagogical implications that

can be drawn from Olowalu Review specifically

relating to the language-learning classroom and

multilingualism. One of the first and most practical

applications from such a project could be developing

language and technology skills. An instructor of a

foreign or second language could create or have

students create websites in the target language.

Since there are a variety of free online website design

platforms to choose from, this is relatively easy as long

as the students have access to a computer or Internet.

Students could then design their own literary magazine,

or branch away from literature and develop a forum on

current issues, culture, history etc., through the use

of translanguaging which provides the opportunity for

students to not only learn technological skills but also

the freedom of linguistic expression. If the instructor or students decide to develop

an online literary magazine open to poetry or other

creative writing, the above findings do show that it

enables learners to function and express themselves

through translanguaging. Although learners will

most likely translanguage differently, it still facilitates

the expansion of the multilingual identity. It may

even be viewed as an opportunity to move towards

a more critical pedagogy on social issues, allow

the expression of those otherwise rather sedentary

in the target language, or promote tolerance and

equity needed in a democratic society. Also, by

providing the opportunity for students to utilize

their full linguistic repertoire, they have the chance

to uniquely practice their L1, L2, acquired, or

target languages. In Olowalu Review, authors

enjoyed writing their pieces and felt a sense of

accomplishment after they submitted. Therefore,

for emerging multilinguals, translanguaging through

creative writing may provide them the resources to

complete the task rather than become unmotivated

by an activity they feel is out of their target language

proficiency. Also, Canagarajah (2013) recommends

that translingual strategies are not explicitly

taught to students, rather that strategies occur

naturally through the students’ own terms through

facilitating awareness raising and the development

of writing practices. This article does not explicitly

discuss awareness raising or development of

writing practices in terms of teaching translingual

strategies; more so it focuses on providing the

space and the awareness of translanguaging’s

existence. Instead, these strategies should be

taken into account in terms of understanding the

context and use of translanguaging in multilingual

writing. The assessment of translingual strategies

could become problematic as mentioned in

Canagarajah’s work, due to the teacher’s own

translanguaging development and difficulty leaving

established academic norms. Although several other

pedagogical implications can be investigated out of

the Olowalu Review project, the goal of this article

is to display how such endeavors can help foster

learner or multilingual identity and be a great outlet

or space to practice target or acquired languages. Lastly, not so much as a pedagogical implication

but rather a duty of an educator is to allow such

spaces for arts and expression to exist. Being

in language education consequently raises the

responsibility of creating and promoting multilingual

and translanguaging spaces for not only students

but also members of the larger community. Simple

projects like Olowalu Review can help educators

accomplish their duties to their students and society. Conclusion The development of Olowalu Review occurred

as a result of an instructor seeing the inability his

students had to express themselves as emerging

multilinguals. With the recent shift towards new

theory and modes of approaching multilingualism in

the language learning classroom, there is a clear need

for translanguaging space where multilinguals can

have the opportunity to develop and foster identity.

Olowalu Review attempted to provide not only

students and the instructor’s home institution but

also members of the larger multilingual community

translanguaging space through creative writing. The

initial goals of Olowalu Review were met; however,

there is clearly room for improvement. Future

projects could dive more deeply into the process of

translanguaging of the authors, or discussion of why

the authors chose to write about specific topics and

further examine how Canagarajah’s (2013) strategies

impact the writing process of the authors. Also,

developing multiple issues of one magazine may also

increase publicity for the magazine, gaining a wider

range of submissions and readership. Regardless

of research propositions, all language instructors

could develop a similar project to Olowalu Review.

Whether the focus is simply another opportunity

to practice the L1 or L2, develop technological

skills, or foster multilingual identity, such a project

can have impacting implications in or outside the

classroom. Olowalu Review by no means was an

overly difficult project to carry out, all it comes down

to is if language educators want to truly be involved

in the changes occurring in our multilingual society

and fostering adequate space for learners to grow. Link to Olowalu Review: http://olowalureview.wix.com/olowalureview. References Alim, H. S., Ibrahim, A., & Pennycook, A. (2009). Global

linguistic flows: Hip hop cultures, youth identities,

and the politics of language. London, UK: Routledge. Amos, K. (2015). E lei. Olowalu Review 1. Retrived from

http://olowalureview.wix.com/olowalureview#!e-lei/cm6k. Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands/La frontera. San

Francisco, CA: Spinsters/Aunt Lute Book Company. Baldacci, L. (2015). Calle San Miguel. Olowalu Review

1. Retrieved from http://olowalureview.wix.com/olowalureview#!calle-san-miguel/c208c. Canagarajah, S. (2011). Translanguaging in the classroom:

Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. In L.

Wei (Ed.), Applied Linguistics Review, 2 (pp. 1-27).

New York, US: Walter de Gruyter. Canagarajah, S. (2013). Negotiating translanguaging

literacy: An enactment. Research in the Teaching of

English, 48(1), 40-67. Canagarajah, S., & Liyanage, I. (2012). Lessons from

pre-colonial multilingualism. In M. Martin-Jones,

A. Blackledge, & A. Creese (Eds.), The Routledge

handbook of multilingualism (pp. 49-65). London,

UK: Routledge. Cenoz, J. (2013). Defining multilingualism. Annual

Review of Applied Linguistics, 33, 3-18. Davis, K. (2009). Agentive youth research: Towards

individual, collective and policy transformations. In

T. G. Wiley, J. S. Lee, & R. Rumberger (Eds.), The

education of language minority immigrants in the

USA (pp. 202-239). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual

Matters. De Mejía, A. M. (2005). Bilingual education in South

America. Buffalo, NY: Multilingual Matters. García, O., & Wei, L. (2013). Translanguaging: Language,

bilingualism and education. New York: Palgrave

Macmillan. García, O., Zakharia, Z., & Otcu, B. (2013). Bilingual

community education for American children:

Beyond heritage languages in a global city. Bristol,

UK: Multilingual Matters. Hara, T. (2015). Time goes by. Olowalu Review 1.

Retreived from http://olowalureview.wix.com/olowalureview#!time-goes-by/ca2w. Phillipson, R. (1998). Globalizing English: Are

linguistic human rights an alternative to linguistic

imperialism? Language Sciences, 20(1), 101-112. Phillipson, R. (2003). English-only Europe?: Challenging

language policy. New York: Routledge. Sayer, P. (2013). Translanguaging, TexMex, and bilingual

pedagogy: Emergent bilinguals learning through

the vernacular. TESOL Quarterly, 47(1), 63-88. Swain, M. (2006). Languaging, agency and collaboration

in advanced second language learning in H.

Byrnes (Ed.), Advanced language learning: The

contributions of Halliday and Vygotsky (pp.

95-108). London, UK: Continuum. Wei, L. (2010). Moment analysis and translanguaging

space: Discursive construction of identities by

multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222-1235.

1 Universidad de Los Andes. Bogotá, Colombia. aj.kasula@uniandes.edu.co

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.

.JPG)