DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v19n1.10032Published:

2017-02-10Issue:

Vol 19, No 1 (2017) January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesThe acquisition of vocabulary through three memory strategies

La adquisición de vocabulario a través de tres estrategias de memoria

Keywords:

memorización, estrategias, vocabulario, adquisición de vocabulario (es).Keywords:

Vocabulary, strategies, memorization, vocabulary acquisition. (en).Downloads

References

Ae-Hwa K., Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., & Wei, S. (2004). Graphic organizers and their effects on the reading comprehension of students with LD: A synthesis of research. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37(2), 105-18. doi:10.1177/00222194040370020201

Anderson, J. P., & Jordan, A. M. (1928). Learning and retention of Latin words and phrases. Journal of Educational Psychology, 19, 485-496. doi:10.1037/h0073011

Arias, L. D. (2003). Memory? no way! Folios, 18, 115-120.

Bos, C. S. & Anders, P. L. (1990). Effects of interactive vocabulary instruction on the vocabulary learning and reading comprehension of junior-high learning disabled students. Learning Disability Quarterly, 12(1), 31-42. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1510390

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching Languages to Young Learners. London:

Cambridge University Press.

Cárdenas, M. (2001).The challenge of effective vocabulary teaching. Profile, 2(1),48-56. Retrieved from http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/index

Catalan, R. M. J. (2003). Sex differences in L2 vocabulary learning strategies. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 13(1), 54-77.

Chamot, A.U. (2009). The CALLA handbook: Implementing the cognitive academic language learning approach (2nd ed.). White Plains, NY:

Pearson Education/Longman.

Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1994). Research methods in education (4th ed.). New York, N.K.: Routledge.

Colombia, M. (2001). Improving new vocabulary learning in context. Profile, 2(1), 22-24. Retrieved from http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/index

Cheng, Y., & Good, R. L. (2009). L1 glosses: Effects on EFL learners’ reading comprehension and vocabulary retention. Reading in a Foreign Language, 21(2), 119-142. Retrieved from http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/

DeWitt, K. C. (2010). Keyword mnemonic strategy: A study of SAT vocabulary in high school English (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3421702).

Folse, K. (2004). Vocabulary myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching. USA: Michigan.

Ghazal, L. (2009). Learning vocabulary in EFL contexts through vocabulary learning strategies. Novitas-ROYAL, 1(2), 84-91. Retrieved from http://pdfcast.org/pdf/learning-vocabularyin-efl-contexts-through-vocabulary-learning-strategies.

Gu, Y. (2003). Vocabulary Learning in a Second Language: Person, Task, Context and Strategies. TESL-EJ, 7(2), 1-18

Harmer, J. (2007). The Practice of English Language Teaching. Cambridge, U.K.: Pearson Education Limited.

Hong, P. (2009). Investigating the most frequently used and most useful vocabulary language learning strategies among Chinese EFL postsecondary students in Hong Kong. Electronic Journal of Foreign

Language Teaching, 6(1), 77-87. Retrieved from http://eflt.nus.edu.sg/

Kojic-Sabo, I. & Lightbown, P. M. (1999). Students’ approaches to vocabulary learning and their relationship to success, Modern Language Journal, 83, 176-192. doi:10.1111/0026-7902.00014

Mastropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E. (1998). Enhancing school success with mnemonic strategies. Intervention in School and Clinic, 33(4), 201-201. doi:10.1177/105345129803300402

Mediha, N, & Enisa, M. (2014). A Comparative Study on the Effectiveness of Using Traditional and Contextualized Methods for Enhancing Learners’ Vocabulary Knowledge in an EFL Classroom. 5th World Conference on Educational Sciences, (116), 3443-3448. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.780

Nakata, Tatsuya (2008). English vocabulary learning with word lists, word cards and computers: implications from cognitive psychology research for optimal spaced learning. ReCALL, 20(1), 3-20. doi:10.1017/S0958344008000219

Nation, I.S.P. (1990). Teaching and learning vocabulary. New York: Heinle and Heinle.

Nation, I.S.P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Nation, I.S.P. (2008). Teaching vocabulary: Strategies and techniques. Boston, USA: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Nunan, D. (1992). Collaborative language learning and teaching. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Obringer, L. A. (2001). The psychology of learning. Retrieved August 12, 2012 from

http://people.howstuffworks.com/elearning2.htm

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies.What every teacher should know. Boston: Heinle and Heinle.

Pérez, L. M. (2013). The acquisition of vocabulary through three memory strategies.(Masters thesis, Universidad de la Sabana, Chia, Colombia). Retrieved from: http://intellectum.unisabana.edu.co/handle/10818/6657

Pigada, M., & Schmitt, N. (2006). Vocabulary acquisition from extensive reading: A case study. Reading in a foreign language, 18(1),1-28. Retrieved from http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/

Pineda, J. (2010). Identifying language learning Strategies: an exploratory study. Gist Education and Learning Research Journal, 4(1), 94-106. Retrieved from http://www.unica.edu.co/archivo/GIST/2010/07_2010.pdf

Rivers, W. (1983). Communicating naturally in a second language. NY: CUP.

Rott, S. (1999). The effect of exposure frequency on intermediate language learners’ incidental vocabulary acquisition through reading. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21(1), 589-619.

Sanaoui, R. (1995). Adult learners' approaches to learning vocabulary in second languages. The Modern Language Journal, 79(1), 15-28. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb05410.x

Schmitt, N. (2008). Review article: Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research,12,329-363.doi: 10.1177/1362168808089921

Schmitt, N. & Schmitt, D. (2014). A reassessment of frequency and vocabulary size in L2 vocabulary teaching. Language Teaching, (47), 484-503 doi: 10.1017/S0261444812000018

Sprenger, M. (1999). Learning and Memory: The brain in action. Alexandria, VA, USA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development [e-book]. Retrieved from

http://site.ebrary.com/lib/bibliounisabana/Doc?id=10110324&ppg=72

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). The basic of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedure and techniques. (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications.

Thornbury, S. (2004). How to teach vocabulary. (3rd Ed). England, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

Troutt-Ervin, E. (1990). Application of keyword mnemonics to learning terminology the college classroom. Journal of Experimental Education, 59(1), 31.

Trujillo, C. L., Álvarez, C. P., Zamudio, M. N. & Morales, G. (2015). Facilitating vocabulary learning through metacognitive strategy training and learning journals. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 246-259. doi: 10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a05

Wallace, M. (2008). Action research for language teachers. London, UK: Cambridge university press.

Waring, R. & Takaki, M. (2003). At what rate do learners learn and retain new vocabulary from reading a graded reader? Reading in a Foreign Language, 15(2), 130-163. Retrieved from http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/

Wilkins, D. A. (1972). Linguistics in language teaching. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/calj.v19n1.10032

RESEARCH ARTICLES

The Acquisition of Vocabulary Through Three Memory Strategies

La adquisición de vocabulario a través de tres estrategias de memoria

Libia Maritza Pérez1, Roberto Alvira2

1 Universidad del Tolima, Tolima, Colombia. lmperezmo@ut.edu.co

2 Universida de la Sabana, Bogotá, Colombia. roberto.alvira@unisabana.edu.co

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Pérez, L. & Alvira, R. (2017). The Acquisition of Vocabulary Through Three Memory Strategies. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 19(1), pp. 103-116.

Received: 30-Jan-2016 / Accepted: 05-Nov-2016

Abstract

The present article reports on an action research study that explores the implications of applying three vocabulary strategies: word cards, association with pictures, and association with a topic through fables in the acquisition of new vocabulary in a group of EFL low-level proficiency teenagers in a public school in Espinal, Tolima, Colombia. The participants had never used vocabulary strategies to learn and recall words. Two types of questionnaires, a researcher's journal, and vocabulary tests were the instruments used to gather data. The results showed that these strategies were effective to expand the range of words progressively and improve the ability to recall them. The study also found that these strategies involve cognitive and affective factors that affect students' perception about the learning of vocabulary. The implementation highlighted the need to train teachers and learners in strategies intended to teach and learn vocabulary and to subsequently include them in the English language program in any school.

Keywords: memorization, strategies, vocabulary, vocabulary acquisition

Resumen

El presente estudio de investigación-acción explora las implicaciones de la aplicación de tres estrategias de vocabulario: tarjetas de palabras, la asociación con imágenes y la asociación con un tema a través de fábulas en la adquisición de nuevo vocabulario con un grupo de adolescentes con bajo nivel de competencia en inglés como lengua extranjera, estudiantes de un colegio público en Espinal, Tolima, Colombia. Los participantes nunca antes habían utilizado estrategias de vocabulario y les resultaba difícil memorizar y recordar palabras. Los instrumentos utilizados para recopilar datos fueron: dos tipos de cuestionarios, el diario del investigador y las pruebas de vocabulario. Los resultados mostraron que estas estrategias fueron eficaces para ampliar progresivamente la gama de las palabras y mejorar la capacidad para recordar palabras. El estudio también encontró que estas estrategias involucran factores afectivos y cognitivos que afectan la percepción de los estudiantes acerca del aprendizaje de vocabulario. La implementación de las estrategias pone de relieve la necesidad de entrenar a los profesores y a los alumnos en las estrategias destinadas a enseñar y aprender vocabulario, y la de incluirlas en el programa del idioma inglés de cualquier colegio.

Palabras clave: memorización, estrategias, vocabulario, adquisición de vocabulario

Introduction

Vocabulary acquisition is an essential part of the communication of meaning (Wilkins, 1972) and of mastering a language (Schmitt, 2008). Furthermore, as stated by Mediha and Enisa (2014), communication cannot take place without having enough vocabulary. Thus, there is an imperative need to empower learners with strategies that enable them to increase their word knowledge. Training learners to use vocabulary strategies can help them to make decisions about their use and also can help them become more autonomous by having them decide on the strategies to be used.

This study is based on a pedagogical intervention intended to evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of three memory strategies (word cards, association with a picture, and association with a topic or story) to acquire vocabulary through fables and to compare the memory strategies to determine their effectiveness. The strategies were implemented in a public school in Espinal, Tolima, as part of the school program for 11th graders who have A1- and A1' levels of English according to the Common European Framework (CEFR); these students have problems learning new words. A need analysis carried out in the preliminary stage of the study, based on the scores of the SABER (knowledge, in Spanish) tests from 2009 to 2011, which are the tests given by the Ministry of Education to all 11th graders in the country, showed that each year more students were ranked at the A1- level and fewer students were on A1' level. This seems to be linked to their lack of vocabulary and the ability to retain and retrieve words as it was revealed in surveys and classroom tests. Consequently, if teachers and learners could be aware of learning strategies, they could develop tools to be used in the future and that could help students to be more autonomous. On the other hand, few studies have been performed in Colombia regarding this topic. For this reason, this article is relevant to the Colombian context.

The following research question was formulated: What might the implementation of memory strategies inform us about the acquisition of vocabulary through fables in a group of teenagers with a low-level of English proficiency in a public school at El Espinal?

Theoretical Framework

The Acquisition of Vocabulary and Long Term Memory (LTM)

Researchers agree on the fact that learning vocabulary is an important component to be functional in an EFL context since "without vocabulary nothing can be conveyed" (Wilkins, 1972, p. 111) and "without vocabulary, no communication is possible" (Folse, 2004, p. 25). In addition, Folse (2004) points out "how frustrating it is when you want to say something and are stymied because you don't know the word for a simple noun!" (p. 23). Thus, students will always need to develop their capacity of expanding their stored level of words.

Thornbury (2004) claims that "acquiring vocabulary requires not only labeling but categorizing skills" (p. 18), and Oxford (1990) states that some elements of language use are at first conscious as result of the direct instruction but then become unconscious or automatic through practice. This situation highlights the need for the use of training to be able to organize, interconnect and link previous word knowledge to the new one in order to process new information. In doing so, learners can build up a store of words to be used in both passive and active ways.

In fact, vocabulary needs to be meaningfully stored in long-term memory (Arias, 2003) and this requires establishing links between words. Research into memory suggests some principles, including repetition and retrieval (Nation, 2001), spacing, pacing, use, cognitive depth, organization, imagining, and mnemonics to ensure that the information moves into permanent LTM (Thornbury, 2004). These principles are reflected in memory strategies "such as arranging in order, making association, and reviewing" (Oxford, 1990, p. 39), so by following them, students can learn and use vocabulary in a meaningful way.

On the other hand, repeated exposure to new words is necessary. Although the idea regarding the number of encounters range from five to sixteen (Nation, 1990), six (Rott, 1999) or more (Thornbury, 2004), at least eight (Waring & Takaki, 2003), and more than ten (Pigada & Schmitt, 2006), it is clear that the more the students deal with new words the better they enhance their learning. Indeed, studies indicate a progressive forgetting process of learned words. Schmitt (2008) claimed "most forgetting occurs after the learning sessions…so the first recycling [is] important and need[s] to occur quickly" (p. 343). Anderson and Jordan (1928) reported a decrease in the learning rate of 66%, 48%, 39%, and 37% after one, three, and eight weeks respectively. These findings highlight the need for giving students repeated opportunities to use the new words. This need is stressed by the fact that the vocabulary included in textbooks lacks a standardized approach to teaching vocabulary and the new words are not used frequently enough to cause long-term learning (Schmitt & Schmitt, 2014).

Memory Vocabulary Strategies

Becoming independent learners requires the management of strategies (Ghazal, 2009). Vocabulary can be learned through incidental learning or direct intentional learning. Nevertheless, incidental learning is more likely to occur when students have a high-proficiency level and might read for pleasure (Nation, 2001). A direct vocabulary approach "always leads to greater and faster gains, with a better chance of retention and of reaching productive level of mastery" (Schmitt, 2008, p. 341). Students, especially those with a low-proficiency level such as the participants in this study, can benefit from direct intentional learning strategies to provide more direct vocabulary attention (Scarcella & Oxford, 1992), and to "learn a very personal selection of items organized into relationships in an individual way" (Rivers, 1983, p. 341).

Vocabulary strategies have been defined as "actions that learners take to help themselves understand and remember vocabulary" (Cameron, 2001, p. 92). More recently, Catalan (2003) defined vocabulary learning strategies as:

Knowledge about the mechanisms used to learn vocabulary as well as steps or actions taken by students to (a) find out the meaning of unknown words, (b) retain them in long-term memory, (c) recall them at will, and (d) use them in oral or written mode. (p. 56)

Researchers have been interested in determining the effectiveness of vocabulary strategies on vocabulary retention. Sanaoui (1995) found that those students who had a more structured vocabulary learning approach performed better at recalling vocabulary. Hong (2009) studied learners' perception of the usefulness of vocabulary learning strategies and found the strategies significantly useful for learning vocabulary and that the more learners used a strategy, the more useful they considered the strategy to be and the better they could clearly indicate their preferences. Kusumarasdyati (n.d.) also concluded that students need to be encouraged to practice different vocabulary strategies to discover which one is more suitable for them.

In relation to the Colombian context, Colombia (2001) indicated that real and unreal contexts created in the class can make it easier for students to acquire meaningful vocabulary knowledge. Pineda (2010) found that, when reading a text, the strategies university students use to learn new words are limited to trying to infer their meaning from the context and to resorting to their native language to understand the reading. Pineda (2010) suggests that "they use Spanish cognates (true or false ones) to guess the meaning of unknown words; even to translate titles and subtitles while determining a topic" (p. 104). He points out that, very often, teachers fail to apply the most effective strategies. He indicated that it is important that teachers identify the strategies their students may need, and become able to expose learners to those strategies. He concluded that training them on the identification and use of language learning strategies may change that situation and enable learners to become more autonomous. Pineda's findings are aligned to what Cárdenas (2001) stated as one of the main challenges for teachers, effective vocabulary teaching. Therefore, these findings demonstrate an imperative need for teachers to be able to help students in their vocabulary learning process.

Among direct strategies, which are also called memory or mnemonic strategies, Oxford (1990) provides four sets: "creating mental linkages, applying images and sounds, reviewing well, and employing actions" (p. 38). The way to put this into practice is explained by Rivers (1983): "vocabulary cannot be taught. It can be presented, explained, included in all kinds of activities in all manner of associations…but ultimately it is learned by the individual…in an individual way" (p. 123). This leaves the role of the teacher as a facilitator of the learning process that, ultimately, has to be performed by the students themselves.

This study investigates three memory strategies: word cards, association with pictures, and association with a topic.

Word Cards.

Word cards are useful tools to promote deliberate vocabulary learning effectively and to facilitate the learning of large numbers of words in a short time and the ability to recall them for a very long time (Mastropieri & Scruggs, 1998; Nation, 2008). Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of using word cards with students with or without disabilities (DeWitt, 2010), and have provided useful guidelines to develop and organize this strategy (Nation, 2001; Pressley, Levin, & Delaney, 1982).

In this regard, Nation (2008) indicates how to train students on how to choose new words to avoid interference; he recommends avoiding combinations of words that are (1) similar in spelling or sound, for example kitchen and chicken, (2) similar in meaning but not exactly the same, for example remind and remember, (3) opposites, for example clean and dirty, and (4) members of a lexical set for example, the days of the week, because "research shows that [learning related words] makes the learning task more difficult" (Nation, 2008, p. 109). Furthermore, he provides guidelines on how to train learners to use word cards which include five basic parts: (1) choosing word or phrases and writing them down on cards in order to see how they can be used, (2) going through the cards to explain to learners how to use the cards, (3) checking the words repeatedly to provide frequent opportunities to have contact with them, and (4) motiving students to use the strategy often, for example by allowing them to work in pairs to test each other and by reporting to the class their success in using the strategy. Thornbury (2004) pinpointed useful activities to help learners use the strategy and encourage the independent use of words: pre-teaching and testing, guess my word, and association with games. Word cards are still quite useful, even in the predominantly computer era, as Nakata (2008) found in his study in which he compared vocabulary learning with word lists, word cards, and computers with 226 Japanese high school students. The results showed no statistically significant difference between computers and word cards and their superiority over lists.

Association with Pictures.

According to Arias (2003), association with pictures is "highly useful for those learners who are visually oriented" (p. 118). This allows visual learners to associate what they see or imagine, to make the words more memorable for them, and to retrieve the words easily from their long-term memory into a working memory (Thornbury, 2004). This image-keyword strategy is highly effective to recall words and to increase students' engagement with their learning since it is based on the strong effect that pictures have on memory, especially when—as in this study—the learners themselves have to make an effort to decide on the pictures they draw to link to a word. As Goll (2004) stated, "the more strongly you imagine…a situation, the more effectively it will stick in your mind for later recall" (p. 309). This happens even in the case where students have no easy access to computers, as the subjects of this study, neither at school nor at home. Oberg (2011) found that the strategy of association with pictures can be equally beneficial when used with a CALL image-based method or a paper card image-based method. In this case, 71 first-year Japanese university students comprising two classes participated in the study. The students studied a practice set of 10 vocabulary items using both of the two methods and then a treatment set of 10 different items using only one of the methods to which the students were randomly assigned. A t-test done on the groups' vocabulary pretest scores showed no significant difference between the two groups in terms of knowledge of the items at the outset of the experiment. The analysis of the posttreatment data showed no significant difference between the groups. Finally, a post-treatment survey

Association with a Topic

Stories emanating from fables or situations can be the vehicle for vocabulary learning (Arias, 2003). A topic can be used by students to build up an association network (Thornbury, 2004). Oxford (1990) states that "this strategy incorporates a variety of memory strategies like grouping, using imagery, associating and elaborating, valuable for improving both memory and comprehension of the new expression" (p. 62). Diagrams can allow users to make their own association and visualize the word-connection that makes them a powerful visual image of the information.

Research has shown that the use of diagrams benefits learning as they promote greater recall, comprehension, and vocabulary learning (Bos & Anders, 1990) and improve reading comprehension in students with learning disabilities (Ae-Hwa, Vaughn, Wanzek, & Wei, 2004). In a study carried out by Idol and Croll (1987), five intermediate-level, elementary students with mild learning handicaps and poor comprehension were trained to use story-mapping procedures as a schema-building technique to improve reading comprehension. The outcome was that all five students' performance improved on most of the dependent measures. Four students demonstrated increased ability to answer comprehension questions, maintained performance after intervention, and increased the tendency to include story-mapping components in their story retells. Additionally, the use of diagrams can serve students to generate ideas to make appropriate connections which can help them not only to recall the words but also to develop their thinking skills.

Methodology

This qualitative action research study investigated the effectiveness of a practical response to a problem observed in a class (Nunan, 1992) in the public school where the researcher taught English. The teacher-researcher was interested in finding a solution oriented to helping these students overcome their lack of ability to learn and recall words, by facilitating and using a motivational approach for the students to improve their use of memory strategies. In order to accomplish this, data were collected from students' impressions, their performance, and the teacherresearcher's own observations.

Research Setting and Participants

This research study took place in an urban technical public high school in Espinal, Tolima, Colombia, whose vision is to promote among its learners an awareness of being productive and responsible for their own decisions. The approach to English language teaching within the school is grammar-based. Students attend two one-hour English classes a week.

Although the entire eleventh-grade group was engaged in the research experience, twelve out of thirty 11th graders consented to participate in the study. The participants' average age was seventeen years old; ten students had an A- level and two students were at A1 English level, and they had been taking English lessons for five years. To prepare students to present the SABER (Knowledge) examinations which evaluate all high school seniors in the country every year, students were given mock examinations whose outcomes were used by the teacher-researcher, along with the data from the needs analysis, to determine students' needs in terms of vocabulary and language in general. The conclusion was that the students struggled to memorize vocabulary, to recognize words they had learned, and to recall them. For this reason, the teacher and the students agreed to implementing the three vocabulary strategies to train them in vocabulary development.

Data Collection Instruments

The researcher used two types of questionnaires, a researcher's journal, and vocabulary test to gather data. These instruments were piloted before the formal intervention started.

Questionnaires. The questionnaires were administered in Spanish to gather participants' perceptions about the effectiveness of the three memory strategies. The first type of questionnaire was about word cards and was applied as soon as each one of the three memory strategies was administered to gradually collect information of each one of them. The second type of questionnaire was applied after the implementation of the second and the third strategy to compare the effectiveness of each strategy with the previous one. This also included a final questionnaire that evaluated the strategies from the students' viewpoint to determine which one was more effective for vocabulary learning.

Researcher's Journal. The Researcher's Journal "[provides] an effective means of identifying variables that are important to individual teachers and learners, and [enables] the researcher to relate classroom events and examine trends emerging for them" (Wallace, 2008, p. 63). Thus, this instrument was useful to keep a written record of the teacherresearcher's reflections about the effectiveness of each strategy. This information was triangulated with the participants' opinions.

Tests. Tests allowed the researcher to examine the students' performance at the end of the implementation to establish the effectiveness of the strategies on vocabulary retention. The vocabulary tests were developed based on Nation's (2008) and Thornbury's (2004) instructions. The word cards were tested taking into account translation and gaps in which the first letter was provided. Association with pictures was tested using gapfilling examinations in which words were replaced with pictures. Association with a topic was tested using gap-filling examinations. The real names of the participants were replaced with numbers.

Data Collection Procedure

Word cards, association with pictures, and association with a topic were applied in three units, or modules. Each module had three sessions (the reading of three short fables) to: (1) model the use of the strategy by the teacher, and (2 and 3) apply the strategy by students. During each module, the researcher collected the data with a vocabulary test, a questionnaire, and the researcher's journal. The vocabulary tests were applied after each strategy and a final recall vocabulary test at the end of the implementation. Additionally, three comparative sets of questions (questionnaires) were applied to identify students' preferences in terms of strategies to learn and retain vocabulary. These comparative questionnaires were intended to (1) compare word cards and association with pictures, (2) compare association with pictures with association with a topic, and (3) compare the three strategies.

Instructional Design

The pedagogical proposal was divided into three stages.

Pre-stage. The students were informed about the objective of the study. Consent letters were signed by the twelve volunteers who took part in the project as well as their parents and the school principal.

While-stage. The treatment order was: first, word cards; then, association with pictures; and lastly, association with a topic. Each module had two basic steps: (1) applying the strategy and (2) analyzing and validating collected data by the instruments applied. During the first step, the students were trained in each strategy; afterward, the strategy was repeated twice; finally, the vocabulary retention of the participants was measured in the first step with vocabulary tests and researcher's journals. During the second step, a questionnaire was applied to establish the usefulness as well as the possible changes that needed to be made. In addition, a comparative questionnaire was administered at the end of the second and third modules.

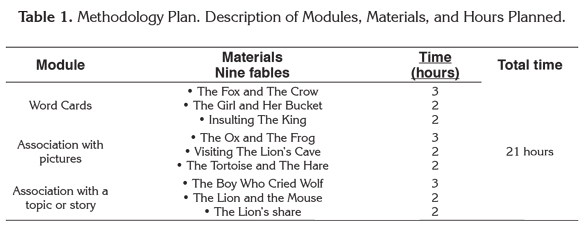

Nine lesson plans were designed in accordance with the ICELT (In-service Certificate in English Language Teaching) criteria to organize the activities in the session and to decide on the materials to be used. Table 1 includes the characteristics of the modules, sessions, and the materials.

Training on each strategy took three hours for the first material of each module. The first fable of each session of each module was planned to model, demonstrate, and practice the strategy. Then, the students applied the steps of the strategy by themselves. Regarding word cards, the steps were adapted from Nation's (2008) and Thornbury's (2004) instructions:

1. Learners made the small cards about 4 cm. x 2cm.

2. Learners wrote a word on one side and its translation into Spanish on the other.

3. Learners tried to recall what was written on each card by checking in pairs.

4. Words that caused difficulty were moved to the top of the pack so that they could be looked at again soon.

5. After going through the pack once or twice, the students started working with a different pack and the previous one was left aside to be reviewed later. The cards had to be shuffled periodically to avoid "serial effects."

A keyword technique was adapted (Nation, 2008) to set the steps of the strategy.

1. Students thought of an image to represent the word.

2. Pairs of students checked the meaning of the words using their picture charts and books.

3. Pairs of students checked the vocabulary at increasing spaced intervals of time.

In the case of association with a topic, the following four steps were designed.

1. The students built an association network centered on the topic of the reading.

2. The students connected other associated words to the network.

3. The students compared their network with a classmate to extend the information.

4. The students read the story again and adjusted the information in their network.

5. The students tried to recall the words by checking in pairs. (Pérez, 2013, p. 57)

Students chose to use short narratives from a set of three topics: sports, fashion, and tales because they liked them, they had previous knowledge of their content in Spanish, and had a meaningful context that could allow them to remember the words. Nine short stories were selected by the teacher researcher. As Thornbury (2004) indicated "for vocabulary building purposes, texts…have enormous advantages over learning words from lists…and can be subjected to intensive…lexical study" (p. 53). While reading the text for the first time, the students underlined the unknown vocabulary, and then, with the teacher's guidance, students agreed on another fifteen new words to be learned during the session. In the case of word cards, students worked with small cards to create their set of words. For pictures, students used their previous knowledge of the content of the story to draw pictures that helped them remember the words. For association with a topic, students used the title of the fable or its content to create a semantic map.

Post-stage. Students took a vocabulary test after each strategy and a final vocabulary test at the end of the implementation. Additionally, three comparative questionnaires were applied to compare a strategy with the previous one and to gather the students' perceptions about the effectiveness of the three memory strategies.

Results and Discussion

The analysis included aspects of quantitative data analysis and the grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The quantitative data represented by the scores in the tests allowed the researcher to identify the strategy that produced the best results in vocabulary retention and provided a different perspective that supported the qualitative analysis, increasing its validity. The triangulation of the data was taken into account to corroborate the findings from the other data collection instruments and to strengthen the analysis. In addition, Strauss and Corbin's (1990) grounded theory allowed the researcher to explore data to identify units of analysis, to decide on the codes to be used, to group the information into categories and subcategories, and to integrate codes for analysis.

Overall, the findings of the study are twofold: findings related to affective factors and others related to cognitive factors. These factors seemed to be influenced by social strategies such as interaction.

Findings Related to Affective Factors

The strategies of word cards and association with pictures were perceived by the students as easyto- handle and helpful to make the learning process interesting and effective which fostered students' motivation towards their use. As Obringer (2001) indicated with respect to the psychology of learning, "making the learning more fun-or interesting—is what makes it more effective" (p. 2). Hence, from the students' viewpoint, strategies can yield positive leaning outcomes when they are fun for them to use. This trait seems to have been achieved in the pedagogical implementation as evidenced in comments of the following type, referring to Word Cards (answers were originally given in Spanish and translated into English by the teacher-researcher): "It's fun and an effective way to learn new words" (Student 2, Question No. 2. First questionnaire. Word Cards). Another student suggests that "it's a practical and didactic method, and I can remember the words easily with the help of the pictures" (Student 6, Question No. 2. First questionnaire. Association with pictures).

Kojic-Saba and Lightbown (1999) found in their study that in an EFL environment, learners may need to create opportunities by themselves to find and practice new English words, and "to put extra effort into the learning process, to take it outside the classroom, and to build on it by independent learning" (p. 16). The data showed that learners were willing to prepare their material at home and to work with their peers in class when they found a purpose for the use of the vocabulary strategies, as evidenced in the following comment: "I felt motivated to study vocabulary with this strategy." (Student 12, Question No. 5. First questionnaire. Word cards.). Also, the teacher took note of this situation in the researcher's journal: "Students checked the words in pairs in the classroom and this motivated them to apply the strategy at home. All students wanted to outperform their partners in the number of words they had learned." (Word cards.) "I realized that the learners kept their word cards and their drawing in their notebooks. This surprised me because my students do not usually keep the things they did after finishing their classwork" (Association with pictures).

The data also indicated that some participants adapted the word card strategy and replaced the words for pictures. The students customized the strategies to supply their learning styles. In the case of word cards, the students replaced the Spanish word with the pictures and in the case of association with pictures, students cooperated among themselves. This helped them to become more confident to find ways to illustrate the meaning of the words or make a connection among them. This interaction also made the students more autonomous. They relied less on the teacher's instructions and more on their ideas and those of their peers. They began asking one another the meanings of words and sharing ideas about whicOxford, 1990).h drawing could better illustrate their words, how to better connect words and represent that connection on the semantic map. Thus, this became a more learner-centered activity and the feeling of success of the students motivated them to study more, as evidenced in the answers to the first questionnaire: "We have to interact to develop the strategy, and this interaction is interesting and encourages us to continue with the process" (Student 5. Word cards). Another student indicated that "it motivates us to work collaboratively to decide on the drawing we can make to represent the words" (Student 10. Association with pictures). The benefits of collaboration among students when learning vocabulary were also noted by Trujillo, Alvarez, Samudio, and Morales (2015) with high school students from three schools from different regions of Colombia. The authors found that "the students felt confident when they had the opportunity to negotiate and solve problems through interaction with classmates rather than asking the teacher for help because the students' peers are often at the same level of thought" (p. 255). In sum, the findings of the study highlighted that when factors such as the management of the strategy supply learners' need to manipulate didactic materials (Brown, 2007), and the interaction with their peers allowed students to overcome their difficulties, students could learn to use a specific vocabulary strategy and encourage their mutual support (Oxford, 1990).

Cognitive Factors of Vocabulary Strategies

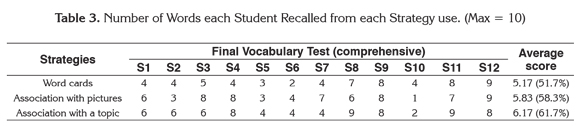

The data showed that almost all of these students, who had never used any of the three strategies before, benefited from using memory strategies to learn vocabulary (see Table 3). The strategies were tools that allowed the students to learn, memorize, and recall the meaning of words. Additionally, these strategies helped learners be more aware of the spelling of words as seen in the following comments from the students: "before, I didn't have any idea about how to improve my vocabulary and how to memorize words" (Student 4. First questionnaire. Word cards), and, "when the teacher or a classmate asks me the meaning of the words, both the image and the spelling come to my mind" (Student 2. Second questionnaire. Word cards and association with pictures).

Questionnaires reported that when the students started improving their range of words, they started improving reading comprehension at the same time. This indicates the importance of learning vocabulary to master a second language (Schmitt, 2008). This can be seen in the following answers: "Because I had already learned the vocabulary in the reading, I didn't have problems to understand it" (Student 10. First questionnaire. Association with pictures).

Each vocabulary strategy helped learners develop different learning skills. Word cards allowed students to rely on their first language to support their vocabulary learning, as said by Student 6: "I used to forget the meaning of the words, but now, thanks to the cards, I can remember their meaning perfectly."

Association with pictures was more of a personal strategy because learners found it difficult to figure out the meaning of the words from other pictures different from their own. This allowed learners to use their imagination to make associations between their background knowledge of the meaning of the words, a concrete experience or a direct perception, and the way learners used this information to illustrate the words. This fostered them to interact with their peers to share ideas about how to better represent the meaning of the words to avoid misunderstandings: "It motivates us to interact in order to decide on the picture we should draw to represent the words" (Student 10. Association with pictures).

Association with a topic required the students to use their thinking skills to determine how they could represent the connection they had devised among the words in a word-map. This strategy demanded a higher level of association and concentration than the other two strategies because they had to make appropriate connections between each word and its topic to recall the meaning of the words which was not easy for them. The students started interacting with their peers by asking for the meaning of the words and sharing ideas about how to connect them. By using this social strategy, the teacher-researcher found that when students face a cognitively demanding task, they try to overcome their difficulties or lack of expertise through mutual support.

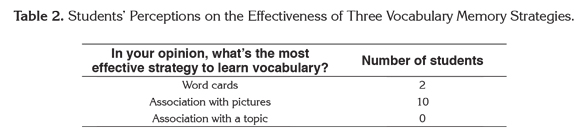

The data indicated (see Table 2) that the students' preference for a strategy depended on how easy they considered it to be and how useful it was for the learning of the words. In addition, they seemed to associate the level of difficulty of a strategy with its effectiveness for the recalling of words. An example of this is the comment of Student 4 about Association with Pictures, when he said: "Memorizing the words was really easy with this strategy, that's why I think it was very effective." (Question 5. Second questionnaire. Comparing the three memory strategies).

Nevertheless, when the students' perception was compared with the final vocabulary test (see Table 3), it was found that although the students believed that association with pictures better helped them to remember the words, they had a better performance with association with a topic which was not considered to be used in the near future.

The students rejected the idea of considering the use of the strategy of association with a topic because they considered that it was boring, difficult, and useless to learn vocabulary. The fact that the strategy they liked the least was the same that yielded the best results in terms of vocabulary retention at the end of the intervention (Table 3) provides the teacher-researcher with valuable material for reflection. In principle, this finding seems to contradict the idea that the more interesting the activities, the more students will learn. It is clear that the students thought the strategy was not as fun as the other two. Moreover, as the teacher-researcher realized early on in the intervention, this strategy had the students make efforts to meet its higher cognitive demand. Actually, as found by Oxford (1990), this strategy forces students to use their thinking skills to work with the words. In other words, this strategy was more demanding for the students because it was more difficult. However, this does not mean that the students did not acknowledge its effectiveness. As Student 10 pointed out, "this strategy is helpful because when I remember one word, I can also associate it with other words I have learned," and this is only one of the positive comments students made about this strategy. Interestingly enough, the students figured out ways to develop the academic burden that this activity represented and made it more interesting to them by combining it with other activities they thought were more fun, as the drawing of pictures. This is what the teacherresearcher found and wrote in the research journal: "They began by asking one another the meaning of the words and sharing ideas about which pictures could better illustrate their words, how to better connect the words and how to represent that connection on the semantic map." The outcome was that the association with a topic became the most successful strategy according to the outcome of the final vocabulary test (Table 3). However, it cannot be ignored that the association with the topic was the last strategy the students applied when they had already had experience with the other two and this fact enabled them to combine the strategies, something that could also explain why students had a higher score in this strategy.

Their preference for using pictures over other resources may indicate that these learners had a visual learning style; consequently, they were more willing to learn the meaning of words by associating them to pictures. Thus, it is possible to hypothesize that the preference for a strategy will depend on how comfortable students feel when using it, a fact which influences heavily their perception of its effectiveness, instead of basing their choice on the scores earned in a test.

Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate consistency with the theory and previous research studies in that it increased vocabulary learning rate and improved language skills. These strategies enable learners to expand their range of words, develop their ability to retain words and recall them, and give the students a sense of improvement in their reading skills despite the fact that this study did not have this focus.

Vocabulary strategies involve both affective and cognitive factors that may cause the students to prefer one strategy over another. Hence, in order for learners to decide which vocabulary strategy to use, they need to consider it an innovative, interesting, motivating, and fun tool as well as easy to handle for the learning and the recalling of the words. However, the cognitive level of a strategy might affect their motivation and might cause them to believe that one strategy is more or less effective for vocabulary retention than the others. The students judged the strategy of association with a topic as a boring and difficult. This is why they indicated that they would not choose to use it in the future although they were better able to recall words by using it. From the students' perspective, vocabulary strategies can be seen as didactic tools when they become part of a self-instructional approach to learning new vocabulary. The study showed that after students became acquainted with each strategy, they customized it to fit their own learning style and/or they tended to use social strategies which involved asking questions and collaborating with their peers to overcome their difficulties. Evidence of this collaboration can be seen in Figure 1.

Hence, these memory-based strategies turned into metacognitive strategies (MS) as the way they were performed by the students complies with the characteristics of Chamot's (2009) definition which suggests that metacognitive strategies are "executive processes used in planning for learning, monitoring one's own comprehension, production and evaluating how well one has achieved a learning objective" (p. 58).

Word cards fostered learners' recall of words by using their first language and by learning words easily (Nation, 2008). Association with pictures moved the learner from relying on the first language to using their imagination to visualize and represent accurately the meaning of the words (Thornbury, 2004). Association with a topic forced learners to use their thinking skills to make mental connections among words and to build up a clear network of words (Oxford, 1990). All of the participants decided to cooperate with their peers and interact with them by asking questions to clarify the meaning of the words and to share ideas with their peers to ensure an appropriate illustration of the meaning of the words in the pictures and an appropriate connection of words in the map. Hence, vocabulary strategies can foster students to become more autonomous and responsible for their own learning.

Pedagogical Implications

Applying vocabulary strategies to students with low levels of language requires thinking about several issues related to the materials, the strategy itself, and feedback. First, the selection of reading materials should be based on the students' ages, language level and interests in order for learners to have a sense of improvement when they are applying the strategies. The numbers of the words should not greatly exceed the students' reading understanding, and the materials should give them the chance to have repeated exposure to the words to ensure their learning. Second, the strategies need to be explained and modeled by the teacher, and students need to be provided with opportunities to practice them in class so they can overcome the difficulties they may have under the teacher's guidance. Third, it is important to evaluate the vocabulary strategy because testing is a type of feedback (Thornbury, 2004). In this way, teachers can know whether or not the strategies are helping students to increase their vocabulary and what strategies better fit their students' learning styles.

The general curriculum and the English classes need to incorporate vocabulary strategies as a way to provide opportunities for learners to select or combine them to overcome their difficulties of learning and recalling words. Because words are important to convey meaning, educators should introduce vocabulary strategies in their writing, speaking, reading, and listening lessons so learners start expanding their range of words, enriching their learning skills, and developing their language skills.

Further research on vocabulary strategies at the primary level could bring more insights into their effect on vocabulary learning and on the development of language skills. In the case of reading, an improvement in this skill was found; however, an in-depth study would be needed to establish this aspect more precisely. Finally, this research has hypothesized that students' learning styles may influence their preference for a specific strategy over other strategies in spite of the scores they may have in their vocabulary tests. This study was not intended to prove if students prefer strategies that fit their learning styles, but the data highlight this relationship. Further research should be developed to corroborate this finding. Each participant could take a learning style test and the strategy or strategies should be chosen based on the results of the test.

References

Ae-Hwa K., Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., & Wei, S. (2004). Graphic organizers and their effects on the reading comprehension of students with LD: A synthesis of research. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37(2), 105-18. doi:10.1177/00222194040370020201

Anderson, J. P., & Jordan, A. M. (1928). Learning and retention of Latin words and phrases. Journal of Educational Psychology, 19, 485-496. doi:10.1037/h0073011

Arias, L. D. (2003). Memory? no way! Folios, 18, 115-120.

Bos, C. S., & Anders, P. L. (1990). Effects of interactive vocabulary instruction on the vocabulary learning and reading comprehension of junior-high learning disabled students. Learning Disability Quarterly, 12(1), 31-42. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1510390

Brown, H. D. (2007). Principles of language learning and teaching (5th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson Education. Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching languages to young learners. London: Cambridge University Press.

Cárdenas, M. (2001). The challenge of effective vocabulary teaching. Profile, 2(1),48-56. Retrieved from http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/index

Catalan, R. M. J. (2003). Sex differences in L2 vocabulary learning strategies. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 13(1), 54-77.

Chamot, A.U. (2009). The CALLA handbook: Implementing the cognitive academic language learning approach (2nd ed.). White Plains, NY: Pearson Education/Longman.

Colombia, M. (2001). Improving new vocabulary learning in context. Profile, 2(1), 22-24. Retrieved from http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/index

DeWitt, K. C. (2010). Keyword mnemonic strategy: A study of SAT vocabulary in high school English (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3421702).

Folse, K. (2004). Vocabulary myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching. USA: Michigan.

Ghazal, L. (2009). Learning vocabulary in EFL contexts through vocabulary learning strategies. Novitas- ROYAL, 1(2), 84-91.

Goll, P. (2004). Mnemonic strategies: Creating schemata for learning enhancement. Education, 125(2), 306-312.

Hong, P. (2009). Investigating the most frequently used and most useful vocabulary language learning strategies among Chinese EFL postsecondary students in Hong Kong. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 6(1), 77-87.

Idol, L., & Croll, V. (1987). Story-mapping training as a means of improving reading comprehension. Learning Disability Quarterly, 10, 214-229. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/ stable/1510494

Kojic-Sabo, I., & Lightbown, P. M. (1999). Students' approaches to vocabulary learning and their relationship to success, Modern Language Journal, 83, 176-192. doi:10.1111/0026-7902.00014

Kusumarasdyati. (n.d.). Vocabulary strategies in Reading: Verbal reports of good comprehenders. Retrieved from http://www.aare.edu.au/06pap/kus06083.pdf

Mastropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E. (1998). Enhancing school success with mnemonic strategies. Intervention in School and Clinic, 33(4), 201-201. doi:10.1177/105345129803300402

Mediha, N, & Enisa, M. (2014). A comparative study on the effectiveness of using traditional and contextualized methods for enhancing learners' vocabulary knowledge in an EFL classroom. 5th World Conference on Educational Sciences, (116), 3443-3448. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.780

Nakata, T. (2008). English vocabulary learning with word lists, word cards and computers: Implications from cognitive psychology research for optimal spaced learning. ReCALL, 20(1), 3-20. doi:10.1017/ S0958344008000219

Nation, I.S. P. (1990). Teaching and learning vocabulary. New York, NY: Heinle and Heinle.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Nation, I. S. P. (2008). Teaching vocabulary: Strategies and techniques. Boston, MA: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Nunan, D. (1992). Collaborative language learning and teaching. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Oberg, A. (2011). Comparison of the effectiveness of a CALL-based approach and a card-based approach to vocabulary acquisition and retention. CALICO Journal, 29(1), 118. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ez.unisabana.edu.co/docview/916751780?accountid=45375

Obringer, L. A. (2001). The psychology of learning. Retrieved August 12, 2012 from http://people.howstuffworks.com/elearning2.htm

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies. What every teacher should know. Boston, MA: Heinle and Heinle.

Pérez, L. M. (2013). The acquisition of vocabulary through three memory strategies. (Unpublished master's thesis, Universidad de la Sabana, Chia, Colombia). Retrieved from: http://intellectum.unisabana.edu.co/handle/10818/6657

Pigada, M., & Schmitt, N. (2006). Vocabulary acquisition from extensive reading: A case study. Reading in a foreign language, 18(1),1-28. Retrieved from http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/

Pineda, J. (2010). Identifying language learning strategies: An exploratory study. Gist Education and Learning Research Journal, 4(1), 94-106. Retrieved from www.unica.edu.co/archivo/GIST/2010/07_2010.pdf

Pressley, M., Levin, J.R., & Delaney, H. (1982). The mnemonic keyword method. Review of Educational Research 52(1), 61-91. doi:0.3102/00346543052001061

Rivers, W. (1983). Communicating naturally in a second language. NY: CUP.

Rott, S. (1999). The effect of exposure frequency on intermediate language learners' incidental vocabulary acquisition through reading. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21(1), 589-619.

Sanaoui, R. (1995). Adult learners' approaches to learning vocabulary in second languages. The Modern Language Journal, 79(1), 15-28. doi: 10.1111/ j.1540-4781.1995.tb05410.x

Scarcella, R. C., & Oxford, R. L. (1992). The tapestry of language learning: The individual in the communicative classroom. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Schmitt, N. (2008). Review article: Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research,12, 329-363.doi: 10.1177/1362168808089921

Schmitt, N., & Schmitt, D. (2014). A reassessment of frequency and vocabulary size in L2 vocabulary teaching. Language Teaching, (47), 484-503 doi: 10.1017/S0261444812000018

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). The basic of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedure and techniques. (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications.

Thornbury, S. (2004). How to teach vocabulary. (3rd Ed). England, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

Trujillo, C. L., Álvarez, C. P., Zamudio, M. N., & Morales, G. (2015). Facilitating vocabulary learning through metacognitive strategy training and learning journals. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 246- 259. doi: 10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a05

Wallace, M. (2008). Action research for language teachers. London, UK: Cambridge university press.

Waring, R., & Takaki, M. (2003). At what rate do learners learn and retain new vocabulary from reading a graded reader? Reading in a Foreign Language, 15(2), 130-163. Retrieved from http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/doi:10.1177/1362168806072463

Wilkins, D. A. (1972). Linguistics in language teaching. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.