DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v19n1.10219Published:

2017-02-10Issue:

Vol 19, No 1 (2017) January-JuneSection:

Research ArticleseTandem language learning and foreign language anxiety among colombian learners of german

Aprendizaje en eTándem y la ansiedad en el aprendizaje de idiomas entre estudiantes de alemán en Colombia

Keywords:

ansiedad, aprendizaje de idiomas en eTandem, colaboración en línea, alemán como lengua extranjera (es).Keywords:

anxiety, eTandem Language Learning, online collaboration, German as a foreign language (en).Downloads

References

Appel, M. C. (1999). Tandem Language Learning by E-mail: Some Basic Principles and a Case Study. CLCS Occasional Paper No. 54. Dublin: Trinity College.

Appel, C., & Gilabert, R. (2002). Motivation and task performance in a task-based web-based tandem project. ReCALL, 14(1), 16-31. doi: 10.1017/S0958344002000319

Appel, C., & Mullen, T. (2000). Pedagogical Considerations for a Web-based Tandem Language Learning Environment. Computers and Education, 34, 291–308. doi:10.1016/S0360-1315(99)00051-2

Bower, J., & Kawaguchi, S. (2011). Negotiation of Meaning and Corrective Feedback in Japanese/English eTandem. Language Learning & Technology, 15(1), 41–71. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/issues/february2011/bowerkawaguchi.pdf

Brammerts, H. (2005). Autonomes Fremdsprachenlernen im Tandem: Entwicklung eines Konzepts. In Brammerts H., & Kleppin K. (Eds.), Selbstgesteuertes Sprachenlernen im Tandem. Ein Handbuch (pp. 9-16), Tübingen: Narr.

British Council. (2015). English in Colombia: An examination of policy, perceptions and influencing factors. Retrieved from https://ei.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/latin-america-research/English%20in%20Colombia.pdf

Bueno-Alastuey, M. C. (2013). Interactional Feedback in Synchronous Voice-based Computer Mediated Communication: Effect of Dyad. System, 4(3), 543–559. doi:10.1016/j.system.2013.05.005

Clavijo Olarte, A., Hine N. A., & Quintero L. M. (2008). The virtual forum as an alternative way to enhance foreign language learning. Profile, 9, 219-236. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S1657-07902008000100013&script=sci_arttext

Cziko, Gary A. (2004). Electronic tandem language learning (eTandem): A third approach to second language learning for the 21st century. CALICO Journal, 22(1), 25-39. Retrieved from https://calico.org/html/article_172.pdf

de Dios Martínez Agudo, J. (2013). An investigation into how EFL learners emotionally respond to teachers' oral corrective feedback. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(2), 265-278. Retrieved from http://revistas.udistrital.edu.co/ojs/index.php/calj/article/view/5133/6743

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language acquisition: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Gardner, R. C. & MacIntyre P. (1992). A student's contribution to second language learning. Part I: Cognitive variables. Language Teaching, 25, 211-220.

Goethe-Institut. (2014). Ergebnis der gemeinsamen DaF-Umfrage Kolumbien von DAAD, Goethe-Institut, kolumbianischem Deutschlehrerverband APAC und deutscher Botschaft Bogotá von 10-12/2013. Retrieved from http://www.goethe.de/resources/files/pdf16/Deutsch_in_Kolumbien_2014-041.pdf

Gogolin, I. & Neumann, U. (1991). Sprachliches Handeln in der Grundschule. Die Grundschulzeitschrift, 43, 6-13.

Hampel, R. (2006). Rethinking Task Design for the Digital Age: A Framework for Language Teaching and Learning in a Synchronous Online Environment. ReCALL, 18(1), 105–121. doi:10.1017/S0958344006000711

Hilleson, M. (1996). I want to talk with them, but I don’t want them to hear: an introspective study of second langue anxiety in an English-medium school. In K. M. Bailey & D. Nunan (Eds.), Voices from the Language Classroom (pp. 248–282). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/327317

Jin, L., & Erben, T. (2007). Intercultural Learning via Instant Messenger Interaction. CALICO Journal, 24(2), 291–311. Retrieved from https://www.calico.org/html/article_646.pdf

Kötter, M. (2002). Tandem Learning on the Internet: Learner Interactions in Virtual Online Environment (MOOs). Frankfurt/Main: Lang.

Krumm, H.-J. & Jenkins, E.-M. (2001). Kinder und ihre Sprachen – lebendige Mehrsprachigkeit. Wien: Eviva

Lee, L. (2004). Learners’ Perspectives on Networked Collaborative Interaction with Native Speakers of Spanish in the US. Language Learning & Technology, 8(1), 83–100. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol8num1/pdf/lee.pdf

Little, D., Ushioda, E., Appel, M. C., Moran, J., O’Rourke, B., & Schwienhorst, K. (1999). Evaluating Tandem Language Learning by E-mail: Report on a Bilateral Project. CLCS Occasional Paper No. 55. Dublin: Trinity College.

Liu, H. (2012). Understanding EFL undergraduate anxiety in relation to motivation, autonomy and language proficiency. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 9(1), 123-139. Retrieved from http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/v9n12012/liu.pdf

Liu, H., & Chen, C. (2015). A comparative study of foreign language anxiety and motivation of academic- and vocational-track high school students. English Language Teaching, 8(3), 193-204. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1075211.pdf

Liu, M., & Huang, W. (2011). An Exploration of Foreign Language Anxiety and English Learning Motivation. Education Research International. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2011/493167

Liu, M., & Jackson, J. (2008). An exploration of Chinese EFL Learners’ unwillingness to communicate and foreign language anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 92(1), 71-86. doi:10.5430/elr.v2n1p1

Lu, Z., & Liu, M. (2011). Foreign language anxiety and strategy use: A study with Chinese undergraduate EFL learners. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 2(6), 1298-1305. doi: 10.4304/jltr.2.6.1298-1305

MacIntyre, P. & Gardner, R.C. (1994). The Subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language. Language Learning, 44(2), 283-305. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01103.x

MacIntyre, P. & Gregersen, T. (2012). Affect: The role of language anxiety and other emotions in language learning. In Mercer, D., Ryan, S., & Williams, M. (Eds.), Psychology for Language Learning: Insights from Research, Theory & Practice (pp. 103-118). London: Palgrave.

Mayring, P. (2008). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. 10. Aufl., Weinheim, Basel: Beltz.

O’Dowd, R. (2010). Online foreign language interaction: Moving from the periphery to the core of language education. Language Teaching, 44(3), 368-380. doi: 10.1017/S0261444810000194

O'Dowd, R., & Ware, P. (2009). Critical Issues in Telecollaborative Task Design. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 22(2), 173–188. doi:10.1080/09588220902778369

Ohata, K. (2005). Potential sources of anxiety for Japanese learners of English: Preliminary case interviews with five japanese college students in the U.S. TESL-EJ, 9(3). Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.org/pdf/ej35/a3.pdf

O’Rourke, B. (2005). Form-focused Interaction in Online Tandem Learning. CALICO Journal, 22(3), 433–466. Retrieved from https://calico.org/html/article_144.pdf

O’Rourke, B. (2007). Models of Telecollaboration (1): eTandem. In O’Dowd, R. (Ed.), Online Intercultural Exchange. An Introduction for Foreign Language Teachers (pp. 41–61). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Pérez-Paredes P. F., & Martínez-Sánchez, F. (2000-2001). A spanish version of the foreign language classroom anxiety scale: revisiting Aida's factor analysis. RESLA, 14, 337-352, Retrieved from http://www.ehu.eus/ojs/index.php/psicodidactica/article/download/1162/4028

Sellers, V. D. (2000). Anxiety and reading comprehension in Spanish as a foreign language. Foreign Language Annuals, 33(5), 512-520. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2000.tb01995.x

Sotillo, S. (2005). Corrective Feedback via Instant Messenger Learning Activities in NS-NNS and NNS-NNS Dyads. CALICO Journal, 22(3), 467–496. Retrieved from https://calico.org/html/article_145.pdf

Tian, J., & Wang, Y. (2010). Taking Language Learning Outside the Classroom: Learners’ Perspectives of eTandem Learning via Skype. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 4(3), 181–197. doi:10.1080/17501229.2010.513443

Ushioda, E. (2000). Tandem language learning via e-mail: from motivation to autonomy. ReCALL, 12,121-128. doi: 10.1017/S0958344000000124

Vassallo, M. L., & Telles J. (2006). Foreign Language Learning In-tandem: Theoretical Principles and Research Perspectives. The ESPecialist, 27(1), 83-118. Retrieved from http://www.corpuslg.org/journals/the_especialist/issues/27_1_2006/artigo5_Vassalo&Telles.pdf

Wang, Y. (2007). Task Design in Videoconferencing-supported Distance Language Learning. CALICO Journal, 24(3), 591–630. Retrieved from https://www.calico.org/html/article_662.pdf

Wang, Y., & Chen, N. (2012). The Collaborative Language Learning Attributes of Cyber Face-to-face Interaction: The Perspectives of the Learner. Interactive Learning Environments, 20(4), 311–330. doi:10.1080/10494821003769081

Ware, P., & O'Dowd, R. (2008). Peer Feedback on Language Form in Telecollaboration. Language Learning & Technology, 12(1), 43–63. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol12num1/pdf/wareodowd.pdf

Yan, J. X., & Horwitz, E. K. (2008). Learners‘ Perceptions of how anxiety interacts with personal and instructional factors to influence their achievement in English: A qualitative analysis of EFL learners in China. Language Learning, 58(1), 151-183. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00437.x

Yilmaz, Y., & Granena, G. (2010). The Effects of Task Type in Synchronous Computer-Mediated Communication. ReCALL, 22(1), 20–38. doi:10.1017/S0958344009990176

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/calj.v19n1.10219

RESEARCH ARTICLES

eTandem Language Learning and Foreign Language Anxiety among Colombian learners of German

Aprendizaje en eTándem y la ansiedad en el aprendizaje de idiomas entre estudiantes de alemán en Colombia

Yasmin El-Hariri

University of Vienna, Austria. yasmin.el-hariri@univie.ac.at

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: El-Hariri, Y. (2017). eTandem Language Learning and Foreign Language Anxiety among Colombian learners of German.

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 19(1), pp. 22-36

Received: 30-Mar-2016 / Accepted: 21-Sept-2016

Abstract

Although eTandems, offering the opportunity of real life contact to speakers of one's target language, are suggested as an anxiety-reducing, confidence-increasing approach to language learning (Appel & Gilabert, 2002), these effects have not been investigated empirically. The aim of this xxxxxxxxx is to explore the experiences and perceptions of 11 Colombian learners of German as a foreign language who participated in a German-Spanish eTandem project. Data were collected by means of interviews and focus groups, and evaluated using qualitative content analysis. Results support the anxiety-reducing and confidence-raising nature of eTandem Language Learning. eTandems show to have great potential to reduce the fear of using German in real life situations. These perceptions, however, are not in every case transferable into the language classroom.

Keywords: anxiety, eTandem Language Learning, telecollaboration, German as a foreign language

Resumen

Aunque se ha sugerido que los eTandem son un método que reduce la ansiedad y aumenta la confianza (Appel & Gilabert, 2002), al ofrecer la oportunidad de tener interacciones reales con hablantes de la lengua meta, dichos efectos no han sido investigados empíricamente. El objetivo de este artículo es explorar las experiencias y la percepción de 11 estudiantes de alemán como lengua extranjera en Colombia, quienes participaron en un proyecto de eTandem alemán-español. Los datos fueron recogidos mediante entrevistas y grupos focales, y evaluados usando análisis de contenido cualitativo. Los resultados muestran que el aprendizaje de idiomas mediante eTandem puede reducir el miedo a hablar y al mismo tiempo aumentar la confianza en el aprendizaje de un idioma extranjero. El análisis sugiere que los eTandem tienen el potencial para reducir el temor de usar el idioma en situaciones reales. Sin embargo, estos efectos no son siempre transferibles al aula de aprendizaje.

Palabras clave: ansiedad, aprendizaje de idiomas en eTandem, colaboración en línea, alemán como lengua extranjera.

Introduction

German, as a geographically distant language, is very little represented in Colombia. According to the Goethe Institut (2014), around 13,000 people all over the country (less than 0.03% of the total population) learned German as a foreign language in 2014. In comparison, English is learned by over 11.5 million Colombians or 25% of the total population (British Council, 2015). Likewise, other than English, which is widely present and accessible through media, communication, and tourism, German is barely visible or audible in Colombia, and for learners of German as a foreign language the only contacts with German speaking people usually consist of the interactions with their language teachers.

In addition, according to Clavijo Olarte, Hine, and Quintero (2008) language teachers in Colombia "believe that knowing the structures of the target language is the most important source required to speak it" (p. 220). The authors further point out that research "has demonstrated that language structures need to serve a real purpose for language use in order for the language to be learned" (p. 220). By using a language in interaction, learners may seize the opportunity to actually put into practice the forms and structures acquired within foreign language classes.

eTandem Language Learning (eTLL) is an approach that offers such real purpose for language use by enabling learners to communicate via the Internet with speakers of their target language who, at the same time, are learners of their own language (e.g., Cziko, 2004). On the basis of mutual exchange, it helps overcome distances by facilitating real life contacts with German speaking people (El-Hariri et al., 2016). Moreover, eTLL is described as a method that "encourages familiarity and solidarity, reduces anxiety and, over time, increases confidence" (Appel & Gilabert, 2002, p. 18). This aligns with the perception of Colombian students who expect eTandems to reduce their fears of speaking and/or committing errors and at the same time increase their self-confidence when using the foreign language (El-Hariri & Jung, 2015). Yet, to date, no empirical studies provide evidence of the anxiety-reducing and confidence-increasing nature of eTLL. The present paper thus presents an attempt to provide insights into how eTandem Language Learning may affect foreign language anxiety.

Literature Review

Language Anxiety

Among many researchers, anxiety is regarded as one of the most powerful individual factors when it comes to language learning. Together with other affective variables such as motivation and attitudes, foreign language anxiety plays an important role throughout the whole learning process. It has been thoroughly investigated within the field of second language acquisition (SLA) and individual learner differences, and is nowadays recognized as a particularly outstanding affective variable in language learning (Gardner, 1985; Horwitz, Horwitz, & Cope, 1986; MacIntyre & Gardner, 1994).

Anxiety in general is perceived as the "subjective feeling of tension, apprehension, nervousness, and worry associated with an arousal of the autonomic nervous system" (Horwitz et al., 1986, p. 125). MacIntyre and Gardner (1994) define language anxiety as "the feeling of tension and apprehension specifically associated with second language contexts including speaking, listening, and learning" (p. 284), while a later definition by MacIntyre and Gregersen (2012) describes language anxiety as "a term that encompasses the feelings of worry and negative, fear-related emotions associated with learning or using a language that is not an individual's mother tongue" (p. 103).

In their much-quoted xxxxxxxxx, Horwitz et al. (1986) aimed at identifying foreign language anxiety as a "conceptually distinct variable" in foreign language learning, describing symptoms and consequences of foreign language anxiety on both the learners themselves as well as their learning outcomes. These consequences on learning outcomes have been confirmed in various studies describing a negative correlation between language anxiety and achievement (e.g. Gardner, 1985; Gardner & MacIntyre, 1992).

Horwitz et al. (1986) furthermore classified three types of foreign language anxiety: communication apprehension, test anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation. In order to measure a learner's degree of language anxiety, the researchers developed the 33-item Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS), measuring individuals' degrees of language anxiety.

More recent research has focused on the correlation between anxiety and motivation (e.g. Liu & Chen, 2015; Liu & Huang, 2011). Liu and Huang (2011), for example, found a significant negative correlation between foreign language anxiety and English learning motivation among undergraduate students from Chinese universities. Results of other studies, also conducted among Chinese learners of English as a foreign language, show highly significant negative correlations between foreign language anxiety and learning motivation, listening proficiency, reading proficiency, learner autonomy (Liu, 2012), as well as a significant positive correlation between foreign language anxiety and unwillingness to communicate (Liu & Jackson, 2011). Moreover, Lu and Liu's (2011) study revealed that approximately one third of their respondents felt anxious in their English classes, and that this anxiety acted as a negative predictor of the students' performance in the foreign language.

Only a few studies have been engaged in examining language anxiety from the learner's perspective. In a qualitative study, Yan and Horwitz (2008) analyzed learners' perceptions of how anxiety interacts with other personal and institutional variables. They identified twelve major affinities influencing language learning: regional differences, language aptitude, gender, foreign language anxiety, class arrangements, teacher characteristics, language learning strategies, test types, parental influences, comparison with peers, and achievement (Yan & Horwitz, 2008). Another attempt to explore language anxiety from the learner's point of view is Ohata's (2005) study, identifying cultural norms or expectations acquired through various socialization processes as potential sources of anxiety among Japanese learners of English. It must be noted, however, that the above mentioned studies focus on English as a foreign language. English, as a more widely audible and visible language, certainly holds a different status in the respective countries (China, Japan) than German, which is very little represented in Colombia.

Although the limited space of this paper does not allow for more than this very brief, and certainly fragmentary, literature review, it can be summarized that foreign language anxiety is determined by a multitude of factors varying from person to person. Research indicates that anxiety is prevalent among foreign language learners, and that foreign language anxiety may involve a series of negative impacts on both the learners themselves and their learning outcomes. A reduction of foreign language anxiety thus is suggested to be essential to not only increase the learners' motivation and willingness to communicate but also to enhance their learning outcomes. As one potential means of reducing foreign language anxiety, this paper focuses on the approach of eTandem Language Learning.

eTandem Language Learning

Language learning in tandem describes an approach that usually involves two learners with different languages learning from and with each other. With the growing availability of the Internet, tandems are no longer limited to face-toface contacts but may be initiated online as well (eTandem). Based on the ideas of non-formal, selfdirected, and transcultural collaborative learning, eTLL allows language learners from all over the world to communicate and interact with each other (Appel, 1999; El-Hariri et al., 2016; Brammerts, 2005; Cziko, 2004; Kötter, 2002; Little et al., 1999; O'Rourke, 2005, 2007; Vassallo & Telles 2006). eTandem communication via the Internet may be realized in different ways. While written interaction through emails or text-chats was prevailing in the late 1990s and early 2000s, audio-visual telecollaboration, e.g., through video-conferencing, establishes itself more and more these days.

Being an emergent area of research, an increasing number of empirical studies concerning telecollaboration and eTLL have been published in recent years, exploring intercultural aspects of eTLL (e.g. Jin & Erben, 2007), negotiation of meaning eTandem Language Learning and Foreign Language Anxiety (Bower & Kawaguchi, 2011; Bueno-Alastuey, 2013; Sotillo, 2005; Ware & O'Dowd, 2008; Yilmaz & Granena, 2010), task design (Hampel, 2006; O'Dowd & Ware, 2009; Wang, 2007), learner perspectives (Lee, 2004; Tian & Wang, 2010; Wang & Chen, 2012), or the role of autonomy and motivation in the context of eTLL (Appel & Gilabert, 2002; Appel & Mullen, 2000; Ushioda, 2000).

However, no publications have been devoted to the relation of eTandem Language Learning and foreign language anxiety. Empirical evidence to describe the role of eTLL with respect to foreign language anxiety is thus needed. The present paper aims at contributing to this field by providing an insight into learners' experiences with eTandem Language Learning.

Context

This study is thematically embedded in the framework of a transnational research project. The project FAME - Fostering Autonomy and Motivation through E-Tandems has been initiated by the University of Vienna and aims at examining how far learners' autonomy and motivation may be encouraged by the use of eTLL as a supplement to foreign language teaching in institutional contexts. The project is funded by Austria's Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy and involves learners of three languages, French, Spanish and German, in Austria, France and Colombia.

Within the project's framework, more than 60 Colombian learners of German as a foreign language have been enrolled in the eTandem program between 2014 and 2016. Throughout these two years, the participants regularly-ideally weekly-interacted with their partners in Austria via video-chat, communicating in both Spanish and German. The learners did not have to fulfil any kind of tasks during the exchange, but could freely choose topics they wanted to discuss with their partner. While the eTandem sessions were organized in a self-directed way between the participants themselves, monthly meetings with a local project supervisor provided the learners with an opportunity to exchange experiences with fellow students at their own institution.

Methodology

The objective of this paper is to explore the perceived interplay of eTandem Language Learning and foreign language anxiety among Colombian learners of German as a foreign language. To meet this target, it addresses the following research questions:

1. Which attitudes do learners show towards German language classes?

2. Which situations make Colombian students feel anxious in their German classes?

3. How can eTandem Language Learning contribute to reducing the learners' feeling of anxiety related to the use of German?

Participants

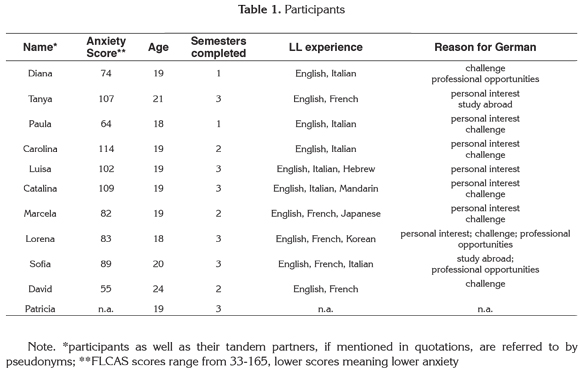

A total of 11 learners of German as a foreign language participated in the present study. All participants, natives of Colombian Spanish, were students enrolled in the modern languages program at the Universidad EAN in Bogotá who had chosen German as their second foreign language after obligatory English. Reasons for choosing German include personal interest (e.g., in the language itself including its grammar and sound, in German speaking countries, their inhabitants and cultures), the challenge (of learning a "difficult" language), as well as professional and educational opportunities (study and/or work abroad). At the moment of data collection, the participants had completed between one and three semesters of German instruction at their home institution (5 hours/week). Additionally, they participated in the above mentioned eTandem project, engaging in regular communication via video-chat with learners of Spanish as a foreign language in Austria.

Table 1 gives an overview of the study's participants, their anxiety score, age, semesters of German completed, language learning experience apart from German, and reasons for choosing German.

Data Collection and Analysis

Mixed methods were applied to collect data from the participants. One-to-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten students in order to gain insights into the learners' language biographies as well as their attitudes towards and experiences with foreign language learning in different contexts. Focus groups were used to elicit more detailed perceptions of eTLL and, in particular, foreign language anxiety.

Anxiety scores were determined by using a Spanish version of Horwitz et al.'s (1986) Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS). Therefore, Pérez-Paredes and Martínez Sánchez› (2000-2001) FLCAS adaptation has been linguistically adjusted together with Colombian native speakers in order to better conform to the Spanish variety used in Colombia.

Interviews and focus groups were transcribed following Hoffmann-Riem's (1984) conventions. In these simple transcripts, "paraverbal and non-verbal elements of communication are usually omitted. The focus of simple transcripts lies on readability" (Dresing, Pehl, & Schmieder, 2015, p. 23). Using simple transcripts also facilitated the subsequent examination adopting qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2008, 2014). Therefore, transcripts were thoroughly examined with respect to the above mentioned research questions. Corresponding answers were selected, extracted, and generalized. On the basis of the thus prepared data, categories were formed inductively. Subsequently the results were summarized and presented according to the research questions.

Procedure

Interviews were conducted in Spanish, and covered a range of topics related to languages and language learning. To plunge into the subject, participants were asked to create a 'language portrait' (Gogolin & Neumann, 1991; Krumm & Jenkins, 2001). This technique, which includes coloring a template's body parts according to one's languages, constitutes a low-threshold starting point to talk about the learners' linguistic backgrounds and their language learning biographies. The following interviews then focused on various aspects of language learning:

• Attitudes towards German (motivation to

choose German, contact with German speaking

persons)

• Reflection of institutional experiences

(perception of German classes, feelings of

anxiety in class)

• Reflection of eTLL experiences (motivation to

participate, experiences gained)

• Language learning and affect (feelings in class,

feelings in eTandem, differences between both)

Instead of a more "traditional" interview setting with the interviewer asking questions and the interviewee responding, a set of consecutive prompts (9 in total) was applied to elicit the students' perceptions and opinions on these topics. At the end of each interview, participants were asked to complete the FLCAS.

Focus groups took place five weeks after the interviews. Eleven students took part in one of four focus groups, including all ten learners who had previously participated in the interviews. The participants' interaction was then prompted by quotations from the previously conducted interviews, which had been transcribed in the meantime. Quotations included subjects such as the role of speaking within language instruction, the perceived benefits of participating in eTLL, the perceived progress made, topics of conversation, emotions, and perceived impacts of eTLL on German classes. For the present paper, I mainly focused on the latter two, attempting to provide a deeper insight into the anxiety-reducing, confidence-increasing potential of eTandem exchanges.

Both interviews and focus groups were recorded with the participants' consent. Data were initially transcribed literally including pauses, expletives, repetitions, and non-verbal reactions such as laughter. For the following qualitative analysis as well as for quotations in this paper, however, elements that are not relevant to the content were eliminated.

Findings and Discussion

Results of the data analyses are presented conforming to the research questions. First, we look into the participants' attitudes towards their German classes, then we examine the situations that cause anxiety among the learners, and finally we focus on eTandem Language Learning, how it differs from language learning in institutional contexts and how it may contribute to reducing foreign language anxiety. The learners' statements are quoted verbatim from the original transcripts and literally translated into English, for which reason some statements may not be fully syntactically and/or grammatically correct.

(1) Attitudes Towards German Classes: "Cuando pienso en mis clases de alemán…"

In order to determine the participants' attitudes towards learning German, they were asked about what occurs to them when thinking about their classes. Answers indicate that most learners like their German classes, enjoy them, and feel that they learn a lot:

Cuando pienso en mis clases de alemán, soy feliz, sí me gustan mucho porque aprendo mucho. [When I think of my German classes, I'm happy, I like them a lot because I learn a lot.] (Diana, interview)

Some students also mentioned difficulties, for example Tanya, who, although having faced obstacles, is aware of the fact that these are part of her language learning process:

me gustan y aprendo mucho. Sé que hay dificultades, pero de eso se tratan las clases, para ir a aprender. [I like them and I learn a lot. I know that there are difficulties, but that's what classes are about, to go and learn.] (Tanya, interview)

Paula's thoughts also referred to the learning process as such, yet her considerations went more into detail:

Cuando pienso en mis clases de alemán, pienso mucho en el proceso, en el desarrollo, en cuanto he avanzado o cuanto he mejorado y lo que me falta. [When I think of my German classes, I think a lot about the process, the development, about how much I have progressed or improved and what is still missing.] (Paula, interview)

Two learners, Luisa and Catalina, mentioned feelings of anxiety. However, these do not seem to have negative effects on their generally positive attitudes towards language learning. Instead, Luisa perceived her fear as a challenge:

A veces entro como con miedo a tal vez, por ejemplo, no coger el tema que estamos trabajando, pero entonces sí lo siento a veces como un reto. [Sometimes I go there like with fear of maybe, for example, not understanding the topic which we are working on, but then yes I sometimes perceive it as a challenge.] (Luisa, interview)

Catalina described how her feelings changed from fear due to the great differences between German and Spanish to wishing that classes were more intense:

Al principio me daban mucho temor… porque cuando empecé, me empecé a dar cuenta que había muchas diferencias con el español, muchos pensábamos que no vamos a ser capaces, y a medida que pasó el tiempo, fui cogiendo más confianza. Me gustan mis clases de alemán, me gustan mis profesores de alemán, me gustaría que tal vez fueran más intensas. [At the beginning they caused a lot of fear…because when I started I started to realize that there are many differences with respect to Spanish, many of us thought that we are not going to be able, and over a period of time, I gained more confidence. I like my German classes, I like my German teachers, I would like that they were maybe a bit more intensive.] (Catalina, interview)

Also for David, the intensity of German classes alone is not sufficient. He stated that he also had to study outside the classroom:

Con las solas clases no es suficiente, por fuera tengo que practicar, entonces siempre estoy viendo que me faltó hacer en clase y cómo puedo hacerlo en mi tiempo libre. [With the classes alone it's not enough, outside I have to practice, thus I'm always looking what I didn't do in class and how I can do that in my free time.] (David, interview)

Despite (or sometimes even due to) those challenges, all participants generally showed positive attitudes towards learning German and towards their German classes at the University.

(2) Anxiety-Evoking Situations: "A veces me pongo nervioso/a en la clase de alemán"

The statement above was used as a prompt to elicit situations in language classes that make learners feel anxious. Reasons for anxiety during German class among the participants include their own perceived weaknesses, timidity, new topics, fear of being watched and/or listened to by others, fear of not knowing how to answer questions, fear of not understanding a topic, fear of speaking both in a foreign language and speaking in front of others in general, and fear of committing errors. Only two participants stated being little or not anxious:

Antes de que entré a la universidad, dije si voy a aprender un idioma me tengo que equivocar… para qué me ponga nervioso, para qué me asusto, si yo supiera no estaría acá. [Before I entered the university, I said if I'm going to learn a language, I have to make mistakes…why should I be nervous, why should I be frightened, if I knew, I wouldn't be here.] (David, interview)

No, la verdad no me pasa mucho. Al principio de la clase sí… entendí que uno… no tiene que ponerse nervioso para hablar porque en fin de cuentas estás acá para eso. [No, honestly, that doesn't happen to me much. At the beginning of the classes yes…I understood that one…doesn't have to be nervous about speaking because at the end of the day you are here for that.] (Paula, interview)

Both answers correspond with the learners' results in the FLCAS indicating low levels of anxiety (see Table 1).

Answers to how they feel when actually speaking during their language classes ranged from nervous, anxious, doubtful and not completely good to eTandem Language Learning and Foreign Language Anxiety weird or confused to now better than before, happy and fulfilled. Negative emotions like nervousness, anxiety, and doubts thereby arise from a lack of confidence in their own proficiencies like Tanya:Me siento a veces con miedo por mis debilidades; me cuesta mucho la parte de escuchar y entender. [Sometimes I feel afraid because of my weaknesses; I struggle a lot with the listening and understanding parts.] (Tanya, interview)

Catalina, one of the students with the highest anxiety scores in this study, reported feeling anxious when talking in front of other people:

Me siento nerviosa cuando estoy delante muchas personas. [I feel nervous when I'm in front of many people.] (Catalina, interview)

This phenomenon repeatedly came up during focus groups as well, even though it was not explicitly asked for.

En el salón de alemán tú te pones nervioso porque… hay muchas personas, entonces te pones más nervioso. [In the German classroom, you get nervous because… there are many people, thus you get more nervous.] (Lorena, focus group)

A mí me parece más relajado con Laila [her tandem partner]…es más personal, es sólo entre dos personas, en cambio en clase eres tú y diecisiete personas más. [To me it seems more relaxed with Laila [her tandem partner]… it's more personal, it's only between two people, in contrast in class there is you and seventeen others.] (Diana, focus group)

The fact that many learners fear being listened to while speaking a foreign language was also observed by Hilleson (1996) in his xxxxxxxxx I want to talk with them, but I don't want them to hear. Similarly, Liu and Jackson (2008) found that "most of the students were willing to participate in interpersonal conversations, but many of them did not like to risk using/speaking English in class" (p. 71). Findings of the present study align with these results, indicating that learners indeed do want to speak, but apart from their discomfort when being listened to, they also sensed that their lack of vocabulary inhibited them from speaking (more) in class, making them feel unable to express their thoughts and opinions:

Me siento no completamente bien por la falta de vocabulario. [I feel not completely good because of the lack in vocabulary.] (Sofia, interview)

Es un poquito estresante, porque uno se siente a veces impotente en cuanto al vocabulario, de no tener las palabras para poder expresar realmente lo que quiere decir. [It's a bit stressful, because one sometimes feels incapable with respect to vocabulary, not having the words to express what one really wants to say.] (Marcela, interview)

Both observations correspond with Liu and Jackson's (2008) findings of a significant correlation between students' unwillingness to communicate and their self-rated English proficiency. Another student, Lorena, apart from also feeling nervous, expressed a sensation of (self-)fulfilment when speaking German in class:

A parte de lo nerviosa, también me siento realizada, como un poco de autorrealización… se siente chévere cuando tú logras esa fluidez, tú te sientes como ‚wow, acabo de hablar alemán!'. [Apart from the nervousness, I also feel realised, like a bit of self-fulfilment…it feels awesome when you reach that fluidity, you feel like 'wow, I've just spoken German!'.] (Lorena, interview)

Overall, most learners perceived some kind of anxiety when it comes to speaking German in class. However, they also observed that these feelings of nervousness lessen over time and indicated that it felt good when they managed to successfully express themselves during class.

(3) Reducing Anxiety: "Hablar en tandem es diferente a hablar en clase…"

To investigate the anxiety-reducing potential of eTandem Language Learning, participants were asked about their experiences with eTLL in general, about the difference between speaking in class and speaking in tandem, and about how they feel when talking to their eTandem partners.

As to the first question, experiences were positive for all students participating in the interviews and focus groups. Without being asked for emotional aspects, David described how eTLL helped him losing his fear of speaking:

Esa experiencia te ayuda mucho, te quitas ese miedo y empiezas a soltarte, y cuando digamos en clase tenemos que hablar entre nosotros o hablar en público incluso, ya es mucho más fluido, más suelto, porque de alguna manera tienes experiencia con alguien y ya las cosas empiezan a salir. [That experience helps you a lot, you get rid of that fear and start to break free, and when let's say in class we have to talk amongst ourselves or also talk in public, it's already a lot more fluid, more casual, because somehow you have this experience with someone and things begin to succeed.] (David, interview)

When it comes to the divergence between speaking in class and with their eTandem partners, participants perceived various kinds of differences. Several learners described the eTandem situation as more relaxing and free in comparison to their language classes. When alluding to greater freedom in eTandem contexts, students repeatedly referred to the choice of topics being less restricted than in class.

En clase es un proceso un poco más serio, entonces tienes que hablar de los temas que te limitan, en cambio en tándem puedes hablar de mil cosas. [In class it's a more serious process, thus you have to speak about topics that limit you, in contrast in tandem you can talk about thousands of things.] (Paula, interview)

With their partners they tend to speak about less academic, more personal topics of mutual interest. They feel less pressure when talking to their tandem partners, perceiving it as a conversation "among friends" which results in more confidence whilst speaking. This confidence was also reflected in notions about the eTandem situation allowing to commit errors or asking their partners about anything repeatedly, whereas in class some students feel like they are expected to already know many things.

Concerning their emotions when speaking with their eTandem partners, all participants-with exception of Luisa, who had only been in contact with her partner on a written basis-expressed positive feelings. Three students mentioned having had some difficulties in the beginning, but being at ease now. Tanya, for example, stated being nervous in the first place about not knowing who the other person was:

Al principio nerviosa por lo que es una persona nueva y uno no sabe cómo es, pero ya después uno es más tranquilo. [At the beginning nervous because it's a new person and one doesn't know how they are, but after that, one is calmer.] (Tanya, interview)

Paula mentioned difficulties due to her lack of German, as she had started participating in the eTandem exchange at the very beginning of her language instruction, however, she also stated feeling comfortable now:

Me siento bien, me siento cómoda; aparte que siento que cada conversación es un logro… al principio era muy difícil porqué yo apenas estaba empezando alemán. [I feel good, I feel comfortable; apart from feeling that each conversation is an achievement…at the beginning it was very difficult because I was just starting [to learn] German.] (Paula, interview)

Lorena, too, explained her initial feeling of intimidation as a result of her partners' better Spanish skills than her own perceived German skills. Similar to Paula, over time this feeling changed with improving language skills, and she now feels happy and content:

Al principio me sentí muy intimidada porque ella habla muy bien español…me sentí intimidada porque yo empecé con tándem en alemán dos, entonces no sabía mucho…ahora me siento, siento que progresaba porque ya podemos mantener más la conversación …siento que ha mejorado mucho el alemán, entonces me eTandem Language Learning and Foreign Language Anxiety siento feliz por eso, me siento contenta. [At the beginning, I felt very intimidated because she speaks Spanish very well…I felt intimidated because I started with the tandem in German two, thus I didn't know much…now I feel, I feel that I have progressed because we can already better maintain the conversation…I feel that my German has improved a lot, therefore I feel happy, I feel satisfied.] (Lorena, interview)

Two students, Tanya and Diana, further explained the reasons for their positive emotions when speaking in eTandem compared to speaking in class. While Tanya underlined her fear of committing errors,

En clase sí siento que es mucha presión que cualquier error que hago, no sé, es muy malo [In class I do feel that there is a lot of pressure that any error I make, I don't know, is very bad] (Tanya, interview),

Diana referred to the fact of being assessed in class:

En clase a veces hay mucho más presión porque te están calificando, en cambio en tándem es más relajado y entonces es más chévere. [In class, sometimes there is much more pressure because you are being assessed, in contrast in tandem it's more relaxed, thus it's more awesome.] (Diana, interview)

Findings from the focus groups reinforce these outcomes, indicating that a major reason for speaking in eTandem being different from speaking in class is the fact of not being evaluated by a teacher. Patricia and Luisa describe this difference with regards to the teacher-role:

A mí me pasaba que cuando voy a hablar con mi compañera, bien al principio sentía nervios, pero ya después va muy relajado, y pues llegué acá e iba a hablar y no podía. Entonces yo decía pero ¿cómo es posible que yo hablo mucho por Skype con mi compañera y llego acá y me lleno de terror y no puedo hablar? Entonces yo pensé que tal vez es porque el profesor me intimidaba, no porque fuera malo o algo así, sino porque como alumno le están midiendo a uno cada aspecto, entonces uno siente la presión y uno se asusta, pero…hablando con mi compañera, supremamente relajada. [To me it happened that when I'm going to speak with my partner, well at the beginning I felt nervous, but then it went more relaxed, and well I got here and was about to speak and I couldn't. Thus I said but how is it possible that I speak a lot via Skype with my partner and I get here and strike myself with awe and cannot speak? So, I thought that maybe it's because the teacher intimidated me, not because he was bad or anything like that, but because as a student you are always measured in any way, thus one feels the pressure and gets frightened, but…speaking with my partner, supremely relaxed.] (Patricia, focus group)

Otra cosa que yo creería que afecta mucho es la manera que hemos crecido nosotros acá en el pais, porque desde pequeño nos enseñan pues el profesor es grande, es él que sabe, es el jefe. [Another thing that I would say affects a lot is the way in which we have grown up here in the country, because from childhood on they teach us that the teacher is grand, is the one who knows, is the boss.] (Luisa, focus group)

Sí quita mucha el miedo para hablar…quita el miedo de hablar, pero no quita el miedo del profesor. [Yes it does eliminate the fear of speaking…it eliminates the fear of speaking, but it does not eliminate the fear of the teacher.] (Patricia, focus group)

This suggests that eTLL may actually reduce the fear of using the foreign language and speaking to German natives, but that this newly gained confidence in eTandem does not necessarily transfer to institutional contexts where learners are still being evaluated. Another source of discomfort in class is corrective feedback. As de Dios Martínez Agudo (2013) describes in his xxxxxxxxx, although learners are aware of their learning process and most of them appreciate oral corrective feedback, some students feel embarrassed when corrected by their teachers. In contrast, corrective feedback from their tandem partners is generally perceived less oppressive and thus more helpful. Marcela explains her uneasiness with being corrected in relation to before mentioned assessment:

En comparación con el tándem el problema en la universidad son las notas. Como decía Luisa, uno acá sabe que si se equivoca, perdió la materia o, no sé, perdió un semestre. En cambio en tándem uno tiene la libertad…de corregirlos… para dejar que te corrigen sin que a alguien, como decía Patricia, lo midan. [In comparison with the tandem, the problem at the university are the marks. As Luisa said, here, one knows that if you make a mistake, you fail a subject or, I don't know, lose a semester. In contrast in tandem, one has the freedom…to make corrections… to let them correct you without, as Patricia said, being measured.] (Marcela, focus group)

Other students, in turn, acknowledged that the experiences made in eTandems helped them to reduce their fear of speaking in class, for example Sofia:

La experiencia tándem ayuda uno a eso, a saber que uno tiene que hablar, que es necesario hablar para poder aprender un idioma, y sí le quita mucho el miedo de hablar con alguien, de hablar en clase, por ejemplo. Hablar en clase es más fácil si uno habla con el tándem. The tandem experience helps a lot with that, to know that one has to speak, that it's necessary to speak in order to learn a language, and yes it eliminates the fear of speaking with someone, of speaking in class, for example. Speaking in class is easier if one speaks with the tandem.] (Sofia, focus group)

Carolina, the most anxious participant in this study, referred to better learning outcomes due to reduced pressure in tandem compared to the classroom context:

Yo diría que sí es un poco más relajado, porque uno cuando habla con el tándem, no es algo súper específico, sino que uno habla más como con un amigo, y entonces él te corrige de una manera… como un amigo, que te dice las cosas, pero normal, no te sientes tan presionada de decir las cosas bien o decirlas mal, y por eso aprendes. [I would say that yes it is a bit more relaxed, because when one speaks with the tandem [partner], it's nothing super specific, but one speaks rather like with a friend, so he corrects you in a way…like a friend, who tells you the things, but normally, you don't feel so pressured to say the things accurately or say them poorly, and that's how you learn.] (Carolina, focus group)

Several learners agreed during the focus groups with having felt "intimidated" in the beginning. Participants confirmed that this reaction was, on the one hand, due to the general situation of talking to a stranger over the Internet and was mainly perceived as part of the regular process of getting to know a new person. On the other hand, some students had had the notion that their partners' Spanish proficiency exceeded their own German skills, which made them feel insecure at first.

To sum up, findings clearly indicate that eTandem Language Learning may contribute to reducing the fear of using German, and also partly of committing errors. Participants attributed these effects to the non-formal nature of eTandems which usually results in a more relaxing atmosphere for learning. As language anxiety is suggested to be significantly correlated to the learners' access to the target language (Liu & Jackson, 2008), the simple fact of increased exposure to German may play an important role, too. However, it does not seem to reduce test anxiety or fear of negative evaluation. Participants explicitly distinguish between the two contexts, formal learning at the university and non-formal learning with their eTandem partners. Although describing the communicative situation in eTandems as open, relaxing, with low pressure, and thus reducing their fears and raising their confidence when speaking, these effects may not completely be transferred to in-class language learning.

Conclusion

This paper reported on a small-scale qualitative investigation exploring the experiences of Colombian students of German as a foreign language who participated in an eTandem Language Learning eTandem Language Learning and Foreign Language Anxiety project. The aim of the study was to examine how eTLL could contribute to reducing foreign language anxiety. The results suggest that eTandems have great potential for reducing the fear of speaking German and talking to "real" speakers of the foreign language. At the same time with becoming more familiar with both the language as well as their eTandem partners, the learners' confidence while using the language increases. These findings align with Appel and Gilabert (2002). Various aspects of eTLL contributed to this development: exposure to the target language which goes hand in hand with language practice, the one-to-one communication situation, the casual atmosphere in general, the personal dimension allowing for exchanges based on the participants' mutual interests, and the lack of a teacher and therefore the lack of evaluation.

It seems, however, that this fear-reduction does not always apply to classroom settings, especially the fear of negative evaluation appears to be a rather persistent phenomenon among the participants. Although some learners stated that the eTandem experience had helped them feel more confident when speaking German in class, other participants observed that even though they feel confident when speaking with their tandem partners, they still get nervous in class. The main reasons for this may be found in the nature of formal institutional language learning, where evaluation through a teacher is an essential part of instruction. Being assessed still causes feelings of anxiety and nervousness among some learners. It may thus be said that among the participants in our case study, eTandem Language Learning successfully contributed to reducing communication apprehension, whereas fear of negative evaluation remained consistent for at least part of the students.

Findings indicate that this fear might be rooted in the traditional teacher role, which, according to the participants, is prevalent in Colombia. Even though students reported on the agreeable atmosphere in their German classes as well as on generally good relations among teachers and students, they may feel rated in any situation they are supposed to speak in class.

Another reason why communication apprehension persists in classroom contexts lies in a more general fear of speaking in front of others. This anxiety is not necessarily language related and may appear in any class or even in other contexts when one is supposed to talk in public.

At large, perceived impacts of eTandem Language Learning on foreign language anxiety among our participants in Colombia may be regarded as positive. Although these effects are not always transferable into the classroom, a certain degree of anxiety reduction was perceived by all participants. As results also suggest that a certain time is needed in order to get accustomed to the communication situation in eTandem, such exchanges ideally accompany students throughout their whole language learning career. In this way, as familiarity and confidence increase over time, extended positive effects on language anxiety might be observed later on. Until now, most eTandem exchanges in universities have been organized within the framework of short-term projects, often as extra-curricular activities and on the basis of teachers' voluntary engagement. One challenge for the future will thus be the integration of eTLL into institutional language learning, moving this approach "from the periphery to the core of foreign language education" (O'Dowd, 2011, p. 368). Yet, this would necessitate an integration into the syllabi of the respective institutions-a challenge that is out of the teachers' hands.

As to the transferability of anxiety-reduction into the classroom, the "old" challenge of creating supportive learning environments in which learners feel secure to speak and make mistakes without fear seems to remain one of the top issues within language teaching research and language pedagogy. As in (e)Tandem exchanges, open activities with personal dimensions that are related to the learners' everyday lives may provide valuable contributions to this field. However, as long as learners are evaluated, and teachers and evaluators are represented by the same person, even the most supportive learning environment reaches its limits.

References

Appel, M. C. (1999). Tandem language learning by e-mail: Some basic principles and a case study. CLCS Occasional Paper No. 54. Dublin: Trinity College.

Appel, C., & Gilabert, R. (2002). Motivation and task performance in a task-based web-based tandem project. ReCALL, 14(1), 16-31. doi: 10.1017/S0958344002000319.

Appel, C., & Mullen, T. (2000). Pedagogical considerations for a web-based tandem language learning environment. Computers and Education, 34, 291- 308. doi:10.1016/S0360-1315(99)00051-2.

El-Hariri, Y., & Jung, N. (2015). Distanzen überwinden: Über das Potenzial audio-visueller e-Tandems für den Deutschunterricht von Erwachsenen in Kolumbien. Zeitschrift für interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 20(1), 106-139. Retrieved from: http://tujournals.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/index.php/zif/view/194/187.

El-Hariri, Y., Jung, N., & Angulo, A. (2016) Distanzen überwunden? Eine Evaluation von e-Tandemerfahrungen Deutschlernender in Kolumbien. Zeitschrift für interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 21(1), 176-208. Retrieved from: http://tujournals.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/index.php/zif/view/802/803

El-Hariri, Y., Jung, N., & Angulo, A. (2016) Distanzen überwunden? Eine Evaluation von e-Tandemerfahrungen Deutschlernender in Kolumbien. Zeitschrift für interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 21(1), 176-208. Retrieved from: http://tujournals.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/index.php

Bower, J., & Kawaguchi, S. (2011). Negotiation of meaning and corrective feedback in Japanese/English eTandem. Language Learning & Technology, 15(1), 41-71. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/issues/february2011/bowerkawaguchi.pdf

Brammerts, H. (2005). Autonomes Fremdsprachenlernen im Tandem: Entwicklung eines Konzepts. In H. Brammerts, & K. Kleppin (Eds.), Selbstgesteuertes Sprachenlernen im Tandem. Ein Handbuch (pp. 9-16), Tübingen: Narr.

British Council. (2015). English in Colombia: An examination of policy, perceptions and influencing factors. Retrieved from https://ei.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/latin-america-research/English%20in%20Colombia.pdf

Bueno-Alastuey, M. C. (2013). Interactional feedback in synchronous voice-based computer mediated communication: Effect of dyad. System, 4(3), 543- 559. doi:10.1016/j.system.2013.05.005

Clavijo Olarte, A., Hine N. A., & Quintero L. M. (2008). The virtual forum as an alternative way to enhance foreign language learning. Profile, 9, 219-236. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S1657-07902008000100013&script=sci_arttext

Cziko, G. A. (2004). Electronic tandem language learning (eTandem): A third approach to second language learning for the 21st century. CALICO Journal, 22(1), 25-39. Retrieved from https://calico.org/html

De Dios Martínez Agudo, J. (2013). An investigation into how EFL learners emotionally respond to teachers' oral corrective feedback. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(2), 265-278. Retrieved from http://revistas.udistrital.edu.co/ojs/index.php/calj/

Dresing, T., Pehl, T., & Schmieder, C. (2015). Manual (on) transcription: Transcription conventions, software guides and practical hints for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Marburg. Retrieved from http://www.audiotranskription.de/english/transcriptionpracticalguide.htm

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language acquisition: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Gardner, R. C., & MacIntyre, P. (1992). A student's contribution to second language learning. Part I: Cognitive variables. Language Teaching, 25, 211-220.

Goethe Institut. (2014). Ergebnis der gemeinsamen DaFUmfrage Kolumbien von DAAD, Goethe-Institut, kolumbianischem Deutschlehrerverband APAC und deutscher Botschaft Bogotá von 10-12/2013. Retrieved from http://www.goethe.de/resources/files/pdf16/Deutsch_in_Kolumbien_2014-041.pdf

Gogolin, I., & Neumann, U. (1991). Sprachliches Handeln in der Grundschule. Die Grundschulzeitschrift, 43, 6-13.

Hampel, R. (2006). Rethinking task design for the digital age: A framework for language teaching and learning in a synchronous online environment. ReCALL, 18(1), 105-121. doi:10.1017/S0958344006000711.

Hilleson, M. (1996). I want to talk with them, but I don't want them to hear: An introspective study of second langue anxiety in an English-medium school. In K. M. Bailey & D. Nunan (Eds.), Voices from the language classroom (pp. 248-282). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.i

Hoffmann-Riem, C. (1984). Das adoptierte Kind. Familienleben mit doppelter Elternschaft. München: Wilhelm-Fink-Verlag.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/327317

Jin, L., & Erben, T. (2007). Intercultural learning via instant messenger interaction. CALICO Journal, 24(2), 291-311. Retrieved from https://www.calico.org/html

Kötter, M. (2002). Tandem learning on the internet: Learner interactions in virtual online environment (MOOs). Frankfurt/Main: Lang.

Krumm, H.-J., & Jenkins, E.-M. (2001). Kinder und ihre Sprachen - lebendige Mehrsprachigkeit. Wien: Eviva

Lee, L. (2004). Learners' perspectives on networked collaborative interaction with native speakers of Spanish in the US. Language Learning & Technology, 8(1), 83-100. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol8num1/pdf/lee.pdf

Little, D., Ushioda, E., Appel, M. C., Moran, J., O'Rourke, B., & Schwienhorst, K. (1999). Evaluating tandem language learning by e-mail: Report on a bilateral project. CLCS Occasional Paper No. 55. Dublin: Trinity College.

Liu, H. (2012). Understanding EFL undergraduate anxiety in relation to motivation, autonomy and language proficiency. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 9(1), 123-139. Retrieved from http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/v9n12012/liu.pdf

Liu, H., & Chen, C. (2015). A comparative study of foreign language anxiety and motivation of academic- and vocational-track high school students. English Language Teaching, 8(3), 193-204. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1075211.pdf

Liu, M., & Huang, W. (2011). An exploration of foreign language anxiety and English learning motivation. Education Research International. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2011/493167

Liu, M., & Jackson, J. (2008). An exploration of Chinese EFL learners' unwillingness to communicate and foreign language anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 92(1), 71-86. doi:10.5430/elr.v2n1p1

Lu, Z., & Liu, M. (2011). Foreign language anxiety and strategy use: A study with Chinese undergraduate EFL learners. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 2(6), 1298-1305. doi: 10.4304/jltr.2.6.1298-1305

MacIntyre, P., & Gardner, R. C. (1994). The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language. Language Learning, 44(2), 283-305. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01103.x

MacIntyre, P., & Gregersen, T. (2012). Affect: The role of language anxiety and other emotions in language learning. In D. Mercer, S. Ryan, & M. Williams (Eds.), Psychology for language learning: Insights from research, theory & practice (pp. 103-118). London: Palgrave.

Mayring, P. (2008). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. 10. Aufl., Weinheim, Basel: Beltz.

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt. Free download pdf-version: http://www.psychopen.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/books/mayring/ssoar-2014-mayring-Qualitative_content_analysis_theoretical_foundation.pdf

O'Dowd, R. (2011). Online foreign language interaction: Moving from the periphery to the core of language education. Language Teaching, 44(3), 368-380. doi: 10.1017/S0261444810000194

O'Dowd, R., & Ware, P. (2009). Critical issues in telecollaborative task design. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 22(2), 173-188. doi:10.1080/09588220902778369

Ohata, K. (2005). Potential sources of anxiety for Japanese learners of English: Preliminary case interviews with five Japanese college students in the U.S. TESL-EJ, 9(3). Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.org/pdf/ej35/a3.pdf

O'Rourke, B. (2005). Form-focused interaction in online tandem learning. CALICO Journal, 22(3), 433-466. Retrieved from https://calico.org/html

O'Rourke, B. (2007). Models of telecollaboration (1): eTandem. In R. O'Dowd (Ed.), Online intercultural exchange: An introduction for foreign language teachers (pp. 41-61). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Pérez-Paredes P. F., & Martínez-Sánchez, F. (2000- 2001). A Spanish version of the foreign language classroom anxiety scale: Revisiting Aida's factor analysis. RESLA, 14, 337-352. Retrieved from http://www.ehu.eus/ojs/index.php/psicodidactica/download/1162/4028

Sotillo, S. (2005). Corrective feedback via instant messenger learning activities in NS-NNS and NNSNNS dyads. CALICO Journal, 22(3), 467-496. Retrieved from https://calico.org/html

Tian, J., & Wang, Y. (2010). Taking language learning outside the classroom: Learners' perspectives of eTandem learning via Skype. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 4(3), 181-197. doi:10.1080 /17501229.2010.513443

Ushioda, E. (2000). Tandem language learning via e-mail: From motivation to autonomy. ReCALL, 12, 121- 128. doi: 10.1017/S0958344000000124

Vassallo, M. L., & Telles, J. (2006). Foreign language learning in-tandem: Theoretical principles and research perspectives. The ESPecialist, 27(1), 83-118. Retrieved from http://www.corpuslg.org/ journals/the_especialist/issues/27_1_2006/artigo5_Vassalo&Telles.pdf

Wang, Y. (2007). Task design in videoconferencingsupported distance language learning. CALICO Journal, 24(3), 591-630. Retrieved from https://www.calico.org/html

Wang, Y., & Chen, N. (2012). The collaborative language learning attributes of cyber face-toface interaction: The perspectives of the learner. Interactive Learning Environments, 20(4), 311-330. doi:10.1080/10494821003769081

Ware, P., & O'Dowd, R. (2008). Peer feedback on language form in telecollaboration. Language Learning & Technology, 12(1), 43-63. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol12num1/pdf/wareodowd.pdf

Yan, J. X., & Horwitz, E. K. (2008). Learners' perceptions of how anxiety interacts with personal and instructional factors to influence their achievement in English: A qualitative analysis of EFL learners in China. Language Learning, 58(1), 151-183. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00437.x

Yilmaz, Y., & Granena, G. (2010). The effects of task type in synchronous computer-mediated communication. ReCALL, 22(1), 20-38. doi:10.1017/ S0958344009990176

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.

.JPG)