DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.13008Published:

2018-07-31Issue:

Vol 20, No. 2 (2018) July-DecemberSection:

Research ArticlesCollaborative inquiry in the EFL classroom: exploring a school related topic with fifth graders

Investigación colaborativa en el aula de inglés: explorando un tema relacionado con la escuela con niños de quinto grado

Keywords:

indagación colaborativa, pedagogía basada en la comunidad, convivencia, aula de lenguas (es).Keywords:

Collaborative Inquiry, CBP, coexistence, EFL classroom (en).Downloads

References

Bello, I. (2011). Analyzing discourses as citizen in the EFL Classroom. Bogotá Colombia: Universidad Distrital Francisco Josë de Caldas. School of Science and Education. Master Program in Applied Linguistics to TEFL.

Berns, J., & Fitzduff, M. (2007). Complementary approaches to coexistence work: What is coexistence and why a complementary approach? Waltham, MA: Brandeis University.

Burns, A. (1999). Observational techniques for collecting action research data in collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cabra, I., Gonzalez, E., & Gomez, D. (2014). Formacion de cudadanos. Bogota: Publisher.

Chaux, E., Nieto, A., & Ramos, C. (2007). Aulas en paz: A multicomponent program for the promotion of peaceful relationships and citizenship competencies. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 25(1), 79-86. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.193

Clavijo, A (2014). Implementing community based pedagogies with teachers in Colombia. Conference LESLLA. Nijmegen, Netherlands

Clavijo, A. (2014) Implementing community based pedagogies with teachers in Colombia to enhance the EFL curriculum. Memorias del X Foro de Lenguas Internacional. Universidad de Quintana Roo. October, 2014.

Clavijo, A., & Sharkey, J. (2011). Community-based pedagogies projects and possiblities in Colombia and the United States. In A. Honigsfeld & A. Cohan (Eds.), Breaking the mold of education for culturally and linguistically diverse students (pp. 9-13). Medellín: R & L Education.

Dewey, J. (1997). Experience and education. New York, NY: Touchstone.

Douville, P., & Wood, K. D. (2001). Collaborative learning strategies in diverse classrooms. In V. J. Risko & K. Bromley (Eds.), Collaboration for diverse learners: Viewpoints and practices (123–151). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

García, O. (2009). Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st century: Social justice through multilingual education. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

García, O. (2011a). Chapter title. In T. K. Bhatia & W. C. Ritchie (Eds.), The handbook of bilingualism and multilingualism (2nd ed., pp. 5–25). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

García, O., & Wei, L (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. New York, NY: St Martin’s Press LLC. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137385765

Johnston, R., & Davis, R. (2008). Negotiating the dilemmas of community‐based learning in teacher education, Teaching Education, 19(4), 351-360. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210802436492

Kretzman, J., & Mcknight, J. (1993). Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets. Location: The asset-based community development institute for policy research northwestern university.

Lee, C., & Smagorinsky, P. (2000). Vygotskian perspectives on literacy research: Constructing meaning through collaborative inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Medina, R., Ramírez, M., & Clavijo, A. (2015). Reading the community critically in the digital age: A multiliteracies approach in Reading the community critically in the digital age: a multiliteracies approach. In P. Chamness Miller., M. Mantero. & H. Hendo (Eds), ISLS Readings in Language Studies (vol. 5; pp.45-66). Location: Publisher.

Mendieta, J. A. (2009). Inquiry as an opportunity to make things differently in the language classroom. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 11, 124-135.

Meyer, H. (2008). The pedagogical implications of L1 use in the L2 classroom. Maebashi Kyoai Gakuen College Ronsyu. 8, 147-159.

Ministerio de Educación de Colombia (MEN). (2003). Formar para la ciudadanía. sí es posible. Estándares Básicos de Competencias Ciudadanas. Lo que necesitamos saber y saber hacer.

Ministerio de Educación de Colombia (MEN). (2006). Estándares Básicos de Competencias en Lenguas Extranjeras: Inglés Ministerio de Educación Nacional República de Colombia Formar en lenguas extranjeras: ¡el reto! Lo que necesitamos saber y saber hacer.

Mockus, A. (2004). ¿Por qué competencias ciudadanas en Colombia? Apuntes para ampliar el contexto de la discusión sobre estándares y pruebas, que en competencias ciudadanas ha empezado a construir y aplicar el Ministerio de Educación. AlTablero, http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-87299.html.

Morahan, M. (2007). The use of students’ first language (L1) in the second language (L2) classroom. Retrieved from: www.laschool.pd/edu/PD_Mini_modules/images/8/81/MorahamL1inL2class.pdf.

Sharkey, J., Clavijo, A., & Ramirez, M. (2016). Developing a deeper understanding of community-based pedagogies with teachers: Learning with and from teachers in Colombia. Journal of Teacher Education 67(3), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116654005

Short, K., & Burke, C. (1991). Creating curriculum: Teachers and students as community learners. USA: Library of the Congress.

Short, K. G., & Burke, C. (2001). Curriculum as inquiry. In S. Cakmak & B. Comber (Eds.), Critiquing whole language and classroom inquiry (pp. 18-41). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Short, K., et al. (1996). Learning together through Inquiry: From Columbus to integrated curriculum. USA: Library of the Congress.

Short, K., Harste, H., & Burke, C. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Strauss, J., & Corbin, A. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Location: Sage Publications, Inc.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language. (A. Kozulin, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Wells, G. (2000). Dialogic inquiry in education: Building on the legacy of Vygotsky in Vygotskian perspectives on literacy research. New York, NY: Cambridge University press.

Wright, W. E., Boun, S., & García, O. (Eds.). (2015). The handbook of bilingual and multilingual education. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118533406

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 8 de febrero de 2018; Aceptado: 9 de julio de 2018

Resumen

La presente investigación acción involucra un proceso de aprendizaje basado en indagación, en el que los estudiantes de grado quinto de un colegio público en Bogotá, trabajaron de forma colaborativa en la exploración de un tema propio de su comunidad (el refrigerio escolar). La indagación colaborativa realizada por los estudiantes permitió promover reflexiones en el aula de inglés, lo que está en concordancia con las ideas de Vygotsky acerca del aprendizaje mediado por el contexto social y material (Lee & Smagornsky, 2000). El currículo, aparece como recurso relevante para el aprendizaje de lenguas (Sharkey, Clavijo, & Ramirez, 2016), éste fue construido alrededor de la realidad y la comunidad de los estudiantes y por los estudiantes. Las sesiones de clase fueron organizadas y planeadas a partir del conocimiento que los estudiantes tenían e iban generando a partir del refrigerio escolar. En este sentido, Dewey (1997) propone el aprendizaje como una experiencia en la que los niños en este caso participaron de la creación de un currículo basado en su comunidad y utilizaron la indagación como método para conocer más a fondo de la misma. Lo hallazgos sugieren que a través de proyecto de clase, los estudiantes de Quinto grado desarrollaron habilidades de indagación y literacidades de tipo digital, visual, oral y escrita, mientras aprendían juntos de una manera colaborativa. El proceso de indagación en el aula de lenguas evidencia el uso del español e inglés como vehículos del aprendizaje de un tema significativo que va más allá de las tradicionales lecciones de gramática. Dicho trabajo colaborativo, también permitió que los estudiantes realizarán reflexiones sobre los retos de trabajar juntos de forma colaborativa, sobre la convivencia escolar al enfrentar dichos retos y sobre el aprendizaje mismo de la lengua extranjera.

Palabras clave:

indagación colaborativa, pedagogía basada en la comunidad, convivencia, aula de lenguas.Abstract

This action research study reports an inquiry based learning process in which fifth graders worked collaboratively by examining a local topic (free school snack) from their school context. Collaborative inquiry was used as a way to promote elementary students’ reflections in the EFL classroom drawing on Vygotsky’s ideas about learning mediated by social and material contexts (Lee & Smagorinsky, 2000). The EFL curriculum was organized around students’ communities and realities as relevant resources for language learning (Sharkey, Clavijo & Ramirez, 2016). Lessons were organized around students’ knowledge about the free daily snack that school provides to all children and what they wanted to learn about the topic. In this sense, Dewey’s (1997) idea of learning as experience was implemented through an inquiry curriculum with students. Findings suggest that through a classroom project, fifth graders developed inquiry skills and digital, visual, oral, and written literacies while learning together through collaboration. Inquiring in the language classroom evidenced the use of languages (Spanish and English) as the means to learn about meaningful content beyond English grammar lessons. It also led to individual reflections about the challenges of working together as well as about school coexistence understood as the way all the members of an educational community relate to each other.

Keywords:

Collaborative Inquiry, CBP, coexistence, EFL classroom.Introduction

The current article presents an action research study conducted in a public school in Bogotá. The research used inquiry based learning in the EFL classroom aimed to promote reflections among students about the ways in which they coexisted inside the classroom while they were learning about different issues with a transdisciplinary view of education. The different sections in the article present the theoretical foundations, the context, the participants, the data collection instruments, the research method, the pedagogical intervention, the data organization and analysis and the findings.

The problematic situation tackled in this research was related to the pedagogical practices in English language teaching and in the other content area classes that seemed not to promote reflection among students. In other words, this study addressed a pedagogical proposal that guided students’ reflections regarding the way they related to each other and built a peaceful coexistence while learning language. The goal of this study was to lead fifth grade students into a collaborative inquiry so that they could reflect upon the way they related to each other during collaborative work and wrote reflective paragraphs in English.

Theoretical Considerations

The main constructs that theoretically support this research are presented in the sections below. In the first part, I present Community Based Pedagogy as the framework in which all the pedagogical implementation is supported. Next, the concepts of coexistence and collaborative inquiry are exposed. Finally, the concept of translanguaging helps explain students’ language productions resulting from their collaborative inquiries in which English and Spanish are both used to make meaning.

Community Based Pedagogies

Acknowledging the surrounding context implies that the teacher and the students take into consideration the community as a source for knowledge. In that sense, the inclusion of the community as part of teaching practices to enrich curriculum and promote understanding as a key aspect in the learning process is called Community Based Pedagogies (CBP). Medina, Ramirez, and Clavijo (2015) proposed CBP as an approach to critically read the community in which looking into the problematic situations of the community and proposing alternatives for transformation are the two big perspectives to be addressed. CBP proposes that teachers and learners take advantage of the community by doing and inquiring in order to establish connections between the curriculum and the sources available in the surroundings. Clavijo (2014) argues that CBP is a set of practices that permeate the curriculum, giving understandings about the communities in which the school and the students are embedded. The sources taken from the local context, in this case the community, are starting points for teaching and learning that enrich the language curriculum (Clavijo & Sharkey, 2011). Thus, Johnston and Davis’ (2008) ideas about the community as source for learning give strong support to this idea. In this way, they suggest that “students learn best when learning connects strongly with communities and practice beyond the classroom [by interacting with] local and boarder communities and community practices” (p. 353). This implies that learning becomes more meaningful when the community makes part of what is being learned.

As suggested by Kretzman and McKnight (1993), “there are different ways to approach the knowledge the community can provide, each community brings a unique combination of assets” (p. 4) In that search for resources connected to the curriculum, it is important to understand that places can be sources for learning (Somerville, 2010). There is a strong relationship between the place and its stories as well as between people and the place, which implies that there are numerous entities to learn from and discover about the places within a community. The great value of CBP as an approach to bringing students’ worlds into the language classroom recalls the ideas of Dewey (1997) regarding inquiry in the curriculum, in which the curriculum is seen as “based upon a philosophy of experience” (p. 27)-a curriculum that empowers students and teachers. Language teaching implies the acknowledgement of the social aspect of language learning which directly connects to coexistence, the following construct, which is a very important issue in the language classroom. The way students coexist and the experiences they have about it can bring sources for the language classroom.

Coexistence

The concept of coexistence is understood as the way people relate to each other and understand conflict as part of their daily life. This notion is emphasized within the perspectives of citizenship competences proposed by the Colombian Ministry of Education that intend to form citizens in peaceful environments. This issue has been approached from different perspectives since citizenship itself has different ways of being comprehended. Mockus (2004) proposes that citizenship is the way that people (children in this case) are an active part of the society, being aware of the others as part of the surrounding world. That is, the way a person, related to the state and to the members of the society, emphasizes good relations with others based on principles such as respect, confidence, solidarity, autonomy, and diversity.

The term is broadly defined in conflictive settings and supposes the acknowledgement of others and their differences. Berns and Fitzduff (2007) state that “coexistence describes societies in which diversity is embraced for its positive potential, equality is actively pursued, interdependence between different groups is recognized, and the use of weapons to address conflicts is increasingly obsolete” (p. 2). In pursuance of expanding the concept of coexistence in educational settings, I mention below some research studies that have addressed it. The first local study was developed at the school where I work by Cabra, Gonzalez, and Gomez (2014) and related to developing citizenship competences with children at school. This study is based on the behavior children are expected to have in different contexts inside and outside the school. The study mentioned above had two main stages: in the first, students are taught through workshops and games, the different behaviors a ‘good’ citizen is supposed to have. The second stage intends to place students in different contexts (parks, theatres stadium, among others) and to see how they have learned to behave. This study is important to the current research in the sense that it focuses on developing citizenship competences as a fundamental part of children’s education. It also provides reasons to say that it is not enough to work with the behaviors children are supposed to have when being in a certain place, but it is also necessary to reflect about the specific citizenship competences to enhance their leaning processes.

Another study was carried out by Bello (2011) at the university level that intended to analyze the discourses related to citizenship that emerged among students throughout a process of critical reflection in the EFL classroom. The study shows the way university students understood their role as citizens in society and the importance of decision making. Likewise, Chaux, Nieto, and Ramos (2007), as well as Chaux and Velasquez (2005), have carried out studies in Colombia related to citizenship competences. The studies mentioned above are a compilation of different experiences around the country in which the development of citizenship competences become an important aspect in the integral education of individuals.

Collaborative Inquiry

Inquiry based learning is a way to engage students in meaningful learning in the EFL classroom by taking language learning beyond linguistic structures via classes focused on personal and social knowledge. Collaborative inquiry implies the recognition and adoption of Vygotskyan ideas related to cognition in which knowledge is constructed and displayed by social and material contexts (Lee & Smagorinsky, 2000). In collaborative inquiry, learning is mediated between a person and others and their cultural artifacts through interactions. It involves the understanding of the social context as knowledgeable and learning as the result of the interactions within the learning process (Lee & Smagorinsky, 2000). It also intends to challenge students by posing questions based on reality so that they may focus their attention on answering those questions by doing inquiry. Thus, learning occurs “because the making requires the student to extend his/her understanding in action” (Wells, 2000, p. 64).

The possibility of inquiry as a curricular practice encourages students to get involved, talk to each other, and gain strong understandings of the inquired issue. Collaboration and reflection become the means through which learning is produced. This perspective allows students to go beyond just gathering and reporting information. This is a conscious system in which students wonder while being engaged in informal interactions and conversations (Short & Burke, 2001). Following that path, Short et al. (1996) propose the authoring cycle as a flexible way to lead students through the inquiry process. Reading and writing become more meaningful because the cycle encourages students to think as scientists in order to acquire a new view of a topic or issue.

In this regard, different studies have been carried out about curriculum as inquiry. For example, Mendieta (2009) described the outcomes when implementing an inquiry-based approach in the EFL classroom. The study revealed the importance of collaboration when students inquired and shared from their own reality. Some relevant issues that were brought up in these studies that are connected to the present study were collaboration since the children were immersed in a collaborative culture of inquiry and the exposure students had to sources in both L1 and L2, which allowed them to develop an insightful inquiry process. These aspects helped the researcher to understand the role of inquiry as a collaborative activity that promotes learning beyond the language.

Perhaps the study that is closest to the current research is that of Pineda (2007) whose main purpose was to analyze students’ interactions while working in inquiry based learning activities. The findings of the study suggest that inquiry is a great opportunity to promote collaboration, group support, and conflict resolution. These results support my decision to address coexistence in EFL learning through classroom projects. Students were immersed in projects, as presented in the findings of this study, and had the opportunity to narrate and reflect upon different circumstances that they lived during the inquiry process.

Translanguaging

According to García (2009) , translanguaging is an approach to the understanding of language, bilingualism, and the education of bilinguals. It considers the language practices of bilinguals not as two autonomous language systems, but both languages as one linguistic repertoire with features that have been socially constructed. Language is not a simple system of structures that is independent of human actions with others. Consequently, language refers to simultaneous processes of the continuous becoming of selves and language practices.

The base of this concept comes from the acknowledgement of the L1 as a tool for L2 learning. Meyer (2008) states that the L1 provides scaffolding and lowers the affective filters students may have when learning a language. Scaffolding is one aspect to be taken into consideration when working in elementary schools with beginning levels in an EFL public setting with only one hour per week of instruction. In this respect, the process needs to be gradual, allowing students to understand and apprehend the differences of both languages (Morahan, 2007. A social perspective in language teaching implies the revision of the use of L1 as a very important aspect during the learning process. The L1 allows students to work within the zone of proximal development proposed by Vygotsky in the sense that they use the L1 “when doing pair work to construct solutions to linguistic tasks and evaluate written language” (Morahan, 2007, p. 1850).

The idea of using the L1 and L2 in the language classroom has been understood from different perspectives throughout the years. From the linguistic view, the use of both languages in learning settings was named code switching. Codeswitching implies that students substitute vocabulary from their L1; they “gradually phased out as students become more proficient in L2” (Cook, 2001, as cited in Meyer, 2008, p. 152). The understanding of the use of two languages (L1 and L2) in a language learning setting has evolved into a more social conscious perspective, such as that presented by García (2009) , when proposing the term translanguaging as an alternative to understand and approach the bilingual process of learners.

García and Wei (2014) also stress that the concept of translanguaging differs from the notions of bilingualism employed in the 20th century since translanguaging is the understanding of language practices that entail the different features previously acquired from different histories of individuals. It recognizes different discursive practices in which bilinguals engage to make sense of their bilingual world. This implies a creative process that is owned by people’s interactions.

In sum, the concepts presented above address a sociocultural perspective in which learning within the language classroom extends beyond the boundaries of the classroom and into to the community to look for sources that nurture the language curriculum. In this way, the classroom becomes a place to engage in inquiry and learn about content while using language. Such a sociocultural perspective allows the acknowledgement of the challenges in language learning and places translanguaging as a means of communication in which language is not content but the means to talk about content.

Methodology

This study followed an action research design as this is the most suitable to carry out classroom research in accordance with the inquiry process students followed. Action research “applies a systematic process of investigating practical issues or concerns which arise within a particular social context. This process is undertaken with a view to involve the collaboration of the participants in that context” (Burns, 1999, p. 31). The study implemented three cycles in which the students and the researcher planned, acted, observed, and reflected to make decisions about the process and the steps to implement in each subsequent cycle.

The Context

The research was carried out at Codema School-a public school located in the southwest of Bogotá, in the district of Kennedy. The school was founded in 2007 after being donated to the district by Codema (Cooperativa de Maestros). The school educates 2500 students daily, distributed in two shifts (morning and afternoon). There are three educational levels-elementary, basic, and high school in the academic modality. The institution’s educational project promotes the construction of critical thinkers, justice, and a tolerant society. In terms of English language classes, the students have three hours per week in basic and high school educational levels, while in elementary, first to fifth graders are taught one hour per week.

The Participants

A group of 36 fifth grade elementary students participated in the study including 17 girls and 19 boys. Their age ranged between 10 and 12 years old. As they are children, a consent form was sent to their parents with the purpose of obtaining their permission to gather their artifacts, their journals, and to take pictures and videos of the classes. The information collected was used for the purposes of the research study and the students’ names were kept confidential.

Cycle 1. Exploring a Daily Life Issue at School

During this cycle, the pedagogical activities focused on exploring a particular issue that was part of the students’ daily life at school, in this case the school snack. During the planning and acting stages of the cycle, different workshops were implemented to encourage students to focus their attention on particular aspects related to the observable features of the school snack such as content, messages in packages, and moments of socialization. The observation stage of the first cycle provided data to carry out four workshops on different topics such as content of the snack, vocabulary related to food, messages for consumers in the packages, and moments of socialization around the school snack. Reflections were made around language aspects needed to be taken into account for the next cycle and possible questions to guide students’ inquiry in the second cycle.

Cycle 2. Inquiry Process Based on the Exploratory Cycle

During this cycle, the planning stage concentrated on paying specific attention to the outcomes of the exploratory stage in favor of developing an inquiry process. Based on the question for inquiry selected in the exploratory cycle, students inquired collaboratively about the specific issues related to the snack to learn to do inquiry. The inquiry process implied searching for information, reading different sources, interviewing people to expand their views on the information collected, and presenting preliminary findings of their inquiries to the class.

Cycle 3. Sharing Inquiry Outcomes

During the last cycle, students carried out pedagogical activities that prepared them to write the report of the inquiry outcomes. The teaching activities focused on helping students outline, edit, draft, revise, and finally present a descriptive text to the teacher. The teacher provided feedback for a final revision to be sent to an editorial committee invited to select the best pieces to be published in the school newspaper. Each cycle allowed the researcher and the participants to reflect upon the process of inquiry they carried out. The participants kept reflective journals and they were expected to write a journal entry for homework after every class. The researcher’s reflections were also registered as field notes after each class for the purposes of evaluating if adjustments were to be made in the pedagogical part.

The Pedagogical Intervention

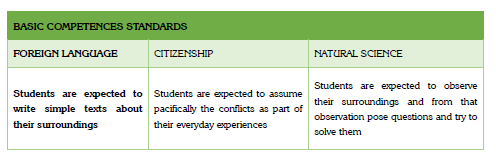

The pedagogical intervention followed an inquiry project related to a topic of students’ interest in the language classroom as well as the integration of Community Based Pedagogy to explore the community resources with students. To give support to the curricular activities proposed, some official documents were taken into account such as the basic standards and competences for fifth grade students for foreign language (MEN, 2006), natural science (MEN, 2006), and citizenship (MEN, 2003) stated by the Colombian Ministry of Education (see Appendix A). Thus, students’ collaborative inquiries were viewed as addressing issues that related to different content areas, in this case, science and citizenship competences.

The different phases were an adaptation from Short’s (1996) authoring cycle, as an inquiry based learning model to follow. During the three phases, students were asked to write reflections about what was happening within their groups. Those reflections were written in Spanish so that the children could easily express themselves. In this initial phase named Getting Together, they established the criteria for being part of a group, with the objective of achieving the different learning goals as a group.

The second stage, called Building from the Known, allowed students to explore their own context and to decide to inquire about the school snack as a very important aspect at school. Thus, they decided to seek more information about it through an inquiry project. The phase also implied building new vocabulary in English related to the food and the different elements related to the school snack.

The third phase was called Taking Time to Find Questions for Inquiry. In this stage, students shaped their inquiry and planned the process they would follow. In this phase, the different groups created their inquiry questions around the school snack. Those questions included: What is recycling?; What do we recycle for?; What is nutrition?; Is the school snack nutritious?; How does recycling help me?; How does recycling help the planet?; Where is the school snack made?; How is the process?; Is our school snack healthy?; How is the school snack transported in order to be eaten by us?; Which type of ingredients does the school snack have?; Why does the government give us school snack?; Which nutrients and vitamins can we find in the school snack?

The following phase, named Gaining New Perspectives, was the inquiry process development stage. This phase implied gathering the information needed to answer the inquiry questions and to acknowledge the different sources in which that information could be found. This was the longest stage given the importance of finding the right information to answer the proposed questions. The phase that followed was named Attending to the Difference. The objective was to organize the data and check if the questions could be answered with the given information or if there was a need to consult an additional or different source.

The final phase was called Sharing what was Learned. Students first presented their preliminary findings to their classmates, and then organized the information in a book in which they decided to share their learning about the inquiry questions posed, about working collaboratively, and about the process itself. They wrote their books in English after an editing process. Lastly, they decided to organize a launching of the books in the school library, to share their books with the whole community.

The pedagogical unit about the school snack allowed students to write texts in English and Spanish in which they talked about an inquiry process of a topic of their interest. This learning outcome represented an elaborated text about a topic from their reality, which surpasses what is proposed in the foreign language standards. On the contrary, they produced a complex text about their understanding of an issue from their context which was the result of their exploration from different perspectives in the inquiry groups. This also allowed them to learn how to follow the scientific method by observing, asking, looking for information, and answering. Likewise, children had the opportunity to reflect about being together in a classroom and the implications of working together with a common objective. They could understand that they are part of a society which is a contribution to their education as citizens.

Moreover, the data analysis and findings presented in the following section constitute the results of implementing this type of pedagogy that addressed the community as a source and language as the means to construct knowledge about language, culture, citizenship, science, as aspects that contribute to lifelong learning for EFL students.

Procedures for Data Organization and Analysis

Data were collected through field notes, students’ journals and artifacts. For the data analysis process, I used Atlas.ti, 6th edition, a computer program for qualitative analysis in which I focused on my students’ reflections and artifacts and my own field notes. Two categories emerged from the grouping of the coding networks in the previous phase. A third category emerged after having presented the preliminary results of the study to an academic audience, using evidences that showed students’ writing and speaking in Spanish and in English as the foreign language when reflecting about school coexistence and reporting about their classroom inquiry.

Findings

Three categories emerged from the data analysis that answered the research question focused on the type of reflections that were unveiled when children did their collaborative inquiry in the EFL classroom. These are: recognizing group work assets in collaborative inquiry, experiencing school coexistence though collaborative work, and translanguaging in the oral and written speech about coexistence. These are explained below

Recognizing Group Work Assets in Collaborative Inquiry

This first category deals with the characteristics of the collaborative inquiry that fifth graders recognized in their reflections during the process. Since inquiry is a great opportunity for learning, the reflections children completed in terms of the learning they were involved in during the process were a response to a type of curriculum that strengthens curiosity, intentionality, and sociability (Short & Burke 1991).

One of the areas of learning addressed by the students in their writings related to team work as an important part of the process, implying the understanding of collaboration in which “students [work] collaboratively in supporting each other’s learning and inquiry” (Short & Burke, 1991, p. 68). The sample below shows how working together was part of the results obtained. When working collaboratively, children as any collaborative group “expect… to succeed in every project or task” (Short & Burke, 1991, p. 25), which is stated by the child in his reflection when he says that everything was right, which was the main objective of team work for them (children’s texts are typed without corrections).

Pues nosotros Aprendimos que tubimos que trabajar en equpo para organizarnos y estar bien todos isimos nuestra parte y todo salió bien.

Data source 1 From Students’ Reflections on September 2nd 2015

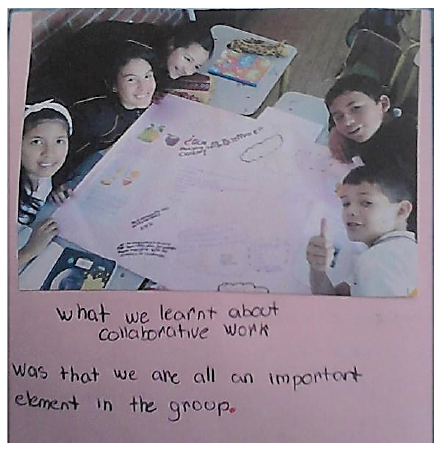

Collaborative inquiry also supposes the acknowledgment of the other as an important part of the group. This permitted students to understand that all work done by their colleagues was important and needed to be taken into consideration in the inquiry process. As presented by a group of inquirers in their books about the experience, they decided to paste a photo in which the entire group appeared and said that one important thing they learned within the process about collaborative inquiry was that everyone in the group counted. The learning implied the acknowledgment of all members as important elements in the group, which is a positive result in contributing to the peaceful coexistence in the classroom as seen in the figure below.

Collaborative inquiry promoted peaceful attitudes between students as it allowed them to acknowledge the others and their interventions as important. Listening to others became a relevant aspect to take into account when developing their activities during the inquiry process as learning took place, since perhaps they had not considered this issue before. Listening to our classmates, as seen in Figure 2, was a significant outcome in terms of the way they learn for life. This learning is applicable not only to the English classes, but also to all aspects in their lives when understanding the importance of listening to what the others had to say.

Figure 1: Data Source 2: From students’ Artifacts. Book about the experience.

Figure 2: Data Source 3: From students’ Artifacts. Book about the experience.

In general, this category addresses the first reflections that were unveiled in the students’ journals in which they approached collaborative inquiry by understanding the main aspects of working together. The assets they acknowledge in their reflections guided them to take into consideration the responsibilities they had during the process and the agreements that are needed to achieve the goals of the research process they were conducting. This category is strongly linked to Short et al.’s (1996) ideas about the role of collaboration in inquiry based learning as they state that collaboration stimulates students to consider new ideas and explain their thinking to others. It also takes them to build learning collaborative communities in which they acknowledged similarities and valued differences (Short et al., 1996).

Experiencing School Coexistence in Collaborative Work

The second category expresses the most relevant coexistence experiences fifth graders lived during the process. This category relates to the different aspects of collaborative inquiry that allowed them to understand and somehow transform their daily coexistence practices into more pacific and dialogic ones. The category reflects the positive effects of implementing an inquiry based model in which students were asked to reflect on the values they have experienced. Furthermore, Chaux, Nieto, and Ramos (2007) acknowledge that most of the pedagogical practices that we have at school are not fostering coexistence among children when stating that:

The great majority of schools in our contexts seek to promote coexistence through the teaching of knowledge or values. These approaches have limitations because either the teaching of knowledge… or the transmission of values [it is necessary to use a methodology] to translate into actions that foster coexistence. In other words, under these approaches, students appear to learn discourses but most often keep a distance between discourse and action. (p. 39)

Coexistence is experienced by stressing values, expressing feelings, and reflecting upon moments of conflict. Those expressions of love and coexistence emerged from the collaborative work and from the voice given to the children throughout the process (Douville & Wood 2001). Students started to understand that practicing values that promoted peaceful coexistence was necessary to complete the different tasks and to feel good while learning. They understood that making agreements and having group values was extremely important when working together towards a specific goal. The importance of this category deals with learners’ understanding of coexistence values to develop learning tasks together during the English class and for future life situations.

The following reflections demonstrate the values that students gained during the process and the way they addressed those values. The first excerpt stressed responsibility and listening to others as values learned in the process. The second excerpt also emphasizes the importance of listening to others, and the relevance of helping their classmates as a way to be friends and to avoid fighting. The third excerpt shows the value of respect as an important aspect of coexistence in which one person can learn from the others. This value is highlighted in the Basic Standards of Citizenship Competences by the Ministry of National Education (MEN), regarding being a citizen, “Ser ciudadano es respetar los derechos de los demás. El núcleo central para ser ciudadano es, entonces, pensar en el otro” (MEN, 2003, p. 150).

Hoy en clase de inglés yo aprendí es que debemos ser responsables con nuestras cosas y que uno debe escuchar a las personas que nos aconsejan, yo me alegre por eso.

Data source 7: From Students’ Reflections on August 28th, 2015

A convivir con los demás y aprendí a escuchar a mis compañeros y no voy ad ejar que Jhojan y Brayan sigan peliando voy a ser lo posible por que sean mejores amigos.

Data source 8: From Students’ Reflections on August 21th 2015

Hoy aprendi que tenemos que escuchar los demás compañeros para cuando estan exponiendo y necesitan que escuchemos porque eso es muy importante y que tambie podemos aprender de las demas personas, como palabras nuevas en inglés que ellos estan trabajando y nosotros no por lo de preguntas diferentes.

Data source 9: From Students’ Reflections on September 16th 2015

Another relevant aspect within this category that was identified in the students’ reflections was conflict solving and attitudes towards facing conflict. Those reflections are related to the coexistence and peace standards proposed for fifth graders, in which they acknowledge conflict as part of life (MEN, 2004). Thus, the standards that the students demonstrated through their reflections are: “Entiendo que los conflictos son parte de las relaciones, pero que tener conflictos no significa que dejemos de ser amigos o querernos” and “expongo mis posiciones y escucho las posiciones ajenas, en situaciones de conflicto.” Thus, fifth graders found situations of conflict as opportunities in life that could be faced for living better. They also understood that dialogue and dealing with problems are important stages for problem solving. The following pieces of data are samples of how the language classroom activities allowed the children to reflect upon conflict and to find in those conflicts opportunities for being better human beings. In sum, language activities are not isolated; they imply human behaviors and human responses, as the ones presented below.

Hoy aprendí que si uno se cae uno toca levantarse y además que una amistad dura para ciempre y que uno tiene que ser responsable por sus actos buenos cambiando de tema yo estoy muy alegre por mi desempeño en mi grupo porque hoy en lo de la cartelera nos pusieron un 50 todos nos alegramos todos somos espectaculares en todo soy feliz todo nos salio bien y pensar que era en inglés.

Data source 11: From Students’ Reflections on August 19th 2015

Nosotros hemos tenido muchos problemas Durante el proceso, por irresponsables y olvidadizos, por ejemplo, cuando ya íbamos a hacer el libro no trajimos os materiales, pero pues lo solucionamos llamando a mi mama que como nosotros vivimos aquí frente el colegio, pues ella me trajo todo. Bueno eso fue re fácil de solucionar. Aveces si no nos poníamos de acuerdo y eso nos tocó que la teacher nos ayudara para ponernos de acuerdo y pues ahí entendimos que eso toca es dialogar, osea hablar y no peliar, porque si uno pelea no hace nada, porque eso nos pasaba, nos poníamos a peliar y no hacíamos nada, pero ya cuando diagolamos, ehhh dialogamos, osea hablamos ya pudimos ponernos de acuerdo y hace las cosas.”

Data Source 12: Student Y. Field Notes September 23rd 2015

Translanguaging in the Oral and Written Texts of Fifth Graders as Inquirers

This third category stresses one of the most important characteristics that students’ verbal and written speeches demonstrated in the English class during the inquiry process. Fifth graders simultaneously used Spanish and English to express their ideas about the inquiry process and about school coexistence. The use of two codes is understood as translanguaging, which is different from the notion of code switching in the sense that it refers not simply to a shift or a shuttle between two languages. This is better explained by García (2009) who states that this language shift gives agency to speakers in an ongoing process of interactive meaning making.

The excerpt below shows how one student is asking if he can start using the words, he is learning in English, but completes his ideas in Spanish. He is recognizing new words but is not limiting his expression of ideas just because he does not know more words in the English code. The question posed by one of the students in terms of asking permission to do this language merge could be understood from García and Wei’s (2014) stance as “linguistic creativity and the translanguaging instinct” (p. 670) in which children have no problem using the multiple semiotic resources they have available.

S1: teacher si nosotros decimos que la bag el school snack tiene unos messages que dicen cosas como de reciclaje, ¿se puede?

Data Source 14: Student B. Field Notes May 27th 2015

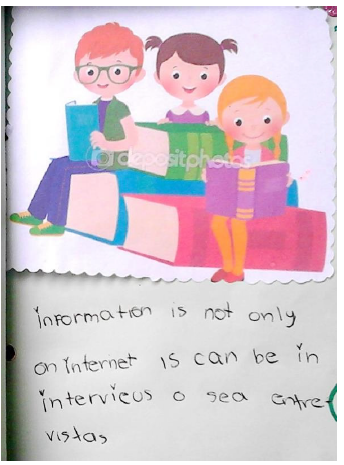

Following the same characterization of language use, Figure 3 shows one part of the book that reported the results of the inquiry process and what the students learned about the places where information is found. They mention interviews, and they clarify the English word with the Spanish words to accomplish the objective of sharing the proper messages they wanted to convey. The artifact more than bilingual is a multilingual text. The image, the Spanish and the English words, build the whole text to express their ideas, in the sense that it “shows the different ways multilingual children combine and juxtapose scripts as well as explore connections and differences between their available writing systems in their text making” (García & Wei, 2014, p. 1303).

Figure: 3. Data Source 16: From students’ Artifacts. Book about the experience.

Language gave the children the possibility to express how they experienced their coexistence during the collaborative inquiry. The fact that they used a different language from their mother tongue opens the doors to have more people knowing about their reflections. In that process, they needed to rely on their mother tongue to complete their ideas. Thus, translanguaging is not simply a way to “scaffold instruction, to make sense of learning and language; rather, translanguaging is part of the meta-discursive regime that students in the twenty-first century must perform” (Wright, Boun, & García, 2015, p. 147).

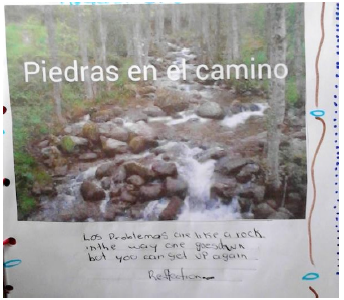

The use of both L1 and L2 also allows the use of visual literacy in which the images complement the words used. The last excerpt, taken from one of the students’ books about the experience, is a beautiful metaphor of the meaning of conflict. The girls in this group are using some words in Spanish-los problemas and piedras en el camino-the rest of the text is in English and they included a beautiful image to complement the idea they are expressing (see Figure 4). That text led me to address García’s (2014) ideas about emergent bilingualism in which children are not shy to use their entire language repertoire to make meaning, successfully communicating across ‘languages’ and ‘modes’ by combining all the multimodal semiotic signs at their disposal (García & Wei, 2014).

Figure 4: Data Source 17: From students’ artifacts. Book about the experience.

Conclusions

This study addressed a collaborative inquiry model in the EFL classroom as a way to unveil students’ reflections about their coexistence at school. Consequently, the conclusions can be stated in terms of the way this research transformed my pedagogical practices. It helped me to reshape my understanding about language teaching and learning, and the way language curriculum can be addressed from the standards of language learning established by the Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN, 2006). A more socio cultural perspective in the language classroom assumes the community as a source for learning and subjects like citizenship and science complement the language curriculum, giving content to the speeches produced in the EFL classroom.

The journey took one academic year and allowed me as researcher to learn about research, language teaching and learning, and about my students as great curriculum contributors. Students became co-constructors in the process of adjusting the language curriculum to the their communities. Such co-construction implied collaboration between students-students and teacher-students when inquiring and gaining new perspectives to learn through inquiry. The language classroom was transformed into a learning environment in which learning occurs both with and from students.

In this experience, the role of the teacher-researcher is different from the role of the teacher. Students were given the opportunity to pose questions and bring responses from which I was ready to learn. The teacher became an active inquirer, helped students to understand the inquiry process, but at the same time walked with the students throughout this process. Students brought new understandings to the language classroom when using community as a source; they were the experts in their contexts as well as the owners of information. In addition, they were the ones that oriented the process because they had clarity about what they wanted to learn and what they needed from language to express their knowledge.

Accordingly, the curriculum is not a static teaching entity; the language curriculum can be oriented towards other subjects. Language becomes the means by which to learn about the content of different subject areas, such as science, social studies, and math among others. The inquiries the students proposed opened the boundaries of the curriculum allowing community topics to be worked inside the language classroom as well as different language skills were developed while students completed their inquiry. The learning that occurred in the elementary language classroom went beyond the linguistic features of language. The students learned about carrying out an investigation, about nutrition, about recycling, and about dealing with conflicts in a collaborative environment. A positive outcome of the process of collaborative inquiry was a more peaceful learning environment that contributes to developing citizenship competences proposed by the Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN, 2004) in the Standards of Citizenship Competences. CBP in the language classroom changed the teaching environment into a more productive place where knowledge had no limits. What happened in the language classroom transcended the boundaries of school because students had become inquirers for life.

In addition, the research allowed students to produce complex texts in which they talked about a local aspect-the school snack. They also talked about what happened while they were exploring the content. In other words, inquiry fostered students’ learning beyond the language standards and connected to the standards from other subject areas. This clearly places the language classroom as a transdisciplinary place for learning while language serves as a vehicle for knowledge construction.

The reflections that were produced by students within the process are good examples of what the innovation intended to tackle. Students reflected on how to achieve a common goal by making agreements, overcoming problems, and facing and solving conflicts. The collaborative nature of the inquiry process helped scaffolding in the language learning process during the academic year. The teacher’s view was not enough; their classmates support was truly important. The zone of proximal development (ZPD) proposed by Vygotsky (1986) supported the language learning process by providing confidence to develop a foreign language from the understanding of language not as content but as a means of expression.

In general terms, inquiry in the EFL classroom is an excellent opportunity to consider language teaching and learning as more sociocultural. Reflections that emerged during the research allowed approaching language and other areas of knowledge in a more meaningful manner. The type of reflections described in the findings give account of the contributions of this methodology in the classroom as collaboration helps students to understand their roles as citizens in society (Chaux, Nieto, & Ramos, 2007). In other words, citizenship competences are put into action when students experience collaborative work (inquiry in this case), and have the opportunity to react to different circumstances. The data showed how students’ reflections acknowledge the other as someone to be taken into consideration and the importance of listening. It also contributes to language learning improvements stated by García and Wei (2014) in which there is a “transdisciplinary [view of language teaching] associated with translanguaging [that] enables us to broaden our disciplinary lens, bringing a simultaneous sociocultural-sociocognitive approach to the study” (p. 2575).

References

Appendix A

Basic Competences Standards for fifth Grade of Elementary School proposed by Colombian Ministry of Education that were taken into consideration in the pedagogical implementation

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.