DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.175Published:

2006-01-01Issue:

No 8 (2006)Section:

Theme ReviewCross-cultural understanding through visual representation

Keywords:

escritura en el segundo idioma, asignaturas de escritura, cruce-cultural, representación visual (es).Keywords:

second language writing, writing assignments, cross-cultural, visual representation (en).Downloads

References

Booth, Wayne C., & Marshall W. Gregory. (1987). Rhetoric: Writing as thinking, thinking as writing. New York: Harper & Row.

Hilligoss, Susan. (2000). Visual communication: A writer's guide. New York: Longman.

Horn, Robert. (1998). Visual language: Global communication for the 21st century. Bainbridge Island, WA: Macro-VU, Inc.

Kaplan, Robert. (1966). Cultural thought patterns in intercultural education. Language Learning, 16, 1-20.

Kaplan, Robert. (1987). Cultural thought patterns revisited. In U. Connor & R. B. Kaplan (Eds.), Writing across languages: analysis of L2 text (pp.9-21). Reading, MA: Addison- Wesley Publishing Company.

Kent, Thomas. (1999). Introduction. Post-process theory: Beyond the writing-process paradigm. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Kubota, Ryuko, & Al Lehner. (2004). Toward critical contrastive rhetoric. Journal of Second Language Writing 13, p. 7-27.

Lindemann, Erika, with Daniel Anderson. (2001). A rhetoric for writing teachers. 4th Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Olson, Gary A. (1999) Toward a post-process composition. Post-process theory: Beyond the writing-process paradigm. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Podis, Joanne M. & Leonard A. Podis. (2003). Beyond fear and (self-)loathing in the composition-literature wars: Contextualizing the politics of writing assignments in English Studies. Michelle M. Tokarczyk & Irene Papoulis. Teaching composition/teaching literature: Crossing great divides. New York: P. Lang.

Rosenblatt, Louise. (1994). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In Robert Ruddell, Martha Rapp Ruddell, & Harry Singer (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (pp.1057-1092). Newark, DL: International Reading Association.

White, Edward M. (1992). Assigning, responding, evaluating: A writing teacher's guide. 2nd edition. New York: St. Martin's.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2006-09-00 vol: nro:8 pág:137-151

Theoretical Discussion Papers

Cross-cultural understanding through visual representation

Kristina Beckman

E mail: kbeckman@jjay.cuny.edu

Susan N. Smith

E mail: snsmith@u.arizona.edu

Abstract

This article analyzes international students' drawings of their home countries' essay assignments. These English as a Second Language (ESL) students often have difficulty in meeting the local demands of our Writing Program, which centers on argumentative writing with thesis and support. Any part of an essay deemed irrelevant is censured as "off topic" some students see this structure as too direct or even impolite. While not all students found visual representation easy, the drawings reveal some basic assumptions about writing embodied in their native cultures' assignments. We discuss the drawings first for visual rhetorical content, then in the students' own terms. Last, we consider how our own pedagogy has been shaped.

Key Words:econd language writing, writing assignments, cross-cultural, visual representation

Resumen

Este artículo analiza los dibujos de los estudiantes internacionales que hicieron de su país natal para su tarea de composición. Estos estudiantes de inglés como segundo idioma a menudo tienen dificultad llenando los requisitos del programa de escritura cuyo enfoque es el discurso argumentativo con tesis y apoyo. Cualquier ensayo considerado irrelevante se censura y se considera estar "fuera del topico". Algunos estudiantes ven esta estructura demasiado directa e irrespetuosa. Mientras que no todos los estudiantes encuentran fácil la representación visual, los dibujos relevan ciertas características multiculturales básicias incrustadas en la escritura que se reflejan en las asignaturas. Primeramente discutimos los dibujos para el contenido retórico y luego lo discutimos utilizando la perspectiva de los estudiantes. Finalmente, analizamos como se formó nuestra propia pedagogía.

Palabras Claves:escritura en el segundo idioma, asignaturas de escritura, cruce-cultural, representación visual

In Composition classes, writing assignments usually include specific details about teacher expectations (White, 1999; Lindemann, 2001; and Podis and Podis, 2003). These expectations incorporate some basic assumptions about writing, e.g., that it must be assertive or incorporate evidence or cite "reliable" sources. Gary Olson encapsulates this process as it has been enacted in numerous composition classrooms:

Students are instructed to write an essay, which has usually meant to take a position on a subject (often stated in a "strong," "clear," thesis statement, which is itself expressed in the form of an assertion), and to construct a piece of discourse that then "supports" the position. Passages in an essay that do not support the position are judged irrelevant, and the essay is evaluated accordingly (1999:9).

All students entering the University of Arizona (UA) are taught this rhetoric of assertion, often based on Aristotelian rhetoric and including the metaphors of conflict (win or lose the argument, take sides, etc.). In the local culture of our Writing Program, this is the current paradigm. For some ESL students, conflict is to be avoided or negotiated, and assuming the role of champion of an idea may be seen as rude personal self-promotion. Even for local, native speakers, the writing of an argument may be a new assignment; local K-12 education focuses more on expressive writing than does our college program rather than a non-fiction, evidentiary essay.

Thomas Kent says that ´we all require beliefs that help us start to 'guess' about how others will understand, accept, integrate, and react to our utterances" (1999: 3-4). Students are constantly in search of "what the teacher wants,' although teachers generally try to shift that inquiry to "what the situation calls for." Over time, students listen in class and study comments on their papers for clues about what should be on the page. Eventually, they develop a "school writing" schema that helps them interpret the assignment and predict what is expected by the teacher. For ESL students, these past experiences come from differing cultures, where expectations about writing are quite different from those of teachers and students who are native speakers of English. Even local students may have been taught to describe or compare in a non-argumentative way. These underlying differences may lead to variations in interpretations of assignments and thus to confusing twists in student writing as students struggle to fit into another culture yet retain their own.

To unearth some of these unstated premises, Beckman asked her students to draw the writing assignment as given in their native culture. Asking students to visually represent ideas freed them from having to explain the process in English. Of course, "visual representation" is yet another language, and some students feel confident in this medium while others are reluctant to try this approach. Once the drawing was done, Beckman modeled a discussion of her own drawing, then asked students to explain theirs, now articulating the underlying ideas that were already represented, a less daunting task for non- native speakers. The process of discussion and sharing drawings allowed ESL students to identify their own personal criteria as well as to compare it to others', offering a rich source of definitions and directions in meeting an assignment. As Louise Rosenblatt explains, "[T]he emphasis on making underlying or tacit criteria explicit provides the basis not only for agreement but also for understanding tacit sources of disagreement. This creates the possibility of change in interpretation, acceptance of alternative sets of criteria, or revision of criteria" (1999: 1079). The discussion that followed provided specific insights into the personal writing processes of ESL students that might have been overlooked without the visual interpretation of the drawings. In addition, students observed their own tacit disagreement with some of the tenets of the local culture. Finally, students achieved an understanding of some of the tacit differences in the strategies for writing in both their home culture and their school's culture.

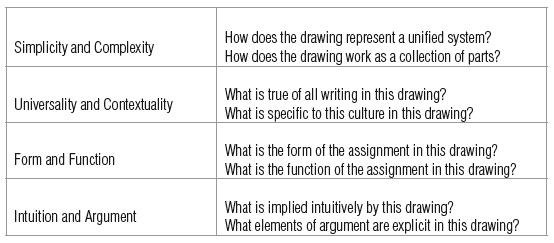

Smith: I first saw Beckman's students' drawings at a conference and was immediately drawn to them because they explained some of the questions I had as a college teacher of ESL students. The textbook I used insisted on thesis statements, yet some of my students were able to produce clever, well-reasoned writing without an identifiable thesis. We discussed this issue thoroughly in class, but some elements remained unexplained until I saw Beckman's students' drawings. The area of visual analysis is complicated by the interdisciplinary nature of the study of vision. Cognitive science, graphic arts, philosophy, rhetoric, communication, and other fields are exploring the nature of what we see. Reading extensively in the graphic design literature and the visual rhetoric literature, I noted that the two communities have very different values and rarely address each others' concerns. Creation of a heuristic helped me interpret the material; I started with issues from the graphic design community (articulated by Hilligoss, 2000), then developed opposites through my work in visual rhetorical analysis. I see each word pair as a continuum, and each drawn element fits somewhere between the two words. I took notes on each drawing under headings of the word pairs before I decided on an interpretation.

Each of these interpretations is my own; my interpretation depends not only on what is on the page, but also on my own personal history with the meanings of the individual elements and my experience in previous teaching settings. My observations here are meant not as an authoritative interpretation, but as one possible interpretation. Then, this interpretation may be compared to the student's own statements, given in Beckman's sections. The value of this exercise is in the communication about the drawing between student and teacher (or teacher and teacher). The interpretations are meant as a catalyst for discussion that may empower critical examination of what is expected in local academic writing and what a specific ESL student brings to the discussion.

Beckman: International students studying composition in American college and university settings bring with them different concepts about writing essays, such as making claims, providing support for these claims, and offering their own analysis. However, some international students find themselves writing assignments for instructors who have differing expectations about standard conventions; as a result, the students occasionally receive poor grades. In an effort to foster understanding for both students and faculty, this study examines the writing styles used by international students in their home countries. Using drawings, written explanations, and interviews, participants describe how they were accustomed to writing in their home countries. Every semester, students inevitably ask the question, "Why do I get in trouble for doing it that way?" They know that what they are doing is not valued by their American teacher, but remain mystified as to why not. Our hope is that this project will serve as a bridge between teacher and student.

Much of the work on ESL contrastive rhetoric was inspired by Kaplan's (1966) seminal work on comparative paragraph structures (further developed in Kaplan, 1987). Fondly referred to as the "doodles" article, Kaplan uses shapes to represent linguistic and stylistic patterns commonly found in students' first language (L1) writing. He attributes these displays to culturally specific logic and thought and explains that "each culture has a paragraph order unique to itself, and that part of the learning of a particular language is the mastering of its logical system' (14). However, some find this approach limiting in that it focuses primarily on differences rather than both shared and distinct features. Further, it places non-English languages as the 'Other,' a hierarchical implication that non-native speakers are somehow less than those whose first language is English. However, in recent years a modified approach, known as critical contrastive rhetoric, respects and embraces such differences (Kubota & Lehner, 2004). Rather than view differences as problematic, they affirm, "multiplicity of languages, rhetorical forms, and students' identities, while problematizing the discursive construction of rhetoric and identities, and thus allowing writing teachers to recognize the complex web of rhetoric, culture, power, and discourse in responding to student writing" (7). Our current research endeavor follows such an approach in that ESL students, through their pictures, share areas that are particularly challenging for them as non-native speakers. Moreover, we hope to elicit their understanding of the underlying assumptions and expectations of their home countries. Rather than viewing them as "Others," we consider them to be teachers, sharing their experiences with interested ESL composition instructors and students.

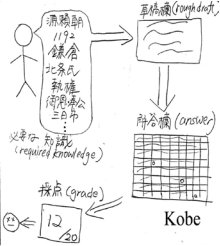

Smith: The author of the first drawing, Kobe (all student names are pseudonyms), shows a stick person with a conversation bubble showing Asian characters in a vertical list of items, one of which is a Western number, "1192." Underneath this bubble is the Asian title and an English translation, "required knowledge." The author may mean that he or she must have a great deal of background knowledge before even drafting a paper. This element is the most detailed, perhaps implying that much study is essential before writing, a state that UA teachers could applaud. The final draft is labeled as "the answer," a terminology that local students wouldn't necessarily use. In our composition classes, we are used to discussing problems, not necessarily solving them. Local teachers are hesitant to label even a well-supported argument as "the" answer; we acknowledge that the world is complicated and discussions end in possibilities, not certainties.

The form of Kobe's drawing is circular: starting with knowledge, going right to rough draft, down to a final draft/answer, and finally, a grade in a circular motion, perhaps subconsciously representing writing as recursive. The form indicates that this is a person who thinks in his native language first, then translates. The many parts here are shown in great detail, and the "answer"/ final draft is both systematic and nuanced, demonstrated by a detailed grid with both points and lines on it. Finally, the score naturalizes harsh criticism, in that the detailed work leads to a miserable person whose work is evaluated as inadequate. I empathized with the poignancy and humor of the face with x-eyes seeing the low grade.

Beckman: Kobe emphasized the importance of factual knowledge in his own educational background. A great deal of importance was placed on the amount of information a student was able to recall during an exam setting. He explained, "Much knowledge is automatically a big advantage. . . . Answers must include some particular words, dates, and facts to be complete." His training proved problematic for him when he began his studies in the United States because his usual method of exam preparation, memorizing facts, were of relatively little use when his exam was an in an essay response format. Drawing on what had always served him well, Kobe provided a lengthy response listing factual information. However, the instructors gave him weak marks citing problems such as lacking developmental coherence or straying from the original question.

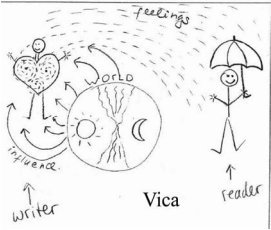

Smith: Next I looked at Vica's picture of a writer/reader pair, the writer shown with a body shaped like a heart. This diagram starts in the center with a picture of a globe, showing sun and moon, perhaps indicating that the writer is either taking a global view or showing his or her homeland, which is distant. The stylized drawing shows communication involving a writer and a one- person audience. The world's input is demonstrated by arrows pointing to the writer and labeled as "influence." Motion is everywhere in this picture: inside the writer's heart-shaped body, spirals of dotted lines surround points, representing the author's processing of the world's influence. Since the processing is done in the heart/body, this is not a cerebral kind of essay writing— the heart is the source of analysis, not the head. The one fully articulated item on the writer's and reader's bodies are all five fingers. The figures don't even have hair, so this may mean that hands have some special significance, perhaps hands-on work or a practical bent. The writing leaves the author in flowing dotted lines labeled "feelings." A writer who centers on feelings may be misunderstood by UA readers: many contemporary composition theories eschew the emotional response as too expressivist, not logical enough for college writing. The oddest part of this drawing is the reader; only two (of six) international students saw an essay as a transaction between writer and reader. The feelings of the essay arc from the writer across the world to the reader in almost rainbow shape. Perhaps this is why the reader is shown holding an umbrella, partly blocking out some of the feelings coming from the writer and symbolically showing that feelings don't always translate from writer to reader. At any rate, the reader doesn't receive all of the message sent by the writer, which is consistent with current reader response theory.

Beckman: This drawing captures Vica's outgoing and positive personality. She felt frustrated by the confines, as she considered them, of academic writing. Rather than presenting information in a neutral, professional manner, this Latvian student regarded an academic style of writing as dry and lifeless, an opinion shared by many in the academic community. She had been taught to view her native Russian as rich and elegant, yet when writing in English she had to "stick to the rules." One might account for such frustration as typical coming from someone writing in a second language; however, Vica was a high- level English speaker with only a slight accent and had spent most of her high school years studying in America. Even her strong language abilities did not help her overcome her resistance to a formal American style.

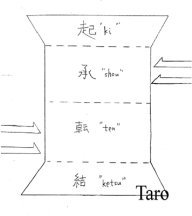

Smith: Taro's spool-shaped essay assignment was intriguing. This writer chose to use a ruler to draw his essay, which could be a sign of either rigor or rigidity of &quo;shape" and content of the essay. The precision and simplicity of this design may indicate a person who knows the writing process well. While this author imports information from outside, the arrows are drawn like barbs, not like real arrows, and rather than seeing them as additive, I saw the barbs as potentially pulling out from the essay. This considerate writer translated each Asian character, but the translation is into a western, phonetic spelling of the character, not a translation into English, so I couldn't understand what the words meant. This echoed some of my former students' experiences in their first English composition classroom—students who don't understand a definition in the first place may not understand a restatement, either. The flare of the shape at the top and the bottom reminded me of a formula high school students use: "Start with the world, narrow it down, then narrow more to your topic. At the end, reverse the order as a conclusion." I wondered if this drawing represents a similar idea, a case of international teachers teaching formula.

Beckman: This picture carries with it a sad tale about intercultural miscommunication. Taro was a law student in Japan before he came to study in the United States. He is the conscientious sort who made sure to clearly understand every separate element contained in an assignment. His meticulous nature is evident in the dotted delineation between "ki" start, "shou" receiving data from the first part, "ten&iquot; conversion, and "ketsu" conclusion. The arrows designate the inclusion of external sources. Sadly, Taro encountered difficulties when he included external sources that were not properly cited. In fact, they were not cited at all, which led to accusations of plagiarism. Taro, confused and distraught, brought his paper to me asking what he had done to fail. The professor's remarks were clear in identifying passages clearly not written by this student. When I asked Taro about this, he explained that, in Japan, it is insulting to a professor to overtly cite a source. Doing so implies that the professor is not familiar with this referenced author or subject area. Additionally, inherent in this is the suggestion that the student knows more than the professor. Such displays would be considered an affront. For Taro, he assumes the reader will make a distinction between his own writing and that of other authors. For this promising student, it was a hard cultural lesson to learn.

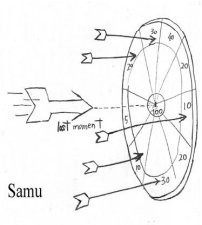

Smith: Samu, the author of the target, shows a circular approach to the essay, placing near-hit arrows all around the target. These "points' have various values, but they are not the center of the essay. The central topic isn't touched until the biggest arrow, which heads for the center. The motion lines in front of and behind the big arrow show that it is the only moving arrow, and therefore, the last. This reverses the usual UA way of announcing the topic in a thesis statement and then systematically proving it. The choice of the super-sized arrow as the last, dead on, shows that this writer approaches the topic only after investigating or explaining other options. This might be seen as a more generative theory than analytic—the stereotype of freshman student writing is that some freshman essays are best when reversed, with the conclusion becoming the introduction. The author of this drawing has unusual visual skills, in that the target is shown at an angle to the page, with perspective shown by longer arrows in the foreground and shorter ones in the back. The very skilled approach to showing which arrow was last, by using both lines of motion behind the arrow and a dotted line toward the center of the target, shows a sophisticated knowledge of design. The left-to-right progression may show an understanding of local thought.

Beckman: When this image has been on display at workshops, it was immediately familiar to other native speakers of Japanese. As Samu explained, "It seems to be relating to one of Japanese culture which is regarded as discreet, Japanese people is unwilling to say what's on mind first." Samu struggled with the UA style of beginning an argument with one's own opinion, describing the approach as rude. He maintained a strong resistance to adopting such an approach in spite of frequent negative comments from his other instructors. When using his Japanese style, Samu received comments such as 'weak', unclear', and "where are you going with this?" He felt more comfortable establishing his framework, discussing what others had considered, and finally, presenting his own interpretation. He noted that this can even be presented as late as the final paragraph. It is interesting to note that his arrow is the largest one and earns the highest point value. This certainly doesn't lead one to believe Samu considered his thoughts to be weak or unclear.

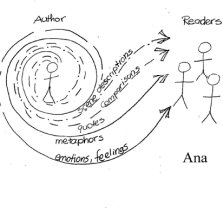

Smith: Ana's spiral representation is unusual in that she sees writing as a transaction that extends beyond the student-teacher exchange—this writing is intended for several readers. The writing itself is complex, composed of 4 distinct line styles, which are labeled scene descriptions, comparisons, quotes, metaphors, and emotions and feelings. The closest to American classrooms' argument is comparisons, though the rhetoric teacher might see that as only one mode of writing. The scene descriptions imply that the essay assignment is given in a literature course. That makes sense: subjects other than literature don't necessarily describe their end product as an "essay.' The writer describes a thorough, systematic process where all of the possibilities swirl around the writer before sorting out into the various parts and being given to readers. Again, the mention of emotions and feelings, which may be perfectly acceptable in some cultures, will be discounted in UA classrooms, where emotional evidence is denigrated.

Beckman: Ana, a devoted social activist in her last semester of her undergraduate studies, hailed from Peru. Much of her professional writing centered on finding and developing suitable housing accommodations for low-income residents. She felt passionate about her life's work, as is evidenced in this picture. Ana was puzzled by her supervisor's requests to tone down her level of enthusiasm in her professional writing. She considered emotions and feelings were appropriate in that given context. She shared, "The author is more poetic and romantic, which is the Spanish way."Ana also questioned the use of citations, questioning, "Whoever said that they said it first anyway?" These issues frustrated Ana as she was befuddled why compelling subject matter should be dealt with in such a sterile manner.

Smith: We should address the students whose drawings are not included in this paper. Some students did not find this an easy or enlightening assignment, since there are varying degrees of comfort with visual representation and differing cultural values for visual skills. Some students drew assignment representations that appeared to describe UA assignments; others' drawings were extremely simple but not easily interpreted. Some students unsure in English are also unsure in visual language, and even native speakers may have difficulty with code-switching from words to symbols. Therefore, this is not an effective technique with all students.

Of the drawings we chose to include, all used symbols like stick figures, arrows, and hearts in their drawings. They fit the definition of visual language given by Robert Horn (1998): "the integration of words, images, and shapes into a communication unit" (p. 8). However, the meanings generated are incredibly complex; arrows, for example, have multiple meanings, and in these drawings, these arrows might mean "interacts with," "proceeds to the next step," "flows into," "comes from outside," and so on. Horn reports that international agreement on the meaning of common symbols is very low; that problematizes every interpretation, especially by a person from outside a culture. Rather than looking for "the" assignment for either native student or ESL student, we used the drawings as a beginning for discussion. Extending a definition from one paper to an entire culture is impossible, since no culture employs only one means of teaching writing.

Even though the interpretive process may be fallible, this activity allowed both the teacher and the student to examine the underlying assumptions in both cultures about what goes into an essay and how it will be received. An old psychological axiom is, "If you can't name it, you can't fix it." The drawings elicited this naming process—a teacher might be unaware that Kobe expects his work to be judged harshly or that Samu's late introduction of a main idea is intentional. The teacher may respond by giving Kobe extra input on rough drafts, enabling him to put his hard work and thorough preparation to work in the local context before the grading process. Samu might receive coaching in the sequencing of ideas. The drawings may expose unspoken similarities and differences between the two cultures' expectations, facilitating change for the student in the local classroom culture while helping the student articulate, and thus retain, expectations in the home culture. For the teacher, the drawings may serve as a rich source of material for activities and discussion.

Beckman: This project stemmed from one of those rare "ah ha" teaching moments. Feeling frustrated that my explanation of our next writing assignment was unclear, I drew a picture of how I envisioned a rhetorical essay. As I looked out on twenty-five faces, I could see in their expressions that the drawing conveyed to them what my words could not. Inspired by our new mode of communication, I realized the potential this activity had. My primitive diagram contained all the elements of rhetorical analysis I considered important - the relationship between reader and writer, assumptions and presumptions held by each, as well as the strategies employed.

This project markedly changed my teaching approach. Although I continually strive to be sensitive to pedagogical concerns, there were areas that I had never considered addressing in my classes. As a result of using these drawings, I now incorporate a series of discussions and activities into my curriculum. First, it is important that the students recognize that stylistic similarities and differences do, in fact, exist. I make sure to emphasize that there are no right or wrong cultural writing styles - only different approaches. Not only is it important to acknowledge that there is no hierarchy among approaches, but students must be encouraged to hold onto the skills that they learned in their home countries. The aim is simply to add to their skill bases.

After our discussion, I give the students activities and exercises so that they can practice the new techniques covered in our class. I find it helpful for students to practice these techniques before they actually apply them in their own writing. When students have been given sufficient practice, they are given assignments with the expectation that they will demonstrate their ability to produce an essay that conforms to a traditional UA format. During this experimental drafting stage, students should have multiple attempts to practice and receive extensive instructor and peer feedback. In my classes, we strive for the integration of the students' skills with the expectations of the local university community.

Burdened with administrative as well as instructional concerns, sometimes teachers think in fifteen-week segments. However, learning from my students' drawings reminded me that students are passing through our classes on their way to other adventures. With luck, they'll leave with a healthy respect for their cultural backgrounds as well as a curiosity for the new and challenging.

References

- Booth, Wayne C., & Marshall W. Gregory. (1987). Rhetoric: Writing as thinking, thinking as writing. New York: Harper & Row.

- Hilligoss, Susan. (2000). Visual communication: A writer's guide. New York: Longman.

- Horn, Robert. (1998). Visual language: Global communication for the 21st century. Bainbridge Island, WA: Macro-VU, Inc.

- Kaplan, Robert. (1966). Cultural thought patterns in intercultural education. Language Learning, 16, 1-20.

- Kaplan, Robert. (1987). Cultural thought patterns revisited. In U. Connor & R. B. Kaplan (Eds.), Writing across languages: analysis of L2 text (pp.9-21). Reading, MA: Addison- Wesley

- Publishing Company.

- Kent, Thomas. (1999). Introduction. Post-process theory: Beyond the writing-process paradigm. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Kubota, Ryuko, & Al Lehner. (2004). Toward critical contrastive rhetoric. Journal of Second Language Writing 13, p. 7-27.

- Lindemann, Erika, with Daniel Anderson. (2001). A rhetoric for writing teachers. 4th Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Olson, Gary A. (1999) Toward a post-process composition. Post-process theory: Beyond the writing-process paradigm. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Podis, Joanne M. & Leonard A. Podis. (2003). Beyond fear and (self-)loathing in the composition-literature wars: Contextualizing the politics of writing assignments in English Studies. Michelle M. Tokarczyk & Irene Papoulis. Teaching composition/teaching literature: Crossing great divides. New York: P. Lang.

- Rosenblatt, Louise. (1994). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In Robert Ruddell, Martha Rapp Ruddell, & Harry Singer (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (pp.1057-1092). Newark, DL: International Reading Association.

- White, Edward M. (1992). Assigning, responding, evaluating: A writing teacher's guide. 2nd edition. New York: St. Martin's.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.