DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a05Published:

2015-10-23Issue:

Vol 17, No 2 (2015) July-DecemberSection:

Research ArticlesFacilitating vocabulary learning through metacognitive strategy training and learning journals

Promoción del aprendizaje de vocabulario a través del entrenamiento en estrategias metacognitivas y diarios de aprendizaje

Keywords:

diarios de aprendizaje, conciencia metacognitiva, estrategias metacognitivas, aprendizaje autodirigido, aprendizaje de vocabulario (es).Keywords:

learning journals, metacognitive awareness, metacognitive strategies, self-directed learning, vocabulary learning (en).Downloads

References

Anderson, N. J. (2002). The role of metacognition in second language teaching and learning. ERIC Digest, April 2002, 3-4.

Bailey, K. M., & Ochsner, R. (1983). A methodological review of the diary studies: Windmill tilting or social science? In K. M. Bailey, M. H. Long, & S. Peck (Eds.).Second language acquisition studies (pp. 188-198). Boston: Heinle &Heinle/Newbury House.

Barbosa, H. S. (2012). Applying a metacognitive model of strategic learning for listening comprehension, by means of online-based activities, in a college course. (Master’s thesis). Universidad de La Sabana, Colombia.

Burns, A. (2003). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Cambridge ESOL examinations (2005). Syllabus and Assessment Guidelines. Cambridge England: University of Cambridge.

Chamot, A.U., & O'Malley, J.M. (1994). The CALLA handbook: Implementing the cognitive academic language learning approach. White Plains, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Chamot, A.U. (2009). The CALLA handbook: Implementing the cognitive academic language learning approach, Second Edition, White Plains, NY: Pearson Education/Longman.

Cohen, L., &Manion, L. (1994). Research methods in education.(4th ed.) London: Routledge.

Cohen, L. Manion, I. & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education.(6th Ed.). London: Routledge Falmer.

Colombia, M. (2009). Improving new vocabulary learning in context. PROFILE Issues In Teachers' Professional Development, 2(1). Retrieved from http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/11343

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd Ed.).Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of References for Languages Learning Teaching, Assessment (2001). Cambridge University Press.

Deschambault, R. (2012). Thinking-Aloud as Talking-in-Interaction: Reinterpreting How L2 Lexical Inferencing Gets Done. Language Learning, 62(1), 266-301. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011.00653.x

Doran, G. (1981). There is a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management Review, 70(11), 35-36.

Ellis, G. (1999). Developing metacognitive awareness: the missing dimension. School of Education, University of Nottingham. Retrieved fromhttp://www.britishcouncil.org/portugal-inenglish-1999apr-developing-metacognitive-awareness.pdf

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906-911.

Klimenco, O., Alvarez, J., Londoño, S., Alvarez, S. & Bermudez, D. (2008). Teaching of the cognitive and metacognitive strategies in the first’s degrees of primary school how the education alternative for the students with the attention problems. Pensando Psicología, 5(8), 118-127. Revista de la Facultad de Psicología Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia.

Luchini, P., &Serati, M. (2010). Exploring second language vocabulary instruction: An action research project. The Modern Journal of Applied Linguistic, 2 (3), 252-272.

Martinez, M. E. (2006). What ismetacognition? Phi Delta Kappan, 87(9), 696-699.

Nation, P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nielsen, B. (n.d.). A Review of research into vocabulary learning and acquisition. Retrieved from http://files.myopera.com/bichlanau/blog/Vocab%20learning%20and%20

acquisition.pdf

Nunan, D. (1992). Research methods in language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunan, D. (1997). Strategy training in the language classroom: an empirical investigation. RELC Journal, 26, 56-81.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunan, D., & Bailey, K. (2009). Exploring second language classroom research. A comprehensive Guide: Heinle Cengage guide. Boston.

Orrego, L. & Diaz, A. (2010). The use of the foreign language learning strategies in English and French. Ikala revista de lenguaje y cultura. 15(24), 105-142.

Oxford, R. (2001). Language learning strategies. In R. Carter., & D. Nunan (Ed.) The Cambridge Guide to Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 166- 172.

Qing, M. (2009). Second vocabulary acquisition. Linguistic Insights. Studies in Language and Communication.Peter Lang Pub Inc; 1 edition.

Rasekh, Z.E., Ranjbary, R., (2003). Metacognitive strategy training for vocabulary learning. TESL-EJ 7, 1–17. Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/

volume7/ej26/ej26a

Rubin, J. (2003). Diary writing as a process: Simple, useful, powerful. Guidelines, 25(2), 10-14.

Rubin, J., Chamot, A. U., Harris, V., & Anderson, N. (2008). Intervening in the use of strategies. In A.D. Cohen & E. Macaro, (Ed.), Language Learner Strategy.Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp, 141-160.

Schmitt, N. (2000). Vocabulary in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Boxtel, C., Van der Linden, J., &Kanselaar, G. (2000). Collaborative learning tasks and the elaboration of conceptual knowledge. Learning and Instruction, 10(4), 311–330.

Wallace, C. (2007). Vocabulary: the key to teaching English language learners to read. Business Library. Retrieved from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb6516/is_4_44/

ai_n29414045/

Wheeldon, J. P., & Faubert, J. (2009). Framing experience: concept maps, mind maps, and data collection in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), 52-67.

Wang, J., Spencer, K., & Xing, M. (2009). Metacognitive beliefs and strategies in learning Chinese as a foreign language. System, 37(1), 46-56.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a05

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Facilitating vocabulary learning through metacognitive strategy training and learning journals

Promoción del aprendizaje de vocabulario a través del entrenamiento en estrategias metacognitivas y diarios de aprendizaje

Carmen Luz Trujillo Becerra1 Claudia Patricia Álvarez Ayure2 Mirtha Nohemí Zamudio Ordoñez3 Gloria Morales Bohórquez4

1I.E Jorge Eliecer Gaitán, Putumayo, Colombia. calutru@gmail.com

2Universidad de La Sabana, Chía, Colombia. claudiap.alvarez@unisabana.edu.co

3I.E Miguel Antonio Caro, Bogotá, Colombia. minanohemy@hotmail.com

4I.E Hernán Venegas Carrillo, Tocaima, Colombia. glomorbo@hotmail.com

Citation / Para citar este artículo: Trujillo, C. L., Álvarez, C. P., Zamudio, M. N. & Morales, G. (2015). Facilitating vocabulary learning through metacognitive strategy training and learning journals. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. 17(2), pp. 246-259

Received: 28-May-2015 / Accepted: 11-Aug-2015

Abstract

This paper reports on a mixed-method action research study carried out with participants from three public high schools in different regions in Colombia: Bogotá, Orito, and Tocaima. The overall aim of this study was to analyze whether training in the use of metacognitive strategies (MS) through learning journals could improve the participants’ vocabulary learning. The data, collected mainly through students’ learning journals, teachers’ field notes, questionnaires and mind maps, was analyzed following the principles of grounded theory. The results suggested that the training helped participants to develop metacognitive awareness of their vocabulary learning process and their lexical competence regarding daily routines. Participants also displayed some improvements in critical thinking and self-directed attitudes that could likewise benefit their vocabulary learning. Finally, the study proposes that training in metacognitive and vocabulary strategies should be implemented in language classrooms to promote a higher degree of student control over learning and to facilitate the transference of these strategies to other areas of knowledge.

Keywords: learning journals, metacognitive awareness, metacognitive strategies, self-directed learning, vocabulary learning

Resumen

Este trabajo da cuenta de un estudio mixto de investigación acción que se llevó a cabo con participantes de tres colegios públicos en diferentes regiones de Colombia: Bogotá, Orito y Tocaima. El propósito de este estudio fue analizar si el entrenamiento en el uso de estrategias metacognitivas a través de diarios de aprendizaje podría mejorar el aprendizaje de vocabulario de los participantes. Los datos fueron recogidos principalmente a través de diarios de aprendizaje de los estudiantes, notas de campo de los profesores y cuestionarios, los cuales fueron analizados siguiendo los principios de muestreo teórico. Los resultados sugieren que el entrenamiento ayudó a los participantes a desarrollar la conciencia metacognitiva de sus procesos de aprendizaje de vocabulario y su competencia léxica sobre sus rutinas diarias. De manera similar, los participantes mostraron actitudes de pensamiento crítico y de auto-dirección que pueden favorecer su aprendizaje de vocabulario. Finalmente, se propone que el entrenamiento en estrategias metacognitivas y vocabulario se implemente en la enseñanza de lenguas para promover un alto grado de control de los estudiantes en su aprendizaje y así facilitar la transferencia de estas estrategias a otras áreas de conocimiento.

Palabras clave: diarios de aprendizaje, conciencia metacognitiva, estrategias metacognitivas, aprendizaje autodirigido, aprendizaje de vocabulario.

Introduction

Vocabulary knowledge plays an important role in learning a second language; it is key to convey ideas in oral or written forms and also to receive information and to transform it into knowledge. In fact, the mediation of vocabulary is essential to employ any structure of linguistic knowledge in communication or discourse (Schmitt, 2000). Yet, though teaching and learning vocabulary is essential, doing so effectively can represent a challenge for both teachers and students. A needs analysis carried out in the preliminary stage of this research found that the participants, three groups of secondary school students from three different schools in Colombia, were concerned about their lack of knowledge regarding their own learning process, including the ability to evaluate the effectiveness of their own learning strategies. These deficiencies seemed to affect their ability to retrieve and use vocabulary. As an apparent consequence, students often gave up easily when they had difficulty learning new words. Moreover, through a combination of surveys conducted by the researchers, classroom tests, and external language examinations, students’ low vocabulary levels, lack of motivation, and field dependence (the tendency to be dependent on the field, in this case the teacher) were revealed.

These characteristics hindered learners from becoming active participants in their own learning and presented real obstacles in their efforts to become more strategic, independent, and self- directed learners. Accordingly, we formulated the following research question: How can learner training in planning, monitoring, and evaluating metacognitive strategies through learning journals help secondary school students improve their vocabulary learning process?

Review of the Literature

The Issue of Vocabulary

According to Ma (2009), learning vocabulary is defined as “knowing the meaning of the word and how to use it appropriately in different contexts” (p. 26); however, what ‘knowing a word’ signifies may not be easy to determine, especially for learners. Some researchers define what it means to know words by listing some elements of vocabulary knowledge. Nation (2001) proposes that a person masters a word when he/she knows its form, meaning, and uses. For the purpose of this study, vocabulary knowledge is also understood as including the students’ ability to recall and recognize a word in contextualized situations.

With regards to the present study, it is important to note that the researchers focused on explicit teaching of vocabulary related to specific daily routines. Some authors suggest that explicit vocabulary teaching is beneficial and necessary because, for beginners who do not yet have sufficient vocabulary knowledge, it is difficult to learn additional vocabulary through their own listening or reading. Additionally, by learning vocabulary through this explicit, direct approach, students can become more independent learners and better able to recognize the importance of L2 vocabulary instruction in the classroom (Colombia, 2009; Luchini & Serati, 2010; Nielsen, n.d.; Rasekh & Ranjbary, 2003).

Metacognition

Flavell (1979) defines metacognition as a blend of knowledge and regulation. What a student knows about themself as a learner and what they understand about strategies and how to use them, as well as how they monitor their learning during planning, performance, and evaluation, constitute this knowledge and regulation. Following this perspective, metacognition consists not only of strategy training but also of metacognitive awareness, or conscious higher order thinking, that can encourage students to reflect on their vocabulary learning process. Accordingly Martinez 2006) notes that “recent research suggests that metacognition improves with adequate instruction, providing convincing evidence that supports its importance in the instruction and learning process” (p. 696). Hence, the issue of metacognitive awareness is essential to this study as one of its objectives was for learners to assume a more active and meaningful role that led them to a better understanding of their own learning process and of the strategies that work best for them.

Metacognitive Strategies

Metacognitive strategies (MS) are defined by Chamot (2009) as “executive processes used in planning for learning, monitoring one’s own comprehension, production and evaluating how well one has achieved a learning objective” (p. 58). During this study, participants were trained in planning, monitoring, and evaluating their own learning. This process included (1) asking learners to decide on the most efficient methods for learning, (2) encouraging them to set their own goals and strategies (planning),

(3) determining whether or not the learning task was progressing by examining, regulating, and checking their comprehension and progress in the task (monitoring), and finally (4) checking on their success in accomplishing their goals and using learning strategies effectively (evaluating).

In recent years, researchers’ interests in MS has increased due to the positive effects that metacognitive strategy training (MST) has on learner performance. Klimenko, Álvarez, Londoño, Álvarez, and Bermúdez (2008) argue that it is necessary to emphasize an intracurricular integration of cognitive and metacognitive teaching strategies that allows students to learn how to organize their activities and become more familiar with their own particularities, which in turn can facilitate and increase student awareness regarding the use of metacognitive strategies. Similarly, a study carried out by Wang, Spencer, and Xing (2009, p. 54) on metacognitive beliefs and strategies in learning Chinese as a foreign language concluded that facilitating strong metacognitive beliefs and strategies empower second language learners to facilitate better and more effective learning. In a study focused on training learners in the use of a metacognitive model of strategic learning to foster listening comprehension, Barbosa (2012) concluded that participants improved their selective listening comprehension, as well as showed enhancement of cognitive and metacognitive awareness of the selective listening comprehension process, by applying direct attention strategies and completing a systematic listening process (pre- listening, while-listening, and after-listening) informed by the use of MS. Likewise, in a study on the effects of MST through the use of explicit strategy instruction on the development of lexical knowledge of EFL students, Rasekh and Ranjbary (2003) showed that the explicit use of MST in combination with careful planning, monitoring, and evaluation contributed to improvements in students’ vocabulary learning.

Language learning strategy training

Some studies have highlighted the positive effects resulting from training students in learning strategies (LS) defined as “techniques students can use to facilitate understanding, remembering, and using both language and content” (Chamot, 2009, p. 51). In this light, a study by Wallace (2008) emphasizes the importance and efficacy of combining direct instruction in vocabulary with word-learning strategies. Oxford (2001) argues that “strategy use early contributes to language learning” (p. 170), and Chamot (2009) asserts that learning strategy instruction is effective in producing increased use of strategies, enhancing learning, and transferring strategies to new tasks.

Participants in this study attended training sessions in the use of learning strategies intended to facilitate their vocabulary learning while simultaneously enhancing their awareness of the learning process by identifying the kinds of strategies that worked best for them. When students have the opportunity to reflect on weaknesses in their learning processes, they can enhance these (with appropriate strategies) and improve their outcomes. In a study on the use of LS in English and French as foreign languages,Orregoand Díaz (2010) emphasized the importance of training teachers and learners in the use of LS. In their view, when teachers do not have enough conceptual clarity about what LS are and how to teach them, they lose the opportunity to improve learners’ performance, especially with regard to the acquisition of attitudes and autonomous behaviors.

Learning Journals

Researchers in this study asked participants to maintain a written journal in which they recorded their perceptions about the development and use of MS. According to Bailey and Ochsner (1983), the central characteristic of a diary-type journal is that it is introspective; students can report their feelings, their language learning strategies, and their own experiences. The advantage of this tool lies in the possibility that researchers can collect data that in other cases is neither observable nor accessible to an external observer.

A diary journal is a useful research tool for reflecting on the learning processes. In an investigation into the effect of providing opportunities for reflection, self-reporting, and self-monitoring among university students in Hong Kong, Nunan (1997) found that giving opportunities to students to reflect on their learning through guided journals helped them to become more conscious of their learning process and to develop skills to connect what they wanted to learn with how they wanted to learn. Similarly, Rubin (2003) proposes instruction through diaries as a way to develop students’ metacognitive awareness about their learning and use of strategies.

Methodology

This mixed-method action research study (Cohen & Manion, 1994; Nunan, 1992) made particular use of the introspective method (Nunan & Bailey, 2009, p. 307), implemented through the use of learning journals. These allowed researchers to reflect on the metacognitive processes from the perspective of the participants and thus to understand issues that were not readily accessible through other means.

Context and participants

The study was conducted simultaneously at three public high schools in different parts of Colombia. The first school, the Jorge Eliecer Gaitán School, is located in Orito, in the Department of Putumayo. It has approximately 1,500 students. The school employs three teachers who teach English from sixth to eleventh grades. However, only the teacher who teaches tenth and eleventh grades holds a university degree in English teaching; the other two, who teach sixth to ninth grades, are licensed in teaching Spanish but do not have a degree in English teaching.

The second school, the Miguel Antonio Caro School, is located in Colombia’s capital, Bogota, D.C., and has approximately 1,200 students. Its English curriculum was designed by its English teachers and academic coordinator, and it is moreover modified and updated each year, based on student needs and the evolving national standards for English teaching.

The third school was the Hernan Venegas Carrillo School located in Tocaima, a small town in the Department of Cundinamarca. This school has approximately 2,250studentswithanEnglishcurriculum focused on grammar and reading comprehension.

The participants in this study consisted of 41 students, (20 females and 21 males), all first-language Spanish speakers. They were chosen randomly from sixth, eighth, and eleventh grades at the different participant schools. As participants were minors, researchers obtained informed consent from the participants’ legal representatives authorizing them to take part of the study. The sixth-grade students were from the Miguel Antonio Caro School (9 males and 5 females, aged 11 to 14). The eighth-grade students were from the Hernan Venegas Carrillo School (6 males and 6 females, aged 12 to 16) and the eleventh-grade students were from the Jorge Eliecer Gaitán School (6 males and 9 females, aged 15 to 17). In all three schools, English classes met three times a week for 55-minute periods.

Based on the participants’ performance during the English classes and the needs analysis carried out before the intervention, all the learners were at an A1 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001).

Furthermore the three groups were also preparing for the national state examination (Saber 11, Pre SABER) which test students on grammar and reading comprehension. The lessons were usually delivered under a teacher-centered methodology that seemed to contribute to the learners being field dependent and relying almost entirely on the teachers for their learning processes.

Data Collection Instruments

In order to collect data, this study drew on questionnaires, students’ learning journals, field notes, and mind maps. The use of different instruments allowed for triangulation (Burns, 2003) to increase reliability, credibility, and validity of the data analysis by comparing different perspectives from the different researchers and instruments. This contributed to a more comprehensive understanding of how the use of MS influenced the participants’ learning of the target vocabulary and increased the value of these findings.

Questionnaire.

The needs analysis questionnaire was designed to obtain information about student needs. Four

(4) of the 22 questions were related to students’ beliefs and needs about vocabulary learning, while eight were related to the use of MS. Additionally, the questionnaire included a list of 10 vocabulary learning strategies for students to select the ones they were already using . To insure validity and reliability, the questionnaire was proofread by colleague researchers who were familiar with the target population and then piloted by applying it to two individuals drawn from the same schools within the studied population but who were not part of the sample. The results of this process help ensure that the final questionnaire will be both more manageable for the studied population and provide more relevant information (Nunan & Bailey, 2009).

Students’ learning journals.

A learning journal template oriented towards capturing information on MS was created to help participants record and retrieve information more easily. After each intervention, participants were asked to write about their thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and reasoning processes in Spanish. They also self-evaluated their performance in the activities by responding to a group of open and multiple choice questions framed around each of the three strategies involved (planning, monitoring, and evaluating). This procedure allowed them to reflect on their metacognitive process, the number of words they had learned and the problems and solutions they faced regarding vocabulary learning during the activities. As learning journals were one of the main instruments for collecting data, the use of the students’ native language (Spanish) allowed participants to express themselves better, thereby enhancing the quality and quantity of students’ journals entries.

Field Notes.

To derive information from observations, the researchers took field notes to regularly register the activities that were carried out in as much detail as possible. These notes included observations and initial analyses of activities and experiences they considered relevant to the study.

Mind maps.

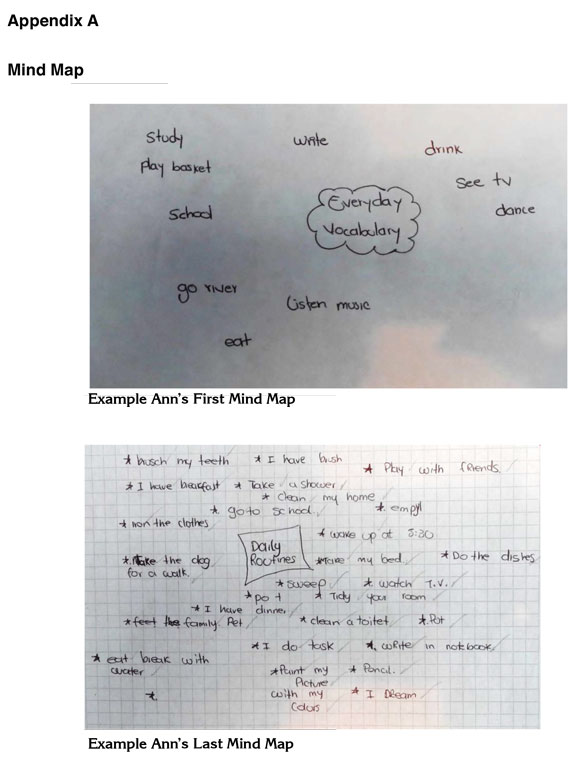

Mind maps provide a visual representation of dynamic schemes of understanding within the human mind. In the words of Wheeldon and Faubert, (2009) mind maps “might improve the validity of the data collected by forcing participants out of practiced scripts and narratives” (p. 79). For the purposes of this project, students were asked to use a mind map in two different moments during the intervention. Before the intervention, in order to determine their prior knowledge on vocabulary related to daily routines. After the intervention in order to determine whether there was a change in the number and characteristics of words they might have learnt.

Instructional design

The cycles pertaining to this study included three stages: pre-, during-, and post-implementation.

Pre-implementation

This stage was completed in two steps. Firstly, a needs analysis questionnaire and a mind map (Appendix A) were used to determine the students’ needs in terms of lexical competence, use of strategies, and previous knowledge. Secondly, teachers’ field notes were used (beginning in this stage, and throughout the others) to record data on student performance during the intervention.

During-implementation.

The implementation took place over a period of three months. The first two weeks were invested in MST, in which the researchers first introduced students to the use of MS and to reflect on its importance and effectiveness. Then, they had students focus on vocabulary related to daily routines, as well as on the cognitive strategies and MS for learning vocabulary that would allow the researchers to identify the most frequently used strategies. Finally, the learning journal template was introduced as an instrument of reflection. The remaining ten weeks were spent on the application of the lesson plans and the students’ reasoning process through the use of the learning journals.

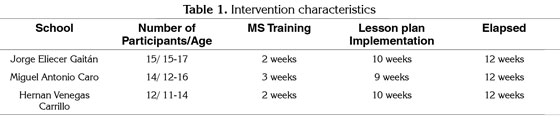

Table 1 depicts the number of participants, their ages, and the number of weekly hours scheduled for the interventions which had to be adjusted to meet each school’s calendar of activities.

Lesson Planning.

The implementation was carried out using five lesson plans which were designed to promote the use of MS during the classes. The lesson plans followed the ICELT (In-service Certificate in English Language Teaching, Cambridge ESOL, 2005) lesson plan template and the four phases of the instructional method of Chamot and O’Malley (1994), Cognitive Academic Language Learning Approach (CALLA), which provides a useful framework for direct language learning strategies instruction.

Preparation.

During this phase, the students were guided to plan the class objectives themselves with the aid of the teacher. Then the researchers helped them identify the strategies they already used and encouraged them to develop metacognitive awareness in regard to their vocabulary learning process. In this phase, the researchers explained the importance of metacognitive learning strategies.

Presentation.

As the lessons progressed, researchers also trained the students in MS by means of modeling and think aloud protocols (Deschambault, 2012) –speaking their minds while completing a task similar to the one the students had to perform. While modeling the process, the researchers made references to the strategies used, explaining any difficulties they encountered in the process and prompting students to reflect on the effectiveness of their use and how using the strategies could help them become more effective learners.

Practicing.

In this phase, the students practiced the target vocabulary through its use in different learning tasks, and researchers and students discussed how the strategies had been used as well as which the students preferred. Students were expected to make conscious efforts using the MS through the learning journals in combination with the vocabulary learning activities.

Self-evaluation

Through the use of learning journals, students reflected on their own learning and evaluated their success in the use of MS and in vocabulary learning by expressing their opinions and beliefs. Throughout the activities, the researchers clarified instructions and addressed learners’ difficulties regarding the use of MS and the learning journals.

The researchers observed that some students were initially reluctant to use the journals at first, perhaps because they were not used to reflecting on their learning and performance. The eighth graders, in particular, were more laconic in their written reflections, leaving the teacher-researchers without a clear understanding of their opinions. As a result, it was necessary to include two additional hours of MS training to clarify doubts and guide the eight- grade participants on effective use of the journals. However, most of the sixth-grade students seemed to be highly engaged with their journals, expressing their ideas openly. Similarly, the eleventh graders were thoughtful and clear in their reflections, allowing a more comprehensive retrieval of data.

Post-implementation stage

During this stage, at each school, the teacher- researchers used two hours of class time to develop the final mind map to determine what changes (if any) had taken place in the students’ vocabulary in terms of the number of words related to daily routines they could use; also, students were prompted to write a journal entry about their perceptions on the use of MS.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed following the grounded theory approach (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007). The researchers considered the data collected from each instrument to make the initial classification; then, data was grouped in charts based on the relation among categories, which were illustrated with excerpts taken from students’ journals and teachers’ field notes.

Results

During this process three categories emerged: 1) awareness of the learning process, 2) improvement of lexical competence, and 3) learning journals as a strategy training tool.

Awareness of the learning process

This category involved the main process students faced during the intervention: the use of MS, which according to Schmitt (2000) “involves a conscious overview of the learning process and making decisions about planning, monitoring or evaluating the best way to study” (p. 136). During the pedagogical intervention, students participated in activities that allowed them to reflect on what they already knew after which they learned about and used strategies that created opportunities to reflect upon their learning process (setting objectives, being aware of their learning difficulties while monitoring, and self-assessing the activities). Excerpts 1-3, drawn from the learner’s journals, exemplify their awareness.

“Aprender a escribir las palabras sin errores y así lograr escribir un párrafo en el que solamente las palabras estén en mi mente” (Excerpt 1. Journal 2 - My day at school).

Excerpt 2 illustrates the students’ reasoning process in relation to their innate strategy knowledge: repetition and association.

“Realizar un listado de todas las palabras, y así conocer cómo escribirlas y repetirlas muchas veces, asociarlas con las cosas de la vida cotidiana” (Excerpt 2. Journal 1 – My daily routines).

Here it is worth mentioning that one of the most useful and meaningful strategies for students was team work, because it allowed them to support each other in a more confident way—which, in turn, helped them understand some topics better and solve their difficulties more easily.

“When some of the group could not find an answer they look for support of other groups” (Excerpt 3. Teacher’s field notes 1 - My daily routines)

These excerpts provide evidence that students started to incorporate MS in their learning process as they made important decisions about what they would learn, how they would go about it, and how well they succeeded in their vocabulary learning. This evidence further validates the observation by Chamot (2009) that “students who are mentally active and who analyze and reflect on their learning process will learn, retain and be able to use new information more effectively” (p. 6).

Journal Excerpt 4 below indicates that students focused on three aspects—what they were doing, which strategies they used, and how well the strategies served their purposes.

“A veces se me olvidaba lo que iba a decir de mis rutinas diarias porque las palabras no se me quedaban, lo solucioné mirando cuáles eran las que se me olvidaban y las grababa en mi celular para escucharlas en casa y así aprenderlas” (Excerpt 4. Journal 1 - My daily routines).

When students reflected on their learning process, they became aware of their learning difficulties using two metacognitive components: “declarative and procedural knowledge” (Chamot, 2009, p. 54). The excerpt below indicates the student’s awareness of his/her learning difficulties and the strategies that would possibly work—declarative knowledge.

“Me distraigo con facilidad y se me dificulta aprender las palabras largas debo estar viendo el cuaderno y concentrarme” (Excerpt 5. Journal 1 - My daily routines).

All of these processes involved students’ affective factors, characterized by the identification of their strengths and limitations when they faced difficulties or achieved their goals.

“Dudas de cómo se escribían las palabras, creo que era la inseguridad en uno mismo, creo que también el no repasar crea dudas” (Excerpt 6. Journal 1- My daily routines).

“Omar and Nicolas are happy because they feel their attitude regarding their capacities in English changed; they are more positive and confident about themselves” (Excerpt 7. Teacher’s field notes. Journal 5 - My vacations).

These kinds of reflections about their feelings were strong indicators of students’ awareness of their learning process and how they performed during the activities. Anderson (2002) states that “the use of metacognitive strategies ignites one’s thinking and can lead to more profound learning and improved performance” (p. 3). Participants in this study who used these strategies (planning, monitoring, and evaluating) seemed to have better control over their learning process, which in fact may enhance their learning and performance.

Improvement of lexical competence

This category emerged from the analysis of the insights and perceptions expressed by the students and the teacher-researchers in their reflections, needs analyses, and mind maps. When learners were more engaged in the class activities, they became aware of their difficulties, improved their lexical competence, and raised their learning independence,supportingChamot’s(2009) argument that, “when imperfect learners begin to develop metacognitive knowledge and strategies, they begin to exercise control over their own learning and develop autonomy as learners” (p. 55).

Excerpt 8 illustrates how participants were aware of the need to engage with the subject; for this reason they paid close attention to the instructions given by the teacher and worked harder during the activities.

“Trabajar con más dedicación, prestar más atención a la clase, ser un poco más atenta, meterle más ganas y ser más optimista” (Excerpt 8. Katerine. Journal 4-free time).

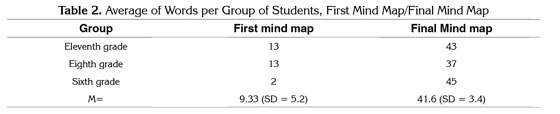

The training in MS played a definitive role in the development and refinement of the participants’ lexical learning as the average number of words related to daily routines in their vocabularies increased from a mean of 9.3 (SD = 5.2) at the beginning of the study to a mean of 41.6 (SD = 3.4) at its conclusion (see Table 2).

The following Excerpts provide some examples of enhancement of lexical competence from the learners’ and teacher-researchers’ perspective.

“Analyzing their academic advance and what they write on their journals I can observe that the number of words that the students use to express their daily routines has increased, now they are able to write a complete paragraph about what they used to do at school without problem” (Excerpt 9. Teacher’s Field notes 2 - My day at school).

“Aprendí muchas de ellas (palabras), las estrategias me fueron útiles conocí mucho vocabulario nuevo y pude traducir, además logre escribir una serie de actividades y poco utilicé el diccionario” (Excerpt10. Journal 3 - Chores).

This knowledge of the target vocabulary had a direct influence on learners’ independence during the activities, as can be seen in the following excerpts.

“Aprendí a relacionar y preguntar y no pedir copia” (Excerpt 11. Journal 3 - chores)

“Student Omar seems to be more confident in his performance during the activity and works hard, he does not need constantly help from his partner Sara, in this moment he is more independent than before” (Excerpt 12. Teacher’s journal 4 - Free time).

These are transcendent components for successful and meaningful vocabulary learning in a self-directed way; this supports Chamot’s (2009) argument that “with metacognitive awareness, students begin to see the relationship between the strategies they use and their own learning effectiveness, they plan for and reflect on their learning, and gain greater autonomy as a learner” (p. 54).

Learning journals as a strategy training tool

Data analysis showed the importance that learning journals had as a training tool for the enhancement of students’ metacognition because the students started to self-reflect on their cognitive process through the journals and in this way self- assessed their performance during the activities. This supports Chamot’s views (2009) “in the self-evaluation phase, students check the level of their performance so that they can gain an understanding of what they have learned” (p. 91). Excerpt 13 exemplifies how students assessed their performance:

“Pude escribir un párrafo en inglés sin ver el diccionario y el cuaderno, recordé muchas palabras. No alcancé del todo mi objetivo pero estoy satisfecha aprendí mucho” (Excerpt 13. Journal 1 – my daily routines).

Accordingly, the researchers determined that the learning journals helped the participants to develop MS, which in turn helped them improve both their vocabulary learning and their attitude toward learning in general. This seems to support Ellis’s (1999) observation that:

with metacognitive awareness, students develop a greater understanding of themselves as language learners, become more actively and personally involved in the learning process, more confident, more curious and ask more questions, and develop strong motivation and positive attitudes towards language learning. (p. 8)

Discussion

From the results of the present study, it can be noted that, from the perspective of the participants and the researchers, that the use of MS through learning journals had a positive effect on both learning awareness and lexical competence. When the researchers contrasted the results of the first and final questionnaires, it was evident that most of the participants thought that “vocabulary is essential for learning English” even though students did not devote much time to studying it. In fact, after the pedagogical intervention, some students’ perspectives regarding the use of strategies changed; they became more critical and realistic about the strategies they actually used for vocabulary learning.

Another important finding concerned the use of social strategies for vocabulary learning and collaborative work among students. Collaborative work was one of the main strategies used during the activities as the students felt confident when they had the opportunity to negotiate and solve problems through interaction with classmates rather than asking the teacher for help because the students’ peers are often at the same level of thought. This seems to support Van Boxtel, Van der Linden, and Kanselaar (2000) ideas that “collaborative learning activities allow students to provide explanation of their understanding which can help students elaborate and organize new knowledge” (p. 311).

The data collected through the mind maps demonstrated that the opportunities for training and practice with MS helped students to enhance their lexical competence, increase the number of words known, use more verbs and basic expressions about daily routines, and decrease the number of misspelled words. As a result of the students’ better performance regarding communication about daily routines, they felt more motivated and possibly better prepared to continue their language learning process. This appears to support Chamot’s (2009) observation that “one of the goals of strategy instruction is to alter students’ beliefs about themselves” (p. 76). In this study, when students recognized their difficulties during activities and consciously tried to solve them, they understood that success or failure in learning depended largely on their commitment and more appropriately on their use of strategies rather than on their lack of ability to learn a new language.

In addition, researchers conclude that the participants’ awareness about themselves has been influenced positively. The students are now able to select their preferred strategies, ask for help when they consider it necessary, identify their strengths and limitations, and work collaboratively with their peers. This is very important for successful learning and specifically for this study, given that the lack of awareness of themselves as learners had contributed to many of the participants feeling frustrated and giving up when they faced a problem. This aligns with Nunan’s (2004) observation that “there is growing evidence that an ability to identify one’s preferred learning style, and reflect on one’s learning strategies and processes, makes one a better learner” (p. 65).

One of the major findings of this study concerned the relationship established between the students’ use of MS, the enhancement of their vocabularies, and their increased learning independence. Students became aware of their learning process (use of strategies, learning difficulties, feelings, and need of attention and dedication to class) while they focused on vocabulary learning. These processes help them develop greater autonomy and self-confidence, supporting the notion that strategy instruction should be “designed to enable students to be independent and autonomous learners […] through strategy instruction, self-esteem and self- confidence increase accordingly” (Chamot, 2009, p. 77).

Finally, the analysis of the data leads the researchers to conclude that explicit training in MS helped the participants to simultaneously improve in different aspects of their learning process, fostering self-reflective learning through the use of MS, facilitating vocabulary learning, and enhancing their perceptions of themselves as learners, which positively influenced their learning performance during English classes.

Conclusions

Today’s learners must assume an active role in their learning and be equipped with strategies and tools that guide them in reflecting on their learning process and to achieve more effective performance. In the present study, participants were trained in planning, monitoring, and evaluating metacognitive strategies through learning journals with the aim of helping them improve their vocabularies on daily routines. The results revealed that the training had positive effects on students’ lexical competence. In fact, as students received more training and became better users of MS, they improved their metacognitive awareness and their lexical competence, which led them to take specific actions to assume control of their own activities and to learn more effectively. As a result, the students’ range of vocabulary increased. Furthermore the study revealed that the use of journals helped participants to reflect upon their difficulties and propose solutions to overcome their problems. This advance represented a crucial step forward in the development of their lexical competence as the students self-evaluated and put into practice their innate strategies to improve their vocabulary learning and performance. In sum, opportunities for reflecting through the use of learning journals helped students become aware of their learning process and increase their metacognitive knowledge and awareness about themselves, allowing greater control over their learning.

In the same way, one important effect that the use of learning journals for enhancing metacognitive awareness had on students was that they assumed a more active role in their learning process. Indeed, the learning journals were key instruments that helped students identify their strengths, weakness, and feelings. This, in turn, helped them overcome their difficulties and become more active and committed with their English classes. In this way, they became more independent and reflective learners in general.

Throughout the study, participants enhanced their metacognition by means of explicit instruction which contributed to increasing the students’ use of strategies and, indeed, overall learning. Additionally, the use of MS increased the students’ engagement in their metacognitive process and progress by helping them develop awareness about themselves when they planned, monitored, and evaluated their vocabulary learning. This also had a positive influence on their self-confidence and performance.

In sum, this study illustrates the importance of providing students with strategies that help them to become more autonomous and effective learners. In addition, it supports the notion that the explicit teaching of vocabulary is a critical factor for enhancing vocabulary learning and, in turn, developing learners’ independence.

Pedagogical implications

This research project explored the use of MS within an English language teaching curriculum. The implementation of training in MS implies some pedagogical changes–the way lessons are planned, the roles of students within their learning process, the implementation of strategy training—in order to improve and introduce new English practices that would be significant not only for the EFL subject but also on an inter/multidisciplinary level.

Conducting a project like this requires having sufficient knowledge about metacognition to provide the teachers and students with clear conceptions about the implications of putting the training on MS into practice. A further study in this area would require that schools, coordinators, and principals provide opportunities for training teachers. In this way, schools could enhance pedagogical practices by developing new curricula that specifically include the use of learning strategies.

The implementation of this study required training students in learning strategies. In context of this study, the students needed to learn both academic content and a foreign language; both can be facilitated by appropriate strategy training, which in turn enhances independent learning and “expansion,” which is the ability to transfer strategies to new tasks (Chamot, 2009). In this respect, teachers should provide students with plenty of opportunities to apply the strategies and give them explicit suggestions about how to use them in different contexts. Moreover, a study of this nature requires training students in setting S.M.A.R.T. (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Timely goals) goals (Doran, 1981), with which the student focuses on “why” they develop the activities, which in turn can facilitate their performance in the learning process to a significant extent.

Also, training in MS may influence the students’ success in other areas.

This can be encouraged through activities that provide them with opportunities to self-evaluate and reflect on their learning, such as the use of learning journals, checklists, or class discussions on what successful learners do. These kinds of activities may help the students to find the strategies that work best for them and to create their own repertoires of strategies.References

Anderson, N. J. (2002). The role of metacognition in second language teaching and learning. ERIC Digest, 3-4.

Bailey, K. M., & Ochsner, R. (1983). A methodological review of the diary studies: Windmill tilting or social science? In K. M. Bailey, M. H. Long, & S. Peck (Eds.). Second language acquisition studies (pp. 188-198). Boston: Heinle & Heinle/Newbury House.

Barbosa, H. S. (2012). Applying a metacognitive model of strategic learning for listening comprehension, by means of online-based activities, in a college course. (Master’s thesis). Universidad de La Sabana, Colombia.

Burns, A. (2003). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Cambridge ESOL examinations (2005). Syllabus and assessment guidelines. Cambridge, England: University of Cambridge.

Chamot, A.U. (2009). The CALLA handbook: Implementing the cognitive academic language learning approach (2nded.). White Plains, NY: Pearson Education/Longman.

Chamot, A.U., & O’Malley, J. M. (1994). The CALLA handbook: Implementing the cognitive academic language learning approach. White Plains, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1994). Research methods in education (4thed.) London: Routledge.

Cohen, L., Manion, I., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education (6thed.). London: Routledge Falmer.

Colombia, M. (2009). Improving new vocabulary learning in context. PROFILE: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 2(1), 22-24. Retrieved from www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/11343

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of References for Languages Learning Teaching, Assessment (2001). Cambridge University Press.

Deschambault, R. (2012). Thinking-aloud as talking-in- interaction: Reinterpreting how L2 lexical inferencing gets done. Language Learning, 62(1), 266-301. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011.00653.x

Doran, G. (1981). There is a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management Review, 70(11), 35-36.

Ellis, G. (1999). Developing metacognitive awareness: The missing dimension. School of Education, University of Nottingham. Retrieved from: http://www.britishcouncil.org/portugal-inenglish-1999apr- developing-metacognitive-awareness.pdf

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906-911.

Klimenko, O., Álvarez, J., Londoño, S., Álvarez, S., & Bermúdez, D. (2008). Teaching of the cognitive and metacognitive strategies in the first’s degrees of primary school how the education alternative for the students with the attention problems. Pensando Psicología: Revista de la Facultad de Psicología Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia, 5(8), 118-127.

Luchini, P., & Serati, M. (2010). Exploring second language vocabulary instruction: An action research project. The Modern Journal of Applied Linguistic, 2(3), 252-272.

Ma, Q. (2009). Second language vocabulary acquisition. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang.

Martinez, M. E. (2006). What is metacognition? Phi Delta Kappan, 87(9), 696-699.

Nation, P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nielsen, B. (n.d.). A review of research into vocabulary learning and acquisition. Retrieved from: http://www.kushiro-ct.ac.jp/library/kiyo/kiyo36/Brian.pdf

Nunan, D. (1992). Research methods in language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunan, D. (1997). Strategy training in the language classroom: An empirical investigation. RELC Journal, 26, 56-81.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunan, D., & Bailey, K. (2009). Exploring second language classroom research: A comprehensive guide. Boston: Heinle.

Orrego, L., & Diaz, A. (2010). The use of the foreign language learning strategies in English and French. Íkala: Revista de lenguaje y cultura. 15(24), 105- 142.

Oxford, R. (2001). Language learning strategies. In R. Carter & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages (pps. 166-172). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rasekh, Z. E., & Ranjbary, R. (2003). Metacognitive strategy training for vocabulary learning. TESL-EJ 7, 1–17. Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume7/ej26/ej26a

Rubin, J. (2003). Diary writing as a process: Simple, useful, powerful. Guidelines, 25(2), 10-14.

Schmitt, N. (2000). Vocabulary in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Boxtel, C., Van der Linden, J., & Kanselaar, G. (2000). Collaborative learning tasks and the elaboration of conceptual knowledge. Learning and Instruction, 10(4), 311–330.

Wallace, C. (2008). Vocabulary: The key to teaching English language learners to read. The Education Digest, 73(9), 36-39. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/218186066?accountid=45375

Wang, J., Spencer, K., & Xing, M. (2009). Metacognitive beliefs and strategies in learning Chinese as a foreign language. System, 37(1), 46-56.

Wheeldon, J. P., & Faubert, J. (2009). Framing experience: Concept maps, mind maps, and data collection in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), 52-67.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.