DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.17827Published:

2022-08-17Issue:

Vol. 24 No. 2 (2022): July-DecemberSection:

Research ArticlesExploring autonomous language learning behaviors through video sharing and online discussions in higher education

Exploración de comportamientos autónomos en el aprendizaje de idiomas a través del uso compartido de videos y debates en línea en la educación superior

Keywords:

aprendizaje autónomo de idiomas, aprendizaje de idiomas asistido por computadora, pandemia de coronavirus, discusiones en línea, intercambio de videos (es).Keywords:

autonomous language learning, computer assisted language learning, coronavirus pandemic, online discussions, video sharing (en).Downloads

References

Alpala, A. O., & Flórez, E. R. (2011). Blended learning in the teaching of English as a foreign language: An educational challenge. HOW Journal, 18(1), 154-168. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4994/499450717010.pdf

Al Asmari, A. (2013). Practices and prospects of learner autonomy: Teachers' perceptions. English Language Teaching, 6(3), 1-10. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1076656 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n3p1

Bajramia, L. (2015). Teacher's new role in language learning and in promoting learner autonomy. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 199, 423-427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.528 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.528

Bedoya, P. A. (2014). The exercise of learner autonomy in a virtual EFL course in Colombia. HOW Journal, 21(1), 82-102. https://doi.org/10.19183/10.19183/how.21.1.16 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.1.16

Benevenuto, F., Pereira, A., Rodrigues, T., Almeida, V., Almeida, J., & Gonçalves, M. (2010). Characterization and analysis of user profiles in online video sharing systems. Journal of Information and Data Management, 1(2), 261-261. https://periodicos.ufmg.br/index.php/jidm/article/view/38

Boateng, R., Boateng, S. L., Awuah, R. B., Ansong, E., & Anderson, A. B. (2016). Videos in learning in higher education: Asessing perceptions and attitudes of students at the University of Ghana. Smart Learning Environments, 3(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-016-0031-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-016-0031-5

Blair, E. (2016). A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 6(1), 14-29. https://doi.org/10.2458/azu_jmmss.v6i1.18772 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2458/azu_jmmss.v6i1.18772

Dang, T. T. (2012). Learner autonomy: A synthesis of theory and practice. The Internet Journal of Language, Culture and Society, 35(1), 52-67. https://aaref.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/35-08.pdf

Díaz-Ramírez, M. I. (2014). Developing learner autonomy through project work in an ESP class. HOW Journal 21(2), 54-73. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.2.4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.2.4

Farivar, A., & Rahimi, A. (2015). The impact of CALL on Iranian EFL learners’ autonomy. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 192, 644-649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.112 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.112

Flores, J. F. (2015). Using the web 2.0 to enhance the teaching and learning experience in the ESL classroom. Revista Educação, Cultura e Sociedade, 5(2), 1895. http://sinop.unemat.br/projetos/revista/index.php/educacao/article/view/1895

Gamble, C., Yoshida, K., Aliponga, J., Ando, S., Koshiyama, Y., & Wilkins, M. (2012). Examining learner autonomy dimensions: Students' perceptions of their responsibility and ability. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED536981

Guaqueta, C. A., & Castro-Garces, A. Y. (2018). The use of language learning apps as a didactic tool for EFL vocabulary building. English Language Teaching, 11(2), 61-71. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v11n2p61 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v11n2p61

Hancock, D. R., & Algozzine, B. (2017). Doing case study research: A practical guide for beginning researchers. Teachers College Press.

Harrison, H., Birks, M., Franklin, R., & Mills, J. (2017). Case study research: Foundations and methodological orientations. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), 2655. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2655

Herrera, L. J. P. (2018). Action Research as a Tool for Professional Development in the K-12 ELT Classroom. TESL Canada Journal, 35(2), 128-139. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v35i2.1293 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v35i2.1293

Jalaluddin, M. (2016). Using YouTube to enhance speaking skills in ESL classrooms. English for Specific Purposes World, 17(50), 1-9. http://www.philologician.com/Articles_50/Mohammad_Jalaluddin.pdf

Khotimah, K., Widiati, U., Mustofa, M., & Ubaidillah, M. F. (2019). Autonomous English learning: Teachers’ and students’ perceptions. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 9(2), 371-381. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v9i2.20234 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v9i2.20234

Kormos, J., & Csizer, K. (2014). The interaction of motivation, self‐regulatory strategies, and autonomous learning behavior in different learner groups. TESOL Quarterly, 48(2), 275-299. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.129 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.129

Liu, X. (2014). Students' perceptions of autonomous out-of-class learning through the use of computers. English Language Teaching, 7(4), 74-82. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n4p74 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n4p74

Hernández, M. A., Cuevas, J. A., & Ramírez, A. (2018). TED Talks as an ICT tool to promote communicative skills in EFL students. English Language Teaching, 11(12), 106-115. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v11n12p106 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v11n12p106

Mathers, N. J., Fox, N. J., & Hunn, A. (1998). Surveys and questionnaires (pp. 1-50). NHS Executive, Trent, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nick-Fox/publication/270684903_Surveys_and_Questionnaires/links/5b38a877aca2720785fe0620/Surveys-and-Questionnaires.pdf

Masouleh, N. S., & Jooneghani, R. B. (2012). Autonomous learning: A teacher-less learning. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 55, 835-842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.570 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.570

McIntosh, M. J., & Morse, J. M. (2015). Situating and constructing diversity in semi-structured interviews. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 2333393615597674. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393615597674 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393615597674

Melo, E., Llopis, J., Gascó, J., & González, R. (2020). Integration of ICT into the higher education process: The case of Colombia. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 30(1), 58-67. http://rua.ua.es/dspace/handle/10045/103531

McDougald, J. S. (2009). The use of ICT (Information, Communication and Technology) in the EFL Classroom as a teaching tool to promote L2 (English) among non-native pre-service English teachers [Master’s thesis, Universidad de Jaén]. https://asian-efl-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/mgm/downloads/92352100.pdf

Mora, R. A., Martínez, J. D., Alzate-Pérez, L., Gómez-Yepes, R., & Zapata-Monsalve, L. M. (2012). Rethinking WebQuests in second language teacher education: The case of one Colombian university. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/S20449968(2012)000006A013/full/html DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/S2044-9968(2012)000006A013

Nejati, E., Jahangiri, A., & Salehi, M. R. (2018). The effect of using computer-assisted language learning (CALL) on Iranian EFL learners' vocabulary learning: An experimental study. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 13(2), 351-362. https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v13i2.752 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v13i2.752

Noriega, H. S. (2016). Mobile learning to improve writing in ESL teaching. Teflin Journal, 27(2), 182-202. https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v27i1/182-202 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v27i1/182-202

Nunan, D. (2003). Nine steps to learner autonomy. Symposium, 2003, 193-204. http://www.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.84007.1333707257!/menu/standard/file/2003_11_Nunan_eng.pdf.

Ramírez, A. (2015). Fostering autonomy through syllabus design: A step-by-step guide for success. HOW Journal, 22(2), 114-134. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.22.2.137 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.22.2.137

Rojas, Y. A. (2018). An ICT tool in a rural school: A drawback for language students at school? Enletawa Journal, 11(1), 91-109. https://doi.org/10.19053/2011835X.8977 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19053/2011835X.8977

Shakarami, A., Hajhashemi, K., & Caltabiano, N. (2016). Digital Discourse Markers in an ESL Learning Setting: The Case of Socialisation Forums. International Journal of Instruction, 9(2), 167-182. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2016.9212a DOI: https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2016.9212a

Stanchevici, D., & Siczek, M. (2019). Performance, interaction, and satisfaction of graduate EAP students in a face-to-face and an online class: A comparative analysis. TESL Canada Journal, 36(3), 132-153. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v36i3.1324 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v36i3.1324

Van Loi, N. (2017). Promoting learner autonomy: Lesson from using project work as a supplement in English skills courses. Can Tho University Journal of Science, 7, 118-125. https://doi.org/10.22144/ctu.jen.2017.057 DOI: https://doi.org/10.22144/ctu.jen.2017.057

Wang, Y. H., & Liao, H. C. (2017). Learning performance enhancement using computer-assisted language learning by collaborative learning groups. Symmetry, 9(8), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9080141 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9080141

Yin, R. K. (2012). Case study methods. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 141–155). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-009 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-009

Yuliani, Y., & Lengkanawati, N. S. (2017). Project-based learning in promoting learner autonomy in an EFL classroom. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 285-293. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v7i2.8131 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v7i2.8131

Xie, K., & Ke, F. (2011). The role of students' motivation in peer‐moderated asynchronous online discussions. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(6), 916-930. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01140.x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01140.x

Zaidi, A., Awaludin, F. A., Karim, Rdia. A., Ghani, N. F., Rani, M. S. A., & Ibrahim, N. (2018). University students’ perceptions of YouTube usage in (ESL) classrooms. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(1), 541-553. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i1/3826 DOI: https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i1/3826

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 1 de diciembre de 2021; Aceptado: 7 de marzo de 2022

Abstract

This study explores the way in which video sharing and online discussions foster learning autonomy in English language classes at a public university during the lockdown established by the Colombian government because of the coronavirus pandemic. This study was conducted with 127 engineering and administration undergraduates from a public university in the department of Boyacá. It was a qualitative case study that aimed to identify the extent to which video sharing and online discussions increase learner’s autonomous behaviors in English language learning. The instruments for data collection were student journals and artifacts such as video recordings and online discussions, interviews, and questionnaires. An open coding analysis was performed, and the results revealed that the degrees of autonomous behaviors could be gradually fostered by the implementation of video sharing. The results also indicated that students are receptive to online writing discussions, and showed how motivation plays a vital role in learning English and the achievement of the learning goals set by the students themselves.

Keywords

autonomous language learning, computer-assisted language learning, coronavirus pandemic, online discussions, video sharing.Resumen

Este estudio explora cómo el intercambio de videos y las discusiones en línea promueven la autonomía de aprendizaje en las clases de inglés en una universidad pública durante la cuarentena establecida por el gobierno colombiano a causa de la pandemia del coronavirus. Este estudio se realizó con 127 estudiantes de ingeniería y administración de una universidad pública del departamento de Boyacá. Fue un estudio de caso cualitativo que pretendía identificar hasta qué punto el intercambio de videos y las discusiones en línea aumentan los comportamientos de autonomía del alumno en el aprendizaje del idioma inglés. Los instrumentos para la recopilación de datos fueron diarios de estudiante y artefactos como grabaciones de video y discusiones, entrevistas y cuestionarios en línea. Se utilizó un análisis de codificación abierta, y los resultados revelaron que los grados de comportamiento autónomos pudieron promoverse gradualmente mediante la implementación del intercambio de videos. Los resultados también indicaron que los estudiantes son receptivos a las discusiones de escritura en línea y mostraron cómo la motivación juega un papel vital en el aprendizaje del inglés y el logro de las metas de aprendizaje establecidas por los mismos estudiantes.

Palabras clave

aprendizaje autónomo de idiomas, aprendizaje de idiomas asistido por computadora, pandemia de coronavirus, discusiones en línea, intercambio de videos.Introduction

Online education has gained wider recognition as a result of globalization in Colombia and ICT development in the educational context. Currently, many people have the possibility to access this kind of education, which adds to its multiple benefits and the conveniences of studying at home. Due to the global and public health issues originated at the end of 2019, people had to stay at home, and, in terms of education, this meant that schools and universities were closed. In light of the above, the Ministry of Education (MEN), including the local secretaries of education, called for teachers to provide students with online teaching and learning experiences.

Clearly, the mandatory lockdown forced university teachers to implement e-learning, autonomous learning, and self-directed learning in order to keep students enrolled in academic activities, as a fundamental part of their right to receive an education. Nonetheless, in the process of providing online education during the quarantine, many issues emerged. In the context of this study, the lack of technological devices and connectivity, the deficient training in online teaching (with regard to didactic and evaluation processes), and the socioeconomic conditions of rural students were some of the problems evidenced both locally and nationally.

Teachers and students started to participate in virtual lessons with limited technological resources, internet access, and knowledge about virtual education. Thus, administrators decided to train teachers, provide students with technological equipment, re-design the platforms hosted by the universities in order to guarantee the quality of higher education through digital content instruction, and to plan effective technological tools so students could achieve their learning goals. That decision also affected the English language learning process within Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC) and, after many discussions, language teachers also had to make adjustments to their English language courses. Thus, the need to keep working online was the inspiration for conducting this research study.

As English language teachers and researchers, we decided to use autonomous learning environments to maintain English language learning during the lockdown. Autonomous learning is widely used for educational purposes due to the multiple benefits of its implementation. According to Ramírez (2015) , “learner autonomy is relevant in the field of applied linguistics, not only because autonomy allows the learner to take the lead of his/her learning process, but also because it empowers him/her to be an independent user of the language” (p. 115). This means that students play an active role not only in what they learn, but also in establishing their own learning goals and how they will accomplish them. Autonomy also makes students’ performance more reflective and critical towards what is happening around them, building special abilities to interact worldwide.

The idea behind the project was to foster English language learning through the design of autonomous environments based on computerassisted language learning (CALL). Nejati et al. (2018) stated that CALL “provides learners with easy access to learning environments regardless of place and time and increases motivation and effectiveness of learning with multimedia content” (p. 352). On the one hand, students had received traditional face to face classes for a long time, and, on the other hand, they were forced to start participating in computer-assisted learning activities from one week to another as consequence of the coronavirus pandemic.

Considering the above, the major challenge for English language teachers was to design online courses while maintaining the quality standards of higher education. McDougald (2009) claims that “by taking advantage of a Virtual reality, CALL has the potential to move education from its mere reliance on books to experiential learning in naturalistic settings” (p. 21). Learning takes place where learners are motivated to learn and teachers are prepared to teach. For that reason, this study intended to contribute to the improvement of English language learning at the university level and the way in which the design of online English language courses could be fostered for students who are willing to participate in virtual education. The research questions of this study are as follows:

• To what extent do video sharing and online discussions increase learner autonomous behaviors in English language learning during the coronavirus pandemic?

• What are learners’ preferences (activities/ tasks) when integrating ICTs into an English autonomous learning course?

This study was based on 127 undergraduate students from a public university in Colombia. Despite the inconveniences that arose at the beginning of the technology-assisted course. (connectivity, lack of technological resources, low digital skills, and students’ habits with respect to studying at home) students started the course actively. Qualitative results from field notes, semistructured interviews, surveys, students’ online discussions and video sharing revealed that ICTs are a positive complement to traditional teaching, especially when developing speaking skills through online discussions and critical thinking by means of video blogs in English.

Theoretical framework

Autonomous language learning

Being able to set learning objectives and achieve them is the main characteristic of active students who are motivated to learn anything and take responsibility for their performance. Nevertheless, this pandemic made teachers and learners rethink the way in which traditional education has been conceived in the last decades. Therefore, during this crisis, the concept of autonomy started to be regarded as a key factor in achieving learning goals. Bedoya (2014) reported that autonomy is essential when learning in virtual education because students are highly motivated when working with computers. He also stated that “it is necessary to build a methodology where interaction, reflection, and creativity enhance the development of autonomy which, in turn, facilitates learning” (p. 96). The study established the constant need to do research, which favors student autonomy in virtual settings, where they are able to select topics, tasks, and evaluation procedures. In this vein, developing autonomous behaviors that involve CALL require students to reflect and implement cognitive and metacognitive strategies, in addition to the need for motivation and interaction among the participants.

In the literature, autonomy contributes to the improvement of lifelong learning skills and the implementations of a set of pedagogical procedures that enhance those particular educational goals. In other words, the role of the teacher is crucial when designing autonomous and technology-assisted courses. According to Lowes and Target (1999, as cited in Bajramia 2015 ),

in an autonomous classroom, teachers do not play the role of imparters of information or sources of facts. Their role is more that of a facilitator. The teacher’s position is to manage the activities in the classroom and help learners plan their learning both for long and short term. The teacher has to be able to establish a close collaboration with the learners and make sure that all learners know what is expected of them at all times. (p. 426)

Being a facilitator could be challenging for teachers at the beginning of the process. Teachers should help learners develop self-regulation strategies and encourage students to assume their responsibility in controlling their learning process. A clear example is stated by Al Asmari (2013) , who explains that teachers should help learners identify the strategies that they could use to foster their learning. Accordingly, the role of a teacher is facilitating learning and considering students’ interests, needs, and individual learning styles in order to enhance social, affective, and critical reflection processes, which are a key component in the development of autonomous behaviors such as planning, monitoring, and evaluating one’s own learning.

Online learning environments allow students to control their learning behaviors and assume their responsibilities in a better way, i.e., the use of innovative digital strategies helps students plan, schedule, monitor, and self-evaluate their learning process.

Furthermore, the implementation of autonomy in English language learning requires certain degrees of responsibility. This means that students should make decisions regarding their process, instead of having the teachers decide for them. Díaz-Ramírez (2014) argues that “autonomy aimed at encouraging the gradual development of responsibility considering their level of proficiency, abilities, styles, preferences, and participation in the communities” (p. 57). Expecting learners to develop learning responsibility and autonomy requires language teachers’ expertise in selecting the most appropriate materials and activities to create suitable autonomous and authentic learning experiences, such as interacting with real people, reading online engineering magazines, writing papers based on real situations, listening to daily news, etc.

Khotimah et al. (2019) suggest some steps such as the initiating process, setting goals, planning activities, and monitoring, which involves the use of learning strategies and materials where interacting and collaborating with others are crucial opportunities for learning. With this in mind, teachers should establish interactive courses that allow students to have a correctly develop autonomy skills. Practically speaking, these steps are the pedagogical guide for successful autonomous learning.

Finally, the incorporation of autonomy in online English learning highlights the importance of learners in their educational processes, i.e., learners become the focus of this kind of education. Learners should know themselves, their needs, and their interest in developing autonomous behaviors and other aspects such as confidence, motivation, and collaborative support as, well as in enhancing their learning abilities in order to become more productive learners.

Computer-assisted language learning (CALL)

On account of the pandemic, many language teachers and people in general developed an interest in the incorporation of technology into English language teaching and learning processes. In addition to what is stated in the specialized literature, the benefits of incorporating technology into English teaching are evident. For the purposes of this study, CALL is considered to be the teaching and learning approach in which the incorporation of technological tools is used for language learning. When CALL is used in the field of ESL (English as a second language), the Web 2.0 appears as the best alternative to motivate students and interact on the Internet. Web 2.0 and beyond could be blogs, wikis, networking sites, video blogging, etc. Flores (2015) stated that, “in order to accomplish success in the classroom, the ESL learner needs to be motivated and the integration of the Web 2.0 in the classroom setting offers this opportunity. One example is the use of blogging in the ESL classroom” (p. 111). He also argued that “plenty of educators use blogs in the ESL classroom as journals or diaries to promote critical thinking and process writing” (p. 111). The use of computers, Web 2.0 tools, or other digital platforms has proven to offer a variety of opportunities for learners because it appears as an innovative and creative way to foster not only academic skills such as listening, reading, writing, or speaking, but also collaborative skills, which are paramount to complementing students’ professional growth.

Wang and Liao (2017) established that “the creation of CALL innovative collaborative learning alongside class instruction that explicitly reflects how innovative collaborative learning clusters can optimally facilitate learning through teaching” (p. 15). With this contribution in mind, all the activities that teachers conduct while using technology must be guided by pedagogical decisions. For instance, if a teacher decides that students use a certain application to make a video to present in class, that decision should be based on pedagogical representations, as well as on the integration of technology into the syllabus design. Then, the selection of materials is a paramount factor of this kind of learning because all choices made should guarantee that learners acquire better language proficiency.

Considering the importance of the authentic materials that teachers should use in autonomous learning through computer-assisted environments, it is necessary to clarify the relationship that must exist between materials and pedagogical decisions. This study contemplated the following conceptions. First, authentic materials are conceived as those that reflect the reality of the context of the participants. This includes daily newspapers or magazines, online forums or discussions, video calls, etc. Second, the topics are also considered to be significant within learning experiences in order for students to expand their learning, not only with regard to content, but also including other areas such as critical thinking based on reading and writing. In order to achieve a balance between the pedagogical decisions that teachers make and the selection of materials to favor learning, it is imperative to design a clear guideline atmosphere where students understand the instructions without the need for teachers to explain them. Besides, there are many ways to receive feedback and assessment in online learning, not only by the teachers, but also by classmates. This study aims to enrich this area as well as to contribute to broadening our understanding in terms of fostering students’ autonomous behaviors in the implementation of a CALL English course.

Online discussions

Advances in technology have enhanced communication over long distances or during global emergencies such as the coronavirus pandemic. Language teachers are required to interact with learners in asynchronous ways as a vital complement of English language learning process at UPTC. In online discussions, students foster their social interactions, thus contributing to enhancing language acquisition processes. For the purposes of this study, the main goal of online discussions was to build a learning environment where students were motivated to engage in positive, active social interactions despite the global circumstances.

The first element to incorporate online discussions into an English language technologyassisted course is the engagement of students in productive outcomes. This means that online participation through forums, debates, or blogs should be managed in spontaneous and formal settings in order to see how students react. The second element is the number of messages, forums, or papers that students should read and report on. If students are involved in an overwhelming number of activities, their motivation and interaction will be reduced. The final component is related to the kind of activities learners are involved in. These activities should be oriented towards the construction of content knowledge through authentic material, with help from collaborative activities that foster soft skills such as leadership, teamwork, problem solving, adaptability, and ethics. Xie and Ke (2011) concluded that “students’ social interaction and reflective activities should not be ignored or discouraged in online classes because these two types of interaction will facilitate content-related knowledge construction processes” (p. 927).

Consequently, students enrolled in online discussions should have the same feeling of social presence as in face-to-face interactions. Therefore, posting messages, replying to questions, and receiving good feedback would academically satisfy learners. Thus, language teachers are in charge of promoting and designing other alternatives for evaluation processes (blogs, forums, portfolios) that encourage cooperation between participants and the development of critical thinking skills. In the context of this study (UPTC), learners participated in forums, debates, and critical thinking synchronic discussions.

Video sharing

Providing students with alternatives to learn English during the coronavirus pandemic made teachers rethink language education inside UPTC, where traditional face-to-face classes were the norm. As mentioned above, the participants of this research study were enrolled in online discussions to foster their speaking and critical thinking skills, and video sharing was selected as the strategy for them to share their learning outcomes. This selection was also based on the premise that it promotes online learning engagement. Jalaluddin (2016) stated that

teachers can also use audio-visual material for different purposes such as for the interpretation of the spoken language, as a language model, to appreciate the cultural issues, as a stimulus or input for further activities, or as a moving picture book. Videos provide access to things, places, people’s behavior, and events. (p. 2)

In addition, video sharing is also considered to be one of the most significant changes in today’s language education because it brings reality to language learning processes. For example, Zaidi et al . (2018) concluded that “students were using YouTube at a high rate. They found that YouTube was easy and convenient to use and they used it to assist them in their studies and learning English” (p. 550).

A student’s motivation to share their thoughts or points of view through video sharing constitutes an opportunity to promote support, collaboration, and constructive feedback. Videos also aid students in developing creativity, interactive participation, and reducing their anxiety to talk. Another challenging area in promoting effective language acquisition and a visible improvement of other abilities using technological environments lies in the opportunities that students have for social interaction. Benevenuto et al . (2010) claimed that the “Web 2.0 among other environments allows several kinds of interactions between users and videos, such as friendship relations, video evaluation and publication of comments” (p. 115). Therefore, the combination of assessment procedures, evaluation from others, and in-depth feedback from the language teacher can guide the student to make more effective, organized, and better-quality assignments. Therefore, they would not make the same pronunciation mistakes in the last videos, and their performance at editing and presenting innovative and authentic activities would be gradually seen. Thus, encouraging responsibility, organization, self-reflection, and collaboration, among other autonomous behaviors, may enhance students’ learning processes.

At UPTC, producing authentic, creative, and digital material was a motivating factor for students to enhance their English language learning processes because they witnessed the way in which they could generate new ideas. Video sharing gave equal opportunities to all members to interact and participate, and the flexibility of making the videos enhanced specific learning styles or talents. These characteristics made students interact positively towards online education while they were at home because of the coronavirus pandemic.

ICTs in Colombian language learning

Autonomy and the incorporation of CALL tools, as is the case of online discussions and video sharing, has been widely researched around the world. In Colombia, some studies have been carried out, namely those by Alpala and Flórez (2011), Mora et al. (2012), Noriega (2016), Guaqueta and Castro-Garces (2018), Hernández et al. (2018), and Rojas (2018) . These studies demonstrate a variety of different ways in which researchers have used apps or digital environments such as Duolingo and Kahoot, TED talks, the use of Web Quests, and other technological practices that can be employed to effectively foster vocabulary building, as well as to practice listening, writing, speaking, and reading. Here, the strengthening of technological skills becomes part of today’s abilities. The most significant contributions made by the aforementioned works are the improvement of policies in order to allow students to have the same quality of education, especially in the use of technological devices; the use of apps in English language learning as effective tools to promote motivation; and the significance of varied topics in the form of authentic and creative material.

However, one of the possible negative aspects that can be encountered within digital learning is the lack of digital teaching practices. Melo (2020) argued that “it also becomes relevant to design and provide permanent, ongoing training in ICTs and their implementation in the educational context” (p. 63).

Methodology

Type of research

This study followed a qualitative paradigm in the form of a case study. Harrison et al. (2017) argue that “case study research is consistently described as a versatile form of qualitative inquiry most suitable for a comprehensive, holistic, and in-depth investigation of a complex issue (phenomena, event, situation, organization, program individual or group) in context” (p. 28).

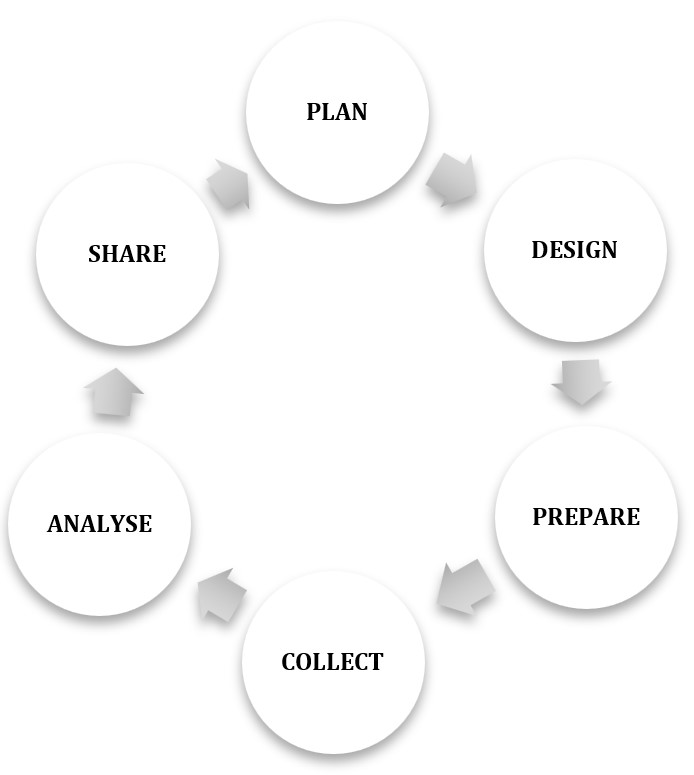

Regarding the case study research cycle, in order to fulfill the objectives of this study, we established six stages based on Yin’s contribution (2012), as shown in Figure 1 . The first stage is planning, which is related to the research question and analyzing the problem under study. In this stage, the enhancement of higher education within UPTC was the main premise, hence the idea of promoting autonomy in the field of English language learning during the Covid-19 lockdown.

The second and third stage, designing and preparing, focused on defining the research method, the data collection procedures, and the pedagogical intervention techniques. We spent around two months preparing the pedagogical component of the technology-assisted English language course, and, also during this period, we designed the instruments to be implemented during the interventions.

The collecting stage was full of inconveniences at the beginning. A number of students did not have the technological equipment, namely an Internet connection and a computer. Others got used to doing nothing because of the extended lockdown. These students remained at home and did not receive any education for three months. Finally, English classes based on autonomous learning environments started in June. During that time, the students participated in eight online sessions, where they engaged in online discussions such as forums.

They also shared eight videos where they talked about various aspects from a critical perspective. Participants engaged in these activities for two months.

The analyzing phase was characterized by the triangulation of data, which, according to Herrera (2018) , “offers the opportunity to identify the weaknesses of each single source while compensating them with the strengths of another. An example of triangulation would be to collect data through a survey, observations, and field notes to later analyze” (p. 132).

Based on that, this study employed student journals and artifacts, including video recordings and online discussions, interviews, and questionnaires. Open coding analysis was also performed, where common information was categorized in sub- and main components in order to obtain the results of this research study.

Finally, the sharing stage focused on showing the main findings with regard to improving online learning environments in order to enhance distance education at UPTC.

Figure 1: Research cycle

Data collection instruments

The data sources used for collection and analysis from the eight online sessions were as follows: online discussions through asynchronous forums, an open-ended questionnaire, an online survey conducted with students, and the journals of an asynchronous journal tool called My video sharing experience, which was implemented at the end of each session.

Student artifact. This study collected students’ written and oral artifacts. The written production consisted of journal and forum entries. The oral production comprised the video sharing experience of the enrolled students enrolled. These artifacts were vital because students could evidence their autonomous decisions and their point of view on sociopolitical issues.

Students wrote their class experience once a week and shared their points of view on a few sociopolitical issues by means of videos. In the forums, they shared what they learned in each session, the difficulties they encountered, and their improvements regarding language use. This study adopts the concept of forum proposed by Shakarami et al . (2016), who stated that forums allow for a collaborative and cooperative learning space where students interact and develop relationships with others. Students also commented about the weekly topics addressed in the online sessions. The idea of commenting on the videos was to involve students in peer assessment.

Semi-structured interviews (SSI). Two interviews were applied at the middle and at end of the study in order to answer the research question. These interviews were conducted via Google Meet. McIntosh and Morse (2015) stated that “the purpose of SSIs is to ascertain participants’ perspectives regarding an experience pertaining to the research topic” (p. 1). Therefore, this instrument was suitable because students could answer the interviews online and right after class.

Questionnaires. Two questionnaires were applied at the beginning and at the end of the semester. As stated by Mathers et al. (1998) “questionnaires are a very convenient way of collecting useful comparable data from a large number of individuals” (p. 21). These questionnaires were expected to provide information about learners’ opinions regarding motivation, responsibility, autonomy, cooperative work, and their learning styles.

Participants

As mentioned above, this study was conducted at UPTC. At the beginning of the technology-assisted English language course, we had 150 students, but only 127 participated in all the suggested activities. The population of this study consisted of 69 women and 58 men whose ages ranged between 19 and 28 years old. These students attended undergraduate programs from UPTC Sogamoso campus, namely from Geological, Systems, Industrial, Mining, and Electronic Engineering, as well as Business Administration, Public Accounting and Finance, and International Trade.

Pedagogical intervention

The intervention consisted of the written analysis and oral reflections of eight sociopolitical issues, as shown in Table 1 . Each week, the students wrote reflective papers and uploaded critical videos based on the analysis of common global issues. They also commented on their classmates’ reflections and videos.

Table 1: Sociopolitical issues

WEEK

TOPIC

1

Ethics at the workplace

2

Power and politic

3

Economy and money

4

Poverty

5

Immigration

6

Terrorism

7

Crime

8

Climate change

Table 2 displays how the autonomous English language course was designed to target and integrate eight autonomous behaviors through computer-assisted language activities such as using the Moodle platform, forums, interactive journals, online discussions via Zoom or Google Meet, and YouTube video sharing, where learners became active agents of their learning process.

Likewise, Table 2 summarizes eight degrees of autonomous behaviors, which were gradually implemented due to the fact that, at the beginning of the course, the learners were not found to be autonomous as per the first questionnaire and interview (see the Discussion section). Instead, we gradually fostered these behaviors. These degrees of learner autonomy were adapted from the work by Nunan (2003) , so the learners started by understanding the main objectives of the course and what they were expected to produce at the end. Then, they were guided to modify specific goals and content related to the sociopolitical issues to be discussed. In the next step, they were stimulated to participate in additional activities in order to practice their writing and speaking. Then, the learners adapted and carried out some tasks based on their interests. Afterwards, they made a responsible selection of activities in order to accomplish specific goals. Finally, they created their own writing and speaking material to be shared with the class, so that they could assess each other and formulate possible research topics.

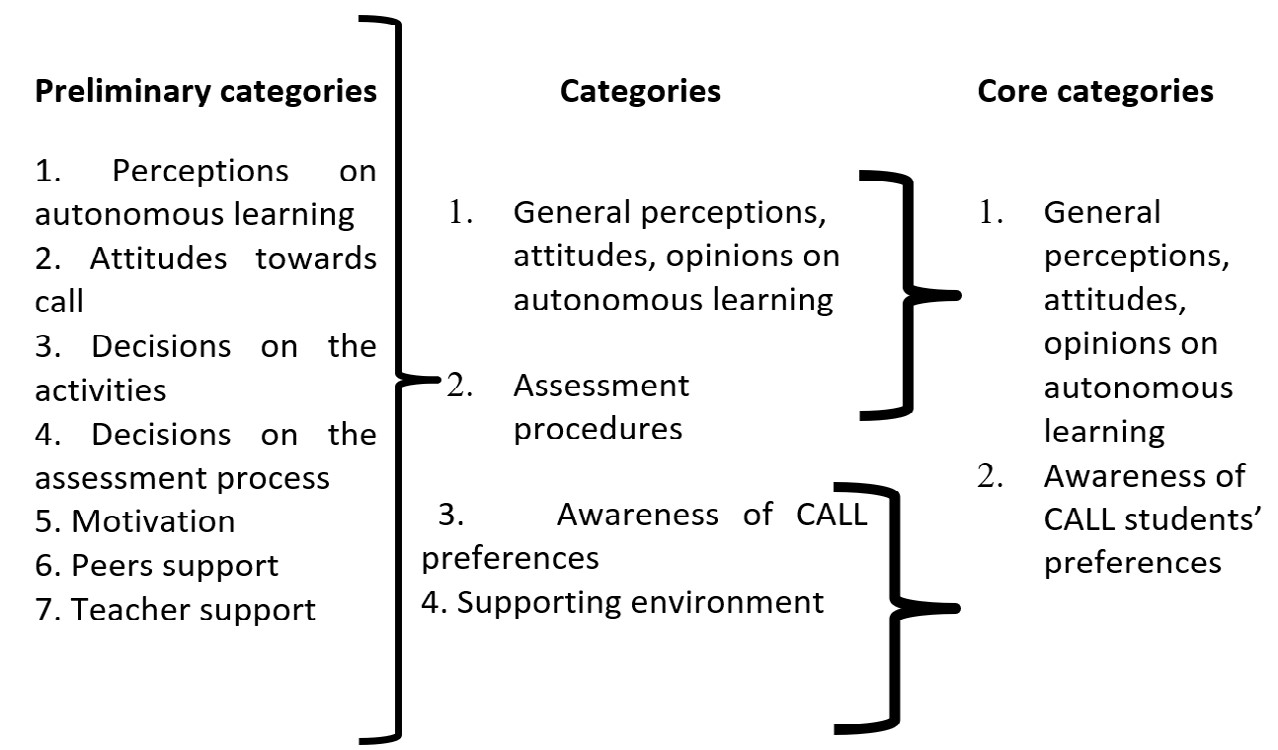

Data analysis

The collected qualitative data were organized in charts for ease of management. All participants’ responses were also anonymized. Qualitative data were triangulated. The data collected through student artifacts (video sharing and online discussions), SSIs, and questionnaires were analyzed via open coding, from which four categories emerged and produced two core categories (see Figure 2 ). According to Blair (2016) , “open coding was identified as a method of generating a participant-generated ‘theory’ from the data and template coding was identified as a tool for framing data into a coherent construct through the application of an established ‘language’” (p. 17).

General perceptions, attitudes, opinions on autonomous learning

To examine the extent to which the use of online discussions and video sharing experiences fostered autonomous language learning among undergraduate students during the coronavirus pandemic, we administered an initial questionnaire to see how autonomous behaviors were evidenced. The findings showed that 70% of the students did not have any experience with online learning activities.

Table 2: Degrees of learner autonomy

Week

Degrees of learner autonomy

Process

1

Learners’ decision-making about the content and processes involved in their learning process

Learners are aware of the course content and goals

2

Involving learners in modifying course content

Learners are able to modify or to adapt goals and content

3

Encouraging students to think about activating the use of English in extracurricular activities

Learners participate in additional autonomous activities

4

Raising learner awareness of the strategies underlying classroom tasks

Learners create their own tasks

5

Helping learners identify their own preferred styles and strategies

Learners go beyond the classroom and make associations between the classroom content and the real world

6

Learners’ selection of the order in which certain activities were to be carried out

Learners make choices from a range of options

7

Learners’ development of their own materials

Learners create their own writing and speaking materials

8

Peer assessment and socialization of the results

Learners become teachers and researchers

Figure 2: Development of the core category

The remaining 30% had had the opportunity to study virtual courses offered by SENA, an official institution attached to the Colombian Ministry of Labor that offers free training to millions of Colombians who benefit from technical, technological, and complementary programs that focus on the country’s economic, technological, and social development.

An initial autonomous questionnaire was designed and adapted according to Nunan’s nine degrees of learner autonomy (2003) (see Table 2 ). When students were asked about autonomous behaviors such as goal setting, planning, learning styles, initiative to start something new, determination when accomplishing certain responsibilities or activities based on their interest, and time management, the results revealed that 107 out of 127 students did not establish their own academic and personal goals. They usually started something new and did not finish it due to a lack of time. 60% of the participants have a clear idea about their strengths and weaknesses regarding both their academic and personal lives.

95% of the students did not plan their academic objectives. With these results, it can be inferred that students need time and practice to adapt in order to set their own goals. At the end of the implementation of the instruction, the same questionnaire was administered. The results showed that 75% of the students enjoyed making decisions about the content of the suggested activities. This agrees with Van Loi (2017) , who found that student autonomy slightly increased after two semesters of intervention in this regard, as well as with Yuliani and Lengkanawati (2017), who concluded that “learner autonomy needs process, and the process shows irregular pattern” (p. 292).

During the implementation of the technologyassisted course, the students started participating more actively; they made comments on their perceptions of the autonomous learning environments. One student said, during an online interview:

I like selecting the activity I like to do the most from a variety of proposals because I love drawing and making cartoons allows me to let people know what I understand in relation to political issues. (I, S6)

Based on the comment above, it can be said that promoting students’ own learning decisions is vital for them to become autonomous. The previous excerpt is in line with the results of a study conducted by Dang (2012) , which indicated that

undergraduate students who were required to explicitly set out weekly learning goals during a five-week Japanese course could personalize their learning process more easily than others. They even adopted goals that were challenging and beyond the course requirement but interesting to them. This illustrates a positive relationship between cognitive awareness and learning behavior. (p. 58)

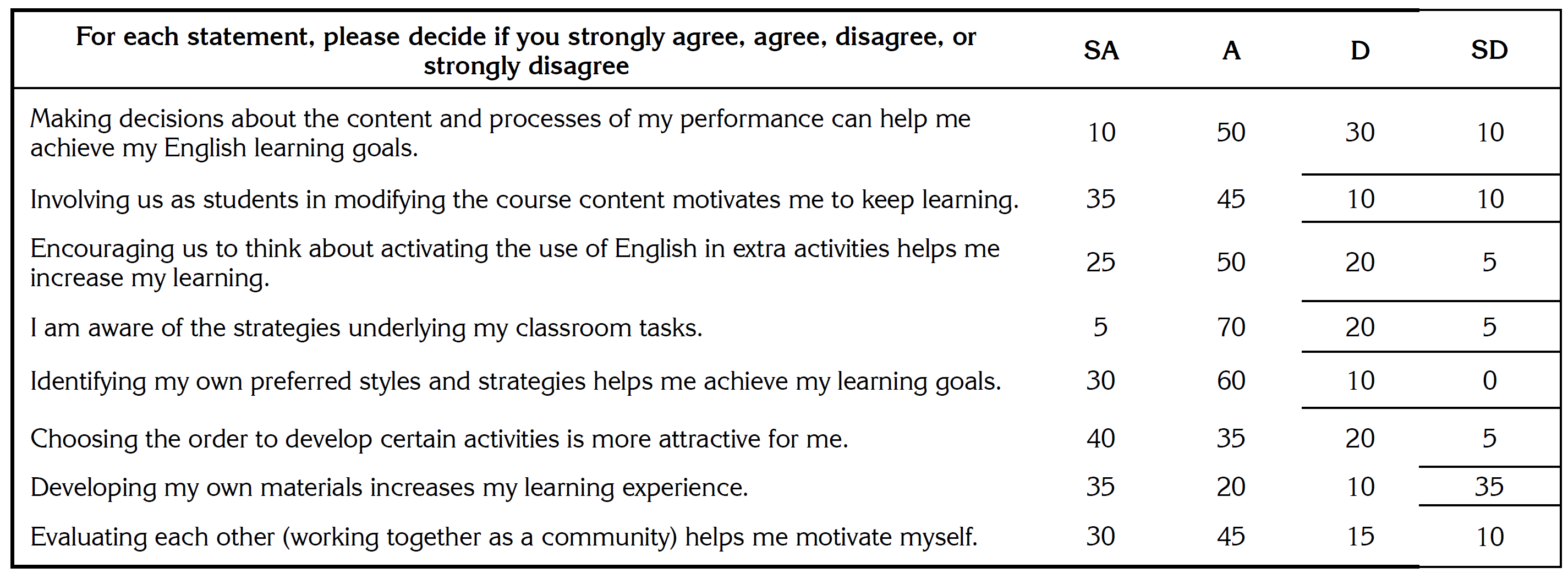

Finally, the perception of responsibility also appeared to demonstrate autonomous behaviors. According to Gamble et al. (2012) “in order for learners to develop a sense of responsibility, they need encouragement from teachers to realize that success in learning is the responsibility of both the teacher and student” (p. 268). Figure 3 shows the perceptions towards the autonomous behaviors that students had at the end of the process.

When analyzing the data from the students’ journals, it was found that 95% of the participants enjoyed writing right after the class finished. A student commented:

I like participating on the forums. At the beginning it was very difficult because I had never done that before in my English classes, I like to write as soon the classes finish. I also like to write about other contents (what really happens in the world) instead of working on grammar as we did before this virus and if I compare the first entry with the last one, I can be sure I improved a lot. (J, S3)

Lastly, when the final interview was administered, 56% of the participants strongly agreed that they learned how to plan their daily activities, not only those related to the English language courses, but also for other subjects. For example, a student said:

I learnt to plan what I had to do every day. Doing the videos was fun so I decided to do it on the weekends. (I, S8)

Another participant said:

I liked this method of English because I can decide the activities, I need to improve but I need the guidance of the teacher. (I, S12)

Another argued:

I consider myself more responsible because I asked when I do not understand something, in face-to-face classes I did care if I did not understand; I also sent the activities on time. Before, I gave excuses all the time. (I, S21)

Figure 3: Final perceptions towards autonomous behaviors SA: strongly agree; A: agree; D: disagree; SD: strongly disagree

Here, two points must be highlighted. First, knowledge transfer to other real areas provides a foundation for the development of other 21st-century skills required to succeed professionally and as a person, as well as for fostering the process of building autonomy. Second, the previous excerpts agree with Farivar and Rahimi (2015), who concluded that

teachers should reconsider the language methodologies and bravely step down from the platform to the learners’ computer station. They need to give learners useful guidance for their self-directed learning, help them to develop their self-directed learning strategies, and train them to be real autonomous learners. (p. 649)

It is worth noting that students could manage the activities based on their learning styles. Even so, traditional education patterns such as teacher guidance keep appearing as a constant need for students’ academic success, as they seek to create good academic products and, in order to achieve it, they require support and guidance from the teacher.

One of the key elements of this study was in line with the conception of autonomy in language learning. This means that, first, the perception at the beginning was challenging because students were not used to this kind of methodology; second, guiding students to take control of their learning process by providing opportunities to establish goals and choose the activities they want to present is imperative when fostering autonomy; third, peer assessment and evaluation of the results during the pedagogical intervention allowed for active participation because the students felt that they were an important component for their learning achievement.

Awareness of the CALL students’ preferences

The questions about self-direction, esteem, self-worth, self-efficacy, self-direction, confidence, giving support, receiving support, openness, evaluation, and reflection evidenced the fact that students felt a lot of anxiety, stress, and discouragement because they did not know where they were going with regard to their profession and their life. Surprisingly, they were concerned about the extension of the lockdown and the need to socialize with their friends and classmates during that time. Correspondingly, when we conducted the first interview, the students were worried about the coronavirus pandemic. In addition, many of the forum’s comments were also related to annotations about the coronavirus.

This allowed us to conclude that motivation is a vital component to enhance academic performance. Kormos and Csizer (2014) argued that “motivational factors and self-regulation strategies affect autonomous learning behavior” (p. 290). Even though the students were ready to study online, their level of motivation was low because they were easily influenced by external issues. Liu (2014) stated that “motivation is an important issue that influences the extent to which learners are ready to learn autonomously” (p. 74), i.e., academic performance is optimized by incorporating planning, and management.

Another student inferred:

For me, it was important to have the evaluation from the teacher because I learnt to organize what I was going to videotape, it was like a challenge. I also learnt from my classmate’s comments because I did not appear in the first video, I just read my slides, so watching what my friends told guided my learning process. (I, S7)

Another student wrote:

Thanks to the videos I was able to participate in class, in face-to-face classes I never talked because I was shamed because of my pronunciation. (I, S11)

By analyzing these statements, it is clear that students showed a positive perspective regarding the way this autonomous, technology-assisted course evaluated their performance, which included comments and feedback from their classmates. This was similar to the findings of Masouleh and Jooneghani (2012), who stated that “self-reports can be a means of raising awareness of learners’ strategies and the need for constant evaluation of techniques, goals, and outcomes” (p. 840).

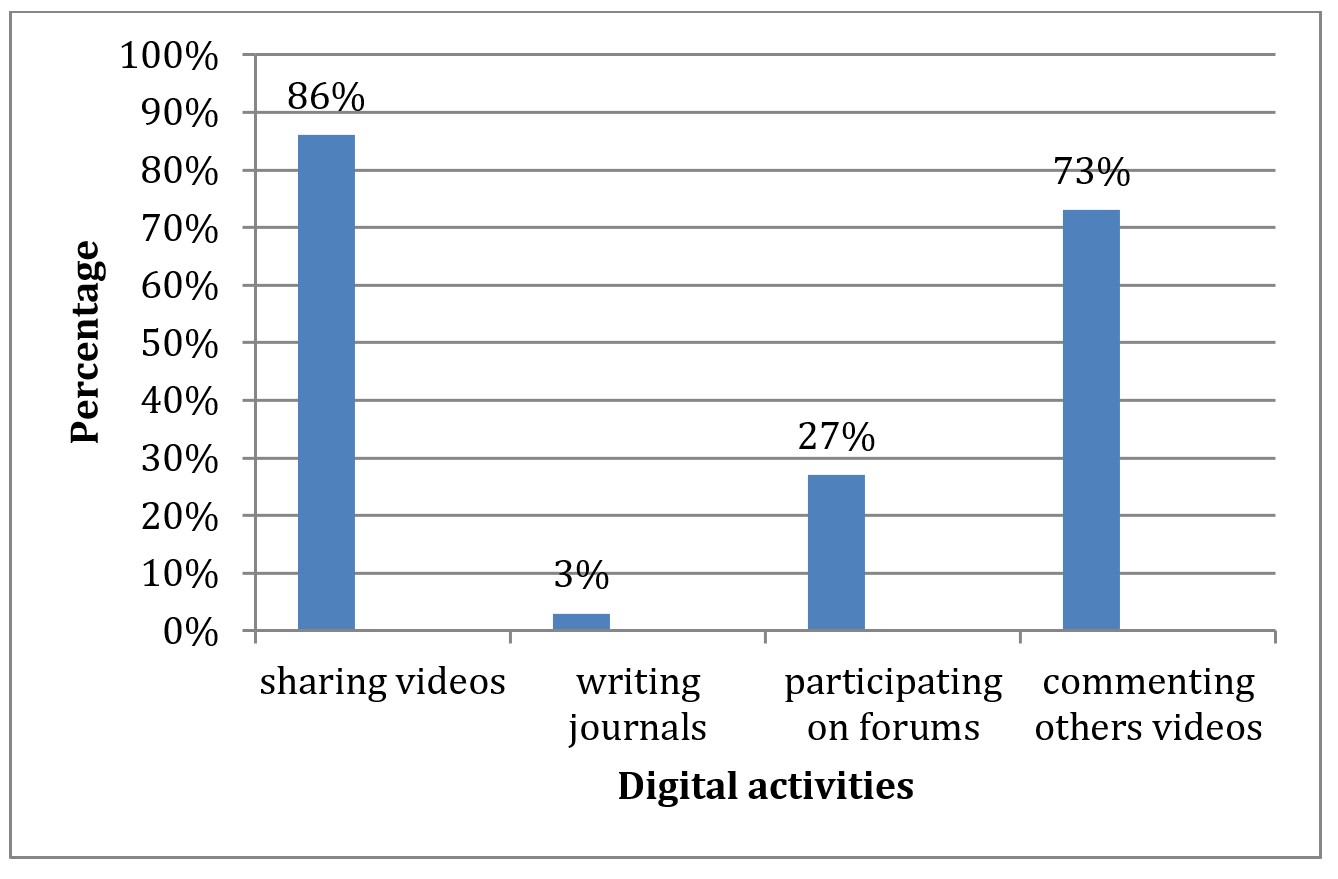

Based on the results obtained, the students were more motivated to make videos and comment on the others’ participations rather than writing the journal entries, which is due to the amount of writing activities they had, not only for their English course, but also for other subjects during the semester. The results of a questionnaire implemented in the middle of the course show that more than 86% of the students felt that making and sharing videos reduced their stress. Only 3% of them enjoyed writing. Figure 4 below shows the percentage of the activities that the students enjoyed the most and the least, as well as those that were useful to reduce stress:

Among the factors we encountered while analyzing the data, especially during the interviews, we found that students expressed feeling of accumulation of stress as a consequence of the number of workshops, activities, and writing projects assigned during the online semester. In that sense, motivation, assessment procedures and writing criteria appeared as the elements that affected writing participation during the implementation of the course. It is worth highlighting that attention should be paid to motivation and feedback procedures when designing and monitoring students’ writing performance. The development of strategies to enhance students’ writing skills must be deployed in class in order to promote intrinsic motivation among students.

Other important aspects that appeared to interfere with the process of writing were the lack of expertise in certain topics; a number of students said that they did not know what to write. One student wrote on a forum:

I liked the topic of critical thinking, but sometimes I do not know anything, for example, about how conflict started in our country, I prefer saying my point of view about the current situation as racism in the USA. (F, S6)

By analyzing this statement, it is clear that the students showed their interest in writing. However, higher education is not only about ensuring access to scientific knowledge related to the students’ majors, but also about developing the necessary skills for critical thinking and interpretation on political, ethical, and other complex national issues, which is an opportunity to improve writing skills. According to Stanchevici and Siczek (2019), a number of students commented on interaction with their peers and instructor as a valuable element of the class. We attribute this to the extent to which the instructor thoughtfully embedded interactive elements into the classes and made certain that students had multiple and diverse opportunities to interact via online discussion and VoiceThread postings. (p. 147)

Stanchevici’s project is consistent with the results of this project because, during the course, we, as the guiding teachers, had to incorporate technology-assisted activities such as gaming in order to encourage more interaction.

Figure 4: Percentage of student enjoyment regarding digital activities

Conclusions

This study helps to understand how students gradually became autonomous by performing CALL activities during the coronavirus pandemic, which prepared them for future online semesters. It also offers an approach to improve the strategies used by teachers to enhance writing skills, which appears to be difficult to manage and reluctantly performed by the participants. Concerning the research questions stated in this study, the findings revealed that carrying out activities involving online discussions based on video sharing highly increase students’ autonomy, since they play an active role in creating their videos and giving their own opinions. In this case, they were able to discuss about specific topics because they were the main characters of the uploaded material, and the topics were not unknown to them; the materials were created based on their interests.

Likewise, it was evidenced that learners’ preferred to make videos about sociopolitical issues instead of writing their opinions about these topics. Perhaps the times of Covid-19 in which news, information, advertisements, and other kinds of information were given mainly through videos in different social media (Tik-Tok, Youtube, Facebook live, and so on), may be the answer to why students preferred these activities.

The gradually implemented degrees of autonomous behavior helped students become aware of their learning process by making responsible decisions regarding topics and learning goals, which were found to have been accomplished by the end of the semester. Supporting participation in online discussions and including video sharing as a strategy to foster autonomy revealed that English syllabi at UPTC could be adapted, not only during these circumstances of isolation, but also to provide students with other ways of learning a second language.

It should be noted that this study was conducted with many difficulties regarding Internet access for some students. Others were frustrated because of the number of activities assigned in other subjects. The attendance during the online sessions was satisfactory. Nevertheless, the feeling of imposing online learning was always criticized. Based on the implications of this study, it is recommended that autonomous online activities be incorporated in English language courses at UPTC in normal times because it benefits the development of oral skills among ESL learners.

References

Notes

Metrics

License

Copyright (c) 2022 Marian Olaya, Willian Mora

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.