DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.156Publicado:

2009-01-01Número:

No 11, (2009)Sección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónEvaluating the appropriateness and consequences of test use

Evaluación de la conveniencia y de las consecuencias del uso de pruebas

Palabras clave:

validación de pruebas, medidas de desempeño, medidas de conocimiento de lengua (es).Palabras clave:

Test validation, proficiency measurement, language assessment (en).Descargas

Referencias

Bachman, L. F. and Palmer, S. (1996). Language testing in practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bachman, L. F. (2005). Building and Supporting a Case for Test Use. Language Assessment Quarterly, 2, 1, 1-34.

Brennan, R. L. (2006). Perspectives on the evolution and future of educational measurement. In R. L.

Brennan (Ed.), Educational Measurement (4th ed.) (pp. 1-16). CT: American Council on Education and Praeger Publishers.

Chapelle, C. A. (1999). Validity in language assessment. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 19, 254-272.

Cheng, L. (2005). Changing language teaching through language testing: A washback study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chudowsky, N. (1998, winter). Using focus groups to examine the consequential aspect of validity. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 28-38.

Cronbach, L. J. (1988). Five perspectives on validation argument. In H. Wainer & H. Braun (Eds.), Test validity (pp. 3-17). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cureton, E. E. (1951). Validity. In E. F. Lindquist (Ed.), Educational Measurement (3rd ed.), pp.621-694. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Fremer, J. (2000, December). My last (?) comment on construct validity. National council on Measurement Newsletter, 8, 4,2.

Green, J. (2000, December). Standards for validation. National Council on Measurement Newsletter, 8,4, 8.

Green, D. R. (1998, summer). Consequential aspects of the validity of achievement tests: A publisher's point of view. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 16-19.

Guion, R. M. (1980). On Trinitarian concepts of validity. Professional Psychology, 11, 385-398.

House, E. R. (1995). Putting things together coherently: Logic and justice. In D. M. Fournier (Ed.), Reasoning in evaluation: Inferential leaps and links (pp. 33-48). New Directions for Evaluation, 68.

Hulin, C. L., F. Drasgow, and C. K. Parsons. (1983). Item response theory: Application to psychological measurement. Homewood, Ill.: Dow Jones-Irwin.

Kane, M. T. (1992). An argument-based approach to validity. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 3, 527-535.

Kane, M., Crooks, T., and Cohen, A. (1999). Validating measures of performances. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 18, 2, 5-17.

Kane, M. T. (2001). Current concerns in validity. Journal of Educational Measurement, 38, 4, 319-342.

Kane, M. T. (2002). Validating high-stakes testing programs. Educational Measurement, 21, 1, 31-41.

Lado, R. (1961). Language testing: The construction and use of foreign language tests. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lane, S., and Stone, C. A. (2002, spring). Strategies for examining the consequences of assessment and accountability programs. Educational Measurement, 23-30.

Lane, S., Parke C. S., and Stone, C. A. (1998, summer). A framework for evaluating the consequences of assessment programs. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 24-27.

Linn, R. L. (1997, summer). Evaluating the validity of assessments: The consequences of use. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 14-16.

Linn, R. L. (1998, summer). Partitioning responsibility for the evaluation of the consequences of assessment programs. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 28-30.

McNamara, T., and Roever, C. (2006). Language testing: the social dimension. Oxford: Blackwell.

McNamara, T. (2006). Validity in Langauge Testing: The Challenge of Sam Messick's Legacy. Language Assessment Quarterly, 3, 1, 31-51.

Mehrens, W. A. (1997, summer). The consequences of consequential validity. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice,16-18.

Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement (3rd ed.) pp13-103. New York: Macmillian. 13-103.

Messick, S. (1995, winter). Standards of validity and the validity of standards in performance assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 5-8.

Messick, S. (1996). Validity and washback in language testing. Language Testing, 13,3,241-256.

Moss, P. A. (1995, summer). Themes and variations in validity theory. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 5-13.

Moss, P. A. (1998, summer). The role of consequences in validity theory. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 10-12.

Legislators: The General English Proficiency Test cannot be set as the graduation threshold ( ) (December 19, 2003), United New () Available at http://enews.tp.edu. tw/News/News.asp?iPage=7&UnitId=117&NewsI d=8803.

Liao, P. (2004). The effects of the GEPT on college English teaching. Available at http://home.pchome.com.tw/showbiz/posenliao/page/page_5_011.htm.

Popham, W. J. (1997, summer). Consequential validity: Right concern-wrong concept. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice,9-13.

Reckase, M. D. (1998, summer). Consequential validity from the test developer's perspective. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice.13-16

Ryan, K. (2002). Assessment validation in the context of high-stakes assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 7-15.

Shepard, L. A. (1997, summer). The centrality of test use and consequences for test validity. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice,5-13 .

Shohamy, E. (2001). Democratic assessment as an alternative. Language Testing, 18, 4, 373-391.

Shohamy, E., Donitsa-Schmidt, S., and Ferman, I. (1996). Test impact revisited: Washback effect over time.Language testing, 13, 298-317.

Stoneman, B. (2006). The Impact of an Exit English Test on Hong Kong Undergraduates: A Study Investigating the Effects of Test Status on Students' Test Preparation Behaviours. Unpublished PhD Dissertation. The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China.

Stoynoff, S., and Chapelle, C. A. (2005). ESOL Tests and Testing. Virginia, Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc.

Taleporos, E. (1998, summer). Consequential validity: A practitioner's perspective. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 20-34.

The General English Proficiency Test as a graduation threshold: the high-intermediate level for National Taiwan University and National Chengchi University( ) (December 6, 2005), United News ) Available at http://designer.mech.yzu.edu.tw/cgi-bin/mech/treplies. asp?message=1186

The survey on college students' English proficiency ( ) (November 6, 2003) Central News Agency () Available at http://www.merica.com.tw/win-asp7/aintain/ShowNews. asp?id=480.

Wall, D. (2005). The impact of high-stakes examinations on classroom teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yen,W, M. (1998, summer). Investigating the consequential aspects of validity: Who is responsible and what should they do. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 5.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2009 vol:11 nro:1 pág:93-105

Research Article

Evaluating the appropriateness and consequences of test use

Evaluación de la conveniencia y de las consecuencias del uso de pruebas

Yi-Ching Pan

Center of General Education The National Pingtung Institute of Commerce, Taiwan Department of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics University of Melbourne, Australia E.mail: y.pan@pgrad.unimelb.edu.au

Abstract

This paper addresses the issue of whether it is appropriate for universities or junior colleges to set foreign language proficiency requirements for graduation and offers a historical review of the relationship of test validity and test use. Examples of how to evaluate the appropriateness and consequences of test use are presented in order to discover what factors must be taken into account that contributes to the decision-making process. Finally, a model that specifies what evidence needs to be collected in support of a valid test decision is offered to help make decisions of test use more convincing and accordingly more beneficial to those individuals and groups who are affected by the tests.

Key words: Test validation, proficiency measurement, language assessment

Resumen

En este artículo se plantea el problema de si es apropiado para las universidades o colegios establecer las pruebas de desempeño en lengua extranjera como requisito para la graduación. Se ofrece una revisión histórica de la relación entre la validez y el uso de la prueba. Se presentan ejemplos de cómo evaluar la conveniencia y las consecuencias del uso de estas pruebas para indagar sobre los factores que deben tenerse en cuenta en los procesos de toma de decisiones. Finalmente, se ofrece un modelo que especifica las evidencias que deben recolectarse para apoyar la decisión sobre una prueba válida y sobre un uso mas convincente y beneficioso de las pruebas para los individuos que deben tomarlas.

Palabras claves: validación de pruebas, medidas de desempeño, medidas de conocimiento de lengua

Introduction

“Tests are not developed and used in a value-free psychometric test-tube; they are virtually always intended to serve the needs of an educational system or of society at large” (Bachman, 1990: 279). This implies that tests can be used for a multitude of functions. Cheng (2005) and McNamara and Roever (2006) provided several examples: the use of examinations for making such decisions as selecting candidates for education, employment, promotion, immigration, citizenship or asylum, upgrading the performance of schools and colleges, implementing educational policies, reforming educational systems, deciding on the distribution of funding, and so forth.

Given the potential power of tests, the decision to use tests for such practices as these, accordingly, has a significant impact not only on the individuals involved, including students, teachers, administrators, parents, and the general public, but also on the classroom, the school, the educational system and the society as a whole (Bachman & Palmer, 1996; Wall, 2005). Due to the fact that the influence of tests involves a variety of stakeholders, researchers (Bachman, 2005; Bachman & Palmer, 1996; Cronbach, 1988; Kane, 2002; Messick, 1989; McNamara & Roever, 2006; Shohamy, 2001; Shepard, 1997, among others) have contended that it is essential to justify test use and investigate its consequences.

What is the best way to evaluate the appropriateness of using tests for making decisions, particularly with regard to the question of whether it is appropriate for universities or junior colleges to set foreign language proficiency requirements for graduation? This paper attempts to address this issue by starting off with a historical review of the relationship of test validity and test use. Examples of how to evaluate the appropriateness and consequences of test use are presented in order to discover what factors must be taken into account that contribute to the decision-making process. Finally, a model that specifies what evidence needs to be collected in support of a valid test decision is offered to help make decisions of test use more convincing and accordingly more beneficial to those individuals and groups who are affected by the tests.

Historical Perspectives on Test Validity and Test Use

This section provides an overview of the traditional concept of validity, moves on to test validity as a unitary concept for making appropriate, useful and meaningful inferences from test scores and test use, and concludes with a generalization of the issue of consequences of test use.

Validity is the central concern in any effort to develop a test. Traditionally, test validation was undertaken by examining the psychometric qualities of the test itself. Put in Chapelle’s (1999) words, validity was regarded as a “characteristic of a test” (p. 258). In the first edition of Educational Measurement, Cureton (1951, p. 621) stated, “The essential question of test validity is how well a test does the job it is employed to do.” Robert Lado (1961, p. 231) defined validity as “Does a test measure what it is supposed to measure? If it does, it is valid.”

However, in the past two decades, the issue of test validity has increased in breadth and complexity, shifting away from the traditional concentration on different types of validity to an augmented view of validity dependent upon many sources of evidence, including the situation in which the test is used.

Cronbach (1988) considers validation a persuasive argument that should include a debate of the pros and cons arguments to defend the interpretation drawn from a test. He also stresses the importance of understanding the context of test use in addition to understanding what brings about test scores. He asserts that in order to make a convincing validity argument to a diverse audience, the beliefs and values in the validity argument must link “concepts, evidence, social and personal consequences and values” (p. 4). In light of this, Cronbach has given attention to consequences in his discussion of the validity argument and this then foreshadows the importance of investigating the consequences of test use.

In his acclaimed paper regarding validity, Messick (1989) developed the concept of consequential validity—which focuses not only on construct validity but also on social values and consequences of test use. To justify a particular test interpretation and test score use, Messick claims that issues of construct validity, relevance/utility, value implications, and social consequences all must be addressed. However, Messick’s unified model of construct validity focuses little on providing clear guidelines for exploring the consequences of test use.

Still very much in the same vein, Shohamy (2001a; 2001b) asserts that Messick’s primary contribution in the 1980s was his contention that the consequences of test interpretation on society and test use were an integral component of validity, emphasizing that testing is not an isolated, valuefree matter. The importance of validating not only the test itself but also the inferences drawn from test scores is not lost on Kane (2001; 2002) who has pointed out that the interpretation, inferences or decisions of test use are subject to validation. Recently, McNamara and Roever (2006) have stated that since tests can have widespread and unforeseen consequences, a language test that is psychometrically validated does not necessarily denote a test favourable for society, and they also propose the need to develop a social theory to assist test developers and researchers in better comprehending testing as a social practice for their work.

In view of the historical perspective of test validation mentioned above, validity has shifted focus from the wholly technical viewpoint to that of a test-use perspective. The investigation of the consequences of test use and the justification of test use are now regarded as vital steps in validating a test. However, the abovementioned theoretical studies did not provide a set of procedures on how to either investigate the consequences of or justify test use, although they do reach a consensus that such evaluation must provide evidence both for and against proposed test score interpretation and use, implying that intended and unintended consequences of test use must also be investigated (Bachman, 2005; McNamara, 2006; McNamara & Roever, 2006).

Examples of Evaluating the Appropriateness and Consequences of Test Use

What consequences should be taken into account during decision-making? As Stoynoff and Chapelle (2005) point out, “validation theory is too open-ended” and “if validity is considered as an argument that can draw on a wide range of evidence, how much evidence does one need to justify test use?” (p. 138). Moreover, Fremer (2000, p. 2), and Green (2000, p.8) contend that concrete examples will help assist illustrating validation tasks. Because of this, four examples of the procedures for evaluating the suitability and consequences of test use will be presented to help readers consider how to make appropriate decisions about test use.

Validity Models

Chudowsky’s focus groups (1998) Chudowsky utilized focus groups as a technique to investigate the impact of Connecticut’s high school assessment after the first two years of implementation. First, the background of the Connecticut Academic Performance Test (CAPT) was reviewed including its goal, time of inception, examinees, format and components. Next, interviews were conducted with teacher focus groups consisting of 73 teachers at seven schools of different sizes located in both rural and suburban areas with parents from various social strata. The topics for the interviews were the influences of the CAPT on: a) curriculum and instruction, b) teachers’ expectations of students, c) students’ behaviour and attitudes, d) parents’ behaviour and attitudes, and e) professional development. Finally, results were reported into two major sections. The first was a summary of the consequences by teachers across the seven schools, and the second was a categorization of schools based on the general attitudes of their teachers toward the assessment.

This study has offered a thorough investigation on the role that teachers play in the process of collecting evidence of both positive and negative consequences of test use. However, voices from different stakeholders such as students, administrators, parents, and test publishers should also be involved and surveyed to help ensure a more comprehensive evaluation of the consequences (Cronbach, 1989).

Lane, Parke, and Stone’s evaluation frame-work (1998)

Lane, et al’s (1998) research provides a general framework for examining the consequences of state-wide assessment programs that intend to improve student learning by holding schools accountable. Assessment program level, school district level, school, classroom level and other relevant contextual variables are taken into consideration in the process of evaluation to understand the impact of tests on the implemented curriculum, instruction, beliefs and motivation, student learning, professional development support, teacher involvement, preparation for the assessment, and so forth. A careful evaluation of both intended effects and unintended negative effects is vital. Evidence for the evaluation of the consequences of test use can be obtained by means of document analysis, surveys, interviews and classroom observations from the various levels as mentioned above, as well as various stakeholders such as administrators, students, and teachers “within the educational system” (25), and parents, future employers, and the community “outside of the educational system” (25). For example, a thorough understanding of the test in terms of its format, content, and scoring criteria should be undertaken. Moreover, classroom instruction and assessment materials can be collected, and systematic classroom observation can be conducted to realize the instruction processes and activities. It is also critical to collect information about the curriculum and professional development support.

Although this research aims, as its title suggests, to offer a framework for evaluating the consequence of test uses, the procedures of how to do so are not clearly stated for educational practitioners to follow. It may be due to the fact that the context for each assessment is different; therefore, it is difficult to offer one formula to fit every situation because of the variation between programs (Kane, 2002). To this point, there has not been a significant number of rules or procedures presented for the purpose of making judgement. (House, 1995; House & Howe, 1999, as cited in Ryan, 2002)

Lane & Stone’s strategies (2002)

According to Lane and Stone (2002), there are three procedures for examining the consequences of an assessment program. First, the goal for the assessment program must be established. For example, in Taiwan, English certification exit requirements were established to increase student motivation to study and to enhance their English proficiency. Test consequences would therefore be measured against the yardstick of how well students met that goal.

Second, a set of propositions that could support and refute the intended goal of the assessment program needs to be established. In other words, both positive and negative effects need to be proposed at this stage in order to justify the decision of test use. For example, as a result of establishing English certification exit requirements in Taiwan, the following positive washback effects are envisioned

a. Most students allot more time to English study.

b. Most students' English scores increase.

c. An increased number of hours of English classes are offered to give students more contact with English.

d. More educational resources such as selfaccess centers and English materials are provided to offer students more access to English study after class.

e. More professional development support is provided to teachers to comply with exit requirements. f. Instruction and curriculum change to match what is covered on the certification tests.

The following unintended washback effects seem likely to occur:

a. Most students will study for the test and a greater percentage of teachers will teach to the test.

b. Most teachers will experience increased workload and pressure.

c. Some students will experience decreased motivation, increased pressure, and/or greater financial burdens.

Third, data from focus groups, interviews, questionnaires, and classroom observations needs to be collected as evidence of validity. This evidence should come from school principals, administrators, and teachers, as well as students.

These three procedures provide an in-depth investigation of the consequences of tests in that they consider various stakeholders and take a number of factors into consideration. However, it is essential that while collecting evidence to devote attention not only to the quality of the data collection techniques but also to consider practical matters such as time, costs, and resources. Practical issues of whether test users have sufficient resources to utilize with such an extensive system of data collection and analysis needs to be considered.

Ryan’s process approach (2002)

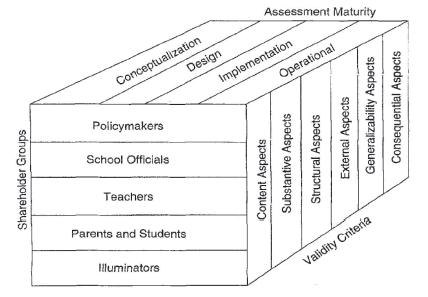

Ryan’s study (2002) proposes a process approach to validity inquiry (see Figure 1). In his view, validation is the overall evaluation of the intended and unintended interpretations and uses of test score interpretations. This process approach consists of three facets: a) validity criteria, b) stakeholders, and c) assessment maturity. The validity criteria facet is adopted from Messick’s (1995) theory of unified validity. The stakeholder facet involves different groups of stakeholders who hold various perspectives and concerns regarding the decision of test use. The assessment maturity facet refers to who, how, and when to include stakeholders in the assessment validation. During the process of evaluation, the evaluator plays a role in “specifying study questions and in collecting data and all other phrases of the validation process to bring a balanced perspective avoiding the confirmationist bias” (p. 8).

Ryan’s study emphasizes not only the collection of evidence from a group of different stakeholders but also investigates the possible consequences of test use by scrutinizing both the qualities of the test and the different timing of implementing the test use (conceptualization, design, implementation, and operational stages). Moreover, he develops a set of strategies for validation inquiries that address the inclusion of stakeholders in the validation process and delineate the tasks and activities of the test evaluators and stakeholders therein. The biggest challenge is how to manage conflicting views and advice. Of particular concern is the question of who is suitable to play the role of the “evaluator” that is endowed with the difficult task of synthesizing a variety of viewpoints from different groups of stakeholders. Who the evaluator is could also have a decisive impact on the assessment.

Implications for evaluating the consequences of test use

Certain implications can be drawn from the aforementioned studies on the evaluation of the consequences of test use:

1. To evaluate test use, these inquiries need to be addressed

a. What is the purpose of making the decision?

b. What positive consequences of test use support the decision?

c. What negative consequences contraindicate the decision?

d. Do positive effects seem to outweigh the negative ones?

2. A variety of stakeholders (e.g. teachers, students, administrators) should be engaged when collecting evidence regarding both intended and unintended consequences of test use

3. A triangulation of various methods to collect data needs to be undertaken.

4. Who is responsible for collection and evaluation of consequential evidence is still unanswered, though certainly not unasked, question. Often political mandates override educational policies. The impact of politics in influencing assessment policies should not be overlooked.

5. Practical matters such as time and cost must also be taken into consideration when collecting data for evaluating test use.

A Proposed Framework for the Evaluation of Test Use

Stoynoff and Chapelle (2005) state, “validation theory encompasses a wide range of concerns that most people would not be able to address without specifying any practical boundaries” (p. 139). Validation theory does not provide a clear set of procedures for that are easy for most people to follow. It is essential to construct a practice-oriented guide to inform decisionmakers how much or what evidence is required to justify test use. Test users, policymakers, administrators or teachers are then in the best position to make decisions about assessments (Stoynoff & Chapelle, 2005, p. 139).

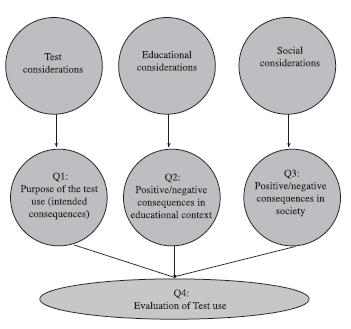

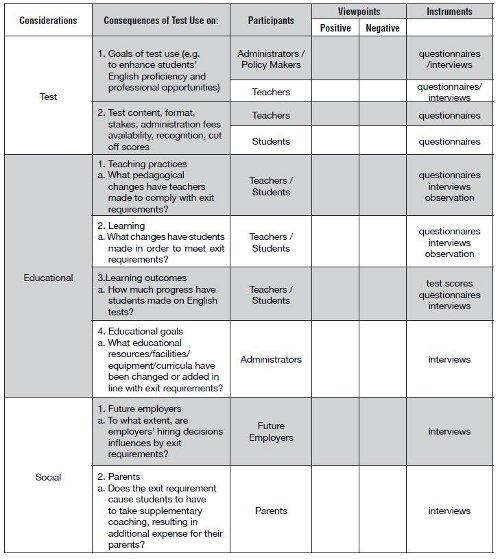

To this end, a framework (see figure 2) for evaluating the appropriateness of test use, drawn from the review of the studies discussed above, was created. This proposed framework consists of three considerations: test, educational, and social, to address the four questions mentioned above that need to be answered in order to justify test use.

Test considerations are to explore the purpose of test use and what tests are appropriate to use, educational and social considerations are to investigate positive and negative consequences collected from various stakeholders in both educational and societal contexts, and finally decision makers evaluate whether positive consequences outweigh negative or whether the purpose of test use is achieved based on the data collected from.

To better understand how this framework works, it will be illustrated in the context of the use of English proficiency test(s) as graduation requirements at a number of universities and technical colleges in Taiwan.

Context of the study

In Taiwan, English is taught as a foreign language (EFL) within a classroom-based environment. After at least two years of English instruction in elementary school, students will receive six years of English education before they attend colleges or universities. Students need to take two public exams, the Basic Competence Test (BCT) to enter senior high school and the College Entrance Examination (CEE) for higher institutes of learning. These two examinations evaluate students’ English proficiency, and their English scores are taken as one of the criteria for school admissions and used by students to help choose the school they wish to attend. University students are usually required to take 3-4 hours of English every week in their first year. After finishing the 3- or 4-credit-hour English course, unless they continue to study in graduate school, they do not need to take tests like BCT or CEE to evaluate their overall English proficiency when graduating.

Despite significant exposure to English (nine years of English classes from elementary school to college/university), the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) CBT Score Data Summary from 2002-2006 provided by the Educational Testing Service (http://www.ets. org/Media/Research), shows Taiwanese students’ scores ranked from the fourth-lowest to the seventh-lowest among the thirty-two countries in Asia. In another ETS survey done in conjunction with National Chengchi University in Taiwan, 32.3% of Taiwan’s college students examined for English proficiency function at the level of students in their third year of junior high or first year of high school (Huang, 2003). According to its developer, the LTTC (Language Testing and Training Center), the GEPT elementary level (General English Proficiency Test) is considered competency equivalent to a junior high school graduate’s English proficiency. However, the percentage of college graduates who have passed the first stage of the GEPT elementary level, based on the LTTC score statistics in 2002 (http://www. ltc.com.tw), was only 14.

To address this need for improvement, the Ministry of Education has encouraged universities or colleges of technology to set an English benchmark or threshold for graduates so that they will be able to achieve a certain level of English to meet the needs of the job markets, domestically and internationally. Moreover, a priority goal of the four major educational policy pivot points for 2005-2008 proclaimed by the Ministry of Education in February 2004 is to have 50% of students at universities and colleges of technology achieve an English proficiency equivalent to General English Proficiency Test (GEPT) Intermediate and Elementary Levels, respectively, by 2008.

For the reasons stated above (i.e. the government’s goal of increasing English proficiency and also to enhance students’ competitiveness in the job market or further studies), some universities and colleges of technology have adopted the GEPT or other English proficiency tests such as TOEIC, TOEFL and IELTS as a threshold for graduation. Some require students to pass GEPT Intermediate Level, GEPT Elementary Level, TOEFL CBT 193 (or TOEFL pencil test 500), school-developed English proficiency tests, etc. On the whole, the GEPT is considered the most popular test among students for meeting the exit requirement because of the ease of registration for taking the test and the cheaper cost than other English proficiency tests offered in Taiwan. Other universities and colleges that have not established any English exit requirements, however, have set reward policies to encourage students to pass the GEPT by either offering them financial incentives or waiving their regular compulsory English classes.

The establishment of an English requirement for graduation by having students take English proficiency tests has met with opposition. For example, some schools such as Ming Chuan University in Taipei (United News, December 6, 2005) have argued that universities or colleges are not cram schools, and do not hope to promote the atmosphere of “teaching to the test”, so they do not set any English requirement for graduation by having students take English proficiency test(s). Instead, they require students to take more English-related classes to enhance their students’ English proficiency. Some English educators also hold similar opinions. Dr. Liao, who works at Taipei Institute of Technology, is concerned that the English proficiency requirement will force teachers to teach to the test because school curricula will be related to the content of the English proficiency exams. All in all, negative washback brought about by the requirement will most likely manifest itself in teachers teaching to the test, students cramming for tests, and the narrowing of the curriculum. Dr. Liao has therefore suggested that English teaching should actually return to the essence of English for life-use by immersing students in an English environment. Setting an English proficiency test requirement for graduation is absolutely not a panacea. Moreover, some legislators (United News, December 19, 2003) have expressed their objections to the establishment of an English graduation threshold that requires students to pass proficiency tests. Legislator Li Chin Ann contends that there is little point in setting such a threshold because students have already been required to take regular English classes. As long as students pass the English classes, why should they have to pay for and take English proficiency tests?

It is obvious from the aforementioned debate that the issue of whether it is appropriate to establish an English requirement that forces students to take English proficiency tests as a graduation threshold has become a point of concern and a hot topic in the field of education in Taiwan.

Test considerations

Test considerations explore how well a test mirrors its goals or purposes of its use. To evaluate test use, we must first consider why a test is being used. Then we can consider what should be measured. The avowed goals of Taiwan’s English proficiency exit requirements are to motivate students to learn English, to enhance their overall English proficiency, and increase their market competitiveness. These goals have been clearly enunciated prescribed by both administrators and English teachers.

With these goals in mind, the next step is to decide whether ready-made English proficiency tests or tailor-made exams should be used to assess how well the objectives have been realized. The viewpoints of English teachers will play an important role because they can provide qualified opinions whether the test will have positive or negative washback on both teaching and learning. For example, if a test assesses mainly reading and listening skills, speaking and writing skills may be neglected in class. Another concern is if it will measure what students need for future employment. If most students at a school are business majors but the test primarily covers the English necessary in a hospital setting, the test will not determine the appropriate proficiencies. Teachers can also provide their thoughts regarding the cut-off score for the exit requirement based on their understanding of the students’ English skills. Will the test be too difficult or easy in terms of students’ English proficiency? If the test is not difficult enough, students may lose interest in it. If the test is too difficult, the number of students who cannot pass the test and therefore cannot graduate will increase. In other words, the stake of the test will decide on the level of test impact. As Alderson and Wall (1933) proposed in their 15 Washback Hypotheses, “tests that have important consequences will have washback; conversely, tests that do not have important consequences will have no washback.” (pp.20-21)

Opinions from students are also critical in determining which test to adopt. Stoneman (2006) and Shohamy et al. (1996) indicated that the perceived status of the test (i.e. locally made versus internationally known) was directly linked to students’ motivation, time, and effort expended. In addition, whether the test is affordable and readily available must also be taken into account from students’ points of view.

Educational considerations

Educational considerations refer to potential washback, either positive (normally intended) or negative (normally unintended), that occurs in the educational context. Stakeholders are students, teachers, and administrators. The educational goals for this exit requirement are to motivate students and enhance their proficiency. Test users can collect data to find evidence to either support or refute the advisability of test use. For example, from teachers’ perspectives, will they be compelled to “teach to the test” or will the test help them adjust the way they usually teach and ultimately enhance students’ learning? Does the establishment of the exit requirement bring a larger workload to teachers and impose unexpected pressure on them? Does the material that is tested match the objectives of the curriculum? From students’ perspectives, will the test motivate them to learn, or will they “study to the tests”? Will students cease to study English once they have passed the exit requirement? From the administrative perspective, does the school offer enough resources or professional training to help teachers and students cope with the decision of test use?

Social considerations

Social consideration refers to the effects the decision of test use have on society. Hulin et al. (1983, as cited in Bachman, 1990) claimed, “it is important to realize that testing and social policy cannot be totally separated and that questions about the use of tests cannot be addressed without considering existing social forces, whatever they are” (p. 285). The potential stakeholders at this stage are the public (e.g. parents and prospective employers) and the government. Consider some possible consequences of the example cited. For instance, in order for their children to pass the test to graduate, will parents need to aid them financially (coaching, test preparation materials)? Do students who pass the test receive preference from future employers? Like educational considerations, social considerations look for intended and unintended consequences within society that may be brought about by the use of the test. Since the context varies, the views of potential stakeholders should be considered. A social dimension washback study can assist in finding conclusions for this aspect of evaluation.

For each consideration, various tasks must be evaluated by engaging multiple stakeholders whose views contribute to identifying the strengths and weaknesses of test use.

Depending on the purpose of the test, test users may need to decide what considerations they will explore. For example, if the test use is for teachers’ classroom assessments, considerations may need to stress test and educational factors. However, if the decision for test use is highstakes, then a thorough evaluation of all three considerations is necessary. Since the contexts vary, the questions made for each consideration will also vary depending on how the test is going to be used. The more questions developed for each consideration, the more likely the decision of test use will be appropriate, but as Lane and Stone (2002) mentioned above, practical matters such as time, cost and resources are points of concern in terms of collecting data and doing data analysis.

In this proposed framework, the decision maker categorizes the considerations as positive and negative washback based on data, evidence or judgment gathered from questionnaires, interviews, and classroom observation. The decision is justified if positive outweighs negative. If negative washback exceeds positive, the decision requires reconsideration.

This framework must be easy to understand because validation theory usually does not provide a clear set of procedures that most school administrators can follow. Most decision makers (usually teachers or policy-makers) are not in the position to conduct validation research. With this framework, they can select questions for each consideration and that will determine intended and/or unintended consequences. They can thus compile evidence and make a final determination whether the test use is feasible and beneficial.

A checklist for evaluation of test use

Table 1 shows the stakeholders, instruments, and possible questions that may need to be involved, conducted and investigate in order to collect the data necessary for evaluating the appropriateness of test use in this context. Questionnaires, interviews, classroom observation, and test scores are the instruments often adopted to discover participants’ perceptions of and reactions to the decision of test use.

Conclusions

This framework proposed a comprehensive view to assess the appropriateness of test use by investigating test, educational, and social considerations. In addition, possible questions for each consideration, the stakeholders involved, and the instruments required are also provided to give evaluators an understanding of what evidence they must acquire so that they will be able to justify the appropriateness of test use.

Standardized EFL/ESL tests are often mandatory in educational settings with the intentions of promoting curricula innovation, motivating students, and accomplishing educational goals. Whether such test uses are appropriate, however, is seldom justified by decision makers. In their point of view, tests are a cost effective and efficient agent for achieving their goals; therefore, they impose a top-down, test-driven policy. It is essential to investigate the consequences of test use under test, educational, and social considerations to evaluate the appropriateness of test use. Because those who make decisions of test-use are not experts at test validation, the proposed model provides a clear guideline for them in regard to evaluating the appropriateness of test use. During this process, the voices of involved stakeholders will be heard in regard to their perceptions of and interactions with the test or the test-driven policy. By determining the negative and positive effects, the decision makers will find out what they need to revise in their implementation of the test-driven policy and everyone will therefore benefit from the policy.

References

Bachman, L. F. and Palmer, S. (1996). Language testing in practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bachman, L. F. (2005). Building and Supporting a Case for Test Use. Language Assessment Quarterly, 2, 1, 1-34.

Brennan, R. L. (2006). Perspectives on the evolution and future of educational measurement. In R. L. Brennan (Ed.), Educational Measurement (4th ed.) (pp. 1-16). CT: American Council on Education and Praeger Publishers.

Chapelle, C. A. (1999). Validity in language assessment. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 19, 254-272.

Cheng, L. (2005). Changing language teaching through language testing: A washback study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chudowsky, N. (1998, winter). Using focus groups to examine the consequential aspect of validity. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 28-38.

Cronbach, L. J. (1988). Five perspectives on validation argument. In H. Wainer & H. Braun (Eds.), Test validity (pp. 3-17). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cureton, E. E. (1951). Validity. In E. F. Lindquist (Ed.), Educational Measurement (3rd ed.), pp.621-694. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Fremer, J. (2000, December). My last (?) comment on construct validity. National council on Measurement Newsletter, 8, 4,2.

Green, J. (2000, December). Standards for validation. National Council on Measurement Newsletter, 8, 4, 8.

Green, D. R. (1998, summer). Consequential aspects of the validity of achievement tests: A publisher’s point of view. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 16-19.

Guion, R. M. (1980). On Trinitarian concepts of validity. Professional Psychology, 11, 385-398.

House, E. R. (1995). Putting things together coherently: Logic and justice. In D. M. Fournier (Ed.), Reasoning in evaluation: Inferential leaps and links (pp. 33-48). New Directions for Evaluation, 68.

Hulin, C. L., F. Drasgow, and C. K. Parsons. (1983). Item response theory: Application to psychological measurement. Homewood, Ill.: Dow Jones-Irwin.

Kane, M. T. (1992). An argument-based approach to validity. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 3, 527-535.

Kane, M., Crooks, T., and Cohen, A. (1999). Validating measures of performances. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 18, 2, 5-17.

Kane, M. T. (2001). Current concerns in validity. Journal of Educational Measurement, 38, 4, 319-342.

Kane, M. T. (2002). Validating high-stakes testing programs. Educational Measurement, 21, 1, 31-41.

Lado, R. (1961). Language testing: The construction and use of foreign language tests. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lane, S., and Stone, C. A. (2002, spring). Strategies for examining the consequences of assessment and accountability programs. Educational Measurement, 23-30.

Lane, S., Parke C. S., and Stone, C. A. (1998, summer). A framework for evaluating the consequences of assessment programs. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 24-27.

Linn, R. L. (1997, summer). Evaluating the validity of assessments: The consequences of use. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 14-16.

Linn, R. L. (1998, summer). Partitioning responsibility for the evaluation of the consequences of assessment programs. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 28-30.

McNamara, T., and Roever, C. (2006). Language testing: the social dimension. Oxford: Blackwell.

McNamara, T. (2006). Validity in Langauge Testing: The Challenge of Sam Messick’s Legacy. Language Assessment Quarterly, 3, 1, 31-51.

Mehrens, W. A. (1997, summer). The consequences of consequential validity. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice,16-18.

Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement (3rd ed.) pp13-103. New York: Macmillian. 13-103.

Messick, S. (1995, winter). Standards of validity and the validity of standards in performance assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 5-8.

Messick, S. (1996). Validity and washback in language testing. Language Testing, 13,3,241-256.

Moss, P. A. (1995, summer). Themes and variations in validity theory. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 5-13.

Moss, P. A. (1998, summer). The role of consequences in validity theory. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 10-12.

Legislators: The General English Proficiency Test cannot be set as the graduation threshold (December 19, 2003), United New Available at http://enews.tp.edu. tw/News/News.asp?iPage=7&UnitId=117&NewsI d=8803.

Liao, P. (2004). The effects of the GEPT on college English teaching. Available at http://home.pchome. com.tw/showbiz/posenliao/page/page_5_011. htm.

Popham, W. J. (1997, summer). Consequential validity: Right concern-wrong concept. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice,9-13.

Reckase, M. D. (1998, summer). Consequential validity from the test developer’s perspective. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice.13-16

Ryan, K. (2002). Assessment validation in the context of high-stakes assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 7-15.

Shepard, L. A. (1997, summer). The centrality of test use and consequences for test validity. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice,5-13 .

Shohamy, E. (2001). Democratic assessment as an alternative. Language Testing, 18, 4, 373-391.

Shohamy, E., Donitsa-Schmidt, S., and Ferman, I. (1996). Test impact revisited: Washback effect over time. Language testing, 13, 298-317.

Stoneman, B. (2006). The Impact of an Exit English Test on Hong Kong Undergraduates: A Study Investigating the Effects of Test Status on Students’ Test Preparation Behaviours. Unpublished PhD Dissertation. The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China.

Stoynoff, S., and Chapelle, C. A. (2005). ESOL Tests and Testing. Virginia, Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc.

Taleporos, E. (1998, summer). Consequential validity: A practitioner’s perspective. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 20-34.

The General English Proficiency Test as a graduation threshold: the high-intermediate level for National Taiwan University and National Chengchi University (December 6, 2005), United News Available at http://designer. m e c h . y z u . e d u . t w / c g i - b i n / m e c h / t r e p l i e s . asp?message=1186

The survey on college students’ English proficiency (November 6, 2003) Central News Agency Available at http:// www.merica.com.tw/win-asp/maintain/ShowNews. asp?id=480.

Wall, D. (2005). The impact of high-stakes examinations on classroom teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yen,W, M. (1998, summer). Investigating the consequential aspects of validity: Who is responsible and what should they do. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 5.

Métricas

Licencia

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/