DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.83Publicado:

2010-07-01Número:

Vol 12, No 2 (2010) July-DecemberSección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónBuilding students’ voices through critical pedagogy: braiding paths towards the other

Construcción de las voces de los estudiantes a través de la pedagogía crítica: trenzando caminos hacia el otro

Palabras clave:

Pedagogía crítica, Otredad, voz, culturas oprimidas, culturas dominantes, multiculturalidad, discriminación, empoderamiento. (es).Palabras clave:

critical pedagogy, Otherness, voice, oppressive cultures, dominant cultures, multiculturality, discrimination, empowerment (en).Descargas

Referencias

Ada. A. F. (1988) Creative Reading: A Relevant Methodology for Language Minority Children. In L. Malave (Ed.), NABE' 87. Theory, research and application: Selected papers (pp. 97-111). Buffalo: State University of New York Press.

Bergo, B. (2007). Emmanuel Levinas. Stanford University Encyclopedia of Philosophy Retrieved January 19, 2009 web site http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/levinas/#int

Cummins, J. (2001) Negotiating Identities: Education for Empowerment in a Diverse Society.

California Association for Bilingual education CABE-Eskin, M. (2000). Ethics and Dialogue: In the works of Levinas, Bakhtin, Mandelshtam, and Celan. Great Britain. Oxford.

Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum. (Original work published 1970). In: Ibrahim, A. (Autumn, 1999). Becming black: rap and hip-hop, race, gender, identity, and the politics of ESL learning. TESOL Quarterly,Vol. 33 (3), 349-367.

Lacan, Ink. Origin of the word Otherness.Retrieved March 3, 2010, from http//www. lacan. com

Lee, C. (2000). Signifying in the Zone of Proximal Development. In Lee, C. & Smagorinsky, P. (Eds.), Vy-gotskian perspectives in Literacy Research.

Constructin Meaning through Collaborative inquiry. (pp. 191-255) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levinas, E. (2006). The Face, Ethics, and God. Retrieved on January 15, 2009 from http://blogs myspace. com/index.cfm?fuseaction=blog.view&friendId =82758112& blogId=135 952 982

Magendzo, Abraham. An Ethical-Political Sustainability for Citizen Education. CIVNET: Center for Civic Education, International Conference of Civic Education in an Age Worldwide Migration, Munster, Germany. 17 October 2007. Conference.

Magendzo, A. (2006). Diseño y Elaboración de Currículum una tarea de Negociación de saberes y un juego de poderes, Retrieved September 10, 2008,from http://mt. educarchile.cl/ mt/ amagendzo/archives/2006/04/diseno_y_elabor.html

McLaren, P. (2003). Life in Schools: An Introduction of Critical Pedagogy in the Foundations of Education. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Myers, M. (1997). Qualitative Research in Information Systems. Retrieved June 26, 2009, from http://www.misq.org/discovery/MISQD_isworld/index. html#Introduction.

Onbelet, L. (n.d.) Imagining the Other: The Use of Narrative as an Empowering Practice. In McMaster Journal of theology and Ministry. Retrieved September 10, 2008, from http:// www. mcmaster. ca/mjtm/3-1d.htm

Pennycook, A. (2001) Critical applied Linguistics: A Critical Introduction. London: Lawrence E r l b a u m Associates Publishers.

Quintero, L. (2006). School Literacy Practices Closer to Home: The New Challenge of Literacy Learning. CALJ, (8), 216-227.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory, Procedures and Techniques. London: Seige Publications.

Wink, J. (2005). Critical Pedagogy. Notes from the Real World. New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2010 vol:12 nro:2 pág:55-71

Research Articles

Building Students’ Voices through Critical Pedagogy: Braiding Paths towards the Other

Construcción de las voces de los estudiantes a través de la pedagogía crítica: trenzando caminos hacia el otro.

Silvia Patricia Umbarila Gómez

Academic Coordinator Colegio Colombia Viva IED, Bogotá, Colombia E-mail: silvipato@yahoo.es

Abstract

This study attempts to promote social reflection and cultural recognition in the multicultural scenario of the classroom. This is a qualitative study carried out with ninth grade students at a public school in Bogotá. The main objective is enrolling the students in critical pedagogy practices that allow them the construction of the sense of Other. The experience was implemented through the students’ exposure to authentic historical facts in which they acquired knowledge about social, political, and cultural issues. This exposure then encouraged reflection during the classes, empowering the students with a voice to refuse and denounce. Students’ voices were identified and interpreted through the instruments used, video recordings and artifacts. The results highlighted the importance of giving students a voice that enriches their role as citizens in terms of their responsibility and commitment towards Others.

Resumen

Este estudio pretende promover la reflexión social y el reconocimiento cultural en el escenario multicultural del salón de clases. Este es un estudio cualitativo se llevó a cabo con estudiantes de noveno grado de un colegio público de Bogotá. El objetivo principal es involucrar a los estudiantes en prácticas de pedagogía crítica que les permita la construcción del sentido del Otro. La experiencia se implementó con la exposición de los estudiantes a hechos históricos, en los que adquirieron conocimiento de los aspectos sociales, políticos y culturales. Dicha exposición animó la reflexión durante las clases, dándoles el empoderamiento de tener voz para rechazar y denunciar. Entonces, las voces de los estudiantes se identificaron e interpretaron a través de los instrumentos usados: grabaciones de video y producciones escritas de los estudiantes Los resultados resaltaron la importancia de dar a los estudiantes una voz que enriquezca su rol como ciudadanos en términos de su responsabilidad y compromiso hacia los Otros.

Palabras clave: Pedagogía crítica, Otredad, voz, culturas oprimidas, culturas dominantes, multiculturalidad, discriminación, empoderamiento.

Introduction

As a teacher in a public school in Bogota, Colombia, I have become familiar with the difficult living conditions faced by the less privileged class. A considerable number of students from public schools have dysfunctional families in which they have neither a father nor a mother figure. Some of them are from different regions of Colombia, and most of this percentage are from rural regions. They arrived in the city because their parents were unemployed or displaced. Thus, these students have suffered the consequences of the violence in our country. Another relevant issue is that the local context in which the students are immersed obligates them to follow the rules “imposed” by the prevailing subcultures, especially some subculture gangs. Most of them live subordinated to these rules and to the social relations imposed by these subculture gangs. In fact, a certain number of the problems that students stir up in the school are caused from situations derived from the neighborhood. Therefore, some of them were very aggressive as a way to exert their power over their peers, and others become victims of the bullying.

Students from public schools are immersed in permanent struggles of power in their relationships. They represent the existence of social inequity, injustice, discrimination, and disempowerment. These are consequences of the lack of opportunities and the existing social differences in the context in which they live. The students, along with their families, struggle day after day with a lack of work, food, medical care, and free time to develop as an individual. This current situation provokes in the learners unpredictable responses that affect their relationships. In this sense, I have identified through class observations that students experience isolation and voicelessness in their relations with others including: with their teachers and parents as dominant figures and with their peers in their competition with each other.

By implementing critical pedagogical practices learners are enabled to ask questions about aspects of the dominant culture. They examine the surrounding power structures of the dominant societies through history, and learn how sometimes these kinds of power structures are reproduced when a person assumes the role of the prevailing culture. Moreover, students analyze critically why they have no voice in their relationships in the society and why they may have feelings of isolation and powerlessness.

Also, students are between the adults’ alienation and their own competition as peers. They feel isolated as a class and as monadic individuals. They need to question the social, economic, and cultural issues surrounding their relationships and understand why they feel as they do. Then, students are provided with ways of analyzing their own histories and the cultural politics in which they are embedded.

Under this perspective, the focus of this qualitative study relies on analyzing the voices that ninth graders build at a public school in Bogota when they are engaged in living and in studying historical, social, political, and cultural issues. In this sense, Critical Pedagogy (McLaren, 2003) would be the tool to prepare students to be critical agents of transformation in their own lives, as well as allow them to act on the larger social and political struggle rather than be voiceless and passive citizens.

Within this framework, students are invited to analyze critically the reasons behind the maintenance of some of these practices through the years. In this way, teachers can help students understand how coercive relations of power limit the opportunities for educational, social, and cultural advancement in subjugated groups and, to discover their voices that have been silenced in order to empower their role of becoming patriotic and responsible citizens to transform the statusquo.

Braiding the Path to Critical Pedagogy

Critical Pedagogy is a natural response to current human conditions (Wink, 2005). Throughout human history the search for new unexplored boundaries, new territories, and new possibilities has been a constant goal and freedom has been the principle that guides this goal.

I believe that school is one of the most important institutions through which students can enrich themselves. Critical Pedagogy is a natural response to the human condition that considers the school as the site to save society from catastrophe. As McLaren (2003) states “schools should be sites for social transformation and emancipation, places where students are educated not only to be critical thinkers, but also to view the world as a place where their actions might make the difference” (p. 187).

Therefore, critical pedagogy identifies empowerment as one of its most important tenets and the way to make the values of justice, social responsibility, acceptance, recognition, and respect concrete. (McLaren, 2003, p. 211) Thus, a critical educator is committed to empower the powerless. In this regard, empowerment is the choice for vulnerable and voiceless communities in order to enable them with knowledge and arguments so they can be more critical and aware of their own and Others’ reality.

Any teaching process is affected by political, cultural, economical, historical, and ethical concerns, among other aspects. With these ideas in mind, we as teachers have the obligation to promote reflection and dialogue about issues concerning inequities in order to raise our students’ awareness towards social injustice, especially in Colombia. Students had the opportunity to acquire critical knowledge about class division and power relations to bring the theory into practice as the means to interrogate, identify, and occupy a place in the world, which addresses the next construct, voice.

Finding the Students’ Voice

From a socio-cultural perspective, Lee (2000) has asserted that “language serves as a conceptual organizer, primary medium through which thinking occurs” (p. 192). Language creates the means by which we interpret, think, and read the world. This is the relation between language and thought, which is not static, as Wink (2005) has stated: “as words develop, thought develops; and as thought gradually develops, the words change with the emerging ideas” (p. 31).

With this idea in mind, language is the only means by which students develop their own voice; at the same time, it is through voice that language becomes concrete. Giroux has stated that voice “refers to the multifaceted and interlocking set of meanings through which students actively engage in a dialogue with one another” (cited in McLaren, 2003, p. 245).

Once students know, analyze, and are sensible towards Others’ suffering they can reflect upon the power relations that dominate this suffering. It is a commitment in terms of provoking responses to ideas, behaviors, actions, and perspectives and favoring cultural and social reconciliation in honor of justice and truth, which are concerned with the next construct: Otherness. It represents the hope of change.

Voicing the Otherness

The term Otherness has been used to understand the processes by which some cultures have excluded Others or subordinated them. In this sense, Otherness gives accounts of aspects such as identity and the role that some people assume in relation to others’ acceptance. Otherness comes from the German word alter. It was established by Emmanuel Levinas (1974) in a series of essays collected under the title Alterity and Transcendence (cited in Bergo, 2007).

The Other is a philosophical concept to define a person who is other than oneself, as opposed to the same. The term has been associated predominantly with disempowered people; for this reason, it is a necessary concept when we study cultural difference. The term Other is usually capitalized. The use of the capital O originated in the writings of Lacan (n.d.). His use of the term establishes distinction from other (with small o) from Other (with capital O). The former Lacan’s use came from post-colonial theory in which other refers to the marginalized people identified by their difference from the central power. The latter has been called the great Other by Lacan (n.d.), in whose gaze the Other gains identity and could be next to the central power.

The face-to-face encounter with the Other is called the Visage (Eskin, 2000) and implies being conscious that the Other is different from me. We are equals in our nature but different in our vision of the world. But understanding the Visage concept requires the ability to be able to hear the Other, as it is possible that the Others have already spoken to us but we have not heard them; and most important, the Other demands from me a responsibility. Responsibility is the answer to the call of the Other.

To be able to accept, respect, and admire differences in Others, students need to recognize what they like and value in themselves and to feel secure in their own identity while becoming sensitive to Others’. The first way in Others recognition is by being compassionate with the Other. This compassion is not understood as feeling pity, but as stepping into somebody else’s shoes, as Marcuse mentioned: “Look, I know wherein our most basic value judgments are rooted-in compassion, in our sense for the suffering of Others” (as cited in Pennycook, 2001, p. 7).

Habermas (1989) made use of the concept of Other in the communicative action which references that all human actions are validated through the moral norms which derive from the recognition of the acting subjects. From this perspective, he considers the importance of the formation of the Other. In this respect he identifies two processes: individuality and individuation. The former process identifies self-comprehension from the relation of a second person. It is an inter-subjective relation: I-you. The latter concept refers to the unique character of the person within the communicative community (as cited in Magendzo, 2007, p. 2).

Since the middle of the 1980’s, the work on human rights education in Latin American has dealt with a focus on the concept of Otherness. Precisely, Magendzo (2007) has guided this work towards Otherness in the formation of the participative citizenship in which a sense of responsibility and interest in public matters are requirements.

Just as important, this research study provides a strong foundation upon which students can build a sense of the Other. The reflection toward the issues of inequity and social injustice help raise students awareness in regards to the Others’ existence that allow them firstly, to understand their own personal experiences in a way that develops resiliency to assume human beings’ difficult situations and secondly, students recognized their role as citizens who observe differences and social problems as more than simple circumstances or isolated facts.

Methodology

This qualitative study focuses on students’ points of view and their analyses of the situations as connected to their reality. It aims at responding to the research questions: What voices do ninth graders build in their English class when addressing historical, social, political, and cultural issues? What is the role of the learners’ voices in their construction of Otherness?

In the study students account for their analysis of the world by means of a particular use of language. For this reason the study also includes a critical perspective which implies a constant reflection to describe the reality of classes through the use of video recordings that focus on the interaction between students and teacher. The students were video recorded during the class dialogue generated from the discussions of each one of the episodes composing the intervention plan. In this way, video recordings became an important source for analyzing and describing the process through which students could express their voices and achieve their sense of Otherness. In order to go more indepth in the exploration of the data collected I used students’ artifacts.

Students’ artifacts were used to track the progess of the students’ voice constructed towards the issues addressed. These were mainly workshops in which the instructional method was implemented: These artifacts were developed at the end of each of the episodes.

Context

This research study was carried out at a public school located in the northwest of Bogota, Colombia. Participants selected for this purpose were students in ninth grade. The class consisted of 45 students whose ages ranged from fourteen to seventeen years old.

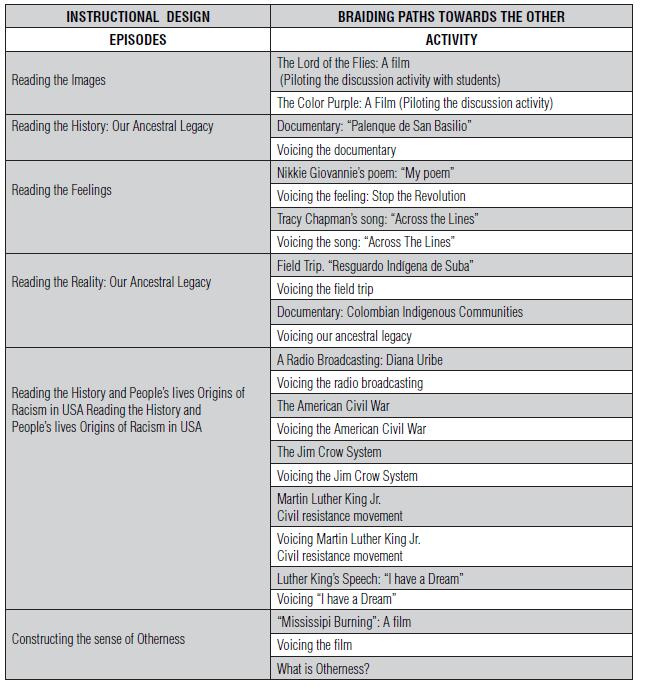

The pedagogical activities of the intervention plan were organized according to the texts that were to be analyzed during English classes. These activities were named “episodes”. Table 1 illustrates the episodes implemented in this research experience.

Each episode interrogated students’ prior conceptions and generated knowledge through specific activities that developed a view of world which is not ethnocentric. These activities were designed following the instructional method selected.

Dialogue played an important role in engaging learners as active participants in their learning process. Wink (2005) defines dialogue as: “communication that creates and recreates multiple understandings. It moves its participants along the learning curve to that uncomfortable place of relearning and unlearning. It can move people to wonderful new levels of knowledge; it can transform relations; it can change things” (p. 42).

The Instructional Method

Language teaching from Critical Pedagogy requires a methodology that involves questioning assumptions, beliefs, and values and considering multiple points of view in order to make possible a more inclusive world where individuals act upon their convictions. With the purpose of prompting the dialogue in each one of the episodes of the instructional design, the Creative Reading Method by Alma Flor Ada’s (1988) was applied; it combines real life situations and students’ experiences. This instructional method consolidates an integrated model in which learners’ knowledge is taken into account in foreign language learning by discussion and debate concerning the social, historical, and cultural issues immersed in each one of the episodes of the instructional design. Ada (1988) organizes her method into phases in order to give an idea of the different purpose of each phase.

First, the Descriptive Phase is used to ascertain the comprehension of the text and its concepts. Ada (1988) pointed out that “these are the types of questions for which answers can be found.” (p.100) Initially, the texts were analyzed and discussed focusing on a literal reading with questions like where, when, and how some facts happened. These questions allowed the learners a global comprehension of the events that occurred in the texts.

Second, the Personal Interpretive Phase invited the students to deepen their analysis of the texts by grounding the knowledge in the personal and collective students’ voices constructed through the discussions. Initially, the students have a moment to interact individually with the texts, and then they engage in a dialogue among the class group, bringing in their own personal experiences. Ada (1988) stated “students are encouraged to relate it [the text] to their own experiences and feelings” (cited in Cummins, p.1)

Third, the Critical Multicultural Anti-Bias Phase is used to promote critical reflection and anti-bias awareness. Ada (1988) has expressed: “as they gain the power to think through issues that affect their lives, they simultaneously gain the power to resist external definitions of who they are and to deconstruct the sociopolitical purposes of such external definitions” (cited in Cummins, p.2) Here, the students were encouraged to assume positions towards the texts. This phase prepared students to assume a self-definition in regards to the construction of the concept of Otherness.

Fourth, the Creative Phase is used to promote transformative attitudes. The learners critically analyze causes and possible solutions. Ada (1988) has mentioned: “This phase can be seen as extending the process of comprehension insofar as when we act to transform aspects of our social realities we gain a deeper understanding of those realities” (cited in Cummins p.2). The student’s voices bear the concrete actions that they decided to highlight from the issues discussed. During this phase they acted in the real world which empowered them to challenge relations of power existence in the society. Thus, in this research experience students generated interpretations and analyses of what is behind power relationships as a way to understand the political, social, and economic issues that exist in the world. They also analyzed the different human relations and possible solutions to political and social problems.

Findings

The analysis of the data was based on the grounded approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) because it was done through a systematic and constant comparison between the data collected and its analysis in order to support the theory that emerges from the data.

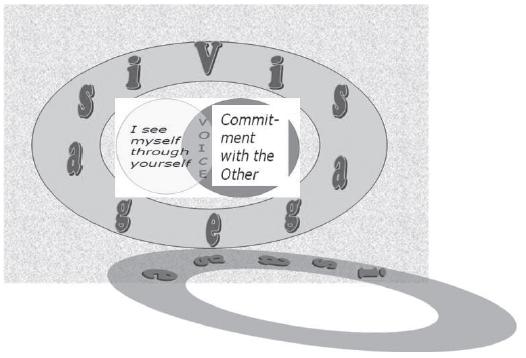

Through the development of the axial coding, the process of relating the categories and concepts to each other from and inductive and deductive way (Strauss, & Corbin, 1990), a core category called Visage emerged from the data. Visage is the face-to-face meeting, the encounter with the Other. From this category of Visage two subsidiary categories also emerged entitled “I see myself through yourself” and “Commitment with the Other”.

The first subsidiary category “I see myself through yourself” is subdivided into “Voices of knowledge” and “Voices of Stepping into somebody else’s shoes”. The second subsidiary category “Commitment with the Other” is subdivided into “Voices of Denouncement” and “Voices of Responsibility”. These voices are different for both subsidiary categories, because each voice represents a set of meaning to which students related and responded to a specific moment. For instance, “Voices of Knowledge” represents the beginning of this process that is followed by the second voice, “Voices of stepping into somebody else’s shoes”. This second voice is followed by the third, “Voices of Denouncement”, in the same way the third voice is followed by the fourth, “Voices of Responsibility”, which is a progression of the third one.

As stated by Strauss and Corbin: the core category must be the sun standing in orderly systematic relationship to its planet (1990). From this perspective, despite each subsidiary category standing by itself, they have a relationship among themselves and collectively relate to the core category of Visage because they are surrounded by the broad phenomenon that I found during the analysis of the data. Diagram 1 illustrates the connection and interdependence of the core category and the two subsidiary categories.

Visage

The core category of Visage emerges from the data reflecting the process that is carried out by students to construct the sense of Otherness. This visage is presented in students’ voices and was strengthened through the research experience and the subsidiary categories. Levinas (2006) established that the Other is recognized by me as a visage. When I see this visage, I see it in a mirror: “The self and the other are in some sense mirror images of each other, each different yet somehow the same and, therefore, connected by their reflection” (n.p.).

At the same time, the construction of the sense of the Other is a process similar to a braid. African descendants have given much importance to braids throughout history, and during the slavery era in the USA some communities braided on women’s heads paths necessary to escape slavery. This is why this braid corresponds to the story line that students raise through their voices. Each one of the different voices represents a lock of hair to be braided. The braid is the sense of Otherness built by the students.

I See Myself through Yourself

The philosopher Emmanuel Levinas has stated: “the self cannot exist, because it cannot have a concept of itself as self, without the Other” (as cited in Onbelet, n.d.). The self requires the other to bring meaning to its existence, and conversely, the other also requires the self to make sense. From this point of view, only with the Others I can support my existence; I need the Others to be; that is, I see myself through my relation with Others.

Voices of Knowledge

Through these voices the barrier of indifference was broken as Freire (1993) mentioned, students began to “acquire the object” and start the adventure to really know about the issues addressed. The next excerpt illustrates this aspect. It belongs to the transcription of the fourth session, based on the episode “Reading the People’s Lives: the History of Racism in the USA”. Students answered the questions corresponding to the descriptive phase of the instructional design. They were asked what actions they remembered about the Ku Klux Klan and answered as follows:Voices of Knowledge Through these voices the barrier of indifference was broken as Freire (1993) mentioned, students began to “acquire the object” and start the adventure to really know about the issues addressed. The next excerpt illustrates this aspect. It belongs to the transcription of the fourth session, based on the episode “Reading the People’s Lives: the History of Racism in the USA”. Students answered the questions corresponding to the descriptive phase of the instructional design. They were asked what actions they remembered about the Ku Klux Klan and answered as follows:

St. 17: They fought Negroes. They had a “failosofy”

T: Philosophy. Which was it? Do you remember? Speak aloud.

St. 9: The black, indigenous, and Jewish races. They were impure races.

T: Who wants to add anything in regard to it? (I point out the board)

St. 1: Everybody is equal. The black race’s rights.

St. 17: Golpeaban negros. Tenían una “failosofy”

T: Philosophy. ¿Cuál era esa? recuerdas algo. la raza negra, indígena, judíos eran razas impuras.

T: ¿Alguien más quiere agregar algo con respecto a esto? ¿O con lo que no se ha dicho acá?

St. 1: Todos son iguales. Los derechos de la raza negra

“Voices of Knowledge” were the first step in possessing empowerment to point out the power exerted by dominant cultures. It is explained through the discussion as student 11, instead of continuing to exemplify the characteristics of the Ku Klux Klan, states: “Todos son iguales”. In some way, his voice rejected the actions of the organization and he clamored for the status of equality. He rejected the Ku Klux Klan practices by comparing them with a system of values. This is what Wink (2005) called “reinventing the object being known” (p. 87).

This is important in a perspective of critical education because knowledge must be made meaningful before it can be made critical. Most important, these voices signified that students began to identify how dominant cultures define themselves as different from subordinate cultures, and how these dominant cultures exert a process of cultural imperialism in order to relegate some subordinate groups into oblivion.

Voices of Stepping into Somebody Else’s Shoes

Encouraging students to speak about their own experiences and feelings led them to develop their sensitivity. I consider it a key step to constructing Otherness. It also helped them to understand that “true learning occurs only when the information received is analyzed in the light of one’s own experiences and emotions” (Ada, 1988, p.104). The personal interpretive phase of the intervention plan aimed to stir these voices. Thus, to heighten the comprehension of a text, a picture was very useful. Students expressed through drawings how they supposed the poet felt about the situation (in the third episode: “Reading the Feelings: Nikkie Giovanni’s poem: My Poem”). In the next excerpt a student drew the woman’s position, her face, and the broken objects. The flowers and the pieces of paper reflected her sadness and solitude.

Notice in the picture above that the woman is very similar to an “emo girl”, which is some of the students’ style. Emo has been associated with a stereotype that includes being particularly emotional, shy, sensitive, and introverted. The picture can be interpreted as a way for students to express the message in the poem using elements of their inmediate realities.

Through drawings, the student´s voices are situated in a universe of shared meanings to interpret and articulate the character’s experience in the text. Precisely with the intention of providing students access to a critical discourse, they were guided to place themselves at an intersection of subjectivities facing the texts in such a way that it affected them and provoked reactions that revealed the forces behind their analyses, while engaging them in a dialect of self and the existing social power relations.

During the personal interpretive phase and by means of a real experience with the documentary, “We Are Raised in our Staffs of Authority”, produced by NASA-ACIN, the Colombian Indigenous Communities of North Cauca, and complemented with a field trip to the Indigenous Reservation of Suba, the students realized that forced displacement is a violation of human rights since land represents culture, traditions, and most importantly, identity. During this episode “Reading the Reality: Our Ancestral Legacy”, one student explained his perspective as follows:

If I were evicted from my house, I’d feel sad because I am accustomed to my life, and everything my mother has worked hard for would be taken away.

Yo me sentiría mal si me sacaran de mi casa porque estoy acostumbrado a mi vida y que nos quitaran todo por lo que mi mamá ha luchado.

Based on their own experience, students know all of what is implied to obtain material things. For instance, material goods acquire value because their parents faced a lot of difficulties obtaining them. In this way, the objects also represent identity and losing them is losing oneself.

The student’s voice expressed humans vulnerability when we are not recognized and when one’s own culture is attacked. The Others’ struggle became the students’ own struggle as it involved a history, a language, and a culture shared as individuals.

Here it is important to mention that listening to other students and stating one’s position in regard to these social and cultural aspects allowed students to reflect on their own attitudes towards the Others in the classroom, as some of them sometimes represented the dominant culture over some of their peers’.

St 9: Rig: This is what happens among us because, I mean, one sometimes feels discriminated against when dressed in slim-fit jeans, or something else and when you try to share with another group dressing other ways and you change your style because you are avoiding rejection. In some way, the group changed you.

T: In agreement with you are mentioning; are we discriminated against?

St. 9: Rig: As he mentions (referring to another colleague). By the attitude.

T: Okay, what else?

St. 14: Jh: By the beliefs, in what we believe. Zizas! By the way of behaving. By the way of getting dressed

St: 1: Js: For instance, by the music that you like, even.

St. 9: Rig: Eso es lo que pasa entre nosotros, porque por decir algo una veces uno se siente como discriminado cuando por decir uno se viste con el jean entubado o como sea; pero uno llega a un grupo donde va de otra forma y por no sentirse rechazado, el grupo como que lo cambia a uno.

T: Ahora, de acuerdo con lo que estás diciendo, nosotros, ustedes. ¿Somos, son discriminados?

St. 9: Rig: Por lo que dice él. Por la actitud.

St. 14: Jh: Por las creencias, en lo que creemos. Zizas! Por la forma de ser. Por la forma de vestir. Por ejemplo, hasta por el tipo de música que escuchamos

In the last excerpt participants understood that our essence as human beings is susceptible to discriminatory actions from Others. This issue is very important for building respect towards Others and it represents another lock of hair to be braided.

Commitment with the Other

With regard to this subsidiary category, Levinas (as cited in Eskin, 2000) points out that one must be vigilant to the call of the Other because the Others exist with us. Each of us hasveconstructed our existence in relation to Others who have determined in some way our projection in the world. They exist within diversity as we exist inside diversity, and understanding diversity is to understand the Others.

Magendzo (1996) has affirmed that first we need to recognize the Other as Other. Second, we need to assume a responsibility with the Other. In this sense, for this subsidiary category “Commitment with the Other”, I identified two Voices: “Voices of Denouncement” and “Voices of Responsibility”. Here, the critical multicultural anti-bias phase of the intervention plan aimed at building these voices.

Voices of Denouncement

This study considers the voice of marginalized people, those who by virtue of their differences from the dominant group have been disempowered. Their voice is robbed, as is their identity, sense of self, and sense of value. They need Others who hear them and who speak on their behalf.

Furthermore, Voices of Denouncement have to do with the students’ emergence as citizens. As citizens we must talk for ourselves and also for Others. In this way, the students situated social phenomena of Colombian indigenous communities in broad and complex meanings of oppressive political and social facts of life. It allowed them to interrogate their current situation by highlighting the forces of oppression behind it. The participants engaged by denouncing these traumatic events through their own voices:

St: 8 Ang: The government always wants to hide something from us. What really happens always camouflaged and the government is always right and the others are wrong, the others are to blame for everything and... (She is interrupted)

St. 9: Rig: The government wears a mask all the time.

St: 8 Ang: Que siempre el gobierno nos quiere ocultar algo. Que lo que en verdad pasa, siempre se camufla todo, y que ellos siempre son los buenos y que la culpa la tienen son los demás y que …

St.9: Rig: Viven con una máscara todo el tiempo.

VR3, D: 8-09-08, L292-295, T: 39:43-39:50, p.8, 9.

Furthermore, “Voices of Denouncement” have to do with the students’ immersion as citizens.

Students were guided step by step so they could reflect upon how knowledge needs to change from passive to transformative in such a way that it liberates them from silence and indifference. Students should have a spectrum of historical facts so they have an idea of the future. This is giving students the “language of possibility” mentioned by Giroux (as cited in McLaren, 2003, p. 46).

Building students’ sense of citizenship happened when they analyzed some articles from our Colombian Constitution. The trafficking of humans, the socioeconomic influences, the violence and injustice against displaced people and Afro Colombian people, the current indigenous communities’ situation, and the practice of kidnapping were denounced by students, like that of the next participant’s voice:

Article 13: The words in the National Constitution can seem nice, but if we compare them with the current situation in the country, we can observe that these words are only on a piece of paper. Freedom in Colombia has become a utopia. In the Colombian forests there are a lot of people who have been kidnapped. The government only refers to the political kidnap victims but who talks about the police officers, soldiers and peasants who were kidnapped? Nowadays, they are forgotten because they are not political kidnap victims. The government is only worried ending a war and risking a lot of innocent lives. It is a sad truth that in Colombia freedom of the press is restricted because the medium that denounces such a situation is considered terrorist and subversive.

Artículo 13: Las palabras en la Constitucion pueden parecer muy bonitas pero si las vamos a comparar con la situación real del pais, vemos que se quedaron solo en el papel. La libertad en Colombia se ha convertido en una utopía, en la selva se encuentran muchos secuestrados, muchos de los cuales el gobierno solo habla de los secuestrados politicos, pero que hay de los policias militares y campesinos que estan igualmente allí, de ellos no se acuerdan ahora que ya no quedan secuestrados politicos, el gobierno se dedica a librar una guerra y a arriesgar muchas vidas inocentes. Es triste pensar que en Colombia hasta la libertad de prensa esta restringida, pues el medio que se atreve a denunciar ya es tratado de terrorista y subersivo.

ECSO, St.YSPZ- Dat: 20-03-09

These voices are locks of hair because the participants stated how unequal relationships are being produced, and how these relations are interpreted as being suffered by individuals who live in a system of unequal economic, political, social, racial, and cultural relations.

For the purposes of this study, it is essential that the student’s voices reflect responsibility towards Others. This is something that Voices of Denouncement led them to achieve. When the student’s voices denounced those aspects of the dominant society that contribute to ethnic and cultural injustice, they were preparing themselves to assume responsibilities towards Others, as the next voices considered.

Voices of Responsibility

Part of the ethical role of teachers is to teach to their students that the solutions to social, political, and cultural problems, beyond being individual solutions, require a sense of “us.” In other words, some part of oneself is given in one’s relation with the Others.

In this way, the teacher needs to guide the students in the process of building their own sense of self, the ‘I’ of each student. This is what this research experience led to: the building of the sense of an ‘I’ in relation to Others and is what Voices of Responsibility supports. The next voice assumes responsibility since the students considered the need for change. Initially, the participants were aware of the vote as the best option to exercise citizenship and to defend human rights, as follows:

I need to share my knowledge with the people around me, giving them my point of view so that people can think it over, so that when they get older they can vote for one of our indigenous brothers and sisters. I can support indigenous people in their peaceful protests.

Compartir mi conocimiento con la gente que me rodea darles mi punto de vista, para que recapaciten para que sea mayor de edad votar por uno de nuestros hermanos indigenas. Apoyandolos en sus protestas pacificas.

RH:OAL, St. MELCF -Dat: 16-09-08

From a critical perspective, knowledge alone does not transform reality; only the conversion of knowledge into action can transform it. Reflecting upon our own attitude is the way to recognize the Other as Other. Only when we look into ourselves it is possible to feel responsible towards Others. From a perspective of Colombian citizenship, the citizens’ political action only has sense through self-recognition as part of a culture, the consciousness of the self through the selves.

St. 6: Yesd: Teacher, Colombia needs a change which must begin with us. How can we do it? By electing good leaders who really want to work for the country.

St. 6: Yesd: Profesora, es que Colombia necesita un cambio el cual debe empezar por nosotros, y ¿cómo hacerlo?, eligiendo buenos dirigentes que realmente quieran trabajar por el país.

VR6, D: 19-02-09, L 253-255, T: 70:13-70:17, p. 10.

This voice assumes responsibility since the student considered the need for change and expressed that it must come from us. Also, Magendzo (2006) considers that Otherness comes from us. Otherness is the result of active participation because Otherness cannot be exercised from passivity (translated by the author).

Visage

In the light of the concept of visage, the students need to elaborate some concepts before their encounter with the mirror image, the visage: the concept of recognition, the concept of the Other and the concept of action. Only at the end of the intervention plan were students asked what the concept of the Otherness meant. Some of their answers were:

Deducing this word, I believe that it is an euphemism of the word brotherhood through which we can tell and achieve the dream of living in the same space, one next to each other, without any consideration of race or social aspect. Undoubtedly, Otherness means to value the Other, but valuing him/her by his/her knowledge and attitude.

Deduciendo basicamente esta palabra, creo que es un eufemismo de la palabra hermandad, mediante la cual podemos decir y realizar ese sueño de vivir todos, uno al lado del otro, sin importar el color o aspecto social, sin duda otredad quiere decir tambien valorar al otro, pero valorarlo solamente por sus pensamientos y actitudes.

ECSO, St.YESDPZ- Dat: 29-03-09

This voice has the power potential not only to change the circumstances of minorities’ discrimination, but also the students’ understanding of life because they are able to analyze their individual and social existence to become free individuals.

The core category of Visage was built through the interaction among the two subsidiary categories. Students told how their voices guided them towards their construction of Otherness. The voices that constitute the locks of hair to be braided are grouped by the subsidiary categories and, at the same time, each subsidiary category is related to the other, which is the tying of the braid, and together they surround the Visage.

Discussion

Four different voices were identified in this study: The first voice identified was “Voices of Knowledge” which aimed at participants’ giving meaning to reality. It consisted of how the students understood that knowledge is culturally, socially, and historically related to power relations. They analyzed the way Others struggle daily. They named the dominant forms of power. In this sense, the students understood the importance to know, but especially how to use the knowledge to be subjects of history and make it possible to create a new society. It means that they did “an act of knowing” (McLaren, 2003, p.7) because they were active subjects constructing knowledge. It is also important to mention that through each one of the next three voices, knowledge became meaningful, critical, and finally, emancipatory for students.

Next, these voices were followed by the second voices identified, “Voices of Stepping into Somebody Else’s Shoes,” which allowed students to reflect upon Others’ situations and conditions and to be sensitive towards them. They felt similar feelings as Others experienced and saw the Others through themselves.

The third voice that emerged from the data was Voices of Denouncement. Through these voices, students denounced the oppressive social, cultural, and political facts throughout history. They condemned some situations that caused them injustice, segregation, and discrimination, among others. These voices clamored for justice and better living conditions for the voiceless. Also, the students participants in this research study analyzed the different factors that influenced the facts from the past to the present. Voices of Denouncement allowed them to be part of the world and be visible to history.

Through Voices of Responsibility students assumed responsibilities towards Others. They were aware of their role as citizens and the importance of having a voice to face current situations. Additionally, they changed their vision towards those who are different. They recognized that Others are similar to them because of their condition as human beings, but different from them also because of their unique character.

It is important to mention that the voices “I see myself through yourself” and “Commitment with the Other” were always permanent in the students’ as individuals but they were not aware of it.

Therefore, the students were progressively constructing the sense of Other. Most important lythey assumed commitments in their role as citizens. The capacity to see the Other and in seeing him/her becoming in some way responsible about his/her condition was a process followed by the voices, and supported by the core category: Visage.

Conclusions

The dialogue held by students in class represented a key aspect in the students’ determination of cultural and social subjects, which changed the perceptions of each other and defined them as individuals with beliefs, concerns, ideas, and empowering attitudes from the class scenario.

The English class was a means to enhance the students’ sensitivity towards cultural multiplicity. The students learned about the “experiences of the oppressed.” In this sense, education involving social justice and equality gives students reasoned arguments and provides the need to assume responsibilities as individuals.

It was also evident that the activities allowed them to express in diverse ways their impressions and emotions. Based on the results, students could see their capacity to draw, to organize information, to lead a group, to take a risk, and to assign and respect turn taking. As a result, there was improvement in their self-esteem and evidence of mutual acceptance.

References

Ada. A. F. (1988) Creative Reading: A Relevant Methodology for Language Minority Children. In L. Malave (Ed.), NABE’ 87. Theory, research and application: Selected papers (pp. 97-111). Buffalo: State University of New York Press.

Bergo, B. (2007). Emmanuel Levinas. Stanford University Encyclopedia of Philosophy Retrieved January 19, 2009 web site http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ levinas/#int

Cummins, J. (2001) Negotiating Identities: Education for Empowerment in a Diverse Society.

California Association for Bilingual education — CABE

Eskin, M. (2000). Ethics and Dialogue: In the works of Levinas, Bakhtin, Mandelshtam, and Celan. Great Britain. Oxford.

Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum. (Original work published 1970). In: Ibrahim, A. (Autumn, 1999). Becming black: rap and hip-hop, race, gender, identity, and the politics of ESL learning. TESOL Quarterly,Vol. 33 (3), 349-367.

Lacan, Ink. Origin of the word Otherness.Retrieved March 3, 2010, from http//www. lacan. com/

Lee, C. (2000). Signifying in the Zone of Proximal Development. In Lee, C. & Smagorinsky, P. (Eds.), Vy-gotskian Perspectives in Literacy Research. Constructin Meaning through Collaborative inquiry. (pp. 191-255) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levinas, E. (2006). The Face, Ethics, and God. Retrieved on January 15, 2009 from http://blogs myspace. com/index.cfm?fuseaction=blog.view&friendId =82758112& blogId=135 952 982

Magendzo, Abraham. An Ethical-Political Sustainability for Citizen Education. CIVNET: Center for Civic Education, International Conference of Civic Education in an Age Worldwide Migration, Munster, Germany. 17 October 2007. Conference.

Magendzo, A. (2006). Diseño y Elaboración de Currículum una tarea de Negociación de saberes y un juego de poderes, Retrieved September 10, 2008, from http://mt. educarchile.cl/ mt/ amagendzo/ archives/2006/04/diseno_y_elabor.html

McLaren, P. (2003). Life in Schools: An Introduction of Critical Pedagogy in the Foundations of Education. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Myers, M. (1997). Qualitative Research in Information Systems. Retrieved June 26, 2009, from http:// www.misq.org/discovery/MISQD_isworld/index. html#Introduction.

Onbelet, L. (n.d.) Imagining the Other: The Use of Narrative as an Empowering Practice. In McMaster Journal of theology and Ministry. Retrieved September 10, 2008, from http:// www. mcmaster. ca/mjtm/3-1d.htm

Pennycook, A. (2001) Critical applied Linguistics: A Critical Introduction. London: Lawrence E r l b a u m Associates Publishers.

Quintero, L. (2006). School Literacy Practices Closer to Home: The New Challenge of Literacy Learning. CALJ, (8), 216-227.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory, Procedures and Techniques. London: Seige Publications.

Wink, J. (2005). Critical Pedagogy. Notes from the Real World. New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Firstly, I must say that I learned a lot. Most important, I believe that the most relevant things about myself were the attitudes and perspectives that I had towards the indigenous people, because I generalized in regard to behavior, thought, style of dressing, knowledge, when I know that each individual is unique in even one or two aspects; but always unique.

As for the wide existing diversity, there is something that renders us equal, the fact of being the same race, the human race, with a lot of defects, but with all the tools to correct these defects.

Besides, we must consider the existing Colombian multiculturality because, as I say, we are a country with a variety of races, cultures, religions and existing accents. In Colombia we find one thousand from the paisa, the costeño, the valluno to the cachaco, from our native ancestral legacy to descendants of Africa.

Also, I can say that one of the issues that caught my interest and my attention was in regard to history and the most significant changes in the USA in relation to racism, discrimination, and slavery.

In another way, it is important to recognize the other because as people we are equal, and need to feel honest together, because the other can not be excluded or separated by our way of thinking, dressing, talking, acting or simply living. It is very important for us to feel equal as a human race for our lives in society.

Lastly, I want to say that thanks to this project I understood the others’ suffering because of some people’s grotesque thoughts, those who believe they are superior to others- when we know that everybody is a human being.

Por ultimo, podría decir que gracias a este proyecto entendi y comprendi el sufrimiento que han tenido que soportar demaciadas personas gracias al grotesco pensamiento de algunos seres humanos, creyendo ser superiores, sabiendo aun que también son seres humanos.

En primer lugar debo destacar que aprendí demasiadas cosas con este proyecto, lo más importante y creo que lo mas notable en mí, fue la actitud y perspectiva que tenía frente a las personas afrodesendientes e indígenas en general, pues creía y generalizaba en cuanto a formas de ser, pensar, vestir o actuar, sabiendo aún que cada ser sobre el planeta es unico e inigualable, ya sea en uno o dos aspectos, pero simplemente será único.

Y de la inmensa diversidad existente, hay algo que nos vuelve iguales el hecho de ser la misma raza, la raza humana, con miles de defectos pero con todas las herramientas para corregirlos.

Notamos ademas la multiculturalidad existente en Colombia, ya que diria yo, somos de los paices con más variedad de razas, culturas, religiones o acentos existentes, en Colombia encontramos de 1000, desde el paisa , el costeño, el valluno, hasta el cachaco, desde nuestros antepasados indígenas hasta personas afrodescendientes.

También puedo decir que de los temas que más me interesaron y más llamaron la atención fue lo relacionado con la historia y los cambios más significativos que ha tenido estados Unidos en cuanto al racismo, la discriminacion, y la esclavitud.

De otra manera es importante reconocer a la otra por el simple hecho de sentirnos iguales, de hacernos sentir mutuamente justos, de no ser excluidos o separados por nuestra forma de pensar, vestir, hablar, actuar o simplemente vivir, es claramente necesario sentirnos iguales en cuanto a raza humana para la buena vida en sociedad.

ECSO, St.ALECN- Dat: 29-03-09

Métricas

Licencia

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/