DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.84Publicado:

2010-07-01Número:

Vol 12, No 2 (2010) July-DecemberSección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónA guided reading of images: a strategy to develop critical thinking and communicative skills

lectura guiada de imágenes: una estrategia para desarrollar pensamiento crítico y habilidades comunicativas

Palabras clave:

Pensamiento crítico, taxonomía de Bloom revisada, lectura visual, alfabetización visual, pensamiento crítico en un contexto de inglés como idioma extranjero y programa de lectura guiada de imágenes (es).Palabras clave:

Critical thinking, revised Bloom’s taxonomy, visual reading, visual literacy, critical thinking in an EFL context, a program for guided reading of images (en).Descargas

Referencias

Averinou, M., & Ericson, J. (1997). A Review of the Concept of Visual Literacy. British Journal of Education Technology. 28 4, 280-291.

Bamford A. (2003). The Visual Literacy White Paper. Brief overview. Commissioned by Adobe.

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. (1998). Introduction: Entering the Field of Qualitative Research. In N.K. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

Dewalt, K. Dewalt, B. & Wayland, C. (1998). Participant observation. In H. Russell Bernard (Eds.). Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology. (pp. 259-300). Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

Dondis, D. (1973). A Primer of Visual Literacy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing Teacher Research: from Inquiring to Understanding. Canada: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Gheith A. (2007). Developing Critical Thinking for Children through EFL. Learning.Cairo (Egypt). Retrieved November 14, 2008, from spirit-Of-inquiry. concordia.ca/presentations/gheith

Guthrie, J. & Rinehart, J. (1997). Engagement in Reading for Young. Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, (40) 6, 438-446 March [EJ 547 197].

Hopkins, D. (1995). A Teachers' Guide to Classroom Research. Buckingham, Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Hubbard, R, & Power, B. (2003). The Art of Classroom Inquiry: A Handbook for Teacher-Researchers (Rev. Ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Meek, M. (1988) How Texts Teach what Readers Learn. Stroud, England: Thimble Press.

Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Norris, S. & Ennis, R. (1989) Evaluating Critical Thinking. In R. J. Schwartz & D. N.

Ormond, J. E. (2003). "Educational Psychology: Developing Learners" 4th Ed. Merrill Prentice Hall.

Overbaugh R., & Schultz, L. (2008). Retrieved November 3, 2008, from http://www.odu.edu/educ/roverbau/Bloom/blooms_taxonomy.htm

Paul, R. (1993). Critical thinking: What Every Person Needs to Survive in a Rapidly Changing World.(3rd ed.), Rohnert Park, California: Sonoma State

University Press.

Paul, R. & Elder, L. (2005).The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools. Dillon Beach CA; Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Pantaleo, S. (2005). Young Children Engage with the Metafictive in Pictures Books. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 28 1.

Pithers, R. & Soden, R. (2000). Critical Thinking in Education: A Review, Educational Research. 42 3, 237-249.

Seels, B. (1994). Visual literacy: The Definition Problem. In Moore D.M. & Dwyer F. (Eds.) Visual literacy: A Spectrum of Visual Learning. Englewood Clifts, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Seliger, H., & Shohamy, E. (1990). Research design: Qualitative and Descriptive Research. In Second Language Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sinatra, R. (1986). Visual Literacy Connections to Thinking, Reading and Writing. Springfield, I.L.: Charles C. Thomas.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2010 vol:12 nro:2 pág:72-86

Research Articles

A Guided Reading of Images: A Strategy to Develop Critical Thinking and Communicative Skills

Lectura guiada de imágenes: una estrategia para desarrollar pensamiento crítico y habilidades comunicativas

Marisol Sarmiento Sierra

English teacher Colegio Morisco, Bogota, Colombia E-mail: marisol_sarmiento@hotmail.com

Abstract

This article describes the effects of a strategy aimed at helping students develop critical thinking and communicative skills by means of a program for guided reading of images using the questioning technique in an EFL context. Many teachers are not prepared for the education of critical thinkers as part of their curricular work. This is a qualitative descriptive research study carried out with third graders from a public school in Bogotá, Colombia in which field notes, artifacts, and questionnaires were used as data collection instruments. The study showed that the program activated children’s mental processes to allow them to move from basic to higher levels of critical thinking while communicating their thoughts in Spanish as well as using vocabulary in English. This strategy could be used by teachers of different disciplines.

Key words: Critical thinking, revised Bloom’s taxonomy, visual reading, visual literacy, critical thinking in an EFL context, a program for guided reading of images.

Resumen

Este artículo describe los efectos de una estrategia encaminada a ayudar a los estudiantes a desarrollar pensamiento crítico y habilidades comunicativas por medio de un programa de lectura guiada de imágenes que usa la técnica de pregunta en un contexto de inglés como idioma extranjero. Muchos docentes no están preparados para la formación de pensadores críticos como parte de su trabajo de innovación curricular. Esta investigación cualitativa y descriptiva se implementó con estudiantes de tercer grado en un colegio público de Bogotá-Colombia, en la cual notas de campo, producciones escritas y cuestionarios fueron usados como instrumentos de recolección de datos. Las evidencias muestran que el programa activó el proceso mental de los niños lo cual les permitió moverse de niveles básicos hacia niveles superiores de pensamiento crítico, mientras comunicaban sus ideas en español e incluían vocabulario en inglés. La estrategia podría ser usada por docentes de diferentes disciplinas.

Palabras clave: Pensamiento crítico, taxonomía de Bloom revisada, lectura visual, alfabetización visual, pensamiento crítico en un contexto de inglés como idioma extranjero y programa de lectura guiada de imágenes

Introduction

Based on modern educational needs and as part of their institutional curricular innovation, a great number of schools have included critical thinking as a skill that must be taught in all subjects; however, many teachers do not know how to teach critical thinking. In public schools, this task could especially represent a complex challenge for English teachers due to a great number of their students having learning difficulties and poor development of linguistic skills in their mother tongue. Such drawbacks influence the learning of English as a foreign language.

Taking into account that our world is surrounded by images, students should learn to construct meaning from any type of image as part of their literacy practices which could help develop critical thinking skills. Averinou and Ericson (1997) suggest that most children can read visually, but in a superficial way. Thus, it is necessary to consider a program that includes visual aids as a tool that empower children to critically read a visual text, and at the same time motivate them to write their perceptions in the language they are learning

This qualitative descriptive study, conducted in a public school in Bogotá, Colombia, focused on the promotion of children‘s critical thinking skills (based on the Revised Bloom’s taxonomy) by means of a program for guided reading of images. The program allowed children to participate in activities that led them into deep thinking and helped them develop communicative skills in an EFL context.

Through this research article the reader will see how third graders that initially read images in a superficial way were able to move beyond the literal reading of images as a result of activating their mental processes to shift from lower to higher levels of critical thinking. Additionally, the students’ communicative skills both in English and Spanish showed gradual growth.

Theoretical Perspectives

Critical Thinking

Paul and Elder (2005) consider critical thinking “as a process by which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them” (p. 1). This consideration is accurate in the sense that, by nature, children have great potential in their thinking, and what they need is a strategy that empowers their thinking to help them categorize information to understand and produce more elaborate ideas. At this point Pithers and Soden’s (2000) assertion should also be considered, which states that critical thinking is more than a mental activity, given that during this process it is necessary to identify how the thinking is influenced by context and culture.

From my perspective, the affective disposition should also be included in such processes, considering its implications on children’s learning. In fact, this issue implies motivation which in turn boosts a teaching learning process.

To explore how the activities proposed in the program for guided reading of images could have children move through different levels of critical thinking, the revised Bloom’s taxonomy was used. Below, you will find information about this taxonomy and some considerations in regards this research.

Revised Bloom’s taxonomy (RBT)

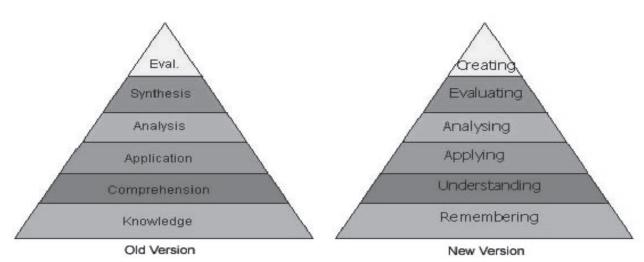

During the 1990’s, Anderson, a former student of Bloom’s, led a new assembly which met for the purpose of updating the Bloom’s taxonomy, hoping to add relevance for 21st century students and teachers. The revision of Bloom’s taxonomy included significant changes in three aspects: terminology, structure, and emphasis. Graphic 1 shows the differences between the original Bloom’s taxonomy and the revised version.

Notice that the most basic step—knowledge or remembering—is the foundation of the pyramid. The higher you go up the pyramid, the more advanced your knowledge becomes. According to Paul (1993), some critics of Bloom’s Taxonomy’s cognitive domain admit the existence of the six categories, but question the existence of a sequential, hierarchical link. Other critics consider the three lowest levels as hierarchically ordered, but the three higher levels as parallel.

I propose, instead, a spiral as a graphic way to represent the levels of critical thinking, given that it allows visualizing the cyclical character of the thinking activity (See Graphic 2). It might also reflect the advancement from one level to another in which the intellectual behavior activity is not fixed in a specific place. Additionally, this visual representation might reflect that intellectual behavior goes from basic towards complex levels or stages of critical thinking. Another possible way of decoding this graphic is the interaction among levels of critical thinking; in fact, if each level had a different color and the points of contact between one level and another included a darker tone, the reader could easily interpret the levels’ overlapping areas.

Visual literacy

Bamford (2003) considers some aspects that enrich the concept of visual literacy and pave the way for better use of images in the educational field. According to Bamford, visual literacy “involves developing the set of skills needed to be able to interpret the content of visual images, examine social impact of those images, and to discuss the purpose, audience and ownership. It includes the ability to visualize internally, communicate visually and read and interpret visual images.” The elements included in this concept could allow children to obtain a better understanding of an image, which comes in handy for this research work. For example, when students are guided to analyze and interpret an image framed in a cultural context, and are able to infer its purpose, the mental processes they use might allow them to internally visualize that image.

Visual literacy and critical thinking in an EFL context

Visual literacy and critical thinking skills development might offer new ways to facilitate and motivate communication in a foreign language. According to Guthrie and Rinehart (1997), there is a need to place literacy learning, just as critical thinking skills, within content areas in order to drive learning and increase both literacy ability and knowledge.

One research work that supports these ideas was conducted by Gheith (2007), for whom foreign language learning by children is more than a communicative process or mechanical activity. It becomes a critical and original production. According to Gheith, children use the foreign language to communicate, not just to learn it. When reading images, children assume an active role due to the fact that they locate, evaluate, organize, synthesize and present information by transforming it into knowledge in the process. This assertion provides an appropriate framework for what was done in the present research; nevertheless, to succeed in such processes it was required that specific conditions that promote a learning process featured by the critical thinking skills development be provided.

After having mentioned critical thinking and visual reading in connection to the learning of English as a foreign language as the main constructs behind this research work, and having remarked on some internal and external aspects that influence such processes, the program designed for this research work will be presented.

A program for guided reading of images

In this program activities that include different kind of images were designed to have students read visually, then think and answer questions that led them to experience different levels of critical thinking, moving from lowest to highest. The activity was called “reading images together” and was aimed at children. Such processes are understood by Dondis (1973) and Seels (1994) as the way of building meaning from images. These researchers stated that visual literacy results from a system for expressing, recognizing, understanding, and learning visual messages that are negotiable by all people. The “creativity time” section included activities that allowed students to produce drawings and/or signs. Pantaleo (2005) considers that children’s visual representations express their reading experiences and literacy development. Most of the activities aimed at writing were developed in order to allow children to organize and express their ideas.

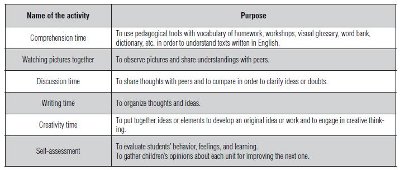

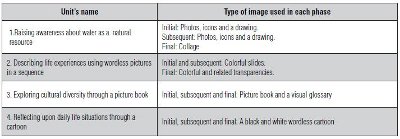

The program includes four units made up of workshops. Every topic included activities planned and named (See Table 1) according to specific objectives. Taking into account that workshops were written in English for facilitating students reading comprehension, many related icons, pictures, and a visual glossary were included. Each workshop contained activities that allowed students to work at three phases of critical thinking skills namely: initial, subsequent and final. Each phase incorporated two levels of the revised Bloom‘s taxonomy. Table 2 displays the units’ distribution.

Children watched different kinds of images to understand what they expressed while guided through questions posed by the teacher which were based on the revised Bloom’s taxonomy. At the same time, pupils carried out activities at their own pace to develop critical thinking skills.

Methodology

This study is framed under a qualitative research given that it emphasizes on the process and the meaning that people assign to different phenomena (Denzin and Lincoln, 1998). This study aimed to answer the following questions:

- What role does the program for guided reading of images play in the promotion of 3rd graders critical thinking skills?

- How do students use images to communicate in English?

To answer the questions a program was designed to identify and analyze the evolution of third graders ‘critical thinking skills development in an EFL context.

Context

This research was conducted with third graders of the morning shift at a coeducational public school located in the 10th Zone of Bogotá, Colombia. Preschool and primary courses received only one hour a week of English as a foreign language; however, for conducting this research third graders received two hours a week. The school promotes meaningful learning and the Languages Department focuses on the communicative approach.

Participants

In regards to the participant selection three reasons influenced decision-making: first, the lack of opportunities the pupils had for developing a regular L1 literacy process; second, low achievement in most of the students’ academic reports in comparison to other pupils of the same level due to unfortunate educational experiences in their three years of schooling; and third, the low level of motivation students showed towards the learning of a foreign language during the diagnostic phase.

This study was carried out with 34 third graders between 8 and 11 years old whose families belong to the working class. Many of the students did not have a person at home who supported them in their academic process and were alone most of the time. Such aspects and their economic conditions limited the possibilities for asking parents to buy English material; therefore, photocopies and visual aids became the main resource for implementing the project. In the diagnostic phase, third graders described pictures in a superficial way, and though they were asked to try to find more than the evident, they had difficulty understanding what the images expressed. Such information served as a basis to design a program whose activities enabled children to develop critical thinking and gave the foundations for exploring indepth the meaning of images.

The researcher

My role in this study was as a participantobserver. I was the researcher and also the English teacher. Merriam (1998) states that simply observing without participating in the action may not lead to complete understanding of the activity. Therefore, as a teacher I designed and guided a program and as a researcher I observed and analyzed its effects on the subjects’ skills development.

Data collection instruments and procedures

Students’ development of critical thinking skills and the use of images and their different forms of communication were registered in three instruments: artifacts, questionnaires and field notes.

Artifacts

Ar tifacts were mainly homework and workshops in which children completed varied activities that were collected at the end of the class and that became the main source for analyzing and describing the process in which students could attain different levels of critical thinking (See Appendix 1). Hubbard and Power (2003) state that the work done by students as part of their schoolwork can be used as valuable data.

Field notes

Field notes were taken during the class while students were developing activities that required more concentration during individual or pair work. Then, they were complemented after the class to avoid the loss of important details. According to Hopkins (1995) field notes are a way of reporting observations, reflections and reactions to classroom problems. The advantages they provide are first-hand descriptive information, help in relating incidents, and help in exploring emerging trends.

Questionnaires

In order to validate the data analysis, the questionnaire information was complemented with artifacts and field notes. Students completed questionnaires at the end of each of the four units, and that information was used to improve the next workshops. The questionnaires allowed students to do a self-assessment about their behavior and learning process. Additionally, they included blank spaces for children to justify each one of their answers in order to help them give more explicit information (See Appendix 2). Selinger and Shohamy (1990) state that questionnaires help collect data on phenomena that are not easily observed including attitudes, motivation and self-concepts.

Ethical issues

Consent forms were submitted explaining the intentions of this study and the possible outcomes that could benefit students, then, after presenting ethical issues and the responsibility to preserve the anonymity of the participants, these consent forms were signed by the school’s principal, the morning shift coordinator and the third graders’ parents.

Findings

I used two types of triangulation as proposed in Denzin’s model (cited in Freeman, 1998). First, data triangulation consists of using several sources of data in which information is obtained from different participants at different moments in order to provide credibility to the research. The second type was a methodological triangulation which implied the inclusion of multiple ways to collect data. Three instruments provided information that reflected the events of this particular context: artifacts, questionnaires ,and field notes. Validity was provided by data triangulation of information taken from writing samples, the students’ responses, opinions and suggestions registered in questionnaires, and from my own observations.

Motivator to explore images in the search for meaning by different means

The program for guided reading of images became a motivator when it influenced the students’ desire to explore images and helped children complete the tasks proposed in the workshops to understand the meaning conveyed in the images. Furthermore, it turned activities into something challenging, exciting and meaningful for students as it brought about students’ engagement in the class work.

Ormond (2003) states that motivation impacts students’ learning and influences the way they learn due to its direct behavior toward particular goals. It also enhances cognitive processing that leads to improved performance. Based on this description, the program for guided reading of images had such a positive motivational and rational influence that it induced children to undertake mental activities in order to explore images in the search for meaning.

The following sample taken from Unit 1, raising awareness about water as a natural resource, evidences motivation and engagement:

MdR said: “A mi me gusta todo porque es chévere” Pac, said simultaneously: “A mi también”… Val replied “!Pues todo!”YH complemented these commentaries saying: “!Uyh! A mi me gustó los dibujos y pegar.” Another student replied: “A mi lo del cuento” (Field Notes SEP 09).

MdR said: “I like everything because it is very nice” Pac, said simultaneously: “ To me also “... Val answered: “Well, all was nice! “ YH complemented saying: “Uyh! I liked the drawings and to stick “. Another student answered: “To me that thing about the story!” (Field Notes SEP 09).

Motivation also influenced children to undertake mental activities in order to explore images in the search for meaning, in this case through a process called imagery (production of pictures in the mind):

“Lo que pasa es que los dibujos se mueven, como que son de verdad” and a classmate replied:”!Sí, eso!” (Field Notes SEP 09).

“What happens is that the drawings move, as that they are really” and a classmate replied: “ Yes, that!” (Field Notes SEP 09).

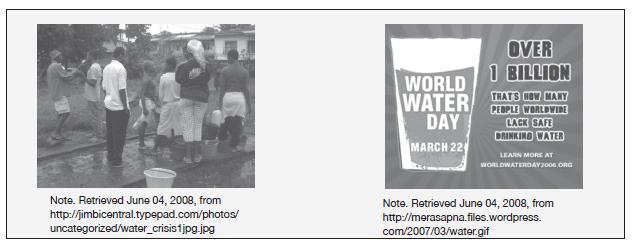

The following excerpts are comments related to the search of meaning of two related images: A photo of Buea, Cameroon, Africa, inwhich people discuss water problems and a poster that shows a message for World Water Day.

After a peer discussion activity, students concluded that the photo showed poor and displaced people, and remarked the importance of correct use of water. The student wrote in Spanish and included words in English (Bold). (Field Notes JUL 29).

“Que cortaron el water a unas people que son pobres que viven en el choco tienen que recolectar water tienen que sacar water del lavadero” (ART JUL 29).

[“That the water was cut to a few people that are poor that live in the Chocó-Colombia they have to gather water have to extract water of the pool”] (ART JUL 29)].

Activator of the construction meaning in the development of critical thinking skills

The agent is the program for guided reading of images and it caused the children to activate or accelerate mental activity in order to be able to build meaning from images and to develop critical thinking skills.

Taking into account that critical thinking is a complex process that is developed step-by-step, this process was divided into three subcategories to allow a more detailed and organized manner of observing the gradual development of students’ critical thinking.

Initial phase: Organizing information and ideas to gain insight from words, images and/or signs.

In this phase students organized information and constructed meaning by means of observation. Additionally, they developed the intellectual behavior of remembering and understanding. Students’ productions evidenced the creation of signs, and from this perspective, the guided reading of images implied the understanding and creation of semiotic elements. During some activities students interpreted and created signs that were a means for communicating their synthesis of ideas from the reading of images.

When students organized ideas and information they could recognize and build meaning behind words, images and signs, and such abilities positioned them in the initial phase of critical thinking.

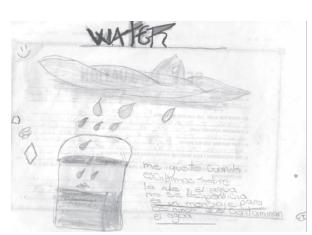

In this drawing, a student first organized information then represented the way they gained insight of words and images as presented in Unit 1, in which a drop and a bucket were included in different workshops.

Subsequent phase: Interpreting and drawing inferences

In this phase, children processed information acquired from more detailed observations of images and worked on reasoning. Their intellectual behavior allowed them to advance in their critical thinking skills development. The program for guided reading of images activated the students’ critical thinking skills of applying and analyzing. Notice that in the subsequent phase of critical thinking, the readers’ prior knowledge and their level of understanding textual information influenced their reasoning.

Every time we make predictions, judgments or draw conclusions, we are inferring. The best way to make inferences during visual reading is to have students discuss the meaning conveyed in images.

One material used was a picture book that tells how people in Colombia (South America) and in Lebanon (Western Asia) celebrate when a child’s tooth falls out. The book includes images and a short text in English that was read by students using a related visual glossary designed for facilitating reading comprehension. Two children inferred:

“Aprendí otra forma de celebrar.”

“I learned another way to celebrate.”

“En todo lado no hay las mismas costumbres.”

“Everywhere there are not the same customs.”

(QUEST NOV 18)

Final phase: Critical visual reading comprehension and creating at a complex level

Here students worked with gathered information and the meaning inferred from written texts and images used in the workshops. In the final phase students worked at evaluating and creating. When evaluating meaning of images, students needed to justify their decision. When creating, they generated new ideas, products or ways of viewing things.

After constructing meaning of images, they could generalize and value the power of ideas in regards to deciding on well -considered choices and opinions; moreover, they could infer about implications. Children‘s productions represented their critical visual reading comprehension when judging, valuing, creating and even when illustrating, as a means to complement their ideas (see Appendix 4).

As a wrap up, students chose from a set of pictures the most representative image in order to use it in a future save water campaign at school. One student chose the image of a faucet with falling drops of water, and then drew a woman closing a faucet in order to save water that was dropping on the floor. Additionally, she wrote the message she wanted to express with the drawing. Another student also drew a faucet with falling drops and included a container to collect it (Field Notes AUG 22).

Students’ drawings represented their critical visual reading comprehension and creating at a complex level. They not only generated a new way to invite people to save water, but presented a point of view. Additionally, children could understand the hidden meaning in the set of images observed as a point of departure. When drawing, they had to think about implications; that is, they needed to plan a way to help any visual reader understand what they wanted to express.

Many students’ drawings revealed having been created by a guided visual reader working in a critical manner. In the revised Bloom‘s taxonomy, creating is an intellectual skill that corresponds to the highest level of critical thinking. Sinatra (1996) states that the creation of visual images suggests a particular message that is at the same level as the written word.

Image as a tool that encourages communication

Taking into account the use of images made by children during the activities proposed in the program, each time participants needed to communicate their thoughts they used images as a means to do so.

The most common way of communication while incorporating vocabulary in English was expressed through writing. Two reasons might explain this finding: first, students expressed their desire to develop English writing skills in the needs analysis; second, students needed to organize their thoughts in order to think critically about the meaning of images they had observed and the best way to do this was through writing.

In an activity called “writing time”, a child expressed what she observed in a set of five wordless related pictures using a word bank displayed on the board as:

“[Once upon on time una rooster is en fense and is sing and los children look and in with los children and lo children lo look and is friends and are veri hapi]” (Yolita, ART SEP 24).

Evidence revealed that images became a source of initial thoughts; also, students discovered that images helped them understand the topic. Moreover, images provided ideas and elements to be used in their written production.

“Observé las fotos las bí para escribir en inglés.”

“I observed the photos I saw them to write in English.”

(QUEST OCT 14)

The above excerpts showed that students read visually and critically and used images to complete the activities with the information obtained from those images. The creation of images and the invention of a story motivated by a program for guided reading of images showed that students observed images more than once and that those images were used by them as a tool. Indeed, images became a source of selfconfidence and an opportunity for taking risks to write. (See Appendix 3)

Third graders’ productions revealed that images encouraged them to communicate, learn and practice English. Meek’s (1988) says: “If we want to see what lessons have been learned from texts children read, we have to look for them in what they write” (p. 38).

Although students’ oral production was lower than the written one, images also helped develop their oral skills in English:

St. 1: “Es muy chevre hablar en inglés” (QUEST SEP 02).

St. 2: “ Blu, blu, blu …. The teacher asked “¿qué necesitas?” Mario replied! Un marker, ticher un marker!” (FN OCT 15).

St. 1: “Speaking English is so nice” (QUEST SEP 02).

St. 2: “Blu, blu, blu… Teacher asked: “What do you need?” Mario replied: “A marker, teacher a marker!” (FN OCT 15).

Discussion

Data triangulation and the emergent categories revealed connections among visual literacy, critical thinking and communicative skills development in two languages, which occurred almost simultaneously in trained visual readers. Moreover, such skills developments facilitated that children could build meaning from images in a complex level and acquire knowledge from different topics. Analyzed data showed cyclical and connected relations in students’ development of different skills as a constant.

Based on those findings, I noticed that when critical thinking and visual reading are used simultaneously they might pave the way to motivate students to enquire into new forms to learn English as a foreign language. They might also help overcome the gaps in the development of students’ skills like reading and writing in their mother tongue.

Taking into account that our globalized world is surrounded by images, the above findings evidenced a modern educational need: to highlight the place that should be given to images in school curricula. The program proved to be a useful way to read and to understand the information images bring forth, as much as any provided by a written text.

Having in mind the complexity and interrelation of mental processes, it became evident that the program entailed a balance between mental processes of the readers and their ability to communicate to others their visual comprehension. Likewise, the trained visual readers discovered in the image a tool that facilitates the process of oral and written communication, just like that of semiotic communication.

Finally, the results of the program demonstrated that the practice of having students participate actively in class and trusting students‘ abilities showed children might use complex mental activities which, based on Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, had for a long time been attributed only to older people.

Conclusions

If children are guided to analyze and to interpret meaning from different kinds of images framed in a cultural context and if they are able to infer a purpose, their mental processes can be activated to allow them to internally visualize an image. Such processes might contribute to the development of critical communicative and visual reading skills.

The program for guided visual reading included purposeful activities that allowed the English classroom to become a place to share, to discuss and to meaningfully learn and practice languages. Furthermore, the program facilitated the teaching-learning process, and it might offer advantages to educators of any subject of the school curricula.

Querying helped students infer, inquire, discover and organize their thinking; nevertheless, the critical thinking level attained by visual readers depends on the type of questions posed during a guided activity. Better results could be obtained if images and topics are related to students’ lives. Notice that meaning was built not only in light of what pictures showed or expressed, but also in the visual reader’s critical thinking level. In other words, the meaning of a message in an image is not found in the image itself, but in the reader‘s mind. This characteristic of critical thinking is presented by Norris and Ennis, (1989) as a “reasonable and reflective thinking that is focused upon deciding what to believe or do” (p. 18).

My contribution as a teacher-researcher was to show how the activation of children’s mental processes allowed them to understand a particular topic in English while they constructed knowledge. Additionally, the program motivated participants to read images critically as they developed communicative skills in Spanish and in English.

References

Averinou, M., & Ericson, J. (1997). A Review of the Concept of Visual Literacy. British Journal of Education Technology. 28 4, 280-291.

Bamford A. (2003). The Visual Literacy White Paper. Brief overview. Commissioned by Adobe.

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. (1998). Introduction: Entering the Field of Qualitative Research. In N.K. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

Dewalt, K. Dewalt, B. & Wayland, C. (1998). Participant observation. In H. Russell Bernard (Eds.). Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology. (pp. 259-300). Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

Dondis, D. (1973). A Primer of Visual Literacy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing Teacher Research: from Inquiring to Understanding. Canada: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Gheith A. (2007). Developing Critical Thinking for Children through EFL. Learning.Cairo (Egypt). Retrieved November 14, 2008, from spirit-of-inquiry. concordia.ca/presentations/gheith

Guthrie, J. & Rinehart, J. (1997). Engagement in Reading for Young. Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, (40) 6, 438-446 March [EJ 547 197].

Hopkins, D. (1995). A Teachers’ Guide to Classroom Research. Buckingham, Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Hubbard, R, & Power, B. (2003). The Art of Classroom Inquiry: A Handbook for Teacher-Researchers (Rev. Ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Meek, M. (1988) How Texts Teach what Readers Learn. Stroud, England: Thimble Press.

Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass Publishers.

Norris, S. & Ennis, R. (1989) Evaluating Critical Thinking. In R. J. Schwartz & D. N. Ormond, J. E. (2003). “Educational Psychology: Developing Learners” 4th Ed. Merrill Prentice Hall.

Overbaugh R., & Schultz, L. (2008). Retrieved November 3, 2008, from http://www.odu.edu/educ/roverbau/ Bloom/blooms_taxonomy.htm

Paul, R. (1993). Critical thinking: What Every Person Needs to Survive in a Rapidly Changing World. (3rd ed.), Rohnert Park, California: Sonoma State University Press.

Paul, R. & Elder, L. (2005).The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools. Dillon Beach CA; Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Pantaleo, S. (2005). Young Children Engage with the Metafictive in Pictures Books. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 28 1.

Pithers, R. & Soden, R. (2000). Critical Thinking in Education: A Review, Educational Research. 42 3, 237-249.

Seels, B. (1994). Visual literacy: The Definition Problem. In Moore D.M. & Dwyer F. (Eds.) Visual literacy: A Spectrum of Visual Learning.

Englewood Clifts, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.</p> Seliger, H., & Shohamy, E. (1990). Research design: Qualitative and Descriptive Research. In Second Language Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sinatra, R. (1986). Visual Literacy Connections to Thinking, Reading and Writing. Springfield, I.L.: Charles C. Thomas.

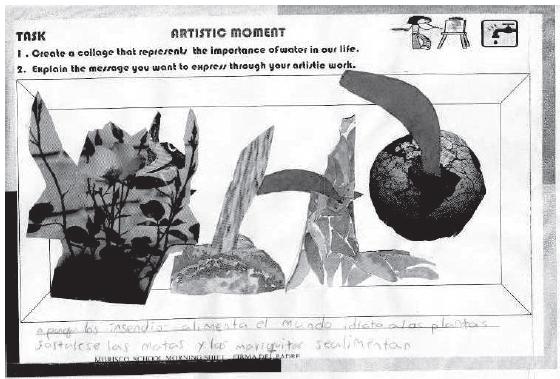

Appendix 1

Student’s artifact

“Apaga los incendios, alimenta el mundo, hidrata a las plantas, fortalece las matas y las mariquitas se alimentan”

“It extinguishes the fires, feeds the world, hydrates the plants, strengthens the bushes, and feeds the ladybirds”

(ART SEP 02)

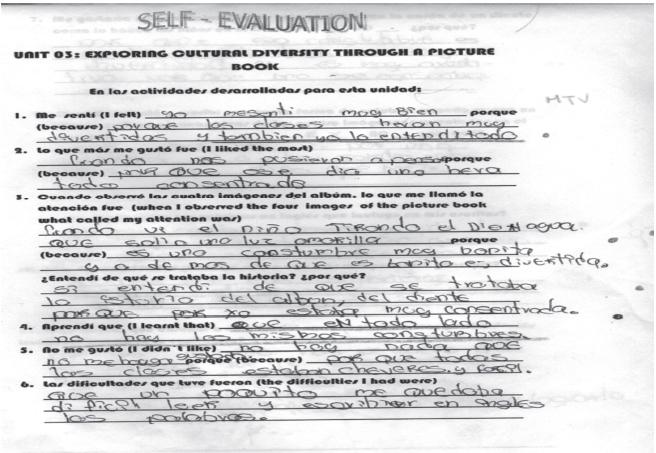

Appendix 2

A questionnaire

- Me sentí muy bien porque las clases eran muy divertidas y también lo entendí todo. I felt very good because the classes were really fun and I also understood everything.

- Lo que mas me gusta fue cuando nos pusieron a pensar porque ese día uno era todo concentrado. What I liked the most was when we began to think because that day I was very concentrated.

- Cuando observe las cuatro imágenes del álbum, lo que me llamo la atención fue cuando vi el piño tirando el diente en agua que salía una luz amarillo porque es uno costumbre muy bonita y además de que es bonito es divertido. When I observed the four images of the picture book what called my attention was when I saw them pulling the tooth in the water that left a yellow light because it is a very nice custom and also fun. ¿Entendí de qué se trataba la historia? ¿Por que? Si entendí de qué se trataba la historia del albon, del diente pues que país yo estaba muy concentrada. Did you understand what the store was about? Why? Yes I understood what the story was about, about the tooth from the country, I was concentrating a lot.

- Aprendí que que en todo lado no hay los mismos costumbres. I learned that not everywhere are the same customs.

- No me gusta no hay nada que no me gustaba porque por que todas las clases estaban chéveres y fácil. I did not like there was nothing that I did not like because all the classes were fun and easy.

- Las dificultades que tuve fueron que un poquito me que daba difícil leer y escribir en ingles las palabras. The difficulties I had were that it was a little hard to read and write the words in English.

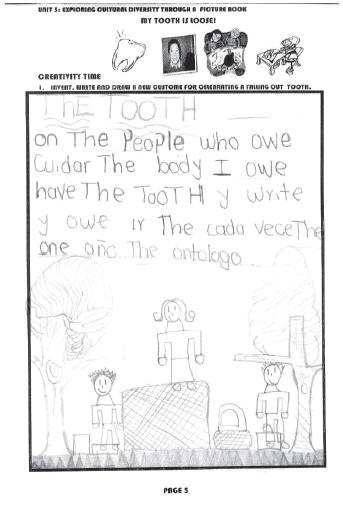

Appendix 3

Development of communicative skills

Instructions:

1. Invent, write and draw a new custom for celebrating a falling out tooth.

Student’s writing:

“The Tooth. On the people who owe cuidar (to take care of) the body I owe have the tooth y (and) write y (and) owe ir (to go) the cada vez (each time) the one año (year) the ontologo (dentist).

Appendix 4

Sample of a student’s critical visual reading comprehension and creating at a complex level

Que no es necesario gastar el agua y dejar la llave abierta

That is not necessary to spend the water leaving the open faucet and go away

No jugar con el agua de la llave

Not to play with water of the faucet

Métricas

Licencia

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/