DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/23448350.18389Publicado:

05/01/2022Número:

Vol. 44 Núm. 2 (2022): Mayo-Agosto 2022Sección:

Ciencia e ingeniería“Snapshot” of the State of Software Reuse in Colombia

“Radiografía” del estado de la reutilización de software en Colombia

Palabras clave:

Software reuse, Survey, Success practices, Adoption barriers (en).Palabras clave:

Reutilización de software, Encuesta, Prácticas de éxito, Barreras de adopción (es).Descargas

Referencias

Baharom, F. (2020). A survey on the current practices of software development process in Malaysia. Journal of Information and Communication Technology, 4, 57-76

Barbara, K., Shari, P. (2002). Principles of survey research part 4. ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes, 27(3), 20-23. https://doi.org/10.1145/638574.638580 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/638574.638580

Barros-Justo, J. L., Olivieri, D. N., Pinciroli, F. (2019). An exploratory study of the standard reuse practice in a medium sized software development firm. Computer Standards & Interfaces, 61, 137-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csi.2018.06.005 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csi.2018.06.005

Bass, L., Buhman, C., Comella-Dorda, S., Long, F., Robert, J. (2000). Volume 1: Market Assessment of Component-Based Software Engineering. Software Engineering Institute. http://www.dtic.mil/docs/citations/ADA395250 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21236/ADA388847

Chikh, A. (2017). Component-based approach for requirements reuse. The Knowledge Engineering Review, 32, e11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0269888917000030 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0269888917000030

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

Fedesoft (2019). ¿Cómo es la industria de Software y TI colombiana? https://fedesoft.org

Frakes, W. B., Fox, C. J. (1995). Sixteen questions about software reuse. Communications of the ACM, 38(6), 75-ff. https://doi.org/10.1145/203241.203260 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/203241.203260

GAO. (2009). Questionnaire Pretest Procedures. https://www.ignet.gov/sites/default/files/files/14_Questionnaire_Pretest_Procedures.pdf

García, V., Lucrédio, D., Alvaro, A., Santana De Almeida, E., Fortes, R., Fortes, M., Romero, S., Meira, L. (2007). Towards a Maturity Model for a Reuse Incremental Adoption. SBCARS, 2007, e96661. https://doi.org/10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.96661

Harrell, F. E. (2015). Regression Modeling Strategies. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19425-713

Hastie, T. J., Pregibon, D. (2017). Generalized Linear Models. In J. M. Chambers & T. J. Hastie (Eds.). Statistical Models in S (pp. 195-247). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203738535-6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203738535-6

Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A Brief Tutorial on the Development of Measures for Use in Survey A Brief Tutorial on the Development of Measures for Use in Survey Questionnaires Questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1(1), 104-121. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819800100106 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819800100106

Hosmer, D., Lemeshow, S., Sturdivant, R. (2013). Applied Logistic Regression. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471722146.ch1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118548387

Karma, S., Radha, A., Zhangxi, L. (2006). Resources and incentives for the adoption of systematic software reuse. International Journal of Information Management, 26(1), 70-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJINFOMGT.2005.08.007 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2005.08.007

Kotrlik, J., Higgins, C. (2001). Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research appropriate sample size in survey research. Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal, 19(1), 43

Kwon, Y., Kim, E., Lee, N. (2015). Key factors on software reuse of e-Government common framework. En International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology, PyeongChang, South Korea. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACT.2015.7224900 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACT.2015.7224900

Lavrakas, P. J. (2008). Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Sage Publications DOI: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963947

Leung, W.-C. (2001). How to design a questionnaire. BMJ, 322, e106187. https://doi.org/10.1136/sbmj.0106187 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/sbmj.0106187

Lucrédio, D., dos Santos Brito, K., Alvaro, A., Garcia, V. C., de Almeida, E. S., de Mattos Fortes, R. P., Meira, S. L. (2008). Software reuse: The Brazilian industry scenario. Journal of Systems and Software, 81(6), 996-1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSS.2007.08.036 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2007.08.036

Mazo, R. (2018). Guía para la adopción industrial de líneas de productos de software - Editorial EAFIT / Colecciones - Universidad EAFIT. Editorial EAFIT. https://www.eafit.edu.co/cultura-eafit/fondo-editorial/colecciones/Paginas/guia-para-la-adopcion-industrial-de-lineas-de-productos-de-software.aspx

Ministerio de Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicaciones (MINTIC). (2019). Fortalecimiento de la industria TI - FITI. https://www.mintic.gov.co/portal/inicio/14404:Fortalecimiento-de-la-industria-TI-FITI

Morisio, M., Ezran, M., Tully, C. (2002). Success and failure factors in software reuse. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 28(4), 340-357. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2002.995420 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2002.995420

Nogueira Teixeira., E., Vasconcelos., A., Werner., C. (2018). OdysseyProcessReuse - A Component-based Software Process Line Approach. Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, 2, 231-238. https://doi.org/10.5220/0006672902310238 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5220/0006672902310238

Palomares, C., Quer, C., Franch, X. (2017). Requirements reuse and requirement patterns: a state of the practice survey. Empirical Software Engineering, 22(6), 2719-2762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-016-9485-x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-016-9485-x

Pfleeger, S. L., Kitchenham, B. A. (2001). Principles of Survey Research: Part 1: Turning Lemons into Lemonade. ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes, 26(6), 16-18. https://doi.org/10.1145/505532.505535 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/505532.505535

Ramírez, J. M. (2019). Industria nacional de software | Opinión | Portafolio. https://www.portafolio.co/opinion/juan-manuel-ramirez-m/industria-nacional-de-software-533306

Renault, O. (2014). Reuse/variability management and system engineering. En CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 1234, 173-194

Restrepo-Gutiérrez, L. F. (2021). Replication package for: “Snapshot” of the State of Software Reuse in Colombia. https://doi.org/10.17632/2HDX42X6WC.1

Restrepo-Gutiérrez, L. R., Suescún-Monsalve, E., Mazo, R., Correa, D., Vallejo, P. (2021). Factores de éxito y barreras de adopción en la reutilización de software: Una revisión de la literatura. Investigación e Innovación en Ingenierías, 9(3), 93-107. https://doi.org/10.17081/invinno.9.3.5565 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17081/invinno.9.3.5565

Rine, D. C., Nada, N. (2000). Empirical study of a software reuse reference model. Information and Software Technology, 42(1), 47-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0950-5849(99)00055-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0950-5849(99)00055-5

Rine, D. C., Sonnemann, R. M. (1998). Investments in reusable software. A study of software reuse investment success factors. Journal of Systems and Software, 41(1), 17-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0164-1212(97)10003-6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0164-1212(97)10003-6

Ripley, B. (2020). Ordered Logistic Or Probit Regression. https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/MASS/versions/7.3-51.5/topics/polr

Rothenberger, M. A. A., Dooley, K. J. J., Kulkarni, U. R. R., Nada, N. (2003). Strategies for software reuse: a principal component analysis of reuse practices. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 29(9), 825-837. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2003.1232287 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2003.1232287

Salkind, N. J. (2017). Exploring research (9th ed.). Pearson Education Limited

Singh, L. (2011). Accuracy of Web Survey Data: The State Of Research on Factual Questions in Surveys. Information Management and Business Review, 3, 48-56. https://doi.org/10.22610/imbr.v3i2.916 DOI: https://doi.org/10.22610/imbr.v3i2.916

van der Linden, F., Schmid, K., Rommes, E. (2007). Software Product Lines in Action. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-71437-8 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-71437-8

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Recibido: de septiembre de 2021; Aceptado: de enero de 2022

Abstract

Due to competitive markets, the software business wants faster, better, and cheaper solutions in a short amount of time. Software reuse emerges as a viable solution to these demands since it offers significant benefits, such as increased quality and efficiency and lower development costs and effort, as well as shorter commercialization times. This research aims to study and understand the state of the practice of software reuse in Colombia, to make comparisons with related works, and to offer an instrument for decision-making in companies that adopt these practices. To reach these objectives, three stages were proposed. In the first stage, the research questions were defined. In the second stage, a survey was developed, evaluated, and carried out to validate successful practices and adoption barriers in the context of the Colombian software industry. Finally, the results were analyzed and reported. This paper showed and evidenced the expectations, adoption barriers, and factors influencing the success of software reuse in Colombian industrial environments. In the same way, the experience from the development of this work serves as a roadmap for other regions that want to analyze the current state of reuse. Nevertheless, each organization needs to determine its capabilities and find the appropriate factors to be adopted to its context.

Keywords:

adoption barriers, software reuse, success practices, survey..Resumen

Debido a los mercados competitivos, el negocio del software quiere soluciones más rápidas, mejores y más baratas en un período corto de tiempo. La reutilización de software surge como una solución viable para estas demandas, ya que ofrece importantes beneficios, como mayor calidad y eficiencia, menores costos y esfuerzos de desarrollo y menor tiempo de comercialización. Este artículo pretende analizar el estado de la práctica de la reutilización de software en Colombia, realizar comparaciones con trabajos relacionados y ofrecer con este resultado un instrumento para la toma de decisiones en empresas que adoptan estas prácticas. Para llevar a cabo los objetivos anteriores se plantearon tres etapas. En la primera etapa se definieron las preguntas de investigación. En la segunda etapa se desarrolló, evaluó y realizó una encuesta para validar prácticas exitosas y barreras de adopción en el contexto de la industria de software colombiana. Finalmente, los resultados fueron analizados y reportados. El estudio mostró y evidenció las expectativas, barreras de adopción y factores que influyen en el éxito de la reutilización de software en entornos industriales en Colombia. El presente estudio muestra el estado actual de las prácticas de reutilización en la industria de software en Colombia. Asimismo, la experiencia en el desarrollo de este trabajo sirve como hoja de ruta para otras regiones que quieran analizar el estado actual de la reutilización. Sin embargo, cada organización necesita determinar sus capacidades y encontrar los factores adecuados para adaptarlos a su contexto.

Palabras clave:

barreras de adopción, encuesta, prácticas de éxito, reutilización de software..Resumo

Devido aos mercados competitivos, o negócio do software quer soluções mais rápidas, melhores e mais baratas num curto espaço de tempo. A reutilização de software surge como uma solução viável para estas exigências, uma vez que oferece benefícios significativos, tais como maior qualidade e eficiência e menores custos e esforços de desenvolvimento, e tempos de comercialização mais curtos. Esta investigação visa estudar e compreender o estado da prática da reutilização de software na Colômbia, fazer comparações com trabalhos relacionados, e oferecer um instrumento para a tomada de decisões nas empresas que adoptam estas práticas. Para alcançar estes objectivos, foram propostas três fases. Na primeira fase, foram definidas as questões de investigação. Na segunda fase, foi desenvolvido, avaliado e realizado um inquérito para validar práticas bem-sucedidas e barreiras à adopção no contexto da indústria de software colombiana. Finalmente, os resultados foram analisados e comunicados.

O trabalho mostrou e evidenciou as expectativas, barreiras à adopção e factores que influenciam o sucesso da reutilização de software em ambientes industriais colombianos. Da mesma forma, a experiência do desenvolvimento deste trabalho serve de roteiro para outras regiões que queiram analisar o estado actual da reutilização. No entanto, cada organização precisa de determinar as suas capacidades e encontrar os factores adequados a adoptar no seu contexto.

Palavras-chaves:

desenvolvimento sustentável, inteligência artificial, políticas públicas, segurança alimentar, vocação agrícola..Introduction

Competitiveness in software development has increased over the last five years (Ramírez, 2019). However, in addition to making advancements, software industries require novel techniques to produce faster and better systems in a short time. As a result, product line engineering and other reuse-based methodologies such as duplication-based, component-based, and delta-based reuse and configuration management have gained increasing attention over recent years (Chikh, 2017; Mazo, 2018; Nogueira Teixeira, et al., 2018; Renault, 2014). Colombia is not an exception to this global trend. The conditions of the software industry, such as its transverse and globalized nature that supports any organization type, as well as the low cost of raw material investment, make it attractive to both domestic and foreign investors (MINTIC, 2019). In addition, the software industry is a high employment generator in design, development, maintenance, updating, and support phases. According to Fedesoft (2019), in 2018, the software industry in Colombia employed 109.000 people in 6.096 companies that billed 3 million euros per year with an average annual growth of 16,7% during the last six years, out of which 90% are micro and small enterprises and 40% are five years old or less. Due to this growth, we consider it necessary to determine the state of the practice and identify the technical and non-technical factors that influence software reuse practices in the Colombian industrial context.

This paper presents a survey that attempts to relate software development organizations’ characteristics in Colombia with software reuse practices. The main objective of this research is to determine which factors have more influence on software reuse success. Twenty-six factors were identified in the literature and then considered in the survey. These factors were divided into four categories: organizational, business, technological, and process factors. In this survey, we also recorded recent experiences reported by industry professionals that already achieved success (or not) at adopting reuse in their organizations. Therefore, we collected information about adoption barriers in software reuse. This information helps identify trends, problems, and possible improvements to the reuse strategies currently used in the software industry. The survey involved the participation of Colombian software organizations. However, we consider that other countries could take the results as a reference or carry out a similar study with the conditions of their context. This is due to the fact that we found similar results in other surveys carried out in the US, Brazil, and other European countries (Baharom, 2020; Barros-Justo et al., 2019; Bass et al., 2000; Frakes and Fox, 1995; García et al., 2007; Karma et al., 2006; Kwon et al., 2015; Lucrédio et al., 2008; Morisio et al., 2002; Palomares et al., 2017; Rine and Nada, 2000; Rine and Sonnemann, 1998; Rothenberger et al., 2003; van der Linden et al., 2007).

This document is structured as follows: Section 2 (Methodology) presents the research questions and the methodology used to develop the survey; Section 3 (Results) presents the survey results and describes the significance of the findings; and, finally, Section 4 (Discussion and Conclusions) presents the conclusions of this research and discusses possible future work.

Methodology

In order to make decisions (public policies and private initiatives) to sustain the software industry in Colombia, it is necessary to know its current state. Currently, this state is unknown, and, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies about it. A detailed snapshot of software reuse would enable us to identify the industry’s opportunities, trends, and weaknesses. Therefore, it is necessary (i) to know the state of practice in software reuse in Colombia and (ii) to identify the software reuse strategies (i.e., how it is applied, how it is used, what are its implications for practice, what are the research trends, what are the open problems and areas for improvement) in the Colombian software industry. Taking advantage of the key factors described in the literature (Baharom, 2020; Barros-Justo et al., 2019; Bass et al., 2000; Frakes and Fox, 1995; García et al., 2007; Karma et al., 2006; Karma et al., 2006; Lucrédio et al., 2008; Morisio et al., 2002; Palomares et al., 2017; Rine and Nada, 2000; Rine and Sonnemann, 1998; Rothenberger et al., 2003; van der Linden et al., 2007), we defined five global research questions for the Colombian scope:

-

RQG1. What are the characteristics of software production (business factors)?

-

RQG2. How is software reuse promoted in companies (organizational factors)?

-

RQG3. How is software reuse applied and controlled (processes factors)?

-

RQG4. How is software reuse supported (technological factors)?

-

RQG5. What are the expectations and adoption barriers in the context characteristics (organization size)?

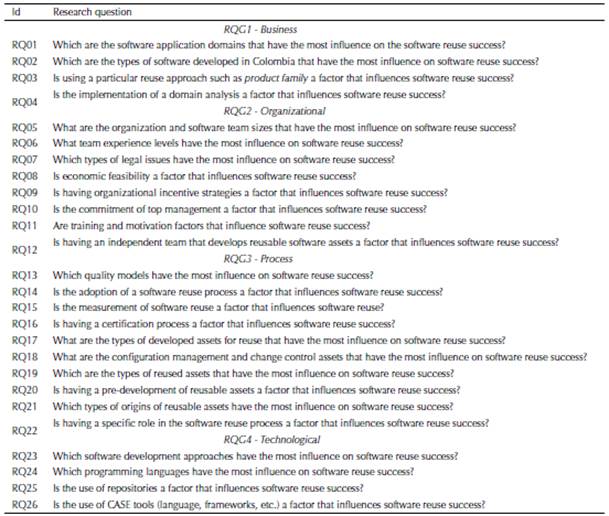

Each global research question (RQG1, RQG2, RQG3, and RQG4) was composed of a set of research questions, which are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Research questions

A survey was used to answer research questions because it allows us to reach a larger audience and quickly collect and analyze data from respondents in different regions of Colombia. This survey was carried out to define the state of the practice of software reuse in Colombia and to answer the research questions defined in Table 1. We carried out a survey following the guidelines by Pfleeger and Kitchenham (2001). The survey follows a methodological process divided into seven steps: 1) defining the survey questions, 2) survey preliminary evaluation, 3) identifying the survey target population, 4) survey data collection, 5) survey data analysis, 6) threats to validity in the survey, 7) survey results. Steps 1 to 6 are described in the remainder of this section, and Step 7 is discussed in Section 3.

Defining the survey questions

In the first step, we defined the survey questions. These questions were based on the 26 factors found in the literature (Restrepo-Gutiérrez et al., 2021). The survey has 54 questions. It was built through an iterative process. Its final version was obtained after carrying out the preliminary evaluation, which is shown in Subsection 2.2. The survey has closed and open-ended questions distributed in three groups. Their distribution is presented in the scheme sheet (Restrepo-Gutiérrez, 2021):

-

Survey main question: One survey question allowed us to investigate and measure the level of software reuse success and respond to the information collected through the other questions.

-

Survey research questions: We defined 34 survey questions. Each of them was related to a research question in Table 1, which, in turn, was related to a factor. These responses and their relationship with the main question allow us to answer the 26 research questions.

-

Survey complementary questions: We defined 19 questions to collect general information about the business and the person who takes the survey, namely company location, software application domain, number of employees, staff experience, and the person’s role. Therefore, some of these questions were used to collect information about company tools, framework usage, programming language usage, among others.

The survey was designed to be completed in less than 20 minutes; the whole questionnaire is available online (Restrepo-Gutiérrez, 2021).

Survey preliminary evaluation

In the second step, the survey questions were preliminarily evaluated by six software engineering research experts (internal review) and five software industry experts (external review).

Internal review: For the internal review, we asked the six research experts to evaluate each survey question according to a list of aspects to avoid in a survey, which have been defined byBarbara and Shari (2002)andLeung (2001). The list is available in the replication package byRestrepo-Gutiérrez (2021). We asked the research experts to send feedback via email; some changes were analyzed and applied to the survey questions based on it. This internal review resulted in minor changes such as clarifying terms and completing questions. Regarding the confusing terms, experts identified elements of the survey with unclear definitions that could result in misunderstandings. These elements were redefined for the sake of clarity. For example, one of the experts suggested defining the term systematic approach since it was not understood as referring to software quality models. Regarding the incomplete questions, experts suggested adding more items to the answer lists for some questions. For example, in the list of services offered by companies, hosting and software integration services should be added.

External review: After the internal review with research experts, we conducted a review with software industry experts. This evaluation included people with a high degree of experience in the field (head of the technology department, product manager, software innovation leader, and business analyst roles). These people were associated with well-known software companies in Colombia, located in several departments of Colombia. To evaluate the survey, we held a one-hour meeting with each industry expert. We presented the contents of the content in each meeting, and we explained the research goal to each industry expert. We also requested that each industry expert complete the survey aloud: “say everything you think" (GAO, 2009). Then, we asked them to find issues regarding the survey questions. We recorded and reviewed these issues. We also discussed the survey structure (topic coverage, survey length, sensitivity, and missing questions) with the industry experts. The final survey version was finished and shared with the external reviewers.

Identifying the survey target population

The survey target population was companies in Colombia, whose main economic activity is software development. To identify this population, we got information from the Colombian Chamber of Commerce. This entity has a complete database that includes information that allows identifying the population under study. We got information of companies established in Colombia grouped by type of economic activity. Using the database, we got 5.818 companies whose main economic activity was software development. The filters used are available in a replication package (Restrepo-Gutiérrez, 2021). From these 5.818 software companies, a sample of 361 was determined for the survey, considering a confidence level of 95% and a margin error of 5% according to the general rule regarding acceptable margins of error mentioned by Kotrlik and Higgins (2001). Since the response rates are typically well below 100%, the authors recommended oversampling: “if you are mailing out surveys or questionnaires, count on increasing your sample size by 40%-50% to account for lost mail and non-responders” (Salkind, 2017, p. 107). For this reason, oversampling was used to anticipate the response rate. To calculate the response rate, the results from the first week after sending the survey were used to estimate how many additional responses were required. As the response rate was 9% of the initial sample of 361 companies, it was established that the survey would be randomly sent to 4.011 companies.

Survey data collection

We defined a standardized email to send the survey to the target population. We applied the following strategy to send the standardized email: (i) if the company provided an email address (for example, on its website), we sent the standardized email to that email address; or (ii), if the company did not provide an email address, we tried to contact it through the Contact us section, phone calls, or social networks (Facebook, Messenger, LinkedIn, and WhatsApp Business). 2.534 software companies were contacted through email and 1.477 by other means. To motivate the respondents to share their experiences freely, it was mentioned that their answers would remain anonymous and that the results would be shared when they were published. It is important to note that we internally recorded each company’s name and location (department). This information was used to guarantee that the survey was answered by no more than one representative per company. To manage the survey responses, we used an online survey platform. In the end, 367 companies fully completed the online survey, thus complying with the sample needed, with an average time responding of 15 minutes and a withdrawing rate of 37%.

Survey data analysis

This project was based on quantitative survey data, allowing us to perform statistical analyses to test our research questions. Descriptive statistics and multinomial and ordinal logistic regressions were used to analyze the research questions. This analysis aimed at determining which of the responses of the survey research questions (predictor variables) were the most influential over the survey main question responses (response variable), and, in the end, to be able to answer the research questions. Logistic regression models describe the relationship between a response variable and one or more explanatory variables. The strength of logistic regression models is their ability to handle many variables, some of which may be on different measurement scales (Harrell, 2015). There are different logistic regression models: multiple, multinomial, and ordinal logistic. Multiple logistic regression models consider more than one independent variable, ordinal logistic regression models consider the ordinal nature of the outcome, and multinomial logistic regression handles the case where the outcome variable is nominal with more than two levels (Harrell, 2015). As there is only one independent variable in the study, multiple logistic regression models were ruled out. Instead, multinomial and ordinal logistic regression models were chosen to describe the relationship between variables.

The response variable (survey main question responses) was an ordinal numerical scale from 1 to 10, where 1 was unsuccessful, and 10 was very successful. This scale was grouped by two values, thus obtaining a scale of 5 levels from no success to strong success (no success, limited success, moderate success, substantial success, and strong success), where the values 1 and 2 of the initial scale correspond to the no success level and so on. Some of the predictor variables (survey research question responses) are also ordinal, and they go from strongly disagree to strongly agree (questions with the Likert answer scale). Other predictor variables were defined as categorical. The main question (related to the response variable) and an example of a survey research question (related to a predictor variable) can be found in the aforementioned replication package (Restrepo-Gutiérrez, 2021). The type of variable for each survey question can be viewed in the scheme sheet (Restrepo-Gutiérrez, 2021). To analyze open-ended questions, each answer was hand-coded into one of several categories defined as presented on the sheet questions (Restrepo-Gutiérrez, 2021). These categories were created with a general review of the answers.

It should be noted that multiple-choice questions cannot be considered as single variables, so each item of those questions counted as an independent variable. Therefore, there were 135 independent variables and one dependent variable in each model (Restrepo-Gutiérrez, 2021). Although some variables may be correlated, this analysis is not contemplated within the scope of this article. Each model required the response variable and the predictor variables. For the multinomial logistic regression, the response variable was entered as nominal. The response variable was ordinal for the ordinal logistic regression. The predictor variables associated with Likert-scale answers could be entered as nominal or ordinal. For this reason, four models were created with the variation resulting from taking the response and predictor variables as ordinal and nominal, respectively. In order to create the models, the polr and multinom commands from the MASS package of the R tool were used (Ripley, 2020). To estimate the best logistic regression model, an iterative model evaluation was performed with the Step command from the R stats package to fit the model. Step is an automated method based on AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) model selection that aims to find out the best fit model from all possible subset models and returns the optimal set of features (Hosmer et al., 2013). The four models were evaluated with the AIC. The replication package (Restrepo-Gutiérrez, 2021) has the created and evaluated models. As a result of this process, models 3 and 4 had the lowest AIC and the same value. The lowest AIC between models 1 and 2 was considered to decide on the model to choose, thus resulting in model 1, where the predictor variable is nominal. model 4 was also chosen, where the response variable is ordinal, and the predictor variables are nominal. The results of the regression are available in the referenced literature (Restrepo-Gutiérrez, 2021).

Threats to validity in the survey

Threats to the survey’s validity can be analyzed from the points of view of construct, internal, external, and statistical conclusion validity.

Construct validity: Construct validity addresses how well whatever is purported to be measured has been actually measured (Lavrakas, 2008). Verifying survey questions for construct validity is essential, especially when these questions are self-developed. We followed three steps to verify the construct validity. First, we performed a series of validation tasks for identifying and calibrating ambiguously worded surveys. Second, four experienced researchers not involved in the questionnaire design were consulted to discuss each question. Then, the survey was revised based on the feedback collected to ensure that the closed questions were easy to interpret and sufficiently complete. Finally, a pretest was conducted to finetune the survey; it was taken by two researchers. They were asked to comment on their understanding of each item after filling out the questionnaire. Based on their feedback, minor revisions were performed.

Internal validity: Internal validity considers whether the experimental design can support conclusions on causality or correlations (Morisio et al., 2002). Questionnaires should have items that are logically interrelated to elicit information about the constructs under analysis without defects that would distort the information. The questionnaire presented in Restrepo-Gutiérrez (2021) was evaluated for internal consistency by computing Cronbach’s alpha test, which is the most widely used measure of reliability. It describes the internal validity (Hinkin, 1998), which is how much each measured element correlates to each other, or the overall consistency of the questionnaire (Cronbach, 1951). According to Hinkin (1998), an acceptable value for Cronbach alpha is 0,7, but a minimum of 0,8 is the most desirable value. The evaluated questionnaire has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0,9. Therefore, the questionnaire’s internal coherence is acceptable, and the results presented in Section 3 are valid.

The accuracy of the answers is difficult to calculate due to the anonymity of the respondents (Singh, 2011). To address this issue, no incentives were given for responding to the survey other than the self-interest of respondents to complete it. The answers were also reviewed. As a result of this process, 222 incomplete and 6 completed surveys were rejected due to inconsistency in the data, such as company name not within our list of software companies or meaningless data in open-ended questions. Additionally, the impact on the data depends on the size of the group surveyed. In the research, we have 367 reviewed and completed surveys. It would take several people entering the wrong information to make a noticeable difference. In this case, the use of a survey protects us against bad actors. The dates of the studies found in the literature are different, so the comparisons are approximate since the state may have changed over time. The only way to avoid this threat to the validity of the comparison is to conduct the study in parallel. Such a study is costly, and we do not have the resources to do it.

External validity: It refers to the extent to which the research findings based on a sample of individuals or objects can be generalized to the same population from which the sample is taken or to other similar populations in terms of contexts, individuals, times, and settings (Lavrakas, 2008). The defined sample represents the population in our survey, and the participants were chosen using a random sampling method. Therefore, our research can be generalized to describe software organizations in Colombia. Also, to avoid survey non-response effects, the response rate was maximized by sending reminder emails and re-sending the uncompleted survey.

Statistical conclusion validity: It refers to the accuracy of a conclusion regarding a relation between or among variables of interest. As the sample size is considerable, there is no bias in the assumptions made of the descriptive statistics. Nevertheless, due to the large number of variables in the logistic regression model, there may be a bias in the results given by model 4. For this reason, a chi-squared-type statistic to test the validity of the logistic regression model was applied, using the anova command from the stats package of R (Harrell, 2015; Hastie and Pregibon, 2017), which compares model 4 before executing the Step command against the resulting model. The residual deviance of the model 4 was 521,8, 477 for the resulting model, and the Pr(Chi) was 0,9998, nearly 1, which indicates that the resulting model is better than model 4 and concludes that the resulting predictor variables have significant interactions with the independent variable. Another threat to the statistical conclusion validity is that the survey results focused on the impact of individual factors on the dependent variable, but some influences may imply combinations of factors. Finally, and as it was not contemplated, a correlation analysis within this article’s scope is considered a threat that will be mitigated in future work.

Results

This section presents the survey results and the answer to the 26 research questions.

Figure 1 shows the number of participants of the survey grouped by region. The software organizations that answered the survey were mainly located in the Colombian middle-eastern region, since 64.4% of the industry is located there. The Coffee Axis region follows with 18,2% of the survey population, the Pacific region with 9,5%, and the other regions with 7,9%.

The Flatlands (Llanos) (40%), the Coffee Axis (67%), the Colombian Middle-Eastern region with (72%), the Pacific (73%), the Caribbean (76%), and the South-Center region (80%) reported a reuse success level that ranges from strong to substantial, which indicates that Colombian software organizations are at similar levels in terms of software reuse (68% on average), regardless of the region where they are located. It is stressed that 68% of the participants indicated that reuse success is associated with companies that measure the reuse level; the remaining companies made a subjective analysis.

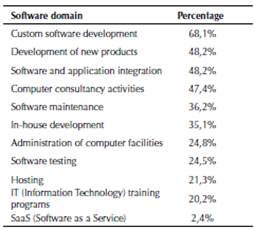

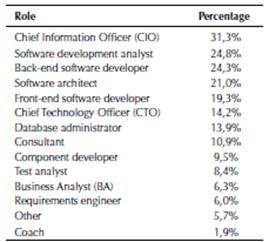

The participants represented a broad range of software domains (Table 2). The categories are not mutually exclusive, and one participant can be placed in multiple software domains. Most of the participants work in software companies dedicated to developing custom products. Table 3 presents the participant roles. Again, the categories are not mutually exclusive, and one participant can play multiple roles. Most of the participants had the CIO role as their main role while playing a complementary one. In Colombia, mainly in startups, a CIO can hold multiple roles, such as back-end and front-end software developer and architect at the same time. In large, medium, and small companies, the organizational structure is very well-defined, so people generally do not occupy more than one role.

Figure 1: Software organizations participants by regions of Colombia

Table 2: Study population’s software domains

Table 3: Participant roles

Table 4 summarizes the influence of the studied factors on software reuse success. For factors associated with a survey question with multiple choice answers, the influence column shows the categories that had the most influence according to the regression results. To see more details in the results for each factor, see the replication package, file “Survey Detailed Results” (Restrepo-Gutiérrez, 2021).

Table 4. Factors that influence software reuse

Discussion

The results for every RQG are reported in the following items:

-

RQG1. What are the characteristics of software production (business factors)? As its main production characteristic, the software industry in Colombia has the development of various custom software products that share features. Furthermore, most organizations do not focus on a specific application domain; only 14% do. Therefore, the companies have an excellent opportunity to take advantage of the software product line approach. However, it should be noted that this factor was not thoroughly investigated because it is a software reuse strategy that contains many concepts, processes, and practices (Mazo, 2018) that are beyond the scope of this research.

-

RQG2. How is software reuse promoted in companies (organizational factors)? The companies promote software reuse through incentives, training, and motivation, and the top management supports the introduction and maintenance of software reuse. Legal issues can occur when working for Colombia's banking, financial, government, and health domains. Most participants believe that software reuse is economically feasible in their company.

-

RQG3. How is software reuse applied and controlled (processes factors)? Software reuse is applied through a systematic reuse process established by the company, which is not associated with quality models. In this process, it was identified that:

Planning the development of reusable assets is not carried out from the beginning of the project; it is performed during the system’s development.

Companies do not usually have a role or independent team dedicated to developing reusable assets; it is the task of all members of the development teams.

The most created reusable assets are source code, detailed designs, software components, and libraries. These assets are under a configuration management platform.

The reliability of the certification process of these reusable assets is not strictly applied in startups and small companies.

The most reused assets are the software components, architectures, test cases, and detailed designs.

The origin of the reused assets is mainly from existing projects, which are improved for use. Almost half of the companies measure their progress in software reuse.

-

RQG4. How is software reuse supported (technological factors)? Software reuse is supported through the use of repositories and CASE tools. It should be noted that the most used programming paradigm is object-oriented, and the most used methodology is the agile method.

-

RQG5. What are the expectations and adoption barriers in the context characteristics (organization size)? It was identified that cost reduction, decreased labor needs, and productivity increase are significant software reuse expectations. And the principal adoption barriers are the diverse running projects, the lack of time and resources, and lack of communication between employees.

Concerning state of the art, a high level of similarity between the result of this study and the literature was found (Baharom, 2020; Barros-Justo et al., 2019; Bass et al., 2000; Frakes and Fox, 1995; García et al., 2007; Karma et al., 2006; Kwon et al., 2015; Lucrédio et al., 2008; Morisio et al., 2002; Palomares et al., 2017; Rine and Nada, 2000; Rine and Sonnemann, 1998; Rothenberger et al., 2003; van der Linden et al., 2007). Some factors led to the same conclusion of influence on software reuse success: application domain, product family approach, domain analysis, management commitment, economic feasibility, team size, the origin of the reused assets, configuration management, reused asset type, and development of assets for reuse. Furthermore, it was evidenced that they have been conserved over time given the new development practices.

Particularly for the Colombian case, the results concluded that the software organization size has an impact on software reuse success. In the literature (Frakes and Fox, 1995; García et al., 2007; Lucrédio et al., 2008; Morisio et al., 2002), this factor was treated in conjunction with the team size factor, but we found that it has a different influence, which suggests that this factor should be separated for further research. Also, it was found that a systematic reuse process, an independent reusable assets development team, and the previous development of reusable assets do not influence software reuse success. This shows that a software reuse process has not been formally adopted in Colombian software companies; the reuse of assets is made opportunistically, that is, reactive and unplanned. Despite this, it is noted that benefits have been obtained since great work has been done from the organizational factors (incentives, training, top management support, etc.), but all companies need to formalize these reuse practices as part of their process model activities in order to get to a point where reuse is planned and adopted by the entire development group. We hope that this information helps to show the importance of these reuse practices and encourages others to replicate this work in other countries with emerging software industries, as well as to see that these reuse practices accelerate the growth, quality, and rapid delivery of software.

Conclusions

This paper presented the results of the survey on software reuse in Colombian software organizations, providing important factors to consider for success in the adoption of this approach, as well as experiences, the current state, adoption barriers, and expectations in software reuse, information that can be used to introduce reuse in all organization sizes to obtain the desired benefits. Additionally, the work presented here is the result of collaborative work with the software industry in Colombia, people interested in this result, and the appropriate skills to provide us with evidence of what is happening in organizations concerning this issue. To summarize, we hope that this work has helped identify aspects where software reuse can be incorporated or improved. Nevertheless, each organization needs to determine its capabilities and find the factors appropriate to adopt these practices to its context. With this work, we also want to motivate other regions to prepare this type of study in order to have a more global understanding of reuse and its adoption factors, so that more companies have support information for decision-making.

As for future works, the following remarks could be made: (i) a deeper analysis should be conducted regarding the factors in order to present them in the form of a typology, given that there may be relationships among them (some may be sub-types of others and some may complement others); (ii) an analysis of correlations between the variables will be carried out; (iii) a comparison between the regions of Colombia will also be made; iv) the resulting factors should be put into further practice through the use of case studies with companies that want to deepen their understanding; and (v) a capability maturity model will be produced with these results to describe particular software development processes with the purpose of recommending feasible successful practices to enable and foster the adoption of asset reuse. Then, this proposed model will be validated with the software industries.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Vice-principalship for Discovery and Creation of Universidad EAFIT. This University supported this research. The authors would also like to thank Luisa Rincón, Henry Laniado, and Henry Velasco for their early comments and suggestions on this research, as well as the anonymous participants.

References

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2022 Luisa-Fernanda Restrepo-Gutiérrez, Elizabeth Suescún-Monsalve, Raúl Mazo, Paola-Andrea Vallejo-Correa, Daniel Correa

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

El (los) autor(es) al enviar su artículo a la Revista Científica certifica que su manuscrito no ha sido, ni será presentado ni publicado en ninguna otra revista científica.

Dentro de las políticas editoriales establecidas para la Revista Científica en ninguna etapa del proceso editorial se establecen costos, el envío de artículos, la edición, publicación y posterior descarga de los contenidos es de manera gratuita dado que la revista es una publicación académica sin ánimo de lucro.