DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/21450706.19625Publicado:

2022-07-22Número:

Vol. 17 Núm. 32 (2022): Julio-Diciembre 2022Sección:

Sección CentralEl ojo del espectador

The viewer's eye

O olho do espectador

Palabras clave:

Crítica de arte, metodologia da história de arte, espectadores, cultura visual, estudos visuais (pt).Palabras clave:

Crítica de arte, metodología de la historia del arte, espectadores, cultura visual, estudios visuales (es).Palabras clave:

Art criticism, methodology of art history, viewers, visual culture, visual studies (en).Descargas

Referencias

Abaton Book Company. (2011, April 3). The Responsive Eye [Video file]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/vaUme6DY8Lk

Alpers, S. (1984). The art of describing. Dutch art in the seventeenth century. Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Archivio Nazionale Cinema d'Impresa. (2013, October 30). Arte programmata [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/iji_cT9L6RQ

Arnheim, R. (1966). Art and visual perception: A psychology of the creative eye. Berkeley, CA, USA:University of California Press.

Aupetitallot, Y. (Ed.). (1998). Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV): strategies de participation: 1960-1968. Grenoble, France: Le Magasin CNAC.

Baxandall, M. (1988). Painting and experience in fifteenth-century Italy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Berenson, B. (1952). Esthétique et historie des arts visuels. Paris, France: Albin Michel.

Borgzinner, J. (1964). Op art: Picture that attack the eye. Time 84(17), 78-84. https://monoskop.org/images/a/a9/Op_Art_Pictures_That_Attack_the_Eye_1964.pdf

Caianiello, T. (2018). The Fluid Boundaries between Interpretation and Overinterpretation: Collecting, Conserving, and Staging Kinetic Art Installations. In R. Rivenc and R. Bek (Eds.), Keep It Moving?: Conserving Kinetic Art (pp. 16-24). Los Ángeles, CA, USA: The Getty Conservation Institute. http://www.getty.edu/publications/keepitmoving/keynotes/2-caianiello/

Crary, J. (1992). Techniques of the observer: On vision and modernity in the 19th century. Cambridge, MA, USA: The MIT Press.

Curtis, N. (2009). ‘As if’: Situating the Pictorial Turn. Culture, Theory & Critique, 50(2-3), 95-101. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735780903240067

Denise René. (n.d.). Galerie Denise René. https://www.deniserene.fr/denise-ren%C3%A9/

Eco, U. (1993). Opera aperta. Milan, Italy: Bompiani.

Eco, U., and Munari, B. (1962). Arte programmata. Arte cinética, opera moltiplicate, opera aperta. Milan, Italy: Officina d'arte grafica A. Lucini.

Fiedler, K. (2013). Sur l’origine de l’activité artistique. Paris, France: Éditions Rue d’Ulm. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.editionsulm.896

Fondaras, A. (2011). Decorating the house of wisdom: Four altarpieces from the Church of Santo Spirito in Florence (1485-1500) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland]. DRUM. http://hdl.handle.net/1903/11867

Fried, M. (1990). La Place du spectateur. Paris, France: Gallimard.

Greenberg, C. (1986). The collected essays and criticism. Arrogant Purpose, 1945-1949 (vol. 2). Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Greenberg, C. (1993). The collected essays and criticism. Modernism with vengeance, 1957-1969 (vol. 4). Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Harris, J. (2001). The New Art History. A critical introduction. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Huyghe, R. (1955). Dialogue avec le visible. Paris, France: Flammarion.

Jay, M. (1994). Downcast Eyes. The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press.

Krauss, R. (1993). The Optical Unconscious. Cambridge, MA, USA: The MIT Press.

Lagier, L. (2008). Les Mille Yeux de Brian de Palma. Paris, France: Cahiers du cinéma.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (1994). Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Popper, F. (1968). Origins and development of kinetic art. New York, NY, USA: New York Graphic Society.

Seitz, W. C. (1965). The Responsive Eye. New York, NY, USA: The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2914_300190234.pdf

Singer, R. (2012, July 9th). Gallerist Denise René, known as the “Pope of Abstraction” for championing op and kinetic art, is dead at 99. Blouin Artinfo. https://web.archive.org/web/20120711084728/http://www.artinfo.com/news/story/812718/gallerist-denise-ren%C3%A9-known-as-the-pope-of-abstraction-for-championing-op-and-kinetic-art-is-dead-at-99

Zimmermann, M. (1989). Seurat, Charles Blanc, and naturalist art criticism. Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, 14(2), 199-247. https://doi.org/10.2307/4108752

Zimmermann, M. (1991). Seurat and the art theory of his time. Brussels, Belgium: Fonds Mercator.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

El ojo del espectador

The viewer's eye

L'oeil du spectateur

O olho do espectador

El ojo del espectador

Calle14: revista de investigación en el campo del arte, vol. 17, núm. 32, pp. 320-332, 2022

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional.

Recepción: 28 Diciembre 2021

Aprobación: 05 Marzo 2022

Resumen: El inicio de la era de la imagen a mediados de la década de 1950 hizo que se reconsiderara la metodología de la historia del arte. Desde entonces, los críticos y estudiosos del arte han prestado cada vez más atención al papel del espectador en el arte y, por tanto, han desarrollado teorías del arte centradas en el espectador. Estos cambios, que tuvieron un impacto considerable en la estética visual de la década de 1960, se trasladaron al campo de la historia del arte en la década de 1970. Este artículo trata de autores como Clement Greenberg, Michael Baxandall y Svetlana Alpers, quienes sitúan la experiencia del ojo del espectador y la cultura visual en el centro de sus estudios, con el fin de examinar el empleo de estos componentes en las metodologías propuestas por la nueva historia del arte.

Palabras clave: Crítica de arte, metodología de la historia del arte, espectadores, cultura visual, estudios visuales.

Abstract: The dawning of the era of the image in the mid-1950s prompted a reconsideration of the existing methodology of art history. Since then, art critics and scholars have paid increasing attention to the viewer’s role in art, and they have therefore developed theories of art that are focused on the viewer. These changes, which had a considerable impact on the visual aesthetics of the 1960s, were transferred to the field of art history in the 1970s. This article deals with authors such as Clement Greenberg, Michael Baxandall, and Svetlana Alpers, who place the experience of the viewer’s eye and visual culture at the core of their studies, with the purpose of examining the use of these components in the methodologies proposed by the new art history.

Keywords: Art criticism, methodology of art history, viewers, visual culture, visual studies.

Résumé: L'avènement de l'âge de l'image au milieu des années 1950 amène à repenser la méthodologie de l'histoire de l'art. Depuis lors, les critiques d'art et les universitaires ont accordé une attention croissante au rôle du spectateur dans l'art et ont ainsi développé des théories de l'art centrées sur le spectateur. Ces changements, qui ont eu un impact considérable sur l'esthétique visuelle des années 1960, se sont répercutés sur le champ de l'histoire de l'art dans les années 1970. Cet article traite d'auteurs tels que Clement Greenberg, Michael Baxandall et Svetlana Alpers, qui placent l'expérience de l'œil du spectateur et la culture visuelle au centre de ses études, afin d'examiner l'utilisation de ces composants dans les méthodologies proposées. par la nouvelle histoire de l'art.

Mots clés: Critique d'art, méthodologie de l'histoire de l'art, spectateurs, culture visuelle, sémiotique visuelle.

Resumo: O início da era da imagem em meados da década de 1950 fez que se reconsiderasse a metodologia da história da arte. Desde então, os críticos e estudiosos de arte têm prestado cada vez mais atenção ao papel do espectador na arte e, portanto, desenvolveram teorias de arte centradas no espectador. Estas mudanças, que tiveram um impacto considerável na estética visual da década de 1960, se transferiram ao campo da história da arte na década de 1970. Este artigo trata de autores como Clement Greenberg, Michael Baxandall e Svetlana Alpers, que situam a experiência do olho do espectador e a cultura visual no centro dosseus estudos, com o fim de examinar o emprego destes componentes nas metodologias propostas pela nova história da arte.

Palavras-chave: Crítica de arte, metodologia da história de arte, espectadores, cultura visual, estudos visuais.

Introducción

In his book Dialogues avec le visible, which was published in 1955, art historian René Huyghe remar- ked on the transition from the civilization of the book to the civilization of the image. In the latter, priority was given to a work’s visual elements over its narra- tive. Huyghe observed that contemporary audiences demanded immediate comprehension and sensation, and he argued that the message of an image elici- ted an immediate and simultaneous perception that satisfied the need of such speed-obsessed viewers (Huyghe, 1995).

For Huyghe, a new dimension was opening up when civilization began to value the visual. The priority of visuality, which, for this French scholar, characterized the culture of the 1950s, appeared to be a necessary perspective in the field of history. Art criticism, being a visual and perceptive act, became the main system for art comprehension. Huyghe thought that art his- tory allowed for the possibility of direct experience, a perception alien to the discipline of history. Hence, he demonstrated the limitations of positivist histori- cal discourses that gave more importance to docu- ments, contracts, signatures, and dates than to artistic objects. In this regard, Huyghe (1955) explained that the written document, primordial in history, was no doubt infinitely useful, but it should be considered only an annex or preliminary source for the study of art.

Therefore, Huyghe distanced himself from the tradi- tional positivist methodologies in the study of art and initiated new possibilities for developing a different approach, similar to that used in modern, institutiona- lized visual studies. If the acts of viewing and having direct experience were emphasized and jointly used as a characteristic system in the history of art, the eye that observes or the subject that looks would acquire primordial importance in the study of art. From this perspective, several reflections from the field of art criticism and avant-garde practices were developed during the 1950s, when Huyghe's Dialogues avec le visible was popular, and especially throughout the 1960s. Thus, the thinking became that a work of art should be considered not only in terms of the work itself, but also in terms of its relationship with the eye, the viewer, and often with the visual regime of the culture that informed it. This was the starting point of a reflection that led to a whole new system of visual,cultural, and aesthetic references, which had been largely neglected until then. Despite the debates that arose between art history and visual studies and led, in the beginning, to a seemingly antagonistic relations- hip between the two disciplines, the truth is that, after Huyghe's studies were published, different art histo- rians, art critics, and artists made valuable contribu- tions that diverted art history and criticism away from formalist or attributionist methods and opened them up to visual culture.

This paper will trace the development of this approach with a focus on the visual, starting from the foundations of art criticism and art history. This path was developed alongside the contemporary art movements of the 1960s and what came to be called new art history in the 1980s. This relates to what Jonathan Harris calls "critical art history" (2001),in which forms of description, analysis, and evaluation linked to social and political activism are developed.

From the eye to perception

Since the 1950s, from the perspective of the his- toriography of art, aesthetics, and art criticism, the viewer’s role began to be vindicated, revitalizing the traditional German philosophy of pure visuality from the nineteenth century. Konrad Fiedler, a represen- tative of this philosophy, argues that nothing moreis needed to understand art than an eye that looks (2013). Along with Huyghe (1955), figures such as Bernard Berenson (1952), Clement Greenberg (1986), and Umberto Eco (1962) claimed that the viewer had a role at different levels and emphasized the viewer’s perceptive, subjective, or interpretative capacity (Berenson, 1952).

To a large extent, the foundation of these aesthetic reflections was the explosion of visuality and the vindication of the viewer's participation in artistic trends, which had its iconic beginning in the exhi- bition Le Mouvement, held at the Parisian gallery of Denise René in 1955 (Denise René, n.d.; Singer, 2012). The eye, the perceptual processes, and the principles of pure visuality were objects of great interest and extensive study in the optical and kinetic movements, as well as in the group dynamics of the Nouvelle Tendance founded in 1961, which demanded a greater involvement of the eye –and, therefore, ofthe viewer– in the creative process and even in the productive process of art (Popper, 1968).

In terms of art criticism, from the 1950s onwards, the consideration of the eye as an organ of knowledge was an essential part of Greenberg's thinking, to which he dedicated numerous writings. Greenberg gave the eye a primordial role in the valuation of artwork. For him, the trained eye, which makes the aesthetic judgment, uses its experience to carry out the critical appraisal (Greenberg, 1993). Eye and experience were the weapons that the art critic had in for directly confronting the artwork in order to avoid the use of the shield of rhetoric and let the art speak freely. In this way, it was possible to assess the quality of the artistic object. For instance, Greenberg stated that experience was “the only court of appeal in art –[it] has shown that there is both good and bad in abstract art” (1993, p. 118).

According to the Greenbergian narrative, good and bad come to a "consensus in taste" through the judg- ment of the trained eye (Greenberg, 1993, p. 118).

While he considered the trained eye as the producing agent of aesthetic judgments, Greenberg understood the existence of consensus, that is, of a trained eye that agrees with a set of other trained eyes, all of them assessing the art with a common aesthetic criterion. In relation to this, he argues that the trained eye “tend[s] always toward the definitely and positively good in art, knows it is there, and will remain dissatisfied with anything else” (Greenberg, 1993, p. 120). The priority of the eye is clear not only in his essays related to the value of art and the judgment of its quality, but also in the fact that Greenberg considers artwork in termsof its visual character, which later garnered significant criticism among even his own disciples (Krauss, 1993).

Thus, for Greenberg, the trained eye becomes the key to both the valuation of a work and the compre- hension of art and aesthetic experiences, thus leading to what Martin Jay calls the triumph of pure visuality (1994). For instance, such a formalist and fully visual reading is evident in Greenberg's interpretations of and comments on David Smith's sculpture. Greenberg considers Smith’s art to be “linear, open, [and] picto- rial” and to oscillate between “cubist classicism” and Baroque (Greenberg, 1986, p. 167).

For Greenberg, the importance of the eye pointed to the prominent role of the viewer in the aesthetic experience, but Eco went beyond pure visuality andreferred to the field of interpretation, which granted a significant role to the consideration of the aesthe- tic object. Focusing on the culture of the image and taking the relationship of the viewer with the new informal and kinetic artistic trends in the early 1960s as a point of reference, Eco began to speak of a new category of art that responded to contemporary artistic movements. He called this category “openwork” (Caianiello, 2018, p. 16). Eco was thinking about the transformations that the latest trends had brou- ght about by promoting a clearly participatory work that produced immediate comprehension (1993).

He saw in informal art a particular intervention of the viewer. However, such participation reached its fullest expression in kinetic art, which began to become generalized around the time the Arte programmata.Arte cinetica, opera moltiplicate, opera aperta exhi- bition was held in 1962 at Galleria Vittorio Emnauele in Milan (Eco and Munari, 1962; Archivio Nazionale Cinema d'Impresa, 2013). Eco had a close relations- hip with the poetics of kinetic art (Eco and Munari, 1962). In fact, Eco’s vision became foundational for art critics’ interpretations of optical and kinetic art, which adopted the term open work.

The position of the viewer was one of the most impor- tant additions from the artistic field, as made clearby the Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel (GRAV) from its initiation (Aupetitaillot, 1998). For optical and kinetic artists, as well as for art critics, the viewer was considered to be a perceptive engine that triggered an aesthetic action in the artwork in motion. Op art tendencies were characterized by a preeminence of visuality and the participatory action of the viewer, and they used visual strategies based on the psycho- logy of perception, which is why they attracted the attention of Rudolf Arnheim, who showed interest in the relationship between art and visual perception (Arnheim, 1966). At the opening of The Responsive Eye, a group exhibition of artists with optical and kinetic tendencies held in 1965 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, Arnheim openly expressed –in the 1966 documentary edited by Brian de Palma about the exhibition– his fascination with this artistic movement, which exemplified his analysis of the psychology of vision (Abaton Book Company, 2011; Lagier, 2008).

The Responsive Eye, which responded to the percep- tive and receptive process of the time, was based on purely visual principles. Its curator, William Seitz, built his proposal based on the visual processes favored by the new trends. Without alluding to the current terminology of op art and kinetic art, Seitz coined the term perceptual art, which exalted the perceptual value of art and the visual process involved in creating it (1965). Focusing on the psychophysical studies of the late nineteenth century and Gestalt theory, Seitz combined different artistic movements that favored the study of perceptual phenomena and used them to vindicate the role of the observing eye (1965). This new label of perceptual art allowed Seitz (1965) to gather a selection of artworks organized under six headings, which grouped examples from European optical and kinetic art and examples of American pos- tpictorial abstraction. Although the concept failed to gain traction in other scholarly works at the time, The Responsive Eye marked the beginning of the interna- tionalization of optical and kinetic art and its spill-over into the worlds of fashion, television, and film. The multiplication of the op art phenomenon, as it was generally called, confronted viewers with a specific visual experience who were intentionally provoked by these objects (Borgzinner, 1964). The inclusion of the viewer at the center of the aesthetic experience was also part of the claims of other trends, such as the happening, the Fluxus movement, and conceptual art, which revealed the importance that the viewer had acquired in the avant-garde culture of the time.

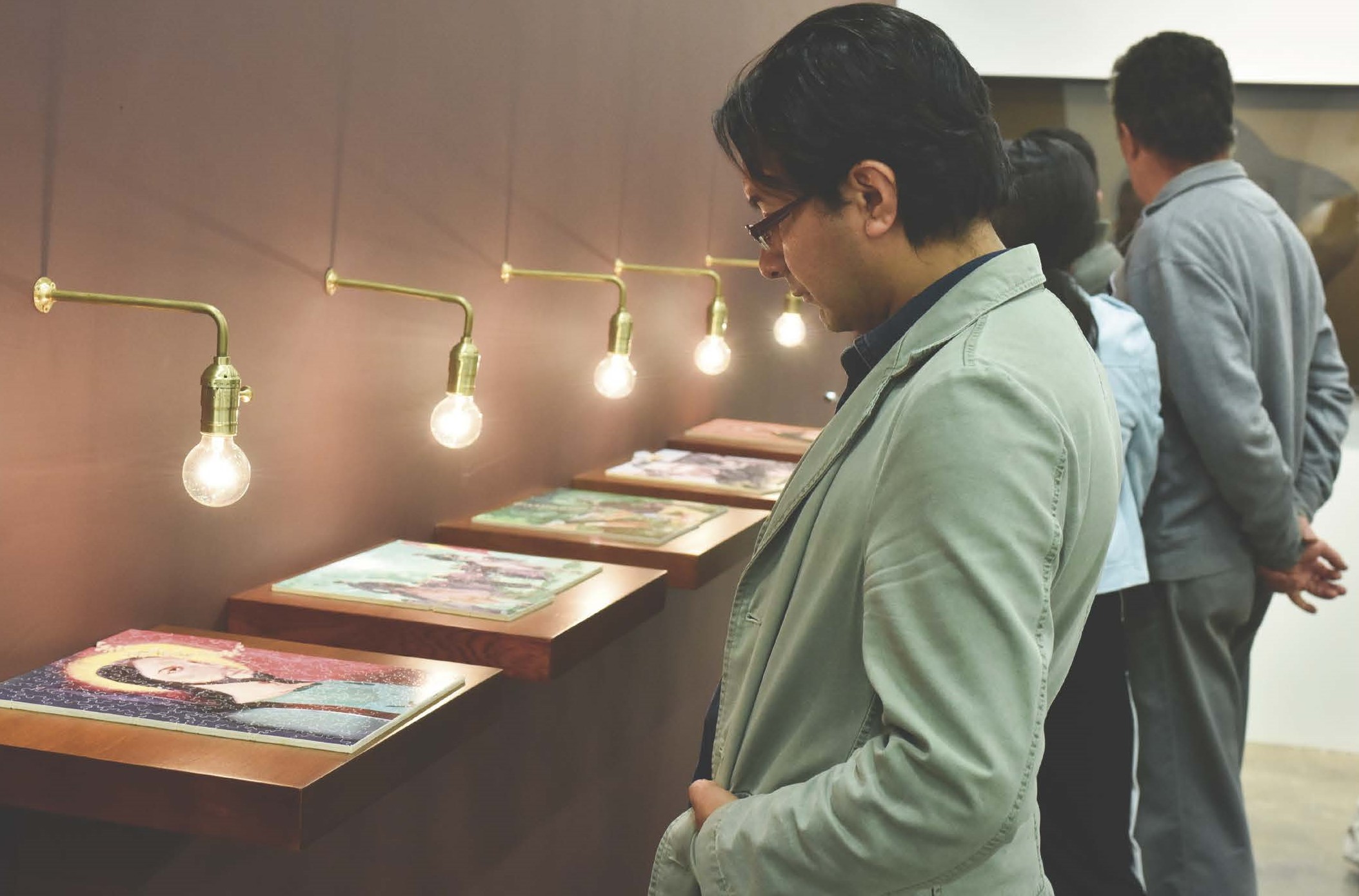

Imagen 1. ArtBo (2018). Fotografía cortesía de la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá

All these movements were undoubtedly in line with the observations of art critics, who were sensitive to the borrowing and incorporation of components from a society in which visuality clearly overflowed the limits of artistic culture. The multitudinous diffusion and multiplication of images provided bytelevision and the media in general prompted a consi- deration of the role of the image which went beyond the limits established by traditional cultural criticism, which gave rise to a civilization of images, an unques- tionable change that has modified every aspect of society.

Like Huyghe, the aforementioned authors understood the significant transformations that had taken placein the reign of visuality, and they analyzed the impli- cations that this transformation would imply in the creation and interpretation of art. With this shift from object to subject, encouraged by aesthetic practices and art criticism, the viewer became a privileged subject in the aesthetic reflections of the 1960s. The viewer’s function and active process in the consump- tion of images were incorporated a few years later into new visions that would be developed in the field of art history starting in the 1970s.

From the viewer to visual culture

The progression of leftist politics and the perception of art criticism during the 1960s had a direct impact on the methodological practices of art history, which began to rethink its own identity in the 1970s. The rise of issues related to class, gender, and politics, along with a questioning of the nature of capitalism, catalyzed the development of the so-called new art history, which drew on Marxist methodologies, femi-nist critiques, and psychoanalytic analyses and helped dismantle, in the words of Griselda Pollock and Fred Orton, the “institutionally dominant history of art” (cited in Harris, 2001, p. 21).

Consideration of the viewer's awareness, which was common in artistic practices and art criticism even in the 1960s, began to gain importance in academic studies in the 1970s and 1980s. The studies carried out by Michael Baxandall (1988), Svetlana Alpers (1984), and Michael Zimmermann (1991) are impor- tant examples. Other research works, such as that ofMichael Fried (1990) and Jonathan Crary (1992), took the viewer as the primary subject. These authors dealt with different periods from varying perspectives,in which the viewer was a fundamental element of reflection, thus opening new methodological and interpretative directions within the discipline of art history. That is why some of the reflections of these authors –especially Alpers and Baxandall– were incor- porated into the category of new art history: they expanded the traditional theoretical and aesthetic limits. Moreover, they responded to the objections raised by Huyghe decades earlier and took up a line of thought that had developed in the critical and aes- thetic fields of the art world.

Despite their different approaches, all of these authors expressed their dissatisfaction with the tradi- tional methodologies of art and declared the need to expand the margins of the study of art history. In this way, their motivation was centered on a new reading of the art of the past through a distinct reflective approach. For instance, Zimmerman pointed out the inadequacy of traditional procedures when resear- ching George Pierre Seurat and contemporary art theory. Therefore, he proposed a fusion of history and philosophy. Zimmermann argued that, whatever the historical and philosophical orientation of the art historian, only the interpretation that brought toge- ther these two perspectives determined by differentmethodologies –that of social history and that of the history of ideas– could lead to satisfactory conclu- sions (Zimmerman, 1991). Baxandall considered his work to be a social history of pictorial style, opting for a study on the social factors in the configuration of Renaissance painting (1988). In all cases, the viewer and the visual experience of the time became basic elements of consideration in approaching artistic objects.

Understanding painting as a means of accessing visual customs and their corresponding social expe- rience led directly to the consideration and analysis of the role of the viewer. Thus, for Alpers (1984) and Baxandall (1988), the aesthetic experience of the viewer became the preferred object of study. For example, Baxandall conducted a study of fifteen-th-century Florentine paintings in which the expe- rience of the viewer in his or her confrontation of the painting was one of the central elements. The reflec- tion on what was seen by those who looked at such paintings in fifteenth-century Florence is developed in the second section of Baxandall’s book (1988). When discussing religious paintings, Baxandall reformulates his initial question about their religious function and suggests a relationship between the viewer and the image, thus making this question the starting point for reflection. Baxandall wrote (1988):

So the first question –What was the religious function of the religious paintings?– can be reformulated, or at least replaced by a new question: What sort of painting would the religious public for pictures have found lucid, vividly memorable, and emotionally moving? (p. 45)

These questions, which highlight the author's change in thought, are at the heart of Baxandall's analysis. His interest was in determining the public’s experience as they looked at the painting. This interest led himto ask himself what kinds of viewers existed, what their visual references were, what moved and inte- rested them, and, above all, what visual culture they were immersed in. Through an analysis of the visual culture of the fifteenth century, Baxandall arrivedat a new reading of Florentine painting, which then became part of the visual ensemble of the culture of images for a typical Florentine citizen (according to Baxandall, the merchant), which comprised painting and sculpture, as well as religious drama, theater, dance, and more.

Imagen 2. ArtBo (2018). Fotografía cortesía de la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá

Alpers extends Baxandall’s approach to sevente- enth-century Dutch painting. Her study focuses on the visual culture of the Netherlands, an expression she claims to take directly from Baxandall. For the author, Dutch painting must be studied by appealing to the circumstances. In this regard, Alpers proposes not only seeing art as a social manifestation but also accessing images through the consideration of their place, role, and presence in culture in broader terms (1984). The analysis of art then becomes a reasoned study of society and of the perceptive conception existing at the time, in clear relation to the scientific advances and psychological investigations of the time. By considering these new parameters, Alpers goes beyond the traditional sources of research anchored in the iconographic method and opensa new field of study that surpasses the framework of the artwork to consider the visual culture of the moment.

In this way, the need to use cross-references and different methodologies is satisfied, as is the case ofthe Baxandall, Alpers, and Zimmermann. Thus, their studies draw on a variety of sources that, in addition to integrating traditional historical sources in general and art historical sources more specifically, include sources from the history of science, literature, psy- chology, sociology, technology, and so forth. The relationship between art and scientific advances, developed by the psychology of perception or by optics, begins to comprise a significant amount of the literature. Alpers, for example, uses various sour-ces: from the biography of Constantijn Huygens, to Johannes Kepler's scientific treatise Ad vitellionem paralipomena, and to seventeenth-century Dutch car- tography (Alpers, 1984). On the other hand, Baxandall, questioning the experience of painting in the fifte- enth century, appealed to diverse sources, suchas sermons, religious dramas, dance treatises such as Trattato dell’arte del ballo by Guglielmo Ebreo Pesarese (from 1470), and mathematics textbooks like De arimethrica by Filippo Calandri (from 1491) (Baxandall, 1988). Baxandall takes these sources as a basis for approaching the visual culture of Florentine

Imagen 3. ArtBo (2018). Fotografía cortesía de la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá

society and, above all, for reconstructing the expe- rience of average viewers, an approach that yields new readings of Renaissance paintings. For example, it reveals relationships that, while absent today, were immediately apparent to the viewers in the fifteenth century, as Baxandall explains (1988):

In Florence there was a great flowering of religious drama during the fifteenth century […] Where they exist they must have enriched people’s visualization of the events they por- trayed, and some relationship to painting was noticed at the time. (p. 71)

One of these relationships was the figure of fes- taiuolo, derived from the name of the narrator in Renaissance theater present in both sacred drama and paintings, such as Filippo Lippi’s The Virgin Adoring the Child (c. 1465). The figure of festaiuolo reproduced in the painting clearly appealed to the average viewer, who would have perceived such figure through his or her experience of the festaiuolo (Baxandall, 1988; Fondaras, 2011). That is why, beingimmediately related to Renaissance religious dramas, the figure was understood in the pictorial field as a natural figure mediating between the viewer and the scene, catching the beholder’s eye, and pointing to the central action of the image (Fondaras, 2011).

The study of optics and scientific knowledge about perception, the configuration of the eye, and the functioning of vision also recur in the studies of Baxandall, Alpers, and Zimmermann. The choiceto take a key personality in the scientific thought of the era under study as an example, as well as to deal with the perceptual processes and scientific knowledge of optics, is common among some ofthese studies. For instance, in his analysis of Seurat’s work, Zimmermann (1989) references the writings of Charles Henry, Charles Blanc, and Gustave Kahn. Zimmermann’s interest in Henry, which is paralleled by Alpers’s interest in Huygens, is based on Henry’s ability to exemplify the image of the human being–or, we could say, the typical viewer– by represen- ting humanity’s set of beliefs and knowledge at thetime. For Zimmermann, Henry’s aesthetic is part of an image of humanity that predominated in France at the beginning of the Third Republic and, more particularly, during the 1880s (Zimmermann, 1991). For Alpers, Huygens represents something similar because Huygens “testifies” –which is confirmed by the society around him– that his images were part ofa visual specificity that contrasted with textual culture (Alpers, 1984, p. xxiv).

The conclusions of these authors offer a perspec- tive that goes beyond the position of art in society, beyond the uses of art, and beyond the aesthetic proposals of art, since they all show different ways and means to look, the characteristics of perceptive culture, and the aspects that are fundamental to understand the vision of the artist and the audience. These results are not a historical study of facts and commands; they are, as Alpers argues, a history of visual culture.

In the studies discussed above, the intention to overcome traditional interpretations is frequently manifested. The introduction of new perspectives of historical time also provides readings that contradict interpretations based on stylistic or formalist prin- ciples. A clear example in this is Alpers’s The Art of Describing (1984), in which she questions the traditio- nal analyses of seventeenth-century Dutch painting that strove to justify such painting’s belonging with an Italian narrative system of representation, whose moti- vations were not primarily visual but textual. Alpers argues that the imposition of the Italian model and the preeminence of iconographic methodologies has led to erroneous interpretations of Dutch paintings. These readings are a literary imposition alien to sevente- enth-century Dutch culture, which was essentially a culture of images. Specifically, Alpers argues (1984):

Iconographers have concluded that Dutch realism is only an apparent or schijn realism. Far from depicting the “real” world, so this argument goes, such pictures are realizedabstractions that teach moral lessons by hiding them beneath delightful surfaces. Don’t believe what you see is said to be the message of the Dutch works. But perhaps nowhere is this “transparent view of art”, in Richard Wolheim’s words, less appropriate. For, as I shall argue, northern images do not dis- guise meaning or hide it beneath the surface but rather show that meaning by its very nature is lodged in what the eye can take in. (p. xxiv)

In contrast to traditional studies, Alpers’s work propo- ses a different reading of Dutch art, in which paintings are studied in the context of the visual images that proliferated at the time when they were created. As previously mentioned, Alpers starts from the figureof Huygens, an example par excellence of the seduction that image and optics produced in seventeen-th-century Dutch art. Indeed, throughout her work, it is clear that the nonconformity of Dutch painting to the Italian Renaissance canon is related, amongother reasons, to the reliance on optics and lenses in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century. Indeed, Alpers states (1984):

The Dutch present their pictures as describing the world seen rather than as imitations of significant human actions. Already established pictorial and craft traditions, broadly reinforced by the new experimental science and technology, confirmed pictures as the way to new and certain knowle- dge of the world. (p. xxv)

This type of methodology, which is inscribed in the study of contemporary art –where the problems of visuality and the integration of the virtual and the digital are determinant for artistic creation– was also present in other periods of history, that is, although some of the examples we have cited deal with the- mes from the impressionist era to the present day, a period in which scientific developments have been of vital importance for the creation of art, this method is also valid for other periods of history, as shown by the studies of Alpers and Baxandall. Hence, we have preferred to focus on studies that deal with periods preceding the nineteenth century.

It is evident that, with the publication of those studies in the 1980s, we find ourselves dealing with a new type of art history –the so-called new art history– which proposes a way of looking at and interpreting art and society which is linked to visual studies. In this way, Alpers and Baxandall, for instance, become illustrious forerunners of what William John Thomas Mitchell calls the “pictorial turn” (as cited in Curtis, 2009, p. 95). However, although their works have opened up new methodological and epistemolo- gical possibilities, they are part of a (re)thinking of the relationships among art, culture, and society that connects the critical analysis and artistic practices of the 1950s and 1960s with the new historiographical discourses that opened up the postmodern period, thus demonstrating the permeability among all these spheres.

References

Abaton Book Company. (2011, April 3). The Responsive Eye[Video file]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/vaUme6DY8Lk

Alpers, S. (1984). The art of describing. Dutch art in the seven- teenth century. Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Archivio Nazionale Cinema d'Impresa. (2013, October 30). Arte programmata [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/iji_cT9L6RQ

Arnheim, R. (1966). Art and visual perception: A psychology of the creative eye. Berkeley, CA, USA:University of California Press.

Aupetitallot, Y. (Ed.). (1998). Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV): strategies de participation: 1960-1968. Grenoble, France: Le Magasin CNAC.

Baxandall, M. (1988). Painting and experience in fifteenth-cen- tury Italy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Berenson, B. (1952). Esthétique et historie des arts visuels. Paris, France: Albin Michel.

Borgzinner, J. (1964). Op art: Picture that attack the eye. Time 84(17), 78-84. https://monoskop.org/images/a/a9/Op_Art_ Pictures_That_Attack_the_Eye_1964.pdf

Caianiello, T. (2018). The fluid boundaries between inter- pretation and overinterpretation: Collecting, conserving, and staging kinetic art installations.. In R. Rivenc and R. Bek (Eds.), Keep It Moving?: Conserving Kinetic Art (pp. 16-24). Los Ángeles, CA, USA: The Getty Conservation

Crary, J. (1992). Techniques of the observer: On vision and modernity in the 19th century. Cambridge, MA, USA: The MIT Press.

Curtis, N. (2009). ‘As if’: Situating the Pictorial Turn. Culture, Theory & Critique, 50(2-3), 95-101. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735780903240067

Denise René. (n. d.). Galerie Denise René. https://www.denise- rene.fr/denise-ren%C3%A9/

Eco, U. (1993). Opera aperta. Milan, Italy: Bompiani.

Eco, U., and Munari, B. (1962). Arte programmata. Arte ciné- tica, opera moltiplicate, opera aperta. Milan, Italy: Officina d'arte grafica A. Lucini.

Fiedler, K. (2013). Sur l’origine de l’activité artistique. Paris, France: Éditions Rue d’Ulm. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.editionsulm.896

Fondaras, A. (2011). Decorating the house of wisdom: Four altarpieces from the Church of Santo Spirito in Florence (1485-1500) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland]. DRUM. http://hdl.handle.net/1903/11867

Fried, M. (1990). La Place du spectateur. Paris, France: Gallimard.

Greenberg, C. (1986). The collected essays and criticism. Arrogant Purpose, 1945-1949 (vol. 2). Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Greenberg, C. (1993). The collected essays and criticism. Modernism with vengeance, 1957-1969 (vol. 4). Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Harris, J. (2001). The New Art History. A critical introduction. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Huyghe, R. (1955). Dialogue avec le visible. Paris, France: Flammarion.

Jay, M. (1994). Downcast Eyes. The denigration of vision in twentieth-century French thought. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press.

Krauss, R. (1993). The optical unconscious. Cambridge, MA, USA: The MIT Press.

Lagier, L. (2008). Les Mille Yeux de Brian de Palma. Paris, France: Cahiers du cinéma.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (1994). Picture Theory: Essays on verbal and visual representation. Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Popper, F. (1968). Origins and development of kinetic art. New York, NY, USA: New York Graphic Society.

Seitz, W. C. (1965). The responsive eye. New York, NY, USA: The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). https://assets.moma.org/ documents/moma_catalogue_2914_300190234.pdf

Singer, R. (2012, July 9th). Gallerist Denise René, known as the “Pope of Abstraction” for championing op and kinetic art, is dead at 99. Blouin Artinfo. https://web.archive.org/ web/20120711084728/http://www.artinfo.com/news/ story/812718/gallerist-denise-ren%C3%A9-known-as-the- pope-of-abstraction-for-championing-op-and-kinetic-art-is- dead-at-99

Zimmermann, M. (1989). Seurat, Charles Blanc, and naturalist art criticism. Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, 14(2), 199-247. https://doi.org/10.2307/4108752

Zimmermann, M. (1991). Seurat and the art theory of his time. Brussels, Belgium: Fonds Mercator.

Recibido: 28 de diciembre de 2021; Aceptado: 5 de marzo de 2022

Resumen

El inicio de la era de la imagen a mediados de la década de 1950 hizo que se reconsiderara la metodología de la historia del arte. Desde entonces, los críticos y estudiosos del arte han prestado cada vez más atención al papel del espectador en el arte y, por tanto, han desarrollado teorías del arte centradas en el espectador. Estos cambios, que tuvieron un impacto considerable en la estética visual de la década de 1960, se trasladaron al campo de la historia del arte en la década de 1970. Este artículo trata de autores como Clement Greenberg, Michael Baxandall y Svetlana Alpers, quienes sitúan la experiencia del ojo del espectador y la cultura visual en el centro de sus estudios, con el fin de examinar el empleo de estos componentes en las metodologías propuestas por la nueva historia del arte.

Palabras clave

Crítica de arte, metodología de la historia del arte, espectadores, cultura visual, estudios visuales.Abstract

The dawning of the era of the image in the mid-1950s prompted a reconsideration of the existing methodology of art history. Since then, art critics and scholars have paid increasing attention to the viewer’s role in art, and they have therefore developed theories of art that are focused on the viewer. These changes, which had a considerable impact on the visual aesthetics of the 1960s, were transferred to the field of art history in the 1970s. This article deals with authors such as Clement Greenberg, Michael Baxandall, and Svetlana Alpers, who place the experience of the viewer’s eye and visual culture at the core of their studies, with the purpose of examining the use of these components in the methodologies proposed by the new art history.

Keywords

Art criticism, methodology of art history, viewers, visual culture, visual studies.Résumé

L'avènement de l'âge de l'image au milieu des années 1950 amène à repenser la méthodologie de l'histoire de l'art. Depuis lors, les critiques d'art et les universitaires ont accordé une attention croissante au rôle du spectateur dans l'art et ont ainsi développé des théories de l'art centrées sur le spectateur. Ces changements, qui ont eu un impact considérable sur l'esthétique visuelle des années 1960, se sont répercutés sur le champ de l'histoire de l'art dans les années 1970. Cet article traite d'auteurs tels que Clement Greenberg, Michael Baxandall et Svetlana Alpers, qui placent l'expérience de l'œil du spectateur et la culture visuelle au centre de ses études, afin d'examiner l'utilisation de ces composants dans les méthodologies proposées. par la nouvelle histoire de l'art.

Mots clés

Critique d'art, méthodologie de l'histoire de l'art, spectateurs, culture visuelle, sémiotique visuelle.Resumo

O início da era da imagem em meados da década de 1950 fez que se reconsiderasse a metodologia da história da arte. Desde então, os críticos e estudiosos de arte têm prestado cada vez mais atenção ao papel do espectador na arte e, portanto, desenvolveram teorias de arte centradas no espectador. Estas mudanças, que tiveram um impacto considerável na estética visual da década de 1960, se transferiram ao campo da história da arte na década de 1970. Este artigo trata de autores como Clement Greenberg, Michael Baxandall e Svetlana Alpers, que situam a experiência do olho do espectador e a cultura visual no centro dosseus estudos, com o fim de examinar o emprego destes componentes nas metodologias propostas pela nova história da arte.

Palavras-chave

Crítica de arte, metodologia da história de arte, espectadores, cultura visual, estudos visuais.Introducción

In his book Dialogues avec le visible, which was published in 1955, art historian René Huyghe remar- ked on the transition from the civilization of the book to the civilization of the image. In the latter, priority was given to a work’s visual elements over its narra- tive. Huyghe observed that contemporary audiences demanded immediate comprehension and sensation, and he argued that the message of an image elici- ted an immediate and simultaneous perception that satisfied the need of such speed-obsessed viewers (Huyghe, 1995).

For Huyghe, a new dimension was opening up when civilization began to value the visual. The priority of visuality, which, for this French scholar, characterized the culture of the 1950s, appeared to be a necessary perspective in the field of history. Art criticism, being a visual and perceptive act, became the main system for art comprehension. Huyghe thought that art his- tory allowed for the possibility of direct experience, a perception alien to the discipline of history. Hence, he demonstrated the limitations of positivist histori- cal discourses that gave more importance to docu- ments, contracts, signatures, and dates than to artistic objects. In this regard, Huyghe (1955) explained that the written document, primordial in history, was no doubt infinitely useful, but it should be considered only an annex or preliminary source for the study of art.

Therefore, Huyghe distanced himself from the tradi- tional positivist methodologies in the study of art and initiated new possibilities for developing a different approach, similar to that used in modern, institutiona- lized visual studies. If the acts of viewing and having direct experience were emphasized and jointly used as a characteristic system in the history of art, the eye that observes or the subject that looks would acquire primordial importance in the study of art. From this perspective, several reflections from the field of art criticism and avant-garde practices were developed during the 1950s, when Huyghe's Dialogues avec le visible was popular, and especially throughout the 1960s. Thus, the thinking became that a work of art should be considered not only in terms of the work itself, but also in terms of its relationship with the eye, the viewer, and often with the visual regime of the culture that informed it. This was the starting point of a reflection that led to a whole new system of visual,cultural, and aesthetic references, which had been largely neglected until then. Despite the debates that arose between art history and visual studies and led, in the beginning, to a seemingly antagonistic relations- hip between the two disciplines, the truth is that, after Huyghe's studies were published, different art histo- rians, art critics, and artists made valuable contribu- tions that diverted art history and criticism away from formalist or attributionist methods and opened them up to visual culture.

This paper will trace the development of this approach with a focus on the visual, starting from the foundations of art criticism and art history. This path was developed alongside the contemporary art movements of the 1960s and what came to be called new art history in the 1980s. This relates to what Jonathan Harris calls "critical art history" (2001),in which forms of description, analysis, and evaluation linked to social and political activism are developed.

From the eye to perception

Since the 1950s, from the perspective of the his- toriography of art, aesthetics, and art criticism, the viewer’s role began to be vindicated, revitalizing the traditional German philosophy of pure visuality from the nineteenth century. Konrad Fiedler, a represen- tative of this philosophy, argues that nothing moreis needed to understand art than an eye that looks (2013). Along with Huyghe (1955), figures such as Bernard Berenson (1952), Clement Greenberg (1986), and Umberto Eco (1962) claimed that the viewer had a role at different levels and emphasized the viewer’s perceptive, subjective, or interpretative capacity (Berenson, 1952).

To a large extent, the foundation of these aesthetic reflections was the explosion of visuality and the vindication of the viewer's participation in artistic trends, which had its iconic beginning in the exhi- bition Le Mouvement, held at the Parisian gallery of Denise René in 1955 (Denise René, n.d.; Singer, 2012). The eye, the perceptual processes, and the principles of pure visuality were objects of great interest and extensive study in the optical and kinetic movements, as well as in the group dynamics of the Nouvelle Tendance founded in 1961, which demanded a greater involvement of the eye –and, therefore, ofthe viewer– in the creative process and even in the productive process of art (Popper, 1968).

In terms of art criticism, from the 1950s onwards, the consideration of the eye as an organ of knowledge was an essential part of Greenberg's thinking, to which he dedicated numerous writings. Greenberg gave the eye a primordial role in the valuation of artwork. For him, the trained eye, which makes the aesthetic judgment, uses its experience to carry out the critical appraisal (Greenberg, 1993). Eye and experience were the weapons that the art critic had in for directly confronting the artwork in order to avoid the use of the shield of rhetoric and let the art speak freely. In this way, it was possible to assess the quality of the artistic object. For instance, Greenberg stated that experience was “the only court of appeal in art –[it] has shown that there is both good and bad in abstract art” (1993, p. 118).

According to the Greenbergian narrative, good and bad come to a "consensus in taste" through the judg- ment of the trained eye (Greenberg, 1993, p. 118).

While he considered the trained eye as the producing agent of aesthetic judgments, Greenberg understood the existence of consensus, that is, of a trained eye that agrees with a set of other trained eyes, all of them assessing the art with a common aesthetic criterion. In relation to this, he argues that the trained eye “tend[s] always toward the definitely and positively good in art, knows it is there, and will remain dissatisfied with anything else” (Greenberg, 1993, p. 120). The priority of the eye is clear not only in his essays related to the value of art and the judgment of its quality, but also in the fact that Greenberg considers artwork in termsof its visual character, which later garnered significant criticism among even his own disciples (Krauss, 1993).

Thus, for Greenberg, the trained eye becomes the key to both the valuation of a work and the compre- hension of art and aesthetic experiences, thus leading to what Martin Jay calls the triumph of pure visuality (1994). For instance, such a formalist and fully visual reading is evident in Greenberg's interpretations of and comments on David Smith's sculpture. Greenberg considers Smith’s art to be “linear, open, [and] picto- rial” and to oscillate between “cubist classicism” and Baroque (Greenberg, 1986, p. 167).

For Greenberg, the importance of the eye pointed to the prominent role of the viewer in the aesthetic experience, but Eco went beyond pure visuality andreferred to the field of interpretation, which granted a significant role to the consideration of the aesthe- tic object. Focusing on the culture of the image and taking the relationship of the viewer with the new informal and kinetic artistic trends in the early 1960s as a point of reference, Eco began to speak of a new category of art that responded to contemporary artistic movements. He called this category “openwork” (Caianiello, 2018, p. 16). Eco was thinking about the transformations that the latest trends had brou- ght about by promoting a clearly participatory work that produced immediate comprehension (1993).

He saw in informal art a particular intervention of the viewer. However, such participation reached its fullest expression in kinetic art, which began to become generalized around the time the Arte programmata.Arte cinetica, opera moltiplicate, opera aperta exhi- bition was held in 1962 at Galleria Vittorio Emnauele in Milan (Eco and Munari, 1962; Archivio Nazionale Cinema d'Impresa, 2013). Eco had a close relations- hip with the poetics of kinetic art (Eco and Munari, 1962). In fact, Eco’s vision became foundational for art critics’ interpretations of optical and kinetic art, which adopted the term open work.

The position of the viewer was one of the most impor- tant additions from the artistic field, as made clearby the Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel (GRAV) from its initiation (Aupetitaillot, 1998). For optical and kinetic artists, as well as for art critics, the viewer was considered to be a perceptive engine that triggered an aesthetic action in the artwork in motion. Op art tendencies were characterized by a preeminence of visuality and the participatory action of the viewer, and they used visual strategies based on the psycho- logy of perception, which is why they attracted the attention of Rudolf Arnheim, who showed interest in the relationship between art and visual perception (Arnheim, 1966). At the opening of The Responsive Eye, a group exhibition of artists with optical and kinetic tendencies held in 1965 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, Arnheim openly expressed –in the 1966 documentary edited by Brian de Palma about the exhibition– his fascination with this artistic movement, which exemplified his analysis of the psychology of vision (Abaton Book Company, 2011; Lagier, 2008).

The Responsive Eye, which responded to the percep- tive and receptive process of the time, was based on purely visual principles. Its curator, William Seitz, built his proposal based on the visual processes favored by the new trends. Without alluding to the current terminology of op art and kinetic art, Seitz coined the term perceptual art, which exalted the perceptual value of art and the visual process involved in creating it (1965). Focusing on the psychophysical studies of the late nineteenth century and Gestalt theory, Seitz combined different artistic movements that favored the study of perceptual phenomena and used them to vindicate the role of the observing eye (1965). This new label of perceptual art allowed Seitz (1965) to gather a selection of artworks organized under six headings, which grouped examples from European optical and kinetic art and examples of American pos- tpictorial abstraction. Although the concept failed to gain traction in other scholarly works at the time, The Responsive Eye marked the beginning of the interna- tionalization of optical and kinetic art and its spill-over into the worlds of fashion, television, and film. The multiplication of the op art phenomenon, as it was generally called, confronted viewers with a specific visual experience who were intentionally provoked by these objects (Borgzinner, 1964). The inclusion of the viewer at the center of the aesthetic experience was also part of the claims of other trends, such as the happening, the Fluxus movement, and conceptual art, which revealed the importance that the viewer had acquired in the avant-garde culture of the time.

Imagen 1. ArtBo (2018). Fotografía cortesía de la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá

All these movements were undoubtedly in line with the observations of art critics, who were sensitive to the borrowing and incorporation of components from a society in which visuality clearly overflowed the limits of artistic culture. The multitudinous diffusion and multiplication of images provided bytelevision and the media in general prompted a consi- deration of the role of the image which went beyond the limits established by traditional cultural criticism, which gave rise to a civilization of images, an unques- tionable change that has modified every aspect of society.

Like Huyghe, the aforementioned authors understood the significant transformations that had taken placein the reign of visuality, and they analyzed the impli- cations that this transformation would imply in the creation and interpretation of art. With this shift from object to subject, encouraged by aesthetic practices and art criticism, the viewer became a privileged subject in the aesthetic reflections of the 1960s. The viewer’s function and active process in the consump- tion of images were incorporated a few years later into new visions that would be developed in the field of art history starting in the 1970s.

From the viewer to visual culture

The progression of leftist politics and the perception of art criticism during the 1960s had a direct impact on the methodological practices of art history, which began to rethink its own identity in the 1970s. The rise of issues related to class, gender, and politics, along with a questioning of the nature of capitalism, catalyzed the development of the so-called new art history, which drew on Marxist methodologies, femi-nist critiques, and psychoanalytic analyses and helped dismantle, in the words of Griselda Pollock and Fred Orton, the “institutionally dominant history of art” (cited in Harris, 2001, p. 21).

Consideration of the viewer's awareness, which was common in artistic practices and art criticism even in the 1960s, began to gain importance in academic studies in the 1970s and 1980s. The studies carried out by Michael Baxandall (1988), Svetlana Alpers (1984), and Michael Zimmermann (1991) are impor- tant examples. Other research works, such as that ofMichael Fried (1990) and Jonathan Crary (1992), took the viewer as the primary subject. These authors dealt with different periods from varying perspectives,in which the viewer was a fundamental element of reflection, thus opening new methodological and interpretative directions within the discipline of art history. That is why some of the reflections of these authors –especially Alpers and Baxandall– were incor- porated into the category of new art history: they expanded the traditional theoretical and aesthetic limits. Moreover, they responded to the objections raised by Huyghe decades earlier and took up a line of thought that had developed in the critical and aes- thetic fields of the art world.

Despite their different approaches, all of these authors expressed their dissatisfaction with the tradi- tional methodologies of art and declared the need to expand the margins of the study of art history. In this way, their motivation was centered on a new reading of the art of the past through a distinct reflective approach. For instance, Zimmerman pointed out the inadequacy of traditional procedures when resear- ching George Pierre Seurat and contemporary art theory. Therefore, he proposed a fusion of history and philosophy. Zimmermann argued that, whatever the historical and philosophical orientation of the art historian, only the interpretation that brought toge- ther these two perspectives determined by differentmethodologies –that of social history and that of the history of ideas– could lead to satisfactory conclu- sions (Zimmerman, 1991). Baxandall considered his work to be a social history of pictorial style, opting for a study on the social factors in the configuration of Renaissance painting (1988). In all cases, the viewer and the visual experience of the time became basic elements of consideration in approaching artistic objects.

Understanding painting as a means of accessing visual customs and their corresponding social expe- rience led directly to the consideration and analysis of the role of the viewer. Thus, for Alpers (1984) and Baxandall (1988), the aesthetic experience of the viewer became the preferred object of study. For example, Baxandall conducted a study of fifteen-th-century Florentine paintings in which the expe- rience of the viewer in his or her confrontation of the painting was one of the central elements. The reflec- tion on what was seen by those who looked at such paintings in fifteenth-century Florence is developed in the second section of Baxandall’s book (1988). When discussing religious paintings, Baxandall reformulates his initial question about their religious function and suggests a relationship between the viewer and the image, thus making this question the starting point for reflection. Baxandall wrote (1988):

So the first question –What was the religious function of the religious paintings?– can be reformulated, or at least replaced by a new question: What sort of painting would the religious public for pictures have found lucid, vividly memorable, and emotionally moving? (p. 45)

These questions, which highlight the author's change in thought, are at the heart of Baxandall's analysis. His interest was in determining the public’s experience as they looked at the painting. This interest led himto ask himself what kinds of viewers existed, what their visual references were, what moved and inte- rested them, and, above all, what visual culture they were immersed in. Through an analysis of the visual culture of the fifteenth century, Baxandall arrivedat a new reading of Florentine painting, which then became part of the visual ensemble of the culture of images for a typical Florentine citizen (according to Baxandall, the merchant), which comprised painting and sculpture, as well as religious drama, theater, dance, and more.

Imagen 2. ArtBo (2018). Fotografía cortesía de la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá

Alpers extends Baxandall’s approach to sevente- enth-century Dutch painting. Her study focuses on the visual culture of the Netherlands, an expression she claims to take directly from Baxandall. For the author, Dutch painting must be studied by appealing to the circumstances. In this regard, Alpers proposes not only seeing art as a social manifestation but also accessing images through the consideration of their place, role, and presence in culture in broader terms (1984). The analysis of art then becomes a reasoned study of society and of the perceptive conception existing at the time, in clear relation to the scientific advances and psychological investigations of the time. By considering these new parameters, Alpers goes beyond the traditional sources of research anchored in the iconographic method and opensa new field of study that surpasses the framework of the artwork to consider the visual culture of the moment.

In this way, the need to use cross-references and different methodologies is satisfied, as is the case ofthe Baxandall, Alpers, and Zimmermann. Thus, their studies draw on a variety of sources that, in addition to integrating traditional historical sources in general and art historical sources more specifically, include sources from the history of science, literature, psy- chology, sociology, technology, and so forth. The relationship between art and scientific advances, developed by the psychology of perception or by optics, begins to comprise a significant amount of the literature. Alpers, for example, uses various sour-ces: from the biography of Constantijn Huygens, to Johannes Kepler's scientific treatise Ad vitellionem paralipomena, and to seventeenth-century Dutch car- tography (Alpers, 1984). On the other hand, Baxandall, questioning the experience of painting in the fifte- enth century, appealed to diverse sources, suchas sermons, religious dramas, dance treatises such as Trattato dell’arte del ballo by Guglielmo Ebreo Pesarese (from 1470), and mathematics textbooks like De arimethrica by Filippo Calandri (from 1491) (Baxandall, 1988). Baxandall takes these sources as a basis for approaching the visual culture of Florentine

Imagen 3. ArtBo (2018). Fotografía cortesía de la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá

society and, above all, for reconstructing the expe- rience of average viewers, an approach that yields new readings of Renaissance paintings. For example, it reveals relationships that, while absent today, were immediately apparent to the viewers in the fifteenth century, as Baxandall explains (1988):

In Florence there was a great flowering of religious drama during the fifteenth century […] Where they exist they must have enriched people’s visualization of the events they por- trayed, and some relationship to painting was noticed at the time. (p. 71)

One of these relationships was the figure of fes- taiuolo, derived from the name of the narrator in Renaissance theater present in both sacred drama and paintings, such as Filippo Lippi’s The Virgin Adoring the Child (c. 1465). The figure of festaiuolo reproduced in the painting clearly appealed to the average viewer, who would have perceived such figure through his or her experience of the festaiuolo (Baxandall, 1988; Fondaras, 2011). That is why, beingimmediately related to Renaissance religious dramas, the figure was understood in the pictorial field as a natural figure mediating between the viewer and the scene, catching the beholder’s eye, and pointing to the central action of the image (Fondaras, 2011).

The study of optics and scientific knowledge about perception, the configuration of the eye, and the functioning of vision also recur in the studies of Baxandall, Alpers, and Zimmermann. The choiceto take a key personality in the scientific thought of the era under study as an example, as well as to deal with the perceptual processes and scientific knowledge of optics, is common among some ofthese studies. For instance, in his analysis of Seurat’s work, Zimmermann (1989) references the writings of Charles Henry, Charles Blanc, and Gustave Kahn. Zimmermann’s interest in Henry, which is paralleled by Alpers’s interest in Huygens, is based on Henry’s ability to exemplify the image of the human being–or, we could say, the typical viewer– by represen- ting humanity’s set of beliefs and knowledge at thetime. For Zimmermann, Henry’s aesthetic is part of an image of humanity that predominated in France at the beginning of the Third Republic and, more particularly, during the 1880s (Zimmermann, 1991). For Alpers, Huygens represents something similar because Huygens “testifies” –which is confirmed by the society around him– that his images were part ofa visual specificity that contrasted with textual culture (Alpers, 1984, p. xxiv).

The conclusions of these authors offer a perspec- tive that goes beyond the position of art in society, beyond the uses of art, and beyond the aesthetic proposals of art, since they all show different ways and means to look, the characteristics of perceptive culture, and the aspects that are fundamental to understand the vision of the artist and the audience. These results are not a historical study of facts and commands; they are, as Alpers argues, a history of visual culture.

In the studies discussed above, the intention to overcome traditional interpretations is frequently manifested. The introduction of new perspectives of historical time also provides readings that contradict interpretations based on stylistic or formalist prin- ciples. A clear example in this is Alpers’s The Art of Describing (1984), in which she questions the traditio- nal analyses of seventeenth-century Dutch painting that strove to justify such painting’s belonging with an Italian narrative system of representation, whose moti- vations were not primarily visual but textual. Alpers argues that the imposition of the Italian model and the preeminence of iconographic methodologies has led to erroneous interpretations of Dutch paintings. These readings are a literary imposition alien to sevente- enth-century Dutch culture, which was essentially a culture of images. Specifically, Alpers argues (1984):

Iconographers have concluded that Dutch realism is only an apparent or schijn realism. Far from depicting the “real” world, so this argument goes, such pictures are realizedabstractions that teach moral lessons by hiding them beneath delightful surfaces. Don’t believe what you see is said to be the message of the Dutch works. But perhaps nowhere is this “transparent view of art”, in Richard Wolheim’s words, less appropriate. For, as I shall argue, northern images do not dis- guise meaning or hide it beneath the surface but rather show that meaning by its very nature is lodged in what the eye can take in. (p. xxiv)

In contrast to traditional studies, Alpers’s work propo- ses a different reading of Dutch art, in which paintings are studied in the context of the visual images that proliferated at the time when they were created. As previously mentioned, Alpers starts from the figureof Huygens, an example par excellence of the seduction that image and optics produced in seventeen-th-century Dutch art. Indeed, throughout her work, it is clear that the nonconformity of Dutch painting to the Italian Renaissance canon is related, amongother reasons, to the reliance on optics and lenses in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century. Indeed, Alpers states (1984):

The Dutch present their pictures as describing the world seen rather than as imitations of significant human actions. Already established pictorial and craft traditions, broadly reinforced by the new experimental science and technology, confirmed pictures as the way to new and certain knowle- dge of the world. (p. xxv)

This type of methodology, which is inscribed in the study of contemporary art –where the problems of visuality and the integration of the virtual and the digital are determinant for artistic creation– was also present in other periods of history, that is, although some of the examples we have cited deal with the- mes from the impressionist era to the present day, a period in which scientific developments have been of vital importance for the creation of art, this method is also valid for other periods of history, as shown by the studies of Alpers and Baxandall. Hence, we have preferred to focus on studies that deal with periods preceding the nineteenth century.

It is evident that, with the publication of those studies in the 1980s, we find ourselves dealing with a new type of art history –the so-called new art history– which proposes a way of looking at and interpreting art and society which is linked to visual studies. In this way, Alpers and Baxandall, for instance, become illustrious forerunners of what William John Thomas Mitchell calls the “pictorial turn” (as cited in Curtis, 2009, p. 95). However, although their works have opened up new methodological and epistemolo- gical possibilities, they are part of a (re)thinking of the relationships among art, culture, and society that connects the critical analysis and artistic practices of the 1950s and 1960s with the new historiographical discourses that opened up the postmodern period, thus demonstrating the permeability among all these spheres.

References

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2022 Mei-Hsin Chen

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

Licencia actual vigente

Creative Commons BY NC SA - Atribución – No comercial – Compartir igual. Vigente a partir del Vol. 17 No. 32: (julio-diciembre) de 2022.

This work is licensed under a https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.es

Licencias anteriores

- Desde el Vol. 14 Núm. 25 (2019) hasta el Vol. 17 Núm. 31: enero-junio de 2022 se utilizó la licencia Creative Commons BY NC ND https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.es

- Desde el Vol 1 Num 1 (2007) hasta el Vol. 13 Núm. 23 (2018) la licencia fue Creative Commons fue Reconocimiento- Nocomercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/co/