DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/21450706.19624Publicado:

2022-07-22Número:

Vol. 17 Núm. 32 (2022): Julio-Diciembre 2022Sección:

Sección CentralFlor-libertad, fuego-imaginación, fuerza-unidad, revolución-arte: el simbolismo de la guerrilla cultural en el proceso revolucionario portugués (1974-1976)

Flower Freedom, Fire Imagination, Strength Unity, Art Revolution: The symbolism of cultural guerilla in the Portuguese revolutionary process (1974-1976)

Flor-liberdade, fogo-imaginação, força-unidade, revolução-arte: o simbolismo da guerrilha cultural no processo revolucionário português (1974-1976)

Palabras clave:

Portuguese revolution, socially committed artist practices, cultural guerrilla, Cold War (en).Palabras clave:

Revolução portuguesa, práticas artísticas socialmente comprometidas, guerra cultural de guerrilha, Guerra Fria (pt).Palabras clave:

revolución portuguesa, prácticas artísticas socialmente comprometidas, guerrilla cultural (es).Descargas

Referencias

Uma casa para a Arte Moderna (1975, April, 15). Sempre Fixe.

Manifesto de Artistas no 1.º de Maio (1976, May, 4). Diário de Lisboa, 14.

Abreu, J. G. R. P. (2017). Public art as a means of social interaction: From civic participation to community involvement. In UNESCO (Eds.), Actes du Colloque International "Quel destin pour l’Art Public"[Paris, France], 19-20 Mai 2011 (pp.159-174). Paris, France: Centre du Patrimoine Mondial de L’UNESCO.

Abreu, J. G. R. P. (2006). Escultura Pública e Monumentalidade em Portugal (1948-1998) [Unpublished doctoral thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa].

Almeida, S. V. de (2009). Camponeses, Cultura e Revolução: Campanhas de Dinamização Cultural e Acção Cívica do M.F.A. (1974-1975). Lisbon, Portugal: Edições Colibri and IELT – Instituto de Estudos de Literatura Tradicional.

Arquivos RTP (1974). Reunião de individualidades com a Junta de Salvação Nacional. https://arquivos.rtp.pt/conteudos/reuniao-de-individualidades-com-a-junta-de-salvacao-nacional/

Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (1974). Flor liberdade, fogo imaginação, força unidade, arte revolução / Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos. https://purl.pt/7558

Caeiro, M. (2014) Arte na Cidade: História Contemporânea. Lisbon, Portugal: Círculo de Leitores.

Carvalho, L. (1975, Janeiro, 24). Grupo ACRE afirma: Arte deve ser usada como ferramenta. A Capital.

Celant, G. (2020). In memory of Germano Celant: Arte povera. Notes on a guerrilla war. https://flash---art.com/article/germano-celant-arte-povera-notes-on-a-guerrilla-war/

Correia, R., and Gomes, V. (1984) Livro Branco da 5ª Divisão 1974-75. Brasilia, Brazil: Ler Editora.

Couceiro, G. (2004) Artes e Revolução 1974-1979. Lisbon, Portugal: Livros Horizonte.

Cruzeiro, C. P. (2021). Art With Revolution! Political Mobilization in Artistic Practices Between 1974 and 1977 in Portugal. On the W@terfront, 63(10), 3-35. https://doi.org/10.1344/waterfront2021.63.10.01

Dias, F. R. (2014). Dois momentos históricos da performance no Chiado: as acções futuristas e o Grupo Acre. In J. Quaresma (Coord.), O Chiado da dramaturgia e da performance (pp. 40-71). FBA-CIEBA.

Freitas, A. (2007). CONTRA-ARTE: vanguarda, conceitualismo e arte de guerrilha 1969-1973 [Unpublished doctoral thesis, Universidade Federal do Paraná].

Galimberti, J. (2017). Individuals against Individualism. Art Collectives in Western Europe (1956-1969). Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press.

Gonçalves, E. (1974). Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos: A intervenção necessária. Flama, 1378, 38-42.

Gonçalves, R. M. (1980). Carta de Lisboa. Colóquio/Artes, 47, 64.

Gonçalves, R. M. (2004). Vontade de mudança: Cinco décadas de artes plásticas. Lisbon, Portugal: Editorial Caminho.

Habermas, J., Lennox, S., and Lennox, F. (1974). The public sphere: An encyclopaedia article. New German Critique, 3, 49-55. https://doi.org/10.2307/487737

Hobsbawm, E. (1996). A Era dos Extremos, História Breve do Século XX. Lisbon, Portugal: Editorial Presença.

Le Parc, J. (2014) Guerrilla Cultural. Julio Le Parc. http://julioleparc.org/guérilla-culturelle.html

Loff, M. (2006) Fim do Colonialismo, ruptura política e transformação social em Portugal nos anos setenta. In M. Loff and M. da C. M. Pereira (Eds.), Portugal: 30 anos de democracia (pp.153-194). Porto, Portugal: Editora da Universidade do Porto.

Loff, M. (2008). O nosso século é fascista! O mundo visto por Salazar e Franco (1936-1945). Porto, Portugal: Campo das Letras.

López, P. B. (2015). Collectivization, participation and dissidence on the transatlantic axis during the Cold War: Cultural Guerrilla for destabilizing the balance of power in the 1960s. Culture & History Digital Journal, 4(1), e007. https://doi.org/10.3989/chdj.2015.007

Madeira, C. (2020). Arte da Performance, made in Portugal: uma aproximação à(s) história(s) da arte da performance portuguesa. Lisbon, Portugal: Livros ICNOVA.

manuel pires (2015, November 25). PAINEL do 10JUNHO 74 [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7KlT8tsSZ2w

Morais, F. (1970). Contra a arte afluente. Documents of Latin American and Latino Art. https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/item/1110685#?c=&m=&s=&cv=3&xywh=-1116%2C0%2C3930%2C2199

Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos (1974a). A Arte fascista faz mal à vista. Flama, 1370, 40-41.

Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos (1974b). Cartaz do MDAP em Solidariedade com o MFA. https://www.tchiweka.org/iconografia/7002000036

Oliveira, L. de (2013). Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Serralves: Os Antecedentes, 1974-

Lisbon, Portugal: Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda.

Pignatari, D. (2004). Teoria da guerrilha artística. In D. Pignatari (Ed.), Contracomunicação (pp. 167-176). São Paulo, Brazil: Ateliê Editorial.

Pimenta, F. T. (2022). A ideologia do Estado Novo, a guerra colonial e a descolonização em África. In J. P. Avelãs Nunes and A. Freire (Ed.), Historiografias Portuguesa e Brasileira no século XX Olhares cruzados (pp. 183-201). Coimbra, Portugal: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Rosas, F. (1998). O Estado-Novo (1926-1974). In J. Mattoso (Ed.), História de Portugal. Lisbon, Portugal: Editorial Estampa.

Sousa, E. de (1975, January 23). O grupo ACRE e a apropriação, Vida Mundial, 41-42.

Torgal, L. R. (2009). Estados Novos, Estado Novo. Ensaios de História Política e Cultural. Coimbra, Portugal: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Wood, P. (2002). Conceptual Art: Movements in modern art. London, UK: Tate Publishing.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Flor-libertad, fuego-imaginación, fuerza-unidad, revolución-arte: el simbolismo de la guerrilla cultural en el proceso revolucionario portugués (1974-1976)

Flower Freedom, Fire Imagination, Strength Unity, Art Revolution: The symbolism of cultural guerilla in the Portuguese revolutionary process (1974-1976)

Fleur-liberté, feu-imagination, force-unité, révolution-art : la symbolique de la guérilla culturelle dans le processus révolutionnaire portugais (1974-1976)

Flor-liberdade, fogo-imaginação, força-unidade, revolução-arte: o simbolismo da guerrilha cultural no processo revolucionário português (1974-1976)

Flor-libertad, fuego-imaginación, fuerza-unidad, revolución-arte: el simbolismo de la guerrilla cultural en el proceso revolucionario portugués (1974-1976)

Calle14: revista de investigación en el campo del arte, vol. 17, núm. 32, 2022

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional.

Recepción: 15 Diciembre 2021

Aprobación: 04 Abril 2022

Resumen:

El 25 de abril de 1974, la revolución portuguesa acabó con una dictadura fascista que había durado 48 años. En el contexto político y social global de la Guerra Fría, la nueva situación del país se entendió como una victoria para el movimiento antimperialista y anticapitalista, particularmente en Europa. Este artículo analiza las prácticas artísticas llevadas a cabo durante el proceso de revolución portugués (1974-1976), específicamente la adopción simbólica de una estrategia de guerrilla en las artes: una guerrilla cultural. En primer lugar, el artículo introduce el tema y se pregunta cómo una guerrilla cultural era relevante en el contexto artístico nacional durante el periodo estudiado, asumiendo el colectivismo como la característica básica y esencial de la estrategia. A esto le sigue una discusión sobre las formas de autoorganización y acción directa lideradas por los colectivos. En esta línea, la estrategia de una guerrilla cultural se utilizó en articulación con los centros de decisión política como medio para proyectar las voces de los artistas en la esfera político-social. La conclusión subraya las circunstancias extraordinarias de Portugal en el contexto político y social de la Guerra Fría y la relevancia de las prácticas artísticas durante el periodo en aras de un entendimiento internacional de la temática.

Palabras clave: revolución portuguesa, prácticas artísticas socialmente comprometidas, guerrilla cultural, Guerra Fría.

Abstract:

The Portuguese revolution, on April 25th, 1974, ended a fascist dictatorship that had lasted for forty-eight years. In the political and social global context of the Cold War, the country's new situation was understood as a victory for the anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist movement, particularly in Europe. This article will analyse the artistic practices during the Portuguese revolutionary process (1974-1976), particularly the symbolic adoption of a guerrilla strategy within the arts: a cultural guerrilla. First, the article introduces the topic and ask how acultural guerrilla was relevant within the national artistic context during the period in focus, assuming collectivism as the strategy's basic and essential characteristic. This is followed by a discussion of forms of self-organization and direct action led by collectives. In this regard, the strategy of cultural guerrilla was used in articulation with the centres of political decision, as a means of projecting the voices of artists into the political-social sphere. The conclusionunderlines the extraordinary context of Portugal in the political and social context of the Cold War and the relevance of artistic practices in this period towards international understanding of the topic.

Keywords: Portuguese revolution, socially committed artist practices, cultural guerrilla, Cold War.

Résumé: Le 25 avril 1974, la révolution portugaise a mis fin à une dictature fasciste qui avait duré 48 ans. Dans le contexte politique et social mondial de la guerre froide, la nouvelle situation du pays était comprise comme une victoire du mouvement anti-impérialiste et anticapitaliste, en particulier en Europe. Cet article analyse les pratiques artistiques menées pendant leprocessus de la révolution portugaise (1974-1976), en particulier l'adoption symbolique d'une stratégie de guérilla dans les arts : une guérilla culturelle. En premier lieu, l'article introduit le sujet et demande comment une guérilla culturelle était pertinente dans le contexte artistique national au cours de la période étudiée, en assumant le collectivisme comme caractéristique fondamentale et essentielle de la stratégie. Ceci est suivi d'une discussion sur les formes d'auto-organisation et d'action directe dirigées par des collectifs. Dans cette ligne, la stratégie d'une guérilla culturelle a été utilisée en articulation avec les centres de décision politique comme moyen de projeter la voix des artistes dans la sphère politico-sociale. La conclusion souligne les circonstances extraordinaires du Portugal dans le contexte politique et socialde la guerre froide et la pertinence des pratiques artistiques au cours de la période pour une compréhension internationale du sujet.

Mots clés: Révolution portugaise, pratiques artistiques socialement engagées, guérilla culturelle, Guerre froide.

Resumo:

Em 25 de Abril de 1974, a revolução portuguesa acabou com uma ditadura fascista que havia durado 48 anos. No contexto político e social global da Guerra Fria, a nova situação no país se entendeu como uma vitória para o movimento anti-imperialista e anticapitalista, particularmente na Europa. Este artigo analisa as práticas artísticas realizadas durante o processo de revolução portuguesa (1974-1976), especificamente a adoção simbólica de uma estratégia de guerrilha nas artes: uma guerrilha cultural. Em primeiro lugar, o artigointroduz o tema e se pergunta como uma guerrilha cultural foi relevante no contexto artístico nacional durante o período estudado, assumindo o coletivismo como a característicabásica e essencial da estratégia. A isto segue-se uma discussão sobre as formas de auto- organização e de ação direta liderada por coletivos. Nesta linha, a estratégia de uma guerrilha cultural foi utilizada em articulação com os centros de decisão política como meio para projetar as vozes dos artistas na esfera sócio-política. A conclusão sublinha as circunstâncias extraordinárias de Portugal no contexto político e social da Guerra Fria e a relevância das práticas artísticas durante o período para um entendimento internacional da temática.

Palavras-chave: Revolução portuguesa, práticas artísticas socialmente comprometidas, guerra cultural de guerrilha, Guerra Fria.

Introduction

During the 1950s and 1970s, artistic practices in various countries around the world adoptedmethods, procedures, and forms of action associa- ted with the sphere of political struggle. Avant-garde movements had already tested this approach, but, during this period, there was a radicalization ofthis association, with the adoption of the specific mechanisms of direct political action. This association introduced the term guerrilla into the arts lexicon,in some cases interwoven with the development of conceptualism in the arts (Wood, 2002), in others with the social and political reality. This term, like vanguard, has connotations with warfare, even though, unlike the latter, it assumes a disassociation from a coun- try's military organization. Guerrilla warfare is usually carried out in opposition to the established power, with few human, financial and technical resources, which implies combat tactics such as sabotage, an underground organization, or proximity to local populations, gaining their support, protection, and trust. The intention is to distract, tire, disorient or demobilize the enemy. Given the scarcity of resour- ces, this implies imagination and creativity.

After World War II, the guerrilla strategy was com- mon knowledge in various regions of the world. In the 1950s and 1960s, several movements used this strategy in countries as diverse as Malaysia, Kenya, Cyprus, Spain, Vietnam, Cuba, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Guatemala, Argentina, Brazil, Nicaragua, Angola, Guinea, and Mozambique. Among them, the Viet Cong or National Liberation Front for South Vietnam (NLFSV) and the guerrilla movement that led the Cuban Revolution gained great global renown. As mentioned by Paula Barreiro López, these guerrilla movements, in association with the anti-imperialist struggle,

[...] had shown that tactics such as sabotage, ambushes or raids could have a decisive impact on fighting traditionally organized, larger, and militarily superior troops –and that they were quite effective for confronting the US hegemony and destabilizing the balance of power during the Cold War. (2015, p. 2)

In fact, during this period, the Cold War dominated the international political scene, with the US and the USSR representing polar opposite worldviews. While the imperialist worldview was dominant in Europe–with the exception of some territories such as Germany, where the USSR had partial influence, and Austria, which remained neutral (Hobsbawm, 1996)– this dominance was less clear outside of Europe, for example in Latin America. There, the struggle for the geo-strategic domination of the imperialist worldview led to the emergence of various fascist regimes and military coups, some with the clear support of the US, as is the case of Chile.

Although, in the 1970s, some revolutions positioned themselves ideologically against imperialist rule1, the political imaginary linked to the anti-imperialist struggle remained strongly associated with guerrilla warfare (Hobsbawm, 1996), even in countries whereit did not exist. Noteworthy examples include the stu- dent movements of May 68, in France (1968) and Italy (1969) which, inspired by this imaginary, adopted the tactics of direct action and urban guerrilla warfare.

The migration of the guerrilla strategy to the arts is partially justified by this political-social context. In various regions of the world, artists, critics, art histo- rians, and other intellectuals were mobilized to act politically. This action was characterized to a large extent by proposals of resistance and direct action within the artistic system (Freitas, 2007; López, 2015), such as those developed in the written texts of Décio Pignatari, Germano Celant, or Júlio Le Parc among others, which called for the constitution of a cultural guerrilla. These writings can be associated with the period's artistic avant-garde movements, but they are addressed to their peers, in the tone of a manifesto, using a language and political structure that defends direct action.

In 1967, Décio Pignatari wrote in Teoria da Guerrilha Artística that "nothing is more like a guerrilla than the self-conscious artistic avant-garde", which "today stands against the system" (2004, p. 169). During that same year, Germano Celant published the manifesto Arte Povera. Appunti per una guerriglia in the maga- zine Flash Art, which stated that "society presumes to make pre-packaged human beings, ready for consumption. Anyone can propose reform, criticize, violate, and demystify, but always with the obligation to remain within the system. [...] To exist from outside the system amounts to revolution" (2020). Therefore, Celant argued that "no longer among the ranks of the exploited, the artist becomes a guerrilla fighter, capable of choosing his places of battle and with theadvantages conferred by mobility, surprising and stri- king, rather than the other way around" (2020).In 1968, influenced by the political stances he had observed in South America, Júlio Le Parc published Guérilla Culturelle, where he stated that it was neces- sary "to reveal the existing contradictions within each medium. Develop an action so the same people pro- duce change" (2014). Le Parc considered that

in intellectual and artistic production there are two well-di- fferentiated attitudes: all those that –voluntarily or not– help maintain the structure of existing relations, preserve the cha- racteristics of the current situation; those initiatives, deliberate or not, scattered a little everywhere, that try to undermine relationships, destroy the mental schemes and behaviours the minority relies on to dominate. These are the initiatives that should be developed and organized. (2014)

To this end, he said it was necessary "to organize a kind of cultural guerrilla against the current state of affairs, to highlight contradictions, to create situations where people rediscover their ability to produce changes" (Le Parc, 2014).

The three texts evoked here, published in distinct contexts, namely Brazil, Italy, and France, focus on the artist's political action and not on aesthetic action.

They question the artist's responsibility as a citizen, an agent of political intervention within his/her social group and in the environment where he/she works, thereby participating directly in the sought-after social transformation. Political intervention with a socio-cultural fabric, as suggested in the three exam- ples, should be based on guerrilla tactics against the cultural system, an integral part of the broader macro- cosm of society.While the links to guerrilla strategy in the artistic context are evident at the symbolic and discursive levels, its conversion into practice is more complex. Nevertheless, collective action, citizen participation and direct communication in the public space –such as the distribution of communiqués and pamphlets, agit-prop, murals and street performances– can be understood as guerrilla tactics within the arts.

In Portugal, the more direct and profound knowledge of guerrilla strategy came from the Portuguese experience in the colonial war. The colonialist and impe- rialist policy of the fascist dictatorship2 was a central factor of the regime. Since its formation, it sought to "safeguard the Portuguese colonial heritage from foreign ambitions and convert it into a great Empire" (Pimenta, 2022, p. 188). Thus, since 1961, it fiercely fought the liberation movements of the colonized African countries, such as Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea. These movements3 used guerrilla tacticsin their fight against Portuguese troops, who were largely soldiers forced by the Portuguese govern- ment to fight in the colonies. The colonial war was one of the regime's main factors of attrition and, at the same time, one of the main promoters of the captains’ movement that led the revolution in the homeland.The Portuguese revolution of April 25, 1974, was carried out by the Movimento das Forças Armadas (MFA, Armed Forces Movement) with the immediate support of the popular democratic movement.

Until the inauguration of the First Constitutional Government, following the first legislative elections on April 25, 1976, Portugal was governed by six Provisional Governments4, which had to implement the MFA's Program. The revolutionary process between 1974 and 1976 was complex and included periods of great intensity (Loff, 2006). However, it can be characterized by the desire to install an anti-ca- pitalist democracy towards the creation of a socia- list society, a desire that remains expressed to this day in the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic (Cruzeiro, 2021).

The guerrilla imaginary that assaulted the European intellectual circles within the anti-imperialist struggle, which was circulated in Portugal before the revolution5, was reinforced by the colonial war’s proximity. Nevertheless, it gained greater expression and visibility during the revolutionary process. In contrast to what happened in other European countries, the cultural guerrilla was adopted in Portugal between 1974 and 1976, largely as a strategy to support the revolutionary process. Collective organization, participation, and action in the political-social sphere, characteristics of the conceptual configu- ration of the cultural guerrilla (López, 2015), were adopted by several Portuguese artists and collectives that, in this way, integrated the country's panorama of artistic practices during this period.

Collective action and guerrilla strategy during the Portuguese revolutionary process (1974-1976)

Between the 1950s and 1970s, in the context of artistic practices, collectivism was closely related, on the one hand, to the fight against individualistic, existen- tialist, and autonomous conceptions of modern art; and, on the other hand, to the context of the Cold War and its ideological polarization between theUS and the USSR (Galimberti, 2017). In this context, "individual as well as collective, to a large extent, became associated with those two political, inte- llectual and cultural systems and naturally opposed" (López, 2015, p. 3). Examples include collectives such as Spur, N (Padua, Italy), T (Milan, Italy), Equipo 57 (France and Spain), Equipo Crónica (Valencia, Spain), Equipo Córdoba (Cordoba, Spain), Internationale Situationniste (France), GRAV (France), and Komunne I (East Germany), whose performance sought effectsin the cultural arena, but simultaneously in the political and social ones.

In Portugal, the fascist dictatorial regime did not allow the dynamic constitution of artistic collecti- ves. However, the artistic field legitimized by the fascist State coexisted with a marginal artistic field, from which some groups arose, such as the Grupo Surrealista de Lisboa (Surrealist Group of Lisbon, 1947) –which, after some tensions, led to the forma- tion of Os Surrealistas (The Surrealists)–, the 21G7 group (1960), the group associated with the Poesia Experimental (Experimental Poetry) magazine and PO.EX (1963), or the Os Quatro Vintes (Four Twenties, 1968). Although these collectives had different moti- vations, and not all of them were focused on political resistance to the regime, several intellectuals and artists were part of this struggle, either individuallyor by integrating anti-fascist movements, such as the Movimento de Unidade Democrática (Movement for Democratic Unity, MUD). Nevertheless, freedom of association was severely limited, and the formation of artistic collectives, particularly socially commit- ted groups, was therefore residual, which is why the collectivist movement in Portugal only arose in all its vigor with the Portuguese revolution.

The period between 1974 and 1976 was fertile for collectivism. Collective organization was used both for creative purposes and for political and social issues. Examples within the wider field of artistic and cultural expression include, among others,the Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos (Democratic Movement of Visual Artists, MDAP, 1974), the Frente de Acção Popular de Artistas Plásticos (Popular Action Front of Visual Artists, FAPAP, 1974), the ACRE group (1974), the Comissão para uma Cultura Dinâmica (Commission for a Dynamic Culture, 1974), the Movimento Unitário dos Trabalhadores Intelectuais para a Defesa da Revolução (United Movement of Intellectual Workers for the Defense of the Revolution, MUTI, 1975), the Puzzle group (1976), the Colectivo 5+1 (Collective 5+1, 1976), the Cores/ GICAP (Colors/GICAP, 1976), and the IF – Ideia e Forma group (IF – Idea and Form, 1976). During the same period, several cultural and recreational associa- tions arose –as well as cooperatives– which had seve- ral artists in their governing bodies (Cruzeiro, 2021).

A strategy of cultural guerrilla, as a form of collective action, was promoted by the desire of artists and intellectuals for self-organization and direct action. That action was characterized by the use of imme- diate and impactful tactics to intervene in the public space and the public sphere. This action was foste- red by the revolutionary atmosphere, "which bends predictability in order to intensify the moment's tense experience" and produces "an a-legal period that allows another adventure in actions" (Dias, 2014, p.42). The strategy was used immediately after the revo- lution, while its presence is residual among collecti- ves formed after 1976.

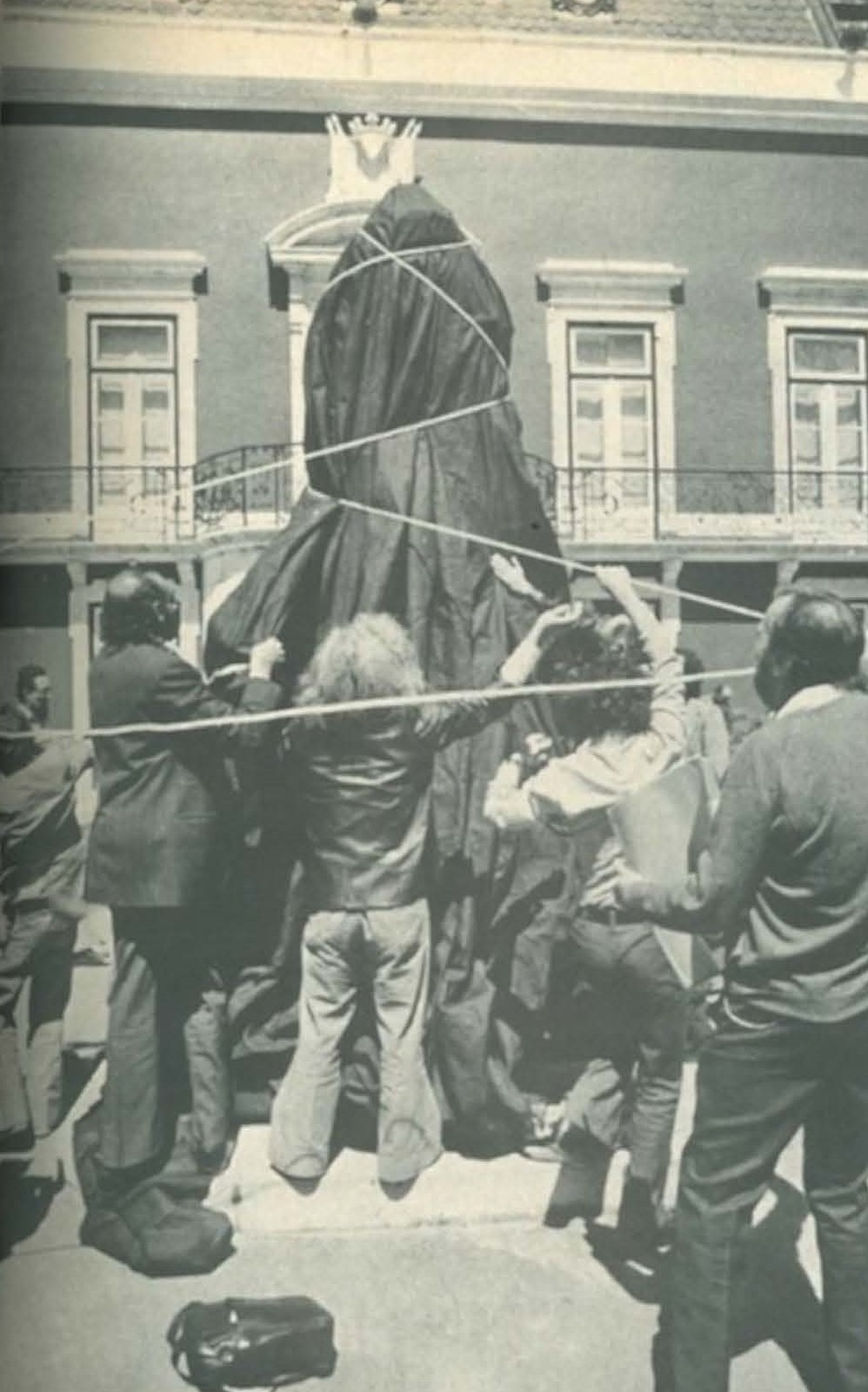

Figure 1. ACRE group, intervention in Torre dos Clérigos (Porto) Source: Lima Carvalho collection

The guerrilla strategy's corresponding performati- vity was diverse and sought a wide range of effects. The notion of performativity comprises the beha- vior adopted in the various spheres of life and their different circumstances. In the country's developing political-social framework, paving new avenues of possibility, this behavior reflected artists’ desire to act in the present, thus contributing to producing and experiencing change. This experience of the immediate and urgent led to a performativity based on the body's direct involvement in action and the lived experience. In most cases, in accordancewith the project of society being defended, the motive for action was the collective –and not the individual– project.

Figure 2. ACRE group, occupation of the Palácio Mendonça (Lisbon) Source: Uma casa para a Arte Moderna (1975, April, 15)

The experience of the revolutionary moment legi- timized a radical performativity, for example, in the actions of the ACRE group (1974-1977), formed bythe artists Lima Carvalho, Clara Menéres, and Alfredo Queiróz Ribeiro.6The group's artistic practice was characterized by performances of political interven- tion, the publication of communiqués and documents attributing a fictitious legal authority to the group, and interventions in the public space and by evoking this same space. The practice of cultural guerrilla tactics pervaded most of the group's activity, particularlythe clandestine nature of their interventions. The first, held in Rua do Carmo (Lisbon), inaugurated the"urban and guerrilla dimension" (Dias, 2014, p. 65) that the group would later intensify. Large yellow and pink circles were painted on this street's sidewalk during the night, "without permission from anyone" and illegally interrupting road traffic with a fake traffic sign made by Lima Carvalho.7 Also clandestine was the intervention in Torre dos Clérigos (Porto), on October 25, 1974, which consisted of placing a 75-meter-long yellow plastic sleeve under the building. Lima Carvalho recalls that "for weeks, when going to Porto, I studied the movement around the Tower – the movement of the priest, the sexton, the tourists... – to know when we could attack, so as not to fail".8

Expressing the desire of artists and other intellectuals since the revolution to build a museum for contem- porary art9, the occupation of the Palácio Mendonça (Lisbon), uninhabited at the time, was one of ACRE’s most representative guerrilla actions. On April 18, 1975, Lima Carvalho and Clara Menéres, accompa- nied by other citizens, entered the palace and pla- ced some cloth banners, re-naming it the Museum of Modern Art (Uma casa para a Arte Moderna, 1975).The building's occupation lasted that afternoon, ending with the intervention of the Military Police and the arrest of ACRE members.

Frederico Morais astutely observed the intersection of procedural and conceptual artistic practices with the guerrilla strategy, stating that "if art has become enmeshed in the day-to-day, by denying the specific and the medium, it can also be confused with the protest movements" (Morais, 1970, p. 56). Thus, art is "a form of ambush" and the artist "a kind of guerrilla" whose task is to create "nebulous, unusual, indefi- nite situations" for the spectator (Morais, 1970, p.49).

ACRE's actions can thus be characterized in this art-life binomial that acts within the artistic system, even though actions take place in the street. The Portuguese critic and multidisciplinary artist Ernesto de Sousa considered that, with ACRE, there was "a convergence that [led] to unstoppable results: convergence with modernity, the avant-garde", insinuating that although the "project, the idea asan aesthetic object", was not new, it had not been understood by most Portuguese contemporary artists (Sousa, 1975, p. 41).

Ernesto de Sousa was referring to Portuguese per- formance art –so-called since the 1960s and1970s (Madeira, 2020)– that blossomed after the Portuguese revolution. The liberated bodily action, which it represents, was eventually stimulated by the coun- try's new liberated condition. Freedom manifested reflexively, and its performative attitude embodied in turn a political attitude that, in this regard, elected the symbolism of the cultural guerrilla as a form of privileged action without, however, seeking to interfere in the country's cultural policy in any permanent way.

The cultural guerrilla in dialogue: the MDAP in alliance with the political decision centres

During the Portuguese revolutionary process, there was a complex but intense process towards the democratization of art and culture in general. One of the main actions of some cultural institutions and artistic collectives involved discussing how to "inter-fere in cultural policy" as stated by art critic Rui Mário Gonçalves (1980, p. 64), seeking to contribute tothe definition of the country's cultural policy. In this regard, the guerrilla strategy went beyond a symbolic character in some cases, and assumed self-organi- zation as a way into the public sphere and political decision-making. The performativity adopted, inthis case, was not characterized by merely taking a position, but also by insertion into the political deci- sion-making centers. The attitude was mostly colla- borative (Cruzeiro, 2021) and focused, for the most part, on dialogue and negotiation with the political power that emerged after the revolution, namely the National Salvation Junta (JSN)10 and the Provisional Governments that were constituted before the first democratic elections.

The MDAP was, in this regard, the first organized group of artists to play a prominent role in the efforts towards the construction of a “more general plan of cultural democratization”, as mentioned by Eurico Gonçalves (1974, p. 38). This movement established a direct dialogue with governmental structures, acting on the level of organized politics, and carried out a series of actions in the public space that were funda- mental to this context, such as drafting communiqués with proposals for the cultural sector, promoting working groups and organizing collective artistic initiatives (Gonçalves, 1974).

Constituted by dozens of artists11, who were mem- bers of the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes (SNBA, National Society of Fine Arts)12, the MDAP was created

The MDAP's actions took place mainly in Lisbon, although its proposals had a national scope. The movement's first communiqué, issued on May 9, 1974, was a manifesto defending politicized cultural intervention. In it, the movement proposed a series of measures aimed at building a new cultural policy, as well as extinguishing any remnants of structures and activities associated with the fascist dictatorial regime, which includes abolishing the fascist struc- tures of public bodies dedicated to the Fine Arts13, firing its officials and terminating “all commissions that censor and control the integration of works of art in public space” (Gonçalves, 1974, p. 40). They proposed the "immediate cancellation of the current program of exhibits” and holding an exhibit on poli- tical repression in the arts, as well as compiling an inventory of the artistic heritage (Gonçalves, 1974, pp. 39-40). On the next day, representatives of the MDAP met with members of the JSN to discuss issues associated with the sector of fine arts. Following the meeting, one of the MDAP's representatives issueda statement on national television (RTP), arguing thatthe movement had

two main concerns: nothing should be done in the field of fine arts without hearing the class's representatives; we also want to contact all similar movements, associations of writers, musicians, so as to form a relationship among the people involved in Portuguese cultural life. (Aquivos RTP, 1974)

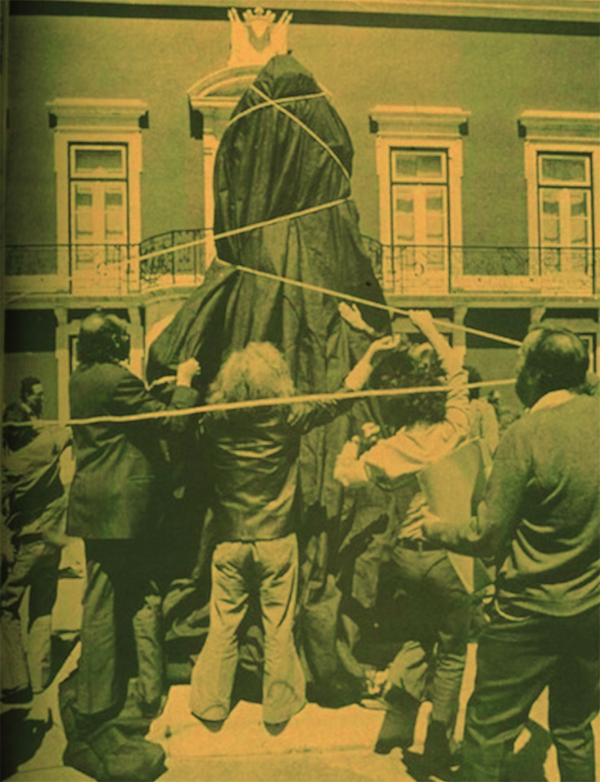

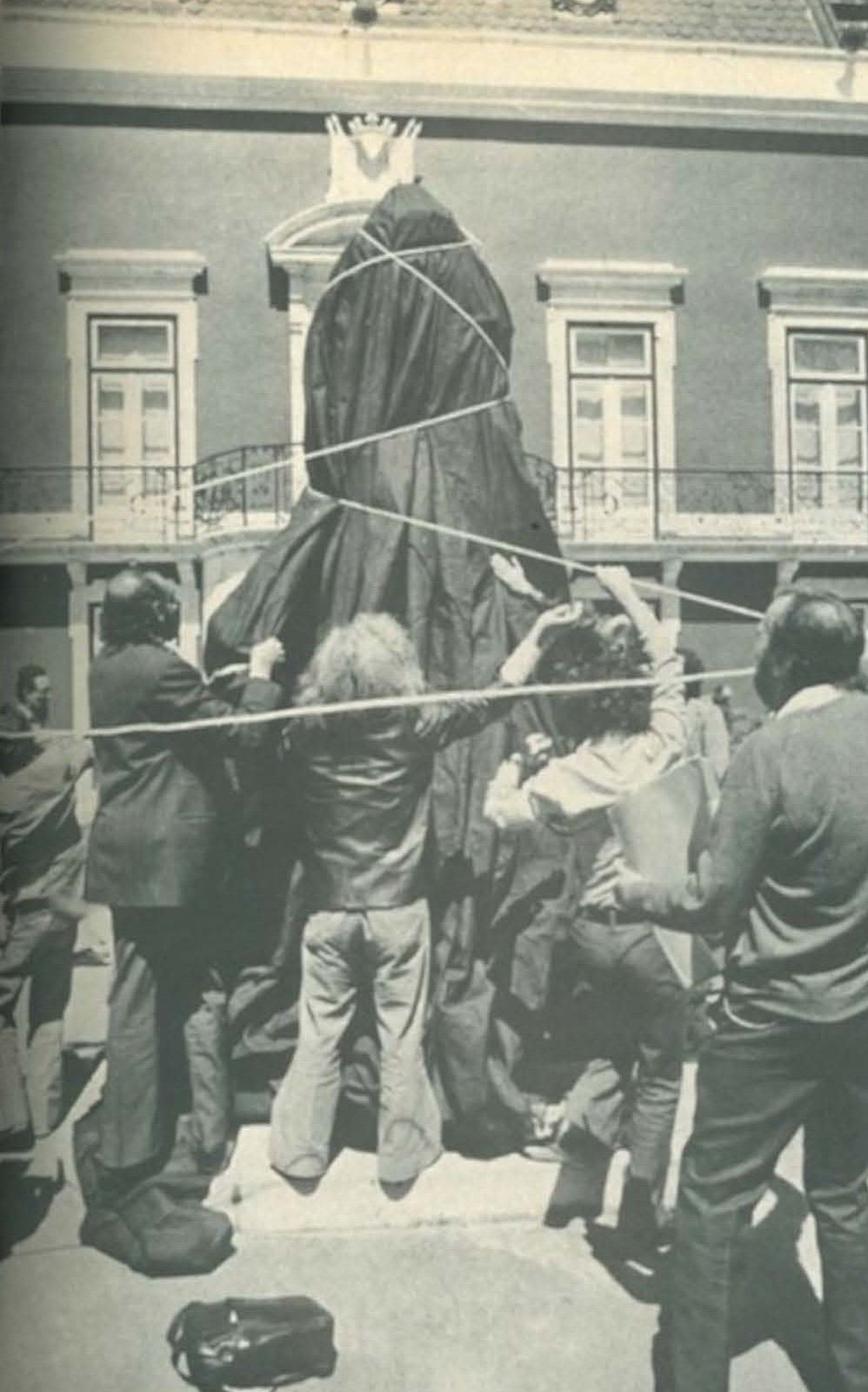

The MDAP was responsible for issuing several communiqués14, most of them disseminated in the media,as well as actions and initiatives that directly engaged the political power. The month it was founded, the MDAP sent the Minister of Justice a telegram (May17, 1974) requesting formal prosecution of those responsible for the murder of José Dias Coelho15 and organized a tribute to this same artist on the anniver- sary of his birth.16 Their first performative action took place on May 28, 1974, when some artists went to the Palácio Foz (Lisbon) and covered the statue of António de Oliveira Salazar17 and the bust of António Ferro18 with black cloths, placing a banner with MDAP's inscription. A communiqué was distributed during this action19, which stated that the initiative was “at the same time a symbolic destruction and an act of artistic creation in a gesture of revolutionary freedom. Fascist art harms your vision" (Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos, 1974a, p. 41). This action sought to resume the demand for the elimina- tion of symbols, policies, and structures associated with fascism. The DAP declared that it did not defend the destruction of works of art, choosing therefore to cover the statues, but considered that they should be “stored”, and should not “remain present in a public building responsible for the democratization of the country" (Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos, 1974a, p. 41).

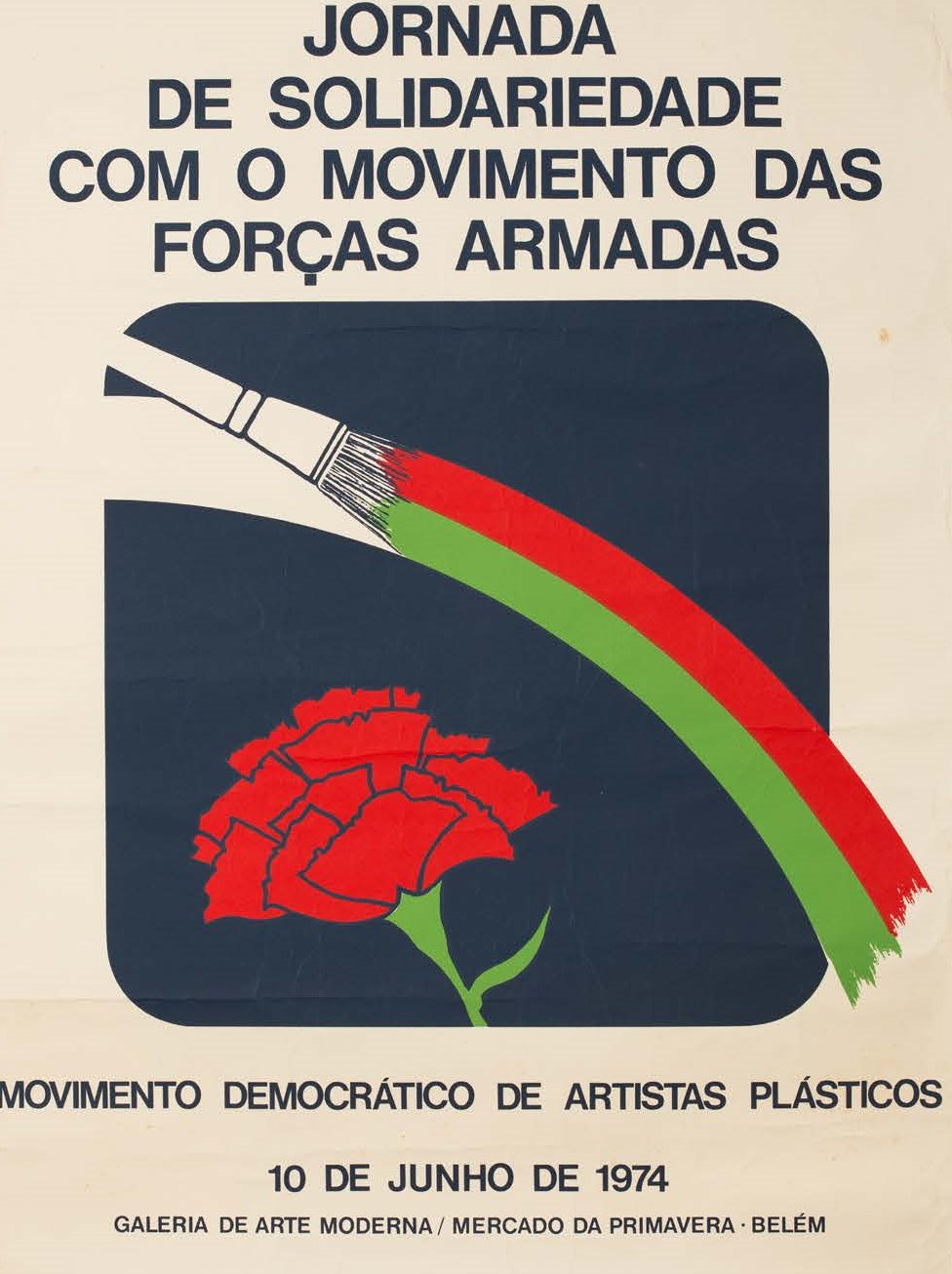

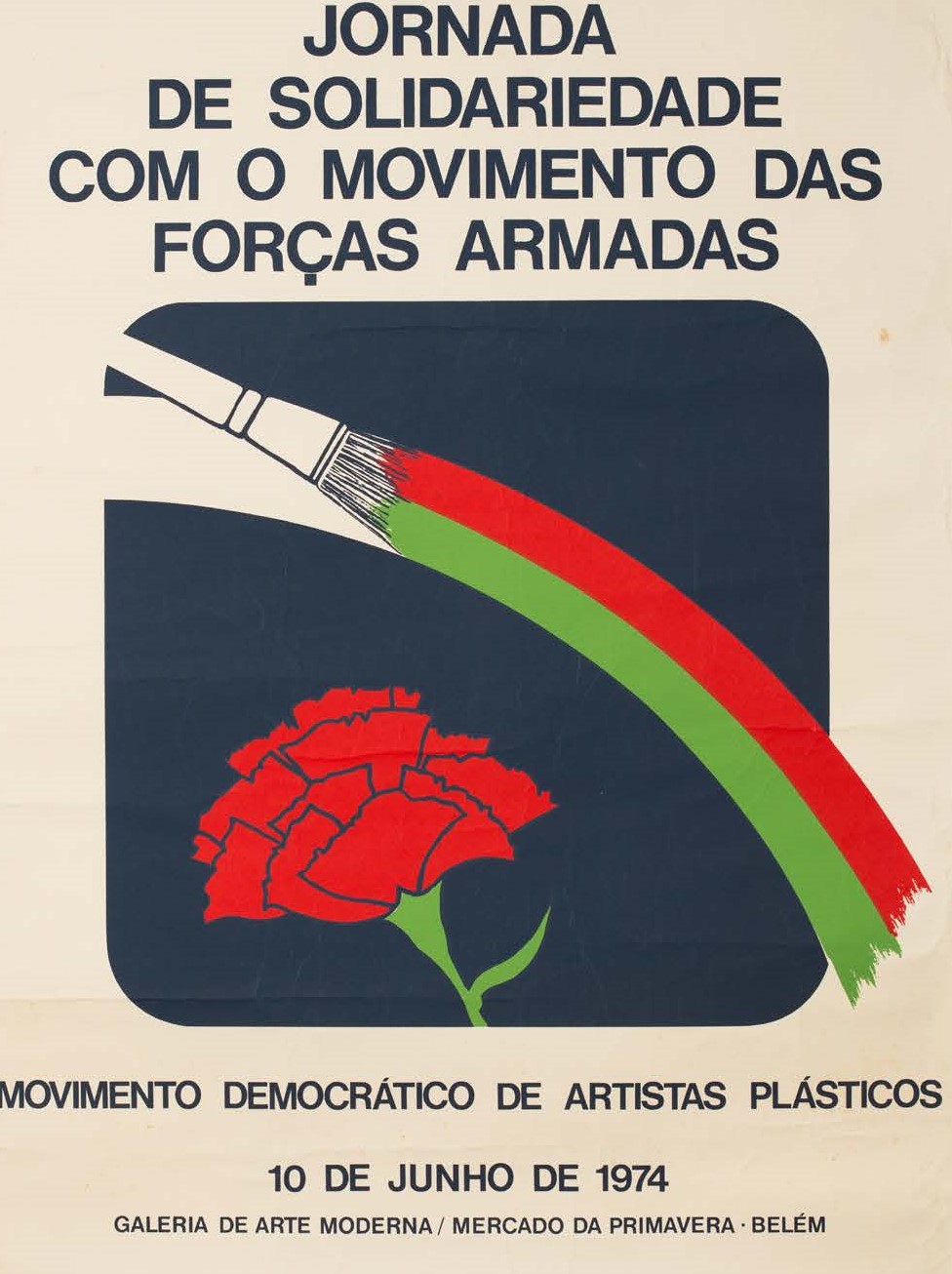

Figure 3 . MDAP, Day of Sol3idarity with MFA posterSource: Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos (1974b)

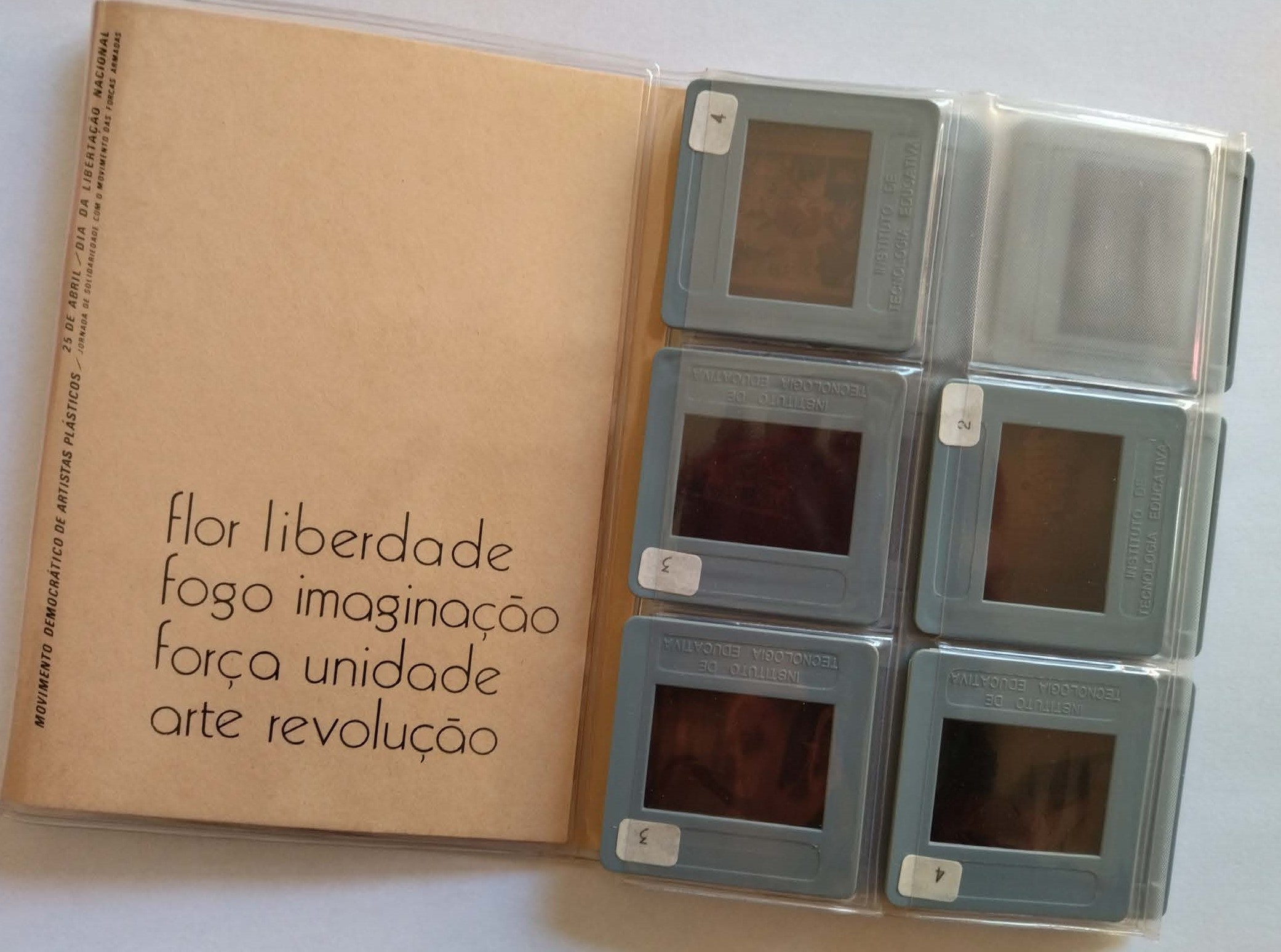

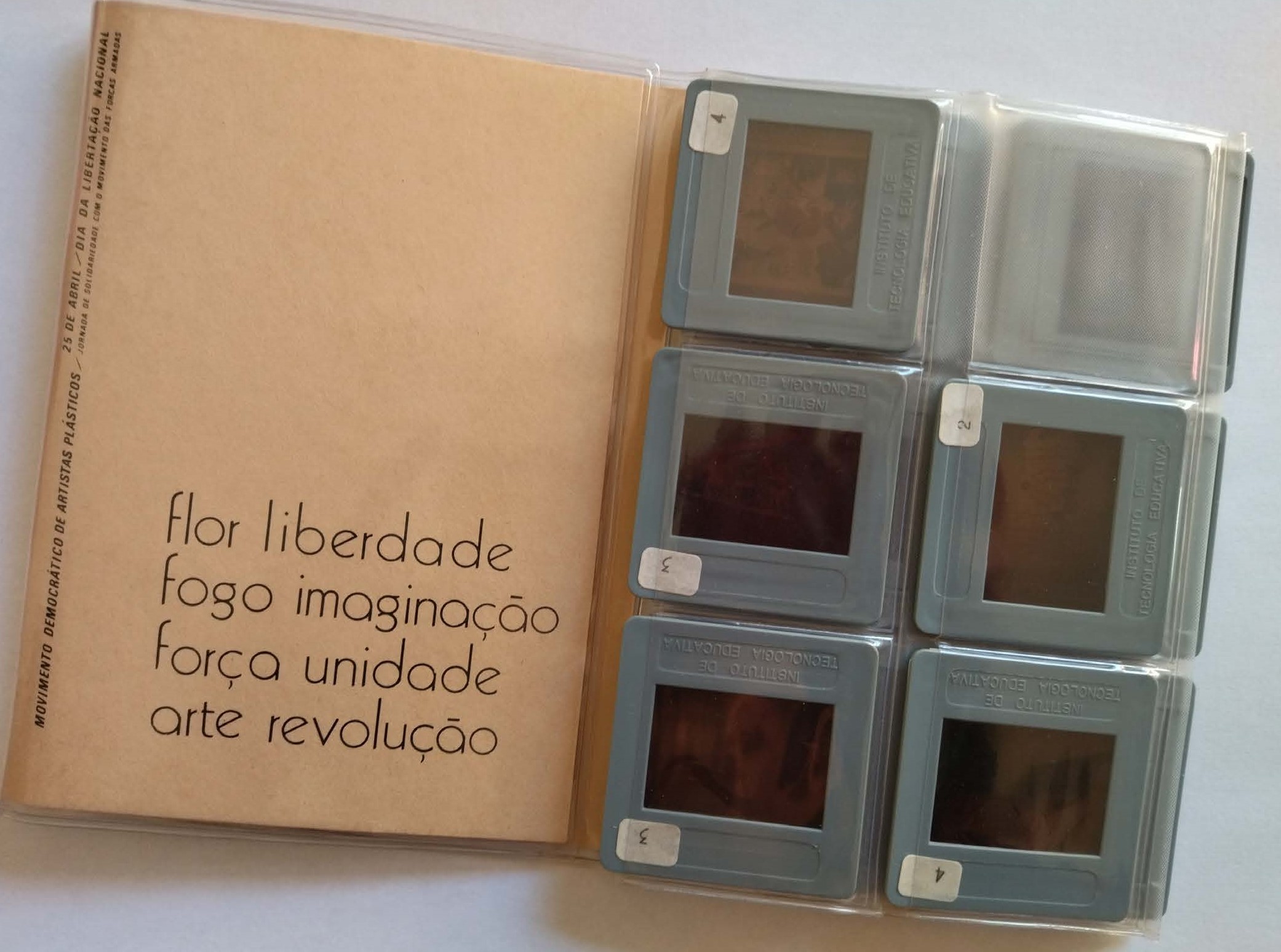

Figure 4. MDAP, slide album of the Day of Solidarity with MFA Fundo ATD / Colecção Luandino Vieira / "http://www.tchi- weka.org/iconografia/7002000036"www.tchiweka.org/ iconografia/7002000036

The MDAP also engaged in political dialogue with the MFA, which began during the Day of Solidarity with the MFA, on June 10, 1974 (Correia and Gomes, 1984). Events that day were held in the Mercado do Povo, in Lisbon, and included various interventions in the areas of music, visual arts20, and theater21. In the country's history, this was the first initiative in conditions of freedom where “a set of actions [...] proposed a new relationship between art and the public” (Almeida, 2009, p. 113). This relationship occurred not only in the construction of "towers of painted bricks" and of an "extensive wall, scribbled, scratched and written upon by a compact crowd that filled the Galeria de Belem

In addition to the contact with the popular masses, during this event, collaboration between artists assu- med the political purpose that the MDAP had enun- ciated after the revolution. That day marked a "new way of using urban space, not only for partisan values, but also recreational values" (Gonçalves, 2004, p. 110) and can be understood as a result of the "rich creative situation" and as the first example of "experimentation in live-democracy” (Caeiro, 2014, p. 116-117).

Following this initiative, the MDAP expressed "its position of unity, understanding and active participa- tion with the MFA in the country's process of cultural democratization” (Correia and Gomes 1984, p. 145). The political relation between the two structures would hereafter be quite close. Rodrigo de Freitas,João Moniz Pereira, and Marcelino Vespeira, members of the MDAP, became members of some MFA orga- nizations, such as the Comissão Coordenadora de Animação Cultural (Cultural Animation Coordinating Committee) and CODICE (Correia and Gomes, 1984). In addition, as part of Campanhas de Dinamização Cultural e Acção Cívica (CDCAC, Cultural Promotion and Civic Action Campaigns)22, which oversaw the visual arts, several graphic materials were produced, and there were cultural and artistic initiatives23, with the collaboration of members of the movement, such as João Abel Manta, Marcelino Vespeira, Rogério Ribeiro, Lima Carvalho, among others.

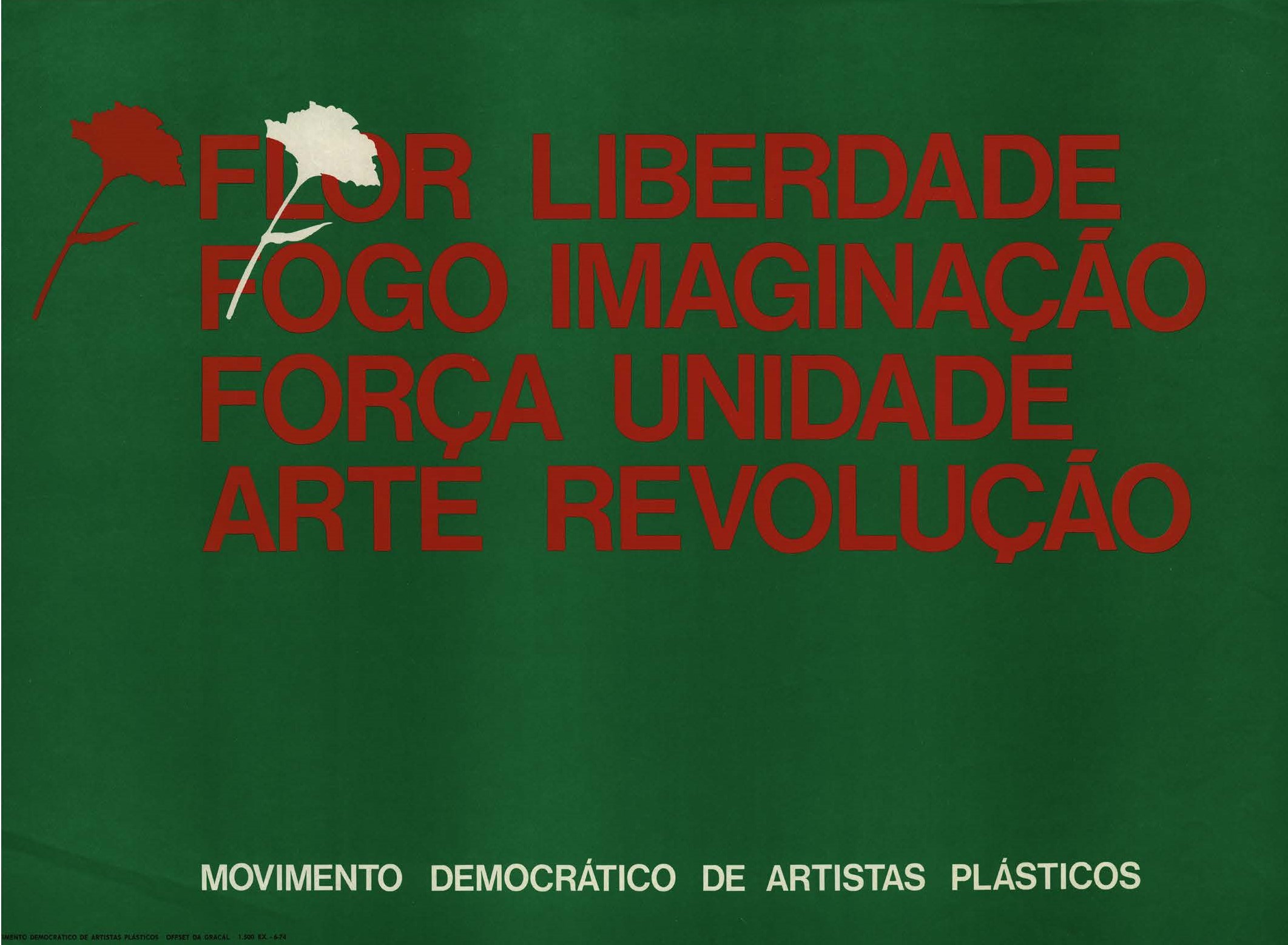

Figure 5. MDAP, slide album of the Day of Solidarity with MFA. Source: Author

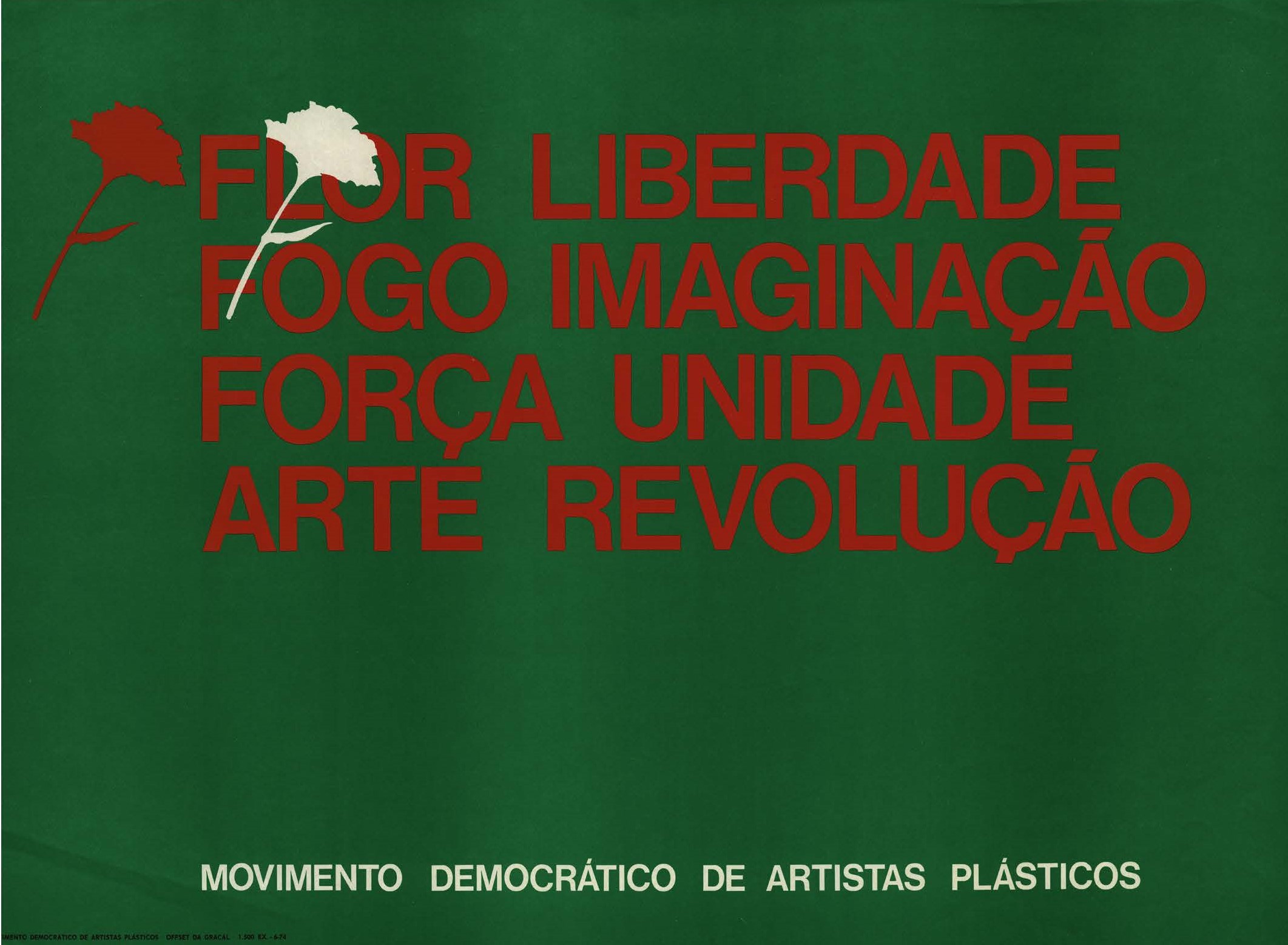

Figure 6. MDAP poster, 49 x 70 cm. Source: BNP - Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal: https://purl.pt/7558

In an interview with Sónia Vespeira de Almeida, Marcelino Vespeira enthusiastically recalled "the relationship with the MFA military" and the fact that he accepted "their proposal of ‘cultural guerrilla'" (Almeida, 2009, p. 115).

The guerrilla strategy is identifiable in the MDAP’s adopted models of civic participation and inscription in the public sphere. Jürgen Habermas defines the public sphere as related to social life, as the place where public opinion and the public body are for- med (Habermas, Lennox, and Lennox, 1974).

The MDAP understood the importance of artists' effective democratic participation in Portugal's new social and political context, as it emerged from a dictatorship where the public sphere had been uninterruptedlyconstrained. Let us consider, for instance, their action during the construction of a monument in honor of General Humberto Delgado, in Cela Velha (Alcobaça). Having learned that sculptor Joaquim Correia had been directly commissioned to build the monument, the MDAP addressed a letter to the City Hall of Alcobaça requesting clarification about the process. José Guilherme Abreu maintains that this intervention introduced a fundamental change to how the official commission of monuments was processed. This came to represent the "formation of new mediations [...] based on the interaction of citizens" (Abreu, 2006,p. 594).

The author therefore considers that MDAP's interpellation was an example of "intervention, cooperation and consensus, negotiated around a jointly developed program, within the public sphere" (Abreu, 2017, p. 172). But this example is not unique, as all of MDAP's actions and initiatives sought to discuss ideas, processes, or events in the country'scultural, political, and social life, discussing them with the local and central government. This possibility of public sphere intervention prompted the MDAP to publicly take position in the media by sending state- ments and posters for publication. The same stimulus is found in the organization of the aforementioned Day of Solidarity with the MFA, or the Day of Solidarity with the Spanish Political Prisoner (January 1975, Lisbon) or the participation, together with political parties and trade unions24, in the organization of aDay of Support of the People of Chile (September 14, 1976, Figueira da Foz). One of the MDAP's posters captures their poetics in action in this regard quite well: on a green background, a red carnation emer- ges from its outline over the words "Flower Freedom, Fire Imagination, Strength Unity, Art Revolution". The carnation, symbol of the Portuguese revolution, is the graphic element that, together with the green back- ground, represents the country. The words, arranged in pairs, represent the path towards the democratiza- tion of culture and the arts.

Conclusion

The cultural guerrilla strategy has, in its genesis, an important symbolic character. It was allocated into the arts through the idea of resistance to the artistic system and, in some cases, simultaneously to the political and social system. In Portugal, after the revo- lution, this symbol of resistance was eventually transmuted, although it retained its characteristic vigor.The symbolism that emerged during the revolutionary process was that of civic participation. The aims of cultural and artistic actions resided in the construction of a new democratic structure. Therefore, the guerrilla strategy and its tactics were applied to these aims.

Nevertheless, the different positions adopted in this regard by socially committed artistic practices should be assessed. In the context of the Portuguese revo- lutionary process, where the possibility of buildinga new future was a tangible reality in the immediate future, several intellectuals –and, in this case, artists– chose civic participation, seeking to contribute to the ongoing discussion to define a cultural policy.Integrated within the centers of political decision, they penetrated the social-political sphere in a consequential way, with the purpose of becoming direct agents of the ongoing process. They became representatives of the professional class of artists, organizing themselves into collective structures, such as the MDAP, and undertook negotiation and dialogue as vehicles for social transformation.

After 1976, the lack of a solidly defined cultural policy and the state’s progressive divestment from its res- ponsibility regarding culture –the result of an ideo- logical reorientation and the greater protagonism of right-wing parties in the government– gave rise to growing discontentment and the progressive removal of artists from centers of political decision (Cruzeiro, 2021). There was also a decline in collectivism and guerrilla performativity in practical, symbolic, and discursive terms. Among the more active artists, disillusionment with political decisions was expressed as early as May 1976, on the occasion of the May Day celebrations, when a group of 61 artists, designers and art critics, signed a manifesto declaring their aim

to act [...] as a catalyst of the opinion, which we hold to be the majority's opinion, that one can wait no longer for the responsible departments to define their policies [...] nor is it acceptable that any policy for the sector be elaboratedwithout our active participation. (Manifesto de Artistas no 1.º de Maio, 1976, p. 14)

The same manifesto, as published in the press, states: "we risk losing the revolution in the field of culture, as in many others. [...] The people have the right to know that artists are not dead or inactive, but continue to fight for better working and creative conditions" (Manifesto de Artistas no 1.º de Maio, 1976, p. 14).

The importance of the Portuguese revolution within the global context in that historic period should be noted, for it represented an exception in Europeat the time, as indicated by Eric Hobsbawm (1996). During the Cold War, the Portuguese revolution was a striking event, given the defeat of a fascist dictator- ship and subsequent demise of the most long-lasting case of European imperialism, following the indepen- dence of its African colonies.

Culture played an important political role in the antiimperialist and anticapitalist struggle. The begin- ning of the article mentioned this importance, in conjunction with the visibility acquired by the gue- rrilla strategy and its symbolic adoption in the arts.During the Portuguese revolutionary process, the broad social support base of the Partido ComunistaPortuguês (PCP, Portuguese Communist Party) and the Partido Socialista (PS, Socialist Party) amplified the Portuguese victory worldwide in the context of the anti-imperialist struggle. While this social basis was also found in other European countries, such as France and Italy, during the Portuguese revolu- tion, even if only for a brief historical moment, there was hope of strengthening socialist and communist influence in the European and world political lands- cape. For the history of socially committed artistic practices, the Portuguese case is an important instance of how it was possible to articulate citizenparticipation and direct action with effective political intervention.

Uma casa para a Arte Moderna (1975, April, 15). Sempre Fixe. Manifesto de Artistas no 1.º de Maio (1976, May, 4). Diário de Lisboa, 14.

Uma casa para a Arte Moderna (1975, April, 15). Sempre Fixe. Manifesto de Artistas no 1.º de Maio (1976, May, 4). Diário de Lisboa, 14

Manifesto de Artistas no 1.º de Maio (1976, May, 4). Diário de Lisboa, 14.

Abreu, J. G. R. P. (2017). Public art as a means of social interaction: From civic participation to community involvement. In UNESCO (Eds.), Actes du Colloque International "Quel destin pour l’Art Public"[Paris, France], 19-20 Mai 2011 (pp.159-174). Paris, France: Centre du Patrimoine Mondial de L’UNESCO.

Almeida, S. V. de (2009). Camponeses, Cultura e Revolução: Campanhas de Dinamização Cultural e Acção Cívica do M.F.A. (1974-1975). Lisbon, Portugal: Edições Colibri and IELT – Instituto de Estudos de Literatura Tradicional.

Arquivos RTP (1974). Reunião de individualidades com a Junta de Salvação Nacional. https://arquivos.rtp.pt/conteudos/reuniao-de-individualidades-com-a-junta-de-salvacao-nacional/

Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (1974). Flor liberdade, fogo imaginação, força unidade, arte revolução / Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos. https://purl.pt/7558

Caeiro, M. (2014) Arte na Cidade: História Contemporânea. Lisbon, Portugal: Círculo de Leitores.

Celant, G. (2020). In memory of Germano Celant: Arte povera. Notes on a guerrilla war. https://flash---art.com/article/germano-celant-arte-povera-notes-on-a-guerrilla-war/

Correia, R., and Gomes, V. (1984) Livro Branco da 5ª Divisão 1974-75. Brasilia, Brazil: Ler Editora.

Couceiro, G. (2004) Artes e Revolução 1974-1979. Lisbon, Portugal: Livros Horizonte.

Cruzeiro, C. P. (2021). Art With Revolution! Political Mobilization in Artistic Practices Between 1974 and 1977 in Portugal. On the W@terfront, 63(10), 3-35. https://doi.org/10.1344/waterfront2021.63.10.01

Dias, F. R. (2014). Dois momentos históricos da performance no Chiado: as acções futuristas e o Grupo Acre. In J. Quaresma (Coord.), O Chiado da dramaturgia e da performance (pp. 40-71). FBA-CIEBA.

Freitas, A. (2007). CONTRA-ARTE: vanguarda, conceitualismo e arte de guerrilha 1969-1973 [Unpublished doctoral thesis, Universidade Federal do Paraná].

Galimberti, J. (2017). Individuals against Individualism. Art Collectives in Western Europe (1956-1969). Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press.

Gonçalves, E. (1974). Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos: A intervenção necessária. Flama, 1378, 38-42.

Gonçalves, R. M. (1980). Carta de Lisboa. Colóquio/Artes, 47, 64.

Gonçalves, R. M. (2004). Vontade de mudança: Cinco décadas de artes plásticas. Lisbon, Portugal: Editorial Caminho.

Habermas, J., Lennox, S., and Lennox, F. (1974). The public sphere: An encyclopaedia article. New German Critique, 3, 49-55. https://doi.org/10.2307/487737

Hobsbawm, E. (1996). A Era dos Extremos, História Breve do Século XX. Lisbon, Portugal: Editorial Presença.

Le Parc, J. (2014) Guerrilla Cultural. Julio Le Parc. http://julioleparc.org/guérilla-culturelle.html

Loff, M. (2006) Fim do Colonialismo, ruptura política e transformação social em Portugal nos anos setenta. In M. Loff and M. da C. M. Pereira (Eds.), Portugal: 30 anos de democracia (pp.153-194). Porto, Portugal: Editora da Universidade do Porto

Loff, M. (2008). O nosso século é fascista! O mundo visto por Salazar e Franco (1936-1945). Porto, Portugal: Campo das Letras.

López, P. B. (2015). Collectivization, participation and dissidence on the transatlantic axis during the Cold War: Cultural Guerrilla for destabilizing the balance of power in the 1960s. Culture & History Digital Journal, 4(1), e007. https://doi.org/10.3989/chdj.2015.007

Madeira, C. (2020). Arte da Performance, made in Portugal: uma aproximação à(s) história(s) da arte da performance portuguesa. Lisbon, Portugal: Livros ICNOVA.

Manuel pires (2015, November 25). PAINEL do 10JUNHO 74 [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7KlT8tsSZ2w

Morais, F. (1970). Contra a arte afluente. Documents of Latin American and Latino Art. https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/item/1110685#c=&m=&s=&cv=3&xywh=-1116%2C0%2C3930%2C2199

Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos (1974a). A Arte fascista faz mal à vista. Flama, 1370, 40-41.

Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos (1974b). Cartaz do MDAP em Solidariedade com o MFA. https://www.tchiweka.org/iconografia/7002000036

Oliveira, L. de (2013). Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Serralves: Os Antecedentes, 1974-Lisbon, Portugal: Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda.

Pignatari, D. (2004). Teoria da guerrilha artística. In D. Pignatari (Ed.), Contracomunicação (pp. 167-176). São Paulo, Brazil: Ateliê Editorial.

Pimenta, F. T. (2022). A ideologia do Estado Novo, a guerra colonial e a descolonização em África. In J. P. Avelãs Nunes and A. Freire (Ed.), Historiografias Portuguesa e Brasileira no século XX Olhares cruzados (pp. 183-201). Coimbra, Portugal: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Rosas, F. (1998). O Estado-Novo (1926-1974). In J. Mattoso (Ed.), História de Portugal. Lisbon, Portugal: Editorial Estampa.

Sousa, E. de (1975, January 23). O grupo ACRE e a apropriação, Vida Mundial, 41-42.

Torgal, L. R. (2009). Estados Novos, Estado Novo. Ensaios de História Política e Cultural. Coimbra, Portugal: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Wood, P. (2002). Conceptual Art: Movements in modern art. London, UK: Tate Publishing.

Notas

dictatorship, as a way of highlighting the ideological character of the regime. For a more in-depth look at the issue, see, among others: Loff (2008), Rosas, (1998), Torgal (2009).

MDAP disassociates itself from an initiative promoted by some members of the SNBA regarding the occupation of the Sociedade Cooperativa de Gravadores Portugueses (Cooperative Society of Portuguese Engravers), expressing their solidarity with this society (Gonçalves, 1974).

Recibido: 15 de diciembre de 2021; Aceptado: 4 de abril de 2022

Resumen

El 25 de abril de 1974, la revolución portuguesa acabó con una dictadura fascista que había durado 48 años. En el contexto político y social global de la Guerra Fría, la nueva situación del país se entendió como una victoria para el movimiento antimperialista y anticapitalista, particularmente en Europa. Este artículo analiza las prácticas artísticas llevadas a cabo durante el proceso de revolución portugués (1974-1976), específicamente la adopción simbólica de una estrategia de guerrilla en las artes: una guerrilla cultural.

En primer lugar, el artículo introduce el tema y se pregunta cómo una guerrilla cultural era relevante en el contexto artístico nacional durante el periodo estudiado, asumiendo el colectivismo como la característica básica y esencial de la estrategia. A esto le sigue una discusión sobre las formas de autoorganización y acción directa lideradas por los colectivos.

En esta línea, la estrategia de una guerrilla cultural se utilizó en articulación con los centros de decisión política como medio para proyectar las voces de los artistas en la esfera político-social. La conclusión subraya las circunstancias extraordinarias de Portugal en el contexto político y social de la Guerra Fría y la relevancia de las prácticas artísticas durante el periodo en aras de un entendimiento internacional de la temática.

Palabras clave

revolución portuguesa, prácticas artísticas socialmente comprometidas, guerrilla cultural, Guerra Fría.Abstract

The Portuguese revolution, on April 25th, 1974, ended a fascist dictatorship that had lasted for forty-eight years. In the political and social global context of the Cold War, the country's new situation was understood as a victory for the anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist movement, particularly in Europe. This article will analyse the artistic practices during the Portuguese revolutionary process (1974-1976), particularly the symbolic adoption of a guerrilla strategy within the arts: a cultural guerrilla. First, the article introduces the topic and ask how acultural guerrilla was relevant within the national artistic context during the period in focus, assuming collectivism as the strategy's basic and essential characteristic.

This is followed by a discussion of forms of self-organization and direct action led by collectives. In this regard, the strategy of cultural guerrilla was used in articulation with the centres of political decision, as a means of projecting the voices of artists into the political-social sphere. The conclusionunderlines the extraordinary context of Portugal in the political and social context of the Cold War and the relevance of artistic practices in this period towards international understanding of the topic.

Keywords

Portuguese revolution, socially committed artist practices, cultural guerrilla, Cold War.Résumé

Le 25 avril 1974, la révolution portugaise a mis fin à une dictature fasciste qui avait duré 48 ans. Dans le contexte politique et social mondial de la guerre froide, la nouvelle situation du pays était comprise comme une victoire du mouvement anti-impérialiste et anticapitaliste, en particulier en Europe. Cet article analyse les pratiques artistiques menées pendant leprocessus de la révolution portugaise (1974-1976), en particulier l'adoption symbolique d'une stratégie de guérilla dans les arts : une guérilla culturelle. En premier lieu, l'article introduit le sujet et demande comment une guérilla culturelle était pertinente dans le contexte artistique national au cours de la période étudiée, en assumant le collectivisme comme caractéristique fondamentale et essentielle de la stratégie. Ceci est suivi d'une discussion sur les formes d'auto-organisation et d'action directe dirigées par des collectifs. Dans cette ligne, la stratégie d'une guérilla culturelle a été utilisée en articulation avec les centres de décision politique comme moyen de projeter la voix des artistes dans la sphère politico-sociale. La conclusion souligne les circonstances extraordinaires du Portugal dans le contexte politique et socialde la guerre froide et la pertinence des pratiques artistiques au cours de la période pour une compréhension internationale du sujet.

Mots clés

Révolution portugaise, pratiques artistiques socialement engagées, guérilla culturelle, Guerre froide.Resumo

Em 25 de Abril de 1974, a revolução portuguesa acabou com uma ditadura fascista que havia durado 48 anos. No contexto político e social global da Guerra Fria, a nova situação no país se entendeu como uma vitória para o movimento anti-imperialista e anticapitalista, particularmente na Europa. Este artigo analisa as práticas artísticas realizadas durante o processo de revolução portuguesa (1974-1976), especificamente a adoção simbólica de uma estratégia de guerrilha nas artes: uma guerrilha cultural. Em primeiro lugar, o artigointroduz o tema e se pergunta como uma guerrilha cultural foi relevante no contexto artístico nacional durante o período estudado, assumindo o coletivismo como a característicabásica e essencial da estratégia.

A isto segue-se uma discussão sobre as formas de auto- organização e de ação direta liderada por coletivos. Nesta linha, a estratégia de uma guerrilha cultural foi utilizada em articulação com os centros de decisão política como meio para projetar as vozes dos artistas na esfera sócio-política. A conclusão sublinha as circunstâncias extraordinárias de Portugal no contexto político e social da Guerra Fria e a relevância das práticas artísticas durante o período para um entendimento internacional da temática.

Palavras-chave

Revolução portuguesa, práticas artísticas socialmente comprometidas, guerra cultural de guerrilha, Guerra Fria.Introduction

During the 1950s and 1970s, artistic practices in various countries around the world adoptedmethods, procedures, and forms of action associa- ted with the sphere of political struggle. Avant-garde movements had already tested this approach, but, during this period, there was a radicalization ofthis association, with the adoption of the specific mechanisms of direct political action. This association introduced the term guerrilla into the arts lexicon,in some cases interwoven with the development of conceptualism in the arts (Wood, 2002), in others with the social and political reality. This term, like vanguard, has connotations with warfare, even though, unlike the latter, it assumes a disassociation from a coun- try's military organization. Guerrilla warfare is usually carried out in opposition to the established power, with few human, financial and technical resources, which implies combat tactics such as sabotage, an underground organization, or proximity to local populations, gaining their support, protection, and trust. The intention is to distract, tire, disorient or demobilize the enemy. Given the scarcity of resour- ces, this implies imagination and creativity.

After World War II, the guerrilla strategy was com- mon knowledge in various regions of the world. In the 1950s and 1960s, several movements used this strategy in countries as diverse as Malaysia, Kenya, Cyprus, Spain, Vietnam, Cuba, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Guatemala, Argentina, Brazil, Nicaragua, Angola, Guinea, and Mozambique. Among them, the Viet Cong or National Liberation Front for South Vietnam (NLFSV) and the guerrilla movement that led the Cuban Revolution gained great global renown. As mentioned by Paula Barreiro López, these guerrilla movements, in association with the anti-imperialist struggle,

[...] had shown that tactics such as sabotage, ambushes or raids could have a decisive impact on fighting traditionally organized, larger, and militarily superior troops –and that they were quite effective for confronting the US hegemony and destabilizing the balance of power during the Cold War. (2015, p. 2)

In fact, during this period, the Cold War dominated the international political scene, with the US and the USSR representing polar opposite worldviews. While the imperialist worldview was dominant in Europe–with the exception of some territories such as Germany, where the USSR had partial influence, and Austria, which remained neutral (Hobsbawm, 1996)– this dominance was less clear outside of Europe, for example in Latin America. There, the struggle for the geo-strategic domination of the imperialist worldview led to the emergence of various fascist regimes and military coups, some with the clear support of the US, as is the case of Chile.

Although, in the 1970s, some revolutions positioned themselves ideologically against imperialist rule1, the political imaginary linked to the anti-imperialist struggle remained strongly associated with guerrilla warfare (Hobsbawm, 1996), even in countries whereit did not exist. Noteworthy examples include the stu- dent movements of May 68, in France (1968) and Italy (1969) which, inspired by this imaginary, adopted the tactics of direct action and urban guerrilla warfare.

The migration of the guerrilla strategy to the arts is partially justified by this political-social context. In various regions of the world, artists, critics, art histo- rians, and other intellectuals were mobilized to act politically. This action was characterized to a large extent by proposals of resistance and direct action within the artistic system (Freitas, 2007; López, 2015), such as those developed in the written texts of Décio Pignatari, Germano Celant, or Júlio Le Parc among others, which called for the constitution of a cultural guerrilla. These writings can be associated with the period's artistic avant-garde movements, but they are addressed to their peers, in the tone of a manifesto, using a language and political structure that defends direct action.

In 1967, Décio Pignatari wrote in Teoria da Guerrilha Artística that "nothing is more like a guerrilla than the self-conscious artistic avant-garde", which "today stands against the system" (2004, p. 169). During that same year, Germano Celant published the manifesto Arte Povera. Appunti per una guerriglia in the maga- zine Flash Art, which stated that "society presumes to make pre-packaged human beings, ready for consumption. Anyone can propose reform, criticize, violate, and demystify, but always with the obligation to remain within the system. [...] To exist from outside the system amounts to revolution" (2020). Therefore, Celant argued that "no longer among the ranks of the exploited, the artist becomes a guerrilla fighter, capable of choosing his places of battle and with theadvantages conferred by mobility, surprising and stri- king, rather than the other way around" (2020).In 1968, influenced by the political stances he had observed in South America, Júlio Le Parc published Guérilla Culturelle, where he stated that it was neces- sary "to reveal the existing contradictions within each medium. Develop an action so the same people pro- duce change" (2014). Le Parc considered that

in intellectual and artistic production there are two well-di- fferentiated attitudes: all those that –voluntarily or not– help maintain the structure of existing relations, preserve the cha- racteristics of the current situation; those initiatives, deliberate or not, scattered a little everywhere, that try to undermine relationships, destroy the mental schemes and behaviours the minority relies on to dominate. These are the initiatives that should be developed and organized. (2014)

To this end, he said it was necessary "to organize a kind of cultural guerrilla against the current state of affairs, to highlight contradictions, to create situations where people rediscover their ability to produce changes" (Le Parc, 2014).

The three texts evoked here, published in distinct contexts, namely Brazil, Italy, and France, focus on the artist's political action and not on aesthetic action.

They question the artist's responsibility as a citizen, an agent of political intervention within his/her social group and in the environment where he/she works, thereby participating directly in the sought-after social transformation. Political intervention with a socio-cultural fabric, as suggested in the three exam- ples, should be based on guerrilla tactics against the cultural system, an integral part of the broader macro- cosm of society.While the links to guerrilla strategy in the artistic context are evident at the symbolic and discursive levels, its conversion into practice is more complex. Nevertheless, collective action, citizen participation and direct communication in the public space –such as the distribution of communiqués and pamphlets, agit-prop, murals and street performances– can be understood as guerrilla tactics within the arts.

In Portugal, the more direct and profound knowledge of guerrilla strategy came from the Portuguese experience in the colonial war. The colonialist and impe- rialist policy of the fascist dictatorship 2 was a central factor of the regime. Since its formation, it sought to "safeguard the Portuguese colonial heritage from foreign ambitions and convert it into a great Empire" (Pimenta, 2022, p. 188). Thus, since 1961, it fiercely fought the liberation movements of the colonized African countries, such as Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea. These movements 3 used guerrilla tacticsin their fight against Portuguese troops, who were largely soldiers forced by the Portuguese govern- ment to fight in the colonies. The colonial war was one of the regime's main factors of attrition and, at the same time, one of the main promoters of the captains’ movement that led the revolution in the homeland.The Portuguese revolution of April 25, 1974, was carried out by the Movimento das Forças Armadas (MFA, Armed Forces Movement) with the immediate support of the popular democratic movement.

Until the inauguration of the First Constitutional Government, following the first legislative elections on April 25, 1976, Portugal was governed by six Provisional Governments 4 , which had to implement the MFA's Program. The revolutionary process between 1974 and 1976 was complex and included periods of great intensity (Loff, 2006). However, it can be characterized by the desire to install an anti-ca- pitalist democracy towards the creation of a socia- list society, a desire that remains expressed to this day in the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic (Cruzeiro, 2021).

The guerrilla imaginary that assaulted the European intellectual circles within the anti-imperialist struggle, which was circulated in Portugal before the revolution 5 , was reinforced by the colonial war’s proximity. Nevertheless, it gained greater expression and visibility during the revolutionary process. In contrast to what happened in other European countries, the cultural guerrilla was adopted in Portugal between 1974 and 1976, largely as a strategy to support the revolutionary process. Collective organization, participation, and action in the political-social sphere, characteristics of the conceptual configu- ration of the cultural guerrilla (López, 2015), were adopted by several Portuguese artists and collectives that, in this way, integrated the country's panorama of artistic practices during this period.

Collective action and guerrilla strategy during the Portuguese revolutionary process (1974-1976)

Between the 1950s and 1970s, in the context of artistic practices, collectivism was closely related, on the one hand, to the fight against individualistic, existen- tialist, and autonomous conceptions of modern art; and, on the other hand, to the context of the Cold War and its ideological polarization between theUS and the USSR (Galimberti, 2017). In this context, "individual as well as collective, to a large extent, became associated with those two political, inte- llectual and cultural systems and naturally opposed" (López, 2015, p. 3). Examples include collectives such as Spur, N (Padua, Italy), T (Milan, Italy), Equipo 57 (France and Spain), Equipo Crónica (Valencia, Spain), Equipo Córdoba (Cordoba, Spain), Internationale Situationniste (France), GRAV (France), and Komunne I (East Germany), whose performance sought effectsin the cultural arena, but simultaneously in the political and social ones.

In Portugal, the fascist dictatorial regime did not allow the dynamic constitution of artistic collecti- ves. However, the artistic field legitimized by the fascist State coexisted with a marginal artistic field, from which some groups arose, such as the Grupo Surrealista de Lisboa (Surrealist Group of Lisbon, 1947) –which, after some tensions, led to the forma- tion of Os Surrealistas (The Surrealists)–, the 21G7 group (1960), the group associated with the Poesia Experimental (Experimental Poetry) magazine and PO.EX (1963), or the Os Quatro Vintes (Four Twenties, 1968). Although these collectives had different moti- vations, and not all of them were focused on political resistance to the regime, several intellectuals and artists were part of this struggle, either individuallyor by integrating anti-fascist movements, such as the Movimento de Unidade Democrática (Movement for Democratic Unity, MUD). Nevertheless, freedom of association was severely limited, and the formation of artistic collectives, particularly socially commit- ted groups, was therefore residual, which is why the collectivist movement in Portugal only arose in all its vigor with the Portuguese revolution.

The period between 1974 and 1976 was fertile for collectivism. Collective organization was used both for creative purposes and for political and social issues. Examples within the wider field of artistic and cultural expression include, among others,the Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos (Democratic Movement of Visual Artists, MDAP, 1974), the Frente de Acção Popular de Artistas Plásticos (Popular Action Front of Visual Artists, FAPAP, 1974), the ACRE group (1974), the Comissão para uma Cultura Dinâmica (Commission for a Dynamic Culture, 1974), the Movimento Unitário dos Trabalhadores Intelectuais para a Defesa da Revolução (United Movement of Intellectual Workers for the Defense of the Revolution, MUTI, 1975), the Puzzle group (1976), the Colectivo 5+1 (Collective 5+1, 1976), the Cores/ GICAP (Colors/GICAP, 1976), and the IF – Ideia e Forma group (IF – Idea and Form, 1976). During the same period, several cultural and recreational associa- tions arose –as well as cooperatives– which had seve- ral artists in their governing bodies (Cruzeiro, 2021).

A strategy of cultural guerrilla, as a form of collective action, was promoted by the desire of artists and intellectuals for self-organization and direct action. That action was characterized by the use of imme- diate and impactful tactics to intervene in the public space and the public sphere. This action was foste- red by the revolutionary atmosphere, "which bends predictability in order to intensify the moment's tense experience" and produces "an a-legal period that allows another adventure in actions" (Dias, 2014, p.42). The strategy was used immediately after the revo- lution, while its presence is residual among collecti- ves formed after 1976.

Figure 1. ACRE group, intervention in Torre dos Clérigos (Porto) Source: Lima Carvalho collection

The guerrilla strategy's corresponding performati- vity was diverse and sought a wide range of effects. The notion of performativity comprises the beha- vior adopted in the various spheres of life and their different circumstances. In the country's developing political-social framework, paving new avenues of possibility, this behavior reflected artists’ desire to act in the present, thus contributing to producing and experiencing change. This experience of the immediate and urgent led to a performativity based on the body's direct involvement in action and the lived experience. In most cases, in accordancewith the project of society being defended, the motive for action was the collective –and not the individual– project.

Figure 2. ACRE group, occupation of the Palácio Mendonça (Lisbon) Source: Uma casa para a Arte Moderna (1975, April, 15)

The experience of the revolutionary moment legi- timized a radical performativity, for example, in the actions of the ACRE group (1974-1977), formed bythe artists Lima Carvalho, Clara Menéres, and Alfredo Queiróz Ribeiro. 6 The group's artistic practice was characterized by performances of political interven- tion, the publication of communiqués and documents attributing a fictitious legal authority to the group, and interventions in the public space and by evoking this same space. The practice of cultural guerrilla tactics pervaded most of the group's activity, particularlythe clandestine nature of their interventions. The first, held in Rua do Carmo (Lisbon), inaugurated the"urban and guerrilla dimension" (Dias, 2014, p. 65) that the group would later intensify. Large yellow and pink circles were painted on this street's sidewalk during the night, "without permission from anyone" and illegally interrupting road traffic with a fake traffic sign made by Lima Carvalho. 7 Also clandestine was the intervention in Torre dos Clérigos (Porto), on October 25, 1974, which consisted of placing a 75-meter-long yellow plastic sleeve under the building. Lima Carvalho recalls that "for weeks, when going to Porto, I studied the movement around the Tower – the movement of the priest, the sexton, the tourists... – to know when we could attack, so as not to fail".8

Expressing the desire of artists and other intellectuals since the revolution to build a museum for contem- porary art9, the occupation of the Palácio Mendonça (Lisbon), uninhabited at the time, was one of ACRE’s most representative guerrilla actions. On April 18, 1975, Lima Carvalho and Clara Menéres, accompa- nied by other citizens, entered the palace and pla- ced some cloth banners, re-naming it the Museum of Modern Art (Uma casa para a Arte Moderna, 1975).The building's occupation lasted that afternoon, ending with the intervention of the Military Police and the arrest of ACRE members.

Frederico Morais astutely observed the intersection of procedural and conceptual artistic practices with the guerrilla strategy, stating that "if art has become enmeshed in the day-to-day, by denying the specific and the medium, it can also be confused with the protest movements" (Morais, 1970, p. 56). Thus, art is "a form of ambush" and the artist "a kind of guerrilla" whose task is to create "nebulous, unusual, indefi- nite situations" for the spectator (Morais, 1970, p.49).

ACRE's actions can thus be characterized in this art-life binomial that acts within the artistic system, even though actions take place in the street. The Portuguese critic and multidisciplinary artist Ernesto de Sousa considered that, with ACRE, there was "a convergence that [led] to unstoppable results: convergence with modernity, the avant-garde", insinuating that although the "project, the idea asan aesthetic object", was not new, it had not been understood by most Portuguese contemporary artists (Sousa, 1975, p. 41).

Ernesto de Sousa was referring to Portuguese per- formance art –so-called since the 1960s and1970s (Madeira, 2020)– that blossomed after the Portuguese revolution. The liberated bodily action, which it represents, was eventually stimulated by the coun- try's new liberated condition. Freedom manifested reflexively, and its performative attitude embodied in turn a political attitude that, in this regard, elected the symbolism of the cultural guerrilla as a form of privileged action without, however, seeking to interfere in the country's cultural policy in any permanent way.

The cultural guerrilla in dialogue: the MDAP in alliance with the political decision centres

During the Portuguese revolutionary process, there was a complex but intense process towards the democratization of art and culture in general. One of the main actions of some cultural institutions and artistic collectives involved discussing how to "inter-fere in cultural policy" as stated by art critic Rui Mário Gonçalves (1980, p. 64), seeking to contribute tothe definition of the country's cultural policy. In this regard, the guerrilla strategy went beyond a symbolic character in some cases, and assumed self-organi- zation as a way into the public sphere and political decision-making. The performativity adopted, inthis case, was not characterized by merely taking a position, but also by insertion into the political deci- sion-making centers. The attitude was mostly colla- borative (Cruzeiro, 2021) and focused, for the most part, on dialogue and negotiation with the political power that emerged after the revolution, namely the National Salvation Junta (JSN)10 and the Provisional Governments that were constituted before the first democratic elections.

The MDAP was, in this regard, the first organized group of artists to play a prominent role in the efforts towards the construction of a “more general plan of cultural democratization”, as mentioned by Eurico Gonçalves (1974, p. 38). This movement established a direct dialogue with governmental structures, acting on the level of organized politics, and carried out a series of actions in the public space that were funda- mental to this context, such as drafting communiqués with proposals for the cultural sector, promoting working groups and organizing collective artistic initiatives (Gonçalves, 1974).

Constituted by dozens of artists 11 , who were mem- bers of the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes (SNBA, National Society of Fine Arts) 12 , the MDAP was created

The MDAP's actions took place mainly in Lisbon, although its proposals had a national scope. The movement's first communiqué, issued on May 9, 1974, was a manifesto defending politicized cultural intervention. In it, the movement proposed a series of measures aimed at building a new cultural policy, as well as extinguishing any remnants of structures and activities associated with the fascist dictatorial regime, which includes abolishing the fascist struc- tures of public bodies dedicated to the Fine Arts13, firing its officials and terminating “all commissions that censor and control the integration of works of art in public space” (Gonçalves, 1974, p. 40). They proposed the "immediate cancellation of the current program of exhibits” and holding an exhibit on poli- tical repression in the arts, as well as compiling an inventory of the artistic heritage (Gonçalves, 1974, pp. 39-40). On the next day, representatives of the MDAP met with members of the JSN to discuss issues associated with the sector of fine arts. Following the meeting, one of the MDAP's representatives issueda statement on national television (RTP), arguing thatthe movement had