DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.100Publicado:

2008-01-01Número:

No 10 (2008)Sección:

Artículos de Investigación‘I said it!’ ‘I’m first!’: gender and language-learner identities

Palabras clave:

Inglés como lengua extranjera, AFPD, identidad de género, identidad de estudiantes de lenguas, educación preescolar (es).Palabras clave:

EFL, FPDA, gender identity, language-learner identity, preschool education (en).Descargas

Referencias

Baxter, J. 2003. Positioning gender in discourse. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan

Castañeda-Peña, H. 2007. Positioning masculinities and femininities in preschool EFL education. Unpublished PhD Dissertation. Goldsmiths, University of London.

Castañeda-Peña, H. 2008. `Interwoven and competing gendered discourses in a pre-school EFL lesson' in Harrington, K et al. (ed.) Gender and language research methodologies. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Cook-Gumperz, J. and A. Kyratzis. 2001. `Child discourse' in D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen and H. Hamilton. (ed.) The handbook of discourse analysis Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Hruska, B. 2004. `Constructing gender in an English dominant kindergarten: Implications for second language learners'. TESOL Quarterly 38/3: 459-485

Nakamura, K. 2001. `Gender and language in Japanese preschool children'. Research on Language and Social Interaction 34/1: 15-43

Norton, B. 2000. Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change. Essex, UK: Longman

Norton, B. and A. Pavlenko (eds.). 2004. Gender and English Language Learners. Alexandria, VA: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL)

Pavlenko, A., et al. 2001. Multilingualism, second language learning, and gender. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter

Sachs, J. 1987. `Preschool boys' and girls' language use in pretend play' in S. Philips and S. Steele. (eds.) Language, gender and sex in comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Sheldon, A. 1990. `Pickle fights: Gendered talk in preschool disputes'. Discourse Processes 13: 5-31

Sheldon, A. 1996. `You can be the baby brother, but you aren't born yet: Preschool girls' negotiation for power and access in pretend play'. Research on Language and Social Interaction 29/1: 57-80

Street, B. (ed.) 2001. Literacy and Development: Ethnographic Perspectives. London: Routledge

Walkerdine, V. 1998. Counting girls out: Girls and mathematics. London: RoutledgeFalmer

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J, 2009 vol:10 nro:1 pág:112-125

Research Articles

‘I said it!’ ‘I’m first!’: Gender and language-learner identities

Harold Andrés Castañeda Peña Ph.D.

Associate Teacher, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Colombia. e–mail: hcastan@javeriana.edu.co

Abstract

While there has been an upsurge of research studying the relationship of gender and second language learning in cross-cultural contexts, far less has been investigated about preschool children’s gender and learner identities in contexts where English is a foreign language. In this paper I describe how gendered discourses are at stake in the classroom and how these discourses are related to the learner identities of a group of Colombian preschoolers. I use a Feminist Poststructuralist Discourse Analysis (FPDA) approach to pin down moments in which the assertion of power is manifested in second language practices like ‘classroom races’ during literacy activities. This assertion of power positions participants differently. Findings suggest the need to understand how children negotiate subject positions discursively in language learning activities. I am suggesting the need to erode discourses of approval that marginalize girls and favour boys.

Key words: EFL, FPDA, gender identity, language-learner identity, preschool education

Resumen

Aunque hay un número importante de estudios investigativos en varios contextos culturales sobre la relación entre género y el aprendizaje de segundas lenguas, poco se conoce sobre las identidades de género y sobre las identidades de los estudiantes de lenguas en contextos de niños y niñas preescolares en los cuales se enseña el inglés como lengua extranjera. En este escrito describo cómo los discursos de género juegan un papel importante en el salón de clase y cómo estos discursos están relacionados con las identidades estudiantiles de un grupo de preescolares colombianos. Utilizo el enfoque del Análisis Feminista y Postestructuralista del Discurso (AFPD) para señalar los momentos precisos de prácticas de aprendizaje de segundas lenguas como las ‘competencias’ en las que se manifiesta la aserción de poder durante actividades de lecto-escritura. Los y las participantes de las interacciones se posicionan de manera diferente en las interacciones a través de esta aserción de poder. Se sugiere, a partir de los hallazgos, la necesidad de comprender mejor cómo las niñas y los niños negocian discursivamente los posicionamientos de sus subjetividades en las actividades de clase. Sugiero, asimismo, la necesidad de borrar discursos profesorales de aprobación que marginalizan a las niñas y favorecen a los niños.

Palabras clave: Inglés como lengua extranjera, AFPD, identidad de género, identidad de estudiantes de lenguas, educación preescolar

An introductory ‘memory’

One interaction I witnessed in my home country Colombia made a lasting impression on me. The scene takes place in a preschool classroom of the Goldmedal Kindergarten – not is real name. The EFL teacher finishes a series of activities in the form of a ‘classroom race’ between two groups. Then she moves into explaining a colouring activity on the textbook page where students are to practise saying ‘B’. This colouring activity was not part of the ‘competition’ set up by the teacher initially – at least to her eyes.

The reason why I still remember this scene is because when the teacher elicits the choral answer ‘baby’ while pointing to a baby illustrated on the page, which students are supposed to colour afterwards, six-year-old Aura’s voice is more audible compared to her fellow classmates’ voice. She claims in Spanish ‘I said it! I said it!’ What Aura meant was that she was the ‘first one’ to get the answer right by saying ‘Baby!’ Fine! A few milliseconds later she blurts out, also in Spanish, ‘So, we scored one point!’ Presumably what Aura argued was that because of her, being ‘good at English’ (my interpretation!), her group, made up of boys and girls, scored an extra point over the other group of classmates. The female teacher, visibly irritated because of Aura’s ‘disruption’, glared at her saying ‘No, no, no, no! We are working on this page now!’

Arguably, in this interaction, Aura was discursively ‘constructing her ‘self’’ not just as a girl who is learning English and who relies on her mother tongue to conduct that process, but possibly as a girl expressing a very ‘assertive femininity’ (also my interpretation!). This ‘double’ discursive self-construction of an ‘assertive girl’ and of a ‘good language learner’ appears to position Aura powerfully with respect to her classmates.

Positioning with regards to ‘power’ occurs in interactions because when we talk, we invoke particular ways of relating to and being in the world locating our ‘selves’. In Aura’s case, for example, her ‘gender’ and ‘language learner’ identity construction clashes, at that moment, with the ‘power’ the teacher holds institutionally. The language teacher appears to impose unconsciously on Aura an identity as a language learner and as a girl. This ‘transitory’ yet ‘traditional’ gender identity seems to be that one in which ‘girls’ are expected to be ‘quiet, silent and well-behaved’.

Aura reflexively positions herself in the interaction by chipping in with her ‘I said it!’ but she is interactionally positioned by the language teacher, who plays an institutional role, perhaps focusing Aura’s attention on the language activity: ‘No, no, no, no! We are working on this page now!’ This, then, is the main issue this article deals with: the discursive (re) construction of gender identity and language learning identity.

Gender identity and SLL identity

A contemporary research strand within second language learning (hereafter SLL) addresses issues of (re) construction of gender identity (Norton 2000, Pavlenko et al 2001, Norton and Pavlenko 2004). Most of this work takes place in contexts of adults, adolescents and primary school children.

Additionally, these studies offer a wealth of evidence about how gender is unfixed and about how second language learners cannot be idealized or conceived of as abstract entities. It seems however that relatively few studies have examined the relation between gender, SLL and pre-primary education.

Hruska (2004) leads the way in this sense with her study of gender construction in an English-dominant kindergarten in the USA. Her one-year ethnographic study indicates that a number of preschool children strive for access to use the target language (English). This is achieved through the construction of gendered-friendship networks in which some preschoolers are core members whilst others are marginalized. Therefore, relationships are based on ‘power’ which is negotiated through either conflict or cooperation. In Hruska’s research (Ibid: 471), it is maintained that ‘classroom ideologies, such as gender, can shape who has access to whom, which in turn can affect second language learners’ access to language and high status identities like friends, which provide yet more access to English use’.

Identities and discourses

High status identities are constructed drawing on discourses. Discourses comprise ways of understanding the world, talking about it and – especially but not limited to – ‘becoming and/or being’ within it. A simple way to figure this point out is to look at discourses in the classroom. For example, seeing girls as ‘well-behaved’ is a discourse teachers might draw on to construct learners’ identities and to position them discursively, as in Aura’s case.

In educational contexts, discourses seem to relate heavily to the concept of ‘power negotiation’ in the sense that there are indications of ‘approval’ in classroom interactions. These discourses are known as the ‘Teacher-Approval’ and the ‘Peer-Approval’.

The ‘Teacher-Approval’ discourse tends to emerge when a teacher privileges a student over another from an academic or disciplinary point of view (Baxter 2003). This discourse could be fundamental to understand how the preschool teacher perceives Aura’s verbal ‘disruption’ in the above-described episode.

There is also the ‘Peer-Approval’ discourse where classmates either reject or cooperate with each other. This discourse is also key to understand how, for example, preschoolers construct friendship and solidarity ties by taking up powerful positions or by being given less powerful positions during classroom ‘races’ as it was ‘captured’ in some other interactions I will study below from a gender perspective. Thus it seems fair to ask, in line with contemporary SLL research, two paramount questions with regard to preschool EFL education. Firstly, which gendered discourses are available for preschoolers in the English language classroom? Secondly, how can these gendered discourses affect the potential English language learning of preschoolers?

FPDA as an analytical-layered approach

Although there are a central number of principles of enormous significance to feminism, poststructuralism and discourse analysis, it would be impossible to embark into a detailed examination of each of them here. Rather in the context of our discussion about gender and (English) language learning identities, I will set my sight much lower at briefly introducing key epistemological and analytical aspects of Feminist Poststructuralist Discourse Analysis (FPDA for brevity) (Baxter, 2003).

In a nutshell, FPDA ascertains ‘significant moments’ in which subjects are positioned through discourse and the ways in which subjects experience ‘power’. The feminist poststructuralist agenda could be situated within the reflexive interplay of a number of principles that respond to grand narratives, the univocal and unitary meaning and the fixed identity of subjects defended by a modernist-feminist thought. Baxter (2003) points to a feminist poststructuralism that celebrates the interplay of contesting theoretical positions, the co-construction of multiple versions of meaning in situ and the discursive positioning of subjects that mutually, adversely or contestably craft multiple shifting identities in discursive localised contexts.

In Baxter’s opinion (2003) feminist poststructuralism draws on re-visited versions of principles of feminism (the universal cause, the personal is political and the search for a common voice) and principles of poststructuralism (the scepticism to universal causes, the contestation of meaning and the discursive construction of identity). Positioned together, those principles would imply, for feminist poststructuralism, revisiting the subjective, the planning of deconstructive projects and the assertion of potential transformative projects. This implies a layered analysis.

Firstly, there is a descriptive (denotative) level where classrooms interactions are described in terms of turn-taking to explore how power is discursively allocated – in Baxter’s (2003: 49) words ‘to foreground and pinpoint the moment (or series of moments) when speakers negotiate their shifting subject positions’. Secondly, an interpretative (connotative) level or FPDA commentary is achieved based on the descriptive findings. Baxter (2003) conceives of alternative pathways in this level by engaging multiple voices and viewpoints. Contributing voices include not only the voices of research participants, but also the researchers’ and the voices of those who have highlighted a feminist quest in localizable contexts of discursive practices. Viewpoints seek to make relevant those voices who have not been heard ‘where competing discourses in a given setting seem to lead (temporarily) to more fixed patterns of dominant and subordinated subject positions’, as Baxter (2003: 71) comments.

This ‘joined up interpretative’ approach is complemented in this brief report with my own data reading as researcher, the teachers’ perceptions, obtained via structured interviews and questionnaires, and scholarly work on children’s discourse analysis.

The Goldmedal Kindergarten

The Goldmedal Kindergarten is located in Zipaquirá, a Colombian town near Bogotá. The school subject ‘English’ does not have a national curriculum strategy (at this writing). Therefore, preschool English language programmes are diverse. Most of the English language provision in private institutions, like the Goldmedal Kindergarten, offers a three-year programme. These programmes are graded in three levels. These levels are named in Spanish Pre-Jardín, Jardín and Transición and the English language instruction corresponds to a language intensification program which is in transition towards a bilingual education program. Most of the students attending the Goldmedal Kindergarten live in the metropolitan area of Zipaquirá and belong to families classed as social levels 1, 2 and 3. Zipaquirá has a social stratification system, similar to the one used in Bogotá (the capital city of Colombia) that ranks its inhabitants according to income and area of domicile from 1 to 6. Rank 6 is where the highest standard of living is to be found as well. The female teacher (TP = Teacher Patty) has a BA in Spanish-English and around 10 years of teaching practice.

For the purposes of in-depth analysis, two ‘telling’ moments of ‘classroom races’ were selected according to their significance to concepts of gender as fluid/multiple and to the two questions mentioned above (there are more examples in my current research which I cannot comment on here for brevity). I would also like to sound a note of caution. There are cultural differences across and within EFL classrooms in different countries and regions. The analysis below relates only to the samples of classroom interactions presented and is in no way intended to make generalisations concerning preschool EFL education. However, similar interactions could be ‘mirrored’ across settings and the analysis seeks to make language teachers aware of what may perhaps be happening in their actual classrooms.

Getting to grips with an FPDA analysis of ‘classroom races’

‘Classroom races’, as part of the ‘bread-and-butter’ of many language classrooms, could help us find some answers to the questions about gendered discourses available for preschoolers and how these discourses affect their potential English language learning. As illustrated in my introductory memory, classroom races are practices carried out during English language instruction and imply the negotiation of power relationships.

Drawing on concepts of new literacy studies (e.g. Street 2001), I understand SLL practices as language learning daily ‘experiences’ – not necessarily limited just to the English language classroom – in which power relationships are at stake and position participants at times powerfully and at times less powerfully from a gender perspective.

Classroom races occur as a SLL practice in which preschoolers try to finish an English language activity faster than their other classmates. They also occur when the teacher openly organizes competitions among groups of preschoolers (e.g. part of Aura’s episode). Therefore, sometimes classroom races are ‘private’ because they are ‘secretly’ established alongside the activities proposed by the language teacher, e.g. literacy events such as copying down English words from the board (see two examples below). It seems that the interaction within a gendered network of friend participants positions preschoolers differently during the development of these classroom competitions.

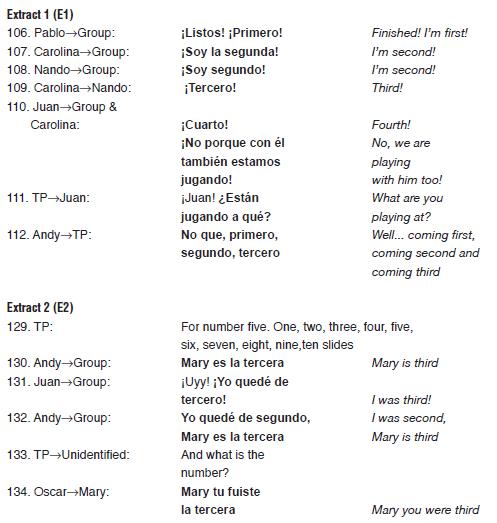

Two examples of ‘classroom races’ around literacy tasks

The data draws on materials filmed in the kindergarten’s three-year EFL programme. The extracts below are taken from a lesson in the 2005 Transición class and were videoed in September of that year. The data comes from a three-year qualitative study (2004-2006) that investigates the positioning of masculinities and femininities in preschool English language education in Colombia (Castañeda-Peña, 2007).

TP (Teacher Patty) develops a number of classroom activities about the English prepositions. After listening to a song about outdoor activities in a children’s park, the preschool students start developing a series of Total- Physical-Response exercises with the concepts of ‘up’, ‘down’, ‘in’ and ‘out’. Then TP moves into a series of literacy exercises. These activities are based mainly in copying down from the board isolated English prepositions and a noun phrase in front of a number of workbook illustrations.

One of these literacy activities requires the preschoolers to copy down the text ‘Down’ from the board (Extract 1). In another moment preschoolers are asked to copy down the phrase ‘Ten slides’ (Extract 2). The transcripts below show the preschoolers ‘racing’ to finish these activities. Carolina and Mary (aged 6) are outnumbered by the boys in this lesson: Pablo, Juan, Andy, Oscar (all aged 6) and Nando (aged 5). Both teacher and students have Spanish as their first language and all names are pseudonyms. As the talk around the literacy activities is conducted in Spanish (in bold), translations are provided in italics. Extracts and turns are indicated in parenthesis in the analysis below for the readers’ reference.

Integrated Denotative and Connotative (FPDA) analysis

Clearly, the interactions above show that ‘private’ games were going on concurrently with literacy activities. Preschoolers were competing to see who could finish the task first. This, I would argue, ignites a few disputes in Spanish in which gendered communicative styles emerge. The communicative styles include for example the use of assertive language attributed normatively to men (e.g. self-centred language and commands) and the use of mitigated language attributed normatively to women (e.g. other-centred language and use of hedges). The analysis (see below) shows that these styles are used indistinctively by both girls and boys in the Goldmedal Kindergarten.

In Extract 1, Carolina appeals to managerial communicative styles (e.g. assertive language). These styles could be normatively considered as masculine but could also embody a very self-assured femininity. Elsewhere (Castañeda-Peña, 2008), Carolina has been identified as a teacher-like figure operating as the teacher’s ‘articulate knower’ in a lesson about the English personal pronouns. An ‘articulate knower’ appears to be a student who rephrases the teacher’s words, organizes her/his classmates and shows off her/his knowledge of the language learnt (Castañeda-Peña, 2007 and 2008, Walkerdine, 1998).

Thus this style is not unknown to Carolina who asserts a powerful position as a language learner able to cope with literacy tasks faster. Interestingly, when I asked TP to reflect about this episode, she constructed Carolina as an English language learner differently and in a much lower status compared to Nando. In her words,

Carolina is a happy girl and she does not get annoyed when she is told off; although she is intelligent she cannot concentrate and has difficulty reading and writing. She might be a kinaesthetic girl because she cannot stay still for a second ... Nando is very intelligent and he is very interested in the English course, he sees in his teachers a model to follow. He likes to compete and be one of the first!

TP’s identity construction of Carolina, from the perspective of this analysis, appears not to reflect Carolina’s gendered identity as a language learner whose status seems to compete with the one given to Nando. There might be a plausible explanation for this situation: unlike Hruska’s research site (2004), it could be said that in the Goldmedal Kindergarten ‘to be learning English’ comprises a high-status identity. Both girls and boys appear to understand this. This is the case because all the children are in fact learning English and see each other as doing so. It appears from Hruska’s study that in English as a Second Language lessons, children whose first language is not English are simply constructed as ‘non-English speakers’ rather than ‘bilingual’.

In the 2005 Transición class, Carolina was for most of the time the only girl in a group otherwise constituted by 5 boys (Oscar, Pablo, Juan, Nando and Andy) – this happened because Mary was absent a number of times.

Consequently, the ‘disruptive’ or kinaesthetic behaviour and the lack of concentration that TP attributes to Carolina might be the result of Carolina’s female friendless construction of English language knowledge in a network of male friendship.

It is interesting to see how in the first dispute, Juan uses a more mitigated language compared to Carolina’s assertive style in a reverse of normativelygiven gendered positions. As soon as Carolina has made her point to Nando, she seems to be backed up by Juan (E1-110) who mitigates his viewpoint confirming that Nando is also included in the game and probably did not mean to take up Carolina’s runner-up position. Juan’s mitigated statement places both Carolina and Nando in a shared egalitarian position as participants in the game and possibly as English language learners who can accomplish classroom literacy tasks quickly and effectively. By comparison with Aura and her ‘I said it! I said it!’ in their minds the motto might read ‘the faster the better’.

Juan’s drawing on the ‘Peer-Approval’ discourse, which in this context brings in an egalitarian status for both girls and boys, fades away when shortly after it is he who wants to seize Mary’s runner-up position. Since the interest here seems to be in gaining the first place in the ‘private’ contest organized around the literacy task, Andy declares, in the ‘Ten slides’ literacy part, that Mary has gained third place (E2-130) – the first place being occupied either by Carolina, Nando, Oscar or Pablo. In a mitigated way, Juan uses a minimal response and announces that he has the third position (E2-131). This is acknowledged by Andy who without any mitigation whatsoever disagrees (E2-132). Interestingly, Oscar, arguably within the ‘Peer-Approval’ discourse, continues to back up both Andy and Mary (E2-134) as a sort of criticism of Juan. This places Juan in an inferior subject position which does not exclude him from the game but warns him about the egalitarian network of assertive femininities and masculinities at work.

This unrestricted gendered network might operate in such a way because in the preschoolers’ eyes, showing effective knowledge of the target language positions them in a higher status where being ‘monolingual’ would mean the opposite. Unfortunately, the dispute is ended by TP and we will never know how it could have been finally resolved. TP also said,

Although ‘competition’ is good for them, when they do this they do not settle down and the yelling in class does distract the other pupils and does not let the children who have not finished the task accomplish it calmly.

There are still two main reflections to be added. Firstly, drawing on the ‘Teacher-Approval’ discourse, we as language teachers might construct students differently and this could be gender-driven. For example, whilst Nando is fully recognized as someone who is ‘very interested in the English course’, Carolina’s kinaesthetic learning style seems to be read as the cause of her lack of attention span and ‘difficulty reading and writing’ in the target language.

This resonates with the ‘pathological’ construction of girls that Walkerdine (1998) explored in the context of girls and mathematics. Girls are constructed ideally as quiet, silent and well-behaved students. Boys are allowed to be playful and naughty! Behaving differently would constitute gender-bending for a girl as she deviates from the normative understanding of what girl students are meant to be.

From the perspective of the teacher, Carolina is read within a ‘pathological’ discourse in which there are no many options available for a girl student to construct herself differently as a language learner – and remember Aura! Paradoxically, that construction of a low-status-girl-student disappears within the ‘Peer-Approval’ discourse voiced by two boys: Juan and Oscar. Within such discourse the assertiveness Carolina has displayed in the literacy activities appears to be compatible with the competitive masculinity displayed by the boys.

Secondly, these findings demonstrate that in the Goldmedal-Kindergarten classrooms particular uses of language cannot be attributed either to just boys or girls. The data reveals that normative uses of language are gender-bent by the preschoolers. In dealing with disputes, research has demonstrated that girls cope with conflict using mitigation in pretend games whilst boys do not even negotiate the conflict (Sheldon 1990, Sachs 1987). However, other research has revealed that such differences are indeed context-sensitive (Nakamura 2001). Cook-Gumperz and Kyratzis (2001: 605) claim that young children (girls and boys) ‘allocate power among themselves in contextually sensitive ways that sometimes reflect gender-based links between specific contexts and power’. In that sense, it has also been found that girls use a ‘double voice’ discourse (Sheldon 1996) where an assertive mode is combined with an egalitarian style in managing conflict.

The analysis of ‘private’ disputes within literacy activities in an English language lesson of the Goldmedal Kindergarten reveals that both boys and girls use such ‘double voice’ device raising traces of the ‘Peer-Approval’ discourse. Within such discourse, assertive masculinities and femininities appear to occupy a similar power position so as to achieve a mutual and cooperative high-status identity (e.g. that of learning English and that of being fast – say number one – and effective at developing literacy tasks). From a discursive point of view it could be speculated that both boys and girls bend normative constructions of masculine and feminine communicative styles while constructing their identity as English language learners. This English language learners’ identity of being ‘the first’ is acknowledged by TP, when she states,

Of course, those ‘competitions’ contribute to the development of a much nicer lesson and they also contribute to all the children wanting to be first!

In the scenario about English language learning that TP presents above, it appears as if ‘being the first’ in a contest-like activity were crucially positive in determining not only the success of a lesson but the construction of good English language learners.

After observing what happened in these literacy activities from a gender perspective, it could be suggested to teachers working with very young children – and other ages as well – to heighten their awareness in order to erode discourses of ‘approval’ that reprimand girls (e.g. Carolina and Aura) for ‘being girls’ in the English language classroom. Alternative positions made available for the pupils through careful activity design and through attention to the emergence of gendered discourses might be helpful although the surfacing of these discourses could be thought of as ‘unpredictable’.

Conclusion

This paper has attempted to answer two questions in line with contemporary SLL research. With regards to gendered discourses available for preschoolers in the English language classroom, it could be said that within the ‘Teacher- Approval’ discourse there are traces of pathological identity construction of girls as language learners. In relation to how these gendered discourses impact on language learner identity, it was illustrated that it is within the ‘Peer Approval’ discourse where girls could find, at times, positions in which their femininities are empowered interactionally. This happens because both boys and girls see each other as (English) language learners. Classroom races, while developing literacy activities, seem to be the perfect site for language learners to interactionally construct these equal ‘gender and language learner’ identity positions.

Thus the argument made throughout these lines has been that the construction of the language learner as ‘being good’ at languages (e.g. in Aura’s words ‘I said it!’ or in Pablo’s words ‘I’m first!’) is also gender-driven. Temporarily, language learners construct high status positions shared by assertive femininities and masculinities. This is achieved by using communicative styles which are gender-bent (e.g. girls and boys combine assertive and egalitarian modes when managing conflict). However, it still seems that girl-students have to cope with more as they tend to be ‘marginalized’ when they ‘break the mould’ (e.g. Aura ‘chipping in’ and Carolina having difficulties reading and writing possibly because she ‘cannot stay still for a second’). For that reason, I suggest that we as language teachers should heighten our awareness of how we interactionally construct our (female) students’ identities and of how we position them discursively. This awareness should also be heightened when paying close attention to the way our students interact in myriad types of language activities (e.g. ‘private’ classroom races).

Rather than providing English language teachers with a particular way of language teaching, this paper is an attempt to primarily understand what happens in the English language classroom from a gender perspective in order to suggest awareness as a ‘transformative action’. What ‘goes on’ is highly situated and localized actions to improve students’ SLL practices could be recommended with the same scope.

However, as I said before, the classroom interactions discussed in this paper could be mirrored across settings in which SLL practices are discursively embedded and could precisely make teachers aware of how the discursive construction of gender and language learner identities could impact their students. This, then, leaves at least two questions opened for further comparative exploration across settings and cultures: How is gender identity (re) constructed in the classroom across ages, cultures, educational levels (e.g. pre-primary, primary, secondary, higher education), and across groups (e.g. only-female, only-male or mixed classrooms) and how does this relate to classroom SLL practices?

References

Baxter, J. 2003. Positioning gender in discourse. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan

Castañeda-Peña, H. 2007. Positioning masculinities and femininities in preschool EFL education. Unpublished PhD Dissertation. Goldsmiths, University of London.

Castañeda-Peña, H. 2008. ‘Interwoven and competing gendered discourses in a pre-school EFL lesson’ in Harrington, K et al. (ed.) Gender and language research methodologies. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Cook-Gumperz, J. and A. Kyratzis. 2001. ‘Child discourse’ in D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen and H. Hamilton. (ed.) The handbook of discourse analysis Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Hruska, B. 2004. ‘Constructing gender in an English dominant kindergarten: Implications for second language learners’. TESOL Quarterly 38/3: 459-485

Nakamura, K. 2001. ‘Gender and language in Japanese preschool children’. Research on Language and Social Interaction 34/1: 15-43

Norton, B. 2000. Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change. Essex, UK: Longman

Norton, B. and A. Pavlenko (eds.). 2004. Gender and English Language Learners. Alexandria, VA: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL)

Pavlenko, A., et al. 2001. Multilingualism, second language learning, and gender. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter

Sachs, J. 1987. ‘Preschool boys’ and girls’ language use in pretend play’ in S. Philips and S. Steele. (eds.) Language, gender and sex in comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Sheldon, A. 1990. ‘Pickle fights: Gendered talk in preschool disputes’. Discourse Processes 13: 5-31

Sheldon, A. 1996. ‘You can be the baby brother, but you aren’t born yet: Preschool girls’ negotiation for power and access in pretend play’. Research on Language and Social Interaction 29/1: 57-80

Street, B. (ed.) 2001. Literacy and Development: Ethnographic Perspectives. London: Routledge

Walkerdine, V. 1998. Counting girls out: Girls and mathematics. London: RoutledgeFalmer

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Harold Castañeda-Peña received his Ph.D. from Goldsmiths, University of London and teaches Gender, language and identity in the School of Language and Communication at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Colombia. He has authored preschool language learning materials. His main research interests include issues of gender identity, bilingualism, second language learning and information literacy.

Métricas

Licencia

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/