DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.11220Published:

2017-08-04Issue:

Vol 19, No 2 (2017) July-DecemberSection:

Research ArticlesA picture is worth a thousand words: portraying language learning experiences in a bilingual school in Honduras

Una imagen vale más que mil palabras: retratar experiencias de aprendizaje de idiomas en una escuela bilingüe en Honduras

Keywords:

educación bilingüe, Honduras, inmersión de una vía, investigación basada en artes, investigación centrada en los niños (es).Keywords:

arts-based research, bilingual education, child-centered research, Honduras, one-way immersion (en).Downloads

References

Abello-Contesse, C., Chandler, P. M., López-Jiménez, M. D., & Chacón-Beltrán, R. (Eds.). (2013). Bilingual and multilingual education in the 21st century: Building on experience. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Alley, D. (1996). Bilingual schools in Honduras: Past, present and future. Journal of the Southeastern Council on Latin American Studies, XXVII (March 1996), 81-90.

Anfara, V. A., Brown, K. M., & Mangione, T. L. (2002). Qualitative analysis on stage: Making the research process more public. Educational researcher, 31(7), 28-38.

Author. (XXXX)

Banfi, C., & Rettaroli, S. I. L. V. I. A. (2008). Staff profiles in minority and prestigious bilingual education contexts in Argentina. In Hélot, C., & de Mejía, A. M. (Eds.), Forging multilingual spaces: Integrated perspectives on majority and minority bilingual education (pp. 140-182). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Chin, J. (2001). A foreigner in my classroom. Unpublished master’s thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada.

Clark, C. D. (2010). In a younger voice: Doing child-centred qualitative research. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Day, E. M., & Shapson, S. M. (2001). Integrating formal and functional approaches to language teaching in French immersion: An experimental study. Language Learning, 51(s1), 47-80.

de Mejía, A. M. (2002). Power, prestige, and bilingualism: International perspectives on elite bilingual education. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

de Mejía, A.M. & Montes Rodríguez, M.E. (2008). Points of contact or separate paths: A vision of bilingual education in Colombia. In Hélot, C., & de Mejía, A. M. (Eds.), Forging multilingual spaces: Integrated perspectives on majority and minority bilingual education (pp. 109-139). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Fortune, T. (2000). Immersion teaching strategies observation checklist. ACIE Newsletter, 4(1), 1-4.

Genesee, F. (1994). Integrating language and content: Lessons from immersion. UC Berkeley: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence.

Genesee, F. (2004). What do we know about bilingual education for majority language students? In Bhatia, T. K., & Ritchie, W. C. (Eds.), Handbook of bilingualism (pp. 547-576). Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

Gropello, E. (2005). Barriers to better quality education in Central America (Report No. 64). Washington, DC, USA: World Bank.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1982). The epistemological and methodological bases of naturalistic inquiry. Educational Communications and Technology Journal, 31, 233–252.

Hamacher, J. (2007). Student perceptions of implicit and explicit instructional approaches in a second language classroom. Unpublished master’s thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada.

Hooley, D. (2005). Teaching mathematics in Honduras. Ohio Journal of School Mathematics. 52, 18-21.

Johnson, R. K., & Swain, M. (1997). Immersion education: International perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Klingner, J. K. & Vaughn, S. (2000). The helping behaviors of fifth graders while using collaborative strategic reading during ESL content classes. Tesol Quarterly, 34(1), 69-98.

Kowal, M. & Swain, M. (1997). From semantic to syntactic processing: How can we promote it in the immersion classroom? In Johnson, R. K., & Swain, M. (Eds.), Immersion education: International perspectives Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

MacIntyre, P. D., Baker, S. C., Clément, R., & Donovan, L. A. (2002). Sex and age effects on willingness to communicate, anxiety, perceived competence, and L2 motivation among junior high school French immersion students. Language Learning, 52(3), 537-564.

Pérez Murillo, M.D. (2013). The students’ views on their experiences in a Spanish-English bilingual education program in Spain. In Abello-Contesse, C., Chandler, P. M., López-Jiménez, M. D., & Chacón-Beltrán, R. (Eds.). (2013). Bilingual and multilingual education in the 21st century: Building on experience. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Quince de los mejores colegios son bilingües [Fifteen of the best high schools are bilingual]. (2013, Jan. 6). El Heraldo. Retrieved from http://www.elheraldo.hn

Ramirez, J. D. (1986). Comparing structured English immersion and bilingual education: First-year results of a national study. American Journal of Education, 95, 122-148.

Secretaria de Educación de Honduras. (2016). Sistema de estadística educativa. [System of educational statistics]. Retrieved from http://estadisticas.se.gob.hn/see/busqueda.php

Schulz, R. A. (1996). Focus on form in the foreign language classroom: Students' and teachers' views on error correction and the role of grammar. Foreign Language Annals, 29(3), 343-364.

Spezzini, S. (2005). English immersion in Paraguay: Individual and

sociocultural dimensions of language learning and use. In A.M. de Mejía, (Ed.), Bilingual Education in South America (pp79-98). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Tedick, D. J., Christian, D., & Fortune, T. W. (Eds.). (2011). Immersion education: Practices, policies, possibilities. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Umaña, Silvia. (2006). Consultaría educativa de noviembre 2006. [November 2006 educational consultation]. (Technical Report). Siguatepeque, Honduras: Comunidad Educativa Evangélica.

UNICEF. (2013). UNICEF Annual Report 2013 - Honduras.

http://www.unicef.org/about/annualreport/files/Honduras_COAR_2013.pdf United Nations Development Program (2013). Table 1: Human Development Index and its components. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/table-1-human-development-index-and-its-components

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

RESEARCH ARTICLES

A picture is worth a thousand words: Portraying language learning experiences in a bilingual school in Honduras1

Una imagen vale más que mil palabras: retratar experiencias de aprendizaje de idiomas en una escuela bilingüe en Honduras

Esther Bettney2

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Bettney, E. (2017). A picture is worth a thousand words: Portraying language learning experiences in a bilingual school in Honduras. Colomb. appl. linguist.]., 19(2), pp. 177-192.

Received: 22-Nov-2016 / Accepted: 12-May-2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/22487085.11220

Abstract

This qualitative study explored the experience of students learning English in an early partial one-way immersion program in Honduras. While immersion research is well-established in various parts of the world, scarce research has focused on programs in Central America. It is important to consider this geographical context as models of bilingual education must be adapted to the local student population (de Mejía, 2002). To address this research gap, written reflections were collected from 203 Grades 1 to 11 students in a one-way immersion program. Through pictures and words, students portrayed their experiences learning English. Two main themes emerged: 1) students' views of their language learning process, and 2) perceived factors which contributed to the learning of English. These themes are discussed in light of key immersion research on student language proficiency, maximizing output, and meaningful language use. This study confirmed results from other immersion studies in certain areas such as the importance of maximizing output, while also demonstrating the importance of continuing to explore students' learning experiences within the Latin American context.

Keywords: arts-based research, bilingual education, child-centered research, Honduras, one-way immersion

Resumen

Este estudio cualitativo exploró la experiencia de estudiantes aprendiendo inglés en un programa de inmersión temprana parcial de una vía en Honduras. Mientras la investigación sobre la inmersión está bien establecida en varias partes del mundo, se ha realizado muy poca investigación en América Central. Es importante considerar que los programas de inmersión en este contexto geográfico como modelos de educación bilingüe debe ser adaptado a las necesidades de la población estudiantil local (de Mejía, 2002). Para tratar esta laguna de investigación, se recolectaron reflexiones escritas de 203 alumnos entre primer y undécimo grado en un programa de inmersión. Los estudiantes representaron sus experiencias aprendiendo inglés a través de dibujos y palabras. Surgieron dos temas principales: 1) el punto de vista de los estudiantes sobre el proceso de aprendizaje del idioma y 2) factores percibidos que contribuyeron al aprendizaje del idioma inglés. Estos dos temas son discutidos tomando en cuenta la investigación de inmersión sobre el dominio del idioma del estudiante, maximización de la producción oral y escrita en su segundo idioma y utilización con significado del idioma. Este estudio confirma los resultados de otras investigaciones sobre inmersión en ciertas áreas como ser la importancia de maximizar la producción y a la vez demostrar la importancia de continuar explorando las experiencias de aprendizaje en el contexto latinoamericano. Estos hallazgos son importantes ya que proveen una perspectiva en las experiencias de aprendizaje de los estudiantes en un contexto inexplorado de inmersión.

Palabras clave: educación bilingüe, Honduras, inmersión de una vía, investigación basada en artes, investigación centrada en los niños

Introduction

From 2006 to 2017, I worked at The Pines Bilingual School (TPBS)3 in Honduras, as a classroom teacher, program administrator, and curriculum coordinator. During this time, I became concerned that students were spending up to thirteen years in a bilingual school, yet many were graduating with low levels of English proficiency. My concerns reflected a long-standing issue, as an outside consultant found that only 40% of students at TPBS were able to express themselves at grade-level standards (Umaña, 2006)”title” : “Consultar\ u00eda educativa (Educational Consultation. As I shared my concerns with other administrators and teachers, we realized in order to address them, we needed the voices of those who were most impacted by these issues—our students.

This study explored students’ perspectives on learning English in an early partial one-way immersion program in Honduras. According to Tedick, Christian, and Fortune (2011), one-way immersion programs serve linguistically homogenous students who speak the majority language and have little proficiency in the immersion language upon entry. These programs are intended to ensure that students achieve academically while promoting cross-cultural understanding and additive bilingualism in which students add new languages to their linguistic repertoire.

Immersion research has been a well-established field since the first immersion programs were established in Canada in the 1960s. Since then, the field has grown substantially with ongoing research in many regions of the world, yet very little research has focused on immersion programs in

Central America. Both Johnson and Swain (1997) and Tedick et al. (2011) comment on the growth of immersion programs in various parts of the world, yet fail to mention examples from Central or South America. Some research has focused on immersion programs in South American countries with high human development scores (e.g., Abello-Contesse, Chandler, López-Jiménez, & Chacón-Beltrán, 2013; de Mejía, 2002). While immersion programs in Central American countries such as Honduras may share similarities with immersion programs in South America, lower human development scores and lower educational attainment (Gropello, 2005; UNICEF, 2013) indicate possible differences as well.

This exclusion of programs in countries like Honduras from ongoing immersion research becomes more pronounced when considering the high numbers of bilingual programs that exist in Central America. In Honduras, there are over 800 registered bilingual schools (Secretaria de Educación de Honduras, 2016) compared to approximately 100 in Colombia (de Mejía & Montes Rodríguez, 2008) and approximately 200 in Argentina (Banfi & Rettaroli, 2008). Some bilingual schools in Honduras fit de Mejia’s (2002) profile of international schools that typically serve a monolingual population who are interested in further educational opportunities in Europe or North America. These schools originally served the children of executives working with the Honduran fruit export industry though over the past few decades, their student population has drawn more from upper class Hondurans (Alley, 1996). While some larger bilingual schools fit de Mejía’s (2002) definition, the majority fit better within Tedick et al.’s (2011) definition of one-way immersion programs as they follow the national Honduran curriculum.

Bilingual schools in Honduras represent an important segment of schools as fifteen of the twenty highest ranked high schools in the country are Spanish-English bilingual schools (Quince, 2013). Yet there is a lack of quality control amongst Honduran bilingual schools with a high variability of the quality of programs, staff, curricula, and resources as well as student achievement (Alley, 1996). As well, the Honduran government does not outline expectations for second-language achievement as there is no national English language curriculum for bilingual schools. Even at some of the most well-established schools in the country, there are concerns regarding the level of student bilingualism (Hooley, 2005). These challenges must also be seen within the context of extremely low national educational standards. Honduran bilingual schools operate within a different educational context than other immersion programs and therefore represent a crucial area for research.

It is important to understand the perspectives of students within immersion programs in Honduras. Students’ viewpoints are especially important in bilingual education where a link has been established between students’ perceptions and their rates of second-language acquisition (Hamacher, 2007). It is therefore important to ask students about their own experience and to allow their voices to be heard in the issues that concern them (Clark, 2010). While little research has been done on immersion programs in Central America, research has been conducted on students’ perspectives in other bilingual contexts. Pérez Murillo (2013) conducted a study in Spain to explore students’ attitudes toward their bilingual education. She administered a questionnaire to 382 elementary and high school students. Students described positive attitudes toward the personal benefits of learning English, such as the role of English as a lingua franca, and the importance of English for future studies and jobs. The majority of students indicated they had a high level of English, though they rated their receptive skills as higher than their productive. While this study took place within a different context, it provides insight into students’ perspectives on their own learning within a bilingual program.

Spezzini (2005) conducted a study in an English immersion school in Paraguay to explore students’ perspectives on their language learning experience. She gathered a variety of types of data from 34 native-Spanish speaking Grade 12 students. Students perceived their English speaking skills to be low, even though 85% of students were rated by native-raters as relatively easy to understand. While the sample size was small and it only included students from one school, it is important as it explores the experience of students in an immersion program in Latin America.

While these studies explore students’ perspectives within other bilingual contexts, there is a clear need for inquiry of this type for programs in Central America. In order to address this research gap, the following question guided this study: How do immersion students at TPBS describe their experience learning English?

Research Context

This study explored students’ perspectives on their learning of English at a private Spanish-English school (TPBS) with approximately 250 students from Junior Kindergarten to Grade 11. The school was started in 1990 by local parents in response to concerns about the public education system in Honduras. TPBS followed an early partial immersion model, beginning in Junior Kindergarten with about 50% of classes taught in Spanish and 50% of classes in English. Approximately 99% of TPBS’ students spoke Spanish as their first language (L1) and English as their second language (L2). The students at TPBS came from varied socioeconomic backgrounds, with 29% of students at TPBS receiving a needs-based financial bursary at the time of the study. Traditionally, bilingual education in Honduras has only been accessible to the urban upper class (Alley, 1996), yet TPBS students’ represent a type of bilingual school which is accessible to a more diverse population.

Methodology

A qualitative approach was suitable for this study based on the exploratory nature of the research question. In qualitative inquiry, researchers gather and study a variety of materials in an attempt to interpret the meaning people give to their own experiences (Denzin & Lincoln, 2008).

A need has been identified in second language research for more qualitative open-ended inquiry, instead of surveys or forced-answer questions (Tse, 2000). Qualitative inquiry is also well-suited to the context-dependent nature of this study, which de Mejía (2002) identified as important in bilingual education research.

This study draws from two complementary qualitative approaches: child-centred research and arts-based research. In child-centred research, the experiences of children and young adults are valued by providing opportunities for them to express their views through methods which are attractive, comfortable and accommodating to them (Clark, 2011). Arts-based research includes non-traditional forms of data to expand the types of methods used in educational inquiry (Sullivan, 2013). These methods were selected because they emphasized the voices of participants and encouraged students’ to share about their experiences through age-appropriate means.

For this study, I used both drawings and written responses as forms of data generation. Drawing is a common method within both child-centred and arts-based research. According to Clark (2011), a strong proponent of child-centred research, a child’s drawing may be “drawn to share with an adult, can link us to profound meanings, if we are open to what the young are showing and saying, and able to shift our on understanding into that framing” (p. 158). She states that drawings are suitable for children between 5 and 12 years old and are especially appropriate in cross-cultural situations where language could be a barrier to expressions. Students wrote a description underneath their picture which provided context for their drawings and informed my interpretations.

I created age-appropriate reflection prompts which asked students about their experience learning English. I provided the prompt to students in both English and Spanish and they could respond in either words or drawings and in whichever language they preferred or a mix of both. Prior to the collection of data, a pilot study was conducted with the reflection prompts at two other bilingual schools in Honduras. Based on the pilot study, adjustments were made to clarify the language used in the reflection prompts thus increasing their validity. Peer debriefing was employed through discussions with various teachers, as well as the research assistant, to promote credibility. Throughout the data collection process, detailed notes were taken in a research journal to document the steps taken and decisions made. As well, I wrote a number of personal reflections to consider my role as a researcher and its potential influence on data collection.

Participants

All students at TPBS from Grades 1 to Grade 11 were invited to participate in this study. It was important to invite all students to participate, as this was an important cultural consideration in Latin American cultures that place a high value on community (Chin, 2001). In total, 203 students in Grades 1 to 11 returned a signed Letter of Information and Consent form and participated in the study. Table 1 shows the total number of students, as well as the number of participants and non-participants, for each grade.

Analysis

Once all reflections were completed, I began a process of inductive analysis by reading through the reflections for each grade level and coding the data from each drawing or piece of writing on a sticky note. After coding Grades 1 to 4, I removed the sticky notes with the codes and began to organize them into categories and created a provisional code tree. I then applied my provisional codes and categories to finish coding the rest of the data, adding and collapsing codes and readjusting categories as necessary. After finishing coding all the data, I returned to the Grades 1 and 2 to recode them, as a method of checking intra-rater reliability. Based on the code tree, two main themes emerged which I will now describe in my results section.

Trustworthiness. The data analysis was heavily guided by the work of Anfara, Brown, and Mangione

Table 1. Participants and Non-Participants by Grade Level

|

Participants |

Non-Participants |

Total Students in Grade | |

|

Grade 1 |

18 |

3 |

21 |

|

Grade 2 |

23 |

2 |

25 |

|

Grade 3 |

20 |

0 |

20 |

|

Grade 4 |

15 |

0 |

15 |

|

Grade 5 |

22 |

2 |

24 |

|

Grade 6 |

25 |

0 |

25 |

|

Grade 7 |

11 |

1 |

12 |

|

Grade 8 |

25 |

1 |

26 |

|

Grade 9 |

14 |

0 |

14 |

|

Grade 10 |

19 |

2 |

21 |

|

Grade 11 |

11 |

0 |

11 |

|

Total |

203 |

11 |

214 |

(2002). The authors call for qualitative researchers to be more explicit in their description of the research process to promote credibility. Credibility was established for this study through prolonged engagement in the field, thick description of the research context, creating an audit trail, use of peer debriefing, and triangulation and practicing reflexivity.

Results

In regards to the results, 203 students in Grades 1-11 drew and wrote about their experiences learning English. Through the analysis of these drawings and written reflections, two main themes emerged: 1) students’ views of their language learning process and 2) perceived factors which contributed to the learning of English.

Language Learning Process

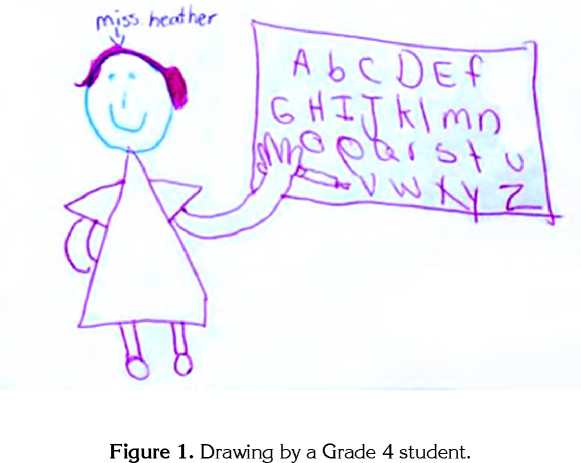

In regards to the language learning process, students discussed two main sub-themes: “poco a poco” and language proficiency. One common belief expressed by students was that learning English was a process that took time, epitomized by the Spanish phrase “poco a poco,” translated as little by little in English. Many commented on how difficult it had been when they first started to learn English (as young as three years old) but over time they saw how much they had learned. One Grade 4 student said, “I love to learn English but at times it has been difficult but through time I am learning more and I know two languages and I know how to do more”4 (translated). In Figure 1, another Grade 4 student drew a picture of her Kindergarten teacher smiling and pointing to the alphabet on the board. Though the student was currently in Grade 4, she chose to draw a picture of her teacher from six years ago when reflecting on her experience learning English which points to her perspective on the importance of her earliest years.

While students recognized it had been difficult to learn English, they believed starting to learn English at a young age had been essential to their success. One Grade 10 student explained:

I guess that the fact that I started learning English since I was pretty young (3 years old) is really important. When we are young, we learn really fast and English is a hard language, but since it has been a huge part of our lives is not as hard as for others who started learning English when they were older.

Students also described their perceived language proficiency in English. Most students

4 I translated all Spanish quotations into English. Translations were checked for accuracy by a bilingual research assistant. All translated quotations are in italics.

believed they had a relatively high level of English, although they used a variety of measurements to judge their own level, including their ability to use English to accomplish certain tasks: reading English books or accessing English media. Students also determined their competency through the evaluations of others, especially North Americans whom they met outside of the school. One Grade 8 student said that when his parents’ friends from the U.S.A. congratulated him on his level of English, “It filled me with a great deal of honour, as if I was on the honor roll” (translated).

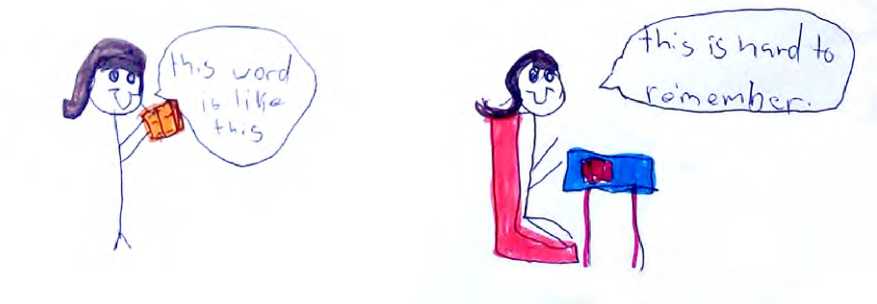

While students generally believed they had high levels of English, some common struggles were also identified. Elementary students frequently mentioned forgetting English words or mixing up English and Spanish, when speaking or writing. One Grade 5 student drew a vivid picture of a student saying, “This is hard to remember” in response to their teacher explaining a word (Figure 2). While both the teacher and student are depicted as smiling in the drawing and working in partnership, the student’s words indicate a level of frustration with trying to remember English words.

Older secondary students were more likely to focus on difficulties with specific grammar rules or types of words, such as homophones. They also focused on certain social challenges associated with learning a second language such as making mistakes in front of their peers. One Grade 11 student said, “For me the hardest part of learning English is speaking it because sometimes if we say one word wrong or we use a wrong word other (sic) can make fun of you.” In most cases, students noted that their receptive skills of reading and listening were higher than their productive skills of writing and speaking, but there was a great deal of variety within and between grades.

In sum, students believed language learning was a process that took time and had begun for them at a very young age. While students noted certain deficiencies, they described their English language proficiency in positive terms.

Contributing Factors

While students commented on their overall experience learning English and their perceived competence, students also identified three types of factors which they believed contributed to their learning of English: individual, school, and external.

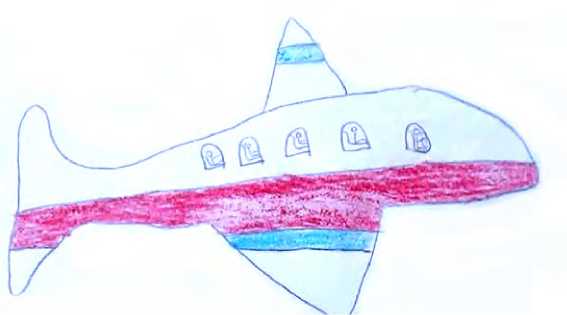

In regards to individual factors which impacted their learning of English, students in a variety of grades identified specific reasons why they wanted to learn English. Some explained immediate reasons, such as personal interest and enjoyment. One Grade 6 student wrote, “I love English because it is interesting and more fun” (translated). A number of older students noted that they enjoyed learning English because they could access English media and literature. One Grade 10 student wrote, “Thanks to this school, I can watch TV shows in English, read English books, or watch movies. And I just love that!” Other students focused on English as a tool to help them in their lives and their family’s lives, such as translating for their parents. One Grade 4 student drew a picture of an airplane (Figure 3) and wrote: “I learn more and more everyday and when I go to the U.S.A. I can talk with everybody.”

This student valued her experience learning English as it allowed her to communicate with others when she travelled. Older students also focused on the positive impact of English on their future. One Grade 8 student wrote, “For me it is a great privilege to study English because it will open many doors for jobs” (translated). Students as young as Grade 4 identified both immediate and future reasons for learning English which contributed to their motivation.

Many students indicated English had been easy for them to learn because of classroom work habits. One Grade 6 student wrote, “Learning English has been easy because I pay attention and study,” and drew a picture of her and her classmates watching the teacher write on the board. Her explanation reflects

her belief that by facing the front and listening to the teacher, she was able to learn English effectively. Students also recognized the potential outcome of inattention, as one wrote, “Paying attention in class made me capable of having long talks in English. If I had payed (sic) attention when young I would be even better” (Grade 9). The importance of listening to and watching the teacher during class time was demonstrated throughout the drawings and written reflections of students from Grade 1 to 11.

Students also identified factors at school which they believed contributed to their learning of English. In general, students described their experience learning English at TPBS in very positive terms. One Grade 9 student wrote, “I think that everything that I learn in school helps me to improve my English.” Some transfer students commented on the difference between TPBS and their previous schools. One Grade 11 student wrote, “I feel like my English has improved a lot since I came here in seventh grade. I’ve been in three different schools here in Honduras, and I really (think) TPBS is the best one.”

While students reflected on the English program in general, the majority of their descriptions focused on their individual English classrooms.

Overwhelmingly, elementary students described traditional classrooms as a teacher at the board, students sitting in their seats and looking toward the teacher. In Figure 4, a drawing by a Grade 1 student, the teacher is shown at the front of the classroom, smiling and standing beside a white board with numbers on it. The students are sitting at a table, facing the front of the classroom, so only the backs of their heads are visible. On the right hand side, a clip chart is shown which is used by the teacher to monitor student behaviour, and is often hung at the front of the classroom.

Many elements from this picture, including a smiling teacher standing at the front of the classroom beside a white board, and students facing the front of the classroom were repeated throughout the drawings. For example, 75% of the pictures drawn by Grade 1 and 2 students included a teacher writing on a white board. These drawings indicated that students primarily linked their learning of English to a traditional, teacher-led classroom, especially in the younger grades.

Students strongly emphasized the impact of their teachers on their learning and primarily described their teachers in a positive light. One Grade 7 student wrote, “It has been easy for me to learn English

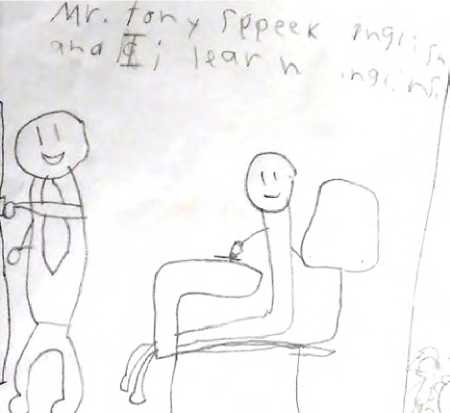

because of the teachers I have had’ (translated). One Grade 2 student wrote about her current English teacher: “I love it when she teaches (the) class. I love her very much because she teaches us things and I am learning a lot” (translated). In the more advanced grades, students demonstrated an explicit trust in their teachers’ desire to help them learn. One Grade 9 student wrote, “I don’t think teachers would do something that won’t help us learn English.” Students believed their English teachers supported their learning through explaining things clearly to them, correcting their oral and written mistakes, and through informal conversations outside of class. While some students noted criticisms of specific teachers, students primarily portrayed their teachers positively and believed their teachers had played a key role in their learning. One Grade 4 student summed up this belief about the impact of teachers on their learning of English in his drawing with the caption, “Mr. Tony speek inglish and I learn inglish” (Figure 5). This caption indicates that the student saw his teacher as having a very direct impact on his learning of English, as he believed he simply needed to listen to his teacher speak in English and he would learn it.

While students emphasized the role of their teachers, they also noted key practices in the classroom which supported their learning of English.

Students first noted reading as a key practice. In some of the younger grades, students drew their teachers reading to them or depictions of the school library. In Figure 6, a Grade 2 students drew a picture of her teacher reading a book to two students, and captioned the drawing, “I like.”

In the upper grades, students identified independent reading as a key factor which had supported their English acquisition. One Grade 10 student noted, “Reading a lot of English books helps me find a lot of English words I didn’t even (know) they existed so that has really help (sic) me learn English.”

Some older students focused on the importance of speaking in English as a key factor which supported their language learning. They believed the school’s policy that high school students speaking English at all times in the English classroom was a key factor which helped their learning of English, even though it was difficult at times. Some students believed the school should extend this policy, suggesting there should be “two or three days that we only speak English” (Grade 10). Students mentioned that they had some opportunities to participate in class discussions, but they felt their classes should emphasize more oral opportunities. One Grade

Figure 6. Drawing by a Grade 2 student.

11 student stated, “I would love if we did more talking in class.” Many older students indicated speaking English was a key factor which supported their language growth and believed there were key practices at school which supported their growth, but also areas for improvement.

Finally, students described external factors which had contributed to their learning of English, including their linguistic surroundings and their use of English outside of school. Students noted they had English-speaking family members either in Honduras or abroad which they believed were very important in supporting them to learn English. On the other hand, some students believed living in Honduras was a barrier to learning English. One Grade 9 student wrote: “Living in an environment surrounded by Spanish-speaking people have (sic) limited me from expanding my English.”

Many high school students emphasized how their use of English outside of school had a positive impact on their language achievement. Students focused on two main uses: translating for English-only speakers and accessing English media. Many students mentioned the positive impact of translating on their level of English. They focused primarily on opportunities they had to translate for mission teams or medical brigades who came to Honduras. One Grade 10 student wrote, “I translated last year and I could really see how translating helped my English level.” Students noted the school should promote more opportunities for translating, as it was only one or two times per year and only in the upper grades. Students also noted the impact of accessing English media on their language growth and stated that they watched English TV and movies and listened to music in English. One Grade 9 student noted, “Watching videos, hearing music can help us to learn more English, because we learn more words that we can use.” Students noted there was some use of English media in their classrooms, but that it was not strongly emphasized. They believed that outside of school opportunities to use English were important in their language growth, but they also proposed the school should integrate more media opportunities into the English classroom.

In sum, students identified individual, school, and external factors which impacted their learning of English. In most cases, they discussed how these factors had contributed to their learning, but they, at times, identified how deficiencies in these areas limited their English achievement. They also shared their views on their language learning in regards to the continual nature of the process and their perceived language proficiency.

Discussion and Conclusions

The main research question which guided this study was, “how do immersion students at TPBS describe their experience learning English?” Based on the results, students described a very positive picture of their classroom experiences and their perceived proficiency. They believed their English teachers played a key role in their success and shared few criticisms of their teachers. This finding was consistent throughout the grade levels. In older grades, students did criticize certain classroom and school practices, such as a lack of English media use in the classroom and a need for more translating opportunities.

I will now consider the results in regards to three main areas for discussion: 1) student language proficiency, 2) maximizing output, and 3) meaningful use of language.

Student Language Proficiency

Part of the original impetus for this study was my concern that our students had low levels of English proficiency. Yet, in this study, students described their perceived level of English proficiency in positive terms. This contradicts both Umaña’s (2006) evaluation and more recent research at TPBS where English teachers indicated students’ proficiency level was lower than they believed it should be (Bettney, 2015). Others have noted that discrepancies often exist between students’ beliefs about their language proficiency and others’ ratings (Schulz, 1996). Yet, it is interesting to note the patterns for these discrepancies are not always consistent. For example, in Spezzini’s (2005) study, the opposite pattern emerged, as students perceived their English speaking skills as low, even though 85% of students were rated as relatively easy to understand. One explanation may be that regardless of the pattern of the discrepancy, each group measures students’ proficiency differently. In my study, students evaluated their proficiency based on tasks they were able to accomplish in English as well as on the comments of native English speakers outside of school. Teachers, in contrast, may have measured students against English language levels of first language students. Teachers also lacked clear objectives which hampered effective evaluation of students’ achievement (Bettney, 2015). The measurement of English language proficiency is especially challenging as national standards do not exist for bilingual schools. Liberale and Megale (2016) note a similar issue within the Brazilian context, stating that no laws exist to regulate procedures within bilingual education. Therefore, the question of student achievement within bilingual schools in Latin America requires further exploration. Clear standards for language proficiency must be determined in order to provide a standard by which to measure student achievement.

Discrepancies also existed between this study and other immersion research in regards to students’ perceived academic versus social language proficiency. In a variety of contexts, immersion students have shown a higher level of academic versus social language proficiency (Abello-Contesse et al., 2013). In contrast, students saw their use of English in non-academic settings as one of their strengths and commented on their use of social forms of English in a variety of contexts outside of school. This finding may indicate a more balanced level of academic and social language skills at TPBS compared to studies conducted within other immersion programs. As well, while many students believed their productive skills were lower than their receptive skills, which follows the pattern found in other immersion studies (Tedick et al., 2011, Pérez Murillo, 2013); this finding was not as robust as noted elsewhere. Unfortunately, no studies were found which explored academic versus social or productive versus receptive language proficiency within the Central or South American context, so the comparisons are limited. It may be that this finding which contradicts other studies does not indicate a pattern within bilingual schools in Honduras or Central America, but instead reflects a unique feature of the city where TPBS is located. In another study conducted at TPBS which explored students’ identity, participants noted the city traditionally had a high percentage of English speakers as a large number of North American missionaries had been based there for decades (Bettney, 2016). TPBS students may therefore have had additional opportunities to interact with English speakers, and therefore strengthen their social and productive skills, while students in other immersion settings are more limited to classroom interactions.

These findings regarding students’ perceived language proficiency present both implications for practice and areas for future research. First, there is a clear need to ask students about their language learning, including their opinion of their achievement and setting their own language learning goals. The need for suitable standards at TPBS and within bilingual schools throughout Latin America is clear. As well, further exploration is required to determine whether the pattern of strong social and productive skills is unique to TPBS or reflects a regional characteristic and to explore the possible contributing factors. Unfortunately, as scarce research currently exists on bilingual education in Central America, it is not possible to predict at this point whether these patterns are reflected throughout this region.

Maximizing Output

In this study, students discussed two main factors which have been linked as contributing to target language output in an immersion classroom. First, students described a traditional, teacher-centred classroom. Especially in the younger grades, students placed teachers at the center of their learning and saw the students’ role as paying attention and studying. Even in the upper grades, while students played a more active role in their own learning, they still described their role as primarily receiving information from their teachers. This finding is important as researchers have noted this weakness in other immersion programs, as teachers often play a more dominant speaking role and students are therefore provided with fewer opportunities to speak, compared to first-language classrooms (Genesee, 1994; Ramirez, 1986). This lack of opportunities has been linked to lower productive skills (Abello-Contesse et al., 2013). A number of strategies have been identified which could help TPBS increase opportunities for student output, such as cooperative learning to increase peer-to-peer interactions (Klinger & Vaughn, 2000; Kowal & Swain, 1997), an increase in output-oriented activities and limiting the amount of teacher talk (Fortune, 2000). Yet, it is important to note TPBS students described the teacher-centred approach in positive terms and a teacher-centred classroom may be in accordance with educational and cultural norms in Honduras. When considering implications for practice, it is important to select practices that will be acceptable to both students and teachers within a given context. While maximizing student output is a key factor, it is important to consider how to apply this principle in culturally appropriate ways.

The second factor was students’ reticence to speak English in front of their peers, which has also been explored in other immersion settings. MacIntyre, Baker, Clément, and Donovan’s (2002) study of Grade 7, 8, and 9 students in a late French immersion junior high school in Canada found students’ willingness to communicate in their second language grew as their L2 competence increased. Yet, Spezzini (2005) conducted a study in an English immersion school in Paraguay and found Grade 12 students unwilling to use English in front of their peers despite their use of it elsewhere. The students believed the school could do little to encourage them to speak English at school as it was impossible to counteract their desire to avoid speaking English to their Spanish-speaking peers. Hooley (2005) noted at Academia Los Pinares, an elite bilingual school in Honduras, even upper high school students still do not feel completely comfortable conversing in the classroom in English. Hooley (2005) claims their reticence is not a reflection of a cultural social norm, as Honduran students are expressive and verbal within the classroom, just not in the English language. In contrast, TPBS high school students strongly supported their school’s English-only speaking policy, even while acknowledging it was uncomfortable to speak in front of their peers in English. It appears TPBS created an environment in which students were willing to participate in English, and believed it was important to their learning, even if it made them uncomfortable. Further research is required to determine the factors contributing to students’ willingness to communicate in English within a variety of contexts to determine whether this finding reflects a pattern seen at other bilingual schools in the region or whether it is unique to TPBS.

Meaningful Use of Language

While students generally described challenges related to target language output, older students indicated key independent practices which contributed to their learning of English. Students noted how meaningful language opportunities, such as translating and accessing English media, both increased their motivated to learn and supported their learning of English. This finding is important as research has shown that immersion students require meaningful opportunities to interact with their second language (Day & Shapson, 2001; Genesee, 1994). Albello-Contesse et al. (2013) argue that a lack of opportunities to use language in a variety of ways within the English classroom can lead to a narrow type of academic-only language. In this study, TPBS students indicated a consistent use of English outside of the classroom, but they did not see meaningful opportunities provided in the English classroom. Students instead sought out opportunities to use English for their own purposes. This is an important finding as it conflicts with other studies in South America (de Mejía, 2002; Spezzini, 2005) which indicate students often lack an immediate need for their second language which can have a negative impact on their motivation. In contrast, in the TPBS study, students expressed both immediate and long-term uses of English which positively impacted their motivation and led to increased language growth. One possible explanation is that the students at TPBS may have had access to a larger percentage of English speakers compared to students in other settings. As noted above, the city where this study was conducted had a very high percentage of North American inhabitants as a result of a long-standing missionary presence (Bettney, 2016). Students therefore were more likely to interact with English speakers on a regular basis, as well as have translating opportunities, which may have contributed to their more immediate need for English. In elite bilingual schools, both in

Honduras and throughout Latin America, students may focus more on their long-term language needs, as graduates often seek post-secondary education abroad in English-speaking countries. In the case of TPBS, with a student population from a wider socioeconomic background, most students will remain in Honduras for university studies. Therefore, their motivation to learn English may be linked to their more immediate language needs, such as translating for medical teams.

While students in this study currently sought out meaningful uses of their language which supported their language growth, they noted a disconnect between these uses and their classroom learning. TPBS could consider incorporating meaningful language uses at school, in order to prioritize students’ identified immediate uses for English outside of school and, therefore, maximize their motivation. Students mentioned that more opportunities for translating or more practical writing assignments would help TPBS to increase the effectiveness of the English program.

In sum, students drew and described their experience learning English at TPBS in very positive terms. Students believed they demonstrated a high level of English proficiency, yet there were some concerns noted in regards to maximizing target language output and the meaningful use of language. The results from this study are not meant to be representative of all students within bilingual schools in Honduras, but instead characterize the experiences of a group of students at TPBS during the time of this study. While it is not possible to form generalizations based on this exploratory study, certain implications for practice have been noted which could be considered at TPBS as well as within other contexts. First, schools should seek out students’ voices in their own educational journey in order to address discrepancies between teacher and students’ perceptions of language proficiency. As well, schools should include culturally appropriate instructional strategies which maximize target language output. Finally, teachers should also look for opportunities to link classroom learning to students’ use of language outside of school to increase student engagement.

In regards to limitations, I acknowledge the risk of misinterpretation which is inherent in all qualitative studies, and even more so when conducted in a bilingual and bicultural context. As well, I may have interpreted the reflections through my own bias based on my role at TPBS. In order to address some of these potential limitations, I practiced reflexivity throughout my study through detailed reflections in my research log. While my role at the school presents some limitations, it can also be seen as a strength as participants demonstrated a high level of trust and confidence in me as a researcher shown in the high participation rate.

Students at TPBS reflected a wide variety of socioeconomic backgrounds compared to many bilingual schools throughout the region. I did not gather individual information on students’ income levels as it did not fit within the research design, but students’ varied backgrounds may have influenced certain results such as English language use outside of school. The potential interaction of income and students’ language learning experience would be another area for future research. As well, certain findings from this study appear to conflict with other studies such as students’ willingness to communicate in English in the English classroom. As opposed to reflecting new patterns, these findings may in reality be related to the types of questions asked or students’ desire to appear supportive of the English program because of my leadership role. Due to the nature of this study, it was not suitable to explore each of these potential limitations, but they represent areas for future research.

The study was exploratory by nature, partly because of the scarce research on bilingual education within Honduras and Central America. This lack of research limits the ability to draw direct comparisons within this geographical region. While only limited comparisons have been made, a number of key areas for research have been identified to guide future studies. First, future studies should consider the lack of standards for bilingual education at both the national and regional levels. Secondly, the findings from this study conflicted research conducted in other contexts in regards to social/academic and productive/receptive language proficiency. This difference requires further exploration to determine if these patterns are unique to TPBS or reflect a general pattern in this region. Finally, studies are required to explore the impact of culture on students’ willingness to communicate in English and culturally appropriate strategies to support target language output.

References

Abello-Contesse, C., Chandler, R M., López-Jiménez, M. D., & Chacón-Beltrán, R. (Eds.). (2013). Bilingual and multilingual education in the 21st century: Building on experience. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Alley, D. (1996). Bilingual schools in Honduras: Past, present and future. Journal of the Southeastern Council on Latin American Studies, XXVII, 81-90.

Anfara, V A., Brown, K. M., & Mangione, T L. (2002). Qualitative analysis on stage: Making the research process more public. Educational researcher, 31(7), 28-38.

Banfi, C., & Rettaroli, S. (2008). Staff profiles in minority and prestigious bilingual education contexts in Argentina. In C. Hélot & A. M. de Mejía (Eds.), Forging multilingual spaces: Integrated perspectives on majority and minority bilingual education (pp. 140182). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Bettney, E. (2015). Examining the Teaching and Learning of English in an Immersion Program in Honduras (Unpublished master's thesis, Queen's University, Kingston, Canada.

Bettney, E. (2016). Impact of a Spanish-English immersion program on participants’ national and cultural identity. Paper presented at CARLA International Conference on Immersion and Dual Language Education. Minneapolis.

Chin, J. (2001). A foreigner in my classroom. Unpublished master's thesis). Queen's University, Kingston, Canada.

Clark, C. D. (2011). In a younger voice: Doing child-centred qualitative research. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Day, E. M., & Shapson, S. M. (2001). Integrating formal and functional approaches to language teaching in French immersion: An experimental study. Language Learning, 51 (s1), 47-80.

de Mejía, A. M. (2002). Power, prestige, and bilingualism: International perspectives on elite bilingual education. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

de Mejía, A. M., & Montes Rodríguez, M. E. (2008). Points of contact or separate paths: A vision of bilingual education in Colombia. In C. Hélot & A. M. de Mejía (Eds.), Forging multilingual spaces: Integrated perspectives on majority and minority bilingual education (pp. 109-139). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y S. (2008). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y S. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research (3rd ed.; pp. 1-45). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fortune, T (2000). Immersion teaching strategies observation checklist. ACIE Newsletter, 4(1), 1-4.

Genesee, F (1994). Integrating language and content: Lessons from immersion. UC Berkeley: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence.

Gropello, E. (2005). Barriers to better quality education in Central America (Report No. 64). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hamacher, J. (2007). Student perceptions of implicit and explicit instructional approaches in a second language classroom (Unpublished master's thesis). Queen's University, Kingston, Canada.

Hooley, D. (2005). Teaching mathematics in Honduras. Ohio Journal of School Mathematics, 52, 18-21.

Johnson, R. K., & Swain, M. (1997). Immersion education: International perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Klingner, J. K. & Vaughn, S. (2000). The helping behaviors of fifth graders while using collaborative strategic reading during ESL content classes. TESOL Quarterly, 34(1), 69-98.

Kowal, M. & Swain, M. (1997).From semantic to syntactic processing: How can we promote it in the immersion classroom? In R. K. Johnson & M. Swain (Eds.), Immersion education: International perspectives (pp. 284-310). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Liberali, C. F, & Megale, A. H. (2016). Elite bilingual education in Brazil: An applied linguist's perspective. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 18(2), 95108.

MacIntyre, R D., Baker, S. C., Clément, R., & Donovan, L. A. (2002). Sex and age effects on willingness to communicate, anxiety, perceived competence, and L2 motivation among junior high school French immersion students. Language Learning, 52(3), 537-564.

Rérez Murillo, M. D. (2013). The students' views on their experiences in a Spanish-English bilingual education program in Spain. In C. Abello-Contesse, R M. Chandler, M. D. López-Jiménez, & R. Chacón-Beltrán (Eds.), Bilingual and multilingual education in the 21st century: Building on experience (pp. 179-202). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Quince de los mejores colegios son bilingües [Fifteen of the best high schools are bilingual]. (2013, Jan. 6). El Heraldo. Retrieved from http://www.elheraldo.hn

Ramirez, J. D. (1986). Comparing structured English immersion and bilingual education: First-year results of a national study. American Journal of Education, 95, 122-148.

Secretaria de Educación de Honduras. (2016). Sistema de estadística educativa. [System of educational statistics]. Retrieved from http://estadisticas.se.gob. hn/see/busqueda.php

Schulz, R. A. (1996). Focus on form in the foreign language classroom: Students' and teachers' views on error correction and the role of grammar. Foreign Language Annals, 29(3), 343-364.

Spezzini, S. (2005). English immersion in Paraguay: Individual and sociocultural dimensions of language learning and use. In A.M. de Mejía, (Ed.), Bilingual Education in South America (pp.79-98). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Sullivan, G. (2013). Research acts in art practice. National Art Education Association, 48(1), 19-35.

Tedick, D. J., Christian, D., & Fortune, T W (Eds.). (2011). Immersion education: Practices, policies, possibilities. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Tse, L. (2000). Student perceptions of foreign language study: A qualitative analysis of

foreign language autobiographies. The Modern Language Journal, 84(1), 69-84.

Umaña, S. (2006). Consultaría educativa de noviembre 2006. [November 2006 educational consultation]. (Technical Report). Siguatepeque, Honduras: Comunidad Educativa Evangélica.

UNICEF. (2013). UNICEF Annual Report 2013-Honduras. http://www.unicef.org/about/annualreport/files/ Honduras_COAR_2013.pdf

This research project was financially supported by Latin America Mission Canada.

Latin America Mission Canada, Canada. estherbettney@gmail.com

A pseudonym has been used to maintain anonymity.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.