DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.12055Published:

2018-02-16Issue:

Vol 20, No 1 (2018) January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesPortuguese and spanish teletandem: the role of mediators

Teletandem portugués y español: el papel de los mediadores

Keywords:

lenguas próximas, Teletandem, papeles del mediador (es).Keywords:

Teletandem, close languages, mediation (en).References

ANDREU-FUNO, L. (2015). Teletandem: Um estudo sobre identidades culturais e sessões de mediação da aprendizagem. Tese de Doutorado. P.P.G. em Estudos Linguísticos, UNESP - Universidade Estadual Paulista.

ARANHA, S.; CAVALARI, S. M. S. (2014). A trajetória do projeto Teletandem Brasil: Da modalidade institucional não-integrada à institucional integrada. The ESPecialist, 35(2), 183-201.

BENEDETTI, A. M. Teletandem. In: MAYRINK, M. F.; ALBUQUERQUE-

COSTA, H. (Orgs.). (2013). Ensino e aprendizagem de línguas em ambientes virtuais. São Paulo: Humanitas, p.65-92.

CARVALHO, K. C H. P; MESSIAS, R. A. L. (2017). O teletandem no ensino e aprendizagem de espanhol/LE em contexto de formação inicial. Veredas (UFJF Online), in the press.

CARVALHO, K. C. H. P. de; MESSIAS, R. A. L.; DÍAS, A. M. (2015). Teletandem within the Context of closely-related languages: A Portuguese-Spanish interinstitutional experience. DELTA – Revista de Documentação e Estudos em Linguística Teórica e Aplicada, 31(3), 711-728.

CHARMAZ, K. (2009). A construção da teoria fundamentada: guia prático para análise qualitativa. Tradução de Joice Elias Costa. Porto Alegre: Artmed.

COSTA, L. M. G. (2015). Performatividade e gênero nas interações em teletandem. Tese de Doutorado. P.P.G. em Estudos Linguísticos, UNESP - Universidade Estadual Paulista.

GARCIA, D. N. M. (2015). A logística das sessões de interação e mediação no teletandem com vistas ao ensino/aprendizagem de línguas estrangeiras. Revista Estudos Linguísticos, v. 44, n.2, p. 725-738.

RAMOS, K. A. H. P. (2015). Interactants’ beliefs in teletandem: Implications for the teaching of Portuguese as a foreign language. DELTA – Revista de Documentação e Estudos em Linguística Teórica e Aplicada, 31(3), 691-709.

_____. (2013). Implicações socioculturais do processo de ensino de português para falantes de outras línguas no contexto virtual do Teletandem. Estudos Linguísticos, São Paulo, 42 (2): p. 731-742.

RAMOS, K. A. H. P.; CARVALHO, K. C. H. P.; MESSIAS, R. A. L. (2013). O ensino de português para hispanofalantes no contexto virtual do Teletandem. Portuguese Language Journal. Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Florida and the Latin American and Iberian Institute at the University of New Mexico, v.7, Fall, p. 1-23.

SALOMÃO, A. C. B. (2012). A cultura e o ensino de língua estrangeira: perspectivas para a formação continuada no projeto teletandem. Tese de Doutorado. P.P.G. em Estudos Linguisticos, UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista.

TELLES, J. A. (2015). Learning foreign languages in teletandem: Resources and strategies. DELTA – Revista de Estudos em Linguística Teórica e Aplicada, 31(3), 651-680.

TELLES, J. A. (Org.). (2009). Teletandem: um contexto virtual, autônomo e colaborativo para aprendizagem de línguas estrangeiras no século XXI. Campinas: Pontes.

TELLES, J. A.; VASSALO, M. L. (2009). Teletandem: uma proposta alternativa no ensino-aprendizagem assistidos por computadores. In: TELLES, J. A. (Org.). Teletandem: um contexto virtual, autônomo e colaborativo para aprendizagem de línguas estrangeiras no século XXI. Campinas: Pontes.

TELLES, J. A.; VASSALO, M. L. (2006). Foreign language learning in-tandem: Teletandem as an alternative proposal in CALLT. The ESPecialist,São Paulo (PUC), v. 27, n. 2, p. 189-212.

VIGOTSKI, L. S. (2007). A formação social da mente. Tradução de José Cipolla Neto. 7. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes.

_____. (1991). Pensamento e Linguagem. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1991.

ZAKIR, M. A. (2015). Cultura e(m) telecolaboração: Uma análise de parcerias de teletandem institucional. Tese de Doutorado. P.P.G. em Estudos Linguísticos, UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem: The Role of Mediators1

Teletandem Portugués y Español: El Papel de los Mediadores

Karin Adriane Henschel Pobbe Ramos2 Kelly Cristiane Henschel Pobbe de Carvalho3

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Ramos, K. A. H. P & Carvalho, K. C. H. P (2018). Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem: The Role of Mediators. Colomb. appl. linguist.j., 20(1), pp. 35-48.

Received: 23-May.-2017 / Accepted: 20-Dec.-2017 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.12055

Abstract

Teletandem is a virtual context of learning languages based on principles of autonomy and reciprocity in which two peers collaborate to learn the language of each other. Usually, the interactions occur in institutional groups mediated by a professor or a graduate student. This paper aims to describe the role of a mediator and the process of mediation in Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem. Previous studies have analyzed how the Teletandem practice in the context of very close languages, such as Portuguese and Spanish, presents some inherent specificity related to the natural possibility of certain intercommunication between the interactants (Ramos, Carvalho, & Messias, 2013; Silva-Oyama, 2010). In this case, it is necessary to observe the process of mediation more closely and consider the relevance of cultural and linguistic aspects. The theoretical assumptions that guide our description and discussion are based on sociocultural theory for second language learning and assume that the learning process happens through interactions between people and the environment in a cooperative manner (Vygotsky, 1978). The methodological perspective that anchors this study is grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006), which is based on a systematic collection of data that, after analysis, origínate concepts. The reflection corroborates the fact that the development of the process depends on the involvement of the mediator in different roles and suggests that the principles of autonomy and reciprocity are directly related to the mediation process and can contribute to an effective collaborative context of language learning.

Keywords: close languages, Teletandem, roles of mediator

Resumen

El Teletandem es un contexto virtual de aprendizaje de idiomas basado en los principios de autonomía y reciprocidad en el cual dos hablantes colaboran mutuamente a que aprendan sus lenguas maternas o sus idiomas de competencia. Usualmente, las interacciones ocurren en grupos institucionales mediados por un profesor o por un estudiante de postgrado. Este artículo tiene como objetivo describir el papel de los mediadores y el proceso de mediación en Teletandem portugués y español. Estudios previos han analizado que la práctica de Teletandem en el contexto de lenguas muy próximas, como el portugués y el español, presenta algunas especificidades inherentes a

1 This project received the support from Sao Paulo State üniversity (üNESP).

2 Sao Paulo State üniversity (ünesp), Brasil. karin.ramos1@gmail.com

3 Sao Paulo State üniversity (ünesp), Brasil. kellychpc@gmail.com

35

Colomb. Appl. Lingulst. J.

Prlnted ISSN 0123-4641 Online ISSN 2248-7085 • January - June 2018. Vol. 20 • Number 1 pp. 11-24.

la posibilidad natural de existir cierta intercomunicación entre los interactantes (Ramos, Carvalho, & Messias, 2013; Silva-Oyama, 2010). En este caso, es necesario observar más atentamente el proceso de mediación y considerar la relevancia de los aspectos culturales y lingüísticos. Los supuestos teóricos que guían nuestra descripción y discusión se basan en la teoría sociocultural para el aprendizaje de lenguas la cual asume que el proceso de aprendizaje ocurre a través de la interacción entre las personas y el medio ambiente en una relación de cooperación (Vygtosky, 1978). Por su vez, la perspectiva metodológica que ancla este estudio es la teoría fundamentada (Charmaz, 2006), basada en una recolección sistemática de datos que, tras analizados, originan conceptos. El análisis señala que el desarrollo del proceso depende de la participación del mediador en diferentes papeles y sugiere que los principios de autonomía y reciprocidad están directamente relacionados con el proceso de mediación y pueden contribuir a un contexto colaborativo efectivo de aprendizaje de idiomas.

Palabras clave: lenguas próximas, Teletandem, papeles del mediador

Introduction

Teletandem (Telles & Vassalo, 2006) is an inter-institutional collaborative project for learning foreign languages in which two students help each other learn their own languages or language of proficiency by using technological resources such as computers, webcams, and online communication tools, based on the principles of autonomy, reciprocity, and separation of languages. After ten years, the project was changed to attend to the new demands which resulted from its own development. In the first stage, there were no mediators assisting the interactants in the process, and the partnerships were independent, not in groups. At present, the interactions take place between groups of undergraduates, and mediators are included as part of the process. This paper aims to describe the actions that integrate and are resultant from the process of mediation and the roles of mediators in Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem based on the sociocultural theory for second language learning.

Previous studies have analyzed how the Teletandem practice in the context of very close languages, such as Portuguese and Spanish, present some inherent specificity related to the natural possibility of certain intercommunication between the interactants (Ramos, Carvalho, & Messias, 2013; Silva-Oyama, 2010). In this case, besides the general aspects also common to interactions in other languages that must be considered in the mediation process of Teletandem, it is necessary to pay closer attention to the role of the mediator during the supervision and conduction of the interactions to stimulate the interactants to develop intercultural and language awareness as noted below:

As far as very close languages, such as Portuguese and Spanish, are concerned, Teletandem practices can work provided that partners and partner institutions are committed to the process, there is knowledge of the languages, and monitoring is done by the mediators in order to stimulate a conscious attitude of the interactants towards difficulties and inabilities related to language use. Only this way may the virtual context of Teletandem become an environment of discursive practices that shall contribute to the development of autonomy, responsibility and engagement of the interactants leading them to a critical awareness of their language and their culture. (Ramos, Carvalho, & Messias, 2013, p. 19)

As the roles of mediators in Teletandem mediation are an important part of the foreign language learning process, a study on this issue may inform what the required actions in this context are. These attitudes may occur before, during, and after the sessions and will be described in terms of the mediation process and the interface between mediators and institutions; the mediation process and the interface among mediators; the mediation process and the interface between mediators and interactants; and the mediation process and very close languages implications, in this case, Portuguese and Spanish. Despite this description, this study does not seek to provide formulas for how to mediate Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem.

36

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical assumptions that guide the description and discussion in this paper are based on sociocultural theory for second language learning that assume that the learning process happens through interaction between people and the environment in a cooperative manner (Vygotsky, 1978). These principles allow us to understand the sociocognitive development of human beings and also ground recent trends of foreign language teaching: less artificial and more natural and human, more communicative and based on practical experiences in transcultural environments, including technological contexts as Teletandem.

Mediation in the language learning process has largely been studied, based on the writings of Vygotsky (1981, 1978), and suggests that human mental functioning is fundamentally a mediated process that is organized by cultural artifacts, activities, and concepts. Lantolf and Thorne (2006) describe the forms of mediation as follows: by regulation, which can be other-regulation and self-regulation (internalization); and by symbolic artefacts: mediating actions, planning and

controlling attention. By creation of auxiliary means of mediation, we are able to assess a situation and consider alternative courses of action and possible outcomes on the ideal or mental plane before acting on the concrete objective plane (Arievitch & van der Veer, 2004).

Kozulin classifies three major categories of mediation: mediation through material tools;

mediation through symbolic systems; and

mediation through another human being (Kozulin, 1990, 2003). Additionally, Donato and MacCormick (1994) point out that:

For Vygotsky, the source of mediation was either a material tool; a system of symbols, notably language; or the behavior of another human being in social interaction. Mediators, in the form of objects, symbols, and persons, transform natural, spontaneous impulses into higher mental processes, including strategic orientations to problem solving. (p. 456)

Nieto (2007) groups studies about mediation into three categories, named depending on whether the mediation was using a symbolic tool, especially language, or other human beings, or a material tool. The three categories are mediation by dialoguing with one self, mediation by dialoguing with the other, and mediation through technology.

The Teletandem language learning context involves, at the same time, material tools, symbolic systems, and another human being mediating the process, changing initially unfocused learning actions into communicative skills in the second language, and considering that the best way to achieve proficiency in all aspects of language use is by being exposed to the most varied types of social verbal interactions possible (Eun & Lim, 2009). The levels of these changes are based on how mediation is conducted and require, on the part of the mediator, a process of volition, choice, and capacity to adapt (Brown, 2002). For this reason, in this article, we discuss the roles of mediators in the interactions, considering not only mediation in its strictu sensu, but also in a broader sense that involves interfaces with institutions and other partners in the process.

Methodology

The methodological perspective that anchors this study is grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006), which is based on a systematic collection of data that, after analysis, originate reflections or concepts. This perspective starts from the data built through observations, interactions, and materials organized according to the objectives of the research. Based on this systematization, the experiences and empirical events are studied according to the analytical possibilities that emerge. For Charmaz (2006), the reflection culminates in a theoretical understanding of the experience studied.

Various methods were applied to collect data in Teletandem: transcriptions of the interaction sessions, transcriptions of the mediation session, and memos produced during our experience as mediators in a Teletandem partnership between a Brazilian university and Mexican university,

37

since 2013. In the Mexican context, Teletandem sessions occurred at the Mediateca installed in the Centro de Enseñanza de Lenguas Extranjeras (Foreign Language Teaching Center) of the university, which is a space for autonomous language learning designed for undergraduate and graduate students from several programs and also for the university’s employees. Learners were guided by language assessors to develop their learning process autonomously, considering their own methods and objectives.

In the Brazilian context, sessions occurred at the Laboratório de Teletandem (Teletandem Laboratory) with groups of students, mostly from the Language Arts Program, as an extracurricular activity to complement their education as teachers of Spanish.

Setting and Participants

The partnership focused on in this paper can be classified as an institutionally nonintegrated Teletandem modality (Aranha & Cavalari, 2014, p. 187), because the interactions are set between the institutions by the mediators, but they are not integrated into the regular program curricula of both contexts.

The organization of Teletandem activities is agreed between mediators, who are, in the case, a professor of Portuguese as a foreign language from the Mexican university and a professor of Spanish as a foreign language from the Brazilian university. The sessions are settled according to the availability of the groups and the institutions.

Teletandem: Instituting the mediation process

The initial proposal of the project (Telles & Vassalo, 2006) emerged as an initiative for democratization of access to foreign languages through establishment of partnerships between Brazilian undergraduate students and undergraduate students from foreign universities. The interactions among these students take place in a virtual context of collaborative and autonomous learning in which participants teach a language they know and, at the same time, learn the other’s language, by using chat and/or instant messaging tools (Telles & Vassalo, 2009). Some researchers define this context as a learning model, as we can see below:

It is the tandem language learning, a model of collaborative language learning that emerged in the end of last century, in its more recent version, Teletandem, which uses instant messaging applications for virtual contact among foreign language learners. (Benedetti, 2013, p. 66)

Recently, one of the aspects that started to be considered in the scope of research on Teletandem was the transcultural contact integrated in these interactions. Thus, in a new version of the project, Teletandem is redefined as:

A mode of telecollaboration—a virtual, collaborative and autonomous context for learning foreign languages in which two students help each other to learn their own languages (or language of proficiency). They do so by using the text, voice and webcam image resources of VOIP technology (such as Skype), and by adopting the three principles of tandem learning: autonomy, reciprocity, and separate use of both languages. (Telles, 2015, p. 652)

It is important to mention that the Teletandem teaching and learning process has always been based on the principles of autonomy and reciprocity shared by the interactants. It is not a simple chat between a bilingual pair; instead, “Teletandem interactants are interested in learning each other’s language through a distance learning process and in a relatively autonomous way” (Telles & Vassalo, 2006, p. 194).

Throughout the years, many changes have taken place concerning the form and consolidation of partnerships as well as the way sessions are conducted. In the beginning, interactions were independent and scheduled by the interactants themselves in an autonomous way, and there was no mediation process as it occurs after the establishment of group interactions. According to Aranha and Cavalari (2014), technology-mediated Teletandem emerges as a “way to promote foreign language learning and teaching through regular virtual meetings between two

38

speakers of different languages living in different countries” (p. 184). Nowadays, interactions

happen in groups, in laboratories from partner universities, during a schedule previously set by teachers or graduate students who act as mediators of the process, coordinating, organizing, and conducting the sessions. These changes require the establishment of a mediation process, and the way activities are conducted has to be considered, depending on whether or not the interactions integrate the schedule of regular classes and whether or not the activities are related to foreign language subjects.

When the interactions take place during classes as a part of the activities required in a language subject, they are called institutionally integrated Teletandem (Aranha & Cavalari, 2014). When the interactions are not required as activities of a language subject, they are called institutionally nonintegrated Teletandem. In some cases, Teletandem can be a voluntary practice, generally certified as complementary activities or counted as language laboratory exercises.

The organization of the mediation process has changed as new partnerships between other institutions and foreign universities have joined the project. Consequently, the objectives of this new format have been enlarged compared to the previous model, when partnerships were completely independent. On the one hand, this type of institutional modalities in groups was included to meet the demand from foreign universities interested in implementing Teletandem as a part of students’ regular activities in Portuguese lessons. On the other hand, this new configuration also meant, for Brazilian universities, the creation of a new environment outside the classroom for foreign language learning, where students not only find opportunities to be inserted in authentic contexts of communication but also share their experiences, which contributes to critical and reflexive learning.

Thus, the whole Teletandem process is constituted by interaction sessions and mediation sessions. During the interaction sessions, groups of students from two different universities, divided into pairs, learn each other’s language by using text, voice, and webcam image resources. Mediation sessions take place after each interaction session, when participants have the opportunity to report and share their experiences. In this context, mediators have to create strategies of intervention to trigger the teaching and learning process proposed by Teletandem. According to Telles (2015):

Mediation sessions are conducted by the teachers after each Teletandem session. They focus on aspects of the target languages, the students’ learning processes and the cultural aspects and themes that emerge (implicitly or explicitly) during the interactions. Mediation sessions can be conducted in either the native or target language, depending on the students’ level in the latter. The practice of conducting Teletandem mediation sessions requires knowledge about intercultural contact, discourse and communication. (p. 655)

However, the roles of mediators are not only restricted to supervising sessions, but they also develop different activities, such as researching, teaching, managing, supervising, etc. They can be professors, graduates, or undergraduate students who are a part of the Teletandem project and are responsible for organizing and supervising the interaction and mediation sessions in their multiple aspects, such as orientation of the use of technological tools, orientation of cultural and linguistic issues, and negotiation of partnerships.

Thus, mediation can be understood as a complex process with broader characteristics that, although including the mediation session in its restricted sense (cf. Telles, 2015, p. 655), does not imply that it is the only procedure involved. It is a whole process that is initiated with first contact with foreign institutions and extends to organization, monitoring, supervision, and evaluation.

According to Ramos (2013), the kind of control set up by this new configuration in a certain way has direct repercussions for the Teletandem principles of autonomy and reciprocity. However, without the presence of a mediator, as it occurs

39

in the independent modality, even though the interactants have much more autonomy, the levels of responsibility can vary according to partners’ characteristics, which can make the process less stable and less durable.

The following descriptions discuss the integrated actions of this mediation process and the roles of mediators, based on the interfaces imposed by this new context with groups’ interactions. This discussion is an attempt not only to systematize the process but especially to examine how Teletandem has been developed. The descriptions of interfaces are based on our experience as mediators in the partnership between a Brazilian university and a Mexican university and on the theoretical framework of mediation. The reflections emerged from the collected data analyzed according to the grounded theory principles.

Results

Interface Between Mediators and Institutions

The changes the project has been through in the latest years, already pointed out in this paper, have given institutions a very important role not only regarding logistic support for the development of the project but also as supporters and sponsors of the studies that discuss the specificities of this technological context of teaching and learning foreign languages.

To maintain these partnerships and establish new ones, the first step is to work to publicize the project, emphasize its contributions for the institutions involved, and explain the counterparts of each one in the process. The publicizing of the project has been undertaken in many ways, such as through the creation of an official website1, through participation in scientific events, through publications, technical vis its, and meetings of research groups2, and through explanatory materials available for those interested.

The process of establishing a partnership involves a long-term negotiation that includes exchanges of e-mails by the members in charge of the first contacts, rehearsal interaction sessions for demonstration, face-to-face and virtual meetings to explain the objectives of the project, and the actions required for its development.

The partnership between the universities in Brazil and Mexico is an outcome of this interface established between institutions by means of the contact and negotiation between mediators and professors from these universities, in a trajectory that has been consolidated since 2013. In both universities, there is the common objective of creating an institutional context to promote the teaching and learning of foreign languages, in this case, Portuguese and Spanish.

In an institutional partnership, mediators have the function of organizing, in their respective contexts, all the logistic aspects for the interactions (Garcia, 2015). These arrangements include setting the appointments at the laboratories of the institutions; checking the condition of the language laboratory equipment (computers, installation of application software, internet connection), as well as setting up a schedule for interaction sessions considering the number of meetings, number of interactants, dates and times, time zones, and daylight-saving time.

It is also necessary to count on the technical support of the employees of the institution and on trainees and monitors who assist with equipment maintenance and related tasks, such as installation of application software and recording programs. This help is essential, given that many unexpected situations may happen during the interactions.

As we can note, mediators must build this relationship not only between the institutions, but also inside them, considering that issues concerning teaching and learning languages are not always seen as a priority. Financial investments are needed to sponsor the project and recognize its value. Teletandem has been demonstrated to be an initiative that contributes to institutional visibility and allows the sharing of cultural experiences and scientific knowledge. For this reason, mediators must claim

40

an institutional status for the project by pointing out their importance for institutions themselves.

Interface Among Mediators

The relationship established among mediators is a fundamental part of the Teletandem language teaching and learning process. Because the Brazilian institution maintains several partnerships with different universities3, there is a group of mediators who are responsible for intermediating partnerships, according to the languages and the availabilities of the schedules, generally established by the foreign institutions.

In this paper, we focus on the mediation process that occurs in the partnership between two universities in Brazil and Mexico due to our interest in the process of learning Spanish and teaching Portuguese, both as foreign languages. Thus, since the beginning of the first negotiations (related to the logistics aspects of the interactions), constant communication with the Mexican mediator was developed to discuss the groups’ needs and characteristics, considering the interactants’ learning objectives as well as their language levels and intercultural issues involved in the process.

The interactants’ objectives were very distinct. On the one hand, Brazilian students looked for Teletandem to improve their foreign language proficiency and to enlarge their intercultural experiences, since they are involved in a context of pre-service Spanish teachers’ development; on the other hand, Mexican students wanted to learn Portuguese to take internships, participate in exchange programs, and attend postgraduate courses in Brazil, or even to train for official exams of language proficiency.

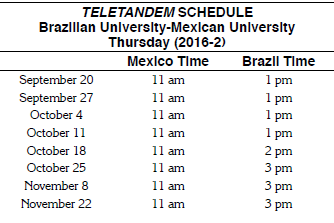

Because the partnership is inserted in an institutionally nonintegrated Teletandem modality in both contexts, Brazil and Mexico, it was necessary to consider the specificities related to a larger flexibility and participation of the interactants who had to, for instance, adapt to the changes of schedule during the semester. Therefore, the interface among mediators is extremely relevant because, many times, some adjustments and concessions are required. An example of this is illustrated in the following chart, which shows that the Brazilian group went through several changes of interaction schedule throughout the second semester of 2016 to adapt it to the needs of the Mexican students. This resulted from facts related to the availability of the laboratory and other activities at the Mediateca, and also from variation of daylight saving time schedules. While Mexican groups maintained the same schedule, Brazilian groups started the interactions at 1 pm, then at 2 pm, and finally 3 pm. This means that when Brazilian students commit themselves to the process, they are committing almost the whole afternoon during the semester.

TELETANDEM SCHEDULE Brazilian University-Mexican University

_Thursday (2016-2)_

Mexico Time Brazil Time

|

September 20 |

11 am |

1 pm |

|

September 27 |

11 am |

1 pm |

|

October 4 |

11 am |

1 pm |

|

October 11 |

11 am |

1 pm |

|

October 18 |

11 am |

2 pm |

|

October 25 |

11 am |

3 pm |

|

November 8 |

11 am |

3 pm |

|

November 22 |

11 am |

3 pm |

Figure 1. Teletandem sessions example schedule.

For this reason, another aspect to be considered is the necessity of establishing a relationship of cooperation among mediators. Many times, throughout the process, new situations emerge and demand adjustments that are implied in decision-making. It is important to emphasize that those decisions must be made together. Thus, mediators have to maintain an open channel for communication so that problems may be solved and possible occurrences may be foreseen.

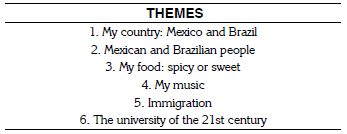

Mediators may also choose themes to be discussed during interactions. These themes aim to deepen students’ knowledge of issues related to linguistic, discursive, and intercultural aspects so that exchanges among interactants overtake the

41

limits of a simple chat about daily matters. These topics generally emerge in the first interactions in which interactants build a bond. However, the selection of themes motivates students to search contents related to the proposed issues as well as to prepare activities to be used in the session. The following chart shows a list of the themes that were chosen for the interactions in the second semester of 2016 with the purpose of deepening intercultural issues.

_THEMES_

1. My country: Mexico and Brazil

2. Mexican and Brazilian people

3. My food: spicy or sweet

4. My music

5. Immigration

6. The university of the 21st century

Figure 2. Example themes discussed in Teletandem sessions.

One point that must be highlighted about the project is that the context is the field of research, and for this reason, a lot of mediators also develop studies examining the process of teaching and learning foreign languages. Then, interactions and the process of mediation become objects of their academic papers. We have noticed that when mediators are involved in research about Teletandem, partnerships tend to be longer and be more intense. This attitude can be found in the partnership studied in this paper once its mediators are involved in research activities that have even resulted in a co-authorship scientific publication (Carvalho, Messias, & Días, 2015).

Interface Between Mediators and Interactants

As an institutionally nonintegrated Teletandem, in the partnership between the Brazilian university and the Mexican university, interactions are optional in both contexts. Consequently, we can say that the bond described in this paper is guided by a principle that emphasizes interactants’ autonomy, since they are the ones who decide whether or not to participate, according to their interests.

For this reason, various aspects must be pointed out in the interface between mediators and interactants, considering not only the operation of interactions but also mainly the strengthening of actions. In this context, the responsibility of the mediator covers phases that extend from the publication of the availability of vacancies to consultancy during and after the sessions, especially regarding the definition of specific learning objectives and the development of autonomy in the process by the interactants.

To create the groups, mediators first open enrollment in each institution, considering the vacancies available, the schedule, and number of sessions previously agreed upon and scheduled at the laboratories of each institution. Then, they make arrangements to publicize the vacancies through different means, such as through social networks, e-mail lists, and posters for interested students to enable them to register. Finally, they make the lists of interactants and match the partners. In this process, it is very important to note that, besides the vacancy announcement, it is the mediator who intervenes in the process of stimulating participation as well as making students aware of the level of commitment involved in the activities of the project regarding attendance, punctuality, etc. In a focused partnership, eight meetings are settled each semester. These interaction sessions take place once a week, last one hour, and are succeeded by mediation sessions with discussions that last approximately forty minutes.

Before the interactions begin, it is necessary to prepare interactants by giving them some pertinent previous information. It is the orientation session that, according to Telles (2015), focuses “on what tandem learning is about and its principles— autonomy, reciprocity, and nonmixture of languages. Basic language learning strategies and ways of behaving for learning foreign languages are also presented to the students by the teacher” (p. 655).

Therefore, the orientations include both technical questions and information about the structure, operation, and objectives of Teletandem

42

interactions. At this moment, a list of themes can also be suggested to the interactants, considering the agreements made by the mediators. It is important to mention that, in the beginning, themes are only suggested and that, throughout the interactions, the mediator can intervene indicating that participants should define their choices with their partners, according to the specificities and interests of each. That can advance the development of the Teletandem principles of autonomy and reciprocity.

During the interactions, mediators conduct the sessions, supporting and controlling the pairing; they give instructions on the use of Skype and its respective tools, such as screen sharing, virtual dictionaries, and writing tools to register the conversation and check spellings. They also verify the operation of computers and indicate the moment the interactants must change the use of languages so that both can enjoy positive outcomes from the interaction. Concerning the last aspect, according to other studies, it is important to observe that the first half of the session is generally more productive. Thus, it is convenient to indicate the alternation of languages to start the sessions, and it is the mediator who has to pay attention to this orientation. Warning each student about the importance of attending the scheduled sessions and accomplishing the timetable is also the duty of the mediator.

After the interaction session, the mediation session occurs, as was pointed out before. In this case, we noticed that the mediator’s intervention is extremely necessary and, at this point, the preference for a language teacher to intermedíate the process becomes more evident. From being an authentic context of communication, Teletandem can easily become a “simple chat,” and students’ learning objectives can end up diluted during the conversation. Although, on the one hand, this “simple chat” can itself promote language learning, according to the sociocultural perspective of language, on the other hand, if specific learning goals for Teletandem are set up and followed by the students, this context can become much more effective.

This is the mediator’s role-the one who can, at this time and place, intervene by stimulating reflection and raising awareness on the part of the interactants of the need to set specific learning goals, whether related to linguistic contents, such as grammar and vocabulary, or related to intercultural aspects, such as social practices and behaviors, or related to the strategies of teaching and learning languages and strategies to overcome the difficulties agreed between the partners. At this point, we reiterate the importance of Teletandem as a context of reflection upon the process of teaching and learning languages and, therefore, as a unique experience in teachers’ training:

We believe that institutional Teletandem represents, for language teaching education programs, a context where students dialog with knowledge of their interlocutors and also with their own knowledges. It is a scenario which enables reflections that potentialize and help to build empirical, theoretical and methodological knowledges that are important to strengthen their teacher’s identity, in this case of Spanish as a foreign language. (Carvalho & Messias, 2017)

In relation to intercultural issues, given to the specificity of Teletandem, it is also fundamental to conduct reflection in a way that differences and social comparisons may indeed cooperate for the comprehension of other cultures and not reinforce prejudice based on stereotypes. Discussion of the cultural issues that emerge in Teletandem can be found in many recently publications, such as Zakir (2015), Costa (2015), Andreu-Funo (2015), and Salomao (2012). The following Teletandem dialog, where interactants discuss how to eat avocado, illustrates the way these comparisons easily occur. The mediator can also pay attention to them to stimulate intercultural learning:

Mexican interactant: And do you know anything about Mexico?

Brazilian interactant: About Mexico...

Mexican interactant: Do you know Mexico? Brazilian interactant: Let me see... you guys eat avocado with salt

43

Mexican interactant: Yes... avocado is very tasty [rico]

Brazilian interactant: No... Here we eat with sugar Mexican interactant: Yes [sí]

Brazilian interactant: Not with salt

Mexican interactant: No... I would never eat with

sugar

Brazilian interactant: But here we/ wow it’s

delicious with sugar... I’ve never tasted with

salt... but it’s delicious with sugar

Mexican interactant: I’ll taste it

Brazilian interactant: Here we make avocado

juice... sweet... but nothing salty

Mexican interactant: I’ll taste avocado with sugar

Brazilian interactant: I’ll taste with salt then... just

to get to know... how it tastes4 5

(Interaction Session)

During the interactions described here, the mediator can also intervene by creating and managing activities or tasks throughout the development of the interaction sessions. These procedures contribute to potentialize learning. It is common for interactants to keep diaries, which are shared and can contribute not only as research data but also as instruments for the mediator to better evaluate the entire process, consider its implications for teaching and learning languages, and predict possible difficulties. Besides the production of diaries, it has also been a practice of mediators to stimulate exchanges of pieces of writing between interactants for peer correction. It would help to understand if “other partnerships” were introduced and contextualized earlier.

One of the principles of Teletandem is not to mix languages. For this reason, in an interaction session, the time of each language must be equally divided. This practical principle tends to promote students’ commitment with the task and with the learning process (Telles, 2009, p. 24), and it is important to build a non-hegemonic relationship between languages.

However, in the case of interactions in Portuguese and Spanish, we have noticed that it is very common that languages sometimes interflow because of their closeness and relative possibility of mutual intelligibility. When this occurs in a way such that differences are contrasted, it can contribute to learning according to Benedetti (2013):

Although the mixture of languages may break one of the tandem principles of learning, i.e., the separate use of languages in focus, the confrontation between languages/cultures during dialogical communication can contribute significantly for the understanding not only of the language system but also of the values that permeate meanings in this language in contrast with the other. (p. 80)

This situation can be observed, for example, in the following dialog, in which the Brazilian student states that after being corrected by his partner, he could understand the appropriate use of pronouns of treatment in Spanish in contrast with their use in Portuguese.

Mediator: And could you talk more, compared to last week?

Brazilian interactant: Yes, last week I was making a confusion because I started to mix Portuguese and Spanish... I think I was a bit nervous and began to mix Portuguese and Spanish. so I was. because usted for them is a formal treatment, isn’t it? So every time I couldn’t speak tú, I spoke usted and then he corrected me, because it would be like if I was saying Mister and so on. ... Then today I said tú,

44

and then he told me I spoke better... I could talk more.5

(Mediation session)

However, when this situation does not occur, the intervention of the mediators in monitoring and supervision of interactions is needed to avoid language fossilization and the false feeling of full communicative competence. This feeling is very common when Portuguese speakers learn Spanish or Spanish speakers learn Portuguese. In this way we can show that groups’ institutional modality of Teletandem has demanded a type of monitoring, according to what we have been discussing:

In the case of Portuguese/Spanish interaction, the bounders between the languages. are not always evident, especially when the learners are beginners. This way, we believe... that the presence and supervision of a mediator teacher are important so that participants get better results from the process. The mediator teacher can, while monitoring, observe and evaluate the interactions and, by doing so, interfere to help the students notice these occurrences as well as their own and their partners’ interlanguage signs. (Ramos, Carvalho, & Messias, 2013, p. 17)

This aspect has been the great difference in this Teletandem modality, especially in Portuguese and Spanish interactions, which, because of their singularity, allow some degree of mutual intelligibility between partners. The following dialog is an example of how, during a mediation session, mediators can intervene based on what interactants say about mixing languages. It can be noticed that the Brazilian interactant uses only Portuguese and the Mexican interactant uses only Spanish. In such situations, there is no second language learning process.

8 Mediadora: E vocé conseguiu falar mais em rela^áo a semana passada?

Interagente brasileiro: Sim, na semana passada, eu tava fazendo muita confusao porque eu comecei a misturar portugués, eu acho que estava meio nervosa e comecei a misturar portugués com espanhol, entao eu tava... porque usted pra eles é como um tratamento formal, né? Entáo a todo momento eu náo conseguía falar o tú, eu falava o usted e daí ele me corrigiu, porque seria como se eu estivesse falando senhor né e tal. Daí hoje eu já falei o tú, daí ele até falou que eu falei melhor, consegui falar mais.

Mediator 3: And in what language did you start, Portuguese or Spanish?

Mediator 1: Did you only speak Spanish?

Brazilian Interactant: Well, it’s like this... I asked in Portuguese and then she answered in Spanish.

After she asked me in Spanish and I answered in Portuguese.

Mediator 3: You have to define!

Mediator2: Ouch... the ideal is that you define... that you define, even if it turns into Portunhol in the beginning... but you can say: now it’s Portuguese.

[■■■]

Mediator 2: And you both should control Mediator 1: And neither you nor she can make progress. because she needs to speak Portuguese and to listen Portuguese and you need to speak Spanish and to listen Spanish. right? But always keeping this communication. first one language after the other language6 (Mediation session)

Considering the possibility of mutual intelligibility, interactants feel comfortable using their mother tongue. The intervention of mediators here is essential for partners to feel challenged to take risks in the foreign language according to the principles and objectives established for learning in the Teletandem context.

In a situation where differences are not always noticeable, it is the mediator, in this case, a teacher of Spanish as a foreign language and a teacher of

45

Portuguese as a foreign language, who can indicate, based on observation in monitoring and supervising the interactions, possible difficulties and strategies to overcome them.

Although Teletandem interactions can be guided by distinct objectives, it is necessary to consider the specificity of the partnership focused on in this study, in which there are, on the one hand, learners of Spanish in a context of preservice teachers and, on the other, learners of Portuguese for working purposes. It is necessary to carefully pay attention to these facts to promote the proficiency and linguistic competence required.

Even though, at first, we can accept some interlanguage occurrence (as a natural result of this process), it is necessary to know that it is one thing to recognize its existence; another, very different, is to help students to take on the study of Portuguese as a foreign language and of Spanish as a foreign language in order to overcome it and not be satisfied with the possibility of attending only primary communication needs by speaking a Portunhol, which is, in general, far from any usual expression in the target language. (Ramos, Carvalho, & Messias, 2013, p. 18)

Conclusions

In this article, we aimed at explaining the Teletandem mediation process and the roles of mediators, understood in a broader sense, based on a partnership between two universities in Brazil and Mexico. To reach this objective, we systematized the analysis grounded on established relationships and on the roles of mediators in the development of the process, which are as follows: the interface between mediators and institutions; the interface among mediators; the interface between mediators and interactants; and, finally, Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem mediation.

The results show that the Teletandem mediation process is intrinsically related to the mediators’ involvement in different procedures, which begin with the first negotiation, continue through the organization and supervision, and culminate in evaluation, through cyclical, constant, and, sometimes, simultaneous movements.

As we observed, the importance of understanding the mediation process as a whole is essential for the development of institutional Teletandem interactions in groups. Therefore, the implementation of Teletandem should start with a mediator, motivated by the desire to promote an interactive, intercultural, and technological context that corroborates a social interactionist conception of teaching and learning languages. From this perspective, the mediator must necessarily be committed to the institutions, the mediator partner, and the group of interactants.

As far as close languages are concerned, we emphasize the importance of the mediation process regarding the attention given to the linguistic discursive aspects that emerge in this specific context, especially when we intend that students become able to identify the differences between very close languages to achieve linguistic proficiency in both of them. In this sense, Teletandem mediation is essential to monitor the interactants’ development, aiming at critical awareness, perception, and reflection, not only on linguistic reality but also on intercultural aspects. For this reason, further inter-institutional partnerships and research are necessary.

As pointed before, the Teletandem language learning context involves, at the same time, material tools, symbolic systems, and another human being mediating the process, which changes initially unfocused learning actions into communicative skills in the second language. Students have the opportunity to use the language by being exposed to varied types of social verbal interactions.

Thus, even restricted to a specific case, we believe that the path we outlined in our discussion, in its more general aspects, can support or guide other experiences. Further experiences may be related to the improvement and implementation of Teletandem practices in other educational environments to establish new partnerships and, consequently, reinforce the project.

46

References

Andreu-Funo, L. (2015). Teletandem: Um estudo sobre identidades culturais e sessoes de mediagao da aprendizagem. Tese de Doutorado. PPG. em Estudos Linguísticos, ÜNESP: Üniversidade Estadual Paulista.

Aranha, S., & Cavalari, S. M. S. (2014). A trajetória do projeto Teletandem Brasil: Da modalidade institucional nao-integrada a institucional integrada. The ESPecialist, 35(2), 183-201.

Arievitch, I., & van der Veer, R. (2004). The role of nonautomatic process in activity regulation: From Lipps to Galperin. History of Psychology, 7, 154-182.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1093-4510.7.2.154

Benedetti, A. M. (2013). Teletandem. In M. F. Mayrink & H. Albuquerque-Costa (Eds.), Ensino e aprendizagem de línguas em ambientes virtuais (pp. 65-92). Sao Paulo: Humanitas.

Brown, D. N. (2002). Mediated learning and foreign language acquisition. ASp, 35-36, 1-17.

https://doi.org/10.4000/asp. 1651

Carvalho, K. CH. P, & Messias, R. A. L. (2017). O Teletandem no ensino e aprendizagem de espanhol/ LE em contexto de formagao inicial. Veredas (ÜFJF Online), 21(1), 60-74.

Carvalho, K. C. H. P, Messias, R. A. L., & Días, A. M. (2015). Teletandem within the context of closely-related languages: A Portuguese-Spanish interinstitutional experience. DELTA - Revista de Documentagao e Estudos em Linguística Teórica e Aplicada, 31(3), 711-728.

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-445073456257282854

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: SAGE.

Costa, L. M. G. (2015). Performatividade e genero nas interagóes em Teletandem. Tese de Doutorado. PPG. em Estudos Linguísticos, ÜNESP: Üniversidade Estadual Paulista.

Donato, R., & MacCormick, D. A. (1994). Sociocultural perspective on language learning strategies: The role of mediation. The Modern Language Journal, 78(4), 453-464.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1540-4781.1994.tb02063.x

Eun, B., & Lim, H. S. (2009). A sociocultural view of language learning: the importance of meaning-based instruction. TESL Canada Journal/Revue TESL du Canada, 27(1), 13-26.

https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v27i1.1031

Garcia, D. N. M. (2015). A logística das sessóes de interagao e mediagao no Teletandem com vistas ao ensino/ aprendizagem de línguas estrangeiras. Revista Estudos Linguísticos, v. 44(2), 725-738.

Kozulin, A. (1990). Vygotsky’s psychology: A biography of ideas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Üniversity Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511840975

https://doi.org/10.1017/CB09780511840975.003

Kozulin, A. (2003). Psychological tools and mediated learning. In A. Kozulin, B. Gindis, V. S. Ageyev, & S. M. Miller (Eds.) Vygotsky’s educational theory in cultural context (pp. 15-38). Cambridge, ÜK: Cambridge Üniversity Press.

Lantolf, J. P, & Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural theory and second language learning. In: B. VanPatten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition (pp. 197-221). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Nieto, C. H. G. (2007). Applications of Vygotskyan concept of mediation in SLA. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 9, 213-228.

Ramos, K. A. H. P (2013). Implicagóes socioculturais do processo de ensino de portugues para falantes de outras línguas no contexto virtual do Teletandem. Estudos Linguísticos, 42(2), 731-742.

Ramos, K. A. H. P, Carvalho, K. C. H. P, & Messias, R. A. L. (2013). O ensino de portugués para hispanofalantes no contexto virtual do Teletandem. Portuguese Language Journal, 7, 1-23.

Salomao, A. C. B. (2012). A cultura e o ensino de língua estrangeira: perspectivas para a formagao continuada no projeto Teletandem. Tese de Doutorado. PPG. em Estudos Linguísticos, ÜNESP: Üniversidade Estadual Paulista.

Silva-Oyama, A. C. (2010) Estratégias de comunicagao na aprendizagem de portugues/espanhol por Teletandem. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 10(1), 89-112.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-63982010000100006

Telles, J. A. (Ed.). (2009). Teletandem: Um contexto virtual, autónomo e colaborativopara aprendizagem de línguas estrangeiras no século XXI. Campinas: Pontes.

Telles, J. A. (2015). Learning foreign languages in Teletandem: Resources and strategies. DELTA: Revista de Estudos em Linguística Teórica e Aplicada, 31(3), 651-680.

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4450226475643730772

47

Telles, J. A., & Vassalo, M. L. (2006). Foreign language learning in-tandem: Teletandem as an alternative proposal in CALLT. The ESPecialist, 27(2), 189-212.

Telles, J. A., & Vassalo, M. L. (2009). Teletandem: Üma proposta alternativa no ensino-aprendizagem assistidos por computadores. In J. A. Telles (Ed.), Teletandem: um contexto virtual, autónomo e colaborativo para aprendizagem de línguas estrangeiras no século XXI (pp.43-61). Campinas: Pontes.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Üniversity Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1981). The genesis of higher mental functions. In J. Wertsch (Ed.), The concept of activity in Soviet psychology (pp.M4-188). Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Zakir, M. A. (2015). Cultura e(m) telecolaboragao: Uma análise de parcerias de Teletandem institucional. Tese de Doutorado. PPG. em Estudos Linguísticos, ÜNESP: Üniversidade Estadual Paulista.

48

http://www.teletandembrasil.org/

http://dgp.cnpq.br/dgp/espelhogrupo/2209139477462677: Teletandem: Transculturality in Online Communication in Foreign Languages by Webcam.

At present, this Brazilian university maintains partnerships with about 10 universities abroad, such as Georgetown üniversity, Harvard üniversity, Miami University, Princeton University, and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

M: E vocé sabe algo do México?

B: Do México

M: Vocé conhece o México?

B: Vamo vé... que vocés comem abacate com sal M: Ah... abacate muito rico B: Nao aqui a gente come com adúcar M: Sí

B: Com sal nao

M: Nao... eu nao comeria com adúcar B: Mas aqui a gen/ nossa é uma delicia com adúcar... nunca provei com sal... mas é uma delicia com adúcar M: Vou provar

B: A gente aqui faz suco com abacate... doce... agora salgado nada

M: Eu vou provar abacate com adúcar

B: Eu vou provar com sal entao... pra ver... como é que fica

Mediador 3: E em que língua vocé come^ou, em portugués ou espanhol?

Mediador 1: Só falou em espanhol?

Interagente brasileiro: É que é assim, eu perguntava em portugués aí ela respondia em espanhol, aí depois ela perguntava em espanhol e eu respondia em portugués.

Mediador 3: Tem que definir!

Mediador 2: Ai, o ideal é que vocé defina, que vocé defina nem que vire um portunhol no cometo, mas vocé pode falar, agora é o portugués.

Mediador 2: E vocés controlam.

Mediador 1: Nao há um aproveitamento seu nem dela. Porque ela precisa falar portugués e ouvir portugués e vocé precisa falar o espanhol e ouvir o espanhol. Certo? Mas mantendo sempre esta comunicado. üma língua e depois outra língua...

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem: The Role of Mediators1

Teletandem Portugués y Español: El Papel de los Mediadores

Karin Adriane Henschel Pobbe Ramos2 Kelly Cristiane Henschel Pobbe de Carvalho3

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Ramos, K. A. H. P & Carvalho, K. C. H. P (2018). Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem: The Role of Mediators. Colomb. appl. linguist.j., 20(1), pp. 35-48.

Received: 23-May.-2017 / Accepted: 20-Dec.-2017 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.12055

Abstract

Teletandem is a virtual context of learning languages based on principles of autonomy and reciprocity in which two peers collaborate to learn the language of each other. Usually, the interactions occur in institutional groups mediated by a professor or a graduate student. This paper aims to describe the role of a mediator and the process of mediation in Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem. Previous studies have analyzed how the Teletandem practice in the context of very close languages, such as Portuguese and Spanish, presents some inherent specificity related to the natural possibility of certain intercommunication between the interactants (Ramos, Carvalho, & Messias, 2013; Silva-Oyama, 2010). In this case, it is necessary to observe the process of mediation more closely and consider the relevance of cultural and linguistic aspects. The theoretical assumptions that guide our description and discussion are based on sociocultural theory for second language learning and assume that the learning process happens through interactions between people and the environment in a cooperative manner (Vygotsky, 1978). The methodological perspective that anchors this study is grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006), which is based on a systematic collection of data that, after analysis, origínate concepts. The reflection corroborates the fact that the development of the process depends on the involvement of the mediator in different roles and suggests that the principles of autonomy and reciprocity are directly related to the mediation process and can contribute to an effective collaborative context of language learning.

Keywords: close languages, Teletandem, roles of mediator

Resumen

El Teletandem es un contexto virtual de aprendizaje de idiomas basado en los principios de autonomía y reciprocidad en el cual dos hablantes colaboran mutuamente a que aprendan sus lenguas maternas o sus idiomas de competencia. Usualmente, las interacciones ocurren en grupos institucionales mediados por un profesor o por un estudiante de postgrado. Este artículo tiene como objetivo describir el papel de los mediadores y el proceso de mediación en Teletandem portugués y español. Estudios previos han analizado que la práctica de Teletandem en el contexto de lenguas muy próximas, como el portugués y el español, presenta algunas especificidades inherentes a

1 This project received the support from Sao Paulo State üniversity (üNESP).

2 Sao Paulo State üniversity (ünesp), Brasil. karin.ramos1@gmail.com

3 Sao Paulo State üniversity (ünesp), Brasil. kellychpc@gmail.com

35

Colomb. Appl. Lingulst. J.

Prlnted ISSN 0123-4641 Online ISSN 2248-7085 • January - June 2018. Vol. 20 • Number 1 pp. 11-24.

la posibilidad natural de existir cierta intercomunicación entre los interactantes (Ramos, Carvalho, & Messias, 2013; Silva-Oyama, 2010). En este caso, es necesario observar más atentamente el proceso de mediación y considerar la relevancia de los aspectos culturales y lingüísticos. Los supuestos teóricos que guían nuestra descripción y discusión se basan en la teoría sociocultural para el aprendizaje de lenguas la cual asume que el proceso de aprendizaje ocurre a través de la interacción entre las personas y el medio ambiente en una relación de cooperación (Vygtosky, 1978). Por su vez, la perspectiva metodológica que ancla este estudio es la teoría fundamentada (Charmaz, 2006), basada en una recolección sistemática de datos que, tras analizados, originan conceptos. El análisis señala que el desarrollo del proceso depende de la participación del mediador en diferentes papeles y sugiere que los principios de autonomía y reciprocidad están directamente relacionados con el proceso de mediación y pueden contribuir a un contexto colaborativo efectivo de aprendizaje de idiomas.

Palabras clave: lenguas próximas, Teletandem, papeles del mediador

Introduction

Teletandem (Telles & Vassalo, 2006) is an inter-institutional collaborative project for learning foreign languages in which two students help each other learn their own languages or language of proficiency by using technological resources such as computers, webcams, and online communication tools, based on the principles of autonomy, reciprocity, and separation of languages. After ten years, the project was changed to attend to the new demands which resulted from its own development. In the first stage, there were no mediators assisting the interactants in the process, and the partnerships were independent, not in groups. At present, the interactions take place between groups of undergraduates, and mediators are included as part of the process. This paper aims to describe the actions that integrate and are resultant from the process of mediation and the roles of mediators in Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem based on the sociocultural theory for second language learning.

Previous studies have analyzed how the Teletandem practice in the context of very close languages, such as Portuguese and Spanish, present some inherent specificity related to the natural possibility of certain intercommunication between the interactants (Ramos, Carvalho, & Messias, 2013; Silva-Oyama, 2010). In this case, besides the general aspects also common to interactions in other languages that must be considered in the mediation process of Teletandem, it is necessary to pay closer attention to the role of the mediator during the supervision and conduction of the interactions to stimulate the interactants to develop intercultural and language awareness as noted below:

As far as very close languages, such as Portuguese and Spanish, are concerned, Teletandem practices can work provided that partners and partner institutions are committed to the process, there is knowledge of the languages, and monitoring is done by the mediators in order to stimulate a conscious attitude of the interactants towards difficulties and inabilities related to language use. Only this way may the virtual context of Teletandem become an environment of discursive practices that shall contribute to the development of autonomy, responsibility and engagement of the interactants leading them to a critical awareness of their language and their culture. (Ramos, Carvalho, & Messias, 2013, p. 19)

As the roles of mediators in Teletandem mediation are an important part of the foreign language learning process, a study on this issue may inform what the required actions in this context are. These attitudes may occur before, during, and after the sessions and will be described in terms of the mediation process and the interface between mediators and institutions; the mediation process and the interface among mediators; the mediation process and the interface between mediators and interactants; and the mediation process and very close languages implications, in this case, Portuguese and Spanish. Despite this description, this study does not seek to provide formulas for how to mediate Portuguese and Spanish Teletandem.

36

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical assumptions that guide the description and discussion in this paper are based on sociocultural theory for second language learning that assume that the learning process happens through interaction between people and the environment in a cooperative manner (Vygotsky, 1978). These principles allow us to understand the sociocognitive development of human beings and also ground recent trends of foreign language teaching: less artificial and more natural and human, more communicative and based on practical experiences in transcultural environments, including technological contexts as Teletandem.

Mediation in the language learning process has largely been studied, based on the writings of Vygotsky (1981, 1978), and suggests that human mental functioning is fundamentally a mediated process that is organized by cultural artifacts, activities, and concepts. Lantolf and Thorne (2006) describe the forms of mediation as follows: by regulation, which can be other-regulation and self-regulation (internalization); and by symbolic artefacts: mediating actions, planning and

controlling attention. By creation of auxiliary means of mediation, we are able to assess a situation and consider alternative courses of action and possible outcomes on the ideal or mental plane before acting on the concrete objective plane (Arievitch & van der Veer, 2004).

Kozulin classifies three major categories of mediation: mediation through material tools;

mediation through symbolic systems; and

mediation through another human being (Kozulin, 1990, 2003). Additionally, Donato and MacCormick (1994) point out that:

For Vygotsky, the source of mediation was either a material tool; a system of symbols, notably language; or the behavior of another human being in social interaction. Mediators, in the form of objects, symbols, and persons, transform natural, spontaneous impulses into higher mental processes, including strategic orientations to problem solving. (p. 456)

Nieto (2007) groups studies about mediation into three categories, named depending on whether the mediation was using a symbolic tool, especially language, or other human beings, or a material tool. The three categories are mediation by dialoguing with one self, mediation by dialoguing with the other, and mediation through technology.

The Teletandem language learning context involves, at the same time, material tools, symbolic systems, and another human being mediating the process, changing initially unfocused learning actions into communicative skills in the second language, and considering that the best way to achieve proficiency in all aspects of language use is by being exposed to the most varied types of social verbal interactions possible (Eun & Lim, 2009). The levels of these changes are based on how mediation is conducted and require, on the part of the mediator, a process of volition, choice, and capacity to adapt (Brown, 2002). For this reason, in this article, we discuss the roles of mediators in the interactions, considering not only mediation in its strictu sensu, but also in a broader sense that involves interfaces with institutions and other partners in the process.

Methodology

The methodological perspective that anchors this study is grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006), which is based on a systematic collection of data that, after analysis, originate reflections or concepts. This perspective starts from the data built through observations, interactions, and materials organized according to the objectives of the research. Based on this systematization, the experiences and empirical events are studied according to the analytical possibilities that emerge. For Charmaz (2006), the reflection culminates in a theoretical understanding of the experience studied.

Various methods were applied to collect data in Teletandem: transcriptions of the interaction sessions, transcriptions of the mediation session, and memos produced during our experience as mediators in a Teletandem partnership between a Brazilian university and Mexican university,

37

since 2013. In the Mexican context, Teletandem sessions occurred at the Mediateca installed in the Centro de Enseñanza de Lenguas Extranjeras (Foreign Language Teaching Center) of the university, which is a space for autonomous language learning designed for undergraduate and graduate students from several programs and also for the university’s employees. Learners were guided by language assessors to develop their learning process autonomously, considering their own methods and objectives.

In the Brazilian context, sessions occurred at the Laboratório de Teletandem (Teletandem Laboratory) with groups of students, mostly from the Language Arts Program, as an extracurricular activity to complement their education as teachers of Spanish.

Setting and Participants

The partnership focused on in this paper can be classified as an institutionally nonintegrated Teletandem modality (Aranha & Cavalari, 2014, p. 187), because the interactions are set between the institutions by the mediators, but they are not integrated into the regular program curricula of both contexts.

The organization of Teletandem activities is agreed between mediators, who are, in the case, a professor of Portuguese as a foreign language from the Mexican university and a professor of Spanish as a foreign language from the Brazilian university. The sessions are settled according to the availability of the groups and the institutions.

Teletandem: Instituting the mediation process

The initial proposal of the project (Telles & Vassalo, 2006) emerged as an initiative for democratization of access to foreign languages through establishment of partnerships between Brazilian undergraduate students and undergraduate students from foreign universities. The interactions among these students take place in a virtual context of collaborative and autonomous learning in which participants teach a language they know and, at the same time, learn the other’s language, by using chat and/or instant messaging tools (Telles & Vassalo, 2009). Some researchers define this context as a learning model, as we can see below:

It is the tandem language learning, a model of collaborative language learning that emerged in the end of last century, in its more recent version, Teletandem, which uses instant messaging applications for virtual contact among foreign language learners. (Benedetti, 2013, p. 66)

Recently, one of the aspects that started to be considered in the scope of research on Teletandem was the transcultural contact integrated in these interactions. Thus, in a new version of the project, Teletandem is redefined as:

A mode of telecollaboration—a virtual, collaborative and autonomous context for learning foreign languages in which two students help each other to learn their own languages (or language of proficiency). They do so by using the text, voice and webcam image resources of VOIP technology (such as Skype), and by adopting the three principles of tandem learning: autonomy, reciprocity, and separate use of both languages. (Telles, 2015, p. 652)

It is important to mention that the Teletandem teaching and learning process has always been based on the principles of autonomy and reciprocity shared by the interactants. It is not a simple chat between a bilingual pair; instead, “Teletandem interactants are interested in learning each other’s language through a distance learning process and in a relatively autonomous way” (Telles & Vassalo, 2006, p. 194).

Throughout the years, many changes have taken place concerning the form and consolidation of partnerships as well as the way sessions are conducted. In the beginning, interactions were independent and scheduled by the interactants themselves in an autonomous way, and there was no mediation process as it occurs after the establishment of group interactions. According to Aranha and Cavalari (2014), technology-mediated Teletandem emerges as a “way to promote foreign language learning and teaching through regular virtual meetings between two

38

speakers of different languages living in different countries” (p. 184). Nowadays, interactions

happen in groups, in laboratories from partner universities, during a schedule previously set by teachers or graduate students who act as mediators of the process, coordinating, organizing, and conducting the sessions. These changes require the establishment of a mediation process, and the way activities are conducted has to be considered, depending on whether or not the interactions integrate the schedule of regular classes and whether or not the activities are related to foreign language subjects.

When the interactions take place during classes as a part of the activities required in a language subject, they are called institutionally integrated Teletandem (Aranha & Cavalari, 2014). When the interactions are not required as activities of a language subject, they are called institutionally nonintegrated Teletandem. In some cases, Teletandem can be a voluntary practice, generally certified as complementary activities or counted as language laboratory exercises.

The organization of the mediation process has changed as new partnerships between other institutions and foreign universities have joined the project. Consequently, the objectives of this new format have been enlarged compared to the previous model, when partnerships were completely independent. On the one hand, this type of institutional modalities in groups was included to meet the demand from foreign universities interested in implementing Teletandem as a part of students’ regular activities in Portuguese lessons. On the other hand, this new configuration also meant, for Brazilian universities, the creation of a new environment outside the classroom for foreign language learning, where students not only find opportunities to be inserted in authentic contexts of communication but also share their experiences, which contributes to critical and reflexive learning.

Thus, the whole Teletandem process is constituted by interaction sessions and mediation sessions. During the interaction sessions, groups of students from two different universities, divided into pairs, learn each other’s language by using text, voice, and webcam image resources. Mediation sessions take place after each interaction session, when participants have the opportunity to report and share their experiences. In this context, mediators have to create strategies of intervention to trigger the teaching and learning process proposed by Teletandem. According to Telles (2015):

Mediation sessions are conducted by the teachers after each Teletandem session. They focus on aspects of the target languages, the students’ learning processes and the cultural aspects and themes that emerge (implicitly or explicitly) during the interactions. Mediation sessions can be conducted in either the native or target language, depending on the students’ level in the latter. The practice of conducting Teletandem mediation sessions requires knowledge about intercultural contact, discourse and communication. (p. 655)

However, the roles of mediators are not only restricted to supervising sessions, but they also develop different activities, such as researching, teaching, managing, supervising, etc. They can be professors, graduates, or undergraduate students who are a part of the Teletandem project and are responsible for organizing and supervising the interaction and mediation sessions in their multiple aspects, such as orientation of the use of technological tools, orientation of cultural and linguistic issues, and negotiation of partnerships.

Thus, mediation can be understood as a complex process with broader characteristics that, although including the mediation session in its restricted sense (cf. Telles, 2015, p. 655), does not imply that it is the only procedure involved. It is a whole process that is initiated with first contact with foreign institutions and extends to organization, monitoring, supervision, and evaluation.

According to Ramos (2013), the kind of control set up by this new configuration in a certain way has direct repercussions for the Teletandem principles of autonomy and reciprocity. However, without the presence of a mediator, as it occurs

39

in the independent modality, even though the interactants have much more autonomy, the levels of responsibility can vary according to partners’ characteristics, which can make the process less stable and less durable.