DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.13109Publicado:

2019-04-23Número:

Vol. 21 Núm. 1 (2019): Enero-junioSección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónTeaching English through task and project-based learning to Embera Chamí students

Enseñanza de inglés a través del aprendizaje basado en tareas y proyectos a estudiantes Embera Chamí

Palabras clave:

bilingüismo, estudiantes indígenas, tareas, proyectos, aprendizaje (es).Palabras clave:

bilingualism, indigenous students, project-based learning, tasks-based learning (en).Descargas

Referencias

ACNUR, (2013). Colombia: Construyendo soluciones sostenibles. [Colombia: Building sustainable solutions] Retrieved from http://www.acnur.org/fileadmin/Documentos/RefugiadosAmericas/Colombia/2013/TSI_Caqueta_SanJoseCanelo_octubre2013.pdf [Link]

Alhomaidan, A., (2014). The effectiveness of using pedagogical tasks to improve speaking skill. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 7(3), 461-467.

Arismendi, F., Ramirez, D. & Arias, S. (2016). Representaciones sobre las lenguas de un grupo de estudiantes indígenas en un programa de formación de docentes de idiomas. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 18(1), 84-97. https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n1.8598 [Link]

Buck Institute for Education. (2015). What is project based learning (PBL)? Retrieved from: https://www.bie.org/about/what_pbl [Link]

Clavijo, A., & González, A. (2016). The missing voices in Colombia Bilingue: The case of Embera children’s schooling in Bogotá. In N. Hornberger (Ed.), Richard Ruiz: Essays on language planning and bilingual education (pp. 430-457). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Cook, V. (1993). Wholistic multi-competence - Jeu d´esprit or paradigm shift? In B. Kettemann & W. Wieden (Eds.), Current issues in European second language acquisition research (pp. 3-8). Tübingen: Narr Verlag.

Cuasialpud, R. (2010). Indigenous students’ attitudes towards learning English through a virtual program: A study in a Colombian public university. Profile, 12, 133-152.

Jara, O. (2013). Orientaciones teórico-prácticas para la sistematización de experiencias. Centro de Estudios y Publicaciones Alforja, 1-17. Retrieved from http://www.bibliotecavirtual.info/2013/08/orientaciones-teorico-practicas-para-la-sistematizacion-de-experiencias/ [Link]

Lasagabaster, D. (1999). El aprendizaje del inglés como L2, L3 o Lx: ¿En busca del hablante nativo? Revista de Psicodidáctica, 1(8), 73-88.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2005). Base para una nación bilingüe y competitiva. [Base for a bilingual and competitive nation]. Altablero. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-97498.html.[Link]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. Icfes Saber Mejor. (2017). Resultados para entidades territoriales. [Results for territorial entities]. Retrieved from http://www2.icfes.gov.co/instituciones-educativas-y-secretarias/saber-11/resultados-saber-11 [Link]

Norris, J. (2016). Current uses for task-based language assessment. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, 230-244. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190516000027 [Link]

Nunan, D., & Carter, R. (2001). The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Perilla, I. (2013). La contribución al desarrollo local de los gobiernos territoriales a través de iniciativas de cooperación internacional descentralizada. Estudio de caso: Cooperación del país Vasco a Florencia, Caquetá (2010-2012) proyecto Embera Chamítea (tierra, educación y artesanía) (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá.

Richards, J., & Renadya, W. (2002). Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press . https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667190 [Link]

VanPatten, B., & Williams, J. (Eds.). (2015). Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Villavicencio, R. (2009). Manual autoinstructivo Aprendiendo a sistematizar las experiencias como fuente de conocimiento. Lima, Peru: GTZ.

Winnefeld, J. (2013). Task-based language learning in bilingual Montessori elementary schools: Customizing foreign language learning and promoting L2 speaking skills. Linguistik Online, 54, 69-83.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Recibido: 28 de marzo de 2018; Aceptado: 7 de marzo de 2019

Abstract

Bilingual indigenous students who attend public schools around the country are to develop English language skills as part of the suggested curriculum created by the Colombian Ministry of Education. This is the case of the Embera Chamí students in Florencia, Caquetá whose conditions for learning English differ from those of monolingual Spanish students. The purpose of this study is to analyze the difficulties and the advantages of learning English through task- and project-based learning in bilingual indigenous students. The analysis of the study was developed through the method of systematization of experience. Results suggest that the two learning approaches enhanced indigenous students’ speaking skills and facilitated vocabulary recognition. However, the students mentioned being more interesting in learning English for specific purposes.

Keywords:

bilingualism, indigenous students, project-based learning, tasks-based learning.Resumen

Los estudiantes indígenas bilingües que asisten a escuelas públicas alrededor del país deben desarrollar habilidades en el idioma inglés como parte del currículo sugerido por el Ministerio de Educación Colombiano. Este es el caso de los estudiantes Embera Chamí en Florencia, Caquetá cuyas condiciones para aprender inglés difieren de los estudiantes monolingües de habla hispana. El propósito de este estudio fue analizar las dificultades y las ventajas del aprendizaje del inglés en estudiantes bilingües a través de un enfoque basado en tareas y proyectos. El análisis del estudio fue desarrollado a través del método de investigación sistematización de experiencias. Los resultados del estudio sugirieron que los dos enfoques de aprendizaje mejoraron las habilidades de habla de los estudiantes y facilitaron el reconocimiento de vocabulario. Sin embargo, ellos mencionaron estar más interesados en aprender inglés para propósitos específicos.

Palabras clave:

bilingüismo, estudiantes indígenas, tareas, proyectos, aprendizaje.Introduction

Indigenous children have begun attending public schools in Colombia in order to obtain education and, consequently, better opportunities for their future. These children are bilingual as they speak their mother tongue (Embera) which was acquired at home, and Spanish as the official spoken language in Colombia. These indigenous children are taught in Spanish and they follow the same academic curriculum of any public school in the country which means that they must study English. Moreover, the Colombian government through the National Ministry of Education has created “the Bilingual Colombia Program” (BCP), which set the goal of increasing students’ English proficiency to a B1 level by the year 2025. This program not only represents a challenge for the bilingual indigenous students but also generates many questions and concerns regarding both the conditions and manner in which these indigenous students are learning English to fulfill the BCP’s goal.

According to Arismendi, Ramirez, and Arias (2016), in Colombia there are approximately 65 indigenous languages within the country. Some of the members of these communities live on indigenous reservations while others are currently living in cities due to poverty or forced displacement, as is the case of the Embera Chamí community who are settled in Florencia, Caquetá. On the indigenous reservations, there are educational institutions where teenagers attend to classes every week and are required to learn English according to the guidelines established by the Ministry of Education (2005) in the English Suggested Curriculum. In addition, the government measures high school students’ language proficiency annually through the standardized test Saber 111. Results of this test offer a wide perspective in relation to indigenous schools whose performance in English is usually the lowest of the whole department as in the case of Caquetá as reported by the results of the Icfes’ (2017) for territorial entities.

This situation creates a huge debate as to whether or not indigenous students should learn English, or whether learning English will endanger their mother tongue and their group identity by displacing them as non-academic targets. Many of the youngest generations of indigenous students learn Spanish and discontinue using their mother tongue as they grow up (Clavijo & González, 2016). Therefore, government policies should also consider how multiculturalism may affect indigenous students’ identity as well as the use of their mother tongue. Furthermore, there are also concerns related to instruction and, for instance, the specific types of curriculum and methodology that could integrate their traditions and cultures according to the interest of the ethnic groups. Clavijo and González (2016) claim that “some curricular and educational contexts lack knowledge about the indigenous people’s ways of learning, causing a mismatch between the community interests and schools” (p. 433). This idea alerts teachers and researchers as to how adequate the educational system may be in addressing the indigenous students’ needs, values, and culture since the way they learn differs from that of monolingual students.

On the other hand, this leaning experience is analyzed to provide the opportunity for a critical and reflective account, as Villavicencio (2009) 2 believes that the exploration of and thinking about what happens at the beginning of any educational process can provide interesting lessons on how to do things better. In this sense, the systematization of this experience will offer a broader perspective that could be used to enhance students’ English skills. Furthermore, our results suggest possible changes and adjustments to be considered while teaching bilingual indigenous students regarding the social and cultural needs of this community. In addition, our study also sought to identify some of the benefits as well as the disadvantages that indigenous students presented while implementing two learning approaches.

Context Description

This study was conducted at the indigenous reservation Embera Chamí, which is located in San José de Canelos, 22 kilometers south of Florencia, Caquetá. As reported by ACNUR (2013)3, this community consists of 45 families and 167 members including children, teenagers, and adults that were settled upon approximately 294 acres. This experience was conducted and systematized in the first half of 2014, from February to June.

Community history. According to one of the indigenous community leaders, in 1961, 16 families of the Embera Chamí community arrived from the Valle del Cauca department fleeing violence among the different armed groups in the region. The indigenous community settled in a small township called Honduras in Caquetá. After 20 years of being settled there, by 1982, some indigenous community members were accused of being informants and were killed by the Guerilla forces that dominated the region. Therefore, some indigenous individuals abandoned the township and returned to Valle del Cauca to get back to their former lands. However, ACNUR (2013)4 asserted that displacements continued with the indigenous people who remained in the Honduras shelter until 2005. Thus, they moved back to Caquetá but this time, they settled in Florencia. They began to inhabit a part of the city which is now known as the Andes Bajos neighborhood. Given the number of Embera Chamí who now inhabit this sector, this place is now known as ‘the indigenous street’ (Rojas, L. personal communication, March 4, 2014). As Perilla (2012)5 explained:

Within the displaced community in Las Malvinas three problems could be identified: (1) The Embera-Chamí lacked access to utilities and were in a situation of overcrowding (about 60 people in 4 houses) with multiple diseases that particularly affected children and elderly; (2) children and young people were forced to the streets to beg for money, make crafts for sale, and (3) were gradually losing their ancestral customs in a constant struggle to survive. (p. 35)

Subsequently, the rest of the community took refuge in the houses that their families had built in the Andes Bajos neighborhood and lived there for seven years until they were relocated to San José Canelos in 2012, thus creating the indigenous reservation for the Embera Chamí. The purpose of that relocation was based on promoting their culture, language, and tradition that in some ways was affected by the migration process. Currently, they support their families by producing artisanal crafts (necklaces, earrings, bracelets, and ornaments) that are sold in different national fairs such as Cali, Bogota, and Medellin.

Children and adolescents under 25 who have grown up in the city have not lost their mother tongue; in contrast, they have acquired it simultaneously with Spanish. Thus, the indigenous community prioritizes the use of Embera within their families as the primary source of communication while Spanish is essential to communicate with the rest of society. This peculiarity in their bilingualism concerns researchers about which is the indigenous community’s first language. It is important to note, therefore, that if a child is able to understand both languages at the age of three, he or she has developed simultaneous bilingualism, which means that the child has acquired two languages as a first language (Nunan, & Carter 2001). Thus, these indigenous children are able to communicate in Embera and Spanish which allows them to attend public schools to get a formal education.

Theoretical Framework

Three main perceptions are triangulated in this study. First, that the insight that bilingual people have advantages learning an L3 over monolinguals. Second, that projects and pedagogical tasks are successful tools to improve learners’ language proficiency, and third, the ways in which tasks should be distributed in face-to-face classes to better satisfy the learning needs of indigenous students. As Alhomaidan (2014) mentioned, “a quick review of task-based literature shows that the use of tasks to teach language skills in second language courses has always been successful” (p. 462).

Lasagabaster (1999) 6 suggests that several studies show that a bilingual person has greater possibilities in learning an L3 in comparison to a monolingual individual. Bilingual speakers show different metalinguistic awareness than monolinguals as well as different cognitive processes. Bilingual people, therefore, are aware of linguistic forms, which mean that they have a greater ability to think flexibly and abstractly about language structure. Lasagabaster (1999) also asserts that being bilingual does not simply mean having two monolingual systems in a person’s brain; it means that there is a unique combination of the language structures in the language device. Moreover, as suggested by Cook (1993), both language competences are merged into one complex grammar rather than two, in what he calls wholistic multi-competence. In his article, Lasagabaster (1999)7 highlights that:

A) L1 and L2 share the same mental lexicon.

B) Speakers of an L2 can easily switch from one language to another; the ability of bilinguals to continually change from one language to another is now seen as a skill that requires great ability and is very complex.

C) The processing of L2 cannot be separated from that of L1; There is evidence that while L2 is being processed the L1 is not unplugged, but remains in service. (p. 79)

In addition, Lasagabaster (1999) also suggests some relevant differences between monolingual and bilingual language systems. First, having two language systems in one brain has effects on both L1 and L2 knowledge; second, bilingual people have better results when learning an L3 than monolingual individuals learning an L2. Finally, metalinguistic awareness is different as well as a bilingual person is able to think about abstract structures and understand them better and faster than a monolingual person. Talking to bilingual people in order to avoid monolingual prejudices, Cook (1993) recommends that instead of complaining about how bad a bilingual person dominates an L2, he or she should be sorry for those individuals who do not enjoy the advantages of the multilingual potential that each person is born with (Lasagabaster, 1999)8.

On the other hand, Norris (2016) reviewed how task-based language assessment (TBLA) has been integrated as an evaluative component of task-based language teaching (TBLT). Tasks have been incorporated as part of the assessment process as a useful and worthwhile element to evaluate students’ performance. With the recent demands of interactive assignments in which language could be observed in actual use, TBLA offers a wide range of opportunities for using communicative tasks as the main source to assess students in task-based classrooms. Tasks have become famous for their authenticity because they represent real-life assignments that every student is required to accomplish in a particular context. In educational settings, tasks are part of the proficiency assessments which evaluate the range in which a student is able to use his language abilities to be admitted or placed at the university level.

Finally, as educational implications, Norris (2016) asserts that tasks are also used for language educational assessment because they convey language abilities in engaging and individualized communication environments that were not practical for traditional settings. Norris (2016) suggests that “a primary motivation for incorporating TBLA into language education has to do with the need to align assessment, curriculum, and instruction such that they complement each other in supporting effective language learning” (p. 237). Tasks are used for summative and formal assessments that enhance the opportunity to provide feedback to students as well as to assess both curriculum and instruction. Furthermore, tasks offer opportunities to observe the language in a meaningful context that can reveal important aspects that would not be perceived in other ways.

Finally, Cuasialpud (2010) reported the performance of two indigenous students who were learning English through the ALEX program at the Universidad Nacional in Bogotá, Colombia as part of the requirements for graduation. The ALEX program has two different approaches-one is a face-to-face setting and the other one is a virtual modality that uses the Blackboard platform as a virtual classroom. The indigenous students chose to study through the virtual modality. Those students came from two different communities, one from the Coconuco Indigenous Community in Cauca, and the other from the indigenous community in Pasto, Nariño. The indigenous students were involved in a multilingual environment because they were learning English as an L3, they spoke their native languages as an L1, and they used Spanish as their L2.

Cuasialpud (2010) explains how indigenous students are often required to learn English at the university with little or no prior knowledge because of the limited instruction they received in their schools. This situation places them at a lower proficiency level than the rest of their monolingual classmates making explanations harder to understand and follow. Additionally, this issue also negatively affected their motivation specifically in relation to the virtual classes with the ALEX program. The results of the study indicated that students showed a preference for face-to-face classes where they could ask questions, communicate with peers, and engage in daily interaction that enhanced their understanding. Moreover, students blamed their poor performance on the virtual course due to their low English proficiency level, their poor learning background they had at school, and finally, because of the challenges that learning English through technology brings to a person who is not used to it.

Methodology

This study was conducted through the research method systematization of experience. As posed by Villavicencio (2009) 9, “to systematize is to comprehend and provide sense to difficult processes in order to extract meaningful lessons from the experience to produce new knowledge’’ (p. 25). Thus, the systematization of the experience allows researchers to gain valuable insights into the students’ learning process by chronologically describing the story of the events as they happened, analyzing the experience to build a critical view of the facts, and explaining the relationship between innovative proposals and meaningful learning. As Jara (2013) mentions, “it is not limited to narrating events, describing processes, writing a memory, classifying types of experiences, ordering data. All this is just a basis for a critical interpretation” (p. 4)10. Furthermore, this research method follows seven steps or tasks for the development of the systematization. Villavicencio (2009) provides the following description of those steps:

-

Discussion of the fundamentals [object and axis].

-

Accuracy of systematization questions [fundamental questions that come off the axis].

-

Systematization design [roadmap].

-

Recovery of experience [recovery and processing].

-

Analysis of the information [reflection from the axis and questions].

-

Interpretation of the findings [lessons or lessons learned].

-

Preparation of the report [communication of the lessons learned].

Finally, this study follows a qualitative approach that implements surveys, questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and a focus group as methods of data collection. The focus group was organized by the teachers, the indigenous students and parents with the purpose of promoting the deconstruction of the experience by analyzing and relating the events in chronological order while sharing their personal experience during the study and finding meaningful lessons that could be applied in the future.

Participants and Instruments

Participants included 16 male and female adolescent students between the ages of 14 and 19 from the Embera Chamí indigenous community. All students were enrolled in middle school from sixth to ninth grade. As the study began, they were not receiving any English classes; however, they were attending a school inside the shelter in which they had one teacher who was in charge of all classes. The students suggested that their familiarity with the English language was quite low as a result of their poor learning background experience.

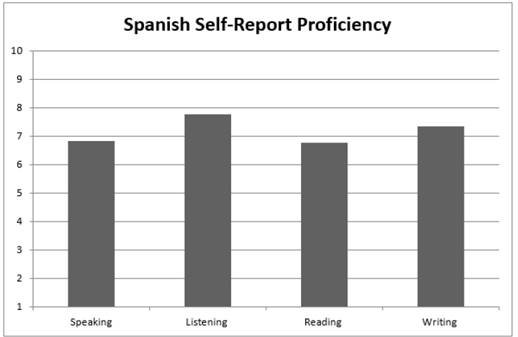

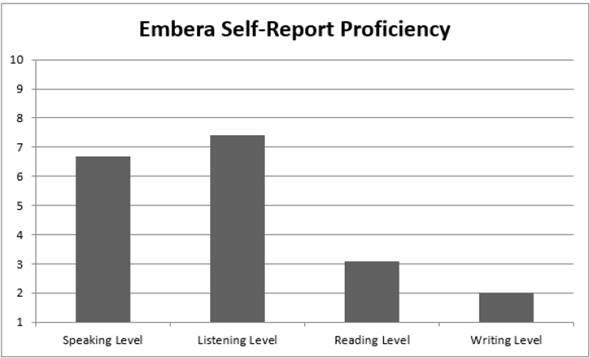

Introductory survey. A survey regarding the language proficiency self-concept in the four Embera and Spanish language skills was applied to the indigenous students who participated in the research project. Nunan and Carter (2001) explains than when a child grows up with simultaneous bilingualism, one of the two languages is dominant, which means that they feel more comfortable using one language than the other. Therefore, we asked the students to self-report their language skills from 1 to 10 so that we could have a reference regarding their dominant language in order to plan the teaching strategies. According to the survey, the indigenous students felt more comfortable using Spanish than Embera. They reported Spanish language proficiency skills individually and the average rank for the four skills was 7.1 with listening and speaking being the strongest skills (see Appendix A). In contrast, their Embera language proficiency was scored 4.7, where reading and writing where the weakest skills (see Appendix B).

Language teaching approaches. The purpose of this study was to analyze the difficulties and the advantages of learning English through task- and project-based learning in bilingual indigenous students. Therefore, the study was guided by two different instructional approaches-task- and project-based learning. Winnefeld (2013) mentions that the former one is an approach for foreign language learning that hence language proficiency through communication. This suggests that while students strive to use the language to perform daily activities, their proficiency improves as well. Within this approach those particular learning activities are known as tasks. Richards and Renadya (2002) state that “tasks provide instruction to students and opportunities to use language meaningfully, both of which are generally considered valuable in promoting language acquisition’’ (p. 109). On the other hand, according to the Buck Institute for Education (2015), “project-based learning is a teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging and complex question, problem, or challenge” (para. 3). Consequently, this study sought to analyze both the benefits and the challenges of these two approaches in bilingual indigenous students.

Systematization of the experience. With these ideas in mind, the research experience began in March of 2014. The teacher met the indigenous of the community at ‘El Tambo,’ where the community holds meetings and cultural activities. At the reservation there was also a school where children and teenagers were studying, a soccer field, and houses with utilities like electricity, water, and large septic tanks.

Moreover, San Jose is a very remote place and requires a significant amount of effort and time to get there. Thus, the atmosphere was perfect for young people to recover their culture, customs, and language. Additionally, parents clearly knew that the place where they lived in Florencia was surrounded by drugs which was deeply affecting the community. With that in mind, parents and community leaders were happy to be in that location, but they said that life was not easy at all. Field work was very hard and they had lost the habit of tilling the ground.

As an introduction, teachers met the students and explained to them the benefits this learning experience will have on their English skills. The teaching schedules were organized and students agreed to attend classes every Monday from 3:00 to 6:00 pm. A survey was given to the students to identify their language proficiency self-concept in Embera and Spanish related to four skills (listening, speaking, reading, and writing). Many of them said that they did not feel comfortable speaking their mother tongue. The teachers explained to the students the two learning approaches that would be used in the English class. Taking into account the drug problem the community was facing in Florencia, with the approval of the students, it was decided to center the project on the topic: Awareness of drugs’ harmful effects.

The teachers started this learning experience by making a presentation about drug addiciton in Spanish (instead of English due to the students’ language limitations). However, the presentation titles and keywords were written in English (anxiety, depression, problems, drugs, family, addiction, stress, abuse, among others). Next, several videos were presented related to the impact of drugs on the brain as well as the life story of a young man who died from drugs abuse. After that, a video about how to say not to drugs was presented. This one illustrated a real life situation in which young men could be induced into drugs. Teachers, from time to time, stopped the video and explained what was going on during specific parts in order to help the indigenous students understand the whole message. Finally, teachers and students analized the harmful effects drugs have upon people’s lives. The students excitedly participated and talked about how the videos and the presentation helped them understand this social problem and how they could avoid falling in these situations. Some of the students mentioned the problems that hallucinogenic drugs brought into their lives while living in Florencia

Following the presentation of the videos, the teachers assigned the fist task, with a list of drugs that could be used by teenagers. Students were allowed to choose one type of drug they would like to talk about in the following class and the teachers already had information about each of the possible issues to be presented. Students made four groups of four people and they chose to speak about alcohol, nicotine, cocaine, and marijuana. Each group was given a sheet that contained information in English and Spanish related to the type of drug they had chosen. They were assigned to carefully read the information to present it next class. Students agreed to read and highlight important sentences in Spanish and English that could be used in their final presentation; they also were asked to talk about the harmful effects drugs have on the brain. The teachers picked a leader in each group to keep the information and ensure that the other students would read the information.

Before returning home, the teachers interviewed the governor of the Embera Chamí community who expressed his gratitude to them for contributing to the young students’ wellbeing and learning. Some of the students had lived there for approximately eight months, and their parents’ expectations were focused on helping their children attain bachelor’s degree in agriculture and teaching to contribute to the development of the community. The governor considered English classes very important because they allow students to prepare for college. The parents also recognized that their children did not have any contact with the English language at school; in fact, they study in a school where English is not taught.

The coming week, the teachers had their second encounter with the indigenous students. To start the class, they did a total physical response activity in which students learned common words in English related to drugs and addiction. When the teachers proceeded to review the assignment, they found that two groups had lost the material without studying it, and the other two groups still held the information but did not read it. Only one student had read about marijuana and he explained the negative effects of marijuana. He also underlined sentences in English and was ready to continue.

Then, the teachers asked the students to gather in their groups and read about their chosen theme. They began to read together, and after a while, the teachers visited group by group and each student shared what they have learned. Next, they did a round table where all students participated and provided their opinions. Then, the teachers helped each group to point out a few important sentences in Spanish and English. They also helped them to pronounce the sentences they had picked and they were assigned to write them down in their notebooks.

Later on, the teachers held the first meeting with the focus group to inquire parents about their children’s learning process. The parents recognized that learning English could open doors to directly communicate with members of nonprofit organizations that visit the community and do not speak Spanish. They also suggested that having English skills could also increase their crafts market because they attend national fairs where many tourists would buy their products. They agreed with the teaching approaches implemented by the teachers and showed gratitude for the teaching process.

At the next meeting, the teachers summarized the information that they had previously given to the indigenous students. Once again, they found that the students did not practice the assigned pronunciation drills because they had lost them. Therefore, students were re-organized in groups because some of them had stopped attending classes. The teachers also gave them some short sentences and proceeded to slowly read them in English while students wrote the pronunciation down. Once they finished, teachers recorded the English sentences on students’ cell phones so that they could listen to them during the week and, consequently, be able to move on to the next stage of the project.

Subsequently, some students expressed that it would be better to receive these classes during school hours as their regular English class because they feel discouraged by not being graded. They said: “it did not make sense to attend classes if they did not receive a score for their English subject.” Others said they wanted to learn English in different ways. They wanted to learn English through grammar. Therefore, the teachers explained that the purpose of the study was to implement these approaches to identify potential advantages and disadvantages.

Teachers met for the fourth time with students and met their schoolteacher. She teaches grades six through nine and stated that she did not know English, so she wanted this practice to replace her English classes. Thus, the teachers would be able to report a score for each student and it would be their final grade for the whole period. The teachers happily accepted her proposal in view of what students had said. This opportunity would introduce a new element in the research process that would increase students’ commitment. The teachers met again with the students and told them that their participation in this program would count as their English score.

Besides, the teachers explained how the students would make their projects presentation in English and Spanish to allow their parents understand it. After that, the students were given watercolors, brushes, and large sheets of poster board to design their presentations. They immediately began to draw and paint and, as they did, the teachers reviewed their pronunciation and the students asked them to write how to correctly pronounce their sentences in their notebooks. The students took a very optimistic and committed attitude.

While the students were preparing for their presentation, the teachers found that students should write the pronunciation of each word, otherwise, they would continually pronounce the words as if they were reading in Spanish. A common example of this is a student pronouncing my name is as /mi name is/.

During the fifth class, the teachers returned to the community to have their penultimate meeting. Several students had reviewed their assignments; they listened to the recording and reviewed the pronunciation of the sentences. The teachers continued with their previous procedures. They reviewed the material again with the students and helped them memorize the sentences. The posters were reviewed and finished, and, by the end of the class, everything concerning the presentation of the project was organized. That afternoon two interviews were conducted. An indigenous student’s mother attending the weekly meetings mentioned that “having an indigenous teacher from [their] own community is necessary to strengthen indigenous culture and language.” Then, she talked about the forced displacement of her community that took place more than 40 years ago, as they were considered informants and were expelled from the indigenous reservation in Honduras, Caquetá.

For the last meeting, the teachers returned to the reservation for the students’ presentations. Parents came to watch their children’s performance and laughed a lot while they saw their children making their presentation. Some students felt embarrassed because they were speaking in English. Finally, the teachers told the parents to avoid laughing not to make the students feel uncomfortable. The indigenous students presented first in Spanish and then in English to allow their parents understand what they were talking about.

As a concluding activity, the teachers met with the parents to debrief the entire process. A summary was read concerning very important aspects of the children’s participation in the research process. They agreed with the report and expressed gratitude for the service that had been provided. The teachers told them that the English encounters would finish that day, but they would be very happy to come back at any time to continue working with the students. They also said that the community doors were open to receive them again because they would like their children to continue with the learning process.

Findings

Group A

By the end of the study, the teachers had a meeting with the indigenous students to analyze the experience and gather feedback about the learning process. The teachers wanted to know how they felt about the teaching methods, the tasks, and their points of view about the benefit of the project. The students first stated that even when they felt very comfortable with the learning process, when they realized they had to do homework, some of them got discouraged and stopped attending. In addition, another reason why they stopped attending classes was because they thought it would not benefit their grades in their regular English class.

In relation to task completion, some said it was hard to memorize sentences because they did not understand everything that was recorded in the audio, or sometimes they did not understand what they had written in their notebooks. In relation to the project, a couple of students claimed that they had learned nothing; they expected to speak English fluently by the end of the classes, but it did not happen. Then, the teachers began to ask for vocabulary they had studied while they learned about drug addiction and some of them cited words and even sentences related to the theme. Further, both the students and the teachers reflected upon the harmful effects of drug addiction on people’s lives and on their own community. After this, the teachers concluded that learning a new language is a step-by-step process, and that what they experienced during this project was just one of the many steps needed in order to learn the language. However, even though the learning methods were different than the one used at school, this did not mean that they were not valuable to student learning. Finally, the students agreed with this perspective and suggested that for future opportunities, they would like to learn the kind of English they need to use to sell their crafts in different fairs around the country.

Conclusions

One of the benefits of task-based learning for the indigenous students was that it helped them to communicate their ideas about drug addiction. The students remembered what was taught in previous classes, identified the main features of the theme, and used the language during classes to perform their activities as well as during their presentations. One of the main difficulties encountered in this process in relation to tasks was the lack of commitment students had in relation to the compliance of the assignments. As it was mentioned before, it was hard for them to memorize some sentences and when listening to the audio, some of them did not understand what was said. Moreover, when helping indigenous students to perform their tasks, it was necessary to write down the English pronunciation of the utterances they were trying to convey because they tend to think that English words are pronounced in the same way in which they are written.

With regard to project-based learning, indigenous students learned vocabulary related to drug addiction, improved their pronunciation, reflected upon on the harmful effects that drugs have on their brain, body, and family life. In addition, giving a presentation in front of the whole community helped them to overcome the fear of public speaking. On the other hand, one of the major difficulties found in the implementation of project-based learning was that students tended to think they were not learning because this approach is different to that which is traditionally used at their school. Therefore, it was necessary to consistently and thoughtfully reflect with students regarding the different topics, vocabulary, and expressions they were learning as well as to highlight how they unconsciously improved their pronunciation by preparing for the presentation.

On the other hand, when teaching English to the indigenous students of the Embera Chamí community, teachers can use Spanish as tool to clarify concepts to students because, according to the Spanish and Embera self-reported proficiency surveys, the indigenous students reported that Spanish is their dominant language. These students claim to have a greater mastery of the four Spanish language skills (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) and weaknesses in the four Embera language skills. This condition may be a meaningful insight regarding the effect of an L1 upon learning an L3.

As mentioned before, Embera and Spanish are considered their L1 because they learned them both simultaneously, nonetheless, the Embera phonological and morphosyntactic features are quite different from those of the English language. Therefore, the linguistic distance between Spanish and English is closer than the distance between Embera to English. As VanPatten and Williams (2015) mention, when a person uses his competences of the L1 to communicate in an L2, this is known as transfer. This transfer may be positive or negative depending on how linguistically related the two languages are. Nevertheless, both types of transfers may be found in an L1 to L2, an L2 to an L3, or an L1 to an L3. In this particular case, Embera does not seem to be as close to English as Spanish. However, the case where the indigenous students were pronouncing words in English as if they were reading in Spanish was evidence of an interference caused by the negative transfer the indigenous students were unconsciously trying to do from their dominant L1 to the L3. Conversely, when learning words that are morphologically similar to Spanish like drug addiction, family, abuse, curiosity, problems, stress, and anxiety among others, they seemed to remember them easier than others.

Moreover, Lasagabaster (1999) stated that bilingual people may achieve better results when learning an L3 due to their metalinguistic competences that allow them to think abstractly about the components of the language. In the case of the Embera Chamí students, this learning experience indicates that they were able to easily communicate ideas in English with words that were familiar to them in Spanish. They remembered them faster and pronounced them better than unfamiliar words. Consequently, when learning English, they relied on their Spanish competences as a strategy to communicate their ideas. Nevertheless, further research in teaching English to monolingual Embera Students is needed in order to compare and contrast it with the results of this study.

Finally, additional analysis of the benefits and limitations of implementing task-based learning and project-based learning on bilingual indigenous students is required. Reflecting upon what happened throughout this educational process provided basic insights related to improving instruction in this context, but certainly did not answer every possible question in relation to the implementation of those two approaches with bilingual indigenous students. In addition, it would be interesting to study the linguistic distances between Embera and English to identify the possible positive and negative transfers between the two languages and the effect of the interference on indigenous students’ learning.

References

Appendix A

Figura 1: Results of self- reported Spanish language proficiency survey

Appendix B

Figura 2: Results of self- reported Embera language proficiency survey

Métricas

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2019 Luis Ricardo Rojas

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivadas 4.0.

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/