DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.14638Published:

2020-12-20Issue:

Vol. 22 No. 1 (2020): January-JuneSection:

Reflections on PraxisModernizing English Teacher Education in Chile: A Case Study from a Southern University

Modernizando la formación inicial de docentes en Chile: un estudio de caso de una Universidad del Sur

Keywords:

Chile, Content and Language Integration, EFL, English Immersion, Initial Teacher Education (en).Keywords:

Chile, Formación inicial docente, EFL, Inmersión en inglés, Integración de contenidos e idiomas (es).Downloads

References

Abrahams, M. J., & Farias, M. (2010). Struggling for change in Chilean EFL teacher education. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 12(2),110–118.

Alarcón Leiva, J., Hill, B., & Frites, C. (2014). Educación basada en competencias: Hacia una pedagogía sin dicotomías. Educação & Sociedade, 35(127).

Ávalos, B. (2014). La formación inicial docente en Chile: Tensiones entre políticas de apoyo y control. Estudios Pedagógicos (Valdivia), 40(ESPECIAL), 11–28.

Ball, D., Thames, M., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59, 389–407.

Banegas, D. L. (2012). Integrating content and language in English language teaching in secondary education: Models, benefits, and challenges. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 2(1), 111–136.

Barahona, M. A. (2014). Exploring the curriculum of Second Language Teacher Education (SLTE) in Chile: A case study. Perspectiva Educacional, 53(2), 45–67.

Barahona, M. (2015). English language teacher education in Chile: A cultural historical activity theory. New York: Routledge.

Barahona, M. (2016). Challenges and accomplishments of ELT at primary level in Chile: Towards the aspiration of becoming a bilingual country. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24, 82.

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. ERIC Digest.

Cammarata, L., & Tedick, D. J. (2012). Balancing content and language in instruction: The experience of immersion teachers. Modern Language Journal, 96(2), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2012.01330.x

Cammarata, L., Tedick, D. J., & Osborn, T. A. (2016). Content-based instruction and curricular reforms: Issues and goals. In Content-Based Foreign Language Teaching (pp. 15–36). Routledge.

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Darwin, S., & Barahona, M. (2018). Can an outsider become an insider? Analysing the effect of action research in initial EFL teacher education programs, Educational Action Research. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2018.1494616

DeKeyser, R. M. (2018). Age in learning and teaching grammar. The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, 1–6.

Dafouz, E. (2018). English-medium instruction and teacher education programmes in higher education: Ideological forces and imagined identities at work. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(5), 540–552.

Díaz, C., & Bastías, C. (2012). Una aproximación a los patrones de comunicación entre el profesor mentor y el profesor-estudiante en el contexto de la práctica pedagógica. Educación XXI: Revista de la Facultad de Educación, 15(1), 241–263.

Faúndez, F., Gutiérrez, A., & Ponce, M. (2010). Transformación curricular en la Universidad de Talca. Presentación de un proceso en marcha. CINDA, Diseño Curricular basado en competencias y aseguramiento de la calidad de la educación superior, 239–300.

Freeman, D. (2016). Educating second language teachers. Oxford University Press.

Gómez Burgos, E. (2017). Use of the genre-based approach to teach expository essays to English pedagogy students. HOW, 24(2), 141–159. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.24.2.330

Gómez Burgos, E., & Pérez Pérez, S. (2015). Chilean 12th graders’ attitudes towards English as a foreign language. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 313–324.

Graddol, D. (2006). English Next. London: The British Council.

Guerra, P., & Montenegro, H. (2017). Conocimiento pedagógico: Explorando nuevas aproximaciones. Educação e Pesquisa, 43(3), 663–680. Epub 23 February 2017. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1517-9702201702156031

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching. Essex. England: Pearson Education.

Herrarte, D. L., & Beloqui, R. L. (2015). The impact of type of approach (CLIL versus EFL) and methodology (book-based versus project work) on motivation. Porta Linguarum: Revista internacional de didáctica de las lenguas extranjeras, (23), 41–57.

Leyva, M. O., & Díaz, C. P. (2013). How do we teach our CLIL teachers? A case study from Alcalá University. Porta Linguarum: Revista internacional de didáctica de las lenguas extranjeras, (19), 87–100.

Martel, J. (2013). Saying our final goodbyes to the grammatical syllabus: A curricular imperative. French Review, 86(6), 1122–1133.

Matear, A. (2008). English language learning and education policy in Chile: Can English really open doors for all? Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 28(2), 131–147.

MINEDUC. (2005). Autoevaluación Nacional de profesores de Inglés -[National Self-Assessment of Teachers of English]. Author. Santiago, Chile.

Motschnig-Pitrik, R., & Holzinger, A. (2002). Student-centered teaching meets new media: Concept and case study. Educational Technology & Society, 5(4), 160–172.

Mougeon, R., Nadasdi, T., & Rehner, K. (2010). The sociolinguistic competence of immersion students. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters.

Nunan, D. (Ed.). (1992). Collaborative language learning and teaching. Cambridge University Press.

O'Dowd, R. (2018). The training and accreditation of teachers for English medium instruction: An overview of practice in European universities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(5), 553–563.

O’Leary, Z. (2014). The essential guide to doing your research project (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Pennycook, A. (2017). The cultural politics of English as an international language. Routledge.

Pedraja-Rejas, L. M., Araneda-Guirriman, C. A., Rodríguez-Ponce, E. R., & Rodríguez-Ponce, J. J. (2012). Calidad en la formación inicial docente: Evidencia empírica en las universidades chilenas. Formación Universitaria, 5(4), 15–26.

Richards, J. C. (2017). Teaching English through English: Proficiency, pedagogy and performance. RELC Journal, 48(1), 7–30.

Savignon, S. J. (2006). Communicative language teaching. 2009). Concise Encyclopedia of Pragmatics. Oxford: Elsevier Ltd.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–31.

Simons, K. D., & Klein, J. D. (2007). The impact of scaffolding and student achievement levels in a problem-based learning environment. Instructional Science, 35(1), 41–72.

Snow, M. A. (2014). Content-based and immersion models of second/foreign language teaching. In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton, & M. A. Snow (Eds.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (4th ed., pp. 438–454). Boston: Cengage/National Geographic Learning.

Sotomayor, C., Parodi, G., Coloma, C., Ibáñez, R., & Cavada, P. (2011). La formación inicial de docentes de Educación General Básica en Chile. ¿Qué se espera que aprendan los futuros profesores en el área de Lenguaje y Comunicación? Pensamiento Educativo, 48(1), 28–41.

Tedick, D. (2013). Embracing proficiency and program standards and rising to the challenge: A response to Burke. Modern Language Journal, 97, 535–538.

Terigi, F. (2009). La formación inicial de profesores de Educación Secundaria: Necesidades de mejora, reconocimiento de sus límites Initial teacher training in Secondary Education: Needs to improve, acknowledgement of its limits. Revista de educación, 350, 123–144.

Vázquez, V. P., Molina, M. P., & López, F. J. Á. (2015). Perceptions of teachers and students of the promotion of interaction through task-based activities in CLIL. Porta Linguarum: Revista internacional de didáctica de las lenguas extranjeras, (23), 75–91.

Villarreal, G. (2017). Análisis sobre estudios, informes y encuestas del desarrollo profesional docente de inglés. Ministerio de Educación. Santiago, Chile.

Wan, Y. S. (2017). Drama in teaching English as a Second Language. A communicative approach. The English Teacher, 13.

Wilkinson, R. (2018). Content and language integration at universities? Collaborative reflections. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(5), 607–615.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2010). Understanding by design: A brief introduction. Center for Technology & School Change at Teachers College, Columbia University. Retrieved, 6(7), 07.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 15 de marzo de 2019; Aceptado: 12 de septiembre de 2020

Abstract

Initial teacher education programmes for future English teachers in Chile have been in the spotlight and under constant analysis in the last decade. The main reasons are the new demands of a globalised world, the current undergraduate programmes in the area that present a constant divorce between English and pedagogy and the consistently low student achievement outcomes on the standardised tests applied by the educational system. Under the previous considerations, this work reports on a pedagogical experience of implementing a new proposal for English teacher preparation offered by a university from the south of Chile. This innovative new teacher education programme is based on the following three important components: (1) the competency-based model adopted by the university, (2) the integration of the content and pedagogical knowledge in the programme and (3) the adoption of an immersion programme focussed on content and language integration. The data gathering and analysis comprise documents and pre-mid-point progress tests. The preliminary results show a marked improvement in the level of students’ English and an increase in their acquisition of the pedagogical concepts. Whilst minor changes are crucial to improve some aspects of the programme proposal, the overall results are promising.

Keywords

Chile, Content and Language Integration, EFL, English Immersion, and Initial teacher Education.Resumen

Los programas de formación inicial docente para futuros profesores de inglés en Chile han estado en el centro de atención y bajo constante análisis en la última década. Las principales razones son las nuevas demandas de un mundo globalizado, los programas actuales en el área presentan un divorcio constante entre el inglés y la pedagogía y los consistentemente deficientes resultados de los estudiantes en las pruebas estandarizadas aplicadas por el sistema educativo. En vista de los antes mencionado, este trabajo informa sobre una experiencia pedagógica de implementación de una nueva propuesta para la preparación de profesores de inglés que ofrece una universidad del sur de Chile. Este nuevo e innovador programa de formación docente se basa en los siguientes tres componentes: (1) el modelo basado en competencias adoptado por la universidad, (2) la integración del contenido y el conocimiento pedagógico en el programa y (3) la adopción de un programa de inmersión centrado en la integración de contenidos y lengua inglesa. La recopilación y el análisis de datos comprenden documentos y pruebas de progreso intermedias. Los resultados preliminares muestran una mejora en el nivel de inglés de los estudiantes y un aumento en la adquisición de los conceptos pedagógicos. Si bien los cambios menores son cruciales para mejorar algunos aspectos de la propuesta del programa, los resultados generales son prometedores.

Palabras clave

Chile, EFL, Formación inicial docente, Inmersión en inglés e Integración de contenidos e idiomas.Introduction

During the last twenty years in Chile, ‘initial teacher education has become a critical issue for educational policies’ (Guerra & Montenegro, 2017, p. 664). There is a consensus about the strategic importance of initial teacher training (Sotomayor, Parodi, Coloma, Ibáñez & Cavada, 2011) because of the increase in the number of institutions offering pedagogical programmes and because of the quality of these programmes. In this regard, educational authorities in the country have criticised the work of the universities in initial teacher preparation (Ávalos, 2014; Pedraja-Rejas, Araneda-Guirriman, Rodríguez-Ponce & Rodríguez-Ponce, 2012) due to the fact that the quality of the institutions does not guarantee the quality of their teacher education programme. This is certainly reflected in the results obtained by pre-service teachers on the national evaluation applied to measure the future teachers’ appropriateness of pedagogical knowledge on the basis of the national standards. [1]

Avalos (2014) emphasised the tensions between the policies of support and control in Chile regarding initial teacher preparation. These policies have been considered over the past 15 years considering regulation, support and control of processes that assure quality in the pedagogical programmes. Furthermore, these policies are aligned with the demands of the society and the process of globalisation and are ‘within the neo-liberal ideology and market concepts which have been present in Chilean policies and educational institutions in Chile since the 1980s’ (Ávalos, 2014, p. 11).

Taking these considerations into account, an overwhelming interest in English has risen around the world, not only in English-speaking countries but also in different countries where other languages are the mother tongues, e.g. Chile. For instance, the nomination of English as a Lingua Franca (Harmer, 2007) and the resulting designation of English as the language of business and technology give a clear remark on the implication of this language (Gomez, 2017; Gómez & Pérez, 2015).

In Chile, English as a foreign language (EFL) is unique in its status as the only compulsory foreign language of the national curriculum that all schools must teach from the fifth grade. However, there has been a latent increase in its inclusion in early primary education as well. Government officials have encouraged the introduction of English instruction as early as the first grade over the last 10 years (Barahona, 2016). This general atmosphere of promotion and significance of English in the country has stimulated the universities to open new pedagogical programmes, which has in turn increased the number of English pedagogy programme options in the different regions of the country. To our knowledge, the vast majority of these programmes have mainly followed a traditional approach to language teaching, focusing on structural or grammatical curricula that concentrate on teacher-centred methodologies. Abrahams and Farias (2010) explained that in Chile, ‘an urgent need arises for an innovative and very creative design to change the curricula at universities so that the country can raise the quality in foreign language education’ (p. 110).

Considering the previous scenario, initial English teacher training seems to be under a complex crisis. On the one hand, changes in the syllabi of EFL training programmes need immediate attention as a way of adapting new methodologies centred more on the needs of students. On the other hand, new proposals in the curriculum of EFL training programmes could be promising to the improvement of the student results in learning the foreign language in Chile. With the last consideration in mind, this work reports on a pedagogical experience of implementing a new programme for English teacher preparation in a southern university. This new innovation is based on the following three important components: (1) the competencybased model adopted by the institution, (2) the link between content and pedagogical knowledge in the programme and (3) the adoption of an immersion programme focussed on contemporary teaching methods. These three elements are essential for us to modernise English teacher education in Chile.

Initial EFL Teacher Education in Chile

Learning EFL has become a must in developing countries, especially in South America. In this regard, Matear (2008) claimed that more people are learning English in the region because authorities have placed emphasis on the inclusion of the language in their curricula to promote the development of the language. Results of this inclusion validate that more and more people speak English in the world. Nowadays, there are more second language speakers than first language speakers of English (Graddol, 2006). This situation is similar in Chile where the inclusion of English has been promoted by authorities, which has stimulated universities to create and offer new English teacher preparation programmes for the divergent educational stages.

Barahona (2016) elucidated that ‘most of the English teacher education programmes across the country are orientated to educate English teachers at the secondary level’ (p.18), which is simply because secondary education offers more hours to teachers to comply with the schedule in the same school and because of the lack of experienced English educators for early childhood or primary education. This last fact is the most problematic as there are not enough specialists in the field of teaching English to young learners in Chile.

In a pioneering study, Abrahams and Farias (2010) reported on some problems in EFL teacher education programmes within Chile. Firstly, the current offer of English undergraduate programmes from Chilean universities struggles with a constant divorce between English linguistics and pedagogy. This is essentially because there is an absence of clear communication between the English/Linguistics Department and the Education Department (or their equivalents in the institutions). Notwithstanding, the courses of the pedagogy programmes related to linguistics or English are taught by the faculty members of their respective department, and these professors rarely complement their modules with the courses or professors of the Education Department. To our knowledge, this problem is very common and pervasive in the faculties and departments where EFL teacher education programmes are affiliated.

Secondly, Chile struggles with persistently low student achievement outcomes in the SIMCE [2] tests applied by the educational system. The last measurement applied in 2014 reported that 53% of students in the eleventh grade achieved less than A1 level (Gómez, 2017); this reflects that students do not achieve the B1 standard demanded by the Chilean Ministry of Education at the end of secondary education. This is similar to the unsatisfactory level of English proficiency amongst teachers (Barahona, 2016). According to MINEDUC (2005), 2.177 teachers (29% of the total number of teachers) sat the Quick Placement Test. A total of 52% of teachers ranked from Breakthrough to ALTE 2. Further, the Examination for the Certificate of Competency in English (ECCE) was applied to 789 teachers in 2008 and the same examination to 474 teachers in 2009 (Villarreal, 2017). Table 1 shows the percentage of teachers who passed the examination in 2008 and 2009.

Table 1: Percentage of teachers who passed of the ECCE 2008 and 2009

Component

2008

2009

Writing

70%

81%

Listening

32%

44%

Grammar, vocabulary and reading

53%

76%

Speaking

71%

84%

Table 1 shows that in 2009, the percentage of teachers who passed the four components of the examination increased. The listening component remains the weakest of the areas, and speaking is the one with the best figures. Additionally, the components of grammar, vocabulary and reading are the areas that increased the most in the second application of the test. To our knowledge, English teachers in Chile in the school system need not only more support to improve their level of proficiency in the language but also special support to enhance their performance when delivering the English class.

Barahona (2014) commented that EFL ‘programs in Chile have followed an applied linguistic tradition’ (p. 46), which reflects that English language proficiency has been the most important component of the curricula of the programmes. Nonetheless, universities have begun implementing changes in the curriculum of their pedagogical programmes as a way of responding to the new demands in English teacher training. These demands are in terms of valuing the concept of English as an International Language (Pennycook, 2017) more than the language of a specific accent. The new demands also reflect the necessity of training a more complete teacher who, apart from knowing English, also knows how to design and implement lessons and apply more contemporary teaching methods centred on the needs of students in the classroom.

In this respect, Abrahams and Farias (2010, p.116) concluded that the new profile of English teacher preparation programmes must integrate a curriculum that includes the following two main strands: English Language and Teaching Methodology, which have their own sub-components as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 shows an improvement in terms of integrating English language areas by blending the study of the four skills instead of separating them into specific receptive and productive courses, as was the tendency in many programmes. It also evidences the role of reflection and school-based experiences and/or practicums as compelling elements of the programme, action research and methods. This last sub-component is given special attention with other sub-elements that contribute to the future teacher knowledge of important themes in language education.

Table 2: Strands of the integrated curriculum

English

Language

Methodology

1. Integrated skills: reading, writing, speaking and listening

1. Reflection workshops

2. Linguistic components: lexico-grammar and pronunciation

2. Field experiences

3. Culture and literature

3. Practicum

4. Reflective and critical skills

4. Action research

5. Methods

5.1. Teaching/learning strategies

5.2. Classroom management skills

5.3. ICTs and other resources

5.4. Assessment and evaluation

Similarly, Diaz and Bastías (2012) emphasised the role of sequential school-based experiences or practicums and how they have been integrated in the new curricula of English teacher preparation programmes in Chile. These practicums are used together with action-research courses at the end of the pedagogies as part of their degree programmes (Darwin & Barahona, 2018) to support the process of reflection that pre-service teachers must follow after their graduation.

Bearing in mind the previous considerations, the study reported here presents a description of the main elements of the curriculum for an initial English teacher programme in the Chilean context.

Description of the Experience

This work adopted a mixed-research method to characterise the new programme for English teacher preparation at a southern university in Chile. It is part of the triangulation design approach that concentrates on that particular situation or topic using complementary data. Document analysis combined with pre and mid-point progress tests was employed as a technique to collect data and as a means of triangulation, which was described by O’Leary (2014) as ‘using more than one source of data to confirm the authenticity of each source’ (p. 115).

Instruments

Diverse sources were utilised to triangulate data. Firstly, document analysis was conducted to describe the new programme and explain its main characteristics. It also includes the foundations of the programme and the information in the syllabi. Secondly, the results of the pre and mid-point progress tests were analysed. The instrument used was an international test called Aptis provided by the British Council. This test is an English language proficiency test composed of the following five parts: language skills (speaking, writing, reading and listening) and a grammar and vocabulary component. The test gives the results using the Common European Framework standards from level A1 to level C. Both instruments will be described in the next section as part of the proposal.

Procedure

Documents related to the programme were collected and analysed to be triangulated with the results of the pre and mid-point progress tests to see if there were any connection between them, that is, to see if there is an improvement in the student results after the implementation of the new curriculum. Both instruments were employed as a way of complementing quantitative and qualitative data. Moreover, descriptive analysis was conducted to explain the main features of the new programme included in the foundational documents, and basic descriptive statistics was also utilised with the information obtained from the results of the pre and mid-point progress tests.

Proposal: A New Curriculum for EFL Teacher Preparation

To introduce changes in EFL teacher education in Chile, this work offers a proposal centred around three main elements, namely, the competency-based model adopted by the university, the link between the content and pedagogical knowledge in the curriculum map and the adoption of an immersion programme focussed on contemporary teaching methods. These three components are the axis of this new innovative proposal. To our knowledge, they reflect the new tendencies in Chile in tertiary training and the future of foreign language instruction, and they are essential elements to modernise English Teacher Education in Chile. The term ‘Modernising’, as used in the context of this paper, refers to updating the strategies for teacher preparation to better shape the future teachers of Chile for the task of providing comprehensive lessons in English. The proposal aims to remedy the shortfalls of the language competency of Chilean English teachers and to match the call from the Chilean Ministry of Education to teach in a studentcentred, communicative style, as mentioned earlier.

Competency-Based Model

The Competency-Based Education Model implemented at the institution is a way to respond to the demands of society on the basis of a particular time and space. Alarcón, Hill and Frites (2014) highlighted that the inclusion of this model allows the design, implementation and evaluation of a curriculum without dichotomies given that it offers the apprentices the opportunity to develop their potential in performance situations. These situations have specific indicators to perform the evaluation of the progression of learning. In so doing, the milestones of verification for the achievement of the declared learning are identified and monitored through specific modules in the programme.

At this point, making the definition of the competence adopted by the university explicit is crucial. It indicates that a competent professional is one who knows how to act in a particular context, putting personal and contextual resources at stake (including networks) for the solution of a specific problem. This act is followed by a process of reflection on what is being done (Le Boterf, 2000 cited in Faúndez, Gutiérrez y Ponce, 2008).

Amongst the main characteristics of the model, focusing on the student as an active learner and the teacher as a guide and facilitator is essential. On the one hand, the students construct their own knowledge on the basis of the comprehensive input received. On the other hand, the faculty members are challenged to teach using a new model that differs significantly from the traditional model with a focus on objective-based teaching. The traditional model negatively impacts the use of strategies that enable the development of the pedagogical content knowledge of students. By contrast, the new model adheres to the use of teaching and learning strategies that promote students’ participation and reflection of their own process.

Finally, the new model gives special emphasis on how the undergraduate profile is achieved through different learning progressions throughout the programme. Here the reflection and communication amongst teachers are fundamental, as well as the monitoring of the achievement of performance indicators in specific courses. Pedagogical and content knowledge are integrated in various courses of the curricular plan and shared in strategic courses.

Content and Pedagogical Knowledge Integration

The second main component of this innovation refers to the link between the content and pedagogical knowledge in the courses of the curriculum plan. The curriculum map was designed following a backward design in which the goals and assessments were developed first (Wiggins and McTighe, 2010), and from that starting point, the competencies the programme will emphasise were stated on the basis of the national standards in initial teacher training in Chile. In addition, the results of an online survey applied to English teachers, the results of focus groups with participation from the key actors of the community and the analysis of national and international research on English teacher education were included in the design of the programme. Thereafter, three main streams were identified as the key elements of the programme, and finally the modules (courses) were created considering the learning progression of the lines and interdisciplinary coherence in the curriculum.

The learning progression of the three streams and the interdisciplinary coherence of the proposal were designed according to Shulman (1986), who shaped the concept of pedagogical content knowledge that represents a blending of content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge. The former refers to the knowledge of the subject matter, e.g. in this case, linguistics and English, whilst the latter refers to the knowledge of pedagogy, e.g. teaching approaches, assessment and theories of learning, amongst others. This blending was created to promote the ability of teachers to understand how to help students effectively appropriate specific themes or issues through reflective instruction. Hence, pedagogical content knowledge encourages teachers’ reflection on how the subject matter is transformed for teaching as a way of interpreting it and making it more accessible for students. Therefore, programmes should combine content and pedagogy into a blend of pedagogical content knowledge.

The previous classification has been modified or adjusted by different authors. Ball, Thames and Phelps (2008) described the subcategories of content knowledge: common content knowledge (such conventions of language: vocabulary, grammar and formulaic sequences), specialised content knowledge (the ability to explain and know why the conventions of language are like that), knowledge of content and students and knowledge of content and teaching. Similarly, Freeman (2016) coined the term knowledge-for-teaching, which Richards (2017) referred to as content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge and ability and discourse skills. Various authors have proposed their own taxonomies aligned with Shulman’s classification (1986). Although they have given different names and added other concepts, they have kept the emphasis on the importance of knowing how to teach.

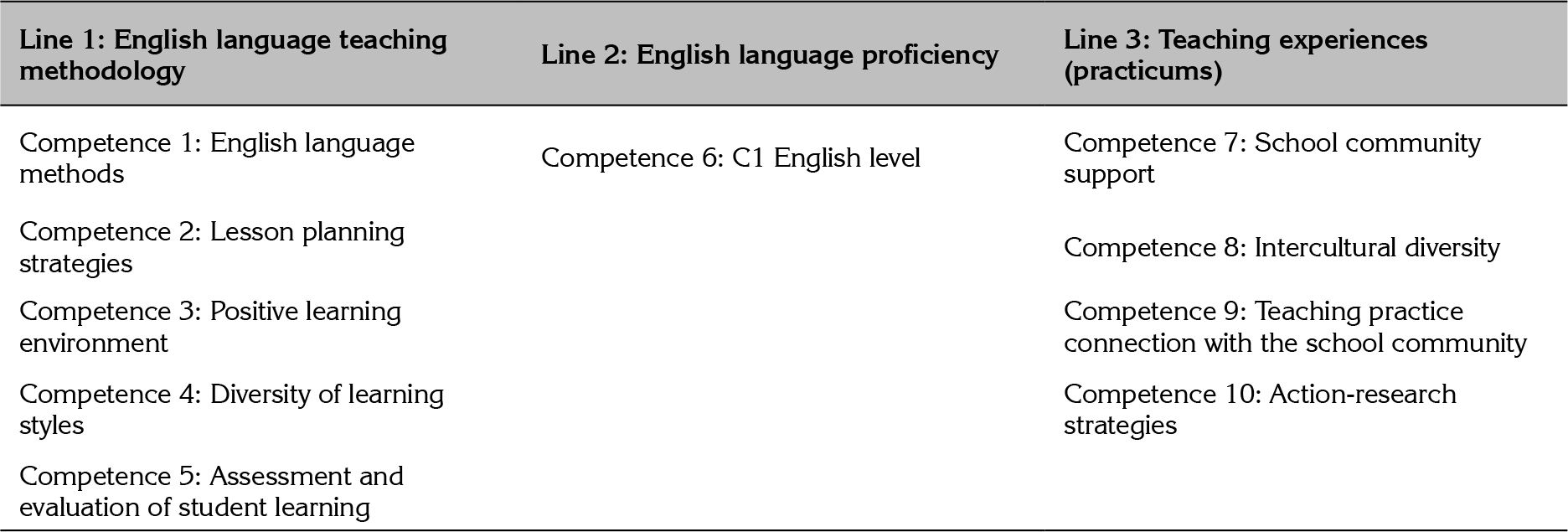

The programme identified 10 competencies grouped according to the following three main lines: 1) English language teaching methodology, 2) English language and 3) teaching experiences (practicums) as shown in Table 3.

Line 1: English language teaching methodology considers modules related to divergent sub-areas of teaching English as a foreign language. This stream starts with a course about children’s literature and finishes with a course on the analysis and creation of resources. The line also considers lesson planning, methods, curriculum, inclusion and assessment. Courses go from the first year (level 2) until the fourth year (level 8). It also includes eight courses in total throughout the programme.

Line 2: English language deals with 21 courses that span nine semesters of study. The programme creates language courses through different content themes, such as cultural studies, world events, universal literature and global issues in education, amongst others. The linguistic components of English (lexico-grammatical aspects, syntax and morphology) are integrated in the language courses inductively. The English stream also includes studies in linguistics, first and second language acquisition and B2 and C1 exam preparation; C1 is a requirement for graduation in the fifth year (five).

Line 3: Teaching experiences (practicums) contains courses related to practicums, i.e. from the observation practicum in the second semester until the professional practicum in the ninth semester. It also incorporates an action-research practicum that reflects the application of the research method modules. Further, the programme adds the homeroom classroom management practicum.

Lines 1 and 3 refer to the pedagogical knowledge and ability (Richards, 2017) of the programme. Line 2 applies to content the knowledge and discourse skill (Richards, 2017) of the programme. In sum, the three lines of the curriculum contribute to the pedagogical content knowledge stated by Shulman (1986).

Table 3: Competencies and lines of the program

The learning progression of the programme was later reflected on the elaboration of the syllabi (course program) and the specific learning outcomes stated for the different levels and modules. The programme was reinforced with the creation of teachers’ guides for all the English courses of the first 2 years to assess the progression of the lines and competencies and to evaluate the curriculum. The innovation was strengthened with the instructors’ methodology adopted to deliver the lessons. This was centred on contemporary teaching methods to reinforce an immersion programme.

Immersion Program

The third component of the innovation was the adoption of an immersion programme focussed on contemporary teaching methods. The main approach adopted was the content and language integration (CLI) proposed by Martel (2013) as a way of linking content-based instruction (CBI) and content and language integrated learning (CLIL). Whilst CBI was initiated in North America, CLIL began in Europe. The former has also been entitled content-based language teaching and ‘designed to embed language instruction in the context of content that is meaningful for learners (Cammarata, Tedick & Osborn, 2016, p. 12). CLIL is considered an approach that implies that content and the language take place simultaneously (Banegas, 2012; Coyle, Hood, Marsh, 2010; Vázquez, Molina & López, 2015). These methods have been employed in different countries (Leyva & Díaz, 2013; Martel, 2013; Cammarata et al., 2016) in second or foreign settings to integrate content and language in the classroom.

CLI intends to promote the learning of a language through content where content and language are at the same level (Martel, 2013). On the one hand, content refers to topics or themes from other areas or disciplines. On the other hand, language refers to structures and linguistic forms that are ‘unpacked from content’ (Martel, 2013, p.1125) and highlighted in classes using divergent linguistic genres. This CLI creates an opportunity of using an authentic language to approximate to language use as it occurs in real contexts.

The application of CLI in this innovation is by following a total immersion programme, which is ‘content-driven’ (Snow, 2014), by essence. Learning a language in a full immersion environment can be overwhelming to Chilean students unaccustomed to being taught in English all day. Therefore, to best support students, the programme highlights two important elements, namely, student-centred and communicative approaches to language learning. Within these elements are the use of scaffolding, collaborative work and active learning.

1. Scaffolding: The core feature of scaffolding is about recognising the different skills/levels of learning readiness that students have and applying strategies that bridge the gap between the target learning outcomes and the abilities of students. Thus, scaffolding can be defined as adding ‘tools, strategies, or guides that support students in gaining higher levels of understanding that would be beyond their reach without this type of guidance’ (Simons & Klein, 2007, p43).

2. Collaborative work: In a collaborative classroom, the teacher focuses on students working together as opposed to working in competition with one another. Students share their knowledge, benefit from the unique skill sets of one another and support one another in the learning process. Nunan (1992) explained that of 41 studies reviewed, 26 showed a positive relationship between higher student outcomes and collaborative strategies employed in the classroom.

3. Communicative strategies: Communicative language teaching (CLT) can be regarded as ‘the engagement of learners in communication to allow them to develop their communicative competence’ (Savignon, 2006, p 673). CLT places emphasis on meaningful opportunities for students to practice using the target language. A key element for CLT to be effective is establishing a safe learning environment with minimal error correction to foster confident speakers.

4. Active learning: Learning is most meaningful when students are able to be active participants in their own learning process. There are many ideas amongst educators of just what constitutes active learning. Bonwell and Eison (1991) explicated the following:

‘…to be actively involved, students must engage in such higher order thinking tasks as analysis, synthesis and evaluation. Within this context, it is proposed that strategies promoting active learning be defined as instructional activities involving students in doing things and thinking about what they are doing’ (p. 2).

By creating a classroom environment that allows students to interact with the target concepts in a concrete way, such as designing visual graphics, writing a reflection, or creating physical models that represent their understanding of core ideas, they tap into a deeper part of long-term memory. In this way, the ideas stay with them and transfer to new contexts more easily.

5. Student-centred strategies: Student-centred learning places the students in the position to self-direct their learning process on the basis of interests, needs and styles of learning. The teachers act as facilitators in the process rather than the controllers of the classroom. The student-centred classroom fosters a climate of ‘whole-person learning, involving cognition and feeling, mind and heart of every individual. It is precisely this acceptant climate and balance of cognition and emotion that is made responsible for their synergetic effects leading to deeper, lifelong learning experiences’ (Motschnig-Patrik and Holzinger; 2002, p 163).

Each of the above practices interacts with and plays off of one another holistically that creates a uniquely supportive learning experience for the students in the teacher preparation programme. The teachers act as guides rather than the keepers of knowledge and put carefully-organised lesson plans into place to minimise the effective filter and encourage learners to view the target language as something fun rather than something to be afraid of or a chore. This first-hand experience with the best practices of language teaching then sets the stage for their future classrooms, as they then later build the strategies into their own lesson planning. In sum, the programme follows an integrative curriculum where the different types of knowledge are combined in the curriculum plan. As previously stated, the programme followed a backward design (Wiggins & McTighe, 2010), and from that starting point, the main lines were identified and supported by different courses. The application of the CLI approach was through an immersion model as the field of foreign language education needs to be characterised as ‘an integrated and balanced focus on meaning and form’ (Cammarata et al., 2016, p. 8) rather than extremely traditional focussed on form, i.e. phonology, grammar and syntax.

Preliminary Results on Implementation

Although the programme is in its fourth year of implementation, some preliminary results could be reported in the English language proficiency and pedagogical knowledge acquisition of the students. Initially, there is evidence of the improvement of the English level of the students after the mid-point progress evaluation applied in the second year. Table 4 exhibits the results obtained by the first and second cohorts of the students.

Table 4: Results of English proficiency in pre and midpoint progress tests

Overall

CEFR grade

Cohort

1

Pre-test

2015

Mid-point

test 2016

progress

Cohort

2

Pre-test

2016

Mid-point

test 2017

progress

A1

0 (0%)

0 (0%)

0 (0%)

0 (0%)

A2

2 (13%)

0 (0%)

5 (20%)

0 (0%)

B1

7 (47%)

0 (0%)

8 (32%)

0 (0%)

B2

6 (40%)

6 (40%)

11 (44%)

12 (48%)

C

0 (0%)

9 (60%)

1 (4%)

13 (52%)

Total

N students

15 (100%)

15 (100%)

25 (100%)

25 (100%)

Table 4 shows that there is an improvement in both cohorts in their final results. If in the pre-test the majority of the student results are gathered on B1 and B2 in both groups, then the student results on the mid-point progress test are grouped on B2 and C. These results corroborate that students are improving in their language skills, and as Tedick (2013, p. 536) claimed, proficiency is ‘an essential prerequisite for effective foreign language teaching because it is not feasible to implement communicative pedagogy or other approaches, such as content-based instruction (CBI), without advanced level proficiency’. Nevertheless, ‘advanced proficiency does not guarantee effective language teaching’ (Tedick, 2013, p. 537) because ‘language proficiency and teaching ability are not the same thing’ (Richards, 2017, p.28).

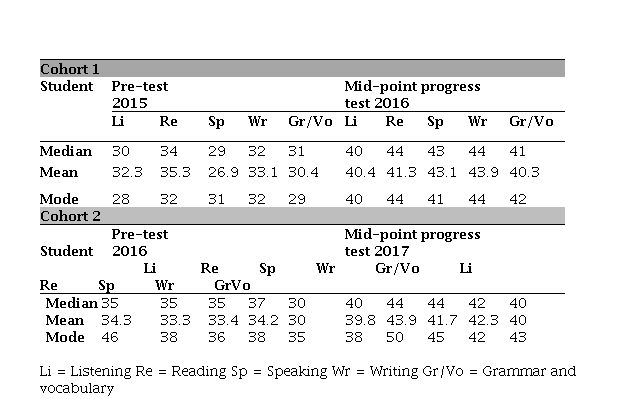

When analysing the student results by component, the results improved significantly in the application of the mid-point progress test in both cohorts. Table 5 presents the basic descriptive statistics.

The improvement in the four language skills is evident as the increase in the student results in the grammar and vocabulary component in both cohorts in the mid-point progress test. The previous results are aligned with what Cammarata and Tedick (2012) confirmed in regard to the results achieved by students being part of immersion programmes who are able to obtain good levels of proficiency in the target language and in standardised English tests. At the same time, when analysing individual grades, the component that showed more improvement in both cohorts was speaking, whilst the weakest component was listening as shown in Table 6.

Table 5: Results by component in pre and midpoint progress tests

It is relevant to mention that the grammar and vocabulary component improved in both cohorts in the mid-point progress test as the average of the pre-test was 30.1 out of 50, whilst the average in the mid-point progress test was 40.2 in both cohorts. In this regard, Mougeon, Nadasdi and Rehner (2010) and Cammarata and Tedick (2012) referred to the fact that the language that students in immersion programmes acquire has insufficient grammatical accuracy, which is probably because of the indirect exposure to the analysis of the target language during the lessons as contrary to more traditional approaches where grammar is studied deductively.

Moreover, the acquisition of pedagogical concepts was reported by the first cohort of students who, in their third year, sat the diagnostic national evaluation (END for its acronym in Spanish). Their results validated that 15 (100%) students attended in contrast with the national attendance that marked 89.6%. Table 7 presents the results.

The results in Table 7 confirm that the institution obtained an average below the national results in the pedagogical knowledge test and an average higher than the national average in the disciplinary and didactics knowledge test. In sum, the student results verify that the programme is attaining the national standards for English programmes.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This work constitutes a significant contribution for developing more innovative pedagogical programmes in the preparation of new English teachers as it integrates pedagogical content knowledge, i.e. English/linguistic knowledge and teaching methodology.

Although this work represents a substantial improvement in English teacher education in Chile, the preliminary evaluation of the implementation displays the need of applying minor changes to improve the proposal. Firstly, minor changes in the curriculum plan should be accomplished; secondly, faculty members and guide teachers of practical experiences should be prepared and thirdly, undergraduate students of the programme should develop resourcefulness skills in regard to their studies.

Table 6: Difference between pre and mid-point progress tests

Listening

Reading

Speaking

Writing Grammar/Vocab.

Mid-point Pre-test progress test

Mid-point Pre-test progress test

Mid-point Pre-test progress test

Mid-point Pre-test progress test

Pre-test

Mid-point progress test

1306 1600

1328 1708

1206 1691

1316 1714

1175

1608

294

Difference

380

485

398

433

Table 7: Results of the diagnostic national evaluation

Test

Description

National

results

University

results

Pedagogical knowledge test (Prueba de Conocimientos Pedagógicos PCP)

A multiple choice test with 50 questions. It is based on the pedagogical national standards for high school education.

101.9

100.8

Disciplinary and didactics knowledge test (Prueba de conocimientos disciplinarios y didácticos PCDD)

A multiple choice test with 60 questions. It is based on the disciplinary national standards for English pedagogy.

101.8

104.9

The proposed changes in the original academic schedule have to do with the inclusion of a course about pedagogical grammar and strengthen the linguistic line of the programme. Considering that grammar is taught inductively in a language integrated model, it could be challenging for foreign language adults, as they should have more direct grammar instruction to understand the language rules because ‘adolescents and adults draw more on language-analytic aptitude (aptitude for explicit learning) and working memory’ (DeKeyser, 2018, p.2). Therefore, the language stream was reinforced with the implementation of tasks that develop sequential grammar structures pertinent to the level by using short clinics that seek to analyse the linguistic structure and offer practice opportunities to the learners. Likewise, the pedagogy of grammar course aims at providing explicit strategies to develop language structures with learners in a model based on CLI.

To implement this new perspective of English teacher education in Chilean universities, faculty members should be prepared for accepting this shift from a more traditional view to a more integrated or innovative way of teacher preparation and then applying this new approach properly into their own teaching practice. In this regard, Wilkinson (2018) argued that strengthening the linguistic competence of the faculty is not the only aspect to bear in mind in teacher preparation, but it is ‘explicit training in methodology of teaching content through English’ (p.611) that is indispensable. Thus, instructors who are part of the programme need explicit training in methodology related to the model (Dafouz, 2018; O’Dowd, 2018; Martel, 2013, Abrahams & Farias, 2010), training which in many cases will tend to lead to a change in teaching methodology (Dafouz, 2018).

Connected to the previous idea, the guide teachers of the practicum experiences should be trained in specific strategies to implement a CLI method in their teaching reality or at least understand and accept the inclusion of new methodologies during the intervention of pre-service teachers in their schools. This preparation for mentor teachers must start through continuous teacher development workshops and move on to something more systematic and elaborated, such as a diploma for practicum guide teachers. This preparation is crucial as practicum experiences constitute a crucial element for pedagogy students as they apply the strategies and methodologies they discuss and develop in the university in real contexts.

Finally, undergraduate students who are part of the programme, or similar ones, must be fully committed to the model as it requires more time investment. This is realised by visiting the library to find appropriate books and new studies in the area and using the current tools in the media and technology, amongst others. Our experience with pre-service teachers shows us that a vast majority of Chilean students are accustomed to receiving all input from the instructor and not showing autonomy in finding new resources, such as movies, music and virtual applications, to facilitate the acquisition of the foreign language. We consider this element necessary to modernise English teacher education in Chile.

As for the limitations of the study, the fact that the programme is new is an element to consider. Hitherto, the programme does not have alumni as the first cohort of students is expected to graduate in 2019. Therefore, the results of these new teachers will be observed in the coming years. Similarly, the acceptance of the educational authorities of these new teachers and the teacher performance are just conjectures as graduates should start developing their own careers. Moreover, the results analysed in this work are based on the results of two cohorts only and represent the pre and mid-point progress tests. Therefore, the results should be analysed in the near future when more cohorts have taken the final evaluation to broaden the sample.

For further research, more emphasis should be given to the integration of not only the English language preparation but also pedagogical areas, such as history of education, pedagogical sciences and learning theories, amongst others, as complementing the learning process of the future educators. The existing divorce between English and pedagogy should be fixed and advance towards more integration of departments (linguistics/English and education/pedagogy or similar) in teacher training. Furthermore, new policies related to EFL in Chile should be established to strengthen the acquisition of English, and CLI should be promoted for primary and secondary education.

A final thought has to do with the necessity of recognising that English proficiency does not mean effective language teaching (Tedick, 2013); it is the use of appropriate pedagogical strategies, accompanied with an effective use of the target language based on the needs of the learners and according to their level. As Richards (2017, p.8) claimed although ‘most of the world’s language teachers do not have nor need a native-like ability in their teaching language to teach their language well: they need to be able to teach with the language, which is not the same thing.’ Undergraduate English teacher preparation programmes should reflect both elements: language proficiency and teaching methodologies; the use of an English immersion programme based on CLI guarantees the inclusion and attainment of both elements. The inclusion of these elements in the curricula of English teacher preparation in Chile will definitely promote the modernisation of English teacher education in Chile.

References

Notes

Metrics

License

Copyright (c) 2020 Eric Gómez Burgos, Wanda Walker

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.