DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.14670Publicado:

2019-04-23Número:

Vol. 21 Núm. 1 (2019): Enero-junioSección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónA comparative study of Mexican and Irish compliment responses

Un estudio comparativo de las respuestas a cumplidos producidas por hablantes del español de México y del Inglés de Irlanda

Palabras clave:

cumplido, respuesta a un cumplido, imagen, cortesía, español mexicano, inglés, irlandés (es).Palabras clave:

compliment, compliment response, face, Irish English, Mexican Spanish, politeness (en).Descargas

Referencias

Baba, J. (1997). A study of interlanguage pragmatics: compliment responses by learners of Japanese and English as a second language. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Texas at Austin.

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice: Designing and developing useful language tests. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bernal, M. (2005). Hacia una categorización sociopragmática de la cortesía, la descortesía y la anticortesía. In D. Bravo (Ed.), Estudios de la (des)cortesía en Español: Categorías conceptuales y aplicaciones a corpora orales y escritos (pp. 365-398). Estocolmo-Buenos Aires: DUNKEN.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language use. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press.

Curcó, C. (2007). Positive face, group face and affiliation: An overview of politeness studies on Mexican Spanish. In M.E. Placencia & C. García (Eds.), Research on politeness in the Spanish speaking world (pp. 105-120). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum.

Chen, R. (1993). Responding to compliments. A contrastive study of politeness strategies between American English and Chinese speakers. Journal of Pragmatics, 20, 49-75.

Chen, R., & Yang, D. (2010). Responding to compliments in Chinese, has it changed? Journal of Pragmatics, 42, 1951-1963.

Daikuhara, M. (1986). A study of compliments from a cross-cultural perspective: Japanese vs American English. Penn Working Papers in Educational Linguistics, 2, 23-41.

Farghal, M., & Al-Khatib, M. A. (2001). Jordanian college students’ responses to compliments: a pilot study. Journal of Pragmatics , 33(9), 1485-1502.

Farghal, M., & Haggan, M. (2006). Compliment behavior in bilingual Kuwaiti college students. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(1), 94-118.

Félix-Brasdefer, C. (2003). Validity in data collection methods in pragmatic research: Theory, practice and acquisition. In P. Kempehinsky & C. Piñeros (Eds.), Papers from the 6th Hispanisc and Linguistic Symposium and the 5th Conference on the acquisition of Spanish and Portuguese (pp. 239-257). Somerville. MA: Cascadilla Press.

Félix-Brasdefer, C. (2009). Estado de la cuestión sobre el discurso de la (des) cortesía y la imagen social en México. In L. Rodríguez Alfano (Ed.), La (des) cortesía y la imagen social en México: Estudios semiótico discursivos desde varios enfoques analíticos (pp. 15-46). Monterrey, Nuevo León: Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.

Flores-Salgado, E., & Castineira-Benitez, T. A. (2018). The use of politeness in WhatsApp discourse and move ‘requests.’ Journal of Pragmatics , 133, 79-92.

Fukushima, N. J. (1990). A study of Japanese communication: compliment-rejection production and second language instruction (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Southern California.

Gajaseni, C. (1995). A contrastive study of compliment responses in American English and Thai including the effect of gender and social status (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Illinois.

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face behavior. New York, NY: Doubleday Anchor books.

Golato, A. (2002). German compliment responses. Journal of Pragmatics , 34, 547-571.

Grindsted, A. (1994). La organización del espacio interactivo en negociaciones mexicanas, españolas y danesas. Discurso, 16, 17-50.

Han, C.-H. (1992). A comparative study of compliment responses: Korean females in Korean interactions and in English interactions. Working Papers in Educational Linguistics, 8(2), 17-31.

Herbert, R. K. (1986). Say “Thank you”-or something. American Speech, 61, 76-78.

Herbert, R. K. (1989). The ethnography of English compliments and compliment responses: A contrastive sketch. In W. Olesky (Ed.), Contrastive pragmatics (pp. 3-35). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Herbert, R. K. (1990). Sex-based differences in compliment behavior. Language in Society, 19, 201-224.

Herbert, R. K. (1991). The sociology of compliment work: An ethnocontrastive study of Polish and English compliments. Multilingua, 10, 381-402.

Holmes, J. (1988). Compliment and compliment responses in New Zeland English. Antropological Linguistics, 28(4), 485-508.

Holmes, J., & Brown, D. F. (1987). Teachers and students learning about compliments. TESOL Quarterly, 21, 523-546.

Jaworski, A. (1995). ‘‘This is not an empty compliment!’’ Polish compliments and the expression of solidarity. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5, 63-94.

Kallen, J. L. (2005). Silence and mitigation in Irish English Discourse. In A. Barron. & K. P. Schneider (Eds.), Trends in linguistics: Pragmatics of Irish English (pp. 47-71). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kasper, G. (2000). Data collection in pragmatic research. In H. Spencer-Oatey (Ed.), Culturally speaking: Managing rapport through talk across cultures (pp. 316-369). London, U.K: Continuum.

Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. (1996). La conversation. Paris: Seuil.

Lakoff, R. (1973). The logic of politeness; or, minding your p’s and q’s. In C. Corum, S. Cedric, & A. Weiser (Eds.), Papers from the ninth regional meeting, Chicago Linguistic Society (pp. 292-305). Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.

Leech, G. N. (1983). Principles of pragmatics. London: Longman.

Lorenzo-Dus, N. (2001). Compliment responses among British and Spanish university students: a contrastive study. Journal of Pragmatics , 33, 107-127.

Manes, J. (1983). Compliments: A mirror of cultural values. In N. Wolfson & E. Judss (Eds.). Sociolinguistics and language acquisition (pp. 96-102). Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers.

Migdadi, F. H. (2003). Complimenting in Jordanian Arabic: A socio-pragmatic analysis (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Ball State University.

Mustapha, A. S. (2004). Gender variation in Nigerian English compliments (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Essex.

Nelson, G., El Bakary, W., & Mahmoud, A.-B. (1993). Egyptian and American compliments: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 17, 293-313.

Nelson, G., Al-Batal, M., & Echols, E. (1996). Arabic and English compliment responses: Potential for pragmatic failure. Applied Linguistics, 17, 411-432.

O’Reilly, C.. (2003). The expatriate life: A study of German expatriates and their spouses in Ireland. Issues in adjustment and training. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Pomerantz, A. (1978). Compliment responses: notes on the cooperation of multiple constraints. In J. Schenkein (Ed.), Studies in the organization of conversational interaction (pp. 79-112). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. Maxwell Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action (pp. 57-101). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ruhi, S. (2006). Politeness in compliment responses: A perspective from naturally occurring exchanges in Turkish. Pragmatics, 16(6), 43-101.

Ruhi, S. (2007). Higher-order intentions and self-politeness in evaluations of (im)politeness: The relevance of compliment responses. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 27(2), 107-145.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50, 696-735.

Saito, H., & Beecken, M. (1997). An approach to instruction of pragmatic aspects: Implications of pragmatic transfer by American learners of Japanese. The Modern Language Journal 81, 363-377.

Schneider, K. P. (1999). Compliment responses across cultures. In M. Wysocka (Ed.), On language theory and practice. In Honor of Janusz Arabski on the occasion of his 60th birthday (pp. 162-172). Katowice: Wydawnictwo Universytetu Slaskiego.

Schneider, K .P. & Schneider, I. (2000). Beschedenheit in veir Kulturen: Komplimenterwiderungen in des USA, Irland, Deutschland und China. In M. Skog-Södersved (Ed.), Ethische Konzepte und mentale kulturen 2: Sprachwissen-schaftliche sudien zu höflichkeit als respektverhalten (pp. 65-80). Vaasan Yliopisto, Vaasa.

Sharifian, F. (2005). The Persian cultural schema of shekasteh-nafsi: A study of compliment responses in Persian and Anglo-Australian speakers. Pragmaticsand Cognition, 13(2), 337-361.

Spencer-Oatey, H., & Ng, P. (2001). Reconsidering Chinese modesty: Hong Kong and Mainland Chinese evaluative judgments of compliment responses. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 11(2), 181-201.

Tang, C.-H., & Zhang, G. Q. (2009). A contrastive study of compliment responses among Australian English and Mandarin Chinese speakers. Journal of Pragmatics , 41(2), 325-345.

Valdés, G., & Pino, C. (1981). Muy a tus ordenes: Compliment responses among Mexican-American bilinguals. Language in society, 10, 53-72.

Watts, R. (2003). Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wolfson, N. (1983). An empirically based analysis of complimenting in American English. In N. Wolfson & E. Judd (Eds.), Sociolinguistics and language acquisition (pp. 82-95). Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers .

Yu, M.-C. (1999). Cross-cultural and interlanguage pragmatics: Developing communicative competence in a second language (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Harvard University.

Yu, M.-C. ( 2004). Interlinguistic variation and similarity in second language speech act behavior. The Modern Language Journal, 88(1), 102-119.

Yuan, L. ( 2002). Compliments and compliments responses in Kunming Chinese. Journal of Pragmatics , 12(2), 183-226.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Recibido: 30 de septiembre de 2018; Aceptado: 29 de marzo de 2019

Abstract

The purpose of the present study is to compare the compliment responses (CRs) provided by 60 native Mexican Spanish speakers and 60 Irish English native speakers. Using a discourse completion task, 1080 responses were analyzed based on Herbert’s (1989) and Nelson, El Bakary and Al-Batal’s (1993) taxonomy. Findings suggest the existence of cross-cultural similarities in Irish and Mexican CRs in the frequency of deflecting comments and the mechanisms that are used to redirect the praise force. Second, the two languages differ in important ways. In responding to compliments, Irish recipients are much more likely than Mexican speakers to use a single strategy when formulating CRs. The findings further show that social factors (social distance, social power, gender, and the topic of the compliment) in both Mexican and Irish society seem to be crucial parameters in the formulation and acceptance or rejection of a compliment.

Keywords:

compliment, compliment response, face, Irish English, Mexican Spanish, politeness.Resumen

El propósito del presente estudio fue comparar las respuestas a cumplidos (RC) producidas por 60 hablantes nativos de español de México y 60 hablantes nativos de inglés de Irlanda. La base de datos se recabó mediante un instrumento llamadodiscourse completion task, el cual permitió obtener 1080 respuestas, las cuales se analizaron usando la taxonomía propuesta por Herbert (1989) y Nelson, El Bakary y Al-Batal (1993). Los resultados muestran tres aspectos importantes. El primer resultado sugiere la existencia de similitudes entre las RCs irlandesas y mexicanas con respecto al empleo de estrategias de mitigación con el propósito de desviar los comentarios y redirigir el cumplido. En segundo lugar, los dos grupos difieren en aspectos importantes. Al responder a los cumplidos, los destinatarios irlandeses son mucho más propensos que los hablantes mexicanos a usar una sola estrategia, mientras que los mexicanos utilizan dos o más para formular las RCs. Los resultados muestran además que los factores sociales (distancia social, poder social, género y el tema del cumplido) en la sociedad mexicana y en la irlandesa parecen ser parámetros cruciales en la formulación y aceptación o rechazo de un cumplido.

Palabras clave:

cumplido, respuesta a un cumplido, imagen, cortesía, español mexicano, inglés irlandés.Introduction

A compliment response (CR) is defined as an expressive speech act and preferred social act that is structurally expected by the speaker. A compliment response is part of a speech event that has the structure of an adjacency pair (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1974) or an “action chain event” (Pomerantz, 1978, p. 109) that consists of two sequences-a compliment (C) and a compliment response (CR)-connected by temporal and relevancy conditions (Herbert, 1990). Compliments and compliment responses are speech acts that are linked in important ways. In order to understand a compliment response, it is necessary to understand the whole compliment event. According to Manes (1983), compliments and compliment responses provide a “mirror of cultural values” (p. 96) because they show how speakers react to external appraisals of their personal and social identity. Knowing how to give a compliment is as important as knowing how to respond to one. The literature on compliment responses has empirically examined various aspects (e.g., cross-cultural comparisons, analyses of this speech act in different socio-cultural contexts, and comparisons of naturally occurring compliment responses by native speakers in intercultural contexts) in diverse languages and in diverse varieties of English as well as some varieties of Spanish. This literature includes studies of American English (Herbert, 1986, 1990; Manes, 1983; Pomerantz, 1978, 1984; Wolfson, 1983), South African English (Herbert, 1989), New Zealand English, (Holmes, 1988), Irish English (Schneider & Schneider, 2000), Nigerian English (Mustapha, 2004); Polish (Herbert, 1991; Jaworski, 1995); German (Golato, 2002); Turkish (Ruhi, 2006), Persian (Sharifian, 2005), Jordanian Arabic (Farghal & Al-Kkatib, 2001; Migdadi, 2003), Kuwait Arabic (Farghal & Haggan, 2006), Syrian Arabic (Nelson, Al-Batal, & Echos, 1996), Japanese (Daikuhara, 1986; Baba, 1997; Fukushima, 1990; Saito & Beecken, 1997), Korean (Han, 1992), Thai (Gajaseni, 1995), Chinese (Chen; 1993; Chen & Yang, 2010; Spencer-Oatey & Ng, 2001; Tang & Zhang, 2009; Yu, 1999, 2004; Yuan, 2002), Peninsular Spanish (Lorenzo-Dus, 2001), and Mexican-American Spanish (Valdés & Pino, 1981). Overall, these studies provide useful information about what factors are most likely to provoke compliments, the contextual factors involved, the values and norms that govern the selection of the strategies, and the syntactic and conversational structures that are most often used to form compliment responses. These studies demonstrate that compliment responses vary culturally in terms of the types of strategies that are used to accomplish them in a given situation.

While most of the above studies focus on the inventory of compliment strategies, there are few attempts to examine polite behavior and the negotiation of face during compliment interactions. Further, there seems to be agreement in the aforementioned studies in the way CRs are categorized: acceptance, deflection/evasion, and rejection. This tripartite system, which was originally proposed by Holmes (1988) and which implements the insights of Pomerantz’s (1984) theory of conflicting constraints, has been gaining currency. Of the studies mentioned above that were carried out in Spanish, only one examines CRs in Mexican Spanish (Valdés & Pino, 1981) whose focus was to examine a bilingual speech community in the United States. Moreover, the only study mentioned above that analyzes CRs in Irish English (Schneider & Schneider, 2000) focuses its attention on contrasting CRs in Irish and American English. Finally, while there is a body of literature regarding compliment response behavior in various varieties of English (including American, British, New Zealand, and South African), research in Mexican Spanish and Irish English is rather scarce. This demands that the notions of face and politeness need to be further examined in other varieties of these two languages.

Theoretical Considerations

A compliment can reflect a positive or a negative strategy depending upon the particular communicative function that it serves in a particular interaction. Some researchers (Herbert, 1989; Wolfson, 1983) consider that one of the functions of a compliment is to manifest admiration through the expression and acknowledgment of admiration. However, it also may carry out other communicative goals such as to express disapproval, sarcasm (Jaworski, 1995), a request for the complimented object (Herbert, 1991), or reinforce desired behavioral patterns (Manes, 1983). According to the theory proposed by Brown and Levinson (1987), a compliment can be categorized as a face threatening act (FTA) because it represents an assessment in which the speaker is positively evaluating some state of affairs, some object, or some action of one’s interlocutors. This evaluation can be seen as an invasion of his/her negative wants (Lorenzo-Dus, 2001). In contrast, Bernal (2005) considers that a compliment is an act that reinforces the other’s face with the purpose of preserving the speaker’s face and at the same time strengthening interpersonal relations. Following Leech’s (1983) classification, this is a polite act in which the other’s face is not threatened, and its illocutionary objective is the same as the social norms. Based on this, Kerbrat-Orecchioni (1996) classifies it as a face flattering act (FFA) whose purpose is not to repair or compensate the losing face, but to motivate a positive face for interpersonal relations.

Different theoretical orientations of politeness have been adopted to analyze this act. Based on the notion of face proposed by Goffman (1967), Brown and Levinson (1987) construct a universal theory of politeness. These authors define face as a social characteristic of a speaker that can be lost, maintained, or reinforced during linguistic interaction. For Brown and Levinson (1987), in every social interaction every speaker acts in order to show respect for the face wants of the other. This notion of face has two interrelated facets that the speaker can show: a positive face or negative face. Positive face is characterized by the desire of the speaker to be appreciated by the group and be part of the group. On the other hand, negative face is understood as the desire not to be imposed on by others, to be independent and autonomous. This theory is speech-act based and Brown and Levinson suggest that certain speech acts are face threatening acts (FTA) that potentially threaten the faces of the speaker and/or hearer. As a consequence, the task of the speaker is to select the most efficient means of achieving a particular end. Politeness strategies are used to reduce the particular face threat. There are two types of strategies-positive and negative- which are selected according to the type of face that is threatened. Thus, the appropriate selection of the politeness strategy will preserve the speaker’s face.

Brown and Levinson’s (1987) theory can be considered as one of the most influential for examining CRs. Using Herbert’s (1989) taxonomy of compliment responses, Lorenzo-Dus (2001) analyzes this act in terms of the type of politeness used by British English and Peninsular Spanish males and females. The data were collected by means of a DCT. Lorenzo-Dus (2001) finds a considerable degree of cross-cultural affinity between the two cultures. The use of reassignments reveal the tendency in both cultures to avoid self-praise on topics such as natural talent and intelligence. However, there are also cross-cultural and cross-gender differences. One difference between British and Spanish speakers is the use of irony and humor as upgraders. Spanish males tend to upgrade compliments ironically more frequently than females. This type of strategy is never used by British speakers. Another difference is the tendency to question the truth value of the compliments and consequently the relational solidarity of their complimenter. The British participants employ this strategy more than their Spanish counterparts.

Interest in politeness phenomena in Mexico dates back to the first publication of Brown and Levinson’s (1987) model. However, most of the studies conducted in Mexico do not refer to Spanish (the official language), instead concentrating on the analysis of the indigenous languages still spoken in Mexico (Curcó, 2007). The literature on compliment responses in Mexican Spanish that does focus on verbal polite behavior is rather scarce. Valdés and Pino (1981) analyze how a bilingual setting affects the rules of politeness, whether certain culturally determined constraints are disregarded and others incorporated, and the verbal strategies through which a balance is achieved. They compare compliment responses among three groups of participants: Spanish speaking monolinguals living in Mexico (in the Mexican state of Chihuahua), English speaking monolinguals residing in the United States, and Mexican-American bilinguals from southern Mexico. The results show that Mexicans and Americans employed the same patterns of acceptance and rejections. However, Mexicans used certain patterns only with intimates or only with strangers and also employed alternative strategies and sub-strategies not found in the speech used by the Americans. Using the rules of politeness proposed by Lakoff (1973), Valdés and Pino (1981) conclude that Mexicans display a greater use of Lakoff’s Rule 1 ‘don’t impose’-which is related to Brown and Levinson’s (1987) concept of negative face-because Mexican society is highly stratified. In contrast, the norm in the American group was the use of Lakoff’s Rule 3 ‘be friendly,’ the equivalent of positive face in Brown and Levinson’s (1987) theory. With respect to Mexican American bilinguals, they show a tendency to treat others as if they were close friends. This result shows that attention is given to the positive face of the hearer. Even though Valdés and Pino (1981) analyze Spanish, their study is not focused on monolingual speech, but on the speech of Mexican-American bilinguals.

Leech’s (1983) conversational-maxim view of politeness has also been employed to analyze CRs. Leech (1983) proposes a politeness principle that reads: “Minimize (other things being equal) the expression of impolite beliefs… maximize (other things being equal) the expression of polite beliefs” (p. 81). This principle is divided into sub-principles or maxims: tact, generosity, approbation, modesty, agreement, and sympathy. Leech’s maxims are associated with particular illocutionary forces. Since a compliment response is an expressive act, the maxims related to this illocution are modesty and agreement. Cross-cultural research has shown that different maxims are given different weight in different cultures.

Schneider (1999) contrasts CR in Irish and American English. He does not use Brown and Levinson’s (1987) model in his analysis, instead preferring the conversational maxim proposed by Leech (1983). However, it should be stressed that his results can be recast in terms of negative and positive politeness face work. He finds that Irish speakers give equal importance to the agreement and modesty maxims, which is in contrast to American English where the agreement maxim is the most valued. Another result shows that Americans are found to prefer an accepting strategy over all other strategies whereas the Irish informants’ first preference is for a rejecting strategy. The preference for rejections serves to minimize the impact of the compliment itself and indicates the need to be independent, which reinforces Brown and Levinson’s (1987) definition of negative face. This is in contrast to the Americans for whom agreement, oriented toward the interlocutor’s positive face in terms of Brown and Levinson (1987), seems to be the norm.

Watts’ (2003) framework has provided another perspective into politeness within the Mexican context. Empirical research by Watts (2003) demonstrates that (im)politeness is a social practice that is both dynamic and flexible, allowing speakers to shift their behaviors in order to be appropriate according to particular sociocultural contexts. Watts (2003) defines two types of behavior in this respect: politic and (im)polite. Politic behavior can be characterized as unmarked linguistic and non-linguistic constructions that take place during particular social practices. The appropriacy of politic behaviors is determined according to the specific interactions that the social practices govern based on speakers’ previous experiences with similar practice and objectified social structures. Politic behaviors reflect the principles that preside over everyday interactions. Flores-Salgado and Castineria-Benitez (2018) provide an example of politic behavior when pointing out that “in Mexico, ‘usted’ is used to address a person older than the interlocutor without considering his/her social hierarchy within the communicative situation. This politic behavior can be understood in terms of respeto (consideration and respect towards others)” (p. 82).

Polite behavior, on the other hand, is marked and goes beyond conventional social expectations (positively or negatively) in regards to that which might be perceived as appropriate within an ongoing social interaction (Watts, 2003). Such behavior represents a more interpersonal and negotiatory dimension within social interaction and is perceived as polite or impolite depending on whether the marked behavior is considered appropriate or inappropriate within the social context. Félix-Brasdefer (2009) characterizes polite behavior as a linguistic and non-linguistic phenomenon that is meant to facilitate the negotiation of face during communication. It is a social strategy employed in order to help accomplish communicative goals. Polite behavior is contingent on the social presuppositions of interlocutors as well as the social (including power) relations involved in the negotiation of communicative interactions. In Mexico, polite behavior is reflected by perceived investment in the speech event, the creation of solidarity among interlocutors by placing the interlocutor at the center of the interaction while placing the self on the periphery (Curcó, 2007; Félix-Brasdefer, 2009; Grindsted, 1994). As such, it is difficult for a Mexican speaker to engage in certain kinds of speech acts such as carrying out a refusal, engaging in open criticism of others, or even accepting a compliment due to a preoccupation with safeguarding the addressee’s face (Flores-Salgado & Castineira-Benitez, 2018).

To date, research on CRs analyzing politeness behavior in Mexican Spanish and Irish English is scarce and the few studies that have been conducted exhibit a great variety of both theories and topics. As such, the present paper is concerned with three main aspects: contrastive analysis from a pragmatic perspective on compliment responses in Mexican Spanish and Irish English as they are used by Mexican and Irish college students. Secondly, it is concerned with the pragmatic implications of the social usage that speakers make of their language in relation to the linguistic phenomenon of politeness. Finally, this study examines socio-linguistic features, particularly the attitudes and values attached to compliment behavior in both cultures. The specific questions to be addressed are:

-

What are the similarities between Mexican Spanish speakers and Irish English speakers in their use of compliment responses?

-

What are the differences between Mexican Spanish speakers and Irish English speakers in their use of compliment responses?

-

What are the sociopragmatic constraints that govern the selection of these forms?

Methods

Participants

The 36 students who participated in this study were divided into two groups: 60 native speakers of Mexican Spanish (MS) and 60 native speakers of Irish English (IE). The Mexican Spanish speakers were natives of the state of Puebla, Mexico and shared the same regional Mexican dialect. They were undergraduate students studying English Teaching as a Foreign Language at a public university in Puebla, Mexico. The Irish English speakers were from Dublin, Ireland. They were undergraduate students in their first year of the Science-Computing IT Management program in the department of Computing at an institute of technology in Dublin, Ireland. All participants were asked to participate in a cross-cultural study on the use of CRs, and filled out a background form before agreeing to participate in the study. It was clearly specified that no extra credits in their course would be derived from their participation. Ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 37 years old. With respect to social class, the population of both groups may best be described as representing a continuum from middle to low working class.

Instrument

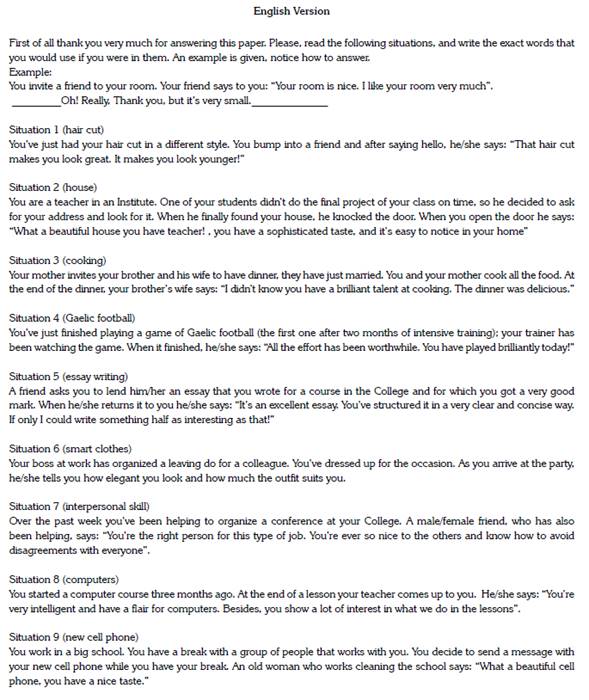

The instrument was a discourse completion task (DCT). While we are fully aware of the weaknesses of DCTs as a data collecting method (see Félix-Brasdefer, 2003; Kasper, 2000), Lorenzo-Dus’ (2001) methodology was followed so as to assure compatibility between the two groups examined in the study.

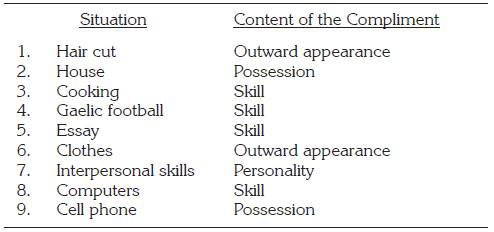

This instrument consisted of incomplete discourse sequences that represented different social situations. There was a short description of each situation that explained the setting, the social distance between the interlocutors and their relative status to each other, followed by an incomplete dialogue (see Appendix A). As seen in Table 1, the compliments represented in the DCT praised the following aspects: outward appearance, personality, skill/work, and possession.

Table 1: Situations.

In order to confirm that each situation in the Lorenzo-Dus’ (2001) questionnaire would be socio-culturally convincing to members of the Mexican and Irish culture, the situations were discussed with a number of native speaker college students. Ten native Mexican college students and five native Irish college students were asked to confirm that the sorts of situations represented in the DCT were likely to occur in Mexican and Irish college life. Dialogues that did not prove to be contextually delimited to a sufficient degree were slightly changed, but the social context presented in each item remained intact. Consequently, Situations 2 (brand new car) and 9 (beautiful eyes) were modified. These changes were made because participants in both cultures responded that the scenarios were unfamiliar. Thus, the revised Situation 2 comprised a C on the possession of a house and it was offered by a student to a teacher, while Situation 9 did not refer to appearance and also featured a compliment on possession (cell phone) from one friend to another. Finally, in Situation 4, the noun tennis was replaced by football. This sport was selected because in both cultures, football is more popular than Tennis. The resulting version was pilot-tested with a group of 15 native speakers of Spanish at the BUAP. This version proved to be reliable in eliciting the speech acts under investigation. The pilot data was used to train the coders.

The final version of the DCT in English and Spanish was administered to the respondents. They were informed about the purpose of the study-that we were investigating how Mexican and Irish speakers respond to certain situations-and told to write the exact words that they would use if they were in those situations, taking as much time as they needed. To avoid biasing the subjects’ response choice, the word ‘compliment response’ was not mentioned in the descriptions given in the DCT. The average time to finish the task was approximately 20 minutes. This procedure produced a database of 540 Mexican Spanish and 540 Irish English compliment responses.

Data Analysis

The unit of analysis used to analyze the data was based on the utterance or sequence of utterances supplied by the informant in responding to the compliment. The project’s coding scheme was based on the frames of primary features expected to be manifested in the realization of compliment responses, proposed by Holmes (1988), Herbert (1988), and Nelson, Mahmoud, and Echols (1996). New strategies were created for those CRs that did not fit any of the models originally proposed. These strategies were then grouped into the three broad categories: accepting, mitigating/deflecting/evading, and rejecting. This taxonomy, which has the advantage of being theory neutral (Chen & Yang, 2010), was used in this study as a basis for comparing CRs across these two languages.

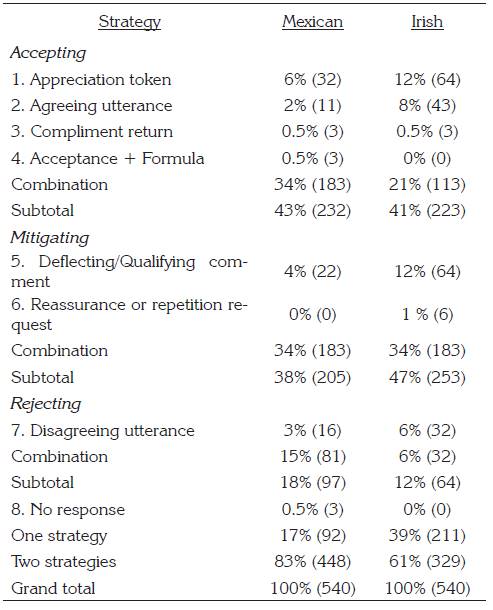

The compliment response strategies include accepting (consisting of four subcategories: appreciation token, agreeing utterance, compliment return, and acceptance formula), mitigating (consisting of two sub-strategies: deflecting or qualifying comment, reassurance or repetition request), and rejecting (disagreeing utterance and no response). Each of the responses was coded into one of these categories, and the frequencies of responses within each main category were then obtained. The frequencies of these strategies are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Coding

The Spanish CRs were coded by three Mexican Spanish speakers and the English CRs by three Irish English native speakers, within a shared analytical framework. The Mexican Spanish coders were one of the researchers and two undergraduate research assistants majoring in Teaching English as a Foreign Language, while the Irish English coders were graduate students of the computing program at the institute of technology in Dublin. The coders were trained by the researchers. First the trainer explained each of the categories contained in the coding scheme, providing examples to support the explanation. Then the trainer instructed them to (1) read carefully each CR and analyze each part of it, and (2) choose the category that best fit each situation. After that, each coder practiced with 10 samples. In order to facilitate the analysis of these results, the trainer gave each coder note cards and instructed them to write each interaction on a separate card. The coders worked independently and coded all the CRs. This produced a 90% inter-coder agreement.

Findings

This section presents the analysis of the Mexican and Irish compliment responses, grouped into eight strategies. These eight strategies were then grouped into the three categories we discussed in the last section: accepting, mitigating, and rejecting. Under each of these categories, we also find a great number of CRs that combine two or more strategies. They are grouped under ‘‘combination.’’ The frequencies of these strategies are presented in Table 2. Below, we provide examples of these strategies to prepare for the discussion of the most important findings of the study-that Mexican subjects use two strategies more often (83%) than Irish participants (61%).

Table 2: Mexican and Irish compliment response (one strategy).

As is seen in Table 2, the two groups bear several important resemblances. First, the percentages in the frequency of occurrence for each of the three categories are somewhat similar: Irish subjects, for instance, mitigate compliments 47% of the time while Mexicans mitigate them 38% of the time. Irish subjects accept compliments 41% and Mexicans 43% of the time. The last category, rejecting, is used by Irish participants with a frequency of 12% while that figure for the Mexicans is 18% However, there are important differences. The frequency of the use of a single strategy in the Mexican corpus is 17% lower than the frequency of the use of single strategy in the Irish data (39%). Secondly, the order of preference the subjects reported is different in each group: Irish subjects are found to most favor mitigating, followed by accepting, with rejecting as the least favored category of strategies, while Mexicans prefer accepting overall, followed by mitigating and rejecting.

Acceptance

As can be seen in Table 2, the acceptance category accounts for nine percent of the Mexican compliment responses and twenty percent of the Irish responses.

Appreciation token. This is the most common response type in the acceptance category. This type of response only contains expressions that can be used to carry out a direct compliment response such as Gracias [Thank you] or with an adverbial upgrader as Muchas gracias [Thank you very much]. Appreciation tokens accounts for 6% of the Mexican compliment responses and 12% of the Irish responses in the sample.

(1) Muchas gracias. (MS13, S61) [Thank you very much!]

(2) Thank you! (IE2, S12)

Agreeing utterance. These are responses that are semantically connected with the content of the compliment given. They occur in 2% of the Mexican responses and 8% of the Irish compliment responses.

(3) Es herencia de familia. (MS11, S3) [It is a family gift.]

(4) Yeah, I like doing this type of work. (IE2, S7)

Compliment return. This response strengthens the bonds that exist between the interlocutors-to answer with another compliment consolidates the solidarity between the speaker and the addressee. In addition, this response allows the recipient to maintain equality in the relationship. This compliment response type occurs infrequently within the present corpus, in just three exchanges or approximately 0.5% of the Mexican sample and three exchanges or 0.5% of the Irish responses.

(5) Igualmente. (MS16, S6) [You look nice too.]

(6) Cheers, You look well yourself. (IE4, S6)

Acceptance + Formula. This type of response is characterized by the use of a formulaic utterance such as A la orden, cuando gustes, cuando quieras, that is commonly used to respond to compliments that refer to possessions (objects) or skill. The responses offer the object or ability being complimented on to the complimenter without meaning it. These responses simply fulfill a particular social function, as can be observed in (7). It is interesting to mention that this response is the most common compliment response employed by Syrian Arabic speakers (Nelson et al., 1996). It occurs infrequently in the Mexican responses (0.5%) and it does not occur at all in the Irish data.

(7) Muy a la orden. (MS18, S9) [Anytime you like.]

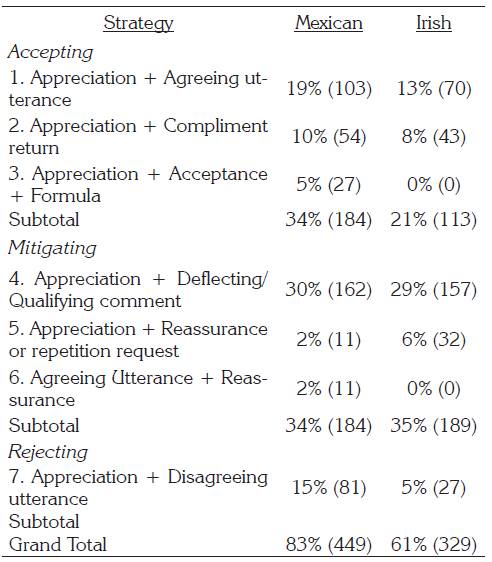

Combination strategies under accepting. The four strategies under accepting are frequently combined. As can be seen in Table 3, 34% (n = 184) of the Mexican compliment responses and 21% of the Irish responses comprise combinations taken from this category. These results coincide with previous literature in that accepting is the most preferred strategy in other languages (Golato, 2002; Nelson et al., 1996).

Table 3: Combination of Compliment Strategies used by Mexican and Irish Speakers.

Eighty-three percent of the Mexican and 61% of the Irish responses to a compliment combine two strategies. Almost all the combinations of both sample groups include the strategy appreciation token, as can be seen in Table 3. These appreciation tokens are uttered in conjunction with a second assessment that is either in agreement with the first assessment or in rejection of it.

Appreciation token and agreeing utterance. As seen in Table 3, 19% of the Mexican Spanish CRs use appreciation tokens (Gracias [thank you]) and a positive comment that accepts the C. In the Irish data, this combination is slightly less frequent (13%). In the case of Situations 8 and 9, it can be seen that the responses show that the participants accept the speaker’s evaluation in the form of an agreement.

(8) Muchas gracias! Me tomo mucho tiempo para esto. (MS9, S4) [Thank you very much! It took me a lot of time to do it.]

(9) Thank you! I think so too. (IE8, S1)

Appreciation token and compliment return. As illustrated below, this combination is characterized by the use of the statement of appreciation and another compliment for the original sender. Ten percent of the Mexican and 8% of the Irish CRs employ it.

(10) Gracias, usted también se ve muy bien. (MS20, S6) [Thank you, you look great too.]

(11) Thanks, I think your outfit is nice too. (IE7, S6)

Appreciation token and acceptance + formula. This combination includes the statement of appreciation and a ritualistic formula as shown in (12). This type of response does not occur at all in the Irish sample, but occurs in the Mexican data (5%).

(12) Gracias, muy a la orden. (MS12, S9) [Thank you, anytime you’d like.]

Mitigating responses. This category includes two sub-categories that share the same characteristics: non-acceptance and non-rejection of the compliment. These responses ignore, question, or deflect the compliments.

Deflecting/qualifying comment. As can be seen in Table 2, deflecting comments are the most common pragmatic strategy use by the Irish (12%), while only 4% of the Mexican group use them. This is an indirect form of rejecting a compliment. Indirectness is one characteristic of Irish culture (Kallen, 2005; O’Reilly, 2003) that participants probably use in this study to solve the conflict of accepting self-praise. Different forms are used to deflect a compliment; the most common means used by Irish and Mexican participants is a referent shift. The credit is given to someone (a third party) or something else. This form allows the avoidance of self-praise on topics such as skill (natural talent and intelligence) and possession as can be seen in (13) and (14).

(13) Para que veas en que familia quedaste, jaja. (MS18, S3) [So you can see the family you will be living with, ha ha.]

(14) I only helped. My mother did most of it. (IE2, 3)

Reassurance or repetition request. It is difficult to interpret the real purpose of CRs that took the form of a question (see 15 below)-whether they seeks for the compliment to be repeated, expanded, specified, or perhaps question the sincerity of the compliment. As shown in Table 2 above, this response accounts for only 1% of the Irish compliment responses and Mexicans did not use it at all. These findings differ from previous studies (e.g., Valdés & Pino, 1981) where this strategy is commonly employed by Mexican-American recipients.

(15) Why? How old do I look? (IE3, S1)

Combination of strategies under mitigating. As was the case with the accepting category, mitigating strategies are also frequently combined. In both groups, in fact, almost half of the CRs (184 out of 540 Mexican CRs and 189 out of 540 Irish CRs, see Table 3 under this category are combinations of the previous two strategies.

Appreciation token and deflecting/qualifying comment. This type of combination is the most common in the two groups. This accounts for 30% of the Mexican data and 29% of the Irish corpus. Even though there is still an appreciation token present in the responses, there is a slight disagreement. Pomerantz (1978) considers that the recipient evaluates what was said and assigns a less positive comment about the praised aspect. In this way, the recipient avoids self-praise.

(16) Gracias, pero el crédito se lo lleva mi mamá. (MS9, S3) [Thank you, but mom did most of it.]

(17) Thank you so much, I just threw it together. (IE17, S3)

Appreciation token and reassurance or repletion request. This combination is higher in the Irish data than in the Mexican data. Six percent of the Irish data and only 2% of the Mexican responses use this combination. In this type of response, the speaker accepts the compliment with the appreciation token, but at the same time, s/he questions the compliment assertion. According to Pomerantz (1983), this type of response displays a neutral stance on the part of the compliment receiver. In other words, they neither accept nor reject the compliment. The preference of this strategy among the Irish participants reflects similar behavior in British English (Lorenzo Dus, 2001). Even though the Irish employ this response more than Mexicans, they use it less than British speakers.

(18) ¿¿En serio?? Wow, gracias! (MS15, S7) [Really? Wow, thank you!]

(19) Oh, really? Thank you very much! (IE5, S4)

Agreeing utterance and reassurance. This combination is only used by Mexicans 2%), it is not found at all in the Irish data.

(20) ¿En verdad te gustó? Es receta de la abuela, jo jo. (MS14, S3) [Do you really like it? It’s my grandmother’s recipe, ho ho.]

Rejections

Disagreeing utterance. Disagreeing utterances give the speakers the opportunity to avoid self-praise. The data show similarities in the use of this strategy in both cultures. The high preference for this strategy among Irish and Mexican subjects reflects similar behavior in British English and Peninsular Spanish (Lorenzo-Dus, 2001), American English (Nelson, Al-Batal, & Echols, 1996), and Irish English (Scheneider, 2000). This response occurs when the speaker not only rejects the compliment, but also disagrees with it. As seen in Table 2 above, this category accounts for 6% of the Irish corpus and three percent of the Mexican responses.

(21) No manches güey, sí he visto tus trabajos y la neta son muy buenos. (MS13, S5) [I don’t think so. I have seen yours and they’re really good.]

(22) I don’t know if that’s a good or bad thing. I hope, I’m not just trying to please everyone. (IE11, S7)

Combination of strategies under rejecting. Lastly, Mexicans employ slightly more combinations of strategies under the category of rejecting than Irish speakers.

Appreciation token and disagreeing utterance. As seen in Table 3, this type of combination is less frequent in the Irish data (5%) and more frequent in the Mexican corpus (15%).

(23) Gracias, pero para serte sincere no me agrado mucho el corte. (MS2,S1) [Thank you, but I really don’t like it at all.]

(24) Thank you, but it’s not as good as it looks. (IE2, S9)

Conclusions

In this study, the notions of politeness in the speech act of compliment responses among Irish and Mexican students were investigated. The data reveal the existence of cross-cultural similarities in Irish and Mexican CRs in the frequency of deflecting comments and the mechanisms that are used to redirect the praise force. These results lend support to Lorenzo-Dus’ (2001) observations that there is a tendency to avoid self-praise on topics such as natural talent and intelligence. This study suggests that, at least in the situations it considered, deflecting comments are used to express solidarity and affiliation. These cultures do not see disagreement as interactionally inappropriate. Self-praise avoidance is seen as a form of protecting and enhancing the complimentee’s own face, and of preserving the affiliation face of the complimenter.

Although the two groups share similarities, they differ in important ways. In responding to compliments, Irish recipients are much more likely than Mexican speakers to use a single strategy when formulating CRs. The infrequency of single strategy use in the Mexican data suggests that gracias [thank you] by itself is not a sufficient response to a compliment and needs to be supplemented by other strategies. The Irish and Mexican data reveal that the Mexican Spanish sequences are much longer than the Irish English. The length is related to sincerity; in Mexican culture, the longer the CR, the greater the level of sincerity. Similarly, Nelson et al. (1996) found that Arabic speakers use long CRs to express sincerity. However, the Irish respondents probably consider it socially inappropriate to use many words in a CR because to do so would run counter to the community rule of attending to one’s interlocutor’s face wants. Another difference in compliment response strategies is the Mexican’s frequent use of disagreeing utterances to avoid a compliment on outward appearance. While rejecting is the preferred strategy for Mexicans, accepting is the preferred response strategy for Irish participants for compliments on appearance. It seems that the Mexican pragmatic system shows an affiliation face-based tendency that serves the purpose of satisfying the hearer’s needs for belonging and common ground. The main purpose of this system is to show appreciation of the addressee by using solidarity and in-group identity markers, and to show interest in and sympathy towards him/her (Curcó, 2007). Self-praise avoidance is subordinated to the more salient function of attending to the face wants of one’s interactant. It seems then, that the rejection of a compliment is principally to protect and enhance the complimentee’s own face (Ruhi, 2006, 2007).

A final result shows that social power (+P, -P), social distance (+D, -D) and the content of the C are conditioning factors in the selection of linguistic strategies. These recognitions are evident in the type of strategy used in a particular situation. In this study, Mexican recipients employ formulaic expressions in accepting a compliment when the C is on possession or skill, and disagreeing utterances when it refers to outward appearance. The findings show that the less distant the relationship between the participants, the more likely it is for these Mexican university students to avoid self-praise. The presence of these forms indicates camaraderie and affiliation. Based on this, it can be said that social distance, social power, and the topic of the compliment play an important role in the selection of the compliment response strategy.

Even though the findings of the present study might contribute to the analysis of English and Spanish compliment responses, a number of limitations have to be acknowledged. To begin with, generalization from the results may be limited since this research only analyzes undergraduate college students who have their own style of responding to a compliment. An additional limitation results from the fact that the data elicitation method used in the present study does not represent natural discourse (Félix-Brasdefer, 2003; Kasper, 2000). In the future, another data method could be used to examine speech act patterns of compliment and compliment response behavior in natural discourse. Another potential area of investigation would be to replicate the study in different populations, such as speakers who are from other regions in Mexico and Ireland or from other Spanish and English speaking countries. Finally, additional studies would be needed to analyze prosodic aspects such as intonation, or the low or high pitch of utterances in verbal interaction.

The differences between the two groups reported in this cross-cultural study highlight the importance of pragmatic competence (knowledge and use of the target language cultural and linguistic norms) as one of the key skills that are necessary to be a successful communicator in the target language (Bachman & Palmer, 1996) and the need to teach this competence in the language classroom. The findings of this research have practical implications for L2 learning and teaching. First, learners who are learning a second language need to know what kind of knowledge they possess in their mother tongue so that they can use it to acquire linguistic structures and social conventions in the L2. Second, L2 teachers can provide the information that helps the learners to be aware of what they already know and encourage them to use their pragmatic L1 knowledge in L2 contexts.

References

Appendix A

Métricas

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2019 Elizabeth Flores-Salgado, Michael T. Witten

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivadas 4.0.

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/