DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.152Published:

2009-01-01Issue:

No 11, (2009)Section:

Research ArticlesCollaborative action research: building authentic literate practices into a foreign language program

Investigación acción participativa: la construcción de prácticas auténticas de lectura y escritura en un programa de lengua extranjera

Keywords:

Investigación acción colaborativa, lectoescritura en segunda lengua, Japones (es).Keywords:

Collaborative- action research, literacy in a second language, Japanese (en).Downloads

References

Aihara, S. & Parkes, G. (1992) Strategies for reading Japanese: A rational approach to the Japanese sentence. Tokyo: Japan Publications Trading Company.

Alderson, J. C. and Urquhart, A. B. (1984). Reading in a Foreign Language. London / New York: Longman

Altrichter, H; Posch, P & Somekh, B (1993). Teachers investigate their work: An introduction to the methods of action research. London & New York: Routledge.

Austin, T., Nakayama, C. Oda, A., Ley , Y. & Urabe, S. (1994). "A yen for business: Learning Japanese through a business simulation." Foreign Language Annals, 27(2), 196-220.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research. London/ Philadelphia: Falmer Press Carr, W. and

Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical. Education, knowledge and action research, Lewes: Falmer.

Carrell, Patricia, Devine, Joanne, & Eskey, David (1991). Interactive approaches to second language reading / edited by. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Chastain, Kenneth and Woerdehoff, Frank (1968). "A Methodological Study Comparing the Audio-Lingual Habit Theory and the Cognitive Code-Learning Theory." The Modern Language Journal, 52 (5), 268-279.

Freire, P. & Macedo,D. (1987). Literacy:Reading the word and the world. London:Routledge.

Gaies, Stephen (1985). Peer Involvement in Language Learning. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Goodman, Kenneth S. (1982). Language and literacy : the selected writings of Kenneth S.

Goodman, edited and introduced by Frederick Gollasch. London/Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Gumperz, John (1982). Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heisig, J. W. (1987). Remembering the kanji II: A systematic guide to reading Japanese characters. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Publications Trading Co., Ltd.

Horiba, Y. (1990). Narrative comprehension processes: A study of native and non-native readers of Japanese. The Modern Language Journal, 74 (2), 188-202.

Hudson, T. (1982). The effects of induced schemata on the "short circuit" in L2 reading: Nondecoding factors in L2 reading performance. Language Learning, 32, 1-31.

Royer, J.M., Bates, J.A., & Konold, C.E. (1984). Learning from text: Methods of affecting reading intent. pp 65-85, In J.C.Alderson and A.H.Urquhart (Eds.),

Reading in a foreign language. London: Longman. Smith, Frank, ed. (1973). Psycholinguistics and reading. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Spyridakis, Jan (1989). Signaling Effects: Increased Content Retention and New Answers--Part II.Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 19 (4), 395-415.

Swaffar, J., Arens, K., & Byrnes, H. (1991). Reading for meaning. An integrated approach to language learning. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Insup Taylor and David R. Olson, (Eds/0 (1995). Scripts and literacy: Reading and learning to read alphabets, syllabaries and characters. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Wells, G. (1993) Text, talk and inquiry: Schooling as semiotic apprenticeship. Paper presented at the International Conference on Language and Content (Hong Kong, December 1993).ERIC Document 371618.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2009 vol:11 nro:1 pág:29-47

Research Article

Collaborative action research: Building authentic literate practices into a foreign language program

Investigación acción participativa: La construcción de prácticas auténticas de lectura y escritura en un programa de lengua extranjera

Theresa Austin

Professor Language, Literacy and Culture Department Teacher Education & Curriculum Studies School of Education, University of Massachusetts, Amherst E-mail: taustin@educ.umass.edu

Mark Blum

Associate Professor, Department of East Asian Studies State University of New York,Albany E-mail: mblum@albany.edu

Abstract

Two university professors collaborate to carry out an action research project on literacy in a world language program. This article reports on their negotiations to define literacy, how they adapt the use of texts to the cultural backgrounds and interests of their learners and integrate native speakers in a community that builds various understanding of texts through discussion. Our collaborative process provides one example of how action research can systematically inform teaching and learning to build authentic literacy practices in a second or foreign language program.

Key Words: Collaborative action research, literacy in a second language, Japanese

Resumen

Dos profesores universitarios colaboran al realizar investigación acción en un programa de lenguas extranjeras. Este informe provee detalles sobre su negociación del significado de literacy, explica como acoplaron la selección y lectura de textos a los intereses y cultura del educando, además de integrar a nativo parlantes en una comunidad formada por lectores que construyen sus interpretaciones a través del diálogo. Nuestra colaboración provee un ejemplo del proceso de investigación acción que puede informar la enseñaza y aprendizaje de prácticas auténticas en un programa de segunda lengua o de lengua extranjera.

Palabras Claves: Investigación acción colaborativa, lectoescritura en segunda lengua, Japones

Introduction

What can a small world language programs do to help students truly consolidate, utilize, and stretch their learning: their accumulated language, cultural, and learning skills? What could be predicted now about tasks that they reasonably might face after graduation? Anticipating these tasks, how can we best prepare students to cope effectively with future linguistic challenges? These were several questions facing a Japanese language director / instructor (Blum) during his third year of a newly-formed language program at a middle-sized suburban American university. Collaboration with a language curriculum expert ( Austin) began a joint process of inquiry leading to creation and implementation of an innovative course that experimented with developing a native/non-native reading community.

This type of inquiry is called “action research,” and as defined by Altrichter, Posch, and Somekh (1993) has the “will to improve the quality of teaching and learning as well as the conditions under which teachers and students work in schools” (p.4). In general, action research synthesizes practice and theory, critically grappling with issues in a particular context to fuel changes in both theory and practice ( Carr & Kemmis, 1986). In action research, researchers and participants generally are invested in research processes and its products. Active shaping of our agenda came about through strenuous collaboration. For convention sake, and recognizing our roles as active agents, the first person is used whenever both of the authors mutually contributed. Last names are used when points arose of particular interest to one researcher or another.

Our current collaboration was based on a mutual interest in curriculum development. Blum, as director, was motivated by practical issues relevant to his responsibilities to further develop the Japanese language program. Austin, as a second language and literacy researcher, was motivated by her interest in Japanese literacy development by non-natives and cross-cultural communication between natives and non-natives. Both had learned various languages and were interested in improving students’ classroom learning experiences. Collaboration proceeded through four stages: 1) discussion, negotiation, and articulation of important pedagogical and theoretical concerns 2) operationalizing these issues within constraints of the particular program 3) support during planning, implementation and evaluation 4) analysis of findings.

What is reading in Japanese?

As is the case when people conduct interdisciplinary research, in this joint project assumptions about the nature of the research and procedures were not necessarily shared. Because we approached reading from different perspectives, Austin from an applied linguistic research perspective and Blum’s philological textual analysis approach, it was necessary to negotiate mutually acceptable goals and individual roles. Equally important as a first step was making explicit to each other our different presumptions. These differences surfaced as we experienced conflicts during implementation of the study which required re-establishing common ground. Our first discussions dealt with the nature of reading and how comprehension is developed.

While reading is arguably the one language skill which enjoys a consensus as to its importance, teachers of Japanese as a foreign language are far from agreement as to how to expeditiously promote its acquisition. Through his experience as a learner and teacher of Japanese, Blum’s definition of reading reflected his perspective as scholar of Buddhist texts: reading meant both the ability orally to decode each word (including kanji) as vocabulary and then to decode specific syntactic structures. Both these activities would lead to translation skills. In evaluating his own experience as a beginning reader, Blum was guided by instructors who highly evaluated his ability to assign correct pronunciation and meaning to kanji and translate linguistic structures accurately. Yet when Blum carefully examined this practice through dialogue with Austin, he concluded that perhaps this was not the most helpful process to get fourth year students to focus on the curricular goals which included grasping meaning as it is being conveyed through text organization, through what is implicitly versus explicitly stated, through what is alluded to, and through what is not mentioned at all. Blum had learned these types of skills through discussions with experts in his field, but never in Japanese language classes. Reflecting her second language acquisition perspective, Austin, also having learned Japanese as a foreign language, felt that Blum’s approach focused unneeded attention to the word level, distracting students from intersentential communication—what the text attempted to communicate as a whole. Moreover word level approaches tend to orient the reader’s attention to grapho-phonological associations2 rather than to grapho-morphological associations, which might be much more useful in guessing meanings from Chinese characters and their kana syllabary complements. Austin knew from her own experience learning Japanese that knowing how to pronounce kanji did not assure that learners can make meaning (unless they are already familiar with the word, as is the case of most native-speakers when learning to read).

language students’ processing is slowed down as they are forced to retrieve phonemes before processing of meaning is permitted. In contrast, when learning to read kanji, Heisig (1987) stresses an individual self-taught approach, offering instructors and learners insights into how written symbols can be learned for meaning without knowing pronunciation. Following his visualization technique, the jôyô kanji are learned by sight to correspond to their meaning. It can be argued that pronunciation may help some students store associated meanings in their long-term memory. However, the way some instructors penalize students for not remembering pronunciation may actually underestimate students’ ability to read for meaning and may even discourage others from investing their limited energies in meaning-making activity such as trying to use their background knowledge or knowledge about language to make guesses about meaning. Even worse, it may convince readers that they actually cannot learn to read when, in fact, they may be doing precisely what it takes to make sense of text: contextualized guessing, checking for accuracy of guesses, confirming new propositions in a logical structure, anticipating author’s intention, etc.

According to Swaffar et al. (1991: 154) research on good second language readers has identified six of their activities: 1) correcting misreadings, 2) making connections between sentences rather than focusing on only on information contained in each sentence, 3) identifying how texts are organized, 4) expressing comprehension more fully in the native language than in the second language, 5) developing a wide range of reasoning strategies that are not identical with those of their classmates, 6) understanding text and how to apply the text for their own purposes or views. Languages in the cited research were alphabetic languages, but we wondered how these same practices might be employed to become good readers of Japanese.

Authentic tasks for which vocalization of reading are necessary: giving a speech, newscasting, reading to others, etc,. are rarely main objectives in reading lessons. Perhaps because authentic tasks require considerable time devoted to both production and decoding of written materials, they are deemed impractical within constraints of a semester. In essence, many instructors relegate tasks at the discourse level to homework so as not to spend class time on this aspect of meaning making. Even writing is often something assigned “for homework” to save valuable class time for activities deemed more important.

Dialoguing about these practices, we began to question why there is a need to vocalize any reading except where pronunciation itself is at issue, i.e. outside of specific types of tasks mentioned above. For example, personal and place names are commonly read and processed by native Japanese speakers without certainty as to their correct pronunciation, and native speakers sometimes skip over an unfamiliar pronunciation of a word while still generally understanding its concept. These “sight” vocabulary words are not an issue except in situations where they must be read aloud, as in names or in situations where pronunciation is required by the reader for reference purposes, such as in dictionaries, telephone books, indices, etc. Consequently, by distinguishing between decoding for meaning from decoding for sound, we could prioritize skills required of learners and help them use their limited energies more efficiently. Hence vocalizing during reading should arise only when the need arises to do so naturally. When reading is viewed thusly, curriculum can be designed that reflects authentic demands of reading. When, where, and how vocalization are done could be determined after meaning is made and only when necessary.

We also questioned the common way that “reading” is defined in Japanese classrooms3 as a translation exercise. While translation does have some benefits, it tends to focus the student more on rendering content accurately into the learners’ first language, and therefore away from developing critical perspectives on content or argument structure. In fact, this type of learning may foster more linguistic precision in the student’s first language than their ability to express themselves in Japanese. It is plausible that if Japanese linguistic structures are not produced by learners for expression of their own thoughts, the only productive practice they will receive is translation into their first language.

After such discussion, Blum decided to focus how Japanese texts are structured and how to evoke more reader response to the texts under consideration. He further reasoned that when one is able to predict the text’s structure, skimming for main ideas and scanning for specific information can be carried out more expeditiously. These skills, plus guessing and checking guesses for accuracy, could be useful strategies enabling second language readers to take advantage of their background and content knowledge, thereby compensating for limitations in linguistic knowledge.

Since text structures may be quite difficult to navigate if students only bring expectations based on their first language, Blum decided that class discussion in Japanese should be encouraged to permit students to share responses to reading materials. Such discussions would require language learners, many for the first time, to incorporate complex ideas, vocabulary, and patterns from reading into their speech at minimum for referring back to the text, and at maximum for fomenting possibilities of creative responses as they share their interpretations of the author’s messages. The contact would allow for students to indicate what they understood as a whole, including troubling vocabulary, syntax, etc.

Austin (Austin, et. al., 1994) added that including native speakers’ participation might give learners additional support. Not only would their interaction provide added input, but could also function as a stimulus for recognizing rhetorical organization, bringing out crosscultural similarities and differences in reading customs, and providing opportunities for expressing opinions. By creating a low-anxiety, supportive community of readers, non-natives might feel encouraged to venture further into reading for their own purposes, formulating stances about what they understood or not and learn communicative skills as others reveal how they were impacted. Since this aspect had been unexplored in his classes, Blum was eager to attempt it. Participation of native- Japanese speakers meant their insights regarding the structure of Japanese text would be available for English speakers to contrast with similar English texts. Blum reasoned that while English expository prose may have more rigid structural guidelines such as the traditional sequence of thesis, supporting evidence, and conclusion, Japanese has a rhetorical structure that derives from Chinese poetry. Aihara (1992: 184) found a common four-part structure that is “more like dramatic narrative: ki (introduction), shô (development), ten (turn), ketsu (conclusion).” Overt connective markers at sentence beginnings do not apparently offer the same level of topic/ support cohesion expected in English prose. Therefore, understanding written Japanese requires learning about common cohesive devices such as ellipses, mixed metaphors, and semantic chaining, common in expository writing. In examining the whole text’s structure, linguistic knowledge about such things as functions of metaphors, collocations, and object -verb selection parameters across text structure help learners understand images the author is using to construct messages. Learning to see connections between ideas makes it easier to predict what the author is attempting to communicate and to guess meaning of unfamiliar vocabulary. In this way, background knowledge associated with the content and text type more efficiently interacts with reader knowledge of topic and language, assisting their interpretation.

As a Buddhist scholar, Blum also indicated one more important aspect of learning to read - learning how to interact with texts for personal or academic purposes. Knowing what kinds of reading strategies to use when and how is important. In order for instruction to be effective, learners need to determine which approaches speak to their concerns and what needs to be supplemented or modified in their reading strategy repertoires that will aid their particular search. Interaction among students would be necessary, as well as between instructor and students, to support their process of reflection on both the text at hand and their particular strategies. Blum would need to facilitate developing critical responses to potential messages that selected texts convey. Yet how could this be accomplished?

Operationalizing a study within university constraints

While a year would be necessary to fully plan a project, obtain materials, and recruit students, Blum had only the summer semester to complete plans for implementation. This meant intensive discussions with Austin concerning their roles, materials needed, and course structure. After jointly designing the course, Austin would be a resource person, monitor class progress, and then conduct student interviews to evaluate the class. Blum would recruit students to collaborate, prepare reading materials, teach, and keep observation records.

Reading Course Design

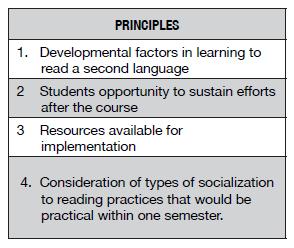

Our new curriculum would require use of all four skills while students interacted around written text in a manner they might encounter in real life. The decision to practice these skills by focusing on their relationship to reading, rather than a traditional balanced four-skills approach was based on four principles:

Developmental Factors. Despite efforts of traditional four-skills curricular approaches which attempt to devote relatively equal time to all skills, it is well-known that students do not develop these skills at the same time nor to similar degrees of proficiency. This was particularly evident at this university in describing students’ progress in learning Japanese. During the first two years, listening and speaking were emphasized; while the third focused on reading comprehension. Yet most students had limited exposure to authentic non-fictional reading material. After interviewing potential students, Blum realized that few had taken advantage of the year-abroad program, and even fewer had developed survival reading skills.

Sustainability of Learning. Singling out reading, with support of the other skills, could hold promise for students who desired to become more independent learners. Blum expected that most graduates would be encountering authentic, non-fictional reading material in the workplace, perhaps even on a daily basis. Therefore, promotion of reading autonomy seemed to offer the highest possibility of enabling students to continue building their own language and cultural proficiency after graduation.

In addition, many reading materials follow a sequence of preview, information organization, sentence analysis and opinion exercises. These activities assume that students are all approaching a text with similar reasons to read, similar needs for background information and similar language needs. In reality, outside of the classroom, if students took on a reading task, most likely their approach would not have these aides or activities. Therefore, to sustain their reading, each student would need to develop steps to help them individualize reading for their particular purposes.

Scarcity of Resources. Without a sizeable Japanese-speaking community in the area, faceto- face interactive language practice was very difficult to arrange. Regarding other resources, there was no Japanese television or radio in the area and Japanese films were never shown in local theaters. While many video sources exist, campus and local area holdings were minimal and not likely to increase because of severe budget cuts. In contrast, due to the existence of a Japanese cultural center, a library of texts was readily available. Also the university had international students from Japan who could be a potential source for giving students added contact.

Socialization to Reading. Although socialization to speaking is an equally worthy goal, it would require resources beyond what we could conceivably obtain for use in a semester-long context. Whereas contextual cues for reading can be abstracted from most texts, if the same were attempted for studying cues for speaking and self-expression, there would be a need to include contact with a variety of native speakers (age, gender, class, ethnicity, region) in a variety of speech events in varied settings in order to provide even limited exposure. A collection of articles was logistically more viable to address rhetorical variety.

While it is traditionally believed that reading is an activity that can be sustained after students’ graduation, we felt that “reading” needed to be reexamined to ensure that what is done in the classroom actually enables beginning readers to appropriate texts and to know how to interpret them beyond the classroom. The refinement of the original question began with a definition of “reading” for these purposes.

Although most language departments do not deal with the particular literacy issues arising when the target language’s script differ’s from English, we maintain this to be a serious shortcoming. We take this position from a framework in which the notion of “reading” is conceived of as critical activity to understanding and utilization of social practices of a culture ( Freire & Macedo,1987; Wells, 1993) Other proponents of this view can be found in the whole language movement, critical literacy, and to some extent in research on language for specific purposes.

Our position contrasts with solely psycholinguistic orientations (Smith, 1973; Hudson, 1982; Goodman, 1982) which view reading processes as separated or isolated from social contexts in which they occur, and assume processes internal to the reader are context-free. When research is framed by a belief that reading is solely an internal process and context free, the construct of “reading” becomes limited in a way that excludes important elements of how readers actually deal with texts. For example, in some research studies, comprehension is measured by timed tests, filling in the correct verb form or missing cloze item, or retelling as much of a narrative as can be remembered. In fact according to Carrell (1991), there are a wide variety of factors which influence comprehension and its assessment. Although real time constraints do exist for processing written matter, they vary according to the types of purpose that one may have. Consider the variety of effects these different texts have upon the control and use of time during reading experiences: subtitles on a video, scripture for religious contemplation, a telephone directory, train schedules, novels, etc..

Many research studies point out that recall does not equal comprehension or understanding. In reality, we do summarize, leave out certain detail, evaluate what we like or don’t like, skip sections, especially when we understand these sections. If we are a member of a group that regularly meets to discuss certain items of interest, we must prepare our points of view and know how to share that point with our audience. If we are members of academic community, we may be required to substantiate our views according to certain practices in our fields. Our communicative practices shape and are shaped by our respective speech communities. Members create new conventions and follow agreed upon conventions as well. We needed to create a learning environment that builds upon students’ natural skills to prepare them for participating in and shaping a community’s practice. For us, this meant creating what could be identified as a “community reading circle” that would use oral language to support development of reading comprehension.

Support during project planning, implementation, and evaluation

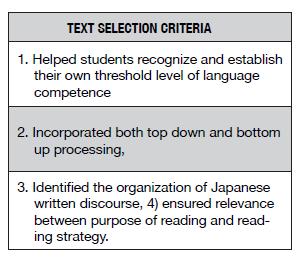

One common claim affirms a direct relationship between second language proficiency and second language reading. Alderson (1984) claimed “good” readers can transfer their good skills only if their proficiency level has met the threshold level. Yet Swaffer, et al. (1991) argues “...there is no evidence that L2 skills alone guarantee students who can read for meaning.” It has been argued that both a threshold level of second language competence and reading skill in the mother tongue are important, as well as other factors about learners and learning environments (Carrell,1991).

Furthermore readers interact with text by using both “top-down” and “bottom-up“ processing. Successful readers need to use top-down processing to make use of background knowledge and various reading strategies to deal with topic organization through the text’s rhetorical structure and its information sequence. They also require “bottom up” processing to understand supporting details, features of language that convey these details.

Unfortunately, most studies have been conducted in Western languages with alphabetic writing systems. The limited number of studies that examine second language reading in nonwestern languages (such as Taylor & Olson,1995; Horiba, 1990) often define reading in ways that are not compatible with notions held by the authors as described above.

Nonetheless, while notions of “reading” are defined in certain studies in ways that do not resemble practices people actually engage in, we can still appreciate contributions of first and second language psycholinguistic research on cognitive processes involved (schemata activation, predicting, skimming, and scanning), all of which enable hypothesis generation and confirmation. Although these practices may enable readers in their first language to understand written matter, learning to read in a second language whose notions of reading, purposes and rhetorical styles are not shared with the student’s first language requires acquiring these notions in the process of learning to read. Therefore, an approach that socializes learners by building schemata with scaffolding from instructor and peers simultaneously while students are processing text seemed sensible, with guidance altered based on specific needs, be it contextual, informational, etc. Learners also need help in interpreting and inferring messages as they deal with text they find interesting. This approach aims at an author’s purpose and use of linguistic tools to convey meanings, differing dramatically from reading instruction that stresses accuracy in translating at word or phrase level.

To foster this awareness, Austin prepared for Blum and his students selected background readings about Japanese written discourse that:

Student Participants and Roles

As this project was designed to actively involve students, Blum invited all potential students including native speakers to participate in an informal orientation in which topics were nominated and selected. Each student could choose one topic and the instructor also added one. Timing was crucial as participants needed to be identified early so that materials relevant to their interests could be gathered. The plans were explained and research motives for their reading development were included.

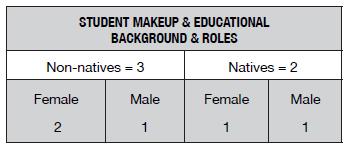

Interaction between Japanese language learners and native speakers of Japanese was essential. Three language learners and two native speakers participated and were given the same material to prepare but with different tasks.

The female native speaker had spent more than half of her pre-college and all of her college educational experience attending English language education in English-speaking countries. Subsequently, she had the following bilingual skills: native fluency in reading and speaking English, native fluency in speaking Japanese but only pre-collegiate skills in reading and writing Japanese. She identified as being Japanese but had a “international” culture. Initially she was an ”undeclared” major then later identified a double major in communication studies and business.

The male native speaker was born in the Tokyo region, and received K-12 education in monolingual Japanese schools, coming to the U.S. as an exchange student. His English ability came from learning English grammar in six years of secondary education in Japan, then in ESL classes in the States, and finally three years of undergraduate college education, majoring in psychology.

The non-native students were all born in the United States. There was one Afro-American woman who had gone to an international high school in Japan during her father’s sojourn there and had returned from Japan two years earlier, one male student who had never been to Japan but had married a Japanese national, and one woman who had spent one year in Japan as a student 12 years earlier. All had received 6 semesters of Japanese instruction covering basic Japanese grammar and verbal communication skills.

Course

Over the 15 week semester, the course was designed to incorporate the following skills when approaching a text “cold”:

Judicious usage of dictionaries was an important goal for Blum because he considered it an essential building block for achieving independent status as a Japanese language reader. Students had been instructed on how to use dictionaries in the third year but they needed further practice to choose an appropriate dictionary, read explanations written in Japanese in dictionaries without English referents, and efficiently find words written in known and unknown kanji.

In the orientation, he explained that translations would not be valued. In prior courses, discussions were either in English about Japanese- language materials or in Japanese about Japanese-language materials which were not authentic and therefore limited in intellectual and emotional range. Thus, translation became a tool that many learners came to rely upon to “clarify” their understanding of content. To change this pattern, we hoped the participation of native speaking students would unobtrusively capture reading difficulties and provide realistic opportunities for oral negotiation of the texts’ multiple interpretations. By providing only authentic, contemporary materials geared to an ultimate discussion in Japanese, Blum explained to students that translation might in fact hinder their success. We hypothesized that once information was transformed into their native language that information would be recalled in English. Thereby subsequent discussion in Japanese would require them to retranslate that information back into Japanese. Learning and keeping information in its original form would obviate the need to spend time translating for retention and avoid the stress of trying to translate back during conversation. The problem of making oneself understood would mean appropriating material from its original context and applying it to one’s own meaning making endeavor in Japanese. This requires processing Japanese text at higher levels, and why native speakers were on-hand for assistance.

Roles of each group were differentiated so that grading would not give unfair advantage to native speakers. Non-native speakers would be expected to discuss what they did and did not understand; native speakers would help clarify the text. The assignment for non-natives would be to prepare readings, including decoding questions, and attempt to discuss their readings in Japanese, including arguing for one point of view versus another. Everyone acknowledged that in a working environment they may be called upon to do precisely that—read through Japanese language materials and be able to ask relevant questions of native speakers for clarification, ultimately to act upon their findings either in English or Japanese. The native speakers’ presence was designed to enable the language learners to experiment with this kind of interaction, and both groups were encouraged to solicit information from each other and the instructor, ideally in Japanese. Among the stated goals were learning how to acquire the skills of getting information in Japanese on a topic they knew little about, how to ask for clarification, and how to process explanations of complex ideas. Because topics were chosen by our students, we felt that they would have a stronger than usual motivation to construct their voice in achieving these tasks.

The course was scheduled to meet weekly for three hours. In the first fifteen to thirty minutes students would divide into two groups to privately discuss and consolidate their understandings, each with a native speaker in a pivotal role. The whole group then re-assembled and individuals were encouraged to take positions and to express their opinions. A final paper was required of all, yet tailored for each group differently. For nonnatives, it meant selecting and rereading previous assig-ned reading and writing a reflective essay on one topic to explain its significance, their difficulties in understanding, and the diversity of interpretations of class members. They were to write approximately seven pages in Japanese of 400-character genkô yôshi paper. Native speakers read of drafts of the papers written by non-natives and suggested changes.

Native speakers were required to discuss their findings about what types of learning difficulties and successes they noticed as most common among the language learners. One focused on notes generated in paired interactions where difficulties surfaced throughout the course. The other native speaker focused on difficulties students had in writing their reflective essays. The fully native speaker and writer of Japanese was required to write his paper in English; the native speaker with less than collegiate writing skills was required to write her paper in Japanese.

Grades were determined by class performance and the final paper. Class performance included preparation for discussion, attention to discussants’ points of view, and participation. Each student would lead at least one discussion. Students’ progress would be used as the barometer for determining final grades; thus everyone competed only with themselves.

Reading Materials

A total of five topics were discussed. After much lively discussion, chosen topics included: Aum Shinrikyo new religion, WWII and the atomic bomb from the Japanese point of view, right-wing nationalist causes, problems faced by Japanese children who return home after educational experiences abroad, relationship between language and culture or the psycholinguistics of Japanese. Due to difficulty obtaining first hand materials from a right-wing nationalist cause, this topic was replaced by another article on issues concerning the war responsibilities of post-war born Japanese.

Except for the reading materials distributed in English at the beginning for the purposes of explaining Japanese written discourse, all readings were authentic Japanese expository prose copied from contemporary sources such as newspapers, magazines, religious tracts and recently published books. No reading aids such as vocabulary lists or explanations of grammar or usage were distributed until discussion on a particular reading had concluded. Blum did not review new material prior to class discussion. Students were thus forced to develop ways of approaching texts that would serve them personally, understanding their own strengths and limitations.

Research Issue

After coming to a mutual understanding of reading, and having students involved in course planning, our focus turned to what facilitation or “scaffolding” would be necessary to help students with texts and with their own understanding of successful reading strategy usage. In order to do this, we needed data derived from naturalistic reading tasks that our students engage in.

Methodology

Throughout, Blum documented his attempts to help students in class, and native-speaking students were responsible for analyzing their interactions with language learners. After the semester ended, all students were interviewed by Austin in a non-formal setting to find out 1) general perceptions of their own and other’s reading progress during the course: what they learned, what they thought was useful, and what they found particularly difficult, 2) difficulties that emerged with the course’s structure, instruction and content, 3) their suggestions for improving the course for next year.

Since students were told that being interviewed was voluntary and would not affect their grades, they were under no pressure to provide feedback. Nonetheless, all eagerly gave their input. Only one was unavailable during scheduled interviews and unable to provide any comments. Blum wrote a reflective narrative on the experience after the semester.

Findings

All in all, from both the students’ perspective and Blum’s, it was an exciting class. Interview responses were relaxed and continued as long as students wanted to talk, on average lasting 1-1.5 hours. Since there were few students, their responses were not tallied but rather grouped in terms of themes raised. Findings here are discussed in terms of students’ insights and Blum’s own reflection of the process. The enthusiasm and excitement generated were not without accompanying instructional challenges.

Dealing With Heterogeneity. While every class is a mix of levels, extreme student-level heterogeneity is a major challenge for almost every instructor, and full texts have been written on this subject. Approaches which sub-divide levels creates curricular solutions but a socially divisive class. It pits students into competitive groupings, segregating “those in the know” from others. While such distinctions may serve to inspire a selected few, effects on the whole class may be less positive. Alternative to this type of individual competitiveness, Blum was interested in motivating students to collaborate in considering how they approach reading. The course brought students to recognize the ways they approached texts differed significantly, learning to name several strategies. The native-speaking students also noted various strategies among non-natives. Unfortunately, the most commonly reported strategy was translating every word. In only two cases were non-native reported to have tried scanning to gain general understanding.

All three non-natives claimed they learned to appreciate their classmates’ views, but also reported tension over who had contributed most in preparing for discussion.

The above socio-cognitive goals and experience of getting students to work harmoniously together despite variance in linguistic proficiency taught them several things: to capitalize on each member’s strengths without emphasizing their limitations, to cooperate in realistic situations, and inevitably to achieve together beyond what they could achieve individually. Non-native students reported benefits from working with each other, and also identified how native speakers helped them individually with vocabulary by giving examples and paraphrasing, finding kanji, translation, and expressing their ideas. As learners, they seemed to have become more aware of the types of help they needed and their areas of strength.

During the semester, Blum found discussions were more lively and engaging than anticipated, occasionally making it difficult to be precise about particular students’ strategies. Together with the native-speakers, he supplied background knowledge, sequence of arguments, explanations of metaphors and ellipses, but after texts were prepared. In terms of oral Japanese use, discussions that went beyond non-natives’ abilities had to be slowed down but engagement never ceased. The gap in Japanese speaking ability between native and non-natives always remained significant, however, manifesting itself in either non-natives giving up and switching to English whenever the discussion became too complex, or one of the native-speakers becoming bored with the pace and frustrated with language learners’ inability to retain vocabulary they had just learned.

One of the learners had particular trouble in expressing complex notions in Japanese. Curiously, despite being married to a Japanese, he had never experienced such intensive Japanese speaking discussions before and found them exhausting.

Responses to Reading Material. The three non-native students chose to write their reflective essays on the same topic: children returning from living abroad (kikoku shijo). Their responses revealed that class discussions had created interest which transcended the reading, probably due to the contributions of the female native speaker who had just such a background. Her personal testimony created a deep impression on the language learners who were able to make connections between text comprehension, discussion, and personal responses. Thus they found it easier to write about.

In contrast, the one reading most consistently criticized was the excerpt reflecting a nationalistic view of World War II. Most of one chapter from a larger text, it suffered from a lack of context and the author’s rambling style which lacked logic and rarely came to the point.

Pacing. Balancing the amount of material required to generate genuine discussion against student ability to prepare texts cold was not easy. This had to be monitored as Blum developed a sense of students’ language competency threshold and reading proficiency. Students reported spending too much time figuring out how to read the material, leaving them unprepared for discussions. They complained the reading material was too voluminous without vocabulary lists or structural notes. Just when they began to feel familiar with new vocabulary after 2-3 weeks, the text changed and they faced a new, unrelated topic. While this is a common occurrence when reading alone, perhaps from the students’ perception, being evaluated on their classroom performance for a grade contributed to their sense of a stressful pace.

Early on Blum had anticipated that pacing would be an issue. The measures he took included re-scheduling two weekly meetings of 1.5 hours each to one, three-hour period, and amending his original, tentative reading schedule as necessary. Blum had scheduled time for native/nonnative conversations in pairs to precede group discussions to allow sufficient opportunities for question asking, commenting and extrapolation, at times allowing up to 1.5 of the 3 class hours for such. However even these adjustments still did not seem to address students’ sense of being rushed.

Ambiguity in Language Switching Rules. Since essentially everyone was reading entirely new material about subjects they knew very little, we feared that only facile discussion on complex issues would ensue. To prevent this yet also remove the anxiety producing burden of forcing all discussions to be only in Japanese, students were allowed to speak in either language when fatigued, frustrated or lost.

When enthusiastic discussion on a topic out-paced the non-natives’ language ability, discussion at time switched into English. While this is helpful for top-down processing and higher order reasoning, it may or may not be helpful for bottom-up processing that is required for closer text examination. From the instructor’s view, Blum found it difficult to guide discussions back to Japanese after English prevailed for extended periods, and wondered to what extent practice in Japanese oral expression should be allowed to dominate the stated goal of promoting reading comprehension.

Furthermore when one male non-native had more trouble in keeping pace with the discussions in Japanese than other students, Blum felt he had to intercede to check this learner’s comprehension. Because students as a whole were not monitoring to see if this student understood their dialogue, Blum used various methods to recycle main points in Japanese. These consisted of having the discussion leader periodically summarize, having a native speaker provide commentary, and restating himself what he saw as key concepts. Blum also encouraged the student to ask for summaries, clarification, and further explanation. Evidently, students were not accustomed in Japanese to admitting their lack of understanding or checking if others understood.

The struggling student actually had a positive impact on making points of class discussions clearer for everyone. However, this fact was only mentioned by the instructor and perhaps went unnoticed by other students.

Student Perception of Their Responsibility. Initially students appeared to understand Blum’s expectations. However as the course progressed, it became clear that roles were under-specified. The male native-speaker seemed to concentrate on the many sound-to-symbol correspondence errors that students had in reading and their vocabulary limitations. Clearly he had unrealistic expectations of non-native speakers. He did not adjust his level of speech well enough to accommodate non-natives listening and they in turn could not make as much use of his contributions for their own oral language production. His remedy to communication breakdowns in Japanese was often translation into English or switching to English.

When interacting with non-natives, the female native speaker felt responsible to ask about and respond to non-native speaker’s ideas. She clearly saw her role to be a mediator helping students through the flow of conversation. She adjusted her vocabulary, used gestures and simplified her speech to ensure mutual comprehension. Since non-natives had access to both native speakers, all three considered the Japanese female to be much more intelligible and helpful. Obviously, the native speakers’ focus on one or the other of their roles impacted the learners in different ways. Judgmental interaction produced more negative impressions of the male while more meaningful interaction produced positive impressions of the female.

Despite Blum having modeled varied techniques for approaching texts, non-native learners reported relying on translation as a major strategy for approaching new texts. They all claimed to feel insecure without knowing what each word meant. Sometimes this led to copious time spent in dictionaries only to learn the word in question was a personal or place name. Frequently they misjudged word boundaries, producing compound characters they could also not find as dictionary word entries. While learners felt at ease seeking clarification from native speakers in small groups, their strategies for clarifying their own expression of the text’s content still needed expansion. Nevertheless, at the end of the course they all felt confident in being able seek out desired information from a previously unseen text, given enough time.

Connection to Writing. The three Japanese learners voiced their concern that the final written project was too difficult because they had been given very little practice in writing essays. In the future they suggested requiring assignments with similar writing practice throughout the course. Blum had felt that asking them to write would have been too demanding. Yet, in the interviews this need was clearly expressed.

Discussion

Though promoting group interaction may seem idealistic, it provides a space for closer observation of heterogeneous ways in which students build, critique, and improve their understandings. In our project to learn about how students approach text to become autonomous readers, group participation wherein collaboration and self-awareness skills were valued contributed both to their learning experience and our assessment of their progress. We began with the assumption that creating a community to process text would help students appropriate words, phrases, and concepts from text to make their own meanings. We also held that talk about texts would help students better comprehend texts, get a sense of the variety of possible interpretations, and develop rationalizations for these interpretations. The group’s heterogeneity allowed for this but also produced tensions that were not anticipated, such as judgments about individual contributions.

We counted on students’ interest in selfselected topics to sustain their motivation, but pacing and sequencing of topics limited their ability to build on the linguistic elements they were learning. In essence, they were developing valuable experience reading texts “cold” but the texts were so different that individual learned items were not reinforced or easily transferred. In consideration, if instructors have students make explicit choices about “how” they want read a text, e.g for enjoyment, for particular information or for general discussion, it might help students focus better and improve their performances. After all, this course neglected the possible goal of reading alone without discussing contents with anyone.

In addition because rhetorical organization, length, and syntactic complexity varied among the selected texts, more time may have to be devoted to facilitate students’ comprehension and management of these issues. The instructor must avoid the temptation to select easy texts —only concise, well argued pieces whose conclusions are easily identified— as well as the error of not providing enough time, as in our case, to handle comprehension of difficult texts. A balance should be sought that allows learners to experience success using their learning skills to tackle difficult readings and those already within their comprehensibility range. This was particularly true of the excerpt taken from a rightwing book blaming Roosevelt for Pearl Harbor and Japan’s entry into the War. Although this choice was the result of a long search, it did not function well because of the author’s style and class time constraints. While this could also have been due to having a section that was not easily extractable from the whole text, it raised an important issue. Unless criteria of selection intentionally includes poorly written texts as a means of contrasting those that are well written, textual clarity should be ascertained to determine its appropriateness as well as how much time will be needed for its analysis. To date, we know of no existing text readabilty formula for Japanese learners. Thus guidelines about what fourth year students can manage naturally should be negotiated at the classroom level between teachers and students. As documentation of different texts’ use is developed, each institution can determine the levels handled with greater ease and accuracy, and the extent to which students can be challenged.

Pacing. Following students’ actual pace of work would permit material on a particular topic to be better distributed. For example, Blum realized that instead of giving students four different newspaper articles all at once as the basis for 3 weeks of discussions, specific articles could be designated for specific classes.

Furthermore as articles are extended, others can be rescheduled, re-distributed, or eliminated after class discussion.

Improvement could further reduce some student anxiety by making grading policies more explicit. In making clear that text approach strategies were more valued than vocabulary knowledge, students would see that they were not being judged on what they knew, rather on how they were incorporating different strategies according to their purposes. Perhaps this aspect was not stressed enough. Prior research, notably Royer, Bates & Konold (1984) identified how level of detail learned from any text would vary according to what learners wanted to learn.

Other alternatives could be 1) having criteria jointly developed with students to recognize the amount of effort required to read through a particular text 2) allowing students to rate themselves on use of various means to comprehend texts 3) extending oral interaction around the text until students are comfortable to move on. Swaffer, et al. (1991;77-78) offer a procedural model that could be used depending on the complexity of selected texts. Their six stages are: 1) Students preview work to establish content and logical orientation, 2) Students identify middle-level or episodic structure, 3) Students read for details-beyond gist or global comprehension, 4) Comparison of word-and phrase level reconstruction of textual information in matrices, 5) Sentence level reconstruction of textual information, 6) Supersentential construction of reader’s opinion about textual information. While these procedures may change the pace for more difficult texts, whether or not they help students is an empirical matter that merits study.

Ambiguity in Roles and Language Switching Rules. We learned that student roles and responsibilities should be distributed in writing and discussed before beginning. For both nonnative and native students, responsibilities could include having students keep a log for each reading, having open-ended statements in the appropriate language (E=English, J=Japanese) as suggested below:

Responsibilities before class:

E 1. My purpose is......

E 2. This text is probably about........

E 3. I guessed based on.......

E 4. I know already ............

J 5. I want to learn about ........

J 6. This text’s structure...........

J 7. The main ideas are:........

E 8. The author is trying to .......

E 9. I agree /disagree with the author........

E 10. When I started to read, I tried to ..............

E 11. When I do not understand the sentence or any part of it, I.....

E 12. When there is an important word that I do not understand, I....

J 13. These are questions I will ask (to check my understanding, to get additional information/help, to involve the class in seeing the implications, hypothetical outcomes, ramifications, etc.):

J/E 14. These struck me as unusual...

E 15. ...... helps to understand this text. Responsibilities during class: small group time

1. Share logs with native and non-native classmates.

2. Use extracts from text to illustrate your points.

3. Identify problematic aspects of text & strategies to resolve them.

During whole group sessions

1. Pay attention to new information from classmates & how you can benefit: what strategy works or fails & why.

2. Pay attention to how native speakers address you, each other, and instructor.

3. Indicate that you understand by repeating to yourself or the class.

4. Indicate what seems unclear to you, or where more elaboration is needed.

5. Check to see if others understand you.

Responsibilities after class:

J 1. I now understand/ still don’t understand the author’s way .......

J 2. I agree/disagree with the author’s point ......

J 3. These language structures are important .........

Native speakers of Japanese could become better facilitators if they understood how their roles are meant to help learners and if examples of helpful behaviors are identified by learners and instructors. Gaies (1985 ) identifies several points to consider in evaluating peer tutoring that may focus both the tutor and tutee on specific helping behaviors. Among other factors, levels of cooperation, interest, progress, enjoyment and preparation are points for both parties to consider for evaluation. Furthermore, language specific issues that proved challenging could be more readily addressed by peer tutors who actively model paraphrasing, clarification, requests for elaboration, citation of references, etc., and then document the learner’s responses. Having this information on a continual basis would help both native speakers and the instructor understand non-native students’ language competency threshold levels for each type of reading and to appropriately scaffold the type of help needed.

The instructor’s sensitivity and skill in switching back and forth between languages is another area needing further development. Considerable practice and skill is needed to strike a balance between meeting pedagogical concerns of language practice, both oral and written, and encouraging student voices to be heard and developed as an aide to comprehension.

Connection to writing. Initially, this was the least specified activity, but one that we now recognize as having great potential to solidify the new reader’s own expression of content, effect practice in written expression and grow in awareness of how they structure their own arguments in contrast with the authors and their classmates. More opportunities for students to express themselves in writing could be done to help process readings. For example, charts and graphs could have been used to visually depict narrative structures. Outlines thus generated could be used as basis for writing summaries. Another idea would be to assign one student to compile an outline of everyone’s logs and/or class discussion to close each topic. The final paper could be a revision of previous assignments that have been returned with comments. Throughout these versions, students’ awareness of their own expression, their ability to paraphrase, to use circumlocutory skills, and to use metaphors, illustrations and examples could be heightened to show how these contrast with the authors’ ways. Byrnes (1990) argues for raising students’ awareness of their own culture’s assumptions, behavior, and attitudes from different perspectives before they can be expected to recognize similar features in a foreign language text. However this can be also accomplished by having different views emerge in a cross-cultural setting as proposed here. In fact, when selected readings relate directly to the students’ lives, a catalytic reaction fueled students’ writing. With the above refinements in focus, more cross-cultural observations could be encouraged.

Conclusions

We joined efforts to redefine how a particular university level Japanese program could deal with language practice and literacy in its curriculum.

Through dialogue about the nature of language practice and literacy, we were able to design a fledgling project which will no doubt undergo many more modifications as we learn more from our students. Though an intensive experience, all non-native students became more aware of how they were processing Japanese texts. Overall students were uniformly satisfied with the course and confident in their progress. The native Japanese speakers came to see how American students interpreted texts in ways they had not imagined possible. The native speaking female became very successful in communicating with Japanese learners at a level of mutual comprehension. The instructor felt that the experience taught him to structure his support in more helpful ways for students and promoted further reflection for future versions of this course in which reading practice is realistically supported by developing other skills. This type of research also provided support for Blum to articulate his beliefs in concrete curricular terms and investigate their effects. Far from reaching any single sweeping answer, our efforts have hopefully shed light on how this type of research can lead to the accomplishment of specific curricular goals. Austin became convinced that while difficult to accomplish reading autonomy within one year, it is possible to refine a process that yields students more practice to develop that autonomy in handling all of its complexities: cognitive, social, cultural and linguistic.

Overtime, we both hope that our previously adumbrated efforts will contribute to reshaping instructors’ roles in ways that make reading autonomy an achievable goal, especially in small programs with limited students and resources. To have graduates that are capable of working through their language limitations to achieve comprehension on their own is a worthy goal. We conclude quoting Bruner (1990):

“Language is not acquired in the role of spectator but through use. Being ‘exposed’ to a flow of language is not nearly so important as using it in the midst of ‘doing’” (p.70).

References

Aihara, S. & Parkes, G. (1992) Strategies for reading Japanese: A rational approach to the Japanese sentence. Tokyo: Japan Publications Trading Company.

Alderson, J. C. and Urquhart, A. B. (1984). Reading in a Foreign Language. London / New York: Longman

Altrichter, H; Posch, P & Somekh, B (1993). Teachers investigate their work: An introduction to the methods of action research. London & New York: Routledge.

Austin, T., Nakayama, C. Oda, A., Ley , Y. & Urabe, S. (1994). “A yen for business: Learning Japanese through a business simulation.” Foreign Language Annals, 27(2), 196-220.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research. London/ Philadelphia: Falmer Press

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical. Education, knowledge and action research, Lewes: Falmer.

Carrell, Patricia, Devine, Joanne, & Eskey, David (1991). Interactive approaches to second language reading / edited by. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Chastain, Kenneth and Woerdehoff, Frank (1968). “A Methodological Study Comparing the Audio-Lingual Habit Theory and the Cognitive Code-Learning Theory.” The Modern Language Journal, 52 (5), 268-279.

Freire, P. & Macedo,D. (1987). Literacy:Reading the word and the world. London:Routledge.

Gaies, Stephen (1985). Peer Involvement in Language Learning. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Goodman, Kenneth S. (1982). Language and literacy : the selected writings of Kenneth S. Goodman, edited and introduced by Frederick Gollasch. London/Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Gumperz, John (1982). Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heisig, J. W. (1987). Remembering the kanji II: A systematic guide to reading Japanese characters. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Publications Trading Co., Ltd.

Horiba, Y. (1990). Narrative comprehension processes: A study of native and non-native readers of Japanese. The Modern Language Journal, 74 (2), 188-202.

Hudson, T. (1982). The effects of induced schemata on the “short circuit” in L2 reading: Nondecoding factors in L2 reading performance. Language Learning, 32, 1-31.

Royer, J.M., Bates, J.A., & Konold, C.E. (1984). Learning from text: Methods of affecting reading intent. pp 65-85, In J.C.Alderson and A.H.Urquhart (Eds.), Reading in a foreign language. London: Longman.

Smith, Frank, ed. (1973). Psycholinguistics and reading. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Spyridakis, Jan (1989). Signaling Effects: Increased Content Retention and New Answers—Part II.Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 19 (4), 395-415.

Swaffar, J., Arens, K., & Byrnes, H. (1991). Reading for meaning. An integrated approach to language learning. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Insup Taylor and David R. Olson, (Eds/0 (1995). Scripts and literacy: Reading and learning to read alphabets, syllabaries and characters. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Wells, G. (1993) Text, talk and inquiry: Schooling as semiotic apprenticeship. Paper presented at the International Conference on Language and Content (Hong Kong, December 1993).ERIC Document 371618.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.