DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.186Published:

2003-01-01Issue:

No. 5 (2003)Section:

Research ArticlesValidation of an oral assessment tool for classroom use

Keywords:

Concurrent validity, Inter-rater reliability, communicative competence, assessment tasks, achievement standards, oral assessment rubric. (en).Downloads

References

Bachman, L. (1990) Fundamental Consideration in Language Testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Bachman, L. (1991) `What Does Language Testing Have to Offer?' TESOL Quarterly, 25, 671-704.

Bachman, L. & A. Palmer. (1996) Language Testing in Practice. Oxford: Oxford

University Press

Brown, Gillian and George Yule (1983) Teaching the Spoken Language. An Approach Based on the Analysis of Conversational English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Canale, Michael and Merrill Swain (1980) "Theoretical Bases of communicative Approaches to Second language Teaching and Testing." Applied Lingsuitics 1.

Chalhoub-Deville, M. (1996) Performance Assessment and the Components

of the Oral Construct Across Different Tests and Rater Groups. In Milanovic and Saville, (Eds.): 55-73

Cohen D., Andrew (1994) Assessing Language Ability in the Classroom. Boston: Massachusetts. Heinle & Heinle

Coombe, Christine and Hubley, Nancy (2002) Creating Effective Classroom

Tests. TESOL Arabia Web page.

Fulcher, G. (1999) Assessment in English for Academic Purposes: Putting

Content Validity In Its Place, Applied Linguistics, 20,2: 221-236.

Galloway, V. (1980) Perceptions of the Communicative Efforts of American

Students of Spanish. Modern Language Journal 64:428-33

Genesee, Fred and John Upshur (1996) Classroom Based-Evaluation in Second Language Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Hadden, B. (1991) Teacher and Non-teacher Perceptions of Second Language

Communication. Language Learning 41: 1-24

Kunan, A. J. (1998) Validation in Language Assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Messick, S (1989) Meaning and Values in Test Validation: The Science and

Ethics of Assessment. Educational Researcher 18 (2), 5-11.

Messick, S. (1996a) Standards-based Score Interpretation: Establishing Valid

Grounds for Valid Inferences. Proceedings of the Joint Conference on Standard Setting for Large Scale Assessments, Sponsored by National Assessment Governing Board and the national Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Messick, S. (1996b) Validity of Performance Assessment. In Philips, G. (1996).

Technical Issues in Large-Scale Performance Assessment. Washington, DC:

National Center for Educational Statistics.

Messick, S. (1996) Validity and Washback in Language Testing. Language

Testing 13:241-56.

Moss, P.A. (1994) Can There be Validity Without Reliability? Educational Re-

searcher 23, 2: 5-12.

Muñoz, Ana, Luz D. Aristizàbal, Fernando Crespo, Sandra Gaviria y Marcela

Palacio (2003) Assessing the Spoken Language: Beliefs and Practices. Revista Universidad EAFIT, Vol. 129, Jan-March, 63-74. Medellín, Colombia.

Richards, J. C. (1983) Listening Comprehension: Approach, Design, Procedure. TESOL Quarterly, 17 (2): 219-240

Savignon, S.J. (1983) Communicative Competence: Theory and Classroom Practice. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

Savignon, S.J. (1972) Communicative Competence: An Experiment in Foreign

Language Teaching. Philadelphia: Center for Curriculum Development

Weir, C. J. (1990) Communicative Language Testing. London: Prentice Hall.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 2003-09-00 vol:5 nro:5 pág:139-157

Validation of an oral assessment tool for classroom use

Ana Muñoz T.

apmunoz@eafit.edu.co

Martha Álvarez

ealvarez@eafit.edu.co

Sergi Casals

Segicasals@hotmail.com

Sandra Gaviria

sgaviria@eafit.edu.

Marcela Palacio

opalacio@eafit.edu.co

Universidad EAFIT

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this research study was to examine the rater reliability and the concurrent validity of the Language Center oral assessment rubric (LCR) with the KET (Key English Test) and PET (Preliminary English Test), Cambridge Examinations. Thirty two students from beginning and intermediate levels participated in the study. Validity estimations included both logical and empirical analyses. Results from logical analyses indicated that the rubric has construct validity. Empirical analyses were conducted by establishing patterns of correlations between the two sets of measures. Results showed low correlations between KET and LCR and from moderate to strong among LCR evaluators. Further, strong correlations between PET and LCR were found suggesting that both measure a similar construct. The results indicate the need to adjust the rubric to low level students and to develop teacher education programs where training toward consistency in evaluation will br conducted.

RESUMEN

En este estudio se analizó la confiabilidad interna y la validez externa de un instrumento para medir la producci´n oral de los estudiantes de Inglés. Se realizó un estudio de correlaciones entre el instrumento (Language Center Rubric-LCR) y los exámenes de suficiencia de Cambridge: KET and PET. Treinta y dos estudiantes de niveles básicos e intermedios participaron en el estudio. Los análisis se llevaron a cabo mediante procedimientos lógicos y empíricos. Los resultados del análisis lógico indicaron que el instrumento tiene validez en cuanto al constructo competencia comunicativa. El análisis empírico reveló bajas correlaciones entre el KET y el LCR y buenas correlaciones entre el PET y el LCR. Las implicaciones del estudio indicaron la necesidad de diseñar un nuevo instrumento para la evaluación de los niveles básicos y el desarrollo de programas educativos donde se lleve a los profesores hacia un entendimiento mutuo de los criterios de evaluación oral.

KEY WORDS: Concurrent validity, Inter-rater reliability, communicative competence, assessment tasks, achievement standards, oral assessment rubric.

INTRODUCTION

In an educational context, the decisions made based on test scores may have detrimental effects on the life of a student. As a result, it becomes essential to clearly define what it is we are evaluating and the criteria used to make our judgments. Badly-constructed evaluations are likely to be unreliable and unfair, and, consequently, inadequate for making decisions.

In addition, as Andrew D. Cohen (1994:1) observes, "the assessment of students' language abilities is something on which teachers spend a fair amount of class time" Accordingly, well-constructed evaluations can benefit EFL students (1) by encouraging them in the creation of positive attitudes to-wards their classes and (2) by helping them to master English. The information obtained from evaluation gives teachers the opportunity to revise and redefine their teaching practices and beliefs by providing them with data that may be used in the future direction of their teaching, for planning and for managing their classes.

It is, therefore, of paramount importance that evaluation be systematically done according to specific guiding principles and explicit criteria to ensure that the construct we are measuring is as valid as the instruments designed to assess it.

BACKGROUND

Well aware of the importance of evaluation, the research group of the EAFIT Language Center became interested in investigating the assessment of oral language in the classroom. The interest in oral assessment was partly due to the emphasis given to speaking and listening skills in our classrooms and to the challenges that assessing the spoken language entails.

In 2001, the research group set out to investigate teachers' beliefs and practices in assessing spoken language. In this study, teachers were asked about methods, materials, aspects of oral language, frequency, and reasons for doing assessment. The results indicated that most teachers focused on assessment for summative purposes and that they lacked planning when assessing their students. The implications of this study were 1) the need for educational programs in the area of assessment, and 2) the development of an oral assessment instrument that would allow teachers to have a consensus on similar assessment and feedback practices (Muñoz, et al., 2003).

With these implications in mind, the researchers began to work on the development of a comprehensive method for oral assessment. As a result, based on communicative principles of assessment, the researchers designed a rubric-Language Center Rubric-to measure speaking abilities at all levels of instruction in the Adult English Program. To determine the suitability of this instrument for classroom use, a study of reliability and validity was conducted in 2002. This article presents the procedures and rationales for estimating the rater reliability and concurrent validity of the Language Center Rubric.

THEORETICAL REVIEW

Two measurement qualities are essential to determine the appropriateness of a given assessment instrument, namely reliability and validity. Reliability is defined as consistency of measurement. It can be understood as a function of the consistency across test characteristics: of ratings of evaluators, of scores across different versions of a test or tests given on different dates, etc. The reliability of communicative language tests may be compromised given the qualitative rather than quantitative nature of communicative language assessment and the involvement of subjective judgments (Weir 1990). Raters must agree on the marks they award and use the marking scheme in the way it was designed to be used. Sufficiently high rater reliability for test results to be valuable can only be obtained by means of proper training of the raters, the use of a functional rating scheme, and tasks that lend themselves to promoting agreement among raters.

Once a test has sufficiently high reliability, a necessary condition for test validity is met, according to Bachman (1990). In this view, both test qualities -reliability and validity- can be interpreted as interrelated, as they are concerned with identifying, estimating, and controlling the effects of factors that affect test scores. Another view is held by Moss (1994), who claims that there can be validity without reliability and believes that occasional lack of reliability does not necessarily invalidate the assessment, but rather poses an empirical puzzle to be solved by searching for a more comprehensive interpretation.

Test validity then refers to the degree to which the inferences based on test scores are meaningful, useful, and accurate. In order to validate a test, empirical data must be collected and logical arguments put forward to show that the inferences are appropriate. Traditionally, three main aspects have been identified in order to organize and discuss validity evidence: criterion validity (relatedness of test scores to one or more outcome criteria), content validity (relevance of test items in that they represent the skills in the specified subject area) and construct validity (determining which concepts or constructs account for performance on the test).

However, validity is increasingly viewed as a unified concept (Bachman 1990; Fulcher 1999, Kunnan 1998; and Messick 1989, 1994, 1996a, 1996b), evidence for which includes six interdependent but not substitutable aspects-content, substantive, structural, generalizability, external, and consequential validity (Messick 1996b). This unitary entity takes into account both evidence of the value implications of score meaning as a basis for action and the social consequences of score use. These two aspects are essential in the process of construct validation, defined as "on-going process of demonstrating that a particular interpretation of test scores is justified, and involves, essentially, building a logical case in support of a particular interpretation and providing evidence justifying the interpretation." (Bachman 1990: 22).

According to Messick (1996c:43), validity is "the overall evaluative judgment of the degree to which empirical evidence and theoretical rationales that support the adequacy and appropriateness of interpretations and actions based on test scores or other modes of assessment." From an empirical point of view, validity of a language test can be examined by looking at the correlation between students' scores on the test being examined to other scores from a similar and already validated test (concurrent validity). Concurrent validity focuses on the degree of equivalence between test scores. If the correlations are high, it is said that the two tests measure the same language ability while low correlations suggest this is not the case.

Messick (1989) describes two possible sources of invalidity: construct under-representation, and construct-irrelevant variance. The former indicates that the assessment tasks overlook important dimensions of the construct. The latter indicates that the assessment tasks contain too many variables, many of which are irrelevant (either too easy or too difficult) to the interpreted construct.

Task design is therefore of utmost importance, since it may affect the interpretation of a test score. A critical quality of assessment tasks is authenticity, defined as "the degree of correspondence between the assessment tasks and the set of tasks a student performs in a non-test (instructional) situation" (Bachman and Palmer, 1996). Assessment tasks must be authentic so that they (1) include all the important aspects of the theoretical construct(s) and (2) promote a positive affective response from the test taker. Language learners are more motivated when they are presented with situations faced in the real world and have to construct their own responses (Coombe and Hubley, 1999).

Summary

The purpose of an assessment tool is to provide a means for making appropriate interpretations about a student's language ability. In the development of tests, two test qualities are crucial in determining their appropriateness: reliability and validity. Increasing reliability calls for teacher training programs and an assessment instrument where clear performance criteria and scoring are specified. Validity, on the other hand, looks at the extent to which the interpretations of a test scores truly reflect the ability measured. It is essential then to have a precise understanding of the language ability as well as of the means (tasks) used in eliciting the kind of language assessed.

METHOD

A study of inter-rater reliability and concurrent validity was conducted to determine the appropriateness of the Language Center Oral Assessment Rubric. Both logical and empirical procedures were followed.Logical procedure

The logical or theoretical analysis involved: 1) Definition of the construct oral language ability, and 2) the specification and validation of assessment tasks. Both procedures will be briefly described below.

1. Definition of the construct oral language ability or communicative competence

The models that were followed in the definition of the construct are based on those proposed by Canale and Swain (1980), Savignon (1970, 1983), and Bachman (1990). Their models, adapted to the Language Center context, may be summarized as follows:

Communicative competence is demonstrated through the ability to communicate and negotiate by interacting meaningfully and accurately with other speakers. In other words, language ability requires that students be able to:

- Express ideas with linguistic accuracy in appropriate contexts

- Interact with peers in a dynamic process

- Express intended communicative functions

Linguistic accuracy measures pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary and how these aspects are used in relation to different contexts and interlocutors. The interactional aspect, or discourse competence, looks at students' ability to express, interpret and negotiate intended meanings (request for clarification, confirm information, check for comprehension, etc.). It also measures the ability to either initiate or sustain a conversation and the ability to use strategies to compensate for breakdowns in communication. The functional knowledge focuses on the ability to produce and respond to different types of speech acts -requests, apologies, thanks, invitations, etc..

All these abilities are reflected on the oral assessment rubric which includes a 1-5 scoring scale, performance descriptors, and linguistic (vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar) as well as strategic, discourse, and sociolinguistic aspects of language (communicative effectiveness and task completion). These aspects are described below:

- Communicative Effectiveness: ease with which students deliver a message (smooth flow of speech). It also measures students' ability to usestrategies to compensate for communication breakdowns and to initiate and maintain speech going. Features to keep in mind: Pausing/Hesitation (too long, unfilled pauses, chopped language); strategies such as circumlocution, self-correction, rephrasing, mGrammar: level of accuracy of previously studied structures. Students' grades should not be affected by lack of control of currently studied structures since such structures are not yet internalized. Features to keep in mind: form, word order, verb tense, subject-verb agreement, subject omission, etc.

- Pronunciation: ability to recognize and produce distinctive meaningful sounds, including consonants, vowels, tone patterns, intonation patterns, rhythm patterns, stress patterns, and any other suprasegmental features that carry meaning. Accent should not be penalized unless it interferes with communication. Features to keep in mind: Articulation (consonants, vowels/word endings, mumbling).Prosodics (rhythm, intonation).

- Vocabulary: extent to which the student uses vocabulary accurately, reflecting sufficient variety and appropriateness for the level and appropriateness to the context and interlocutor. Students should be able to incorporate vocabulary from previous levels. Features to keep in mind: rich vs. sparse, word choice, specific terminology, target-like phrasing.

- Task Completion: Accomplishment of the assigned task. A task is completed when students:

-Develop ideas with sufficient elaboration and detail (important information is not missing)

-Stick to the requirements (or steps) of the assigned task

The definition of the construct also included the specification of the speaking standards established for each level of instruction at the Language Center. The speaking standards clearly state what a student should be able to do in terms of oral language as a result of teaching. The purpose of specifying standards was an attempt to define speaking requirements of students in the academic setting.

2. TASK SPECIFICATION AND VALIDATION

Since the interpretations of a test score are affected by the set of tasks that are used to measure language ability, the logical estimation of validity also involved the specification of the tasks to be used for assessment.

In order to specify authentic assessment tasks, the researchers designed a series of tasks based on the speaking standards established for the different levels in the Adult English Program. Among the most important observations revealed in the task design process was that teachers need to clearly structure the assessment paying careful attention to 1) the selection of the task (considering the standard(s) to be assessed, the level of difficulty, and the degree of authenticity), 2) the contextualization of the task (Where does the task happen? When does it happen? Who is involved in the situation? What resources are necessary to carry out the task?), and 3) the preparation of clear instructions so that students understand what they need to do (details and information teachers want the students to include in the task).

The designed tasks include cued-descriptions, oral reports, interviews, information gap, problem solving, narration, giving instructions, and role-play. It is important to note that the tasks do not constitute an assessment battery. They are intended to be used as examples in teacher training programs where teachers will be instructed on how to plan and design valid assessment tasks.

Validation of tasks was done by a group of five teachers who worked collaboratively in revising and analyzing the assessment tasks with the help of the following guiding questions (adapted from Richards, 1983: 219-240, and Genessee and Upshur, 1996):

- Does the activity measure speaking or something else?

- Does the activity assess memory? (retrieving from long term memory)

- Does the assessment activity reflect a purpose for speaking that approximates real-life? (is the activity authentic?)

- Is the activity appropriate for the level it is intended to? (too easy, too difficult?)

- Is the activity understandable with respect to expected performance?

- Does the activity elicit the kinds of language skills established in the standards?

EMPIRICAL PROCEDURE

An empirical analysis was conducted by establishing correlations between the Language Center Rubric (LCR) and the speaking components of the Key English Test (KET) and the Preliminary English Test (PET), Cambridge examinations. Participants in the study were 14 students from levels 1 to 4 (beginners) who took the KET; and 18 students from levels 5 to 10 (intermediate) who took the PET. Both groups of students came from the Adult English Program.

All the students were interviewed and scored by a trained native speaker rater. The interviews were videotaped and later evaluated, individually, by four Language Center EFL teachers using the Language Center Oral Assessment Rubric. Due to the size of the sample and to the fact that the inferences made based on this study will be limited to the classroom setting, a level of significance at a 0.10 was established.

DESCRIPTION OF THE TESTS

The KET represents Cambridge Level One (of five). In the speaking test, candidates are examined in pairs. The test consists of two parts, lasting a total of 8 - 10 minutes. In Part 1, candidates relate personal factual information to the interlocutor, such as name, occupation, family, etc. In Part 2, the candidates use prompt cards to ask and give personal or non-personal information to each other. Marks are given on a 1 - 5 point scale for each of the two parts of the test by considering candidates' interactive skill and ability to communicate clearly in speech and also on their accuracy of language use -grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation.

The PET represents Cambridge Level Two (of five). In the speaking test, candidates are examined in pairs. The PET speaking test lasts 10 - 12 minutes and consists of four parts which are intended to elicit different speaking skills and strategies through interactional tasks. In Part 1, candidates relate personal factual information to the interlocutor, such as name, occupation, family, etc. Part 2 takes the form of a simulated situation where candidates are asked to make and respond to suggestions, discuss alternatives, make recommendations and negotiate agreement with their partner. In Part 3, candidates have to describe a photograph. Part 4 is an informal conversation where candidates can express likes and dislikes. Throughout the test grades are awarded for the following aspects:

Grammar & Vocabulary - This refers to the accurate and appropriate use of grammatical structures and vocabulary in order to meet the task requirements at PET level.

Discourse Management - At PET Level candidates are expected to be able to use extended utterances where appropriate. The ability to maintain coherent flow of language over several utterances is assessed here. Pronunciation - This refers to the ability to produce comprehensible ut- terances to fulfill the task requirements.

Interactive Communication - This refers to the ability to take part in the interaction and fulfill the task requirements by initiating and responding appropriately and with a reasonable degree of fluency. It includes the ability to use strategies to maintain or repair communication.

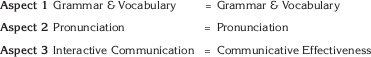

(KET & PET descriptions adapted from: Cambridge Examinations, Certificates, and Diplomas Handbook, 2002) Construct Comparison between the KET and the LCR

To establish correlations, the Language Center Rubric (LCR) was equated to the KET speaking component as follows:

Multiple mean comparison and Pearson product moment correlations were calculated between the KET and the Language Center Rubric (LCR). ANOVA at a 10% level of significance indicates that there are not significant differences between the LCR and the KET (P-value = 0.0792). However, a multiple range test indicates that the KET evaluator tends to assign higher scores (mean = 3.46) than Language Center Evaluators (highest mean = 3.07).

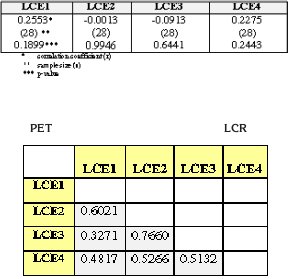

The correlation results indicate low correlations between the LCR and the KET and from moderate to strong correlations among the four Language Center Evaluators (LCEs). Tables 1 and 2 summarize these correlation analyses.

Table 1. Pearson Correlations between KET and LCR - Aspects 1 and 2

Table 2. Correlation coefficients among LCEs - Aspects 1 and 2

While p-values for all the pair of variables are below 0.01, the pair LCE1 - LCE3 shows the highest correlation p-value, 0.089, meaning that it is the weakest correlation. Nonetheless, it is lower than the established a (0.10).

Construct Comparison between the PET and the LCR

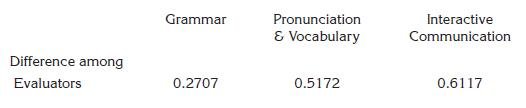

Discourse competence was not included in the analysis because the PET and the LCR look at different abilities through this competence. While the PET looks at coherence in the flow of speech, the LCR focuses on the ability to interact and maintain conversation, traits which are measured by Communicative Effectiveness Correlations were calculated both through mean score comparison and Pearson correlations. Mean comparison by One Way ANOVA, considering all aspects and all evaluators, indicates that there are not significant differences between the scores of the four LC evaluators and the PET evaluator at the 90% confidence level (P-value = 0.0722). However, the PET evaluator tends to assign higher marks (mean = 3.5) than the LCEs (highest mean = 3.2). Furthermore, there are not statistically significant differences between the mean scores of the Language Center evaluators at the 95% confidence level. Additionally, an analysis of variance per aspect, given in Table 3, reveals that there are not statistically significant differences between the mean scores of all the evaluators at the 95.0% confidence since P-values are greater than 0.05.

Table 3. ANOVA per aspect between PET evaluator and LCEs

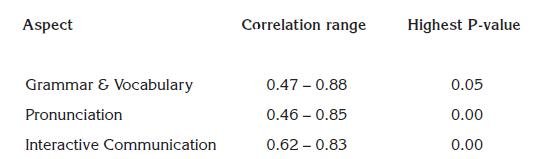

The results of the correlation analysis indicate significant correlations between the LCR and the PET for the three aspects with the highest correlation range for Interactive Communication. Results are given in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary of Pearson Correlations per aspect (PET-LCR)

DISCUSSION

Logical results

The logical analysis indicates that the rubric for oral assessment is a fairly valid instrument. The definition of the construct allowed researchers to make explicit the assessment criteria to be included in the instrument. Both the criteria and the language aspects considered in the rubric are in agreement with the teaching methodology proposed by the Language Center and the theoretical definitions of communicative language competence. This means that the rubric incorporates accurately the attributes that are deemed most important under the communicative competence framework as it is taken at the Language Center.

Having a well-defined concept of the ability to be measured as well as explicit assessment criteria is important because if teachers have a good understanding of them, their expectations of students' performance will be more realistic. Furthermore, they will be in a better position to make appropriate judgments or interpretations about their students' performance in a non-as- sessment situation.

The specification of standards and design of tasks revealed important implications for valid and reliable assessments. For instance, in order to reduce unreliability, performance standards need to be clearly stated so that minimal interpretation on the part of the teachers is done and a shared understanding of these standards is developed. Moreover, following the steps to design an assessment task will allow the teachers to elicit from students extended chunks of speech, thus making the assessment easier and more valid. ";Requiring extended chunks of speech, with support from the inherent structure of a specific task, will give the student experience in being in charge of the speech situation and responsible for effective communication taking place" (Brown and Yule, 1983:118).

Additionally, well structured assessment tasks can guarantee teachers that students' performance may not affected by factors other than the language ability itself. For instance, poor performance may be due to lack of understanding of what is expected, unclear instructions, insufficient time to carry out the task, and misinterpretation on how to carry out the task. All these factors make the task more difficult to assess with consistency and reliability.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

KET and LCR

Concurrent validity between KET and LCR can be called into question on different grounds. First, the constructs of the LCR and the KET are related but different. They are both measuring similar traits of oral language ability but the KET is a direct test that provides an interpretation of overall language proficiency for beginner students, whereas the LCR is a more indirect way of assessing from which inferences about spoken language ability can be made. In other words, the KET focuses only on student performance and the LCR captures more varied aspects of the classroom experience.

Second, problems with the low correlations are most likely due to the inadequacy of the rubric for measuring oral language traits at basic levels of proficiency. It appears that the proficiency standards in the rubric are too high for basic levels. This creates a mismatch between the demands of the rubric and actual students' performance, leading the LCEs to evaluate students harsher than the KET evaluator. Nonetheless, there is evidence of consistency among the LCEs. Inter rater reliabilities range from moderate to strong, meaning that the LCEs have a similar understanding of both the traits being measured and the performance descriptors of the rubric. However, they probably tried to adjust the requirements of the rubric to the performance of low level students, hence, scoring students higher than the external evaluator.

Third, there seems to be differences between the LCEs and the external rater. For this study, mean comparison analysis (both KET, PET and LCR) provide some evidence to support differences between the evaluators. While the external rater marked students high in all aspects, the LCEs had a tendency to mark lower. It is possible that the LCEs and the external rater weigh features in the discourse differently because of their previous experience, training, and unconscious expectations. Thus, it appears quite possible that teacher raters, due to their training in EFL teaching, placed more emphasis on the accuracy of the message, (evaluating students by their correctness, either with respect to pronunciation or to grammar or both) rather than on the communication itself, therefore establishing higher standards of performance.

Several studies have found that that there are differences between the way teachers and non-teachers rate oral proficiency . For instance, Galloway (1980) and Hadden (1991) found that teacher raters tend to evaluate harsher than trained raters particularly on linguistic features. In another study, Chal- houb-Deville, (1996) concluded that both teacher training and experience may influence teacher raters' judgements such that they may differ from non- teacher raters.

PET AND LCR

The correlations obtained from this study provide evidence of concurrent validity. The high correlations suggest that both PET and LCR tap virtually the same sets of language abilities. As such, the language Center might find both of these instruments useful for assessing various aspects of student performance related to communicative competence. More importantly, the strength of the relationship shows that the language ability construct can be judged consistently by both the external evaluator and the LCEs

Interestingly, the highest range of correlation (0.62 - 0.83) is given for interactive communication. Both PET and LCR focus on the students' ability to communicate successfully in spoken language through interactive and strategic competence features. By interacting with each other, negotiation of meaning takes place. The Language Center English program places great emphasis on the negotiative nature of communication because students derive meaning from the ways in which utterances relate to the specific contexts in which they are produced (Savignon, 1983; Bachman and Palmer, 1996). Interaction is, therefore, paramount to language acquisition and as such should be given relevance in assessment.

IMPLICATIONS

The implications of this study are (a) the adaptation of the LCR to the lower levels at the EAFIT Language Center and (b) the design of an appropriate examiners training program in order to optimize the use of the assessment tool (LCR) for intermediate levels.

The results obtained suggest that the LCR proficiency standards for beginners may have been set too high. By consequence, it will be necessary to make adjustments to the rubric to make it an appropriate measurement of low level students, for which the definition of the abilities tested will need to be redefined and the assessment criteria revised. For example, students could be rated for overall communicative effectiveness, grammar, and vocabulary, with pronunciation being somewhat less important and fluency the least important.

As for intermediate students, the LCR proved to be an appropriate assessment instrument. It has construct and concurrent validity and rater reliability. The successful use of this tool (and the revised version), however, implies qualitative training of examiners to enable them to attain adequate reliability levels, which must guarantee that examiners understand the framework and the principles used, the consistent and shared interpretation of the descriptors and the planning of assessment and task design.

The EAFIT Language Center training program consists of three main modules:

(a) Discussion sessions where the communicative approach to communicative language teaching is reviewed and the LCR presented. The aim of these sessions is to give teachers a solid understanding of the principles behind the rating scales used.

(b) Practical sessions in which the trainees are asked to assess videotaped students. After the trainees have assessed individually each of the recordings, group discussion ensues where the grades assigned are looked at in detail and differences among raters debated. At the end of this module, teachers are expected to consistently interpret the descriptors of the rating scale, thus achieving both intra- and inter-rater reliability.

The video recordings used correspond to students at different levels, since it is important that those involved in assessment, teaching, and curriculum development share a similar understanding of the performance standards established at different levels. Such understanding will help to increase the validity and reliability of assessment. In addition, assessments based on specified standards can be used to provide feedback and to inform future teaching and learning needs.

(c) Workshop on assessment planning. Trainees are presented with the basic guidelines of assessment planning and assessment task design. As discussed above, assessment tasks must be authentic and lend themselves to promoting agreement among teachers.

A topic to be explored in further research would be to see how inter rater reliability works in a more flexible situation where the format of the assessment is different from the one proposed by the KET and PET. As reported by Bachman (1991: 674), "the kind of test tasks used can affect test performance as much as the ability we want to measure." In addition to the requirement that any task used has high construct validity, the task must yield results that can be rated unambiguously. Further research is then needed to determine the reliability of classroom assessment tasks.

After the training course, regular workshops will be scheduled in order to guarantee the validity of standards and criteria and the continuing reliability of teacher judgments.

CONCLUSIONS

The writers acknowledge the fact that the limited number of samples and tests included in the study was small. Notwithstanding, the results of this investigation indicated that the LCR has construct validity and that, when used for higher levels, it can show significant reliability and validity against a reference criterion.

Reliability and validity are essential test characteristics. It should be noted though that they are not of an absolute nature. They have a relative importance in that they keep each other in balance. However, to the extent that validity is looked upon as the interpretation of a test score, validity is of paramount importance for classroom assessment. That is, if we take the unitary view of validity (the use of test results determines validity), the implications for the classroom are that validity is a matter of professional responsibility on the part of the teacher: what inferences and actions are to be taken based on test results?

Finally, the development of assessment instruments that are valid and reliable is a complex task. It requires a process of lengthy discussions and modifications that calls for support and encouragement on behalf of all those involved in the educational system, mainly, curriculum developers, teachers, and students.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Bachman, L. (1990) Fundamental Consideration in Language Testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Bachman, L. (1991) ‘What Does Language Testing Have to Offer?’ TESOL Quarterly, 25, 671-704.

- Bachman, L. & A. Palmer. (1996) Language Testing in Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Brown, Gillian and George Yule (1983) Teaching the Spoken Language. An Approach Based on the Analysis of Conversational English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Canale, Michael and Merrill Swain (1980) "Theoretical Bases of Communicative Approaches to Second language Teaching and Testing." Applied Lingsuitics 1.

- Chalhoub-Deville, M. (1996) Performance Assessment and the Components of the Oral Construct Across Different Tests and Rater Groups. In Milanovic and Saville, (Eds.): 55-73

- Cohen D., Andrew (1994) Assessing Language Ability in the Classroom. Boston: Massachusetts. Heinle & Heinle

- Coombe, Christine and Hubley, Nancy (2002) Creating Effective Classroom Tests. TESOL Arabia Web page.

- Fulcher, G. (1999) Assessment in English for Academic Purposes: Putting Content Validity In Its Place, Applied Linguistics, 20,2: 221-236.

- Galloway, V. (1980) Perceptions of the Communicative Efforts of American Students of Spanish. Modern Language Journal 64:428-33

- Genesee, Fred and John Upshur (1996) Classroom Based-Evaluation in Second Language Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Hadden, B. (1991) Teacher and Non-teacher Perceptions of Second Language Communication. Language Learning 41: 1-24

- Kunan, A. J. (1998) Validation in Language Assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

- Messick, S (1989) Meaning and Values in Test Validation: The Science and Ethics of Assessment. Educational Researcher 18 (2), 5-11.

- Messick, S. (1996a) Standards-based Score Interpretation: Establishing Valid Grounds for Valid Inferences. Proceedings of the Joint Conference on Standard Setting for Large Scale Assessments, Sponsored by National Assessment Governing Board and the national Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Messick, S. (1996b) Validity of Performance Assessment. In Philips, G. (1996).

- Technical Issues in Large-Scale Performance Assessment. Washington, DC: National Center for Educational Statistics.

- Messick, S. (1996) Validity and Washback in Language Testing. Language Testing 13:241-56.

- Moss, P.A. (1994) Can There be Validity Without Reliability? Educational Researcher 23, 2: 5-12.

- Muñoz, Ana, Luz D. Aristizàbal, Fernando Crespo, Sandra Gaviria y Marcela Palacio (2003) Assessing the Spoken Language: Beliefs and Practices. Revista Universidad EAFIT, Vol. 129, Jan-March, 63-74. Medellín, Colombia.

- Richards, J. C. (1983) Listening Comprehension: Approach, Design, Procedure. TESOL Quarterly, 17 (2): 219-240

- Savignon, S.J. (1983) Communicative Competence: Theory and Classroom Practice. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

- Savignon, S.J. (1972) Communicative Competence: An Experiment in Foreign Language Teaching. Philadelphia: Center for Curriculum Development Weir, C. J. (1990) Communicative Language Testing. London: Prentice Hall.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.

Publication Facts

Reviewer profiles N/A

Author statements

- Academic society

- N/A