DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.92Published:

2010-01-01Issue:

Vol 12, No 1 (2010) January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesAssessing children ́s perceptions of writing in EFL based on the process approach

Evaluando las percepciones de los niños sobre la escritura en inglés como lengua extranjera

Keywords:

percepciones de los niños acerca de la escritura, escritura en inglés como lengua extranjera, enfoque sobre procesos de escritura (es).Keywords:

children’s perceptions of writing, writing in EFL, process approach (en).Downloads

References

Alejo R. and McGinity M. (1997). Applied languages: Theory and practice in ESP.

Valencia: University of Valencia. Available:

Bräuer, G. (2000). Writing across languages: Vol. 1. Stamford, CT: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Brown, H. (1994). Teaching by principles. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Burns, A. (2001). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, L. & Manion, L. (1994). Research methods in education (4th ed.). London: Routledge.

Elliot, J. (1993). Action research for educational change. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Galvis, A. (2004). A collaborative writing workshop: Developing children's writing in an EFL context. Thesis dissertation, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá.

Garner, R. & Alexander, P. (1994). Beliefs about Text and Instruction with Text. Adolescent beliefs about oral and written language. Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Harmer, J. (2004). How to teach writing. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Hayes, J. R. (1996). A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing. In C.M. Levy and S. Ransdell (eds.), The science of writing. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hayes, J. R. and Flower, L. S. (1980) Identifying the organization of writing processes. In L. W. Gregg and E. R. Steinberg (eds.), Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 31-50). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Henderson, J. & Hawthorne, R. (1995). Transformative curriculum leadership. Columbus, OH: Prentice Hall.

Hyland, K. (2002). Teaching and researching writing. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Kern, R. (2000). Literacy and language teaching. Oxford and New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lombana, C. (2002). Some issues for the teaching of writing. PROFILE Journal (3). pp. 44-51.

Mendoza, E. (2005). Current state of the teaching of process writing in EFL classes: An observational study in the last two years of secondary school. PROFILE Journal (6), pp. 23-36.

Rapaport, W. and Ehrlich, K. (1997). A computational theory of vocabulary acquisition. Buffalo, NY: University of New York. Available: http://www.cse.buffalo.edu/~rapaport/Papers/krnlp.tr.pdf (Retrieved on July 8th,

. Scott, V. (1996). Rethinking foreign language writing. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Seliger, H. & Shohamy, E. (1989). Second language research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Walter, S. (1975). Cloze procedure: A technique for weaning advanced ESL students from excessive use of the dictionary. Menlo Park: California Association of Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. Available:

http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs-sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/33/82/f2.pdf (Retrieved on May 20th, 2009).

Weigle, S. (2002). Assessing writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2010 vol:12 nro:1 pág:70-84

Research Article

Assessing Children´s Perceptions of Writing in EFL based on the process approach

Evaluando las percepciones de los niños sobre la escritura en inglés como lengua extranjera

Daniel Albeiro Melgarejo Melgarejo

Full time English Teacher and Academic Coordinator of the English Area Corporación Universitaria Unitec E-mail: teachermelgarejo@yahoo.com

Abstract

This action research study focused on the analysis of children’s perceptions of writing in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and was grounded in the theory of the process approach. This approach was considered in view of students’ negative perceptions on writing, their lack of motivation to write, and their poor writing skills in EFL. Therefore, a number of cognitive processes such as planning, translating thought into text and revising were included. The children who took part in the study were between 9 and 13 years old and were in the intermediate English level at a language institute in a public university in Bogota. The aim was to consider such perceptions and see how they evolved during the implementation of workshops based on the stages proposed by the process approach. Furthermore, in addition to an analysis of student perceptions, a secondary aim was to motivate students to write and to help improve their written productions. The data gathered through portfolios, conferences, journals and logs showed that the students changed their prior negative perceptions on writing in EFL, felt motivated to carry out writing tasks, and became more self-aware of their writing practices.

Key words: children’s perceptions of writing, writing in EFL, process approach.

Abstract

El presente estudio de investigación-acción se enfoca en el análisis de las percepciones que los niños tienen hacia la escritura en inglés como Lengua Extranjera y se basa en la teoría del enfoque sobre procesos. Se consideró dicho enfoque debido a las percepciones negativas que tenían los estudiantes hacia la escritura, su falta de motivación para escribir, y sus deficientes habilidades para escribir en inglés. Por tal motivo, se incluyeron en este estudio diferentes procesos cognitivos como planear, escribir y revisar. Los niños que tomaron parte de este estudio oscilaban entre 9 y 13 años y estaban en el nivel intermedio de inglés de los cursos ofrecidos por un centro de idiomas en una universidad pública de Bogotá. El objetivo primordial se basó en considerar tales percepciones y analizar su evolución durante la implementación de talleres basados en las etapas propuestas en el enfoque por procesos. Además de analizar dichas percepciones, también se tuvo la oportunidad de motivar a los estudiantes a escribir y ayudarlos a mejorar sus composiciones. Los datos recolectados a través del uso de portafolios, conferencias y diarios evidenciaron que los estudiantes cambiaron sus percepciones negativas preconcebidas sobre la escritura en inglés, y se sintieron motivados para llevar a cabo dichas tareas. Finalmente, los estudiantes tuvieron conocimiento de sí mismos acerca de su desempeño durante los procesos escriturales.

Palabras claves: percepciones de los niños acerca de la escritura, escritura en inglés como lengua extranjera, enfoque sobre procesos de escritura

Introduction

Developing and improving writing skills for students of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) has been a major concern for teachers in Colombia at all educational levels. Many strategies focus on language form and are implemented with the intention of helping students develop writing. Yet, many students face difficulties with the composition at all competency levels and thus, it is necessary to consider a suitable writing strategy that engages students in writing in EFL within the process approach.

This research study focused on analyzing the students’ perspectives on the way they perceived writing in EFL, by engaging them in writing activities that encouraged writing about their favorite topics. The research was grounded in the action research qualitative study and followed the cycles that comprise the process approach.

The main purpose for developing this research came from noticing that children experienced great difficulties when writing in English. Due to the fact that writing has been considered by teachers as a difficult task in which several factors contribute (time, space, guidance, interest, vocabulary, structures, among others), a change of approach from the traditional needed to be implemented in order to experience writing from students´ personal perspectives. A needs analysis was carried out and the results allowed the exploration of the students’ interests based on their perceptions of writing. A pedagogical intervention that explored the stages of the process approach through a series of workshops was implemented with students during one semester. A participatory approach for topic selection allowed students to take part in the decisions made in the classroom and to examine how their perceptions of writing in English were evolving.

Theoretical considerations

Writing in EFL

Writing has been seen as one of the major challenges that individuals have to successfully overcome in any academic community. Moreover, writing in a foreign language becomes more complex because it requires composition skills in a language different from the mother tongue, a mastery of the rhetorical patterns of the foreign language and an awareness of the differences that exist among languages and writing styles.

One of the major difficulties of teaching writing in EFL classrooms is the lack of practice students have when writing in the target language outside the classroom (Mendoza, 2005). This concern arises from the fact that many institutions base their curricula on the communicative approach, but the communicative approach promotes especially oral communication skills. Therefore, writing practices are not as relevant as they should be in order to become a good writer in EFL.

It is important for teachers to be aware of the purposes of writing in EFL. Lombana (2002) argues that in many situations “the problem is to see the purpose of the writing skill and how to teach it in such a way that the writing tasks become realistic and relevant” (p. 49). Hence, writing in EFL must be seen as much more than practicing and improving new structures, but must recognize that writing is a means of communicating ideas successfully to people from other cultures.

Studies carried out by Bland, Noblitt, Armington and Gay (1990) found that “in the early stages of learning to write in a new language, learners’ thinking tends to be dominated by lexical rather than syntactic issues” (as cited in Kern, 2000, p. 177). Therefore, students find it difficult to produce any piece of work because they lack enough vocabulary which limits their compositions and does not allow them to thoroughly express themselves. Kern (2000) also states that many studies have demonstrated that students rely heavily on genres and rhetorical organization patterns that they originally learned in their native language to facilitate the writing process. Uzawa and Cumming (cited in Kern, 2000) state that the students “borrow” specific lexical items and tend to put a lot of effort, use extra time to compose, seek assistance on word choices on grammar and revise texts extensively.

Despite the previous concepts by Uzawa and Cumming, Kern believes that “writing is thus most usefully defined not in terms of uniform, universal processes, but rather in terms of contextually appropriated practices. What is clear from the research literature is that the ability to write in a second language does not necessarily follow in any direct way from native language writing ability” (2000, p. 180). As Kern states, it is important to consider that writing in EFL does not necessarily follow the same patterns as the native language but on the contrary, it must be taught, which leads us to consider the process approach as the means to fulfill this purpose.

Another perception to be taken into account according to Gelb, cited by Galvis (2004), is that “full writing systems are characterized by a more or less fixed correspondence between the signs of the writing system and the elements of the language that writing represents” (p.38). Of course, children tend to take elements belonging to their native language to construct meaning, which is something helpful when producing different compositions. Nevertheless, it is necessary to guide children during the process by scaffolding their writing and providing support so they can build self-confidence and experience writing through the drafting, revising, and editing stages of the process.

Writing process oriented approach

Writing has been studied from a large number of perspectives and analysed by different approaches like the product approach, the genre approach or the process approach. As the intention of this research project dealt with the development of certain skills to master writing in EFL, I concentrated on the process approach and explored the stages of drafting, revising and editing, which permeate the writing development during all the process.

The first influential model of the process approach was the one proposed by Hayes and Flower (1980). Hayes and Flower described the writing process in terms of “the task environment, which included the writing assignment and the text produced so far, the writer’s long-term memory, including knowledge of topic, knowledge of audience, and stored writing plans, and a number of cognitive processes, including planning, translating thought into text and revising” (as cited in Weigle, 2002, p.23). Later on, this model was modified by Hayes in 1996, incorporating two major components: the task environment, which includes a social component, the audience and a physical component, and the individual environment, which includes motivation and affect, cognitive processes, working memory, and long-term memory. A remarkable aspect of this new organization of the Hayes model is the inclusion of motivation and affect which play central roles in writing processes along with the cognitive onesimplemented and judged by other researchers who were also interested in studying such processes.

The process approach also has some characteristics that are of great advantage when discovering its purposes. Shih, 1986 (as cited in Brown, 1994), suggests that this approach focuses on the process of writing that leads to the final written product, helps students writers to understand their own composing process, helps them to build repertoires of strategies for prewriting, drafting, and rewriting, gives students time to write and rewrite, places central importance on the process of revision and lets students discover what they want to say as they write. It also provides students with feedback throughout the composing process (not just on the final product) as they attempt to bring their expression closer and closer to intention, encouraging feedback from both the instructor and their peers.

All the characteristics above fit appropriately in the idea of seeing writing from a perspective in which the students feel that they are participating in a course of action which allows them to choose what to write about. Consequently, they get involved in meaningful activities that guide them towards having a broader view of what writing is.

During the process approach, students can not only record thoughts, feelings and ideas, but also generate and explore new thoughts and ideas. This process has the advantage of being student-centered so he/she has the possibility to reflect upon his/her own process by means of using an alternative assessment form such as the portfolio. Portfolios allow students to express their ideas, thoughts, beliefs, concerns, reflections, etc., following certain stages as brainstorming, drafting, revising, editing and socializing as they work collaboratively with their peers (Kern, 2000).

Children’s beliefs towards writing It is true that teachers need to consider their students’ beliefs about writing so they contribute to a better understanding of the children’s world facilitating their literacy development processes and to consider their views in order to analyze the world the students are immersed in. I concur with Schoomer (1994) when she states that “beliefs are too important to ignore” (as cited in Garner and Alexander, 1994, p. 38). Teachers cannot disregard the aspects that are significant to writing itself. When writing, we can not just limit our teaching practices to focus on the form and the content without observing the students as individuals who incorporate a variety of beliefs into their compositions.

“Beliefs may be conceived as minitheories of the mind, ways of characterizing language and behavior and ascribing mental states to people. Beliefs are, I believe, profoundly personal and delicate constructs that represent convictions” (Horowitz, 1994, in Garner & Alexander, 1994, p. 3). When considering beliefs, it is necessary to associate them with other aspects such as assumptions, knowledge, commitments, attitudes and feelings (Wade et all, 1994 in Garner & Alexander, 1994). Even though, many psychologists subsume beliefs under attitudes because they are considered to be the building blocks of such attitudes (Dole & Sinatra, 1994, as cited in Garner & Alexander, 1994). Therefore, to consider and judge children’s compositions, it is necessary to reflect not only on the mental processes carried out to produce any piece of writing, but also to take into account the system of beliefs, perceptions, ideologies, thoughts, feelings and attitudes behind their compositions. Every time a person writes, he or she assumes a position from which he or she sees and interprets the world and the topics he or she has selected to write about.

Methodology

Context and participants

This research project was carried out at a Language Institute in a public university in Bogota, which offers extension courses for learning foreign languages like English, French, German and Portuguese. The language levels offered to students range from Basic I to Conversation and the students are divided into three main groups: adults, adolescents and children. The participants of the study included 21 children between the ages of 10 and 13 with an intermediate level of English. They were selected firstly for their English level and secondly because of their experience in writing in EFL from the basic levels. Thus, they were able to give opinions and share their thoughts about writing while participating in the project.

Since this project was based on the qualitative paradigm and was an action research study (Seliger & Shohamy, 1989; Cohen & Manion, 1994; Burns, A., 2001; Elliot, J., 1993), the implementation of workshops and the monitoring of the stages, moments and cycles were crucial throughout the process.

Data Sources

The first step was to carry out a needs assessment in order to elicit the students’ preferences for writing in EFL. The workshops could then be designed according to such interests. Each session was focused on a topic and a different piece of writing was developed following the stages of the process approach which included brainstorming, drafting, revising, editing and socializing. Collaborative work was important on account of relying on the students’ support throughout the composing and editing time.

The portfolio became the most powerful tool to analyze the students’ compositions and with the use of different instruments like conferences, journals, and reflective logs, data collection was possible and allowed the analysis of their insights after each activity regarding their perceptions and feelings about their writing progress.

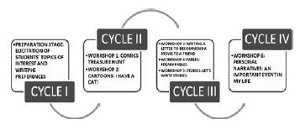

The following figure summarizes the cycles and the workshops held during each session.

Findings

The results that arose from this research could be clearly defined by understanding the students’ change in perceptions of writing in EFL as seen from two identified areas: motivation and interest to write and writing skill improvement, which led to a very important aspect related to self-awareness

Motivation and interest

Motivation undoubtedly plays a significant role for any writer. Inspiration is necessary to carry out production tasks. It is not enough just to have the elements pertinent to writing itself, but you need to feel passion and interest to write about a topic. Obviously, when writers are motivated to write, the results are much better partially stemming from a desire to read the drafts over and over again, editing them as many times as necessary until creating the piece of work intended from the beginning. Despite the fact that teachers need to spark the students’ interest in writing by using a variety of motivational strategies, it is ultimately the student who needs to find within him or herself the real passion to write.

As Hyland (2002) states “successful writing instruction requires an awareness of the importance of cognitive and motivational factors, which means teachers should provide relevant topics, encourage cooperation with peers in planning and writing tasks…” (p. 80). Therefore, if one of the purposes is to get students deeply involved in the practice of writing, considering the aspects that motivate them to write according to their own experiences, ideas and cultural background becomes necessary. Jairo, one of the participants said during one of the conferences:

J: “Because cartoons are one of the things I like the most and using them is a good way to learn”. (Jairo : Conference 1, 21/10/06)

It is important, as Harmer (2004) says, that we choose writing activities that are appealing to the students, and if possible, that are relevant to them. Asking students about their interests becomes crucial to designing the workshops to be implemented during the course. Students are the center of any classroom practice and, therefore, they are the ones who have the right to say what should be included at least as far as the writing genres and/or topics. Laura reinforces this idea by saying that:

L: “…we have had lots of recreational activities which make the class less monotonous”. ( Laura: Log, 02/12/06)

If using different recreational activities lead to a better understanding and deeper learning process, then we need to include them as part of our classroom practices. The teacher must incorporate the grammatical content according to the type of writing activity the students have chosen to do, and as Harmer (2004) stated, which are appealing to them. Thus, taking into account students’ voices is in accordance with the foundations of the Transformative Curriculum which emphasizes the participation of many actors in the academic community to decide upon the elements to be included in the curriculum. Such actors involve not only the teachers but also coordinators, administrative staff, even parents and, of course, students. As Henderson Translated by the author. and Hawthorne (1995) state, “the design (of a curriculum) is a common referent for teachers, classrooms, parents, and the community that coherently states goals, basic content, and forms of teaching and learning” (p. 82).

Learning a foreign language must be fun, interesting and effective. The more motivated the students feel, the more focused they are on the task, the more they learn and, consequently, the better the results will be. Such motivation fosters students’ creativity and their ability to express it. Aníbal and Laura quote in their journals:

A: “You can use your imagination and creativity at a higher level”. (Anibal: Journal 1, 23/09/06)

L: “I learned to develop my creativity”. (Laura: Journal 3, 28/10/06)

When students are aware of the importance of using their imagination in such a way that it engages them more effectively in the learning process, it increases their self-confidence. Once they are excited by the tasks, they want to work making it easily achievable and entertaining.

Learning to write involves many steps which need to be evaluated with consistency at every stage of the process. Feedback must be obtained not only from the teacher but also from the students’ peers and from the students themselves as well. If such steps are fulfilled persistently and according to a chronogram, the results will illustrate a step-by-step progress in their writing performance, which will give students a sense of improvement increasing their self-esteem. Some samples that support this concept are shown below:

E: “And you don’t feel anymore what you felt before… that feeling of reluctance towards writing changed and now writing is a nicer activity since you know how to do it and you start feeling differently”. (Eric: Conference 3, 02/12/06)

P: “The results are better and I try harder in order to learn to write English perfectly”. (Patricia: Journal 4, 04/11/06)

C: “Taking into consideration my motivation to write in English, I consider myself to be more motivated since I know more vocabulary and more grammar and in that way I can write faster”. (Claudia: Log, 02/12/06)

Such motivation also conducts to a positive feeling of learning languages. Students understand the importance of speaking English, not only for academic purposes but for a variety of reasons including traveling, getting to know foreign people, and even job opportunities in their future. It is very interesting to observe that with time, students start considering the importance of learning a different language. Patricia, one of the most outstanding students in the class, states in one of the conferences:

P: “Well, first of all I think that this writing process is nice because you are getting to know another language and express your ideas in different ways. As my classmate said before, English is the universal language so, you need it wherever you go. Besides, writing in English is easier than in Spanish and the ideas are shorter, less complex and more concrete” (Patricia: Conference 3, 02/12/06)

In a similar vein, Laura and Aníbal note:

L: “I consider my motivation to write in English is good because I like languages a lot and I want to learn them perfectly” (Laura: Log, 02/12/06)

A: “…my writing and my comprehension levels have improved, and I have also understood the importance of the English language” (Aníbal: Log, 02/12/06)

Working through the stages of the process approach creates increased interest in English and students’ self-awareness, allowing students to be active participants since the deciding stage inspires them, and it foments their initiative to continue working on their writing development. Hyland (2002) says that “an awareness of writer issues also means that we must consider ways of engaging writers by providing relevant topics, clear goals and strategies to make writing tasks manageable. Successful writing instruction requires an awareness of the importance of cognitive and motivational factors, which means teachers should provide relevant topics, encourage cooperation with peers in planning and writing tasks, and incorporate group research activities of various kinds”. (Hyland, 2002, p. 80).

EFL Writing Improvement

Undoubtedly, the use of the portfolio during the research project carried out with the students showed to be very effective during their writing process. Besides, it allowed the application of the stages of the process approach, which supported all the workshops carried out during the writing sessions. As a result, the students’ writing performances improved greatly and can be highlighted in two main areas: vocabulary building and appropriation of grammatical elements.

Vocabulary building

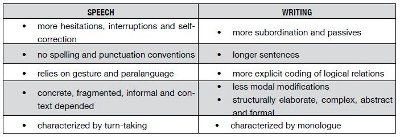

Studying a foreign language requires time, dedication and effort. If students realize the importance of speaking a different language and are committed to learning it, they will end up obtaining positive results. Such dedication and effort help them improve little by little the necessary skills to read, listen, speak and write appropriately a foreign language. In the specific case of writing, most of the students face different problems when trying to convey their ideas than with the other skill areas, since this skill needs to be practiced frequently to ensure potential readers will understand the writer’s intention. In other words, if a writer is not clear enough, the reader may misunderstand –or in worse cases, not understand at all- the writer’s ideas. As Hyland (2002) explains, “Speech is more highly contextualized, depends far more on a shared situation, allows less planning, involves realtime monitoring, and relies to a greater extent on immediate feedback” (p.49). Such differences are shown in the table above.

Since writing requires more time and more planning, students need enough tools to convey meaning when expressing their concepts on paper. However, one of the students’ “barriers” to communicating their ideas is a lack of vocabulary. Every class, every task and every exercise carried out in class requires the students to know the appropriate vocabulary. They may know the structure well enough, but if they do not know how to write a specific word in English or they are not able to choose the appropriate word from the several possibilities that are found in the dictionary. They then start having problems putting their ideas on paper. Koda’s (1993) research suggests that “there is a strong correlation between vocabulary knowledge and text quality...vocabulary knowledge contributes substantially to FL composition...teaching writing should include vocabulary exercises to provide a ‘linguistic scaffolding’ for a given task” (as cited in Scott, 1995). Therefore, despite the fact that as teachers know this type of activity is extremely time consuming, ideally most of the writing tasks should be done during classroom sessions.

Another problem students face during writing time is the “excessive” use of the dictionary. Walter’s publication (Walter, 1975) shows that relying heavily on the use of a dictionary makes students slow down tremendously in their learning process as they spend too much time on individual words losing sight of the overall meaning of the sentence or passage they are either reading or trying to construct. Hence, such dependence will hinder –not help- the students as they attempt to read with understanding. As teachers, we need to dedicate some time to design workshops on how to use a dictionary. I have seen during my experience that many students do not know how to use a dictionary properly, even in Spanish. Therefore, it becomes mandatory to help them use it, give them tips on how to find a word and, most importantly, which word is the most appropriate according to the specific context. After that, it is important to continue “recycling” the words so students do not forget them but continue using them in different tasks and contexts, not only in the written form but also orally. Erika refers to the use of the dictionary by saying:

E: “At the beginning of the process I didn’t know much vocabulary so I had to rely a lot on the use of the dictionary. Now I still use it but I know a lot more words”. (Erika: Log, 02/12/06)

Obviously, speaking another language does not mean that we are “human dictionaries” and know the meaning of all the words. It does not happen even in the native language. Therefore, it is really important to give students hints on how to find a word and select the word that is the most suitable according to the context. It is also important to highlight, that the input received from readings and listening activities becomes crucial in an adequate learning process of a foreign language. The more students are in contact with the language studied, the better. In the opinion of Freddy and Jessica, learning new words helps them to refine their compositions and, at the same time, builds self-confidence in terms of vocabulary knowledge.

F: “I improved my vocabulary because I learned more meanings and words by doing these workshops”. (Freddy: Conference 2, 04/12/06)

J: “I agree because this semester I learned many words and verbs I didn’t know before. It means I didn’t have good vocabulary but now I do, which is good”. (Jessica: Conference 3, 02/12/06)

Ángela, making an analysis on the way she felt at the beginning due to the problems that arose from her poor vocabulary and grammar usage, gives the following opinion:

A: “I think the workshops have been of great help since before we could not express some ideas due to the lack of vocabulary or our poor grammar structures. Everything was boring but now, since we know more vocabulary we have improved and we don’t make many mistakes when expressing our ideas with fluency and logic.” (Ángela: Conference 3, 02/12/06)

Such lack of vocabulary then, according to Ángela, implies that the vocabulary gap must be filled in order to convey meaning and that it also addresses issues such as the students’ attitude towards writing. When they feel they cannot easily express themselves due to an inability to find the words necessary to convey their ideas students might feel bored and start showing a negative attitude towards the tasks assigned and the class in general. As long as the students start acquiring the vocabulary needed to complete their assignments, they begin to feel a sense of accomplishment as they are able to complete the tasks in a short time and with better results. In this sense, Ángela says she has improved by learning from her mistakes and now can express her ideas with more fluency and logic. That is to say, the process carried out during the workshops within this research project contributed to students’ improvement thanks to the use of the portfolios which had a positive impact on the students’ writing performance. To support this idea, Luisa and Cristina quote:

L: “At the beginning of the process I didn’t use the vocabulary appropriately and I didn’t have clear some complex ideas or expressions. At this point I can use my vocabulary in a better way and I know the meaning of new words” (Luisa: Log, 02/12/06)

C: “At the beginning of the process I had few ideas and I didn’t know how to express myself. Now my ideas are more fluent and I can express myself better with the new words I have learned” (Cristina: Log, 02/12/06)

Both participants agree on the fact that at the beginning of the process their vocabulary was really poor. Their lexicon was very basic and, as a result, when they wanted to write they had difficulties doing so. After participating in the workshops, they felt their vocabulary had improved meaningfully and that they could express their ideas in a more appropriate way.

There are diverse ways to help students build vocabulary. It is the teachers’ responsibility to make use of different resources to aid students in improving their vocabulary. It is not enough to memorize lists of words out of context resulting in a lack of understanding of when and how to use them. Fortunately, new theories such as the Computational Theory of Vocabulary Acquisition (Rapaport & Ehrlich, 1997) have been discovered giving teachers many strategies to help students construct their vocabulary lexicon. This theory holds the view that “natural-language-understanding systems can automatically acquire new vocabulary by determining from context the meaning of words that are unknown, misunderstood, or used in a new sense. ‘Context’ includes surrounding text, grammatical information, and background knowledge, but no external sources” (p.1). Their thesis is that “the meaning of such a word can be determined from context, can be revised upon further encounters with the word, “converges” to a dictionary-like definition if enough context has been provided and there have been enough exposures to the word, and eventually “settles down” to a “steady state” that is always subject to revision upon further encounters with the word.”

Rivers (1983) in Alejo and McGinity (1997) argues that, “Vocabulary cannot be taught. It can be presented, explained, included in all kind of activities and experienced in all number of associations but ultimately it is learned by the individual” (p. 216). This is to say that it is the students who ultimately have the responsibility to learn the new words by using the strategies suggested by their teachers during classes and outside the classroom as well. Of course, students need motivation which is intrinsically connected to the topics they are writing about. Since students require motivation to write, it becomes crucial to implement motivational strategies such as cooperative work, modeling, computer use, games, multiple intelligences use, minds-on and hands-on opportunities, among others.

Appropriation of grammatical elements

Being a good writer in both the mother tongue and the foreign language requires skillful handling of the many elements pertinent to the type of composition to be done. Each type of composition (essay, article, story, review, etcetera), needs appropriate vocabulary, connectors, and the correct use of punctuation marks as well as the development of a set of parameters related to each type of composition (for example: introductory paragraph, body and conclusion). However, all these elements need to be structured in such a way that they can be readable and understandable by the potential readers. This is to say that a writer may have a good corpus of ideas and a vast lexicon, but if he or she does not have the ability to convey his or her ideas into a well-structured piece of writing, the resulting piece will not be successful. To do this, it is absolutely necessary to have the linguistic knowledge which rules the way words, sentences and paragraphs are structured so that the ideas can be conveyed clearly on paper. Grabe and Kaplan’s model (1996) of the taxonomy of language knowledge clearly shows the importance of three different types of language knowledge:

- Linguistic knowledge

- Discourse knowledge

- Sociolinguistic knowledge

Such types of language are all vital during the learning stages, however linguistic knowledge is crucial as it deals with the knowledge of the written code: orthography, spelling, punctuation and formating conventions; the knowledge of phonology and morphology: sound/letter correspondences, syllables and morpheme structure; vocabulary: interpersonal words and phrases, academic and pedagogical words and phrases, formal and technical words and phrases, topic-specific words and phrases and non-literal and metaphorical language; and syntactic/ structural knowledge: basic syntactic patterns, preferred formal writing structures, and figures of expression, metaphors and similes (as cited in Weigle, 2002).

Along with the project carried out with the students who took part in this research, it became very relevant for them to be able to connect all the workshops to their learning and reinforcement of a variety of grammatical tenses and topics that were part of the program. Analyzing some of the students’ interviews, students expressed the importance of reinforcing the grammatical structures by using different recreational activities. During one of the conferences, Patricia says:

P: “I think this activity was interesting because we could work cooperatively, learned more and reviewed the topic to be studied which was simple past. I consider we clarified some concepts and doubts we had regarding the past tense and it was nice for everyone”. (Patricia: Conference 1, 21/10/06)

Patricia makes reference to some significant ideas. First of all she mentions how interesting the activities were, how important it was that everybody could work together cooperatively and then explains how crucial the practice of the simple past tense was. Her words clearly state that the workshops guided the students to put into practice some of the structures studied previously in class and connect them to the activities they were carrying out. By means of such connection, learning became more fun, interesting, and triggered the students’ motivation since they could learn new things and resolve any confusion they still had from previous levels.

The students’ awareness about the importance of using the grammar adequately was resounding. Ángela points out the improvement they showed in terms of grammar use. She says:

A: “I learned more about grammar because I had many grammatical mistakes. I had to review and edit my drafts so I learned from my own mistakes in order not to make them again”. (Ángela: Conference 2, 04/12/06)

Ángela’s opinion is very relevant since she realized her mistakes and knew what to do in order to improve her compositions. By revising her drafts, and by using some editing marks which helped her to correct her mistakes, allowing her to not make the same mistakes again. Consequently, it is necessary to give the students the appropriate tools to create a sense of awareness of their writing mistakes with the purpose of building more knowledge and confidence when writing.

Even though students’ improved in regards to the correct use of the mechanics of writing, Hyland (2002) holds the view that absolute accuracy is not the purpose of writing. He argues that “there is little evidence to show that syntactic complexity or grammatical accuracy are either the principal features of writing development or the best measures of good writing” (p. 9). And he adds, “Moreover, while fewer errors may be seen as an index of progress, this is equally likely to indicate the writer’s reluctance to take risks and reach beyond a current level of competence” (p.10). His position of not focusing only on the syntactic competence as an instrument to measure students’ writing improvement is very significant, but it cannot be ignored that when students make less mistakes during their compositions, it helps them improve not only their writing competence but, at the same time, creates self-confidence and motivation to continue writing in EFL. Luisa refers to her writing performance by stating that:

L: “At the beginning of the process I didn’t have good grammar basis; I didn’t use it appropriately and I didn’t take into consideration the grammatical tenses I needed to use in my compositions. At this moment I can use it better, especially the grammatical tenses studied”. (Luisa: Log, 02/12/06)

Luisa’s statement reflects how through the use of the portfolio her compositions turned out to be more elaborate, and she learned to use the grammatical tenses more appropriately. Aníbal and Claudia, other participants of the study, referred to the grammar and vocabulary improvement as well. As it was stated in the first sub-category on vocabulary building, the right connection of these two elements (grammar and vocabulary) makes writing a more well-suited activity. They depict:

A: “Personally, I think I have bad grammar but the workshops helped me improve it as well as my vocabulary”. (Aníbal: Conference 2, 04/12/06)

C: “I feel better because I learned vocabulary and my grammar improved. Not as much as I would have liked but at least I am aware of my mistakes and I try not to make them again”. (Claudia: Journal 4, 04/11/06)

When students start writing in a foreign language, it is common to find some who lack self-confidence in different aspects of the writing process. Aspects such as vocabulary, punctuation, coherence or grammar usage are at the top of the problems. Here, Aníbal stated his own conception as a writer by recognizing that he had problems with using different grammatical elements. Claudia also hinted that she did not have a firm grammar base. However, both participants realized that during the project, they learned how to correct their mistakes leading to a better understanding of the proper use of grammar. Additionally, it is quite relevant to highlight their willingness to continue writing while they avoid making the same mistakes once and again. We can refer here to one of the most relevant statements from the Grammar-Translation method which deals with the grammatical accuracy as being decidedly significant in the writing practices. The problem of this method is that it sees writing only as a means to translate sentences to demonstrate the mastery of vocabulary items or grammatical principles instead of communicating students’ own ideas or thoughts (Homstad & Thorson, as cited in Bräuer, 2000). When Laura compares her writing productions at the beginning of the project to the ones at the end, she also highlights the importance of using the portfolio as an important tool in order to avoid making the same mistakes repeatedly. She says:

L: “At the beginning of the process I think my writing was okay despite my many vocabulary mistakes. Now my writing is better by means of having used the portfolio. This tool has allowed me to correct grammatical mistakes and I learned new words. In that sense, I know I will not make the mistakes as frequently as I used to make them before”. (Laura: Log, 02/12/06)

Through the use of the portfolio students can not only improve their writing practices but also can become more aware of their mistakes. Grabe and Kaplan (1996) refer to this aspect in their model stating that as part of the linguistic knowledge, the awareness of differences across languages and the awareness of relative proficiency in different languages and registers become highly important for language competence. Moreover, such selfawareness allows students to understand the importance of avoiding and reducing their writing mistakes. Patricia also alludes to the fact that after participating in this project, she realized that the mistakes she used to make during her writing were because she did not focus on the tasks completely and therefore, in many occasions her compositions ended up full of minor mistakes. With regard to compositions, she makes clear her self-awareness on writing practices:

P: “My compositions are better and I am aware about the mistakes I used to make”. (Patricia: Journal 5, 11/11/06)

The students’ compositions clearly evolved positively since they learned to use the editing marks to correct their drafts. What is more, they understood the importance of self-monitoring because they were able to detect their particular writing mistakes so they could correct them. Patricia and Luisa state:

P: “I consider I have been improving by realizing I make little mistakes when writing. Now I can give more coherence to my text, I start using appropriate punctuation marks and at the same time I am strengthening my knowledge since writing is a fundamental instrument to learn a foreign language” (Patricia: Conference 2, 04/12/06).

L: “When comparing my last compositions to the ones at the beginning of the semester, I think my writing process has improved because before I didn’t care about elements such as coherence, grammar or verbs agreement. I have seen my compositions have evolved thanks to the use of possessives”. (Luisa: Log, 02/12/06)

When students understand they need a variety of elements to make their compositions better, their writing ability is strengthened as a vital skill to learn any language. Elements such as grammar, punctuation, coherence and vocabulary become highly important during any process of learning a foreign language and cannot be left aside since their use needs to be understood and applied correctly if one is to communicate ideas and thoughts appropriately. What is more important, creating a sense of selfawareness needs to be developed gradually and taken seriously during writing in EFL practices. As Hamp-Lyons and Condon depict when talking about the portfolio, “without reflection all we have is simply a pile or a large folder” (as cited in Weigle, 2002, p. 200).

Discussion

The aim of this project was to analyze how children perceived writing in English and how such perceptions evolved through the implementation of workshops based on the process approach. Moreover, this study aimed at elucidating the impact that the process approach had on the student’s writing performance and examining their understanding of the stages of such approach.

The study focused on both the evolution of the students’ perceptions during the implementation of the workshops based on the stages of the process approach, and the improvement on students’ writing skills. Thus, the results that came out from the data analysis showed that students’ perceptions changed greatly (drastically in some cases) but in a very positive way. Since students’ interests were valued from the beginning, the process had good results in view of students’ motivation was evident in each of the sessions held along the semester. The students’ prior perceptions of what writing in English meant to them changed slightly after each workshop until they began to have a positive view of writing in English.

From the beginning of the study until the end, students’ opinions regarding writing shifted. Students’ views about writing and their monitored participation created newfound sense of interest in the workshops and in writing itself. Throughout the project, the students were able to find their inner motivation to write because their creativity was triggered inspiring them to feel better about themselves during writing activities.

Another important aspect to consider was the students’ improved vocabulary building and understanding of grammatical structures. For this, the portfolio was of vital importance to helping students’ improve their compositions. As the data showed, at the beginning of the project the students felt there was a language barrier in terms of knowing the words they needed to successfully put their ideas on paper. Fortunately, the workshops were designed in such a way that the students could use appropriate vocabulary for each of the writing tasks and felt their ideas could flow better from mind to paper.

The use of the portfolio helped students realize when they made writing mistakes. This allowed self-correction since students had the opportunity to monitor their own progress. The impact of using editing marks had a positive effect on the students’ writing performance resulting in outstanding compositions based on the process of editing and re-editing each one of the drafts they had to write. Vocabulary building plus the appropriation of grammatical elements caused increased self-confidence towards writing in English. Therefore, the appropriation and assimilation of different structures through the writing practice, and the rigorous implementation of the stages of the process approach, allowed the students to write better compositions, showing improvement in each subsequent writing workshop.

In conclusion, it is necessary to highlight the importance of having students participate from the beginning of the project by choosing the topics to be addressed during the workshops. This allows them to feel important because they can participate actively and feel engaged by selecting the topics of interest. Thus, they feel motivated to write, especially during the implementation of the stages of the process approach, which demonstrated itself to be very efficient in achieving the objectives of this study. It is important to say that the students who participated in this study changed their minds regarding the opinions they had at the beginning about writing, and at the end they felt they liked to write in EFL because they were aware of their own progress. Their sense of self-confidence allowed a smooth process and the students’ improvement in writing was significant thanks to the use of a powerful tool as the portfolio.

References

Alejo R. and McGinity M. (1997). Applied languages: Theory and practice in ESP. Valencia: University of Valencia. Available: http://books.google.com.co/books?id=nzepEnaqe9sC &pg=PA216&lpg=PA216&dq=theories+on+learnin g+vocabulary&source=bl&ots=fb4trvfWl1&sig=9SiM_ ANWz0PzzisJbnqdeSGALE&hl=es&ei=dna1Sb XMLteitgfE35jqDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum =6&ct=result (Retrieved on July 5th, 2009).

Bräuer, G. (2000). Writing across languages: Vol. 1. Stamford, CT: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Brown, H. (1994). Teaching by principles. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Burns, A. (2001). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, L. & Manion, L. (1994). Research methods in education (4th ed.). London: Routledge.

Elliot, J. (1993). Action research for educational change. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Galvis, A. (2004). A collaborative writing workshop: Developing children’s writing in an EFL context. Thesis dissertation, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá.

Garner, R. & Alexander, P. (1994). Beliefs about Text and Instruction with Text. Adolescent beliefs about oral and written language. Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Harmer, J. (2004). How to teach writing. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Hayes, J. R. (1996). A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing. In C.M. Levy and S. Ransdell (eds.), The science of writing. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hayes, J. R. and Flower, L. S. (1980) Identifying the organization of writing processes. In L. W. Gregg and E. R. Steinberg (eds.), Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 31-50). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Henderson, J. & Hawthorne, R. (1995). Transformative curriculum leadership. Columbus, OH: Prentice Hall.

Hyland, K. (2002). Teaching and researching writing. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Kern, R. (2000). Literacy and language teaching. Oxford and New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lombana, C. (2002). Some issues for the teaching of writing. PROFILE Journal (3). pp. 44-51.

Mendoza, E. (2005). Current state of the teaching of process writing in EFL classes: An observational study in the last two years of secondary school. PROFILE Journal (6), pp. 23-36.

Rapaport, W. and Ehrlich, K. (1997). A computational theory of vocabulary acquisition. Buffalo, NY: University of New York. Available: http://www.cse.buffalo.edu/~rapaport/Papers/krnlp. tr.pdf (Retrieved on July 8th, 2009).

Scott, V. (1996). Rethinking foreign language writing. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle Publishers. Seliger, H. & Shohamy, E. (1989). Second language research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Walter, S. (1975). Cloze procedure: A technique for weaning advanced ESL students from excessive use of the dictionary. Menlo Park: California Association of Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. Available: http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs- 2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/33/82/f2.pdf (Retrieved on May 20th, 2009).

Weigle, S. (2002). Assessing writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.