DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n1.9471Published:

2016-05-11Issue:

Vol 18, No 1 (2016) January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesSecond language teacher education in the expanding circle: The EFL methodology course in Chile

La formación de docentes en el círculo expansivo: el curso de metodología en la enseñanza de inglés como lengua extranjera en Chile

Keywords:

el curso de metodología, contenido pedagógico, programas de formación docente, teoría y práctica (es).Keywords:

Second Language Teacher Preparation, Methodology Courses, Pedagogical Content Knowledge, Theory and Practice (en).Downloads

References

Barahona, M.A. (2014). Exploring the curriculum of second language teacher education (SLTE) in Chile: A case study. Perspectiva Educacional: Formación de Profesores, 53(2), 45-67.

Barduhn, S. & Johnson, J. (2009). Certification and professional qualifications. In A. Burns, & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 59-65). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Belcher, D. D. (2007). Seeking acceptance in an English-only research world. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16, 1-22. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2006.12.001

Berns, M. (2005). Expanding on the expanding circle: Where do WE go from here?” World Englishes, 24(1), 85-93. doi: 10.1111/j.0883-2919.2005.00389.x

Crandall, J. (2000). Language teacher education. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 20, 34-55. doi: 10.1017/S0267190500200032

Dhonau, S., McAlpine, D. C., & Shrum, J. L. (2010). What is taught in the foreign language methods course? The NECTFL Review, 66, 73-95. http://www.nectfl.org/publications-nectfl-review

Freeman, D., & Johnson, K. E. (1998). Reconceptualizing the knowledge-base of language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 32(3), 397-417. doi: 10.2307/3588114

Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative data. Social Problems, 12(4), 436-445. doi: 10.2307/798843

Graddol, D. (2003). The decline of the native speaker. In G. Anderman, & M. Rogers (Eds.) Translation today: Trends and perspectives (pp. 152-167). Clevedon, U.K.: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Grosse, C. U. (1991). The TESOL methods course. TESOL Quarterly, 25(1), 39-49.

Grosse, C. U. (1993). The foreign language methods course. The Modern Language Journal, 77(3), 303-312. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1993.tb01976.x

Grossman, P. L. (1990). The making of a teacher: Teacher knowledge & teacher education. Columbia, NY: Teachers College Press.

Hlas, A. C. & Conroy, K. (2010). Organizing principles for new language teacher educators: The methods course. The NECTFL Review, 65, 52-66. http://www.nectfl.org/publications-nectfl-review.

Huhn, C. (2012). In search of innovation: Research on effective models of foreign language teacher preparation. Foreign Language Annals, 45(S1), 163-183. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2012.01184.x

Jenkins, J. (2009). World Englishes. 2nd Ed. NYC, NY: Routledge.

Kachru, B. B. (1996). World Englishes: Agony and ecstasy. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 30(2), 135-155. doi: 10.2307/3333196

Kleinsasser, R. C. (2013). Language teachers: Research and studies in language(s) education, teaching, and learning in Teaching and Teacher Education, 1985-2012. Teacher and Teacher Education, 29, 86-96. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.08.011

Kumaravadivelu, B. (1994). The postmethod condition: (E)merging strategies for second/foreign language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 28(1), 27-48. doi: 10.2307/3587197

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). TESOL methods: Changing tracks, challenging trends. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 59-81. doi: 10.2307/40264511

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2012). Language teacher education for a global society. NYC, NY: Routledge.

Matear, A. (2008). English language learning and education policy in Chile: Can English really open doors for all? Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 28(2), 131-147. doi: 10.1080/02188790802036679

Moussu, L. & Llurda, E. (2008). Non-native English-speaking English language teachers: History and research. Language Teacher, 41(3), 315-348. doi: 10.1017/S0261444808005028

Raymond, H. C. (2002). Learning to teach foreign languages: A case of six preservice teachers. NECTFL Review, 51, 16-26. http://www.nectfl.org/publications-nectfl-review.

Richards, J. (2008). Second language teacher education today. RELC Journal, 39(2), 158-177. doi: 10.1177/0033688208092182

Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1-23. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

Schulz, R. A. (2000). Foreign language teacher development: MLJ perspectives—1916-1999. The Modern Language Journal, 84(4), 495-522. doi: 10.1111/0026-7902.00084

Schussler, D. L., Stooksberry, L. M., & Bercaw, L. A. (2010). Understanding teacher candidate dispositions: Reflecting to build self-awareness. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(4), 350-363. doi: 10.1177/0022487110371377

Tedick, D. J., & Walker, C. L. (1994). Second language teacher education: The problems that plague us. The Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 300-312. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02044.x

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237-246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748.

Vélez-Rendón, G. (2002). Second language teacher education: A review of the literature. Foreign Language Annals, 35(4), 457-467. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2002.tb01884.x

Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Watzke, J. L. (2007). Foreign language pedagogical knowledge: Toward a developmental theory of beginning teacher practices. The Modern Language Journal, 91(1), 63-82. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00510.x

Warford, M. K. (2003). The FL methods course: Where it’s been; where it’s headed. NECTFL Review, 52, 29-35. http://www.nectfl.org/publications-nectfl-review.

Wilbur, M. L. (2007). How foreign language teachers get taught: Methods of teaching the methods course. Foreign Language Annals, 40(1), 79-101. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2007.tb02855.x

Wright, T. (2010). Second language teacher education: Review of recent research on practice. Language Teaching, 43(3), 259-296.

Yates, R., & Muchisky, D. (2003). On reconceptualizing teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 37(1), 135-147. doi: 10.2307/3588468

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n1.9471

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Second language teacher education in the expanding circle: The EFL methodology course in Chile

La formación de docentes en el círculo expansivo: El curso de metodología en la enseñanza de inglés como lengua extranjera en Chile

Annjeanette Martin1

1 Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile. amartin@uandes.cl

This research project was supported through a FAI grant (Fondos de Ayuda a la Investigación), awarded to the author by Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile in 2013.

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Martin, A. (2016). Second language teacher education in the expanding circle: The EFL methodology course in Chile Colomb.Appl.Linguist.J., 18(1), pp 24-42

Received: 23-Oct-2015 / Accepted: 18-Feb-2016

Abstract

With the growth of EFL instruction worldwide, there has been increasing interest in how English teachers are prepared, yet little research has addressed these programs in foreign contexts. As part of pedagogical formation, methodology courses are considered key in developing both 'received' and 'experiential' teacher knowledge. Inspired by previous research, the current descriptive study analyzes the pedagogical content of methodology courses in EFL teacher programs in 16 Chilean universities and addresses the perceptions of methodology instructors by means of a questionnaire and an interview. Results highlight similarities and differences among programs, some considerations in designing methodology courses, and the challenges in articulating the connection between theory and practice.

Keywords: methodology courses, pedagogical content knowledge, second language teacher preparation, theory and practice

Resumen

Con el aumento en la enseñanza del inglés a nivel mundial, también se ha visto un aumento en el interés en la formación docente de los profesores de inglés. Sin embargo, ha habido escasa investigación en contextos lejos de los centros de habla inglesa. Como parte de la formación docente, los cursos de metodología se consideran claves para desarrollar los conocimientos pedagógicos 'recibidos' y 'experienciales.' Inspirado en investigaciones previas, el presente estudio descriptivo analiza el contenido pedagógico de los cursos de metodología en 16 programas de formación docente inicial para profesores de inglés en Chile e incluye las percepciones de los profesores de metodología de la especialidad a través de una encuesta y una entrevista. Los resultados abordan similitudes y diferencias entre programas, algunas consideraciones en diseñar estos cursos, y el desafío de la articulación entre teoría y práctica.

Palabras clave: el curso de metodología, contenido pedagógico, programas de formación docente, teoría y práctica

Introduction

Along with the growth of English language learners and users worldwide (Graddol, 2003; Jenkins, 2009), there has been a parallel growth in EFL teachers, 80% of whom, by some estimates, are non-native speakers who prepare to become English teachers far from English-speaking centers (Moussu & Llurda, 2008; Wright, 2010). There has also been increasing interest in research that explores the knowledge base of second language teacher education (SLTE) and how foreign language teachers are prepared to teach (Crandall, 2000; Freeman & Johnson, 1998; Huhn, 2012; Kleinsasser, 2013; Kumaravadivelu, 2012; Schulz, 2000; Vélez-Rendón, 2002; Wright, 2010; Yates & Muchisky, 2003). Much of the research in the area of English SLTE programs, however, has been conducted in what Kachru (1996) has called the inner circle, countries like Britain, Australia, the U.S., and Canada. As a consequence, most of what we think we understand about how language teachers are prepared to teach comes from research conducted in a small set of contexts that do not represent many of the instructional settings in which English is taught and learned. There has been comparatively little research that explores teacher preparation in what Kachru refers to as the expanding circle (Belcher, 2007; Berns, 2005).

The current project aims to help fill this gap by examining a key area of English SLTE programs in Chile, one of the many countries within the expanding circle where the number of English learners and teachers is growing steadily.

Context: English in Chile

There is a general sense "that English language skills […] are seen as vital if a country is to participate actively in the global economy and to have access to the information and knowledge that provide the basis for both social and economic development" (Richards, 2008). Chile's Ministry of Education has recognized the need to develop English proficiency, which is "associated with enhanced employment opportunities and social mobility" (Matear, 2008, p. 132). The Ministry of Education, therefore, has taken measures in the last decade to promote English learning: creating the "Programa Inglés Abre Puertas" ("English Opens Doors Program") in 2003, with the mission of improving English instruction in schools; lowering the grade—level in which obligatory English instruction begins in publicly funded schools, from 7th grade to 5th grade; adding an extra hour of instruction; creating and distributing an optional English curriculum and materials for 1st to 4th primary grades; and implementing a standardized English test.

This English test is administered every two years, to 11th grade students. The results from the first administration in 2010 were quite sobering: only 11% of students, almost all from the privileged, selective private school system, were able to demonstrate understanding of simple phrases and short texts (at the A2 and B1 levels of the Common European Framework). That is, 89% of the student population, the majority from the public and subsidized educational system, after seven years (over 800 hours) of English instruction, had not yet mastered the minimum level of English proficiency established by the Ministry of Education. For the test years that followed, there has been some improvement, with a passing rate of 18% in 2012 and 25% in 2014. However, 53% of students in 2014 still fell below the A1 level.

To explain such poor results, several mitigating factors have been mentioned: the number of hours of instruction and whether classes are conducted in the target language or the mother tongue, for example. Inevitably, however, English teachers—their English proficiency and their preparation in effective EFL teaching methods—are called into question.

There are several paths to become an English teacher in Chile; the most common, however, is to undertake a 4 to 5 year study program in EFL pedagogy. Although there is not a national SLTE program, university programs in Chile are generally quite fixed: students enter the program and take the same courses, in the same sequence, with the same student cohort. Programs all have a heavy English language component, to develop proficiency; pedagogical content courses in curriculum, evaluation, and methodology; and the majority of programs have introduced modifications during the last decade to incorporate school experiences in the form of observations and practicums as early as the first year, culminating during the last year in the pre-practicum semester (2 days a week) and the professional practicum (5 days a week).

Educating Foreign Language Teachers

Several decades ago, Wallace (1991) described three historically relevant models of teacher education: 1) the craft model, in which the trainee receives and imitates the trainer's expertise; 2) the applied science model, which, as the name suggests, involves the application of knowledge derived from scientific research and has been recognized, even years after Wallace's description, as the most prevalent model underlying teacher education programs (Barduhn & Johnson, 2009); and 3) the reflective model, which Wallace suggested was a compromise, involving both research and theory in the form of 'received knowledge' and 'experiential knowledge' related to practice and reflection.

There is a certain clamor by experts in the field that the reflective model, despite being recognized as "the current trend in teacher education" (Barduhn & Johnson, 2009, p. 61), has had less impact than expected and desired on SLTE programs, which, as Freeman and Johnson (1998) argue,

continue to operate under the assumption that they must provide teachers with a codified body of knowledge about language learning and language teaching […] compartmentalized in separate course offerings […] transmitted through passive instructional strategies, […] and generally disconnected from the authentic activity of teaching in actual schools and classrooms. (p. 402)

More than a decade later, Kumaravadivelu (2012) similarly argued that many SLTE programs still follow a traditional, top-down, transmission approach.

In one of the few studies that have looked at Chilean SLTE programs, Barahona (2014) explains that "programs in Chile have followed an applied linguistic tradition […but] have recently reformed their curricula integrating different types of knowledge" (p. 46). Barahona summarizes three models of SLTE (similar to those described by Wallace, 1991) and suggests that current SLTE programs in Chile are hybrid models, containing elements of all three models. Barahona's interesting case-study analyzes one such program; however, there have been no broader analyses of SLTE programs in Chile that address how teacher knowledge is conceptualized more generally.

Methodology Courses in SLTE Programs

There are many aspects of SLTE programs that need to be illuminated through research to better understand how teacher knowledge is conceptualized. Of particular interest in the present study are methodology courses, a fundamental component of initial teacher development. As part of initial SLTE, teachers take at least one methodology course specifically related to the discipline, though it is increasingly the case that there are two or three such courses (Huhn, 2012). The importance of these courses cannot be overstated. It is through the methodology course that pedagogical content knowledge related to being a foreign language teacher is transmitted or constructed (Dhonau, McAlpine, & Shrum, 2010; Grosse, 1991, 1993; Hlas & Conroy, 2010; Warford, 2003; Wilbur, 2007). This knowledge consists of "a blending of content and pedagogy into an understanding of how particular topics, problems, or issues are organized, represented, and adapted to the diverse interests and abilities of learners, and presented in instruction" (Raymond, 2002, p. 16). The methodology courses are where pre-service teachers "may acquire their most significant understandings of language teaching" (Raymond, 2002, p. 16), yet there has been little research related to the role of these courses in language teacher education.

Grosse (1991, 1993) reviewed 157 methods course syllabi from 144 U.S. universities offering programs for foreign language teaching certification. Grosse described five aspects of the syllabi: the course goals, or what students should learn; instructional materials, what readings or texts do students read; course content, the major topics that were covered and how much time was spent on each topic; course requirements, what kind of work were students expected to do; and evaluation, how the required assignments were weighted for grading. According to Grosse (1993), analyzing these aspects of the syllabi can "help establish a conceptual framework for the course" and shed light on the elements that "form a significant part of the knowledge base of a course" (p. 304).

Although Grosse highlighted several areas for improvement, such as fewer traditional exams, more journal use, and better relationships between schools and universities, her general assessment was positive: that there were many strengths and similarities in the syllabi she reviewed. Not all researchers have come to such seemingly optimistic conclusions, however, about the state of methodology courses in SLTE programs. More recently, Wilbur (2007) similarly analyzed 31 methods course syllabi and administered a questionnaire to course instructors and found that there was an unsettling amount of variety in the contents covered across these courses, in the backgrounds of the instructors who teach these courses, and in the ways in which teacher candidates are evaluated. She suggests that the most effective course of action would be "a national movement to identify the best practices of methods instruction and to identify certain instructors and their courses as a model for others" (Wilbur, 2007, p. 96).

Even in contexts like the U.S., where these studies have been conducted, teacher educators claim that there is a need for more research that would shed light on what is currently taught in teacher preparation programs (Glisan, 2006; Vélez-Rendón, 2002). Yet, there has been even less research in EFL contexts that address SLTE curriculums or conceptualizations of teacher knowledge. Chile's SLTE programs had been operating without any unifying criteria, with very little information regarding common parameters among programs (Programa Inglés Abre Puertas, December, 2012). In particular, as Díaz, Martínez, Roa, and Sanhueza (2010) claim, there is very little information in Chile regarding the teaching models and methods that future teachers are taught in their SLTE programs.

In January 2014 the first standards for English teacher preparation programs were published. According to Glisan (2006) standards operate as "clearly defined expectations […] concerning what teacher candidates should know and be able to do as beginning teachers" (p. 11). An analysis of the new standards themselves is beyond the scope of this paper; however, it is relevant to note that with the new standards, many programs will have to undergo evaluation and restructuring so that their graduates can meet these expectations.

Because there is so little information about what is taught in SLTE programs in Chile, the current project intends to make a contribution, in this regard, by examining what is taught in methodology courses and what this reflects about how English teaching is conceptualized. The main aim of the current study is to shed light on where Chile is now regarding the methodological preparation of teachers in order to understand what modifications programs might make to better prepare future teachers.

Research Questions

What are the contents of methodology courses in English teacher preparation programs in Chilean Universities?

• What are the course objectives?

• What pedagogical content is covered?

• How are students evaluated?

• What bibliography is used?

What are the perceptions of methodology course instructors regarding methodology courses?

Methodology

Following the models of Grosse (1991, 1993) and Wilbur (2007), this study presents a descriptive analysis of 46 methodology courses from 16 Chilean university EFL teacher preparation programs as well as a digital questionnaire and interview data from methodology course instructors.

Between November 2013 and January 2014, the 33 principal Chilean universities that offer 4 to 5 year undergraduate, pre-service English teacher preparation programs were contacted and invited to participate in the study. Program Directors from 16 universities (49%) agreed to participate; because of multiple campuses, 30 of the 49 programs (61%) are represented. Program directors were sent a consent form describing the aims of the study, after which they sent the most current versions of the syllabi for their programs' methodology courses.

Directors identified the methodology course instructors in their programs; 42 instructors were then contacted and invited to participate in an online questionnaire followed by an interview. There were 18 methodology instructors (43%) who completed the online questionnaire during December 2013 and January 2014. For reasons of space, only certain sections of the digital questionnaire will be analyzed here.

A semi-structured interview guide was constructed, also loosely based on the previous studies mentioned. Nine instructors from six universities agreed to participate; interviews were conducted in person when possible, or by Skype, during January 2014. Consent was sought for audio-recording the interviews. Interviews were conducted in Spanish or English according to the preferences of the participants. All interviews were transcribed by the researcher and excerpts were translated from Spanish to English when necessary. See Appendix B for the interview guide.

Data Analysis Methods

The first part of the study consists of an archival analysis of 46 methods course syllabi using a general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006). In addition to a general description of the courses, the analysis of the syllabi examined four principal elements, following Grosse's (1991, 1993) approach: 1) course objectives; 2) pedagogical course content; 3) instructional materials; and 4) evaluation requirements. Grosse had a fifth element: the weight of each evaluation requirement, which was not possible to determine in most of the syllabi analyzed here. Each section of the syllabus was separated into items, which were then analyzed following a system of open coding (Miles & Huberman, 1994), considering thematic categories established in previous research mentioned, and creating new categories to accommodate emerging data. Categories and item pertinence were checked with a peer evaluator until full consensus was reached. These categories will be discussed below for each section analyzed of the syllabi.

The data from the online questionnaire were tabulated quantitatively using descriptive statistics. There were several open-ended questions on the online questionnaire, in addition to the transcribed interview data, which were analyzed qualitatively, using open coding to identify recurring themes.

Digital Questionnaire and Interviews

Instructor background. The following data were collected from the digital questionnaire. Of the 18 methodology instructors who responded to the invitation to participate, 12 (67%) were female and 6 (33%) were male. Regarding educational background, 13 (72%) had studied English language pedagogy as undergraduates; of the remaining five, four studied English literature and linguistics, and one studied international relations. All 18 had master's degrees and some had additional degree certificates, most in related fields such as linguistics, applied linguistics, or TESOL, and others related to education in general.

When asked about their EFL teaching experience in K-12, only two instructors had not had teaching experience either at the elementary or secondary level; 15 had taught an average of 6.9 years at the elementary level and 14 had taught an average of 6.7 years at the secondary level; many had taught at both levels. There was an average of 10.1 years (range: 1-37) teaching in a university level EFL teacher preparation program and an average of 4.9 years (range: 1-20) teaching methodology courses.

Interviews

Nine participants volunteered to be interviewed: seven female and two male methodology instructors. The themes related to methodology courses, the content, how the classes are organized and some of the challenges instructors face and possible improvements they identify will be presented here to complement data from the digital questionnaire.

Study Limitations

Although 60% of Chilean EFL teacher preparation programs are included in this study, it is only a sample of the programs offered. One of the important limitations of this study is that it largely involves document analysis; because of time and access, what happens inside the classroom—the manner and the depth with which content is taught or by which students are evaluated—could not be addressed in this phase. However, the online questionnaires and interviews do offer additional insights, supporting the findings from the analysis of the syllabi.

Findings and Discussion

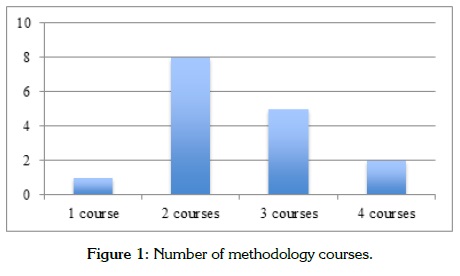

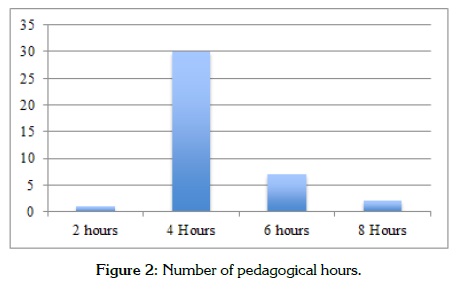

The 16 participating universities have an average of 2.5 methodology courses in their programs: 1 (6%) university only has 1 methodology course; 8 (50%) have 2 courses; 5 (31%) have 3 courses; and 2 (13%) universities have 4 methodology courses (see Figure 1). Figure 1 displays how many methodology courses these programs offer. There is an average of 4.5 face-to-face hours of class time per week during a 16-18 week semester: 1 course, called a workshop, meets 2 hours a week; 30 courses meet for 4 hours a week; 7 courses have 6 hours of class time; and 2 courses offer 8 hours of class time (see Figure 2). Figure 2 displays the number of class hours for each methodology course.

Instructor Perceptions: Time

Of the 18 instructors that participated in the digital questionnaire, ten (55.6%) indicated that they believe the number of face-to-face hours of class they have per week/semester is sufficient to cover the material and give students the learning experiences they need; eight instructors (44.4%) believe that the class-time is not sufficient. Eleven of the participants provided explanations in the comments section, only one of which indicated that there was enough time dedicated to methodology. One participant specified that although there were enough hours, that content should be better organized. Nine participants claimed that the time allotted is insufficient: "there should be more hours of class-time a week, or better yet, another semester." Seven of these nine cited the need for more connection between theory and practice "[time] is insufficient to cover both the theoretical and practical contents in enough depth" and "more time is needed so that students can internalize knowledge and put it into practice" (Respondents 4 and 6, digital survey).

Some of the instructors interviewed, particularly those working in programs with only two methodology courses, also addressed the issue of time. Five of the instructors indicated that one additional semester or one or two more hours per week would be beneficial for more practical aspects, such as helping students plan. One instructor, in a program with two methodology courses near the end of the program, suggested that "there should be methodology throughout the whole program, beginning in 2nd semester, we can't expect that in the last year, one teacher can cover all that they have to know" (interviewee 2). Another also indicated that methodology needed more hours and that "there should be as much emphasis on methodology as there is on language (interviewee 4). Another instructor indicated that ideally there could be more emphasis on methodology (beyond the four courses in her program), but that it would mean adding methodology in the first two years of the program, where "students do not have the maturity or the level of English" (interviewee 5).

Class Size

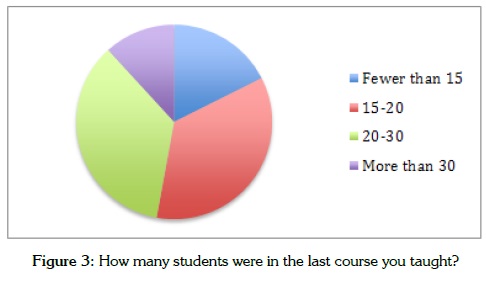

Related to the question of whether there is sufficient time dedicated to methodology is the issue of class-size. The number of students and the number of face-to-face class hours are important considerations when planning experiential learning opportunities, like microteaching. When asked about the number of students in their last methodology course on the questionnaire, three instructors (17.6%) indicated that they had fewer than 15 students in their last course; six (35.3%) had between 15-20; six (35.3%) had between 20-30 and two (11.8%) had more than 30 students. One limitation with this question is that it depends largely on the size and location of the university and the size of the cohort. Figure 3 illustrates the number of students in the last course taught.

Class size was also a concern expressed by some of the interviewees. Interviewee 3 indicated that 15 students would be ideal; with 30 students there is not enough time to dedicate to more practical tasks, like microteachings. Interviewee 4 explained that she had even added 2 hours of her own time to divide the class into smaller groups for more personalized attention for the microteachings.

Course Objectives

All syllabi have a section dedicated to positing the learning objectives or goals for the course. Goals or objectives define and describe the learning outcomes in terms of pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students are expected to have developed or achieved by the end of the course. 463 objectives were identified and categorized by theme. Because all of the universities in the present study have more than one methodology course, often with repeated objectives, the objectives are presented based on the percentage of the 16 universities that included them in any of their methodology course syllabi.

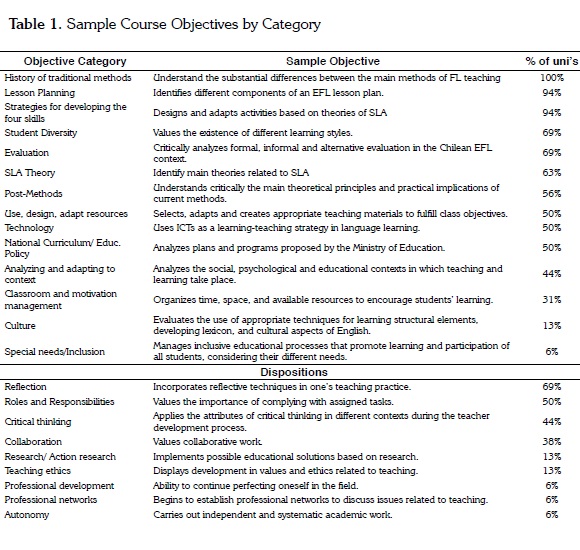

The objectives related to pedagogical knowledge that appeared most frequently in over half of the universities' methodology course syllabi were: Traditional methods (100%), lesson planning (94%), strategies for developing the four skills (94%), understanding learner diversity (69%), evaluation (69%), theories of SLA (63%), post-methods principles (56%), national curriculum (50%), material design (50%), and technology (50%). The objectives that appeared less frequently, in fewer than half of the universities, were: considering context (44%), activity design (38%), classroom management (31%), creating an appropriate climate for learning (31%), culture (13%), and working with special needs students (6%).

Regarding the attitudes and dispositions that students are expected to develop in the methodology course, most universities (81%) included at least one objective related to dispositions: reflection (69%), teacher roles and responsibilities (50%), critical thinking (44%), and collaborative work (38%) were the dispositions most frequently mentioned. Less frequently mentioned dispositions included: teacher as investigator (13%), teaching ethics (13%), autonomy (6%), continuing professional development (6%), and professional networks (6%). Table 1 presents representative objectives for each category.

Instructor Perceptions of Objectives

The methodology course goals expressed by the nine interviewed instructors fell into three main categories. The most commonly mentioned goals (five interviewees) were related to understanding and working within particular contexts and being familiar with the characteristics of the students they will encounter, and understanding how to inspire students in those contexts to use English. Four of the instructors also expressed goals more technical in nature: understanding how students learn languages and becoming familiar with techniques, strategies, and the main methodologies for teaching a language. The last category of goals, mentioned by two instructors, was related to how to help students reflect on what they are doing and why in order to make better decisions.

In examining the course objectives, explicit in the syllabi, and the goals expressed by the interviewed instructors, methodology courses seem to be much more technical, transmitting the "nuts and bolts" of teaching: methods, planning, evaluation, and teaching the four skills. Although the goals of working within a particular context, which requires a certain level of reflective analysis, were among the most frequently mentioned by the instructors, this area is less represented in the syllabi. In both the syllabi and the interviews, the areas related to dispositions: reflection, critical thinking, developing autonomy, and promoting professional development are much less present.

Pedagogical Content

Pedagogical course content, defined as the topics or themes covered in the syllabi, mirrored the course objectives to some extent. All syllabi have a section dedicated to describing the pedagogical content that is covered in the course; 638 content descriptors were identified and categorized by theme, similar, though not identical, to the themes identified under course objectives. Pedagogical content descriptors are presented based on the percentage of universities that included the content areas in any of their methodology course syllabi. It was impossible to determine from the syllabi how much time was spent on each content area; therefore, this information is not presented.

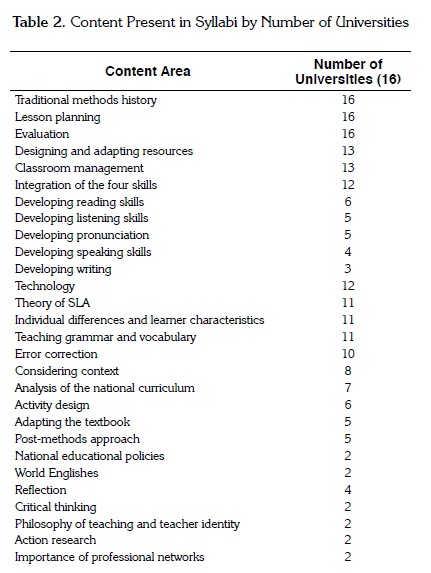

There were several content areas covered by all 16 universities: Traditional methods, Lesson planning, and Evaluation. Other pedagogical content areas also mentioned frequently include: designing and adapting resources (81%), classroom management (81%), integration of the four skills (75%), technology (75%), theory of SLA (69%), individual differences and learner characteristics (69%), teaching grammar and vocabulary (69%), error correction (63%), and considering context (50%). Pedagogical content that appeared less frequently included: analysis of the national curriculum (44%), activity design (38%), adapting the textbook (31%), post-methods approach (31%), national educational policies (13%), and World Englishes (13%). Content area categories identified in the 46 syllabi are presented in Table 2 with the number of universities that included each content category.

In addition to the content area of integrating the four skills and teaching grammar that were addressed in 75% of the university methodology course syllabi, all syllabi listed varying categories of skill development: developing reading skills (38%), developing listening skills (31%), developing pronunciation (31%), developing speaking skills (25%), and developing writing (19%). Some syllabi separated skills by receptive and productive (44% of universities).

There was some mention of dispositions in the list of content covered in the methodology courses, by percentage of universities: reflection (31%), critical thinking (13%), philosophy of teaching and teacher identity (13%), action research (13%), and the importance of professional networks (13%). Dispositions, as might be expected, were more present in the course objectives than in the description of pedagogical content covered in the methodology courses.

What is interesting to note perhaps, in what has been called a post-methods era (Kumaravadivelu, 1994, 2006), is the continuing emphasis, in methodology courses, on traditional methods (grammar-translation, audiolingual, etc.); in fact, while all programs included traditional methods, fewer than half of the universities even included the notion of post-methods in their syllabi.

It may also be important to mention that in about half of the universities, particularly those with fewer methodology courses, content is somewhat limited to the technical aspects of language teaching: methods, planning, teaching language skills, and evaluating and there is much less attention paid to content that implies more reflective analysis, for example, what it means to work within a particular context. An understanding of context has gained increasing importance in models of teacher knowledge and includes expectations, rules, and guidelines and constraints that are imposed by the educational system at national, district, and school levels (Grossman, 1990; Shulman, 1987). This understanding of context would certainly include considering the national curriculum in lesson planning and working with the obligatory textbooks. These content areas are missing in the syllabi of many of the university programs.

Instructor Perceptions of Content

When asked in the digital questionnaire what content areas were not included in methodology courses, the 18 instructors identified the following areas: teaching to young learners, teaching learners with special needs, teaching culture, using technology, and classroom management. The areas of young learners, special needs students, and culture are notoriously absent from both the objectives and the content found in the syllabi. The perceptions of the instructors confirm this. Technology and classroom management are present in the syllabi, but several of the instructors explain that the depth of coverage or how certain areas are covered is problematic. This may be the case with these areas. In the interviews, several of the participants discussed how they have tried to include content areas such as young learners, because teachers, even if they are prepared to teach at the secondary level, are often asked to teach at the primary level. One participant expressed interest in including monitoring student learning, and another in including classroom management in her course, "which is essential and almost disregarded in Chile" (interviewee 1), but both lacked time.

The area that instructors most grappled with in the interviews is teaching traditional methods. Instructors often do not have the freedom to make substantial changes to syllabi without authorization and many seem to struggle with how much time to dedicate to this topic. However, in the interviews, all of the participants addressed ways that they try to make their courses more practical: one instructor requested authorization to make the course less theoretical, another covered the methods, but tried to dedicate less time to them during the semester. They also make conscious efforts to make covering methods less theoretical: one instructor explained that when teaching methodological techniques, her goal is to lead students to "understand them with their hands, not just their head" (interviewee 6) and another participant expressed her approach this way:

More than what is taught, the how is very important. If it is too theoretical, it is not as useful. Students have a right to see all of the content possible, but if you are going to cover a history of methods, but you just read about it and then present what was read in class, that doesn't give them anything other than what they can get by themselves from the reading. They need to see it in action; they need to try it out (interviewee 1).

Student Evaluation

Each course syllabus briefly explains student evaluations: the tasks and assignments that students are expected to complete in order to pass the course. From the 46 course syllabi, 245 items were categorized by type of evaluation. For most universities, the weight of each evaluation task was not available; therefore, this information is not presented.

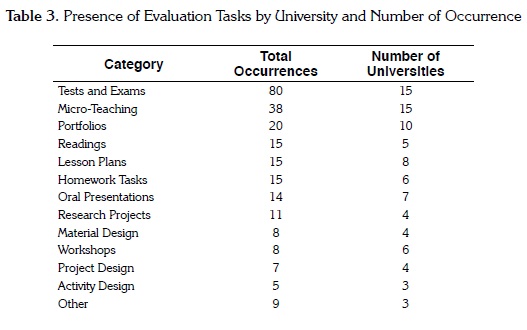

The most frequently mentioned evaluation tasks were tests and exams, with 80 occurrences; 93% (n=15) of the universities included at least one theoretical test in their methodology courses. The second most frequently listed evaluation task, mentioned 38 times, was microteachings: 93% (n=15) of the universities asked students to teach sample lessons in front of the class. Portfolios were listed 20 times, in 63% (n=10) of the universities. All of the other evaluation tasks were mentioned in the methodology courses in less than half of the universities, and with far fewer occurrences: readings, listed 15 times in 5 (31%) universities; lesson plans, listed 15 times in 8 (50%) universities; oral presentations, mentioned 14 times in 7 (44%) universities; research projects, listed 11 times in 4 (25%) universities; material design tasks, mentioned 8 times in 4 (25%) universities; activity design tasks, mentioned 5 times in 3 (19%) universities. Table 3 presents the number of universities, out of the 16 participating institutions, that include each type of evaluation in any of the methodology courses—because most universities offer more than one methodology course, this seemed to make more sense than looking at the number of course syllabi that included the evaluation tasks. Table 3 also presents the total number of occurrences of each type of evaluation task.

Tests and exams are, by far, the most frequently included evaluation task, comprising a third (33%) of all evaluation tasks. It is distantly followed by more practical kinds of tasks, microteachings, comprising 16% of all evaluation tasks and portfolios, comprising 8% of evaluations. All of the other evaluation tasks (readings, presentations, projects material and activity design, etc.) are mentioned infrequently, 3-6%, in few universities (n= 3-7).

Instructor Perceptions of Evaluations

The responses of the interviewed instructors regarding evaluations suggest that they have made both major and minor modifications in terms of evaluation, usually in an attempt to make evaluations more practical. In many cases, instructors are not free to change the types of evaluations, such as tests. Several instructors claimed that they have tried to make exams that involve more reflection, using case studies, rather than testing conceptual knowledge. One participant described how she had created a more realistic planning template, of one page, rather than the 4-5 page lesson plan students were asked to complete for the practicum classes. She believed that students should get "practice doing what they will do in real life" (interviewee 1). Instructors did bemoan that they often cannot include more practical experiences, such as microteachings, because of time limitations or the number of students they have.

Of special note was one methodology instructor, also one of the practicum supervisors, who had studied reflective teaching one summer and had pushed to authorize changes in the evaluative scheme. She introduced reflective journals designed "at least on paper" to guide students towards higher levels of reflection. She also started implementing video analysis, self-evaluation, and stimulated recall interviews at higher levels and worked to involve the cooperating teachers in this process so that "students can find different voices, different feedback" (interviewee 8).

Course Bibliography

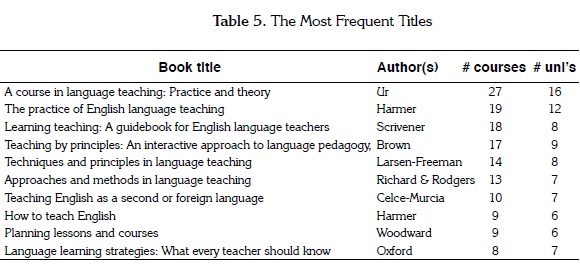

Course bibliography refers to books, articles, official documents, web pages, etc., that students read or consult for class. As Grosse (1991) indicates, reading materials "either reflect the knowledge base for the subject or establish it" (p. 38). The course bibliography in the Chilean syllabi is divided into primary readings and supplementary readings. Between the two, there were 466 resources listed in the 46 syllabi, with an average of 10.13 (range: 2-21) resources listed in each syllabus. There were 200 different titles listed, the majority of which are books. Only six courses at four universities list web pages as resources and only five universities included Ministry of Education documents, such as the National Curriculum and the English plans and programs by grade level. One university included two academic articles in their methodology course bibliography, and only one university listed a journal as a reference, the English Teaching Forum, a publication distributed by the U.S. State Department.

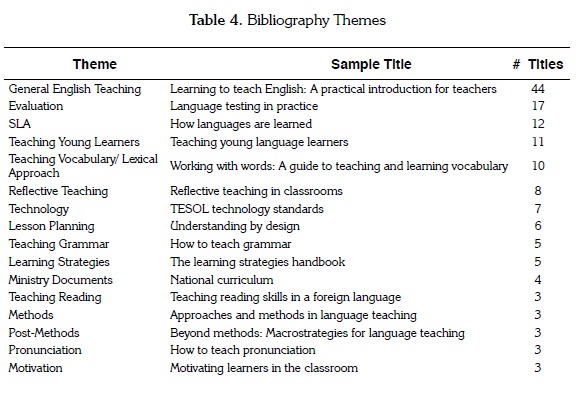

There is some similarity between the universities regarding frequent themes in the readings assigned. Nearly 25% (44) of the titles are what could be called general English teaching handbooks: principles, techniques, language pedagogy, teaching and learning EFL, and CELTA, TEFL, and TKT training books. Four of these books deal with teaching English in different settings with different types of learners and two deal with the challenges of global English. There are 17 titles related to assessment and evaluation; 12 related to SLA; 11 for teaching young learners; 8 for reflective teaching; 7 related to technology; 6 related to lesson planning; 5 related to teaching grammar; 3 related to methods and approaches and 3 related to post-methods. Table 4 presents the most frequent themes represented in the bibliography, examples of each and the number of titles.

Although the number of titles is overwhelming, there is still some conformity. The most frequently listed book is Ur's A course in language teaching, used by all 16 universities, followed by Harmer's The practice of English language teaching, used by 12 universities. Table 5 presents the 10 most frequently mentioned titles and the number of courses and universities that have listed them.

Instructor Perceptions of Readings

There were few comments related to readings during the interviews. One participant described making changes in the readings, moving from online webpages to articles that she felt were more academic in nature. Another participant described the challenge of getting students to read and to understand what they have read to apply that knowledge to what they were doing in class.

Theory and Practice

One of the themes that arose in the interviews with many of the instructors related to most of the points discussed above, objectives, content, evaluation, and bibliography is the concern with connecting theory and practice. Some of the instructors, as discussed above, described how they work within their particular constraints to make content more applicable, to make evaluations more practical and more reflexive, and to choose readings that would be useful.

The connection between theory and practice in teacher preparation is essential, particularly in methodology courses. One challenge identified by the interviewed participants was the connection between the methodology courses and the series of observation and practicum courses. Five of the nine interview participants indicated that there was little to no communication between these two areas: "There is no connection between what students see in methodology and what their practicum supervisor asks them to do" (interviewee 1). In the cases of participants who indicated that there was a connection between methodology courses and the practicums it was either because they were both the methodology instructor and the practicum supervisor or in the cases of a few universities, there had been a concrete attempt to articulate the two areas, either through coordination and communication or in the case of one university by overhauling the practicum line and bringing some of the pedagogical content typically taught in methodology into the practicum sessions.

Conclusions and Implications for SLTE Programs

There is a general sense from the participating instructors that methodological courses, given their relevance in English teacher preparation, should have a much more important role in SLTE programs. As the programs are now, there is much more weight given to linguistic competence and knowing about the language. SLTE programs in Chile struggle to fit proficiency development courses, pedagogical knowledge courses, and practical school experiences into the study plans while accommodating other university course work and general education courses; however, with one or two methodology courses, instructors can barely cover a portion of the theoretical course content and find they don't have enough time to give students more of the practical, hands-on experiences they need.

Because methodology courses are crucial in bringing together all areas of teacher knowledge, there are certainly strong implications here for future program modifications. Making more space for such a key element of teacher preparation, either by adding more methodology courses, giving existing courses more weight by increasing credits and class hours, or by incorporating more methodological knowledge into other areas, such as the practicums, is essential. The instructors who were satisfied with the number of semesters and number of class hours worked in programs with three or four methodology courses or had created a clear articulation with the practicum courses.

The conceptualization of SLTE preparation that seems to emerge from the methodology course analysis in the current study, most closely resembles the applied science model. This is consistent with Barduhn and Johnson's (2009) assertion that this model is still quite pervasive despite attempts to move the field towards the reflective model. What we see overwhelmingly here in the goals and content of the methodology courses, and in the way students are evaluated, is the transmission of "received knowledge" related to teaching: a history of methods and language learning theories, lesson planning, strategies for teaching the four skills, and evaluation.

Returning to Wallace's original description of reflective practice, which Wright (2010) describes as a "fairly radical departure in curriculum design" (p. 265), what seems to remain elusive in many of Chile's SLTE programs is the 'experiential knowledge' that is developed by enacting and reflecting on the 'received knowledge' with particular learners within a particular context. The findings in the present study also seem to suggest that there is a missing link in taking the received content knowledge in methodology courses and finding the spaces to give future teachers sufficient opportunity to enact and reflect on it through means of experiential knowledge. The methodology instructors' recognition that there is often no connection at all between what happens in the methodology courses and what students are doing in their practicums suggests that the different elements of teacher preparation still lack articulation. This connection between theory and practice clearly needs to be addressed.

Another concern that arises with the current findings is whether university programs are responding to the needs of schools and EFL learners and teachers in Chile. Teachers are required to follow the national curriculum and often use a state-financed textbook, yet very few of the methodology courses analyzed here give students the tools they need to plan effectively with these obligations in mind. Special methodologies for young learners, strategies for dealing with special needs students, and classroom management have been identified as pervasive needs, yet those areas, as explained by the instructors and as evidenced by the syllabi, remain largely unaddressed.

Although the term "reflection" is visible in many syllabi, only a few programs show evidence that they are moving toward a more reflective model. This can be evidenced in the findings here in the lack of attention given to developing future teachers' understanding of the contexts they will be working in and the students they will be serving; in cultivating a more critical sense of how to choose methods and strategies appropriate for those contexts and students; or in fostering professional development and networks.

More evidence that many of Chile's SLTE programs have still not adapted a reflective model can be observed in how future teachers are evaluated: traditional exams are the most cited form of evaluation in a course where practical applications should be much more prevalent. As mentioned earlier, many of the instructors lamented not being able to include more tasks such as microteachings due to the lack of freedom, lack of time, and the number of students. However, some of the needed changes here (smaller sections, modified syllabi, evaluation scheme) will have to come from the program heads, as the instructors can only work within the confines given.

There is some evidence here, at least in the syllabi examined in this study and in the voices of the participating instructors, that a few Chilean SLTE programs are, as Barahona (2014) indicates, hybrid models, starting to incorporate elements of a reflective practitioner model, articulating received knowledge and experiential knowledge. However, there seem to be quite a few programs, at least among those analyzed here, that have not yet made that leap and are still quite centered in the applied science tradition.

Future Research

With the Grosse (1991, 1993) study, the Wilbur (2007) study, conducted several years after release of the ACTFL/NCATE standards in 2002 (now the ACTFL/CAEP standards), as teacher educators were attempting to align their programs to reflect the competencies that had been agreed upon, and the Dhonau, McAlpine, and Shrum (2010) study, we can see the evolution of methodology courses in response to the accepted standards in the field. The current study serves as a baseline for looking at this evolution in Chile, and allows for future research that would analyze the modifications that might occur now that Chile has its own SLTE standards.

The pedagogical knowledge imparted in the methodology courses is only part of the SLTE preparation. There are many areas of Chile's teacher preparation that have not been studied. Although methodology is a key piece, it would also be worthwhile to understand what experiences are most useful during the observation and practicum courses, how linguistic and cultural competence is best developed, and what kinds of support novice teachers need as they make the transition from pre-service to in-service teacher. This would provide a bigger picture of how EFL teachers are prepared to teach in Chile.

References

Barahona, M.A. (2014). Exploring the curriculum of second language teacher education (SLTE) in Chile: A case study. Perspectiva Educacional: Formación de Profesores, 53(2), 45-67.

Barduhn, S., & Johnson, J. (2009). Certification and professional qualifications. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 59-65). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Belcher, D. D. (2007). Seeking acceptance in an English-only research world. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16, 1-22. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2006.12.001.

Berns, M. (2005). Expanding on the expanding circle: Where do WE go from here? World Englishes, 24(1), 85-93. doi: 10.1111/j.0883-2919.2005.00389.x.

Crandall, J. (2000). Language teacher education. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 20, 34-55. doi: 10.1017/S0267190500200032.

Dhonau, S., McAlpine, D. C., & Shrum, J. L. (2010). What is taught in the foreign language methods course? The NECTFL Review, 66, 73-95. http://www.nectfl.org/publications-nectfl-review.

Díaz, C., Martínez, P., Roa, I., & Sanhueza, M. G. (2010). Una fotografía de las cogniciones de un grupo de docentes de inglés de secundaria acerca de la enseñanza y aprendizaje del idioma en establecimientos educacionales públicos de Chile. Folios, 31, 69-80. http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/revista?codigo=16415.

Freeman, D., & Johnson, K. E. (1998). Reconceptualizing the knowledge-base of language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 32(3), 397-417. doi: 10.2307/3588114.

Glisan, E. W. (2006). Today's pre-service foreign language teachers: New expectations, new realities for teacher preparation programs. In Responding to a new vision for teacher development. 2006 Report of the Central States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (pp. 11-40). http://www.csctfl.org/committees/communication/csctfl-report.html.

Graddol, D. (2003). The decline of the native speaker. In G. Anderman, & M. Rogers (Eds.), Translation today: Trends and perspectives (pp. 152-167). Clevedon, U.K.: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Grosse, C. U. (1991). The TESOL methods course. TESOL Quarterly, 25(1), 39-49.

Grosse, C. U. (1993). The foreign language methods course. The Modern Language Journal, 77(3), 303-312. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1993.tb01976.x.

Grossman, P. L. (1990). The making of a teacher: Teacher knowledge & teacher education. Columbia, NY: Teachers College Press.

Hlas, A. C., & Conroy, K. (2010). Organizing principles for new language teacher educators: The methods course. The NECTFL Review, 65, 52-66. http://www.nectfl.org/publications-nectfl-review.

Huhn, C. (2012). In search of innovation: Research on effective models of foreign language teacher preparation. Foreign Language Annals, 45(S1), 163-183. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2012.01184.x.

Jenkins, J. (2009). World Englishes (2nd ed). NYC, NY: Routledge.

Kachru, B. B. (1996). World Englishes: Agony and ecstasy. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 30(2), 135-155. doi: 10.2307/3333196.

Kleinsasser, R. C. (2013). Language teachers: Research and studies in language(s) education, teaching, and learning in Teaching and Teacher Education, 1985-2012. Teacher and Teacher Education, 29, 86-96. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.08.011.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (1994). The postmethod condition: (E)merging strategies for second/foreign language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 28(1), 27-48. doi: 10.2307/3587197.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). TESOL methods: Changing tracks, challenging trends. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 59-81. doi: 10.2307/40264511.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2012). Language teacher education for a global society. NYC, NY: Routledge.

Matear, A. (2008). English language learning and education policy in Chile: Can English really open doors for all? Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 28(2), 131-147. doi: 10.1080/02188790802036679.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Moussu, L., & Llurda, E. (2008). Non-native English-speaking English language teachers: History and research. Language Teacher, 41(3), 315-348. doi: 10.1017/S0261444808005028 .

Programa inglés abre puertas. (2012, December). La formación de docentes de inglés en Chile: El desafío de la calidad y la pertinencia. Informe del Segundo seminario. Retrieved from http://piap.cl/seminarios/archivos/2do-seminario/informe-2do-seminario.pdf.

Raymond, H. C. (2002). Learning to teach foreign languages: A case of six preservice teachers. NECTFL Review, 51, 16-26. http://www.nectfl.org/publications-nectfl-review.

Richards, J. (2008). Second language teacher education today. RELC Journal, 39(2), 158-177. doi: 10.1177/0033688208092182.

Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1-23. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411.

Schulz, R. A. (2000). Foreign language teacher development: MLJ perspectives—1916-1999. The Modern Language Journal, 84(4), 495-522. doi: 10.1111/0026-7902.00084.

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237-246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748.

Vélez-Rendón, G. (2002). Second language teacher education: A review of the literature. Foreign Language Annals, 35(4), 457-467. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2002.tb01884.x.

Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Warford, M. K. (2003). The FL methods course: Where it's been; where it's headed. NECTFL Review, 52, 29-35. http://www.nectfl.org/publications-nectfl-review.

Wilbur, M. L. (2007). How foreign language teachers get taught: Methods of teaching the methods course. Foreign Language Annals, 40(1), 79-101. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2007.tb02855.x.

Wright, T. (2010). Second language teacher education: Review of recent research on practice. Language Teaching, 43(3), 259-296.

Yates, R., & Muchisky, D. (2003). On reconceptualizing teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 37(1), 135-147. doi: 10.2307/3588468.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.