DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.14329Published:

2022-04-22Issue:

Vol. 24 No. 1 (2022): January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesControversial Issues and their Impact on the Construction and Reshaping of EFL Learners' Habitus

Temas polémicos y su impacto en la construcción y reestructuración del habitus de estudiantes de EFL

Keywords:

Palabras clave: habitus, temas polémicos, pedagogía crítica, aprendizaje crítico de EFL, estudio de caso (es).Keywords:

critical EFL pedagogy, podcasts, habitus, grounded theory, case study (en).Downloads

References

Ang, I. (2003). Together‐in‐difference: Beyond diaspora, into hybridity. Asian Studies Review, 27(2), 141-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357820308713372 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10357820308713372

Barnes, D. M. (1996). An analysis of the Grounded theory method and the concept of culture. Qualitative Health Research, 6(3), 429-441. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239600600309 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239600600309

Bhabha, H. K. (1996). Culture's in-between. In S. Hall, & P. du Gay (Eds.), Questions of cultural identity (pp. 53-60). SAGE. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446221907.n4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446221907.n4

Bhabha, H. K. (2012). The location of culture. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203820551 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203820551

Bodovski, K. (2014). Adolescents' emerging habitus: the role of early parental expectations and practices. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 35(3), 389-412. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2013.776932 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2013.776932

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503621749 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503621749

Bourdieu, P. (2014). The habitus and the space of life-styles. In J. J. Gieseking, W. Mangold, C. Katz, S. Low, & S. Saegert (Eds.), The people, place, and space reader (pp. 139-144). Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (2002). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago Press.

Buckingham, D. (2003). Media education and the end of the critical consumer. Harvard Educational Review, 73(3), 309-327. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.73.3.c149w3g81t381p67 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.73.3.c149w3g81t381p67

Buhr, A. (2016). Mediating the Lions of Postmodernism: An EFL Field Application of Vygotsky, Bourdieu, and Derrida. Journal of Education in Black Sea Region, 2(1), 79-92. https://doi.org/10.31578/jebs.v2i1.32 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31578/jebs.v2i1.32

Costa, C., & M. Murphy (Eds.) (2015). Bourdieu, Habitus and Social Research: The Art of Application. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137496928 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137496928

Dooley, K., Exley, B., & Poulus, D. (2016). Research on critical EFL literacies: An illustrative analysis of some college-level programs in Taiwan. English Teaching & Learning [英語教學], 40(4), 39-64. https://doi.org/10.6330/ETL.2016.40.4.02

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford University Press.

Fajardo-Mora, N. R. (2013). Pre-service Teachers' Construction of Meaning: An Interpretive Qualitative Study. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(1), 43-57. https://doi.org/10.14483/issn.2248-7085 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2013.1.a03

Fife, W. (2005). Doing fieldwork: ethnographic methods for research in developing countries and beyond. Palgrave Macmillan.

Freedman, J. E., & Honkasilta, J. M. (2017). Dictating the boundaries of ab/normality: a critical discourse analysis of the diagnostic criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and hyperkinetic disorder. Disability & Society, 32(4), 565-588. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1296819 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1296819

Forbes, J., & Lingard, B. (2015). Assured optimism in a Scottish girls' school: Habitus and the (re) production of global privilege. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 36(1), 116-136. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.967839 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.967839

Gaddis, S. M. (2013). The influence of habitus in the relationship between cultural capital and academic achievement. Social science research, 42(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.08.002 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.08.002

Gao, Y., Wang, X., & Zhou, Y. (2014). EFL motivation development in an increasingly globalized local context: A longitudinal study of Chinese undergraduates. Applied Linguistics Review, 5(1), 73-97. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2014-0004 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2014-0004

Ghaemi, H., & Abdullahi, H. (2016). EFL Teacher's Affective Constructs and Their Sense of Responsibility. Research in English Language Pedagogy, 7, 64-72. https://www.noormags.ir/view/en/articlepage/1189917/efl-teacher-s-affective-constructs-and-their-sense-of-responsibility

Glaser, B. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis. Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. (2016). Open coding descriptions. Grounded Theory Review, 15(2), 108-110. http://groundedtheoryreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Open-coding-descriptions-Dec2016.pdf

Glaser, B. & Holton, J. (2004). Remodeling grounded theory. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(2), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-5.2.607

Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine Press. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-196807000-00014 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-196807000-00014

Grimes M. D., & Morris, J. M. (1997). Caught in the Middle: Contradictions in the Lives of Sociologists from Working-class Backgrounds. Praeger.

Hammersley, M. (1989). The dilemma of qualitative method. Routledge.

Hernández-Castro, O., & Samacá-Bohórquez, Y. (2006). A study of EFL students' interpretations of cultural aspects in foreign language learning. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 38-52. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.171 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.171

Ho, S. T. K. (2009). Addressing culture in EFL classrooms: The challenge of shifting from a traditional to an intercultural stance. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 6(1), 63-76. https://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/v6n12009/ho.pdf

Hooks, B. (2010). Teaching critical thinking: Practical wisdom. Routledge.

Jee, Y. (2016). Critical perspectives of world Englishes on EFL teachers' identity and employment in Korea: an autoethnography. Multicultural Education Review, 8(4), 240-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2016.1237705 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2016.1237705

Kim, J. (2002). Teaching culture in the English as a foreign language classroom. The Korea TESOL Journal, 5(1), 27-40.

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford University Press.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Problematizing cultural stereotypes in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 37(4), 709-719. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588219 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3588219

Kubota, R., & Lin, A. (2009). Race, culture, and identities in second language education: exploring critically engaged practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203876657 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203876657

Lee, E. M., & Kramer, R. (2013). Out with the Old, in with the New? Habitus and Social Mobility at Selective Colleges. Sociology of Education, 86(1), 18-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040712445519 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040712445519

Lehmann, W. (2007). "I just didn't feel like I fit in": The role of habitus in university drop-out decisions. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 37(2), 89-110. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v37i2.542 DOI: https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v37i2.542

Lehmann, W. (2012). Working-class students, habitus, and the development of student roles: A Canadian Case Study. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 334, 527-546. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.668834 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.668834

Lehmann, W. (2014). Habitus transformation and hidden injuries: Successful working-class university students. Sociology of Education, 87(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040713498777 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040713498777

Martin, J. & Nakayama, T. (2018). Intercultural communication in context. McGraw-Hill.

Melville, E. C. (2015). An exploration of the role of EFL educators in a globalized world. IJAEDU-International E-Journal of Advances in Education, 1(3), 218-223. https://doi.org/10.17583/qre.2016.1797 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18768/ijaedu.05741

Nash, R. (1999). Bourdieu, 'habitus,' and educational research: Is it all worth the candle? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20(2), 175-187. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425699995399 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01425699995399

Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Sage.

Purba, H. (2011). The Importance of including culture in EFL teaching. Journal of English Teaching, 1(1), 44-56. https://doi.org/10.33541/jet.v1i1.51 DOI: https://doi.org/10.33541/jet.v1i1.51

Reay, D. (2001). Finding or Losing Yourself? Working-class Relationships to Education. Journal of Education Policy, 16(4), 333-346. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930110054335 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930110054335

Reay, D. (2015). Habitus and the psychosocial: Bourdieu with feelings. Cambridge Journal of Education, 45(1), 9-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2014.990420 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2014.990420

Rowlands, J., & Gale, T. (2016). Shaping and being shaped: Extending the relationship between habitus and practice. In J. Lynch, J. Rowlands, & T. Gale (Eds.), Practice theory and education: diffractive readings in professional practice (pp. 91-107). Routledge.

Shin, H. (2014). Social class, habitus, and language learning: The case of Korean early study-abroad students. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 13(2), 99-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2014.901821 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2014.901821

Song, J. (2016). (Il)Legitimate Language Skills and Membership: English Teachers' Perspectives on Early (English) Study Abroad Returnees in EFL Classrooms. TESOL Journal, 7(1), 203-226. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.203 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.203

Su, Y. C. (2008). Promoting cross‐cultural awareness and understanding: incorporating ethnographic interviews in college EFL classes in Taiwan. Educational Studies, 34(4), 377-398. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690802257150 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690802257150

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage

Tursini, U. (2014). Exploring Changes in Teachers' Pedagogic Habitus: Case Studies of English Language Teacher Self-Evaluation as a Mediational Activity [Doctoral dissertation, The University of New South Wales]. http://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/fapi/datastream/unsworks:12797/SOURCE02?view=true

Wacquant, L. (2016). A concise genealogy and anatomy of habitus. The Sociological Review, 64(1), 64-72. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12356 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12356

Koenig, S. (2013). Dr. Gilmore and Mr. Hyde. This American Life [Radio podcast]. WBEZ. https://www.thisamericanlife.org/492/dr-gilmer-and-mr-hyde

Wells, K. (1995). The strategy of grounded theory: possibilities and problems. Social Work Research, 19(1), 33-37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42659916

Wodak, R., & M. Meyer. (2009). Critical Discourse Analysis: History, Agenda, Theory, and Methodology. In R. Wodak, & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods for Critical Discourse Analysis (pp. 1-33). Sage.

Zhang, Y., & Wildemuth, B. M. (2017). Unstructured interviews. In B. Wildermuth (Ed.), Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science (pp. 222-231). Unlimited libraries.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 14 de enero de 2019; Aceptado: 3 de diciembre de 2021

Abstract

The following study aims to explore Bourdieu’s notion of habitus and its shaping and re-shaping through exposure to authentic oral input in an EFL (English as a foreign language) advanced course at a language institute in Chile. This work used podcasts as an EFL teaching strategy, where learners were expected to confront their cultural dispositions. For this study, mental illness was employed as a controversial topic. We used a grounded theory approach and multi-case study design, where we implemented three unstructured interviews in each case along the teaching process. The research generated categories that emerged from the coding process. The results reveal that the EFL learning process and the inclusion of controversial topics can become a subversive form of defying culturally dominant dispositions and enhancing the learners’ probabilities of re-shaping their habitus while learning a foreign language.

Keywords

habitus, controversial topics, critical pedagogy, critical EFL learning, case study.Resumen

El siguiente estudio pretende explorar la noción del habitus de Bordieu y su estructuración y reestructuración a través de la exposición a material oral auténtico en un curso avanzado de EFL (enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera, por sus siglas en inglés) en un instituto de idiomas de Chile. Este trabajo utilizó podcasts como estrategia de enseñanza de EFL, donde se esperaba que los estudiantes confrontaran sus disposiciones culturales. Para este estudio se emplearon las enfermedades mentales como tema controversial. Utilizamos un enfoque de muestreo teórico y un diseño de estudio de casos múltiples, en el cual aplicamos tres entrevistas no estructuradas a lo largo del proceso de enseñanza para cada caso. La investigación generó categorías que emergieron del proceso de codificación. Los resultados revelan que el proceso de aprendizaje de EFL y la inclusión de temas polémicos puede convertirse en una forma subversiva de desafiar disposiciones culturalmente dominantes y aumentar las probabilidades de que los estudiantes reestructuren su habitus mientras aprenden una lengua extranjera.

Palabras clave

habitus, temas polémicos, pedagogía crítica, aprendizaje crítico de EFL, estudio de caso.Introduction

Culture is a key component in EFL teaching ( Kramsch, 1993 ). Although most content in the classrooms may focus on the culture and identity of different societies ( Kim, 2002 ), it is interesting to observe how students’ understanding of their own culture strongly affects both positively and negatively the way in which they receive and grasp foreign cultures and identities ( Kim, 2002. Kumaravadivelu, 2003. Hernández-Castro and Samacá-Bohórquez, 2006 ). This leads to questions regarding the potential methods for increasing students’ awareness of their cultural dispositions and their construction. These cultural dispositions have been labeled by critical sociology as habitus, a concept coined by Bourdieu (1990) .

A clear definition of it has been quite elusive. For this research, the one provided by Nash (1999) will be used, and even this definition once again reflects its elusive nature by beginning with nonconcrete language: “Bourdieu’s habitus may be understood as a system of schemes of perception and discrimination embodied as dispositions reflecting the entire history of the group and acquired through the formative experiences of childhood” (p. 177). In other words, habitus is a set of cultural dispositions that reflects our cultural views, prejudices, and stereotypes. Moreover, this concept entails a reciprocal relationship between our activities in everyday life and our cultural dispositions. Throughout our daily activities, cultural norms that we have construed through previous experiences continually influence us, and, at the same time, we influence the construction of those norms through the performance of our activities.

This issue gains enormous pertinence in the EFL classroom since “without the study of culture, foreign language instruction is inaccurate and incomplete” (Peck, as cited in Purba, 2011 , p. 45). Lacking the capability to think critically and possibly re-shape their boundaries of habitus may be difficult for learners. This difficulty may arise because learners may not be capable of comprehending social identities in the ESL/EFL classroom without tainting with the typical stereotypes, predispositions, and misconceptions that run rampant in our society ( Kubota and Lin, 2009 ). Considering habitus as part of our daily language teaching implies a pedagogical challenge as well. It is necessary to understand that habitus, or cultural dispositions, are part of our students’ identities. Some of these prejudices and stereotypes may help or hinder our students’ learning process regarding the cultural perception of learning a foreign language. At the same time, including habitus as an articulator of our lessons may help students modify their prejudices and stereotypes in the long run ( Rowlands and Gale, 2016 ).

Additionally, the world is saturated with information in both positive and negative regards; positive, since we have access to the web, television, and social networks in order to interact and observe so much more than ever before; and negative, if we only pursue flat material that only confirms our predispositions.

Hooks (2010) asserts that “the hours spent gazing at the television set seems to stop creative processes […] to repress and contain everyone within the limits of the status quo” (p. 60). In this sense, our dispositions, which are culturally elaborated, are maintained through the continuous cultural habits of Western society. Therefore, in its attempt to gain insight into methods to address EFL learners’ habitus, this study can provide a richer and more complete view of the language and culture that students learn of others and themselves. It explores the notion of Bourdieu’s habitus,its implications regarding dispositions to mental illness, and how the image of the mentally disabled is configured from a cultural perspective and re-shaped through learning a foreign language, specifically through controversial issues in listening comprehension tasks.

Theoretical framework

Towards a definition of habitus

In order to fully grasp the concept of habitus, the following section will briefly outline the environment in which the sociological concept was developed and the guiding objectives that pushed Bourdieu (1990) to attempt to fill a void that he saw in critical sociology, his field of study. In addition, the main features of habitus will be established, as well as other conceptual tools from Bourdieu that work hand in hand with habitus.

Firstly, it is necessary to acknowledge that the concept may be regarded as an old philosopheme that originated in Aristotlean thought and medieval scholastics. Bourdieu reintroduced it as a dispositional theory of action and agency and correlated it with his critique towards domination ( Wacquant, 2016 ). As Wacquant (2016) asserts, the concept is based on the triple historicization of the agent (habitus), the world (social space and fields), and the categories and methods of the social analyst (reflexivity).

According to Bourdieu, habitus can be defined as “a system of dispositions, that is of permanent manners of being, seeing, acting and thinking, or a system of long-lasting (rather than permanent) schemes or schemata or structures of perception, conception, and action” ( Bourdieu, 2002, p. 27). It can be concisely referred to as a set of practices that outflow from objectivist and subjectivist perspectives:

I wanted initially to account for practice in its humblest forms –rituals, matrimonial choices, the mundane economic conduct of everyday life, etc.– by escaping both the objectivism of action understood as a mechanical reaction “without an agent” and the subjectivism which portrays action as the deliberate pursuit of a conscious intention… (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992, p. 121)

For Bourdieu, the unnecessary dichotomy between objectivism and subjectivism caused both paradigms to fall short of fully explaining the choices, dispositions, and perspectives that human beings carry out in their everyday life. According to Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992) , interpreting the actions of agents within society as “an instantaneous reaction to immediate stimuli” creates an oversimplification that does not account for the “whole history of these persons and of their relationship[s]” (p. 124). In other words, how person A responds to person B is not as simple as it may seem on the surface, but rather a complex pattern of routines that have been carried out with such frequency in the past that they restrict the creative quality of the responses that are produced.

Critical sociology and habitus

Bourdieu’s understanding of critical sociology originated as “an attempt to understand and represent practice within the constraints of the social world, in that it seeks to bridge the difference between the subjective and objective social worlds” (Jenkins, 2002, as cited in Costa and Murphy, 2015 , p. 5). Bourdieu’s critical sociology, with its more complex understanding of human action, has not only provided a “set of thinking tools” but has additionally contributed to the field of research by allowing “for a rich meaning-making approach in which both external systems and human experiences […] are interdependently considered and analyzed” ( Costa and Murphy, 2015, p. 6 ). In addition, it has fostered “the empowerment of both the researcher and the researched through a conceptual framework that aims to reconcile theory with practice through the method” ( Costa and Murphy, 2015, p. 6 ).

According to Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992) , one of the most fundamental aspects of critical sociology resides in an ‘obsession with reflexivity’, which attempts to “make visible the ‘unthought of’ categories, perceptions, theories, and structures that underpin any pre-reflexive grasp of the social world” (Deer, 2008, as cited in in Costa and Murphy, 2015 , p. 5-6). Due to how these frameworks develop, we rarely become aware of unconsciousness and its influence on our daily actions and reactions. As developed further below, making these visible and becoming aware of the interplay between habitus, a highly effective system of predispositions, and practice, the specific decisions we as active agents carry out, are both fundamental to executing the objectives of this research. Even though habitus has a potentially problematic reputation, many researchers see this as not only positive but necessary to truly “[…] overcome the dichotomy between structure and agency whilst acknowledging the external and historical factors that condition, restrict and/or promote change” ( Costa and Murphy, 2015, p. 3 ).

Types of habitus

Within habitus, it is vital to highlight its two subcategories, generic habitus, and secondary habitus. While generic habitus tends to ensure its constancy and its defense against change, secondary habitus incorporates what is acquired later and in more specialized contexts, such as the school or the workplace –which is more likely to encourage changes in individuals’ practices ( Bourdieu, 1990 ). The importance of these two interwoven types of habitus that are always at play is how these dispositions liberate and honestly give agency to us human beings within the societal class and context in which we were born. According to Fox (1985, as cited in Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992 ), specific experiences can re-shape habitus, given that it is “always in the making” (p. 132). The key to fostering these interstices is “only [possible] if the latter snatches it from the contingency of the accidental and constitutes it as a problem by applying to it the very principles of its solution” ( Bourdieu, 1990, p. 55), which is where the vital connection with critical sociology’s ‘obsession with reflexivity’ comes into play.

Habitus: a trained pattern of cultural dispositions

As mentioned above, dispositions represent the building blocks of habitus (in both subcategories). They are internalized and transformed into a set of practices on the one hand and perceptions on the other ( Bourdieu, 2014 ). According to Bourdieu (1990) , dispositions are “durably inculcated by the possibilities and impossibilities, freedoms and necessities, opportunities and prohibitions inscribed in the objective conditions” (p. 54). As Costa and Murphy (2015) assert, cultural dispositions “develop in practice to justify individuals’ perspectives, values, actions, and social positions” (p. 4). Within this process, “one becomes more empowered to address and potentially correct actions and thoughts that would otherwise go unnoticed” (p. 4). Therefore, the system of dispositions that form one’s habitus and represents an “assimilated past without a clear consciousness” should be understood as “more than nature; it can also be nurtured” ( Costa and Murphy, 2015, p. 7 ). In this sense, habitus behaves as a mediating construction that allows the dialogue between the individual and society. In other words, there is an internalization of externality and an externalization of internality ( Wacquant, 2016 ). Therefore, the interaction between these sociosymbolic structures of society can become a fixed set of trained or patterned dispositions that, at the same time, guide creative responses to the constraints and solicitations of extant milieu ( Wacquant, 2016 ).

Considering this notion of habitus as trained patterns of dispositions that guide practices, it partakes strong links with the psychosocial and affective aspects of conceiving and understanding inequalities in society ( Reay, 2015 ). Likewise, the practicality of our action comes from dispositions and can be re-shaped if these dispositions are explicit, so it might be possible to broaden the scope of the dispositions that constitute one’s habitus through questioning and interacting. For this very reason, habitus establishes itself as a handy conceptual tool to comprehend action, stereotypes, and prejudices, in addition to raising students’ awareness. Similarly, it is possible that learners’ habitus might be modified through direct teaching strategies and tasks that challenge cultural dispositions.

The transformational potential of habitus in the EFL/ESL classroom

Some studies have been carried out to explore the transformational potential of habitus in school and university students ( Bodovski, 2014. Forbes and Lingard, 2015. Gaddis, 2013. Grimes and Morris, 1997. Lee and Kramer, 2013. Lehmann, 2007, 2012, 2014. Reay, 2001. Rowlands and Gale, 2016 ). Their conclusions tend to agglutinate concerning the capacity of adaptation and reshaping of habitus, where a mediating role between academic achievement and cultural capital develops. Furthermore, the roles of primary pedagogic work, the family, the community, and secondary pedagogic work at the institutional level are acknowledged as shapers and re-shapers of habitus ( Rowlands and Gale, 2016 ).

In the case of recent EFL research and habitus considerations, there are various domains of inquiry, such as language learning dispositions ( Gao et al., 2014. Shin, 2014 ), critical EFL education ( Buhr, 2016. Dooley et al., 2016 ), and EFL teacher identity and teacher education ( Fajardo-Mora, 2013. Ghaemi and Abdullahi, 2016. Jee, 2016. Song, 2016. Tursini, 2014 ). These studies validate concerns on the topics of critical pedagogy for the EFL teaching and learning process, where dispositions and cultural identities are treated as part of pedagogical interaction. Furthermore, the focus on teacher education shows the need to include a critical perspective on socio-symbolic factors underpinning language learning and EFL teacher education so as to elucidate domination processes and practices. For instance, Tursini (2014) studied teaching practices as a set of culturally learned practices or habitus. The author concluded that critical pedagogical reflection and self-assessment of one’s teaching helps accommodate teacher identity, create teacher development opportunities, and transform what Tursini calls a pedagogic habitus. In addition, Tursini (2014) highlights that different teaching experiences can bring cultural predispositions to light, and therefore, different forms of power and control. However, in her research, the author noted that teachers could modify their pedagogic habitus “from dominance to being more accommodating of the students’ needs” ( Tursini, 2014, p. 224).

In conclusion, the comprehension of habitus and its potential to re-shape practices and prejudices not only helps to unveil culturally dominant dispositions towards language learning, but also to restructure psychosocial constructions towards learners’ prejudices and stereotypes. Moreover, the reciprocal nature of habitus as an internalization of externality and externalization of internality offers the opportunity to utilize teaching materials to activate mechanisms of dispositions where language learning mediates between language and symbolic productions. Therefore, the pedagogical implications for the EFL/ESL classroom are enormous, since language learners may be able to increase the awareness of their cultural dispositions and modify them while learning a foreign or second language. In other words, incorporating language teaching contents and materials that challenge the students’ cultural dispositions will contribute to the learning of the sociocultural dimensions of language. At the same time, learners will use their cultural dispositions to interpret the contents, materials, and sociocultural context of language use. Their interpretation of the topics will place their cultural dispositions at play by engaging them in negotiating cultural practices. Consequently, the effects of the inclusion of controversial topics in any language task might not only influence students’ language learning process, but it may also help them become more culturally open and sensitive to other kinds of experiences in their everyday life.

Methods

Participants

Two individuals conforming to an advanced English class were selected at convenience; they were selected from language classes to which the researchers had access. The two participants involved in this study were students in an English as a foreign language course in a language institute in Chile. They were in their early thirties and midforties. Their names are kept confidential. For this study, one individual will be referred to as Sara and the other as Ashley. Two 60-minute classes were taught every week for four months. These classes used podcasts as a listening task whose main topic focused on mental illness. Using the levels of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), these two students would be classified as C1.

Research question

To what extent is the implementation of controversial issues in listening comprehension tasks such as authentic podcasts able to influence and re-shape EFL students’ habitus?

Study aims

This study aims to account for the ongoing agent process of constructing EFL learners’ habitus while explicitly addressing mental health stereotypes. In this sense, the study seeks to identify the degree to which the introduction of controversial topics in listening comprehension tasks affects the stereotypes, assumptions, and disposition (habitus) regarding mental issues and their re-shaping.

Study design

This study is of a longitudinal descriptive qualitative nature, where the students’ construction of habitus is reviewed under a multi-case study design. Its longitudinal nature lies in the monitoring of students’ dispositions through the interviews carried out within the research process. As Dornyei (2007) states, longitudinal studies compare two or more data collection moments, regardless of the temporality of the process. This study employed three interview instances along the research process. Therefore, this work of research may be considered longitudinal.

The objective of this work is to describe habitus and its re-shaping. Thus, the study adopted a grounded theory stance in order to give a complete account of the participants’ conceptualizations around their cultural dispositions towards mental illness. Grounded theory is based on the constant comparison between theory and empirical data, recurring to the researcher’s sensitivity to determine categories resulting from such comparison ( Barnes, 1996. Glaser, 1992. Glaser and Strauss, 1967. Hammersley, 1989. Wells, 1995 ). However, one of the most prominent characteristics of the method lies in its emphasis on the analysis of empirical data over theory ( Glaser and Strauss, 1967 ).

The researchers chose the mental illness issue due to its controversial status in our society. Mental disorders and the notion of normality have been extensively argued from sociocultural perspectives (Conrad, 1975; Davis, 2009; Freedman and Honkasilta, 2017 ). The implications and tensions of what is regarded as normal navigate between the dominant and rational, objective, and nonideological scientific rhetoric ( Wodak and Meyer, 2009 ) and the recognition of mental disorders as legitimate in discursive practices within social, cultural, and institutional contexts (Davis, 2009). Therefore, the notion of (ab)normality is construed not only within medical debates, but also outside the borders of science, both socially and culturally. For this study, we, the researchers, decided to incorporate this tension in order to challenge the dominant cultural dispositions. In other words, this study is about challenging students to confront their prejudices and stereotypes. In that sense, the study does not aim to generalize its findings but to uncover specific dispositions.

Data collection procedures

The data collection process was implemented according to the following steps:

Step 1: The students listened to an excerpt from This American Life’s Dr. Gilmore and Mr. Hyde (lasting 3-5 minutes). This specific audio is one of many that would appropriately fit the requirements of this activity in the following regards: i) authentic material, ii) problematic with regard to habitus formation and stereotypes of mental health, and iii) contextually relevant to the students’ world.

With over 2,1 million weekly listeners, This American Life is one of the most listened podcasts in the United States, and it provides an exciting and engaging insight into American culture.

Step 2: To ensure comprehension, students and one of the researchers participated in an open floor conversation regarding content clarification. Although not the primary aim or objective of this activity, listening comprehension serves as both a means and source of ideas for the application of this case study.

Step 3: After clarifying their understanding of the content, the students participated in three unstructured interviews with the moderator/ researcher. As Punch (1998) asserts, unstructured interviews are a way to understand social reality without a priori categorizations; the researcher comes to the interview with no predefined theoretical framework, hypotheses, or questions ( Zhang and Wildemuth, 2017 ). However, this does not imply less preparation for the data collection process. According to Fife (2005) , the researcher must mind the study’s purpose, aims, and scope in order to maintain an adequate interaction with the participants’ narration. Following Fife (2005) , the researchers did not look for preconceived questions and correct answers or tried to coax the students to agree or disagree with one perspective regarding others but rather raised student’s awareness of how they have come to construct their answers. Buckingham (2003) emphasizes that “prescriptive teaching strategies that try to fix meanings and impose ‘correct thoughts’ can do more harm than good when confronting tasks focused on culture and habitus” (p. 317).

Step 4: As mentioned earlier, transcripts were made of the recordings gathered from the interviews. MAXQDA® Plus 12 (12.2.1) was used as software for transcription and analysis. Next, the transcripts were coded using research-generated categories (RGC) to light the different codes. We employed the coding procedures suggested by Glaser and Holton (2004) –open coding was utilized as a first asset. This procedure entails line-by-line coding in order to “verify and saturate categories, [it] minimizes missing an important category and ensures the grounding of categories in the data beyond impressionism” ( Glaser and Holton, 2004, p. 13 ). Afterward, theoretical sampling was determined in a process that “collects, codes and analyses” ( Glaser and Holton, 2004, p. 13 ) jointly in an iteration continuum. Such iteration allows the researcher to reach a core variable, a theoretical concept from empirical data, which functions as the foundation for selective coding.

Consequently, selective coding was employed to determine what variables were related to the core variable ( Glaser and Holton, 2004 ), or, in other words, what codes were related to a central code that could be acknowledged as a plausible theory. Therefore, the analytical categories that we obtained are the outcome of an iterative process that included data collection, coding, and analysis as part of the same research cycle. To be precise, we have included eleven categories as the result of this study.

Length of the research: This study was carried out over four months.

Implementation of authentic audios:

Throughout the research, This American Life’s Dr. Gilmore and Mr. Hyde has proved to fulfill the requirements of being both an authentic and engaging text. Most importantly, it created cultural interstices in which the students’ understanding of their habitus and stereotypes was challenged and rethought, which is highly in line with Bourdieu’s ‘obsession with reflexivity’. In other words, the students were able to identify their perceptions and dispositions towards a controversial topic that pushed them out of their cultural ‘comfort zone’. In addition, through interactions with both participants, various instances occurred in which they explicitly shared their satisfaction and motivation due to the type of audios they were interacting with.

Data analysis techniques

With the recordings of the interviews mentioned above, transcripts were produced. Using the MAXQDA® Plus 12 (12.2.1) software, the transcripts were coded using RGC so as to identify and delimit the distinctive analytical categories denoting the different cultural-interstices in which students actively grappled with the construction of their habitus and stereotypes of mental health. These categories emerged from the participants’ discourses through in vivo coding. As mentioned above, grounded theory is about a constant iteration to obtain theory. However, our paradigmatic stance lies upon a critical analysis, whose analytical tool is the concept of habitus within Bourdieu’s theorizations (1990, 2014) . As stated by Glaser and Holton (2004) , grounded theory analysis is “far different from the typical QDA [qualitative data analysis] preplanned, sequential approach to data collection and management. Imposing the QDA approach on GT [grounded theory] would block it from the start” (p. 14). Under the inquiry of grounded theory, the results were analyzed in order to explore to what degree the podcast, as part of a listening task, interacted with the students’ ongoing construction of habitus.

Ethical considerations

The study employed an ethical protocol that considered the rights of the participants as a central element. Additionally, this protocol considered elements such as the nature of the study, its aims, and its value. Furthermore, the study obtained written informed consent from each participant to guarantee that both of them could evaluate the risks and benefits of participating in the research process. Furthermore, the study sustained confidentiality and anonymity throughout the research process by keeping data under safety precautions and replacing the participants’ actual names.

Findings and results

The following section is divided into two parts: 1) implementation of authentic audio and 2) qualitative results of classroom transcripts. These are further broken down into two different subcategories: a) general analysis and b) comparative analysis.

Qualitative results of transcripts

The transcribed classroom discussions provided dense and rich qualitative data, which allowed a clearer understanding of the impact of the use of controversial topics concerning the participants’ recognition and construction of habitus. As mentioned before, MAXQDA® Plus 12 (12.2.1) was used to code the transcripts, using RGCs to bring to light the different cultural interstices in which students actively grappled with the construction of their habitus and stereotypes regarding mental health. Eight different categories were generated after analyzing the transcripts in accordance with the procedures proposed by Glaser and Holton (2004) which imply open and selective coding. According to Glaser (2016) , “open coding allows the researcher to see the direction in which to take his research so he can become selective and focused conceptually on a particular social problem” (p. 108). This involved allowing all possible forms of coding, such as in vivo coding in a constant reflexive revision to reach the core category ( Glaser, 2016 ). The eight RGCs were the following: 1) empathy, 2) self-censorship, 3) challenging, 4) intercultural-connection, 5) labeling, 6) self-identification, 7) cognitive dissonance, and 8) hesitancy. In addition, two subcategories were created under self-identification, which allowed for a more precise coding of its positive and negative instances. Brief descriptions of what each category represents are presented below:

1. Empathy: it represents a moment where a speaker attempts to validate an action of a character in the audio as correct, just due to

the circumstances, even though it may not be politically correct.

2. Self-censorship: it represents a moment where a speaker states one opinion and then restates or negates what he or she had previously stated. This typically occurred when the speaker said something that they thought was not politically correct.

3. Challenging: it represents a moment when a speaker explicitly states that a person in the audio is not telling the truth.

4. Intercultural connection: it represents a moment when a speaker explicitly verbalizes a connection between a person in the audio and their culture or society.

5. Labeling: it represents a moment where a speaker describes how a particular person or group of people should act according to the speaker.

6. Self-identification: it represents a moment where a speaker explicitly verbalizes a connection between a person in the audio and himself or herself. This category was divided into positive ones, in which the participants felt similar to the groups or individuals in the program, and negative ones, in which the participants felt they were different.

7. Cognitive dissonance: it represents a moment where a speaker expresses a difficulty between his or her beliefs and understandings and what is occurring in the audio, i.e., the information does not fit well into their cognitive framework.

8. Hesitancy: it represents a moment where a speaker verbalizes that they are uncomfortable about labeling or categorizing a person, typically due to what they describe as a lack of information or a desire to have more information before answering the question.

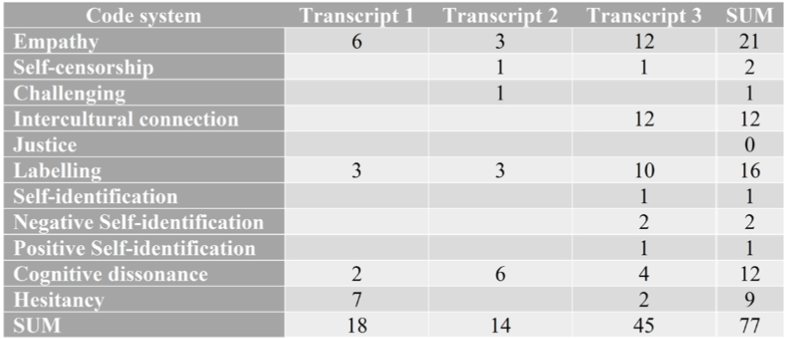

General analysis

When looking at a general analysis of the occurrences of the eight different RGCs, the first and most important observation is that both participants voiced multiple occurrences of different categories due to their reaction and interaction with the authentic oral texts. In the three different interviews, the total number of comments or instances coded within one of the categories was 77 (or 18, 14, and 45 on each of the three occasions, respectively).

In addition, the distribution of the occurrences showed an almost identical frequency in the first and second interviews. A speaking turn (or part of a speaking turn) was coded every 10,55 and 10,28 turns, respectively. The last lesson showed almost double, with a speaking turn (or part of a speaking turn) being categorized every 5,77 turns.

The RGC occurrences throughout the process can be summarized as follows:

As observed in Table 1 , the first interviews tend to poorly agglutinate categories related to empathy, labeling, cognitive dissonance, andhesitancy, which may be interpreted as a scarce connection with the controversial issue and a self-centered vision. However, the last interview tends to concentrate the codes around empathy, intercultural connection, and labeling with a higher frequency than the first one. This analysis is merely illustrative, so that the reader can observe where the codes tended to appear.

Comparative analysis

Regarding the differences observed between the two participants, the two most significant points that will be discussed are the numerical comparison of occurrences and the very different manners in which both self-identified. As mentioned earlier, this exercise shed some light on the informants’ participation and how the codes were distributed along with the transcripts. Nevertheless, the focus of this study is to give an account of the discourse produced by the participants, i.e., our interest is in the configuration of habitusin discourse.

On the other hand, it is quite interesting to analyze the specific types of comments coded for each participant. For example, Sara’s occurrence of empathy was more frequent than Ashley, as well as the fact that her comments were never coded as self-censorship, while Ashley had two occurrences:

Another background is the fact that his father abused him when he was a child, so, I mean, there’s a […] history in which you can predict the end of this. He’s a kind of victim. (Sara, Interview III)

I’m not so bad like him […] but I think he was an intelligent man and I think you have the opportunity in which you feel that there’s something wrong and maybe our responsibility is not how to be sano (sic), ok, or well. (Ashley, Interview III)

We’re different. I hope! (Ashley, Interview III)

Table 1: Coding progression

In the examples above, it is possible to notice how Sara can negotiate her cultural dispositions towards child victimization and its consequences. In other words, she can empathize with the character due to her cultural construction of childhood as a generation that needs protection. Despite her initial differences with the character, she can recognize other sociocultural practices that allow her to modify her dispositions and promote change ( Costa and Murphy, 2015 ). In addition, only Sara’s statements were coded as positive self-identification, whereas, in the category of self-identification, Ashley only registered negatively:

I’m not so bad like him. (Ashley, Interview III) I have these kinds of problems in my family. We have a history of mental illness, so now I feel very… not different with Doctor Vincent. We are similar. (Sara, Interview III)

The more personal comments from Sara, such as those where she explicitly mentions her own family’s issues with mental illnesses, can lead to the conclusion that the material was quite intimate and therefore may have influenced her to process more and comment less superficially. We also inferred that her cultural dispositions might have contributed to conceptualizing the issue differently than Ashley, due to what Wacquant (2016) refers to as a trained pattern of dispositions. However, in the case of Ashley, we can observe how she keeps herself distant and unwilling to dialogue to remark her identity difference. As mentioned before, habitus also reflects the cultural dispositions that in turn reflect how inequality operates at the micro and macro-social levels ( Reay, 2015 ). Therefore, we interpret how mental health is socially perceived and, consequently, how the image of the mentally ill is reconfigured and has a strong connection with recognizing social inequalities and privilege.

When looking at the variation of the eight different RGCs, empathy had the highest amount (21), followed by labeling (16) and intercultural connection and cognitive dissonance (both with 12). Concerning empathy and labeling, the number of instances where both participants demonstrated these types of comments increased as the lessons progressed. On the other hand, cognitive dissonance seemed to remain somewhat the same throughout all the lessons, whereas intercultural connection, which seems to provide evidence of cultural-interstices and cultural empathy, only appears in the last interview:

I think that here in Chile we have a very big problems (sic) because we have high consumption of anti-depressants, but society still looks at them like mental illness was contagious. For example, most parents tell their children that they have to avoid epileptic kids and I think that this is a very sad situation because they always think that a mental illness is a crazy (sic) with a knife and things like that, but there’s a wide range of disease and we have to accept them like just another illness. (Sara, Interview III)

As we can observe, Sara can recognize the social inequalities and dispositions towards a controversial topic after prolonged exposure to the issue. Somehow, Sara resists the image of a mentally ill outcast by reducing the prejudice against the topic. As she says, “we have to accept them like just another illness” (Ashley, Interview III). Therefore, she reconfigures the dispositions she is expected to perform. However, Ashley did not show any intercultural connection towards underrepresented cultural identities. We believe that habitus can be deeply rooted in people’s comprehension of the world. Thus, the inclusion of controversial topics is not sufficient per se. We think it is necessary to incorporate teaching strategies that could defy the students’ cultural dispositions in the long run.

Discussion

The compilation of these results seems to support the previous assumption that, with more time with texts and more exposure to controversial sociocultural issues, students begin to connect more with the material in less superficial ways and start to raise awareness of their societal predispositions on their own. Our results agree with Kubota and Lin (2009) , who propose that exposure to controversial cultural dispositions contributes to comprehending social identities in the EFL/ESL classroom. Furthermore, the data seem to show that, with more time and investment in an authentic oral text, once they had heard the entire story, the participants were more likely to share their opinion regarding aspects related to habitus and its construction. In other words, both participants showed more instances of hesitancy in the first two sessions than in the last part, where they seemed more open to sharing their thoughts.

One of the more interesting points concerning the analysis of the eight RGCs was the logical inconsistencies that occurred. For example, one of the most thought-provoking examples can be seen in Interview III, within turns 213 to 221, where Ashley expresses empathy, labeling, self-censorship, and negative self-identification within a brief period. We believe that this apparent contradiction among Ashley’s position possibly occurred because she was laying out her ideas again.

To a certain degree, the open and fluid conversations captured throughout the process seemed to provide more insight into underlying and subconscious beliefs and stereotypes of the participants that otherwise would not have surfaced. However, this sort of information about students can assist learners in their ongoing process of constructing habitus only if it is appropriately incorporated and brought to the surface by the moderator or other participants in the ongoing conversation or future class activities.

By analyzing the transcripts and researcher/ moderator memos [4] , the implementation of controversial sociocultural topics included in authentic audios fulfilled the general objective of raising participants’ awareness of the complexity and stereotypes/assumptions that correspond with the construction of their habitus. As previously stated, the students negotiated their cultural dispositions through student-teacher interactions and their own identities. According to Martin and Nakayama (2018) , the negotiation of meaning in communication entails a negotiation of identity. For example, Sara’s case is paradigmatic. In the first interview, Sara asserted:

He murdered his father, you don’t have... but it’s different to be culprit and to understand that […] He’s a villain. (Sara, Interview I)

We can observe how she configured the image of a mentally ill doctor who practices euthanasia as a ‘villain’. However, Sara reconsiders her dispositions in Interview II:

I think that at this point, he’s kind of a hero. (Sara, Interview II)

Therefore, we believe that the more students are exposed to controversy, the more they appraise their prejudices and stereotypes, as we could observe in Sara’s discourse (Interview III). In the same vein, the moments in which participants’ statements were categorized as self-identification and intercultural connection demonstrated the personal level at which the participants were engaging with habitus. For example, Ashley does not entirely identify herself with the character. Nevertheless, she was able to acknowledge that .there’s something wrong and maybe our responsibility is not how to be sano (sic), ok or well. (Ashley, Interview III).

These findings answer affirmatively that, in this particular study, the participants demonstrated an increased awareness of the ongoing process of constructing habitus, specifically addressing stereotypes of mental illnesses.

In addition, the use of controversial issues in authentic podcasts exhibited an essential role in surfacing these typically subconscious processes for discussion and evaluation. The most exciting result of this research was Sara’s final choice for her relationship with Vince, the documentary’s main character, who killed his father and suffered from Huntington’s disease. Earlier, Sara had placed more distance between her and Vince, seeing him as different. In the end, she chose to reevaluate her position towards Vince and express a feeling of similarity between the two due to her family’s mental health history, as can be seen in a previous extract (see Comparative analysis).

Of course, we do not see this research as the causality for the change in Sara’s perspective, but rather as an opportunity, a ‘cultural interstice,’ where she could flex and strengthen those critical thinking processes about identity.

Conclusion

Overall, this research provided opportunities to recognize EFL learners’ dispositions towards mental illness as a reciprocal set of practices. According to the data analysis, it seems reasonable to assert that the subjects involved in the study were able to confront their habitus and rebel against their fixed social practices and cultural dispositions. Undoubtedly, raising awareness regarding habitus encompasses a guided process that allows learners to gain more agency vis-à-vis stereotypes and assumptions, and, at the same time, allows them to learn a foreign language from a critical perspective ( Reay, 2001. Kubota and Lin, 2009. Rowlands and Gale, 2016). For example, students were able to listen actively and participated without paying attention to their language abilities. They got involved in the activity since the first encounter:

So, we’ve got to continue but not this Wednesday please, next Monday please... I want to know what is going to happen (Ashley, Interview I)

Although this study presents a common pedagogical strategy in EFL/ESL teaching, the topics in such tasks are not necessarily culturally and socially controversial within a regular lesson. When we teachers are open to controversies and include them explicitly in our materials, we allow students to debate and confront their prejudices and stereotypes. In that sense, language teaching becomes more than teaching a language. It may help learners be critical towards their cultural dispositions and learn to modify them, which indeed entails a profound pedagogical implication. Thus, language learning may help learners be aware of the prejudices that affect their own daily life and actions.

In other words, being aware of our habitus may help us be more conscious citizens who can coexist peacefully in a democratic society. Therefore, much is to be done in this area since the future pedagogical implications of explicitly dealing with habitus are still relatively unexplored in EFL/ESL teaching.

Limitations of the study

As a limitation, a difficulty observed in the implementation of these individual interviews was the questions from the moderator/researcher, who pushed both participants to share their opinions. Had it not been for this minor attribute in the plan, it is possible that Sara’s voice would have been heard even less.

Moreover, the authors recognize the specificity of this study and the limited nature of the results. This study explored only two cases. Although case studies do not intend to generalize data, the reduced number of cases may not manage to clearly define a set of cultural dispositions which could be attributed to a particular social group. Further research may include a more significant number of participants, which, eventually, may provide more instances for a broader comparative analysis.

Furthermore, future implementation of this framework could incorporate specific adjustments, such as re-analyzing the texts through critical discourse analysis or other analytical tools or methods. We acknowledge that this was the first attempt to attain clarity in the coding process to unveil more profound meanings, and that more discursive elaborations could have been elicited by increasing the number of informants, interviews, and rounds of analysis.

In addition, we believe that students should be presented with various themes throughout the research process in order to expand the understanding of their construction of habitus. In our case, the topic was quite limited to only one controversial issue because our focus was theoretical and methodological. After these results, we believe that further research is needed to evaluate and explore an array of controversial topics.

Similarly, the instruments of this research focused mainly on mental health, giving only a partial account for the crossed relation of other stereotypes and predispositions that may influence the students’ prejudices against mental issues.

Hence, future instruments may consider gender roles, sexual orientation, religion, among others. Similarly, further research could account for the image of ‘the mentally ill’ by searching for social representations of the concept that are present in discourse.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their profound comments and suggestions, which allowed us to improve the quality of this article.

References

Notes

Metrics

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Juan Eduardo Ortiz López, Tracey Keitt

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.