DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.12966Published:

2019-04-23Issue:

Vol. 21 No. 1 (2019): January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesThe professional development of English language teachers in Colombia: a review of the literature

El desarrollo profesional de docentes de Inglés en Colombia: una revisión de la literatura

Keywords:

Colombia, Educación, profesores de inglés, desarrollo profesional (es).Keywords:

Colombia, Education, English teachers, professional development (en).Downloads

References

Álvarez, G., & Sánchez, C. (2005). Teachers in a public school engage in a study group to reach general agreements about a common approach to teaching English. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 6, 119-132.

Atay, D. (2008). Teacher research for professional development. ELT Journal, 62(2), 139-147.

Burns, A. (2005). Action research. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 241-256). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cárdenas, M. L. (2004). English teachers’ research in a permanent teacher education program. (Trans.) Íkala, Revista de lenguaje y cultura, 9(15), 11-41.

Cárdenas, M., González, A., & Álvarez, J. A. (2010). El desarrollo profesional de los docentes de Inglés en ejercicio: Algunas consideraciones conceptuales para Colombia. Folios, 31, 49-68.

Cárdenas Beltrán, M. L., & Nieto Cruz, M. C. (2010). El trabajo en red de docentes de inglés [Teachers of English and their network]. Bogotá, CO: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Cárdenas, R., & Chaves, O. (2013). English teaching in Cali: Teachers’ proficiency level described. Lenguaje, 41(2), 325-352.

Castañeda-Londoño, A. (2017). Exploring English teachers’ perceptions about peer-coaching as a professional development activity of knowledge construction. HOW, 24(2), 80-101.

Castro Garcés, A. Y., & Martínez Granada, L. (2016). The role of collaborative action research in teachers’ professional development. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 18(1), 39-54.

Cely, R. (2007). Programa nacional de bilingüismo: En búsqueda de la calidad en educación. Revista Internacional Magisterio, 25, 20-23.

Chaves, O., & Guapacha, M. E. (2016). An eclectic professional development proposal for English language teachers. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 18(1), 71-96.

Clavijo, A., Guerrero, C. H., Torres, C., Ramírez, M., & Torres, E. (2004). Teachers acting critically upon the curriculum: Innovations that transform teaching. Íkala, Revista de lenguaje y cultura, 9(15), 11-41.

Colombian Ministry of Education (2005). Bases para una nación bilingüe y competitiva [online]. Al Tablero, 37. Retrieved from: http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-97594.html. [Link]

Craft, A. (2000). Continuing professional development. London: Routledge and Falmer.

Crandall, J. A. (2000). Language teacher education. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 20, 34-55.

Cullen, R. (1997). Transfer of training assessing the impact of INSET in Tanzania. In D. Hayes (Ed.), In-service Teacher Development: International Perspectives (pp. 20-36). London: Prentice Hall.

Díaz-Maggioli, G. (2003). Professional development for language teachers. Eric Digest EDO-FL, 03-03.

Espitia, M., & Clavijo, A. (2011). Virtual forums: A pedagogical tool for collaboration and learning in teacher education. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 13(2), 29-42.

Fandiño, Y. (2012). The impact of ICT training through wikis on In-service EFL teachers: Changes in beliefs, attitudes and competencies. HOW, 19, 11-25.

Farrell, T. (2006). The first year of language teaching: Imposing order. System, 34, 211-221.

Ferri, M., & Ortiz, D. (2007). Designing a holistic professional development program for elementary school English teachers in Colombia. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 8, 131-143.

Freeman, D. (2004). Implications of sociocultural perspectives for language teacher Education. In M. Hawkins (Ed.), Language Learning and Teacher Education (pp. 169-197). Great Britain: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Galvis, H. A. (2011). Transforming traditional communicative language instruction into computer-technology based instruction: Experiences, challenges and considerations. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14(2), 95-112.

García, M., & Rey, L. (2013). Teachers’ beliefs and the integration of technology in the EFL class. HOW, 20, 35-46.

García, R. E. (2013). English as an international language: A review of the literature. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(1), 113-127.

Giraldo, F. (2018). Language assessment literacy: Implications for language teachers. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 20(1), 179-195.

Guerra, J., Rodríguez, Z., & Díaz, C. (2015). Action research processes in a foreign language teaching program: Voices from inside. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 276-289.

Guerrero, M. (2012). The use of Skype as a synchronous communication tool between foreign language college students and native speakers. How, 19, 32-43.

Head, K., & Taylor, P. (1997). Readings in teacher development. Oxford: Heinemann.

Herrera, L., & Macías, D. F. (2015). A call for language assessment literacy in the education and development of teachers of English as a foreign language. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 302-312.

Jerez, S. (2008). Teachers’ attitudes towards reflective teaching: Evidences in a professional development program (PDP). Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 10, 91-111.

Johnston, B. (2009). Collaborative teacher development. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to language teacher education (pp. 241-229). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kohli, R., Picower, B., Martinez, A., & Ortiz, N. (2015). Critical professional development: Centering the social justice needs of teachers. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 6(2), 7-24.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Beyond methods: Macrostrategies for language teaching. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). Understanding language teaching: From method to postmethod. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates .

López, M., & Viáfara, J. (2007). Looking at cooperative learning through the eyes of public schools teachers participating in a teacher development program. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 8, 103-120.

López, A., & Bernal, R. (2009). Language testing in Colombia: A call for more teacher education and teacher training in language assessment. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 11(2), 55-70.

Macías, D. F. (2010). Considering new perspectives in ELT in Colombia: From EFL to ELF, How, 17, 181-194.

McDougald, J. (2013). The use of new technologies among In-service Colombian ELT teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(2), 247-264.

Montecinos, C. (2003). Desarrollo profesional docente y aprendizaje colectivo. Psicoperspectivas, 2(1), 105-128.

Muñoz, J. H., & González, A. (2010). Teaching reading comprehension in English in a distance web-based course: New roles for teachers. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 12(2), 69-85.

Pineda Hoyos, J. E., & Tamayo Cano, L. H. (2016). E-moderating and e-tivities: The implementation of a workshop to develop online teaching skills in in-service teachers. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 18(1), 97-114.

Quintero, A., & Guerrero, C. H. (2013). Of being and not being: Colombian public elementary school teachers’ oscillating identities. How, 20, 156-177.

Richards, J., & Farrell, T. (2005). Professional development for language teachers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

Rojas, J. (2008). Teacher collaboration in a public school to set up language resource centers: Portraying advantages, benefits, and challenges. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 10, 147-162.

Rojas, G. (2011). Writing using blogs: A way to engage Colombian adolescents in meaningful communication. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 13(2), 11-27.

Sánchez, N., & Chavarro, S. (2017). EFL oral skills behavior when implementing blended learning in a content-subject teachers’ professional development course. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 19(2), 263-276.

Shohamy, E. (2009) Language teachers as partners in crafting educational language policies?. Íkala, 14(22), 45-67.

Schön, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Sierra, A. M. (2007). Developing knowledge, skills and attitudes through a study group: A study on teachers’ professional development. Íkala, Revista de lenguaje y cultura, 12(18), 279-305.

Sierra Piedrahita, A. M. (2016). Contributions of a social justice language teacher education perspective to professional development programs in Colombia. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 18(1), 203-217.

Smagorinsky, P., Cook, L., & Johnson, T. (2003). The twisting path of concept development in learning to teach. Teachers College Record, 105(8), 1399-1436.

Smith, R. (2015). Teacher-Researchers in Action. Exploratory action research as work plan: why, what and where from? England: IATEFL Research Special Interest Group.

Sweeney, D. (2005). Learning along the way. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Torres-Rocha, J. C. (2017). High school EFL teachers’ identity and their emotions towards language requirements. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 19(2), 41-55.

Velandia, M., Pedreros, A., & Nuñez, M. (2012). Using web-based activities to promote reading: An exploratory study with teenagers. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 14(2), 11-27.

Vergara, O., Hernández, F., & Cárdenas, R. (2009). Classroom research and professional development. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development , 11, 169-191.

Viáfara, J. J. (2011). Reviewing the intersection between foreign language teacher education and technology. HOW, 18, 210-228.

Viáfara, J. J., & Largo, J. D. (2018). Colombian English teachers’ professional development: The case of master programs. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(1), 103-119.

Vo, L. T., & Nguyen, H. T. (2010). Critical friends group for EFL teacher professional development. ELT Journal, 64(2), 205-213.

Wallace, M. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

Williams, J. (2009). Beyond the practicum experience. ELT Journal, 63(1), 68-77.

Zúñiga, G., Insuasty, E., Macías, D., Zambrano, L., & Guzmán, D. (2009). Análisis de las prácticas pedagógicas de los docentes de inglés del programa Interlingua de la Universidad Surcolombiana. Revista Entornos, 22, 11-20.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 27 de enero de 2018; Aceptado: 21 de marzo de 2019

Abstract

This article offers a review of 25 empirical studies to identify the areas and findings of professional development initiatives for in-service English teachers in Colombia. The reviewed studies suggest that language teacher professional development has focused on six major areas: language proficiency, research skills and reflective practice, teachers’ beliefs and identities, an integrated approach to teacher professional development, pedagogical skills and teaching approaches, and emerging technologies. Results suggest that there is a need to move from traditional master-apprentice, content-oriented, teacher-centered models of professional development towards initiatives that allow teachers to critically analyze their particular context and needs, and devise their own local alternatives so that they can become more active agents of their own process of change. Issues that constitute possible alternatives for future research in the professional development of English language teachers are discussed.

Keywords:

Colombia, education, English teachers, professional development.Resumen

Este artículo ofrece una revisión de 25 estudios empíricos para identificar las áreas y los hallazgos de las iniciativas de desarrollo profesional para profesores de inglés en ejercicio en Colombia. Los estudios revisados sugieren que el desarrollo profesional del profesor de idiomas se ha centrado en seis áreas principales: suficiencia o dominio del idioma, habilidades de investigación y práctica reflexiva, creencias e identidades de los profesores, un enfoque integrado de desarrollo profesional docente, habilidades pedagógicas y enfoques de enseñanza, y tecnologías emergentes. La discusión de los hallazgos revela que existe la necesidad de pasar de los modelos tradicionales de desarrollo profesional orientados hacia el contenido y centrados en el docente, hacia iniciativas que permitan a los docentes analizar críticamente su contexto y necesidades particulares, y diseñar sus propias alternativas locales para que pueden convertirse en agentes más activos de su propio proceso de cambio. Se discuten temas que constituyen posibles alternativas para futuras investigaciones en el desarrollo profesional de profesores de inglés.

Palabras clave:

Colombia, educación, profesores de inglés, desarrollo profesional.The importance of professional development and continuous growth of language teachers has been recognized by various authors (Williams, 2009; Vo & Nguyen, 2010) in different settings and through a variety of methodological approaches. Teacher professional development has been defined as “a life-long process of growth which involve collaborative and/or autonomous learning… teachers are engaged in the process and they actively reflect on their practices” (Crandall, 2000, p. 36). Freeman (2004) uses the term ‘second language teacher education’ to refer to the professional preparation and the continuing professional development of teachers while Craft (2000) refers to professional development as a broad range of activities designed to contribute to the learning of teachers who have completed their initial training.

In light of the previous definitions, we use the term professional development here to refer to all types of professional learning undertaken by in-service English language teachers beyond the point of initial formal teacher preparation. Teacher professional development has followed many different approaches and strategies. Johnston (2009), for example, promotes the concept of collaborative teacher development as something that teachers can do with fellow colleagues, university researchers, students, or with others involved in teaching and learning. Craft (2000) provides a detailed list of methods that include self-directed study, teacher research, on-the-job coaching, mentoring or tutoring, learning partnerships, school cluster projects, personal reflection, collaborative learning, and technology-mediated learning. Richards and Farrell (2005) also suggest various approaches for the professional development of both new and in-service language teachers. Such approaches take the form of workshops, self-monitoring, teacher support groups, peer observation, teaching portfolios, analysis of critical incidents, peer coaching, team teaching, and action research. Even though many of those approaches promote long-term learning goals and may be centered on the teachers’ context, others such as workshops appear to stimulate short-term learning and may serve to reinforce more trainable skills.

In fact, Cullen (1997) states that teacher professional development has traditionally consisted of “short-term or one-shot in-service programs conducted by outside ‘experts’ who disseminated a knowledge base constructed again almost exclusively by ‘experts’” (as cited in Atay, 2008, p. 139). Many of these programs have become popular as they provide teachers with a break in the routine and a chance to meet colleagues and discuss stimulating new ideas. However, a recurring problem with these one-shot in-service programs is that the knowledge gained is generally disconnected from the teachers’ actual contexts and reality in both practical and conceptual terms.

In contrast, mentoring and coaching appeared to have been examples of what Sweeney (2005) calls professional development strategies by teachers as opposed to traditional approaches to teacher development by which an expert is brought in to deliver content or experiences which do not often relate to the audience. Sweeney (2005) also criticizes the short-term or one-shot in-service alternatives as they “fail to give teachers the time and support they need to learn” whereas, on the contrary, “the gradual release continuum embeds the essential elements for successful and long-term learning” (p. 4). To further illustrate, Sierra Piedrahita (2016) found that teacher development programs offered within the context of the National Bilingual Program in Colombia were short-term, lacked continuity, and focused on language issues and theories of language learning without much regard for opportunities “to understand [teachers’] role in society and their responsibility as agents of social change” (p. 215). Cárdenas and Nieto (2010) claim that for professional development programs to be successful, teachers’ personal and professional dimensions, knowledge, experiences, contexts, processes, and agendas need to be considered. This greatly aligns with the suggestions of Diaz-Maggioli (2003) who contends that professional development yields the best results when sustained over time in communities of practice and when focused on job-specific contexts and embedded responsibilities. In short, there seems to be a trend against the one-shot method described earlier, and in favor of professional development alternatives that are informed by teachers’ own knowledge, context, experiences, and communities of practice.

In the Colombian context, university teacher education programs (programas de licenciaturas) have usually been in charge of preparing English teachers and offering alternatives for their professional development. Yet the knowledge teachers gain through teacher education programs and courses becomes insufficient and may not always match the reality of the school context in which they have to start teaching. Many current in-service education and training programs “are often found to be unsatisfactory due to the fact that they do not provide the teachers with opportunities to be actively involved in their development and to reflect on their teaching experiences” (Atay, 2008, p. 139). This becomes much more evident when “the ideals that the beginning teacher formed during teacher training are replaced by the reality of school life where much of their energy is often transferred to learning how to survive in a new school culture” (Farrell, 2006, p. 212). Thus, since the knowledge teachers gain from the initial teacher education programs constitutes only a starting point in their career, teacher professional development initiatives should be aimed at reducing the impact of the challenges they encounter in their professional teaching.

In view of the previous situations, it is worth taking stock of what has been done in Colombia in terms of professional development initiatives for English language teachers. The purpose of this article, then, is to present a review of the literature in connection to studies aimed at the professional development of English teachers in Colombia. By doing so, we hope to contribute to not only gain a deeper understanding of the trends in professional development for language teachers in Colombia, but also to raise awareness of the issues that need to be included in future teacher development programs. Specifically, this review explores the following questions:

-

What areas have been the focus of professional development initiatives for in-service English teachers in the Colombian context?

-

What major findings have been reported in studies related to the professional development of in-service English teachers in Colombia?

Procedure

Initially, we established the criteria for including and excluding studies to be reviewed. We limited our search to studies in the field of English language teaching and teacher professional development in the Colombian context. Then, we consulted Google Scholar and entered the keywords “professional development,” “English language teachers,” and “Colombia.” The search was not limited to any time period and additionally involved consulting various publications and journals such as Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, Íkala, Lenguage, Folios, and How. We decided to exclude articles that did not report results of a research study or that had limitations in terms of providing accurate information about data collection, data analysis, participants, or other essential components of the research process. In contrast, we did not find books that specifically addressed the phenomenon of professional development in the field of English language education from a theoretical or research perspective in Colombia. The final corpus of this study was composed of 25 empirical studies from the 31 we had initially considered as relevant.

We analyzed each of the selected studies by designing a chart that served to identify some features of the research process including authors, data collection tools, duration of study, and major findings. This chart facilitated the subsequent comparative analysis of the studies. We focused our analysis at two levels. Level one centered on identifying the areas that had been the focus of professional development initiatives. Despite inevitable overlaps across some of the studies which made categorization a bit challenging, this analysis helped us evidence that teacher professional development initiatives in Colombia have focused on (1) language proficiency (n = 2); (2) research skills and reflective practice (n = 7); (3) teachers’ beliefs and identities (n = 3); (4) an integrated approach to teacher professional development (n = 3); (5) pedagogical skills and teaching approaches (n = 5); and (6) emerging technologies (n = 6). Level two considered an analysis of the main findings or outcomes as reported in the studies to identify changes in teacher professional development associated with the implementation of specific initiatives.

Areas and Findings in Language Teacher Professional Development

A growing body of literature has been devoted to promoting alternatives to help English language teachers in Colombia cope with their needs for professional development. Although the studies in this review considered questions that may be different in scope and complexity, concern with teacher professional development appeared to be at the core of all of them.

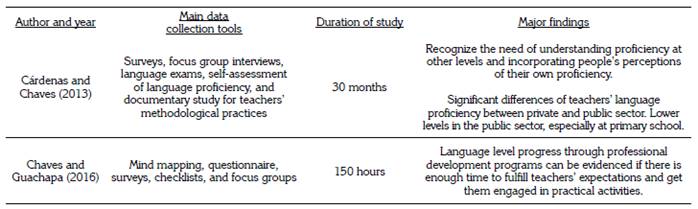

Language proficiency. In the literature on language teacher professional development in Colombia, teachers’ level of language proficiency has been widely considered a critical aspect in gaining teacher quality. The Colombian Ministry of Education argued that improving English teachers’ language level is one of the most noticeable needs to be addressed in the national context (Cely, 2007). Therefore, a series of general English courses and immersion programs offered by the Ministry, and often coordinated by local education authorities or higher education institutions, have been carried out to help English teachers in many different settings to improve their level of language proficiency (Colombian Ministry of Education, 2005). Interestingly, Table 1 shows that researchers have drawn attention to teachers’ language proficiency as determined by language tests, participants’ self-ratings, living and studying abroad experiences, and participation in professional development programs.

Table 1: Language Proficiency in Teacher Professional Development.

Cárdenas and Chaves (2013) revealed that there is a need to explore English teachers’ awareness of their language level using self-assessment and promoting more teacher-centered evaluations in which teachers are considered in their roles as language learners and become empowered by having a voice in the definition of their own proficiency level (Cárdenas & Chaves, 2013). The authors point out that this type of assessment “is one of the most participatory, democratic, and reflective possibilities that formative or informal evaluation offer” (p. 328). This view calls for a more active role of teachers in professional development programs aiming at enhancing language proficiency.

English teachers in Colombia are still in the process of building the proficiency levels sought by the Ministry of Education (i.e., CEFR level C1). However, since “policies are usually divorced from reality” (Shohamy, 2009, p. 46), massive diagnostic proficiency tests were not administered and studies of teachers’ working conditions were not conducted before establishing specific language policies (Cárdenas & Chaves, 2013). Unsurprisingly, the goals established by national bilingual program policies have not yet been accomplished. Another particular problem with current tests aiming at determining teachers’ English proficiency level is that they rely on computer or internet-based modes and this might affect the performance of teachers with limited computer skills. This new testing procedure, together with the fact that the assessment of listening and speaking skills is usually overlooked, might provide a less accurate view of teachers’ real proficiency in the language. This shows that appropriate conditions for professional development programs should be created and maintained if positive results are desired.

In reaction to the low English proficiency in the context of public education, Chaves and Guachapa (2016) implemented a professional development program with 63 teachers and reported that “language level progress was noticed as teachers started using more English and incorporating terminology related to tasks and CLIL; [while] their accuracy in pronunciation and vocabulary increased” (p. 13). These authors stress that since professional development is a good means to assure teacher quality, Colombian bilingualism policies should consider that the concept of teacher quality involves aspects beyond students’ and teachers’ results on language tests. In this sense, Chaves and Guachapa (2016) highlight four components of teacher quality (knowledge, practice, awareness, and image) that should be integrated in professional development initiatives. It follows that teacher development programs that combine language proficiency with other areas of the teaching profession might represent better opportunities for the enhancement of English teachers’ proficiency level. The previous studies develop the concept of professional development from a constructivist perspective in which teachers are expected to play a more active role and take center stage.

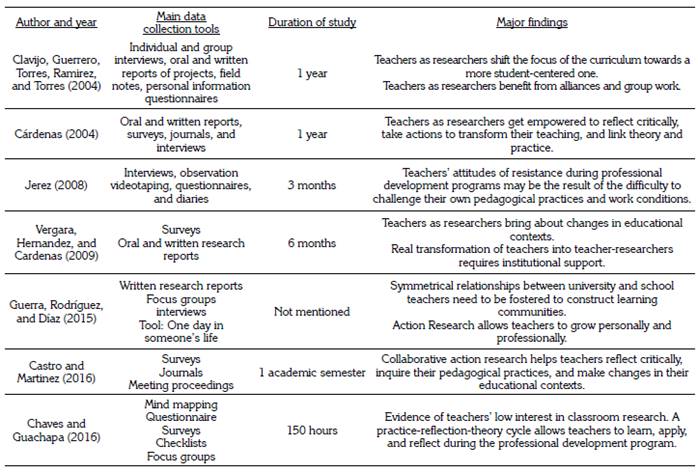

Research skills and reflective practice. Burns (2005) argues that reflecting critically and exploring a common problem in a specific context is necessary to gain understanding, create meaning, and improve educational practices. Not surprisingly, another series of studies in Colombia has been conducted to tackle language teachers’ needs related to research skills and reflective practice. The studies framed in this category generally rely on Diaz-Maggioli’s (2003), Montecinos’ (2003), Richards and Farrell’s (2005) conceptualizations of professional development as a process that entails teachers’ volunteer engagement, reflection, membership in communities of practice, transformations of reality, and new understandings of teaching and professional identity.

As depicted in Table 2, Clavijo, Guerrero, Torres, Ramírez, and Torres (2004) examined the process of innovation in language curriculum with a group of school teachers and observed that participants tended to think and reflect critically about their students’ needs and interests when planning and conducting curricular innovations. Likewise, Cárdenas’s (2004) study of the nature of English teachers’ research as part of a teacher education program similarly concluded that despite their limited background in doing research, their projects helped teachers to build a sense of empowerment in their profession. Findings in these two studies reinforced the importance of helping teachers see themselves as agents of change through the realization that their teaching could have a profound effect on their learners’ lives.

Table 2: Research Skills and Reflective Practice in Language Teacher Professional Development.

Similar to Castro and Martinez (2016), who found that classroom projects developed through collaborative action research positively impact in-service teachers’ reflective and research skills, Vergara, Hernández, and Cárdenas (2009) reported that through research seminars, project development, and communities of practice, teachers assume a better attitude toward identifying and solving problems in their educational contexts as well as building up the ability to work cooperatively and establish their cultural and professional identity.

Despite the benefits from conducting research, teachers are not always inclined to embark on that journey. Guerra, Rodríguez, and Diaz (2015) examined the impact of action research (AR) on the professional development of cooperating teachers in public schools during the academic practicum and reported that they “censored themselves to give opinions about students’ projects and did not value their expertise enough as school teachers and potential learners in AR processes” (p. 288). Cárdenas (2004) and Cárdenas et al. (2009) concluded that heavy workload, lack of institutional support, and paucity of knowledge hinder teachers’ involvement in research.

In contrast, teachers seem to get more easily involved in reflective processes. Jerez (2008) found that even though it was at first difficult for teachers to assume a reflective attitude, their active participation in a professional development program contributed to enhancing teachers’ awareness on the importance of reflection, and helped them to develop skills to be more reflective such as working with colleagues, sharing ideas, critically analyzing their actions, and evaluating the process they were following. Along similar lines, Chaves and Guachapa (2016) found that reflective skills are more effectively developed when teachers are exposed to a cycle of practice-reflection-theory as educators are able to critically assess and comprehend their practices and connect them with underlying principles.

The previous studies clearly embody the cooperative process view of professional development that stresses the importance of reflection, critical and analytical awareness, and the need to share classroom experiences and knowledge with peers as a catalyst for personal and professional growth. Various forms of action research (e.g., collaborative, exploratory, participatory) appear to be the most preferred approaches to research and reflective skills development. Even though Smith (2015) suggests that exploratory action research may be of help “as a gradualist approach, developed to be useful for induction into teacher-research in difficult circumstances” (p. 39), there is an urgent need to get institutional stakeholders involved in professional development programs if more positive outcomes are desired in the long run.

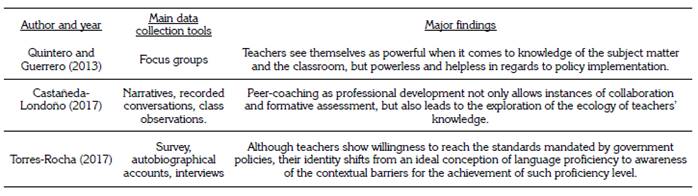

Teachers’ beliefs and identities. Although to a lesser extent, the area of teachers’ beliefs and identities has gained importance in the last few years. Exploring teachers’ identities, beliefs, and personal values contributes to understanding the decisions that teachers have to make as they engage with the teaching process and the position they assume as agents of change in the school system. Table 3 illustrates how school teachers’ experiences, beliefs, and knowledge of the socio-cultural and socio-political context have been seemingly undervalued by the Colombian Ministry of Education.

Table 3: Teachers’ Beliefs and Identities in the Context of Teacher Professional Development.

In investigating the voices of elementary school teachers regarding Colombian language policies, Quintero and Guerrero (2013) found that even though school educators are seen as the “non-knowers” that “implement” policies, they actually possess significant local knowledge that can contribute to the educational processes of the country. Torres-Rocha (2017) similarly explored the influence of the National Bilingual Program on the reconstruction of teacher identity and found that although “teachers knew about the language policies and language requirements, most of them did not feel that they had access to opportunities for development, demonstrating that power relations shape identity” (p. 12). Finally, Castañeda-Londoño (2017) claims that peer coaching as professional development represents an instance of reconstruction of teacher identity in regard to self-image, intimidation, self-understanding, and self-improvement. An outstanding finding of this study is that teacher-led professional development activities are seen as an opportunity for educators “to socialize their existing knowledge or their own constructions of theories and in-situ understandings” (p. 97). From this perspective, educators could be perceived as knowledgeable beings that can make significant contributions to the formulation of educational policies.

The findings from the studies above provide the English language teaching community with concrete evidence that the concept of Critical Professional Development (CPD) needs to be promoted among Colombian teachers. Kohli, Picower, Martínez, and Ortiz (2015) claim that CPD programs “are organized through shared power, where teachers are framed as experts and feel agency to co-construct the PD” (p. 16). Likewise, CPD prepares educators to develop their critical consciousness and transform teaching in a way that challenges that “model of education that treats teachers as empty receptacles” (Kohli et al., 2015, p. 3).

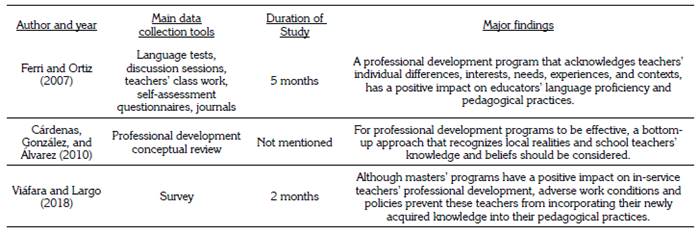

An integrated approach to teacher professional development. Other initiatives for the professional development of language teachers in Colombia reveal a combined or integrated approach. As Table 4 shows, three studies emphasize the significance of locally produced knowledge and the need of collaborative work between policy makers and teachers to generate more adequate teacher professional development programs for the Colombian context.

Table 4: Integrated Approaches to Language Teacher Professional Development.

To further illustrate this point, Ferri and Ortiz (2007) focused on the design of a holistic professional development program which sought to integrate strategies directed at improving teachers’ target language and reflective practice based on principles of theme-based instruction as part of an action research study. The authors reported that administrative support and educational policies that are sensitive to teachers’ needs and realities can help create adequate conditions for future professional development. This study has been one of the few that sought to combine the views of training and development (Richards & Farrell, 2005) since it aimed at integrating discrete and trainable aspects with more complex features of teaching.

Contrary to this, Cárdenas, González, and Álvarez (2010) claim that new proposals for professional development programs in Colombia should use teacher development and not teacher training. The way we see it, however, is that much has been said about how training and development serve different purposes when the tendency should be that “it is more useful to see [them] as two complementary components of a fully rounded teacher education” (Head & Taylor, 1997, p. 9). These two views give evidence of the complexity of teaching and remind us that knowing how to teach involves more than just following prescribed routines. It also requires thinking over the decisions that teachers make in class, and interpreting and reflecting on the interplay of factors that seem to govern the preparation of language teachers. Other considerations by Cárdenas et al. (2010) such as individual and social perspectives of learning and teaching, post-method approaches, creation of knowledge in school and social settings, and promotion of meaningful practices among teachers are, nonetheless, worthy of inclusion in the design of teacher development programs.

Viáfara and Largo (2018) reported that postgraduate programs, teachers’ number one option for continuing their preparation, facilitate teachers’ analysis of educational policies, their reflective skills, and curricular knowledge. More awareness of the relevance of doing classroom research to innovate, and the feeling of empowerment to be able to adjust institutional educational policies were other relevant findings in this study. These authors equally remark that postgraduate programs should include more issues about language education policy and program administration as well as employ more methods of inquiry that go in line with teachers’ contextual needs and working conditions.

The aforementioned studies converge on the idea that language teacher professional development should be defined in the light of principles such as particularity, practicality, and possibility (Kumaravadivelu, 2003). This implies that the design, planning, and implementation of professional development programs should consider aspects such as local contexts, teachers’ knowledge, practical personal theories, beliefs, and socio-cultural issues. Likewise, these studies call for the involvement and participation of institutional stakeholders in order to ensure continuity in research and sustainability of reflective and innovation practices once professional development programs are over.

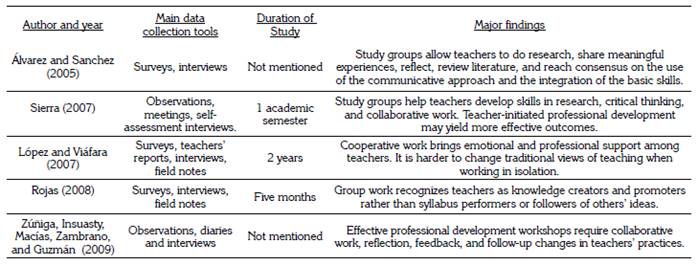

Pedagogical skills and teaching approaches. The area of pedagogical skills and teaching approaches has not escaped the interest of teachers and teacher developers. As shown in Table 5, studies in this area have focused on using teachers’ study groups to develop knowledge, attitudes, and skills to teaching (Sierra, 2007), and to determine appropriate approaches to teaching English (Álvarez & Sánchez, 2005). The use of study groups in these projects proved to help participants update professional knowledge and expertise and build positive expectations regarding students learning.

Table 5: Pedagogical Skills and Teaching Approaches in Teacher Professional Development Programs.

Other studies in this area include looking at how a group of public school teachers used cooperative learning in their classes (López & Viáfara, 2007), and a teacher collaboration project to implement a language resource center at an institution (Rojas, 2008). These studies revealed that teachers’ self-encouragement for professional development emerged as a fundamental issue when they implemented cooperative learning in their institutions. Rojas (2008) showed that the main benefits in connection to teachers’ professional development, resulting from taking part in the teacher collaboration project, were social (e.g., communication and respect for others’ ideas) and pedagogical (e.g., spontaneity and self-confidence when teaching).

With respect to teaching methods and approaches, it appears that communicative language teaching is still the preferred approach to English language teaching not only in the setting studied by Álvarez and Sánchez (2005) but also in other contexts in Colombia (Zúñiga et al., 2009). In this regard, teacher development programs should expose teachers to other trends in language teaching methods and approaches including but not limited to content and language integrated learning, and literacy-based approaches.

The studies analyzed in this section suggest that group work has the potential to help teachers build professional communities of practice and offer a school-based approach for educators’ professional growth. However, three of these investigations (López & Viáfara, 2007; Rojas, 2008; Sierra, 2007) reported that the biggest challenge teachers have when trying to form study groups to collaboratively transform their pedagogical practices is the lack of institutional support and the existence of school policies that promote silent classrooms with students sitting in rows.

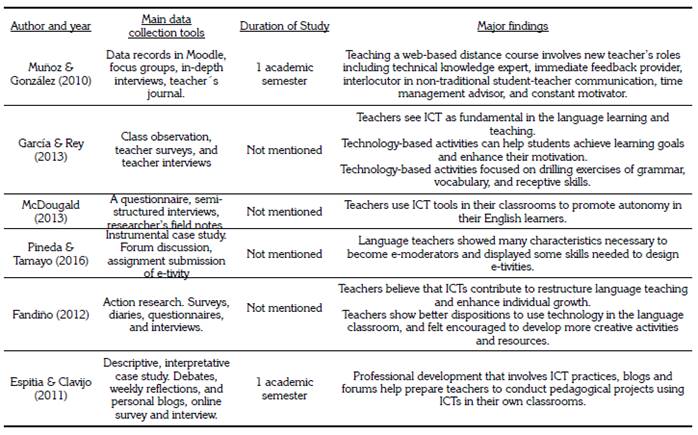

Emerging technologies. The use of emerging technologies in foreign language education has been of great interest to teachers and scholars in Colombia. However, most of the research conducted in this area has been at the level of teaching or facilitating the acquisition of specific language skills to groups of students across different levels of education (Galvis, 2011; Guerrero, 2012; Rojas, 2011; Velandia et al., 2012). In contrast, technology-mediated alternatives for language teacher professional development have been slightly less predominant. Table 6 shows that most studies in this area have sought to examine language teachers’ roles, beliefs, attitudes, and competences as well as teachers’ realization of the uses and benefits of specific technologies for language learning and teaching.

Table 6: Technologies and the Professional Development of Language Teachers.

In looking at the teacher’s role and interaction in an EFL reading comprehension distance web-based course, Muñoz and González (2010) found that in these new scenarios, teachers were called to play roles such as solving technical problems, providing immediate feedback, interacting with students in a nontraditional way, providing time management advice, and acting as constant motivators. Teachers similarly required training for these new roles and active participation in the analysis and construction of web-based learning environments. In another study, García and Rey (2013) explored teachers’ beliefs in connection to the implementation of technology-based activities in EFL classes and found that such activities contribute to promoting motivation, reinforcing topics already studied in class, and helping students achieve their learning outcomes. Nonetheless, many of the implemented activities “were oriented toward drilling exercises of grammar and vocabulary and listening and reading tasks” (p. 62) with limited opportunities for promoting interaction among the students. Teachers similarly play a rather passive role as they simply sit and wait for students to complete the given tasks.

McDougald (2013) also reported the influence of the integration of ICTs into graduate courses. Results showed that a growing number of teachers are using technological tools on a regular basis in their classrooms and the majority of them revealed high satisfaction in using digital technologies to motivate and build autonomy among their language learners. Participant-teachers also claimed to rely on technologies to help their students improve various aspects including pronunciation, fluency, and accuracy. Similarly, Pineda and Tamayo (2016) responded to teachers’ needs regarding the development of competencies involving e-moderation and the design of e-tivities to embed technology into their teaching. One particular feature of their professional development program that stood out was that it focused on both the instrumental use of the tools and their pedagogical use. The use of ICTs, particularly wikis, blogs, microblogs, e-mail communication, and forums in the professional development of in-service language teachers (Espitia & Clavijo, 2011; Fandiño, 2012) suggests that working with new technologies can have a positive impact on teachers’ practices, attitudes, and competencies.

Conversely, Viáfara (2011) argues that “the impact of these tools has not influenced the pedagogy of foreign languages as substantially as was predicted” (p. 210) and concludes that “teacher educators’ preparation to instruct practitioners in the use and subsequent integration of technology in classrooms stands as a priority” (p. 223). Other authors (Chaves & Guapacha, 2016; Sánchez & Chavarro, 2017) claim that most English teachers in public schools are not fully familiar with the use of ICTs or simply “lack the knowledge and skills regarding the use of technological resources” (Sánchez & Chavarro, 2017, p. 264), and that is why they turn to traditional resources. Thus, these authors call for the development of more digital literacies among teachers including the use of a blended learning approach in professional development initiatives if traditional conceptions of teaching are to be transformed. A final consideration observed in many of the previous studies relates to a growing awareness among language teachers that emerging technologies constitute an area of significant concern in their professional development. In fact, their beliefs in this regard “seemed to move from a rather technophobic posture, in which technology appears to be strange and difficult, to a technophilic position where the potentials and benefits of technology are acknowledged (Fandiño, 2012, p. 19).

Discussion and Conclusions

We have examined a representative sample of studies and initiatives conducted in Colombia to aid the professional development of English teachers. This review of the literature led us to identify the six areas previously described to be the focus of research in the Colombian context. In view of the growing number of studies on language teacher development in the country, the future of professional development for English teachers looks promising with the advent of new trends that are beginning to attract the attention of those concerned with offering these teachers new possibilities to improve what they do. All in all, there seems to be more awareness on the part of teacher educators and researchers to design professional development alternatives that involve an emphasis on social interaction and on the reality of local contexts. This takes further relevance if we consider that theoretical frameworks for the design and implementation of teacher education and development programs suggest moving away from the traditional master-apprentice, content-oriented, teacher-centered models towards a practice which aims to enable teachers to analyze their context and needs more critically and devise their own local alternatives (Kumaravadivelu, 2006; Smagorinsky et al., 2003).

Looking across the studies, we conclude that language teacher professional development in Colombia is transitioning from applied science (Schön, 1987) and reflective-cooperative-process models (Wallace, 1991) towards more critical ones in which basic aspects such as the design criteria for professional development programs, teachers’ roles, and teachers’ ways of learning, have been redefined. First, the design of teacher professional development programs should consider a bottom-up approach in which teachers’ beliefs, identities, learning styles, needs, interests, and the needs of local socio-cultural contexts to obtain more positive and lasting results. Second, school teachers are now considered “knowers” (Quintero & Guerrero, 2013) that should share power with policy makers and university teacher educators so that they can have a voice in the design, planning, and implementation of language policies. Apart from being researchers and reflective practitioners, language teachers are called “to start acting as transformative intellectuals [that have] sociopolitical conscious[ness] and stretch their role beyond the borders of the classroom” (Kumaravadivelu, 2003, p. 14). Thirdly, the way teachers learn has shifted from isolated work to communities of practice, from training to development, from imposed to self-initiated, from training on methodological areas to developing research and reflective skills. However, it was evidenced that teacher learning as a result of professional development programs not only depends on the strategies used, but also relies on institutional support. There is an urgent call for school administrators to become aware of the need to help teachers do research and engage in critical reflection by allocating time and resources. At the same time, if school administrators do not recognize their teachers as valuable assets within their institutions, educators will continue to feel ineffective, with interests and ideas that are not worth exploring (Cárdenas, 2004).

The changes and seemingly emerging tendencies in language teaching and teacher education (identity, differentiated instruction, gender blindness, translanguaging, and social, linguistic, and cultural diversity) as evidenced in the 53rd ASOCOPI Annual Congress (2018) lead us to suggest that teacher professional development initiatives in Colombia should not only have as a goal to create “optimal conditions for desired learning to take place in as short a time as possible” (Kumaravadivelu, 2003, p. 6), but also to engage “teachers in alternative pedagogical methods that are equity and justice focused” (Kohli et al, 2015, p. 9). Although some of the studies reviewed here seem to constitute a partial response to this goal, additional efforts are still required.

Despite the great variety of studies and projects carried out in Colombia in regards to the professional development of language teachers, areas such as language assessment literacy (Giraldo, 2018; Herrera & Macías, 2015; López & Bernal, 2009) and the pedagogical implications of English as an International Language (García, 2013; Macías, 2010) are still in need of further exploration from the perspective of teacher education and professional development. There is also a need for designers and facilitators of professional development programs to further explore the concept of Critical Professional Development in an attempt to empower English language teachers to act and feel confident enough to transform their pedagogical practices and professional contexts. More approaches that involve elements of participatory action research and social justice may be worth pursuing to meet the previous needs.

References

Metrics

License

Copyright (c) 2019 Ximena Paola Buendia, Diego Fernando Macías

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.