DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.14177Published:

2019-11-07Issue:

Vol. 21 No. 2 (2019): July-DecemberSection:

Research ArticlesIntercultural awareness and its misrepresentation in textbooks

La conciencia intercultural y su tergiversación en los libros de texto

Keywords:

enseñanza del inglés, conciencia intercultural, cultura, políticas lingüísticas, competencia comunicativa intercultural (es).Keywords:

English teaching, intercultural awareness, culture, language policies, intercultural communicative competence (en).Downloads

References

Bonilla, C. A., & Tejada-Sánchez, I. (2016). Unanswered questions in Colombia’s language education policy. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 18, 185-201.

Bonilla Medina, X. (2008). Evaluating English textbooks: A cultural matter. HOW Journal, 15(1), 167-191. Retrieved from https://www.howjournalcolombia.org/index.php/how/article/view/93.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M., & Zarate, G. (1997). Definitions, objectives and assessment of socio-cultural competence. In M. Byram, G. Zarate & G. Neuner (Eds.), Socio-cultural competence in language learning and teaching (pp. 9-43). Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers. The Council of Europe. Retrieved from http://lrc.cornell.edu/director/intercultural.pdf.

Canagarajah, A. (Ed.). (2005). Reclaiming the local in language policy and practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers.

Cárdenas, M. L., González, A., & Álvarez, J. A. (2010). El desarrollo profesional de los docentes de inglés en ejercicio: Algunas consideraciones conceptuales para Colombia. FOLIOS, 31, 49-68. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/folios/n31/n31a04.pdf.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Fries, K. (2008). Research on teacher education: Changing times, changing paradigms. In M. Cochran-Smith., S. Feiman-Nemser., J. McIntyre & K. Demers. (Eds.), Enduring questions in changing contexts: The third handbook of research on teacher education. London: Taylor and Francis Publishers.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. New York: Routledge. Retrieved from https://islmblogblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/rme-edu-helpline-blogspot-com.pdf.

Colombia Aprende. (2014). Colombia Very Well! [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kZIv7LMNQwY&feature=youtu.be

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/1680459f97.

De Mejía, A. M. (2012). Bilingualism, opening to the world and appreciating pluralism and difference. Revista Internacional Magisterio. Educación y Pedagogía, 58, 14-23.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogía del oprimido. México: Siglo XXI Editores.

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the word and the world. London, UK: Routledge.

Henao, E. A. (2015a). From reading lyrics to the creation of multimodal texts: Reading the word and the world with young learners from a public high school in Colombia. Paper presented at TESOL Colombia I: Innovations in language learning and teaching, Universidad de la Sabana, Chía, Colombia.

Henao, E. A. (2015b). Cultural and social awareness through context and reality as texts. Paper presented at Segundo congreso internacional: Lectura y escritura en la sociedad global, Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla, Colombia.

Henao, E. A. (2017). Intercultural awareness activities in Colombian language policy: English, Please! Series (Master thesis). Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Medellín, Colombia.

Janks, H. (2014). Critical literacy’s ongoing importance for education. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 57, 349-356.

Kramsch, C. (2001). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lau, S. M. C. (2012). Reconceptualizing critical literacy in ESL classrooms. The Reading Teacher, 66, 325-329.

Luke, A. (2012). Critical literacy: Foundational notes. Theory Into Practice, 51, 4-11.

McDonough, J., & Shaw, C. (1993). Materials and methods in ELT. Blackwell.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (1999). Lineamientos curriculares. Idiomas extranjeros. Bogotá, Colombia: Cooperativa Editorial Magisterio.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2006). Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: Inglés. Guía 22. Bogotá, Colombia: Ministerio de Educación Nacional.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2013a). English, Please! 1. Bogotá D.C., Colombia: Imprenta Nacional de Colombia.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2013b). English, Please! 2. Bogotá D.C., Colombia: Imprenta Nacional de Colombia.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2013c). English, Please! 3. Bogotá D.C., Colombia: Imprenta Nacional de Colombia.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2014). Programa nacional de inglés 2015-2025: Documento de socialización [HTML]. Retrieved from http://docplayer.es/9063122-Programa-nacional-de-ingles-2015-2025-documento-de-socializacion.html.

Mora, R. A. (2012). Literacidad y el aprendizaje de lenguas: Nuevas formas de entender los mundos y las palabras de nuestros estudiantes. Revista Internacional Magisterio, 58, 52-56.

Morrell, E. (2005). Critical English education. English Education, 37, 312-321.

Quintero, J. (2006). Contextos culturales en el aula de inglés. Íkala. Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 11(1), 151-177. Retrieved from https://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/ikala/article/view/2784/2239.

Rivas, J. M. (1993). El latín en Colombia: Bosquejo histórico del humanismo colombiano (3rd ed.). Bogotá, Colombia: Instituto Caro y Cuervo.

Shohamy, E. (2008). Overview language policy and language assessment: Relationship. Current Issues in Language Planning, 9, 363-373.

Tomlinson, B. (Ed.). (2003). Developing materials for language teaching. London: Continuum Press.

Usma, J. A. (2009a). Education and language policy in Colombia: Exploring processes of inclusion, exclusion, and stratification in times of global reform. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11, 123-141. Retrieved from https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/download/10551/11014.

Usma, J. (2009b). Globalization and language and education reform in Colombia: A critical outlook. Íkala. Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 14, 19-42. Retrieved from https://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/ikala/article/view/2200/1773.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 30 de noviembre de 2018; Aceptado: 19 de noviembre de 2019

Abstract

The role of culture and intercultural awareness in the language classroom is not a new area of research in ESL/EFL, and its relative importance has shifted in different approaches and methods of foreign language teaching. Today, the goal of some English textbooks has transcended a pure linguistic and language training orientation as text developers have moved towards also teaching intercultural awareness. The development of intercultural awareness was presented as a key component in ensuring the success of the latest Colombian National Bilingual Programme 2015-2025 (NBP), and the textbook series English, Please! was promoted as a breakthrough in this context. This article presents the research analysis and findings of an exploratory study based on the ambitious task set forth in the NBP policy on English textbooks. We examine the theoretical constructs adopted by the National Ministry of Education and by using, both quantitative and qualitative, analysis we explore the intercultural awareness activities presented in the series. At the end, we suggest that although the series is an important addition to existing materials in the area, it presents an overly reductionist and instrumentalist use of the concept of intercultural awareness.

Keywords:

English teaching, intercultural awareness, culture, language policies, intercultural communicative competence.Resumen

El papel de la cultura y la conciencia intercultural en el aula de idiomas no es un área nueva dentro de las investigaciones en ISL/ILE, y su importancia ha venido evolucionando en los diferentes enfoques y métodos de enseñanza en lenguas extranjeras. Hoy en día, el objetivo de algunos libros de texto sobre el idioma inglés ha trascendido una orientación puramente lingüística o de aprendizaje en la estructura de una lengua, ya que los autores de textos avanzan hacia la posibilidad de un aprendizaje que involucre la conciencia intercultural. El desarrollo de la conciencia intercultural fue presentado como un componente clave para asegurar el éxito del reciente Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo de Colombia (PNB) 2015-2025 dentro de la serie de libros de texto English, Please!, la cual fue promovida como un gran avance. Este artículo presenta el análisis y los resultados de un estudio exploratorio basado en la ambiciosa tarea establecida en la política del PNB sobre los libros de texto en mención. En este estudio se examinan los constructos teóricos adoptados por el Ministerio de Educación Nacional y mediante un análisis tanto cuantitativo como cualitativo se exploran las actividades de conciencia intercultural presentadas de la serie English, Please! Al final, los autores sugieren que aunque la serie constituye un adelanto importante frente a los materiales existentes en el área, presenta también una comprensión y un uso instrumentalista y reduccionista de lo que hoy en día conocemos como conciencia intercultural.

Palabras clave:

enseñanza del inglés, conciencia intercultural, cultura, políticas lingüísticas, competencia comunicativa intercultural.Introduction

In July 2014, the Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN) launched Colombia Very Well! 2015-2025 as the new version of the previous National Bilingual Programme (NBP). This program was intended for the improvement of English language education among Colombian public high school students. At the very core of the program, they projected the adoption and implementation of the English, Please! series and all its ancillary materials. This series was announced in an online document by MEN which presented the NBP as one of its major components and planned the distribution of up to six million copies (MEN, 2014). In 2015, distribution began, and each textbook included a letter by the former Minister of Education, María Fernanda Campo, who explicitly presented the series as “an important step forward in the promotion of intercultural awareness in the learning of English in Colombian high school students” (MEN, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c, preface-translation ours).

Purpose of the study

The main objective of this study was to examine the English, Please! series and analyze whether the series achieves the goals declared in the introductions to the textbooks. Further objectives were:

-

To tally the activities which strengthened intercultural awareness according to the definitions of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, or CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001).

-

To identify activities which demonstrate a potential to be intercultural in terms of the definitions of the CEFR.

Research question

Which kinds of activities in the English, Please! series aim at the production of intercultural awareness?

Sub question:

What percentage of the activities in the English, Please! series can currently be classified as intercultural awareness activities?

Background: interculturality and language policies in Colombia

Language policies in Colombia: a tension between the local culture and the Eurocentric culture

From the very beginning, the MEN officially embraced a foreign model for language education in Colombia as they adopted the CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001), which was also at the core of the early NBP in 2004. However, scholars and English language teachers have resisted this model since it is considered Eurocentric, and they claim that Colombian language policies have historically been shaped and influenced by foreign models (de Mejía, 2012; Rivas, 1993). An exception is the national policy established in 1826. This policy was revolutionary in that time as it did not only promote the learning and teaching of several European languages (including English, French, Latin and Greek), but also embraced the education of the ancestral Colombian language associated with the location of each individual school. (Bonilla & Tejada-Sánchez, 2016; Henao, 2017).

Teachers and scholars have raised the above concerns because they value the inclusion of diverse voices in the construction of educational agendas and object to the high level of intervention by transnational companies in the implementation of educational reforms. They claim that a more realistic approach for meeting the challenges of global and local educational needs should aim at tackling the considerable social gaps in and diversity of contexts and cultures (Shohamy, 2008; Usma, 2009a, 2009b). They also stress the fact that both teachers and institutions have been appropriating and readapting language policies to serve the real needs of language learners in different contexts throughout Colombia (Cárdenas, González & Álvarez, 2010; Cochran-Smith & Fries, 2008; Henao, 2015a, 2015b; Quintero, 2006; Usma, 2009a).

Some recent academic symposia and conferences have revolved around the areas of culture, intercultural awareness, interculturality and language education in Colombia. Examples of this trend include: the 2017 Intercultural Educational Proposals Promoting Bilingual and Multilingual Teaching Trajectories: Co-Constructing Teacher Development in the 21st Century, held at Universidad de los Andes; the 2017 ASOCOPI Annual Congress, ELT Classroom Practices and the Construction of Peace and Social Justice and most recently, the 2018 Second International Symposium: Interlingual and Intercultural Contacts. All these events have become discursive spaces, in which preservice and in-service practitioners reflect and share views and pedagogical experiences vis à vis the ideas of local and international presenters. However, the bottom line throughout is the discussions on the approaches to the teaching of languages from an intercultural perspective.

It is becoming more evident that in the Colombian context two theoretical constructs coexist: on one side, the Eurocentric one supported by the government, and on the other side, the local, decolonial, Southcentric one. The former unquestioningly adopts the CEFR for language education in Colombia, and the latter is reflected by the various researchers who have been questioning foreign models while advocating for local and popular ones.

Textbooks and materials as local empowerment

Language teaching has undergone a process of transformation in recent decades. Traditional methods concentrated in developing students’ linguistic skills in heavily grammar-oriented environments. Nowadays, language teaching is seen more as a life-long process, and language teaching has become a profession permeated with ethical, cultural and political ideas. The kind of material language teachers use in a class become crucial not just in language learning, but also in how they shape and transform the students they educate. The cultures, methods, competences and ideologies educators favour will inevitably be conveyed to students during the language learning process (Freire, 1970; Lau, 2012; Morrell, 2005). Materials and textbooks used in second language classrooms are expected to have the potential to connect teachers’ experiences, knowledge and expertise with their students’ lives, needs, expectations and language level. Textbooks and materials should ideally demonstrate respect for and interaction with local culture, history, linguistic diversity, values and traditions; and encourage an environment in which no teacher, or student feels marginalized or neglected. In other words, they should foster a space in which language users can read the word and the world (Canagarajah, 2005; Freire, 1970; Freire & Macedo, 1987; Janks, 2014; Kramsch, 2001; Luke, 2012; Mora, 2012).

Research design

To achieve the goals of the research project, we adopted the content analysis model by Cohen, Manion & Morrison (2007). This mainly entailed the use of the four C’s approach: coding, categorizing, comparing and concluding. For the content analysis of the English, Please! series, we used the following eleven steps proposed in this model:

-

Formulate the research question that should be derived from the text or material to be analyzed.

-

Define the population from which samples are to be collected. According to Cohen et al. (2007), the word population “refers not only to people but also, and mainly, to text-the domains of the analysis” (p. 477).

-

Decide on the sample(s) to be included and the strategy of sampling, with regard to the key aspects of sampling that include “representativeness, access, sample size and generalizability of the results” (Cohen et al., 2007, p. 477).

-

Define the environment and the origin of the text. It is important to know, for example, how and why it was created, where it comes from and how it was written.

-

Create the elements of analysis, e.g. words, sentences, paragraphs, graphics, symbols, people, themes, etc. This is where both the coding and the contextual units must be distinguished; the former indicating the smallest analysable element of the material, the latter meaning the largest textual unit.

-

Develop codes to be used in the analysis. Codes can be general, or more specific. Each datum has a word or abbreviation ascribed to it which must clearly represent what it stands for. This way, data patterns can be easily detected.

-

Create the categories for the analysis. Categories can be defined as “the main groupings of constructs or key features of the text, showing links between units of analysis” (Cohen et al., 2007, p. 478). A category can represent the words, phrases, sentences or other units of text which share a similar meaning.

-

Categorize and code the data. This entails the attribution of codes and categories to each piece of data. Codes and categories can be decided upon in advance (as seen in steps 6 and 7) or retrospectively, i.e. “in response to the data that have been collected” (Cohen et al., 2007, p. 480).

-

Conduct the data analysis. The researcher may count the number of occurrences of each code in the text, as well as the number of codes in each category. Some codes may be ranked in more than one category. Having calculated the frequencies, statistical analysis can be performed, such as tabulation, graphical representation, regression, etc.

-

Summarize the main features of the situation. The summary will identify key aspects, topics, concepts and areas for subsequent investigation.

-

Making hypothetical inferences. This moves the research process from description to inference by drawing conclusions from the summarized results.

Population and context of the series

According to step 2, population can refer to textbooks. In this case, the population is the English, Please! series, a high school-level collection of textbooks and supporting materials intended for 9th, 10th and 11th graders in the Colombian high school system. This series is the first in Colombian history to be delivered by the MEN for public high schools in the country. They were developed as a result of an interinstitutional agreement between the MEN and the British Council, with support from the Fundación Empresarios por la Educación. The series consists of a kit containing material for each level (1, 2 and 3, for grades 9, 10 and 11, respectively). The set of materials for each level includes: one student’s book, one teacher’s guide, an accompanying audio CD and an online workbook. Each English, Please! level contains four modules, and each module focuses on a different topic. For each topic, students complete a project designated by the textbook. The modules start with an introductory section in which every new topic is explored. The expected language learning outcomes and the final project are also presented. Following the introduction, there are three units, each including number of lessons. The first two units explore different subtopics related to the module topic and provide students with activities for practising language strategies that will allow them to work on various aspects of the final project. Following are some of the activities incorporated into each lesson:

Get ready!: These activities are generally found at the beginning of every lesson, and students are invited to answer questions about the topic of the lesson. This is a space to increase vocabulary, initiate discussion, invite students to share opinions and bring in their background knowledge to generate interest in the new topic.

Language skills: Speaking, listening, reading and writing: These traditional skills are identified with specific icons in the textbook. A microphone represents speaking skills, earphones represent listening skills, a book represents reading skills and a pencil represents writing skills. These activities may involve using a skill in isolation, or in combination with another. In such cases, two icons are used.

Focus on language: This subtitle indicates activities in which students try to comprehend how language functions. When this subtitle appears, learners are expected to discover the language forms and the rules by themselves with minimal guidance from the teacher. It is an inductive instruction strategy and a much more student-centered approach than more traditional activities.

Tips: These small text boxes provide students with advice on the most effective learning strategies. For example, in a box on listening tips: “Don’t worry if you don’t understand everything, concentrate on the specific words you need for the activity” (MEN, 2013a, p. IV).

Focus on vocabulary: This subtitle indicates activities in which students should work to grasp understanding and use of key vocabulary and functional language from the textbook.

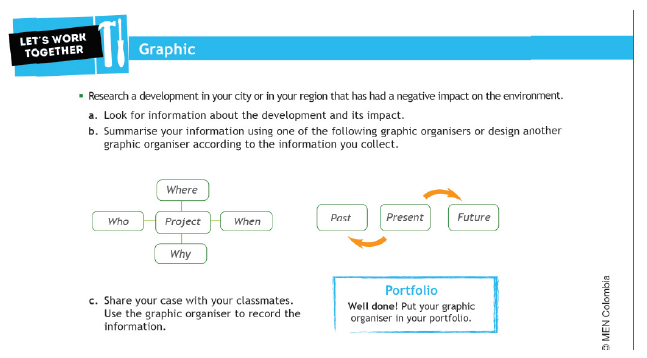

Let’s work together: These purple text boxes that are presented, next to a hammer and a screwdriver icon, are activities for learners to incorporate into their final projects. Every lesson has one.

Self-assessment: This closing activity presented on each module offers both, students and teachers, the possibility to make a reflection on the relative progress, or problems encountered in the module in the suggested individual or group activities. For that process, the authors of the series provide a format, which is included in the text.

Delimiting the samples

The teacher’s guides in the English, Please! series were selected for data collection and analysis. This decision was made after evaluating the material from the entire series, including the students’ books, the teacher’s guide, the audio CD and the online workbook. The teacher’s guides were deemed the most appropriate for evaluation, as they include an overview of the materials to be evaluated, including the table of contents, book covers, summary, dedication, introduction, title, references and more. This overview allows for a better content analysis (Cohen et al., 2007; Tomlinson, 2003). The teacher’s guide contains complete student’s activities, important information, explanations and answers for each activity in the series and recommendations for the teachers. This facilitate the categorization of the elements to be studied, and thus contribute to more refined data collection (McDonough & Shaw, 1993).

Data collection process

We first examined Lineamientos curriculares: Idiomas extranjeros (MEN, 1999) and Estándares básicos de competencia en lenguas extranjeras: Inglés (MEN, 2006), as these documents contain the curricular plans for English language education in basic, middle and high school in Colombia. This provided an overview of the relative importance of intercultural awareness in the curriculum before examining the number and type of activities meant to promote intercultural understanding in the English, Please! series.

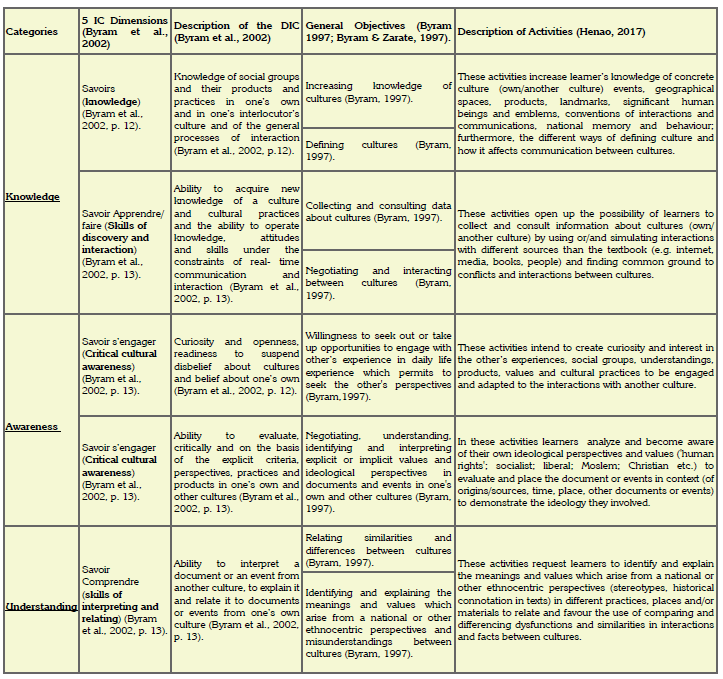

The criteria and instruments applied to the collection of data and the analysis of the activities in this study were aligned with the concepts and definitions that Byram presented in his seminal work Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence (1997), as well as in Developing the Intercultural Dimensions in Language Teaching: A Practical Introduction for Teachers (Byram, Gribkova & Starkey, 2002). The CEFR was also used as a point of reference, since Byram’s theories and concepts have already been incorporated into educational contexts (Council of Europe, 2001). We specifically targeted the key concepts of “knowledge, awareness and understanding” (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 103) which are developed later in this paper, as they contribute to the definition of the concept of intercultural awareness in the CEFR. These concepts support a wider view and appreciation of cultures, which is not limited to factual information, and data and statistical figures of the target language society. Rather, they are based on a progressive understanding of similarities and differences between local and foreign cultures, ideas and values, and the fostering of a respectful dialogue among language learners. With this background, we placed the activities of the modules in a table, and we examined, whether or not, they matched the definitions and descriptions of Byram et al. (2002); Byram (1997); Byram & Zarate (1997); Henao (2017). (Appendix 1).

A grid was also designed to streamline data collection. It contained the category of activity, the module, in which the activity appears, the number or letter assigned to the activity in the text and a brief description which explains why a particular task was classified as an intercultural awareness activity (see table 1).

Table 1: Activity Grid

Data analysis

After a closer look at Lineamientos curriculares (MEN, 1999) and Estándares básicos (MEN,2006), we found that these documents fail to mention key concepts related to intercultural awareness and still focus heavily in the four traditional basic linguistic skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing). This already shows an important gap in the English, Please! series.

The number of activities found in each textbook was then tallied, and this figure was compared with the activities labelled as intercultural awareness activities. In the three textbooks there were 1405 activities in total, but only 269 could be classified as intercultural awareness activities. The vast majority of these activities fall into the knowledge category (table 2).

Table 2: Intercultural Awareness Activities in English, Please!

Findings

Knowledge activities

Knowledge activities focus on acquiring new knowledge about culture or cultural practices. Out of 1405 activities only 209 fulfilled the criteria to be considered as conducive to intercultural knowledge (appendix 1). This is derived from what Byram (1997) proposed as the definitions, objectives and assessment of socio-cultural competence. For him, savoir apprendre/faire was aligned with the act of collecting and consulting data about cultures and the process of negotiation and interaction among learners, and his idea goes beyond the simple act of learning and memorizing facts for the construction of a knowledge base. Following, we provided a concise sample of those relevant activities.

The exercise named Food Poster represents a typical knowledge activity in the English, Please! series (figure 1). In this assignment learners are expected to find information about a traditional dish from around the world and to design a poster in which they can display their information.

Figure 1.: Knowledge activity: Food Poster

In a similar activity (figure 2), students must research information related to a traditional celebration or holiday, this time specifically in Colombia.

Figure 2: Knowledge activity: Presentation.

Finally, in the exercise named Graphic (figure 3), learners investigate a development in their own city or region that has had a negative impact on the environment. Although the activities aim at an increase of learning concrete culture, they fall short at the promotion of interactions with other sources beyond the book, internet, mass media, magazines, etcetera. Because, if we follow the lines of critical cultural awareness (Byram et al., 2002, p. 3), activities should be instrumental for students to analyse their own socio critical perspectives. These three activities are focused on what Byram et al. (2002) define as savoirs, and savoirs apprendre (see apendix 1).

Figure 3: Knowledge activity: Graphic.

Most of the knowledge activities in the English, Please! series focus on an incremental building of cultural knowledge through an exposure to specific cultural events (own culture vs. target language culture), geographical spaces, products, landmarks, significant human beings and national emblems. Activities are also focused on the conventions and interactions that affect communication with other cultures, specifically on cross-cultural communication among people from different backgrounds and nationalities. This type of activity relies heavily on the accumulation of learner’s knowledge of both explicit and implicit cultural norms. For the former, the designers of the series include observable behaviours, rituals, symbols, famous people, fashion, food, music, dance, special occasions, festivities and celebrations, physical spaces and landmarks, among others. The latter includes the underlying or unspoken values or norms of a culture which show people which behaviours are considered appropriate or inappropriate.

Awareness activities

An awareness of the similarities and differences between local and foreign cultures is another of the fundamental activities that produces intercultural awareness. As expressed by the CEFR:

It is, of course, important to note that intercultural awareness includes an awareness of regional and social diversity in both worlds. It is also enriched by awareness of a wider range of cultures than those carried by the learner’s L1 and L2. This wider awareness helps to place both in context. (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 103)

Awareness is defined by Byram et al. (2002) as intercultural attitudes (savoir être), or “curiosity and openness, readiness to suspend disbelief about cultures and belief about one’s own” (p. 12). Central to cultural awareness (savoir s’engager) is the “ability to evaluate critically, on the basis of the explicit criteria, perspectives, practices and products in one’s own and other cultures” (Byram et al., 2002, p. 13).

Awareness activities permit a differentiation between the world of origin and the world of the target community while raising awareness of the regional and social diversity in both worlds. Some awareness activities motivate learners by engaging them with practical activities. These activities were created with the intention of generating curiosity and interest in culture via exploring various social groups, cultural practices and the experiences of others. These activities are expected to help students to adapt and to be engaged more actively with other cultures. (Byram, 1997; Byram & Zarate, 1997).

In the following sample (figure 4) we can find a model on what Byram et al. (2002) define as savoir etre (attitudes) (see appendix 1). In the activity learners play the Ambassador Nomination game in which they are to take the role of ambassadors in different regions of Colombia. Although the activity encourages students to take up opportunities to engage with others’ events in daily life experience, and to seek the others’ perspectives, it is very basic and do not truly foster a critical perspective, and negotiation of meaning among students.

Figure 4: Ambassador Nomination game.

Some activities focus on the negotiation of meaning; that is, understanding, identifying and interpreting explicit or implicit values and ideological perspectives from both the learner’s culture and from other cultures. In these activities, learners analyze ideological perspectives, values and religious affiliations by evaluating a document or event in the context of its sources, time and place (Byram, 1997; Byram & Zarate, 1997). In the below activity (figure 5), learners are expected to become aware of and analyze their own ideological perspectives as they decide if the information they are given is morally or legally correct.

Figure 5: Interpreting ideological perspectives.

Awareness activities has the lowest count compared to other types of activities. This may be to the fact that awareness activities are more complex than knowledge activities, as they require more than just the collection of information. The creation of scenarios in the context of a given foreign culture places learners in a situation in which they must engage with the other culture by placing themselves in someone else’s shoes. It is expected that students become more sensitive to explicit and implicit values of the target language culture and ideological perspectives as they become interculturally aware learners.

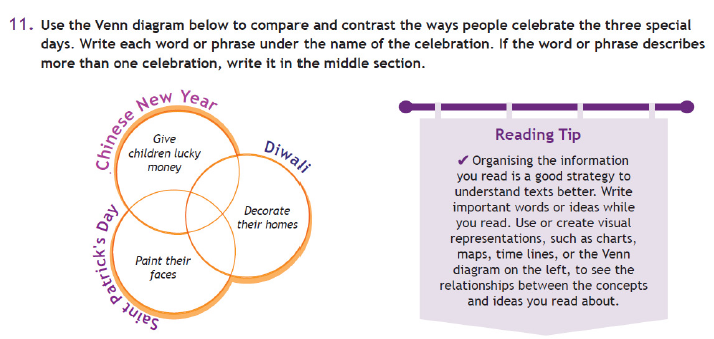

Understanding activities

Understanding activities represented 32 out of the 1405 analyzed activities in the English, Please! series (table 2). These activities focus on the skills of interpreting and relating events from another culture to the students’ own culture. This understanding can be fostered through the language skills of interpreting and relating (Byram et al., 2002). Cultural understanding (savoir comprendre) is defined by Byram et al. (2002) as “the ability to interpret a document or an event from another culture, to explain it and relate it to documents or events from one’s own culture” (p. 13) and is aimed at identifying and explaining the meanings and values arising from a national or other ethnocentric perspectives and misunderstandings among cultures. In the following sample (figure 6) students are challenged to interpret, compare and contrast celebrations using a Venn diagram.

Figure 6: Comparing celebrations.

Other understanding activities found in the English, Please! series included those which required learners to identify and explain the meanings and values arising from national or other ethnocentric perspectives (e.g. stereotypes, historical connotation in texts).

Analysis and discussion

At the beginning of this paper we stated that we would analyze the types of activities present in the English, Please! series and weigh their relative value in the promotion of intercultural awareness. For that purpose, we wanted to respond to the main research question and an accompanying sub-question, that is: what kinds of activities aim at the production of intercultural awareness in the English, Please! series? What percentage of the activities in the English, Please! series can be classified as intercultural awareness activities?

As stated above, we found that the English, Please! series has a total of 1405 activities. We classified these activities using a chart aimed at identifying activities which promote intercultural awareness (appendix 1). Our analysis was informed by the CEFR (2001), as well as the work of Byram (1997, 2002) . Out of the total number of activities, only 269 were identified as truly promoting intercultural awareness (19.15 %). 209 of these (14.88% of the total) were classified as knowledge activities. 28 (1.99% of the total) were awareness activities. Finally, 32 (2.28% of the total) were understanding activities. The vast majority of activities (1136 or 80.85%) were non-intercultural awareness activities. Although these activities were found to be helpful in the development of students’ lexical repertoire, and in the development of general language skills, most them do not contribute to the production of intercultural knowledge, awareness or understanding.

It is important to highlight and celebrate that the Colombia Very Well! 2015-2025 initiative has been the first national language policy which not only adopts the use of a language textbook, but contributes to a celebration of our cultural diversity. From that perspective, we value the relative progress in its approaches to foreign language education in Colombia. Interculturality has become a central concept that is integrated into the development of this set of instructional materials. The promotion of intercultural awareness, in this case among young learners, is in accordance with Eurocentric theoretical constructs and represents a possible avenue of bridging the gaps of social inequality in different social contexts, identities, ethnicities and communities. Intercultural awareness “will demolish a lot of communicational, physical and mental barriers for a better social and human understanding” (Council of Europe, 2001; MEN, 2014).

However, after running a content analysis, we have concluded that the English, Please! series entails a reductionist, instrumentalist and limited understanding of the concept. This claim is based on the fact that more than 80% of the activities do not develop intercultural awareness and among those which do, the majority regard only intercultural knowledge, that is to say, the factual, the visible, the tangible. Only a minor percentage - less than 4.5% - focus on intercultural awareness or understanding. Moreover, from a closer look to the typology of activities, it is evident that the major focus still is the practice of traditional language skills: speaking, listening, reading and writing. The traditional nature of these activities is camouflaged by titles such as Focus on Language, Self-Assessment, Improve Your English Pronunciation, Focus on Vocabulary, and Let’s Work Together, among others (MEN, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c).

Since the 80s, those who advocate for the improvement of the profession have been raising their voices for the need to integrate an intercultural component into curricular plans, especially when taking into account the multicultural and plurilingual richness and polyphony of our Colombia. Our teachers in general -and our language teachers in particular- would foster understanding and respect as they integrate real intercultural learning in their contexts. In a country like Colombia, during the newly announced peace agreements, classrooms could provide natural arenas for reflection and debates around issues on diversity, ethnic differences and similarities, inclusion and exclusion and 21st century global competence. Sharing each other’s views in an atmosphere of mutual respect can help in the healing of the social fabric, and the language classroom is an ideal discursive space to do so. The commitment to transform our students into intercultural human beings should not be seen as a utopian goal. Rather, it should be embedded in our official language policies as a positive movement towards the promotion of a better understanding, dialogue and relationships among the different communities in our nation.

Implications

This study has generated implications that would be of interest to policy-makers, academic consultants, textbook reviewers, social science researchers, language and cultural instructors, educators, textbook writers, assessors, cultural managers, anthropologists and sociologists. Some of these implications are discussed below. It should be stressed that the ideas presented are by no means exhaustive. They are, however, intended to stimulate thinking on how the insights from this study might impact, in a very broad way, the textual and contextual processes of intercultural communication on the Colombian society.

Theoretical implications

A major challenge when beginning this study was the absence of literature focused on the analysis of the concept of intercultural awareness in textbooks and ELT materials, so as Bonilla Medina (2008) points out, publishing houses have been interested in the concepts of culture and multiculturality. The present study shows the possibility of analyzing and assessing activities aimed at producing intercultural awareness through language textbooks. Another implication of this research study is that the criteria used for the analysis of activities can provide a rubric with which intercultural awareness activities in other textbooks and contexts can be interpreted.

Methodological implications

Although the research method used in study is not new, and all efforts were made to faithfully follow the eleven steps proposed by Cohen et al. (2007), it was adapted in innovative ways to improve and deepen the goals of this study. In particular, steps two through four -defining the population, deciding the sample and defining the environment- were combined with the methods for textbook and materials evaluation proposed by Tomlinson (2003). Furthermore, it was found that in defining the sample to undertake this study, the first step was to define the environment and the cause of the text; that is, to do steps two and four before step three.

Another important implication was the creation of categories and codes from the current literature that could fit not only the case of the English, Please! series, but also different language textbooks and broader studies. These variations of analysis allowed a more rigorous and reliable method in analysing a textbook than those presented by the aforementioned authors, as well as the creation of an instrument for analysing and filtering intercultural awareness activities in a broader way.

Practical implications

The present study has implications on the creation of activities aimed at producing intercultural awareness in a class, context, and classroom materials, teachers, book designers, and other experts on the production of materials face multiple challenges to reconciliate and interpret national mandated regulations, language policies, national identity, when designing textbooks and ancillary materials for the teaching of English as a foreign language. Today, more meaningful material should promote a development of intercultural awareness. In other words, materials that give students or learners the chance of going beyond factual information, and open up spaces for cultural sensitivity. Students should be given the chance to reflect first in their own identity, so they can be empowered to engaged in the process of negotiation of cultural understanding.

References

Appendix 1

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.