DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.93Published:

2010-01-01Issue:

Vol 12, No 1 (2010) January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesPeer editing: a strategic source in EFL students’ writing process

Corrección entre pares: una herramienta estratégica en el proceso de escritura de los estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera

Keywords:

Edición entre pares, proceso de escritura en EFL, scaffolding, revisión, pensamiento, relaciones (es).Keywords:

peer editing, writing process in EFL, scaffolding, revising, thinking, relationships (en).Downloads

References

Abbot, P., & Amato, R., (1993). Making It Happen. Interaction in the Second Language Classroom. New York & London: Longman.

Agenda Escolar. (2008). Colegio Externado Nacional Camilo Torres IED.

Arhar, J. (2004). Action Research for Teachers: Traveling the Yellow Brick Road. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Burns, A. (2001). Collaborative Action Research for English Language Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Guerrero, M. & Villamil, O. (1994). Socio-cultural theory: A framework for understanding the social-cognitive dimensions of peer feedback. In Feedback in Second Language Writing. Hyland & Hyland (2006) New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dijk, Teun A. (2000).Theoretical Background, in Ruth Wodak and Teun A. van Dijk (eds), Racism at the Top. Parliamentary Discourses on Ethnic Issues in Six European States, Klagenfurt: Drava Verlag, 2000, pp. 13-30.

Fosnot, C.(1996). Constructivism: A psychological theory of learning. In Constructivism: theory, perspectives and practice. Ed. C.T Fosnot-8-33. New York.

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing Teacher Research: From Inquiry to Understanding. Canada: Heinle and Heinle Publishers.

Goalty, A. (2005). An introductory course book of critical reading and writing. Routledge: London and New York: Taylor and Francis group.

Merriam, S.B. (1988). Case Study Research in Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publications.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language Learning Strategies. What every teacher should know. The university of Alabama. A division of Wadsworth, inc Boston, Masachusets. Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Piaget, J. (1972). Psychology and Epistemology: Towards a Theory of Knowledge. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Punch, (1994). Politics and ethics in qualitative research. In N.K. Denzin & Y. Lincon (Eds). Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 83-97). New York.Sage Publications.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research; Grounded Theory, procedures and techniques. London: Sage Publications.

Vigotsky, L.S (1978). Mind in Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wertsch, J & Stone, C (1978). Microgenesis as a tool for development analysis. Quaterly Newsletter laboratory of comparative human cognition, 1-8-10.

White, R. and Arndt, V. (1996). Process Writing. London and New York: Longman Group.

Wood, D.,Bruner, J.S.,& Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of psychology and psychiatry. 17, 89-100.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2010 vol:12 nro:1 pág:85-98

Editorial

Peer editing: a strategic source in EFL students’ writing process

Corrección entre pares: una herramienta estratégica en el proceso de escritura de los estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera

Nubia Mercedes Díaz Galvis

English Teacher at Externado Nacional Camilo Torres Bogotá, Colombia E-mail:nubiadg@gmail.com

Abstract

This article reports on a research project focused on peer editing as a pedagogical tool to promote collaborative assessment in the EFL writing process. With teachers overstretched in the Bogotá public school system, a method needed to be found that would allow students to receive much needed feedback without overtaxing the teachers` resources. Peer editing, a phenomenon that often occurs naturally within the classroom, was therefore systematically implemented as a solution to the stated problem. The main aims of this study, conducted with a group of ninth grade student at a public school in Bogotá, were to determine the role of peer editing in the writing process and to characterize the relationships built when students corrected each others writings. The instruments used for collecting data were field notes, video recordings and students’ artifacts. The results showed that when students were engaged in peer editing sessions they created zones of proximal development in which high achiever students provided linguistic scaffolding and empowered low achievers. It was also found that students used thinking strategies such as noticing and explaining when they identified errors related to the formal aspects of the language.

Key words: peer editing, writing process in EFL, scaffolding, revising, thinking, relationships.

Resumen

Este artículo reporta un proyecto de investigación que se centró en corrección entre pares como una herramienta pedagógica para promover la evaluación y colaboración durante el proceso de escritura en EFL. La sobrecarga de tareas y el número de estudiantes que tienen los docentes en las escuelas públicas de Bogotá dificulta la tarea de acompañamiento y de retroalimentación de los docentes en el proceso de escritura de sus estudiantes. La corrección entre pares, un fenómeno que ocurre de manera natural en el aula de clase, se implementó como una posible solución al problema de desarrollo de escritura mencionado. El propósito principal de este estudio con estudiantes de noveno grado en una escuela pública de Bogota fue determinar el rol de la corrección entre pares en el proceso de escritura y caracterizar las relaciones que se construyen entre ellos cuando se corrigen los escritos unos a otros. Los instrumentos utilizados para la recopilación de datos fueron notas de campo, grabaciones de video y las producciones escritas de los estudiantes. Los resultados mostraron que cuando los estudiantes fueron partícipes en pares de edición crearon zonas de desarrollo próximas en las cuales los alumnos de alto desempeño ayudaron a los alumnos de bajo desempeño. También se encontró que los estudiantes utilizaron estrategias de pensamiento cuando identificaron errores relacionados con los aspectos formales de la lengua.

Palabras clave: Edición entre pares, proceso de escritura en EFL, scaffolding, revisión, pensamiento, relaciones.

Introduction

This qualitative research was developed to gain insight into the impact of peer editing on students’ writing and interactions in a ninth grade EFL classroom. With teachers overextended in the public sector in Bogotá, a method needed to be developed for giving students feedback and corrections that they needed without overwhelming the teachers´ resources. Peer editing optimizes classroom time, allowing students to learn both from the revisions they receive and also from the process of revising others´ work.

In addition, in EFL writing courses, students often look to each other for help. Peers may be seen as less intimidating than working directly with the adult teacher. Low achieving students in particular tend to seek out higher achieving students as a way to improve their writing assignment and better understand the material. Peer editing allows for a natural extension of what is already happening in the classroom. Thus, peer learning could become an important tool to provide assistance and a new form of assessment during the EFL writing process in a collaborative classroom environment.

For the purpose of this research writing is defined as a recursive process involving subprocesses such as generating ideas, drafting, revising, editing and error correction ( White & Arndt, 1996). Peer editing is included as a tool that helps students assess their own writing assignments.

In this study the support of an expert guiding the learner through the Zone of Proximal Development or ZPD (Vigotsky, 1978) and the opportunities for students to see how others respond to their work and learn from these responses are explored. In this project peer commentary is a to learners’ growth. Thus, it can contribute to illuminating and explaining the social cognitive dimensions of foreign language writing development. Within this framework aspects such as patterns of social interaction, scaffolding and EFL writing process development are presented to explain the empowerment of students through the peer editing sessions.

Theoretical perspectives

In this section, key theoretical concepts that support the study of peer editing with EFL students are presented by firstly describing the social relationships that supported the process of peer editing among EFL learners, then through theoretical insights about writing as a process, and finally through peer editing and scaffolding as strategic techniques used by students to construct a written text in English.

Building relationships when peer editing

From the point of view of the social constructivism model, the learner plays a central role and the dynamic of exchange between teachers, learners and tasks and provides a view of learning as arising from interactions with others. As pointed out by the followers of Vykotsky’s principles, learning always happen in a community. Any individual can reach higher developmental stages if at least she is surrounded by a group of people with whom she interacts and at the same time that help her to scaffold her learning process which takes place and through the interactions and relationships that occur between learners.

In this environment the learner must develop competence, and the ability to manage exchanges despite limited language development. Personality, motivation, and cognitive style may all play a role in influencing the learner’s willingness to take risks, openness to social interaction and attitudes towards the target language and users of it. Additionally, students develop socio-affective strategies that deal with social-mediating activity and transaction with others. These strategies involve asking questions, cooperating with others and empathizing with others (Oxford, 1990).

Goalty (2005) suggests that interpersonal relationships can be analyzed along the dimensions of power, contact and emotion. First, power might be defined in terms of physical strength or force; or the authority given to a person by an institution, such as the vice chancellor of a university; or status, which depends on wealth, education, place of residence; or expertise, the possession of knowledge or skill whose dynamic occurs in an EFL classroom.

Second, with regard to contact, Goalty (2005) claims that we will communicate with some people more often than others, becoming more familiar to some than others. In the classroom, some peers have more contact with other students and share more than others. The third dimension is emotion or affect; in some relationships we are unlikely to express emotion at all. If we do express it, emotion can be positive or negative, fleeting or permanent. Thus, interpersonal relationships depend on contact, power and the kind of emotion expressed.

Writing as Process and Cognition

The process approach emphasizes the notion of writing as a process whereby the finished product emerges after a series of drafts. Composing a text usually goes through several rounds of peer edits and self- assessment before it reaches the teacher for assessment.

The study focuses on the conception of writing as process as defined by White and Arndt (1996). They suggest that procedural activities to perform the writing process. The authors state that writing is a thinking process in its own right. It demands conscious intellectual effort, which usually has to be sustained over a considerable period of time. The authors also argue that writing is a form of problem solving which involves diverse processes. They present six general activities in the process of writing: generating (brainstorming, using questions, making notes, and using visuals), focusing (discovering main ideas, considering purpose, considering audience, considering form), structuring ( ordering information, experimenting with arrangements, relating structure to focal idea), drafting ( beginning, adding and ending information), evaluating ( assessing the draft, responding and conferencing), and reviewing (checking, editing, correcting and marking).

For this study the model has been reduced to four stages: planning, drafting, revising and editing. In addition, re-writing has been included as an important stage to be used with the students. Drafting was utilized which consists of a series of strategies undertaken to organize and support a piece of writing. In the first stage of the process students concentrated on structure, organization, argumentation and content. In the next stage, revising, they reevaluated the choices to produce a stronger piece of writing.

In relation to revising and thinking, Oxford (1990) states that meta-cognitive strategies allow learners to control their cognition; that is, to coordinate the learning process by using functions such as centering, arranging, planning and evaluating. Thus, when revising, students think, write, read, discuss, notice, question and discover in every editing session. Revising, therefore, involves evaluating what has been written and making deletions or additions as necessary to help the writer say what he intends to say. In revising, students think through content, state ideas in their own words, and plan their sentence constructions. Finally, re-writing incorporates the feedback given by peers and in some cases, by the teacher.

Defining peer editing

A key component of the writing process is the peer editing. In this process students read each other’s papers and provide feedback to each other. Also, students face new roles as authors and collaborators. This activity creates further opportunities for the students to work together constructively and develop their collaborative skills. Furthermore, peer response shows that readership does not belong exclusively to the teacher, since in this type of response, students share their writings with each other. Though at the beginning of any peer editing practice students need the teacher’s encouragement, they gradually get used to the idea of communicating their ideas to one another. In this project, revising occurred throughout the composing process. Peer editing engaged students in a series of cognitive processes, such as reflection, analysis, and reviewing.

One of the most important questions regarding peer editing is what do students actually do when asked to review a peer’s writing? In order to explore this question the research conducted by De Guerrero and Villamil (1994) examined the social-cognitive dimensions of interactive peer revision from a Vigotskyan perspective. In regard to cognitive stages of regulation during peer revision sessions, they categorize students as object-related (the learner is guided by a peer), and self- regulated (the learner is capable of independent problem solving and responds quickly and efficiently to suggestion). The researchers found that leadership, self-assurance, and willingness to share knowledge were the characteristics of the peer interaction. This study provides an insight into the complexity of student relationships during peer review sessions. In the following section, peer editing is explored as a genuine way of learning from a social constructivist point of view.

Socio-cognitive constructivism in learning

The main two approaches to constructivism are cognitive and social constructivism. The former is associated with the work of Piaget and the latter with that of Vygotsky. The two approaches are not mutually exclusive, as underpinning both is the belief that students learn by constructing their own knowledge. Social constructivists focus on the key role played by the environment and the interaction between learners. This project involves the conception of collaborative work and learning together. As Piaget (1972) pointed out, collaborative learning has a major role in constructive cognitive development. His theory is consistent with the other popular learning theories (Vygotsky, 1978) in emphasizing the importance of collaboration. Piaget affirms that interaction between peers is equally shared.

Vygotsky focused on the effect of social interaction on learning, yet in no way did he deny the cognitive role (Fosnot, 1996). Moreover, Vykotsky argued that the social, interpersonal aspects of learning precede the individual, interpersonal aspects. He emphasized the social origin of cognition and the effect of social interaction on learning. The study was based on these theoretical perspectives because it involves all dimensions of learning, both cognitive and social. What is more, a social constructivist perspective conceives writing as a way of creating meaning through words, sentences and paragraphs, besides a tool to promote knowledge and learning in all academic disciplines.

Social-interaction and constructivism theories consider that children are born into a social world therefore learning occurs through interaction with other people, and through these interactions people make sense of the world. For the purpose of this study Vykotsky’s concepts of Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and scaffolding (1978) are adopted. The concept of ZPD is based on peer learning, collaborative classrooms and how these two concepts promote the construction of knowledge. Writing is not a solitary act (Ong, 1982) but rather is the result of interaction among people, context and texts.

In other words, writing occurs in a community for a community. Scaffolding The concept of scaffolding, which derives from cognitive psychology and L1 research, states that in social interaction a knowledgeable participant can create, by means of speech, supportive conditions in which the novice can participate, and extend current skills and knowledge to higher levels of competence (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976). According to Wood, Bruner and Ross, scaffolding help is characterized by the following six features: recruiting interest in the task, simplifying the task, maintaining pursuit of the goal, marking critical features and discrepancies between what has been produced and the ideal solution, controlling frustration during problem solving, and demonstrating an idealized version of the act to be performed. This study of peer editing rests on the idea that learner interaction is developmental to the extent that it seeks to uncover the mutual effects of learners on each other’s inter-language system. As defined by Wertsch and Stone (1978), micro-genesis refers to the gradual course of skill acquisition during a training session, experiment, or interaction. Thus, this research allowed the teacher to observe directly how students help each other during the writing process and how in this process they come into contact, and interact, with each other. The power of this collaborative experience has support in the developmental theory of Vygotsky (1978), which maintains that when learners are actively assisted in dialogic events on topics of mutual interest and value, individual and conceptual development occurs. In this section peer editing is framed within the theory of writing as process and cognition and the socio–cognitive model of learning, which includes scaffolding techniques. Additionally, the kinds of relationships that students could build in an EFL classroom are defined. Therefore, I will describe the research design which includes the type of study, setting, participants and the instruments and procedures for data collection and analysis. Finally, I will present the findings of this research. Methodology This study can be categorized as qualitative and descriptive-interpretative as it describes a phenomenon under study (Merriam, 1998) meaning that descriptive data about the students´ performance when they were engaged in writing and peer editing processes was included. However, not only were observations described, but also the actions, phrases and behaviors of the students when engaged in the writing process and peer editing sessions were analyzed and interpreted. Finally, inductive analysis and grounded theory were taken into account because the qualitative researchers mainly work on generating theory from data. The theory is grounded in the social activity it sets out to explain. Based on this research paradigm two questions are proposed for this study:- How does peer editing influence ninth grade students’ writing in the context of an EFL class in a public school?

- What type of relationships do ninth grade students from a public school build during the peer editing process?

In order to answer the above research questions, a curricular unit named “experiences” was implemented consisting of pre- writing, writing and re-writing stages. The peer editing process was included in these stages.

Context

This study was carried out at a public school located in the downtown area of Bogotá. The school is co-educational with 1300 students. It has a mandatory curriculum for 6th to 9th grades. The pedagogic approach of the school rests on the principles of meaningful learning, based on the socio- cognitive perspectives of learning. These two aspects were developed in the peerediting and the writing process. In addition, the methodological approach of the institution tries to privilege writing in order to build sense and meaning and to promote human relations across all the subjects (Agenda Escolar, 2008).

From 6th to 9th grade, students have three hours of English per week, each class lasting 47 minutes. Students do not have a textbook for the English classes, so the teachers prepare workshops and the materials for the class activities. Therefore, teachers have the duty and opportunity to design their English program according to their own criteria. In relation to the curriculum, the linguistic, pragmatic and sociocultural competences are the most relevant criteria for designing the English program.

Participants

At the beginning of this project 38 ninth graders from various zones of Bogota were involved, 20 boys and 18 girls who were between the ages of 13 and 16. During the research process, six students, two girls and four boys, dropped out of school for economic reasons. The group was selected because I had had the chance to work with them in the writing process before and I was their homeroom teacher. Thus, this fact gave me the opportunity to have more contact and a closer relationship with the students, and to create a good atmosphere for learning when implementing the peer editing and writing process. Additionally, ninth grade is the last level in which foreign language is a mandatory part of the basic education curriculum.

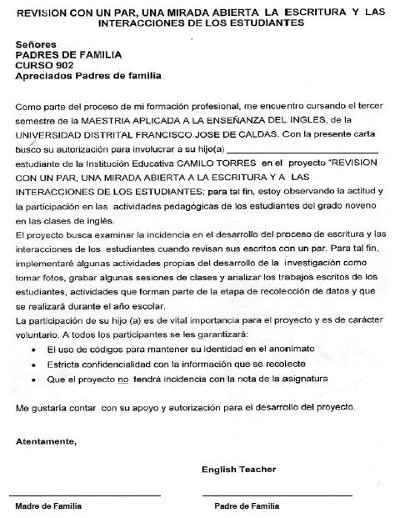

At the beginning students were surveyed using a written exercise whose results gave insight into the students’ attitudes toward English, their writing level and the topics about which they preferred to write. This group of students provided the opportunity to become familiar with the most common problems and experiences that adolescents face and the research project was a chance to discover their interests, needs and motivation when they write. Permission to gather information about the children was requested from all the students’ parents. They signed a consent form (see Appendix 1) and in order to protect the privacy and identity of the participants, all participants are kept anonymous (Punch, 1994).

Data Sources

Both written data and interaction observation were documented using three instruments: field notes, video recording and students’ artifacts.

a. Field notes

Burns (2001) describes field notes as detailed descriptions and interpretations of an event or process phenomenon. Details of the writing process and the social relationships during peer editing sessions were recorded. Field notes include who is being observed and the context of the observation.

b. Video recording

This instrument provided objective records of what occurred, which could be examined. As the author states, a video recording captures both verbal and non-verbal interaction in an activity or lesson. Besides, videos are excellent for observing the teacher interacting with students. I also took photographs as Freeman (1998) recommends.

c. Students’ artifacts (writing drafts)Pieces of students’ written compositions were useful tools for analyzing the ways in which students developed their writing process. Arhar (2004) states that saving samples of work produced over time may be useful. In this case, written compositions from my students to check the students’ writing process.

Findings

Analysis was based on the grounded theory. According to Strauss and Corbin (1990), this is a general methodology for developing theory in which the researcher is surfacing themes and concepts from the data as he or she reads them. The three basic elements of the grounded theory are concepts, categories and propositions. In relation to this project, the aim of the grounded theory was to understand and explain the meaning of the experience and behavior shown by participants when they were involved in peer editing sessions.

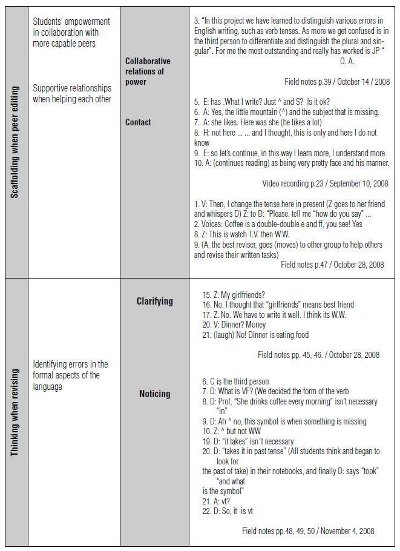

Table 1 shows the categories and their corresponding sub-categories. They account for the process of scaffolding when peer editing and the relationships students built during this process. It also illustrates the way students identified errors in formal aspects of the language using the correction symbols. They are supported with excerpts taken from the instruments that gathered the data from different sessions carried out by the participants throughout the project.

Scaffolding when peer editing

To illustrate the concept of scaffolding in this research project, I addressed the cognitive development that occurs at the moment of social interaction (Abbot & Amato 1993). From the data I identified that in peer editing, some high achievers facilitated the students’ transition from assisted to independent performance. From a Vigotskyan perspective, the child’s cognitive or problem- solving activity is first socially regulated by the adult in joint interaction; in the case of this research, the peer became the adult.

Students’ empowerment in collaboration with more capable peers

This subcategory addresses the help of a ‘more knowledgeable other’ (MKO) adult or peer, when students corrected each other’s written texts. She shared her knowledge with less capable peers to bridge the gap between what is known and what is not known. Once the student has expanded her knowledge, the actual developmental level has been expanded and the ZPD has shifted. The ZPD is always changing as the student expands and gains knowledge, therefore scaffolded instruction must constantly be individualized to address the changing ZPD of each student. This fact was evidenced when students worked together and showed progress in the ZPD.

As happens in the ZPD, students felt motivated in helping others and achieving tasks together. In the excerpt, when student O.A. said, “for me the most outstanding and really has worked is J.P.” In this sentence, the student talked about the progress of his peers in terms of writing development.

Additionally, the following excerpt showed the relationship between the novice (P) and the expert (A) as the novice moves upwards through his ZPD to a higher performance level. The example shows how the learner internalizes the information and becomes a self-regulated, growing independent learner.

In the sample found below students were exploring new vocabulary in a pre-writing activity for describing physical appearance.

- A: Teacher Don’t worry, we are working

- together

- A to P: Write that you are fourteen years

- old (Teacher hugs P and he smiles)

- A: He (P: Plazas) is able to do sentences

- without help.

Video-recording p.19, 20 / September 3, 2008

The above example is related to the process of self-regulation. In line 3 “he is building sentences by himself”, the student (P) began to mastering the task, the teacher or in the case of this project, the peer, begins the process of “fading”, or the gradual removal of scaffolding (Wood, Bruner & Ross, 1976).

Supportive relationships when helping each other collaborative relations of power

The data revealed that the relations of power in the classroom were related to the possession of knowledge or of a skill. Thus, this subcategory was named as collaborative relations of power. This kind of relationship operates on the assumption that power is not a fixed predetermined quantity but rather can be generated by interpersonal and intergroup relations (Van Dijk, 2000). In other words, participants in the relationship are empowered in terms of knowledge through their collaboration such that each is more affirmed in his or her identity and has a greater sense of efficacy to create change in his or her knowledge. Thus, power is generated in the relationship and shared among participants. The power relationships that students built were additive rather than subtractive because power, as in this research project is related to knowledge, is built with others rather than being imposed or exercised over others (see excerpt, table 1). It shows the guiding role of the reviser who had the knowledge when helping the other who did not have it but wished to do so.

Contact

In this research project students established caring and supportive relationships connecting at a personal level by not only transmitting knowledge but also establishing contact with each other. Through video observations, this kind of relationship was mainly found in student teams who already had a close relationship. Goalty (2005) stated that all relationships imply connections; we are connected to others by virtue of shared experiences, interpretations, perceptions and goals. When students worked together, some students showed the feelings of attachment to others.

I noticed the interpersonal engagement among students and named it friendship. This type of relationship usually includes higher levels of intimacy, self-disclosure, and involvement. Friends interact more frequently and they talk to each other more often. The increased frequency of interaction means that friends will have more knowledge about and shared experiences with each other. Friends communicated through nonverbal language, whispering and by increasing body contact. It was evident when students sat together, moved around the classroom to look for information and formed new teams to help their classmates. Additionally, facial expressions such as laughing, sending kisses to the camera (when recording), covering their faces with their hands and even drawing on their fingers creating new links and different ways of communicating among themselves were observed.

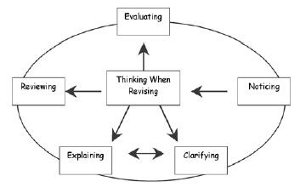

Thinking when revising

This category explains the connection between the process of identifying errors and the thinking strategies (meta-cognitive) that students used in the revision stage (Oxford, 1990). Meta-cognitive strategies are used in information processing theory to indicate an executive function; they involve planning for learning, thinking about the learning process, the monitoring of one’s comprehension or production and evaluating learning after the completion of an activity.

When revising, students were engaged in a series of cognitive processes in which they were required to transform the ideas, experiences and thoughts into written assignments; parallel to this, they were involved in a discovery process of revision and identification of errors in the formal aspects of the language. This implied asking the students to construct knowledge through analysis, synthesis and interpretation. This process showed the importance of meta-cognitive thinking when becoming a better writer.

In the current body of literature regarding learning strategies used in the revision process, I did not find one author who groups the strategies that the students used when they discovered errors. Thus, I designed the following diagram that explains the strategies that students used when they were engaged in the peer editing process.

As Vigotsky (1978) asserts, everything we learn involves imperfection and error as we gain competence and support for “mistake making” and hypothesis testing. Teachers and peers must balance invention and convention.

When students identified errors they incorporated inquiry strategies (collecting and evaluating evidence, comparing and contrasting cases to infer similarities and differences, explaining how evidence supports or does not support a claim, creating a hypothetical example to clarify an idea, imagining a situation from a perspective other than one’s own, and so on).The cognitive process involved in revision, such as decoding words, applying grammar knowledge, et cetera, were developed when students were engaged in the peer revision process.

Among these strategies noticing is the most common one used when students revised their partners’ work as, while doing so, they developed increased competence in identifying mistakes. When editing students thought, wrote, read, discussed, noticed, questioned, and discovered. When students noticed they built pathways, made connections and discovered a way of thinking about the mechanics of writing in English which reflected a thinking process. This process also enhances other skills, most notably the ability of explaining, which implies a higher-level reasoning, a deeper level of understanding and both long term retention and clarifying meaning. While revising students looked closely, explained their understanding and expanded their thinking about the patterns and concepts found in their written productions. In this process of revising, students used their previous knowledge to construct a new one in collaboration with their peers. In the revision and discovery process, the students identified issues related to formal aspects of language. The errors students mostly identified were related to verb tenses/forms, and subject verb agreement as well as singular, plural and word omission. In addition, the students identified grammar, sentence structure, punctuation and spelling mistakes.

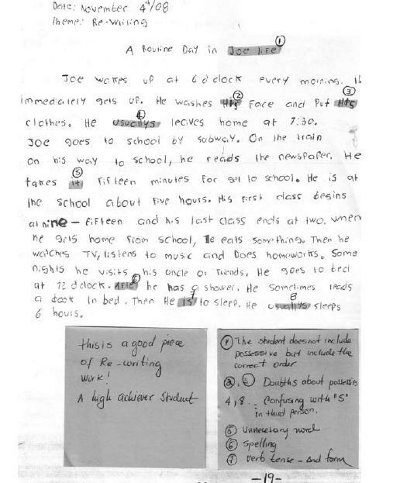

In this research data was taken from students’ artifacts and reflections related to their perceptions about writing and the peer editing process in order to support the findings further. The following excerpts show how students increase awareness of certain linguistic aspects such as grammar, spelling, punctuation, diction, sentence structure and accuracy while editing their peers’ work as in the excerpt shown above. During the development of the peer-editing sessions, writing emerged as a meaningful activity as students could see that correction was not done for its own sake but as part of the process of making communication as clear and unambiguous as possible to an audience.

The following piece of written production was taken from a re-writing exercise.

The artifacts exemplify that most of the students focused on errors in verb tenses. Moreover, the data showed that students identified errors in missing subjects, misuse of third person in simple present tense and spelling mistakes. Written perceptions of the students confirm the analysis provided.

“I had been corrected by A because sometimes I put the words in an incorrect place. Also when I forgot to write the verb in third person. I also corrected others in conjugate verbs and their tenses. I have also corrected to A and K, D, E, but more importantly I have learned corrected them because there are times when one has no reason at all, for example in the tense of the sentences. My peers have corrected me and also we learn when we see to correct.” Student artifact, October 31, 2008

In the above piece of writing the student acknowledged that peer editing produced reciprocal knowledge. This conviction is connected to Vigotskyan theory which argues that individual knowledge is socially and dialogically derived and can be observed directly in the interaction among the individuals during problem solving tasks.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the effect of the peer-editing activities on the writing process. The focus of this research project was not only on the writing process but also on the social relationships that students built and how they interacted in the classroom during the peerediting sessions. The results of this research reveal that peer editing entails a socio cognitive perspective, as stated by Vigotskyan theorists.

The students used learning strategies when they revised their partners’ written papers. In this sense, peer editing became a cognitive tool. The participants in this study reported using metacognitive and social strategies (Oxford 1990) when they were involved in the peer editing project. The former were mainly evaluating, noticing and reviewing which was evidenced when the students explained and clarified to others. The data analysis of the lessons revealed that the feedback provided by peers helped students to notice and correct their mistakes related to the formal aspects of the language. The above findings responded to the first research question which refers to the role of peer editing in students’ writing process.

In terms of the social strategies, when students interacted with each other, which was the topic of the second research question, the implications of using collaborative assessment in the English language class was explored. Social interaction, therefore, is a mechanism for individual development, since during problem solving the experienced student guided, supported, and shaped actions of the novice who, in turn, internalized the expert’s strategic processes. The results and the theoretical framework both support the benefits of working on peer editing because students learn more when they are engaged actively during an instructional task while interacting with other learners.

Pedagogical Discussion

First, peer editing as a useful strategy in collaborative classrooms provides teachers with valuable opportunities to make significant changes in their practices and perspectives on teaching and learning and different ways of assessing our students. As a Colombian public school teacher, my contribution in implementing this research project is mainly about the demands and the conditions of today’s students who require teachers that transform traditional methodologies to provide opportunities for new ways of learning. The implications of this project propose peer editing as a bridge between the writing process and collaborative learning.

As a teacher I gained important insight into what collaborative learning is, particularly through understanding that the condition for learning in a ZPD is the capacity to make use of help and the capacity to benefit from give-andtake in experiences and conversations with others (Bruner, 1962). In peer editing, learning is seen as a dynamic process in which learners themselves are actively involved, in which implementing cooperative work promotes discussion and sharing of ideas among students.

References

Abbot, P., & Amato, R., (1993). Making It Happen. Interaction in the Second Language Classroom. New York & London: Longman.

Agenda Escolar. (2008). Colegio Externado Nacional Camilo Torres IED.

Arhar, J. (2004). Action Research for Teachers: Traveling the Yellow Brick Road. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Burns, A. (2001). Collaborative Action Research for English Language Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Guerrero, M. & Villamil, O. (1994). Socio-cultural theory: A framework for understanding the socialcognitive dimensions of peer feedback. In Feedback in Second Language Writing. Hyland & Hyland (2006) New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dijk, Teun A. (2000).Theoretical Background, in Ruth Wodak and Teun A. van Dijk (eds), Racism at the Top. Parliamentary Discourses on Ethnic Issues in Six European States, Klagenfurt: Drava Verlag, 2000, pp. 13-30.

Fosnot, C.(1996). Constructivism: A psychological theory of learning. In Constructivism: theory, perspectives and practice. Ed. C.T Fosnot-8-33. New York.

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing Teacher Research: From Inquiry to Understanding. Canada: Heinle and Heinle Publishers.

Goalty, A. (2005). An introductory course book of critical reading and writing. Routledge: London and New York: Taylor and Francis group.

Merriam, S.B. (1988). Case Study Research in Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publications.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language Learning Strategies. What every teacher should know. The university of Alabama. A division of Wadsworth, inc Boston, Masachusets. Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Piaget, J. (1972). Psychology and Epistemology: Towards a Theory of Knowledge. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Punch, (1994). Politics and ethics in qualitative research. In N.K. Denzin & Y. Lincon (Eds). Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 83-97). New York.Sage Publications.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research; Grounded Theory, procedures and techniques. London: Sage Publications.

Vigotsky, L.S (1978). Mind in Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wertsch, J & Stone, C (1978). Microgenesis as a tool for development analysis. Quaterly Newsletter laboratory of comparative human cognition, 1-8-10.

White, R. and Arndt, V. (1996). Process Writing. London and New York: Longman Group.

Wood, D.,Bruner, J.S.,& Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of psychology and psychiatry. 17, 89-100.

Apéndice 1

STUDENTS‘ CONSENT FORM I.E.D COLEGIO EXTERNADO NACIONAL CAMILO TORRES

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.