DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a07Publicado:

2015-10-23Número:

Vol 17, No 2 (2015) July-DecemberSección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónAction research processes in a foreign language teaching program: voices from inside

Procesos de investigación acción en un programa de formación de docentes de lengua extranjera: voces desde dentro

Palabras clave:

investigación acción, práctica académica, estudio de caso (es).Palabras clave:

action research, case study, teaching practicum (en).Descargas

Referencias

Arias, C. (Ed.). (2007). Seminario: Asesoría de Práctica Docente Investigativa en Lenguas Extranjeras/ Lecturas. Medellín, Universidad de Antioquia.

Cadavid, C., Quinchía, D. & Díaz, C. (2009). Una propuesta holística de desarrollo profesional para maestros de inglés de la básica primaria. Ikala 14 (21), 135-158.

Cadavid, C., Díaz, C. & Quinchía, D. (2011). When Theory Meets Practice: Applying Cambourne’s Conditions for Learning to Professional Development for Elementary School EFL Teachers. Profile 13 (1), 175-187.

Cambourne, B., Kiggins, J. & Ferry, B. (2003). The Knowledge Building Community Odissey: Reflections on the journey. Change: Transformations in Education. 6 (2),57- 66. Retrieved from http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/4501/1/Vol6No2Article5.pdf

Cárdenas, M. (2004). Las investigaciones de los docentes de inglés en un programa de formación permanente. Ikala 9 (15), 105-137.

Cárdenas, R. & Faustino, C. (2003). Developing Reflective and Investigative Skills in Teacher Preparation Programs: The Design and Implementation of the Classroom Research Component at the Foreign Language Program of Universidad del Valle. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal 5, 22-48.

Carr, W. & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming Critical: Education, Knowledge, and Action Research. London, UK: RoutledgeFarmer.

Cochran-Smith, M. & Lytle, S. (1993). Inside Outside: Teacher Research and Knowledge. New York, N.Y: Teachers College Press.

Cochran-Smith, M. & Lytle, S. (1998). Teacher Research: The Question that Persists. International Journal of Leadership in Education: Theory and Practice 1 (1), 19-36.

Cochran-Smith, M. & Lytle, S. (1999). Relationships of Knowledge and Practice: Learning in Communities. Review of Research in Education 24, 249-305.

Creswell, J. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. (2nd Ed.) Thousands Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Desimone, L. (2009). Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Towards Better Conceptualization and Measures. Educational Researcher 38 (3),

Flores-Kastanis, E., Montoya-Vargas, J. & Suárez, D. (2009). Participatory Action Research in Latin American Education: A Road Map to a Different Part of the World. In S. Noffke & B. Somekh. (Eds). The SAGE Handbook of Educational Action Research. (pp. 454-466). London, UK: Sage Publications, ltd.

Glesne, C. (2011). Becoming Qualitative Researchers: An Introduction, (4th. Ed.) Boston, MA: Pearson.

González, A. (2003). Who Is Educating EFL Teachers: A Qualitative Study of In-service in Colombia. Ikala 8 (14), 153-172.

González, A. (2009). On Alternative and Additional Certifications in English Language Teaching: The Case of Colombian EFL Teachers’ Professional Development. Ikala 14 (22), 183-209.

Hancock, D. & Algozzine, B. (2006). Doing Case Study Research. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Hoban, G. (Ed.). (2005). The Missing Link in Teacher Education Design: Developing a Multi-linked Conceptual Framework. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

Jerez, S. (2008). Teachers’ Attitudes towards Reflective Teaching: Evidences in a Professional Development Program (PDP). Profile 10, 91-111.

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R. & Nixon, R. (2014). The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action Research. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

López, M. & Viáfara, J. (2007). Looking at Cooperative Learning through the Eyes of Public Schools Teachers Participating in a Teacher Development Program. Profile 8, 103-120.

McNiff, J. Whitehead, J. (2006), Action Research: All You Need to Know About. Thousands Oaks, CA: SAGE.

McNulty, M. & Quinchía, D. (2007). Design a Holistic Professional Development Program for Elementary School English Teachers in Colombia. Profile 8, 131-43.

Noffke, S. (1994). Action Research: Towards the Next Generation. Educational Action Research 2 (1), 9-21.

Noffke, S. (1997). Professional, Personal, and Political Dimensions of Action Research. Review of Research in Education 22, 305-343.

Noffke, S. & Somekh, B. (Eds). (2009) The SAGE Handbook of Educational Action Research. London, UK: Sage Publications, ltd.

Pineda, C. & Clavijo, A. (2003). Growing Together as Teacher Researchers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal 5, 65-85.

Price, J. & Valli, L. (2005). Preservice Teachers Becoming Agents of Change: Pedagogical Implications for Action Research. Journal of Teacher Education 56 (1), 52-72

Rubiano, C., Frodden, C. Cardona, G. (2000). The Impact of the Colombian Framework for English (COFE) Project: An Insiders’ Perspective. Ikala 5 (9-10), 37-55.

Selener, D. (1997). Participatory Action Research and Social Change. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

Sierrra, A. (2007). Developing Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes through a Study Group: A Study on Teachers’ Professional Development. Ikala 12 (18), 279-305.

Vergara, O., Hernández, F. & Cárdenas, R. (2009). Classroom Research and Professional Development. Profile 11, 169-191.

Webster-Wright, A. (2009). Reframing Professional Development through Understanding Authentic Professional Learning. Review of Educational Research 79 (2), 702-739.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a07

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Action research processes in a foreign language teaching program: Voices from inside

Procesos de Investigación Acción en un programa de formación de docentes de lengua extranjera: voces desde dentro

Juan Carlos Guerra Sánchez1 Zoraida Rodríguez Vásquez2 Claudia Patricia Díaz Mosquera3

1 Universidad Antioquia, Antioquia, Colombia. juguerra6368@yahoo.com

2 Universidad Antioquia, Antioquia, Colombia zorirodriguez@gmail.com

3 Universidad Antioquia, Antioquia, Colombia claudia.diaz@udea.edu.co

Received: 19-Dic-2014 / Accepted: 4-Sep-2015

Abstract

In this article, we report the final results of a multiple case study that brought together the experiences and reflections of student teachers, cooperating teachers, and advisors about the action research process within the framework of the academic practicum in a foreign language teaching program. Through observations, interviews, focus groups, and research report analyses, the researchers recognized the personal, professional, and political dimensions that guide participants’ teaching and research actions. Findings shed light on issues such as collaboration and engagement to promote conversations that actually connect life in schools and life at the university, and to support continuous learning for teachers. The insights we gained evidenced that the teachers, students, and administrators in the teaching program and their colleagues in the public schools need to strengthen their links through proposals of experiential learning which promote joint efforts, symmetric relationships, and expertise co-construction; thus, enabling all participants to validate their process as individuals, as members of educational institutions, and as key actors in promoting and sustaining a better society.

Keywords: action research, case study, teaching practicum

Resumen

Este artículo presenta los resultados finales de un estudio de caso múltiple sobre las experiencias y reflexiones de los practicantes, los profesores cooperadores y los asesores universitarios sobre la investigación acción en el marco de su práctica docente. Por medio de observaciones, entrevistas, grupos focales y análisis de trabajos de grado, los investigadores reconocieron las dimensiones personales, profesionales y políticas que guían las acciones pedagógicas e investigativas de los participantes. Los resultados permiten tener pautas claras sobre asuntos como la colaboración y el compromiso, para mantener una comunicación que conecte realmente la vida en las escuelas con la vida en la universidad, fortaleciendo nuestro aprendizaje continuo como maestros. Los resultados evidencian que los profesores, estudiantes y administradores de la Licenciatura y sus colegas en las escuelas públicas necesitan fortalecer lazos a través de propuestas que promueva esfuerzos conjuntos, relaciones simétricas y co-construcción de experticia, con el fin de validar y reflexionar sobre sus procesos como individuos, como miembros de instituciones educativas y como agentes claves para mantener y promover una mejor sociedad.

Palabras clave: investigación acción, estudio de caso, práctica académica

Introduction

As teachers and practicum advisors in a foreign language teaching program (FLTP) at a public university, we have completed different academic experiences such as Seminario de asesoría de práctica docente investigativa en lenguas extranjeras4 (Arias, 2007) which enriched our understandings of action research (AR). Such a seminar arose as an answer to the need of having better prepared teachers to foster the research component in that program, and to the demand at that time for new practicum advisors due to the high number of student teachers and practicum centers.

In this seminar, we discussed how students brought together the linguistic, research, and pedagogical components of the program in the courses Practicum I and II, Research Seminar I and II, and Action Research Report Writing Seminar, taken by students in the ninth and tenth semesters, and guided by one, two, or three advisors depending on their expertise in teaching or research, and their availability. Also, we discussed the implications of carrying out the practicum at public schools—elementary or high school—or at the practitioner’s workplace where they had to stay for a minimum of four hours initially completing observations and later co- teaching in the company of a cooperating teacher (C-teacher).

We also realized and discussed the different perspectives we had concerning AR principles and procedures, including: 1) the diversity of advisors’ experiences as teachers and researchers that showed different stances towards the pedagogy of AR. 2) The scant discussion of AR principles within the academic community of the FLTP, and finally 3) the greater concern about the procedures and the AR cycle rather than on the epistemological and ontological principles that support them.

Since developing shared meanings on AR was essential for us, we put together as a final task a research project which we called Change, Reflection and Action: Transversal Axes in AR. It was intended to make our guiding principles explicit, connect them to current research paradigms, and characterize the main AR principles stated in the professional literature. In fact, our question was: How does the examination of participants’ understandings of the AR guiding principles in Seminario de Asesoría de práctica docente investigativa en lenguas extranjeras5 allow us to construct shared meanings about the implementation of AR in the practicum cycle at the FLTP?

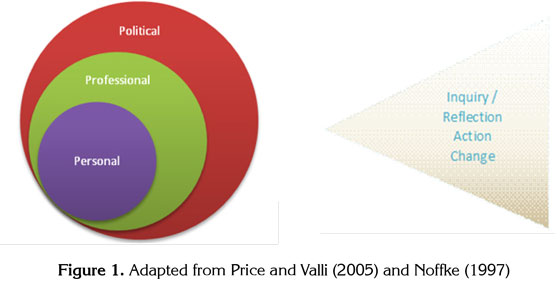

This meant for us to talk about self-reflection, participation, and social transformation. Authors like Zeichner (1993, cited in Price & Valli, 2005) point out how AR can cause change in, “(a) individual teacher development and the quality of teaching, (b) the control of teaching knowledge, (c) the institutional context, and (d) the broader social context” (p. 58). Noffke (1997) used the concepts of dimensions to name the political, professional and personal realms where AR can have an effect. Figure 1 summarizes our interpretation and part of our foundation for this project:

This research exercise showed that technicalities seemed to be the focus of the AR process in the practicum, and they were isolated from personal processes. In addition, political action was understood as a messianic process that benefits others rather than a process of negotiation and construction. So, it was hard to embody it in one’s actions.

The seminar ended and we continued working as advisors. Many students completed different research projects and for us questions kept arising. However, there had not been a specific evaluation on the kind of effect that AR processes had produced in the different participants. Therefore, we defined our research question for the present study as: What is the impact of action research projects in the professional development of student-teachers, cooperating teachers, and advisors in two public schools within a FLTP academic practicum?

For this case study, AR projects go beyond final products, and they encompass multiple dynamics associated with how personal, professional, and political dimensions interact. These would contribute to encourage participants to take their professional learning in their own hands.

Theoretical Framework

It is important for us in the theoretical discussion to have a historical view of AR because through time different perspectives and emphases have been taken. We deem it necessary to understand the reasons to use AR and how participants have experienced them. We also consider it important to include a brief discussion of the differences between traditional action research and critical participatory action research.

Action Research

AR has been one of the most important and influential modes of teacher learning, one of the best ways to foster teachers’ reflection, action, and transformation of their practice for it is “a systematic and intentional inquiry about teaching, learning, and schooling carried out by teachers in their own school and classroom settings” (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1993, p. 27). Carr and Kemmis (1986) characterized AR as “simply a form of self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own practices, their understanding of these practices, and the situations in which the practices are carried out” (p. 162).

Having its origins in the early 1900s, the history of AR is a source of scholarly inquiry and many researchers have traced AR to its inception to figure out the great variety of its forms (Noffke, 1994, 1997; Noffke & Somekh, 2009). AR began with the intention of improving the quality of life and the betterment of people’s working conditions. Its major contribution was to focus human action on the reduction of prejudice and the fostering of democracy (Noffke, 1994). These ideas became the source of multiple interpretations.

In the 1950s, Stephen Corey promoted AR to improve educational practices, for it was most likely for teachers and administrators to implement results if they worked together as partners in the research process (Selener, 1997). The methodology proposed consisted of identifying a problem, exploring its causes, generating an intervention plan, carrying out the actions, and jointly evaluating the results.

Some years later in Great Britain, Stenhouse fostered a perspective of AR that viewed teachers as competent professionals who could make research the base of teaching and curriculum development. He suggested that:

Professional education involved: The commitment to systematic questioning of one’s own teaching as a basis for development; the commitment and the skills to study one’s own teaching; the concern to question and to test theory in practice by the use of those skills. (Stenhouse, 1975, cited in McNiff & Whitehead, 2006, p. 37)

He promoted the joint collaboration of researchers and teachers to solve curricular and teaching issues. Elliot (1991) and Adelman (1993) encouraged the use of inquiry as a tool for teacher learning and having teachers own their practices.

In the 1980s, Carr and Kemmis (1986), and McTaggart (1988), within an atmosphere of curriculum development, the promotion of social justice and struggle against oppression, developed a more participatory action research proposal based on the work of critical theory by Jurgen Habermas (Somekh & Seiner, 2009). In the last decades, AR has kept thriving and changing. Noffke (1997) pointed out that AR publications have increased and projects like ‘the teacher research movement,’ led by renowned scholars such Marilyn Cochran- Smith, Susan Lytle, Ann Lieberman, Dixie Goswami, among others, have gained an increasing visibility because of the professional knowledge and new conceptualization of knowing generated by teachers.

In Latin America, the AR tradition has been greatly influenced by the social, critical, and emancipatory work of Paulo Freire. Flores-Kastanis, Montoya-Vargas, and Suárez (2009) talk about his work suggesting that:

Freire underscored the importance of articulating education within a wider project of political and cultural liberation, oriented to ‘reading the world’ and for popular education to become cultural and political action for the transformation of society, promoting cooperation, autonomous decision making, political participation and ethnical responsibility. (p. 458)

In Colombia, Orlando Fals-Borda (cited in Flores- Kastanis, Montoya-Vargas, & Suárez, 2009) marked the path of participatory action research (PAR). He and his colleagues developed a methodology called study-action that eventually became PAR. This method was created “to systematize popular knowledge and give it back to the groups they worked with, to motivate collective action toward social and political change against oppressive powers” (Flores-Kastanis, Montoya-Vargas, & Suárez, 2009, p. 460). Though these two scholars have influenced AR all over the world, it has not been the case for educational AR in foreign language in Colombia. AR was introduced in our public universities as part of the suggestions made by the COFE project, a nation-wide United Kingdom-Colombia technical cooperation arrangement, led by the British Council, to improve the teaching of English in our country (Rubiano, Frodden, & Cardona, 2000).

Understanding AR from a critical theory paradigm (Glesne, 2011) led us to consider critical participatory action research (CPAR) (Kemmis, McTaggart, & Nixon, 2014) as an appropriate framework for our research endeavors. The purpose of CPAR is “to change social practices, including research practice itself, to make them more rational and reasonable, more productive and sustainable, and more just and inclusive” (Kemmis, McTaggart, & Nixon, 2014, p. 2). Participation is a key element in this process and is framed with the concept of ‘public spheres,’ an open space for communication where participants talk and share about themselves, their lives, and their projects. This space is an opportunity to engage participants, even if they are outsiders, in a horizontal conversation about each other’s roles and responsibilities in the research process. In addition, it fosters conditions for reflection, collaboration, and practice as a result of being ‘insiders’ in the process. CPAR participants are constantly reflecting on their own practices and their consequences, and how these are shaped by the conditions under which they occur. CPAR invites and requires engagement. As participants care for their practices and outcomes, they experience a profound level of engagement because research projects go beyond technical purposes and involve personal and political ones, expanding AR’s reach towards broader social and political arenas (see Kemmis, McTaggart, & Nixon, 2014).

Professional Development

Even though the needs of pre- and in-service language teachers are different and require varied ways to be addressed, we want to highlight the power AR has as space for professional learning, with either novice or full-fledged teachers.

Desimone (2009) suggests that professional development (PD) can be any activity that allows teachers to improve their professional, personal, and social skills; activities, she explains, that “can range from formal, structured topic-specific seminars given on in-service days, to everyday informal “hallway” discussion with other teachers about instruction techniques, embedded in teachers’ everyday work lives” (p. 182). Diaz-Maggioli (2003) contends that:

Professional development focuses specifically on how teachers construct their professional identities in ongoing interaction with learners, by reflecting on their actions in the classroom and adapting them to meet the learners’ expressed or implicit learning needs. The ultimate purpose of professional development is to promote effective teaching that results in learning gains for all students. (Para. 3)

Finally, Webster-Wright (2009) offers that “professionals learn, in a way that shapes their practice, from a diverse range of activities, from formal PD programs, through interaction with work colleagues, to experiences outside work, in differing combinations and permutations of experiences” (p. 705).

These ideas offer us an alternative framework to explore how the participants in this project viewed the effect of AR in their professional learning and how the creation of learning communities can make a difference for both novice and experienced teachers.

Methodology

Within the qualitative design, Creswell (2007) describes case study as the exploration of a bounded system (a case), or multiple bounded systems (cases), through in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information. The phenomenon is studied in its natural context bounded by space and time, and the analysis of a case implies the identification of recurrent themes and a careful understanding of their complexity in order to move to an interpretive phase to explain “lessons learned” (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, cited in Creswell, 2007). Hancock and Algozzine (2006) emphasize that the rich description and the extensive information gathering determines case study as an exploratory rather than a confirmatory methodology which allows for an overall understanding of the phenomenon at the same time that existing professional literature is examined.

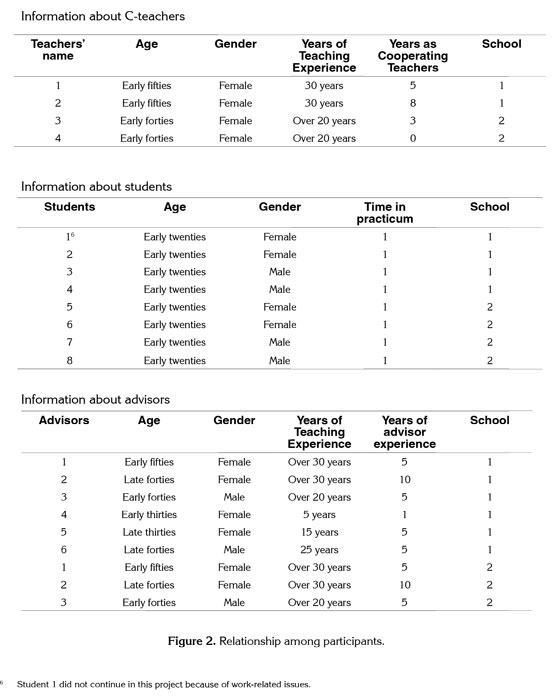

As shown in Figure 2 below, the cases were defined in two public schools, the former being the one in the practicum process for a longer period, and the latter being the one with the highest number of students accepted at the time we started this project.

6 Student 1 did not continue in this project because of work-related issues.

Information about C-teachers

In School 1, both C-teachers were about to retire and were highly committed to teaching and to advising students. Advisors 1, 3, and 4 were willing to explore and learn together with students, and find alternatives to teaching and research. As for advisors 5 and 6, they were experienced researchers who were mostly concerned about formal stages of the research process. For all the students, the practicum was their first teaching experience.

In school 2, C-teacher 3 was actively involved in teaching and research at school, whereas C-teacher 4 was mainly concerned with meeting school duties. Advisor 2 was a very creative and experienced teacher very close to her students. Student 6 had experience working with large groups; student 7 and student 8 were both novice teachers.

We used the following tools for data collection: students’ AR reports, four focus groups, five interviews, and we designed the tool: One Day In (Someone’s) Life (ODISL) (un día en la vida de…).

ODISL allowed us to spend a day’s work (including classes, meetings, recess, and other) with each participant, to witness their actual practice in order to articulate the data with a closer sense of reality, and understand the effect of the practicum on their professional learning. This tool was organized with a format that had a section for a detailed description of the actions and events the participant interacted with, along with a space for wonderings, connections, and questions. Once the format was completely transcribed, it was handed out to all the researchers to read and write down their questions and comments.

Once we had an in-depth reading of each ODISL, we carried out a semi-structured focus group with each group of participants, and interviews with some of them in which we used protocols with questions that revolved around their roles and experiences in the practicum (See Appendix A and B). The question that prompted the conversations with students was: What do you remember the most about the practicum?

Regarding the advisors, the question was: How has your experience advising in the practicum and research seminar been and for how long? Finally, we asked C-teachers: What was teaching experience like in that particular school? All of these questions allowed them to share relevant connections with AR, the bonds they created with C-teachers, advisors and students, the roles C-teachers have in their schools, which at the same time depicted the roles students were to take up in these same schools, among other issues.

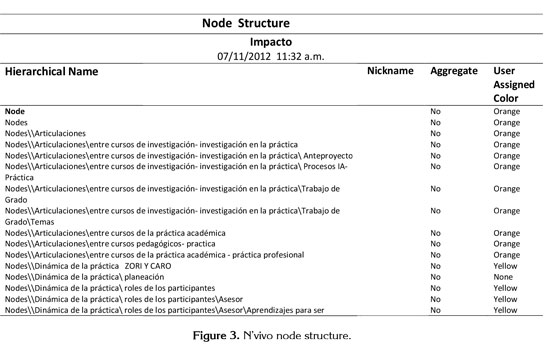

Once transcribed, we constructed a web of nodes articulating the sets of data we derived from each tool using the analysis software N’vivo (See Figure 3).

As we coded, we came to understand that in each school there were specific connections, roles, concerns, and relationships among the participants, then the coding moved to analyzing the cases as networks in each school. We organized and articulated recurrent themes in the conversations and actions for each group of participants, and recorded our actions, discussions, and proposals for the ongoing development of the project and the proposal for the practicum.

As for the students’ research reports, we read and analyzed the last part of the report where conclusions, reflections, and suggestions were written. We coded the data trying to understand what of sort impact the research and practicum processes had on the students. These became part of the web of nodes we created with the rest of the data.

Data Analysis

Each school became a case and which we named microcosmos and each included an encounter of a student, a C-teacher, and the advisor(s). The particularities of every dialogue unfolded the participants’ backgrounds and expectations; thus, their contributions to understand how the practicum may evidence a PD process.

Case 1

Microcosmos 1

In this triad, student 2 became the core that evidenced and articulated conversations with C-teacher 1 and advisor 2. Dialogue and collaboration were the key elements that connected the personal dimension each brought to this relationship. The interactions between C-teacher 1 and student 2 contributed to reciprocal learning as they shared their teaching lives at school, their interest of engaging parents, as well as their commitment for the holistic development of children. Advisor 2 encouraged student 2 to create relevant connections with the students in order to make informed decisions for their language learning process in their context. Her professional and personal companionship made a difference in student 2’s conception of AR as a means to understand her process as an educator. Even though she managed to meaningfully articulate her interactions with advisor 2 and C-teacher 1 to grow as a professional FL teacher, C-teacher 1 and advisor 2 did not have a direct connection.

As a novice teacher, student 2 made a retrospective evaluation of her process as an undergraduate student and regretted the lack of opportunities to have real and everyday life experiences at schools early in the teaching program. She considered it relevant to know if all the theory learned would be useful for her teaching. Also, she realized that the curricular framework at the university level did not allow undergraduate students and professors to be closer to students and teachers’ lives in elementary or high school levels. That distance did not contribute to her being aware of her real role as a teacher that went above and beyond teaching the FL. She expressed:

When you start teaching at a school, English becomes the least important issue, you already learned English, but I was not taught what to do when a child has a cognitive limitation, for example. I studied a lot of English and a great amount of theory… but what to do in such case! (Student-2 Focus Group, p.20)

Such a lack of connections among the FL, the theory related to FL teaching, and students’ emotional and cognitive development were compensated for student 2, as C-teacher 1 became a role model to look up to. The affective bond C-teacher 1 created with students was subtle, encouraging, and clear as the adult in charge. This experience allowed student 2 to understand the relevance of communication among children’s parents and custodians to construct dynamic relationships in their holistic growth.

The fact of having one advisor made student 2’s work solid and connected to her teaching practice and the research process. Advisor 2 encouraged her to implement actions since the very beginning of her practicum, while developing her research project. Student 2 highlights advisor 2’s encouragement to make informed decisions as a professional and as a researcher through challenging questions that fostered reflections.

Though C-teacher 1 was a great support for student 2, her participation in the research process was limited because she had the idea that students brought their project already defined and she did not have a clear connection with advisor-2.

Microcosmos 2

The following conversations are articulated by the different conceptions participants have about the meaning of research that range between an instrumental task, too many technicalities to accomplish, and social perspective-possibilities for social change.

Group 1. In the first triad, student 4 complained about the time research demanded. It was overwhelming for him considering the many duties he had, aside his planning for class and the school dynamics. Though he found research important and was very committed to it, he felt he would have required more time for his project Fostering oral production through project work.

Regarding C-teacher 2, she was very supportive but expressed that even though she was one of the first C-teachers in this process, she should have been more involved. Though she was aware of the project themes, she dared not suggest her wonderings or ideas about them because she thought that were already defined. For example, project work was one of those themes she wanted to pursue further but she did not go beyond.

As for advisor 3, he considered that AR had to start from students’ beliefs in order to promote not only reflections but also transformative actions. Advisor 3 used to encourage student’s proposals for his class, something that could be seen in some of student 4’s reflections, but not in the conversations with C-teacher 2 which focused on student 4’s performance.

Group 2. In the second triad, student 3, advisor 3, advisor 1, and C-teacher 2, research played also an important role. Student 3 concurred with student 4 that the amount of duties and responsibilities exceeded the amount of time they had for their projects. Nevertheless, he found that academic demands on the part of the advisors also provided him with many tools for his process in the MA program.

He also highlighted that the research process became important for him because he saw the context social reality and was able to envision possibilities of transformation. He considered the practicum a social service that transforms school through innovative ideas.

Though he found AR important for students, he believed other modalities should be considered because the contexts are complex. He was the student who talked more about AR principles and objectives in terms of social responsibility, transformation, and personal involvement. He reckoned this process made him a more critical person in regard to teaching.

This could also be connected to the principles shared by advisor 2 in the research seminar. But, as in previous cases, these principles did not reach C-teacher 2 because, again, conversation among the advisor and the C-teacher focused on the students’ performance in their classes not on research process.

Microcosmos 3

The data showed the strong influence that the personal dimension had in the interaction among these participants. Student 5 was in the middle of divergent perceptions of research and education from advisor 4, advisor 5, advisor 6, and from C-teacher 2, that were overwhelming.

She seemed to be mainly concerned with carrying out technical processes about AR within her project, neglecting her role as a teacher and not really preparing her classes as it should be. She said that she was more concerned about fulfilling the AR advisor’s demands. Though C-teacher 2 was worried about her planning process, she never inquired about it for she thought the dynamics and procedures of the academic practicum were changing. This confirmed again the lack of permanent contact with the advisors to talk about processes other than student’s performance in class.Student 5’s stance towards the AR processes was reinforced by the perceptions advisor 4 had of her role as helping students to think and to avoid mediocre work. Similarly, advisor 5 went even beyond helping to consider “enlighten” (A day in the life of Advisor-5, p. 20) as the key process. Having them “doing her homework,” rather than supporting their understanding of what AR implies was what mattered. Advisor 5 explained, “I evaluate the formative processes, when they designed a survey and later refined it to achieve the right focus, the objective was accomplished, even if the data they collected were not relevant …” (A day in the life of Advisor-5, p. 21).

In spite of having advisor 6, who invited her to reflect on her actions and to relate to her students in a calm and relaxed way, student 5 was overwhelmed by all the research technicalities she was to respond to. In the words of advisor 6, she was experiencing “knowledge disintegration” because the three advisors accompanying her in this teaching and research process were not articulated and barely talked among themselves.

Also, student 5 had a strong and particular take on what it meant to teach in private and public settings. For her, facing the public school posed other challenges, “you have to control, all the time controlling…” (Student-Teacher Focus Group, p. 2). C-teacher 2 reinforced this position by inviting her to weigh the benefits of working in a private school, making a good salary, and sacrificing personal space and time in a public school dealing with lots of issues and low salaries.

The data indicated that student 5’s personal attitudes towards education and research, and the different people who accompanied her in this process were really influential in her viewing this practicum as a burden, not as a space for growing as a professional.

Case 2

Microcosmos 1

As evidenced in the other triads, there were no conversations among the participants except about the practitioner’s performance in classes.

C-teacher 4’s conceptions of what being a teacher and what teaching meant did not influence much student 8; for her, it was related to discipline and control and giving knowledge. Students have to be completed by the teacher, for she had the elements to do it. She talked about them like, “they are naughty, like little animals, that are just growing” (C-teacher 4’s interview, p. 5).

There was no evidence of community making because she considered the teacher as the authority and classroom management as the goal. Students who did not fit her model needed to be corrected, controlled, or punished. Student-teachers were suggested to “maintain order,” keep them busy, and make them memorize in class.

As for advisor 1 and C-teacher 4’s relationship concerning AR, it was limited to the general information given by advisor 1 at the beginning of the process. Similar to other triads, C-teacher 4 did not actively participate in any of the AR projects and she never followed their development.

C-teachers 4’s perspectives did not influence student 8. In contrast, he expressed that reflections through the practice and about AR in general were meaningful for him because, as he implemented his project, he realized the social dimension of teaching, found the importance of questions, and strengthened his beliefs about the teacher’s role as a social and political agent that can promote transformation.

The conversations with advisor 1 supported student 8’s principles about teaching for he had an open mind to suggestions and reflections. Advisor 1 insisted on observing and knowing the classroom context well and understanding how it influences not only students but also what we are as teachers. This often invisible political dimension led her to promote meaningful connections between classroom practices and the national context, expanding the teacher’s role from a micro to a macro perspective. Her conception of AR recognizes that changes are possible and, that even being small, they begin with the student. What can be seen here is the importance of considering students’ beliefs. Nevertheless, these considerations about AR did not make part of advisor 1 and C-teacher 4’s conversations and collaborative research did not occur.

Microcosmos 2

Once again, the personal dimension came to the front in this triad, student 7, C-teacher 4, and advisor 3. The conception of school held by student 7, oriented towards an ideal place where students learn on their own and behave well in a context with no social problems clashed with the public school reality and shocked him. This impact was strengthened by C-teacher 4’s particular view of controlling discipline as the major role of the teacher. She encouraged student teachers to develop and bring materials that kept students busy. The outlook C-teacher 4 had of the class was not very motivating and she had little faith in the learners she was working with.

This interaction with C-teacher 4 and his own ideas about the public school led student 7 to take a particular stance towards this process as he implemented his project, expressing his discontent and hopelessness and revealing a short-sighted image as a teacher and as an educator:

One of the strongest impacts is to realize that I am not a teacher. I am just an English or French teaching technician, just that. I am not an educator, not a teacher, nothing. I just happen to know English and some teaching methods, I don’t know more. (Student-Teacher Focus Group, p. 24)

Though the conversation with advisor 3 was focused on understanding the context and how AR could generate alternative teaching and learning opportunities for this class, student 7 thought that other ways of doing research in public schools should be suggested because AR was not completely possible due to the context limitations and dynamics. He argued for a narrative process or something similar, for AR seemed to not fit his idea of research, as he stated, “I am not like Christ. I don’t want to change the world. In the school [of languages], I was trained to teach English and French. I was not taught how to educate people” (Student-Teacher Focus Group, p. 12).

This triad showed again how personal decisions and choices, based on experiences and ideas, affect the processes of professional learning. Even though student 7 had some spaces to talk about language learning and the teaching process, and research in more holistic ways, the view of C-teacher 4 prevailed and he took up a stance that rendered him hopeless of a better relationship with teaching in public schools:

I remember [the practicum] as a stage in which I did not grow as a teacher because eventually I gave up. The system beat me and I ended up on the commonplace of the public school teachers: just simply controlling discipline. (Student-Teacher Focus Group, p. 2)

Microcosmos 3

The experience of working in different grade levels and contexts was a common experience among student 6, C-teacher 3, and advisor 2. They were sensitive to life in public schools and aware of the need of knowing students and their circumstances to take actions accordingly.

Advisor 2 constantly raised important questions when interacting with students. As they stated, her encouragement led to reflection about the incidence of students and school context conditions in the FL learning process so that they could design contextualized lesson plans, and implement and evaluate their actions. As for student 6, her experience working with large groups in reading promotion helped her to be attentive to students’ demands and circumstances. To complete this interaction, C-teacher 3’s know-how of the practicum, the school site, and her experience and connection to research eased the development of actions at different levels.

C-teacher 3 was very committed to support student 6 in group management, and enjoyed learning from the ideas student teachers brought in. Also, promoting a sense of community was a key belief inside the classroom as a teacher, and in the school, as she considered that a sense of belonging enabled her to really participate. She considered that partaking responsibilities with the school administration was a need.

Among the C-teachers, she was the only one fully involved in research. For her, school teachers are in an advantaged role being immersed in the reality the school offers, which at the same time is not taken advantage of enough. She pointed out:

Basically, what we teachers do on daily basis is the material for research. Many sociologist and researchers wish to have the human capital we have in our hands to work with it. […] I and we have a bad habit of not writing. We write little about our practice, about what we do. And research asks for a constant and systematic record of what we do, of the changes we propose… (CT3 Interview, p. 21)

She also noticed that in the last semesters students had not joined her in school activities, and she seemed very sensitive to students’ time because they had an allotted time for their school activities and she did not want to interfere with it. However, she regretted this situation because she found that students were not experiencing the dynamics of school life, and they were just simply doing activities at school. She went even further suggesting that this experience should be more like an internship in which students could really understand what happens in school on a daily basis.

In this context, advisor 2 played a significant role by constantly questioning student 6 to engage her in deepening and refining her ideas concerning her practice. This attitude was an important support for her to move from her doubts about what students were actually learning to her becoming aware of students’ actual response to her teaching. Her students themselves evidenced the impact of trusting them when they told that they learned when they enjoyed it. Student 6 realized that trusting them and promoting meaningful relationships helped them connect with the FL while implementing her AR project.

Conclusions

The lessons we learned concerning the impact of the implementation of AR on the professional development of participants in the practicum raised our awareness on the central role the personal dimension played on fostering their professional and political beliefs and actions.

Students evidenced their attempts at articulating their personal dimension and the discourses they constructed during their undergraduate courses, to the advisors’ perspectives, along with the interactions with the C-teachers and the students at schools. The tensions created in these exchanges were decisive on their self-image and roles as language teachers, researchers, and learners. The lack of dialogue, collaboration, engagement, and affection among the participants had students take up sudden responsibilities which resulted sometimes in very negative experiences.

We also learned that students realized that they needed to be aware of and be part of the multiple processes at school and the roles they played in them. We identified three “self-awareness moments” from students’ perspectives that evidenced a possible framework for their PD: 1) Becoming aware of self at school, 2) of self as a researcher, 3) of self as a potential knowledge constructor. The first was linked to the idea that their role at school went beyond teaching English. They lived the impact of affective factors in learning processes, and the actions they were to take as teachers, considering sometimes the C-teachers as “models of praxis.” The second one addressed the possibility of being someone who uses research for reflection, action and transformation, or someone who follows procedures and research gurus. And the last one offered the possibility of figuring out how to resolve the clash between the reality at schools and what they learned at the university.

Concerning the advisors, we found that their understanding of AR essential principles like participation, collaboration, mediation, and transformation articulated with their actions evidenced the potential their personal dimensions had to silence or give voice to participants. Provided that they have a clear grasp of those principles, not only its technicalities, they could orchestrate interactions relating students and C-teachers as colleagues, sharing, assisting, and fostering self- inquiry and problem solving as part of their PD.

As for C-teachers, their scant participation in AR projects restricted the unfolding of their personal dimensions limiting their PD just to learning about new resources and strategies. They considered that students were the experts in the FL so their ’new’ ideas and projects were unquestionably accepted. They censored themselves to give opinions about students’ projects and did not value their expertise enough as school teachers and potential learners in AR processes.

FLTP practicum coordinators claimed for spaces to share and strengthen with colleagues their conception of AR that could go beyond the technical procedures and share what they have learned from their own exploration as researchers. Similarly, the academic coordinator of school 1 expressed her strong belief regarding the possibilities of the school as a meeting site for collaboration, learning, and teacher growth.

In conclusion, we believe that the construction of symmetric relationships within the framework of the academic practicum would enable the participants’ development of their personal dimensions, acknowledging who they are and the roles they play, to grow together as people, as professionals, and as political agents.

Further Implications

In order to put into action our insights derived from this project, we created LAS ESCUELAS EN LA ESCUELA. In this event, all of the participants had the time and space to listen to, and learn from their experiences, with their own voices, without the mediation of experts. We all concluded that we were able to get together, even with our busy lives, in order to construct learning communities. This event will be held every other year, and it is the opportunity to reconcile the gap between school and university where we all acknowledge common aims that keep us committed to educating ourselves, with our colleagues and students.

To walk our talk, we are putting forward a proposal for the practicum within the framework of the curriculum redesign in the FLTP in our university. Our main contribution is the creation, implementation, and evaluation of the Professional Learning Collectives (PLC), an ongoing learning group in which equitable participation is fostered in order to encourage symmetric relationships that favor professional awareness, growth, and action.

Reviews4 Teacher Research Advisory Seminar

5 Teacher Research Advisory Seminar

References

Adelman, C. (1993). Kurt Lewin and the origins of action research. Educational Action Research, 1(1), 7-24.

Arias, C. (Ed.). (2007). Seminario: Asesoría de práctica docente investigativa en lenguas extranjeras/ lecturas. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia.

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge, and action research. London, UK: Routledge Farmer.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. (1993). Inside outside: Teacher research and knowledge. New York, N.Y: Teachers College Press.

Creswell, J. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. (2nd Ed.) Thousands Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Desimone, L. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Towards better conceptualization and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181-199.

Díaz-Maggioli, G. (2003). Professional development for language teachers. EDO-FL, 03-03. ERIC Digest.

Elliot, J. (1991). Action research for educational change: Developing teachers and teaching. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Flores-Kastanis, E., Montoya-Vargas, J., & Suárez, D. (2009). Participatory action research in Latin American education: A road map to a different part of the world. In S. Noffke & B. Somekh (Eds), The SAGE handbook of educational action research (pp. 454-466). London, UK: Sage Publications, ltd.

Glesne, C. (2011). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction, (4th. Ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Hancock, D., & Algozzine, B. (2006). Doing case study research. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). (Eds.). The action research planner. (3rd ed.). Australia: Deakin University.

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

McNiff, J., & Whitehead, J. (2006). All you need to know about action research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Noffke, S. (1994). Action research: Towards the next generation. Educational Action Research, 2(1), 9-21.

Noffke, S. (1997). Professional, personal, and political dimensions of action research. Review of Research in Education, 22, 305-343.

Noffke, S., & Somekh, B. (Eds). (2009). The SAGE handbook of educational action research. London, UK: Sage Publications, ltd.

Price, J., & Valli, L. (2005). Preservice teachers becoming agents of change: Pedagogical implications for action research. Journal of Teacher Education, 56(1), 52-72.

Rubiano, C., Frodden, C., & Cardona, G. (2000). The impact of the Colombian framework for English (COFE) project: An Insiders’ perspective. Ikala, 5(9- 10), 37-55.

Selener, D. (1997). Participatory action research and social change. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

Somekh, B., & Seiner, K. (2009). Action research for educational reform: Remodeling action research theories and practices in local context. Educational Action Research, 17(1), 5-21.

Webster-Wright, A. (2009). Reframing professional development through understanding authentic learning. Review of Educational Research, 79(2), 702-739.

Métricas

Licencia

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/