DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n1.9660Publicado:

2016-05-11Número:

Vol 18, No 1 (2016) January-JuneSección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónA discourse -structural analysis of Yorùbá proverbs in interaction

Un análisis del discurso-estructural de proverbios Yorùbá en interacción

Palabras clave:

análisis del discurso, cultura, proverbios, análisis estructural, Yorùbá (es).Palabras clave:

Proverbs, discourse analysis, structural analysis, culture, Yorùbá (en).Descargas

Referencias

Ambrose, A. M. 1996. Proverbs in African Orature: the Aniocha-Igbo experience. Maryland: University Press.

Babalola, A. 2012. Proverbs in Discourse. Ibadan: Krafts Book.

Bámgbósé, A.1968. The form of Yoruba Proverbs. ODU, A Journal of West African Studies 4 (2): 74-86.

Boadi, Lawrence A. 1972. The Language of the Proverb in Akan. African Folklore. Ed. Richard Dorson. NewYork: Anchor. p183–91.

Brown, G and Yule, G. 1983. Discourse Analysis. New York. Cambridge University Press.

Ehineni, Taiwo O. (forthcoming). “The Pragmatics of Yorùbá Proverbs in Yerima’s Igatibi, Ajagunmale and Mojagbe”. Issues in Intercultural Communication. Nova publishers

Fasiku, Gbenga. 2006. “Yoruba proverbs, names and national consciousness” The Journal of Pan African Studies. 1 (4).

Fayemi, Ademola, K. 2010. “The Logic in Yoruba Proverbs”. Itupale Online Journal of African Studies.

Finnegan, R. 1970. Oral Literature in Africa. Oxford: Clarendon Press

Hallen, Barry.2000. The Good, the bad and the beautiful: Discourse about Values in Yoruba Culture: Bloomington: Indiana UP.

Halliday, M.A.K. 1978. Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Meaning. London: Edward Arnold

Isidore Okpewho. 1992. African Oral literature. Indiana University press.

Kelani, Tunde. Agogo Èèwọ̀. Lagos: Mainframe productions. 2000.

Kelani, Tunde. Saworoidẹ. Lagos: Mainframe productions. 1999.

Mey, Jacob. 2001. Pragmatics: An introduction. USA. Blackwell Publishing.

Obeng, Samuel. 1996. “Proverb as mitigating strategy in Akan discourse”. Anthropological linguistics.

Olatunji Olatunde. 1984. Features of Yoruba oral poetry. Ibadan University press Ltd

Osisanwo, W. 2003. Introduction to discourse analysis and pragmatics. Lagos: Ebute meta

Owomoyela, O. 1981. “Proverbs: Exploration of an African Philosophy of Social Communication,” Basiru 12 (1), pp. 3 -16

Owomoyela, Oyekan. Yorùbá Proverbs. University of Nebraska Press. 2005

Raji-Oyelade, A. 1999. ‘‘Postproverbials in Yoruba Culture: A Playful Blasphemy.’’ Research in African Literature. 30 (1)

Tragott, E. C and Pratt, M. L 1980. Linguistics for Students of Literature. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc.

Wolff, Hans. 1961. Introductory Yorùbá. African Language and Area Center. Michigan State University Press.

Wolfgang Mieder. 2004. Proverbs: a handbook. Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Yankah, Kwesi 1989. The proverb in the context of Akan rhetoric. A theory of proverb praxis. New York. Diasporic African press

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n1.9660

RESEARCH ARTICLES

A discourse-structural analysis of Yorùbá proverbs in interaction

Un análisis del discurso-estructural de proverbios Yorùbá en interacción

Taiwo Oluwaseun Ehineni1

1 Indiana University, United States. taiwoehineni@gmail.com

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Ehineni, Taiwo O. (2016). A Discourse-Structural Analysis of Yorùbá Proverbs in Interaction. Colomb.Appl.Linguist.J., 18(1), pp 71-83

Received: 19-Nov-2015 / Accepted: 20-Jan-2016

Abstract

The subject of the proverb especially in the African context has been diversely explored by studies as Yankah (1989), Obeng (1996), Owomoyela (2005), and Fasiku (2006). This study, however, attempts a discourse and structural analysis of Yorùbá proverbs collected from oral interviews and native Yorùbá texts. First, based on a theory of the proverb as a discourse medium, the study reveals that proverbs are used to achieve different discourse acts and communicative goals by speakers. Native speakers use the proverb as a linguistic strategy of negotiating deep ideas and intentions. Second, the paper avers that the Yorùbá proverb is structurally characterized by some lexical and grammatical devices which help to reinforce its communicative intelligibility and textuality. Thus, it examines the Yorùbá proverb both functionally and formally and underscores that it is a culturally and linguistically rich significant part of the Yorùbá speech community.

Keywords: discourse analysis, culture, proverbs, structural analysis, Yorùbá

Resumen

El tema del proverbio sobre todo en el contexto africano ha sido diversamente explorada por estudios como Yankah (1989), Obeng (1996), Owomoyela (2005), y Fasiku (2006). Este estudio, sin embargo, intenta un discurso y análisis estructural de los proverbios Yorùbá recogidos de entrevistas orales y textos Yorùbá nativas. En primer lugar, sobre la base de una teoría del proverbio como medio discurso, el estudio revela que los proverbios son utilizados para conseguir diferentes actos del discurso y los objetivos de comunicación de los oradores. Los hablantes nativos usan el proverbio como una estrategia lingüística de la negociación de las ideas profundas e intenciones. En segundo lugar, el documento afirma que el proverbio yoruba se caracteriza estructuralmente por algunos dispositivos léxicos y gramaticales que ayudan a reforzar su inteligibilidad comunicativa y textualidad. Por lo tanto, se examina el proverbio yoruba tanto funcional como formal y se pone de relieve que se trata de una parte rica culturalmente y lingüísticamente significativa de la comunidad de habla yoruba.

Palabras clave: análisis del discurso, cultura, proverbios, análisis estructural, Yorùbá

Introduction

The proverb is a veritable, effective, and significant means of mutual communication among people in different cultures and communities. It embodies the totality of the history, sociology, and psychology of a given society. While functioning furthermore in a most invaluable capacity, as custodian and repository of ancient lore and wisdom handed over from generation to generation as in a relay of cultural traditions, it expresses in rather concise yet coherent terms the values and virtues of a given culture and society. Its relevance and significance in the society have been substantially acclaimed and extensively affirmed. Yankah (1989) opines, based on his work on Akan rhetoric, that proverbs play a major role among the Akans during interactions. Obeng (1996) argues that proverbs can be used as a device for mitigating conflicts among people. Based on a study on some Akan interactions, he reveals how proverbs are used to reduce the potentiality of crisis during interaction. Similarly, among the Yorùbás, proverbs play major role in discourses. Proverbs constitute a major linguistic repertoire of the Yorùbá people and they are often passed over from generation to generation. They are also useful for moral instruction in the Yorùbá society. While exploring the nature of Yorùbá oral poetry, Olatunji (1984) projects the significant functionality of proverbs in Yorùbá society. He registers that proverbs serve as "social charters, to praise what the society considers to be virtues and condemn bad practices" (p. 170). Therefore, they generally explain, explore, and describe issues, events, trends, and experiences in human society. They are therefore products of the society. This is why every proverb is peculiar to its society. Proverbs are also used as resources of informal education for the young by the elders who strive to provide them with necessary guidance.

Furthernore, Owomoyela (1981) discusses Yorùbá proverbs as a means of foregrounding an African [Yorùbá] philosophy of social communication. He describes how they are widely yet appropriately deployed in Yorùbá African culture for social communication which is also correlative of social order. Therefore, they serve as means of achieving discourse clarity and conciseness (Fasiku 2006). Proverbs are hence powerful tools for facilitating communication in an interaction among the Yorùbás such that when people find it difficult to successfully pass a piece of information, proverbs are most often engaged to effectively disseminate the idea. Thus, deploying proverbs has become the most important and effective strategy devised by the Yorùbás to adequately optimize the efficacy of a message in such a way that what is said is able to reaches the intended audience clearly and unadulterated (Owomoyela 2005).

This study is motivated by the discourse and structural peculiarities, or perhaps complexities, of the Yorùbá proverb. This scholarly adventure is therefore saddled with two general quests: to explore the Yorùbá proverb in discourse, and to explore the Yorùbá proverb in structure. In terms of discourse, it examines the proverb in use in collected Yorùbá conversations with a view to discussing the various "acts" of the proverb is such interactional encounters. It argues most essentially that the proverb is exploited for 'multiplicity of functions' among the Yorùbás. In other words, it is used for the accomplishment of diverse communicative goals. The proverb however, is only "meaningful" in context common to speakers. Speakers often relate within their shared contextual and cultural orientation as they decode ideas from proverbs used in interaction (Ehineni, forthcoming). In terms of structure, it attempts to investigate some linguistic features of the Yorùbá proverb and the processes that it deploys to maintain its form and textuality.

Theoretical background

The proverb has been theoretically discussed by reputable studies including perspectives from anthroplogists, ethnographers, and linguists (Arewa & Dundes, 1967; Bámgbósé, 1968; Finnegan, 1970; Obeng, 1994; Okpewho, 1992; Olatunji, 1984; Yankah, 1986, 1989), as well as others, who have discussed the role proverbs play in managing social conflicts. Herzog (1936) remarks that proverbs "form a vital and potent element of the culture they interpret" (p. 7). Okpewho (1992) and Olatunji (1984) have treated proverbs as social control strategies among the Yorùbá and Asaba (Igbo) of Nigeria.

The Theory of Proverb Praxis

This theoretical approach was advanced by Yankah (1989) based on his famous work, The proverb in the context of Akan rhetoric: A theory of proverb praxis. He theorizes an approach for the study of the proverb based on contextual perspectives. Exploring the nature of the proverb, he explicates that discussing the proverb and identifying its meaning without recourse to context, leads to ignoring the functionality of the proverb as important part of discourse (Yankah 1989). He discusses the social, situational, and discourse contexts surrounding the proverbs. The context of the proverb is crucial in navigating their content. Moreover, proverbs, due to their dynamic nature, have the potential for varied meanings. Context, therefore, helps to identify the intended meaning in a given situation. It should be noted that context in this sense includes not only the social environment in which proverbs are used, but also the social credentials of speakers and audience, and the more immediate situation of use (Yankah, 1989). Yankah's main argument is that the proverb is not ordinary speech, it is an expression with deep cultural information. Hence the context provides the framework for a meaningful study/understanding of proverbs. It is necessary to underscore however that besides the context of situation or use, the cultural context is more essential to uncover the true meaning of proverbs since they often orient to different cultures that have produced them. This is why mutual cultural understanding between proverb speakers enhances discourse success in the speakers' interaction (Ehineni, forthcoming). Speakers must share a common cultural orientation of a proverb to be able to use it in co-negotiation of individual communicative goals in interaction. Essentially, Yankah's theoretical position however, is more of a contextual approach to the proverb. In other words, how context helps to inform the meaning of the proverb.

A Theory of the Proverb as a Discourse Medium

Based on the divergent yet significant discursive acts the proverb is used to perform in Yorùbá cultural interaction, I approach the study of the proverb within the contextual framework of the proverb as a discourse medium which is necessary to uncover the "multiplicity of functions" the proverb is used to achieve in Yorùbá cultural interaction. I see the proverb essentially as a medium or 'messenger' – relating to the Yorùbá view, for a message. This theoretical standpoint is reflected in the Yorùbá statement:

Òwe lẹṣin ọ̀rọ̀

Bí ọ̀rọ̀ bá sọnù, òwe la fi ń wá a

[The proverb is the horse of word

When word is lost, the proverb is the means we use to look for it]

Accordingly, proverbs to the Yorùbás are 'horses' for conveying words to their destinations. The proverb, thus, is a means not an end. To put it in different terms, the proverb is not what the speaker is saying literally, but a way to communicate what is to be said efficiently. The proverb principally mediates between the speaker and the audience. This is why a proverb cannot be interpreted in isolation without the context of the speaker–the proverb does not have an exclusively independent voice, it speaks for the speaker. As Hallen (2000) has astutely observed while commenting on Yorùbá proverbs, ''proverbs do not introduce themselves to us as universal truths, as generalizations that always apply. Their pith, their point, their punch is situational or context-dependent to an essential degree'' (p. 141). A Yorùbá proverb therefore is to be interpreted within the immediate context of use. It is not a message but a 'messenger,' that is, a medium. In Yorùbá sociocultural interaction, proverbs are linguistic constructs often possessed with grave fauna and flora allusions. So, the proverb:

Ogun àgbọ́tẹ́lẹ̀ kì í parọ tó bá gbọ́n

[A forewarned war does not kill a wise cripple]

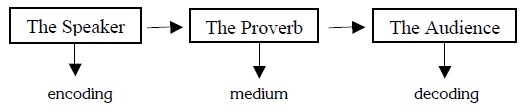

does not necessarily apply to a cripple in the real sense but to a specific audience to which the speaker addresses in the context of use. The use of the proverb is often determined by the user, who uses it as a tool of disseminating his/her ideas and the addressed. Hence, the speaker deploys the proverb as a "messenger" to inform his/her audience. The voice of the proverb is the voice of the speaker. This idea can be more graphically expressed below:

In an interaction network, the speaker encodes the message appropriating the proverb as a 'carrier' to the listening participant who decodes the message within context. Thus, the proverb functions as a means through which the speaker gets to the audience. I therefore engage this theoretical perspective in discussing proverbs in Yorùbá discourses where I discuss the Yorùbá proverb as a strategy or device for achievement of communicative acts and goals among the Yorùbás. From the this theoretical perspective, I examine uses of the proverb in some selected interactions. Methodologically, the interactions are collected from recorded conversations, interviews, and Yorùbá texts. Different contexts of situation are also presented to uncover the discourse functions the proverb carries out in the interactions. Additionally, an analysis of the discourse structure of the proverbs is attempted.

Discourse Acts in Yorùbá Proverbs

Yorùbá proverbs function as discourse acts in Yorùbá interaction where communication is sometimes motivated by the ingenuous deployment of proverbs to facilitate effective dissemination of information. Since the proverb itself is a tool of communication (Fasiku 2006; Owomoyela 2005), I examine to what extent proverbs are used to perform specific acts in Yorùbá discourse. These acts can be grouped into three. First, is face threatening acts which include cautioning and commanding. Second, is face enhancing acts as seen in encouraging and reassuring. The last deals with other acts such as informing and explaning. The idea of face relates to Brown and Levinson's (1987) conceptualization of politeness. They formulated the idea of face based on the notion that people engage in politeness to satisfy others' face demands. According to them, "face" is "emotionally vested and cannot be lost, maintained or enhanced, and must be constantly attended to in interaction" (Brown & Levinson 1987, p. 66). They differentiate two broad types of face, namely, positive and negative. The "positive face" relates to that positive self image that people want to protect and preserve while "negative face" on the other hand concerns rights to take action and avoiding imposition.

Although Brown and Levinson's contention on the universality of face management strategies has been thoroughly debated since the theory allows for some variability across cultures, the concept of "face" itself has been widely used in explicating politeness. I therefore also explore acts that are face threatening or face supporting in discussing discourse acts in Yorùbá proverbs. The term discourse acts is prefered to "face acts" since there are acts in the proverbs that may not necessarily attend to "face." This, therefore, helps to explore other possibilities beyond face provenances in the proverbs. Basically, proverbs are used to achieve different communicative goals within different contexts of discourse. More importantly, every proverb performs an act in discourse.

The interactions analyzed here are based on recorded conversations and interactions in two award-winning popular Yorùbá classics Saworoide and Agogo Eèwọ̀ produced by Tunde Kelani. Both are based on a Yorùbá community Jogbo which chronicles the dynamics of ritual, politics, and power struggles in local leadership. The selected interactions comprise different events where the proverb was used. These interactions are examined to highlight the significant acts and roles the proverbs are used to realize.

Face Threatening Acts

These are acts that threaten the personal image and the self-esteem of particpants or interlocutors in discourse. They may include cautioning, warning, questioning, etc., especially when the hearer exhibits a negative effect.

Setting: At the Babalawo's place in Saworoide, during the traditional rites prior to enthronement, Lápitẹ́ rejects the customs for selfish reasons and tells the traditional chiefs to comply with him:

Lápitẹ́: Àgbà ajá sì ni yín o, ẹ o gbọdọ̀ bawọ jẹ́

[You are older dogs, you must not destroy the skin]

Implying that they are elderly men and should be ready cooperate with him. Apparently, Lápitẹ́ was not willing to observe the expected pre-ordination Yorùbá traditional rites before he ascended the throne and while the traditional priests insisted on the necessity to observe them. He brings out a gun to scare them and uses the above proverb to mandate them to cooperate with him and also to warn/caution them not to do contrary to his decision. Furthermore, since they are traditional people with the mutual contextual-cultural belief, they are able to grasp the import of the Lápitẹ́'s proverb.

By "ẹ o gbọdọ̀ bawọ jẹ́ " (you must not destroy the skin), he warns and threatens the chiefs not to do anything contrary. 'bawọ jẹ́' (destroy the skin) figuratively implies acting against something. Basically, the proverb is used as a threatening strategy. However, this is a direct face threat. Hence, they refrained immediately from pressing further on the issue. Thus, in this discursive encounter, Lápitẹ́ communicated his intention, most effectively, by deploying a certain proverb. In another conversation, this act is also effectively achieved through a proverb:

Setting: Still during the traditional rites performance, Lápitẹ́ further reveals the traditional chiefs of the consequences of not complying:

Lápitẹ́: B'ájá báwá bawọ ẹranko jẹ́, á jẹ́ wípé àwọ̀ ajá alára l'àá lò

[If you now destroy the skin, then the dog's skin will be used]

This is a case of indirect face threat, by unfolding the dire consequences of not complying with him, the speaker threatens the hearers. The proverb is used as an indirect way of threatening the hearer to comply with one's will.

In other words, they will all be in serious dilemma if they fail to agree with his terms. Thus, Lápitẹ́ achieves different discursive goals through this long proverb. While he informs his audience about his intention not to observe the rites and cautions them not to further implore him, he threatens them by proclaiming the attendant penalty of contravening his decision. Similarly, in the next interaction:

Setting: At Olorì Kékeré's room in Agogo Eèwọ̀, during a brief conversation with her daughter who wants to visit her boy friend Arẹ́sẹ́. She cautions her concerning him:

Olorì kékeré's: Ajá ìsín ni kò tí ì m'ọdẹ́, Agbò ìsín sì ni kò tí ì ní ìrọ̀rọ̀

[Today's dog does not know the hunter, today's ram does not have ]

She warns her daughter against having any relationship with Arẹ́sẹ́ whom she loves. The proverb is used to emphasize the boy's naviety and inexperience and that there is nothing she can gain from him. Basically, Olorì Kékeré's aim is to warn her daughter Arápá to desist from seeing the boy immediately since she disapprove of their relationship even though Arẹ́sẹ́ has good qualities. Thus, Olorì Kékeré's warning is not really because the boy is a bad person but because she has personal grudges against him. Arápá knows Arẹ́sẹ́ is a good person and they will make a good couple but she is being threaten by her mother's proverbial utterance in this interaction. This is a instance of a proverbial face threatening act.

Setting: At the palace locality in Saworoide, Ọ̀tún took a step on a sensitive issue and comes to Bàbá Ọ̀pálábá for more counsel. Bàbá Ọ̀pálábá says to Ọ̀tún:

Bàbá Ọ̀pálábá: Ẹ ẹ̀ l'óògùn rìndọ̀rìndọ̀ lẹ lọ ń jẹ aáyán

[You don't have a cure for stomach upset and you are eating mosquito]

The speaker uses the proverb to query the audacity of the hearer (Ọ̀tún) in taking such an action without having any idea on solving its grave attendant consequences. The proverb is used as a strategy of questioning why such action was taken by the hearer without getting full counsel on it in the first place

Setting: In the palace during a conversation between the new king Lápitẹ́ and the log merchants, Lápitẹ́ introduced his disagreement with the merchants:

Lápitẹ́: Omi tuntun ti rú, ẹja tuntun ti wo nú ẹ̀

[Fresh water has flowed, fresh fish has entered into it]

He reveals to them that he is a modern king with a different perspective and so, he is not interested in past policies and regulations. He wants the merchants to agree with him on new terms on how the money can be shared between them. Functionally, the proverb is used by the king to contest and protest against the previously established norms of sharing funds resulting from the log business. Drawing from the proverb, the king's message therefore becomes obvious to the merchants which is instantiated in their response to the king's utterance saying that they are ready to abide by whatever new terms he is proposing. Notably, the merchants' response foregrounds their understanding of king Lápitẹ́'s message through the proverb.

Face Enhancing Acts

These are acts that boost the personal image and the self-esteem of particpants or interlocutors in discourse. They may include appreciating, encouraging, inspiring, etc., especially when the hearer is presented positively.

Setting: At the palace shortly after Lápitẹ's successful coronation. While interacting with the chiefs, Lápitẹ́ says:

Lápitẹ́: Bí ẹ bá ń gbọ́ dòdó ńdá wà, dòdó ńdá wà, ènìyàn ní í bẹ lẹ́yìn dòdó, ẹyin ni igi lẹ́yìn ọgbà mi

[If you hear the saying a flower exists alone, someone is behind the flower, you are the tree behind my garden]

The speaker uses this proverb to first acknowledge the chiefs and praise them for their efforts on his successful coronation. The proverb is used as a face enhancing strategy in Yorùbá interactions. The proverb which is composed of comforting words is used to make the chiefs "feel good." It is a specific attempt attempt to commend the chiefs for their unparallelled and unwaring support for him and also to register his appreciation for making him king over the community. In another interaction, the proverb is used to achieve a similar aim:

Setting: At the palace. Shortly after Làgàta's ascendance to the throne, while discussing with the chiefs on his plans for the town, he says:

Làgàta: Bí iṣẹ́ ò bá pẹni, a kì í pẹ́ṣẹ́

[If the work does not delay, one does not delay work]

Using the proverb, he inspires the chiefs to start taking all necessary actions towards the success of his reign–he encourages them to commit themselves immediately to his service. It motivates them to start their respective duties in earnest and demonstrate every expected commitnment into their responsibilities.

It is important to note that proverbs are used to perform a number of other discourse acts. These are not necessarily face threatening or supporting that are realized through Yorùbá proverbs in interaction or discourse. Proverbs in general among the Yorùbás are tools of communication through which people underscore and exemplify their intentions. These discourse acts foreground the communicative goals in the minds of the speakers.

Explaining

Setting: At the palace locality where Ọ̀tún, a main chief initially assumed an elderly man, Bàbá Ọ̀pálábá was sleeping judging from his posture. During the interaction that ensued afterwards, Bàbá Ọ̀pálábá says to Ọ̀tún:

Bàbá Ọ̀pálábá: Ẹyẹ ò dédé bà lé òle, ọ̀rọ̀ lẹyẹ ń gbọ́

[A bird does not just perch on a roof, it is listening to people's words]

He uses the proverb to explain to his hearer the rationale for his posture and that his disguise affords him the chance of listening to people's words. Thus explaining the rationale for his disguise such that people think he is asleep. He revealed this through the proverb that his disguise affords him the chance of listening to people's words.

Using the proverb therefore was his way of responding to Ọ̀tún, or more aptly, clarifying his actions. This evinces the use of the proverb as a strategy of providing explanations in Yorùbá interactive encounters.

Setting: At the Bọ̀sípò's farm in Agogo Eèwọ̀, during a discussion between him and the traditional chiefs who have come to invite him to be king. One of the chiefs said:

Séríkí: Àgbà ló tó orò lọ̀ ọba ló tó eyín erin fọn

[The elder is capable of carrying the masquerade, the king can blow the elephant's tusk]

This is to explain to him why he is being asked to take up the kingship position. Earlier in the interaction, Bọ̀sípò had asked why other people who are also influential had not been consulted. The chief used the proverb to address this question. The proverb is used to establish his suitability and crediblity for the royal position. That is, he possesses the necessary credentials to efficiently lead the Jogbo community as the king. The proverb thus clarifies to the reluctant Bọ̀sípò the reason why he had been chosen for such noble position.

Setting: At the palace in Agogo Eèwọ̀, during a discussion between the oba and his wife. The king responds to his wife:

Ọba: Ẹ̀rín kò lè gbàrẹ̀kẹ́ ẹni tó ru epo níbi tí ilẹ̀ gbé ń yọ̀

[Laughter does not come to the face of a person carrying oil on a slippery ground]

Olorì, the king's wife, notices the king's uncheerfulness and enjoins him to be happy. The king explains the reason for his moodiness by using a proverb. The proverb reveals to the worried wife that the unpleasant situation of things in the town has been occupying the king's mind and not giving him the reason to smile. Thus, even though she wants her husband to be cheerful, happiness cannot come when things are not going fine in the town. With this proverb, Olorì understands the reason for her husband's uncheerfulness.

Asserting

Setting: At Làgàtá's living room. Làgàtá discusses the worrisome spate of crises in the town and the urgency of change. While Kanjúgo doubts the easiness of change, Làgàtá says in response to Kanjúgo:

Làgàtá : Ohun ọwọ́ mi ò tó, màá fi gọ̀ǹgọ̀n fà á

[Whatever my hand cannot reach, I'll use a rope to draw it]

Làgàtá uses the proverb to assert his abilty to his hearer, Kanjúgo that something can be done concerning the current situation in the town.

The proverb is also used as a strategy of asserting his capacity to act (màá fi gọ̀ǹgọ̀ǹ fà á) inspite of confronting challenges (ohun ọwọ́ mi ò tó). Thus, using the proverb, he asserts his conviction in achieving the aim no matter the confronting challenges. While Làgàtá notes that there may be challenges, he strongly informs his hearer that those challenges will not completely deter him in achieving his aim. Thus, he means that something can be done to address the problem on ground.

Another instance of asserting an opinion is during an interaction between the king and in his wife in Agogo Eèwọ̀ where he states that:

Ohun tí àgbàlagbà ó fi dáná tí ò fi ní jó, ìdí rẹ̀ ni wọn ó báa

[What the elder will use to make a fire and it is not burning; It is at the fire people will meet him]

The king asserts his doggedness and determination in solving the problem of the land. In the face of the diverse problems facing the town, he indicates that he will not relent in his bid to bring peace and prosperity in the land. His main point in the proverb is that even though his efforts have not been productive, he will not give up. He states that he will remain resolute in doing his duties unfailingly as the royal head of the Jogbo town until he achieves success.

Informing/Notifying

Setting: At a traditional festival. Lápitẹ́ calls Balógun and discusses with him very serious matter:

Lápitẹ́ : Òkú tí ẹ sin, ẹsẹ̀ rẹ̀ ti yọọ́ lẹ̀

[The corpse that you buried, the legs are outside]

Unlike previous proverbs examined, this is used to start an interaction where Lápitẹ́ uses the proverb to bring a burning issue to Balógun's awareness. Prior to this time, Balógun had executed an important mission for Lápitẹ́ which Lápitẹ́ later discovers wasn't efficiently accomplished leading to very bad consequences. Thus, as the interaction begins between both of them, Lápitẹ́ uses the proverb to inform Balógun of a serious problem at the moment relating to the work he was delegated to do.

Here, the proverb is used as a strategy of informing in an interaction.This also reveals that proverbs are used by the Yorùbás for initiating interaction especially on very important issues and not only during interaction. In another instance in Agogo Eèwọ̀:

Setting: At Bàbá Ọ̀pálábá's place in Agogo Eèwọ̀, he uses the proverb:

Àṣẹ̀ṣẹ̀ jáde akàn ni, a ò mọ ibi tí ń lọ̀

[The early coming out of a crab, we do not know where it is heading]

This proverb is used to inform his children in the city, who had been asking about the nature of things and whether they can pay him a visit, that things have not really improved. And, the new leadership of the town is just beginning and still struggling to bring any reasonable development. Thus, instead of saying very simply what is going on in the community and describe all the activities of the new leadership, he uses a proverb to inform his children about the state of things in the town. Very succintly, through the proverb, he conveys his message to them. Notably, proverbs help to summarise events and happenings in a more concise way to the intended audience. This is also why they are more condensed semantically because they are shorter structurally. It is trying to give an explanation that could take a paragraph in a sentence.

Setting: After an official meeting with the king in Agogo Eèwọ̀, one of the wood merchants uses the proverb:

Ìjẹ mùmu tájá tẹran ti bùse

[The eating period of dogs and goats are over]

To notify the chiefs that the usual relationship of sharing money between both parties can no longer hold. With the coming of a new leadership of transparency, they can no work with the corrupt chiefs and that all previous dubious deals and negotiations are over. The proverb is used to inform the chief about the new state of things. In another instance in Agogo Eèwọ̀, the proverb is also used give information.

Setting: At the Ọba's room in Agogo Eèwọ̀, during an interaction between the disturbed king and his wife on the bad behavior of the town chiefs. The olorì said:

Olorì kékeré's: Ẹran tí ò yi ò wọ́bẹ; igi tó bá ń ṣèéfí a sì yọọ́ gbó

[The unyielding meat doesn't need a knife; a bad stick should be thrown into the bush]

The queen informs the king on how to curb the nonchalant attitude of the chiefs. She told the king to send the chiefs away so that he can achieve his good plans and purposes for the town. She sees no reason why the king should be troubled over the chiefs' issue which she sees to be a very simple problem. She therefore uses the proverb to inform the king about a solution to the problem. Thus, the metaphor of the unyielding meat and bad stick relate to the uncooperative chiefs who are to be disposed.

The discussion of various discourse acts unfolds that proverbs enhance discourse coherence in Yorùbá interactions and they are not only used during interaction but also as a strategy for initiating interaction among the Yorùbás. These acts include warning, encouraging, informing, asserting, explaining, and so on. It should be noted, however, that proverbs are interpretable in discourse only within contexts. Context is fundamental to understanding the proverbs and this context can be categorized into three. First is the context of situation which is the physical situation of the conversation between interlocutors. Second, is the context of culture which relates to the shared cultural beliefs and norms between the speakers. When using proverbs, speakers often orient to a particular mutual cultural background. Third, is the linguistic context in terms of what is said before and after the proverb. These variables provide cues to decoding proverbial meanings. More importantly, it is instantiated that proverbs are used in the negotiation of different speaker goals and intentions during interation.

Indirectness and Circumstantiality in Yorùbá Proverbs

Circumstantial expressions are governed by a wider range of contextual variables including social and physical circumstances, attitudes, identities, beliefs, and relations existing between speakers (Traugott & Pratt, 1980). These utterances therefore orient to the deep congruity between language, culture, and the immediate environment of a particular discourse (Malinoskwi, 1926).

Characteristically, these proverbs make use of objects and animals analogies to indirectly convey very sensitive messages.

Bí bá jẹ ẹyin tirẹ̀, kí ni ó máa ṣe sí ti aláǹgbá

[If the crocodile eats its own eggs, what does it do to those of the lizard?]

The proverb condemns greediness and convetous acts of people of position and social status. The crocodile and the lizard are used to conceptualize ideas and issues in the society.

Bí àkùkọ kò bá fẹ́ kọ, ṣé ó máa wá sí ìdí lẹ̀kùn

[If the fowl did not intend to roost would it have come to the door post?]

The proverb is indirectly used to urge one to carry out one's responsibility as a member of a community especially if one is hesistant to take responsibilities. It also used to motivate or enjoin one into taking immediate action

Bí aláǹgbá bá ń gé ni jẹ, ṣe a kò ní bẹ̀rù

[If a lizard bites, will you not fear the crocodile?]

The analogy here is that of a lizard and a crocodile. While both of them are reptiles, the crocodile is bigger and more dangerous than a lizard. The proverb is indirectly used to threaten a person to be aware of a greater danger ahead especially if a potential action is taken. It also used to caution a stubborn person who tries to engage in something which has greater risks than the previous one.

Bí a bá pe òjò búburú sí orí ọ̀tá ẹni, ọ̀rẹ́ ẹni ńkọ́?

[If you call a very bad rain upon your enemy, what about your friend?]

Àparò kan kòga jùkan à fi èyí tóbá gun orí ebè

[No parrot is greater than the other, only the one that climbs on a heap]

The proverb cautions against taking desperate indiscriminate actions since they could also bring negative consequences. It enjoins people to put their trust in God. While the second proverb reveals the place of equality and opportunity.

Obìnrin bímọ fún ara rẹ̀, ó ní òun bímọ f'ọ́kọ; tani ò ṣàì mọ̀ pé òrìsà bí ìyá kò sí

[A woman gives birth for her sake, but proclaims to have had a child for the husband; who does not know that there is no idol like the mother]

This is an indirect way of acknowledging the power and significance of the woman. It endorses how influential the role of the woman is in the society.

A ní kí oun tó wuni ó wá, oun tó dára ń yọjú; tó bá dára, tí ò bá wuni ńkọ́?

[We requested for something pleasing but something good came; what if that which is good is not pleasing?]

This is used when making judgements and evaluations. Also, when people are making decisions on what they want or not. The following are other examples of such proverbs:

Bí a bá gún iyán sínú odó, tí a sebẹ̀ sínú èpo ẹ̀pà; ẹni máa yó, máa yó

[If pounded yam is served in a mortar and soup is served in groundnut shell, he who will be filled will be filled]

Bí alágbẹ̀dẹ bá ń lu irin ní ojú kan tí kò jáwọ́, ó ní ìdí

[If the blacksmith keeps beating the iron in a place, it's because there is a reason]

Bí o ṣe wù kí ìrùngbọ̀n alágbàro ṣe gùn tó, ẹni tó gbọ́kọ́ fun l'ọ̀gá rẹ̀

[No matter how big the beard of the hireling is, the hirer remains his master]

Ohun tó ṣ'àkàlàmàgbò to fi dẹ́kùn ẹ̀rín rín; tó bá ṣe igúnnugún, a wọnkoko mọ́ri ẹyin

[What took away the vulture's smile, will keep the raven firmly nested over her eggs]

These proverbs possess the basic feature of indirectness. Referential objects and allusions are used to conceptualize ideas. Therefore, the message of each proverb may not be readily available on the surface level of the proverbs. For instance, the last proverb uses the metaphor of the vulture and the raven to convey a central message. This is a basic feature of indirectness in the proverb accounts for its deep semantic content. Its lack of easy lucidity and clarity however has also been appropriated by some speakers who use it to communicate secret and personal issues at the expense of others knowledge.

Discourse Structure of Yorùbá Proverbs

Certain processes which can be identified as both lexical and grammatical devices are used to enhance cohesive relations in a discourse (Halliday, 1978; Osisanwo 2003). According to them, the lexical devices bring lexical cohesion while grammatical devices achieve grammatical cohesion. This chapter explores the discourse structure of Yorùbá proverbs to highlight the common linguistic processes employed in Yorùbá proverbs. It is argued that these processes help to reinforce the textuality and intelligibility of the proverbs. This section argues that these proverbs are not just meaningful on their own. Certain linguistic processes are deployed in their formation and construction. These linguistic processes are classified into lexical and syntactic processes. The lexical process relates to words and lexemes and often operates at the word level. The syntactic process on the other hand, captures the grammatical features which manifest at the sentential level.

Lexical Procceses in Yorùbá Proverbs

This entails making use of the characteristics and features of words as well as the group relationships among them. There are two main types which are repetition and collocation that are identified in the proverbs.

Reiteration

This implies saying or doing something several times and it often involves the use of repetition and hyponyms in the structure of the proverbs

(a) Repetition

Ijó tó bá ka ni l'ára la ń di ẹsẹ̀ jó

[It is the dance that excites one that one dances with a tight fist]

Ìdí ni ikú ìgbín; Orí ni ikú awun

[The bottom lies the death of the snail; the head lies the death of the turtle]

Òjò kò bẹ́nìkan ṣọ̀rẹ́; Ẹni òjò bá ni òjò ń pa

[The rain befriends no one; the rain beats whoever the rain meets]

Tí ojú bá pọ́n àgàn, àgàn á tọrọ àbíkú

[When the barren becomes desperate, she will pray for even a born-soon-to-die child]

Èyí ò tofo èyí ò tofo, fìlà imole ku pereki

[It doesn't matter, it doesn't matter; yet reduces the kufi to a minimum]

Ẹni à ń wò, kì í wòran

[He that we look up too, does not look away]

Ẹyẹ kò dédé bà ló rùle, ọ̀rọ̀ ní ẹyẹ ń gbọ́

[The bird does not perch on the roof, it is information that the bird gathers]

Here, the words 'ijo' (dance), ikú (death), òjò (rain), àgàn (barren), wò (look), ẹyẹ (bird) are repeated in each text. This is done to show lexical cohesion and also helps to achieve reinforcement. This lexical device helps to drive home the point of the proverbs. Thus, we can say the proverbs are lexically cohesive.

(b) Hypernym-Hyponym

Ilé tó dáhoro ń kánjú, pẹ̀tẹ́ẹ̀sì gàgàrà ń bọ̀wá di ilẹ̀ẹ́lẹ̀

[A desolate house is in a hurry, even the skyscraper will become bare-ground]

Here, the word 'ilé' (house) is a hypernym under which we have 'pẹ̀tẹ́ẹ̀sì' (skyscraper) are used to indicate lexical relationship in the first proverb. In this example, the concept of ilé is also reiterated pẹ̀tẹ́ẹ̀sì. This kind of lexical relationship has been utilized to foreground the idea of status which is a central issue the proverb addresses. Lexical process helps to bring to the fore the true implication of the proverb more vividly.

Collocation

Colocation occurs when words co-occur together in a discourse. This implies that the mention of one easily brings to mind the other one. For instance in an event, when the speaker says, 'ladies and ...' what comes to mind easily is the word 'gentlemen.' Collocation is another device of achieving lexical cohesion in Yorùbá proverbs which is explained below.

a) Converses

Ìdúrọ́ kò sí, ìbẹ̀rẹ̀ kò sí f'ẹ́ni tó gbódó mì

[There is neither standing nor bending for one who has swallowed a mortar]

b) Complementaries

Bí ọmọ kò bá jọ ṣòkòtò yóò jọ kìjìpá

[If the child does not resemble the father, he will resemble the mother]

Bí òwe bí òwe là ń lùlù ògìdìgbó

Ọlọ́gbọ́n níí jó o, ọ̀mọ̀ràn níí mọ̀ ọ

[The war drum is beaten like a proverb, it is the wise that dance to it, it is the informed that know it]

c) Co-hyponyms

Àjèjé ọwọ́ kan kò gbégbá dé orí

[A single hand does not carry a whole calabash to the head]

Ọwọ́ ọmọdé kan kò tó pẹ́pẹ́, ti àgbà kò wọ kèrègbè

[The child's hands do not reach a high shelf; those of the elder do not enter a gourd] Ẹni rù erin lórí kò gbọ́dọ̀ fi ẹsẹ̀ tan ìrẹ̀ nílẹ̀.

[One who carries an elephant on his head should not dig for a cricket with his foot]

Akì í gbin àlùbọ́sà kà hu ẹ̀fọ́, ohun tí ènìyàn bá gbìn ni yóò ká

[You cannot sow onions and reap vegetables, whatsoever a man sows he shall reap]

Ohun tó ṣ'àkàlàmàgbò to fi dẹ́kùn ẹ̀rín rín; tó bá ṣe igúnnugún, a wọnkoko mọ́ri ẹyin

[What took away the vulture's smile, will keep the raven firmly nested over her eggs]

In the above examples, we see other kinds of lexical relationships that are achieved in Yorùbá proverbs. Under converses, the word 'ìdúró' and 'ìbẹ̀rẹ̀' relate to each other, 'sòkòtò' and 'kijipa' operate as a case of complementarity. Similarly, is 'òṣì' and 'owó,' 'ẹrú' and 'ọmọ.' In the final examples, 'ọwọ́' and 'orí,' 'ọmọdé' and 'àgbà' are used as co-hyponyms. Also, 'àlùbọ́sà' and 'ẹ̀fọ́' are both plants. Thus, they are co-hyponyms of plants. On the other hand, 'àkàlàmàgbò' and 'igúnnugún' are hyponyms of animals. These lexical processes help to reinforce the true implication of the proverbs more vividly.

Antonyms and Opposites

Antonymy is used to indicate disparity in meaning and concepts. Thus, antonymic lexemes show differences in senses in terms of other words. This is a very common lexical feature in Yorùbá proverbs.

Ibi tí múnimúni wà, ibẹ̀ ni gbanigbani wà

[where there are captors, there are rescuers]

Òṣì níí jẹ́ táni mọ̀ ẹ́ rí, owó níí jẹ́ mo bá ẹ tan,

[poverty is not wanted but wealth is desired by all]

Àti sọ ẹrú d'ọmọ, kì í ṣe iṣẹ́ òòjọ́

[For a slave to become a son, it is not a day's job]

Oppositeness is reflected in each of the proverb above, the word 'múnimúni' opposes 'gbanigbani', while 'òṣì' contradicts 'owó,' they both function as opposites. Opposite lexemes are used in the proverbs to express different views and perspectives. It is a way of comparing to concepts with the aim of showing contrast and contradiction.

Syntactic Features in Yorùbá Proverbs

This relates to the use of sentential elements to realize cohesion in discourse. These devices are examined in Yorùbá proverbs.

Substitution

Substitution entails replacing an element which could be a word, group or a clause with another one in the next clause or sentence.

i) A ti fi òjé bọ olórìṣà lọ́wọ́, ó ku ẹni tí yóo bọ

[The lead ring has been worn for the idolator, it remains who will remove it]

ii) Bí onírèsé kò bá tilẹ̀ fín igbá mọ́, èyí tó ti fín sílẹ̀ kò ní parun

[If the potter does not engrave any calabash again, the ones he had engraved will never be destroyed]

In the first discourse, 'òjé' in the first part is substituted or replaced by 'o' in the second part. Also, in the second proverb, 'igbá' is substituted by 'èyí 'in the second part. This kind of substitution can be referred to as nominal substitution since the items substituted in the proverbs are nouns.

Ellipsis

Ellipsis simply means deletion. In this case, syntactic elements are deleted to make room for grammatical cohesion in the proverbs.

i) Èrò lọ́ bẹ̀ẹ gbẹ̀gìrì, bí a kò bá rò ó, kò ní ki

[The bean soup has to be stirred, if not stirred, it will not be thick]

Here, the use of 'bí a kò bá rò ó' (if not stirred) indicates ellipsis or deletion. Ordinarily, the whole expression should be:

Èrò lọ́ bẹ̀ẹ gbẹ̀gìrì, bí a kò bá rò ọbẹ̀ gbẹ̀gìrì, kò ní ki

[The bean soup has to be stirred, if the bean soup is not stirred, it will not be thick]

Thus, the use of 'bí a kò bá rò ó' only in the second part of the proverb indicate the deletion of the other part-'bẹ̀ẹ gbẹ̀gìrì'

Syllable Lengthening

There is occasional lengthening of syllables that are usually short in everyday speech. Eg.

Èrò lọ́ bẹ̀ẹ gbẹ̀gìrì, bí a kò bá rò ọbẹ̀ gbẹ̀gìrì, kò ní ki

[The bean soup has to be stirred, if the bean soup is not stirred, it will not be thick]

In the first phrase of the sentence, there is the word ọbẹ̀, but it is elongated in the second syllable as 'ọ́bẹ̀ẹ.' This is sometimes a rhetorical strategy to provide a rhythmic coloration to the proverbs.

Conjunction

This entails the use of conjuncts such as ká, ká tún (and), kató (before), ṣùgbọ́n (but) in the proverbs.

i) A kìí lóyún sínú ká fi bí ẹrú

[We do not get pregnant and give birth to a slave]

ii) A kìí gbin àlùbọ́sà ká hu ẹ̀fọ́

[We do not sow onions and reap vegetables]

iii) Kálé akata lọ tán kátó wá fi àbọ̀ bá adìẹ

[Let's drive away the fox first before we come back to the fowl]

In the Yorùbá proverbs given above, the underlined words are conjunctions and they perform a cohesive role. For instance, in ii), the conjunct 'ká' merges the expression 'A kìí gbin àlùbọ́sà' with 'hu ẹ̀fọ́.' Similarly, in iii), the conjunction 'kátó' merges the expression 'kálé akata lọ tán' with 'wá fi àbọ̀ bá adìẹ.' The use of this device of conjunction can be found in many other Yorùbá proverbs. In most cases, Yorùbá conjunctions such as ká, kátó, kátún are deployed. These conjunctions help to bring intelligibilty and textuality to the proverbs. In terms of textuality, these conjunctions help to unite the fragments within a proverb. Intelligibility is seen in the sense that these conjunctions give a cause and effect relation in the proverb. That is something is done to realize the other part. In example i) for instance, 'A kìí lóyún sínú' is the cause while 'bí ẹrú' represents an effect. Structurally, these conjunctions also function in the process of generating compound and complex proverbs. These are proverbs with expanded sentences and extended meanings.

Conclusion

This paper has attempted to explore Yorùbá proverbs from a formal and functional perspective. It reveals that Yorùbá proverbs are structurally marked by certain lexical and grammatical devices that reinforce their coherence and cohesiveness in communication. Lexical devices including reiteration and collocation, and grammatical devices including substitution, ellipsis, and conjunction operate significantly in the formation of the proverbs. Yorùbá proverbs are not just formed or structured arbitrarily, but they possess a unique structure. This paper underscores that understanding the syntax of the proverbs is important and could also aid a fruitful interpretation of their meaning. The lexico-syntactic processes furnish the proverbs with not only stylistic neatness but discourse coherence and cohesion. Furthermore, through the discourse acts in the proverbs, it indicates that proverbs are deployed for multidimensional purposes in interactions: for illustrating a point, negating or supporting arguments, for instruction, information, and inspiration. They are used to facilitate effective communication and interaction. Yorùbá proverbs are not only just a significant part of the daily life of the Yorùbá people, they constitute a rich integral part of the linguistic repertoire of the speech community.

References

Arewa, E. O., & Dundes, A. (1967). Proverbs and the ethnography of speaking folklore. American Anthropologist, 66(6), 70-85.

Bámgbósé, A. (1968). The form of Yoruba proverbs. ODU: A Journal of West African Studies, 4(2): 74-86.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ehineni, T. O. (forthcoming). The pragmatics of Yorùbá proverbs in Yerima's Igatibi, Ajagunmale and Mojagbe. Issues in Intercultural Communication.

Fasiku, G. (2006). Yoruba proverbs, names and national consciousness. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 1(4), 50-63.

Finnegan, R. (1970). Oral literature in Africa. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hallen, B. (2000). The good, the bad and the beautiful: Discourse about values in Yoruba culture: Bloomington: Indiana UP.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Herzog, G. (1936). Jabo proverbs from Liberia: Maxims in the life of a native tribe. London: Oxford University Press.

Kelani, T. (1999). Saworoidẹ. Lagos: Mainframe productions.

Kelani, T. (2000). Agogo Èèwọ̀. Lagos: Mainframe Productions.

Malinowski, B. (1926). Myth in primitive psychology. London: Norton.

Obeng, S. (1994). Proverb as mitigating strategy in Akan discourse. Anthropological Linguistics, 38(3), 521-549.

Okpewho, I. (1992). African oral literature. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Olatunji O. (1984). Features of Yoruba oral poetry. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press, Ltd.

Osisanwo, W. (2003). Introduction to discourse analysis and pragmatics. Lagos: Ebute Meta.

Owomoyela, O. (1981). Proverbs: Exploration of an African philosophy of social communication, Basiru, 12(1), 3-16.

Owomoyela, O. (2005). Yorùbá Proverbs. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Traugott, E. C., & Pratt, M. L. (1980). Linguistics for students of literature. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc.

Yankah K. (1986). Proverb rhetoric and African judicial processes: The untold story. Journal of American Folklore, 99(393), 280–303. .

Yankah, K. (1989). The proverb in the context of Akan rhetoric. A theory of proverb praxis. New York: Diasporic African Press.

Métricas

Licencia

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/