DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.17373Publicado:

2022-04-22Número:

Vol. 24 Núm. 1 (2022): Enero-junioSección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónTeacher Education for Language Assessment and Testing: Postgraduate Program Evaluation from its Students’ Perspective

Formación docente para la valoración y el examen en idiomas: evaluación en un programa de posgrado desde la perspectiva de sus estudiantes

Palabras clave:

computer-assisted language assessment and testing, language assessment and testing, online teacher education, teacher education, students’ perspective (en).Palabras clave:

evaluación de idiomas asistida por computadora, evaluación y pruebas de idiomas, formación docente en línea, formación docente, perspectiva de los estudiantes (es).Descargas

Referencias

Babbie, E. (1990). Survey research methods (2nd ed.). Wadsworth.

Bachman, L. F. (2000). Modern language testing at the turn of the century: Assuring that what we count counts. Language Testing, 17(1), 1-42. https://doi.org/10.1177/026553220001700101 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/026553220001700101

Bailey, K. M., & Brown, J. D. (1996). Language testing courses: What are they? In A. Cumming & R. Berwick (Eds.), Validation in language testing (pp. 236-256). Multi-lingual Matters.

Boyles, P. (2006). Assessment literacy. In M. Rosenbusch (Ed.), New visions in action: National Assessment Summit papers (pp. 18-23). Iowa State University.

Brindley, G. (2001). Language assessment and professional development. In A. B. C. Elder (Ed.) Experimenting with Uncertainty Essays in Honour of Alan Davies (126-136). Cambridge University Press.

Brown, J. D., & Bailey, K. M. (2008). Language testing courses: What are they in 2007? Language Testing, 25(3), 349–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532208090157 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532208090157

Chapelle, C. A., & Douglas, D. (2006). Assessing language through computer technology. Cambridge University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511733116

Cheng, L., Rogers, T., & Hu, H. (2001). An investigation of ESL/EFL teachers’ classroom assessment practices. Language Testing, 21(3), 380-369. https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532204lt288oa DOI: https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532204lt288oa

Coombe, C., Troudi, S., & Al-Hamly, M. (2012). Foreign and second language teacher assessment literacy: Issues, challenges, and recommendations. In C. Coombe, P. Davidson, B. O’Sullivan, & S. Stoynoff (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language assessment (pp. 20-29). Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Csépes, I. (2014). Language assessment literacy in English teacher training programmers in Hungary. In J. Horváth & P. Medgyes (Eds.), Studies in honour of Nikolov Marianne (pp. 399–411). Lingua Franca Csoport.

Deneen, C. C., & Brown, G. T. L. (2016). The impact of conceptions of assessment on assessment literacy in a teacher education program. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1225380. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1225380 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1225380

Davies, A. (2008). Textbook trends in teaching language testing. Language Testing, 25(3), 327-347 https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532208090156 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532208090156

Farhady, H. (2018). History of Language Testing and Assessment. The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0343 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0343

Fulcher, G. (2012). Assessment literacy for the language classroom. Language Assessment Quarterly, 9(2), 113-132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2011.642041 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2011.642041

Ghaicha, A. (2016). Theoretical Framework for Educational Assessment: A Synoptic Review. Journal of Education and Pratice, 7(24), 212-231. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1112912

Giraldo, F. (2018). Language assessment literacy: Implications for language teachers. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(1), 179-195. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n1.62089 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n1.62089

Giraldo, F., & Murcia, D. (2018). Language Assessment Literacy for Preservice Teachers: Course Expectations from Different Stakeholders. GiST Education and Learning Research Journal, 16, 56-77. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.425 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.425

Hadigol, M, & Kolobandy, A. (2019). Factors affecting consumer acceptance of mobile banking in Tejarat Bank in city of Karaj, Iran. Journal of Management and Accounting Studies, 7(3), 30-35. https://doi.org/10.24200/jmas.vol7iss03pp30-35 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24200/jmas.vol7iss03pp30-35

Hatipoğlu, Ç. (2015). English language testing and evaluation (ELTE) training in Turkey: expectations and needs of pre-service English language teachers. ELT Research Journal, 4(2), 111-128. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/eltrj/issue/28780/308006

Herrera, L. & Macías, D. (2015). A call for language assessment literacy in the education and development of teachers of English as a foreign language. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 302-312. https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a09 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a09

Inbar-Lourie, O. (2008). Constructing a language assessment knowledge base: A focus on language assessment courses. Language Testing, 25(3), 385-402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532208090158 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532208090158

Inbar-Lourie O. (2017) Language Assessment Literacy. In E. Shohamy, I. Or, S. May (Eds.), Language Testing and Assessment. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, (3rd ed., pp. 257-270). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02261-1_19 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02261-1_19

Infante, P., & Poehner, M. (2019). Realizing the ZPD in Second Language Education: The Complementary Contributions of Dynamic Assessment and Mediated Development. Language and Sociocultural Theory, 6(1), 63-91. https://doi.org/10.1558/lst.38916 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1558/lst.38916

Jeong, H. (2013). Defining assessment literacy: Is it different for language testers and non-language testers? Language Testing, 30(3), 345-362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532213480334 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532213480334

Jin, Y. (2010). The place of language testing and assessment in the professional preparation of foreign language teachers in China. Language Testing 27(4) 555-584 https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532209351431 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532209351431

Kalajahi, S. A. R., & Abdullah, A. N. (2016). Assessing Assessment Literacy and Practices among Lecturers. Pedagogika, 124(4), 232-248. https://doi.org/10.15823/p.2016.65 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15823/p.2016.65

Kleinsasser, R. C. (2005). Transforming a postgraduate level assessment course: A second language teacher educator’s narrative. Prospect, 20, 77-102. http://www.ameprc.mq.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/229812/20_3_6_Kleinsasser.pdf

Lam, R. (2015). Language assessment training in Hong Kong: Implications for language assessment literacy. Language Testing, 32(2), 169-197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532214554321 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532214554321

Language Assessment. (2020, August 21). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Language_assessment

Looney, A., Cumming, J., Kleij, F. v. D., & Harris, K. (2017). Reconceptualising the role of teachers as assessors: teacher assessment identity. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 25(5) 442-467. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2016.1268090 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2016.1268090

López M.A. A., Bernal, A., R. (2009). Language testing in Colombia: A call for more teacher education and teacher training in language assessment. PROFILE, 11(2), 55-70. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/11442/12093

Malone, M. (2008). Training in language assessment. In E. Shohamy & N. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education: language testing and assessment (2nd ed., vol. 7, pp. 225-239). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-0-387-30424-3_178 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30424-3_178

Malone, M. (2011). Assessment literacy for language educators. CALDigest, October, pp. 1-2.

Malone, M. E. (2013). The essentials of assessment literacy: Contrasts between testers and users. Language Testing, 30(3), 329-344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532213480129 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532213480129

Mede, E. & Atay, D. (2017). English Language Teachers Assessment Literacy: The Turkish Context. Dil Dergisi, 168(1), 43-60. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12575/62697 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1501/Dilder_0000000237

Nesbary, D. K. (2000). Survey research and the world wide web. Allyn & Bacon.

Nimehchisalem, V., & Bhatti, N. (2019). A Review of Literature on Language Assessment Literacy in last two decades (1999-2018). International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 8(11), 44-59. https://www.ijicc.net/images/vol8iss11/81104_Nimehchisalem_2019_E_R.pdf

O’Loughlin, K. (2013). Developing the assessment literacy of university proficiency test users. Language Testing, 30(3), 363-380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532213480336 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532213480336

Pehlivan Şişman, E. & Büyükkarci, K. (2019). A Review of Foreign Language Teachers’ Assessment Literacy. Sakarya University Journal of Education, 9(3), 628-650. https://doi.org/10.19126/suje.621319 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19126/suje.621319

Scarino, A. (2013). Language assessment literacy as self-awareness: understanding the role of interpretation in assessment and in teacher learning. Language Testing, 30(3), 309-327 https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532213480128 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532213480128

Spolsky, B. (1995). Measured words: The development of objective language testing. Oxford University Press.

Spolsky, B. (2017). History of Language Testing. In S. May (Ed.), Language Testing and Assessment, Encyclopedia of Language and Education (3rd ed.). (pp. 375-384). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02261-1_32 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02261-1_32

Stiggins, R. J., & Conklin, N. F. (1992). In teachers’ hands: Investigating the practices of classroom assessment. State University of New York Press.

Stiggins, R. J. (2002). Assessment crisis: the absence of assessment for learning. http://electronicportfolios.org/afl/Stiggins-AssessmentCrisis.pdf DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170208301010

Sue. V. M., & Ritter, L. A. (2007). Conducting online surveys. Sage. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412983754

Sultana, N. (2019). Language assessment literacy: an uncharted area for the English language teachers in Bangladesh. Language Testing in Asia, 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-019-0077-8 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-019-0077-8

Taylor, L. (2013). Communicating the theory, practice and principles of language testing to test stakeholders: Some reflections. Language Testing, 30(3), 403-412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532213480338 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532213480338

Tsagari, D., & Vogt, K. (2017). Assessment literacy of foreign language teachers around Europe: research, challenges and future prospects. Papers in Language Testing and Assessment, 6(1), 41-63. https://arts.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/2349928/6_1_SI3TsagariVogt.pdf

Vogt, K., & Tsagari, D. (2014). Assessment Literacy of Foreign Language Teachers: Findings of a European Study. Language Assessment Quarterly, 11(4), 374-402. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2014.960046 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2014.960046

Volante, L., & Fazio, X. (2007). Exploring teacher candidates’ assessment literacy: implications for teacher education reform and professional development. Canadian Journal of Education, 30(3), 749-770. https://doi.org/10.2307/20466661 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/20466661

Webb, N.L. (2002). Assessment literacy in a standards-based urban education setting [Conference presentation]. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, Luisiana April 1-5, United States.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Recibido: 15 de diciembre de 2020; Aceptado: 23 de noviembre de 2021

Abstract

A review of research conducted on language assessment teacher education (TE) revealed a lack of studies focused on the participants’ perspective. This work concentrates on the evaluation of an online computer-assisted language assessment and testing (CALAT) TE program offered for four consecutive years. The research was based on a conceptual, multidimensional e-learning evaluation model. The data were obtained from 19 practicing language teachers who attended the MA in Computer-Assisted Language Learning via an online anonymous survey focused on 1) the participants’ engagement; 2) course organization, teaching mode, and materials; 3) course strengths; 4) course aspects most helpful for learning; and 5) course aspects that constituted obstacles for learning. The results indicate the participants’ positive attitude towards the course; they highlighted that their knowledge, skills, and principles had improved, as well as the constructivist instructional design and the organization, teaching modes, and materials of the course, which motivated them and involved them in active interaction and collaboration. The participants also perceived the assessment practices performed during the course in a positive way, which favored their learning and teaching practice within the classroom. The results also include some recommendations for course improvement.

Keywords

computer-assisted language assessment and testing, language assessment and testing, online teacher education, teacher education, students’ perspective.Resumen

Una revisión de investigaciones sobre formación docente (FD) en evaluación de idiomas reveló la ausencia de estudios centrados en la perspectiva del estudiante. Este trabajo se centra en la evaluación de un programa de FD sobre evaluación y pruebas de lenguaje asistidas por computadora (CALAT) realizado en línea y ofrecido durante cuatro años consecutivos. La investigación se basó en un modelo de evaluación conceptual multidimensional de e-learning. Los datos fueron obtenidos de 19 estudiantes de posgrado, que cursaban el Master en Aprendizaje de Idiomas Asistido por Computadora, a través de una encuesta anónima en línea a centrada en (i) el compromiso de los participantes; (ii) la organización, modalidad de enseñanza y materiales del curso; (iii) las fortalezas del curso; (iv) los aspectos del curso más útiles para el aprendizaje; y (v) los aspectos del curso que constituían obstáculos para el aprendizaje. Los resultados indican una percepción positiva de los participantes hacia el curso; destacaron que habían mejorado sus conocimientos, habilidades y principios, al tiempo que destacaron el diseño instruccional constructivista y la organización, la metodología y materiales de enseñanza del curso, lo que los motivó e involucró en interacción y colaboración activas. Los participantes también percibieron positivamente las prácticas de evaluación realizadas durante el curso, lo cual favoreció su aprendizaje y su labor docente en el aula. Los resultados también contemplan algunas recomendaciones para la mejora del curso.

Palabras clave

evaluación de idiomas asistida por computadora, evaluación y pruebas de idiomas, formación docente en línea, formación docente, perspectiva de los estudiantes.Introduction

In the fast-growing, globalized world, the existence of LAT TE training programs, which can efficiently and appropriately train language educators on how to assess their student’s language competence has become crucial. The development in learning theories and practices, as well as their effect on language learning TE, has resulted in similar developments in LAT and training. Assessment includes not only summative assessment, which occurs at the end of a unit or a chapter, or a period of time such as a week, semester, or year, and has the form of a test, examination, or external high stakes examination; but also formative assessment (FA), which occurs during the learning process, in class, and in different forms such as quizzes, feedback, projects, presentations, group activities, ePortfolios, and games. More stakeholders beyond testing experts, such as the instructors and the students, are taken into consideration within the process of improving theories and practices. Research includes other areas beyond summative assessment.

Many researchers have explored LAT aspects, which are believed to be addressed in LAT teacher training programs. For example, Stiggins and Conklin (1992), Inbar-Lourie (2008), Malone (2008), Taylor (2013), Fulcher (2012), Lam (2015) , and Nimehchisalem and Bhatti (2019) focused on the definition of language assessment literacy (LAL) and supported that it should be part of the content of a LAT teacher training program. Boyles (2005) identified the need to develop assessment literacy (AL) in foreign language (FL) teachers as part of LAT TE programs. She saw professional development as priority. To the same effect, Giraldo (2018) proposed a list of LAL dimensions, and Giraldo (2018) a set of descriptors for those dimensions. Jeong (2013) discussed the content of LAT courses regarding LAL. López and Bernal (2009), Scarino (2013), and Tsagari and Vogt (2017) highlighted the need for LAL TE. Going a step further, Bailey and Brown (1996), Kleinsasser (2005), Malone (2013) , and Jeong (2013) also identified the importance of different stakeholders’ perceptions of LAT TE courses.

Research has indicated that most studies on stakeholders still focus mainly on the experts’ views, as well as some on instructors’ perceptions. There is a need for more research on language teaching practitioners’ views ( Deneen and Brown, 2016 ) and also a need to include the perspectives of LAT course participants and LAT TE course evaluation.

This study evaluates a Computer-Assisted Language Assessment and Testing (CALAT) Teacher Education (TE) module of a Master’s program in Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) from the course participants’ perspective. The students were all practicing language teachers. The design was based on an analysis of the students’ needs and on research in the area of LAL and constructivist online instructional design and delivery. The study examines the students’ evaluation of aspects such as their engagement in the course, the course content (organization, teaching delivery mode, which was based on constructivism and online mode of delivery, and materials), course strengths, helpful aspects, and obstacles for learning. The evaluation of LAT courses from the perspective of its students has not been adequately researched, which is why it must be addressed.

Background

Language assessment and testing (LAT)

The history of LAT has been recorded by researchers such as Spolsky (1995, 2017) and Farhady (2018) . As for the history of testing, Spolsky (2017) said that, looking back over the last halfcentury, LAT has developed into an identifiable academic field, as well as into a major industry. Through most of its history, it was practiced mainly in the form of summative assessment, that is, inclass tests and final class-based tests or external examinations ( Spolsky, 2017. Farhady, 2018 ). With technological development, testing also moved on from pen and paper to different forms of ComputerBased Tests (CBT), including Computer Adaptive Tests (CAT) ( Chapelle and Douglas, 2006 ).

In recent years, there has been an interest and focus on FA, conducted in different forms such as projects, presentations, group activities, ePortfolios, and games ( Stiggins, 2002 ). With all these developments, it was of utmost importance to define language teachers’ LAL and LAL competences, as well as the way in which these are reflected on LAT TE courses. However, although research has been conducted in different aspects related to teacher LAL and training, not much has been done so far in finding how this training is perceived by one of its major stakeholders, that of the students who take the TE course.

Language assessment literacy (LAL): definition and competences

There has been much debate on defining LAL and developing a common framework of what LAL entails. The aim was for this definition to constitute part of training programs and the repertoire of language teachers’ assessment and testing practices.

According to Webb (2002, p. 3) , “Assessment Literacy is defined as the knowledge of how to assess what students know and can do, interpret the results of these assessments, and apply these results to improve student learning and program effectiveness”. LAL broadly refers to what language teachers and other stakeholders need to know about language assessment matters and activities ( Stiggins and Conklin, 1992. Inbar-Lourie, 2008. Malone, 2008. Taylor, 2013. Fulcher, 2012. Jeong, 2013. Lam, 2015. Tsagari and Vogt, 2107. Nimehchisalem and Bhatti, 2019). Herrera and Macías (2015, p. 305) added that “High LAL competence should enable EFL teachers to design appropriate assessments, select from a wider repertoire of assessment alternatives, critically examine the impact of standardized tests (e.g., TOEFL, IELTS, etc.), and establish a solid connection between their language teaching approaches and assessment practices”.

Brindley (2001) was one of the first to come up with a LAL framework. It was intended for language teachers and acknowledged their different needs. Together with the proficiency standards, the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001) also introduced and promoted alternative forms of assessment ( Inbar-Lourie, 2017 ), thus influencing LAT TE.

Boyles (2006) defined LAL as an understanding of the principles and practices of testing and assessment in order to be able to analyze them. She recommended the development of “a universal understanding of what constitutes a good assessment and to build a common, articulated set of criteria for exemplary assessments” (p. 22). She supported teacher development and recommended it should be ongoing, both face-to-face and online, and in different contexts such as school districts, professional meetings and Summer Institutes, online professional development, workshops, preservice programs at undergraduate level, and online resources.

Davies (2008) proposed a very useful LAL dimensions core list: knowledge, skills, and principles for language teachers. Giraldo (2018, see p. 186188) expanded on that, and, based on the existing literature ( Coombe et al., 2012. Davies, 2008. Fulcher, 2012. Inbar-Lourie, 2008. Malone, 2013. Scarino, 2013. Taylor, 2013 ), he proposed a set of descriptors for knowledge, skills, and principles in eight dimensions of LAL for language teachers. Researchers such as Jeong (2013) supported that LAL may be different to different stakeholders, for example, language testers and non-language testers. The review of LAL definitions, frameworks, sets of competences, and LAL dimensions and descriptors recorded the development in the area and the debate, which set the background for the LAT course content.

Language assessment course content

As a continuum to the above, other studies focus on examining the content of TE courses to find out whether and how they reflect LAL discussed and suggested by different researchers. Bailey and Brown conducted the first study on LAT courses in 1996. The purpose was to investigate the instructors’ background, the topics covered, and students’ apparent attitudes towards those courses. They repeated this research in 2007 to examine the same characteristics and how such courses may have changed since 1996. The results described the instructors, the course characteristics, and the students, as well as the differences and similarities between the 1996 and 2007 results ( Brown and Bailey, 2008 ). None of these studies reported on course evaluation from the students’ perspective.

In a nationwide survey of 86 instructors, Jin (2010) investigated the training of tertiary level FL teachers in China, focusing on language testing and assessment courses. More specifically, “the results revealed that the courses adequately covered essential aspects of theory and practice of language testing” ( Jin, 2010, p. 555). The teaching content of the different types of courses were similar to a great extent. Suggestions for improvement included highlighting some under-addressed content aspects and setting up a network of teacher-testers for the exchange of experiences, professional knowledge, and skills. Similar to Brown and Bailey’s studies (1996 and 2008), Jin’s study (2010) did not focus on the trainees’ point of view regarding the course.

Acknowledging the different understanding of LAL by FL instructors and language testing experts in the USA, Malone (2013) analyzed how course participants and professional external observers felt about course contents. She concluded that, when it came to preferred content in LAT TE courses, language test experts opted more on theoretical aspects, whereas language teachers opted more for testing tasks.

Giraldo and Murcia (2018) reported on the preliminary findings of their study, which aimed to identify the impact of a LAT course for preservice teachers in a language teaching program in a Colombian state university. Their findings indicated “that there is a need to combine theory and practice of language assessment, with an emphasis on current methodologies for language teaching, assessment in bilingual education, and local policies for assessment” (p. 1). Regarding LAT course content, the gap identified in the research conducted so far was the lack of studies on the view and evaluation of LAT TE courses by LAT TE participating students.

Need for LAL teacher education

Language teachers spend up to a third of their time in assessment-related activities ( Cheng et al., 2001 ). In their language teaching daily practices, they have to deal not only with their own classroombased assessment, but also with standardized language tests ( Mede and Atay, 2017 ). Despite this, most of them “do so with little or no professional training” ( Bachman, 2000, p. 19-20). In addition, most of their knowledge and practice in the area focus on testing and does not include alternative assessment types. Here are some examples of this focus on testing: according to Inbar-Lourie (2017) , there have been two sources which disseminate language testing knowledge, namely language testing textbooks and language testing courses.

In 2008, Davies reviewed language testing textbooks and found that their approach to language testing mainly covered two out of the three core list LAL dimensions he suggested: knowledge and skills, as well as principles to a lesser extent. This was reaffirmed in the case of language testing courses ( Bailey and Brown, 1996. Brown and Bailey, 2008). LAT university courses constitute compulsory or elective courses in graduate and doctoral programs. They are mainly in the area of applied linguistics, English for speakers of other languages, English as a second or FL, educational linguistics, or CALL ( Language Assessment, 2020 ).

Universities worldwide offer regular courses and programs that focus on LAT TE at both PhD and MA levels. In the USA, for example, such programs are offered by the Iowa State University, the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Teachers College, Columbia University, Penn State University, Georgia State University, Northern Arizona University, McGill University, and the University of Toronto. Lancaster University, as well as the Universities of Leicester, Bristol, Cambridge, and Bedfordshire offer such courses in the UK, and, in China, the Guangdong University of Foreign Studies. At the MA level, indicative universities include Lancaster University and University of Leicester in the UK, as well as California State Universities at Fullerton, Los Angeles, Long Beach, San Jose, and San Francisco in the USA ( Language Assessment, 2020 ).

The focus of most such courses has been on summative assessment, most specifically on test development and the different aspects evolving around it:

test development, psychometric qualities of tests, validity, reliability and fairness of tests, washback, and classical true score measurement theory. Others also focus on item response theory, factor analysis, structural equation modelling, G theory, latent growth modelling, qualitative analysis of test performance data such as conversation and discourse analysis, and politics and language policy issues (Language Assessment, 2020).

While more attention has been paid to Davies’ category of principles, there has also been a shift away from a testing-oriented LAL focus ( InbarLourie, 2017 ) to contextually relevant and diverse practices ( Inbar-Lourie, 2008 ) and FA ( Stiggins, 2002 ). At the theoretical level, sociocultural approaches such as Vygotski’s take on language learning and evaluation also had their influence on LAT ( Infante and Poehner, 2019 ). All these were expected to be reflected on LAT TE courses. Moreover, researchers such as Malone (2011) and Purpura and Turner (2013) supported that teaching and assessment should become integrated in order to inform and improve one another.

Although there are language teacher textbooks and training courses, it has been noted that there is also an imbalance between LAT practices at schools and LAT courses at universities, and that teachers’ and lecturers’ training is inadequate ( Jeong, 2013. Lam, 2015. Kalajahi and Abdullah, 2016. Hadigol and Kolobandy, 2019 ). It has also been noted that teachers’ knowledge depends on their assessment identities and is based on their prior experiences, beliefs, and feelings ( Looney et al., 2017 ) rather than their training. The need for LAT training was also raised by other researchers such as Volante and Fazio (2007) and Scarino (2013) .

Pehlivan Şişman and Büyükkarci (2019) noticed that “in the last decades, LAL has been viewed as one of the fundamental competencies of a language teacher” (p. 629). Therefore, more attention has been given to research LAL TE. Research in this regard has attempted to establish LAL TE practices and their impact on language teachers. Findings related to LAT postgraduate studies have been discussed, and other studies have focused on undergraduate programs. In Colombia, for example, López and Bernal (2009) examined teachers’ perceptions about LA and the way they use language assessments in their classroom. They found that there is a significant difference in their perceptions, depending on their level of training in LA. Amongst other findings, they also found that, out of 27 undergraduate programs, only seven of them included a course on evaluation. The authors highlighted the importance of providing adequate LAT TE for all prospective language teachers in Colombia.

Lam (2015) examined LAT TE in five Hong Kong institutions. The findings indicated that LAT training in Hong Kong remains inadequate, as “pre-service teachers are usually ill-prepared to assess their own students owing to inadequate training provided by teacher education programmes” (p. 3). Jeong (2013) examined LAT courses and found significant differences in the topics covered, as well as a difference in the interests of language testers and non-language testers teaching LAT courses. For this reason, Jeong called for a common understanding of LAL among the courses.

Vogt and Tsagari (2014) examined the level of FL teachers in LAL in selected countries across Europe. Their results indicate “that only certain aspects of teachers’ Language testing and assessment expertise are developed” (p. 374). For this reason, teachers tend to learn “on the job or use teaching materials for their assessment purposes” (p. 374). Although priorities varied depending on each country’s educational context, teachers identified the need for training in language testing and assessment aspects.

Tsagari and Vogt (2017) also examined how FL school teachers’ perceived LAL levels in Cyprus, Germany, and Greece. They reported that their sample teachers were not adequately prepared to conduct assessment-related tasks, as these teachers had no training. Sultana (2019) charted the area of LAL for English language teachers in Bangladesh. The study results revealed the teachers’ inadequate academic and professional testing background, a fact that hindered their LAT practices. Sultana made suggestions for the development of LAT awareness of English teachers in Bangladesh.

Nimehchisalem and Bhatti (2019) conducted a literature review on LAL in the last two decades (19992018). This review revealed eight research studies on the topic ( Volante, 2007. Lam, 2015. Deneen and Brown, 2016 , Razavipour et al., 2011; O’Loughlin, 2013. Malone, 2013. Jeong, 2013 ). Nimehchisalem and Bhatti argued that, although there has been more interest in classroom assessment, according to research, many teachers and instructors were not adequately trained when they started teaching. In other words, they did not have the necessary knowledge regarding assessment, which could help them in the development, administration, and interpretation of tests.

Malone (2008) made an effort to define adequate LAT training. To do so, he argued that, in order for it to be adequate, training should include “the necessary content for language instructors to apply what they have learned in the classroom and understand the available resources to supplement their formal training when they enter the classroom” (p. 235). Herrera and Macías (2015) moved on to say that

good practices in EFL assessment should be modelled by teacher educators throughout the programme curriculum, making explicit assessment expertise in the courses. In this way, prospective EFL teachers will recognise the assessment practices teacher educators use and will start building their personal knowledge based on LA as informed by their experiences in EFL TE programmes and by the content of assessment courses. Such a personal knowledge base has the potential to be progressively refined as they advance in their careers as in-service language teachers. (p. 310)

In conclusion, although there has been an increased interest in FA, the focus of most LAT TE programs has so far mainly been on summative assessment. As a result, students and future language practitioners are not adequately prepared for what they are required to deal with in their daily lives as professionals. Although there are LAT courses, as Inbar-Lourie (2017) admits, language teachers lacking assessment practices are “often the result of inadequate or non-existent training” (p. 267). Most importantly, although they constitute “the largest group of LAL stakeholders”, language teachers “are seldom listened to in the LAL debate” (p. 267). Scarino (2013) also emphasized the importance of language teachers as the most important of all the stakeholders, given that they are the direct test users.

Language assessment TE courses from the teacher educator perspective

Research has been conducted to examine teacher educators’ perspective, that is, what these instructors think about LAT TE courses and how they evaluate them. Jeong (2013) investigated the effect brought about by instructors in shaping the characteristics (i.e., content and structure) of LAT TE courses. Her research results indicated the existence of significant differences in the content of the courses, depending on the instructors’ background in six topic areas: test specifications, test theory, basic statistics, classroom assessment, rubric development, and test accommodation. Course similarities and differences were identified. The importance of a common LAL understanding among all stakeholders was acknowledged as an area to be addressed.

Language teachers’ and LAT TE participating students’ perspective

Research reports that few research studies involve language teachers in the area of language assessment, whose complex variables of LA include educational and assessment policies in and outside institutions, the dynamics of the classroom, and what practitioners bring into the assessment process. Inbar-Lourie (2017) , for example, argues that a limited number of research studies involve teachers’ voices and perspectives. The. Scarino (2013) describes cases which help in the creation of a personalized LAL knowledge base, stemming from language teachers’ own experiences, beliefs, suppositions, and understanding of assessment. Csépes (2014) reports the reluctance of language teachers to adopt alternative assessment procedures suggested by government policies. Hatipoğlu (2015) examines 124 pre-service English language teachers’ perceptions of their prior knowledge on language testing and what a LAT course should include prior to course development. The findings revealed “the effect of local assessment cultures and previous assessment experiences on pre-service teachers’ perceived needs related to language assessment literacy” (p. 111). This study highlighted the importance of lecturers’ collaboration with students during course development.

The above literature review revealed that there is only one study focused on the perceptions of LAT TE participating students. It focuses on their perceptions of language testing prior knowledge and what a LAT course should entail. To the authors’ knowledge, no research has dealt with the perceptions of LAT TE courses regarding their content and value after completion, nor has there been a focus on the evaluation of such courses from the participants’ point of view. These are serious matters that need to be investigated in depth in order to enrich the literature and fill the gap.

Study Aim

The aim of this work was to contribute to filling the aforementioned gap in the literature. The following research questions were the basis of this research:

1. What are the students’ perceptions regarding the evaluation of the CALAT TE received?

2. What suggestions did they make for the improvement of the program?

Method

This research was based on a conceptual, multidimensional e-learning evaluation model, which focused on the evaluation of the CALAT module dimensions, including student engagement and involvement, course structure and material, and course instructor role.

The CALAT LA TE course

The Computer-Assisted Language Assessment and Testing (CALAT) module was one of the eight online modules taught in the CALL program, which are offered by a university in Cyprus. It was a response to the need for LAT TE programs, which would reflect current theories and practices in the area of LAT and would cater for the needs of current LAT classroom practices. The 13-week module was delivered online via the Moodle Platform. Other technologies included Google Drive, email, Facebook, Messenger, Internet resources, Kahoot, etc. The module covered many areas covered in Davies’ (2008) LAL dimensions core list and in Giraldo’s (2018) proposed set of descriptors. It was based on constructivism and social constructivism theories of learning. Assessment was integrated in the module in order to inform and improve participants’ assessment practices ( Malone, 2011 ; Purpura & Turner, 2013). This included quizzes, self, peer- and instructor feedback, ePortfolios, rubrics, and a digital final examination. The module content included “the necessary content for language instructors to apply what they have learned in the classroom and understand the available resources to supplement their formal training when they enter the classroom” ( Malone, 2008, p. 235). LAT practices were suggested, such as the ones mentioned earlier, and the use of technologies for course delivery and assessment. The learning theories were modeled by the instructor throughout the course. The aim was to help language teachers recognize the assessment practice types used during the module in the form of content, LAT knowledge, skills and experiences acquired, and LAT practices they experienced through LAT artefact construction, as well as the construction and application of assessment types in their language teaching practice. The long-term aim was for such personal knowledge to have the potential to be progressively refined as the participants advanced in their careers ( Herrera and Macías, 2015 ).

Time of implementation of program evaluation from the students’ perspective

The MA in CALL program was first offered in September 2015. At the end of the academic year 2018-2019, which marked the end of the first 4-year period (June 2019), a comprehensive program evaluation from the students’ perspective was carried out. This involved all the students who attended the program during those four years.

CALAT TE participating students

There was no process for selecting the participants due to the small number of students who attended the course. For this reason, the respondents were chosen based on their availability ( Babbie, 1990 ). All 25 students who participated in the CUT MA in CALL program over a four-year period (2015-2019) were invited to participate in the research. Participation was voluntary. Nineteen (76%) of the total population participated in the research. Their ages ranged between 22 and 60. The GPA mean was 2,80 for females, and 2,52 for males out of a possible 4,00. The participants’ L1 included English, Greek, Dutch, and Igbo. Participants had learned English as a FL, and all of them had an advanced proficiency level in English (CEFR B2 to C2). The CALAT module participants were practicing language teachers of different languages, namely English (8), Greek (6), Turkish (2), German (1), Igbo (1), and French (1), at different education levels such as primary (3), secondary (14) and tertiary (2), in different countries: Cyprus (10), Greece (6), the Netherlands (2), and Nigeria (1).

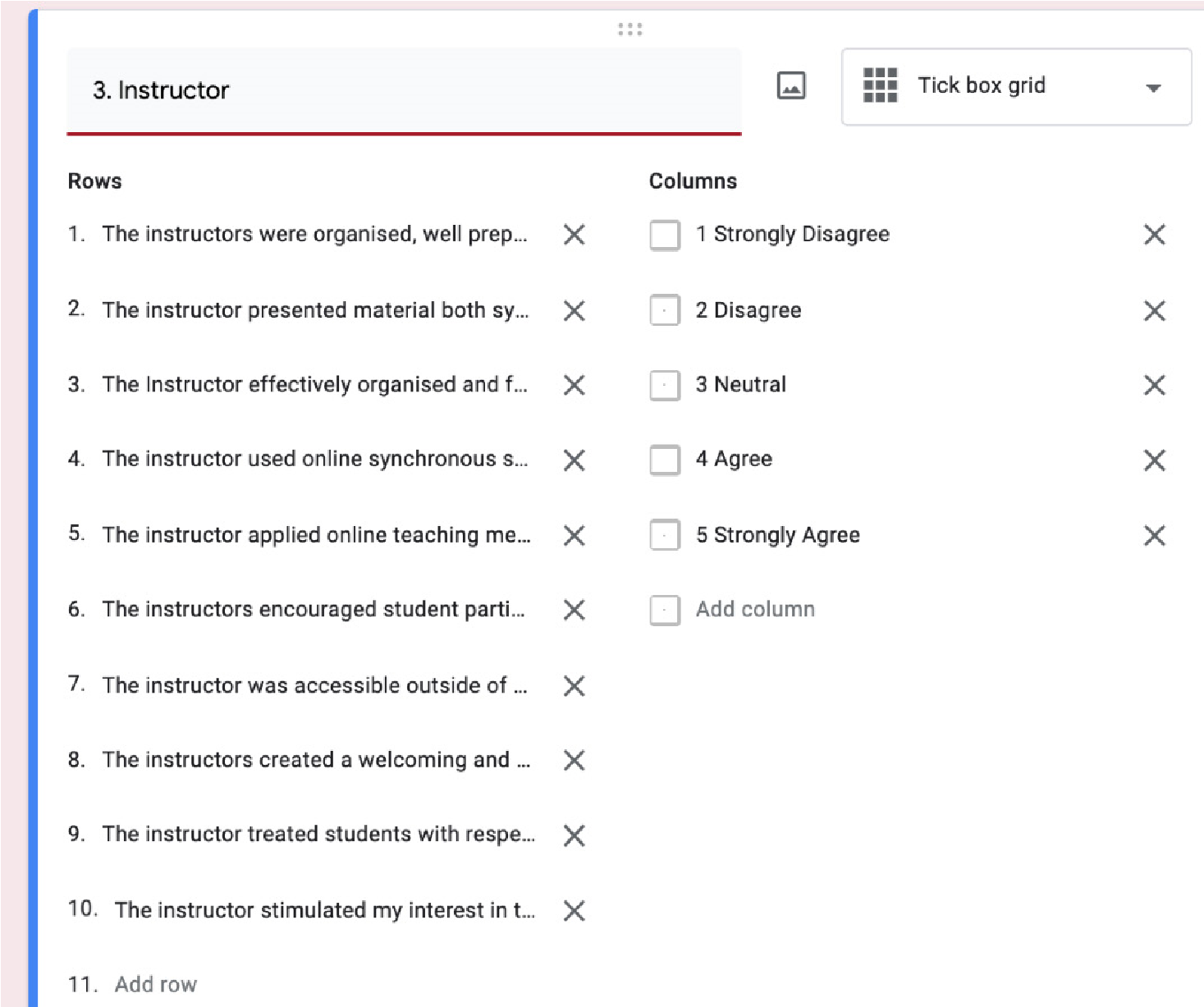

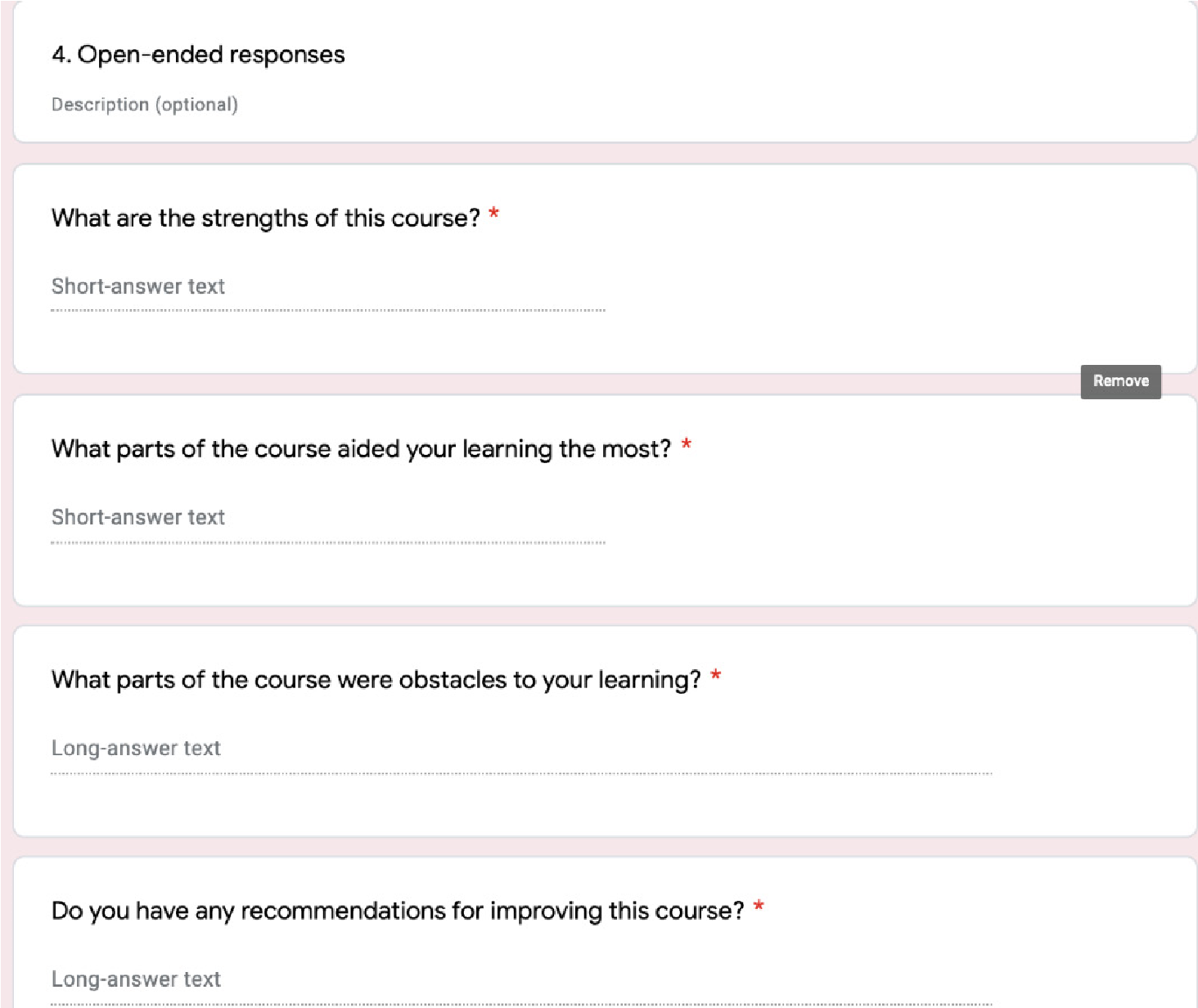

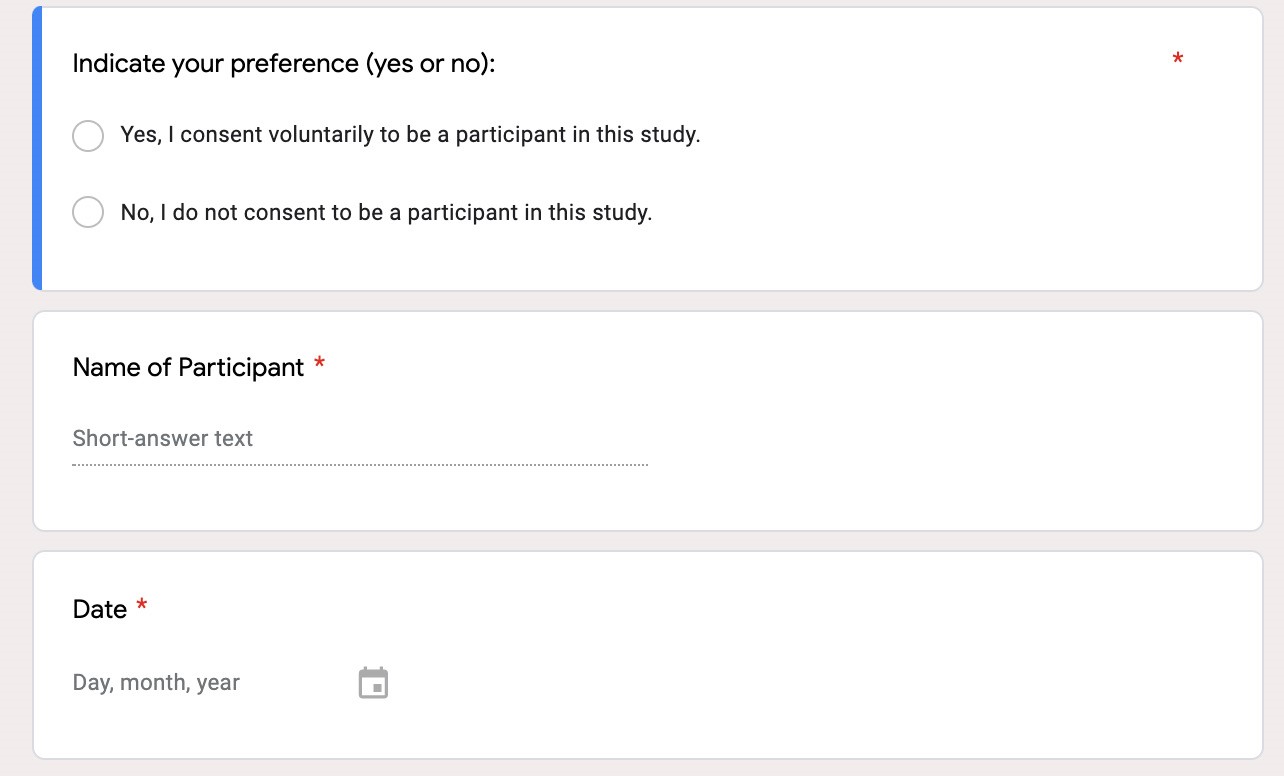

Data collection instruments

A Google Form questionnaire (see Appendix 1) was distributed to all the 25 CALAT TE course participants who were from four different yearly intakes ( Nesbary, 2000. Sue and Ritter, 2007 ). The response rate was 76% (19 students). The questionnaire consisted of factual questions covering the respondents’ demographic characteristics and attitudinal questions exploring students’ attitudes and opinions towards the CALAT TE course. The attitudinal questions were divided into closed-ended and open-ended questions. The closed-ended questions included three five-points Likert scales asking students about their Engagement and Involvement in the course (6 items), their views towards the Course Structure & Material (12 items), and the Instructor (10 items). The five-points Likert scales ranged from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). No negatively worded items were included in the scales. The open-ended questions covered four aspects: 1) course strengths; 2) course aspects most helpful to learning; 3) course aspects that constitute obstacles four learning; and 4) feedback for module improvement. This study discusses the findings of this evaluation.

Data Collection Procedure

The data were collected between May and June of the academic year 2018-2019. The CALAT module students completed the online questionnaire anonymously after their consent form (see Appendix 2 ) was signed and returned to the researcher. Said document informed the students of the research aim, its voluntary nature, a description of the research benefits to future students of the course and their language practice, a statement of confidentiality, and contact details in case of questions. It also included the identity of the researcher and institution ( Creswell, 2009 ).

Data analysis

The questionnaire’s validity and reliability were based on the steps followed in similar questionnaires used at the end of each year for the evaluation of the module, which were based on literature on online questionnaires, checked by experts, and piloted ( Creswell, 2009 ). The quantitative data were analyzed with SPSS 26. Descriptive statistics, the range, the mean, and the standard deviation (SD) were examined to determine the students’ level of satisfaction with the CALAT TE they received. The qualitative data from the open-ended questions were analyzed thematically to explore students’ views towards the course in terms of its strengths, its helpfulness, and its obstacles for learning. Students’ recommendations for improving the course were also analyzed.

Results

The research participants were asked to evaluate the CALAT TE course from their perspective. The first section of the questionnaire investigated the students’ course engagement and involvement. In the six items that constituted this scale, the overall mean of scores as a combined measure was 4,32 (SD = 0,85) on the five-point Likert scale. This indicates a very positive attitude in the participants’ commitment towards the course activities. Within this measure, individual items were analyzed by means of descriptive statistics. The results are displayed in Table 1 .

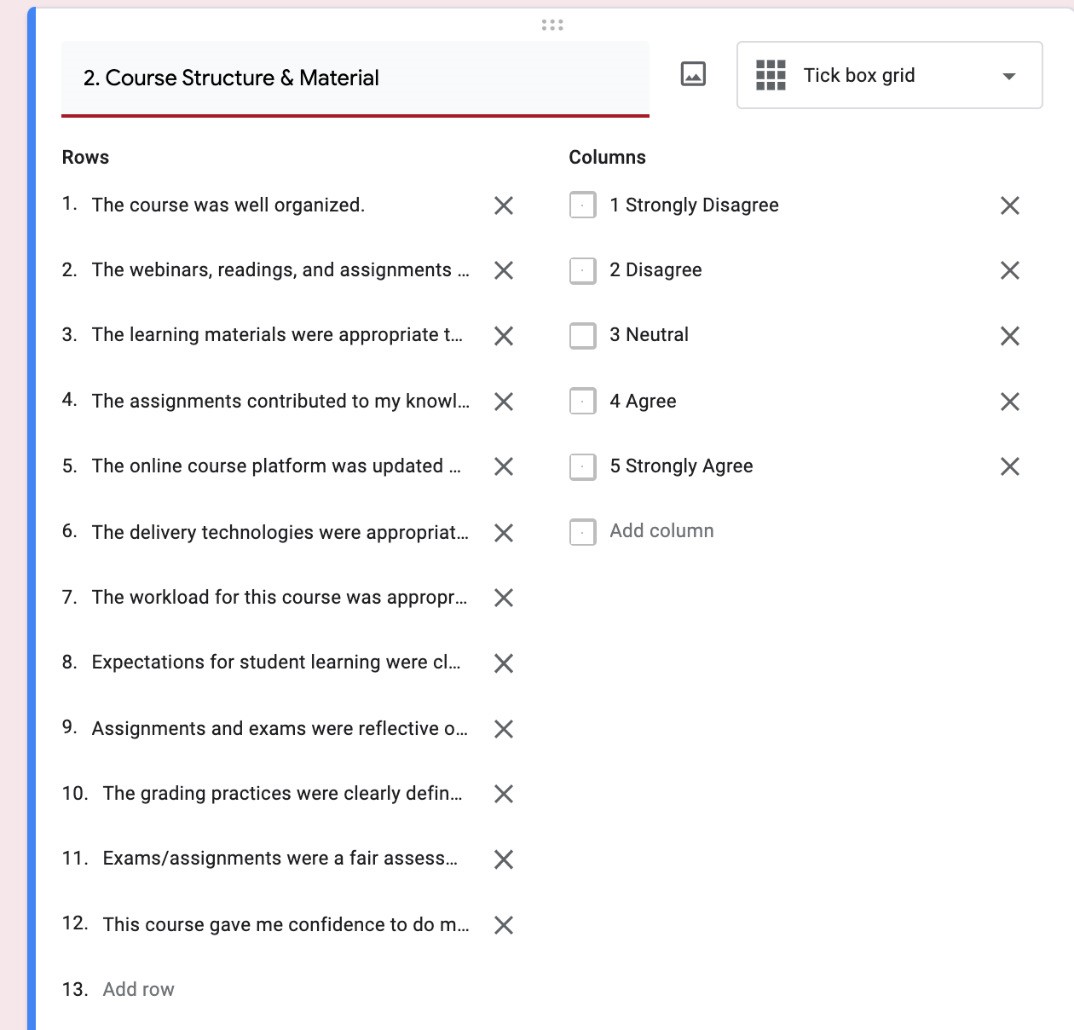

An examination of these items reveals that only two items had a mean score slightly below 4: Q2 and Q4, both targeting the students’ commitment to the course workload. Interestingly, these two items also have the highest standard deviation in the scale, thus indicating the students’ discrepancies in their views towards the course workload. The mean of the remaining items ranges from 4,42 to 4,68 suggesting that the course triggered students’ interest in CALAT TE. The second part of the questionnaire explored the students’ level of satisfaction with the course structure and material. This measure was constituted by twelve items whose overall mean of scores was 4,42 (SD = 0,65). Table 2 presents the results obtained.

The results in Table 2 suggest a very high satisfaction level about the CALAT TE course structure and material, particularly regarding its organization, variety of webinars, reading and assignments, the course platform, grading practices, and assessment methods. The students’ confidence as a result of the course was also very positively valued. Only one item (Q13) showed a mean score slightly below 4; as in the previous scale, this is related to the course workload.

The third section of the questionnaire exained the students’ level of satisfaction with the course instructor. The scale for this measure was built with ten items, whose overall mean of scores was the highest of the three rating scales of the questionnaire: 4,63 (SD = 0,51). Results from the individual items are presented in Table 3 .

Table 1: Descriptive statistics: student engagement and involvement

Item

Min

Max

Mean

SD

Q1. I have put a great deal of effort into advancing my learning in this course.

3

5

4,58

0,61

Q2. I completed my activities on time.

2

5

3,89

1,15

Q3. I attended webinars regularly.

2

5

4,68

0,75

Q4. I consistently worked on weekly tasks.

2

5

3,84

1,30

Q5. In this course, I have been challenged to learn more than I expected.

3

5

4,47

0,61

Q6. This course has increased my interest in this field of study.

3

5

4,42

0,69

Table 2: Descriptive statistics: course structure and material

Item

Min

Max

Mean

SD

Q7. The course was well organized.

3

5

4,47

0,61

Q8. The webinars, readings, and assignments complemented each other.

3

5

4,53

0,61

Q9. The learning materials were appropriate to the goals of the course.

4

5

4,53

0,51

Q10. The assignments contributed to my knowledge of the course material and understanding of the subject.

4

5

4,47

0,51

Q11. The online course platform was updated and accurate.

4

5

4,53

0,51

Q12. The delivery technologies were appropriate.

4

5

4,63

0,50

Q13.The workload for this course was appropriate.

2

5

3,79

0,98

Q14. Expectations for student learning were clearly defined.

3

5

4,53

0,61

Q15. Assignments and exams were reflective of the course content.

2

5

4,37

0,83

Q16. The grading practices were clearly defined.

3

5

4,47

0,61

Q17. Exams/assignments were a fair assessment of my knowledge of the course material.

3

5

4,26

0,81

Q18. This course gave me confidence to do more advanced work on the subject.

3

5

4,42

0,69

Table 3: Descriptive statistics: course instructor

Item

Min

Max

Mean

SD

Q19. The instructor was organized and well prepared.

4

5

4,63

0,50

Q20. The instructor presented material both synchronously and asynchronously in a clear manner that facilitated understanding.

4

5

4,58

0,51

Q21. The instructor effectively organized and facilitated well-run learning activities.

4

5

4,63

0,50

Q22. The instructor used online the time for online synchronous sessions effectively.

4

5

4,68

0,48

Q23. The instructor applied online teaching methods effectively.

4

5

4,63

0,50

Q24. The instructor encouraged student participation during webinars.

3

5

4,58

0,61

Q25. The instructor was accessible outside of scheduled webinars and tutorial time for additional help.

3

5

4,53

0,61

Q26.The instructors created a welcoming and inclusive learning environment.

4

5

4,63

0,50

Q27. The instructor treated students with respect.

4

5

4,79

0,42

Q28. The instructor stimulated my interest in the subject matter.

4

5

4,58

0,51

The analysis of individual items reveals that the students were highly satisfied with the course instructor. More specifically, participants gave a very positive rating to the instructor’s teaching methods, the use of synchronous and asynchronous teaching material, the learning environment created by the instructor, and the instructor’s capability to enhance the learners’ interest in CALAT TE. The fourth and final part of the questionnaire included four openended questions targeting students’ views towards the course strengths, specific parts of the course that helped students in their learning, course obstacles for learning, and recommendations for course improvement.

Regarding the course strengths, five participants (P6, P8, P12, P13, and P18) stated that the course helped them improve their LAT knowledge, skills, and principles. As one student put it, “[the program] set the bases for a better understanding of assessment and testing approaches” (P8). Three students (P10, P14, and P19) found the main strength of the CALAT TE course to be the creation of digital authentic assessment tasks, including computer-based tests. Three other students (P1, P2, and P11) highlighted the course structure, particularly its organization and detailed instructions. In addition, two students (P7 and P9) pointed out that the program helped them with their LA practices; as one participant described, “[the program] provided learners with useful information on language testing and assessment which not only helped for the purpose of this course but can be also put in practice in the school one teaches” (P7). Two other participants (P2, P16) emphasized the course flexibility, given its online modality, which allowed them to work at their own pace. An interesting reflection was made by one student about the module content “the course content on LAT gives you an overall experience and understanding of all the modules taught before” (P3). Other topics were the constructivist approach of learning (P5), and the constant feedback provided by the instructor (P17).

The second open-ended question inquired about the course parts that aided students the most in their learning. Artifact construction including rubrics and computer-based tests (CBT) appeared in the responses of three students (P1, P7, and P19). Three other students (P11, P13, and P14) considered that the course materials, such as reading and video lectures, were the most helpful. Two students emphasized the knowledge gained, particularly the constructive knowledge (P4), as well as the opportunity to put it into practice (P9). Two other students appreciated the new technologies taught (P15), which led, for instance, to the creation of an e-Portfolio; one student found it “useful and fun” (P10). The weekly activities were regarded as an asset by two students (P3 and P6). Other individual responses were related to the use of various forms of assessment and testing (P8), the instructor (P11), the creative and collaborative parts (P16), self and peer assessment (P17), and online synchronous sessions (P12). Among the individual responses, the words of one student stood out:

I never considered testing and assessments to be innovative, creative, or even really interesting. It always seemed to be that this was a “thing that needed to be done”. The course in itself convinced me otherwise and opened a new world to me. (P18)

The third open-ended question explored the students’ views towards the course’s obstacles for learning. Nine students (P5, P7, P8, P11, P12, P13, P16, P18, and P19) could not recall any obstacle; the rest of them pointed out the workload and time constraints. A student (P2) specified that group assignments were the main obstacles, and three other students (P4, P6, and P9) complained about the continuous reflective journals and the weekly tasks; one student mentioned the following:

Sometimes we had to complete more than one task related to the week’s topic. I tended to read the whole articles from the suggested bibliography (I do not want to skim reading) and that took me a longer period of time to finish the readings. (P9)

The last open-ended question asked students about recommendations for improving the course. Similar to the previous question, nine students (P1, P6, P7, P9, P11, P13, P14, P15, and P18) did not have any recommendations to make. However, also in line with the responses to the previous open-ended question, six students (P2, P3, P12, P16, P17, and P19) suggested reducing the number of activities: “less weekly workload would reduce unwelcome stress and improve the experience” (P16). The remaining students had other recommendations. For instance, two students made suggestions related to the use of technology: “introduce more ways to integrate technology and apps in the assessment and testing process” (P8) and “training for using digital games in language learning” (P5). Another student proposed “more emphasis on the teaching experiences, a better division of time, and help provided for the final assignments” (P3).

Discussion

This study has examined the evaluation of a CALAT TE module from a student perspective. Unlike previous studies that have investigated students’ perceived LAT training needs and their expectations from a LAT course (see Hatipoğlu, 2015 ), the current study steps on the claim by InbarLourie (2017) , who has argued the lack of insights from teachers and TE course participants. Based on this claim, this research focused on the evaluation of a CALAT TE program from its students’ perspective, which were reflected on the research questions of the study.

Research Question 1 enquired about the students’ level of satisfaction with the CALAT TE course. The results showed that students had a very positive perception towards the program with regards to their engagement and involvement in the course, the course structure and material, and the instructor’s delivery of the course. In the 28 items that contained scales, only three were slightly below four. These items were related to the students’ commitment to the course activities and the course workload. The remaining items had a mean average of 4,55 (SD = 0,6), which is the midpoint between Agree and Strongly agree in the five-point Likert scale.

Qualitative data from the open-ended question shed further and more focused light on these results. In the analyzed responses to the openended questions, prominent themes were identified.

Contrary to previous research (Deneen & Brown, 2016), students valued the LAT acquired during the CALAT TE program, which indicates that they improved their LAL level during the course. If one considers the historical background of L2 assessment and testing ( Spolsky, 1995. Farhady, 2018 ), the themes identified by students (qualitative data) agree with earlier research and are as follows: 1) types of traditional and alternative assessment such as computer-based and computer adaptive tests ( Chapelle and Douglas, 2006 ); 2) the Common European Framework of Reference for language and assessment (2001), 3) constructivism and social constructivism; 4) reflective learning; 5) collaborative learning; 6) formative ( Stiggins, 2002 ) and summative assessment (feedback, grading, scoring, and reporting, etc.); 6) skills (how to create tests and other types of assessment with the use of technologies); and principles (e.g., using assessment results for feedback to influence language learning, using assessment processes and grades ethically, implementing transparent language assessment practices, informing students of the what, how, and why of assessment, and implementing language assessment practices by giving students opportunities to share their voices about assessment ( Davies, 2008. Inbar-Lourie, 2008. Coombe et al., 2012. Fulcher, 2012. Malone, 2013. Scarino, 2013. Tauyor, 2013. Giraldo, 2018 ).

Furthermore, the use of various forms of assessment and testing, both formative and summative ( Malone, 2011 ; Purpura & Turner, 2013), and the creation of digital authentic assessment tasks, including computer-based contextualized tests (CBT) and rubrics, appeared as a recurrent theme in the qualitative data regarding both the strengths of the course question and the most helpful elements from the course. This shows that the CALAT TE course design included different forms of CBT ( Chapelle and Douglas, 2006 ), which modeled assessment and gave opportunities to construct it (such as contextualized CBTs, FA activities, and rubrics related to their language teaching practices), as well as to prepare the CALAT TE participants for their professional lives. The combination of LAT theory and practice ( Giraldo and Murcia, 2018 ) was indeed highlighted by the participants as a key program element. This can be considered to be progress for the field of CALAT, particularly for educational programs, given that, as of today, many studies have highlighted the existence of inadequate training ( Jeong, 2013. Lam, 2015. Kalajahi and Abdullah, 2016. Tsagari and Vogt, 2017. Hadigol and Kolobandy, 2018). Furthermore, another important theme that arose from the student responses was the course material, particularly the new technologies taught and the use of e-Portfolios ( Stiggins, 2002 ), as well as the constructivist ways of learning, on which the module was based. The program structure, the online course flexibility, and the instructor also appeared in the participants’ responses, in line with the high scores obtained in the items from the Likert scales.

Addressing Research Question 2, which refers to students’ suggestions for the improving the program, as previously shown, 47,37% of the participants did not have any recommendation to improve the course, nor they found any part of the program to be an obstacle for their learning. The rest of the participants (52,63%) indicated the workload being an obstacle, and 36,84% strongly suggested the reduction of workload, while others (10,53%) proposed more ways to integrate technology and apps in the assessment and testing process. Only one student (5,26%) asked for more emphasis on teaching experiences. Their suggestions for improvement were also reflected on the themes that emerged in the qualitative data analysis.

The results account for a program that offers adequate training, relevant to the participants’ practicing needs. More specifically, both the quantitative and qualitative data revealed that the module prepared the participants to conduct assessment-related tasks as part of their teacher training ( Tsagari and Vogt, 2017 ); it provided adequate academic and professional testing background ( Sultana, 2019 ) and included the necessary content for language instructors to apply what they have learned during their training and understand the available resources to supplement their formal training in their practice ( Malone, 2011 ). Lastly, good practices in language assessment were modeled by the module’s teacher educator by means of the curriculum, making assessment expertise explicit in the course. In this way, as described in the qualitative data, the participating students recognized the CALAT educator’s assessment practices and started building their personal knowledge based on LA as informed by their experiences in the CALAT TE module and by its content. Moreover, the results highlight the importance of reporting LAT TE course evaluations from the participants’ perspective in order to expand “appropriate and available professional development opportunities for teachers to meet their assessment needs” ( Tsagari and Vogt, 2017, p. 55 ).

Conclusions

To date, much research in LAT TE has focused on aspects such as LAL definition, LAL dimensions and descriptors, language teachers’ LAL competences and training, and the perceptions of stakeholders such as LAT training courses’ instructors. Nevertheless, this study focuses on the evaluation of a LAT TE course from its participants’ perspective, an area that has been overlooked in the literature. The findings suggest that taking the students’ views into consideration gives useful information on how the receiver evaluates and feels about the LAT training. This information can have the following benefits. As for the participants, it gives them the opportunity to have a say about the course, to evaluate it from their point of view; it can give practitioners a sense of ownership, and it provides practitioners with another form of assessment: course evaluation. Regarding the course itself, it gives instructors and course designers information on how the participants feel about courses similar to the one described in this article, which may prove useful for course improvement. It gives information about how participants feel towards conceptual and theoretical perspectives of evaluation and assessment ( Ghaicha, 2016 ), as dealt with in the module, and how relevant they find these for their practice.

It is important to mention here that this study is not free of limitations, one of which lies on the limited number of participants. Further, largerscale studies are needed to explore this area with more participants in different educational contexts and other parts of the world. Furthermore, another limitation is related to the fact that the responses of students who have completed the program in earlier years may have been affected by the time of course completion and the time at which participants took the survey. In further research, the research methodology can be extended, and data can be collected parallel to the courses in question.

Despite its limitations, this study demonstrates the value of examining the LAT TE course participants’ views and provides useful information on LAT TE course evaluation to stakeholders such as curriculum developers, institutions, teacher educators, online educators, in-services teachers, and researchers. Finally, this work attempts to fill the gap in the evaluative perceptions of participants of LAT teacher training courses. As Inbar-Lourie (2017) has recommended, language teachers, who constitute the largest group of LAL stakeholders, should no longer be left out of the LAL debate.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Clara Valderrama, CAL Journal Assistant to the Editor, and Dr. Christina Giannikas, a colleague and friend, for supporting me with this publication during my difficult times in the hospital as a Covid-19 patient. Thanks also to Maria Victoria Soulé for the data analysis.

References

Appendix 1

Google Form questionnaire for data collection

Appendix 2

Consent form

Métricas

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2021 Salomi Papadima-Sophocleous

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivadas 4.0.

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/