DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/21450706.15417Publicado:

2019-10-18Número:

Vol. 15 Núm. 27 (2020): Enero-JunioSección:

Sección CentralExclusión y construcción social en Colombia: una perspectiva desde tres ritmos populares

Exclusion and Social Construction in Colombia: A Perspective From Three Popular Rhythms

Exclusão e construção social na Colômbia: uma perspectiva de três ritmos populares

Palabras clave:

Bambuco, social construction, cumbia, national music, traditional music, porro (en).Palabras clave:

Bambuco, construcción social, cumbia, música nacional, música tradicional, porro (es).Palabras clave:

Bambuco, construção social, cumbia, música nacional, música tradicional, porro (pt).Descargas

Referencias

Arenas, Eliécer (2009). “El precio de la pureza de sangre: ensayo sobre el papel de los músicos mestizos”, en (Pensamiento), (Palabra) y Obra, vol. 1 (1), pp. 19-35.

Arias, Julio (2007). Nación y diferencia en el siglo XIX colombiano. Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes.

Blacking, John (1980). Le sens musical. Éric et Marika Blondel (trad.). Paris: Les éditions de minuit.

Duque, Ellie Anne (2004). Notas al disco Pedro Morales Pino. Obras para piano. Claudia Calderón (pianista). Colección Música y Músicos de Colombia. Bogotá: Banco de la República.

Elias, Norbert (1997). Logiques de l’exclusion : enquête sociologique au cœur des problèmes d’une communauté. Paris: Éditions Fayard.

Fortich, W, Taboada, R, Baldovino, H, Murillo, P, Álvarez, D & López, A. (2014). Las bandas musicales de viento, origen preservación y evolución: casos de Sucre y Córdoba. Sincelejo: Editorial CECAR.

Garay, Narciso (1894). “La música colombiana”, en Boletín de programas, Instituto Nacional de Radio y Televisión, vol. 23 (226), pp. 29-33.

González Henríquez, Adolfo. (1990). “La música del caribe colombiano durante la guerra de independencia y comienzos de la republica”, en Historia Crítica, N.º 4, pp. 85-112. https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit4.1990.05

Gruzinski, Serge (2012). La pensée métisse. Paris: Éditions Fayard.

Hobsbawm, Eric. (1983). The Invention of Traditions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miñana, Carlos. (1997). “Los caminos del bambuco en el siglo xix”, en A contratiempo, N.º 9, pp. 7-11.

Morillo, O. (2016). Arte popular y crítica a la modernidad. Calle 14 Revista De investigación En El Campo Del Arte, 11(18), 94-105. https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.c14.2016.1.a08

Ocampo López, Javier. (1976). Música y Folclor de Colombia. Bogotá: Plaza y Janes Editores Colombia S.A. Phan, Bernard (2017). Colonisation et décolonisation (XVIe-XXe siècle). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France / Humensis.

Rodríguez Melo, Martha (2012). “El bambuco, música ‘nacional’ de Colombia: entre costumbre, tradición inventada y exotismo”, en Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica Carlos Vega, N.º 26, pp. 297-342.

Urdapilleta, Marco y Núñez, Herminio (2014). “Civilización y barbarie. Ideas acerca de la identidad latinoamericana”, en La Colmena, N.º 82, pp. 31-40.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

140 // CALLE14 // volumen 15, número 27 // enero - junio

de 2020

Exclusion and Social

Construction in Colombia: A Perspective From Three Popular Rhythms

Artículo de

reflexión

Sebastian Olave Soler

Université Paris-Sorbonne, Francia sebastiansoler@laposte.net

—

Recibido 5 de mayo de 2019

Aprobado: 15 de junio de 2019

Cómo citar este artículo: Olave Soler, Sebastian (2020). Exclusion and Social Construction in Colombia: A Perspective from Three Popular Rhythms. Calle 14: revista de investigación en el campo del arte 15(27) pp. 140-151. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/21450706.15417

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.es

Cumbia y porro (2019). Captura de patalla de Google.com

Exclusión y

construcción social en Colombia: una perspectiva desde tres ritmos populares

Resumen

En Colombia, las tradiciones europeas, indígenas y negras se han encontrado e influido mutuamente desde la época colonial. Sin embargo, el predominio político y económico de las élites produjo una subordinación de las prácticas musicales autóctonas y su posterior

transformación. Este artículo considera la estructura social colombiana como el elemento a partir del cual las tradiciones musicales colombianas fueron modeladas. De esta manera, buscamos explicar la evolución de ciertas expresiones artísticas del país, en particular de los ritmos erigidos en símbolos nacionales como resultado de la diferenciación étnica que los ideales europeístas

de las élites fomentaban.

Palabras clave

Bambuco; construcción social; cumbia; música nacional; música tradicional; porro

Exclusion and

Social Construction in Colombia: A Perspective from Three Popular Rhythms

Abstract

In Colombia, European, indigenous and black traditions have met and influenced each other since colonial times. However, the political and economic dominance of the elites produced a subordination of autochthonous musical practices and their subsequent transformation. This article considers the Colombian social structure as the main element that modeled the country’s musical traditions. In this way, we seek to explain the evolution of certain artistic expressions of the country, in particular the musical genres erected as national symbols, as a result of the ethnic differentiation encouraged by the Europeanist ideals of the elites.

Keywords

Bambuco; social construction; cumbia; national music; traditional music; porro

Exclusion et

construction sociale en Colombie : Une perspective depuis trois rythmes

populaires

Résumé

En Colombie, les traditions européennes, indigènes et noires se sont rencontrées et se sont influencées depuis la période coloniale. Cependant, la domination politique et économique des élites a entraîné une subordination des pratiques musicales autochtones et leur transformation ultérieure. Cet article considère la structure sociale colombienne comme l’élément principal qui a modelé les traditions musicales du pays. Nous cherchons ainsi à expliquer l’évolution de certaines expressions artistiques du pays, en particulier les genres musicaux érigés en symboles nationaux, à la suite de la différenciation ethnique encouragée par les idéaux européistes des élites.

Mots clés

Bambuco ; construction sociale ; cumbia ; musique nationale ; musique traditionnelle ; porro

Exclusão e

construção social na Colômbia: uma perspectiva de três ritmos populares

Resumo

Na Colômbia, as tradições européias, indígenas e negras se encontraram e se influenciaram desde os tempos coloniais. No entanto, o domínio político e econômico das elites produziu uma subordinação de práticas musicais autóctones e sua transformação subsequente. Este artigo considera a estrutura social colombiana como o principal elemento que modelou as tradições musicais do país. Desta forma, procuramos explicar a evolução de certas expressões artísticas do

país, em particular os gêneros musicais erguidos como símbolos nacionais, como resultado da diferenciação étnica incentivada pelos ideais europeístas das elites.

Palavras-chave

Bambuco; construção social; cumbia; música nacional; música tradicional; porro

Rurai iuiai nukanchipa Colombiamanda: sug kauai kimsama kauaspa

Maillallachiska

Kai Colombiapi tradicionkuna europea Nukanchipa i ianakunapa kauarinmi kagta tarinakuska parijuma época colonialmandata. Chasallata mandankuna iapa politicokuna i economicokuna elitekuna churarkuna subirviiai tunail Nukanchipa trukangapa kai uauakilkaska kauanmi estructura socila Colombiapi imasami kallari tukaikunata kallariskakunamoldeangapa imasami tsukarirka kauai artísticas kai luarpi chasallata chi ritmokuna atarichiska símbolo nacionalsina europeokunapa iuiakunaua churaska.

Rimangapa Ministidukuna

Bambuco; construcción social; cumbia; tunai nacional; Nukanchipa tunai; porro

Introduction

In Colombia, the nation-building process that took place after Independence gave rise to a very unequal country, whose social structure has remained virtu- ally unchanged over time. The elites have based their power of government on economic domination and on an alleged racial superiority inherent to Europeans. As Julio Arias asserts, in Colombia, “la nación fue al mismo tiempo un proyecto de unificación y diferenciación, en el cual la figura del pueblo se constituyó en paralelo con la de la élite nacional” (2007, p. 7)1. Artistic prac- tices were then used in this process to legitimize the political power. The progressive imposition of a certain vision of the European culture, led to the stigmatiza- tion and containment of popular expressions, including the proscription of African practices and the merging of indigenous traditions with Catholic rituals. Thus, through the imposition of a ‘high culture’ the social division was accentuated: music was excluded because it was of popular origin, and the popular was discrimi- nated because it was alien to the dominant cultural system. In this way, the artistic object was politicized through its production within a code incomprehensible to the ‘others’. In other words, they—the others—are uncivilized because they cannot understand it.2 John Blacking maintains that this codification reinforces indeed the separation into higher and lower groups: “L’écoute passive est le prix que certains doivent payer pour devenir membres d’une société supérieure, dont la supériorité est fondée sur les aptitudes exceptionnelles d’une petite élite” (1980, p. 43)3.

As a matter of fact, music

in Colombia was not only recreated from the interaction of all the elements that converged in America, it took part,

as well, of the social construction of the country. That

is one of the reasons why the artistic practices of the country

can tell us a great deal

about how cultural

differences have been adapted to the civilizing claims of the Colombian elite.

Therefore, this article tries to show, through three of the most representative rhythms of the country —bambuco, cumbia and porro—, the mechanisms of miscegenation and exclusion resulting from the particular socio-political development of Colombia from the beginnings of the republican period. We intent to illustrate how the social configuration has influenced the development of artistic forms in the country and the marginalization that it embodies. As evidence of this, we will discuss the specific evolution of musical forms, the way in which this evolution has produced musical ensembles that fit the social characteristics of the country and the dynamics of social hierarchization that they reveal.

Dialectics

of the nation and national genres

Music, as we have stated, has been instrumentalized in the dialectic of the nation-building process to impose an aesthetic valuation that privileged the cultural prac- tices of Europeans. This process caused the intrinsic characteristics of an immense part of the population to be ignored, distorted or even suppressed, creating a monolithic identity based on ideals foreign to those that it claimed to represent. In the geographical center of the country, where the maintenance of the appearances related to social position and skin tone was paramount, the ‘official’ musical forms were the only ones accepted and sponsored, while on the Colombian Atlantic coast, the traditional expressions and their stylized variants had a parallel existence that did not necessarily lead to the ostracism of the original forms. As a result, traditional ensembles have kept their prominence for decades in rural areas and small villages that have been formed around agricultural exploitations and livestock farms. The socio-economic dynamics of the postcolonial period, on the other hand, produced a transmutation from the traditional forms towards instrumental ensembles that could represent the prog ress sought by the ruling class. In the central regions, it was especially the piano that represented this progress; in the Atlantic coast, it was the instrumental ensembles created from wind instruments of European origin.

In this way, it can be understood that the ‘Colombian music’ of the nineteenth century was played on the piano or in the trio típico6—both of European origin—, and that in the coastal regions, the musical traditions of black and indigenous peoples had to be adapted to brass ensembles such as the military band, the brass band, and later on, the big band. The playing tech- niques, the repertoire, the instrumental training, the places of production and consumption, the notation of the music, the structures and modes of versifica- tion adapted to the European canon, all have become

essential conditions for any kind of music to be consid- ered as artistically valid. This arbitrary distinction meant the simultaneous uprooting of other musical forms, so much so that the term ‘Colombian music’ designated for a long time, by antonomasia, the music of the elite of the center of the country. For the same reason, tambora music and gaita music, heavily influenced by black and indigenous ancestry, were banned from the music scene for decades. Likewise, the introduction in the power centers of vallenato and cumbia, years later, responded to a similar formalization and ‘purification’.

Eric Hobsbawm explains that “invented traditions have important social and political functions, they would not exist or would not be established if they could not acquire them” (1983, p. 307). As it was the case with History or Government, the musical heritage that contained the ‘essence of the nation’ was con- ceived from the vision of the ruling class installed in Bogotá, legitimizing in this way their political power.

Ultimately, the importance of this heritage did not lie in the characteristics of one or the other music, but in their semantic dimension: the important thing is what they communicate, what they represent, what they can designate. The fundamental thing is the idea of Nation that can be created from these. That is why European- rooted music was the only one that had been accepted in literary circles and it was from here that it was built as musical practice and as ‘official’ history of the music in Colombia. For this very reason the musical expres- sions that took part of that history were those associ- ated with a written tradition; traditional music, black or aboriginal, with its essentially oral mode of transmis- sion, was excluded. The evolution of the three rhythms that we intend to address here allows us to see to what extent the Colombian social hierarchy conditioned the configuration of those rhythms.

The bambuco and

its place as a national

symbol

The bambuco is perhaps the most remarkable and the most obvious example of manipulation of tradition and musical heritage in Colombia. This rhythm, erected as a national symbol at the end of the nineteenth century, allows us to corroborate the strategies of the ruling class in Colombia. There is no doubt that the symbolism associated with this genre exceeds its musical char- acteristics, although the latter are a testimony of the discursive tensions.

The bambuco comes from southwestern Colombia, with black African roots—evident in the similarities to such genres as currulao, aguabajo and jota chocoana from the Pacific coast. It was originally associated with the people, the lower classes, the peasants and the women who accompanied the troops of the independence army. It was a music of celebration, of din, even of combat. In general terms, with other rhythms such as torbellino or guabina, bambuco was the sound of the poorest part of society, especially in the central region of the country.

Precisely because of this preponderance on the popu- lar classes, the bambuco was a useful element in the unifying eagerness of the elite. The assertion of Narciso Garay (1876-1953) famous writer, diplomat, violinist

and Colombian composer, synthesizes the thought of the time: “La ausencia de una ‘música nacional’ solo puede superarse dispensando al bambuco de su bajo

y plebeyo estatus” (1894, p. 243)7. It was under this premise that bambuco was chosen to represent “the feeling of the Colombian people”. This choice was moti- vated, in addition to those already mentioned, by two reasons. On one hand, it was a very common genre in the interior of the country: the nation-building process, which was set up in Bogotá, was from the beginning

a centralist project that looked down on the provin- cial regions.8 On the other hand, it was a music easily assimilated to the European models in vogue in Bogotá: in addition to having pieces with dancing structures, it was a genre that already used instruments of European origin, like the guitar, which facilitated its reconversion.

Javier Ocampo Lopez states that “en el folclore andino, la cultura mestiza predomina con el predominio [sic] de las supervivencias españolas sobre los nativos [..]) son elementos hispánicos, con adaptaciones y creaciones colombianas” (1976, p. 94)9. Ocampo overlooks the fact that it is not accidental that Hispanic ‘survivals’ have imposed themselves over the artistic forms of aborigi- nal and African descent. It was not fortuitous; it was

a conscious political choice of the ruling classes who sought to define a particular type of society. Indeed, as part of the construction of the nation, the bambuco had to fit into the process of ‘civilization’ that already touched other areas of culture and society. The shat- tering music of the people, “el bullicioso bambuco de flautas, vientos y tamboras, el bambuco bélico y popular” (Miñana, 1997, p. 7) could not enter into this form in the temples of civilization and good taste that claimed to be the salons of Bogotá. It required a stylistic adaptation, as confirmed by Carlos Miñana: “Tenía que aclimatarse porque no es aceptable el ruido de un tambor en una sala de estar” (1997, p. 7). This situation is better understood if one takes into account that the high society of Bogotá sought to reproduce the musical evenings of the European salons. In the salons at Santa Fe, however, Italian opera, foxtrots, waltzes and Schottisch (or chotís) were played: light music and simple structures. Bambucos and pasillos slowly entered into the repertories of these evenings, first in the virtuous fantasies like that of Manuel María Párraga; then, adjusted to the shapes of the usual light pieces of these salons: binary or ternary forms, simple modulations and homophonic textures.

The consolidation of bambuco as national music came with its notation. In addition to being seen as a sign of progress and, at the same time, allow defining the historical and future characteristics of the genre, the written document also refers to certain cultural mod- els.11 In this aspect, the figure of Pedro Morales Pino (1863-1926) is particularly important because it was him who, from the Andean musical traditions, designed a stylized music and executed it “en versiones impeca- bles, hombro a hombro con los repertorios de concierto del momento” (Duque, 2004, p. 4)12. Morales Pino, in other words, is the one who adapted bambuco to the social pretensions of the literate classes, determined and disclosed its characteristics, fixed its structure, its organology and consolidated, in short, an interpretive tradition (Rodriguez Melo, 2012).

As it seems evident, bambuco was no longer a genre that conveyed popular expression; it had become an artificial rhythm used within the exclusivist practices of the salon music of the upper classes. This led to a denaturalization of the genre because of the subse- quent imposition of this new form of bambuco and the proscription of its most ‘rustic’ variants —s a huge paradox if we take into account the fact that the elite has presented this music as a representation of ‘colom- bianism’, while closing the doors of their salons to the authentic expression of those whom they boasted to symbolize

The Cumbia, between a white country and a black music Cumbia, as it was the case of bambuco, undertook a major transformation to be adapted to the preten- sions of the political and economic centers of power. In the regions of the Atlantic coast, as in the capital of the country in the nineteenth century, the upper class sought to impose European rhythms as an example of sophistication in detriment of traditional practices. The wealthy groups danced in their salons waltzes, contre- danses, and minuets. Black music, on the other hand, was forbidden in the squares of large cities since it was considered contrary to morality and order.

Although the traditional ensembles were in fact con- sidered rudimentary, strident and unrefined, the rural and festive character of the people of the Colombian Caribbean region, noticeable even in the richest part of the society, made it easier to the antagonistic social classes to meet in the middle of popular celebrations. In this way, it is explained that the members of the upper class have had less inconvenience to end their festivities not with waltzes and polkas, but with the popular rhythms of black and native origin considered as more vivid. Adolfo Gonzalez Henriquez emphasizes:

“estas reuniones deben ser tan animadas e interesantes que, aunque se encuentran entre uno de los sectores más pobres de la población, los señores de la clase alta los frecuentaron, huyendo clandestinamente de sus propios salones” (1988, p. 197).

It is important to mention that, in these coastal areas, the indigenous and black presence was stronger, and thus the mestizo element was more important than in the center of the country. As a result, social divisions were driven more by economic factors than by ethnic ones. Even though the relationship between classes had less racial tension, it was nonetheless pyramidal.

The balance of power was based on an unequal access to wealth, the prerogatives of the colony having allowed some families to gather large tracts of land. With the end of the wars of emancipation, large-scale productive activities were put in place, which, together with the subsequent abolition of slavery, allowed the arrival and reunion of large groups of migrant workers of various origins. Porro and cumbia, as well as other indigenous and black rhythms, were part of the entertainment of peasants and artisans who found in music and dance the only distractions of an otherwise monotonous and particularly difficult life devoted to farming. That is why this music is essentially peasant and popular, their texts are inspired by the native land and their dances remain associated with the rural areas.

The music that was played in the traditional groups

—sets of gaita or millo, depending on the place, or rhythms of cumbia, puya, gaita, merengue, among many others—began to move towards the instrumental ensembles that were part of the celebrations of the upper class. These traditional rhythms kept some of their characteristic folk roots, although they lost their spontaneity by abandoning autochthonous instruments, seem as backward. Knowing that this migration was promoted by the economic supremacy of a class, the adaptation of the music had to be made according to the tastes and demands of those who had the power

of choice.

On the one hand, this meant that

the adapta- tion of one format

to another was made by musicians

from a popular and amateur

background, trained to perform the instruments in the military bands.16 It also

allowed, on the other hand,

the simultaneous existence of different formats

that have remained associated with popular expressions in a sort of double

life that did not prevent acceptance, a priori, in any of the oppo- site social

circles. This divergence from the process

of the center of the country

proves itself decisive for the

survival of the genres in the cultural

dynamics of the popular classes. One of the most obvious

examples of this situation is the corralejas, events

that allowed the encounter of social groups

antagonistic by principle.

The corralejas, a popular hybrid of Spanish bullfights and the famous encierros of San Fermín, is one of the first spaces where the brass band, paid for by the big breeders, performed without shame all genres in a relaxed, festive atmosphere, in large open spaces

that required instrumental ensembles that were strong enough to reach as many participants as possible.

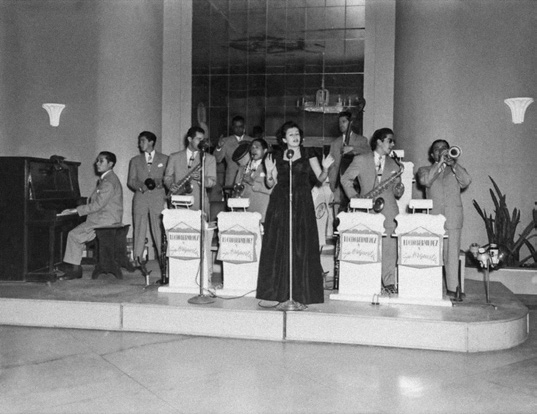

Imagen 1. Lucho Bermúdez’s orchestra at the Nutibara Hotel in Medellin, 1948. Source: Archivo Radio Nacional.

The corralejas were—and still are—one of the main popular festivities in the rural areas of the Colombian Atlantic coast, where the main activity is extensive livestock breeding. In large urban centers such as Cartagena, Barranquilla or Santa Marta, social dynam- ics functioned differently, as these cities were sub- ordinated to the political influences of the center of the country. In social exchanges, formalities were observed with more rigor, and by extension, the struc- tural requirements demanded from music were much more stringent than in the rural areas. As a result,

cumbia had to refine itself to be able to enter the select clubs of the coastal elite. It had to be able to match the rhythms that were starting to come from North America and the Caribbean—mainly bolero, danzón,

fox-trot, charleston, mambo—and which were danced at the salons. The traditional ‘banda pelayera’ format was forced to adapt to the more ‘civilized’ format of the American big band: its sounds were softened, the structure of the music was adapted to the song format

—verse and chorus—, arrangements were refined and written, and rhythms were simplified. This transforma- tion was evident not only in the rhythmic structure, morphology, organological transformation and other basic musical elements, but in the behavior of the

musicians themselves, in their location and posture on the stage, their behavior, and even in their outfits and hairstyles (see image 1).

All these

changes were enforced

to meet the social

demands imposed by the capital. In the center

of the

country, the behavioral differences associated as inherent to physical characteristics and ethnic heritage produced disdain

for anything that

could be related to the popular.

The artistic expressions of mestizos, blacks and natives were considered inappropriate for a country that,

from the capital,

was considered white and refined. The importance of the approval from the Bogotá aristocracy can be summarized in two points.

First, the socio-political influence and second, the economic interests. The first, meant to be accepted in the circles of power, to be considered an equal by the elite of Bogotá and thus to be able to address those who ran the country. Second, adapting to these demands also meant expanding the music market at the time of the arrival of the record industry and the radio. The entrance of record labels and the radio, which began in the centers of power, opened up new economic oppor- tunities for musicians too, as it gave them the opportu- nity of reaching stable work contracts in hotels, social clubs and radio stations.

The elites

of Bogotá, for their part,

saw in the cumbia the possibility of using the

musical heritage of the Caribbean region,

once stylized, to integrate the coastal

populations into the image of the country.

If with bambuco the ruling

class tried to show a country of European tradition in the image of its aristocracy, with cumbia it

sought to reveal a new image,

less central- ized, multiethnic and multicultural, which would

take into account the regions. However, from

the cumbia of the blacks and the indigenous peoples of the Colombian rural country

there was not much left:

there remained a watered-down version adapted to the self- recognition needs

of the elite of Bogotá,

who finally embraced it when

it was already

marketed throughout America. In the same way, this discourse on miscege- nation remains only

a political tool

used to unify

hetero- geneous populations under

the same idea

of country, while the

inhabitants of coastal

and littoral regions

have continued to suffer from

unequal access to land, work, education and political representation.

Porro, popular and refined, as a meeting

place

Porro, like cumbia, is the result of exchanges and the mutual influence of indigenous and black peoples pres- ent in the north of the country. It was a rhythm origi- nally performed by Caribbean coast ensembles during outdoor celebrations, aboriginal rituals or syncretistic religious festivities. This genre, as well as the rhythms associated with it—fandangos, puyas, and cumbias, among others—was part of the traditions of the lower classes—indigenous peoples, blacks and peasants.

Although it is now accepted that melodic construction is an indigenous heritage while the rhythmic structure comes from Africa—a thesis reinforced by the organol- ogy of traditional ensembles—the interaction of these groups is obviously more complex. The indigenous peoples of the Caribbean coast, to cite just one exam- ple, built percussion instruments before their encounter with Africans, particularly through a ring-tensioned system; similarly, many forms of versification that are essentially responsorial have been adapted from black ritual songs such as lumbalú.

The economic tensions of the postcolonial period and the issues raised by the struggle around socio-political power forced porro to be adapted to the formats com- ing from the United States, Cuba and Mexico, reaching in this way, the main economic poles of the country, in particular Bogotá. This process removed many impor- tant features of this rhythm, blurring along the way its popular roots. The porro that consumers in the Andean regions danced—and listened—was only a refined and distorted version of this music, through the big bands that played it in social clubs. In general, the adapta- tion of one format to the other sought to amalgam- ate the original rhythms of the region with European dances such as polka, minuet, waltz and especially the contredanse, interpreted regularly by the wind bands. This new porro, specially adapted to be part of those ballroom dancing, was also the way in which the upper classes sought to distinguish themselves from practices and social groups that they considered as foreign to the progress they intended to represent.

In the traditional format,

the limitations inherent

in a traditional construction of gaitas and millo, in addition

to the way of understanding the melodic and harmonic

construction of the natives, clearly distinguish the porro played in gaitas of its variant developed in the brass bands.

In gaita and millo, the structure is freer, and its

phrases follow one another from

a responsorial procedure: more or less recurrent sentences are com- bined with

improvisation. The social

function of these ensembles can also be considered much

more specific and limited

to contexts of community celebration.

On the other hand, in the ‘pelayera’ band there was a hybridization between the practices of the traditional groups and the forms of the European dance music. The porros, fandangos and puyas of these bands were con- ceived in such a way that even keeping the popular root that had created them in the first place, these rhythms could be adapted to the taste of the wealthy classes.

In addition to the obvious change in tone brought by the new instruments, the adaptation of traditional genres also involved an arrangement of instrumen- tal writing. One of the most complex elements of this adaptation is undoubtedly the creation of multiple melodic lines, the conception of a polyphonic texture from a music that favors the rhythmic component. At the formal level, these genres also had to be adapted to get closer to the European forms that dominated the salons. Although, as has been explained, the internal arrangement of the sentences met other criteria, the establishment of a general form was necessary, in par- ticular to satisfy the usual dance conventions in salons and social clubs, to limit improvisations and facilitate their subsequent transcription to score.

The interpretation of

porro by the pelayera bands

Which currently tends to

be considered as typical is however

closer to the

indigenous ensem- bles than to the modern symphonic wind band or even

the big band.

The disparities in instrumental performance technique in relation to the standardized European practice are evident. As is the case with the sets of gaitas and

millos, in the pelayera band

the tuning is relative, while

it does not refer to the temper- ate scale of the West. The timbre of the clarinet, for example, is much

closer to the

high-pitched, throb- bing and biting sound

of the millo and

the gaitas than that of the round

sound of the European clarinet.

This peculiarity emphasizes the eminently popular character of pelayera bands that has not necessarily been lost with the adjustment of the more traditional ensembles to brass formats. Nevertheless, the adapta- tion that brought porro into the cities of the center of the country—especially the big band versions of Pacho Galán and Lucho Bermúdez—omits in fact many of the peculiarities that gave rise to this rhythm. As was the case with cumbia, the stylized version of the porro gets lost in the uniformity of reproduction and in the negation of the characteristic constructions of the different populations of the country. By framing it inside the schemas and conventions of the European and North American culture, porro loses its ritual char- acter, its community construction and its characteristic spontaneity.

Conclusion

As we have seen, social processes have determined the artistic forms of the country: the characteris- tics of the three expressions we have discussed are not the product of fortuitous encounters, but of the tensions inherent to the social conformation and the political and economic circumstances of the country.

Consequently, the characteristics inherent to musical practices—morphology, organology, rhythm, harmony, etc.—can enlighten the frictions produced by the interaction of social groups. In this particular case, it has allowed us to grasp how the musical expressions were instrumentalized by the Colombian elite in its quest to build a nation that would satisfy their ideals of civilization and refinement. Thus, not only have the

unequal accumulation of wealth, urbanization processes and ethnic distinctions turned Colombia into one of

the most unequal countries, music itself has been used as an element of marginalization: bambuco—branded as ‘national music’—was performed more and more according to European tastes and technique, in detri- ment of more traditional forms. Cumbia had to lose

its African, most original and most popular side to be accepted and especially marketed, first in the center of the country, and then throughout America. Porro had to be transfigured into three different forms to continue to exist socially.

The ambition of acknowledgment and legitimization of the elites has produced the alienation and deface- ment of the traditional artistic heritage and, therefore, the negation of the true heterogeneous nature of the Colombian people. The cultural wealth of the country lies undoubtedly in the diversity of expressions that have met and influenced mutually since colonial times.

The roots of the country are as Spanish as they are black and indigenous. Accordingly, we cannot recognize ourselves in the multiplicity that we share as long as

we continue to accept black and indigenous musical expressions and their merits, but refuse to accept the peoples who created them.

References

Arenas, Eliécer (2009). “El precio de la pureza de sangre: ensayo sobre el papel de los músicos mestizos”, en (Pensamiento), (Palabra) y Obra, vol. 1 (1), pp. 19-35.

Arias, Julio (2007). Nación y diferencia en el siglo XIX colombiano. Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes.

Blacking, John (1980). Le sens musical. Éric et Marika Blondel (trad.). Paris: Les éditions de minuit.

Duque, Ellie Anne (2004). Notas al disco Pedro Morales Pino. Obras para piano. Claudia Calderón (pianista).

Colección Música y Músicos de Colombia. Bogotá: Banco de la República.

Elias, Norbert (1997). Logiques de l’exclusion : enquête sociologique au cœur des problèmes d’une communauté. Paris: Éditions Fayard.

Fortich, W, Taboada, R, Baldovino, H, Murillo, P, Álvarez, D & López, A. (2014). Las bandas musicales de viento, origen preservación y evolución: casos de Sucre y Córdoba. Sincelejo: Editorial CECAR.

Garay, Narciso (1894). “La música colombiana”, en Boletín de programas, Instituto Nacional de Radio y Televisión, vol. 23 (226), pp. 29-33.

González Henríquez, Adolfo. (1990). “La música del caribe colombiano durante la guerra de independencia y comienzos de la republica”, en Historia Crítica, N.º 4, pp. 85-112. https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit4.1990.05

Gruzinski, Serge (2012). La pensée métisse. Paris: Éditions Fayard.

Hobsbawm, Eric. (1983). The Invention of Traditions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miñana, Carlos. (1997). “Los caminos del bambuco en el siglo xix”, en A contratiempo, N.º 9, pp. 7-11.

Morillo, O. (2016). Arte popular y crítica a la modernidad. Calle 14 Revista De investigación En El Campo Del Arte, 11(18), 94-105. https://doi. org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.c14.2016.1.a08

Ocampo López, Javier. (1976). Música y Folclor de Colombia. Bogotá: Plaza y Janes Editores Colombia S.A. Phan, Bernard (2017). Colonisation et décolonisation (XVIe-XXe siècle). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France / Humensis.

Rodríguez Melo, Martha (2012). “El bambuco, música ‘nacional’ de Colombia: entre costumbre, tradición inventada y exotismo”, en Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica Carlos Vega, N.º 26, pp. 297-342.

Urdapilleta, Marco y Núñez, Herminio (2014). “Civilización y barbarie. Ideas acerca de la identidad latinoamericana”, en La Colmena, N.º 82, pp. 31-40.

ResumenPalabras clave: Bambuco, social construction, cumbia, national music, traditional music, porro.

ResumenPalabras clave: Bambuco, construction sociale, cumbia, musique nationale, musique traditionnelle, porro.

ResumenPalabras clave: Bambuco, construção social, cumbia, música nacional, música tradicional, porro.

ResumenPalabras clave: Bambuco, construcción social, cumbia, tunai nacional, Nukanchipa tunai, porro.

Introduction

In Colombia, the nation-building process that took place after Independence gave rise to a very unequal country, whose social structure has remained virtu- ally unchanged over time. The elites have based their power of government on economic domination and on an alleged racial superiority inherent to Europeans. As Julio Arias asserts, in Colombia, “la nación fue al mismo tiempo un proyecto de unificación y diferenciación, en el cual la figura del pueblo se constituyó en paralelo con la de la élite nacional” (2007, p. 7)1. Artistic prac- tices were then used in this process to legitimize the political power. The progressive imposition of a certain vision of the European culture, led to the stigmatiza- tion and containment of popular expressions, including the proscription of African practices and the merging of indigenous traditions with Catholic rituals. Thus, through the imposition of a ‘high culture’ the social division was accentuated: music was excluded because it was of popular origin, and the popular was discrimi- nated because it was alien to the dominant cultural system. In this way, the artistic object was politicized through its production within a code incomprehensible to the ‘others’. In other words, they—the others—are uncivilized because they cannot understand it.2 John Blacking maintains that this codification reinforces indeed the separation into higher and lower groups: “L’écoute passive est le prix que certains doivent payer pour devenir membres d’une société supérieure, dont la supériorité est fondée sur les aptitudes exceptionnelles d’une petite élite” (1980, p. 43)3.

As a matter of fact, music in Colombia was not only recreated from the interaction of all the elements that converged in America, it took part, as well, of the social construction of the country. That is one of the reasons why the artistic practices of the country can tell us a great deal about how cultural differences have been adapted to the civilizing claims of the Colombian elite.

Therefore, this article tries to show, through three of the most representative rhythms of the country —bambuco, cumbia and porro—, the mechanisms of miscegenation and exclusion resulting from the particular socio-political development of Colombia from the beginnings of the republican period. We intent to illustrate how the social configuration has influenced the development of artistic forms in the country and the marginalization that it embodies. As evidence of this, we will discuss the specific evolution of musical forms, the way in which this evolution has produced musical ensembles that fit the social characteristics of the country and the dynamics of social hierarchization that they reveal.

Dialectics of the nation and national genres

Music, as we have stated, has been instrumentalized in the dialectic of the nation-building process to impose an aesthetic valuation that privileged the cultural prac- tices of Europeans. This process caused the intrinsic characteristics of an immense part of the population to be ignored, distorted or even suppressed, creating a monolithic identity based on ideals foreign to those that it claimed to represent. In the geographical center of the country, where the maintenance of the appearances related to social position and skin tone was paramount, the ‘official’ musical forms were the only ones accepted and sponsored, while on the Colombian Atlantic coast, the traditional expressions and their stylized variants had a parallel existence that did not necessarily lead to the ostracism of the original forms. As a result, traditional ensembles have kept their prominence for decades in rural areas and small villages that have been formed around agricultural exploitations and livestock farms. The socio-economic dynamics of the postcolonial period, on the other hand, produced a transmutation from the traditional forms towards instrumental ensembles that could represent the prog ress sought by the ruling class. In the central regions, it was especially the piano that represented this progress; in the Atlantic coast, it was the instrumental ensembles created from wind instruments of European origin.

In this way, it can be understood that the ‘Colombian music’ of the nineteenth century was played on the piano or in the trio típico6—both of European origin—, and that in the coastal regions, the musical traditions of black and indigenous peoples had to be adapted to brass ensembles such as the military band, the brass band, and later on, the big band. The playing tech- niques, the repertoire, the instrumental training, the places of production and consumption, the notation of the music, the structures and modes of versifica- tion adapted to the European canon, all have become essential conditions for any kind of music to be consid- ered as artistically valid. This arbitrary distinction meant the simultaneous uprooting of other musical forms, so much so that the term ‘Colombian music’ designated for a long time, by antonomasia, the music of the elite of the center of the country. For the same reason, tambora music and gaita music, heavily influenced by black and indigenous ancestry, were banned from the music scene for decades. Likewise, the introduction in the power centers of vallenato and cumbia, years later, responded to a similar formalization and ‘purification’.

Eric Hobsbawm explains that “invented traditions have important social and political functions, they would not exist or would not be established if they could not acquire them” (1983, p. 307). As it was the case with History or Government, the musical heritage that contained the ‘essence of the nation’ was con- ceived from the vision of the ruling class installed in Bogotá, legitimizing in this way their political power.

Ultimately, the importance of this heritage did not lie in the characteristics of one or the other music, but in their semantic dimension: the important thing is what they communicate, what they represent, what they can designate. The fundamental thing is the idea of Nation that can be created from these. That is why European- rooted music was the only one that had been accepted in literary circles and it was from here that it was built as musical practice and as ‘official’ history of the music in Colombia. For this very reason the musical expres- sions that took part of that history were those associ- ated with a written tradition; traditional music, black or aboriginal, with its essentially oral mode of transmis- sion, was excluded. The evolution of the three rhythms that we intend to address here allows us to see to what extent the Colombian social hierarchy conditioned the configuration of those rhythms.

The bambuco and its place as a national symbol

The bambuco is perhaps the most remarkable and the most obvious example of manipulation of tradition and musical heritage in Colombia. This rhythm, erected as a national symbol at the end of the nineteenth century, allows us to corroborate the strategies of the ruling class in Colombia. There is no doubt that the symbolism associated with this genre exceeds its musical char- acteristics, although the latter are a testimony of the discursive tensions.

The bambuco comes from southwestern Colombia, with black African roots—evident in the similarities to such genres as currulao, aguabajo and jota chocoana from the Pacific coast. It was originally associated with the people, the lower classes, the peasants and the women who accompanied the troops of the independence army. It was a music of celebration, of din, even of combat. In general terms, with other rhythms such as torbellino or guabina, bambuco was the sound of the poorest part of society, especially in the central region of the country.

Precisely because of this preponderance on the popu- lar classes, the bambuco was a useful element in the unifying eagerness of the elite. The assertion of Narciso Garay (1876-1953) famous writer, diplomat, violinist and Colombian composer, synthesizes the thought of the time: “La ausencia de una ‘música nacional’ solo puede superarse dispensando al bambuco de su bajo y plebeyo estatus” (1894, p. 243)7. It was under this premise that bambuco was chosen to represent “the feeling of the Colombian people”. This choice was moti- vated, in addition to those already mentioned, by two reasons. On one hand, it was a very common genre in the interior of the country: the nation-building process, which was set up in Bogotá, was from the beginning a centralist project that looked down on the provin- cial regions.8 On the other hand, it was a music easily assimilated to the European models in vogue in Bogotá: in addition to having pieces with dancing structures, it was a genre that already used instruments of European origin, like the guitar, which facilitated its reconversion.

Javier Ocampo Lopez states that “en el folclore andino, la cultura mestiza predomina con el predominio [sic] de las supervivencias españolas sobre los nativos [..]) son elementos hispánicos, con adaptaciones y creaciones colombianas” (1976, p. 94)9. Ocampo overlooks the fact that it is not accidental that Hispanic ‘survivals’ have imposed themselves over the artistic forms of aborigi- nal and African descent. It was not fortuitous; it was a conscious political choice of the ruling classes who sought to define a particular type of society. Indeed, as part of the construction of the nation, the bambuco had to fit into the process of ‘civilization’ that already touched other areas of culture and society. The shat- tering music of the people, “el bullicioso bambuco de flautas, vientos y tamboras, el bambuco bélico y popular” (Miñana, 1997, p. 7) could not enter into this form in the temples of civilization and good taste that claimed to be the salons of Bogotá. It required a stylistic adaptation, as confirmed by Carlos Miñana: “Tenía que aclimatarse porque no es aceptable el ruido de un tambor en una sala de estar” (1997, p. 7). This situation is better understood if one takes into account that the high society of Bogotá sought to reproduce the musical evenings of the European salons. In the salons at Santa Fe, however, Italian opera, foxtrots, waltzes and Schottisch (or chotís) were played: light music and simple structures. Bambucos and pasillos slowly entered into the repertories of these evenings, first in the virtuous fantasies like that of Manuel María Párraga; then, adjusted to the shapes of the usual light pieces of these salons: binary or ternary forms, simple modulations and homophonic textures.

The consolidation of bambuco as national music came with its notation. In addition to being seen as a sign of progress and, at the same time, allow defining the historical and future characteristics of the genre, the written document also refers to certain cultural mod- els.11 In this aspect, the figure of Pedro Morales Pino (1863-1926) is particularly important because it was him who, from the Andean musical traditions, designed a stylized music and executed it “en versiones impeca- bles, hombro a hombro con los repertorios de concierto del momento” (Duque, 2004, p. 4)12. Morales Pino, in other words, is the one who adapted bambuco to the social pretensions of the literate classes, determined and disclosed its characteristics, fixed its structure, its organology and consolidated, in short, an interpretive tradition (Rodriguez Melo, 2012).

As it seems evident, bambuco was no longer a genre that conveyed popular expression; it had become an artificial rhythm used within the exclusivist practices of the salon music of the upper classes. This led to a denaturalization of the genre because of the subse- quent imposition of this new form of bambuco and the proscription of its most ‘rustic’ variants —s a huge paradox if we take into account the fact that the elite has presented this music as a representation of ‘colom- bianism’, while closing the doors of their salons to the authentic expression of those whom they boasted to symbolize

The Cumbia, between a white country and a black music Cumbia, as it was the case of bambuco, undertook a major transformation to be adapted to the preten- sions of the political and economic centers of power. In the regions of the Atlantic coast, as in the capital of the country in the nineteenth century, the upper class sought to impose European rhythms as an example of sophistication in detriment of traditional practices. The wealthy groups danced in their salons waltzes, contre- danses, and minuets. Black music, on the other hand, was forbidden in the squares of large cities since it was considered contrary to morality and order.

Although the traditional ensembles were in fact con- sidered rudimentary, strident and unrefined, the rural and festive character of the people of the Colombian Caribbean region, noticeable even in the richest part of the society, made it easier to the antagonistic social classes to meet in the middle of popular celebrations. In this way, it is explained that the members of the upper class have had less inconvenience to end their festivities not with waltzes and polkas, but with the popular rhythms of black and native origin considered as more vivid. Adolfo Gonzalez Henriquez emphasizes:

“estas reuniones deben ser tan animadas e interesantes que, aunque se encuentran entre uno de los sectores más pobres de la población, los señores de la clase alta los frecuentaron, huyendo clandestinamente de sus propios salones” (1988, p. 197).

It is important to mention that, in these coastal areas, the indigenous and black presence was stronger, and thus the mestizo element was more important than in the center of the country. As a result, social divisions were driven more by economic factors than by ethnic ones. Even though the relationship between classes had less racial tension, it was nonetheless pyramidal.

The balance of power was based on an unequal access to wealth, the prerogatives of the colony having allowed some families to gather large tracts of land. With the end of the wars of emancipation, large-scale productive activities were put in place, which, together with the subsequent abolition of slavery, allowed the arrival and reunion of large groups of migrant workers of various origins. Porro and cumbia, as well as other indigenous and black rhythms, were part of the entertainment of peasants and artisans who found in music and dance the only distractions of an otherwise monotonous and particularly difficult life devoted to farming. That is why this music is essentially peasant and popular, their texts are inspired by the native land and their dances remain associated with the rural areas.

The music that was played in the traditional groups —sets of gaita or millo, depending on the place, or rhythms of cumbia, puya, gaita, merengue, among many others—began to move towards the instrumental ensembles that were part of the celebrations of the upper class. These traditional rhythms kept some of their characteristic folk roots, although they lost their spontaneity by abandoning autochthonous instruments, seem as backward. Knowing that this migration was promoted by the economic supremacy of a class, the adaptation of the music had to be made according to the tastes and demands of those who had the power of choice. On the one hand, this meant that the adapta- tion of one format to another was made by musicians from a popular and amateur background, trained to perform the instruments in the military bands.16 It also allowed, on the other hand, the simultaneous existence of different formats that have remained associated with popular expressions in a sort of double life that did not prevent acceptance, a priori, in any of the oppo- site social circles. This divergence from the process of the center of the country proves itself decisive for the survival of the genres in the cultural dynamics of the popular classes. One of the most obvious examples of this situation is the corralejas, events that allowed the encounter of social groups antagonistic by principle.

The corralejas, a popular hybrid of Spanish bullfights and the famous encierros of San Fermín, is one of the first spaces where the brass band, paid for by the big breeders, performed without shame all genres in a relaxed, festive atmosphere, in large open spaces that required instrumental ensembles that were strong enough to reach as many participants as possible.

The corralejas were—and still are—one of the main popular festivities in the rural areas of the Colombian Atlantic coast, where the main activity is extensive livestock breeding. In large urban centers such as Cartagena, Barranquilla or Santa Marta, social dynam- ics functioned differently, as these cities were sub- ordinated to the political influences of the center of the country. In social exchanges, formalities were observed with more rigor, and by extension, the struc- tural requirements demanded from music were much more stringent than in the rural areas. As a result, cumbia had to refine itself to be able to enter the select clubs of the coastal elite. It had to be able to match the rhythms that were starting to come from North America and the Caribbean—mainly bolero, danzón, fox-trot, charleston, mambo—and which were danced at the salons. The traditional ‘banda pelayera’ format was forced to adapt to the more ‘civilized’ format of the American big band: its sounds were softened, the structure of the music was adapted to the song format —verse and chorus—, arrangements were refined and written, and rhythms were simplified. This transforma- tion was evident not only in the rhythmic structure, morphology, organological transformation and other basic musical elements, but in the behavior of the musicians themselves, in their location and posture on the stage, their behavior, and even in their outfits and hairstyles (see image 1).

All these changes were enforced to meet the social demands imposed by the capital. In the center of the country, the behavioral differences associated as inherent to physical characteristics and ethnic heritage produced disdain for anything that could be related to the popular. The artistic expressions of mestizos, blacks and natives were considered inappropriate for a country that, from the capital, was considered white and refined. The importance of the approval from the Bogotá aristocracy can be summarized in two points.

First, the socio-political influence and second, the economic interests. The first, meant to be accepted in the circles of power, to be considered an equal by the elite of Bogotá and thus to be able to address those who ran the country. Second, adapting to these demands also meant expanding the music market at the time of the arrival of the record industry and the radio. The entrance of record labels and the radio, which began in the centers of power, opened up new economic oppor- tunities for musicians too, as it gave them the opportu- nity of reaching stable work contracts in hotels, social clubs and radio stations.

The elites of Bogotá, for their part, saw in the cumbia the possibility of using the musical heritage of the Caribbean region, once stylized, to integrate the coastal populations into the image of the country. If with bambuco the ruling class tried to show a country of European tradition in the image of its aristocracy, with cumbia it sought to reveal a new image, less central- ized, multiethnic and multicultural, which would take into account the regions. However, from the cumbia of the blacks and the indigenous peoples of the Colombian rural country there was not much left: there remained a watered-down version adapted to the self- recognition needs of the elite of Bogotá, who finally embraced it when it was already marketed throughout America. In the same way, this discourse on miscege- nation remains only a political tool used to unify hetero- geneous populations under the same idea of country, while the inhabitants of coastal and littoral regions have continued to suffer from unequal access to land, work, education and political representation.

Porro, popular and refined, as a meeting place

Porro, like cumbia, is the result of exchanges and the mutual influence of indigenous and black peoples pres- ent in the north of the country. It was a rhythm origi- nally performed by Caribbean coast ensembles during outdoor celebrations, aboriginal rituals or syncretistic religious festivities. This genre, as well as the rhythms associated with it—fandangos, puyas, and cumbias, among others—was part of the traditions of the lower classes—indigenous peoples, blacks and peasants.

Although it is now accepted that melodic construction is an indigenous heritage while the rhythmic structure comes from Africa—a thesis reinforced by the organol- ogy of traditional ensembles—the interaction of these groups is obviously more complex. The indigenous peoples of the Caribbean coast, to cite just one exam- ple, built percussion instruments before their encounter with Africans, particularly through a ring-tensioned system; similarly, many forms of versification that are essentially responsorial have been adapted from black ritual songs such as lumbalú.

The economic tensions of the postcolonial period and the issues raised by the struggle around socio-political power forced porro to be adapted to the formats com- ing from the United States, Cuba and Mexico, reaching in this way, the main economic poles of the country, in particular Bogotá. This process removed many impor- tant features of this rhythm, blurring along the way its popular roots. The porro that consumers in the Andean regions danced—and listened—was only a refined and distorted version of this music, through the big bands that played it in social clubs. In general, the adapta- tion of one format to the other sought to amalgam- ate the original rhythms of the region with European dances such as polka, minuet, waltz and especially the contredanse, interpreted regularly by the wind bands. This new porro, specially adapted to be part of those ballroom dancing, was also the way in which the upper classes sought to distinguish themselves from practices and social groups that they considered as foreign to the progress they intended to represent.

In the traditional format, the limitations inherent in a traditional construction of gaitas and millo, in addition to the way of understanding the melodic and harmonic construction of the natives, clearly distinguish the porro played in gaitas of its variant developed in the brass bands. In gaita and millo, the structure is freer, and its phrases follow one another from a responsorial procedure: more or less recurrent sentences are com- bined with improvisation. The social function of these ensembles can also be considered much more specific and limited to contexts of community celebration.

On the other hand, in the ‘pelayera’ band there was a hybridization between the practices of the traditional groups and the forms of the European dance music. The porros, fandangos and puyas of these bands were con- ceived in such a way that even keeping the popular root that had created them in the first place, these rhythms could be adapted to the taste of the wealthy classes.

In addition to the obvious change in tone brought by the new instruments, the adaptation of traditional genres also involved an arrangement of instrumen- tal writing. One of the most complex elements of this adaptation is undoubtedly the creation of multiple melodic lines, the conception of a polyphonic texture from a music that favors the rhythmic component. At the formal level, these genres also had to be adapted to get closer to the European forms that dominated the salons. Although, as has been explained, the internal arrangement of the sentences met other criteria, the establishment of a general form was necessary, in par- ticular to satisfy the usual dance conventions in salons and social clubs, to limit improvisations and facilitate their subsequent transcription to score.

The interpretation of porro by the pelayera bands

Which currently tends to be considered as typical is however closer to the indigenous ensem- bles than to the modern symphonic wind band or even the big band. The disparities in instrumental performance technique in relation to the standardized European practice are evident. As is the case with the sets of gaitas and millos, in the pelayera band the tuning is relative, while it does not refer to the temper- ate scale of the West. The timbre of the clarinet, for example, is much closer to the high-pitched, throb- bing and biting sound of the millo and the gaitas than that of the round sound of the European clarinet.

This peculiarity emphasizes the eminently popular character of pelayera bands that has not necessarily been lost with the adjustment of the more traditional ensembles to brass formats. Nevertheless, the adapta- tion that brought porro into the cities of the center of the country—especially the big band versions of Pacho Galán and Lucho Bermúdez—omits in fact many of the peculiarities that gave rise to this rhythm. As was the case with cumbia, the stylized version of the porro gets lost in the uniformity of reproduction and in the negation of the characteristic constructions of the different populations of the country. By framing it inside the schemas and conventions of the European and North American culture, porro loses its ritual char- acter, its community construction and its characteristic spontaneity.

Conclusion

As we have seen, social processes have determined the artistic forms of the country: the characteris- tics of the three expressions we have discussed are not the product of fortuitous encounters, but of the tensions inherent to the social conformation and the political and economic circumstances of the country.

Consequently, the characteristics inherent to musical practices—morphology, organology, rhythm, harmony, etc.—can enlighten the frictions produced by the interaction of social groups. In this particular case, it has allowed us to grasp how the musical expressions were instrumentalized by the Colombian elite in its quest to build a nation that would satisfy their ideals of civilization and refinement. Thus, not only have the unequal accumulation of wealth, urbanization processes and ethnic distinctions turned Colombia into one of the most unequal countries, music itself has been used as an element of marginalization: bambuco—branded as ‘national music’—was performed more and more according to European tastes and technique, in detri- ment of more traditional forms. Cumbia had to lose its African, most original and most popular side to be accepted and especially marketed, first in the center of the country, and then throughout America. Porro had to be transfigured into three different forms to continue to exist socially.

The ambition of acknowledgment and legitimization of the elites has produced the alienation and deface- ment of the traditional artistic heritage and, therefore, the negation of the true heterogeneous nature of the Colombian people. The cultural wealth of the country lies undoubtedly in the diversity of expressions that have met and influenced mutually since colonial times.

The roots of the country are as Spanish as they are black and indigenous. Accordingly, we cannot recognize ourselves in the multiplicity that we share as long as we continue to accept black and indigenous musical expressions and their merits, but refuse to accept the peoples who created them.

References

Arenas, Eliécer (2009). “El precio de la pureza de sangre: ensayo sobre el papel de los músicos mestizos”, en (Pensamiento), (Palabra) y Obra, vol. 1 (1), pp. 19-35.

Arias, Julio (2007). Nación y diferencia en el siglo XIX colombiano. Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes.

Blacking, John (1980). Le sens musical. Éric et Marika Blondel (trad.). Paris: Les éditions de minuit.

Duque, Ellie Anne (2004). Notas al disco Pedro Morales Pino. Obras para piano. Claudia Calderón (pianista).

Colección Música y Músicos de Colombia. Bogotá: Banco de la República.

Elias, Norbert (1997). Logiques de l’exclusion : enquête sociologique au cœur des problèmes d’une communauté. Paris: Éditions Fayard.

Fortich, W, Taboada, R, Baldovino, H, Murillo, P, Álvarez, D & López, A. (2014). Las bandas musicales de viento, origen preservación y evolución: casos de Sucre y Córdoba. Sincelejo: Editorial CECAR.

Garay, Narciso (1894). “La música colombiana”, en Boletín de programas, Instituto Nacional de Radio y Televisión, vol. 23 (226), pp. 29-33.

González Henríquez, Adolfo. (1990). “La música del caribe colombiano durante la guerra de independencia y comienzos de la republica”, en Historia Crítica, N.º 4, pp. 85-112. https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit4.1990.05

Gruzinski, Serge (2012). La pensée métisse. Paris: Éditions Fayard.

Hobsbawm, Eric. (1983). The Invention of Traditions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miñana, Carlos. (1997). “Los caminos del bambuco en el siglo xix”, en A contratiempo, N.º 9, pp. 7-11.

Morillo, O. (2016). Arte popular y crítica a la modernidad. Calle 14 Revista De investigación En El Campo Del Arte, 11(18), 94-105. https://doi. org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.c14.2016.1.a08

Ocampo López, Javier. (1976). Música y Folclor de Colombia. Bogotá: Plaza y Janes Editores Colombia S.A. Phan, Bernard (2017). Colonisation et décolonisation (XVIe-XXe siècle). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France / Humensis.

Rodríguez Melo, Martha (2012). “El bambuco, música ‘nacional’ de Colombia: entre costumbre, tradición inventada y exotismo”, en Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica Carlos Vega, N.º 26, pp. 297-342.

Urdapilleta, Marco y Núñez, Herminio (2014). “Civilización y barbarie. Ideas acerca de la identidad latinoamericana”, en La Colmena, N.º 82, pp. 31-40.

Licencia

Licencia actual vigente

Creative Commons BY NC SA - Atribución – No comercial – Compartir igual. Vigente a partir del Vol. 17 No. 32: (julio-diciembre) de 2022.

This work is licensed under a https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.es

Licencias anteriores

- Desde el Vol. 14 Núm. 25 (2019) hasta el Vol. 17 Núm. 31: enero-junio de 2022 se utilizó la licencia Creative Commons BY NC ND https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.es

- Desde el Vol 1 Num 1 (2007) hasta el Vol. 13 Núm. 23 (2018) la licencia fue Creative Commons fue Reconocimiento- Nocomercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/co/