DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/21450706.19623Publicado:

2022-07-22Número:

Vol. 17 Núm. 32 (2022): Julio-Diciembre 2022Sección:

Sección CentralAnish Kapoor y el material más oscuro: un análisis desde el libertarismo de izquierda

Anish Kapoor and the darkest material: An analysis from left-libertarianism

Anish Kapoor e o material mais obscuro: uma análise do liberalismo de esquerda

Palabras clave:

Mapping, public space, artistic practices, cultural resistance (en).Palabras clave:

Estética, Oscuro, Ética, Moral, Filosofía del Arte, Filosofía del Derecho (es).Palabras clave:

Estética, Obscuro, Ética, Moral, Filosofia da Arte, Filosofia do Direito (pt).Descargas

Referencias

Aquinas, T. (1993). The treatise on law: Being Summa Theologiae, I-II. QQ. 90 through 97. Notre Dame, IN, USA: University of Notre Dame Press.

Aristotle. (1986). De anima. Middlesex, NJ, USA: Penguin Books.

Aristotle. (2018). Rhetoric. Cambridge, UK: Hackett Publishing Company Inc.

Baudelaire, C. (1992). Selected writings on art and literature. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Becker, H. S. (2008). Art worlds. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press.

Belton, R. (1996). Art History: A Preliminary Handbook. Vancouver, BC, Canada: University of British Columbia.

Bois, Y. (2007). Klein's relevance for today. October, 119, 75-93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40368459

Cambridge (n.d.) Appropriation. In Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/appropriation

Cambridge (n.d.) Justice. In Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/justice

Cambridge (n.d.) Libertarianism. In Cambridge Dictionary. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/libertarianism/#PowerApp

Cambridge (n.d.) Resource. In Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/resource

Cascone, S. (2019, January 30). Anish Kapoor owns the rights to the blackest color ever made. So another artist made his own superblack –and now it’s even blacker. Artnet. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/stuart-semple-blackest-black-anish-kapoor-1452259

Challa, J. (2017, July 11). “hy everybody's mad at Anish Kapoor. The Architect’s Newspaper. https://archpaper.com/2017/07/anish-kapoor-blackest-black/

Chu, J. (2019, September 12). MIT engineers develop “blackest black” material to date. MIT News. https://news.mit.edu/2019/blackest-black-material-cnt-0913

Danto, A. C. (1964). The Artworld. The Journal of Philosophy, 61(19), 571-584. https://doi.org/10.2307/2022937

Danto, A. C. (2003). The abuse of beauty: Aesthetics and the concept of art. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press.

Danto, A. C. (2004). Kalliphobia in Contemporary Art. Art Journal, 63(2), 24-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2004.10791123

Dickie, G. (1974). Art and the aesthetic: An institutional analysis. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell University Press.

Douma, S., and Schreuder, H. (1992). Economic approaches to organizations. New York, NY, USA: Prentice Hall.

Dworkin, R. (1986). Law's empire. Cambridge, UK: Belknap Press.

Eco, U. (2004). On beauty. London, UK: Secker & Warburg.

Esaak, S. (2019, August 17). What is the definition of color in art? ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/definition-of-color-in-art-182429

Fried, M. (1967). Art and objecthood. New York, NY, USA: Garland Pub. Co.

Gage, J. (2006). Color in art. New York, NY, USA: Thames & Hudson.

Gage, J. (2000). Color and meaning: Art, science, and symbolism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Goodman, N. (1978). Ways of worldmaking. Indianapolis, IN, USA: Hackett Publishing Company.

Griffiths, C., and Donovan, N. (2016, February 27). Artists at war after top sculptor is given exclusive rights to the purest black paint ever which is used on stealth jets. Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3467507/Artists-war-sculptor-given-exclusive-rights-purest-black-paint-used-stealth-jets.html

Hart, H. L. A. (2012). The concept of law. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hart, H. L. A. (1958). Positivism and the separation of law and morals. Harvard Law Review, 71(4), 593-629. https://doi.org/10.2307/1338225

Hayter, R., and Patchell, J. (2016). Economic geography: an institutional approach. Don Mills, ON, Canada: Oxford University Press.

Heller, E. (2004). Psicología del color: cómo actúan los colores sobre los sentimientos y la razón. Barcelona, Spain: Gustavo Gili.

Kandinsky, W. (1946). Concerning the spiritual in art. New York, NY, USA: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Kirzner, I. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Macdonald, C. (2015). What is colour? a defence of colour primitivism. In R. Johnson and M. Smith (Eds.), Passions and Projections (pp. 116-133). New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

Moos, D. (2005). The shape of colour: Excursions in colour field art 1950-2005. Toronto, ON, Canada: Art Gallery of Ontario.

Morby, A. (2017, July 07). Anish Kapoor banned from using colour-changing paint in ongoing rights war. Dezeen. https://www.dezeen.com/2017/07/07/anish-kapoor-banned-from-using-stuart-semple-colour-changing-paint-design-news/

Ngai, S. (2015). Our aesthetic categories. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press.

Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, state, and utopia. New York, NY, USA: Basic Books.

Penner, J., and Otsuka, M. (Eds.) (2018). Property theory: Legal and political perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Pownall, R., and Graddy, K. (2016). Pricing color intensity and lightness in contemporary art auctions. Research in Economics, 70(3), 412-420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rie.2016.06.007

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge, UK: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Redaction. (2001, October 20). 'Everyone's an artist, anything can be art. The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/4726169/Everyones-an-artist-anything-can-be-art.html

Reise, B. (1992). Greenberg and the group: A retrospective view. In F. Frascina and J. Harris (Eds.), Art in modern culture: An anthology of critical texts (pp. 252-264). New York, NY, USA: Harper Collins.

Rodal, C. (2010). Manifiesto y vanguardia: los manifiestos del futurismo italiano, dadá y el surrealismo. Bilbao, Spain: University of the Basque Country, Publishing Services.

Rogers, A. (2017, June 22). Art Fight! The Pinkest Pink Versus the Blackest Black. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/vantablack-anish-kapoor-stuart-semple/

Rollins, M. (Ed.) (2012). Danto and his critics. Malden, MA, USA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Rothbard, M. (1978). For a new liberty: the libertarian manifesto. New York, NY, USA: Collier Books.

Rothbard, M. (1982). The ethics of liberty. Atlantic Highlands, NJ, USA: Humanities Press.

Sala-i-Martín, X. (2017). Economía liberal para no economistas y no liberales. Barcelona, Spain: Penguin Random House Mondadori.

Schulz, R. A. (1978). Does Aesthetics have anything to do with Art? Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 36(4), 429-440. https://doi.org/10.2307/430483

Sooke, A. (2014, August 28). Yves Klein, the man who invented a colour. BBC. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140828-the-man-who-invented-a-colour

Souriau, É. (1998). Diccionario Akal de Estética. Madrid, Spain: Akal.

Vallentyne, P. and Steiner, H. (2000). Left-libertarianism and its critics: the contemporary debate. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave.

van der Bossen (2019). Libertarianism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/libertarianism/#PowerApp

Vilar, G. (2005). Las razones del arte. Boadilla del Monte, Spain: A. Machado Libros.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Anish Kapoor y el material más oscuro: un análisis desde el libertarismo de izquierda

Anish Kapoor and the darkest material: An analysis from left- libertarianism

Anish Kapoor et la matière la plus sombre : une analyse du libertarisme de gauche

Anish Kapoor e o material mais obscuro: uma análise do liberalismo de esquerda

Anish Kapoor y el material más oscuro: un análisis desde el libertarismo de izquierda

Calle14: revista de investigación en el campo del arte, vol. 17, núm. 32, 2022

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional.

Recepción: 12 Septiembre 2021

Aprobación: 11 Diciembre 2021

Resumen:

En este texto realizamos un análisis de las acciones del artista angloíndio Anish Kapoor, quien adquirió el derecho a ser el único artista que puede utilizar el material más oscuro del mundo. Esto tuvo un gran impacto y generó discusiones dentro del mundo del arte. Algunos artistas crearon el color más verde del mundo, el más rosado del mundo o el más brillante del mundo y permitieron que todas las personas lo compraran, excepto Kapoor y sus asociados. Presentamos un análisis desde la perspectiva del libertarismo de izquierda sobre si la acción de Kapoor es moral o no. Para ello, el texto se divide en dos partes: la primera es un análisis del papel del color en la historia del arte y la segunda aborda la legitimidad de las patentes y la acción de Kapoor.

Palabras clave: Estética, Oscuro, Ética, Moral, Filosofía del Arte, Filosofía del Derecho.

Abstract: In this text, we carry out an analysis of the actions of Anglo-Indian artist Anish Kapoor, who acquired the right to be the only artist who can use the darkest material in the world. This had a great impact and generated discussions within the art world. Some artists created the world's greenest color, the world's pinkest color, or the world's brightest color and allowed all individuals except Kapoor and his associates to purchase it. We present an analysis from the perspective of Left-Libertarianism on whether Kapoor's action is moral or not. To this effect, the text is divided in two parts: the first is an analysis of the role of color in art history, and the second addresses the legitimacy of patents and Kapoor's action.

Keywords: Mapping, public space, artistic practices, cultural resistance.

Résumé:

Dans ce texte nous effectuons une analyse de l'action menée par l'artiste anglo-indien Anish Kapoor. Kapoor a acquis le droit d'être le seul artiste capable d'utiliser le matériau le plus noir du monde. Cette action a généré un vaste impact et des discussions au sein du monde de l'art. Certains artistes ont créé la couleur la plus verte du monde, la couleur la plus rose du monde ou la couleur la plus brillante du monde et ont permis à tous les individus sauf Kapoor et ses associés de l'acheter. Nous présentons une analyse du point de vue du libertarismede gauche sur la question de savoir si l'action de Kapoor est morale ou non. Pour ce faire, le texte est divisé en deux parties distinctes. La première est une analyse du rôle de la couleur dans l'histoire de l'art. La seconde présente la légitimité des brevets et de l'action de Kapoor.

Mots clés: Esthétique, noir, éthique, moral, philosophie de l'art, philosophie du droit.

Resumo:

Neste texto realizamos uma análise das ações do artista anglo-indiano Anish Kapoor, quem adquiriu o direito de ser o único artista que pode utilizar o material mais obscuro do mundo. Isto teve um grande impacto e gerou discussões dentro do mundo da arte. Alguns artistas criaram a cor mais verde do mundo, a mais rosada do mundo ou a mais brilhante do mundo e permitiram que todos as pessoas as comprassem, exceto Kapoor e os seus associados. Apresentamos uma análise desde a perspectiva do libertarismo de esquerda sobre se a ação de Kapoor é moral ou não. Para este fim, o texto se divide em duas partes: a primeira é uma análise do papel da cor na história da arte e a segunda trata da legitimidade das patentes e da ação de Kapoor.

Palavras-chave: Estética, Obscuro, Ética, Moral, Filosofia da Arte, Filosofia do Direito.

Introduction

In the first part of this article, we present an analysis, from a left-libertarian perspective, of an action carried out by artist Anish Kapoor, who acquired the exclusive right to use the world's blackest material from the company Surrey Nanosystems.

To this end, this text will articulate fields such as aes- thetics, art philosophy, moral philosophy, ethics, and the art market –especially from the institutional theory of art.

In the first place, we will present the case descripti- vely, based on the media coverage. In addition, to verify that the case is presented from duly reliable data, the text was sent to Anish Kapoor through his representative, Erica Bolton (Bolton & Quinn Ltd).

We will continue with an aesthetic and historiographi- cal analysis of art to try to determine the importance of color in visual arts and its condition of need or sufficiency. Moreover, we aim to analyze whether a single color is capable of exerting an influential value to the point of causing real transformations in a work of art.

To conclude, we will analyze the legitimacy of a patent within a left-libertarian system to determine whether the action of Kapoor, Surrey Nanosystems, and the other stakeholders involved in the case is morally permissible.

Case study

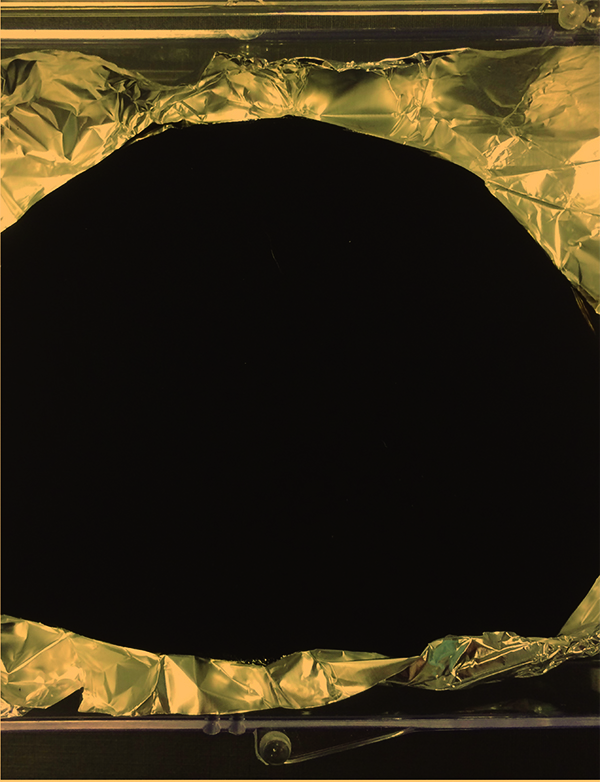

The case study upon which our article is based is that of the Anglo-Indian artist Anish Kapoor (born in 1954). In 2016, he acquired the license to be the only person who can use Vantablack, the blackest artificial mate- rial on Earth, for artistic purposes (Challa, 2017). This artificial material, created by Surrey NanoSystemsin 2014, was first presented at the Farnborough International Airshow (Rogers, 2017).

After requesting additional information from the company regarding the composition of this material, the company responded by claiming that it could not provide it and simply referred to the information published on its website and social networks. There, it can be read thatVantablack is the brand name for a new class of super-black coatings. The coatings are unique in that they all have hemispherical reflectances below 1% and also retain that level of performance from all viewing angles.

The original coating known just as Vantablack® was a super- black coating that holds the independently verified world record as the darkest man-made substance. It was originally developed for satellite-borne blackbody calibration systems, but due to limitations in how it was manufactured its [sic] been surpassed by our spray applied Vantablack coatings.Spray applied Vantablack coatings have unrivalled absorption from ultra-violet out beyond the terahertz spectral range. The totally unique properties of Vantablack coatings are being exploited for applications such as deep space imaging, auto- motive sensing, optical systems, art and aesthetics. (Surrey Nanosystems, n. d.) 1

Following the information published in some media, based on Jason Jensen (CTO at Surrey NanoSystems) as a source, Vantablack comes froma chemical deposition process that laid down the nanotubes, all sticking upward on their ends like blades of grass—a billion of them in a square centimeter. Light comes in as photons, enters the top of the structure, and then the photons bounce around between the carbon nanotubes and get absorbed and converted to heat, and then the heat is dissipated through the substrate. […] The alignment and density of the nanotubes captures photons from the wee wavelengths of ultraviolet to wide, hot infrared—and all the wavelengths of visible light in between. Then they push that energy out the back as heat. With just the barest fraction of photons that hit the stuff bouncing off, even at a glancing angle, practically none reach a human eye and trigger a human brain. So when you look at something coated in Vantablack, you see a blank. A void… (Rogers, 2017).

Obtaining the exclusive right to use the blackest artificial color in artistic activities aroused a certain stir within the art world, particularly among artists. Stuart Semple, for example, was able to create, after Kapoor's action, the world's pinkest pink, the world’s greenest green, and the world’s most glittery glitter (Morby, 2017).A significant feature, however, is that Semple, in retaliation, sold his products to anyone who had no relationship with Kapoor (Rogers, 2017).

Another artist, Christian Furr, declared: “I’ve never heard of an artist monopolising a material. Using pure black in an artwork grounds it.” (Griffiths and Donovan, 2016).

The current contextThe relevance of color as an element of visual arts

Color is a basic and fundamental element of visual arts, which represents the property of electromagne- tic radiation produced when a light source reaches an object and reflects it to our eyes. Yet, when spea- king about art, color takes on features that are not quite definable by physical principles, possessing,to some extent, a charge of subjectivity related to meaning. This phenomenon becomes clearer, for example, when we compare paintings in which the artist intends to represent a feeling of sadness against those that intend to represent a feeling of happiness: while, in the first case, it is common to use colors closer to blue (cold colors), it is more common in the second to use colors closer to orange (hot colors) (Macdonald, 2015). As pointed out by Esaak (2019): “subjectively, then, color is a sensation, a human reac- tion to a hue arising in part from the optic nerve, and in part from education and exposure to color, and perhaps in the largest part, simply from the human senses” (MISSING PAGE NUMBER). Therefore, since color is also a sensation and a human reaction, it is directly connected to how comprehend and inter- pret visual arts.

For example, while observing certain artworks by Delacroix, Charles Baudelaire affirmed that “there is nothing in his work that does not tell about desola- tion” (Baudelaire, 1992). This feeling of anguish in the art of Delacroix as perceived by Baudelaire occurs for different reasons, which include the theme as well as the expressiveness or the colors. In other words, a great part of Delacroix’s art possesses a bleak charac- ter, not only because of the theme presented in his paintings, but also as a consequence of the technical characteristics of the artwork, i.e., the use of colors.The relevance of color for the expression of sensa- tions in art can be seen, for example, in The Scream, Edvard Munch’s acclaimed painting. Besides the curved lines that divert the perspective of order and harmony, the use of orange and yellow in the skyenable a more effective transmission of the charac- terization that the author sought to attribute to his work. The use of hot colors allows emphasizing the heat, the euphoria, and the anguish of the author at the moment of the scream. If cold colors were used instead, the effect would not have the same intensity. This example of Munch’s work also demonstrates the importance of using specific colors in each artwork in order to express sensations and generate effects with greater efficacy.

Still, it is important to note that color had never become the main element of painting, being regar- ded as a secondary element in detriment of form, line, and especially genre, until the rise of abstract expres- sionism (Belton, 1996). It was in the decade of 1950,in the United States of America, that a new style of abstract painting appeared: the Color Field.Color Field is essentially defined as a movement that established color and subjectivity as the main attribute of painting. Color Field painters, such asMark Rothko and Barnett Newman, used to paint vast areas of colors scattered across the canvas, aiming to convey color as the main medium for the artwork to attain the subjectivity of the artist.2Among artists such as Pollock and Newman, Helen Frankenthaler is known to be the precursor ofthe Color Field style.3 While arriving from a trip to Scotland, Frankenthaler painted the artworkMountains and Sea, in which her priority was not to portray the landscape, but the color. She flooded her canvas with pure pigments, in such a way that sudden variations in saturation and intensity were the agents of the aesthetic effect.

In 1964, Clement Greenberg organized the first expo- sition comprising artworks in the Color Field style. He gathered these paintings, for the first time, as a particular style by a list of common stylistic preferences. Greenberg claimed that, among the preferences of this strand of abstract expressionism, both openness and clarity were important. Therefore, high-keyed and lucid colors were preferred. This allowed for "stress contrasts of pure hue rather than contrasts of light and dark," avoiding the use of "thick paint and tactile effects", seeking ways to realize "relatively anony- mous [forms of] execution", and preferring "trued and faired edges simply because they call less attention to themselves as drawing... [and] get out of the way of color" (Moos, 2005, pp. 18-23), even though these qualities could all be attributed to the art style that was later named Color Field painting.

Is there any relevance in only one specific color to an artwork?

Throughout art history, artists have made great com- positions. Nevertheless, others decided to exploit the use of a single color. This decision did not necessarily lead to lack of success. When looking for an artistin which only a single color is relevant, Yves Klein immediately comes to mind. He achieved commercial success and received recognition from art critics.This situation is most uncommon, but it serves us to exemplify that one specific color can be relevant in an artwork.

Most of Klein’s artworks are constituted by only one color: the International Klein Blue, a kind of ultrama- rine blue created by the artist (Sooke, 2014).According to the critics, Klein could reach maxi- mum intensity and deepness of the blue color in his artworks (both in paintings and sculptures). In the words of Yve-Alain Bois:

Klein reached this dream of having the color alone, without mediation, at maximum intensity –so that it could be expe- rienced in the moment only, in the inarticulate moment of the sensation–through a mystical logic that seemed to be in complete opposition to this affirmation of color” (Bois, 2007, p. 90).

In the very same text, Bois quotes an interesting passage on the relevance of monochrome in Klein. In this fragment, Klein himself explains the reason why he chose to use only one color in his works. He says:

Why have I arrived at this blue period? Because, before this, in 1956 at Collette Allendy’s and in 1955, at the Club des Solitaires, I showed some twenty monochrome surfa- ces, each a different color, green, red, yellow, purple, blue, orange... I was aiming to show “color” and I realized at the opening that the viewers were remaining prisoners of theirconditioned way of seeing: in front of all these surfaces of different colors presented on the wall, they kept reconstitu- ting the elements as polychromatic decoration. They could not enter into the contemplation of the color of a single painting at a time, and it was very disappointing to me, for precisely I categorically refuse to have even two colors play on a single surface. In my opinion, two contrasting colors on a single canvas force the viewer not to enter into the sensibility, into the dominant, into the pictorial intention, but rather force him to see the spectacle of the struggle between the two colors, or their perfect harmony. It’s a psychological situation, a sentimental and emotional one, which perpetuates a kind of reign of cruelty. (Bois, 2007, pp. 91-92)

The case of Yves Klein is not the norm, but many other artists became experts in the use of color, and they made of this skill their main identity and value. Nevertheless, being recognized by the use of a single color or a combination of them does not necessarily constitute a condition of sufficiency. It is not even sufficient to grant a unanimous understanding and valuation of the artwork, as John Gage well noted.

John Gage and color

The art historian and ex-professor of the University of Cambridge, John Gage, in his book Color in Art(2006), addressed the topic concerning the relevance and meaning of color in art. There, by presenting a diverse set of examples, he clearly states how relative the meaning of each color can be (Gage, 2000, 2006).

Gage brings uses an illustrative example in which he exposes the contrasts around the comprehension of the color yellow between William Blake, Charles Leadbeater, Goethe, and Kandinsky. For Leadbeater, a priest and theosophist, the color yellow was as yellow as the sun and, for this reason, it was the onerepresented in the halos of angels; yet, for Kandinsky, Goethe, and Blake, yellow represented the very opposite. For Kandinsky, as for most theosophists, blue was the highest and most spiritual color (Heller, 2004), whereas yellow was “the typical earthly color and never contains a profound meaning”, as he himself described it in Concerning the Spiritual in Art (Kandinsky, 1946, p. 63).

What we can clearly see in Gage’s analysis is the explicit difficulty in establishing a color as an objec- tive signifier, as we can also see in Panofsky’s icono- logical method. Panofsky’s iconological notion of interpreting icons/symbols in works of art accordingto the cultural, social, and historical background of the interpreter exposes the subjectivity of his metho- dology (which is directly related to the interpreter’s personal experience). Blue or yellow can, in the same painting, both represent completely different things for different interpreters, and this is also manifest in most abstract expressionist paintings (such as those from drip painting, tachisme, and Color Field).

Furthermore, Gage’s discussion regarding the importance of color in an artwork and the difference it can make accurately illustrates how influential it can be.

The current paradigm of art

After presenting the concept of color as something that is reasonably subjective, we can now address the case study from a left-libertarian perspective: the current paradigm of art from an institutional perspective.

Considering what our society currently refers to as art, it seems that the objects being classified asartworks in spaces for artistic presentation, such as contemporary art museums or contemporary art galleries, are not necessarily linked to the classic aes- thetic categories anymore (the beautiful, the ugly, the sublime, the grotesque...) (Souriau, 1998; Eco, 2004; Ngai, 2015). One of the main authors who realized this was Robert A. Schulz in his 1978 article Does Aesthetics Have Anything to Do with Art? (Schulz, 1978). Danto, 25 years after Schulz asked himself thatquestion –and with the advantages of the perspective of his time– wrote, in the second chapter of his book The Abuse of Beauty:

I regard the discovery that something can be good art without being beautiful as one of the great conceptual clarifications of twentieth-century philosophy of art, thought it was made exclusively by artists –but it would have been seen as commonplace before the Enlightenment gave beauty the primacy it continued to enjoy until relatively recent times.That qualification managed to push reference to aesthetics out of any proposed definition of art, even if the new situation dawned very slowly even in artistic consciousness. (Danto, 2003, p. 58)

These philosophical positions follow the trail of what was defended in some of the avant-garde manifes- tos, such as that of Dadaism –written by Tristan Tzara, in which could be read that “a work of art is neverbeautiful by decree” (Rodal, 2010; Danto, 2004, pp. 24-35).

In fact, some authors have argued that anything can be art, and even that, as a consequence, everyone can be an artist (Redaction, 2001; Vilar, 2005). One of the most important American art critics of the avant-garde period (Clement Greenberg) straightly referred to minimalist artworks as “readable as art, as almost everything today”4 (Greenberg, as cited in Reise, 1992, p. 266).

n this context, precisely to provide an answer to this potential of every object being able to be regarded as an artwork, the institutional theory of art cameto be. The most notorious philosophers known to this theory, such as Arthur Danto and George Dickie, agreed about the difficulty of establishing what art isby means of physical/aesthetical properties and even of establishing a definition of art.5 This theory tries to provide, despite its differences between authors, an answer to the question “When is art?” instead of the traditional “What is art?”. By simplification (although not falsely), it defends that find anything to be art within an institutional system, an art world (or art worlds) (Goodman, 1978, pp.57-70).Considering what has been discussed until now, we have three key elements that serve as a contextual background for our analysis:

1.Despite the problems with defining art, in some cases, color has played a key role in art history;

2.The value of a color is subjective and not absolute;

3.In the current paradigm of art, not even aesthetic (and therefore sensitive) characteristics must necessa- rily be present in what is named art.

An analysis from left-libertarianism

To begin, we have to contextualize what we mean by left-libertarianism. By using this expression, we understand this concept as a political way of thinking that proposes a theory of justice. To summarize the main statement of this theory of justice, it could be said that an action is unjust if and only if others are morally permitted to coerce one not to perform it (Vallentyne and Steiner, 2000).6

In this context, we are using the term justice and its derivates (such as just or unjust) as “the system of laws in a country that judges and punishes people” (Cambridge, n.d.), not as something linked to the concept of fairness.7

This is an important remark since, throughout this article, the use of justice will be linked to a moral coercive permission allowed by law. Therefore, we are in a non-positivist perspective of what law is.8 (Dworkin, 1986).

As a form of libertarianism, left-libertarianism recog- nizes the existence of certain basic rights, which are strictly linked to property rights.These property rights must be divided into:

1.rational chooser’s agents

2.natural resources, and

3. artifacts. (Dworkin, 1986; Penner and Otsuka, 2018)

According to libertarianism, we can classify an agent as a self-chooser when the agent has the following properties: firstly, (1) he/she is fully self-ownership and therefore has the right to decide what things are done to him/her; secondly, (2) this agent has the right to transfer that right to others. However, from a left-li- bertarian perspective, this does not mean that other agents always have the right to acquire these rights, especially when their acquisition limits the protection of the exercise of autonomy (regardless of the effec- tive autonomy) (Vallentyne and Steiner, 2000).

These two elements are key to the analysis of our case study. Its importance lies in the fact that none of the agents directly involved in our case study, at the time it took place, had a limitation in their own self-choosing right.9

With the data that we have available, Anish Kapoor had all the legal right and total intellectual and physi- cal capacity to contact Surrey Nanosystems in order to inquire whether the satisfaction of his interests was possible.

Surrey Nanosystems, as an agent conformed by the agglomeration of individual beings, also had, within the framework of a given legal context, the right to offer its product to those who they considered most appropriate.

On the other hand, Semple and Furr, as well as the other artists –self-choosing beings with total physical and intellectual capacity– were free, at all times, to perform the same action carried out by Anish Kapoor before he did it.

It is important to remark that all the agents involved in our case study, at the time of the action, shared the same potential level of intellectual capacity. By this, we mean that none of them is considered to be a sentient being with no potential for agency, a sen- tient being with no agency but with the potential for full agency, nor a sentient being with partial agency (Vallentyne and Steiner, 2000).

This should reduce possible counterarguments of temporary and act/potency nature (Aristotle, 1986).

Another potential counterargument to what is pre- sented here is that, perhaps, Semple, Furr, and the other agents did not have the economic capacity to choose freely. This could be justified upon the basis that they did not have the same financial resources as Anish Kapoor to acquire the exclusive right to use Vantablack for artistic practices. However, this is only a conjecture since the price for which the company sold the right to the Anglo-Indian artist has not been made public.

What seems clear is that, within a legal system in which patents are allowed with the objective (effec- tive or not) of promoting incentives for research, development, and innovation, Surrey Nanosystems decided to develop a new product.10

This has been possible through individual agents (such as engineers or chemists). These ones, in the exercise of their self- choice, decided to sell a portion of their intellectual resources and time in exchange for an economic compensation that they, as free and rational indi- viduals, deemed appropriate.11

The choice of the development of Vantablack by Surrey Nanosystems was also free and without coercion. The result ofthis is a morally acceptable artifact from a libertarian perspective.

Following the description cited in previous pages, and quoting Jason Jensen (CTO at SurreyNanoSystems), there is no doubt that Vantablack is an artifact. In consequence, it should be understood as a “produced non-agent resource” for which “unpro- duced non-agent resources” (natural resources) are indispensable (Vallentyne and Steiner, 2000, p.7).

The acquisition of this artifact is also moral, as long as it is not possible, within the presented framework, to coercively prevent the action of the agents invol- ved in the commercial activity at the center of our case study. With the exclusive appropriation of thisright, Kapoor did not even monopolize the possibility of being an artist or creating art. This is because, as we presented earlier, the use of a certain color is a condition of possibility for art, but not of necessity.In consequence, possible objections claiming that Kapoor's action prevents the creation of art are inconsistent in absolute terms12. In addition, since,in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, arts and crafts became different categories –as the concept of artist/craftsman linked to a guild was abandoned– the principle of competitiveness was more present than ever. As a consequence, the regrets of Furr's wishing to use other resources has obvious ties with envy and the irrational desire to possess what he cannot have13. This claim, in fact, acts against the current market paradigm –and, by extension, the art market. This is due to the fact that, in our case, the artist

competes by offering a product which the customers [the collectors] perceive as more valuable than the competi- tors’ products […] offering a product that differs from other products in quality, […] design, […] durability, taste or whate- ver. If buyers recognize the additional value [the artist or the artistic organization] can charge a higher price. (Douma and Schreuder, 1992, p. 129).

At this point, it is time to delve into the essential element that remains to be addressed: that of natural resources.As with any artifact, a certain transformative work with a certain natural resource is necessary.From the perspective of unilateralist libertarianism, the first agent to find natural resources not appro- priated by others has the right to use and exploit them.14 This could be extremely simplified as: ‘the first one who arrives, owns it’, and here our article would end. However, this would not be a critical approach. This is due to the fact that, within unilate- ralist libertarianism, some authors defend that those agents who self-appropriate unappropriated natural resources should not have any obligation to com- pensate the rest of society for that exploitation.15 From the viewpoint of left-libertarianism the natural resources are common joint good. This means that the agent that acquires them acquires, in turn, cer- tain moral duties.16 Obviously, these duties would depend on whether these resources are renewable or non-renewable, while the social impact of the useelse’s belonging’ refers, in this case, to Surrey Nanosystem’s rights derived from Vantablack’s patent and exploitation of one or the other is considerably different.17

In this sense, without having more specific data, it must be assumed that both Anish Kapoor and Surrey Nanosystems pay their corresponding direct and indirect taxes required by the law. Defending the opposite would be an unprovable accusation.As a consequence, the payment of these taxes would serve the State (in theory) to benefit society and the reduce damages (e.g., in the form of negative exter- nalities as environmental or third part costs) that this appropriation of natural resources and the subse- quent creation and acquisition of the Vantablack artifact could have generated.18

In fact, the payment of direct taxes based on income and surplus would eliminate a possible criticism from a geolibertarian perspective.19

In turn, we must assume, without more specific data, that the companies responsible for providing natural resources to Surrey Nanosystems also comply with the legal and fiscal policies of their context, including the payment of the ‘resourcerent’ when and where necessary (Rawls, 1971). Consequently, our case study seems to be morally permissible from a left-libertarian perspective.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have discussed Anish Kapoor’s action of acquiring the license to be the only artist who can use Vantablack (the blackest artificial material on Earth) for artistic practices. We conclu- ded that this action was morally permissible from any perspective of libertarianism, which includes left-libertarianism.

To this effect, we first discussed the relevance of color in visual arts, arguing that color has a charge of subjectivity that is contained within its capacity of promoting feelings and sensations. Afterwards, still on the topic of the relevance of color, we brought up Yves Klein’s use of a single color in his artworks (which came to be known as the International Klein Blue).Then, already knowing about the relevance of color in art, we took left-libertarianism’s theory of justice as our starting point (as it is the most demanding liberta- rian theory regarding the supply). We assumed that “an action is unjust if and only if others are morally per- mitted to coerce one not to perform it” (Vallentyne and Steiner, 2000, p. 2).

Another assumption that was made was related to the existence of basic rights linked to property rights, which can be divided into the following categories:

rational chooser’s agents,natural resources, andartifacts.Importar listaIn this way, according to libertarianism, for an agent to be considered a self-chooser agent, they mustbe fully self-owned

b.have the right to decide what things are done to them), andhave the right to transfer their rights in order to decide what things are done to them or others

These properties are key to analyzing the reason why Kapoor’s action was not immoral and consequently permissible. It is so because (P1) the agents involved in our case study (Anish Kapoor, Surrey Nanosystems and its employees, and the artists who reacted tothe action as Stuart Semple or Christian Furr) had no limitation in their own self-choosing right at the time when it took place. That is, all of them had all the phy- sical and intellectual capacity to make a conscious decision, sharing the same level of intellectual capa- city. Then, we can say that (P2) all agents involved in the case were fully self-owned.

Therefore, from a unilateralist libertarian perspective, we can extract the following argument from what has been said:

(P1) Being a just action is a disjunctive property in relation to being an immoral action.

(P2) An action can be considered a just action if all the agents performing this action are self-chooser agents.

(P3) An agent x is a self-chooser agent when x is fully self-owned (i.e., they have the right to decide what things are done to them).

(P4) All agents involved in Kapoor’s case were fully self-owned.

(C1) All agents involved in Kapoor’s case were performing a just action.

Thus, from a unilateralist libertarian perspective, which stipulates that the first agent to find natural resources not appropriated by others has the right to use and exploit them, Kapoor’s action is clearly a fair action, although, from a left-libertarian perspective, natural resources are a common good. Then, when an agent acquires them, they also acquire, in turn, certain moral duties.

That said, we argued that, without having more spe- cific data, it is very likely that (P1’) Kapoor and Surrey Nanosystems carried out the action within the legality. Then, when Anish Kapoor acquired Vantablack from Surrey Nanosystems, we can assume that (P2’) bothof them paid their due direct and the indirect taxes required by law. Then, theoretically, (P3’) these taxes are going to serve the State in benefitting society through its policies. Therefore, (C2) Kapoor and Surrey Nanosystems are meeting their moral duties when acquiring a product made of natural resources. That said, they are also performing a just action accor- ding to the left-libertarian perspective.

Thereupon, we can conclude that Anish Kapoor’s action of acquiring the license to be the only artist who can use Vantablack was morally permissible from any perspective of libertarianism.

On the other hand, we should admit that, as the topic has such complexity, it was not possible for us to approach it in its entirety –as this text constitutes a limited argumentation. There are many other things of potential interest that can be explored in depth about this topic. Some of these potentially valuable perspectives on the subject emerged during this research. It is important to say, for example, that weused only one context and generation; we could have discussed if the libertarian theory framework used is based on a system of law and moral implications that were not directly voted and constitute a self-choice.

Furthermore, we found that Kapoor’s action did not make it impossible for someone to become an artist. Nevertheless, it is true that it restricted thepossibilities of other artists, but he did not restrict the total creation of art. However, restricting some possibilities of other artists to express themselves in the way that they want could be considered to besome sort of censorship, since it can imply an attempt to suppress some way of artistic expression. From this perspective, which is not ours, it could be defended that Kapoor is censoring by preventing other artists from using a specific color or material –and censors- hip is immoral according to libertarianism.

Note

During the writing of this article (2019-2020), Stuart Semple created a new black color, Black 3.0, which surpassed Vantablack 2.0.Again, Kapoor and his associates have been banned from purchasing it (Cascone 2019).More recently, the MIT created a new material, even blacker than Vantablack 2.0 and Black 3.0. It is being used in artistic practices by Diemut Strebe (Chu, 2019). However, we do not consider that these new creations make the philosophical and moral discus- sion of the case study less relevant.

References

Aquinas, T. (1993). The treatise on law: Being Summa Theologiae, I-II. QQ. 90 through 97. Notre Dame, IN, USA: University of Notre Dame Press.

Aristotle. (1986). De anima. Middlesex, NJ, USA: Penguin Books.

Aristotle. (2018). Rhetoric. Cambridge, UK: Hackett Publishing Company Inc.

Baudelaire, C. (1992). Selected writings on art and literature. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Becker, H. S. (2008). Art worlds. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press.

Belton, R. (1996). Art History: A Preliminary Handbook. Vancouver, BC, Canada: University of British Columbia.

Bois, Y. (2007). Klein's relevance for today. October, 119, 75-93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40368459

Cambridge (n.d.) Appropriation. In Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/appropriation

Cambridge (n.d.) Justice. In Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/justice

Cambridge (n.d.) Libertarianism. In Cambridge Dictionary. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/libertarianism/#PowerApp

Cambridge (n.d.) Resource. In Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/resource

Cascone, S. (2019, January 30). Anish Kapoor owns the rights to the blackest color ever made. So another artist made his own superblack –and now it’s even blacker. Artnet. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/stuart-semple-blackest-black-anish-kapoor-1452259

Challa, J. (2017, July 11). “hy everybody's mad at Anish Kapoor. The Architect’s Newspaper. https://archpaper.com/2017/07/anish-kapoor-blackest-black/

Chu, J. (2019, September 12). MIT engineers develop “blackest black” material to date. MIT News. https://news.mit.edu/2019/blackest-black-material-cnt-0913

Danto, A. C. (1964). The Artworld. The Journal of Philosophy, 61(19), 571-584. https://doi.org/10.2307/2022937

Danto, A. C. (2003). The abuse of beauty: Aesthetics and the concept of art. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press.

Danto, A. C. (2004). Kalliphobia in Contemporary Art. Art Journal, 63(2), 24-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2004.10791123

Dickie, G. (1974). Art and the aesthetic: An institutional analysis. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell University Press.

Douma, S., and Schreuder, H. (1992). Economic approaches to organizations. New York, NY, USA: Prentice Hall.

Dworkin, R. (1986). Law's empire. Cambridge, UK: Belknap Press.

Eco, U. (2004). On beauty. London, UK: Secker & Warburg.

Esaak, S. (2019, August 17). What is the definition of color in art? ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/definition-of-color-in-art-182429

Fried, M. (1967). Art and objecthood. New York, NY, USA: Garland Pub. Co.

Gage, J. (2006). Color in art. New York, NY, USA: Thames & Hudson.

Gage, J. (2000). Color and meaning: Art, science, and symbolism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Goodman, N. (1978). Ways of worldmaking. Indianapolis, IN, USA: Hackett Publishing Company.

Griffiths, C., and Donovan, N. (2016, February 27). Artists at war after top sculptor is given exclusive rights to the purest black paint ever which is used on stealth jets. Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3467507/Artists-war-sculptor-given-exclusive-rights-purest-black-paint-used-stealth-jets.html

Hart, H. L. A. (2012). The concept of law. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hart, H. L. A. (1958). Positivism and the separation of law and morals. Harvard Law Review, 71(4), 593-629. https://doi.org/10.2307/1338225

Hayter, R., and Patchell, J. (2016). Economic geography: an institutional approach. Don Mills, ON, Canada: Oxford University Press.

Heller, E. (2004). Psicología del color: cómo actúan los colores sobre los sentimientos y la razón. Barcelona, Spain: Gustavo Gili.

Kandinsky, W. (1946). Concerning the spiritual in art. New York, NY, USA: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Kirzner, I. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Macdonald, C. (2015). What is colour? a defence of colour primitivism. In R. Johnson and M. Smith (Eds.), Passions and Projections (pp. 116-133). New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

Moos, D. (2005). The shape of colour: Excursions in colour field art 1950-2005. Toronto, ON, Canada: Art Gallery of Ontario.

Morby, A. (2017, July 07). Anish Kapoor banned from using colour-changing paint in ongoing rights war. Dezeen. https://www.dezeen.com/2017/07/07/anish-kapoor-banned-from-using-stuart-semple-colour-changing-paint-design-news/

Ngai, S. (2015). Our aesthetic categories. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press.

Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, state, and utopia. New York, NY, USA: Basic Books.

Penner, J., and Otsuka, M. (Eds.) (2018). Property theory: Legal and political perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Pownall, R., and Graddy, K. (2016). Pricing color intensity and lightness in contemporary art auctions. Research in Economics, 70(3), 412-420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rie.2016.06.007

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge, UK: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Redaction. (2001, October 20). 'Everyone's an artist, anything can be art. The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/4726169/Everyones-an-artist-anything-can-be-art.html

Reise, B. (1992). Greenberg and the group: A retrospective view. In F. Frascina and J. Harris (Eds.), Art in modern culture: An anthology of critical texts (pp. 252-264). New York, NY, USA: Harper Collins.

Rodal, C. (2010). Manifiesto y vanguardia: los manifiestos del futurismo italiano, dadá y el surrealismo. Bilbao, Spain: University of the Basque Country, Publishing Services.

Rogers, A. (2017, June 22). Art Fight! The Pinkest Pink Versus the Blackest Black. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/vantablack-anish-kapoor-stuart-semple/

Rollins, M. (Ed.) (2012). Danto and his critics. Malden, MA, USA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Rothbard, M. (1978). For a new liberty: the libertarian manifesto. New York, NY, USA: Collier Books.

Rothbard, M. (1982). The ethics of liberty. Atlantic Highlands, NJ, USA: Humanities Press.

Sala-i-Martín, X. (2017). Economía liberal para no economistas y no liberales. Barcelona, Spain: Penguin Random House Mondadori.

Schulz, R. A. (1978). Does Aesthetics have anything to do with Art? Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 36(4), 429-440. https://doi.org/10.2307/430483

Sooke, A. (2014, August 28). Yves Klein, the man who invented a colour. BBC. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140828-the-man-who-invented-a-colour

Souriau, É. (1998). Diccionario Akal de Estética. Madrid, Spain: Akal.

Vallentyne, P. and Steiner, H. (2000). Left-libertarianism and its critics: the contemporary debate. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave.

van der Bossen (2019). Libertarianism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/libertarianism/#PowerApp

Vilar, G. (2005). Las razones del arte. Boadilla del Monte, Spain: A. Machado Libros.

Notas

Recibido: 12 de septiembre de 2021; Aceptado: 11 de diciembre de 2021

Resumen

En este texto realizamos un análisis de las acciones del artista angloíndio Anish Kapoor, quien adquirió el derecho a ser el único artista que puede utilizar el material más oscuro del mundo. Esto tuvo un gran impacto y generó discusiones dentro del mundo del arte.

Algunos artistas crearon el color más verde del mundo, el más rosado del mundo o el más brillante del mundo y permitieron que todas las personas lo compraran, excepto Kapoor y sus asociados. Presentamos un análisis desde la perspectiva del libertarismo de izquierda sobre si la acción de Kapoor es moral o no. Para ello, el texto se divide en dos partes: la primera es un análisis del papel del color en la historia del arte y la segunda aborda la legitimidad de las patentes y la acción de Kapoor.

Palabras clave

Estética, Oscuro, Ética, Moral, Filosofía del Arte, Filosofía del Derecho.Abstract

In this text, we carry out an analysis of the actions of Anglo-Indian artist Anish Kapoor, who acquired the right to be the only artist who can use the darkest material in the world. This had a great impact and generated discussions within the art world. Some artists created the world's greenest color, the world's pinkest color, or the world's brightest color and allowed all individuals except Kapoor and his associates to purchase it. We present an analysis from the perspective of Left-Libertarianism on whether Kapoor's action is moral or not. To this effect, the text is divided in two parts: the first is an analysis of the role of color in art history, and the second addresses the legitimacy of patents and Kapoor's action.

Keywords

Mapping, public space, artistic practices, cultural resistance.Résumé

Dans ce texte nous effectuons une analyse de l'action menée par l'artiste anglo-indien Anish Kapoor. Kapoor a acquis le droit d'être le seul artiste capable d'utiliser le matériau le plus noir du monde. Cette action a généré un vaste impact et des discussions au sein du monde de l'art. Certains artistes ont créé la couleur la plus verte du monde, la couleur la plus rose du monde ou la couleur la plus brillante du monde et ont permis à tous les individus sauf Kapoor et ses associés de l'acheter.

Nous présentons une analyse du point de vue du libertarismede gauche sur la question de savoir si l'action de Kapoor est morale ou non. Pour ce faire, le texte est divisé en deux parties distinctes. La première est une analyse du rôle de la couleur dans l'histoire de l'art. La seconde présente la légitimité des brevets et de l'action de Kapoor.

Mots clés

Esthétique, noir, éthique, moral, philosophie de l'art, philosophie du droit.Resumo

Neste texto realizamos uma análise das ações do artista anglo-indiano Anish Kapoor, quem adquiriu o direito de ser o único artista que pode utilizar o material mais obscuro do mundo. Isto teve um grande impacto e gerou discussões dentro do mundo da arte. Alguns artistas criaram a cor mais verde do mundo, a mais rosada do mundo ou a mais brilhante do mundo e permitiram que todos as pessoas as comprassem, exceto Kapoor e os seus associados.

Apresentamos uma análise desde a perspectiva do libertarismo de esquerda sobre se a ação de Kapoor é moral ou não. Para este fim, o texto se divide em duas partes: a primeira é uma análise do papel da cor na história da arte e a segunda trata da legitimidade das patentes e da ação de Kapoor.

Palavras-chave

Estética, Obscuro, Ética, Moral, Filosofia da Arte, Filosofia do Direito.Introduction

In the first part of this article, we present an analysis, from a left-libertarian perspective, of an action carried out by artist Anish Kapoor, who acquired the exclusive right to use the world's blackest material from the company Surrey Nanosystems.

To this end, this text will articulate fields such as aes- thetics, art philosophy, moral philosophy, ethics, and the art market –especially from the institutional theory of art.

In the first place, we will present the case descripti- vely, based on the media coverage. In addition, to verify that the case is presented from duly reliable data, the text was sent to Anish Kapoor through his representative, Erica Bolton (Bolton & Quinn Ltd).

We will continue with an aesthetic and historiographi- cal analysis of art to try to determine the importance of color in visual arts and its condition of need or sufficiency. Moreover, we aim to analyze whether a single color is capable of exerting an influential value to the point of causing real transformations in a work of art.

To conclude, we will analyze the legitimacy of a patent within a left-libertarian system to determine whether the action of Kapoor, Surrey Nanosystems, and the other stakeholders involved in the case is morally permissible.

Case study

The case study upon which our article is based is that of the Anglo-Indian artist Anish Kapoor (born in 1954). In 2016, he acquired the license to be the only person who can use Vantablack, the blackest artificial mate- rial on Earth, for artistic purposes (Challa, 2017). This artificial material, created by Surrey NanoSystemsin 2014, was first presented at the Farnborough International Airshow (Rogers, 2017).

After requesting additional information from the company regarding the composition of this material, the company responded by claiming that it could not provide it and simply referred to the information published on its website and social networks. There, it can be read thatVantablack is the brand name for a new class of super-black coatings. The coatings are unique in that they all have hemispherical reflectances below 1% and also retain that level of performance from all viewing angles.

The original coating known just as Vantablack® was a super- black coating that holds the independently verified world record as the darkest man-made substance. It was originally developed for satellite-borne blackbody calibration systems, but due to limitations in how it was manufactured its [sic] been surpassed by our spray applied Vantablack coatings.Spray applied Vantablack coatings have unrivalled absorption from ultra-violet out beyond the terahertz spectral range. The totally unique properties of Vantablack coatings are being exploited for applications such as deep space imaging, auto- motive sensing, optical systems, art and aesthetics. (Surrey Nanosystems, n. d.) 1

Following the information published in some media, based on Jason Jensen (CTO at Surrey NanoSystems) as a source, Vantablack comes froma chemical deposition process that laid down the nanotubes, all sticking upward on their ends like blades of grass—a billion of them in a square centimeter. Light comes in as photons, enters the top of the structure, and then the photons bounce around between the carbon nanotubes and get absorbed and converted to heat, and then the heat is dissipated through the substrate. […] The alignment and density of the nanotubes captures photons from the wee wavelengths of ultraviolet to wide, hot infrared—and all the wavelengths of visible light in between. Then they push that energy out the back as heat. With just the barest fraction of photons that hit the stuff bouncing off, even at a glancing angle, practically none reach a human eye and trigger a human brain. So when you look at something coated in Vantablack, you see a blank. A void… (Rogers, 2017).

Obtaining the exclusive right to use the blackest artificial color in artistic activities aroused a certain stir within the art world, particularly among artists. Stuart Semple, for example, was able to create, after Kapoor's action, the world's pinkest pink, the world’s greenest green, and the world’s most glittery glitter (Morby, 2017).A significant feature, however, is that Semple, in retaliation, sold his products to anyone who had no relationship with Kapoor (Rogers, 2017).

Another artist, Christian Furr, declared: “I’ve never heard of an artist monopolising a material. Using pure black in an artwork grounds it.” (Griffiths and Donovan, 2016).

The current context The relevance of color as an element of visual arts

Color is a basic and fundamental element of visual arts, which represents the property of electromagne- tic radiation produced when a light source reaches an object and reflects it to our eyes. Yet, when spea- king about art, color takes on features that are not quite definable by physical principles, possessing,to some extent, a charge of subjectivity related to meaning. This phenomenon becomes clearer, for example, when we compare paintings in which the artist intends to represent a feeling of sadness against those that intend to represent a feeling of happiness: while, in the first case, it is common to use colors closer to blue (cold colors), it is more common in the second to use colors closer to orange (hot colors) (Macdonald, 2015). As pointed out by Esaak (2019): “subjectively, then, color is a sensation, a human reac- tion to a hue arising in part from the optic nerve, and in part from education and exposure to color, and perhaps in the largest part, simply from the human senses” (MISSING PAGE NUMBER). Therefore, since color is also a sensation and a human reaction, it is directly connected to how comprehend and inter- pret visual arts.

For example, while observing certain artworks by Delacroix, Charles Baudelaire affirmed that “there is nothing in his work that does not tell about desola- tion” (Baudelaire, 1992). This feeling of anguish in the art of Delacroix as perceived by Baudelaire occurs for different reasons, which include the theme as well as the expressiveness or the colors. In other words, a great part of Delacroix’s art possesses a bleak charac- ter, not only because of the theme presented in his paintings, but also as a consequence of the technical characteristics of the artwork, i.e., the use of colors.The relevance of color for the expression of sensa- tions in art can be seen, for example, in The Scream, Edvard Munch’s acclaimed painting. Besides the curved lines that divert the perspective of order and harmony, the use of orange and yellow in the skyenable a more effective transmission of the charac- terization that the author sought to attribute to his work. The use of hot colors allows emphasizing the heat, the euphoria, and the anguish of the author at the moment of the scream. If cold colors were used instead, the effect would not have the same intensity. This example of Munch’s work also demonstrates the importance of using specific colors in each artwork in order to express sensations and generate effects with greater efficacy.

Still, it is important to note that color had never become the main element of painting, being regar- ded as a secondary element in detriment of form, line, and especially genre, until the rise of abstract expres- sionism (Belton, 1996). It was in the decade of 1950,in the United States of America, that a new style of abstract painting appeared: the Color Field.Color Field is essentially defined as a movement that established color and subjectivity as the main attribute of painting. Color Field painters, such asMark Rothko and Barnett Newman, used to paint vast areas of colors scattered across the canvas, aiming to convey color as the main medium for the artwork to attain the subjectivity of the artist.2Among artists such as Pollock and Newman, Helen Frankenthaler is known to be the precursor ofthe Color Field style.3 While arriving from a trip to Scotland, Frankenthaler painted the artworkMountains and Sea, in which her priority was not to portray the landscape, but the color. She flooded her canvas with pure pigments, in such a way that sudden variations in saturation and intensity were the agents of the aesthetic effect.

In 1964, Clement Greenberg organized the first expo- sition comprising artworks in the Color Field style. He gathered these paintings, for the first time, as a particular style by a list of common stylistic preferences. Greenberg claimed that, among the preferences of this strand of abstract expressionism, both openness and clarity were important. Therefore, high-keyed and lucid colors were preferred. This allowed for "stress contrasts of pure hue rather than contrasts of light and dark," avoiding the use of "thick paint and tactile effects", seeking ways to realize "relatively anony- mous [forms of] execution", and preferring "trued and faired edges simply because they call less attention to themselves as drawing... [and] get out of the way of color" (Moos, 2005, pp. 18-23), even though these qualities could all be attributed to the art style that was later named Color Field painting.

Is there any relevance in only one specific color to an artwork?

Throughout art history, artists have made great com- positions. Nevertheless, others decided to exploit the use of a single color. This decision did not necessarily lead to lack of success. When looking for an artistin which only a single color is relevant, Yves Klein immediately comes to mind. He achieved commercial success and received recognition from art critics.This situation is most uncommon, but it serves us to exemplify that one specific color can be relevant in an artwork.

Most of Klein’s artworks are constituted by only one color: the International Klein Blue, a kind of ultrama- rine blue created by the artist (Sooke, 2014).According to the critics, Klein could reach maxi- mum intensity and deepness of the blue color in his artworks (both in paintings and sculptures). In the words of Yve-Alain Bois:

Klein reached this dream of having the color alone, without mediation, at maximum intensity –so that it could be expe- rienced in the moment only, in the inarticulate moment of the sensation–through a mystical logic that seemed to be in complete opposition to this affirmation of color” (Bois, 2007, p. 90).

In the very same text, Bois quotes an interesting passage on the relevance of monochrome in Klein. In this fragment, Klein himself explains the reason why he chose to use only one color in his works. He says:

Why have I arrived at this blue period? Because, before this, in 1956 at Collette Allendy’s and in 1955, at the Club des Solitaires, I showed some twenty monochrome surfa- ces, each a different color, green, red, yellow, purple, blue, orange... I was aiming to show “color” and I realized at the opening that the viewers were remaining prisoners of theirconditioned way of seeing: in front of all these surfaces of different colors presented on the wall, they kept reconstitu- ting the elements as polychromatic decoration. They could not enter into the contemplation of the color of a single painting at a time, and it was very disappointing to me, for precisely I categorically refuse to have even two colors play on a single surface. In my opinion, two contrasting colors on a single canvas force the viewer not to enter into the sensibility, into the dominant, into the pictorial intention, but rather force him to see the spectacle of the struggle between the two colors, or their perfect harmony. It’s a psychological situation, a sentimental and emotional one, which perpetuates a kind of reign of cruelty. (Bois, 2007, pp. 91-92)

The case of Yves Klein is not the norm, but many other artists became experts in the use of color, and they made of this skill their main identity and value. Nevertheless, being recognized by the use of a single color or a combination of them does not necessarily constitute a condition of sufficiency. It is not even sufficient to grant a unanimous understanding and valuation of the artwork, as John Gage well noted.

John Gage and color

The art historian and ex-professor of the University of Cambridge, John Gage, in his book Color in Art(2006), addressed the topic concerning the relevance and meaning of color in art. There, by presenting a diverse set of examples, he clearly states how relative the meaning of each color can be (Gage, 2000, 2006).

Gage brings uses an illustrative example in which he exposes the contrasts around the comprehension of the color yellow between William Blake, Charles Leadbeater, Goethe, and Kandinsky. For Leadbeater, a priest and theosophist, the color yellow was as yellow as the sun and, for this reason, it was the onerepresented in the halos of angels; yet, for Kandinsky, Goethe, and Blake, yellow represented the very opposite. For Kandinsky, as for most theosophists, blue was the highest and most spiritual color (Heller, 2004), whereas yellow was “the typical earthly color and never contains a profound meaning”, as he himself described it in Concerning the Spiritual in Art (Kandinsky, 1946, p. 63).

What we can clearly see in Gage’s analysis is the explicit difficulty in establishing a color as an objec- tive signifier, as we can also see in Panofsky’s icono- logical method. Panofsky’s iconological notion of interpreting icons/symbols in works of art accordingto the cultural, social, and historical background of the interpreter exposes the subjectivity of his metho- dology (which is directly related to the interpreter’s personal experience). Blue or yellow can, in the same painting, both represent completely different things for different interpreters, and this is also manifest in most abstract expressionist paintings (such as those from drip painting, tachisme, and Color Field).

Furthermore, Gage’s discussion regarding the importance of color in an artwork and the difference it can make accurately illustrates how influential it can be.

The current paradigm of art

After presenting the concept of color as something that is reasonably subjective, we can now address the case study from a left-libertarian perspective: the current paradigm of art from an institutional perspective.

Considering what our society currently refers to as art, it seems that the objects being classified asartworks in spaces for artistic presentation, such as contemporary art museums or contemporary art galleries, are not necessarily linked to the classic aes- thetic categories anymore (the beautiful, the ugly, the sublime, the grotesque...) (Souriau, 1998; Eco, 2004; Ngai, 2015). One of the main authors who realized this was Robert A. Schulz in his 1978 article Does Aesthetics Have Anything to Do with Art? (Schulz, 1978). Danto, 25 years after Schulz asked himself thatquestion –and with the advantages of the perspective of his time– wrote, in the second chapter of his book The Abuse of Beauty:

I regard the discovery that something can be good art without being beautiful as one of the great conceptual clarifications of twentieth-century philosophy of art, thought it was made exclusively by artists –but it would have been seen as commonplace before the Enlightenment gave beauty the primacy it continued to enjoy until relatively recent times.That qualification managed to push reference to aesthetics out of any proposed definition of art, even if the new situation dawned very slowly even in artistic consciousness. (Danto, 2003, p. 58)

These philosophical positions follow the trail of what was defended in some of the avant-garde manifes- tos, such as that of Dadaism –written by Tristan Tzara, in which could be read that “a work of art is neverbeautiful by decree” (Rodal, 2010; Danto, 2004, pp. 24-35).

In fact, some authors have argued that anything can be art, and even that, as a consequence, everyone can be an artist (Redaction, 2001; Vilar, 2005). One of the most important American art critics of the avant-garde period (Clement Greenberg) straightly referred to minimalist artworks as “readable as art, as almost everything today” 4 (Greenberg, as cited in Reise, 1992, p. 266).

n this context, precisely to provide an answer to this potential of every object being able to be regarded as an artwork, the institutional theory of art cameto be. The most notorious philosophers known to this theory, such as Arthur Danto and George Dickie, agreed about the difficulty of establishing what art isby means of physical/aesthetical properties and even of establishing a definition of art. 5 This theory tries to provide, despite its differences between authors, an answer to the question “When is art?” instead of the traditional “What is art?”. By simplification (although not falsely), it defends that find anything to be art within an institutional system, an art world (or art worlds) (Goodman, 1978, pp.57-70).Considering what has been discussed until now, we have three key elements that serve as a contextual background for our analysis:

1.Despite the problems with defining art, in some cases, color has played a key role in art history;

2.The value of a color is subjective and not absolute;

3.In the current paradigm of art, not even aesthetic (and therefore sensitive) characteristics must necessa- rily be present in what is named art.

An analysis from left-libertarianism

To begin, we have to contextualize what we mean by left-libertarianism. By using this expression, we understand this concept as a political way of thinking that proposes a theory of justice. To summarize the main statement of this theory of justice, it could be said that an action is unjust if and only if others are morally permitted to coerce one not to perform it (Vallentyne and Steiner, 2000). 6

In this context, we are using the term justice and its derivates (such as just or unjust) as “the system of laws in a country that judges and punishes people” (Cambridge, n.d.), not as something linked to the concept of fairness. 7

This is an important remark since, throughout this article, the use of justice will be linked to a moral coercive permission allowed by law. Therefore, we are in a non-positivist perspective of what law is. 8 (Dworkin, 1986).

As a form of libertarianism, left-libertarianism recog- nizes the existence of certain basic rights, which are strictly linked to property rights.These property rights must be divided into:

1.rational chooser’s agents

2.natural resources, and

3. artifacts. (Dworkin, 1986; Penner and Otsuka, 2018)

According to libertarianism, we can classify an agent as a self-chooser when the agent has the following properties: firstly, (1) he/she is fully self-ownership and therefore has the right to decide what things are done to him/her; secondly, (2) this agent has the right to transfer that right to others. However, from a left-li- bertarian perspective, this does not mean that other agents always have the right to acquire these rights, especially when their acquisition limits the protection of the exercise of autonomy (regardless of the effec- tive autonomy) (Vallentyne and Steiner, 2000).

These two elements are key to the analysis of our case study. Its importance lies in the fact that none of the agents directly involved in our case study, at the time it took place, had a limitation in their own self-choosing right. 9

With the data that we have available, Anish Kapoor had all the legal right and total intellectual and physi- cal capacity to contact Surrey Nanosystems in order to inquire whether the satisfaction of his interests was possible.

Surrey Nanosystems, as an agent conformed by the agglomeration of individual beings, also had, within the framework of a given legal context, the right to offer its product to those who they considered most appropriate.

On the other hand, Semple and Furr, as well as the other artists –self-choosing beings with total physical and intellectual capacity– were free, at all times, to perform the same action carried out by Anish Kapoor before he did it.

It is important to remark that all the agents involved in our case study, at the time of the action, shared the same potential level of intellectual capacity. By this, we mean that none of them is considered to be a sentient being with no potential for agency, a sen- tient being with no agency but with the potential for full agency, nor a sentient being with partial agency (Vallentyne and Steiner, 2000).

This should reduce possible counterarguments of temporary and act/potency nature (Aristotle, 1986).

Another potential counterargument to what is pre- sented here is that, perhaps, Semple, Furr, and the other agents did not have the economic capacity to choose freely. This could be justified upon the basis that they did not have the same financial resources as Anish Kapoor to acquire the exclusive right to use Vantablack for artistic practices. However, this is only a conjecture since the price for which the company sold the right to the Anglo-Indian artist has not been made public.

What seems clear is that, within a legal system in which patents are allowed with the objective (effec- tive or not) of promoting incentives for research, development, and innovation, Surrey Nanosystems decided to develop a new product. 10

This has been possible through individual agents (such as engineers or chemists). These ones, in the exercise of their self- choice, decided to sell a portion of their intellectual resources and time in exchange for an economic compensation that they, as free and rational indi- viduals, deemed appropriate. 11

The choice of the development of Vantablack by Surrey Nanosystems was also free and without coercion. The result ofthis is a morally acceptable artifact from a libertarian perspective.

Following the description cited in previous pages, and quoting Jason Jensen (CTO at SurreyNanoSystems), there is no doubt that Vantablack is an artifact. In consequence, it should be understood as a “produced non-agent resource” for which “unpro- duced non-agent resources” (natural resources) are indispensable (Vallentyne and Steiner, 2000, p.7).

The acquisition of this artifact is also moral, as long as it is not possible, within the presented framework, to coercively prevent the action of the agents invol- ved in the commercial activity at the center of our case study. With the exclusive appropriation of thisright, Kapoor did not even monopolize the possibility of being an artist or creating art. This is because, as we presented earlier, the use of a certain color is a condition of possibility for art, but not of necessity.In consequence, possible objections claiming that Kapoor's action prevents the creation of art are inconsistent in absolute terms 12. In addition, since,in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, arts and crafts became different categories –as the concept of artist/craftsman linked to a guild was abandoned– the principle of competitiveness was more present than ever. As a consequence, the regrets of Furr's wishing to use other resources has obvious ties with envy and the irrational desire to possess what he cannot have 13 . This claim, in fact, acts against the current market paradigm –and, by extension, the art market. This is due to the fact that, in our case, the artist

competes by offering a product which the customers [the collectors] perceive as more valuable than the competi- tors’ products […] offering a product that differs from other products in quality, […] design, […] durability, taste or whate- ver. If buyers recognize the additional value [the artist or the artistic organization] can charge a higher price. (Douma and Schreuder, 1992, p. 129).