DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.16343Published:

2021-05-05Issue:

Vol. 23 No. 1 (2021): January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesDealing with Functional Diversity in EFL Classrooms: English Teachers’ Positioning

El manejo de la diversidad funcional en aulas de EFL: posicionamiento de docentes de inglés

Keywords:

functional diversity, inclusive classrooms, teacher positioning, struggles (en).Keywords:

diversidad funcional, espacios de inclusión, posicionamiento docente, luchas de uno mismo (es).Downloads

References

Adler, J. M., Dunlop, W. L., Fivush, R., Lilgendahl, J. P., Lodi-Smith, J., McAdams, D. P., McLean, K. C., Pasupathi, M., & Syed, M. (2017). Research Methods for Studying Narrative Identity: A Primer. Social Psychological and Personality Science,8(5), 519-527.https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617698202 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617698202

Apitzsch, U & Siouti, I. (2007).Biographical Analysis as Interdisciplinary Research Perspective in the Field of Migration Studies.http://www.york.ac.uk/res/researchintegration/Integrative_Research_Methods/Apitzsch%20Biographical%20Analysis%20April%202007.pdf

Campoy-Cubillo, M. C. (2019). Multidimensional networks for functional diversity in higher education: The case of second language education. Second Language Acquisition-Pedagogies, Practices and Perspectives, 4-21.https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.88073 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.88073

Clandinin, D. J., & Rosiek, J. (2007). Mapping a Landscape of Narrative Inquiry: Borderland Spaces and Tensions. In D. J. Clandinin (Ed.), Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology (pp. 35-75). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226552.n2 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226552.n2

Connelly, F., & Clandinin, D. (1990). Stories of Experience and Narrative Inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19(5), 2-14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019005002 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019005002

Cruz-Arcila, F. (2013). Accounting for Difference and Diversity in Language Teaching and Learning in Colombia. Educación y Educadores,16(1), 80-92.https://doi.org/10.5294/edu.2013.16.1.5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/edu.2013.16.1.5

García, S. B.& Tyler, B. J. (2010). Meeting the needs of English language learners with learning disabilities in the general curriculum. Theory into practice,49(2), 113-120.https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841003626585 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841003626585

Harré, R. (2001). The Discursive Turn in Social Psychology. En D. Schiffrin (Ed.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 688-706). Blackwell Publishers. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470753460.ch36

Hsieh, H. F.& Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Background on the Development of content analysis. Qualitative health research, 15(9), 1277-1288.https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Kayi-Aidar, H. & Miller, E. (2018). Positioning in classroom discourse studies: a state-of-the-art review, Classroom Discourse, 9(2),79-94. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2018.1450275 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2018.1450275

Kayi-Aidar, H. (2019). Positioning Theory in Applied Linguistics: Research Design and Applications. Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97337-1

Liu, D. & Nelson, R. (2017).Diversity in the Classroom. In J. Liontas (Ed.),TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching(pp. 585-590). Wiley-Blackwell. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0224

Lowe, R. J. (2016). Special Educational Needs in English Language Teaching: Towards a Framework for Continuing Professional Development. ELTED, 19, 23-31.http://www.elted.net/uploads/7/3/1/6/7316005/4_vol_19_lowe.pdf

McAdams, D. P. (2001). The Psychology of Life Stories. Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 100–122.https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.100 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.100

Méndez, P. (2017). Sujeto maestro en Colombia, luchas y resistencias. Ediciones Usta.

Méndez, P., Garzón, E. & Noriega-Borja, R. (2019). English teachers’ subjectivities: contesting and resisting must-be discourses. English Language Teaching, 12(3), 65-76.https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v12n3p65 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v12n3p65

Ministerio de Educación Nacional (2003). Decreto 2565 del 24 de octubre de 2003. MEN.https://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1759/w3-article-85960.html?_noredirect=1

Mosquera, Ó., Cárdenas, M., & Nieto, M. (2018). Pedagogical and Research Approaches in Inclusive Education in ELT in Colombia: Perspectives From Some Profile Journal Authors. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(2), 231-246.https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.72992 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.72992

Nina, M. (2018). Working with SEN is tough.https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/blogs/ninamk/special-needs-0

O'Neil, J. M., &Egan, J. (1992). Men’s and women's gender role journeys: A metaphor for healing, transition, and transformation. In B. R. Wainrib (Ed.), Gender issues across the life cycle (pp. 107-123). Springer.

Paneque, O. M., & Barbetta, P. M. (2006). A Study of Teacher Efficacy of Special Education Teachers of English Language Learners with Disabilities, Bilingual Research Journal,30(1),171-193.https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2006.10162871 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2006.10162871

Priestley, M. (2015). Teacher agency: what is it and why does it matter?https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/teacher-agency-what-is-it-and-why-does-it-matter

Romañach, J.& Lobato, M. (2005). Diversidad funcional: Nuevo término para la lucha por la dignidad en la diversidad del ser humano. Comunicación e Discapacidades.http://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/2393402.pdf

Silver, R.C., Holman, E.A., McIntosh, D.N., Poulin, M., & Gil-Rivas, V. (2002). Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. JAMA, 288(10), 1235-1244. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.10.1235 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.10.1235

Smith, A. M., (2018). Raising Awareness of Diversity in the Language Classrooms. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/raising-awareness-diversity-language-classroom

Van Langenhove & Harré, R. (1999). Introducing positioning Theory. In R. Harré & L. van Langenhove (Eds), Positioning theory (pp. 14-31). Blackwell.

Wengraf, T. (2001). Qualitative research interviewing: Biographic narrative and semi-structure methods. Sage Publications. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849209717

Yates, J. R. &Ortiz, A. (1998). Issues of culture and diversity affecting educators with disabilities: a change in demography is reshaping America. In R. J. Anderson, C. E. Keller & J. M. Karp (Eds.). Enhancing Diversity: Educators with Disabilities in the Education Enterprise. Gallaudet University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 19 de mayo de 2020; Aceptado: 26 de abril de 2021

Abstract

Functional Diversity (FD) and inclusion are nowadays widely explored subjects, specifically in the field of English language teaching. This article examines the ways in which EFL teachers problematize their role in functionally diverse scenarios while exposing their efforts to improve the exercise of their profession in FD classrooms. By applying positioning theory (Harré, 2001), we analyzed the narratives of four English language teachers at a high school in Bogotá, Colombia. Data obtained from autobiographical narrative essays revealed three main findings: first, English language teachers positioned themselves as novice or apprentice in FD contexts; second, they struggled with their unpreparedness as they learned to work with FD students; and finally, they positioned themselves as agents of change to overcome difficulties and embrace an inclusive pedagogy. This study contributes to the field by raising awareness of real teaching problems and school situations that EFL teachers face, specifically those related to the struggles of the self (Méndez, 2017).

Keywords

functional diversity, inclusive classrooms, teacher positioning, struggles.Resumen

La Diversidad Funcional (DF) y la inclusión son temas que se están explorando en la actualidad, específicamente, en el campo de la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera (EFL). Este artículo examina la forma en la que los profesores de inglés problematizan su labor docente, mientras revela sus esfuerzos por mejorar el ejercicio de su profesión en los espacios educativos en los que enfrentan la realidad de la diversidad funcional. Este estudio tuvo en cuenta la Teoría de Posicionamiento (Harré, 2001) para analizar narrativas de cuatro profesores de inglés, en el nivel de secundaria, de un colegio privado en Bogotá, Colombia. Los datos obtenidos expusieron tres grandes conclusiones: (1) los docentes de inglés se posicionaron como novatos y aprendices en relación a la Diversidad Funcional; (2) los docentes de inglés lucharon contra su falta de preparación, mientras aprendían a trabajar con estudiantes con Diversidad Funcional; (3) estos docentes se posicionaron como agentes de cambio para superar las dificultades encontradas y poder incluir una pedagogía más inclusiva en sus prácticas diarias. Este estudio contribuye al campo de la Lingüística Aplicada, al crear conciencia sobre los problemas reales de la enseñanza y de las situaciones escolares que enfrentan a diario los profesores de inglés, específicamente, todas aquellas relacionadas con las luchas de uno mismo (Méndez, 2017).

Palabras clave

diversidad funcional, espacios de inclusión, posicionamiento docente, luchas de uno mismo.Introduction

The interest in Functional Diversity (FD) comes from real contexts of work in which English language teachers are challenged to revise and adapt their teaching practices to engage FD students. This topic was first introduced by Romañach & Lobato (2005). These authors wanted to transform the term ‘disability’ into a new concept that could change the inclusive language to refer to people with diverse conditions. In environments where there is no awareness of inclusive programs that can help teachers, directors, and families to deal with functionally diverse children, a number of challenges arise. In such contexts, unpreparedness produces fear, anxiety, and uncertainties in teachers, but also puts their actions to the test.

Nowadays, the implementation of new policies regarding inclusion has been transforming teaching practices in relation to Functional Diversity. However, EFL teachers still struggle to adapt their methodologies to face all new challenges inside the classroom. Actually, English teachers have claimed to know different types of theories that guide educators to understand FD realities. However, these new theories are far away from real and specific contexts where EFL teachers work.

In this study, we pay particular attention to the relationship between teaching and inclusion, which constitutes the epistemological horizon to embrace an inclusive pedagogy in ELT. This relationship recognizes that English language teachers’ meditated actions towards purposely designed activities to engage students (FD or not) in learning were pivotal to increasing teacher knowledge and improving classroom practices in these settings. The ways EFL teachers thought of themselves in autobiographical narratives support not only their ideas about teaching under these circumstances, but also make them reflect upon their own fears and their future alternatives to improve functionally diverse environments.

This study took place in a secondary school with an official inclusion program. There are 32 students with functional diversity. Their needs were described as intellectual, learning, mental, physical, and language-speech. Four English language teachers were invited to problematize their teaching practices regarding FD inclusion. The research question was formulated as follows:

How do EFL teachers position themselves in connection to Functionally Diversity practices in the school?

With this question in mind, the study was oriented towards shedding some light upon the ways English language teachers promoted inclusion in their classrooms, as well as the ways they perceive themselves concerning their duties, English teaching, and rapport with students. The objectives were focused on describing how English teachers see themselves through the construction of their teaching practices with English learners with functional diversity. We also attempt to identify teachers’ beliefs about their practices in regular classrooms and English Language Learners (ELLs)with FD.

This study followed a qualitative-oriented Participatory Narrative inquiry (Connelly & Clandinin, 1990), in which participants were invited to construct their autobiographies to cover their working experience with FD students. The autobiographies allowed us to trace performative and affective dimensions of experience in past, present, and future events where teachers identified critical episodes to think of their professional and personal agendas with inclusive pedagogies.

Theoretical Considerations for ELT Settings

Language Matters: Functional Diversity Instead of Special Needs

The term ‘special needs’ has been widely discussed over the years; even Colombian documents that relate to inclusion define this term as controversial, unstable, and difficult to delineate. In the context where this study took place, it was made evident that some people used pejorative language to refer to FDS; for example, some of the most common words that were used daily were ‘deficient’, ‘disabled, or ‘handicapped’. In the words of Campoy-Cubillo (2019, p. 2): “terms like ‘disability’, meaning ‘less able’, point to the lack of ability of a person and the lack of ability of a student in our class. ‘Functional diversity’, on the other hand, indicates ‘diverse ways of doing things’.”

The concepts above helped us to understand that the participants’ language use was directly related to teaching acts and behaviors as signs of their inexperience in the field. For this reason, we understood the need to apply a new and inclusive term that could refer to this specific population without making a punctual selection, division, or separation between regular students in this academic context.

FD comes to this project with the comprehensive purpose of engaging everyone into our context without generating any kind of distinction or discrimination. Romañach & Lobato (2005) frame the FD community as a traditionally discriminated group that receives a differentiated treatment, as well as other isolated collectives (woman, afrodescendant, and immigrants). In education, it is important to transform traditional views that classify these types of functional diversities as limitations, as restrictive and biologically imperfect (these terms are also semantically pejorative and perpetuate intolerance and exclusion).

FD is a more sensitive term to depict realities of physical, intellectual, and behavioral constituents in functionally diverse people. Indeed, this term must be used as a proposal for social and educational contexts with the purpose of generating better relations between people by reducing boundaries and distinctions. Curricular adaptations and modifications are important to ensuring favorable social and pedagogical conditions to consolidate inclusive pedagogies and a better comprehension of diversity.

Educational Integration vs. Educational Inclusion

Theories on special education have changed their parameters to improve people’s lives. Regardless of the medical dimensions of this collective, social restrictions are continuously being transformed to extend equal opportunities for everybody. Regardless of the validity of bringing people together within a specific community, educational integration is usually limiting and only amounts to the physical presence of FD subjects in a regular classroom. In turn, the proposed type of process aims to unify regular classrooms with functionally diverse students, something that is generally called normalization. Thus, we can conclude that integration seeks the adaptation of FD students into a regular area, whereas inclusion seeks to adjust the general community into the functionally diverse collective.

Functional Diversity in ELT settings

EFL classrooms concerning functional diversity and inclusion are a subject that has not been completely explored in the local English language teaching field. Some works have described that working with special-needs students is tough and adds an extra burden on teachers (Nina, 2019), while some others have suggested the need for ELT professional development to pay attention to the “knowledge of the complex effects of different forms of SEN(Special educational needs) on the language learning experience of students to foster teachers’ ability to maximize the learning potential of the classroom” (Lowe, 2016 p. 24). School teachers who are aware of inclusive practices challenged themselves to adapt their teaching practices to involve and promote learning among their students.

Teaching English to students with diverse functionalities may be a challenging process, considering that children with diverse pathologies (physical, learning, or behavioral) feel also challenged to learn a language at the same level of their peers. According to García & Tyler (2010), FD students need instruction that is simultaneously responsive to their condition, English language status, and culture. Because the majority of students with FD have linguistic ‘disabilities’, classroom teachers in general, and EFL teachers in particular, must be aware of instructional strategies that will support the development of language and literacy in these scenarios. There are indeed some other problems that FD students face every day. For example, FD students may sometimes be unwilling to recognize their struggles, or they prefer not to express them because of cultural or social stigma. In other cases, some students never have access to a diagnostic test which reflected their learning impairments, and they are not able to recognize their own learning difficulties.

In general terms, the interest in diversity has been oriented towards culturally and linguistically value-diverse students. Some theoretical approaches acknowledge that diversity in classrooms can be more complex and varied, hence the need to find best teaching practices to effectively address all of the diversities identified (Liu & Nelson, 2017). In the case of Colombia, the educational needs of functionally diverse students demand the existence of ELT settings with a more inclusive understanding of diversity. In this sense, we agree with Cruz-Arcila (2013) on the need to base our teaching on principles such as particularity, practicality, and the possibility to embrace the local and contextual teaching of English. In this regard, school contexts in which FD is involved are more demanding, which may pose problems for some teachers.

Teachers play an important role in promoting an inclusive classroom, and their actions can “build awareness-raising activities into the language curriculum” (Smith, 2018, p. 2). In fact, teachers can be agents of change when introducing teaching practices actions oriented towards helping FDS to push themselves to enrich their learning process. These teachers can work with existing resources and constraints to achieve lesson and personal goals (Priestley, 2015). In Colombia, an important study, conducted by Mosquera et al. (2018) revealed how some teachers set the relationship between research and pedagogical approaches regarding inclusion or exclusion in ELT and language policies. Findings showed how six inclusive pedagogical practices (tutoring, autonomous learning, taskbased learning, blended learning, collaborative learning, and grammar-translation) were important to promote inclusion with different kinds of diversity.

That study allows us to unveil how English language teachers – even though they have a lack of knowledge about FD – are challenging themselves to learn from their experiences with FDS to react either by implementing actions that involve this population in learning activities with diversity support units (institutional paradigm), or by raising awareness on the need to be prepared to respond better to this reality with the support of family and close classmates (syntagmatic paradigm). It is important to mention that English language teachers who plan their lessons with inclusion purposes promote more learning opportunities for those students in need of more attention. In diverse scenarios, teachers’ positions and fears are being invisibilized or ignored. As Campoy-Cubillo (2019, p.2) says: “teachers involved in teaching students with functional diversity often feel lonely in the process; sometimes one of the paradigms works, while the other does not.” For this reason, the EFL teachers’ positioning towards FD seems to be an important issue to take into consideration. With this in mind, English Language teachers’ views about students’ realities can be a central point to understanding inclusive practices within the classroom.

Positioning Theory to Understand the Teaching in FD Settings

Positioning theory is one of the most important premises in this study. It attempts to describe the way people understand and see the world, and, more specifically, how teachers see themselves in the labor of teaching. In other words, how English language teachers give meaning to teaching and their role in education. Based on Harré’s ideas (1990), positioning theory allows people to locate in the society, due to the identification of its social role in an environment. Harré argues that people define themselves and shape their personhood depending on their life experiences. In doing so, the role of language is a central point, because it works as the leading instrument of thought, self-reflection, cultural identification, and social affiliations. With this in mind, people tend to express their ideas, feelings, wishes, and regrets through the use of language resources such as metaphors, storylines, and concepts that are made relevant within the particular discursive practice in which they are positioned (Harré, 2001).

Positioning theory is useful as an analytical approach to cast light upon the ways English language teachers understand their roles and position themselves as educators to embrace inclusive pedagogies in settings in which FD is present. As it was explained by Clandinin & Rosiek (2007), through narratives, we can gain access not only to individual experiences, but also to the social, cultural, and institutional narratives within which they are constituted, shaped, expressed, and enacted. In this sense, the link between positioning theory and narrative inquiry has served to analyze the narrated experience of subjects (Kayi-Aidar, 2019), as well as the way they cope with particular situations that force them to act or change (Van Langenhove & Harré, 1999). The role of language in positioning theory is important for the construction of social reality, as well as for the construction of identity. In this regard, we were interested in the possible ways in which English language teachers have responded to working with FDS. Teachers’ actions towards inclusion can inform the field of applied linguistics about successful practices in ELT to improve learning and about English Language teachers’ struggles and needs for professional development.

Methodology

This is a qualitative study on narratives of the experiences of English language teachers with functionally diverse students. Following the narrative inquiry approach from Connelly & Clandinin (1990), we intended to reconstruct the participants’ experiences to understand the relationship between EFL teachers’ beliefs about FD and their daily practices inside their classrooms. The aim of this reconstruction focuses on positioning theory as a framework to cast light upon the experience and feelings of participants, and it has found shared patterns rather than individual characteristics.

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted in a secondary school in Bogotá, Colombia. The school followed the current constitutional regulations issued by Ministerio de Educación Nacional (2013), but the institution did not have a concrete curricular adaptation for FD students. There were more than 30 students with diverse functions (they were classified as physical, cognitive, emotional, and social). This group of students was guided by psychological assistance inside the institution, and some of the students required extra attention from external specialists. The school offers different levels of education: preschool, primary, secondary, and high school.

Four English teachers participated in this research by commenting and reporting their experiences with inclusion practices in their teaching experience. This group of participants consisted of two female teachers and two male teachers who have worked at the primary and the secondary levels. In accordance with our ethical considerations, we changed the names of the teachers to different nicknames based on the metaphorical reading of data in accordance with the characteristics of their positioning and personalities. With this in mind, our intention as authors was not to classify or label participants based on our impressions. On the contrary, we attempted to give them a special characterization that could project most of their thoughts and positions. On the other hand, it is important to clarify that the participants agreed to change their identities with their current epithets, and also that all excerpts were translated to English. As the reader may notice along the text, characterizations were mostly based on Disney movies; this encouraged the participants to feel part of this research in a more comfortable environment, thus relieving the tension of exposing their opinions publicly.

Participant 1: “Frida”

Frida is a female teacher whose main interests are teaching literature and language culture. She has been working in the institution for more than two years, and her teaching experience is brief. We decided to name her after a Mexican painter, due to the terms she used to manage to express her opinions about herself and her teaching practices.

“Facing a whiteboard that was me (my own person, my teaching practice) with my hands full of colorful paintings but without knowing how to draw, knowing I wanted to do it but without knowing how it would be” (Narratives, May 2018).

Participant 2: “Pocahontas”

This female participant has been working in the school since 2014.She is an empathetic teacher, and her students always express having a kind affection for her. In her biography, her arguments were strong and direct, like the Disney character Pocahontas, revealing herself as an opponent of the school system and some teachers’ actions.

It is evident to find yourself facing this clash among field colleagues. For them, the easiest thing to do is to put the student aside; they have not given me the orientation, or they have not told me anything about it, and that is why one is in direct conflict with that situation.

Participant 3: “Jafar”

Jafar is a male teacher whose areas of work are focused on grammar and lexicon. He has been working in the school since 2004 and teaches English in middle grades. His students describe him as strict and serious, but also as the smartest teacher in the institution. The nickname Jafar from the Aladdin movie fits well with this personality. He is the oldest participant, and his views on teaching have always been seen as controversial. Furthermore, he always says that his students are the most important part of his life.

I have found hundreds of cases involving boys or girls; I mean students with some limitations. My response to these cases has not been the best in the view of many, but for me as a teacher, as a professional, and as a trainer of people capable of handling languages, this response seems right to me.

Participant 4: “Hercules”

This participant is the youngest male teacher at the institution. He has not completed his bachelor’s degree in ELT yet, but he is close to do so. He sees himself as an inexperienced teacher who is constantly learning from his partners and the academic community in general. He is not afraid of making mistakes, and he is always willing to help his students whenever they need him. These last characteristics allowed us to call him Hercules as the character in the Disney children’s film.

Within all that I have experienced, I have not been able to give a positive report of my work, and, until now, I have not found out the inclusion practices that we boasted about so much in the classroom when we were students.

Data collection procedures

Procedures in autobiographical narratives vary according to the nature of the study and the research agenda. Some studies include free-response qualitative data in written or audio-recorded forms (Silver et al., 2002), whereas other works design exploratory questions or narrative prompts, and others may include semi-structured interviews or a combination of some of these data collection procedures (Adler et al., 2017). At a general level, this type of studies seeks to reconstruct the lived experience and organize the told experience in such a way that each event can be interpreted. In our case, the participants were asked to write about their teaching experiences in connection to their personal biographies. We provided an introduction in which the content of the narrative was specified and, as a complementary source of information, we also implemented formal conversations to guide the written process. The template followed this structure.

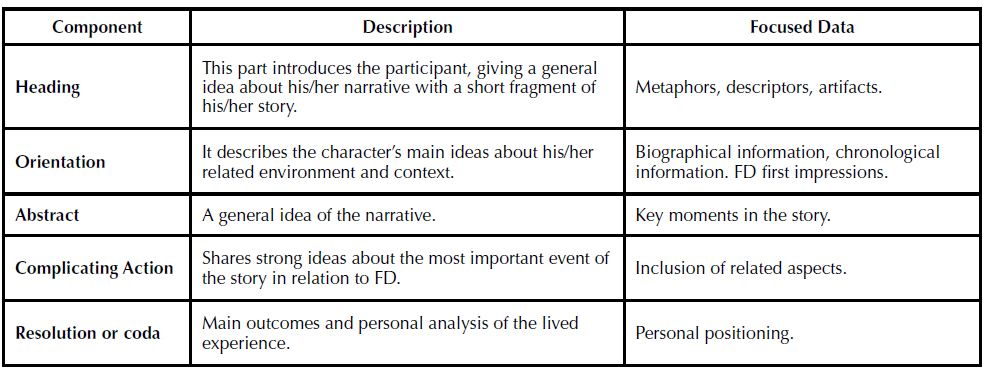

Please describe who you are as a teacher and give some personal information regarding your education and background. Describe your experience coping with functional diversity in your classes (add a heading for it). Then, describe some English language teaching events in which you have been involved regarding functionally diverse practices. Explain these moments in detail (complicating actions). Also, make some comments about how this situation has influenced your teaching practice and your personal view (Coda) on functional diversity (See Table 1 for a general description of these components).

As a result of the first review of the participants’ drafts, we noticed that some narratives were not sufficiently informative. Up to that moment, the participants were guided to reflect upon their narratives by extending the information already provided (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) in formal conversations that were held while they were writing or recording their narratives. It was also necessary to provide some narrative samples to guide participants to complete or complement their narratives based on sequentiality and reflexivity that will be explained below.

Data Analysis

The importance of autobiographical narrative studies lies in their capacity to bring to the surface the meaning that participants give to their actions. This rather exceptional window of opportunity helps us to understand the complexity of teaching from within, as well as the ways participants organize events and give importance to crucial matters to position themselves as facilitators of learning for inclusion.

The analysis of biographical narrative data was inspired by Connelly & Clandinin (1990), Wengraf (2001), and Apitzsch & Siouti (2007), following common general principles such as organization and sequentiality, as well as biographical data analysis and thematic analysis components. In an initial stage, we organized the participants’ narratives following the structure provided in Table 1, an adaptation of Connelly & Clandinin’s model (1990), in which the organization principle helps researchers to work with participants’ narratives to guarantee textual components that structure the orientation of the content. Some samples were provided to help participants observe writing style, organization, and structure.

In the second stage, the sequential principle (coherence, topic-based composition, textual markers, elisions or gaps in the story) was useful to identify formal markers of narration in time and space, as well as content sequential order to understand contextual conditions of production in past and present positioning (Apitzsch & Siouti, 2007). Based on this preliminary analysis, some questions were asked to deepen or clarify aspects of the story that were key to unveiling the participants’ positioning towards FD. Thus, the participants had opportunities to revise, modify, complement, or correct their written narrative versions after conversations in meetings.

In the third stage, we identified information related to the topic of FD with the aid of a thematic analysis component and a biographical data analysis. This analysis stage considers the relevance of topics and the ways in which the participants emphasized, omitted, or hinted at some information. Conversations during the construction of narratives were useful for considering ‘outside data’ as part of biographical narrative components (Wengraf, 2001). A more detailed review of text segments helped researchers pay attention to metaphors, descriptors, artifacts, and content-related information to understand the teachers’ positioning with regards to key moments in the story (see column 3, Table 1.) The four narratives were studied following this analysis component. In doing so, we were able to identify critical or key moments in which participants unveiled their visions of education, as well as the ways they perceive themselves as educators although unfamiliar with the concept of FD, capable of either active or passive actions.

Finally, as a last stage (Wengraf, 2001), researchers contrasted the four narratives (a total of four texts, each varying in length from one to two pages) to cast light upon some correlated aspects concerning FD for further theorization of findings and discussion. A way to proceed, given the narrative nature of the data was to identify the common theme units in each storyline.

Findings

Table 1: Narrative analysis components

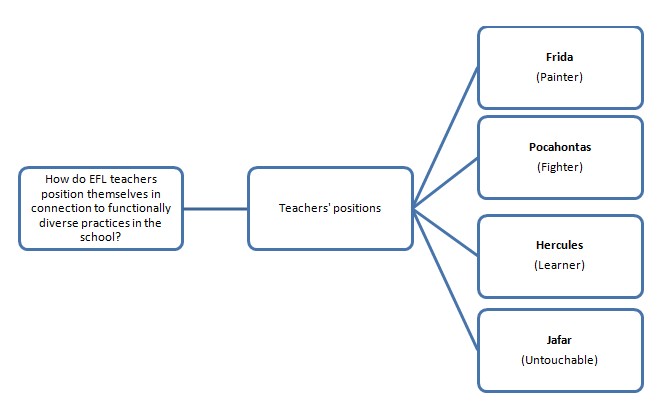

The main research question was related to the way in which English language teachers (ELTs) position themselves regarding functionally diverse students. In consequence, the obtained data were organized by pinpointing beliefs, perceptions, behaviors, or judgments that ELTs made about themselves, FD, or FDS. Three common topics were identified as main categories: (1) novice or apprentice positioning, in which the storyline problematized their teacher education; (2) differential treatment to FDS, in which teachers describe their professional and personal contact with FD; and (3) the role of personal agency for change, the main component to express teachers’ learning, challenges, and frustrations with regards to FD. An important component of data analysis has to do with teachers’ metaphorical identification and positioning, in which nicknames resulted from the interpretation of narratives. In this way, Frida identified herself as the teacher who used painting as a strategy to express ideas; Hercules talked of himself as the novice hero who is in the process of learning; Jafar saw himself as the experienced teacher who has to take the most radical decisions to protect his students from danger; and finally, Pocahontas liked to fight against injustices inside classroom.

Category One: Teachers Positioned Themselves as Novices in Functional Diversity Practices

One of the participants’ biggest concerns was to recognize their shortcomings in the teaching of English to functionally diverse students. Although they were familiarized with some inclusion topics, the teachers argued that they were new in the field of FD. During our conversations about their views on the matter, it was important to pinpoint that FD implies a radical change in the epistemological approach to inclusion. In this sense, making comparisons between the deficit perspective from the past and current FD implications in education allowed them to establish connections between their learning experiences as university students and their current teaching practices. In doing so, absences and gaps about FD in their professional preparation, as well as in their workplaces, were problematized in direct relation with emotions and shocking teaching experiences.

A Deficit in Professional Preparation regarding FD in Undergraduate Programs

The participants felt insecure and novice in the area of functional diversity, which had been concealed for them until they had this experience. Despite the teachers’ differences with respect to their preparation, they all agreed on having misunderstandings such as an unawareness on the topic of special needs, a lack of methodologies to teach functionally diverse children, an ignorance of inclusive policies, etc. All participants exposed their fears about this topic, highlighting them as part of their inabilities to deal with this particular population.

On the other hand, the teachers also problematized the ‘pedagogical practicum’ that they performed during their undergraduate studies as certainly distant from FD realities. They argued that they were involved in different contexts with diverse social conditions, except with this explicit community, so they manifested having experienced some difficulties to identify or deal with several physical, emotional, and behavioral student conditions when these were not visible or extremely notorious.

Again, the question arises: well, why don’t they – teacher educators – teach me this at the university? Why wasn’t I told about these realities – about FD students – that I had to face over time? (Frida’s Narratives, March 2018).

Teachers’ Emotions: Unveiling Struggles of the Self

The example in the previous extract can also be seen as an example of some teachers’ emotions. All the data showed an important amount of feelings emerging from the participants’ experiences about FD students. In the data analysis of the narratives, we found that they were repetitive and constantly mentioned the following emotions: frustration, anxiety, nervousness, and indifference. Those narrated feelings emphasized the verbal or physical expressions of inner struggles in which teachers confront their professional self and their personal dimension to deal with reality (Méndez, 2017).

I get frustrated; I feel like experimenting as if I were a guinea pig myself. (Pocahontas’ narratives, May 2018).

But I always did it in a somewhat aggressive and contemptuous way [...] even many times and I must confess I felt fear.” (Hercules’ narratives, June 2018)

This emotional component turned out to be crucial to embrace inclusion. Some participants admitted that some feelings interfered with their teaching practices; even some of them confessed that it was sometimes easier to put functionally diverse students aside because they did not know how to respond to their needs:

Under these circumstances, I have ignored these situations a little bit, doing what many teachers do, leaving tasks, practical exercises, and workshops according to my own assumptions about those students’ capabilities (FDS). In this way, the rest of the students are free to participate in my class as it must be (Jafar’s narratives, September, 2018).

Despite some positions of negativity and indifference, the teachers were constantly stating their efforts to become aware of this matter. As narratives unveiled, at first, teachers experienced diverse types of emotions, but then, they manifested their intention to try to improve themselves and their teaching strategies to support the FD population. Although facing FD as an unknown field has been a difficult task, the teachers also presented themselves as winners when they achieved some improvements in FD education.

Category Two: Students Needed a Differentiated Treatment

Concerning the treatment given to students, it is worth mentioning an almost permanent division between FD students and their regular classmates. ELTs tended to distinguish between their students when they were asked to talk about them. This scenario encouraged them to think about the social constraints that they were perpetuating inside their classrooms. The most commented aspect has to do with the difference in the pace of learning as a motive for a differentiated treatment:

I have the impression, and I hope I am not mistaken, that when a teacher dedicates himself to teach under these conditions, students who do not have special needs fall behind regarding the pace and nature of the learning process (Jafar’s narratives, May, 2018).

Considering the previous excerpt, this had to be analyzed from two different perspectives: first, what participants understood by ‘educational inclusion’ contrasted with ‘educational integration’; secondly, ELT’s use of language inside and outside the classroom to refer to functionally diverse children.

Therefore, these two elements can be seen as isolated, and, during the observation stage, we could observe that the teachers’ actions were related to their beliefs about diversity and special education. As a consequence, they recognized their pedagogical practice as an integration process in which their actions regarding normalization, their ignorance to assume and create an adapted curriculum for FD students, restricted an advanced type of education for their students with diverse functions, notwithstanding their interest and commitment to improve their realities.

Language Use to Refer FD Students

This section reviews the rising number of words and vocabulary that emerged from the teachers’ positioning in regard to FD students. According to the literature, the implications of teachers’ language use affect students’ learning styles and their development in EFL settings. This component – language use – from an interactional perspective, created the conditions to trace the participants’ language labels, corrections, euphemisms, etc. To this respect, Kayi-Aidar & Miller (2018) considered Harré’s positioning theory as a bridge to create an identity, and, for that reason, language use represents a central aspect in the analysis of narratives as a source of knowledge about ELTs’ views on the subject. Based on the teachers’ narratives, we identified some negative terms that teachers used consciously or unconsciously. We found some words like different, abnormal, disabled, or sick. Even though these types of adjectives are seen as discriminatory, the repetition of these words is thoroughly related to the unfamiliarity of practices with functionally diverse students and special education in mainstream classrooms.

Students with learning difficulties do their activities within an estimated time and planned difficulty, and they deliver the activities. I evaluate them as such, giving a learning concept that I translated into a numerical grade, while normal students do the assignments, workshops and evaluations in accordance with the unit work or the chapter given in the subject (Jafar’s narratives, March, 2018).

Category Three: Actors of Change versus Passive Committed Teachers

Considering positioning as an identity construction, we observed that the teachers positioned themselves into two groups. Surprisingly, in this study, the female teachers (Frida and Pocahontas) showed themselves as actors of change, while the male teachers presented themselves as passive committed workers. In general terms, this fact highlights gender (O’Neil & Egan, 1992) as an important variant in this study, although this aspect was not considered from the beginning. It was clear in the female teachers’ narratives that motherhood and roles involving the upbringing of children transformed these female teachers into comprehensive educators, who acknowledged their students as their sons and daughters. This was recognized in a process of sensitization that female participants argued during their autobiographies.

In a preschool grade there was an inclusion child with autism syndrome, and, because of this, he was aggressive. He did not follow orders and his condition was very marked. It was difficult to handle him since there was the fear that he would suddenly beat us, that he would not let us handle. Thank God, all the teachers and the psychology area, we managed to make the child starts doing things for himself, for instance, having some limits which is something that for someone with his syndrome would be very difficult to achieve. He was an abandoned child, but thanks to many people who decided to help and support him, such as the man who came into his life and adopted him… In this country, medical and financial support is very difficult because many things are needed, such as therapies. I challenge myself to think of him as my son, and the truth is, it is very painful. (Pocahontas’ narratives, April, 2018).

By contrast, male teachers seemed to be uninterested in special management of sensitization practices in the school. These male educators expressed feeling ignorant in this area and rarely felt encouraged to take part in extracurricular actions that could improve their students’ learning processes. For example, Hercules wrote in his narratives:

At first, I thought that she needed a special and different treatment to be able to learn. I stood this ground for a long time; I did not bother much to worry about what she could learn. Furthermore, she demonstrated that she was able to do the schoolwork that I assigned to her (Narratives, May, 2018).

Discussion

The data analysis process showed that the teachers established diverse positions concerning FD education. Moreover, they revealed that their identities as English language teachers suffered a lot due to their powerlessness to deal with these conditions (this was stated in some conversations). The reconstruction of their autobiographical narratives in relation to FD forced them to identify the lack of pedagogical tools to teach English – or any content whatsoever – to functionally diverse students as a flaw in their professional preparation. However, the learning gained through trial-and-error in the description of their pedagogical approach to include functionally diverse students confronted their own visions of teaching while struggling to stay in control of English language teaching contents. When the teachers were asked to describe in a word the way they cope with functional diversity, their particular interests and emotions, they were able to relate themselves with a character and some particular characteristics. This is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Findings regarding positioning.

Some of the main features found in the data are experience, interaction with special education, teaching styles, and personal beliefs. The latter was directly connected with familiar experiences outside the school. All this information was expressed by participants, in a metaphoric position, which allowed them to reflect on themselves in specific scenarios and characters. Fajardo (2006) defines metaphors as a vehicle to interchange truths, beliefs, and opinions. They are a tool to conceptualize the world and its perception. Indeed, repetitive metaphors were found in the data, and most of the teachers used them as a way to emphasize their feelings and emotions during their life experiences. The participants revealed their positions through the use of imaginary scenarios that reinforced the stories they lived. Based on this particular narrative style, we were able to have a real approximation to their identities, and even to their fictitious names. As an example, and due to space constraints in this paper, Frida’s case is described here with the purpose of explaining this metaphorical positioning:

I prepare myself for that reality, that is, the teaching task. It was my turn to go to it and with thousands of spectators: my students, my teacher was a full professor and others. (Frida’s narratives, June, 2018)

This particular example exposed this teacher’s fear when she faced inclusion for the first time in her practicum experience. She presented this anecdote as something mandatory and maybe not so pleasant to remember. She also presented this story as an imaginary scenario that could take place in a bullring; she placed herself going against the bull (her teaching practice), and she also placed the academic community as the spectators, who were surely judging her behavior.

Then, we found another metaphor: the painter and her artwork. In this autobiography, we discovered how important the FD topic was for this participant, not only because of her interest in showing the world her abilities regarding teaching English, but also because of her commitment to work in this unexplored field:

Facing a white curtain that was myself: my own teaching. With my hands full of paint, supplies of thousands of colors, but not knowing how to draw, knowing that I wanted to draw, but not knowing how to do it.

This data excerpt indicated that this participant had a real commitment with her FD students. She wanted to explore her language teaching skills, but her unfamiliarity with inclusion in an educational context made her feel frustrated and unable to do so. This aspect has been explored in Bandura (1986, as cited in Fraser, 2014, p. 4), who defined teacher efficacy as “both a skill and motivation guided by one’s beliefs in their abilities to perform a certain action”, which means that teachers’ perceptions of themselves lead them to discriminate between certain levels of proficiency, and their teaching skills can be reduced or increased depending on their thoughts about themselves.

Consequently, in Frida’s narratives, her position as a painter places her students as the ‘whiteboard’(canvas) upon which she wants to paint. Then, she establishes her commitment, interest, determination, and language knowledge as the colorful paints which she would like to paint with. However, she does not have the ability to paint; this reveals her weakness on inclusion theories and, subsequently, her FD practice in the mainstream classroom.

As it was shown above, distinctions between positioning oneself as novice or apprentice shed light upon the ways in which teachers deal with unpreparedness in a workplace and their deciding to work on themselves to overcome difficulties either by trial and error or by meditated pedagogical actions based on their knowledge and new experiences with FD. Being an apprentice involves a number of practices of observation, study, rehearsal, repetition, and adaptation, in which learning aims to embrace an inclusive pedagogy. In this sense, teachers’ positioning as actors of change deal with will and agency to gain knowledge of FD in order to transform a traditional classroom into an inclusive one. In this study, female teachers were more sensitive and committed to working with FDS, tending to their needs while teaching English for all students, which meant curricula and lesson planning oriented towards working with different learning styles and difficulties. This knowledge gained through experience is meaningful to reinforce teaching practices and can contribute greatly to the professional development of English language teachers.

Conclusions

The narrative construction process allowed the teachers to make real reflections on their own worries, fears, and doubts. This also helped them create spaces for identity construction within the exercise of their profession. It seems as if the ‘autobiographical self’ (McAdams, 2001) performed as a bridge to identify important aspects in FD scenarios. Hence, the autobiographies written by participants emphasized the invisibility of special education in the Colombian context. As an example, we are going to comment on four relevant ideas that this study brought to light:

-

The use of language is directly connected with teaching acts (Harré, 2001). The participants’ positioning revealed their thoughts about FD students. This means that inclusionary practices in the regular classroom were somehow affected by the teachers’ beliefs. Nevertheless, their actions were also influenced by many factors: unfamiliarity in special education matters, inabilities during the identification of FD students and, similarly, their fears about this specific population. Additionally, we identified some anger when their uncertainties were not listened to or attended; they wanted to transform exclusionary practices inside their contexts (Paneque & Barbetta, 2006), but they felt unable to do so. As can be inferred from the excerpts from narratives, the teachers position themselves as educators aware of the school’s reality and the students’ needs (Méndez et al., 2019). Their role as teachers, although present, was not explicitly confronted at the content level.

-

Although this study included just four participants, we cannot deny that gender issues made themselves evident. It seems that female teachers were more sensitive than male teachers in this particular context. For example, Frida and Pocahontas were identified as ‘actors of change’, while male participants showed themselves as ‘passive committed teachers’. This aspect demonstrated that maternal and familiar backgrounds marked a big difference in the teacher-student relationship.

-

The teachers told their life stories through metaphors. In this way, it was easier for them to deal with their own struggles regarding English teaching to FDS. The EFL teachers’ practices involving FD students spawned diverse emotions, whose representations were done by fictitious, imaginary, and also real narratives. Moreover, they used metaphors to manage diverse realities to give strength to their discourses; for example, the participants described particularities from different professions (painters, doctors, and politicians) as part of their daily teaching practice when they faced functionally diverse students. The use of these metaphors facilitated our understanding of their identities and also provided us with a way to differentiate their positioning about special education. Finally, the use of this style of storytelling conducted us to rename our participants with two specific objectives: first, to protect their identities as part of data confidentiality, and second, to characterize the participants as part of their productions.

-

The narratives exposed the teachers’ fears and uncertainty in their educational activities/ teaching work. During the planning stage of this research, we hypothesized that participants would be able to express some difficulties about teaching-specific aspects of language such as syntax, morphology, pragmatics, phonology, etc. Moreover, during data analysis, we discovered that those fears and uncertainties existing in EFL teachers were expressed in more general aspects of teaching that seemed to be more social or emotional, rather than linguistic. Although they felt insecure about how to teach English to FD students, trial and error activities were fundamental to find assertive actions to teach English. This meant the teachers’ worries in educational elements overstepped technical or theoretical issues. Thus, their distresses about FD realities were prevalent in more human scenarios.

In the same way, we could infer that, due to unpreparedness regarding functional diversity, it was impossible for teachers to pay attention to aspects of FD related to their English language syllabi. This feature in the teaching field is not so negative after all; as Campoy-Cubillo (2019) says, working with FD populations in the EFL classroom fosters the development of alternative instrumental and formative competences. Along with their enabling function, these competences promote cognitive, technological, social, and emotional skills in students, rather than purely linguistic ones. On the other hand, in the near future, the acquiring of other abilities outside linguistics could enhance the utilization of skills that FD students can apply in other situations outside the classroom.

To conclude, we want to emphasize the traceable realities that EFL teachers face every day, especially the ones that entail functionally diverse practices. It is important to acknowledge that the positions of ELTs towards students’ realities transpose common teaching routines in language teaching, such as teaching grammar and vocabulary, presenting listening tests and reading tasks, or even the usual preparation of students to achieve better positions in the international scales of language proficiency. Indeed, in this study, we observed that English teachers laid aside linguistic issues to concentrate on the education of human beings.

Although these narratives do not entail aspects of language per se, the participants contributed to demonstrate that the difficulties currently faced by English language teachers – and, most importantly, the expression of those struggles – could increase the regular practices of EFL teaching. The teachers’ positioning reflected not only their fears about unknown aspects of education, but also demonstrated their abilities, illusions, and actions to transform their realities. With this in mind, we consider that this paper could pose a challenge, and be motivational, so that further readers can feel identified and also encouraged to prepare them to accept and discover diverse functionalities inside their classrooms. The understanding of FD as a more encompassing approach to inclusion implies the opportunity to embrace education as an epistemological rupture with the traditional treatment of disability as an impossible limit. In other words, we cautioned English language teachers to not use FD as a euphemism to pretend they are involved with functionally diverse activities. We expected the teachers not to feel afraid of expressing their doubts about inclusion and to take this topic seriously in order to contribute to a better teaching practice for all.

Finally, for further research, it would be important to take into account that functionally diverse students are still labeled as a minority group that needs an adapted curriculum in all academic subjects. Henceforth, directive and political instances must adapt a singular program in order to guarantee the effectiveness and success of both FD students and regular students as equals. Therefore, the curricular accommodations should allow FD students equal access to opportunities in terms of education, so that they can achieve high results according to their abilities and interests. The aforementioned adaptations must be carefully designed and followed. For this reason, institutions and the educative community have to be prepared to modify regular teaching programs, classes, working times, learning spaces (classrooms, offices, fields, etc.), and technological support (Campoy-Cubillo, 2019). Furthermore, EFL teachers need to receive constant support and regular training in the field of special needs. This involves a continuous strengthening of theory and practice, not only during bachelor programs, but also during the daily pedagogical endeavor. Finally, as functional diversity is a constantly changing area, Colombian policies must ensure that integration policies are implemented in a sustained and appropriate manner.

References

Metrics

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Laura Camila Villarreal Buitrago, Pilar Méndez Rivera

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.