DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.81Published:

2010-07-01Issue:

Vol 12, No 2 (2010) July-DecemberSection:

Research ArticlesThe Use of Complaints in the Inter-Language of Turkish EFL Learners

El uso de los reclamos en el inter-lenguaje de estudiantes de Inglés como lengua extranjera en Turquía

Keywords:

actos de habla, quejas, interlenguaje, transferencia pragmática (es).Keywords:

speech acts, complaint, inter-language, pragmatic transfer (en).Downloads

References

Barron, Anne (2005). Variational pragmatics in the foreign language classroom. System, 33(3), 519536.

Bergman, M. L. & Kasper, G. (1993). Perception and performance in native and nonnative apology, In G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka (Eds.), Interlanguage Pragmatics, 82-107, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bonikowska, M. (1988). The choice of opting out. Applied Linguistics, 9 (2), 169-181.

Boxer, D. (1993). Complaints as positive strategies: what the learner needs to know. TESOL Quarterly, 27(2), 277-299.

Boxer, D. & Pickering, L. (1995). Problems in the presentation of speech acts in ELT materials: the case of complaint. ELT Journal, 49(1), 44-58.

Brown, P. & Levinson, S. C. (1978). Politeness: Some Universals in Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ercetin, N. G. (1995). Pragmatic Transfer in the Realization of Apologies: The case of Turkish EFL Learners. Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Boaziçi University, stanbul, Turkey.

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J.

Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics, 269- 293, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Kasper, G. (1992). Pragmatic transfer. Second Language Research, 8:3, 203-231.

McKay, S.L. & Hornberger, N. H. (1996). Sociolinguistics and Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Márquez-Reiter and Placencia (2005). Spanish Pragmatics, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Murphy, B. &. Neu, J. (1996). My grade's too low: the speech act set of complaining. In S. M. Gass & J. Neu (Eds.), Speech Acts Across Cultures: Challenges to Communication in Second Language, 191-216, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Olshtain, E. & Weinbach, L. (1993). Interlanguage features of the speech act of complaining. In G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka (Eds.), Interlanguage Pragmatics, 108-122, New York, Oxford : Oxford University Press.

Searle, J. R.(1990). Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zegarac, V. & Pennington, C. (2000). Pragmatic transfer in intercultural communication, In H. S. Oatey (Ed.), Interculturally Speaking, 165-190, London: Continuum.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2010 vol:12 nro:2 pág:25-42

Research Articles

The Use of Complaints in the Inter-Language of Turkish EFL Learners

El uso de los reclamos en el Inter lenguaje de estudiantes de Inglés como lengua extranjera en Turquía

Tanju Deveci [1]

[1] Instructor, The School of Languages Sabanci University, Istanbul, Turkey E-mail: tanju@sabanciuniv.edu

Abstract

Many Turkish EFL learners struggle with giving complaints and criticisms in the EFL classroom. Language instructors must find way to provide students with the linguistic and pragmatic elements of EFL to be able to appropriately complain as EFL users. The purpose of this study is to investigate the complaint speech used by Turkish EFL learners in two different situations: speaking to a commiserating teacher and speaking to a contradicting teacher. Four kinds of data sources were used to collect data in the classroom: twenty native English speakers’ role-plays, twenty-five Turkish native speakers’ role-plays, and forty students’ role-plays. The subjects’ complaint speech act sets were a coding scheme borrowed from a previously conducted study by Murphy and Neu (1996). The baseline and the inter-language data were compared to see to what extent they were similar or different, whether or not the Turkish EFL learners made positive and negative transfer, and if there were any features unique to the inter-language of the learners. The findings revealed that when speaking to the commiserating teacher, students made both positive and negative transfer in using ‘demand’. The students speaking to the contradicting teacher made positive transfer in the components ‘explanation of purpose’, ‘complaint’ and ‘justification’. The component ‘demand’ was subject to negative transfer.

Key words: speech acts, complaint, inter-language, pragmatic transfer

Resumen

Muchos estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera tienen dificultades para dar quejas y hacer críticas en el salón de inglés como lengua extranjera. Esta situación exige que los profesores de idiomas piensen en las maneras de brindar a los estudiantes los elementos lingüísticos y pragmáticos de la lengua extranjera, para que sean capaces de reclamar apropiadamente en este idioma. El propósito de este estudio es investigar el discurso utilizado por los estudiantes turcos de inglés lengua extranjera para quejarse, en dos situaciones diferentes: la primera, al hablar con un profesor simpático y la otra, al hablar con un profesor contradictorio. Para la recolección de datos en el aula, se utilizaron cuatro tipos de fuentes: representaciones de veinte nativos de inglés, representaciones de veinticinco turcos y representaciones de cuarenta estudiantes. Los sujetos fueron expuestos a dos situaciones diferentes. El conjunto de sujetos que se quejan en su discurso fueron analizados, usando un esquema de codificación tomada de un estudio previamente realizado por Murphy y Neu (1996). La base de referencia y los datos de interlenguaje fueron comparados, para ver hasta qué punto eran similares o diferentes, sin importar, si los estudiantes turcos de lengua extranjera hicieron transferencia positiva o negativa, ó si había algunas características únicas en el interlenguaje de los estudiantes. Los resultados revelaron que cuando hablan con el profesor simpático, los estudiantes hicieron transferencias tanto positivas como negativas en la “demanda”. Los estudiantes que hablaron con el profesor contradictorio hicieron transferencias positivas en los componentes del “propósito de explicación”, “queja” y “justificación”. El componente de la “queja” fue sujeto a transferencia negativa.

Palabras clave: actos de habla, quejas, interlenguaje, transferencia pragmática

Introduction

“The students don’t know how to speak to a teacher!” complain many English teachers in the Turkish context. This phrase signifies that teachers feel that their students do not pay attention to the sociolinguistic aspects of English and end up complaining to their teachers in a manner that could be seen as culturally insensitive by the teachers, causing classroom strife. Students lack opportunities to be involved in authentic situations in which complaints are made resulting in inadequate strategies for complaining, an idea supported by Boxer and Pickering (1995). Turkish learners of English might not be aware of the cross-cultural differences of this speech act between native speakers of the two languages. In addition, the currently used textbooks lack emphasis on how to appropriately complain in English, which has also been found to be the case in research done by Boxer and Pickering of presentation of speech acts (1995).

The speech act of ‘complaining’ has garnered relatively little interest from researchers compared to the interest shown in the other speech acts such as ‘apologizing’, ‘thanking’, and ‘refusing’. Nevertheless, there have been a few studies (e.g. Murphy & Neu, 1996, Boxer, 1993; Olshtain & Weinbach, 1993) carried out on the act of complaining. However, the speech act of complaint has not been studied taking into consideration the interlocutor’s attitude towards the complainer, a gap in the research that has been partially filled by the following study. Through studying the effect of the interlocutor’s attitude, either as a commiserating party or as a contradicting one, teachers can be more fully informed of certain intercultural differences between native Turkish students and themselves, furthering their ability to provide comfortable classrooms in which students can freely express themselves. In addition, teachers can find ways through intercultural understanding to explain to Turkish students what methods of complaining are considered appropriate in an Englishspeaking environment.

It is a fact that learners may make both negative and positive transfers from their mother tongue to the language they are learning. With this in mind, we find it important to find out how and in what circumstances the Turkish speech act of complaint is carried out, hopefully illuminating why Turkish learners seem to have problems with expressing themselves and what they want when speaking to native speakers of English.

Theoretical Considerations

The well-known concept of ‘communicative competence’ has been a favorite topic for analysis both in first language and second language learning since Dell Hymes (1972) asserted that speakers of a language need to have more than grammatical competence to be able to communicate effectively. Hymes added that speakers of a language need to know how the language is used by members of a speech community to accomplish their purposes. Language users need to have the ability to function in both linguistically and socially appropriate ways.

Searle (1990, p. 16) claimed that speaking a language is performing speech acts. By performing a speech act, people produce certain actions such as thanking, requesting, and complaining. Speech acts are important elements of communicative competence, and speakers of a language need to know how to carry out speech acts to function in communicatively appropriate ways.

The significance of speech acts has generated interest in certain aspects of variously defined speech acts. This study is concerned with one of the aspects of communicative competence: the performance of the speech act of complaints in the inter-language of Turkish learners of English.

The Research Questions

The research questions of this study are:

- Given the context of expressing disapproval to a teacher who is commiserating1 with them, which components of the complaint speech act set will Turkish non-native speakers of English produce in their inter-language? What are the topics of these sets?

- Given the context of expressing disapproval to a teacher who is contradicting them, which components of the complaint speech act set will Turkish non-native speakers of English produce in their inter-language? What are the topics of these sets?

- Do Turkish non-native speakers of English make pragmatic transfer in their use of the complaint speech act set when expressing disapproval to a teacher who is commiserating with them?

- Do Turkish non-native speakers of English make pragmatic transfer in their use of the complaint speech act set when expressing disapproval to a teacher who is contradicting them?

Pragmatic Transfer

Pragmatic transfer can be described as “the transfer of pragmatic knowledge in situations of intercultural communications” (Zegarac & Pennington, 2000, p. 167).

Kasper (1992: 223) claims that when identifying pragmatic transfer, looking at only the percentages by which a particular category occurs in the mother tongue (L1), the target language (L2), and inter-language (IL) data is not enough. These figures do tell us something meaningful about pragmatic transfer, but caution us to employ procedures which allow us to make claims with reasonable confidence. Kasper states that an adequate method for identifying pragmatic competence is to determine whether the differences between the interlanguage and the learner’s native language on a particular pragmatic feature are statistically significant and how these differences relate to the target language. The author explains that lack of statistically significant differences in the frequencies of a pragmatic feature in L1, L2 and IL can be operationally defined as positive transfer. On the other hand, statistically significant differences in the frequencies of a pragmatic feature between IL-L2 and L1-L2 and lack of statistically significant differences between IL and L1 can be defined as negative transfer (1992).

Cross-cultural analysis of speech acts can be seen as valuable in explaining pragmatic transfer, which is also suggested by Barron (2005) who says that speakers of different languages are likely to make different choices when producing speech act strategies. These differences may be seen in linguistic forms used to carry out an individual speech act strategy. Barron (2005) suggests that regional and social factors on linguistic interactions need to be given more attention since conflicts between parties may be reduced with an awareness of such differences.

The Speech Act of Complaint

Olshtain and Weinbach (1993, p. 108) asserted “in the speech act of complaining, the speaker (S) expresses displeasure or annoyance censure as a reaction to a past or going action, the consequences of which are perceived by S as affecting her unfavorably.”

Some of the functions of complaints can be listed as follows:

- to express displeasure, disapproval, annoyance, threats, or reprimand as a reaction to a perceived offense (Olshtain & Weinbach,1993),

- to confront a problem with an intention to improve

- to allow ourselves to let off steam (Boxer, 1993).

Not everyone may decide to perform the speech act of complaint because of its potential undesired social consequences. Marquez-Reiter and Placencia (2005, p. 155) state that the speech act of complaint is inherently face-threatening since it threatens the face of the speaker and the hearer. Therefore, one might choose to opt out. Such a decision, as a result, is a social one before it is a linguistic one.

Encoding of Complaints

Murphy and Neu (1996: 199-203) identified the strategies used by Americans, and encoded them into categories accordingly:

- Explanation of Purpose / Warning for the Forthcoming Complaint I just came by to see if I could talk about my paper.

- Complaint I think maybe the grade was a little too low.

- Justification I put a lot of time and effort in this…

- Candidate solution: request I would appreciate it if you would reconsider my grade.

Responses to Complaints

Boxer (1993: 286-287) identified six types of indirect complaint responses among native speakers of American English:

(1) Joke/teasing:

A: How ya doing B?

B: Oh, not so great. I can’t find S. Maybe she told me she was doing something this morning and I don’t remember.

A: You are getting old!

(2) Nosubstantive Reply:

A: They keep tearing down those historical buildings. If one supermarket went up in that location, who’s to say … maybe if it were something else altogether, but when they replace it with the same thing …

B: Hmn (nods head repeatedly).

A: So you have the summer off?

Question:

A: I was up all night with C.

B: What’s wrong?

A: She’s had this hacking cough, it’s gotten worse. So I’m gonna take her to the doctor.

B: You know, M is home sick today too.

A: Why?

B: I’m not sure, she’s still sleeping. She’s either exhausted or caught a chill.

(4) Advice/lecture:

A: This vacuum doesn’t pick up the little pieces.

B: You probably have to put more pressure on it.

(5) Contradiction:

A: This doesn’t follow your basic economic theories.

B: It has to!

(6) Commiseration:

A: My husband is in Greece, so I’m packing myself. Most of it is books and manuscripts.

B: Oh, that’s the worst.

From the data gathered, Boxer suggested that

the manner in which the addressee responds to an indirect complaint can significantly promote further interaction. That is to say, depending on the type of response elicited, the complaint sequence can affirm or reaffirm solidarity among the interlocutors or alienate them from each other. The implication . . . is that if one wishes to accomplish the former that is, establish some commonality with the speaker the addressee will need to know how to respond to indirect complaints when they are used as conversational openers and supporters. (1993: 286)

Methodology

Subjects

Learners of English (IL Speakers)

Twenty native Turkish speakers learning English participated in the study as respondents to one commiserating and one contradicting teacher. The mean age of the students was 18.

Native Speakers of English (ENSs)

In order to find out how native speakers of English realize the speech act of complaint, 20 native speakers of English participated in the study. Half of these speakers, whose ages ranged from 30 to 49 with mean age 37, spoke to a commiserating teacher while the other half, whose ages ranged from 30 to 55 with mean age 39.5, spoke to a teacher who was contradicting them.

Native Speakers of Turkish (TNSs)

Twenty-five native speakers of Turkish participated in the study as respondents to a commiserating and a contradicting teacher. Thirteen of the respondents, the mean age of whom was 20, spoke to the commiserating teacher. The other 12 respondents, also with a mean age of 20, spoke to the contradicting teacher.

English Interlocutors

Two interlocutors who were native speakers of English spoke to both native speakers of English and the Turkish students. One of the interlocutors adopted the role of the commiserating teacher while the other adopted the role of the contradicting teacher.

Turkish Interlocutors

Two Turkish interlocutors talked to the Turkish subjects to provide the Turkish baseline data. One of them adopted the role of the commiserating teacher, while the other adopted the role of the contradicting teacher.

Instruments

The speech act data were collected via two sets of role-play tasks, one of which was in English and the other one was in Turkish (see Appendix 1 and 2).

In one of the tasks, the interlocutor adopted the role of a teacher who was commiserating. In the other task, the interlocutor adopted the role of a contradicting teacher. Such a role-play, in which parties can interact with each other and can alter what they want to say or the way they want to say it according to the attitude of the interlocutor and the emerging features of the dialogue, is believed to reflect the way people interact in everyday discourse.

Some sample sentences that a commiserating and a contradicting teacher could utter were written on the role-play cards for the interlocutors to refer to.

In order to make sure that the role play tasks in Turkish and English correspond to each other, two teachers of English were asked to translate the role-plays back to English and Turkish, and after comparing the different versions, necessary changes were made.

Analysis Procedures

The roles of the interlocutors were based on Boxer’s (1993) findings about the responses to indirect complaints. The commiserating teachers were instructed to ask encouraging questions to the student complaining. The contradicting teachers were instructed to ask challenging questions and not to provide substantive replies.

After the interlocutors had been assigned their roles, the students were asked to put themselves in the shoes of the person in the hypothetical situations in the role-play task. They were given time to think over what they would say to the teacher. Then, they were admitted into the room in which the role-play was to take place. Their responses were audio-recorded, and the respondents were informed about this.

After all the recordings had been done, the dialogues were transcribed by the researcher himself. The encoding was done according to Murphy and Neu’s (1996) complaint strategy categories for complaints:

- Explanation of Purpose

- Complaint/criticism

- Justification

- Candidate solution: request/demand

The transcriptions of the role-play in which the interlocutor was commiserating, and the roleplay in which the interlocutor was contradicting were analysed separately in order to identify the components of the responses of native speakers of English, and the Turkish subjects’ responses in English and Turkish.

Transcription conventions were used only for the interlanguage data since it was the main focus of the study. The conventions drawn up by the CHILDES were used in transcribing the interlanguage data.

Statistical Analyses

The components of both American and Turkish complaints made to the commiserating interlocutor and contradicting interlocutors were drawn up separately and compared. In order to determine whether or not there were statistically significant differences between the data sets, a paired sample t-test was conducted. T-test was chosen for the statistical analyses owing to the fact that the number of the subjects were lower than 30.

The same procedure was followed with the interlanguage data, which was compared to the baseline data in order to identify any pragmatic transfer made by the Turkish EFL learners.

Results and Discussion

Data from TNSs in the Presence of the Commiserating Teacher

The analysis of the Turkish data yielded a complaint speech act set which includes the components ‘justification’, ‘candidate solution: request and/or demand’, ‘complaint’, and ‘explanation of purpose’. Unlike what Murphy and Neu (1996) found in the native English data set, the analysis of our data revealed that a certain number of speakers produced ‘criticism’ along with ‘complaint’, a separate speech act. Also, the type of candidate solution seemed to differ in that Turkish speakers came up with both a request and a demand. One of the sentences uttered by the students to request a solution is:

1. Acaba yani bir daha gözden geçirebilme imkaniniz olur mu?

‘I wonder if you could have the chance to go over it again’

An example of a demand produced by Turkish speakers, on the other hand, is:

2. Niye böyle bir not aldigimi ögrenmek istiyorum. ‘I want to learn why I got such a mark’

Data from TNSs in the Presence of the Contradicting Teacher

The TNSs produced a complaint speech act set when speaking to a contradicting teacher including the components ‘explanation of purpose’, ‘justification’, complaint’, ‘candidate solution: request and/or demand’, and ‘criticism’. These components differed from the data produced by those speaking to a commiserating teacher in their use of ‘explanation of purpose’ and ‘candidate solution: request’.

The paired sample t-test conducted to determine if there was a significant difference between the components of the speech act sets produced by TNSs speaking to a commiserating teacher and a contradicting teacher revealed statistically significant similarities as well as some differences.

The components of the speech act of complaint in the two data sets seem to parallel each other in terms of ‘complaint’, ‘criticism’, ‘justification’, and ‘candidate solution: request’. However, in terms of providing ‘an explanation of purpose’ and ‘request as a candidate solution’ there is statistical difference in the two sets. This suggests that the TNSs were more likely to explain the reason for their presence in the office of a non-commiserating teacher, and tend to request a solution for an undeserved mark when they speak to a commiserating teacher.

Data from ENSs in the Presence of the Commiserating Teacher

The ENSs speaking to a commiserating teacher data produced a complaint speech act set including the components ‘explanation of purpose’, ‘complaint’, ‘justification’, ‘candidate solution’, and ‘criticism’. An example of criticism produced is:

1. I think you should not you know grade me very low just because of that.

The most striking point about the ENSs’ utterances is that they all employed the components ‘complaint’, ‘justification’, and ‘candidate solution: request’.

Data from ENSs in the Presence of the Contradicting Teacher

The speech act set produced by the ENSs included the components ‘explanation of purpose’, ‘complaint’, ‘candidate solution: request’, ‘justification’, and ‘criticism’.

The most noteworthy result was the frequency of ‘explanation of purpose’, ‘complaint’, ‘candidate solution: request’, which were realized by all the respondents, and ‘justification’, which was realized by 90% of the ENSs.

The two English data sets were compared using the paired sample t-test to reveal any similarities or differences. The most prominent point is that the frequency of use of the components in the two separate sets is mostly the same.

The components that are strikingly similar are ‘complaint’, ‘candidate solution: request’, and ‘criticism’.

Another area where the ENSs paralleled each other in the two sets was the frequent occurrence of justification. Each of the ENSs speaking to a commiserating teacher provided a justification, and 90% of the ENSs speaking to a contradicting teacher provided a justification. (t = 1.025 < 2,101, p = 1 > 0.05).

The explanation of purpose was also produced with a high frequency. Ninety percent of those speaking to a commiserating teacher produced an explanation of purpose. Similarly, all of the ENSs who spoke to the contradicting teacher provided an explanation of purpose, and there were no statistically significant differences between them. (Z=-1,025 > -2,101, p = 1 > 0.05).

The comparison of the data gathered from the TNSs and the ENSs speaking to a commiserating teacher revealed both similarities and differences in the use of the complaint speech act set.

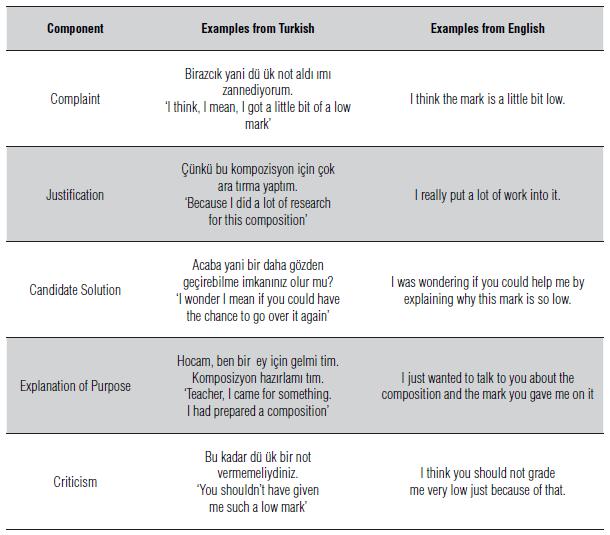

The most notable similarity was the use of similar components. Both groups made use of ‘purpose’, ‘complaint’, ‘justification’, ‘candidate solution’, and ‘criticism’ despite the differences in the frequency. Examples for each component can be seen Table 1 below.

Speaking to a Commiserating Teacher

Another noteworthy similarity is the use of the component ‘explanation of purpose’. Even though there was a difference between the frequencies of emergence of the component in the two languages, there was no statistically significant difference between the Turkish native speakers and the native speakers of English. (t = -1.87 > -2.080, p= 0.089>0.05).

Yet another similarity was ‘the speech act of complaint’. Seventy-six point five two percent (76.52%) of the TNSs and all of the ENSs employed a complaint . (t = -1.63 > -2.080, p= 0.229 > 0.05).

The use of ‘the candidate solution: request’ was another obvious similarity. The majority of the TNSs (76.92%), employed request as candidate solution, and all of the ENSs made use of the component of request in their complaint strategy set. (p = 0.486 > 0.05).

Similarly ‘justification’, which occurred in 92.31% of the TNSs’ responses, occurred in all the responses of the native English speakers. (t = - 0.897 < -2.080, p=1 > 0.05).

The last significant similarity between the two sets was ‘the speech act of criticism’. While 23.08% of the TNSs produced a criticism, 20% of the ENSs realized the act of ‘criticism’. (t = 0.18 < 2.080, p=1> 0.05).

The most striking difference was the realization of ‘the speech act of demand’ as a candidate solution, which occurred only in the utterances of TNSs (23.08%).

The comparison of the data gathered from the groups revealed both similarities and differences in the use of the complaint speech act set in presence of a contradicting teacher. The most striking similarity between the two speech act sets in the two languages was ‘the explanation of purpose’. All respondents provided an explanation of purpose.

Another obvious similarity occurred regarding ‘justification’, which was provided by all the TNSs and 90% of the ENSs. The statistical analysis also showed that there was a similarity between the Turkish and the English data. (t = 1.12 < 2.086, p = 0.455 > 0.05).

The occurrence of the speech act of ‘criticism’ was a further noteworthy similarity. Criticism was present in 41.67% of the responses of the TNSs while 20% of the ENSs provided criticism. (t = 0.84 < 2.086, p = 0.381 > 0.05).

Despite the similarities listed above, there were also differences in the use of ‘candidate solution: demand’, ‘candidate solution: request’, ‘complaint’, and ‘justification’.

The most striking differences were in terms of the candidate solution. The first difference was the occurrence of the component ‘demand’ as the candidate solution only in the Turkish data (33.33%). The second difference was the component of ‘request’ as the candidate solution. While 41.67% of the TNSs produced a request, all of the ENSs provided a request as a solution to the perceived problem. The statistical analysis revealed a significant difference between the component ‘request’ in the two data sets. (t = -2.92 > -2.080, p = 0.005 < 0.05).

The third noteworthy difference was the component set of the complaint between the Turkish data and English data. Fifty eight point thirty-three percent of the TNSs produced a complaint. On the other hand, complaint was present in the responses of all ENSs producing a statistically significant difference. (t = -2.32 > -2.086, p = 0.04 < 0.05)

Analysis of the Inter-language Data

Inter-language Data Collected through a Role-Play with a Commiserating Teacher

The answer to the first research question for this study seems to be positive. However, the type of candidate solution produced by EFL learners seemed to vary in that they produced not only ‘candidate solution: request’ but also ‘demand’.

The most frequently used component in the set was the speech act of ‘complaint’, which was provided by each EFL learner. The topic of their complaint concerned the grade of the paper as shown in (1).

1. I think I didn’t deserve my last mark from composition.

The second most frequently used component was justification (95%). The topic of their justifications was the time spent studying, research done on the topic, the attempt to use a variety of structures and vocabulary items, as shown in sample (2).

2. I believe I work a lot. I do many research.

A ‘candidate solution: request’ was another frequently used component (90%). Their requests involved asking the teacher to reread the paper or provide help to make it better and asking for another chance to rewrite the essay. Representative examples are shown in sample (3).

3. We can think about it, we can read it again, and we can put another decision

'Explanation of purpose was provided' by 17 students, and it was the fourth most frequently used component. In doing so, they explained the reason for their visit to the teacher. Common examples from the non-native speakers’ responses include sample (4).

4. I want to talk about the mark that you have given to me after composition.

Demand was the least frequently used component (20%). Two of these students also made use of a request as a solution as well as a demand as in sample (5).

5. I want you to read my composition by thinking about the time I spent.

Inter-language Data Collected through a Role- Play with a Contradicting Teacher

The answer to the second research question is answered affirmatively.

The speech act set produced by the Turkish non-native speakers speaking to a contradicting teacher contained the components in Murphy and Neu’s (1996) complaint speech act set. However, the component ‘candidate solution’ differed in that the Turkish EFL learners produced both the components ‘request’ and ‘demand’.

The most frequently used component was justification (95%). The topic of their justifications were time spent studying, sleepless nights and the accurate use of grammar and vocabulary, as shown in samples (6).

6. I worked a lot on this composition.

‘Explanation of purpose’ and the speech act of ‘complaint’ were the second most frequently used components in the inter-language set (80%). Common examples from the non-native speakers’ responses include samples (7).

7. I want to speak about my composition.

Complaint was produced by 80% of the speakers. In general, the topic of their complaint concerned the grade of the paper as shown in sample (8).

8. I think this grade is not good enough for me.

The component ‘candidate solution: request’ was produced relatively less frequently (45%). The students asked the teacher to reread the paper, let the student rewrite the essay, and reread the paper together, as shown in (9).

9. Can I write this again and get a high mark?

The least frequently used component in the set was the speech act of ‘demand’. It was produced by five students. By issuing a demand, these students asked the teacher to reread the paper and go over the paper together, as shown in (10).

10. I just want some explanation together.

In order to identify whether or not the Turkish EFL learners employed similar features in their complaint speech act set, the data collected from these students speaking to a commiserating and contradicting teacher was compared using statistical methods.

The comparison of the data revealed both similarities and differences in the use of the complaint speech act set. The t-test was done to determine if the differences were statistically significant. The relationship between the components was tested with 95% confidence.

The most striking similarity between the inter-language data sets was the realization of the component ‘justification’, which was produced with the same frequency in both groups.

The second notable resemblance was in the use of component ‘explanation of purpose’. The component in each set was produced with a high frequency. (t = 0.42 < 2.021, p = 1 > 0.05).

The third noteworthy similarity was the occurrence of ‘the candidate solution: demand’, which occurred with a low frequency in both data sets. (t= - 0,.38 > -2.021, p = 1 > 0.05).

Despite the similarities discussed above, there were some differences. The most obvious difference was the use of the component ‘request’ as a candidate solution to the perceived problem. While those who spoke to the commiserating teacher requested a solution with a high frequency (90%), the ones who spoke to the contradicting teacher made use of it less frequently (45%). (t = 3.04 > 2.021, p = 0.006 > 0.05).

The second striking difference was about the use of the complaint speech act, which was produced by all (100%) the students speaking to the commiserating teacher. However, 80% of those speaking to the contradicting teacher made use of this speech act. (t =2.11>2.021).

Pragmatic Transfer Made by the Turkish EFL Learners

Pragmatic Transfer Made By the Turkish EFL Learners Speaking to the Commiserating Teacher

Positive Transfer

The first area where positive transfer was detected was ‘explanation of purpose’. There was no statistically significant difference between the Turkish and English baseline data. Similarly, no statistically significant difference between the inter-language and English was found. (p = 1 > 0.05). In just the same way, the Turkish data and inter-language data did not reveal any significant difference (p = 0.107 > 0.05), which suggests that the students’ L1 positively affected their use of explanation of purpose in their inter-language, and helped to develop the target language.

The second positive transfer was noted regarding ‘complaint’. The Turkish and English baseline data did not have significant differences.

The third area where positive transfer emerged was ‘justification’. (t = - 0.897 > - 2.080, p=1 > 0.05). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference between the English baseline data and the inter-language data. (t = 0.72 < 2.048, p = 1 > 0.05). No statistically significant difference was detected between the Turkish baseline data and the inter-language, either. (p = 1 > 0.05).

The final positive transfer was noted in the use of ‘candidate solution: request’. Both native speakers of English and Turkish produced a request as the candidate solution and there was no statistically significant difference between them (p = 0.486 > 0.05).

Negative Transfer

The only negative transfer occurred in the production of ‘candidate solution: demand’. While there was no statistically significant difference between the Turkish baseline data and the interlanguage data (t = 0.21 < 2.042, p = 1 > 0.05), native speakers of English did not make use of demand at all.

Another noteworthy result was that both the TNSs and the ENSs produced ‘criticism’ while the EFL learners avoided producing criticism.

Pragmatic Transfer Made By the Turkish EFL Learners Speaking to the Contradicting Teacher

Positive Transfer

Both Turkish and English native speakers employed ‘explanation of purpose’, and there was no statistically significant difference between the two native languages. In the same way, the difference between the inter-language data and English data was not significant. The same was true for the inter-language and Turkish. (t = 1.66 < 2.042, p = 0.625 > 0.05).

The second area where positive transfer occurred is ‘complaint’, which was present in all three data sets. Fifty-eight point three three percent (58.33%) of the TNSs produced a complaint, and 80% of the EFL students produced a complaint. All the ENSs produced a complaint, and there was no statistically significant difference between the inter-language and the English data. (t = 1.52 < 2.048, p = 0.272 > 0.05).

The third noteworthy transfer was made in terms of ‘justification’. All the TNSs produced this component in their speech act set. Quite similarly 90% of the ENSs produced justification. (p = 0.381> 0.05). Also, there was no statistically significant difference between the Turkish baseline data and the inter-language. (p = 1 > 0.05). As a corollary to this, there was no statistically significant difference between the inter-language and the English data. (t = -0.52 > -2.042, p = 1 > 0.05). Therefore, it can be suggested that the production of the component justification in the students’ L1 seemed to have a positive effect on the production of the same component in their inter-language.

Negative Transfer

The most striking negative transfer occurred in terms of ‘candidate solution: demand’, which did not emerge in the English baseline data. The statistical analysis between the Turkish baseline data and the inter-language data showed that there was no statistically significant difference between ‘demand’ in the two data sets. (t = 0.51 < 2.042).

The second negative transfer was detected in ‘candidate solution: request’. There was a statistically significant difference between the English baseline data and the inter-language data (p = 0.004 < 0.05).

A notable result was the nonoccurrence of the speech act of ‘criticism’ in the inter-language, which was present in both the Turkish and the English baseline data. As in the case with the students speaking to the commiserating teacher, the students who spoke to the contradicting teacher avoided producing this speech act.

Conclusions

The analysis of the Turkish baseline data shows that when in the position of expressing disapproval to a teacher about a grade, both the TNSs and the ENSs produced a complaint speech act set, regardless of the attitude of the teacher. However, we found that 23.08% of the TNSs and 20% of the ENSs speaking to the commiserating teacher produced the speech act of criticism either on his or her own or together with a complaint. Similarly, 41.67% of the TNSs and 20% of the ENSs speaking to the contradicting teacher employed criticism. This finding was contrary to the findings of Murphy and Neu’s (1996) study, which revealed that English native speakers did not produce the speech act of criticism when complaining to a professor. Note that their study did not have students interacting with an interlocutor. Therefore, the finding of the present study could be attributed to the interaction with the teacher or to generational differences, as the students of today are considered significantly more demanding than ten years ago.

Another similarity found between the two native languages was that the frequency of the components in the complaint speech act set and the topics of these components were similar to each other. To illustrate, the students speaking to the contradicting teacher in both groups employed the components ‘complaint’, ‘request’, and ‘criticism’ with the same frequencies. They also employed the components ‘justification’ and ‘explanation of purpose’ with a very high frequency.

A major difference was that while all the ENSs speaking to the commiserating and contradicting teacher made use of ‘request’ as a solution to the problem, only 41.67% of the TNSs speaking to contradicting teacher and 76.92% of the TNSs speaking to the commiserating teacher opted for a request. The relatively higher frequency of the speech act of request in the commiserating teacher data set could be because of the attitude of the teacher. The fact that the Turkish native speaker, in general, could be more intimidated by a contradicting teacher might have had an effect on the use of the component request with lower frequency.

The finding that all ENSs produced request as the candidate solution was parallel to what Murphy and Neu (1996) found. DeCapua (cited in McKay & Hornberger, 1996), on the other hand, had found that German native speakers employed both demand and request as a candidate solution, which has also been found to be the case in the inter-language of Turkish EFL students in this study.

We found that the component ‘demand’ in the English baseline data was absent. This is a further difference from the Turkish data.

In short, our study revealed that Turkish native speakers produced ‘demand’ and ‘request’ for repair.

The analyses of the IL data revealed the presence of a complaint speech act set when in the position of expressing disapproval about a grade to a commiserating and/or a contradicting teacher.

We found the use of ‘complaint’ by the EFL learners speaking to the non-commiserating teacher with a comparatively lower frequency (80%) as apposed to the students speaking to the commiserating teacher (100%). This, again, could be related to the way the student might have felt with such a teacher. Seeing that the teacher was not welcoming, they might have opted out.

Most of the components and the topic of these components in the two data sets were comparable. For instance, ‘justification’ and ‘explanation of purpose’ were made use of with a high frequency by both the students speaking to the commiserating teacher and the students speaking to the contradicting teacher.

The students talking to the commiserating teacher and those talking to the contradicting teacher produced the component ‘demand’ as a solution to their problems, which was also present in the Turkish baseline, but absent in the English data sets.

We found the speech act of request being used with a low frequency (45%) in the contradicting teacher data set compared to that in the commiserating data set (90%). This might be related to the fact that the Turkish EFL learners might feel unsettled in presence of a contradicting teacher.

To date, the studies (e.g. Bergman & Kasper, 1992; Erçetin, 1995) have found that the kind of pragmatic transfer made by EFL learners was negative. However, in this study both positive and negative transfer were found in the commiserating and contradicting data sets.

The first positive transfer was made from Turkish to the inter-language using the components ‘explanation of purpose’, ‘complaint’, and ‘justification’.

As for negative transfer, the most significant one was that the students in both groups transferred the act of demand from Turkish to their inter-language.

There was also negative transfer about the use of ‘candidate solution: request’, which was used with much lower frequency by the TNSs and the Turkish EFL learners.

Our findings also revealed that besides pragmatic transfer, there was an instance of deviation from TL norms even when norms of L1 and TL were parallel. The learners avoided producing a criticism regardless of the attitude of the teacher. This could be related to perceived social distance between the EFL learners and a teacher who was a foreigner. Another possible explanation might be that learners follow their own IL rules. This finding of the study was also noted in the research conducted by Bonikowska (1988) who found that one reason for opting out could be the relationship of the speaker and the hearer.

Implications for Further Research

In order to verify and generalize these findings, this research can be replicated by carrying out studies in different social settings such as in a family, a dormitory, or an office.

One of the limitations of the study was that gender difference of the respondents was not taken into consideration. Future studies can replicate this study by studying the differences in the attitude of different sexes.

Another limitation of the study lies in the data-collection method, which was namely role-plays. If possible, future researchers can investigate the speech act of complaint produced in presence of a commiserating and contradicting teacher using naturally occurring data.

This study put the students into an asymmetrical status relationship with a teacher. Further research should investigate if there are differences in complaints in symmetrical status relationships.

This study did not take into account the linguistic aspects of the complaint speech act set, into which some research could be done. The linguistic elements of the set in the inter-language can be compared to those in L1 and L2. Such a study would help understand linguistic strengths and weaknesses that the students have in their inter-language. In this way, native speakers could be more tolerant to learners’ language misuse, and EFL teachers can adjust their teaching accordingly.

References

Barron, Anne (2005). Variational pragmatics in the foreign language classroom. System, 33(3), 519—536.

Bergman, M. L. & Kasper, G. (1993). Perception and performance in native and nonnative apology, In G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka (Eds.), Interlanguage Pragmatics, 82-107, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bonikowska, M. (1988). The choice of opting out. Applied Linguistics, 9 (2), 169-181.

Boxer, D. (1993). Complaints as positive strategies: what the learner needs to know. TESOL Quarterly, 27(2), 277-299.

Boxer, D. & Pickering, L. (1995). Problems in the presentation of speech acts in ELT materials: the case of complaint. ELT Journal, 49(1), 44-58.

Brown, P. & Levinson, S. C. (1978). Politeness: Some Universals in Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ercetin, N. G. (1995). Pragmatic Transfer in the Realization of Apologies: The case of Turkish EFL Learners. Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Boaziçi University, stanbul, Turkey.

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics, 269- 293, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Kasper, G. (1992). Pragmatic transfer. Second Language Research, 8:3, 203-231.

McKay, S.L. & Hornberger, N. H. (1996). Sociolinguistics and Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Márquez-Reiter and Placencia (2005). Spanish Pragmatics, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Murphy, B. &. Neu, J. (1996). My grade’s too low: the speech act set of complaining. In S. M. Gass & J. Neu (Eds.), Speech Acts Across Cultures: Challenges to Communication in Second Language, 191-216, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Olshtain, E. & Weinbach, L. (1993). Interlanguage features of the speech act of complaining. In G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka (Eds.), Interlanguage Pragmatics, 108-122, New York, Oxford : Oxford University Press.

Searle, J. R.(1990). Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zegarac, V. & Pennington, C. (2000). Pragmatic transfer in intercultural communication, In H. S. Oatey (Ed.), Interculturally Speaking, 165-190, London: Continuum.

(Endnotes)

1. The term ‘commiserating’ refers to the kinds of responses which offer agreement or reassurance to make the speaker feel better, and the term ‘contradicting’ describes the kind of interlocutor who does not accept or approve the complaint, or who provides some kind of defense for the thing being complained about (Boxer, 1993).

Role-Play Situations for Students

Role-Play Situation in English

Instructions

Read the situation below carefully. You have 3 minutes to think about what you would say to your teacher. When you are ready, go to her office and tell her what you want to say.

Your teacher has handed your composition homework back to you. However, you are surprised at your grade, you feel that the mark that you got is too low, and you do not deserve this low mark. You think the reason for this is that the things you wrote are different from your teacher’s personal beliefs. You believe that the content and the grammar of your paper are fine. You are particularly upset because you spent a lot of time writing this composition, and actually you had many sleepless nights perfecting the composition. You decide you must speak to her about this. So, after class, you go to the teacher during office hours and say:

Role-Play Situation in Turkish

Instructions

Asagidaki durumu dikkatlice okuyun. Ögretmeninize ne söyleyeceginize karar vermek için 3 dakikaniz var. Hazir oldugunuzda ögretmeninizin ofisine gidip söylemek istediklerinizi söyleyin.

Hocaniz kompozisyon ödevinizi size geri verdi. Ama siz notunuza çok s asiriyorsunuz, çünkü hiç de hak etmediginiz kadar düşük bir not aldiginiza inaniyorsunuz. Bunun sebebinin, hocanizin düsüncelerinden farkli s eyler yazmaniz oldugunu düsünüyorsunuz. Oysa, kompozisyonunuzun içerik ve dil bilgisinin iyi olduguna inaniyorsunuz. Bu ödev için çok fazla hazirlik yaptiginiz ve uykusuz geceler geçirdiginiz için de bu duruma gerçekten üzülüyorsunuz. Bu konuyla ilgili olarak hocanizla konusmaya karar veriyorsunuz ve ofis saatinde hocanizin yanina gidiyorsunuz. Hocaniza ne dersiniz?

Role-Play Situations for Teachers

Role-Play Situation in English for the Commiserating Teacher

Instructions

Read the situation below carefully. Speak to your student when he/she comes in your office.

You have handed back your students’ compositions. However, one of your students is surprised at his/her grade, and he/she feels that the mark he/she got is too low, and he/she does not deserve this low mark. He/she thinks that the reason for this is that the things he/she wrote are different from your personal beliefs. He/she believes that the content and the grammar of his/her paper are fine. He/she is particularly upset because he/she spent a lot of time writing this composition, and actually he/she spent many sleepless nights perfecting the composition. He/she decides to speak to you during your office hours.

In order to adopt the role of a commiserating teacher, you can do the following:

- You can express appreciation. Some things that you can say are:

— I can tell that you put a lot of work into this assignment.

— I’m glad that you came to talk to me about your paper.

— I realize that this grade is disappointing to you.

- You can ask for elaboration on his/her complaint, and a solution. Some things that you can say are:

— Why do you think so?

— Can you explain what you mean?

— What can I do for you?

- You can confirm the validity of the complaint. Some things that you can say are:

— I see your point.

— I think I should have read it more carefully

- You can provide signals such as eye contact, head nods, smiles, and body alignment, or make noises

— like “umhmm,” “uhhuh,” “yeah,” “you’re right” to encourage the student to continue talking.

— You can finish your student’s sentence.

Role-Play Situation in English for the Contradicting Teacher

Instructions

Read the situation below carefully. Speak to your student when he/she comes in your office.

You have handed back your students’ compositions. However, one of your students is surprised at his/her grade, and he/she feels that the mark he/she got is too low, and he/she does not deserve this low mark. He/she thinks that the reason for this is that the things he/she wrote are different from your personal beliefs. He/she believes that the content and the grammar of his/her paper are fine. He/she is particularly upset because he/she spent a lot of time writing this composition, and actually he/she spent many sleepless nights perfecting the composition. He/she decides to speak to you during your office hour.

In order to adopt the role of a contradicting teacher, you can do the following:

•- You can disapprove of the complaint. Some of the things you can say are:

— I don’t agree with you.

— I think you’ve missed my point.

— You think this is unfair!

— What kind of grade were you expecting for this!

- You can provide defense for the complaint. Some of the things you can say are:

— I always read my students’ papers very carefully.

— I gave the grade that this paper deserved.

— My opinion hasn’t got anything to do with it.

— There is nothing I can do. This is your responsibility.

—You are blowing this all out of proportion.

- You can avoid giving response to the student. Some of the things you can say are:

— Your grade won’t make difference in your overall grade.

— What did you think was the most important point of today’s lecture.

— I don’t have time to talk about it.

- You can provide insufficient or discouraging backchanneling signals. Some of the things you can say are:

— Really!

— Oh!

Role-Play Situation in Turkish for the Commiserating Teacher

Instructions

Asagidaki durumu dikkatlice okuyun. Ögrenciniz ofisinize geldiginde onunla konuşun. Ögrencilerinize komposizyonlarini geri verdiniz. Ancak ögrencilerden biri notuna çok s asiriyor. Notunun çok düsük oldugunu ve bunu hak etmedigini düsünüyor. Düsük notun sebebinin yazdigi s eylerin sizin kisisel görüslerinden farkli olduguna inaniyor. Ona göre içerik ve dil bilgisi ilgili bir problem bulunmamaktadir. Bu kompozisyonu yazmak için çok zaman harcadigi ve uykusuz geceler geçirdigi için de özellikle üzgün. Ofis saatinizde sizinle konusmaya karar veriyor.

Destekleyici ögretmene dair rolünüzü uygularken asagidakilerden faydalanabilirsiniz:

- Ögrencinizi ve söylediklerini anlayisla karsiladiginizi hissettirebilirsiniz.

‐ Düsüncelerini açikça söyledigin için tesekkür ederim.

‐ Ödev için o kadar çok mu çalistim?

‐ Sanirim bu not seni oldukça üzmüs.

— Bu not seni çok mu hayal kirikligina ugratti.

– Nasil hissettigini anliyorum.

Anladim.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.