DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v19n1.9292Published:

2017-02-10Issue:

Vol 19, No 1 (2017) January-JuneSection:

Research ArticlesDiscovering students’ preference for classroom activities and teachers’ frequency of activity use

Descubriendo las preferencias de los estudiantes por las actividades del aula

Keywords:

actividades, estilos de enseñanza, estilos de aprendizaje, preferencia, producción oral (es).Keywords:

Activities, speaking, preference, teaching styles, learning styles, oral production (en).Downloads

References

Arnold, J 2000, Seeing through listening comprehension exam anxiety. TESOL Quarterly 34 (4), 777–786.

Bada, E. and Okan, Z 2000, Students’ language learning preferences. TESL-EJ, 4(3), 1-15, http://tesl-ej.org/ej15/a1.html (consulted 30/07/11)

Barkhuizen, G P 1998, Discovering learners’ perceptions of ESL classroom teaching/learning activities in a South African context. TESOL Quarterly, 32 (1), 85-108.

Brown, H D 2000, Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. (4th edn.) White Plains, NY: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.

Buck, G 2001, Assessing Listening. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Castellanos, G. A 1981 Cd. Juarez: La vida fronteriza. Mexico: Nuestro Tiempo.

Dörnyei, Z 2002, Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dörnyei, Z and Csizer, K. 1998: Ten Commandments for motivating language learners.

Language Teaching Research, 2: 203-29.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Harlow: Longman.

Doughty, C 1991, Second language instruction does make a difference: Evidence from an empirical study of SL relativization. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 13, 431-496.

Dunkel, P 1986, Developing listening fluency in L2: Theoretical principles and pedagogical considerations. Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 99-106.

Eslami-Rasekh, Z and Valizadeh, K 2004, Classroom activities viewed from different perspectives: Learners’ voice vs. teachers’ voice. TESL-EJ, 8(3), 1-13.

Felder R M and Spurlin, J E 2005, Applications, reliability and validity of the Index of Learning Styles. International Journal of Engineering Education, 21 1 (2005), 103–112.

Felder, R M 1995, Learning and teaching styles in foreign and second language education. Foreign language annals, 28(1), 21-31

Fischer, N B and Fischer, L 1979, Styles in teaching and learning. Educational leadership 36(4),

Fotos, S 1996, ‘Integrating communicative language use and focus on form: A research agenda’. In Fujimura T, Kato Y, Ahmed, M and Leoung M. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th conference on second language research in Japan (37-41). Niigata: International University of Japan

Gatbonton, E 1999, Investigating experienced ESL teachers’ pedagogical knowledge. The Modern Language Journal, 83 (1), 35−50.

Graham, S 2006, Listening comprehension: the learners' perspective. System, 34 (2) 165-182. ISSN 0346-251X

Green, J M 1993, Student attitude toward communicative and non-communicative activities: Do enjoyment and effectiveness go together? The Modern Language Journal, 77 (i), 1-10.

Hanh, P T 2005, Learners’ and teachers’ preferences for classroom activities. Essex Graduate Student Papers in Language and Linguistics, 7(1), 159-179.

Harmer, J 2007, The Practice of English Language Teaching. Fourth Edition. England: Pearson Education Ltd.

Harshbarger, B, Ross, T, Tafoya, S and Via, J, 1986, Dealing with multiple learning styles in the ESL classroom. Symposium presented at the Annual Meeting of Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, San Francisco, CA.

Johnson, K E 1992a, Learning to teach: instructional actions and decisions of preservice ESL teachers. TESOL Quarterly, 26, 507-535.

Johnson, K E 1992b, The relationship between teachers’ beliefs and practices during literacy instruction for nonnative speakers of English.

Journal of Reading Behavior, 24 (1), 83−108.

Kang, Hoo-Dong, Son, Jeong-Bae, and Lee, Seong-Won 2006, Perceptions of and Preferences for English Language Teaching among Pre-service Teachers of EFL. English Language Teaching, 18(4), 25-49.

Kaplan, E J and Kies, D A 1995, Teaching styles and learning styles: Which came first? Journal of Instructional Psychology, 22(1), 29

Krashen, S 1981, Second Language Acquisition and Second Language Learning. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Kumaravadivelu, B 1991, Language-learning tasks: Teacher intention and learner interpretation. ELT Journal, 45 (2), 98-107.

Kumaravadivelu, B 2006, 'TESOL Methods: Changing Tracks, Challenging Trends', TESOL Quarterly, Vol 40: 59-79

Liu, N F and Littlewood, W 1997, Why do many students appear reluctant to participate in classroom learning discourse? System, 25/3, 371-384

McDonough S M 1995, Strategy and skill in learning a foreign language, London: Edward Arnold.

Nunan, D 1987, 'Communicative language teaching: making it work' in English Language Teaching Journal 41/2, 136-145

Nunan, D 1991, Communicative tasks and the language curriculum. TESOL Quarterly, 25 (2), 279-295.

Nunan, D 1992, ‘The teacher as decision-maker’. In J. Flowerdew, Brock, M and Hsia, S. (eds.), Perspectives on Second Language Teacher Education. 135-65, Hong Kong: City Polytechnic.

Nunan, D 1999, Second Language Teaching and Learning. Boston: Heinle and Heinle Publishers.

Oxford, R 2001, Integrated Skills in the ESL/EFL Classroom. ESL Magazine, V4 N1 18-20

Peacock, M 1998, Exploring the gap between teachers’ and learners’ beliefs about ‘useful’ activities for EFL. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8 (2), 233-250.

Quinn, T 1984, Functional approaches in language pedagogy. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 5, 60–80.

Rao, Z 2002, Chinese students’ perceptions of communicative and non-communicative activities in EFL classroom. System 30 (2002) 85-105

Reid, J. 1987. The learning style preferences of ESL students. TESOL Quarterly, 21/1, 87-111.

Renninger, K A 2009, Interest and Identity Development in Instruction: An Inductive Model. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 105-118.

Richards, J C 1998, Beyond Training. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J C and Rodgers, T S 2001, Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge University Press. 2nd edition

Richards, J, Platt, J and Weber, H 1986. Longman Dictionary of Applied Linguistics. London: Longman.

Schulz, R A 1996, Focus on form in the foreign language classroom: Students’ and teachers’ views on error correction and the role of grammar. Foreign Language Annals, 29(3), 343-364.

Shumin, K 1997, Factors to consider: Developing adult EFL students’ speaking abilities. English Teaching Forum 25(3). http://exchanges.state.gov/forum/vols/vol35/no3/p8.htm (consulted 29/11/11)

Spratt, M 1999, How good are we at knowing what learners like? System, 27(2),141-155.

Spratt, M 2001, The Value of Finding Out What Classroom Activities Students Like. RELC Journal, 32; 80 http://rel.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/32/2/80 (Consulted

/07/2011)

Tomlinson, B and Bao Dat. 2004: The contribution of Vietnamese learners of English to ELT methodology. Language Teaching Research, 8/2: 199-222.

Yorio, C 1986, Consumerism in Second Language Learning and Teaching. Canadian Modern Language Review, 42/3: 668-687.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/calj.v19n1.9292

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Discovering Students' Preference for Classroom Activities and Teachers' Frequency of Activity Use

Descubriendo las preferencias de los estudiantes por las actividades del aula

Nahum Samperio Sanchez

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Mexicali, México, nahum@uabc.edu.mx

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Samperio, N. (2017). . Colomb. Appl. Lingu8ist. J., 19(1), pp. 51-66.

Received: 30-Sept-2015 / Accepted: 21-Jan-2017

Abstract

This paper explores the preference students have for classroom activities and the frequency in which teachers include certain classroom activities in their practicum. The study followed a quantitative research methodology by collecting numerical data through a 62-item questionnaire developed from a pool of items gathered from different questionnaires. Analysis indicates a coefficient of reliability of α = .91; data were analyzed with SPSS software. Twenty English language teachers and 263 students of a language school were included in the study. Students' levels ranged from 1 to 6, the 6th the equivalent to B1 of the Common European Framework (CEF). Results indicated a mismatch between teachers' frequently used activities and students' preference of activities; however, there is a match in speaking activities.

Keywords: activities, learning styles, oral production, preference, speaking, teaching styles.

Resumen

Este documento explora la preferencia que los estudiantes tienen por las actividades del salón de clase y la frecuencia con que los maestros incluyen estas actividades en su práctica. El estudio siguió una metodología de investigación cuantitativa al recolectar datos con un cuestionario de 62 preguntas que se elaboró de una lista de actividades recolectadas de diferentes cuestionarios en la literatura. El análisis de confiabilidad indica un coeficiente de α = .907. Los datos fueron analizados con el programa SPSS. Veinte maestros de inglés y sus 263 estudiantes de una escuela de lenguas fueron incluidos en el estudio. Los niveles de los alumnos variaron del nivel 1 al 6, siendo el 6 el equivalente al B1 del marco común europeo de referencia para las lenguas (MCER). Los resultados indican una diferencia entre las actividades más usadas por los maestros y las actividades preferidas por los estudiantes en la mayoría de las actividades, sin embargo, hay una coincidencia en las actividades de producción oral.

Palabras clave: actividades, estilos de enseñanza, estilos de aprendizaje, preferencia, producción oral

Introduction

Many factors influence preference for learning activities in the language classroom; for example, learning and teaching styles, motivation, students' perception of usefulness or importance, classroom environment, personality, or language level. At times, teachers need to manage activities based on the possibilities available within their particular context. Nunan (1999) suggests that choices in teaching should take students into consideration; however, it does not appear to be an easy task. Choosing activities that should, could, or need to be used in the classroom goes beyond a teaching style. Dörnyei and Ushioda (2011) claim that classroom activities in EFL contexts have recently been reexamined and reconsidered by both teachers and researchers. They state that the interest in this reexamination seeks to generate, maintain, and improve the motivational level of the language students. According to Dörnyei and Ushioda (2011), learner preference for classroom activities has been associated with motivational factors, which influence learners' choices, engagement in action, effort, and persistence.

Activities might have positive and negative consequences. If teachers are able to make use of appropriate activities in the classroom, these activities could be the mediator to increase students' motivation and to decrease their anxiety. On the contrary, they might also bring consequences such as demotivation, increasing anxiety, boredom, absenteeism, or even dropping out of class. Nikolov (2009) showed that when activities were not motivating for students, it had a negative effect on learners' motivation. Renninger (2009) explains that it is possible for students to develop and deepen an interest in a topic over time, and that a person's environment (classroom, teachers, peers, texts, activities, etc.) contributes to this interest.

In general, activities play an important role in the process of learning in the classroom. However, it is necessary to define the term activity. Nunan (1991) defines the term "activities" as the elements of the task that specifies what the students will actually perform with the input; for instance, listening to recordings, writing a sentence, answering questions, etc. Coughlan and Duff (1994) define activity as the behavior that actually takes place when an individual performs a task. Similarly, Brown (2000) defines activity as "a reasonably unified set of student behaviors, limited in time, preceded by some direction from the teacher with a particular objective" (p. 159). According to Richards (n.d.) the term activity refers to any kind of purposeful classroom procedure that involves learners doing something that relates to the goals of the course. For example, singing a song, playing a game, taking part in a debate, and having a group discussion are all different kinds of teaching activities. Thus, for the purpose of this study, "activity" is any procedure intended to stimulate learning in order to rehearse a skill that might or not include a teaching strategy, material, and a goal, and which is developed in a certain amount of time.

The literature (e.g., Moore, 2001; Nunan, 1991) explains that it is important to take into consideration students' opinions for the selection of the activities and that a good selection of classroom activities engages students, facilitates learning, gives the teacher and students immediate feedback, and raises interests and motivation.

Teaching Styles and Teachers' Beliefs in Choosing Activities for the Classroom

The way teachers choose, adapt, and deliver classroom activities reflects their teaching styles and their methods or approaches to teach (e.g., audio-lingual, direct method, grammar translation, communicative approach, etc.). Sometimes teachers are not aware of the methods they use; consequently, choosing activities for the classroom much depends on their preference or the way they know how to transmit information, in other words, their teaching style.

Fan and Ye (2007) defined teaching style as the unique way teachers solve problems, conduct tasks, and make decisions in their teaching. Similary, Ghanizadeh and Jahedizadeh (2015) posit that "teaching style refers to all of teaching techniques, activities and approaches that a teacher employs in teaching a certain subject in the classroom" (p. 2). Thus, teachers perceive teaching in different ways and try to accommodate their style to learner's needs in order to facilitate learning.

Rao (2002) argues that matching styles effectively can only be achieved when teachers are aware of students' needs, capacities, potentials, and learning style preferences. The way a teacher approaches teaching can be both dangerous and beneficial for learning if their teaching differs from students' learning style. Felder and Spurlin (2005) claim that when there are mismatches, students might experience a feeling of boredom and may become inattentive, discouraged, demotivated about the class, or even with themselves, and, consequently, they may abandon the class. Oxford (2001) argues that in order to produce successful classes, the instructor's teaching style should be directed to students learning styles as much as possible. She also adds that the student should be motivated to learn the target language, and that the setting should provide resources and values that strongly support the teaching of the language.

It is important to consider that in order to match teaching and learning styles, teachers need to deal with conditions that could make it difficult such as having large classes. They prefer some classroom activities over others because of their perception of the usefulness, enjoyment, or motivational effect activities have on students. Thus, being able to match students' preferences with teachers' perceptions of these preferences has been difficult on the account of many variables. Often teachers are not able to include activities in class due to external factors such as institutional requirements.

Johnson (1992) conducted research with preservice teachers and discovered that they believed that motivation and instructional management are important and that they base their decisions on these aspects. Furthermore, Nunan (1992) found that teachers worry about the timing and the pacing of the lesson. Similarly, Gatbonton (1999) discovered that teachers are concerned about the way they deliver language to students. According to this, it is reasonable to say that every teacher focuses attention on different aspects; therefore, the choice for activities in the classroom differs according to their own beliefs. It is noteworthy to mention that some beliefs can become fixed and might shape teaching styles; consequently, teachers do not consider students' needs or preferences affecting language learning.

According to Kumaravadivelu (1991), teachers and students have their own opinions about what teaching and learning are. He claims that both see classroom activities in diverse ways and these ways do not always match. Concurrently, Nunan (1987) found mismatches between the opinion of teachers and students regarding the type of activities that were important in the process of learning. Even though teachers know what the students need or prefer, they do not often consider them when they have to choose or implement an activity. In many cases, activities that students do not like will be included in spite of their preference. However, Felder (1995) states that what a learner likes may not be the best for learning. Students' needs, wants, or deficiencies may vary the preferences they have for certain type of activities.

Influence of Activities in the Learning Process

Activities used in the classroom are important to learning in many ways. In compulsory classes, these factors might influence the decision of willingly attending class. The importance of knowing the activities that students like to have or do in the classroom will bring about students' enjoyment within the classroom environment, thus leading to attentive participation. Zhu (2012) found that interesting activities for students such as classroom games, for instance, guessing games, picture games, miming, debates, jigsaw activities, and role plays can improve students' communicative ability. In the same vein, Chanseawrassamee (2012) demonstrated that adult learners could have positive attitudes towards appealing activities. In the same way, Dörnyei and Csizer (1998) proposed a list of activities which stimulate students' interests as one important factor for motivating language learners. Including a wide variety of activities and tasks in the classroom that learners prefer can create a more interactive environment in which students will be more willing to participate. In this sense, both teachers and students can enjoy the learning experience.

Prior Studies on Preference for Activities

Research regarding activities has explored preferences of communicative or traditional activities as well as students' and teachers' perceptions of usefulness, preference, or even importance of activities in the learning process. For instance, Falout, Murphey, Elwood, and Hood (2008) conducted research with 440 Japanese university students exploring preference of communicative and traditional activities. Results indicated that learners preferred communicative activities instead of traditional grammar-centered activities. Sullivan (2016) discovered that learners not only liked but also wanted opportunities to communicate and create relationships with their classmates and their English teachers. Kang, Son, and Lee (2006) investigated the perceptions and preferences for English language teaching among EFL pre-service teachers. Concerning the use of certain teaching and learning activities in the classroom, respondents reflected on their teaching style by selecting studentto- student conversation, playing language games, and pronunciation drills as the most preferred ones. In contrast, they perceived traditional activities such as translation exercises and grammar exercises as the least preferred ones.

Peacock (1998) examined teachers' and learners' perceptions of the usefulness of different activities and suggested that perceived usefulness was a considerable predictor of course satisfaction and student motivation. He found that students preferred traditional learning activities to communicative activities. On the one hand, results indicated that students rated grammar exercises, pronunciation, and error correction more useful than teachers did. On the other hand, teachers believed that pair and group work plus communicative tasks were more useful. Peacock suggested that this mismatch might have a negative consequence not only on the learners' progress, but also on their satisfaction with the class and their confidence in their teachers. Similarly, Rao (2002) conducted research on the perception of communicative language teaching (CLT) and communicative activities for Chinese university students. These students reported that CLT activities were difficult to perform. Liu and Littlewood (1997) claim that the teaching of EFL in most Asian countries is dominated by a teachercentered, book-centered, grammar-translation method, and an emphasis on rote memory. In some social contexts, teachers' and students' roles are so strict that it is not considered that students should take part in deciding what processes or methods teachers should follow in the classroom. Harshbarger, Ross, Tafoya, and Via (1986) argued that Japanese and Korean students are quiet, shy, and reserved in language classrooms and this might be an aspect in students' perception for activities. Learners' preference and interests vary from culture to culture and context to context (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011) and preference and perception of activities varies as well.

Hanh (2005) investigated the preferences of students and teachers for 32 classroom activities and found that students preferred more traditional methods such as student-centered classroom activities. Hanh attributes these results to different aspects such as students' language proficiency, beliefs, and affective variables. In a similar vein, Garret and Shortall (2002) conducted research on the perception of EFL students at the beginning and intermediate levels in Brazil. They discovered that students tend to prefer more interactive activities as they move up through higher levels. These findings might be explained by the fact that when students begin to use all the knowledge they have learned in basic levels they start feeling more confident in what they are able to do with the language. However, beginner learners may feel the need to be directed by the teacher.

Barkhuizen (1998) investigated students' preferred activities in South African high schools and revealed that teachers' and students' perceptions differed greatly from each other. Students reported preferring traditional over communicative activities. Traditional approaches differ from communicative ones generally in the way information is administered to students: student-centered or teacher-centered. Traditional activities might seem preferable for students because the teacher has consistently been seen as the guide for learning. Contrary to Barkhuizen's study, Eslami-Rasekh and Valizadeh (2004) conducted a study in Iran and found that students have a higher preference for communicative activities, but teachers do not notice these preferences; therefore, teachers do not often include communicative activities in their practice. McDonough (1995) states that "activities valued by teachers are not the same valued by learners" (p. 131); he also claims that "students have their own learning agendas" (p. 121).

Although participation is a clear objective in EFL courses, activities might encourage or discourage students to do so. In the Vietnamese context, Tomlinson and Bao (2004) found that anxietyprovoking activities along with the classroom atmosphere hindered the performance of students in communication. Students reported that they liked having communicative group work activities, but they also reported that "anxiety," "linguistic limitations," and "classroom atmosphere" inhibited their active participation in class. Variation in the way students participate is the result of the perception of the activity in which they are required to participate.

Research on preference for activities has demonstrated that learners tend to prefer activities on both sides of the continuum. A few studies have reported finding a match between students' preferred activities and teachers' perceptions. Spratt (1999), for example, conducted a study with 997 students in Hong Kong using a questionnaire of 48 English language-learning activities. Spratt did not find any important differences between students' likes and teachers' awareness of those likes in communicative activities. The author found a 54% of match accuracy between students' preferences for activities and teachers' perception of these preferences. Students, unlike other studies, reported a preference for communicative activities.

Prior studies have reported mismatches in learners' and teachers' perceptions and preferences. Both teachers and learners see activities differently. It can be difficult to please students' preferences for activities; however, teachers' expertise and knowledge about their classes can help in choosing activities that can create an environment where most learners feel motivated to participate and learn.

Methodology

The study followed a quantitative research methodology by collecting numerical data through questionnaires. Data were analyzed using the SPSS and Excel software. The first purpose of this study aims at identifying the activities that learners prefer in the classroom. The second purpose of this study tries to identify the frequency of use with which teachers include the activities that learners prefer having in class. Finally, the third purpose seeks to identify if there is a match between preferences and frequency of use.

Research Questions

The research project was guided by the following three research questions:

1. What are the students' preferences for classroom activities?

2. What type of activities do teachers usually include in their daily teaching?

3. Does the teachers' frequency of activity use match students' preferences for activities?

Participants

Participants of this study were teachers and their students of the language school at public university in northern Mexico. The study was conducted with 12 female and 8 male EFL teachers who taught levels ranging from one to six. Teachers' age ranged from 21 to 55 years. Their teaching experience varied from 2 to 21 years. It also included 263 students, 182 female and 81 male. The average age of the students was 24 years old. Although the institutions' language school is meant to be for the university students, classes are open to the community in general. Therefore, two different types of students were found in the classroom and throughout the six levels and different class schedules. For the sample, 65 learners from the community and 168 university students participated. Language classes are compulsory for most university learners.

Instruments

Questionnaires were used to gather data about students' preference for activities they practice in class and the frequency in which teachers include these activities. In order to cover a wide range of activities for the questionnaire, a pool item (Dörnyei, 2002) of activities or events observed and measured in prior studies was gathered (Bada & Okan, 2000; Barkhuizen, 1998; Green, 1993; Hanh, 2005; Kang, Son, & Lee, 2006; Peacock, 1998; Spratt, 1999). Due to the fact that a textbook (American English File series) is used in classes in this institution, and considering that some of the teachers make use of the activities from such book, the most frequent activities from the textbook were also included. Thus, a list containing 180 items from previous research studies was gathered and scrutinized in order to create the questionnaires in order to avoid ambiguous sentences, repetition of items, negative constructions, double-barreled questions, and answers that are likely to be answered in the same way by everybody (Dörnyei, 2002). The questionnaire was structured and reduced to 62 items based on Dörnyei's (2000) observations. The items chosen for the questionnaire were the ones that were more commonly mentioned in prior studies along with the activities used in the textbook which teachers used in their daily practice. The questionnaire was piloted and Cronbach's alpha coefficient of reliability of the piloted questionnaire (α = .89) suggested that it was a reliable instrument.

The internal consistency of the questionnaires was tested by means of a reliability analysis to determine how closely related the items in the questionnaire were as a group. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient of reliability that measures the internal consistency was obtained through SPSS 20.0. According to Kerlinger and Lee (2000), reliability coefficients of .70 or higher demonstrate that a scale possesses acceptable reliability. Cronbach's alpha coefficient of reliability for the students' questionnaire was α = .91 suggesting that the items have relatively high internal consistency. Standard deviation ranged from 0.99 to 1.70 and no significant differences could have been obtained if any of the items had been deleted. Therefore, all of the items were included. Cronbach's alpha coefficient of reliability for teachers' questionnaires was α = .94 suggesting that the items have relatively high internal consistency.

Items were grouped by skills on the teachers' questionnaire: 1-7 grammar; 8-20 listening; 21- 38 speaking; 39-46 reading; 47-52 writing; 53-56 vocabulary; 57-62 other activities. This approach was used in order for teachers to focus attention on the skill under study and could provide a clear answer of the activity asked. The questionnaire administered to teachers explored the frequency with which teachers used these activities in the classroom by means of the statement "I have my students…" followed by the activity. The students' questionnaire included the same activities as the teachers' questionnaire. It included the statement "In the English classroom, I like…" A Likert scale measured their answers ranging from always (6) to never done (1). The student questionnaire was translated into Spanish (see Appendix 1) in order for students to fully understand the description of each of the items.

Although Sullivan (2016) indicates that "the term 'preference' refers to the stable likes and dislikes that individuals possess" (p. 35), it is important to point out that the words "like and prefer" in this study were used in their simplest form following Spratt's (1999) differentiation, and do not make distinctions in terms of usefulness, importance, or achievement.

Results and Discussion

The primary aims of this research were to identify students' preferences for activities and to explore the extent to which teachers included such activities in their daily practice. It was also intended to observe the concordance between what the teachers do and what students like as well as to explore if there was a match in the frequency of activity use by teachers and students' preference for activities.

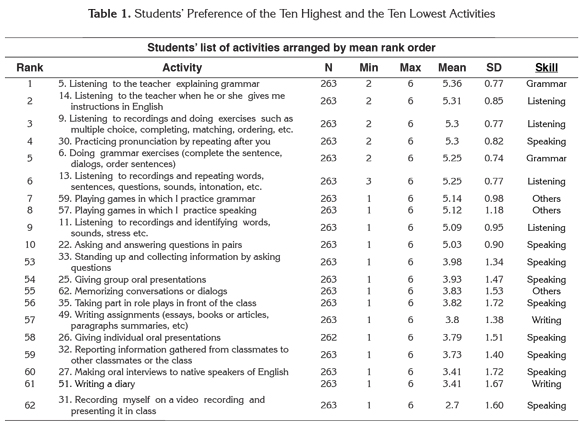

Most Preferred Activities by Students

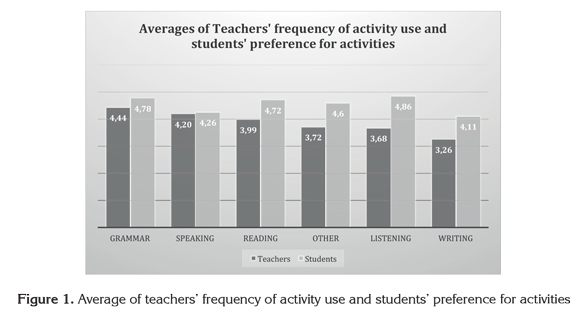

Results indicated that students favored activities in which they practiced traditional receptive skills and traditional productive skills. The results concur with Barkhuizen's (1998) findings which reported that learners favored traditional over communicative activities. Although teachers try to follow a studentcentered pedagogy, students tend to prefer having 57 a teacher-centered one. Learners showed the highest preference for listening activities (M = 4.86, SD = .63) followed by grammar activities (M = 4.78, SD = .59). That is, they preferred activities where teachers provide information and they act as the receiver of that information. In the same way, but to a lesser extent, students reported a preference for reading activities (M = 4.72, SD = .69); other activities (M = 4.60, SD = .73); speaking activities (M = 4.26, SD = .67); and writing activities (M = 4.11, SD = .88).

Contrary to findings observed in literature, findings in this study indicate that learners like activities that make them practice listening skills. Students ranked 5 out of the 15 listening activities among the 10 activities with the highest rank (see Table 1). Within the 10 most preferred activities, learners reported preferences for listening activities such as listening to the teacher when he or she gives them instructions in English (M = 5.31, SD = .85), listening to recording and doing exercises (M = 3.3, SD = .77), listening to recording and repeating (M = 5.25, SD = .77), listening to recording and identifying words (M = 5.9, SD = .87). Table 1 shows the 10 most and the 10 least preferred activities by learners.

Although listening activities help students rehearse for real life and this practice helps them gain confidence, listening is often a challenging and difficult skill to acquire. This might be attributed to the fact that learners have to deal with a range of accents and speeds, and content which may be difficult to follow. Buck (2001) argues that in the listening process students must use not only linguistic, but also non-linguistic sources of knowledge in order to interpret incoming data. Similarly, Graham (2006) states that there is evidence that students do not feel comfortable with their listening skills. Furthermore, Arnold (2000) states that listening induces anxiety in students because of the pressure it places on them to process input rapidly.

A probable reason why students might prefer listening activities is that they seem to assess their listening skill based on their development in real life situations, mainly through Radio and TV, in which they are able or unable to comprehend natural spoken English delivered at normal speed. Graham (2006) states that "learners are likely…to have certain beliefs about listening, which may influence the way in which they approach it" (p. 166). Their belief about listening may influence their preference for such activities. However, students' perceptions of their listening skills might not correspond to the real needs for the language. Dunkel (1986) suggests that developing language proficiency in listening comprehension is the key to achieving proficiency in speaking. Being able to understand gives students enough input to produce output in speaking situations. Therefore, gaining proficiency in listening, gives them confidence in speaking.

Grammar activities were also found within students' preferences (see Table 1). Grammar activities such as listening to the teacher explaining grammar (M = 5.36, SD = .77), doing grammar exercises (M = 5.27, SD = .74) and playing games where I practice grammar (M = 5.14, SD = .98) were also scored among the 10 most preferred activities by students.

Similar to this finding, Peacock (1998) found that students perceive grammar exercises as being much more useful than teachers do. Students might see grammar practice as something that helps them make a better sense of how language works. Additionally, it helps them notice how much they have learned since they are able to perceive their progress in learning even though they do not apply such knowledge in a practical use.

Commonly, learners believe that in order to be able to be proficient in English, it is necessary to learn the correct use of grammar in spite of what the communicative approaches suggest. Schulz's (1996) study revealed that students believed that in order to master a language, it was necessary to study grammar. Similarly, Richards and Rodgers (2001) suggest that explicit grammar teaching is beneficial to students regardless of the existing movement toward a communicative approach to English language teaching. Thus, teachers who aim at communication might see grammar as not necessary whereas students would find it useful in their learning.

Results also indicated that practicing pronunciation by repeating after the teacher (M = 5.3, SD = 82) and asking and answering questions in pairs (M = 5.03, SD = 90) were the speaking activities reported among students' 10 favorite activities (see Table 1). These activities do not reflect the use of the communicative language teaching because they might be considered controlled activities (Harmer, 2007). Communicative language teaching (CLT) encourages teachers to include activities that develop communicative skills such as speaking. Results suggest that students see speaking activities as a part of the process of learning and not as something that they entirely enjoy doing in the classroom. They most likely see speaking activities as necessary and even as enjoyable, but a few of them tend to favor speaking activities with a high preference over other skills as the main reason for studying the language.

In general, the type of activities learners prefer does not reflect the activities that they need in order to improve their learning. Students probably prefer activities they enjoy over the activities that help them improve their learning. Although they are not aware about how activities can help them improve their learning, teachers could make them conscious of those benefits by simply explaining how certain activities can help them.

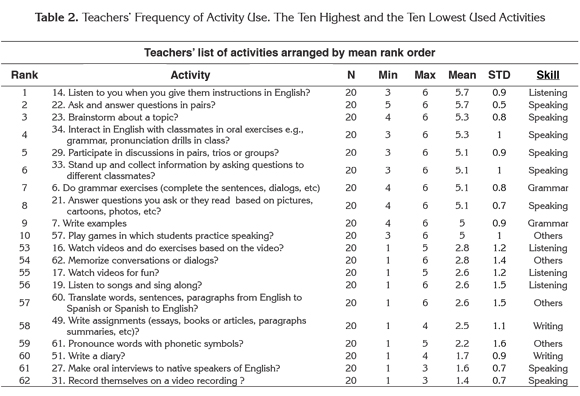

Activities More Frequently Used in Teachers' Daily Practice

Another aim of this study was to observe the frequency with which teachers include certain activities in their daily practice (see Table 2). Unlike students' preferences for listening activities, results indicated that teachers mostly included activities that promote oral communication and the practice of grammar. Teachers reported using grammar (M = 4.44, SD = .76) and speaking activities (M = 4.20, SD = .43) more often. To a lesser degree, learners reported a preference for reading (M = 3.99, SD = .80) and other activities (M = 3.72, SD = .66). Results indicated that teachers less frequently used listening (M=3.68, SD=.93) and writing activities (M = 3.25, SD = .73), in this sense, the frequency with which teachers used listening activities and students' preference for these activities do not match.

Frequency was measured concerning the amount of times teachers included activities in the classroom; however, the length of the activity itself was not explored in the questionnaire. It is necessary to mention that the length of the activity might be a factor that would have influenced teachers' answers. It is not the same including an activity very frequently that takes thirty minutes than an activity that takes ten minutes. For instance, giving oral presentations would not be used frequently due to the time it would take to be prepared and performed.

When analyzing teachers' data (see Table 2), it was found that activity 14, "have students listen to me when I give them instructions in English" (M = 5.7) was the most frequent activity used in the language classroom, matching students' second most preferred activity. The main source of language input comes from the teacher who may use English as a tool for instructions. Using English in the classroom gives students the opportunity to be in contact with real and natural English and gives them the feeling that English is useful for communication. Additionally, it helps in creating an English atmosphere in the classroom and aids students to feel motivated and ready to learn.

Contrary to students' preferences for activities, teachers scored speaking activities not only in the highest positions, but also in the lowest ones (see Table 2). Among the ten activities most frequently used, there are six used for speaking. Table 2 shows activities arranged by rank mean. Teachers reported frequently having students ask and answer questions in pairs (M = 5.7, SD = .49), brainstorm about a topic (M = 5.3, SD = .79), interact in English with classmates in oral exercises (M = 5.3, SD = 1.02), participate in discussions (M = 5.1, SD = .85), and mingle and collect information (M = 5.1, SD = 1.02). These activities promote the communicative approaches as described by Quinn (1984).

A reason for this can be explained by describing the geographical context of Tijuana. Tijuana is a Mexican city that borders the United States. Many learners have the possibility to cross the border. When they cross the border, they face an immediate need to communicate in English. Since Tijuana requires communicative skills due to its geographical location, for many adult students, speaking English is the main goal. Teachers seem to approach this immediate need by including activities to promote speaking primarily. Perhaps they try to give students opportunities to express themselves in English in order to prepare them for the real use of the language. Shumin (1997) states that for learning to speak a foreign language, students' need more than knowing simply grammar and vocabulary; students should acquire skills by interacting and using the language that they are learning.

The way teachers perceive usefulness, importance, or preference results in activities chosen to be used in the classroom. It can only be speculated that teachers seem to perceive the importance and usefulness of gaining fluency in speaking, and the need students have for a more interactive way of using the language as well as the practice it requires to gain communicative competence.

In the literature reviewed (Bada & Okan, 2000; Barkhuizen, 1998; Eslami-Rasekh & Valizadeh, 2004; Hanh, 2005; Peacock, 1998; Spratt, 1999) students do not perceive speaking activities as essential or vital in learning the language; they perceive speaking as an element of balance in learning the language. This can be inferred from the low frequency of speaking activities that students reported as the ones they like or enjoy having in class.

The preference teachers have for speaking activities over other skills might come from the belief and knowledge that speaking skills are necessary to improve oneself in a border city (such as in the case of this study) where there is a need for oral communication. The speaking skill is as crucial as in any other language although no skill can be isolated. All of them have to be developed together in order to achieve successful language teaching and learning. According to Harmer (2007), productive skills (writing and speaking) and receptive skills (reading and listening) cannot be isolated because one skill can support another in different ways. In other words, input and output need to be balanced in the classroom. Brown (2000) argues that a "wealth of integrating-skills promote greater students' motivation in order to convert to better retention of principles for effective speaking, listening, reading, and writing" (p. 218). However, writing activities were neither preferred for the learners nor included by teachers in their daily practice.

Results also indicated that speaking activities such as making oral interviews to native speakers of English (M = 1.4) and recording themselves on a video recording (M = 1.6) were scored as "never done in class before" or "almost never." Teachers ranked these activities in the lowest positions (see Table 2). Perhaps, they consider these activities as anxiety provoking for students.

Even though results did not favor grammar activities in its entirety, grammar plays an important role in teaching amongst the most frequently used activities. Teachers reported to include activities such as doing grammar exercises (M = 5.1, SD = .76), writing examples of a new structure seen (M = 5.0, SD = .92), and (in the 11th position in the rank) listening to the teacher explaining grammar (M = 5.0, SD = .83). While teachers seem to notice the importance of improving students' communicative competence, they also aim at accuracy for grammatical competence.

Including grammar practice might have to do with teachers' beliefs. Teachers choose activities according to their own experiences as students and teachers, and the actual view and philosophy of their educational institution. The institution determines the textbook and if teachers should emphasize the teaching of grammar. Teachers do not completely decide on what needs to be taught in everyday classes, but they see grammar as one of the skills students must learn. Although communicative approaches do not give grammar much importance, some type of emphasis on grammatical forms is necessary. Findings suggest that teachers believe that it is better to practice language in simulated real life situations than to study grammatical forms explicitly. However, students might believe that in order to master a language, it is necessary to study grammar. Doughty (1991) and Fotos (1996) explain that there is evidence to suggest that grammatical awareness and error correction for certain grammatical structures may actually enhance second language acquisition.

Overall, teachers in this study include mainly speaking and grammar activities. On the one hand, grammar activities help students gain accuracy and give students confidence to develop full ideas and thoughts. On the other hand, speaking activities provide learners with the opportunities to rehearse what they know and to get feedback on their performance.

Teachers' Frequency of Activity Use and Students' Preference for Activities

Mean scores for all questionnaire items were computed by skills. Results indicated that students scored higher in all of the areas: grammar, listening, speaking, reading, writing, vocabulary, and others (see Figure 1). These results suggest that students' answers are based on opinions and perception whereas teachers perhaps based their answers on facts. Students may favor activities based on a wider range of reasons, for instance, activities in which they feel comfortable, pleased, entertained, interested, or simply because they liked it. Nevertheless, teachers reported their real frequency in which they include activities in the classroom.

Average scores of both teachers and students seemed to match in the speaking activities categories (see Figure 1); nevertheless, most of the other categories showed differences in averages.

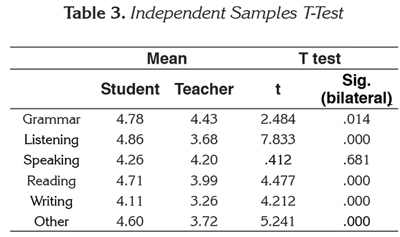

In order to determine whether differences identified in students' and teachers' scores were significant, t-tests for independent samples were performed. Levene's test indicated there was no significant difference in variances, therefore, equal variances were assumed. Results showed no significant differences in the frequency of activity use and students' preference of speaking activities that suggests a match between sets of data. However, listening, reading, writing, and other activities show a significant difference indicating a mismatch between preferred activities and their frequency of use in the classroom. Table 3 shows means scores and t-test results of students' and teachers' averages.

The reasons why activities are frequently used in the classroom are not exactly examined in this study. As seen previously, there are some factors that can be accounted for the activities learners prefer in the classroom: teaching and learning styles, students' needs for studying the language, students' lack of language, the classroom environment, students' motivation, time allocated for the class, and even their own literacy in their native language. However, matching the frequency of use with students' preference is difficult. Somehow, teachers manage to choose activities based on the previously mentioned factors that are constantly changing in everyday practice. It is possible to hypothesize that they usually do whatever they have to do, whatever they can do, or whatever they feel they should do as long as learning is achieved.

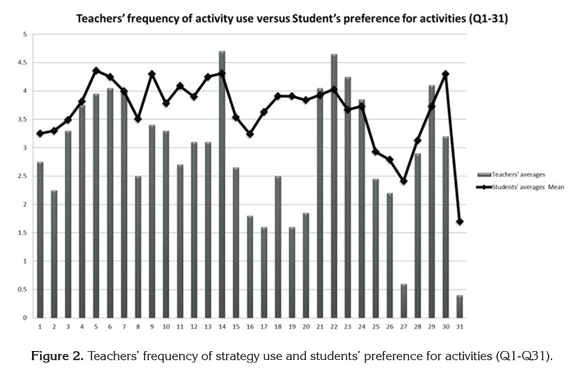

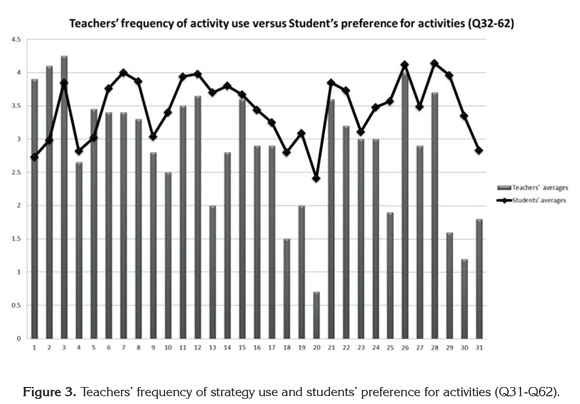

When items were analyzed individually and means scores of teachers' and students' answers were compared, it was observed that, in general terms, 51 activities showed a mismatch; however, 23 activities showed an important mismatch between students' preference and teachers' frequency of use (see Figures 2 & 3). Activities such as grammar (item 2); listening (items 8, 11, 13, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20); speaking (items 27, 30 ,31, 32, 33); reading Figure 2. Teachers' frequency of strategy use and students' preference for activities (Q1-Q31). 63 (items 44, 45); writing (items 49, 50, 51); vocabulary (item 56), and others (items 60, 61, 62) showed a higher difference between students' and teachers' averages (see Figures 2 & 3). Thus, 51 activities that represent 82% of the total of activities included in the questionnaires did not match students' preferences and teachers' frequency of use.

Since every learner is unique and perceives activities differently, many factors can be attributed to their preference for activities; for example, students' enjoyment when performing the activity, the degree of anxiety that the activity provokes, the perception of usefulness it has in their learning, etc. Similarly, many factors also influence teachers' inclusion of these activities in the classroom. For instance, the learning goal the teacher intends to reach, teaching styles, teacher's beliefs, etc. Teachers mainly include activities in the classroom with a goal in mind and the development of the activity is based on the goal intended.

Ideally, teachers should include activities that learners enjoy doing and which benefits their learning but this does not always happen. Thus, a careful selection of activities that can involve learning and enjoyment is not very easy; however, there can be a negotiation between actors in the inclusion of activities in the classroom. Both teachers and students can come to agreements on what should be included in the classroom. Teachers can always opt for a negotiation with students by openly asking students the type of activities they prefer having in class. The teachers' role is to choose the activities that can please both parties, then their expectations for activities can be fulfilled. This would increase motivation and help in developing an enjoyable environment. Results have demonstrated that teachers try to include activities that help learners use the language with accuracy and in a communicative way.

Conclusion

It appeared that students' preferences are not met by language instruction in this study. Results indicate that teachers frequently do not include activities that students would prefer having in class. It also demonstrated that learners prefer activities in which the teacher provides and facilitates knowledge. Observing the preference for traditional or communicative activities was not an aim of this study; however, it became quite clear that students still feel comfortable with traditional student-centered methods. Despite the geographical context of Tijuana where language can be an immediate need, students do not see speaking activities as something they like having more frequently in class to improve their speaking skill. However, teachers seem to realize that learners need more communicative practice with the language and they include more activities that promote communication and interaction between students in their daily practice.

It is necessary to understand that what students like is not always what they need (Felder, 1995). Teachers seem to choose activities based on what they perceive students lack and need. Therefore, the task of the teachers is to modify those activities students do not prefer into something they would enjoy having in their learning experience, especially if such activities are considered beneficial or useful for students.

Although the selecting criteria for activities were not analyzed in this study, it can be implied from results that teachers choose activities based on two main aspects: 1) their teaching styles, and 2) teachers' beliefs about teaching, learning, and the textbook. It is often not explicit or sufficiently clear why teachers choose activities, but most English teachers have certain preconceived ideas or beliefs about how best approach English teaching. It is equally important to note that preference is subjective and it constantly varies during a lesson or a course; factors that enhance preference are always fluctuating and depend on each individual.

References

Arnold, J. (2000). Seeing through listening comprehension exam anxiety. TESOL Quarterly, 34(4), 777-786.

Bada, E., & Okan, Z. (2000). Students' language learning preferences. TESL-EJ, 4(3), 1-15.

Barkhuizen, G. P. (1998). Discovering learners' perceptions of ESL classroom teaching/learning activities in a South African context. TESOL Quarterly, 32(1), 85- 108.

Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching (4th ed.) White Plains, NY: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.

Buck, G. (2001). Assessing listening. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Chanseawrassamee, S. (2012). Teaching adult learners English through a variety of activities: Perception on games and rewards. US-China Foreign Language, 10(7), 1355-1374.

Coughlan, P., & Duff, P. (1994). Same task, different activities: Analysis of SLA from an activity theory perspective. In J. Lantolf & G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskian approaches to second language research (pp. 173- 194). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Dörnyei, Z. (2002). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizer, K. (1998). Ten Commandments for motivating language learners. Language Teaching Research, 2, 203-29.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Harlow: Longman.

Doughty, C. (1991). Second language instruction does make a difference: Evidence from an empirical study of SL relativization. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 13, 431-496.

Dunkel, P. (1986). Developing listening fluency in L2: Theoretical principles and pedagogical considerations. Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 99-106.

Eslami-Rasekh, Z., & Valizadeh, K. (2004). Classroom activities viewed from different perspectives: Learners' voice vs. teachers' voice. TESL-EJ, 8(3), 1-13.

Falout, J., Murphey, T., Elwood, J., & Hood, M. (2008). Learner voices: Reflections on secondary education. In K. Bradford Watts, T. Muller, & M. Swanson (Eds.), JALT 2007 Conference Proceedings. Tokyo: The Japan Association for Language Teaching.

Fan, W., & Ye, S., (2007). Teaching styles among Shanghai teachers in primary and secondary schools. Educational Psychology, 27, 255-272. doi:10.1080/01443410601066750

Felder, R. M., & Spurlin, J. E. (2005). Applications, reliability and validity of the Index of Learning Styles. International Journal of Engineering Education, 21(1), 103-112.

Felder, R. M. (1995). Learning and teaching styles in foreign and second language education. Foreign Language Annals, 28(1), 21-31.

Fotos, S. (1996). Integrating communicative language use and focus on form: A research agenda. In T. Fujimura, Y. Kato, M. Ahmed, & M. Leoung (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th conference on second language research in Japan (pp. 37-41). Niigata: International University of Japan.

Garrett, P., & Shortall, T. (2002). Learners' evaluations of teacher-fronted and student-centred classroom activities. Language Teaching Research, 6(1), 25-57.

Gatbonton, E. (1999). Investigating experienced ESL teachers' pedagogical knowledge. The Modern Language Journal, 83(1), 35-50.

Ghanizadeh, A., & Jahedizadeh, S. (2015). EFL teachers' teaching style, creativity, and burnout: A path analysis approach. Cogent Education, 3, 1-17.

Graham, S. (2006). Listening comprehension: The learners' perspective. System, 34(2) 165-182.

Green, J. M. (1993). Student attitude toward communicative and non-communicative activities: Do enjoyment and effectiveness go together? The Modern Language Journal, 77(i), 1-10.

Hanh, P. T. (2005). Learners' and teachers' preferences for classroom activities. Essex Graduate Student Papers in Language and Linguistics, 7(1), 159-179.

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching (4th ed.). England: Pearson.

Harshbarger, B., Ross, T., Tafoya, S., & Via, J. (1986). Dealing with multiple learning styles in the ESL classroom. Symposium presented at the Annual Meeting of Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, San Francisco, CA.

Johnson, K. E. (1992). The relationship between teachers' beliefs and practices during literacy instruction for nonnative speakers of English. Journal of Reading Behavior, 24(1), 83-108.

Kang, H.-D., Son, J.-B., & Lee, S.-W. (2006). Perceptions of and preferences for English language teaching among pre-service teachers of EFL. English Language Teaching, 18(4), 25-49.

Kerlinger, F. N., & Lee, H. B., (2000). Foundations of behavioral research (4th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College Publishers.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (1991). Language-learning tasks: Teacher intention and learner interpretation. ELT Journal, 45(2), 98-107.

Liu, N. F., & Littlewood, W. (1997). Why do many students appear reluctant to participate in classroom learning discourse? System, 25(3), 371-384.

McDonough, S. M. (1995). Strategy and skill in learning a foreign language. London: Edward Arnold.

Moore, D. (2011). Effective instructional strategies: From theory to practice. California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Nikolov, M. (Ed.). ( 2009). The age factor and early language learning. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Nunan, D. (1987). Communicative language teaching: Making it work. English Language Teaching Journal, 41(2), 136-145.

Nunan, D. (1991). Communicative tasks and the language curriculum. TESOL Quarterly, 25(2), 279-295.

Nunan, D. (1992). The teacher as decision-maker. In J. Flowerdew, M. Brock, & S. Hsia (Eds.), Perspectives on second language teacher education (pp. 135- 65), Hong Kong: City Polytechnic.

Nunan, D. (1999). Second language teaching and learning. Boston, MA: Heinle and Heinle.

Oxford, R. (2001). Integrated skills in the ESL/EFL classroom. ESL Magazine, 4(1) 18-20.

Peacock, M. (1998). Exploring the gap between teachers' and learners' beliefs about 'useful' activities for EFL. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(2), 233-250.

Quinn, T. (1984). Functional approaches in language pedagogy. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 5, 60-80.

Rao, Z. (2002). Chinese students' perceptions of communicative and non-communicative activities in EFL classroom. System, 30, 85-105.

Renninger, K. A. (2009). Interest and identity development in instruction: An inductive model. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 105-118.

Richards, J. C. (n.d.). Difference between task, exercise, activity. Retrieved from http://www.professorjackrichards.com/difference-task-exerciseactivity/

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schulz, R. A. (1996). Focus on form in the foreign language classroom: Students' and teachers' views on error correction and the role of grammar. Foreign Language Annals, 29(3), 343-364.

Shumin, K. (1997). Factors to consider: Developing adult EFL students' speaking abilities. English Teaching Forum, 35(3). Retrieved from http://exchanges.state.gov/forum/vols/vol35/no3/p8.html

Spratt, M. (1999). How good are we at knowing what learners like? System, 27(2), 141-155.

Sullivan, C. (2016). Student preferences and expectations in an English classroom. Hermes-Ir, 52, 35-47.

Tomlinson, B., & Bao, D. (2004) The contribution of Vietnamese learners of English to ELT methodology. Language Teaching Research, 8(2), 199-222.

Zhu, D. (2012). Using games to improve students' communicative ability. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 3(4), 801-805.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.